Members of the LGBT community are descriptively underrepresented in the US Congress. Despite the election of a record high nine openly gay and lesbian legislators to the US House of Representatives in 2020, their membership increased to only 2.1% of the US House (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Gossett, Magni and Reynolds2020).Footnote 1 Moreover, the first openly transgender member of Congress, Sarah McBride (D-DE), was elected in 2024 (Haider-Markel et al. Reference Haider-Markel, Miller, Flores, Lewis, Tadlock and Taylor2017; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Schulenberg, Baldwin and Brettschneider2017). By contrast, some polls show that 8% of Americans identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (Powell Reference Powell2021). The gap between the composition of Congress and society raises questions about whether and to what extent the underrepresentation of LGBT citizens affects the consideration and passage of policy that protects and advances LGBT rights.Footnote 2

This article investigates one important aspect of this topic: whether a legislator’s sexuality affects support for LGBT rights. We study 12 Congresses from 1997 to 2021—a period that witnessed a dramatic increase in the number of LGB legislators as well as an increase in both the quantity of LGBT-related policy considered and public support for LGBT rights. We compile a dataset with measures of legislator and district background characteristics and behavior, totaling 6,425 legislator–Congress observations over 24 years (Bishin and Weller Reference Bishin and Weller2025). We also use Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to compare the behavior of LGB legislators to non-LGB legislators with similar political preferences and from similar legislative districts. Specifically, we examine whether descriptive representatives provide increased policy representation on LGBT issues in the US Congress.

This article investigates one important aspect of this topic: whether a legislator’s sexuality affects support for LGBT rights.

Studies of descriptive representation typically examine the importance of electing legislators who look like or share the same background or experiences as the people they represent (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). To be sure, legislative behavior in the US Congress reflects only one of many ways that descriptive representatives may benefit members of their group and society as a whole. Studies of descriptive representatives demonstrate that in addition to working to achieve policy objectives by passing legislation, they can “represent” through activities such as conducting casework, interceding with the bureaucracy on behalf of constituents, participating in committee hearings or providing bureaucratic oversight, joining caucuses, and preventing legislation that damages their interests (Lowande, Ritchie, and Lauterbach Reference Lowande, Ritchie and Lauterbach2019; Snell Reference Snell, Brettschneider, Burgess and Keating2017; Stout, Tate, and Wilson Reference Stout, Tate and Wilson2021). Descriptive representation also has benefits for constituents that include fostering a greater sense of efficacy and trust, increasing the willingness to contact their representative, enhancing public perception of group members as legitimate participants in the polity, and providing role models for fellow group members (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Gay Reference Gay2002; Tate Reference Tate2001, Reference Tate2003; Wolak Reference Wolak2020). Consequently, we focus on the substantive benefits of descriptive representation as only one important aspect of representation for the LGBT community.

A central question emerging from this research concerns the extent to which descriptive representatives increase substantive representation, or the degree to which they “act for” or on behalf of the people with whom they share these physical, background, or experiential characteristics (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Research finds that some descriptive representatives provide fellow group members increased levels of substantive representation (Stout, Tate, and Wilson Reference Stout, Tate and Wilson2021), whereas others (Wallace Reference Wallace2014) do not. This study examines the extent to which LGB members of Congress are more supportive of LGBT rights than non-LGB members.

Studies that examine the substantive effects of descriptive representation often face a difficult challenge. Due to a series of factors that include structural racism and segregation, legislators’ background characteristics (e.g., race and ethnicity) often are correlated highly with the characteristics of their congressional district, making it difficult to disentangle legislator and district effects on legislator behavior. According to the 2019 American Community Survey, for example, nine of the 10 congressional districts with the largest Black and Latino populations, respectively, are represented by Black and Latino members of Congress. By contrast, none of the 10 districts with the largest LGBT populations is represented by an openly LGB member of Congress. Studying LGB representatives allows us to examine the descriptive–substantive representation link in a context less affected by these challenges. We do this because LGB legislators often are from districts with more variation in their population demographics, which makes it potentially easier to identify the impact of LGB status on behavior.

Due to a series of factors that include structural racism and segregation, legislators’ background characteristics (e.g., race and ethnicity) often are correlated highly with the characteristics of their congressional district, making it difficult to disentangle legislator and district effects on legislator behavior.

EXPECTATIONS

In at least some ways, almost all racial, ethnic, and gendered groups are better served by descriptive legislators (Stout, Tate, and Wilson Reference Stout, Tate and Wilson2021). Research demonstrates that the shared experience of being LGBTQ fosters group identity, which leads to increased political homophily (Proctor Reference Proctor2022). LGB state legislators report working diligently to reflect their background through the issues they prioritize as well as the legislation they introduce (Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2010; Herrick Reference Herrick2009). This research implies the following hypothesis:

LGBT Responsiveness Hypothesis: LGBT legislators are more supportive of LGBT rights than non-LGBT legislators.

DATA AND METHODS

This study is the first to examine whether LGB legislators are more supportive of LGBT rights in the US Congress. Studying LGBT representation is difficult. Public position-taking opportunities on LGBT rights, such as roll-call votes and bill co-sponsorships, seldom arise (Bishin, Freebourn, and Teten Reference Bishin, Freebourn and Teten2020). Furthermore, few openly LGBT members serve in Congress, and measures of constituents’ preferences on the issues before Congress are seldom available, making it difficult to compare constituents’ preferences with legislators’ behavior.Footnote 3 Consequently, few studies examine the link between descriptive and substantive representation of LGBT legislators in the US Congress.

We overcome these challenges by using Human Rights Campaign (HRC) data because it incorporates a wide range of indicators over a long period—which allows us to examine the behavior of the largest number of openly LGB legislators on the widest number of indicators.Footnote 4 In fact, all of the alternative measures we otherwise might use are incorporated into the HRC scores. If these other measures are used alone, they either convey less information or cover a shorter period, making them less valid or reliable than HRC scores for assessing general support for LGBT policy and people. The HRC rates legislators on a scale from 0 to 100. The scores incorporate between five and 16 items, depending on the Congress.

We study the period from 1997 to 2021 because it covers an important era in gay rights in which the number of LGB legislators grew and public support for LGBT issues increased nationally. Moreover, basic measures needed to conduct our analysis became available in this period. Although the HRC began rating legislators in the 101st Congress, the data needed to examine the influence of LGB legislators on policy did not exist in meaningful numbers until 1997 (i.e., the 105th Congress). Previously, there was either no or only one openly LGB member of Congress, and important district-level data, such as reliable estimates of the size of the district-level LGB population, were unavailable.

HRC scores also have limitations. Three primary concerns stand out. First, what counts as support can vary over time because both the social context and the nature of the pro-gay rights coalition changes. HRC scores therefore reflect their perspective on legislators’ support for LGBT rights relative to when the scores were issued. Second, as an index, the meaning of the measures must be interpreted with caution. Often, these measures indicate neither strength nor extremity of issue support but rather consistency of support (Broockman Reference Broockman2016).Footnote 5 Third, the scores and inclusion of items in the HRC measure are almost certainly strategic and designed to influence legislator behavior.Footnote 6

To examine whether LGB legislators are more supportive of LGBT rights than non-LGB legislators, we use CEM to match LGB and non-LGB legislators who are similar in their political behavior and who come from similar districts (Iacus, King, and Porro Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012). Because of potential differences that we could not adjust for statistically, most of our analyses are cross sectional to avoid comparing congressional sessions to one another.

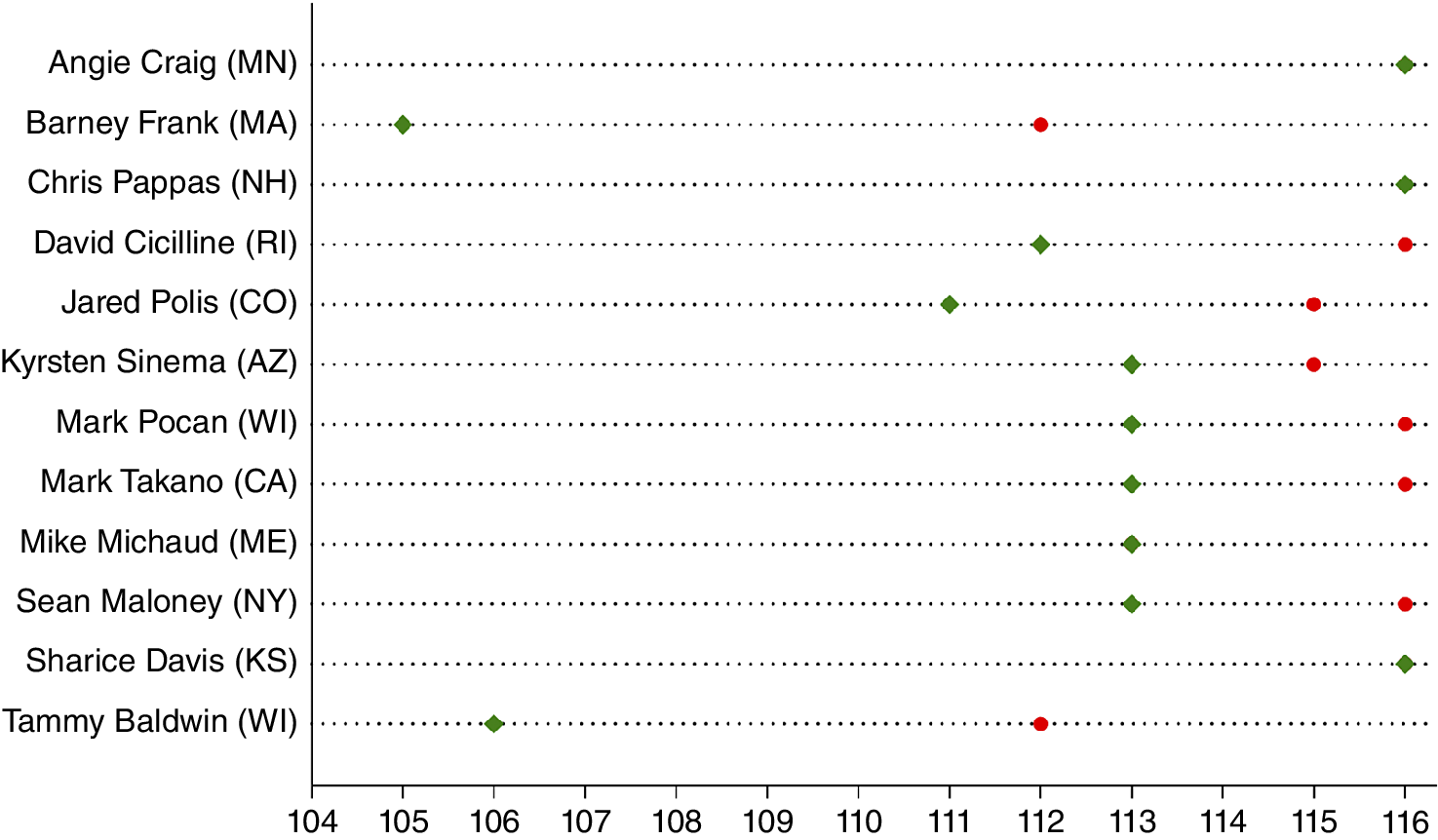

Figure 1 presents the names and tenures of openly LGB House members and when they served in our data, which highlights a difficulty in studying substantive representation provided by LGB House members.Footnote 7 Legislators are listed alphabetically; the diamond symbol indicates the Congress in which they first served and the circle indicates their last. Legislators without a circle next to their name served only in one Congress during the period studied.

Figure 1 Congressional Terms for LGB Members

The results in figure 1 reveal how few openly LGB people have served in Congress. The total number of LGB members who served at any one time is shown by selecting a Congress and then observing which members’ tenure covered that period. Most striking, before the 113th Congress, there never were more than four LGB members—and, most commonly, only two. The small number of members in any one Congress explains the difficulty in studying the behavior of LGB members.

In theory, the ideal identification strategy to estimate the effect of LGB status on behavior would be to randomly assign sexuality to legislators and districts and then observe differences in their behavior; however, doing so is clearly impossible. Instead, we use CEM to create matched LGB and non-LGB legislators who are similar in political ideology and from similar legislative districts.

We begin by identifying key variables on which the LGB and non-LGB legislators will be matched. These are variables thought to be important for explaining legislator behavior and, therefore, for matching to ensure that these characteristics do not explain differences in support for LGBT rights between LGB and non-LGB legislators. The CEM approach is to divide each variable into “bins.” Within each bin, we consider the observations to be substantively similar. In the case of discrete variables such as political party, bins naturally emerged and, in this case, were based on shared party membership (i.e., Democrats and Republicans).

After the bins for all variables are determined, observations are assigned to a stratum based on their pattern of bins (e.g., a Democrat, ideological moderate, from a suburban district). Following the assignment of observations to strata, LGB legislator-districts are matched to non-LGB legislator-districts with identical bin signatures. We then estimate the sample average treatment effect on the treated (SATT) using OLS regression to adjust for any remaining imbalance (i.e., variation within bins) on the matched variables. Matching before OLS regression reduces model dependence of our estimated treatment effect by ensuring that we are not extrapolating beyond the data in our sample.Footnote 8

To implement the CEM algorithm, we focus on variables related to the three primary factors believed to affect legislative behavior: political party, ideological preferences, and constituency interests and preferences (Weller Reference Weller2009).Footnote 9 Specifically, we used the following variables for both matching and regression:Footnote 10

-

• Urban population: percentage of a congressional district classified as urban using US Census data

-

• LGB population: percentage of a congressional district likely to be LGB (Haider-Markel, Joslyn, and Kniss Reference Haider-Markel, Joslyn and Kniss2000)Footnote 11

-

• Ideology: First Dimension of NOMINATE (VoteView)

-

• Democratic presidential vote share: in the most recent election (Almanac of American Politics 2022)Footnote 12

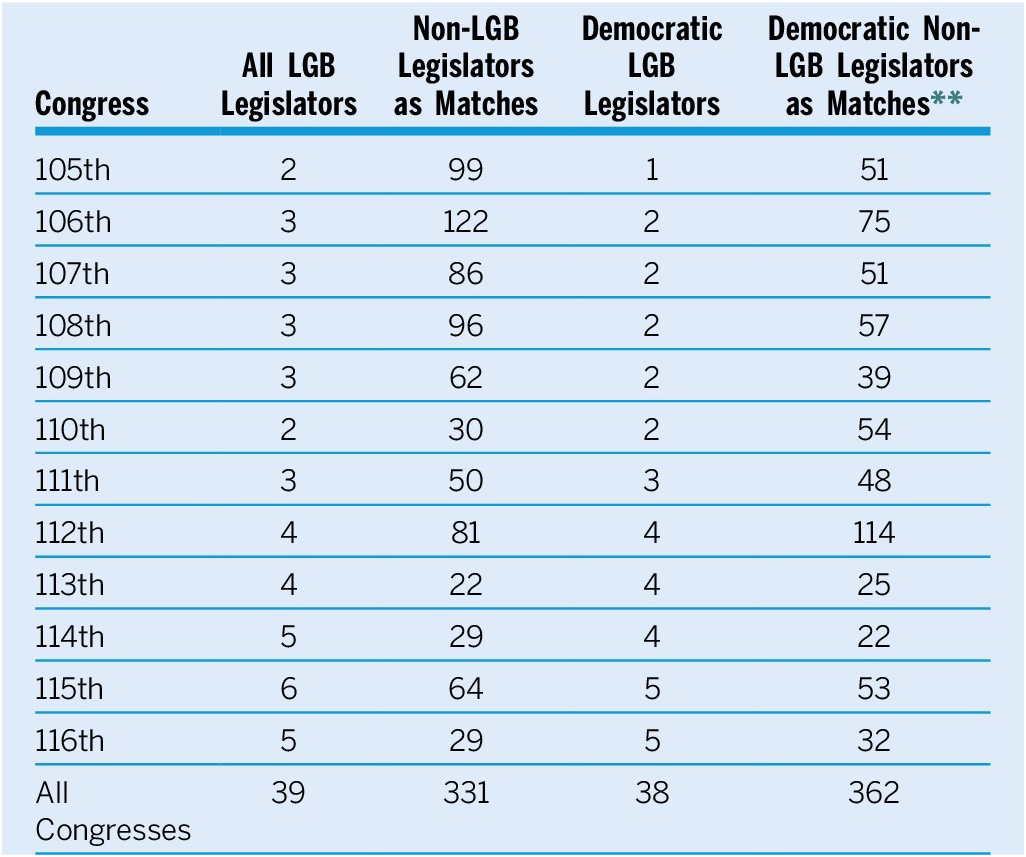

Table 1 indicates the number of matches and reveals that there are very few LGB (and no transgender) legislators in our analysis The total for “All Congresses” includes repeated observations, such that a single LGB legislator serving in the 105th, 106th, and 107th Congresses would count as three LGB legislators.

Table 1 Number of Matched LGB House Members and Matched Non-LGB Legislators by Congress *

Notes:

* The number of matches varies across the columns because although we match within party (i.e., Democrats to Democrats), where legislators fall in the strata for each variable is a function of all of the legislators in the dataset; therefore, the matches vary across the samples. This affects the number of LGB and non-LGB legislators in the estimation sample.

** In some Congresses, we were unable to match some LGB legislators. An important aspect of matching is that it helps to identify even those LGB legislators who are too dissimilar from non-LGB legislators to use in the analysis. Our analyses include only the LGB legislators for whom we could find a suitable match.

RESULTS

The LGBT Responsiveness Hypothesis holds that LGBT legislators are more supportive of LGBT rights than non-LGBT legislators. To test it, we estimate the relationship between LGB status and HRC score using an OLS regression that includes the same control variables used for matching. This accounts for the fact that the matches do not have the exact same score on those variables. In the pooled analysis, we also include fixed effects for each Congress.

We also separately analyze the Democrats to ensure that our conclusions are not driven by the single openly gay Republican legislator who served during this period (i.e., Jim Kolbe, R-AZ). His HRC scores are much higher than the rest of the Republican Caucus.Footnote 13

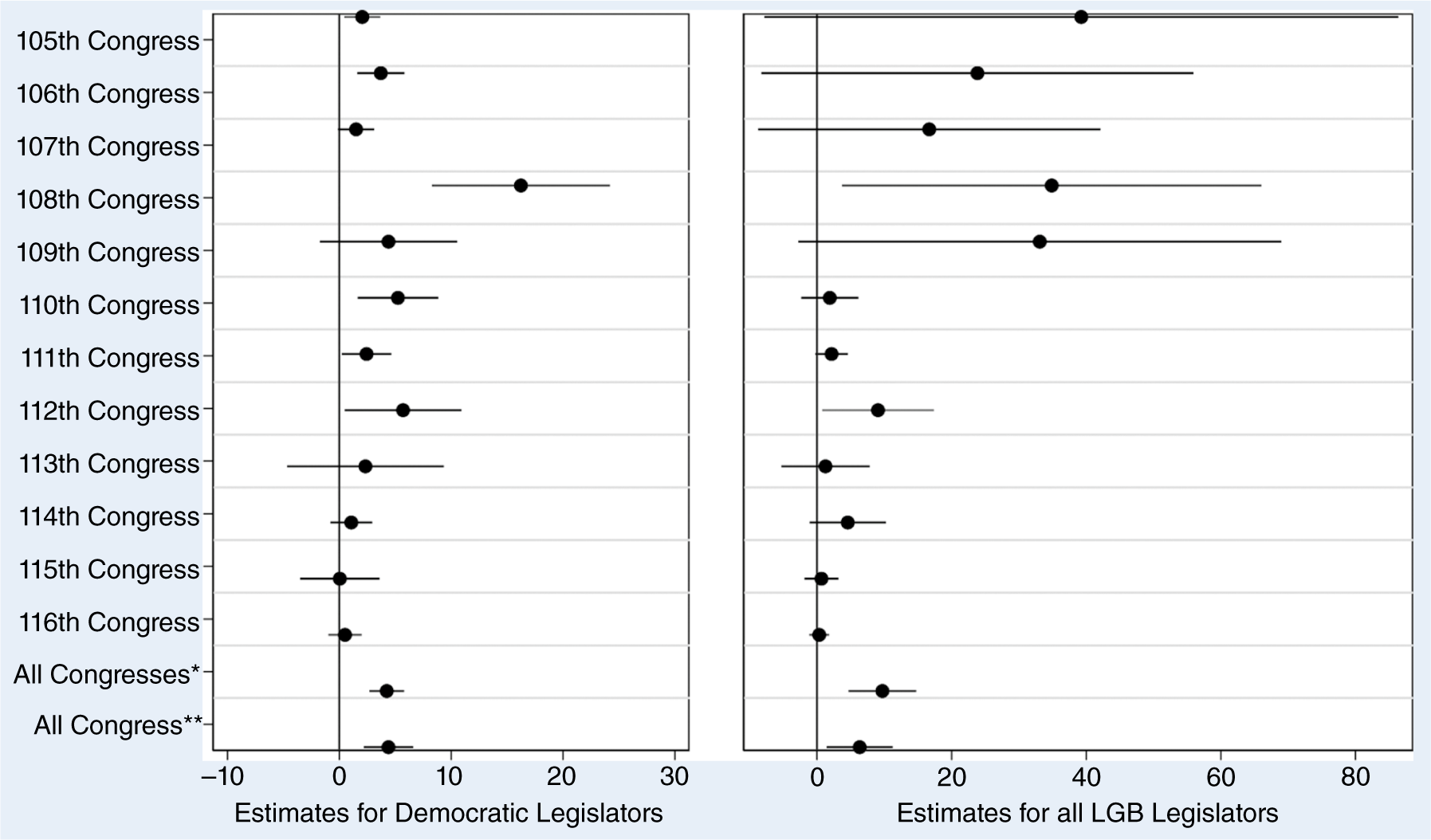

Figure 2 summarizes the coefficients for each Congress and also pooled across Congresses. It presents the coefficient estimate (circle) for the effect of the LGB legislator and the 90% confidence interval (line) around that point for individual Congresses and for the pooled period. Confidence intervals that do not overlap the vertical line at zero are significant at p<0.05 for a one-tailed hypothesis test, which is consistent with our directional hypothesis.

Figure 2 Effect of LGB Status on HRC Scores

Note: The “All Congresses*” estimate does not include district-level LGB population in the matching and OLS regression and therefore includes all Congresses except the 105th and 112th in the estimate. The “All Congresses**” estimate includes district-level LGB population in the matching and OLS regression and therefore includes only those Congresses after the 108th but excludes the 112th Congress due to data availability.

The results displayed on the left side of figure 2 show the estimated relationship between LGB status and HRC score for Democratic legislators.Footnote 14 Whereas every coefficient is positive, those for only four of the Congresses are significantly different than zero. We also estimate positive and significant coefficients for the pooled results (measured both ways). The right side of figure 2 includes all legislators.Footnote 15 The overall pattern of estimates is similar, with uniformly positive estimates for each Congress and for the pooled “All Congress” estimates—both of which are statistically significant. These estimates should be interpreted in the context of our small sample size (especially within each Congress), and with a ceiling effect because the HRC score cannot exceed 100, which makes it difficult to detect effects as HRC scores move close to 100. Among the Democratic legislators, the average HRC score for even the non-LGB legislators in our matched sample was consistently higher than 95, making it difficult for LGB legislators to receive a higher score.Footnote 16

Reviewing the coefficient estimates in figure 2, it appears that the difference between LGBT and non-LGBT legislators declines over time. A likely cause seems to be the increase in the average HRC score among all Democrats. In the 112th Congress, for example, the average HRC score among Democrats was 88; however, in the 113th Congress, it climbed to approximately 96.5—a level that was maintained throughout the rest of the study period. At the same time, the standard deviation was approximately halved, from 23 to approximately 9.5. An increased willingness to elect LGB candidates beginning in 2012, increased support for LGBT rights, and decreased variation in the support among members, is consistent with a political party in which LGBT constituencies appeared fully incorporated in the coalition. There is relatively little disagreement on issues of LGBT politics; therefore, LGBT legislators are unlikely to have higher HRC scores than non-LGBT legislators.Footnote 17

CONCLUSION

This article examines the link between descriptive and substantive representation on LGBT rights from 1997 to 2021 and presents the first evidence that LGB representatives provide greater substantive representation than non-LGB members of Congress with similar political preferences elected from similar districts. We emphasize, however, that whereas the increase in support for LGBT rights by LGB legislators positive in every Congress, it is substantively very small.

This article examines the link between descriptive and substantive representation on LGBT rights from 1997 to 2021 and presents the first evidence that LGB representatives provide greater substantive representation than non-LGB congressional members with similar political preferences elected from similar districts.

Despite a dramatic increase in public support for gay rights during the past two decades and the incorporation of LGBT rights groups into the Democratic Party coalition, recent increases in anti-gay and anti-transgender policy passed in many states highlights the importance of studying representation at the federal level as an important check on state law (Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Freebourn and Teten2020; Flores Reference Flores2014; Taylor, Lewis, and Haider-Markel Reference Taylor, Lewis and Haider-Markel2018). The results suggest that electing LGB legislators over similar non-LGB legislators from similar districts has a small but significant effect on support for LGBT rights. These results depend on comparisons between similar legislators from similar districts. In practice, however, in many races, the choice before voters is not between similar legislators. Replacing a non-LGB legislator with an LGB legislator in those cases may have more significant effects than those reported in this article.

Notably, we examine only one aspect of representation. LGB legislators perform many functions that advance the interests of the LGBTQ community but that are not included in HRC scores or other typically used indicators of legislator behavior (e.g., roll-call votes and co-sponsorship). Like other descriptive representatives, LGB legislators may be more likely to attend hearings or conduct oversight that is relevant to LGBT people, work to prevent discriminatory legislation from getting on the agenda, or work on behalf of LGBT constituents in their districts and help them to navigate federal bureaucracies (Lowande and Proctor Reference Lowande and Proctor2020; Lowande, Ritchie, and Lauterbach 1999). Our empirical approach does not account for different aspects of representation including surrogate representation, service responsiveness, and allocative responsiveness to LGBT constituencies (Eulau and Karps Reference Eulau and Paul D.1977). Nor do we examine the well-documented and important symbolic representation that electing LGBT members may provide to both in- and out-group members by reifying the legitimacy of the group as valued and important members of the polity (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Tate Reference Tate2003). Future research should examine the various ways that descriptive representation can incorporate more fully those who are stigmatized and marginalized along these important but less-well-studied dimensions.

The study of LGBT representation faces challenges that differ somewhat from studying other groups. These challenges may be unappreciated by scholars who are less familiar with LGB politics. By their nature, stigmatized and minoritized groups tend to be physically underrepresented in government, and the gap is particularly acute for openly LGBT officials. Concomitantly, issues important to the LGBTQ community are underconsidered in these public spaces. Many hard-won gay rights (e.g., marriage) remain tenuous due to their dependence on court rulings rather than legislative action (Bishin et al. Reference Bishin, Hayes, Incantalupo and Smith2021). Nevertheless, in many sessions of Congress, legislation enshrining of even the most popular of these rights is not often introduced and, when it is, it seldom makes it to the floor for a vote. The combination of the small number of legislators and the rarity of legislative policy advances creates significant obstacles to studying LGBT politics. Although it is difficult to conduct empirical research in this domain, it nevertheless is an important topic and should not be ignored simply because of the difficulty of making reliable inferences. The methods used in this study—in particular, the use of matching—may provide an option for scholars who are interested in studying the link between descriptive and substantive representation for other underrepresented groups.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525000289.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Minhye Joo and Michelangelo Landgrave for their excellent research assistance. We also thank Andrew Flores and participants in the University of California, Riverside, Mass Behavior workshop for their helpful comments and feedback.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/AZLRMG.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.