The information obtained at the time of admission is important for the care of some of our most ill patients and informs all areas of assessment, diagnosis and the care planning process, including risk management strategies. The quality and completeness of the recorded information has a direct impact on the quality of patient care. Such a central document also clearly has medicolegal implications if incomplete or incorrect. This has been previously demonstrated in the documentation of risk (Reference Elbogen, Tomkins and PothulooriElbogen et al, 2003), but is also relevant to other aspects of assessment, as well as the general documentation of patient care (Reference ScottScott, 2000).

In our trust the current method of using hospital continuation sheets for admissions had led to concerns over the comprehensiveness of the information obtained, and the impact on the quality of in-patient care and medico-legal implications. Although the quality of the admission booking depends on the doctor’s level of training and experience, their attitude and enthusiasm and the patient’s cooperation, it is clearly stated that competent note-keeping is a core component of good psychiatric practice in the College’s council report of the same name (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004).

Previous studies have demonstrated that significant data are often omitted from psychiatric case notes (Reference Small and FawzySmall & Fawzy, 1988) and that the introduction of standardised formats for mental state examinations improves the quality of the information obtained (Reference Kareem and AshbyKareem & Ashby, 2000). It has also been suggested that structured assessment schedules may assist trainees in stating the likely diagnosis, investigation and management at the time of admission (Reference Lyons, Amos and MathewLyons et al, 2001). This audit was therefore designed to address the question of what impact the introduction of a standardised form has on the overall completeness of information obtained at admission booking.

Method

A list of standard information was developed by combining recommendations from multiple sources, including trust policy documents and College guidance on history-taking and mental state examination. Standards were set for 100% of admission forms to have the patient’s basic data, mental state examination, physical examination, clinical risk assessment, diagnosis and management documented. A standard of 80% was set for each of the components of the patient’s history to reflect some inevitable slippage and to allow discretion to be applied by the admitting doctor. It was deemed acceptable if booking forms referred to previous specific entries where information could be found or gave a clear reason for omitting information (e.g. uncooperative patient refusing physical examination).

Case notes of 30 current in-patients were then assessed for completeness. This represented 80% of the average number of in-patients on the wards and was considered to be a representative sample enabling repeat sampling to be performed to complete the audit cycle. Adolescents and patients admitted by the substance misuse specialist team were excluded as they would require differing histories, focusing on the specialist requirements of those services. Two authors (J.D. and M.C.) assessed the notes and where uncertainty occurred consensus agreement was used to improve interrater reliability. The presence of some information or a valid reason explaining its omission was accepted. The quality of the information documented was not assessed as this was felt to decrease the objectivity of the assessment.

A standardised core assessment form was then developed by incorporating all aspects of basic data, history, mental state examination, physical examination, a summary of findings, a clinical risk assessment, diagnosis and management plan in collaboration with trainees and the consultant body. Trainees were considered to be the most likely doctors to use the form and were surveyed for their opinions in order to help increase their sense of ownership of the form. A training session in the use of the form accompanied its introduction. A further sample of case notes from 30 patients was similarly assessed 3 months following the form’s introduction.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 11.5 for Windows. Pearson’s χ2 test was performed to assess the statistical significance of changes (P≤0.05) in the completeness of the information obtained at the time of admission.

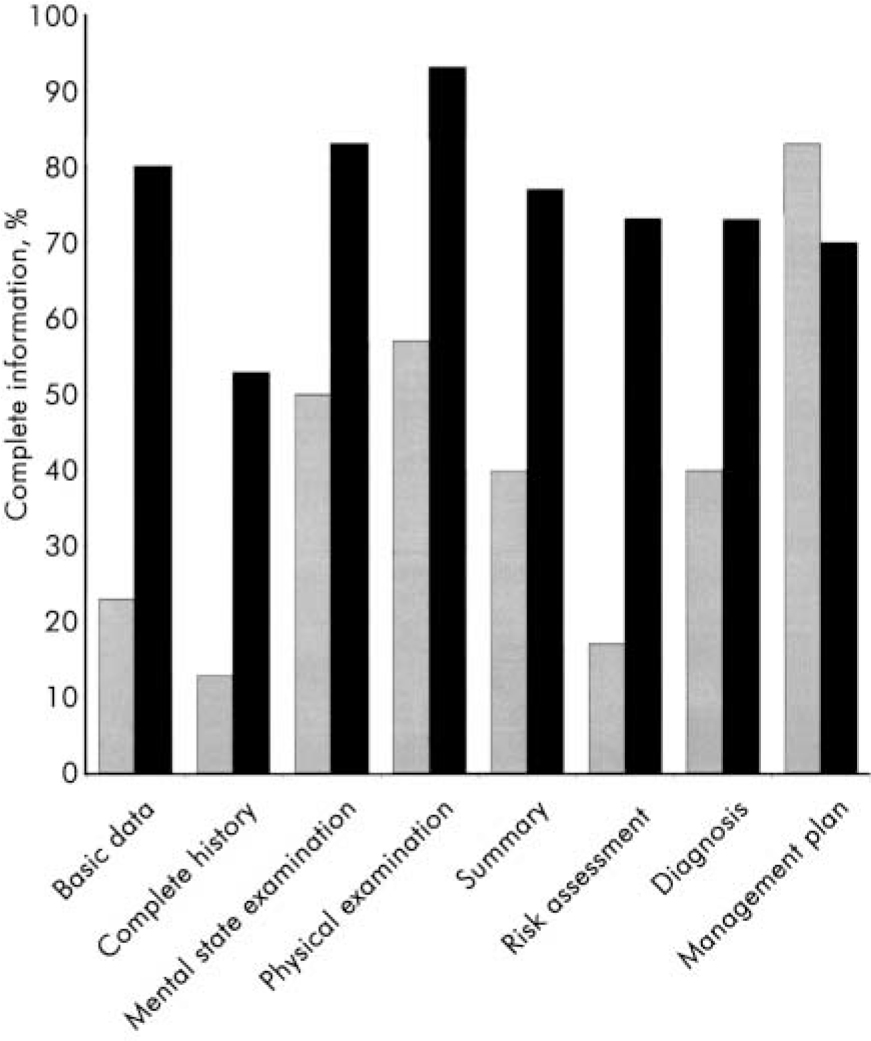

Fig. 1. Completeness of information obtained at the time of admission before and after the introduction of the standard form. ##, Before form ; ▪, after form .

Results

Prior to the introduction of the form, there were low levels of recording of family and personal history, premorbid personality (n=4, 13%), clinical risk assessment (n=5, 17%) and diagnosis (n=12,40%), as wellas doctor’s name and signature (n=9, 30%). Furthermore, a physical examination (or clear reason for its omission) was documented in only 17 case notes (57%). All of these areas showed significant improvement following the introduction of the standard form (Table 1, Fig. 1). Improvements in the recording of physical examination (P=0.002), a summary of findings (P=0.004), risk assessment (P<0.001) and diagnosis (P=0.001) were all statistically significant. Small, statistically insignificant, drops in the recording of source of referral and history of presenting complaint were noted, which probably reflect the high levels of completeness of these data prior to the form’s introduction. A larger drop was noted in the completion of the management plan, but again this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.222). Reasons for this are discussed below.

Table 1. Audit of admission booking before and after introduction of the standard form: history (n=30 for both)

| Information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to introduction of form n (%) | Following introduction of form n (%) | Change, % | P | |

| General data | ||||

| Date and time | 25 (83) | 27 (90) | +7 | 0.228 |

| Patient name | 29 (97) | 30 (100) | +3 | 0.468 |

| Mental Health Act 1983 status | 23 (77) | 28 (93) | +16 | 0.129 |

| Signed and doctor’s name | 9 (30) | 29 (97) | +67 | <0.001 |

| History | ||||

| Source of referral | 26 (87) | 24 (80) | -7 | 0.488 |

| History of presenting complaint | 29 (97) | 28 (93) | -4 | 0.544 |

| Past psychiatric history | 22 (73) | 29 (97) | +24 | 0.197 |

| Family history | 8 (27) | 23 (77) | +50 | 0.001 |

| Early life experience | 8 (27) | 24 (80) | +53 | <0.001 |

| Educational history | 6 (20) | 24 (80) | +60 | <0.001 |

| Employment history | 6 (20) | 24 (80) | +60 | 0.001 |

| Relationship/sexual history | 5 (17) | 24 (80) | +63 | <0.001 |

| Forensic history | 7 (23) | 21 (70) | +47 | 0.002 |

| Alcohol/drug history | 16 (53) | 26 (87) | +34 | 0.010 |

| Current social circumstances | 19 (63) | 24 (80) | +17 | 0.091 |

| Past medical history | 12 (40) | 25 (83) | +43 | <0.001 |

| Medications | 19 (63) | 28 (93) | +30 | 0.005 |

| Premorbid personality | 4 (13) | 17 (57) | +44 | <0.001 |

Discussion

This audit demonstrates that significant improvement in the completeness of almost all information obtained at the time of patient admission can be achieved by the introduction of a structured, standardised admission form. A drop in the recording of a management plan was noted following the introduction of this form. This may be because the form required the plan to take a biopsychosocial approach to reflect the requirements of trainees sitting the College examinations and in accordance with College recommendations for good psychiatric practice (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004). This may have discouraged trainees who did not feel competent to complete all areas of the plan. This requires further exploration and possible education to address the issue. Furthermore, none of the original standards was fully met and this indicates the need for further training and supervision for trainees admitting acute patients.

Table 2. Audit of admission booking before and after introduction of the standard form: mental state examination (n=30 for both)

| Information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental state examination | Prior to introduction of form n (%) | Following introduction of form n (%) | Change % | P |

| Appearance and behaviour | 24 (80) | 28 (93) | +13 | 0.044 |

| Speech | 22 (73) | 29 (97) | +24 | 0.011 |

| Mood and affect | 24 (80) | 27 (90) | +10 | 0.488 |

| Thought (form/content) | 20 (67) | 27 (90) | +23 | 0.117 |

| Perception | 20 (67) | 27 (90) | +23 | 0.117 |

| Cognition | 16 (53) | 26 (87) | +34 | 0.030 |

| Insight | 23 (77) | 26 (87) | +10 | 0.347 |

Overall the form was considered acceptable, as demonstrated by the high level of use and subsequent meetings to further refine the form. It is felt that this resulted primarily from the active involvement of the trainees in its development. It has subsequently also been adopted as an educational tool in teaching sessions. It was felt that the improved completion of assessments as a result of use of the standard form outweighed any disadvantages such as reduced autonomy and discretion of the clinician, or the possible sense of complacency that can be induced by forms that merely require boxes to be ticked.

As an audit the study does have limitations. There is a subjective component to the assessment of the information and possible variability between assessors might introduce bias. Frequent consultation between the assessors was used to limit this. Assessors were not masked as to whether the information was obtained prior to or following the introduction of the form, which may further bias their assessment of its completeness. Furthermore, it is also possible that some of the improvement in the completeness of the information occurred because of the increased profile resulting from the audit process itself (Reference O'HareO’Hare, 1995). Finally, the audit does not assess accuracy or other aspects of the quality of the recordings. This has been highlighted previously as a shortcoming of using audit to assess the quality of patient documentation (Reference BlakeyBlakey, 2000).

Overall, this audit emphasises the vital role admission booking plays in the provision of quality care to patients admitted to psychiatric units. Those doctors involved in admitting patients must receive adequate training and supervision to ensure comprehensive information is obtained. This audit suggests that the introduction of a standardised admission form may assist in improving the quality of such information.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.