Introduction

Multiple studies have shown that the 14C age of bulk organic carbon (OC) in sediment that accumulates in lakes and other depositional settings is typically hundreds to thousands of years older than the actual age of deposition (e.g., Strunk et al. Reference Strunk, Olsen, Sanei, Rudra and Larsen2020 and references therein). The old carbon is derived from terrestrial sources including soil organic matter and petrographic carbon contained in carbonaceous rocks that are transported to the depositional site by wind, water and hillslope processes. In lakes, old carbon can also be introduced by autochthonous organic matter produced using dissolved carbon from old sources. Despite these issues, bulk-sediment 14C ages remain among the geochronological tools commonly used to date lake cores and other surficial deposits, especially where plant or other macrofossils are sparse. Indeed, Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Davidson, Lange and Wren2007) suggested that sedimentation rates derived from bulk sediment ages may sometimes be more reliable than rates determined from terrestrial macrofossils, which can yield downcore ages prone to additional variability due to differential pre-aging of various macrofossil types prior to deposition in the lake (e.g., Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Anderson, Brown, Brubaker, Hu, Lozhkin, Tinner and Kaltenrieder2005). In some studies, the age of the bulk sediment is adjusted by subtracting a constant “reservoir age,” which is estimated by dating the surface sediment or calculating the intercept age from a series of downcore ages. However, other studies have shown that reservoir ages can fluctuate through time and have cautioned against such practice (e.g., Wang et al. Reference Wang, Das, Xu, Liu, Jahan, Means, Donoghue and Jiang2019).

To improve the accuracy of 14C ages on bulk sediment, some studies have heated sediment to separate the OC into components of differing thermal stabilities and corresponding ages, with the oldest OC typically associated with CO2 generated at the highest temperatures. McGeehin et al. (Reference McGeehin, Burr, Jull, Reines, Gosse, Davis, Muhs and Southon2001) developed a stepped-combustion apparatus that regulates the heat and quantity of O2 used to generate CO2 from bulk sediment at relatively low temperature (400°C). The technique was subsequently applied in other studies (e.g., Jull et al. Reference Jull, Burr, Beck, Hodgins, Biddulph, Gann, Hatheway, Lange and Lifton2006; Brock et al. Reference Brock, Froese and Roberts2010). The results, which are based on a limited number of samples, show that low-temperature combustion can avoid the contaminating effect of old OC in bulk sediment and thereby generate ages more consistent with the depositional age, although likely are still a maximum estimate of the actual depositional age considering that some amount of old OC is likely combusted even at low temperature.

Considerable research has been devoted to analyzing 14C generated from progressively heated sediment and soil in an oxygen-free environment (pyrolysis). These experiments have demonstrated the utility of ramped pyrolysis to tap various classes of molecules with different geochemical stabilities and ages within bulk sediment (e.g., Rosenheim et al. Reference Rosenheim, Santoro, Gunter and Domack2013; Rosenheim and Galy Reference Rosenheim and Galy2012). At lower temperature, bulk sediment typically generates CO2 with a younger 14C age than when pyrolyzed at higher temperature (e.g., Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Zhou, Wang, Lu and Du2013). Rosenheim et al. (Reference Rosenheim, Day, Domack, Schrum, Benthien and Hayes2008) showed that even their lowest-temperature fraction contains some older allochthonous carbon in the acid-insoluble fraction of Antarctic marine sediment and therefore yields maximum age constraints, albeit much closer to the actual depositional age than ages based on the conventionally analyzed total organic carbon pool. By analyzing a lower-temperature fraction of marine sediment, Subt et al. (Reference Subt, Fangman, Wellner and Rosenheim2016) derived ages from Antarctic marine sediment that mostly agreed with those from corresponding planktonic carbonate 14C, suggesting that the ramped pyrolysis 14C dating method is a reliable alternative. In a related study, Suzuki et al. (Reference Suzuki, Yamamoto, Rosenheim, Omori and Polyak2021) used the difference in 14C ages between high- and low-temperature fractions to approximate the depositional age of sediment from the Gulf of Alaska. These experiments, while time consuming and applied to relatively few samples, are promising for geochronology and afford insight into carbon-cycle dynamics in a variety of depositional settings (Gaglioti et al. Reference Gaglioti, Mann, Jones, Pohlman, Kunz and Wooller2014; Ghazi Reference Ghazi2022; Ginnane et al. Reference Ginnane, Turnbull, Naeher, Rosenheim, Venturelli, Phillips, Reeve, Parry-Thompson, Zondervan, Levy and Yoo2024; Hemingway et al. Reference Hemingway, Rothman, Grant, Rosengard, Eglinton, Derry and Galy2019; Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Thomas, Rosenheim, Miller, Sepúlveda, Firesinger, de Wet and Gaglioti2025; Sinon et al. Reference Sinon, Abbott, Shelef, Rosenheim, Firesinger, Griffore, Finkenbinder, Finney and Edwards2025; Vetter et al. Reference Vetter, Rosenheim, Fernandez and Törnqvist2017; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bianchi, Cui, Rosenheim, Ping, Hanna, Kanevskiy, Schreiner and Allison2017).

Here we present a simple procedure for determining the 14C age of the low-temperature component of bulk sediment. The method is developed for the increasingly widely deployed gas-ion source (aka, Gas Interface System, GIS) of the Mini Carbon Dating System (MICADAS Ionplus), which uses an elemental analyzer (EA) to generate CO2 that is injected into the accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) (Ruff et al. Reference Ruff, Fahrni, Gäggeler, Hajdas, Suter, Synal, Szidat and Wacker2010). While the method can be adapted for graphite source AMS instruments, the GIS of the MICADAS offers several advantages: (1) It omits the graphitization step. Although graphite enables higher precision AMS measurements than the GIS (by about a factor of four), the age of the low-temperature 14C fraction is still only an approximation of the age of deposition, so the additional precision is not necessary. By omitting the graphitization step and reducing the run time on the AMS, sample throughput is approximately 3–5 times faster. (2) Much smaller amounts of carbon are routinely measured using the GIS compared with graphite (by about a factor of 10), which can be important for organic-poor or sample-limited sediment. (3) Samples are acidified within the EA capsule thereby retaining the soluble component of OC, which we speculate is among the fractions that best represent the age of sediment deposition (see below).

The purpose of the method is to rapidly generate ages from bulk sediment that are reliably more accurate than those generated using the conventional procedure of dating the total organic carbon (TOC) component of bulk sediment. The method affords some of the same advantages as those that employ manually operated, high-precision combustion and pyrolysis equipment including insights into carbon-cycle dynamics. It has the added benefit of cost-effectively generating data from a much larger number of samples given the same analytical budget. Increasing the number of ages can improve the chronology of sedimentary sequences (Blaauw et al. Reference Blaauw and Christen2018) and therefore their scientific value, even if the precision of the ages is less than those from graphitized samples (Zander et al. Reference Zander, Szidat, Kaufman, Żarczyński, Poraj-Górska, Boltshauser-Kaltenrieder and Grosjean2020).

Methods and Materials

General approach

To develop the method, we first identified the temperature that optimized the tradeoff between being high enough to generate sufficient CO2 (> 50 µg C) to measure a sample’s 14C content while also low enough to avoid tapping the oldest of the bulk OC. Sediment samples were combusted under ambient air for 5.0 hr to determine the amount of OC liberated at temperatures ranging from 200° to 400°C. Because the response to heating is sample-dependent, we analyzed a variety of sediments of different ages from cores from five Arctic lakes and dredged from a river. The results were used to identify the temperature at which an average of about half of the total OC was released while avoiding the more recalcitrant high-temperature fraction.

For this procedure, the 14C content of OC released at low temperature is not measured directly, but is calculated by difference. To determine the low-temperature 14C age of sediment, we split each sample into two aliquots: one was heated at low temperature to remove its low-temperature OC and a second was not heated, thereby retaining its total OC content (Figure 1). Both aliquots were analyzed using the EA-GIS on the MICADAS, which measures both the carbon abundance (% C) and the 14C content. The 14C age of the low-temperature component was then calculated by difference using a simple two-component mixing model:

Figure 1. Approach used in this study. (a) Generalized characteristics of OC that combusts at low versus high temperatures. (b) The low-temperature fraction of a sample can be measured as the difference between the total carbon minus the carbon remaining after the low-temperature heating. (c) Simplified flow chart of the experimental procedure.

Where C = wt% organic carbon, Fm = fraction modern 14C, and subscripts T, H, L indicate the total OC, high-temperature, and low-temperature fractions, respectively. In this equation, % C for the high-temperature OC fraction is calculated using the sediment weight of the dried subsample prior to heating and acidification.

The accuracy of the low-temperature ages was evaluated by comparison with the 14C age of macrofossils from the same stratigraphic levels. The reproducibility of the method was quantified by analyzing separate aliquots of lake sediment and a standard reference material (see below) across multiple batches. For context, the reproducibility of macrofossil 14C ages was also quantified. The uncertainty associated with the low-temperature ages was estimated using a Monte Carlo procedure that integrates the various sources of errors.

Materials

Existing sediment cores from five Arctic lakes located in a variety of geomorphic settings (Table 1) were sampled to capture natural variability in carbon content among lakes and through time, ranging back to around 15,000 years. Because sediment that accumulates in high-latitude lakes often contains sparse macrofossils, an alternative dating method could have wide application in these settings. However, ages on macrofossils are available from these cores as part of recently published and ongoing paleoclimate research (references in Table 1). Moreover, sediment from one of the lakes, Lake CF8, has been analyzed using ramped pyrolysis procedures (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Thomas, Rosenheim, Miller, Sepúlveda, Firesinger, de Wet and Gaglioti2025), providing a point of comparison with the combustion-based results reported here.

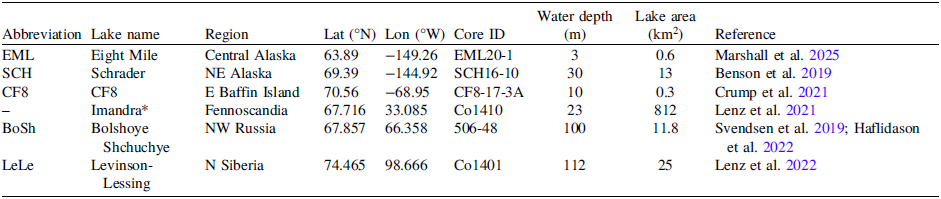

Table 1. Lakes sampled for this study (from west to east), with key references

* Samples from Lake Imandra are used only for the paired macrofossil reproducability test

Buffalo River Sediment (BRS, Standard Reference Material 2704; NIST 8704) was analyzed along with lake sediment to quantify the reproducibility of our procedure within and between sample batches. While generally used as a standard for elemental abundance, we chose BRS because we are not aware of any other publicly distributed reference material with properties similar to our lake sediment and with well-characterized 14C content. BRS comprises freeze dried, irradiated, and homogenized sediment dredged from the Buffalo River, New York and sieved between 38 and 150 µm (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Diamondstone and Gills1989). The homogeneity of BRS is certified based on aliquots of 250 mg, whereas our measurements are based on subsamples that are an order of magnitude smaller, which might explain some within-batch variability in our dataset. The certified total C abundance of BRS is 3.35%. Following acidification using our procedure, which removes carbonate but retains soluble OC (see below), the C abundance of BRS is reduced to 2.4 ± 0.1% (mean ± 1 SD; n = 27). The OC content of BRS is similar to that of most of the lake sediment analyzed in this study, which has a median % OC of 3.2 ± 3.0% (± 1SD; n = 64). However, the inorganic carbon content of BRS, while only around 1%, is higher than in our lake sediment as evidenced by the lack of effervescence in any of the lake sediment samples tested with HCl.

For procedural blanks, we tested the use of sediment excavated from the Ziegler Reservoir fossil site (Snowmastodon site) in Colorado. The sub-aqueously deposited sediment was collected from Unit 15, which is estimated to have been deposited 70-50 ka, based on luminescence dating and supported by other techniques (Mahan et al. Reference Mahan, Gray, Pigati, Wilson, Lifton, Paces and Blaauw2014). The 14C content measured in Ziegler sediment is significantly higher than for phthalic anhydride, which is used as an analytical blank. However, the difference in unknown sample ages calculated using the Ziegler procedural blank compared with the synthetic analytical blank is negligible for the relatively young (mainly Holocene) sediment analyzed in this study. Arguably, Ziegler sediment is an appropriate procedural blank because its matrix is similar to our lake sediment samples; however, post-depositional processes that affect the 14C content of sediment can be site-specific. We are continuing to explore this and other sediment for use as a procedural blank.

Sediment preparation

Approximately 1–3 g of dried sediment was passed through a 150 µm sieve to exclude the possible disproportional influence of macrofossils, if present, on the bulk-sediment analysis. Stoner et al. (Reference Stoner, Schrumpf, Hoyt, Sierra, Doetterl, Galy and Trumbore2023) also recommend removal of particulate organic matter prior to analysis for best characterization of the thermal distribution of 14C in soil OC. The sediment was not ground because lake bottom mud is typically finer than 150 µm and because we aimed to preserve and isolate any sizable macrofossils to measure their 14C for comparison with the bulk sediment 14C. Optimal sample sizes for the EA-GIS contain between 100 and 200 µg C, so having a rough sense of the OC content of the sediment is useful (1 mg of sediment with 1% OC yields 10 µgC). Depending on the sediment OC content, we loaded between 10 and 80 mg of the bulk sediment into pre-baked (3 hr @ 800°C) silver EA capsules. This sediment weight was recorded to the nearest microgram and used when calculating the weight% C from the EA data. Subsequent heating and acidification steps (see below) affect the mass of material in the EA capsules, and therefore affect the % C measured by EA. Applying the initial weight to the calculations to determine % C using an EA simplifies the procedure; it yields the correct % C value needed for the mixing model as formulated in Eq. 1. Sediment should not be acidified prior to heating because the resulting products (CaCl2 and possibly others) affect the thermochemical stability of the organic molecules.

Capsules with sediment were placed in a preheated 250°C furnace for 5.0 hr. Previous studies of sediment mass loss on ignition show that most of the mass loss occurs during the first several hours followed by a transient decrease in mass that levels off exponentially over days, even at relatively high temperature (550°C) (Heiri et al. Reference Heiri, Lotter and Lemcke2001). We chose 5.0 hr because it is a practical length of time procedurally for achieving near steady state for a given temperature.

The heated (“high temperature”) and unheated (TOC) aliquots were then acidified to remove inorganic carbon by adding drops of ultrapure (sequencing grade) 6M HCl to each capsule until the sediment was visibly saturated, then dried in a 50°C convection oven for 24–48 hr. The silver capsules were closed and rolled again into a tin capsule (Mollenhauer et al. Reference Mollenhauer, Grotheer, Gentz, Bonk and Hefter2021). This prevented sediment loss because the silver capsules can degrade in acid, and it assured complete OC combustion in the EA because tin undergoes a flash exothermic reaction. The capsules were stored in the freezer or desiccator while awaiting analysis.

Macrofossil preparation

Sediment from 1- or 2-cm-thick samples was deflocculated using sodium hexametaphosphate then wet-sieved at 150 μm. Plant fragments and chitin were picked, described and cleaned using an acid-base-acid pretreatment (Zander et al. Reference Zander, Szidat, Kaufman, Żarczyński, Poraj-Górska, Boltshauser-Kaltenrieder and Grosjean2020) or only acid in the case of very small and delicate materials (e.g., Rethemeyer et al. Reference Rethemeyer, Fülöp, Höfle, Wacker, Heinze, Hajdas, Patt, König, Stapper and Dewald2013). Fragments were loaded into tin capsules, dried, weighed and rolled, then stored in the freezer while awaiting analysis.

Analytical procedure

Our novel procedure takes advantage of the gas-ion source for the MICADAS, which directly receives CO2 generated by an EA, cleans it, and injects it into the MICADAS (Ruff et al. Reference Ruff, Fahrni, Gäggeler, Hajdas, Suter, Synal, Szidat and Wacker2010). We used the EA (Elementar Vario Isotope Select) to measure the C abundance of each subsample prior to measuring its 14C content on the MICADAS. This required analyzing EA calibration standards in each batch to correct for any machine drift but then venting the gas so that it was not analyzed on the MICADAS. To optimize the EA for measuring % C in small samples, we use approximately the same µg C for the standards as for the unknowns, roll them in the same capsule types, and analyze standards with a range of masses (about 20–500 µg C) to construct a calibration curve. All tin capsules were combusted in the EA above their auto-ignition temperature. We report both % C and % N values but investigating the nitrogen dataset is beyond the scope of this study.

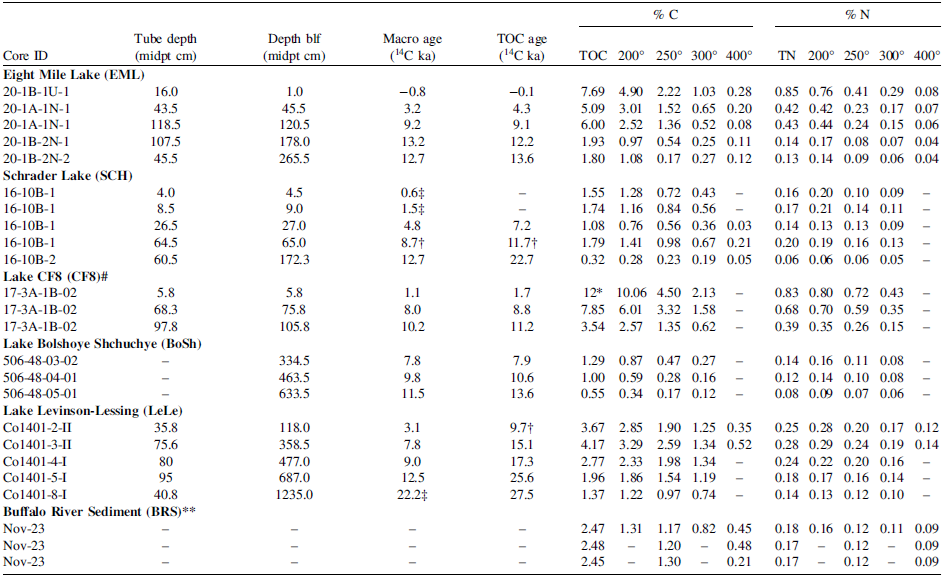

For samples analyzed prior to December 2023, C abundances were measured using a stand-alone EA (Costech ECS4020) and a separate aliquot of bulk sediment than used for measuring 14C. This includes all subsamples that were heated at multiple temperatures to identify the optimal combustion temperature for this study (Table 2). A larger mass of sediment, typically 10–30 mg depending on the OC content, was used for these measurements.

Table 2. Carbon loss with increasing combustion temperature

* Off scale; extrapolated estimate

** Remaining % C values in Figure 2 all based on the average of four unheated (TOC) aliquots

†Average of two ages

‡ Age based on modeled age in cal yr BP

# Tube depths listed for CF8 are for the recently sampled archive half. Depth blf are equivlant depths used to construct the age model. Tube contains 4 cm of foam.

The operating conditions and performance of the MICADAS (IonPlus) in the Arizona Climate and Ecosystem (ACE) Isotope Laboratory at Northern Arizona University (Ebert et al. Reference Ebert, Schuur, Kaufman, Brown, Propster, Kelley, Bright, Carbone, McKay and Koch2022) is typical of other MICADAS labs (e.g., Mollenhauer et al. Reference Mollenhauer, Grotheer, Gentz, Bonk and Hefter2021; Turney et al. Reference Turney, Becerra-Valdivia, Sookdeo, Thomas, Palmer, Haines, Cadd, Wacker, Baker, Andersen and Jacobsen2021). Data from the MICADAS were processed using BATS software (version 4.0; Wacker et al. Reference Wacker, Bonani, Friedrich, Hajdas, Kromer, Nemec, Ruff, Suter, Synal and Vockenhuber2010). Radiocarbon measurements are reported following the conventions of Stuiver and Polach (Reference Stuiver and Polach1977), including corrections for isotopic fractionation, with δ13C values measured on the AMS. All results are reported as fraction modern (Fm) and corresponding 14C age in years BP (1950 CE). All ages were also calibrated to calendar years based on IntCal20 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey and Butzin2020).

Results and discussion

Optimizing the heating temperature

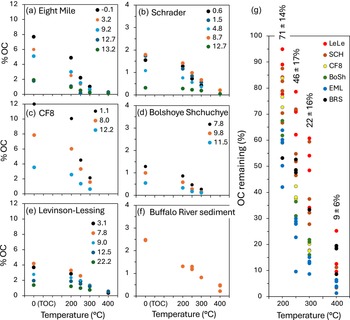

The OC content of bulk (< 150 µm), acidified sediment was measured using a stand-alone EA following heating for 5.0 hr at temperatures ranging between 200 and 400°C. Three to five samples (21 total) with varying OC contents and deposition ages were analyzed from each of the five lakes, plus BRS (Table 2). Rather than step-heating the same sediment at progressively higher temperature, separate aliquots were used for each temperature so each experienced the same heating duration. The proportion of OC remaining following combustion at each temperature was calculated as a percentage of the OC abundance in the unheated aliquot (TOC). OC abundance decreased with increasing temperature for all sediment samples, with only one exception (Figure 2; Table 2). The relative proportion of OC remaining after each heating step differed by lake, with high portions remaining in sediment from Lake Levinson-Lessing and relatively little remaining in sediment from Eight Mile Lake. Overall, among all samples, 29 ± 14% (n = 22) of OC was combusted at 200°C compared to 91 ± 6% (n = 11) at 400°C. The proportion of OC combusted at each temperature is strongly related to the offset between the TOC age and its depositional age, as determined by macrofossils (see below).

Figure 2. Carbon loss with increasing combustion temperature. (a–e) Samples from five lakes and (f) Buffalo River sediment heated at different temperatures for 5.0 hr, plus unheated counterparts (0°C = TOC). Symbol colors represent the relative age of each sample (values are 14C ka BP) determined by macrofossils from the same sample as listed in the legend of each panel. (g) Same data as shown in (a–f) but values are plotted relative to each sample’s initial % TOC. From hot to cold, symbol colors indicate the magnitude of age offset between the TOC and macrofossil age characteristic for each lake, with Lake Levinson-Lessing being the highest and Eight Mile Lake the lowest. Values shown vertically are mean ± 1 SD for each temperature. Data are in Table 2.

Based on these results, we selected 250°C as the combustion temperature for subsequent 14C measurements. On average across the 21 sediment samples, 54 ± 17% (n = 25) of the OC was combusted at 250°C. Although the thermostability of OC is sample-dependent, this temperature likely approximates the maximum temperature beyond which the most recalcitrant and oldest organic molecules are decomposed. While a lower temperature cutoff would further reduce the chance of tapping older molecules, it also risks combusting too little OC so that what remains is insufficiently distinct from the TOC to generate a distinct end-member for the mixing-model calculation.

The 250°C cutoff used to define the low-temperature component in our procedure is lower than that used in other studies. Initially, we focused on 400°C, which was used for the low-temperature step in published two-step 14C combustion procedures (Buró et al. Reference Buró, Négyesi, Varga, Sipos, Filyó, Jull and Molnár2022; Cheng and Fu Reference Cheng and Fu2020; McGeehin et al. Reference McGeehin, Burr, Jull, Reines, Gosse, Davis, Muhs and Southon2001; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Burr, Chen, Lbrockin and Wu2013). However, we found that nearly all carbon is combusted from our samples at this temperature and that the 14C content of the evolved CO2 is nearly the same as for the TOC pool (data not shown). We attribute the higher proportion of carbon released at low temperature in our heating experiments to a longer duration of heating, which was 5.0 hr. Most published stepped-combustion studies do not report the duration of the combustion used. Chen and Fu (Reference Cheng and Fu2020) found that 87 ± 3% (n = 8) of the carbon in the humin fraction of their loess-paleosol sediment was combusted at 400°C for an unspecified duration, which overlaps with our results at that temperature (Table 2). In contrast, Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Zhou, Wang, Cheng, Hou, Du, Xiong, Yang, Wang and Fu2020) found that only about 50% of OC in soil (n = 3) was combusted at 400°C held for 0.5 hr. Similarly, Keaveney et al. (Reference Keaveney, Radbourne, McGowan, Ryves and Reimer2020) reported that 51 ± 17% (n = 11) of the TOC in young lake sediment had decomposed overnight at 400°C. Rather than measured directly, however, they estimated the fraction combusted using a mass-balance equation, in which they assumed that two combustion steps (overnight at 400°C and then re-combusted overnight at 850°C) generated the same amount of CO2 as for a single step at 850°C.

Experiments using ramped pyrolysis also show that temperatures closer to 400°C are needed to liberate half of the OC in soils (e.g., Sanderman and Grandy Reference Sanderman and Grandy2020; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Bianchi, Cui, Rosenheim, Ping, Hanna, Kanevskiy, Schreiner and Allison2017) and sediments (e.g., Rosenheim et al. Reference Rosenheim, Santoro, Gunter and Domack2013). This is consistent with the results from Lake CF8 where we measured 59 ± 6% (n = 7) of OC combusted at 250°C compared with 3.2% decomposed at 250°C and 59% decomposed at an average temperature of 412°C when the same samples were measured using ramped pyrolysis (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Thomas, Rosenheim, Miller, Sepúlveda, Firesinger, de Wet and Gaglioti2025). Ramped pyrolysis uses steadily increasing temperatures, typically 5°C per minute (Rosenheim et al. Reference Rosenheim, Day, Domack, Schrum, Benthien and Hayes2008), whereas some organic molecules require sustained exposure to a given temperature before decomposition (e.g., Heiri et al. Reference Heiri, Lotter and Lemcke2001). The extent to which removing the acid-soluble fraction, as was done in previous studies, contributed to the difference between the outcomes of the two procedures is not presently known.

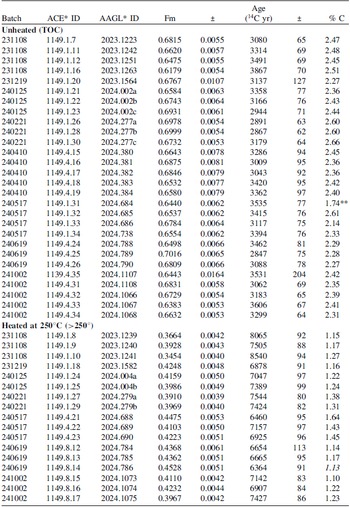

Reproducibility—Buffalo River sediment

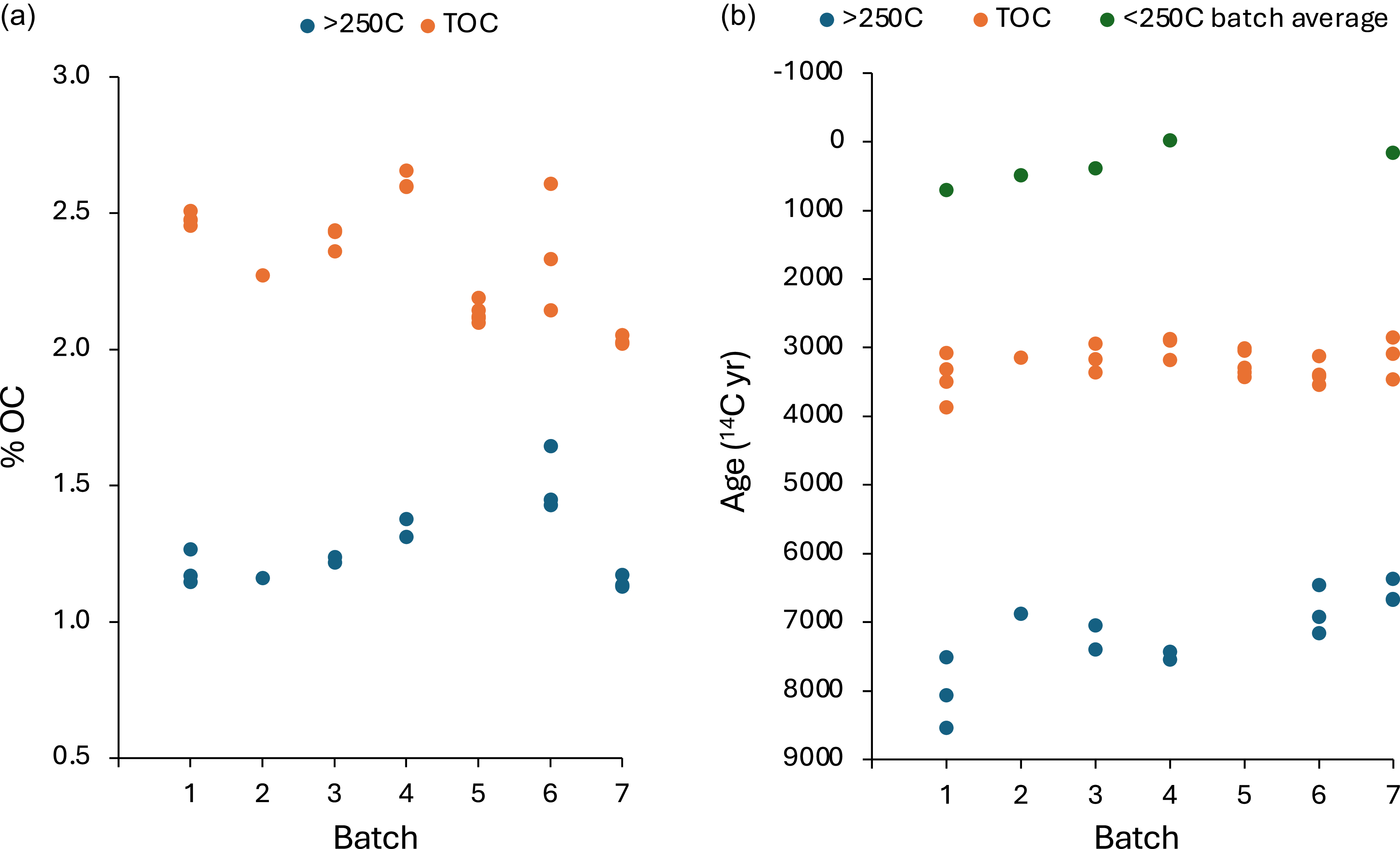

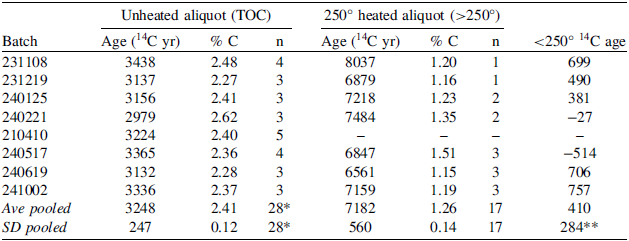

The OC content of multiple aliquots of a widely distributed standard material, BRS, was measured using the EA connected to the GIS on the MICADAS. All aliquots were acidified to remove inorganic carbon, which comprises roughly 1% by weight of BRS total carbon, while retaining the soluble OC (see below). A total of eight batches, each comprising 1 to 5 replicates of TOC and 250°C-heated BRS, were analyzed between November 2023 and October 2024 (Table 3a; Figure 3). Overall, the % OC averages 2.41 ± 0.12% (n = 27) for TOC and 1.26 ± 0.14% (n = 17) for the 250°C-heated sediment (i.e., the >250°C fraction). These values are on par with those of our lake sediment samples, which have median values of 3.2 and 1.5% OC (n = 64), respectively (Supplementary Table S1). The variability across the entire dataset, which was generated over the course of one year, is reduced when values from replicates within each batch are averaged, which likely reflects between-batch biases. The mean within-batch SD across batches with two or more replicates is ± 0.06% OC for both the TOC (n = 7) and >250°C (n = 6) fractions.

Table 3a. 14C and % C for unheated (TOC) and heated (>250°C) fractions of Buffalo River sediment

* ACE = Arizona Climate and Ecosystem Isotope Laboratory; AAGL = Amino Acid Geochronology Laboratory

** Outlier; excluded

Figure 3. Repeat analyses of Buffalo River sediment across seven batches analyzed with the EA-GIS-MICADAS over one year. (a) % C measured on unheated (TOC) and heated (250°C) aliquots. (b) 14C measured in the same aliquots as in (a). Low-temperature ages (<250°C) are calculated using per-batch averages applied to a two-component mixing model (Eq. 1). Data are in Table 3.

The EA that measures the bulk sediment % OC feeds the evolved CO2 to the GIS-MICADAS to measure its 14C content. The resulting 14C age of acidified BRS across multiple batches averages 3248 ± 247 14C yr BP (n = 28) for the TOC (Table 3b). This compares with a 14C age of untreated BRS (total carbon), which averages 5260 ± 179 14C yr BP (n = 13) (data not shown). We are not aware of a published radiocarbon value for NIST8704, either as bulk sediment or as the OC fraction. BRS was dredged from Buffalo River to a depth of ≤ 1 m below the river bottom (Epstein et al. Reference Epstein, Diamondstone and Gills1989). The 3.5 cal ka age (2.9–4.1 cal ka 95% calibrated age range) of the TOC is untenably old as a depositional age for the channel-bottom sediment. A more realistic depositional age for BRS can be derived based on the 14C content of its low-temperature OC component. Using Eq. (1) along with the average values for Fm and % OC measured on the TOC and heated aliquots (2.41 and 1.26%, respectively) yields an age of 406 ± 279 14C yr BP (0.0–0.9 cal ka 95% range) for the low-temperature (<250°C) component of acidified BRS (see below for explanation of the estimated uncertainty). This depositional age of centuries is more reasonable than millennia for river-bottom sediment, illustrating the utility of the low-temperature 14C fraction to approximate depositional ages.

Table 3b. Mean values by batch used to calculate low-temperature (<250°C) age of Buffalo River sediment

* n = 27 for % C

** Based on procedure described in text

Reproducibility—lake sediment TOC radiocarbon

To evaluate the reproducibility of the EA-GIS-MICADAS applied to the TOC fraction of lake sediment, 20 pairs of subsamples were analyzed in different batches (Supplementary Table S1). Twelve pairs were from Eight Mile Lake and the other eight pairs from three other lakes. The average analytical precision of Fm measured in the bulk sediment is ± 0.004 Fm (n = 40). The average absolute difference in Fm between duplicate subsamples is 0.014 ± 0.010, indicating that differences cannot be attributed to analytical precision alone. The 14C ages of the duplicate subsamples overlap within their ± 1SD values for 35% of the pairs (7 out of 20). The average absolute age difference between duplicate subsamples is 344 ± 321 14C yr, which is reduced to 283 ± 173 14C yr when one outlier from Lake Levinson-Lessing is excluded. The average pairwise difference is similar to the scatter measured in subsamples of BRS. This likely reflects organic-matter content that is somewhat heterogeneous at the scale of our bulk-sediment subsamples (10–80 mg).

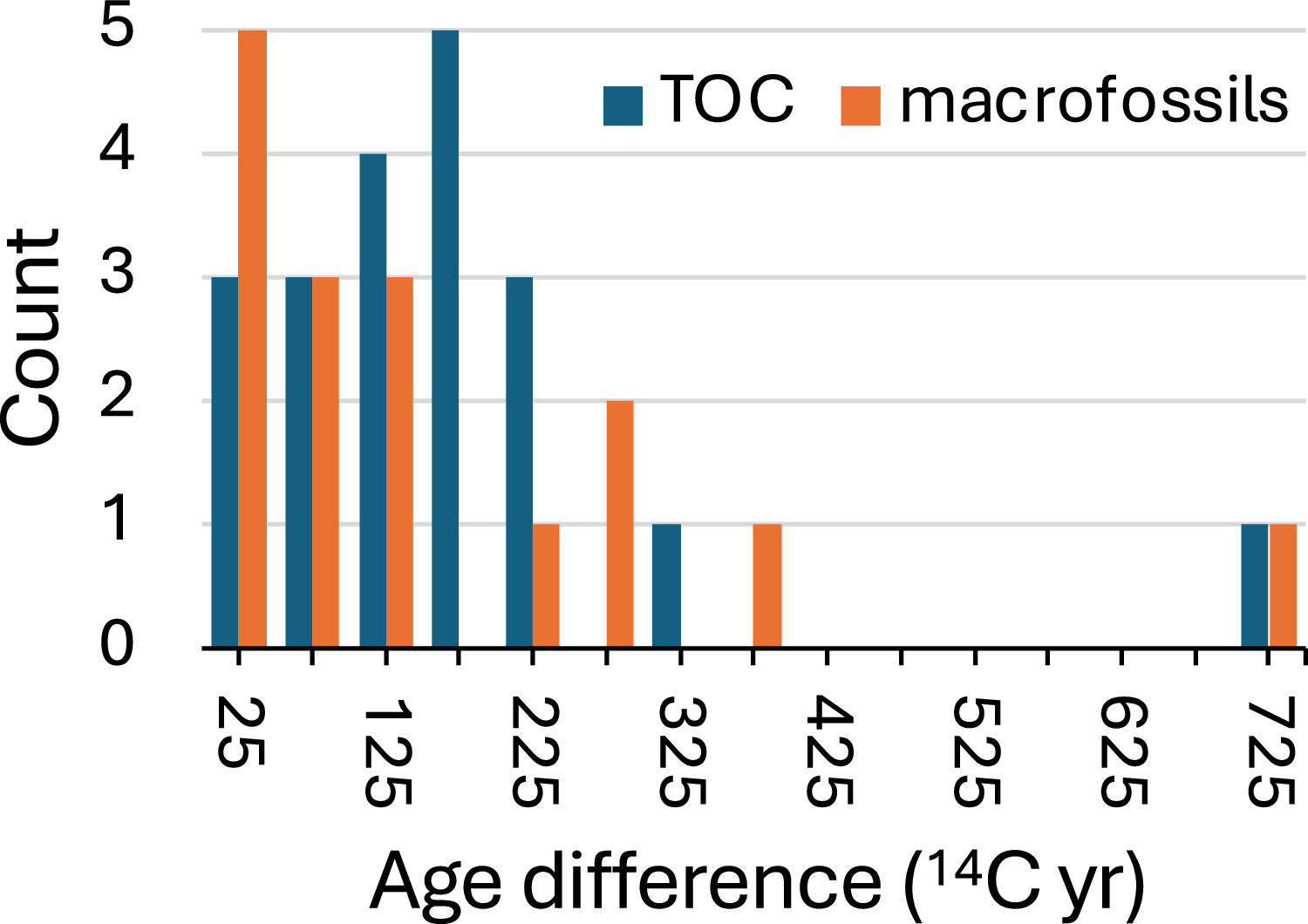

Reproducibility—macrofossil radiocarbon

To put the analytical precision and reproducibility of bulk-sediment 14C measurements into context, we compared them to those of 14C measured in 16 pairs of macrofossil subsamples from four of our study lakes, including Lake Imandra, which was not included in our low-temperature 14C study (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S1). The average analytical precision of Fm measured in these macrofossils using the EA-GIS-MICADAS is ± 0.005 Fm (n = 32), which is slightly worse than for Fm measured in bulk sediment (± 0.004; n = 40). We attribute the lower analytical precision to the smaller carbon masses that were analyzed for some macrofossils. The average absolute difference in Fm between duplicate macrofossil subsamples is 0.012 ± 0.014, which is essentially the same as for the bulk-sediment pairs. The 14C ages of the duplicate macrofossil subsamples overlap within their ± 1SD values for 56% of the pairs (9 out of 16), which is more than for the bulk sediment and likely reflects their larger analytical uncertainty and possibly the fact that most pairs were analyzed in the same batch. The average absolute radiocarbon age difference between the duplicate subsamples is 321 ± 369 14C yr, which is reduced to 245 ± 216 14C yr when one outlier from Schrader Lake is excluded. As for the pairwise differences in bulk-sediment measurements, this likely reflects actual differences in the ages of macrofossil subsamples. In summary, the pairwise differences between ages of macrofossil subsamples from the same stratigraphic level are similar to those of bulk sediment (Figure 4), while the counting statistics are generally slightly better for the bulk sediment.

Figure 4. Difference between 14C ages from duplicate subsamples of TOC and macrofossils from four study lakes. The pairwise differences are similar between the two sample types, indicating that their reproducibility is similar in practice.

Deterministic error propagation

The uncertainty in the 14C age of the low-temperature component of OC depends on the magnitude of the errors associated with measuring the OC abundance and 14C content in the TOC and heated (>250°C) aliquots. Analytical errors were propagated using first-order Taylor series expansion. Partial derivatives of Fm L (equation 1) were calculated with respect to each input variable and combined in quadrature with their respective 1SD uncertainties. The total uncertainty in age was then obtained by propagating the uncertainty in Fm L through the logarithmic transformation for the age equation, −8033⋅ln(Fm L ). This approach assumes that errors are independent and normally distributed. A Supplementary file contains the formulas used to calculate the 14C age and associated uncertainty of the low temperature component of the OC.

For Fm, the analytical uncertainty is the 1SD precision measured by the MICADAS for each aliquot individually according to the same counting statistics used to report conventional 14C age errors. For % OC, we use relative errors (i.e., coefficient of variation, CV = SD/mean) of ± 3% and 4% for the TOC and heated aliquots, respectively (e.g., TOC of 2% is assigned an absolute uncertainty of ± 0.06%). These CVs are based on the mean within-batch SD measured on replicates of both the TOC and >250°C fractions of BRS (± 0.06%, see above). Using within-batch uncertainty is appropriate because any bias in measuring % C (e.g., calibration procedures) cancel out in the by-difference calculation of low-temperature age using aliquots measured in the same batch. Using relative errors is also appropriate because we found that organic-poor samples (OC < about 1%) return untenably high age uncertainties when applying the absolute error derived from sediment with higher % OC (BRS = 2.4 ± 0.06% OC). Samples with both low TOC and high retention of OC following combustion are especially susceptible. Conversely, age uncertainties for samples with high % OC are insensitive to the error assigned to the % OC value, despite higher values assigned based on CV.

On the basis of the propagated errors, the median uncertainty for low-temperature ages from the five lakes is 185 years with an interquartile range of 115 years (n = 64) (Supplementary Table S1). The uncertainties are generally larger than the analytical precision reported for the ages of the individual aliquots but are tolerable considering that the ages are approximations of the true depositional ages.

Error propagation was used to calculate the age uncertainty for the low-temperature fraction of BRS using the pooled dataset. For Fm, we used the average measured value of 0.668 for TOC (n = 28) and 0.410 (n = 16) for the 250°C-heated aliquots, both with a precision of ± 1%, which is typical for the EA-GIS-MICADAS. For % OC, we used the average measured values of 2.41% and 1.26% for the TOC and 250°C-heated aliquots, respectively. The resulting age uncertainty for the <250°C component of BRS is ± 279 years.

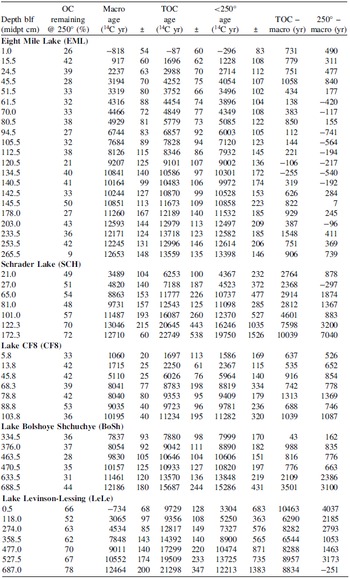

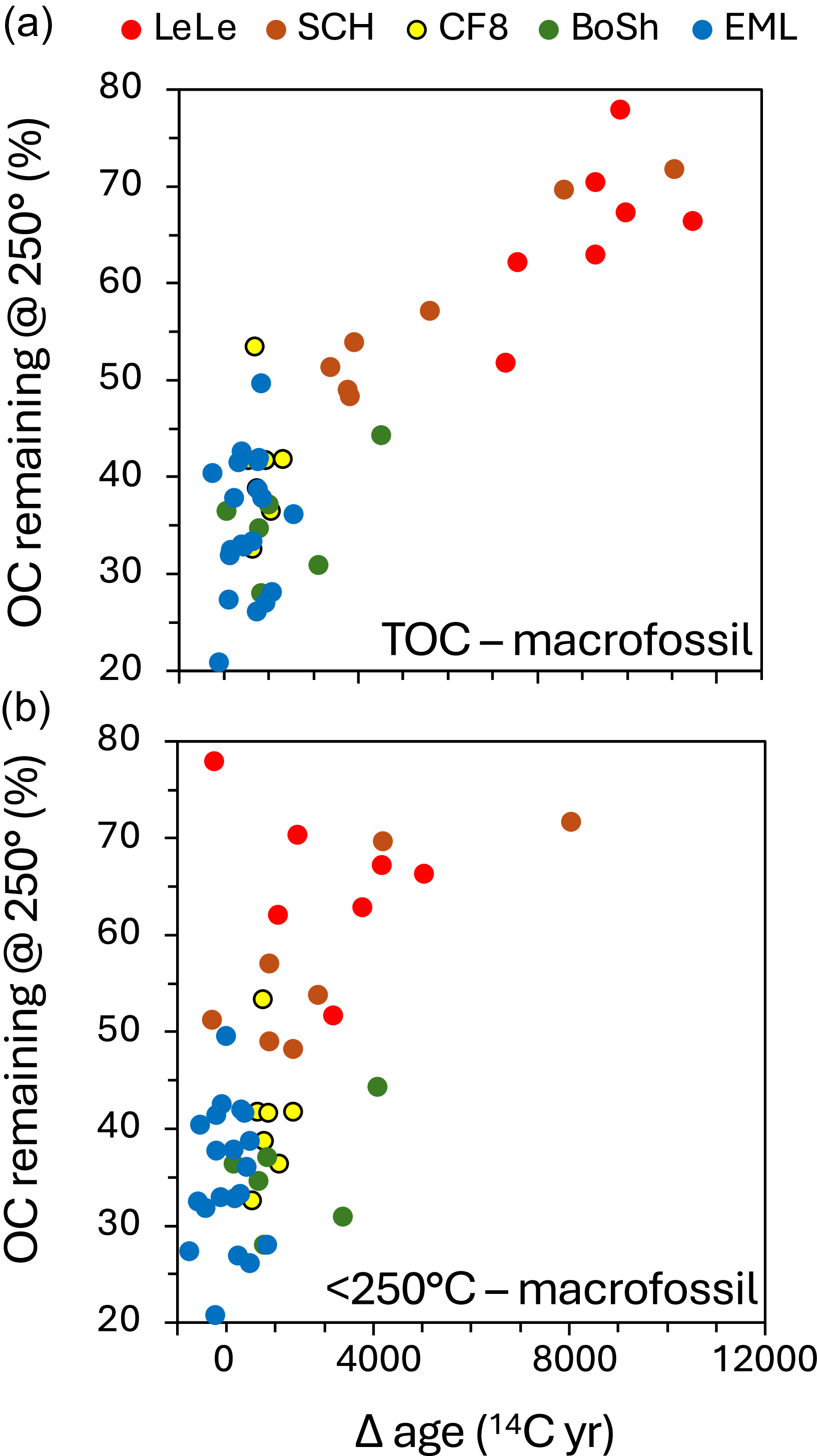

<250°C ages compared to macrofossil and TOC ages

To evaluate the extent of the improvement made by the low-temperature combustion procedure, we assumed that the macrofossil ages provide the best estimate of the depositional age of the enclosing sediment. We calculated the difference between ages of each macrofossil and its <250°C and TOC counterparts and compared the offsets from the five lakes (Table 4; Figure 5). For the 48 samples where all three types of ages are available, the macrofossil ages are closer to the <250°C ages than they are to the TOC ages (pairwise differences average 934 ± 1412 14C years compared with 2425 ± 3090 14C years, respectively). For three of the five lakes (Levinson-Lessing, Schrader, and Eight Mile Lakes), the offset with the macrofossil ages was reduced by 70% for the <250°C fraction compared with the TOC offset, from an average of 2922 years down to 883 years (n = 31). For the other two lakes (Bolshoye Shchuchye and CF8), there was no substantial improvement, with the age offsets averaging 1085 versus 1072 years, respectively (n = 13) (Figure 5c). An investigation into what causes the various degree of age offsets from lake to lake is beyond the scope of this study but is taken up by Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Kaufman, McKay, Thomas and Melles2024, Reference Marshall, Kaufman, Bigelow, Bolton, Finney, Jensen, McKay and Muñoz2025) and for Lake CF8 by Lindberg et al. (Reference Lindberg, Thomas, Rosenheim, Miller, Sepúlveda, Firesinger, de Wet and Gaglioti2025).

Table 4. Summary of 14C ages on samples analyzed for all three organic-matter types: macrofossils, TOC, and low-temperature fraction

Figure 5. Comparison between 14C ages for three types of organic matter from the same sediment samples from five study lakes. (a) Macrofossils versus bulk sediment TOC ages. (b) Macrofossil versus bulk sediment low-temperature (<250°C). Lines show 1:1 relationship. (c) Average difference between macrofossil and TOC ages and between macrofossil and <250°C ages for the five study lakes. Data are in Table 4.

As expected, the proportion of OC remaining after heating—the recalcitrant OC—is indicative of the extent of offset between the macrofossil and bulk-sediment ages (Table 4; Figure 6). On average for Levinson-Lessing and Schrader Lakes, 61 ± 10% (n = 14) of OC remained after heating at 250°C compared to 36 ± 8% (n = 34) for samples from the other three lakes. The corresponding age difference between macrofossil and TOC ages for Levinson-Lessing and Schrader Lakes are also higher, averaging 6482 ± 2888 years compared to 754 ± 674 years for the other three lakes. The age differences are reduced for the low-temperature fraction, averaging 2100 ± 1908 years for Levinson-Lessing and Schrader Lakes compared to 452 ± 770 years for the other three lakes. Samples that retained a high proportion of OC after heating are much more likely to have large age offsets. Namely, of the 13 samples from our dataset with > 50% OC remaining, 11 (69%) have offsets (low-temperature minus macrofossil age) that exceed 1000 years, whereas, of the 35 samples with ≤ 50% OC remaining, only 5 (14%) have offsets that exceed 1000 years. Therefore, sediment with a high proportion of recalcitrant OC has the greatest reduction in age offsets when dating the low-temperature component, whereas sediment with a low proportion of recalcitrant OC is likely to yield low-temperature ages that more closely match macrofossil ages.

Figure 6. Relation between age offsets (relative to macrofossils) and proportion of OC remaining (i.e., recalcitrant OC) for (a) TOC and (b) <250°C ages. Data are in Table 4.

Of note is the small difference between the macrofossil ages and the low-temperature counterparts from Eight Mile Lake. This difference might be explained, at least in part, by our acidification procedure, which retains the dissolved OC component of the bulk sediment. The in-capsule procedure is used to measure bulk sediment 14C in at least one other radiocarbon laboratory (Mollenhauer et al. Reference Mollenhauer, Grotheer, Gentz, Bonk and Hefter2021), and it yields more consistent results than other procedures when measuring % C in various sediment types (Brodie et al. Reference Brodie, Leng, Casford, Kendrick, Lloyd, Yongqiang and Bird2011). In contrast, some laboratories use acid, or a combination of acid and base, plus water rinses to remove carbonate and soluble OC from bulk sediment. While this pretreatment eliminates inorganic carbon and diminishes OC derived from pore fluids that may migrate through sediment after deposition, it also removes soluble OC that accumulates contemporaneously with the sediment. Bao et al. (Reference Bao, McNichol, McIntyre, Xu and Eglinton2018) reported that acid-washed Holocene marine bulk sediments yielded 14C ages that are hundreds of years older than acid-fumigated counterparts. Although which of the procedures is more accurate was not determined in their study, we contend that retaining the dissolved OC fraction is advantageous for determining the depositional age of bulk sediment. As recently summarized by Sinon et al. (Reference Sinon, Abbott, Shelef, Rosenheim, Firesinger, Griffore, Finkenbinder, Finney and Edwards2025 and references therein), the age of dissolved OC in modern lake and river water is much closer to modern than that of particulate OC, which is typically defined as combustible OC retained on a > 0.45 μm filter. Sinon et al. (Reference Sinon, Abbott, Shelef, Rosenheim, Firesinger, Griffore, Finkenbinder, Finney and Edwards2025) also suggested that dissolved OC comprises a large portion of the TOC in sediment from an Alaskan lake, making its retention potentially critical for determining the depositional age of bulk sediment. Dissolved OC is abundant in the water from Eight Mile Lake presently, and its prominence in the sediment is suggested by the high proportion of OC combusted at low temperature (Table 2; Figure 2).

On the other hand, our results from Lake CF8 are very similar to previously reported data from ramped pyrolysis experiments on sediment from the same core that were pretreated with acid wash. Our data, like those of Lindberg et al. (Reference Lindberg, Thomas, Rosenheim, Miller, Sepúlveda, Firesinger, de Wet and Gaglioti2025), show little difference between the 14C ages of low- and high-temperature fractions. The offset between macrofossil and TOC ages averages 838 years for our dataset (n = 7) compared with 720 years for Lindberg et al.’s (n = 7; where the TOC ages were reconstituted from the five CO2 splits generated during ramped pyrolysis). This comparison indicates that the type of acidification procedure might make little difference in some settings while affirming that combustion and pyrolysis can yield similar information.

In addition to having the lowest average age offset relative to macrofossils, nearly all of the samples with low-temperature ages younger than their macrofossil counterparts are from Eight Mile Lake (Supplementary Table S1). Of the 48 samples with both types of ages, 11 have low-temperature ages that are younger than their corresponding macrofossils. However, the age differences are relatively small, averaging 330 ± 208 yr, and 7 of the 11 sample pairs have 14C ages that overlap within their respective ± 1SD uncertainties. In any case, our data show that low-temperature (<250°C) ages can generally be considered maximum limiting ages.

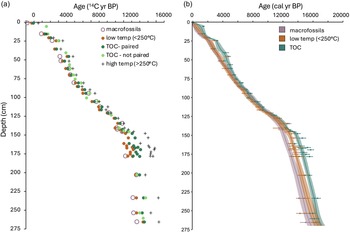

Age model comparisons: Macrofossils, TOC and <250°C from Eight Mile Lake

The sedimentary sequence from Eight Mile Lake was analyzed using 37 samples to define temporal trends in bulk-sediment 14C extending back to around 15 ka (Figure 7). Age versus depth was modelled using the R packages rBacon and geoChronR (Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011; McKay et al. Reference McKay, Emile-Geay and Khider2021) to yield continuous downcore ages for all three types of ages (TOC, <250°, and macrofossils) (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Kaufman, McKay, Thomas and Melles2024, Reference Marshall, Kaufman, Bigelow, Bolton, Finney, Jensen, McKay and Muñoz2025). The age differences were then evaluated following calibration to calendar years, which incorporates additional realistic uncertainties in 14C-derived chronologies. The results show that the difference between the median age model based on the macrofossils, considered the target age, and the TOC-based age model is 731 ± 576 cal years, as evaluated every century (n = 158). In comparison, the difference between the macrofossil age model and the <250°C age model is 156± 423 cal years. Similar to the by-sample comparisons, these results show that the low-temperature component of OC yields an age closer to the true depositional age compared with TOC. They also show that age offsets evolve through the depositional sequence. Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Kaufman, McKay, Thomas and Melles2024, Reference Marshall, Kaufman, Bigelow, Bolton, Finney, Jensen, McKay and Muñoz2025) discuss possible drivers of this evolution, including its relation to climate.

Figure 7. Age versus depth for three types of organic matter from the same sediment samples from Eight Mile Lake, our most intensively sampled study lake. (a) Data plotted as uncalibrated 14C ages. Some TOC samples (light-green circles) do not have macrofossil counterparts or are replicates of another TOC age from the same sample. (b) Continuous age versus depth relation with 95% confidence bands modeled using the R packages rBacon and geoChronR (Blaauw and Christen Reference Blaauw and Christen2011; McKay et al. Reference McKay, Emile-Geay and Khider2021). Error bars are 95% confidence intervals for calibrated ages.

Strengths of the method

We contend that our simple low-temperature combustion procedure is beneficial for 14C dating of bulk sediments. It provides an overall improvement in estimating the age of deposition compared to conventional bulk-sediment dating methods. The proportion of OC remaining after heating bulk sediment at a prescribed temperature is a useful indicator of the likely accuracy of the low-temperature age, which leads to the potential for further refinement of this approach. The simple procedure is practical for routine purposes and does not require specialized equipment for pre-processing sediment. This allows pre-treatment to be conducted in the collectors’ laboratory prior to submitting samples to an AMS lab. While the procedure requires the preparation and analysis of two aliquots per sample, it bypasses the need for graphitization, streamlining the workflow. While this study employed the EA-GIS interface of the MICADAS, the procedure does not necessitate this equipment. It can be adapted to graphite-based AMS instrumentation.

The method complements macrofossil-based radiocarbon ages, providing additional insights into the depositional history of sediments. For example, it can help confirm or discount downcore age reversals or depositional hiatuses seen in ages from macrofossils. Moreover, carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) data derived from bulk sediment, which we report (Tables 2 and S1) but do not analyze in this method-development paper, might be useful for assessing the extent to which bulk-sediment ages from lakes are biased toward old terrestrial carbon sources, an approach that has been successfully applied in previous studies (e.g., Bertrand et al. Reference Bertrand, Araneda, Vargas, Jana, Fagel and Urrutia2012).

Measuring the percentage of combusted carbon and associated 14C ages of low- and high-temperature fractions can be useful for subdividing bulk OC into end members for mixing models to track changes in the amount and type of organic matter that accumulates in lakes through time (e.g., Sinon et al. Reference Sinon, Abbott, Shelef, Rosenheim, Firesinger, Griffore, Finkenbinder, Finney and Edwards2025). The proportion of labile OC (combustible at low temperature) also has implications regarding its turnover times (e.g., Vetter et al. Reference Vetter, Rosenheim, Fernandez and Törnqvist2017), bioavailability (e.g., Baffi et al. Reference Baffi, Dell’Abate, Nassisi, Silva, Benedetti, Genevini and Adani2007) and susceptibility to decomposition (e.g., Gaglioti et al. Reference Gaglioti, Mann, Jones, Pohlman, Kunz and Wooller2014). These data can enhance our understanding of carbon cycling processes within lakes and their catchments, and can thereby inform broader paleoclimate interpretations.

Limitations

While the low-temperature combustion procedure provides a valuable improvement over conventional bulk-sediment 14C dating, the method has several important limitations. A remaining challenge is the potential for hardwater effects in lakes where the incorporation of ancient carbon into aquatic organic matter produced in the water column can lead to apparent ages that are too old (e.g., Grimm et al. Reference Grimm, Maher and Nelson2009). The low-temperature fractionation procedure does not mitigate these hardwater effects. Furthermore, while macrofossils are generally considered to provide the most accurate radiocarbon ages relative to the timing of deposition, they are not without limitations. Because terrestrial macrofossils can experience pre-aging before deposition in lakes, using them as a benchmark to evaluate the accuracy of low-temperature fraction ages introduces potential biases. Finally, while low-temperature ages represent a better approximation of the depositional age compared to conventional bulk ages, and while they can generally be considered maximum limiting ages, they remain approximations. Incorporating such ages into age modelling routines for sedimentary sequences poses challenges. Future work should explore strategies to integrate low-temperature ages more effectively into sediment age modeling frameworks.

Further refinement and testing of the method are needed. This study focused on carbonate-free, organic-poor sediment from Arctic lakes with ages younger than 15 ka. The effectiveness of the method applied to other depositional settings where sedimentation dynamics, vegetation types, and organic carbon inputs differ substantially, remains untested. Furthermore, for sediments older than 15 ka, uncertainties arising from the procedural blank and counting statistics may become significant. More work is needed to measure the effect of washing sediment with acid or acid and base, the common pre-treatment procedure used for measuring 14C in bulk-sediment, to test our contention that retaining the dissolved OC fraction is advantageous when determining its depositional age. Finally, it should be possible to use initial loss-on-ignition trials to optimize the heating temperature at each lake rather than using a fixed temperature of 250°C for all lakes. Sediments containing a high proportion of residual OC could be heated at temperatures lower than 250°C to further avoid the inclusion of the old OC.

Conclusion

We developed a procedure for 14C dating bulk sediment using a simple mixing model to calculate the Fm of OC combusted at relatively low temperature. The procedure’s simplicity makes it practical for routine analysis of a large number of samples. A temperature cutoff of 250°C was selected for combusting the labile fraction of OC while avoiding the recalcitrant older OC in bulk sediment. The procedure yields 14C ages that objectively more closely approximate the true depositional age as represented by macrofossil ages. The method significantly improved bulk-sediment ages in three out of the five lakes analyzed, highlighting its potential to improve age-depth models in lacustrine settings where macrofossils are not available or not analyzed. It generates reproducible results, with pairwise differences in replicate analyses comparable to those observed for macrofossil ages. Moreover, the estimated uncertainty of the low-temperature ages is reasonable, particularly given that the ages are themselves approximations of the depositional age. The accuracy of the low-temperature ages can be evaluated based on the portion of OC remaining after heating, with bigger differences when compared to macrofossil ages for sediment with more abundant recalcitrant OC. Furthermore, in settings where macrofossil-based ages are available, the low-temperature combustion procedure yields ages that can provide insights into carbon-cycle dynamics.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2025.10167

Acknowledgments

We thank undergraduate students Brooke Damon, Greta Freeman and Charlie Kruger for their assistance with preparing macrofossil samples, and our collaborators Haflidi Haflidason, Martin Melles and John Inge Svendsen for providing samples from the Eurasian lakes. The manuscript benefited from suggestions by Martin Melles, A. J. Timothy Jull and an anonymous reviewer. This study was funded by NSF awards 2317409 and 1947981.

Data availability

The data generated for this study are available through the NSF Arctic Data Center (doi: 10.18739/A2319S47J).