The Mediterranean diet is considered one of the healthiest dietary models, and numerous epidemiological and nutritional studies have shown that Mediterranean countries benefit from lower rates of chronic disease morbidity and higher life expectancy. Thus, the traditional Mediterranean diet protects against myocardial infarction, some tumours (e.g. breast, colorectal and prostate), diabetes and other diseases associated with oxidative stress(Reference Panagiotakos, Pitsavos, Chrysohoou, Stefanadis and Toutouzas1–Reference Giugliano and Esposito6). It may also contribute to reducing some disease complications, e.g. onset of a second myocardial infarction, risk of coronary heart surgery failure and diabetic vascular complications(Reference Trichopoulou and Lagiou7–Reference Serra-Majem9).

Although the Mediterranean basin covers several different regions, all of their diets share common characteristics, including a central role for olive oil. Olive oil is not only beneficial for health but also associated with the consumption of large amounts of vegetables in salad and legumes and other cooked foods(Reference Trichopoulou10). Fats represent approximately 30–40 % of the daily energy intake, depending on the country in question(Reference Trichopoulou and Lagiou7). The differential characteristics of the Mediterranean diet have been described by Keys(Reference Keys11), although societal changes have led to varied levels of adherence to the Mediterranean diet in different countries. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated medium levels of adherence to this diet in Spain, at around 50 % of theoretical values(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, García, Pérez-Rodrigo and Aranceta12–Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Romaguera, Rivas, Feriche, Pons, Tur and Olea-Serrano14). The influence of region on diet quality highlights the importance of considering regional nutrition strategies(Reference Rodrigues, Caraher, Trichopoulou and de Almeida15, Reference Chen and Marques-Vidal16). Thus, a reduction in diet quality in Portuguese households was associated with a deviation from the traditional Mediterranean diet and a lower compliance with WHO dietary goals. Recent changes in the actual Mediterranean diet include a reduction in energy intake and a higher consumption of foods with low nutrient density (e.g. soft drinks, candy, sweets, etc.). In Spain, in association with cultural and lifestyle changes, there has been a reduction in the intake of antioxidants and vitamins, an increase in the proportion of SFA, and a decrease in the consumption of fibre, among other changes(Reference Serra-Majem and Ribas17).

Children and adolescents may be the age groups with the most deteriorated Mediterranean diet profile, and there is a need for nutrition education programmes to establish healthy eating habits at a young age that will have beneficial effects in later life(Reference Serra-Majem, Aranceta Bartrina, Ribas Barba, Perez Rodrigo and García Closas18). Both epidemiological and metabolic studies suggest that individuals can benefit greatly by adopting elements of Mediterranean diets(Reference Willett19).

This paper presents the results of applying the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and adolescents (KIDMED), developed by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, García, Pérez-Rodrigo and Aranceta12, Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20), to a large sample of schoolchildren in Southern Spain.

Material and methods

The sample comprised 3190 schoolchildren from Granada in Southern Spain, aged 8–16 years (mean 10·8 years; sd 1·8 years). Participating schools were randomly selected, each from a different neighbourhood of the city of Granada. Experienced and specifically trained interviewers administered each participant with a semi-quantitative FFQ, a 24 h recall, and a questionnaire on lifestyle and food habits(Reference Mariscal-Arcas, Romaguera, Rivas, Feriche, Pons, Tur and Olea-Serrano14, Reference Mariscal21–Reference Velasco23). Data from these questionnaires were used to calculate the KIDMED index of sixteen items, twelve of which are positively scored and four negatively scored(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, García, Pérez-Rodrigo and Aranceta12, Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20). Total KIDMED scores were classified as follows: ≥8 points, good (optimal Mediterranean diet); 4–7 points, average; and ≤3 points, poor.

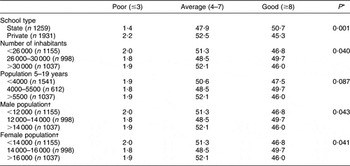

Study age ranges were selected according to FAO/WHO(24). Other study variables were as follows: school type (public/private), number of inhabitants in the neighbourhood of the school, number of inhabitants between 5 and 19 years and number of male and female inhabitants (Table 1). The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution.

Table 1 Percentage of the study population with different KIDMED classifications as a function of school and district characteristics

*Student’s t-test for school type and ANOVA for remaining variables.

†Population categorized by the total population (males and females) in each district (city census).

The SPSS for Windows statistical software package version 15·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyse the data, applying ANOVA tests and Student’s t-test. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 2 shows mean values of nutrients and ANOVA results as a function of age and sex. The validity of the questionnaire was tested by comparing the energy, protein, lipid and carbohydrate values estimated in the 24 h recall with the values obtained in the semi-quantitative FFQ, using the Spearman test. Rho values found were 0·690 for proteins, 0·830 for lipids and 0·785 for carbohydrates, with P < 0·05 in all cases.

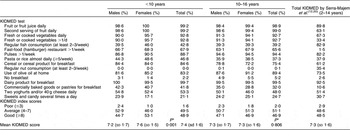

Table 2 KIDMED index scores

*Student’s t-test, P ≤ 0·05.

A descriptive analysis was performed of KIDMED levels as a function of age group (<10 and ≥10 years) and sex, and results were compared with findings of the EnKid Spain-wide study(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20) (see Table 2).

Table 2 shows the KIDMED index results by age and gender and the comparison with findings obtained for the whole of Spain in the EnKid survey by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20), for similar age ranges. Among the 8–10-year-olds, the KIDMED index classification was ‘good’ in 48·6 % of the population, ‘average’ in 49·5 % and ‘poor’ in 1·6 %. The boys showed a higher percentage (2·4 %) of poor index scores v. the girls, while the girls had a higher percentage (53·1 %) of good scores. These gender differences were statistically significant (P = 0·001). The mean score for the 8–10-year-old population was 7·4 (sd 1·6). Among the 10–16-year-olds, the KIDMED index classification was good in 46·9 % of the population, average in 51·1 % and poor in 2·0 %. The boys showed higher percentages of poor (2·3 %) and good (47·1 %) scores v. the girls, while the girls had a higher percentage of average scores (51·3 %). In this older age group, these gender differences did not reach statistical significance (P = 0·806). The mean score for this age group was 7·3 (sd 1·6). Around half of both age groups had an ‘average’ KIDMED score (4–7) (Table 2).

As shown in Table 1, significant differences in index scores were observed as a function of the school type (P < 0·001) and of the total number of inhabitants (P = 0·040) and number of male (P = 0·043) and female (P = 0·041) inhabitants in the neighbourhood of the school.

Discussion

The mean energy intake of the present study population was higher than the mean theoretical energy expenditure calculated using equations proposed for these ages by the FAO/WHO/UNU(24). Their protein intake was more than double recommended levels, as reported in other Spanish studies(Reference Serra, Ribas, Pérez, Roman and Aranceta25, Reference Barquera, Rivera, Safdie, Flores, Campos-Nonato and Ca26) and consistent with the general trend in the Spanish population to consume large amounts of meat and meat derivatives. The lipid intake of this group was higher than that observed in studies in Northwest Spain and Australia(Reference Tojo and Leis27, Reference O’Connor, Ball, Steinbeck, Davies, Wishart and Gaskin28). Their energy profile was clearly imbalanced, with a high percentage of energy from proteins and lipids and a low proportion from carbohydrates, a characteristic situation in Mediterranean countries(Reference Moreno, Sarria and Popkin29, Reference Mena, Faci, Ruch, Aparicio, Lozano Estevan and Ortega Anta30). It is recommended that lipids should supply less than 35 % of the total energy in the diet(31). The percentage of energy contributed by fatty acids was also imbalanced, as found in numerous countries(Reference Moreno, Sarria and Popkin29, Reference Aeberli, Kaspar and Zimmermann32, Reference Hanning, Woodruff, Lambraki, Jessup, Driezen and Murphy33). The intake of mineral salts differed significantly (P < 0·01) from recommendations, and only the children (<10 years) met the RDI for calcium. There appears to be a relationship between a low-Ca diet and a deficiency in other micronutrients(Reference New, Robins, Campbell, Martin, Garton and Bolton-Smith34), and an adequate Ca intake during initial stages of life is critical to achieving an optimal bone mass peak(Reference Ortega and Povea35, Reference Wosje and Specker36). The RDI for Fe intake was fully met by the children but not by the male or female adolescents. Iodine intake was lower than the RDI in all three groups, possibly due to their low consumption of fish, fruit and vegetables(Reference Chrysohoou, Panagiotakos, Pitsavos, Skoumas, Krinos, Chloptsios, Nikolaou and Stefanadis37). Among the vitamins studied, only vitamin E intake was below the daily recommendations for this population, as found in other Spanish studies(Reference Ortega, Mena, Faci, Santana and Serra-Majem38, Reference Tur, Serra-Majem, Romaguera and Pons39).

The KIDMED Diet Quality Index(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20), which evaluates adherence to an optimum traditional Mediterranean diet, was applied to 3190 schoolchildren from Granada in Southern Spain. The mean index score of this 8–16-year-old population was 7·33 (sd 1·63) points, classified as ‘average–good’ by the authors. Slightly better scores were obtained by the under-10-year-olds than by the children aged 10 years and older. Among the under-10-year-olds, the index score was significantly higher (P < 0·001) for the girls than for the boys. In comparison with the KIDMED results obtained by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20) for children aged 2–14 years, the two populations reported practically identical percentages of pasta, rice, breakfast milk products, yoghurt and cheeses, and similar percentages of fruit, juices, pulses, desserts and sweets. However, a higher proportion of the present population consumed a second piece of fruit, cereals, cereal products and vegetables, while the percentage consuming fish 2/3 times weekly was almost half that in the study by Serra-Majem et al.(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20). The frequency of visits to fast food establishments was considerably higher than that reported by the children in the earlier study(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20). The intake of nuts was reported by virtually none of the present children compared with 35·4 % in the reference study(Reference Serra-Majem, Ribas, Ngo, Ortega, Garcıa, Perez-Rodrigo and Aranceta20). A mean of >85 % of the Granada population used olive oil compared with 73·5 % in the reference population, consistent with other findings in southern Spain, a major producer of olive oil, where it is firmly embedded in sociocultural traditions. Thus, the mean individual consumption of oil in this region (56 g/d) is 6 % higher than in the rest of Spain (52 g/d)(31). Numerous researchers have described the benefits of consuming olive oil for its high MUFA and antioxidant content(Reference Trichopoulou and Dilis40, Reference Waterman and Lockwood41). Besides olive oil, wine also contributes to the intake of antioxidants in the Mediterranean diet(Reference Papamichael, Karatzi, Papaioannou, Karatzis, Katsichti, Sideris, Zakopoulos, Zampelas and Lekakis42) but is not expected to be consumed by children and is therefore not included in the KIDMED survey.

Less than 2·5 % of the children from either private or state schools had a poor KIDMED score, with around half of each population classified with a score between average and good. ANOVA test results showed a significant difference in the distribution of poor, average and good scores as a function of the number of inhabitants and of male and female inhabitants (Table 1).

In conclusion, the nutritional behaviour of the present population of schoolchildren is similar to that found in the earlier KIDMED study. Discrepancies can be attributed to their inclusion of a younger age group.

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interest:The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding support:The study was supported by grants from the Concejalia de Salud del Excmo, Ayuntamiento de Granada, Spain.

Authors’ contributions:The following contributions were made by each author: M.M.-A. – study design, statistical treatment and redaction of article. A.R. – study design, statistical treatment and redaction of article. J.V. – data collection and development of database. M.O. – data collection and treatment. A.M.C. – data collection and collaboration with institutions. F.O.-S. – study design and coordination and redaction of article.

Acknowledgements:The authors wish to thank Richard Davies for his assistance with the English version.