Whole grains are an important part of a healthy diet as an excellent source of protein, carbohydrate, including fibre, and many essential vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals and antioxidants(1). Internationally, it is strongly encouraged that whole grain foods are incorporated daily into the diets of individuals due to their numerous potential health benefits(Reference Chen, Tong and Xu2–Reference Newby, Maras and Bakun8). Despite extensive epidemiological research on health benefits and international recommendations to consume between 48 and 90 g whole grain per day, the intake of whole grains globally remains low(Reference Galea, Beck and Probst9–Reference Sette, D’Addezio and Piccinelli14).

There are, however, inconsistencies among data regarding the association of whole grain intakes with health outcomes, in particular mortality(Reference Jacobs, Andersen and Blomhoff15–Reference He, van Dam and Rimm20), which may be in part explained by variation in the calculation of whole grain intake among studies. Specifically, there are differences in definitions of what contributes to whole grain intake and what constitutes a whole grain food(Reference Ferruzzi, Jonnalagadda and Liu21,Reference Wu, Flint and Qi22) . For example in the United States, whole grain foods are defined as those containing ≥51 % whole grain by weight per reference amount customarily consumed (RACC) by the United States Food and Drug Administration(23), ≥8 g of whole grain per 30 g of product by the American Association of Cereal Chemists International (AACCI)(24), while the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans use multiple definitions to classify whole grain foods(25). Therefore notably, some studies include any amount of whole grain from any foods(Reference Wu, Flint and Qi22,Reference Kranz, Dodd and Juan26) , some specify a minimum whole grain proportion in foods and only count contributions from those foods(Reference Steffen, Jacobs and Stevens17,Reference Sahyoun, Jacques and Zhang19) and some include bran as a whole grain despite not meeting recognised definitions(Reference He, van Dam and Rimm20,Reference Jacobs, Meyer and Kushi27) .

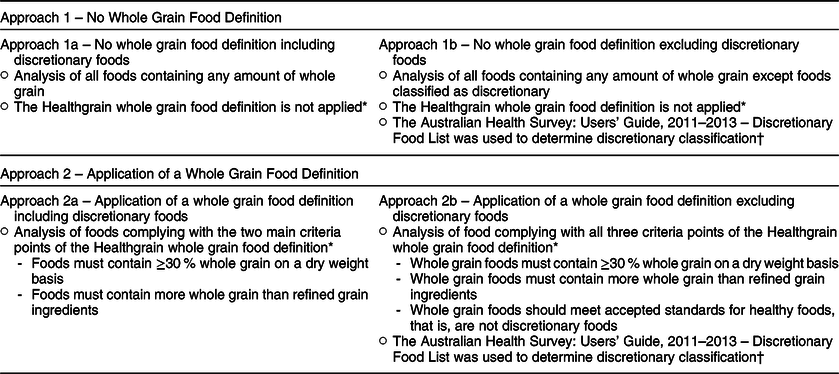

In response, the Healthgrain Forum, an international group of scientists, industry representatives and policy-makers advocating for whole grains, have made recommendations for a whole grain food definition that could be applied uniformly across the globe (Table 1)(Reference Ross, van der Kamp and King28). Previously, calculation of whole grain intake in Australia has included grams of whole grain from any source (whether a ‘whole grain’ food, or a food with some amount of a whole grain ingredient)(Reference Galea, Beck and Probst9). Using this method, as opposed to more restrictive definitions of whole grain foods, may hold relevance in the context of examining health outcomes associated with whole grain intakes.

Table 1 Summary of the Healthgrain Forum whole grain food definition*

* Definition adapted from Ross et al. (2017)(Reference Ross, van der Kamp and King28).

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the impact of using a whole grain food definition on calculated whole grain intake by 1. determining whole grain intakes in Australian individuals, based on foods that comply with the Healthgrain whole grain food definition and 2. analysing the difference in whole grain intakes when all foods containing any amount of whole grain are included. This also allowed specific analysis of the grams of whole grain which may be contributed from intake of discretionary (higher fat, sugar and salt) foods. The National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–2012 of Australia is used for the current analysis.

Methods

In brief, the current study investigated the application of the Healthgrain whole grain food definition to the NNPAS 2011–2012 dietary intake data. Results were then compared with whole grain intakes, of the same dietary intake data, when no whole grain food definition was applied. Furthermore, it was of interest to investigate the food sources of whole grain in the sample.

Data and survey population: NNPAS 2011–2012

The NNPAS 2011–2012, a component of the Australian Health Survey, collected data specifically related to health, nutrition and physical activity of 12 153 individuals aged 2 years and over. Participants of the survey were usual residents of private dwellings in both rural and urban areas of Australia; however, individuals living in very remote areas were excluded. A complete description of the methods and recruitment of participants are provided elsewhere(29).

Dietary intake data

The NNPAS 2011–2012 collected dietary intake data of individuals through 24-h recalls on food and beverages consumed the day prior to the interviews. Interviews were administered by trained Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) interviewers over two separate days. The first day of 24-h recalls were conducted through face-to-face interviews with computer assistance (n 12 153). A second 24-h recall was conducted via telephone within eight days following the first 24-h recall (n 7735)(30). Both 24-h recalls adapted the Automated Multiple-Pass Method (AMPM) to maximise the recall of foods and further limit recall and memory bias. Specific details about the 24-h recall methods are described elsewhere(29).

Estimation of nutrient-level whole grain intakes

Estimation of whole grain intakes of survey participants utilised the Australian Food, Supplement and Nutrient Database (AUSNUT) 2011–2013(31). AUSNUT 2011–2013 is compiled of a set of files containing information on various nutrient contents within listed foods, however, whole grain gram values were not included. Therefore, we utilised an Australian whole grain database based on AUSNUT 2011–2013 previously developed by our group(Reference Dalton, Probst and Batterham32,Reference Galea, Dalton and Beck33) . AUSNUT 2011–2013 was designed specifically with a coding and classification system matched to the foods consumed within the NNPAS, and subsequently nutrient intake estimates of individuals could be calculated. Using the modified version of AUSNUT 2011–2013 with the whole grain values included allowed calculation of whole grain intake.

Whole grain intakes of survey participants were calculated based on four separate approaches surrounding application of the Healthgrain whole grain food definition to AUSNUT 2011–2013 foods. These approaches hereafter are referred collectively as whole grain food definition approaches and are described in Table 2, which includes approach 1: collation of total whole grain intake in grams (no whole grain food definition), 1a. including discretionary foods, 1b. excluding discretionary foods; and approach 2: applying the Healthgrain whole grain food definition, 2a. including discretionary foods and 2b. excluding discretionary foods. The Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011–2013 – Discretionary Food List(34) was used to identify foods within the AUSNUT database that are deemed discretionary. The Discretionary Food List used various principles to determine discretionary classification(35), including specification and/or inference in the 2013 Australian Dietary Guidelines and supporting documents whereby examples of discretionary foods are listed such as ‘most sweet biscuits, cakes, desserts and pastries’. Furthermore, additional criteria based on nutrient profiles were used to determine classification. For grain-based products, in particular, discretionary classification was given to breakfast cereals if sugar content was >30 g/100 g, or >35 g/100 g for breakfast cereals with added fruit. For mixed grain-based dishes, discretionary classification was given for those foods with saturated fat >5 g/100 g. Online Supplementary Material 1 outlines the methods used to determine compliance of AUSNUT foods with the Healthgrain whole grain food definition.

Table 2 Description of different whole grain food definition approaches applied in analysis to determine whole grain intakes

* The Healthgrain whole grain food definition refers to the recommendations for a whole grain food definition proposed by Ross et al. (2017).

† The Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide 2011–2013 – Discretionary Food List codes foods in AUSNUT 2011–2013 for discretionary or non-discretionary classification.

Whole grain intakes were initially calculated on a gram weight per day basis and further adjusted for daily energy intakes to grams per 10 MJ/d, to account for differences in total dietary intakes between age and sex(Reference Mann, Pearce and McKevith10) (online Supplementary Material 2 – Calculation 1). Whole grain intakes were then analysed for the total participants and further by sex and age for each of the four approaches. Age categories selected for analysis are based on age ranges established for the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs) for children, adolescents and adults(36). An additional analysis of whole grain intake by age was subsequently completed, combining multiple age groups to form the age categories, hereon referred to as children (2–18 years) and adults (19 years and over).

Multiple Source Method

For each whole grain food definition approach, usual dietary whole grain intake of participants was calculated using the Multiple Source Method (MSM) (Department of Epidemiology of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke (DIfE), 2008–2011), adjusting data from both 24 h recalls. The MSM estimates usual dietary intake of nutrients for populations and individuals using a three-step procedure. A more in-depth explanation of the methods behind MSM is discussed elsewhere(Reference Haubrock, Nothlings and Volatier37,38) .

Prior to analysis through MSM, whole grain intakes of each participant, on each day, were calculated for each whole grain food definition approach. This was achieved through analysis of the NNPAS 2011–2012 Basic Confidentialised Unit Record Files (CURF) data combined with data in the updated Australian whole grain database (see online Supplementary Material 2 – Calculation 2).

Calculated whole grain intakes for each participant, for each day, were run and analysed through MSM using explanatory variables ‘age’, ‘sex’ and ‘agesex’ (age × sex). A value of 0 was given to ‘specify a consumption probability from external source’ as consumption frequency was irrelevant for the purpose of the current study(38). Usual intake of all participants was used for further analysis. The entire process for MSM was repeated for each whole grain food definition approach.

Dietary energy values were required to compare values of whole grain intake relative to energy intake. Energy intakes for each participant, on each day, were calculated using the energy with fibre values given for each food consumed in the NNPAS Basic CURF dataset. Values were then adjusted through MSM using the same process as described above.

Reporting of food-level whole grain intake (Day 1 only)

Following the approach outlined in Barrett et al.(Reference Barrett, Probst and Beck39), whole grain intakes at the food level were investigated using unadjusted ‘day 1’ NNPAS food intake data. The MSM program was not utilised for this step due to an inability to calculate usual intakes of multiple food groups. To report whole grain intake at the food level, the percentage contribution of different food groups to total whole grain intakes was calculated using the 2-digit and 3-digit codes of foods consumed in the NNPAS, aligning with the major and sub-major food groups listed within AUSNUT 2011–2013 Food and Dietary Supplement Classification System(40). Two-digit codes represent foods at a category level (e.g. ‘cereals and cereal products’), while the 3-digit level further describes foods in these categories (e.g. ‘breakfast cereals, ready-to-eat’).

Initially, the gram intake of whole grains from any whole grain containing food (approach 1a) was separated into child and adult categories based on consumer age. The total whole grain intake from all participants of each category was then calculated. Foods were then sorted into their respective 2- and 3-digit codes, and total grams of whole grain consumed from each major and sub-major food group were summated. The percentage of total whole grain intake for each major and sub-major food group was separately calculated within each age group category. This process was then repeated for each whole grain food definition approach (approaches 1b, 2a and 2b) (online Supplementary Material 2 – Calculation 3).

Ethics

Ethics approval was not required as the current study was a secondary analysis of NNPAS 2011–2012 data. Accessibility and dissemination of the ABS Basic CURF data, obtained in the NNPAS, is governed by the Census and Statistics Act 1905(41), such that data must remain de-identified. Permission to use and analyse the data were obtained through approved registration at the ABS registration centre and through the University of Wollongong.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS statistics (Statistics version 21, 2009). Data used were positively skewed to the right; however, parametric tests were applied due to the large sample size (n 12 153). Statistical significance was determined at P < 0·05 for all analyses.

Median whole grain intakes were determined using the MSM adjusted data of both gram per day and energy adjusted intakes for each of the whole grain food definition approaches. Median and interquartile ranges of intakes were determined for the total participants and further by sex, age and combined sex and age categories. There were ten age categories consisting of 2–3, 4–8, 9–13, 14–18, 19–30, 31–50, 51–70, >70, 2–18 years (children) and 19 years and over (adults).

Paired samples t test was used to determine if there were significant differences in whole grain intakes between whole grain food definition approaches, but within the same participant categories. For example, intakes of males 2–3 years when no whole grain food definition was applied (including discretionary) were compared with intakes of males 2–3 years when applying a whole grain food definition (including discretionary).

Results

Compliance of AUSNUT foods

Following expansion of the whole grain database, 214 of the 609 foods containing any amount of whole grain were compliant with the Healthgrain definition. Online Supplementary Material 1 outlines results in greater detail.

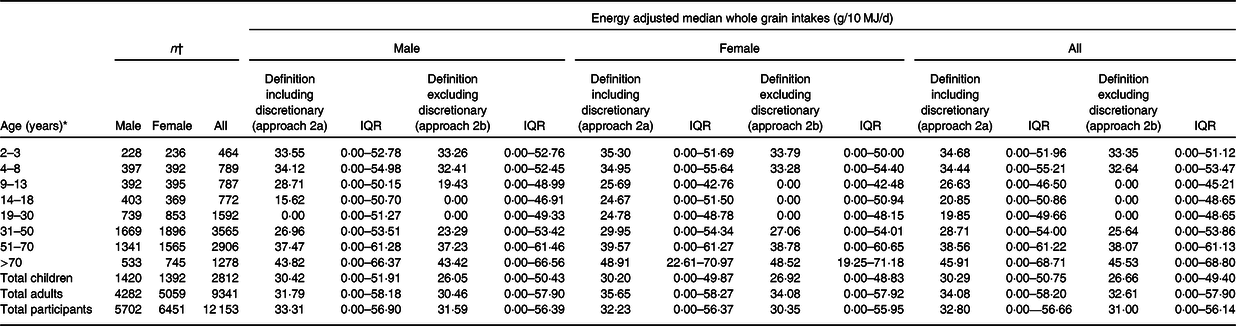

Median whole grain intakes

Median whole grain intakes of children and adults varied greatly between the whole grain food definition approaches. As expected, the highest whole grain intakes are observed for both children and adults when no whole grain food definition was applied and discretionary foods were included in analysis (approach 1a) (Tables 3 and 4). Lowest whole grain intakes were observed when discretionary foods were excluded with application of a whole grain food definition (approach 2b) (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 3 Median whole grain intakes (g/d) for separate participant categories when no whole grain food definition is applied (approach 1)

* Age categories are those established within the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRV). Children are defined as 2–18 year old and adults are defined as 19 year old and over.

† The number of participants refers to the number of individuals that are within that category from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–2012.

Table 4 Energy adjusted median whole grain intakes (g/10 MJ/d) for separate participant categories when no whole grain food definition is applied (approach 1)

* Age categories are those established within the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRV). Children are defined as 2–18 year old and adults are defined as 19 year old and over.

† The number of participants refers to the number of individuals that are within that category from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–2012.

Table 5 Median whole grain intakes (g/d) for separate participant categories when applying the Healthgrain whole grain food definition (approach 2)

* Age categories are those established within the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRV). Children are defined as 2–18 year old and adults are defined as 19 year old and over.

† The number of participants refers to the number of individuals that are within that category from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–2012.

Table 6 Energy adjusted median whole grain intakes (g/10 MJ/d) for separate participant categories when applying the Healthgrain whole grain food definition (approach 2)

* Age categories are those established within the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRV). Children are defined as 2–18 year old and adults are defined as 19 year old and over.

† The number of participants refers to the number of individuals that are within that category from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey (NNPAS) 2011–2012.

Across all whole grain food definition approaches, whole grain intakes, including energy adjusted intakes, were highest among those >70 years old. The lowest whole grain intake group varied between the different whole grain food definition approaches and furthermore when adjusting for total energy intake. Lowest whole grain intakes, when adjusted for energy, were seen in the 14–18-year age group for approaches 1a and 1 b (Table 4), the 19–30-year age group for approach 2a (Table 6) and the 9–13, 14–18 and 19–30-year age group were equally lowest for approach 2b (Table 6). This implies that adolescents aged 14–18 years generally had a low intake of whole grains. This group and the 9–13-year age group consumed more of their relative intake of whole grains from discretionary foods, and 19–30-year-olds consumed whole grains from foods that do not comply with the Healthgrain definition, namely, those containing significant refined grains. There were minimal differences in energy adjusted whole grain intakes between males and females among each of the whole grain food definition approaches.

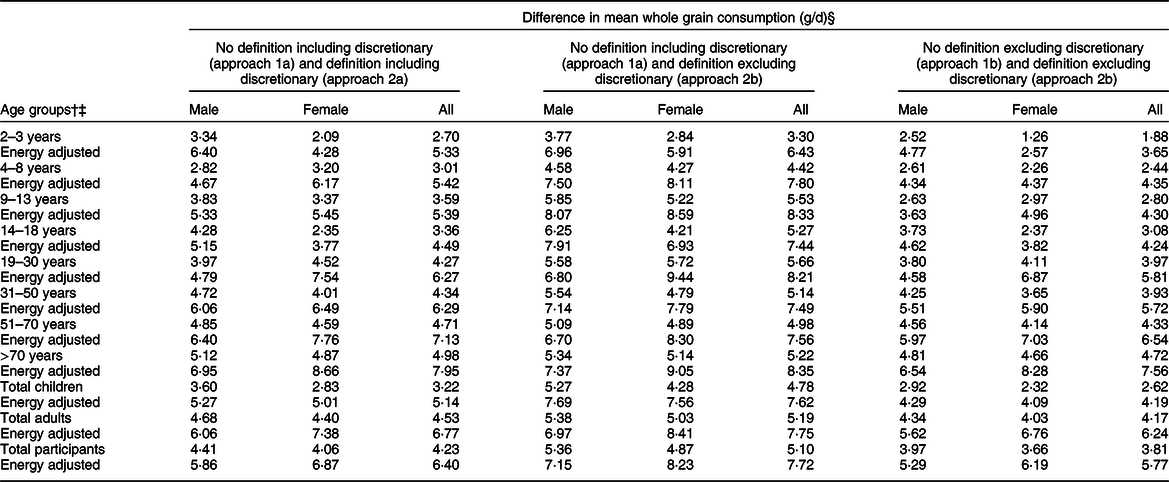

Comparison of whole grain intakes between whole grain food definition approaches

Statistically significant differences (P < 0·05) exist between whole grain intake values of different whole grain food definition approaches within all participant categories (Table 7). The difference in mean whole grain intake ranged from 2·09 to 5·12 g/d (3·77–8·66 g/10 MJ/d) across participant categories when comparing approach 1a to approach 2a (Table 7). Mean difference in whole grain intakes when comparing approach 1a to approach 2b and approach 1b to approach 2b ranged from 2·84 to 6·25 g/d (5·91–9·44 g/10 MJ/d) and 1·26–4·81 g/d (2·57–8·28 g/10 MJ/d) across participant categories, respectively.

Table 7 Difference in mean whole grain intake between different whole grain food definition approaches*

* There is a statistically significant difference among all comparisons (P < 0·05).

† Age groups by years are in line with those within the Australia and New Zealand Nutrient Reference Values (NRVs).

‡ Age groups by children and adult are defined as children = 2–18 years and adult = 19 year old and over.

§ Difference in means obtained through paired samples t test (t test for equality of means).

Food sources of whole grain intakes (Day 1 only)

Calculating the percentage of total whole grain intake of major and sub-major food groups for both children and adults found that, for all whole grain food definition approaches, the highest percentage of whole grain intakes was from the ‘cereals and cereal products’ major food group. The total intake percentage for this food group was mostly higher for adults in comparison with children within the same whole grain food definition approach, with the exception of approach 2b (Table 8 and online Supplemental Tables S4 and S5).

Table 8 Percentages of total whole grain intakes for major food groups from each whole grain food definition approach

* Major food groups are those described in AUSNUT 2011–2013 Food and Dietary Supplement Classification System using the 2-digit food code.

† Children = 2–18 year old.

‡ Adult = 19 year old and over.

When comparing total percentage intakes across the whole grain food definition approaches, there were major differences in the ‘cereal and cereal products’, ‘snack foods’ and ‘confectionary and cereal/nut/fruit/seed bars’ major food groups for both children and adults (Table 8). These differences can be attributed to the exclusion of whole grain within specific foods when applying the Healthgrain definition, particularly discretionary items including corn chips, popcorn and muesli or cereal style bars. In terms of relative percentage contribution, this is most relevant in children who gain almost 10 % of their total whole grain intake from these discretionary items.

Discussion

The current study identifies two key findings within the research of grains and the translation of messages around whole grain intakes. First, these results suggest that the way in which whole grain intakes are calculated provides significant variation in measured whole grain intake, with potential relevance to investigating associated health benefits. Second, specific types of foods containing whole grains may be excluded from intake calculations due to other components such as refined grains or having higher sugar, saturated fat or sodium content, yet it is difficult to truly ascertain if these potentially deleterious components negate the effect of the whole grain within the food. Both these considerations have the potential to affect how organisations and individual health professionals promote increases in whole grain intake.

Current research suggests that utilising a unified whole grain food definition will have positive outcomes in whole grain promotion and subsequently in increasing population whole grain intakes, such that it may influence whole grain product labelling and further assist consumers to choose healthier and higher whole grain content products(Reference Ferruzzi, Jonnalagadda and Liu21,Reference Ross, van der Kamp and King28) . However, acceptance of a whole grain food definition by consumers and their organisations is essential to achieve adequate whole grain promotion. On the contrary, there are potential implications when applying a definition in research investigating the impacts of whole grain intakes on health. Here, and elsewhere(Reference Ferruzzi, Jonnalagadda and Liu21), whole grain containing food products that do not comply with the whole grain food definition and are excluded from analysis may still contribute to an individual’s whole grain intake. Failure to account for these products can significantly impact calculated whole grain intakes, and therefore impact study outcomes using this data, specifically affecting the observed associations with health outcomes(Reference Ferruzzi, Jonnalagadda and Liu21).

Similarly to our work, a study by Mann et al.(Reference Mann, Pearce and McKevith10) on UK data found that whole grain intakes were lower when applying different criteria to define whole grain foods, such that a ≥10 % and a ≥51 % whole grain proportion cut-off was applied in comparison with absolute whole grain intakes. Similarly, another study recognised that applying various criteria to define whole grain foods has the ability to underestimate whole grain intakes of populations, especially utilising definitions whereby foods must contain a high proportion of whole grains(Reference Thane, Jones and Stephan42). Thus, if the Healthgrain whole grain food definition is to be applied and utilised in future research, we, as an international community, must acknowledge and further recognise that values given do not truly reflect individual and population whole grain intakes. It is evident in the present study that applying a whole grain food definition, especially incorporating discretionary food exclusion, create differences in reported whole grain intake values of potential clinical relevance.

In general, exclusion of discretionary foods from the current analysis, whether a whole grain food definition is applied or not, caused reductions in whole grain intake values, which was most evident among the older children and adolescent age groups. This is likely due to greater discretionary food intakes in general, with current research in the Australian context highlighting discretionary food consumption is highest among the 14–18-year age group(43). Furthermore, the proportion of energy from discretionary foods is shown to decrease in the 19–30-year age group and older(43). These differences are related to a multitude of factors, however, can be associated with specific lifestyle factors and other influences surrounding individuals at specific life stages(Reference Story, Neumark-sztainer and French44). The high prevalence of discretionary food consumption has negative consequences on calculated whole grain intake. Due to a higher demand, manufacturers are more inclined to add whole grains to these food items, potentially improving their healthful properties. However, it may be less than ideal to encourage a discretionary food, regardless of whole grain content, particularly if it is a small amount.

In the current study, a number of whole grain containing foods excluded due to non-compliance with the definition contained substantial amounts of whole grain. From the current analysis, it is clear in approaches where a whole grain food definition is applied, the percentages of total whole grain intake shows little to no whole grains being consumed from major food groups other than the ‘Cereals and cereal products’ or ‘Cereal based products and dishes’ major food groups. However, a larger variation of whole grain food sources are shown where no whole grain food definition was applied, thus illustrating impact on the distribution of total whole grain intake food sources, when a whole grain food definition is applied.

Moreover, as shown through intake comparisons, decreases of up to 8 g of whole grain (energy adjusted) were found when applying the Healthgrain definition. Eight grams is considered half a whole grain serve and is potentially of clinical relevance. Studies have found that one single whole grain serving (16 g) can reduce fasting insulin concentrations by 6·3 %(Reference Liese, Roach and Sparks45) and reduce weight gain(Reference Bazzano, Song and Bubes46). Additionally, one whole grain food serving (30 g with around 16 g whole grain) has been reported to reduce all-cause mortality by 7 % and CVD-specific mortality by 8 %(Reference Li, Zhang and Tan47). The undercalculating related to application of food definitions is therefore a key consideration for future work.

Limitations here relate to the data sources used for analysis with the retrospective analysis of the NNPAS 2011–2012 unable to represent the ‘current’ whole grain consumption of Australians. The current analysis did not apply replicate weights to account for the sampling design of the Australian Health Survey. While appropriate given this is a methodological study exploring the impact of different whole grain definitions, caution should be applied when generalising these findings to national whole grain intakes. Additionally, since collection of the NNPAS data, there has been an increase in whole grain products introduced into the Australian market, including development of new products and enrichment of existing products, while some whole grain products have been removed(Reference Franz and Sampson48) introducing further potential error. This is however the most recent and comprehensive dataset available for Australian intake data and, especially as this is a comparative methods study, can be used as guidance to provide a general estimation of whole grain intakes among individuals.

In the current study, whole grain intakes were calculated based on inclusion of all participants, regardless if they were a whole grain consumer or non-consumer. Although these intake values provide an overview of whole grain consumption among survey participants, they may not hold relevance when conducting further analysis or comparisons due to estimation based on large proportions of non-consumers. While it may have been beneficial, in the current study, to conduct separate analysis on consumers only, a study by Galea et al. (2017)(Reference Galea, Beck and Probst9) has previously analysed consumer only whole grain intakes using the same NNPAS dietary intake data. It was found almost 30 % of all participants were non-consumers of whole grains, such that median whole grain intake in adults increased by 17 g/d when analysing consumers only. This provides an adequate indication for the percentage of whole grain consumers and non-consumers in the Australian context; however, methods used to calculate whole grain intake differ slightly to the present study.

Additionally, findings from the study cannot be implied internationally since dietary intake data vary from country to country, as does the food available to consumers and their composition. However, the methods used in the current study may provide guidance for future studies and may act as a comparative study to the present research.

Assumptions in the whole grain food database, regarding food compliance with the Healthgrain definition, are underlying throughout intake calculations and have the potential to over or underestimate whole grain intake values. The data within the whole grain database may also not reflect true whole grain composition of foods as values are derived from ingredient labels, estimated recipes and data obtained elsewhere. Therefore, variations within the same product and changes in formulations cannot be accounted for and may alter total whole grain intake values. Nonetheless, the limitations present within this current study are similar to those within other studies alike(Reference Galea, Beck and Probst9–Reference Bellisle, Hebel and Colin11,Reference Devlin, McNulty and Gibney49) .

It is evident that application of a whole grain food definition, namely, the definition proposed by the Healthgrain Forum, has potentially significant impacts on measurement of whole grain intakes of individuals and populations. While application of a whole grain food definition may prove beneficial within settings such as whole grain promotion, where individuals will understand to eat more of a food rather than to eat ‘x more grams of whole grain’, future research must also investigate the potential implications this has among other settings, namely, the associations between whole grain intakes and health outcomes. The two settings are different, and careful differentiation is essential in both whole grain health research and whole grain promotion.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank S.G. for guidance surrounding whole grain food products and definitions in the Australian context and E.B. for assistance with multiple source method (MSM) data analysis. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: K.R.K. and E.J.B. formulated the research question; K.R.K. and E.J.B. designed the study; K.R.K. conducted research; K.R.K. and E.P.N. analysed data; K.R.K., E.P.N. and E.J.B. wrote the article; K.R.K. had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethics approval was not required for this current study. Accessibility and dissemination of data in the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Basic Confidentialised Unit Record Files (CURF) is governed by the Census and Statistics Act 1905, such that data must remain de-identified. Permission to use and analyse the data were obtained through approved registration at the ABS registration centre and through the University of Wollongong.

Census and Statistics Act available at: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C01005

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004452