Healthy eating is essential for the growth and development of children and youth. The diets of many Canadian children and adolescents are characterized by low intakes from the nutrient-dense food groups of Canada's Food Guide, high intakes of energy-dense/nutrient-poor foods and suboptimal food patterns, including breakfast skipping( Reference Garriguet 1 – Reference Phillips, Jacobs Starkey and Gray-Donald 7 ). Breakfast skipping has been linked to other poor nutrition habits, such as increased unhealthy snacking and lower consumption of grain, fruit and milk products( Reference Dubois, Girard and Potvin-Kent 5 , Reference Hooper and Evers 8 ). Students who regularly skip breakfast are at increased risk for high BMI scores, which can lead to overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular health issues and other nutrition-related chronic diseases( Reference Dubois, Girard and Potvin-Kent 5 , Reference Roblin 9 ). Also, research has shown that hunger has an impact on academic performance and behaviour( Reference Grantham-McGregor 10 , Reference Pollit 11 ). Teachers have reported increased tardiness/absence, more behavioural problems and lack of concentration for students who do not consume breakfast( Reference Pollit 11 , Reference Matthys, De Henauw and Bellemans 12 ).

Schools have long been recognized as an important setting for public health intervention( 13 , 14 ). The Comprehensive School Health Framework suggests that the whole school environment (including teaching and learning, social and physical environments, school programmes and policy, partnerships and services) can support improvements in learning and health behaviour in children and youth( 15 , 16 ). Additionally, both the Ontario Healthy Schools Coalition and the Ontario Society of Nutrition Professionals in Public Health School Nutrition Working Group( 14 ) highlight the importance of a healthy school nutrition environment within a comprehensive school health promotion framework. School nutrition programmes (SNP) are one avenue to help students access nutritious foods throughout the day. Two non-profit, non-governmental organizations (Canadian Living Foundation and Breakfast for Learning) initiated support for such programmes in Canada. Now more than 1800 community-based programmes have been created throughout Canada( 17 ). Providing universal access to SNP can ensure that children at risk for poor nutrient intake have access to safe and healthy foods( Reference Leo 18 , Reference Crepinsek, Singh and Bernstein 19 ). Research has shown that programmes with universal access v. access targeted to high-risk groups had higher participation rates( Reference Crepinsek, Singh and Bernstein 19 , Reference Bernstein, McLaughlin and Crepinsek 20 ), less breakfast skipping and showed normalization of breakfast eating, therefore minimizing student concerns about weight( Reference Reddan, Wahlstrom and Reicks 21 ). Allowing universal programmes has also been shown to reduce stigma associated with selective nutrition programmes where only those of low income could participate( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 , Reference Russell 23 ). Universal programmes therefore promote school connectedness and a whole-school approach where everyone in the school, including students, staff, parents and the community, is involved( Reference Rowe and Stewart 24 , Reference Rowe, Stewart and Somerset 25 ). There has been tremendous proliferation of SNP in Canada, yet little is known about ‘what works’ within these diverse, largely volunteer-led programmes. Moreover, the current and potential role of public health is unexplored. One SNP evaluation, the Ontario Child Nutrition Program Evaluation Project (OCNPEP), was completed in 2005( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 ). It developed seven ‘best practice’ guidelines that included: (i) access and participation; (ii) parental involvement, consent, partnerships and collaboration; (iii) inclusive and efficient programme management; (iv) food quality; (v) safety; (vi) financial accountability; and (vii) evaluation( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 ). These guidelines served as a framework for the current study( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 , Reference Russell 23 ). The current research evaluated an Ontario region's SNP from the programme coordinators’ perceptions.

Setting the scene

Public health in Ontario

There are thirty-six public health units in Ontario, Canada( 26 ). Their role includes administering health promotion/disease prevention programmes for a specific geographic area within Ontario. A board of health ensures that each public health unit follows the 2008 Ontario Public Health Standards set by the Ministry of Health and Long term Care( Reference Valaitis, Ehrlich and O'Mara 27 ).

The role of public health in school nutrition programmes

The Ontario Public Health Standards direct public health units to collaborate with school boards and schools ‘to influence the development and implementation of healthy policies, and the creation or enhancement of supportive environments’ as part of a comprehensive health model including promotion of healthy eating( 28 ). In Ontario, public health staff, including dietitians, dental health professionals, public health inspectors, health promoters, nurses and epidemiologists, have been linked to individual schools to promote these goals. With respect to the current study, the regional public health department provides in-kind staff support to SNP. Health inspectors provide and/or develop food safety training and inspect local programme sites. Regional public health dietitians support SNP and the SNP coordinators by developing and implementing training regarding Ministry of Child and Youth Service Nutrition Guidelines, menu planning, food procurement and food safety. School health nurses work within a comprehensive school health framework and may recommend that schools initiate an SNP or assist dietitians in programme support.

The term ‘public health’ in the present paper refers to regional public health professionals who work with schools to help promote a healthy schools approach.

The region's school nutrition programmes

The study was conducted in a large, ethnically diverse, urban region in Ontario, Canada. In 2011, the population was 1 300 000( 29 ). In 2006, 561 000 were new immigrants to Canada, representing approximately 48 % of the region. Twenty per cent of the region's population was living below the Low Income Cut-Off( 30 ). According to 2004 Canadian statistics, almost 30 % of those with the lowest incomes were considered severely food insecure( Reference Friendly 31 ). Across the two school boards in the region, 322 elementary schools and fifty-eight secondary schools existed at the time of the study.

The region's SNP are voluntary and operate separately from the Ministry of Education. They provide breakfast, lunch and/or snack programmes within approximately 170 of the region's elementary or secondary schools and a few community centres. The Ministry of Child and Youth Services is the primary funder of the programmes, although independent fundraising is also needed to support programmes. Individual schools apply for programme funding annually. A regional SNP director distributes the Ministry's funding to individual schools and also provides some in-kind support. School SNP coordinators are often teachers in the school. Programme coordinators are responsible for planning and purchasing food and supplies and seeking out additional community partnerships for monetary or in-kind support. Each school runs its own SNP somewhat independently to meet the specific needs of the school.

The school food environment

While the USA and Britain have developed standards specific to nutrition programmes, Canada remains one of the few developed countries without a national school nutrition policy for SNP( Reference Gougeon 32 ). Currently, there also is no pan-Canadian publicly subsidized SNP. Ontario's Ministry of Children and Youth Services provides suggested nutrition guidelines for programmes; however, each province's nutrition criteria differ and many provinces still sell nutrient-poor foods or do not meet limits on fat, salt and sugar. In 2011, Ontario's Ministry of Education implemented a school food and beverage policy (P/PM 150) affecting all schools( 33 ). However, the policy only affects foods that are sold to students on school premises. It is more common for secondary schools to have cafeterias, compared with elementary schools; although elementary schools often have special lunch days (pizza days, hot dog days, milk programmes, etc.). Parents are required to pay for these special lunches, while SNP often remain free of charge.

Objectives

The purpose of the present research was to better understand the design and implementation of SNP within a large multi-ethnic region of Ontario and to explore current and potential collaboration between regional public health professionals and SNP. Specific study objectives were to determine programme coordinators’ perceptions of:

-

1. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) associated with their SNP in relation to the following OCNPEP components( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 , Reference Russell 23 );

-

a. access and participation

-

b. parental involvement and consent

-

c. partnerships and collaboration

-

d. inclusive and efficient programme management

-

e. food quality and safety

-

f. financial accountability

-

g. evaluation.

-

-

2. Ways that local public health professionals could support and enhance SNP.

Methods

The evaluation used a sequential mixed-methods approach. The first component involved an online survey distributed to all SNP that had been initiated prior to the previous (2009) school year (n 81). The survey had a response rate of 76 % (n 62). It obtained background information about the programmes and organizations running them, programme organization, and foods and services offered. The second component, which is the focus of the current paper, utilized a qualitative approach consisting of interviews with a sample of programme coordinators responsible for delivering individual SNP. Programme coordinators who had completed the survey and expressed willingness to participate in interviews were contacted by email; all twenty-two agreed to participate in an interview. These coordinators represented each school level (i.e. primary, middle and secondary) and school board (see Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of school nutrition programme (SNP) coordinators in the region and of SNP coordinators who were interviewed; large, ethnically diverse, urban region of Ontario, Canada, 2010

Study participants

All twenty-two programme coordinators who participated in interviews were teachers or staff, many of whom had started the SNP within their school, although some coordinators had taken over the programme from other staff. Many of the coordinators ran the programme independently; however, they often received help from either students or other teachers/staff. None of the coordinators had paid positions. The majority of the programmes were breakfast-only (n 14). One offered a snack-only programme, whereas the others had a combination of programme types (breakfast and lunch, for example). The programmes varied; some reported cooking warm meals, while others delivered snacks to classrooms. Eleven of the coordinators reported attending food safety training offered by the programme funders but did not necessarily have any formal training.

Interview method and analysis

Interviews were conducted to validate and expand on survey results( Reference Creswell and Plano Clark 34 ). One hour, semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face, in a quiet room in the school, by the first author. Specifically, coordinator interviews followed a SWOT framework and obtained in-depth information regarding programme strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats( Reference Pickton and Wright 35 ). At the end of the interview, following spontaneous responses, the OCNPEP best practice guidelines were shown to participants to ensure that reflections relating to all of these best practice guidelines were covered. The interview concluded with questions relating to programme needs and support (specifically potential public health support), which were not themes identified by the OCNPEP but were of interest to the research advisory committee.

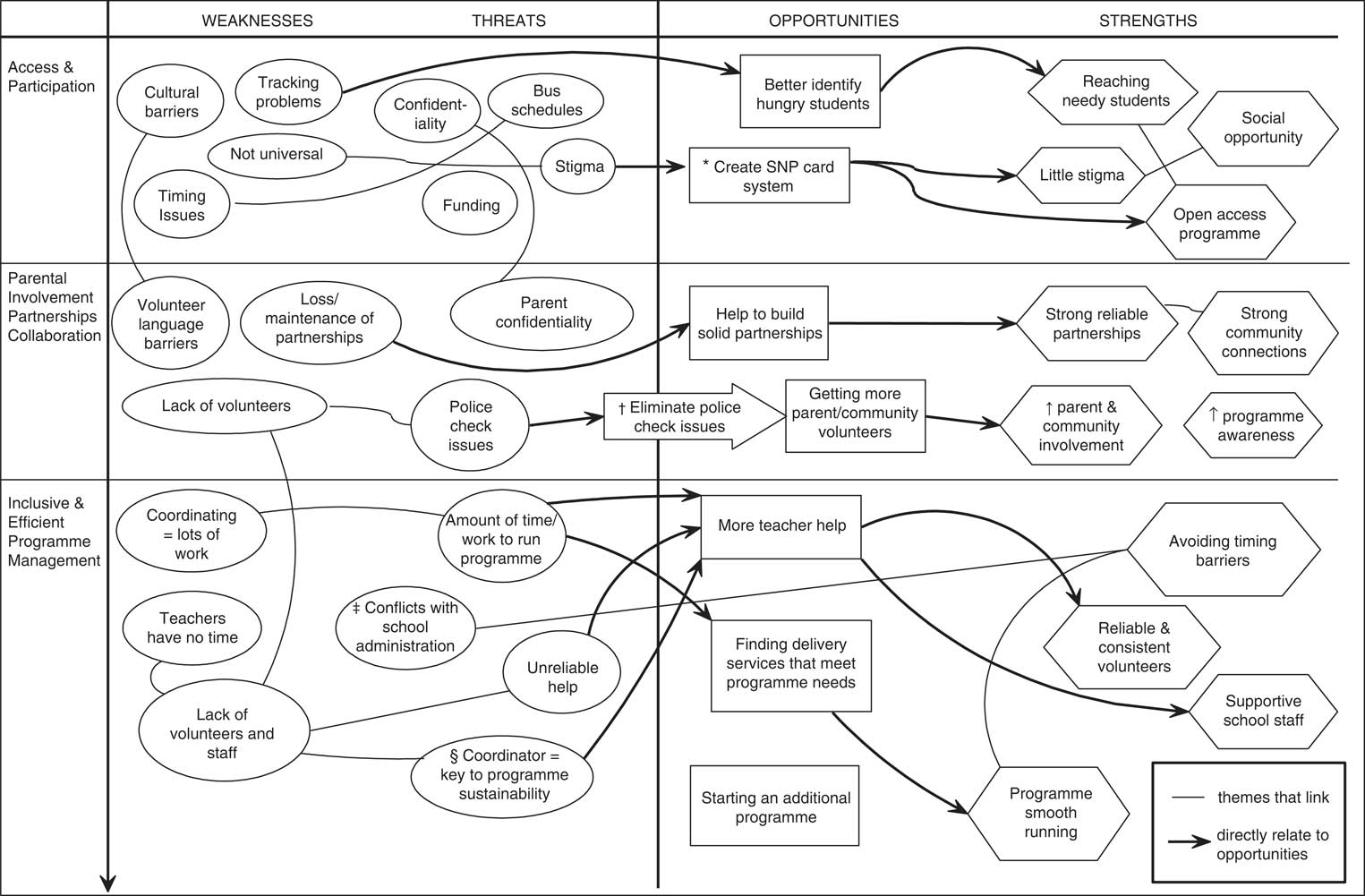

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using NVivo8 qualitative software. The first author coded the interviews into common themes, using first level coding where items were first identified, followed by pattern coding, where the items were grouped and summarized into theme sets and constructs( Reference Patton 36 , Reference Miles and Huberman 37 ). For the analysis, a SWOT matrix was used which included the concepts outlined in the OCNPEP best practice guidelines as well as any new concepts that emerged( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 ). This helped structure and organize the analysis. Figure 1 illustrates this matrix along with common findings from the interviews. A second qualitative methods expert reviewed the codebook and a sample of transcripts to increase reliability( Reference Patton 36 , Reference Miles and Huberman 37 ). The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Research Committees of Public and Catholic school boards and the University's Office of Research Ethics. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Fig. 1 Relationships among themes identified by twenty-two school nutrition programme (SNP) coordinators, according to OCNPEP (Ontario Child Nutrition Program Evaluation Project) component and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) matrix, from a large, ethnically diverse, urban region of Ontario, Canada, 2010. * Used for programmes which are not universally free. An SNP stamp card is used for programme access: students who can afford it, pay for the card; those who cannot are privately given a free card by staff, ensuring confidentiality and eliminating stigma. † Difficult process to become a volunteer – police check takes a long time to process, there are too many steps and parents are discouraged from volunteering. ‡ Administration has issues with programme – teachers not allowing food in classrooms, students eating in hallways, custodial staff complaining of untidiness. § Coordinators feel that if they left the programme/school, no one would take over it and the programme would end. || Coordinators would like a programme-specific credit card to track programme purchases and expenses. ¶ A support network could be created that includes an online sharing forum or blog where coordinators could share stories, post questions and comments to aid them in programme implementation

Fig. 1 continued.

Findings

Of the sixty-two survey respondents, thirty-nine coordinators agreed to participate in an interview; however, in the end, twenty-two coordinators actually followed through with the interview. Interviewees came from a representative cross-section of all SNP in the region (Table 1).

Coordinators provided a general description of their programme. All but one programme offered was a universal programme, meaning that all students of the school were able to participate. All programmes were free of charge and offered breakfast, snack and/or lunch served in a variety of ways: hot food, cold food or food baskets. While most coordinators offered their programme every day, a few that were lacking in support or resources were only able to serve 2 or 3 d/week. From five to 150 students attended breakfast programmes (most serving twenty-five to fifty students), while lunch programmes had similar attendance, but could reach up to 250 students. The programmes offered a wide variety of foods such as eggs, toast, bagels, cereal, applesauce, yoghurt, granola bars, pizza, salads and wraps. Many schools were located in low-income areas. Eight coordinators reported high diversity in their school in relation to ethnicity, comfort with English and apparent socio-economic status.

The following results illustrate the most common strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats discussed by programme coordinators. All of the OCNPEP components were addressed in the interviews, with the exception of evaluation, where none of the coordinators reported having any formal evaluation component to their programme.

Strengths

Overall, reported programme strengths included: (i) universality; (ii) the ability to reach hungry students; (iii) providing a social opportunity for the entire school population; (iv) having supportive school staff; (v) offering variety in foods; and (vi) having an overall positive impact on students themselves. Almost all programmes were universally available to all students and coordinators felt that their programme reached students who needed it most. Coordinators felt programmes were openly accessible and inviting to students. Some incorporated the social aspect intentionally by encouraging teachers and other school staff to eat with students. Having supportive school staff was perceived as essential by many coordinators. Indeed, many coordinators felt that their programmes would not run without reliable staff volunteers. Also, coordinators felt that the variety of food options provided was a significant strength of their programme. Some were able to offer ethnically diverse foods to students; for instance, a coordinator explained: ‘yesterday [we served] vegetable curry with rice, and, next Tuesday we are having samosas and pulal, and the volunteers make it…’. A few programmes had students shop for, prepare and cook food themselves. Finally, many coordinators reported that they saw the benefits of these programmes on students’ academic, behavioural and social development.

Weaknesses

While many common strengths were reported by coordinators, not all had similar experiences; often one programme's strength was another's weakness. For example, while some programmes offered large variety in foods, other coordinators reported food variety to be a major weakness. Many schools struggled with what to serve without proper facilities for food preparation. Also, some admitted not serving the healthiest options because of food cost, uncertainty about nutrition guidelines and reading food labels. For instance, many found it challenging to find affordable foods while making sense of their nutritional value to ensure they met the guidelines, granola bars being a common example. Also, programmes that sent bins into classrooms were very limited in variety since they were restricted to non-perishable foods. Some felt that students’ cultural and religious restrictions were a challenge. Another common weakness was programme timing. Many parents brought their children late, or bus and programme schedules clashed, influencing student participation.

A major weakness was partnerships with stores or community organizations for monetary or in-kind support. A few coordinators reported this as a major strength; however, many struggled to find or maintain these links. Some potential funders had limited capacity to take on more schools than those they were already funding; new management often cancelled existing partnerships; coordinators would not hear back from new potential partners. Coordinators would get frustrated struggling to keep these partnerships, which led to another weakness: the time and work associated with coordinating the programme. As a result of the lack of volunteers, excessive paperwork, problems with food delivery services and issues with community partnerships, coordinator workload became overwhelming.

Opportunities

Coordinators commented on potential opportunities they saw for their programme. Of those who offered their programme twice weekly, or offered only one type of meal, many would welcome the opportunity to expand either the type of meals served or the frequency. Some felt there was potential for greater student participation and school staff support. Other opportunities included building stronger partnerships and community connections. Many were not able to use food delivery services because of order restrictions on low quantities. One coordinator explained: ‘one company … wanted a minimum of $600 a month … but a lot of that stuff is fresh and we couldn't wait a whole month and wait for another delivery’. Increasing food variety was another way they felt they could expand their programme. Many reported that they would prefer to serve something different every day, rather than the standard menu.

Threats

Finally, coordinators were asked about potential threats to programme sustainability. The most common threat was funding. Also coordinators expressed concern that if they left the school, no one would replace them and the programme would cease. Another threat was potential stigma for students using the programme. While almost all programmes were universally available, some were not. Programmes that were mainly directed to at-risk students reported stigma. Another threat was unreliable and inconsistent help from school staff or parent volunteers. Some also reported conflicts with school administration. For example, many teachers did not allow students to eat in class and coordinators had a hard time finding space for students that was acceptable to school staff, including teachers and custodians. Another threat was catering to food allergies and religious/cultural food restrictions. Also, some reported issues with school facilities and therefore potential problems with food safety.

Public health involvement

Coordinators reported receiving assistance from health units with funding, application preparation, provision of food and ordering services, and general advice. Ten programmes (16 %) reported receiving enough support, through funding, volunteers, partnerships, food safety training and/or menu planning assistance. Paradoxically, a disconnection became apparent in the survey findings where many coordinators without current public health support also reported not wanting support. A few explained that they would only need more support if they wanted to expand the programme. Other coordinators reported enough support in some areas but not others. For those wanting more support, the majority sought help choosing foods such as: recommendations for bins; menu ideas; and healthy selections. A few wanted more information to ensure they were meeting standards.

Because of the disconnection in the survey findings, we asked coordinators during the interview to explain why coordinators would or would not want support from public health. For those not wanting support, many felt they were already comfortable with food safety as the standards rarely changed. Also, those offering basic programmes felt they needed no additional training. One coordinator explained: ‘…to put granola bars out and juice boxes, I don't think I need to go to food safety training. If we were providing meals, absolutely’. Others expressed confusion about the type of support available from public health. The most common explanation for not wanting food safety training was fear of inspection. Six coordinators expressed concern about not following all guidelines as well as fear that public health would close their programme or force unrealistic changes.

Every coordinator had a different need for support; therefore, health units need to offer multiple strategies and methods of support. Public health professionals need to reduce concerns regarding inspection. Table 2 provides suggestions for health unit support for SNP.

Table 2 School nutrition programme (SNP) coordinators’ recommendations for public health support of SNP; large, ethnically diverse, urban region of Ontario, Canada, 2010

Discussion

The current study highlighted the diversity of SNP offered within a large urban region in Ontario. Although there were many weaknesses in current programmes and threats to their sustainability, the study also identified numerous strengths and opportunities to expand upon strengths. For example, many coordinators felt the programme had positive academic and social impacts on students. Literature on school meal programmes also suggests that the school food environment has social and academic benefits for students, which can impact students’ eating habits( 38 , Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald 39 ). Also, coordinators felt that a strength of their universal programmes was increased reach to students in need. This is supported by research suggesting that the routine nature and universality of programmes increases participation( Reference Reddan, Wahlstrom and Reicks 21 , Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 ). This is important in a region where income disparities are a concern( Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O'Brien 40 ). The OCNPEP evaluation led to the recommendation that programmes be offered on three to five days per week. This supports the desire for expansion of coordinators in the current study who only offered their programmes once or twice per week.

The importance of community partnerships emerged as a strength, weakness and opportunity. A recommendation in the OCNPEP was to create programme committees to help establish collaborations( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 , Reference Russell 23 ); however, no coordinator had such a committee. Public health could provide community development support to coordinators by identifying and linking schools with potential collaborating partners. In addition, coordinators of smaller programmes experience issues with delivery services that have minimum spending limits. This issue has not been described elsewhere. However, bulk purchase and delivery for multiple programmes within a region could eliminate this problem and minimize coordinators’ workload.

Some coordinators found they did not have the background, time or infrastructure to effectively accommodate students’ cultural, religious or allergy-related dietary restrictions. Literature addresses the importance of language services to cater to ESL (English as a second language) families( 41 ) but does not explicitly discuss other allergies and religious dietary restrictions. This is a potential area for public health and dietitian support.

Ontario guidelines talk of the importance of dietitian and public health involvement, especially regarding food safety and healthy menu planning. Nevertheless, some coordinators seemed opposed to public health involvement. Public health needs to allay fear of inspection and lack of awareness of services. Access to public health support would be facilitated by flexibility in timing and training venue.

Overall, these SNP provide a significant contribution to a comprehensive health-promoting schools framework( 14 ). For instance, Rowe and Stewart( Reference Rowe and Stewart 24 ) discuss the importance of connectedness within a school setting, promoting interactions between members of the school community( Reference Rowe and Stewart 24 , Reference Rowe, Stewart and Somerset 25 ). The social opportunity these programmes create not only for students, but also for other school staff and community members, is therefore a strong example of school connectedness. This is also supported by the partnerships that the coordinators create outside the school community. One of the pillars of the Comprehensive School Health Model is ‘Partnerships and Services’( 14 , 15 ). It was also an OCNPEP best practice standard( Reference Russell, Evers and Dwyer 22 ). These programmes can facilitate building connections not only through community in-kind support, but also through parental involvement in programmes. While some schools found this to be a major strength, others struggled to build these connections. It is clear that further support in this area is essential to building a comprehensive school environment.

Comprehensive school health models also describe the importance of education alongside a supportive learning environment( Reference Keshavarz, Nutbeam and Rowling 42 ). Many of these coordinators saw nutrition education as an area for improvement within their schools, which provides another opportunity for public health to get involved.

Conclusion

School and community nutrition programmes play a vital role in the academic, behavioural and social well-being of students. The school food environment impacts both students and families and these programmes can help ensure that students have access to nutritious food daily. The current study highlighted the diversity of programmes in a large urban region and their respective strengths and challenges. Clearly there is an important role for public health professionals’ support. Multiple strategies may be needed to best support menu planning, identifying healthy food options, food safety training, or helping build partnerships within the community for food purchase or sponsorship. Forging ties between strong public health and SNP is an important first step.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The study was supported by the Boys and Girls Club of Peel Region and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contributions: R.F.V. coordinated and conducted the research, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; R.M.H. supervised the research, provided guidance in writing the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript; I.S.H. provided guidance throughout the research study, assisted in the creation of recommendations emerging from the research and reviewed the manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge their advisory committee, Sharon Harper and Debbie Smith, as well as the study participants for all their support through the research.