Over the last decades, the production of organic foods has rapidly increased worldwide(1). In Europe, organic food production is defined as a management system with sustainment and enhancement of the ecosystem using natural internal resources as well as following high animal welfare standards(2). The key principles in organic farming compared to principles in conventional farming and food production is that the use of chemical pesticides and synthetic fertilisers are nearly prohibited, that use of antibiotics in animals is restricted, that genetically modified (GM) organisms are banned and that crop rotation is a point of focus(2). In 2017, Denmark was the country in the world, with the highest organic food share sales, with 13·3 % of the food market sale being organic(3).

Expected positive health effects are one of the major reasons when the general population is asked about why they purchase organically produced foods(Reference Ditlevsen, Sandøe and Lassen4–Reference Kushwah, Dhir and Sagar6). Lower levels of pesticide residues(Reference Jensen, Petersen and Herrmann7,8) and higher contents of polyphenols and other antioxidants(Reference Grinder-Pedersen, Rasmussen and Bugel9,Reference Baranski, Srednicka-Tober and Volakakis10) are some of the characteristics of organic foods that are hypothesised to influence health(Reference Hurtado-Barroso, Tresserra-Rimbau and Vallverdu-Queralt11). An important issue to consider when consumption of organically produced food is associated with health outcomes is the risk of study bias, including potential confounding. The choice of consuming organically produced foods may be a marker of general health-conscious behaviour and family economy. Studies from both Germany and France have demonstrated that organic food consumers more often comply with other healthy lifestyle patterns(Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer12,Reference Kesse-Guyot, Peneau and Mejean13) . Whether this also implies to the general Danish population is virtually unknown but are of great importance for future studies evaluating potential health effects of organic food consumption. The objective of the current study was to analyse associations between organic food consumption and different lifestyle, socio-demographics, and dietary factors among a cohort of Danish adults.

Methods

Study population

Between December 1993 and May 1997, 57 053 Danish men and women, living in the areas of Copenhagen or Aarhus (the two largest cities in Denmark), aged 50–64 years and with no previous cancer diagnosis registered in the Danish Cancer Registry were enrolled into the Diet, Cancer, and Health (DCH) study. The DCH cohort is a prospective study investigating associations between foods, dietary components, nutrients, lifestyle, environmental exposures and cancer(Reference Tjonneland, Olsen and Boll14).

Data collection

At baseline, between 1993 and 1997, participants fulfilled a 192-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and a lifestyle questionnaire, which among others, gathered information about smoking habits, alcohol intake, physical activity as well as educational level and occupation. Moreover, each participant visited a study centre in either Aarhus or Copenhagen where anthropometric measurements and biological samples were collected. Between 1999 and 2002, corresponding to 5 years after baseline, participants received an updated FFQ and lifestyle questionnaire to conduct a follow-up study. The FFQ at the follow-up period additionally contained questions about the frequency of organic food consumption, which are the outcome of interest in the current study.

Inclusion/exclusion

Out of the 57 053 participants from baseline, 44 872 responded to the follow-up questionnaires. Of these, 1663 persons were excluded due to missing information about dietary or lifestyle habits or information about the frequency consumption of organic foods. This resulted in 43 209 subjects being included in the present cross-sectional study.

Organic food consumption

Information about organic food consumption was obtained from the FFQ completed in 1999–2002, for the following six food groups: vegetables, fruits, dairy products, egg, bread and cereal products, and meat. Participants reported their organic food consumption in frequencies specified as never, sometimes, often and always. The reporting of the intake of organic food was in the current study converted into an overall organic food score ranging from 6 to 24 adding up the values: never = 1, sometimes = 2, often = 3 and always = 4 for each of the six food groups. The organic food score was further divided into categories defining the overall levels of organic food consumption: never (organic food score of 6), low organic food consumption (organic food score of 7–12), medium organic food consumption (organic food score of 13–18) and high organic food consumption (organic food score of 19–24).

Lifestyle and socio-demographic data

At baseline between 1993 and 1997, information about educational level (short < 8 years, medium 8–10 years and long > 10 years) was obtained from the lifestyle questionnaire. At the study centre visit, weight and height were measured by health professionals which were used to calculate body mass index (BMI). At the follow-up between 1999 and 2002, updated information about physical activity, smoking habits and alcohol intake were obtained from the lifestyle questionnaire.

Dietary data

Information about dietary intake was obtained from the FFQ completed in 1999–2002. In the FFQ, participants were asked to report their average intake of different foods and beverages over the past 12 months in frequencies ranging from less than once per month and up to eight times or more per day. The FFQ has been validated against seven days weighed dietary records and is suitable for categorising participants according to their dietary intake(Reference Tjønneland, Overvad and Haraldsdóttir15). The daily intake of each food group and specific nutrients was calculated using the program FoodCalc(Reference Laurtizen16). In the present study, a specific focus was on the food groups: vegetables, fruits, dairy products, egg, cereal products and meat, as these food groups were covered by the questions about organic food consumption. Moreover, based on the estimated daily food intake, adherence to selected Danish national dietary guidelines from 2013 was calculated and used as a marker for healthy dietary habits. The Danish national dietary guidelines included in the current study were: eat minimum 600 g of fruits and vegetables/day (including up to 100 ml juice) whereof at least 300 g should be vegetables (excluding mushrooms and potatoes), eat minimum 350 g of fish/week including 200 g of fatty fish, eat minimum 75 g of whole grain/day and eat maximum 500 g of red and processed meat/week().

Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the variables measuring frequency of organic food consumption, lifestyle, socio-demographic characteristics and diet is for the continuous variables presented as medians with corresponding 5th and 95th percentiles, and for the categorical variables presented as the number of persons and percentages. The possibility of applying ordinal logistic regression models was investigated, but in many instances the proportional odds assumptions were not fulfilled. Therefore, polytomous logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between the level of organic food consumption (never consumption, low consumption, medium consumption and high consumption) with lifestyle, socio-demographics and dietary habits(Reference Kleinbaum, Klein, Dietz, Gail and Krickeberg18). Never consumers of organic foods were used as the reference outcome category throughout all analyses. Relative risk ratios (RRR) for the level of organic food consumption compared to no consumption were calculated in relation to sex (women and men), educational level (short < 8 years, medium 8–10 years and long > 10 years), BMI (< 25 kg/m2, 25–29·9 kg/m2 and ≥ 30 kg/m2), physical activity (participating in sports, yes/no), alcohol intake (meeting the recommended maximum intake of alcohol, ≤ 7 units/week for women and ≤ 14 units/week for men, yes/no) and smoking status (never, former and current). In regard to dietary intake, RRR were calculated for associations with intakes of vegetables, fruits, dairy products, egg, bread and cereal products, and meat, all presented in quartiles, as well as the adherence to selected national dietary guidelines as specified previously. In supplementary material, stratified analyses by sex can be found for the association between organic food consumption and lifestyle and socio-demographics due to observed interaction by sex with few of the covariates.

The SAS statistical software release 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses. Univariate and freq procedures were used for the descriptive statistics and proc logistic to calculate RRR.

Results

Lifestyle, socio-demographic and dietary characteristics of the cohort

Table 1 shows the lifestyle, socio-demographic and dietary characteristics of the cohort participants. The cohort participants had a median age of 61 years and 53 % were women. The highest proportion had a medium-long education, was in the BMI group < 25 kg/m2, did not participate in sports, had a low intake of alcohol (≤ 7 units/week for women and ≤ 14 units/week for men) and were never or former smokers. The cohort participants were eating all the specified food groups and had a median intake of 144 g vegetables/day, 243 g fruits/day, 310 g dairy products/day, 19 g egg/day, 183 g bread and cereal products/day and 135 g meat/day.

Table 1 Lifestyle, socio-demographic and dietary characteristics of the cohort

P5, 5th percentile, P95, 95th percentile, n, number of participants.

Organic food consumption

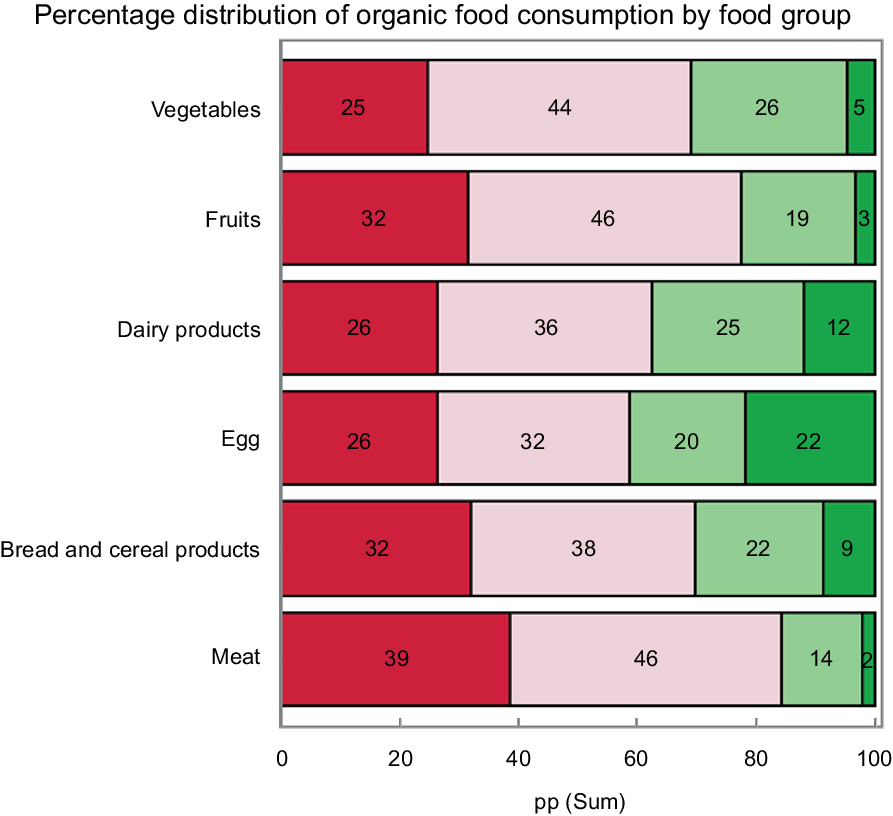

Table 1 and Figure 1 show the distribution of the overall organic food consumption and consumption by the specific food groups. Among the total cohort, 15 % reported never consuming organic food, 39 % were in the category of low organic food consumption, 37 % were in the category of medium organic food consumption and 10 % were in the category of high organic food consumption (Table 1). When looking at the consumption of the specific food groups, egg was the food group that the largest proportion of the cohort participants reported they consumed always organic (22 %), whereas meat was the food group that the largest proportion of the cohort reported they never consumed organic (39 %) (Fig 1). Moreover, it was observed that 28 % of the study participants reported the same organic frequency consumption for all six food groups and 71 % used a maximum of two out of the four different frequency categories, whereas only 3·5 % used all four frequency categories for organic food consumption (data not shown).

Fig. 1 Percentage distribution of organic food consumption by food group. Colour description: red = never consuming organic, light red = sometimes consuming organic, light green = often consuming organic, green = always consuming organic

Organic food consumption and associations with lifestyle, socio-demographics and diet

All investigated lifestyle and socio-demographic factors were associated with organic food consumption. The RRR of having a low organic food consumption compared to never eating organic foods, a medium intake of organic foods compared to never eating organic foods and having a high organic food consumption compared to never eating organic foods were 1·3, 1·7 and 2·0, respectively, for women compared to men. Furthermore, the relative risk of consuming organic foods at any level compared to never consuming organic foods was higher among persons with long education compared to persons with short education, persons with BMI < 25 kg/m2 compared to persons with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, persons with low intake of alcohol compared to those with high alcohol intake, persons participating in sports compared to persons not participating in sport, and among persons who did never smoke or were former smokers compared to current smokers. The observed associations tended to be more distinct with higher levels of organic food consumption except for associations with alcohol intake, and smoking habits where little differences was seen. It was observed that the higher the BMI class, the lower the relative risk of having a higher level of organic food consumption compared to never consumers of organic food. Moreover, it was observed that the longer the education, the higher the relative risk of reporting higher versus no organic food consumption compared to persons with short education (Table 2).

Table 2 RRR of organic food consumption in relation to lifestyle and socio-demographic factors

RRR, relative risk ratio.

Never consumers of organic food is the reference outcome category (n 6333). As for example, looking at sex the RRR is the relative risk of higher versus no consumption for women divided by the corresponding relative risk of higher versus no consumption among men.

* Weekly alcohol limits: ≤ 7 units/week for women and ≤ 14 units/week for men.

In relation to dietary habits, the RRR of having a low organic food consumption compared to no organic food consumption, a medium consumption of organic foods compared to no organic food consumption and a high organic food consumption compared to no organic food consumption were 1·3, 2·1 and 3·5, respectively, among persons who adhered to the national recommended intake of vegetables by having an intake of at least 300 g vegetables/day compared to not adhering to the recommendation. Similarly, the relative risk of consuming organic food at any level compared to no consumption of organic food was highest among persons who adhered to the other Danish national dietary guidelines by eating minimum 600 g fruits and vegetables/day whereof at least 300 g were vegetables, minimum 350 g fish/week including 200 g fatty fish, minimum 75 g whole grain/day, and maximum 500 g red and processed meat/week. The associations were more distinct with higher levels of organic food consumption (Table 3). In a similar analysis, we evaluated the quartile intake of vegetables, fruits, dairy products, egg, bread and cereal products, and meat in relation to the level of organic food consumption (Fig 2). Overall, a positive association was observed between the intake of vegetables, fruits, and bread and cereal products and the level of organic food consumption, meaning that the higher the quartile intake of vegetables, fruits, and bread and cereal products, the higher the relative risk of having a low, medium or high organic food consumption compared to no organic food consumption. A negative trend was observed with the intake of meat where the higher the quartile intake of meat, the lower the RRR of having a higher level of organic food consumption compared to the lowest quartile intake of meat and no consumption of organic food. No trend-wise association was observed between the intake of egg and dairy products in quartiles and the level of organic food consumption (Fig 2).

Table 3 RRR of organic food consumption in relation to the adherence to national dietary guidelines

RRR, relative risk ratio.

Never consumers of organic food is the reference outcome category (n 6333). As for example, looking at vegetables the RRR is the relative risk of higher versus no consumption for persons eating ≥ 300 g vegetables/day divided by the corresponding relative risk of higher versus no consumption among persons eating < 300 g vegetables/day.

Fig. 2 Forest plot illustrating the association between the levels of organic food consumption in relation to quartile intake of vegetables, fruits, dairy products, egg, bread and cereal products, and meat. Never consumers of organic foods is the reference outcome category. RRR, relative risk ratio, Q quartiles

Stratified analyses by sex for associations between organic food consumption and lifestyle and socio-demographics can be seen in the supplementary material (Online Resource). The patterns were, in general, the same when analysing men and women separately; however, it was observed that higher levels of organic food consumption among women were modified by adherence to the Danish alcohol guidelines, educational length and smoking habits.

Discussion

Organic food consumption at any level compared to never consuming organic food was highest among women, persons with long educational level, persons with BMI < 25 kg/m2, persons participating in sports, persons with low intake of alcohol and persons who did not smoke or were former smokers. Persons who adhered to the Danish national dietary guidelines by eating minimum 600 g fruits and vegetables/day whereof at least 300 g were vegetables, minimum 350 g fish/week including 200 g fatty fish, minimum 75 g whole grain/day, and maximum 500 g red and processed meat/week, more likely reported a level of organic versus no organic food consumption compared to persons who did not adhere to the Danish national dietary guidelines. The associations were more distinct with higher levels of organic food consumption.

The present cross-sectional study has limitations that need to be considered, before interpreting the findings. Lifestyle factors, dietary intake and the frequency consumption of organic foods were all measured by self-reported questionnaires, which can potentially lead to information bias. Overreporting good habits and underreporting poor habits might potentially influence the results, though we have no factual evidence for this. Further, some people may consume organic food without knowing. Moreover, information about organic food consumption was obtained from questions with qualitative frequency categories, which makes it difficult to measure the exact quantity of organic food consumption. Both of these limitations may result in misclassification of organic food consumption, though the findings are in line with previous studies(Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer12,Reference Kesse-Guyot, Peneau and Mejean13) . The present study also has several strengths. The questionnaire gathers information about organic food consumption of specific food groups. The potential health effects regarding organic food consumption might differ depending on the food groups as the organic food production practices differ depending on whether it is plant foods or animal foods in relation to, for example, pesticides, GM organisms, or the use of antibiotics(2). The distinction of the specific foods consumed either organic or conventional is relevant for future studies investigating organic food consumption and health, as these practices might influence health differently. It will moreover be possible to evaluate whether it is the intake of the specific food groups that are important or the fact that it is organic or conventional that might have an impact on health.

The Danish national dietary guidelines and recommended alcohol limits that apply today were used in the present study as a general marker of healthy dietary and alcohol habits, despite these are different from the guidelines that existed in 1999–2002(19) during the data collection. This might to some extent explain why the highest proportion of the cohort did not adhere to the official dietary guidelines in the present study. However, it was observed that healthy dietary and alcohol habits and lifestyle factors were associated with organic food consumption. Similar results have been observed in studies from France and Germany. In the French study, it was observed that persons who adhered to the dietary guidelines more often were regular organic food consumers(Reference Kesse-Guyot, Peneau and Mejean13). Moreover, in the study based on German adults, they observed that persons with higher intakes of fruits and vegetables and less meat, persons being physically active and persons who did never smoke were more likely to eat organic food(Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer12), all similar to what we observed in the current study. In addition, a Danish study based on pregnant women found that higher social class, never smoking, BMI < 25 kg/m2, physical activity, living area (eastern Denmark) and urbanisation were associated with more frequent organic food consumption. A high intake of vegetables and fruits, among other food groups, was also associated with more frequent organic food consumption(Reference Petersen, Rasmussen and Strom20). These findings have to be considered in studies evaluating associations between organic food consumption and health, as factors such as smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, overweight and poor dietary habits are associated with the incidence of non-communicable diseases(21–25). Studies investigating associations between organic food consumption and health are needed and are important for the identification of potentially modifiable risk factors in the prevention strategy for non-communicable diseases. A thorough adjustment strategy in epidemiological studies looking at organic food consumption in relation to health outcomes is therefore needed to reduce the risk of biases.

The generalisability of the findings based on the current cohort has to be considered when the results are interpreted. When looking at the individual categorical level for the variables BMI, alcohol and smoking, the highest proportion of the participants were in the category of BMI < 25 kg/m2 (45 %), fulfilled the weekly alcohol limits (56 %) and were never (37 %) or former (36 %) smokers. Still, when looking at the distributional variation for each variable, the cohort are well represented across categories of BMI, alcohol intake and smoking habits. If the cohort participants are representative for the general population within each lifestyle category, generalisability of the results is possible. However, we know that the current cohort participants had a higher representation of persons with high socio-economic status defined as educational length, occupation and years in the workforce compared to non-participants(Reference Tjonneland, Olsen and Boll14). As a higher educational level was associated with a higher frequency consumption of organic foods in the present study, the pattern given might not be fully representative of the general Danish population. Moreover, it has been observed in a Danish consumer behaviour survey from 2014 that organic food consumption is higher in larger cities than smaller cities(Reference Rasmussen and Lundø26). The current study participants lived in either Aarhus or Copenhagen, which are the two largest cities in Denmark, and this might also have had an impact on the observed large proportion of participants having a medium or high organic food consumption.

Based on the current cohort of middle-aged Danish adults, organic food consumption was associated with a healthy lifestyle, favourable socio-demographics and adherence to the Danish national dietary guidelines. These findings are important to consider in the adjustment strategy for future studies investigating associations between organic food consumption and health, to reduce confounding.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We thank Katja Boll and Nick Martinussen for data management and assistance. Financial support: This study was funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (Award number: 0134-00441B). The Independent Research Fund Denmark had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: All authors of this research paper have directly participated in the conceptualisation of the study. JA, KF and AO evaluated the analytical methods. JA performed the formal analysis and visualisation of the results with support from KF. JA analysed the results and wrote the original draft. KF, OR-N, JH, CK, AT and AO made review and editing of the initial draft. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the regional ethical committees on human studies in Copenhagen and Aarhus (File (KF)11-037/01) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001270