Introduction

In his Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536), Calvin argued that humans were granted universally accessible sources of information about God:

As a heathen tells us, there is no nation so barbarous, no race so brutish, as not to be imbued with the conviction that there is a God. Even those who, in other respects, seem to differ least from the lower animals, constantly retain some sense of religion; so thoroughly has this common conviction possessed the mind, so firmly is it stamped on the breasts of all men. Since, then, there never has been, from the very first, any quarter of the globe, any city, any household even, without religion, this amounts to a tacit confession, that a sense of Deity is inscribed on every heart (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 3).

Expanding on Calvin’s ideas, Plantinga and other neo-Calvinist epistemologists argue that if God exists, humans were granted such globally accessible sources of information, which make theistic belief rationally compelling on a global scale (Plantinga Reference Plantinga1981, Reference Plantinga2000; Plantinga and Bergmann Reference Plantinga, Bergmann and Craig2015; see also Talbot Reference Talbot1989; Lehe Reference Lehe2004; Sudduth Reference Sudduth2009; Craig Reference Craig2015; Hendricks Reference Hendricks2021). For both Calvin and Plantinga, such sources include sensus divinitatis – an innate sensory faculty that immediately perceives God’s existence (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 3; Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 174) – and the Holy Spirit’s testimony (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 7; Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 242, 309). But if everyone possesses such clear sources of information, how could any intellectually mature adults possibly be atheists? Both thinkers bluntly and emphatically explain atheism in terms of an irrational and self-deceptive resistance to these mechanisms, which is caused by sin (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 4; Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 205, 303) – Plantinga describes this self-deceptive state as one of ‘imperceptiveness, dullness, stupidity’ and ‘hostility’ towards God (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2015, 49–50). Recently, similar strategies have been discussed both favourably and critically in the contexts of other Western and non-Western religious stances, such as Islam and Hinduism (e.g., Aijaz Reference Aijaz2024; Gupta Reference Gupta2022).

Neo-Calvinist epistemology has received mixed reactions. Most critics question, on empirical grounds, the existence of the purported sources of knowledge about God in the actual world (e.g., Launonen Reference Launonen2021, Reference Launonen2025; Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006; Philipse Reference Philipse2014; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993). However, what we call modal Calvinism, namely the alleged implications of neo-Calvinist epistemology as long as it is possibly true, has largely been unexplored. Furthermore, as we shall see very soon, recent studies observe that many atheists commit to a key component of modal Calvinism (Curtis Reference Curtis2021; Hendricks Reference Hendricks2021). We aim to explore this underexplored area.

Modal Calvinism has two key components. The first is its basic conditional proposition, ‘If God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and there are no rationally based non-believers’. This is the obvious upshot of the aforementioned neo-Calvinist epistemology (including its sinful self-deception hypothesis, which is necessary for explaining atheistic anomalies).Footnote 1 Under Plantinga and his followers’ view, the second, argumentative component follows from this conditional: even as a conditional possibility, it undermines what he terms de jure objections to theism (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 498).

‘De jure objections’ is an umbrella term that covers a wide variety of arguments for the conclusion that theistic belief is rationally impermissible, whether or not God exists – namely, both if God exists and if God does not exist.Footnote 2 Plantinga references cases that appeal to Marx’s view of religion as the opium of the people, Freud’s view of religion as wish-fulfilling illusions, Nietzsche’s interpretation of Christianity as a product of slave morality, general claims of theism’s lack of good evidence, and the like (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, Reference Plantinga2015; Plantinga and Bergmann Reference Plantinga, Bergmann and Craig2015). Additionally, more recent cases include evolutionary debunking arguments (e.g., Atran Reference Atran2002; Dennett Reference Dennett2006; Wilkins and Griffiths Reference Wilkins, Griffiths, Dawes and Maclaurin2013) and Oppy’s (Reference Oppy2013) famous argument that naturalism always provides equally compelling but ontologically more parsimonious explanations for all data.Footnote 3 Readers familiar with the history of philosophy may even recall Hume’s (1748/Reference Hume2007) probabilistic argument against miracles and Kant’s (1766/Reference Kant and F1900, 1781/Reference Kant, P and A1998) cognitive limitation argument against non-prudential reasons for believing in God, even though these arguments target only specific subsets of grounds for theistic belief. De jure objections are often considered important to many atheists because they often aim to provide a more general rational basis for atheistic or naturalistic frameworks (e.g., Hume 1748/Reference Hume2007; Dennett Reference Dennett2006; Oppy Reference Oppy2013; Wilkins and Griffiths Reference Wilkins, Griffiths, Dawes and Maclaurin2013; cf. Kant 1766/Reference Kant and F1900, 1781/Reference Kant, P and A1998), besides specific metaphysical debates about arguments for and against God’s existence (e.g., the cosmological argument and the problem of evil). As Plantinga notes, perhaps these objections’ spirit is well captured by Russell’s famous quip about his hypothetical afterlife confrontation with God: ‘Not enough evidence, God! Not enough evidence!’ (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2015, 30).Footnote 4

Logically, if the Calvinist conditional is right that ‘if God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling’, it cannot also be true that ‘even if God exists, theistic belief is rationally impermissible’, as de jure objections claim. Conceptually, the challenge is twofold. First, if standard neo-Calvinist epistemology’s claim about theistic belief’s rationally compelling basis is actually true – namely, God has globally distributed rationally compelling basis for theistic belief by sensus divinitatis or other means – this renders factors like Marx’s opium of the people either false or irrelevant (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 2; Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 184). As Calvin himself remarked on certain de jure objections of his time, ‘it is most absurd, therefore, to maintain, as some do, that religion was devised by the cunning and craft of a few individuals, as a means of keeping the body of the people in due subjection. […] Some idea of God always exists in every human mind’ (Calvin Reference Calvin1536, Book I Ch. 2). Or, as Plantinga argues in a harsher way, ‘According to Marx and Marxists, of course, it is belief in God that is a result of cognitive disease, of dysfunction. […] According to the [neo-Calvinist] model, it is really the unbeliever who displays epistemic malfunction; failing to believe in God is a result of some kind of dysfunction of the sensus divinitatis’. (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 184; italics added).

Second, modal Calvinism argues that regardless of whether God exists in the actual world, the Calvinist conditional could still stand as a conditional modal truth. Namely, it could remain true that theistic possible worlds exhibit neo-Calvinist epistemology and thus the above phenomena described by Calvin and Plantinga. If this is correct, the rational permissibility of both theism and atheism is contingent upon whether God exists in the world in question; the de jure project of determining the former issue independent of the latter is doomed to failure. As Plantinga puts it, ‘If Christian belief were false, perhaps Freud would be right; but the de jure objection was supposed to be independent of its truth or falsehood; hence this is not a successful de jure objection’ (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 498). In light of this, Russell’s hypothetical response is deemed groundless since he is already in God’s presence, which proves theism’s rational compellingness in that world. Hence, Hendricks, a follower of Plantinga, remarks that even this conditional second case is ‘costly for atheists’ (Hendricks Reference Hendricks2021, 31; original emphasis). Our discussion focuses on this second, modal Calvinist challenge.

Interestingly, as Hendricks (Reference Hendricks2021) recently argues, many atheists, particularly proponents of the divine hiddenness argument, also commit themselves to modal Calvinism’s conditional proposition (see also Curtis Reference Curtis2021). The divine hiddenness argument is another influential argument against God: a certain divine attribute would lead God to actively prevent rational people from nonbelief, and thus, the existence of rationally based nonbelievers undermines God’s existence (e.g., Drange Reference Drange1998; Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006; Oppy Reference Oppy2013; Philipse Reference Philipse2014; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993). For instance, Schellenberg (Reference Schellenberg1993) argues that God’s perfect love, which seeks explicit personal relationships with humans, plays this role (see also Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006). Hendricks notes that this argument commits to the Calvinist conditional by presupposing the premise, ‘if God exists, reasonable non-belief does not occur’ (Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993, 7; original quote), thereby also entailing that if God exists, God would ensure that theistic belief is globally rationally compelling in one way or another (Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993, ch. 2).

In what follows, through a series of nested responses rooted in probabilistic, modal, and logical analyses, we will argue that modal Calvinism poses no real concern for (almost) any atheists, as the Calvinist conditional does not actually eliminate the conceptual space for de jure objections.Footnote 5 Note that we set aside distinctions between rationality and reasonableness, as these terms are often used interchangeably in the relevant literature (e.g., Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 3). Rational permissibility is, for our purpose here, understood here according to the general conception in epistemology: a belief is rationally permissible if it possesses justified or warranted grounds in the absence of overriding defeaters. Rational compellingness, then, obtains when those justified or warranted grounds are so overwhelmingly strong and unequivocal that the belief is irresistible to a well-functioning agent using rational means. In contrast, rational impermissibility characterizes a belief that is unreasonable or irrational, either because it lacks sufficient justified or warranted grounds or because it persists despite overriding defeaters. (Note that the absence of overriding defeaters is widely considered a necessary condition for justification or warrant, regardless of whether the grounds themselves are well-founded or properly functioning.) Thus, our discussion generalizes to the varying understandings of justified or warranted grounds among different authors. For instance, Schellenberg (Reference Schellenberg1993) is more concerned with internalist justification, whereas Plantinga (Reference Plantinga2000) is more concerned with externalist warrant. This generalization is important because the background disagreement is ongoing in the relevant fields such as epistemology (see a survey in Pritchard Reference Pritchard2016), and this paper is not Plantinga (or Calvin) scholarship but rather a general investigation into modal Calvinism – a framework whose key conditional proposition is shared by many current theists and atheists. Of course, whether one accepts externalism or internalism may influence how one evaluates particular de jure objections. For instance, under Plantingian externalism – where the rational permissibility and compellingness of theism primarily depends on divinely bestowed external cognitive faculties – the Russellian ‘no evidence’ objection might lack relevance (even in the actual world and atheistic possible worlds), as it focuses on internally accessible evidence. In contrast, evolutionary debunking arguments specifically question the belief-forming mechanisms external to the subject, and might thus provide a more effective challenge. Nonetheless, our task here is simply to assess the general logical and conceptual possibility of de jure objections in the face of modal Calvinism’s challenge, not to evaluate the respective merits of each particular objection. Any upcoming references to specific objections, such as the Russellian or Marxist ones, are merely illustrative and carry no particular emphasis.

For sake of evaluating such general logical and conceptual possibility, we will assume that certain de jure objections possess substantial independent evidential or argumentative grounds and are not question-begging – despite complaints against some such objections (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 368; Murray Reference Murray, Bulbulia, Sosis, Genet, Genet, Harris and Wyman2008) – to evaluate their relationship with the Calvinist conditional. If a de jure objection is itself question-begging, the conditional should not be the atheist’s primary worry.

This article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we assess some interesting responses to modal Calvinism by other philosophers and argue that further discussion is needed despite the plausibility of these responses. Sections 3 and 4 differentiate between the probabilistic and logical versions of modal Calvinism and offer corresponding criticisms. Finally, Section 5 provides our final remarks.

Case already closed? A hidden worry persists

Curtis (Reference Curtis2021) criticizes modal Calvinism for addressing only theistic possibilities where God exists, as per the ‘whether or not God exists’ antecedent of de jure objections. Specifically, there would be no issue with those supposed sources of theistic belief’s rational impermissibility if God does not exist. Atheists can accept the Calvinist conditional while still embracing specific arguments commonly labelled as ‘de jure objections’, provided they give up characterizing them as such. For modal Calvinism per se provides no arguments or evidence to disprove their soundness.

Another related possible response to modal Calvinism, suggested in personal correspondence by several colleagues from other fields, is that philosophers of religion need not follow Plantinga in interpreting the de jure antecedent as a modal conditional that captures both theistic and atheistic possibilities – whether such possibilities are metaphysical, logical, or epistemic.Footnote 6 Instead, it could be understood as an isolating approach in argumentation, where the question of whether theism or atheism is true is temporarily set aside when evaluating the independent arguments or evidence presented by de jure objections. If the conclusion of such objections ends up being inconsistent with theism, so be it.

We find Curtis’s and these colleagues’ views plausible, but see room for further analysis: the Calvinist depiction of theistic possibilities should not be taken for granted. First, it remains a substantial philosophical interest as to whether the truth of theism – if true – disproves the conclusion of any de jure objection, specifically the claim that theistic belief is rationally impermissible. Plantinga and his followers hold this view, but we disagree, whereas the above critics divert their attention from this issue. Second, and perhaps more importantly, accepting the Calvinist depiction leads atheists to a further troubling conclusion not previously recognized by both sides of the debate: if atheism is mistaken about the actual world and God exists, they would be deemed fiercely irrational, corrupted, and self-deceptive due to sin, according to their own beliefs. This is too much of a concession and breeds unnecessary sceptical scenarios. For many atheist and other non-theist thinkers accept a considerable probability of God’s existence (e.g., Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993, 46–47; Draper Reference Draper, D and Moser2002), which makes the question ‘what if God exists?’ rather legitimate and worthy of consideration. Contrary to the modal Calvinist stance of Plantinga and his followers, we will argue that even assuming the Calvinist conditional, Russell(’s nonactual counterpart) in a theistic world could be rational: he could (1) maintain some reasonable de jure objection while (2) remaining rational himself. Note again that Russell is presented here merely as an illustrative figure – a person who proposed an apparently plausible de jure objection and then encounters God – and nothing hinges on whether the specific ‘no evidence’ objection he actually used in history is itself compelling.

The probabilistic Calvinist conditional

Our responses vary based on different interpretations of the Calvinist conditional, ‘If God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and there are no rationally based non-believers.’ Specifically, we differentiate between its logical and probabilistic versions, which parallel the standard distinction between the two versions of the problem of evil. A logical conditional asserts it as a logical (or conceptual) necessity that God would eliminate evil or ensure theism’s rational compellingness (e.g., McCloskey Reference McCloskey1960; Mackie Reference Mackie1955; Oppy Reference Oppy, Meister and Moser2017). In other words, the conditional can be restated in this form:

Necessarily, if God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and there are no rationally based non-believers.

Or in this alternative form:

If God exists, it necessarily follows that theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and that there are no rationally based non-believers.

A probabilistic conditional allows for the possibility that God might, partially or fully, refrain from this, though it maintains that God probably acts thusly. For despite potential outweighing reasons God may have for non-action, their existence is improbable (e.g., Rowe Reference Rowe1979; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993; Drange Reference Drange1998; Oppy Reference Oppy2013; Philipse Reference Philipse2014; cf. Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006). With this in mind, the conditional can be restated in this form:

Probably, if God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and there are no rationally based non-believers.

Or in this alternative form:

If God exists, theistic belief is, probably, globally rationally compelling, and there are probably no rationally based non-believers.Footnote 7

We will argue that atheists need not worry about either the logical or the probabilistic versions, even if they find themselves committed to them.

Plantinga emphasizes his acceptance of the probabilistic, not the logical, conditional (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 189–190). While Hendricks correctly notes that many atheists’ divine hiddenness argument commits to the above Calvinist conditional, it is also worth noting that the literature largely applies the probabilistic conditional (Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993, 9, 86–87; Drange Reference Drange1998, 26; Oppy Reference Oppy2013, 84; Philipse Reference Philipse2014, 304) – presumably because many think that Plantinga’s Reference Plantinga(1974) famous objection to the logical problem of evil similarly applies to any logical hiddenness argument, rendering it untenable.

However, the modal Calvinist critique of de jure objections seems to overlook the probabilistic factor, which involves certain complexities. To address this, we must first examine the semantic meanings of the probabilistic statements in question. The relevant semantics can be interpreted philosophically in terms of modality or credence.Footnote 8 Many metaphysicians and metaphysically-minded philosophers accept the modal interpretation, which, very broadly and roughly speaking, holds that the probability of a proposition is the proportion of possibilities where it is true among the possibilities where the relevant background or evidence holds, though the specific technical constructions of such possibilities vary among theorists (Bigelow Reference Bigelow1976; van Inwagen Reference van Inwagen2001; Tooley Reference Tooley2011; cf. Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 190). In contrast, many others accept the subjective interpretation, an epistemic notion that concerns credence – namely, how certain a real or ideal subject is of a proposition given their beliefs (Myrvold Reference Myrvold2021; Ramsey Reference Ramsey and Braithwaite1931). Both interpretations are well-received in the literature. However, the probabilistic Calvinist conditional, when interpreted solely through the lens of credence, would concern one’s credence in the logical Calvinist conditional, which is rooted in one’s lack of complete certainty in accepting it. The next section will discuss the logical conditional per se. For the purposes of this section, we will focus on the modal interpretation, which views probability as a metaphysical truth referenced by a proposition.

Given the modal interpretation of probability, however, the propositions ‘God exists’, ‘if God exists, theistic belief is probably rationally compelling’, and ‘theistic belief is rationally impermissible’ are compatible. Similarly, ‘God exists’, ‘if God exists, there are probably no rationally based non-believers’, and ‘there are rationally based non-believers’, and are also compatible. Suppose that each possibility can be understood in terms of a possible world, as most philosophers assume. The probable rational compellingness of theistic belief in theistic worlds, interpreted here as the rational compellingness of theistic belief in most theistic worlds, does not entail its rational compellingness in any such world. There are exceptional theistic worlds where God, partially or wholly, refrains ensuring from theistic belief’s rational compellingness and even permissibility.

After all, following the standard literature on the problems of evil and hiddenness (e.g., Rowe Reference Rowe1979; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993, 86-88; Drange Reference Drange1998, 205; Oppy Reference Oppy2013, 72; Philipse Reference Philipse2014, 304), if one applies a probabilistic Calvinist conditional that refers to the relevant probability as a metaphysical truth, one should acknowledge the following possibility: to enable certain goods or to prevent certain evils – perhaps inscrutable ones – God may, partially or entirely, refrain from ensuring theistic belief’s rational compellingness, or even from providing a rational basis for it. Additionally, certain theodicists’ attempts to explain divine hiddenness may help to illuminate these possible goods or evils: for example, it has been suggested that God may consider remaining hidden to preserve our cognitive freedom, our ability to make life choices, and other related factors (see surveys in Howard-Snyder and Green Reference Howard-Snyder, Green, Zalta and Nodelman2022; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993). Such conditions may be rare among theistic worlds, yet occur in some specific theistic worlds. Ultimately, if one finds none of these possibilities plausible even as mere possibilities, then one should hold the logical conditional rather than the modally interpreted probabilistic conditional, with any uncertainties attributed to imperfect subjective credence. In contrast, if one does not consider these possibilities as improbable but rather as probable or having indeterminable probabilities – a stance some theodicists may take – no Calvinist conditional should be held.

Given the above considerations, the success of any independent atheistic argument in showing theism’s rational impermissibility or atheism’s rational permissibility would imply that even if we reside in a theistic world, it would (probably) be among the exceptional theistic worlds described above.

With the metaphysical dimension of the problem resolved, we can now address the epistemic dimension. The question is whether de jure objections can ever succeed despite the fact that the probabilistic Calvinist conditional assigns a low probability to theistic belief’s rational impermissibility. The consideration here would involve two key factors: (i) the evidential or argumentative strength of a de jure objection per se, and (ii) the probability or improbability that theistic belief is rationally impermissible if theism is true, before considering the de jure objection in question. The probability here can be understood in terms of the Bayesian method, in which the final, posterior probability of a de jure objection’ success is constituted by two variables corresponding respectively to the above factors: (i) the likelihood ratio of the evidence and (ii) the prior probability of the hypothesis. Applying the Bayesian method to our case is somewhat nonstandard because the method typically concerns evidence evaluation, while it is not clear that hypothetically adding the existence of God to our known world changes the existing body of evidence. Nonetheless, for our purpose here, we can assume that God’s existence and the probabilistic Calvinist conditional are part of the background information that constitutes the prior probability of the hypothesis. The relevant technical details are provided in Appendix A, although the conceptual discussions here are sufficient for understanding the ideas presented.

To begin with, any challenge that the Calvinist conditional poses to the success of de jure objections arises from its role in shaping the background information that informs the prior probability of theistic belief’s rational impermissibility, rather than from altering the evidential or argumentative strength of the objections themselves. Recall that our discussion addresses only modal Calvinism, not the actual world version of neo-Calvinism. Borrowing Curtis’s point (see Section 2), since the Calvinist conditional per se functions as a mere modal conditional proposition – unlike the actual-world version of neo-Calvinism that aims to assert how things actually are – it provides no direct counterarguments against the evidence or reasoning of specific atheistic arguments presented by Marxists, Freudians, Hume, Kant, Dennett, Oppy, or evolutionary debunkers. Hence, as long as the premises of a de jure objection can be assessed independently and do not already presuppose atheism, the Calvinist conditional alone cannot falsify or cast doubt on its plausibility. Or at least, this is how we should consider its initial plausibility, before further background information is weighed against it – a discussion that we will address next. (Consider an analogy: the conditional proposition that ‘if God exists, there are probably no unicorns’ does not, on its own, indicate any flaw in the evidence provided by seeing a unicorn; rather, the proposition functions only together with a background assumption that God exists to lower our confidence in this evidence.) Accordingly, we can just maintain our starting assumption for discussion’s sake that such objections are sufficiently independent and substantive, with any alleged failures considered as separate issues.

The more interesting issue concerns the low prior probability assigned to any de jure objection within a theistic model, especially in light of what can be called the ‘extraordinary claim objection’. This objection draws on astronomer, popular science writer, and religious skeptic Carl Sagan’s famous aphorism against pseudoscience, ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence’, (Sagan Reference Sagan1979, 62; see also Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne, Zalta and Nodelman2018) – and also seems to turn Hume’s (1748/Reference Hume2007) famous probabilistic argument against miracles on its head. Assuming that the aphorism is correct, the probabilistic Calvinist conditional might seem to suggest the following: since the rational impermissibility of theistic belief is very improbable among theistic worlds, exceptionally strong evidence is required to confirm it. In Bayesian terms, given the very low prior probability of theistic belief’s rational impermissibility, the evidence must have a very high likelihood ratio to constitute a reasonable posterior probability (Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne, Zalta and Nodelman2018). (See, again, Appendix A for a formal presentation though it is not needed for understanding.) Thus, there is a huge disparity of evidential standards in theistic and atheistic worlds, despite any independent evidence or argumentation that a de jure objection could have offered.

As interesting as the extraordinary claim objection might be, it has a crucial mistake: the probabilistic Calvinist conditional merely reflects the low probability that theistic belief is rationally impermissible under unspecified theistic conditions, which does not equate to the prior probability here. We are considering the hypothetical situation in which our world turns out to be theistic. The prior probability of the hypothesis that theistic belief is rationally impermissible then depends on all available background information, rather than just one’s existence in theistic or atheistic worlds. Such background information involves various aspects of our knowledge. Here, allow us to introduce an important factor therein, which will be referenced repeatedly throughout this paper in different contexts: our accepted standard knowledge (henceforth, ASK) of the world. It is the standard, established public worldview normally held by well-informed individuals, which incorporates conventional sociological, historical, scientific, and common-sense understandings.

Most people acknowledge the existence of ASK or something similar. Sociologists, following Berger and Luckmann (Reference Berger and Luckmann1966), commonly believe that certain standard common-sense knowledge – interpersonal, humanistic, and scientific – helps ground our social reality and institutions. Christian philosopher Quinn has the famous idea of ‘the intellectually sophisticated adult theist in our culture’ (Quinn Reference Quinn and Zagzebski1993, 35; see also a discussion in Aijaz Reference Aijaz2024), whose intellectual sophistication includes a good deal of knowledge about non-believers and their ideas. Plantinga likewise has the idea of ‘what we know’, which is defined as ‘what all (or most) of the participants in the discussion agree on’ (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 169). While some radical religious or spiritual thinkers may reject ASK due to their reservations about the secular, this move can at best be seen as adopting nonstandard, though not necessarily implausible, extreme views akin to philosophical scepticism – views that atheists, our protagonists here, may set aside at least in our current context.

The key point here is that ASK clearly recognizes certain common-sense factors that conflict with neo-Calvinism, as the critics of the actual-world version of neo-Calvinism mentioned in Section 1 have all emphasized (Launonen Reference Launonen2021, Reference Launonen2025; Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006; Philipse Reference Philipse2014; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993). For example: (1) countless rationally based non-believers with good moral, psychological, and intellectual statuses indeed exist;Footnote 9 (2) even many of the most morally and intellectually exemplary theists struggle to find reasonable grounds for theistic belief, with some openly acknowledging this struggle and others ultimately compelled to abandon their faith for the rest of their lives; and (3) exposure to theism almost exclusively occurs through cultural transmission, a demographically and historically local phenomenon, with countless individuals having no relevant opportunities. The long quote by Calvin at the beginning is demonstrably false.Footnote 10 These considerations are not simply some atheists’ self-assumption of being reasonable or a question-begging move. This aspect of ASK receives overwhelming support from the accepted sociology of religious diversity, which takes into account numerous demographic characteristics of various religious and non-religious groups (cf. Hick Reference Hick and Badham1990; Maitzen Reference Maitzen2006). Many theist philosophers, theologians, and religious institutions accept this, often describing our world as itself ‘religiously ambiguous’ from a theological perspective (see Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993; Howard-Snyder and Green Reference Howard-Snyder, Green, Zalta and Nodelman2022 for detailed surveys).

This suggests that our world has already been confirmed to exhibit a wide range of traits that the probabilistic Calvinist conditional deems improbable and extraordinary, even if theism is true. In other words, if God actually exists, he has almost certainly adopted hiddenness policies that are improbable from the neo-Calvinist perspective. Hence, while de jure objections posit more general theistic irrationality that is indeed extraordinary among theistic worlds, this extraordinariness is merely a moderate extension of the ASK-confirmed extraordinariness of our world: it simply suggests that the confirmed violation of neo-Calvinism is more widespread and intense.Footnote 11 Viewing from this lens, the rational impermissibility of theistic belief should not be considered excessively improbable or extraordinary given a prior probability that takes into account ASK.

Interestingly, Plantinga claims that his actual-world version of neo-Calvinism is ‘epistemically possible’ in the sense that it is consistent with his notion of ‘what we know’ (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 169). Presumably, he would not agree that such knowledge, when combined with the probabilistic Calvinist conditional, would render our world improbable among theistic worlds – even though improbability remains compatible with possibility. Plantinga does not elaborate this stance much, except for a brief association with his view that any objection to his neo-Calvinism must automatically be an objection to theism itself (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 169) – a view explicitly rejected by a number of serious theist thinkers (e.g., Aijaz Reference Aijaz2024; Quinn Reference Quinn and Zagzebski1993). In any case, however, recall that he defines ‘what we know’ as ‘what all (or most) of the participants in the discussion agree on’ (Plantinga Reference Plantinga2000, 169), with these participants presumably including a variety of monotheists, polytheists, spiritualists, atheists, agnostics, and others. The agreement here can be interpreted as actual agreement, normal agreement, or what should be agreed upon. If ‘what we know’ is only about actual agreement, it would almost by definition ignore empirical facts that contradict neo-Calvinism, simply because some neo-Calvinist participants in the discussion, such as Plantinga himself, disagree. This is trivial and unhelpful. However, if interpreted as normal or should-be agreement, ‘what we know’ would resemble ASK, consisting of the confirmed, well-established, and publicly acknowledged elements of human knowledge. Relevant points have been repeatedly emphasized by many critics, both theists and atheists (e.g., Aijaz Reference Aijaz2024; Quinn Reference Quinn and Zagzebski1993; Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg1993).

Considering all the above metaphysical and epistemic factors, the probabilistic Calvinist conditional offers no obstacles to maintaining a reasonable de jure objection: it does not rule out theistic worlds where theistic belief is rationally impermissible, and a good de jure objection could place our actual world among such worlds through plausible probabilistic estimation. This reasoning can also be applied to assess the rationality of Russell (or his counterpart). When he employed a de jure objection to justify his non-belief, he could be responding rationally and accurately to his conditions. He just encounters a God who, given the states of affairs of his world, would not be rationally permissible to believe in, yet nevertheless exists in that world, an outlier world among various theistic worlds.Footnote 12 Furthermore, given our previous discussion, even now facing God – a new definite proof of God’s existence – he could still consider himself rational, despite atheists being probably irrational in theistic worlds. For probabilistic reasoning depends on all available data, rather than just his existence in theistic worlds.

To conclude, since (almost) all sophisticated atheist thinkers would, of course, believe they have sufficient independent rational justification for atheism, and that the probabilistic Calvinist conditional poses no threat to the logical space of such a belief, (almost) none of them should be worried about this conditional.

The logical Calvinist conditional

Considering modal and logical factors, the logical Calvinist conditional also should not worry any atheist. Here, we will offer a different line of response. Recall that, according to this conditional, it is logically necessary that ‘if God exists, theistic belief is globally rationally compelling, and there are no rationally based non-believers’. Schellenberg (Reference Schellenberg2015) recently offers an in-depth defence of this conditional, and, as argued in the previous section, those who reject the modal interpretation of the probabilistic conditional in favour of a purely subjective interpretation may have implicitly endorsed it as well. Unlike the probabilistic formulation, this conditional seems to leave no logical space for de jure objections. However, further investigation reveals a more complex relationship between them.

To begin with, if the logical conditional is true, it should in fact reassure the atheist: from their perspective, rationally based non-believers obviously exists! This is further supported by the validation from ASK, which many theists also share. Since p→ ![]() $\neg $q (if God exists, then there are no rationally based non-believers) is logically equivalent to q→

$\neg $q (if God exists, then there are no rationally based non-believers) is logically equivalent to q→ ![]() $\neg $p (if rationally based non-believers exist, then God does not exist), the conditional would, by simple modus tollens, entail an equivalent logical divine hiddenness argument under which the existence of any rationally based non-believers logically precludes God’s existence (as seen in Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg2015, 6-8). The problem posed for theism here is much more severe than with the probabilistic conditional. As a necessity claim, the logical conditional, unlike its probabilistic counterpart, allows for no exception: there cannot be any exceptional theistic worlds where the conditional does not apply, nor can there be a few exceptional cases within a theistic world where the conditional does generally apply. Hence, the logical conditional leads to a logical incompatibility between ASK and God’s existence.

$\neg $p (if rationally based non-believers exist, then God does not exist), the conditional would, by simple modus tollens, entail an equivalent logical divine hiddenness argument under which the existence of any rationally based non-believers logically precludes God’s existence (as seen in Schellenberg Reference Schellenberg2015, 6-8). The problem posed for theism here is much more severe than with the probabilistic conditional. As a necessity claim, the logical conditional, unlike its probabilistic counterpart, allows for no exception: there cannot be any exceptional theistic worlds where the conditional does not apply, nor can there be a few exceptional cases within a theistic world where the conditional does generally apply. Hence, the logical conditional leads to a logical incompatibility between ASK and God’s existence.

ASK is also crucial to interpreting the ‘whether or not God exists’ antecedent of de jure objections. It is standard practice to interpret antecedents modally – and the standard evaluation of the rationality of an agent’s choices also has a modal element. Building on the relevant discussion in the previous section on the probabilistic conditional – though framed in Bayesian reasoning rather than possible world semanticsFootnote 13 – this antecedent should refer to the set of worlds that our world could possibly turn out to be. But what is this set of worlds? Obviously, the antecedent cannot be referring to all possible worlds, nor can it mean all worlds where the suggested sources of theistic belief’s rational impermissibility exist, as not all such worlds are consistent with what we know about our world – let alone the fact that this would absurdly include heavenly worlds with overwhelming miracles and revelation, in which it is obviously not rationally impermissible to believe in God. It may mean all nearby worlds, yet determining the appropriate measure of distance poses challenges. Metaphysical and structural similarities might not be adequate, because God and other supernatural agents’ presence and activities already distinguish theistic from atheistic worlds significantly, and that most de jure objections predominantly concern certain human conditions or experiences rather than objective cosmic structures. Hence, a simple and fitting interpretation is that believing in God is rationally impermissible in all worlds where ASK is true. This means that the ‘even if God exists’ disjunct of the ‘whether or not God exists’ antecedent refers to worlds where God exists and ASK holds.Footnote 14

These considerations, when combined, have a notable logical implication. Recall that the logical Calvinist conditional leads to a logical incompatibility between ASK and God’s existence, and that the ‘even if God exists’ disjunct of the antecedent is best understood as referring to worlds where God exists and ASK holds. Together, these render the disjunct impossible.

How should the atheist interpret this logical outcome? We think that it leads to two possible interpretations of the logical Calvinist conditional’s implications for de jure objections, with the selection depending on the reader’s view on logic and modality.

The first interpretation takes for granted the standard view of inconsistent scenarios, which considers them unassertable or trivial. Specifically, if the logical Calvinist conditional is true, arguments labelled as de jure objections have to drop their signature antecedent, as Curtis argues. However, this should not concern any atheist. Following our discussion of the antecedent, we take it that these so-called de jure objections have an implicit purpose: to posit theistic belief’s rational impermissibility under different serious possibilities worth considering, interpreted here as worlds where ASK holds. Under the modal Calvinist philosophers’ view, if the logical conditional is true, de jure objections fail to correctly capture the relevant theistic possibilities, namely theistic ASK worlds. However, following our analysis, if the logical conditional is true, there are simply no theistic worlds among ASK worlds: no God exists in such worlds. Thus, so-called de jure objections could still achieve their purpose – namely, to capture all ASK worlds. After all, these objections, unlike the theist, bear no responsibility for the theistic worldview’s possibility or impossibility. As for Russell’s case, he is just wrong to even engage with the hypothetical question at all: since there are no such relevant worlds, he (and his counterparts) will never meet God. There is no need to worry about him (and his counterparts) being irrational.Footnote 15

The above interpretation of the logical Calvinist conditional’s implications for de jure objections is fatal; readers who find it convincing, as one of the authors does, may stop here. However, its dismissal of impossible theistic scenarios as unassertable and trivial might seem overly dismissive, independent of theistic or atheistic positions, making another option worth discussing. For example, believers who think God necessarily exists might still consider purportedly impossible atheistic scenarios like life’s meaninglessness. Similarly, skeptics of theism’s coherence can consider purportedly impossible theistic scenarios, such as the anticipated elimination of evil. Likewise, even for those who find the theistic worldview impossible, such as those who endorse the logical problems of evil and hiddenness, hypothetical theistic scenarios appear to hold significance, as evidenced by these philosophers’ extensive engagement with theistic perspectives. Beyond religion, useful inconsistent languages and hypotheses are found in everyday life and science. Furthermore, dialogues with those who overlook certain inconsistencies are unavoidable, and sometimes we may be the ones who are mistaken (for similar considerations, see Nolan Reference Nolan1997; Wilson Reference Wilson2021). Hence, intuitively and pragmatically, there is a strong independent need to allow some such claims to be assertable, applicable, and to stand – at least theoretically – as nontrivial truths. For these and other reasons, many contemporary philosophers have turned to non-trivial interpretations of ‘counterpossibles’, where some are non-trivially true while others are non-trivially false (e.g., Nolan Reference Nolan1997; Berto Reference Berto2010; Berto and Jago Reference Berto and Jago2019; Bjerring Reference Bjerring2014; Wilson Reference Wilson2021).

The question then arises: assuming that a theistic worldview inconsistently includes both God and ASK, could de jure objections or modal Calvinism be right about the relevant counterpossible scenarios?

Let us first sketch our conclusion very roughly in plain language before going into its formal details. We are assuming that God and ASK are contradictory. Hence, to illustrate counterpossible scenarios where both are found, one needs to suspend the logical status and implications of the logical Calvinist conditional, which underlies the inconsistency. (Or, to borrow Husserl’s famous term, one needs to ‘bracket’ the conditional.) However, it is precisely this suspended conditional that the modal Calvinist uses to undermine the de jure proposition, ‘(given ASK,) even if God exists, it would be rationally impermissible to believe in God’. Thus, de jure objections could still work in the relevant counterpossibles, and the atheist need not worry that counterpossibles can salvage the modal Calvinist’s stance. The basis of our assertion will become clearer if formal philosophy provides a plausible framework which treats the relevant claims as such.

Following Restall (Reference Restall1997), we methodologically apply Priest’s (Reference Priest1991) minimally inconsistent LP approach as a basis for counterpossible reasoning (consider also Beall’s (Reference Beall2021, Reference Beall2023) application in theological reasoning), without ontologically committing to the existence of objective contradictions as Priest famously and controversially does. The approach’s technical details are in Appendix B, as we focus on conceptual discussions. To begin with, the logic of paradox (LP), a three-valued logic, introduces a third value, b, representing ‘both-true-and-false’. This makes LP a paraconsistent logic, wherein contradictions do not imply arbitrary propositions. LP serves as an excellent tool for reasoning with inconsistencies, though many philosophers, preferring consistency, apply it begrudgingly.

Minimally inconsistent LP (LPm) is thus designed to minimize inconsistency. LPm extracts classical consequences from consistent portions of assumptions, unlike LP, and avoids allowing that anything follows from inconsistent assumptions, unlike classical logic. For example, given the premises (i) God exists, (ii) God does not exist, (iii) if grass is green, then snow is white, and (iv) grass is green, one can validly conclude that snow is white using LPm, but not with LP.

Philosophical interpretations of LP models vary. Importantly, we should reiterate that employing paraconsistent logic requires no ontological commitment to impossibilia. As Priest (Reference Priest2005, ch. 7) suggests, even without such commitment, adherence to strict consistency is not a mandatory requirement for reasoning. LP models can be seen as depicting inconsistent or impossible worlds (in the sense of Nolan Reference Nolan1997 or Berto and Jago Reference Berto and Jago2019). A model assigning the atom p the value b illustrates a scenario in an impossible world where p is both true and false. Note that this does not imply an ontological commitment to impossible worlds as with other worlds, since such worlds may simply be theoretical constructs (Berto and Jago Reference Berto and Jago2019; cf. Nolan Reference Nolan1997). Alternatively, without endorsing impossible worlds, one may follow Restall (Reference Restall1997) and consider LP models as sets of consistent worlds, illustrating inconsistent collections of individually consistent information.

Assuming that the Calvinist conditional (henceforth, C) is true, to engage in general discussions on God in ASK’s context, one has to quarantine the inconsistency between God and ASK. Specifically, one needs to quarantine C. By employing a suitable LPm model, one can have a world where ASK and God’s existence are considered true simultaneously while C is considered contradictory, namely, being assigned the contradictory value b.Footnote 16 Under this setup, since the reasoning of de jure objections leading from claims about, say, Marx’s opium of the people to theistic belief’s rational impermissibility does not involve C, it will not take the value b and is thus available to classical reasoning. Similarly, considerations of other divine actions remain unaffected. However, without involving implications of C, such actions do not necessarily counteract the rational impermissibility of theistic belief. The reader may consult Appendix B for the formal basis of the logical inference above, but the key idea at the conceptual level is that such inferences need not involve the quarantined information. In other words, de jure objections’ argumentation can proceed normally, as can any anticipations of divine actions that are not found on C, with adequate conclusions considered true.

Of course, based on C, one could anticipate God’s interventions to the rational impermissibility of theistic belief. Nonetheless, if derived solely from conjunctions involving C, propositions concerning these interventions and their outcomes (such as Calvin and Plantinga’s ideas of sensus divinitatis and the holy spirit’s testimony, along with the rational support to theism that they provide) can likewise be assigned the value b and logically sidestepped. Therefore, when assessing a de jure objection, the atheist can focus on the potential source of theistic belief’s rational impermissibility, without considering the logical Calvinist conditional C and the issue of divine revelation that it implies.Footnote 17

Finally, two assessments of Russell(’s counterpart)’s rationality are available. We will focus on whether he could reasonably apply de jure objections, rather than how he should think about the logical Calvinist conditional, as our interest lies in the logical space for his rationally based non-belief, not the appropriate reactions when facing peculiar impossibilia. Assuming impossible worlds, Russell(’s counterpart) could be in one such world and responding correctly to available evidence, specifically some de jure objection, during his lifetime and in his afterlife confrontation with God, despite contradictions with any divine countermeasures that C might suggest. Alternatively, under Restall’s approach, which views impossibilities as combinations of consistent information sets, Russell(’s counterpart)’s response remains appropriate. Within one consistent body of secular and naturalistic information, he reasoned correctly based on the evidence available therein, and this remains true when integrating the other information set involving God, provided that C and its derivations are logically contained.

Final remarks

To answer the title question, (almost) no sophisticated atheist thinkers with substantial arguments need to worry about modal Calvinism. Modal Calvinism is either probabilistic or logical, yet for different reasons, neither form can compel sophisticated atheist thinkers to believe that serious theistic possibilities worth considering, from their perspective, would involve the rational compellingness of theistic belief. Of course, our conclusion is compatible with theism being true and rationally permissible or compelling while all de jure objections remain implausible, but it shows that de jure objections have to be countered on different grounds.

Finally, with perhaps some minor modifications, our arguments apply generally against attempts by non-theistic religious worldviews to adopt the modal Calvinist strategy against de jure objections (e.g., Gupta Reference Gupta2022). Since these worldviews do not always posit a transcendental entity with the full range of omni-properties held by a theistic God, which provide infinite resources and resolve to ensure the rational permissibility or compellingness of belief, our analysis of the probabilistic Calvinist conditional is likely applicable. And for worldviews that specifically posit necessary and clear revelation, our analysis of the logical Calvinist conditional applies directly. A broader lesson to take away may be that certain judgments concerning human reason, if sufficiently independently defended, are not as easily relativized by competing overarching worldviews as some neo-Calvinists and other philosophers might suggest.

Appendix A. Bayesian probability

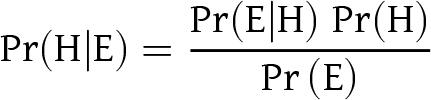

We use the following standard Bayesian theorem:

\begin{equation*}{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}}\vert{\text{E}}) = \frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert {\text{H}})\;{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}}\vert{\text{E}}) = \frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert {\text{H}})\;{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}\end{equation*}Pr(H|E) is the posterior probability of hypothesis H given evidence E. Pr(H) is the prior probability hypothesis H before considering evidence E. Pr(E|H) is the likelihood of finding evidence E given that hypothesis H is true. Pr(E) is the expectedness of the evidence, namely, the likelihood of evidence E under various relevant alternative hypotheses. Following the discussion of the probabilistic Calvinist conditional in Section 3, hypothesis H represents that the scenario that theistic belief is rationally impermissible. Evidence E represents the arguments or evidence provided by a de jure objection, such as the empirical sociological evidence that supports Marx’s ‘opium of the people’ critique. To assess the probability of a de jure objection under the scenario that God exists, we hypothetically include God’s existence and the probabilistic Calvinist conditional as two pieces of background information when determining Pr(H), alongside other standard background information such as what we already know about our world.

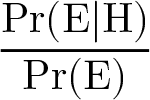

The strength of evidence E is then measured by this likelihood ratio in the theorem:

\begin{equation*}

\frac{Pr(E\vert H)}{Pr(E)}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{Pr(E\vert H)}{Pr(E)}\end{equation*}This ratio tells how likely evidence E is found under the hypothesis in question (namely, Pr(E|H)) compared to its general likelihood under various relevant alternative hypotheses (namely, Pr(E)), with these alternative hypotheses representing various possibilities in which it is not the case that theistic belief is rationally impermissible. If the ratio is greater than 1, then E is more likely under H than it is under various alternative hypotheses; this supports H. If the ratio is less than 1, then E is less likely under H than it is under various alternative hypotheses; this counts against H.

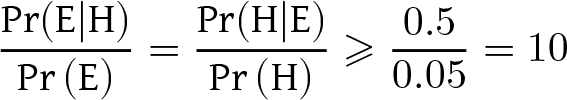

Sagan’s famous aphorism in the text, ‘extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,’ can be interpreted as follows. According to the Bayesian theorem stated above, Pr(H|E) =  $\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})\;{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$, if prior probability Pr(H) is very low, the likelihood ratio

$\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})\;{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$, if prior probability Pr(H) is very low, the likelihood ratio  $\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert {\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$ must be very high for P(H|E) to be reasonable (Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne, Zalta and Nodelman2018). For instance, if Pr(H) = 0.05, we then need

$\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert {\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$ must be very high for P(H|E) to be reasonable (Hawthorne Reference Hawthorne, Zalta and Nodelman2018). For instance, if Pr(H) = 0.05, we then need  $\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$ ≥ 10 to achieve Pr(H|E) ≥ 0.5, as shown by simple algebraic calculation:

$\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}}$ ≥ 10 to achieve Pr(H|E) ≥ 0.5, as shown by simple algebraic calculation:

\begin{equation*}\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}} = \frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}}\vert {\text{E}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{H}} \right)}} \geqslant \frac{{0.5}}{{0.05}} = 10\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{E}}\vert{\text{H}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{E}} \right)}} = \frac{{{\text{Pr}}({\text{H}}\vert {\text{E}})}}{{{\text{Pr}}\left( {\text{H}} \right)}} \geqslant \frac{{0.5}}{{0.05}} = 10\end{equation*}Appendix B. Paraconsistent logic

We begin by defining LP models for propositional language (Priest Reference Priest1979). An LP model V is a function assigning atomic propositions a truth value from the set {1,0,b}. Assignments are extended to the whole language via the following truth tables:

An LP model V satisfies a formula A iff V(A) is a non-zero value, and V satisfies a set of formulas X iff V assigns every member of X a non-zero value. An LP model fails to satisfy a formula B iff V(B) = 0.

A set of formulas X entails B in LP iff no model that satisfies X fails to satisfy B.

To obtain minimally inconsistent LP from this, we restrict attention to the LP models that are minimally inconsistent and satisfy X, where we say that for LP models V1, V2, V1 is less inconsistent than V2 iff, for every atom p such that V1(p)=b, V2 (p)=b. For further details, the reader should consult Priest (Reference Priest1991).

The example premises in the text, (i) God exists, (ii) God does not exist, (iii) if grass is green, then snow is white, and (iv) grass is green, can be symbolized as g, ![]() $\neg $g, p→q, p. To see the invalidity in LP of concluding q, we can consider an LP model V that assigns both g and p the value b while assigning q the value 0. This is not minimally inconsistent, however; models that only assign b to g have less overall inconsistency. Such models will ensure that q does follow from the premises.

$\neg $g, p→q, p. To see the invalidity in LP of concluding q, we can consider an LP model V that assigns both g and p the value b while assigning q the value 0. This is not minimally inconsistent, however; models that only assign b to g have less overall inconsistency. Such models will ensure that q does follow from the premises.

Acknowledgements

We presented this article at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Fudan University, Lingnan University, the University of Sydney, the Taiwan Philosophical Association conference at National Chengchi University in 2022, and the Global Philosophy of Religion Project conference at Waseda University in 2023. We would like to thank the participants for extremely helpful discussions. For further comments, we are especially grateful to Imran Aijaz, David Braddon-Mitchell, John Bigelow, Adam Bradley, Kai-Yan Chan, Duen-min Deng, Wei Fang, Ko-Hung Kuan, Andrew James Latham, Kok Yong Lee, Haoying Liu, Andy Mckilliam, J. L. Schellenberg, Qiu Wang, Wai-hung Wong, and an anonymous reviewer.

Funding

Funding was provided to both authors by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Chan’s Grant Number: 113-2628-H-002-003; Standefer’s Grant Number: 111-2410-H-002-006-MY3).