In the UK and many other Western countries, breast-feeding rates fell throughout the first half of the 20th century and remain at low levels. Over the past decades, work conducted to raise the rates of breast-feeding has met with some successReference Hamlyn, Brooker, Oleinikova and Wands(1, Reference Bolling, Grant, Hamlyn and Thornton2), but serious problems remain internationally as highlighted in the second Innocenti Declaration on the protection, promotion and support of breast-feeding(3). In the UK around 24 % of babies will be formula-fed from birth, and by 6 weeks following birth 79 % of babies will be fed exclusively or partially on infant formulaReference Bolling, Grant, Hamlyn and Thornton(2), with the highest rates of formula feeding among women of lower socio-economic status. The situation is similar in other Western countries including the USA(4), while in other countries, including China, previously high breast-feeding rates are declining rapidlyReference Xu, Binns, Nazi, Shi, Zhao and Lee(5). Worldwide, many millions of babies will be fed breast milk substitutes, usually by use of a plastic bottle and teat. The health consequences of this are enormous, and result in increased mortality and morbidity in both developed and developing countriesReference Edmond, Zandoh, Quigley, Amenga-Etego, Owusu-Agyei and Kirkwood(6, Reference Quigley, Cumberland, Cowden and Rodrigues7).

Risks to the baby from formula feeding not only include the intrinsic nutritional and immunological deficiencies of formula compared with breast milk. They also include risks that could potentially be reduced, such as errors in the manufacturing process, contamination during storage and transport(8), errors in reconstitution of infant formula in the homeReference Renfrew, Ansell and Macleod(9), and ensuring effective cleaning and sterilisation of the equipment used.

Article 1 of the WHO Code on the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes endorses ‘the proper use of breastmilk substitutes, when these are necessary, on the basis of adequate information’(10). What are the evidence-based ways of ensuring the ‘proper use’ of such substitutes? Unlike the evidence base for the promotion and support of breast-feeding, which has been strengthened considerably in recent decadesReference Fairbank, O’Meara, Renfrew, Woolridge, Sowden and Lister-Sharp(11–Reference Renfrew, Dyson, Wallace, D’Souza, McCormick and Spiby13), the evidence base for reducing the risks of formula feeding seems to be scanty. It is not clear from the epidemiological literature what proportion of common diseases such as gastroenteritis is an inevitable consequence of the use of a product of lower quality than breast milk and what proportion could be prevented by improved practice. One recent studyReference Quigley, Cumberland, Cowden and Rodrigues(7) has suggested that, in formula-fed infants, there was significantly more diarrhoeal disease in those infants whose carer did not sterilise bottles and teats with steam or chemicals, particularly in infants under 6 months of age (adjusted OR = 9·13; 95 % CI 1·17, 71·39; P = 0.012). No information was available, however, on the relative effectiveness of the different methods being used.

Milk is the perfect medium for growth of bacteria, and therefore poorly cleaned feeding equipment can be a potent source of infection for babiesReference Thompson(14). The organisms of most concern are reported to be Salmonella (8) and Enterobacter sakazakii (8, Reference Forsythe15). To reduce contamination with these organisms, the Food Standards Agency and Department of Health in England have recently recommended that formula feeds are made up using boiled water that is >70°C (water that has been boiled and left to cool for no more than 30 min) and that formula is made up fresh for each feed(16). A report by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)(8) concluded that cleaning and sterilisation of equipment in the home is a critical part of the avoidance of infection; recommendations include the use of ‘sterile bottles, achieved by heating and chemical methods’, although no evidence is provided on the relative effectiveness of these methods. The recent WHO guidelines published in 2006 and updated in 2007(17) are consistent with the EFSA recommendations and suggest that manufacturer’s instructions should be followed for chemical or steam sterilisation procedures. These guidelines are stated (p. 2) to be ‘largely based on the findings of a quantitative microbiological risk assessment for Enterobacter sakazakii’. Effective cleaning and sterilisation of infant feeding equipment offers the opportunity to minimise risks to the baby and could result in significant clinical and cost benefitsReference Rowan and Anderson(18).

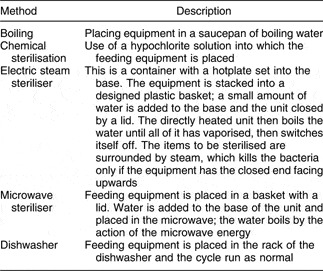

Various methods of cleaning and treating infant feeding equipment are used internationally (Table 1). Potential problems in using these methods routinely include cost, the time-consuming and complex nature of some methods, confusion over the length of time equipment should be boiled, left to soak or left in the microwave, whether or not equipment left to soak in hypochlorite should be rinsed, and how equipment immersed in boiling water or hypochlorite should be removed and dried. Such confusion, expense and the time needed may result in a lack of compliance. It is also not clear if basic hygiene measures such as hand-washing are seen by parents and carers as important in the face of more complicated approaches. Furthermore, use of dishwashers has been implicated in the release of plasticisers following a relatively small number of washesReference Mountfort, Kelly, Jickells and Castle(19, Reference Brede, P Fjeldal, Skjevrak and Herikstad20). It is not surprising, therefore, that there is variation in the information and advice given by health professionals. One survey conducted in Scotland found that, before the birth of their baby, only 40 % (n 25) of women considering bottle feeding had been given any information on sterilising equipmentReference Cairney and Alder(21). It is essential to maximise the opportunities for women to breast-feed, and it is also very important to offer opportunities for parents to learn about minimising the risks of formula feeding.

Table 1 Methods of cleaning or sterilising infant feeding equipment

Preliminary work

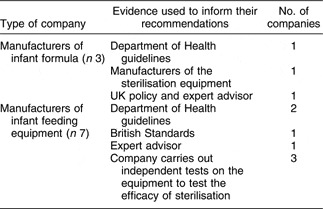

Two brief investigations were undertaken to inform this review and to search for unpublished studies. First, UK-based manufacturers of infant feeding equipment and formula who made recommendations for cleaning and sterilising techniques in the literature accompanying their product were identified. The health advisor for each company was contacted by telephone by one of us (M.M.); all agreed to be interviewed. They were asked for information about the evidence base that informed their published recommendations. Responses are summarised in Table 2. Although two infant formula companies and two manufacturers of feeding equipment reported that they based their instructions on Department of Health guidelines or policy, at the time of the interviews (2003) no such guidelines existed on the cleaning and sterilisation of infant feeding equipment. No relevant studies were identified.

Table 2 Responses to the survey of manufacturers of infant feeding formula and infant feeding equipment

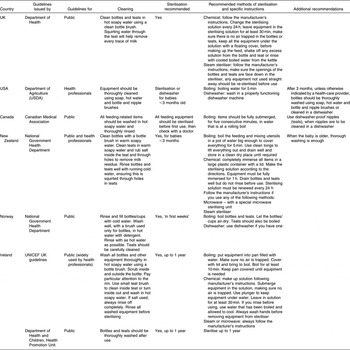

Second, we contacted the UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative Co-ordinator in similar developed countries and requested copies of relevant national guidelines and information about the evidence base used. The results for these six countries are summarised in Table 3 and demonstrate variation in whether sterilisation was recommended for all babies (UK, Ireland)(22–24), only for those under 3 months of age (New Zealand(25), Norway(26), USA(27)), or only on the recommendation of a health professional (Canada)Reference Younger-Lewis(28). In the USA and Norway the use of a dishwasher was recommended as an alternative to sterilisation. There were also variations in the detailed instructions for cleaning teats (i.e. use of salt or not), and in whether bottles and teats sterilised by the chemical method should be rinsed before use. No international respondent was aware of any evidence of effectiveness informing the guidelines from their country.

Table 3 Comparison of national guidelines for cleaning and sterilising infant feeding equipment

The aim of the systematic review described in the present paper was to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of different methods of cleaning and sterilisation of infant feeding equipment used in the home.

Methods

Literature search

The first search was conducted in 2003 on the following databases: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Psycinfo, British Nursing Index (BNI), Allied and Complementary Medicine, Premedline, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), EBM reviews, SIGLE and the Cochrane library database (which included CDSR, ACP Journal Club, CCTR and DARE). Electronic database searches were supplemented with hand searches of the references of selected papers, relevant policy documents and consultation with the key professionals and companies in this field. Grey literature and unpublished studies not recorded on SIGLE were identified by searching the National Research Register and the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. A broad search strategy was used to identify all relevant literature, using the following keywords and Mesh terms: bottle$, artificial feed$, formula feed$, infant feed$, teat$, sterili?$, clean$, wash$, prepar$, disinfect$, saniti$, hygien$, breastfeeding, breast pump, germ free, spotless, infection, uncontaminated. A second, structured search was run on Medline in 2006 which identified only one additional paper; the full search strategy is shown in Table 4.

Table 4 Structured search strategy, 2006

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

No date limits were set on either search. The review included research studies from developed countries that examined methods of cleaning and/or sterilisation of infant feeding equipment, either in the home or applicable to home conditions, regardless of the research design used. Studies from developing countries were excluded, as the sterilisation and infection issues are different in such dissimilar settings.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest included clinical outcomes in infants; results of microbiological tests of bottles and teats; behavioural outcomes for carers; and costs.

Data extraction

Data were systematically extracted by one reviewer (M.M. or A.M.) using pre-designed data extraction forms, and were checked by a second reviewer (M.J.R.). Included studies were assessed for quality using criteria published by the Centre for Reviews and DisseminationReference Khan, ter Reit, Glanville, Sowden and Klieijnen(29).

Results

Published literature

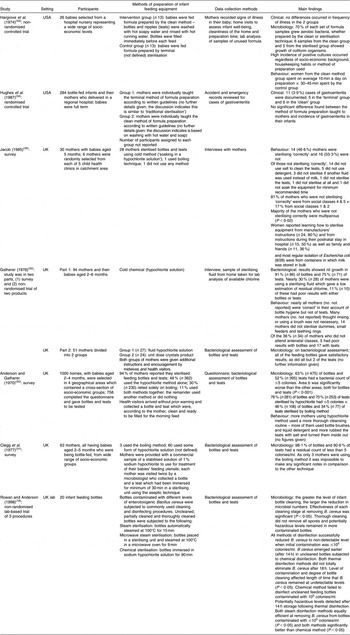

Of the 1520 references identified, only nine studies published in eight papersReference Rowan and Anderson(18, Reference Anderson and Gatherer30–Reference Vaughan, Dienst, Sheffield and Roberts36) met the inclusion criteria; all but oneReference Rowan and Anderson(18) were identified in the early search. The majority of the other citations were not research studies. No systematic reviews were identified. Details of the nine included studies are given in Table 5 and the quality of the included studies is summarised in Table 6. Eight were conducted between 1962 and 1987Reference Anderson and Gatherer(30–Reference Vaughan, Dienst, Sheffield and Roberts36) and one in 1998Reference Rowan and Anderson(18). Three were conducted in the USAReference Hargrove, Temple and Chinn(33, Reference Hughes, Sauvain, Blanton and DeLoache34, Reference Vaughan, Dienst, Sheffield and Roberts36) and six in the UKReference Rowan and Anderson(18, Reference Anderson and Gatherer30–Reference Gatherer32, 35). One was a randomised controlled trialReference Hughes, Sauvain, Blanton and DeLoache(34), four were non-randomised controlled trialsReference Rowan and Anderson(18, Reference Gatherer32, Reference Hargrove, Temple and Chinn33, Reference Vaughan, Dienst, Sheffield and Roberts36), and four were surveysReference Anderson and Gatherer(30–Reference Gatherer32, 35). The number of participants ranged from twenty-six to 758 (median, sixty-three). No studies examined cost-effectiveness. All studies had serious methodological weaknesses.

Table 5 Summary of studies included in the present review

Table 6 Design and quality assessmentFootnote * of the experimental studies included in the present review

ITT, intention to treat.

* Using criteria in Khan et al.Reference Khan, ter Reit, Glanville, Sowden and Klieijnen(29).

Two studies examined infant morbidity related to the cleaning method usedReference Gatherer(32, Reference Hargrove, Temple and Chinn33). No significant difference in the incidence of infections or illness was identified, although no studies were of appropriate design or sufficient quality or size to answer these important questions.

The largest studyReference Anderson and Gatherer(30), conducted in 1970, took place across four different geographical areas in the UK, each selected because of proximity to a public health laboratory. Methods used in the home differed across the four areas; these included the hypochlorite method alone (48 %), boiling (30 %), hypochlorite and boiling together (11 %), and the remainder either used another method (not stated) or nothing (12 %). Bottles and teats sterilised using the hypochlorite method had lower colony counts (bacterial count ≤5: 63 % (n 475) of bottles; 52 % (n 395) of teats) when samples were tested in the laboratory. The majority of mothers who used the hypochlorite method lived in rural areas and also spent more time washing and sterilising the equipment. The majority did not carry out sterilisation procedures as recommended, in spite of the fact they had received health education in this field. Clegg et al.’s study in England in 1977Reference Clegg, Duke and Prosser-Snelling(31) found similar results.

The most recent studyReference Rowan and Anderson(18) examined the effectiveness of commonly used cleaning and disinfecting procedures on the removal of enterotoxigenic Bacillus cereus from feeding bottles. This non-randomised experimental study was conducted in the laboratory, but included subjecting bottles to storage conditions which may occur in the home. The results showed that thorough cleaning reduced, but did not completely eliminate, all microbes. All of the three disinfection procedures tested (one chemical and two thermal) eliminated the organism at low levels of contamination (<105 organisms/ml) but the chemical method failed to eliminate B. cereus at potentially hazardous levels (≥105 organisms/ml) which may occur with improper use in the home.

Authors of several of the included studiesReference Hargrove, Temple and Chinn(33, Reference Hughes, Sauvain, Blanton and DeLoache34) suggested that the ‘clean’ (washed with hot soapy water and rinsed with hot running water) method is a safe alternative to traditional ‘sterilisation’ techniques, provided the safety of the water is assured. However, three studiesReference Anderson and Gatherer(30, Reference Gatherer32, 35) found higher numbers of organisms on teats, suggesting that they are more difficult to clean effectively than bottles. GathererReference Gatherer(32) indicated that bacteriology results were excellent using either thorough cleaning or sterilisation; this was attributed to the education provided for mothers. Other studiesReference Anderson and Gatherer(30–Reference Gatherer32, 35) identified a link between the failure to correctly sterilise and prepare formula feeds and a lack of ante- and postnatal education from health professionals, multiparity (mothers with two or more children) and low socio-economic status. Several authorsReference Rowan and Anderson(18, Reference Anderson and Gatherer30, Reference Clegg, Duke and Prosser-Snelling31, Reference Gatherer and Wood37, Reference Wharton and Berger38) have suggested that improved teaching for mothers and consistent advice from health professionalsReference Wharton and Berger(38) are key factors in improving sterilisation and cleaning of infant feeding equipment.

Discussion

The striking finding from the present study is the lack of good-quality information on clinical and cost-effective ways of cleaning and sterilising infant feeding equipment in the home, especially under conditions relevant to families in developed countries in the 21st century. Only two studies examined clinical outcomes for the babies. Design flaws identified included lack of randomisation, inadequate sample size and selection bias. This lack of high-quality evidence probably explains the variation in international guidelines that we identified.

The majority of studies identified were conducted in the 1950s to the 1980s, before the introduction of microwaves and the widespread use of dishwashers in the home. It was during the 1950s that there was a steady improvement in infant mortality rate due to the reduction in deaths from childhood infectious diseases, including gastroenteritisReference Anderson and Gatherer(30, Reference Lucas and Cole39, 40). This was in part due to the recognition of the dangers of contaminated water and the introduction of chemical sterilisation methods for infant feeding equipmentReference Gerber, Berlinger and Karolus(41), and forms of sterilisation used in the 1950s are still recommended. Only one studyReference Rowan and Anderson(18) tested more recent approaches (electric and microwave steam sterilisation) and found both to be more effective than chemical sterilisation. The contribution of microwaves, with the potential for overheating, and dishwashers, with the possible hazards of salt and detergent residues and the release of plasticisers, remains to be examined.

Our preliminary work found that the evidence base for the current advice given by some infant formula or feeding equipment manufacturers in the UK is unclear. Several respondents stated that they based their advice on Department of Health guidelines, but we were unable to identify the existence of such guidelines at that time. Since we conducted this preliminary work, limited guidelines have been issued by the Food Standards Agency in the UK(16) and by EFSA(8) in Europe, in response primarily to recent concern about E. sakazakii and Salmonella. The recommendation in those guidelines to make up each feed as required is likely to have implications for compliance with complex sterilisation procedures.

In the absence of a secure evidence base, it is not clear what advice health professionals should be giving. Such information as we have from the included papers in this review, however, suggests that input from health professionals does have the potential to make a difference, probably in promoting compliance with whichever method is used.

We found no studies that examined the views and experiences of parents and carers about the problems of cleaning and sterilising in the home environment, or ways in which the process might be simplified and made more efficient and effective.

Unanswered questions remain: what are parents and carers actually doing? Which methods are easier and achieve best compliance? Which methods achieve the best clinical outcomes for the babies? Are basic hygiene measures such as thorough hand-washing, cleaning of equipment and a clean water supply sufficient?

Conclusion

Bottle feeding carries inherent risks for the baby and is a potential source of bacterial contamination. There is scanty of evidence, however, on clinical and cost-effective ways of cleaning and sterilising infant feeding equipment, including both bottles and teats, in the home, and there is a risk that some parents may reject current methods as cumbersome, time-consuming and expensive. Further, the focus on ‘sterilisation’ procedures could have a paradoxical effect of reducing basic hygiene procedures such as hand-washing and thorough washing and drying of equipment, as it could induce complacency about the possibility of infection. The current evidence base provides little information about effectiveness of the range of old and new methods used, and there is no evidence that either manufacturers or health policy makers have identified the problems parents might face in their own homes. Studies are old, of poor quality and largely irrelevant to circumstances in the home in the early 21st century.

Further research

Research is needed to determine which methods of cleaning or sterilisation of infant feeding equipment are most effective and efficient, for both bottles and teats. Epidemiological studies could contribute to a more comprehensive assessment of the risks of poor practice and the likely effects of improved procedures in this important public health issue. Further surveys and qualitative studies could provide updated information on what parents and carers actually do in the home environment and what the barriers to good practice are. Such information would inform the design of a randomised controlled trial, adequately powered, of the range of methods in common use, measuring clinical and cost outcomes, as well as the views of parents and carers.

Acknowledgements

None of the authors has any competing interests.

We are grateful for the input of international colleagues in providing and translating their national guidelines: Cindy Turner-Maffei, National Coordinator, Baby Friendly, USA; Julie Stufkens, Executive Officer, New Zealand Breastfeeding Authority, New Zealand; Pat Martz, Project Manager, Population Health Strategies Branch, Alberta Health and Wellness, Canada; Rachel Myr, Staff breastfeeding specialist midwife, Sørlandet Sykehus, Kristiansand, Norway; Elisabeth Tufte, Norwegian Resource Centre for Breastfeeding, Norway; Genevieve Becker, National Coordinator, Baby Friendly, Ireland. We also thank the anonymous respondents from manufacturing companies who provided information.