Food insecurity is a problem not only in developing countries but also in high-income Western countries such as the USA (12·3 %)(Reference Coleman-Jensen, Rabbit and Gregory1), Canada (12·0 %)(Reference Tarasuk, Mitchell and Dachner2), the UK (10·1 %)(3) and France (12·2 %)(Reference Bocquier, Vieux and Lioret4). In a wealthy country such as the Netherlands, over 1·2 million people (7·5 %) live below the poverty line(Reference Hoff, Wildeboer Schut and Goderis5) and over 132·000 people (0·8 %) rely on food banks for their food intake(6). A robust national prevalence of food insecurity in the Netherlands is lacking, but the prevalence of food insecurity among Dutch food bank recipients is 72·9 %, of which 40·4 % reported very low food security(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Visser7). The Dutch Food Bank is a charitable non-governmental organisation, which collects and distributes donated foods through food banks throughout the Netherlands. It aims to support the poorest people and to counteract food waste by providing food parcels that supplement the habitual diet for 2–3 days.

From literature it is known that in Western countries, in general, people do not meet the dietary guidelines for a healthy diet(Reference Heuer, Krems and Moon8–Reference Lee-Kwan, Moore and Blanck14). For example, only 13 % and 8 % of the Dutch adults meets the daily recommendation for fruit and vegetables(Reference Rossum van, Fransen and Verkaik-Kloosterman11). People with low socioeconomic status (SES) and food assistance program users, i.e. eligible low-income families and individuals who make use of temporary food assistance programs such as food banks, food pantries and the supplemental nutrition assistance program have even poorer diets(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Dekkers15–Reference Robaina and Martin18). In the Netherlands, mean intakes of energy, fiber, fruit and vegetables of food bank recipients were found to be significantly lower compared to both the general and the low-SES population(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Dekkers15). Food parcels, supplied to people in food assistance programs, provide an opportunity to improve the diets of food bank recipients. However, previous studies have shown that food parcels vary in their provision of macronutrients and food groups, often failing to meet dietary recommendations(Reference Akobundu, Cohen and Laus19–Reference Teron and Tarasuk21). Moreover, they provide little fruit(Reference Akobundu, Cohen and Laus19,Reference Irwin, Ng and Rush20,Reference Hoisington, Manore and Raab22) . Our previous work showed that the content of food parcels supplied by the Dutch food bank is not in line with the dietary guidelines for a healthy diet. The food parcels provided high amounts of energy, protein and saturated fat, whereas the provided amounts of fruits and fish were too low to meet the guidelines(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Visser23).

Food bank recipients are thus a vulnerable group of people and of nutritional concern. It currently remains unclear how their dietary intake can be improved and what changes in the food parcels are needed to support this improvement. Accordingly, it should be studied how Dutch food bank recipients perceive the (use of) food parcels they receive and how these food parcels impact their dietary intake. Therefore, the aim of our study is to gain insight in Dutch food bank recipients’ perception on the content of the food parcels, their dietary intake and how the content of the food parcel contributes to their overall dietary intake.

Methods

Ethical approval

This qualitative study was part of the Dutch Food Bank study, which aimed to explore and optimise food choices and food patterns among Dutch food bank recipients. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, as well as the national board of the Dutch Food Bank. Participants were exempt from signing informed consent by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU Medical Center.

Sampling and recruitment

Food bank recipients (hereafter called ‘participants’) were recruited through information letters, active recruitment and promotional posters at 7 food banks across the Netherlands in two small cities (i.e. <50,000 inhabitants: Huizen and Vught), one medium size city (i.e. 50,000–150,000 inhabitants: Hoofddorp) and four larger cities (i.e. >150·000 inhabitants: Amersfoort, Amsterdam, Breda and Haarlem). They could sign up for the study with an application form, by telephone or e-mail within 2–3 weeks after recruitment. Inclusion criteria for participation were 1) >18 years of age and 2) adequate command of the Dutch language to participate in a focus group discussion. Only one member per household was enrolled. In total, 125 food bank recipients indicated that they were interested to participate, of which 45 (36 %) actually participated. For 38 of the 80 recipients who signed up for participation, but did not participate, we were able to ascertain the reason for non-participation; 1) not able to participate because, for example, work, illness, other appointments or children at home (n 35), 2) not a food bank recipient anymore at the start of the study (n 1) and 3) no adequate command of the Dutch language (n 2). Of the 45 remaining recipients who did not participate after signing up, 27 recipients did not fill in the correct contact information or did not respond to e-mail and/or phone calls from the researchers. After inclusion, food bank recipients were contacted by phone or e-mail to set a date, time and location for the focus group discussion. They were also asked some questions to be able to provide insight into participants’ characteristics (i.e. age, duration of being recipient at the food bank, highest finished education and household size). Data of one female participant were excluded because her command of the Dutch language was insufficient to participate in the focus group discussion.

Theoretical framework

Food insecurity can be defined as a lack of access by all people to enough food for an active, healthy life which includes at a minimum: a) the ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods and b) the assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways(Reference Anderson24). Food insecurity is highly prevalent among Dutch food bank recipients(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Visser7). It has been associated with unfavourable food choices(Reference Tarasuk25) and a less healthy diet(Reference Hanson and Connor26,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk27) in food bank recipients(Reference Neter, Dijkstra and Dekkers15–Reference Robaina and Martin18). We used the definition of food insecurity by Anderson(Reference Anderson24) as a framework to guide the development of focus group discussion topics and incorporated topics such as the ready availability of nutritionally adequate foods (i.e. acceptable in quality or quantity) and the assured ability to acquire foods in socially acceptable ways (e.g. without resorting to emergency food supplies, scavenging, stealing and other coping strategies) into the discussion guide.

Interview topics

Focus group discussions were considered most appropriate to gain insight in participants’ perception on the impact of food parcel use on their dietary intake. This qualitative method is effective in gathering insights into relatively unexplored topics(Reference Baarda, de Goede and Teunissen28). Eleven focus group discussions were held in the Dutch language between March and June 2012. All focus group discussions were held at the food bank or at a location near the food bank and lasted approximately 1·5 hour. They were conducted with two researchers; one interviewer (JEN) and one observer (SCD) who took field notes and asked extended questions if necessary. Before the start of each focus group discussion, all participants were informed that the focus group discussions would be audio-recorded, and they were asked to give their consent verbally, with assurances that their anonymity would be protected. All participants were given the opportunity to discontinue participation, but none of the participants did. Participants were informed that the goal of the meeting was to discuss their perception of the content of the food parcel, their eating habits and their purchase of foods.

Throughout the sessions, an effort was made to actively involve all participants, by encouraging them to express and share their opinions. For people who are struggling to feed themselves or their family we expected that it would be difficult to talk about food with a complete stranger. Thus, during the focus group discussions, we strived to approach participants with respect and sensitivity. Furthermore, when focus group discussions were held at the food bank, no staff or volunteers of the food banks were present so that participants would feel free to speak openly.

The focus group discussions followed a semi-structured format. Each focus group discussion started with a short introduction, followed by two generic questions: 1) ‘what is your age?’ and 2) ‘what is your favorite food?’ to make participants feel at ease. Thereafter, a topic list including questions on the food parcels, dietary intake in general and additional purchasing of foods was used to guide the discussions. The topic list was adapted continuously during the study in order to include relevant topics as they arose.

Prior to this study, the topic list was tested on a convenience sample of two women from a food bank in the center of the Netherlands in order to determine whether the topics and questions were clear and how much time it would take to conduct the focus group. Minor changes were made in the formulation of some questions in the topic list to improve their clarity. Data of this pilot study were included in the data analysis. All participants received a small incentive (e.g. shower gel, shampoo, liquid detergent).

Data analysis

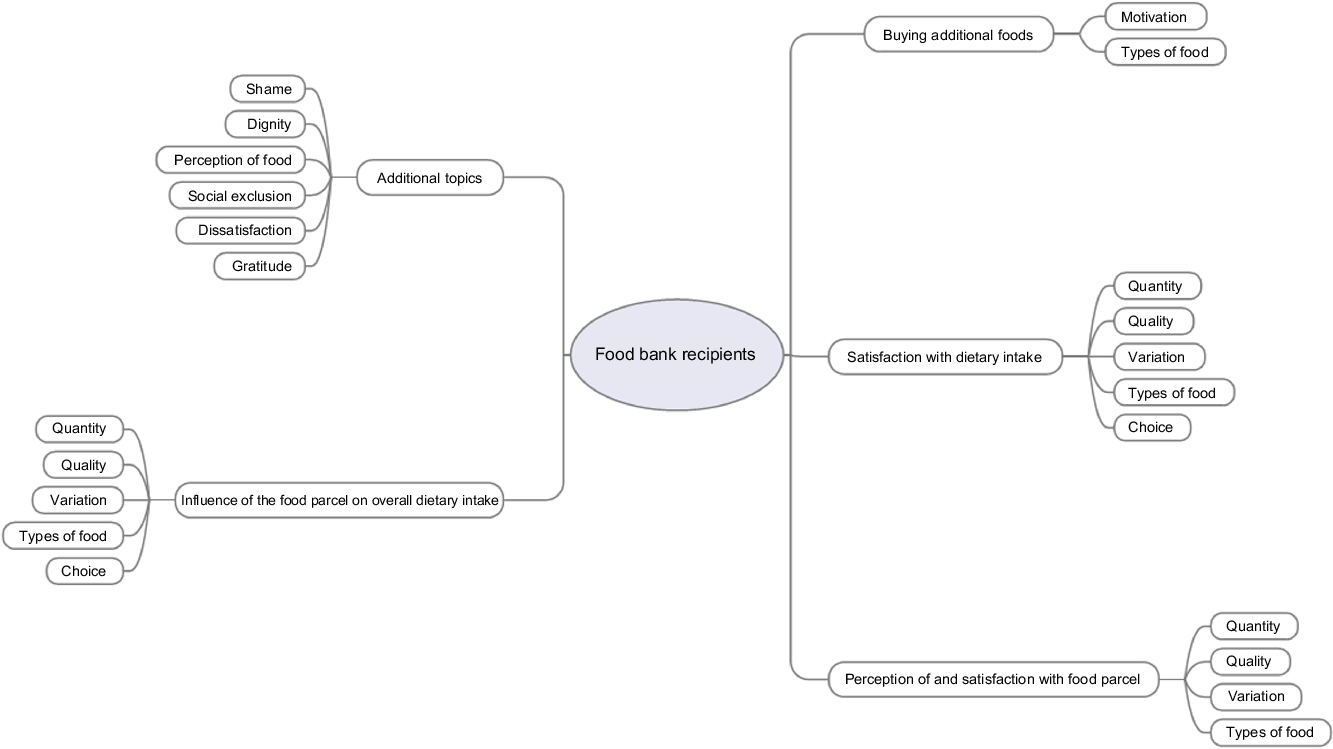

The second author (SCD) and two research assistants transcribed verbatim all recorded focus group discussions. Transcripts were coded and analysed using the software package Atlas.ti version 7.0 using the framework approach(Reference Ritchie and Lewis29) consisting of the following five steps: (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) highlighting quotations in the transcripts; (3) assigning codes to the quotations; (4) reassigning the codes into larger families (Fig. 1) and (5) rearranging the families into the thematic framework. The first author (JEN) used open coding(Reference Boeije30), and a random sample of 2 transcripts was similarly coded by the second author (SCD) to check for inter-coder agreement. The coding was discussed by both coders; there was a high level of consensus between the two coders so it was concluded that double coding all focus groups was not necessary. Codes were organised according to the main themes that were identified during analysis and in concordance with the framework that we used. Quotes were selected to reflect the different perceptions on the impact of food parcel use on dietary intake. The specific quotes were selected on the basis that they illustrated a variety of response types, including responses which were typical or common; unusual responses; responses which represented a concise summary of a discussion topic or responses showing a range of viewpoints on a topic. Anonymised, illustrative quotes are used in the results section to illustrate the key themes. The Dutch quotes were translated to English, and these translated English quotes were presented to a native speaker who also speaks Dutch fluently (MN), so it would meet the Dutch quotes closely, in reasonable English.

Fig. 1 Overview of code families

Results

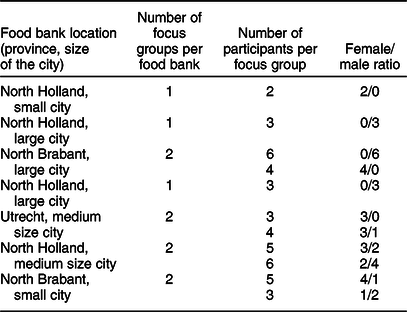

In total, 22 female and 22 male food bank recipients from 7 food banks participated in 11 focus group discussions. The number of participants per focus group ranged from two to six. Age ranged from 20 to 64 years and the duration of being food bank recipient from 1 week to more than 3 years. Level of education was known for 30 of the 44 participants. The majority of these participants (66·7 %) had a medium level of education (high school, general intermediate and lower vocational education, general secondary and intermediate vocational education). An overview of the number of focus groups per food bank, the number of participants per focus group and female/male ratio are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Overview of the number of focus groups of the Dutch Food Bank Study per food bank, the number of participants per focus group and female/male ratio

The findings were divided into four areas covered in the results: perception and satisfaction with the content of the food parcel; buying additional foods; satisfaction with dietary intake; influence of the food parcel on overall dietary intake. Within each of these different areas, aspects of the theoretical framework are highlighted. We also present a number of issues that were not part of our initial topic list.

Perception of and satisfaction with the content of the food parcel

The majority of the participants expressed the opinion that they are not (completely) satisfied with the content of the food parcel. Some aspects were mentioned in particular: nutritional adequacy in terms of the amount of food, the variation of foods in the parcel and acceptability of foods, in terms of the quality of the food, personal preference and, also, the types of foods available in the parcel.

With regard to nutritional adequacy, much discussion revolved around the amount of food in the parcel. Participants mentioned that the amount of food in the food parcel had decreased over time and that it was not enough to feed all the people in the household. An important issue that came up while discussing the amount of foods supplied is that most participants seemed not to be aware of the fact that the food parcel is aimed to supplement the normal diet for only 2–3 days a week instead of providing food for a complete week. To illustrate, one participant said ‘We have to live from the parcel with 5 people, that is impossible. It is very meagre… (M, 50 - A)’. Whether the amount of foods is enough, also depended on the household composition and size, and on whether one consumes all the foods available from the parcel. To illustrate, one participant said ‘I eat well from the parcel. I live alone (M, 61 y)’. Another participant said ‘I do not eat foods from the food parcel. My kids eat from the parcel. I do not eat anything from the parcel (F, 44 y)’. Additionally, one participant stated ‘I feed my children first. If they are finished, I collect their leftovers in a Tupperware container. I have a container, I do not eat from a plate anymore, I eat leftovers from a container (M, 50 y - A)’. Furthermore, another participant said ‘We always accept all offered products. And we also eat everything (F, 49 y)’.

Participants also discussed the foods available in the parcels in terms of their nutritional balance. Participants mentioned that they often miss foods to prepare a complete meal. For example, the food parcel may contain sauce and vegetables for a pasta dish but no pasta. Especially participants without children mentioned that the food parcel contains a lot of or even too many sweets and salty snacks. One participant stated ‘I think that there is a considerable amount of sweets and cookies in the parcel (M, 48 y)’. In addition, another participant said ‘I have never had so many sweets and salty snacks in my pantry (F, 45 y)’. Although some participants were happy to serve the sweets to guests, most participants said they would prefer a bag of potatoes, apples or a bunch of bananas instead. Overall, many participants discussed how many foods in the parcel are not very healthy. To illustrate, one participant said ‘No offense, but it (i.e. the food in the parcel) is not always very healthy (F, 57 y - A)’. Additionally, a participant stated ‘No, if you look at the nutritional content, it is simply deficient (M, 50 y - B)’. Another participant stressed that this is a big problem for growing children.

Regarding the quality of the foods, participants mentioned mostly that they always had to pay attention to the expiration date of the foods in the parcel because many foods were close to or even beyond this date. One participant said ‘Many foods cannot be stored. You have to consume it the same day or the day after. Otherwise you cannot use it anymore (F, 52 y)’. Other participants added that especially the quality of bread, fruits and vegetables is poor. One participant said ‘On Friday, when I receive my parcel, I spend all afternoon preparing the food. I store it in the freezer so that it stays fresh (F, 44 y)’.

Participants addressed the limited variation in the foods they received, specifically the lack of variation in vegetables. One participant said ‘I receive the same type of vegetables every week. Every week the same. What can I make with the same vegetables every week? (M, 47 y)’. Some other participants added that they agree that the content of the parcel lacks variation, but when you are creative you can make several dishes from the same foods.

Participants said that the foods in the parcel are not always acceptable to them, i.e. they contain foods that they do not like or prefer to eat. When allowed by the local food bank, the majority of participants do not take these foods home or give them to others that could use the extra food. Most stated that they prefer not to throw these foods away. Finally, participants mentioned that some foods were frequently missing in the parcel: dairy, fruit, meat, fish, coffee and fresh foods in general. Few participants stated that they were (completely) satisfied with the content of the food parcel; the amount, the quality as well as the variation of the foods. Importantly, although the majority of the participants is not completely satisfied with the content of the food parcel, they generally stated that they were really grateful for receiving it.

Buying additional foods

The affordability of foods to supplement the food parcel appears to be the main driver of food choice and overshadowed other aspects such as nutritional adequacy or acceptability. Many participants discussed not being able to afford to buy foods to supplement the food parcel. To illustrate, one participant said ‘I’ve accepted that I don’t have much… that I can’t buy anything… (F, 57 y - B)’. For the participants who could afford to, most reported buying foods that are insufficiently provided or completely lacking in the parcel, or to replace foods in the parcel that cannot be eaten due to their poor quality. Participants stated that ‘It is not in the food parcel, but you need it (M, 50 y - A & M, 52 y)’. Another participant said ‘Not all ingredients are always there for a complete meal (F, 20 y)’.

Participants named various aspects they considered important in choosing which foods to buy. Almost unanimously they indicated that price is the most important aspect of whether they buy a certain food or not, the choice of which type of food to buy, the selection of specific foods within a product category, but also the price per volume ratio. To illustrate, participants said the following: ‘Of all the foods I buy, I choose the cheapest, otherwise I cannot afford it. All healthy foods are also very expensive. Thus, you choose the cheapest meat, cheapest butter, cheapest this… And that is not always the best (M, 48 y)’, ‘I buy as much as possible for the lowest price (M, 64 y)’, ‘I study all the advertising brochures and if I have to bike a bit further, I do so. I often do that at the end of the day, then you get 35 % discount (F, 49 y)’, ‘I usually look to see if there is a promotional price for fruit. Then I buy it (F, 48 y)’. Other important aspects in buying foods that were mentioned were quality (over quantity), treating yourself and health. To illustrate, one participant said ‘I think I pay attention to the nutritional content of foods, that is hard because healthy is also more expensive. You try to buy food to compensate for the unhealthier food from the parcel. The oxidants (i.e. antioxidants) for example (M, 53 y)’.

The most frequently mentioned foods bought to supplement the food parcel were vegetables, fruit, bread, meat and meat products, coffee, (soft)drinks, cheese and butter/oil. Also mentioned, but less frequently, were milk and other dairy products, potatoes, fish, pasta/rice and filling.

Satisfaction with dietary intake

Numerous participants indicated that they were not satisfied with their dietary intake. Several specific topics were mentioned, of which nutritional adequacy, specifically insufficient quantities, was most frequently stressed. Some participants reported experiencing hunger but not having money to buy food. An illustrative citation was: ‘I often go to bed feeling faint, I really go to bed hungry. I have way too little food (M, 63 y)’. In addition, one participant said ‘I eat 1000–1500 kilocalories per day. If I can, but sometimes less (M, 53 y)’. Some participants mentioned they would prefer to eat more healthy foods. For example, one participant said ‘I wouldn’t say I was satisfied. The most important things you need are vitamins, and most of the products do not contain vitamins (F, 48 y)’.

As with the content of the food parcels, participants discussed how their overall dietary intake was not acceptable to them due to lack of variation, lack of quality, lack of choice and the type of food. Participants wished not only for more variation and for products of higher quality regarding the ingredients but also products that have been produced and processed in ways that are friendly to the environment. Furthermore, participants said they often eat foods they would not have chosen themselves, and that it is frustrating not to be able to choose what to eat because they depend on the food parcel. To illustrate, one participant said ‘You do not have a choice yourself and I think that is frustrating sometimes, it (i.e. my dietary intake) lacks variation (F, 42 y)’.

Not all participants were dissatisfied with their dietary intake. Many indicated being satisfied and having enough to eat. Another group of participants said that the degree of satisfaction depended on the content of the food parcel i.e. the amount and the type of foods supplied. In addition, some participants stated being satisfied and accepting their situation as it is. Sometimes they wish for more, qualitatively better or other types of foods, but because they are so grateful for receiving a food parcel they feel that they do not have the right to complain. To illustrate one participant said ‘I have to be honest, I don’t eat tasty food like I used to. That is true. I cannot deny that. You adapt to the situation (M, 50 y - A)’.

Influence of the food parcel on overall dietary intake

The content of the food parcel seems to importantly influence participants’ overall dietary intake. One participant stated ‘The content of the food parcel influences my dietary intake for 100 %, because I completely rely on the food parcel. I absolutely do not eat what I like, but I eat what is available (M, 50 y - B)’. Another participant said ‘Other types of food come into the house. I have the tendency to eat more candy than before. And also more meat than before (M, 60 y)’.

Additional topics

During the focus group discussions, a number of relevant issues arose that were not initially included in the topic list, but which are useful in the interpretation of participants’ discussions and for understanding the context in which they live. An important theme that emerged from the focus group discussions was the socio-psychological impact of being a food bank recipient, whereof participants shared harrowing personal issues. First, participants said that it was a big step to go to the food bank for the first time because they felt ashamed. To illustrate, one participant said ‘I did feel ashamed in the beginning. I thought gosh I have to stand in line here. [Expletive] but you do get used to it (F, 55 y)’. Some participants explained that it took a couple of weeks before they were ready to take that step. Second, being dependent on help from other people (e.g. the food bank or your own children) makes food bank recipients lose their dignity. One participant stated ‘Then I go to bed hungry and think I don’t know what to do today. I do not dare to turn-up at that woman’s or man’s house anymore at dinnertime. It is too embarrassing (M, 63 y)’. In addition, one participant said ‘My daughter works at a supermarket. She goes to school 2 days a week. She needs to help me out from time to time. I feel really bad about that (F, 39 y)’. Third, food gains a different function in their lives. Due to a lack of the right amount, good quality, variation and foods participants like they think of food as something they need to fill their empty stomach with, as a means to survive. To illustrate, one participant said ‘One is conditioned by hunger. Nowadays I suffer less from hunger. I have been hungry many times throughout my life. It is a trick playing with you. At some point you reach a point that you go beyond the feeling of hunger and then you suffer less from it, …. After a while food is not a part of your life anymore. It is there, but you don’t pay attention to it. In normal life you spend a lot of time on food. You go to a store, and you are confronted with foods you don’t like, thoughts on how to prepare foods, …. You are busy with it, food is close to you. For me, food is far away. I can live with an empty stomach for a long time. I have to fill it (i.e. my stomach), but you don’t have the luxury to choose (M, 53 y)’. Another participant stated ‘I decided to see it (i.e. food) as something to fill my stomach with, …. I don’t think about what I like to eat at all because I cannot handle that, …. My stomach starts to growl at 6 o’clock and then it needs to be filled (M, 50 - B)’. In addition, they feel like they are not able to be critical because they are, or at least should be, happy with the food they receive. One participant said ‘I would rather eat qualitatively better food, but also better food for the environment. In that sense I am not satisfied. But I hardly can expect that. You don’t have that choice. Food quality became less important to me (M, 60 y)’. In addition, it was stated ‘Well, in this crisis, I think that you just have to accept what you eat, …. You can’t change anything (F, 48 y)’. Also, it was mentioned that participants feel unhappy and ashamed of being unable to serve their children a proper meal. To illustrate one participant said ‘My son doesn’t live with me, but he regularly wants to join me for dinner because he enjoys that. But when he asks ‘mom can I join for dinner’ I panic. Then I think [expletive], I can’t serve him a boiled egg (F, 54 y)’. Finally, they often reported feeling socially excluded because they cannot take part in social activities such as meeting family or friends, e.g. drinking coffee or having lunch because they do not have money and/or sufficient food. One participant said ‘Your social life is completely different. I used to invite people for dinner and then you were invited back for dinner, that type of thing. Now, I avoid those things such as birthdays, parties, dinner parties, anniversaries because that just doesn’t work anymore (F, 46 y)’. These additional issues clearly show that participants in our study not only experience a lack of access to sufficient, nutritionally adequate food but also that they do not have the assured ability to acquire foods in socially accepted ways.

Discussion

This study revealed that food bank recipients are not always satisfied with the amount, quality, variation and the type of foods in the food parcel. Participants reported that 1) the amount of food was not enough to feed all the people in the household, 2) they always had to be aware of the quality of the foods because many foods were close to or even beyond the expiration date, 3) there was limited variation in foods supplied, in particular for the vegetables and 4) the foods in the food parcel were not always foods they liked or preferred to eat. Of the participants who can afford to supplementing the food parcel was reported as main reason for buying foods. Price was indicated as being the most important aspect in selecting foods to buy. Furthermore, participants reported that they were not satisfied with their dietary intake, mainly because they do not have enough to eat. In addition, the content of the food parcel seems to influence participants’ overall dietary intake with regard to amount, variation, quality and type of food. Finally, participants reported struggling with their feelings of dissatisfaction, while also being grateful for the foods they receive.

An important issue raised during our focus groups was the mismatch between the amount of food supplied by the food bank and the amount that recipients seem to need. This might be due to a lack of awareness by participants that the parcel is aimed to supplement the diet for only 2–3 days instead of per week. Many participants indicated that they could not afford to buy additional foods, and thus were completely reliant on the content of the food parcel for their dietary intake. Our results with regard to dissatisfaction with the amount, variation and quality of foods supplied in the parcel are in line with other studies(Reference Verpy, Smith and Reicks31,Reference Nagelhout, Hogeling and Spruijt32) . Most of the participants in a focus group study by Verpy et al.(Reference Verpy, Smith and Reicks31) indicated relying on the food bag provided once a month and sufficient for 5–7 days to get by and felt that the amount of food they received was inadequate. As in our study, participants with children in the house reported that they would go hungry so that the children could eat. This was also confirmed in a study by Dave et al.(Reference Dave, Thompson and Svendsen-Sanchez33), especially by mothers.

Participants in our study also addressed the limited variation in and poor quality of the foods supplied, specifically with regard to the vegetables. These results were confirmed in several studies. Participants in the focus group study of Nagelhout et al.(Reference Nagelhout, Hogeling and Spruijt32) said that there is a lack of variation in the provided fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, they expressed that the vegetables often have to be eaten the same day due to poor quality. Regarding quality of the food in the food bags, participants in the study of Verpy et al.(Reference Verpy, Smith and Reicks31) expressed their concern that they had received numerous products that were past expiration dates. Poor quality of the food was also consistently reported in studies included in a review by Middleton et al.(Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34). Furthermore, in line with our study, it was mentioned that people do not say they are ungrateful because the food helps, but the food bags do not necessarily meet their nutritional needs(Reference Verpy, Smith and Reicks31).

Of the participants who can afford buying additional foods, supplementing the food parcel was reported as the main reason for buying foods. Price was indicated as being the most important aspect in selecting foods to buy. It was also mentioned by participants that healthy foods are usually too expensive to buy. This is consistent with other studies, in which food assistance program users(Reference Nagelhout, Hogeling and Spruijt32,Reference Dave, Thompson and Svendsen-Sanchez33) or low-SES groups(Reference Bukman, Teuscher and Feskens35) mentioned price as the most important barrier to buy and eat healthy foods. Less nutritious, energy-dense foods are often cheaper(Reference Drewnowski36,Reference Jones, Conklin and Suhrcke37) , and higher diet quality has been associated with higher diet costs(Reference Bernstein, Bloom and Rosner38,Reference Rehm, Monsivais and Drewnowski39) , although the evidence is inconsistent(Reference Giskes, Van Lenthe and Brug40). However, purchasing unhealthy foods is strongly associated with SES(Reference Giskes, Van Lenthe and Brug40,Reference Pechey, Jebb and Kelly41) .

In our study, participants indicated that their dietary intake is greatly influenced by the content of the food parcel. This seems evident since many participants largely or completely rely on the content of the parcel. Consistent with the findings of Nagelhout et al.,(Reference Nagelhout, Hogeling and Spruijt32) participants reported receiving unhealthy foods from the food bank, with little variation in the fruits and vegetables. It seems therefore plausible that insufficiencies in the food parcel would result in poor dietary intakes. Also, in line with previous studies, participants indicated a desire to be able to have more choices in the types of food they receive(Reference Verpy, Smith and Reicks31,Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34) , to meet individual food preferences and to be able to receive foods that allow them to plan and prepare complete meals for their families.

Our results indicate that food bank recipients vary in the way they are able to deal with the situation they are in. Some participants seem better to be able to cope with the situation of experiencing financial distress, than others. These participants are capable of visiting numerous supermarkets to buy necessary additional foods as cheaply as possible, are creative with the content of the food parcel (e.g. cook different meals with the same ingredients) and prepare meals for the whole week on the day they received the food parcel in order to avoid food spoilage. Other food bank recipients suffer greatly from their financial distress and do not seem to have the time and energy to cope with their situation. Bukman et al.(Reference Bukman, Teuscher and Feskens35) reported that having enough time and energy was an important requirement for having a healthy diet in participants motivated to live healthily. Furthermore, Beenackers et al.(Reference Beenackers, Oude Groeniger and van Lenthe42) showed that both experiencing financial distress and having low self-control are associated with unhealthy behaviours (i.e. physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking). It seems that those having low self-control are less capable of resisting impulses leading to unhealthy behaviours. These results suggest that some food bank recipients might need extra help (e.g. coping with financial problems) in addition to the food parcel, to be able to eat healthy.

Our study also provided some additional insights into the socio-psychological impact of being a food bank recipient. Consistent with the findings of a review by Middleton et al.(Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34) we showed that being dependent on others and on the food bank, being unable to serve your family and especially your children a proper meal goes hand in hand with a sense of shame, embarrassment, and loss of dignity. Furthermore, as in our study, Middleton et al.(Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34) showed that participants feel obliged to show gratitude towards the volunteers and the service, even if they are not satisfied with the services. Social impact was also mentioned in the review by Middleton et al.(Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34), but in a different way than in our study. Middleton et al.(Reference Middleton, Mehta and McNaughton34) described food bank recipients’ fear of being judged and fear of being of social stigma, whereas we found that food bank recipients often feel socially excluded as food is often a part of social interaction. In addition to the existing literature, we found that food becomes just something food bank recipients need to survive, the pleasure of eating is degraded by the lack of sufficient, varied food of good quality.

Strength of this study is that it is the first to give insight in Dutch food bank recipients’ perception on the content of the food parcels, their dietary intake and how the content of the food parcel contributes to their overall dietary intake. It does not only provide insight in how the food parcels could be improved according to the recipients, thereby likely increasing their satisfaction about their dietary intake, but also provides information on which factors influence variations in the degree of satisfaction with the food parcels, dietary intake and contribution of the parcel to overall dietary intake. Furthermore, strengths include the relatively high number of participants and food banks included in this study.

A possible limitation of this study is that bias may have occurred in the selection of participants. First, an inclusion criterion for this study was an adequate command of the Dutch language to participate in a focus group discussion. It is likely that we have missed an important, perhaps more deprived, population segment in this study. This may imply that the results described are less representative for those with an inadequate command of the Dutch language. Second, we cannot exclude that we oversampled participants with strong negative opinions about the topics we discussed, which consequently may have led to an overestimation of negative perceptions. However, our findings concur with findings of earlier studies on perceptions of food bank recipients. Next, although there were few discrepancies between the two coders, only part of the data was coded by two coders. Furthermore, we held the focus groups in our role as nutrition researchers aiming to answer our research question and therefore mainly focused on the topics related to food parcel use and dietary intake. The psycho-social aspects that emerged during the focus groups are at least as important and merit more attention in future studies. Finally, we chose to hold focus group discussions, the group setting may have limited some participants in expressing their views. Although we did our best to present a neutral, safe environment for discussion, other methods may have provided additional or different types of information. Future studies may wish to employ in-depth interviews, or ethnographic participation methods in which the researcher joins in and becomes part of the group they are studying in order to get a deeper insight into their lives.

Practical implications

Our results are of great importance as they can serve as a starting point to improve food bank recipients’ satisfaction with the food parcel and consequently their dietary intake. Food banks aim to supplement the normal diet for 2–3 d per week, and they do everything to provide the best food parcels they can, but food bank recipients indicated that they often do not have enough to eat. The latter is especially the case in families with children. Food banks need to be aware that many recipients – especially families – do not have enough to eat. Thus, finding ways to increase the amount of foods as well as the nutritional quality of the foods in the food parcel is important. Furthermore, food parcels need to be better tailored to the needs of the recipients based on household size, household composition, taste preference, religion, allergies and health issues. Ultimately, this will increase the food security status of food bank recipients.

Nutrition education and the provision of recipes need to account for the limitations food parcel recipients face in meeting dietary recommendations. A major issue is that many recipients do not have the option to purchase additional ingredients to meet nutritional advice or prepare recipes due to limited budgets. Furthermore, providing recipes based on the content of the food parcel is not feasible since many food banks receive a large part of the donations shortly before supplying the food parcels. Some food banks offer classes on managing food budgets but since we showed that many food bank recipients do not have money to spend on food to supplement the food parcel, we would not advise such classes as this may cause distress to people who do not have a food budget. Overall, it seems not to be possible to formulate unequivocal advice regarding nutrition education because not all food banks nor their recipients are able to follow the advice, i.e. they are all unique. Thus, we advise tailored nutrition education and help with coping with financial distress for food bank recipients.

Conclusions

Food bank recipients indicated that they were not always satisfied neither with the food parcel nor with their dietary intake, mainly because they do not have enough to eat. Their overall dietary intake seems to be largely influenced by the content of the food parcel, which may be due to limited resources to buy additional foods to supplement the food parcel. It is clear that despite their best efforts, food banks are currently not meeting food bank recipients’ needs when the food insecurity definition by Anderson(Reference Anderson24) is applied. Furthermore, our results provide valuable directions for improving the content of the food parcels: higher amount of food, better quality of fresh food and more variation in the foods supplied. Whether this also improves the dietary intake of recipients needs to be determined. In addition, future research should also take into account the socio-psychological aspects of being a food bank recipient. More research is needed to confirm the results presented is this paper.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the participating food banks for their cooperation, the food bank recipients for their participation and the research assistants for their help in transcribing data. Financial support: The Food Bank Study was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (115100003). Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authorship: J.E.N., I.A.B. and M.V. designed the research. J.E.N. conducted the interviews and analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.C.D. analysed a subset of the transcripts. M.N., M.V. and I.A.B. contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.E.N. has primary responsibility for the final content. All authors were involved in the development of the manuscript and read and approved the final version. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the VU University Medical Centre Ethics Committee. Participants were exempt from signing informed consent by the Medical Ethical Committee of the VU Medical Center.