Introduction

Citizens’ health services utilization is an indicator of human development and the wealth of countries, while access to and use of health care determine the state of health (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014). Access to quality services to promote and maintain health, prevention, and management of diseases, reduction of premature mortality, and health access equity are essential principles for all, yet access to health services is in most countries (Harouni et al., Reference Harouni, Sajjadi, Rafiey, Mirabzadeh, Vaez-Mahdavi and Kamal2017). More than one billion people worldwide do not have access to healthcare services (SoleimanvandiAzar et al., Reference SoleimanvandiAzar, Kamal, Sajjadi, Harouni, Karimi, Djalalinia and Forouzan2020), and more than a third of the world’s population cannot access health services for social, economic, and cultural reasons (Bazie and Adimassie, Reference Bazie and Adimassie2017).

As part of the Sustainable Development Goals, Member States of the United Nations have agreed to achieve Universal Health Coverage by 2030 because access to health services as a human right and one of the mechanisms of the health system (SoleimanvandiAzar et al., Reference SoleimanvandiAzar, Kamal, Sajjadi, Ardakani, Forouzan, Karimi and Harouni2021) ensures a healthy life and promotes well-being for all (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021; Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020; Schmidt-Traub et al., Reference Schmidt-Traub, Kroll, Teksoz, Durand-Delacre and Sachs2017). On the other hand, lack of access to health services can have adverse effects on people’s health, especially vulnerable and deprived individuals. Unequal use of health services has been reported among the poor (Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2014; Murphy, Reference Murphy2016), and this inequality is common among women in countries with weak healthcare systems (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020). Access to health care and health service utilization for many people, especially vulnerable groups, including women, the elderly, and children, is a serious challenge for the health systems of developing countries (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021).

Women are the mainstay of family and society, and women’s health has always been one of the main concerns of the World Health Organization (Organization W.H., 2009). Women’s health affects the health of all family members (Dominic et al., Reference Dominic, Ogundipe and Ogundipe2019). Studies have shown that women need to receive more health services (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017) than men due to fertility and childbirth (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020).

Women often make household decisions about utilizing health services for themselves and their families, and this can affect their health. Inequality in access to health services among women is a major challenge in low-income countries (Ogundipe et al., Reference Ogundipe, Olurinola and Ogundipe2016). Inadequate health services utilization is associated with a high mortality rate in women of childbearing age (Dominic et al., Reference Dominic, Ogundipe and Ogundipe2019; Essendi et al., Reference Essendi, Mills and Fotso2011; Zere et al., Reference Zere, Tumusiime, Walker, Kirigia, Mwikisa and Mbeeli2010). In most societies, women, in general, have less wealth than men, while they guarantee reproduction and economic activity and have more productivity. Women in poor countries are less fed and educated, are employed in low-income jobs, have low job security, and confront more inequality in education, employment, and income (Logie, Reference Logie2012; Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Jansen, Williams, Cáceres, Motta, Odhiambo, Eleveld and Mannell2019). Also, social and gender discrimination has caused women to have unequal access to health services (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017).

Many efforts have been made to improve access to healthcare services in low-income societies, such as reducing out-of-pocket payments, increasing the number of clinics, and improving education and transportation systems. However, inadequate access to health care has been documented in various studies (Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013). Utilizing health services is associated with a reduction in mortality and diseases rate (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014). Research has shown that several factors shape the health services utilization pattern (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016). Inequality in health services utilization among women may be due to differences in access to health care services among women and also to differences in women’s demographic characteristics and socioeconomic status (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014). Although studies have shown that women utilize more health services than men, our knowledge of the factors associated with health services utilization among women is insufficient (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017). As a result, the aim of this study was to identify the determinants of women’s OHSU. It also sought to provide insight into the factors affecting the use of outpatient health care services among women, as well as to better plan and design interventions to improve access and use of health care services by women.

Material and methods

This scoping review was conducted on studies related to OHSU among women, based on the scoping review framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). This study has been approved by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with the code (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.546(. In this study, authors tried to methodological reports based on the checklist developed by Tricco et al., (PRISMA extension reporting for scoping reviews) (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018).

Eligibility criteria

Research question

What is known from the existing literature about the factors correlated with OHSU among women?

Identifying Relevant Studies

This review was conducted on studies published between 2010 and 2023 (all search was done on 20 January 2023).

Information sources

Electronic databases

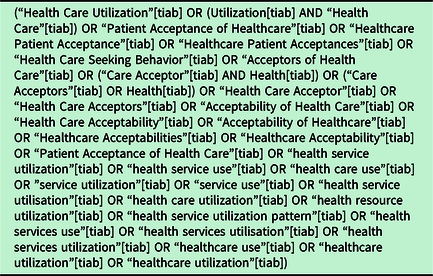

The databases such as Web of Science, MEDLINE (PubMed), Scopus, Wiley library, Proquest, and Google scholar were searched. Selected keywords and their equivalents were used to search for articles in each database (Table 1).

Table 1. Search strategy based on PubMed

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

All English language studies, including quantitative, observational, cross-sectional, secondary, and longitudinal studies without geographical restrictions that examined the OHSU among women were entered into the review. The aim of this study was to investigate OHSU among women, which included any referral and utilization of public and private health services by women over 15 years of age to meet their health needs. The study specifically focused on OHSU as a binary outcome (i.e. utilized vs. non-utilized). To be eligible for inclusion, the selected studies must have assessed the association between OHSU and any other factors (determinants).

Exclusion criteria

Studies that reported the use of informal health services, complementary medicine, or services provided for specific groups other than women (children, veterans, military personnel, prisoners, immigrants, nursing home residents, students, women with specific diseases such as cancer, MS, etc.), as well as the articles on inpatient health services utilization, were excluded from the study. Also, review articles, letters to the editors, and non-English language, interventional, theoretical, and irrelevant studies with low-quality methodology were excluded from the study. For studies that had used the same data sources, those that had used more data, and had better quality were selected.

Selection of studies

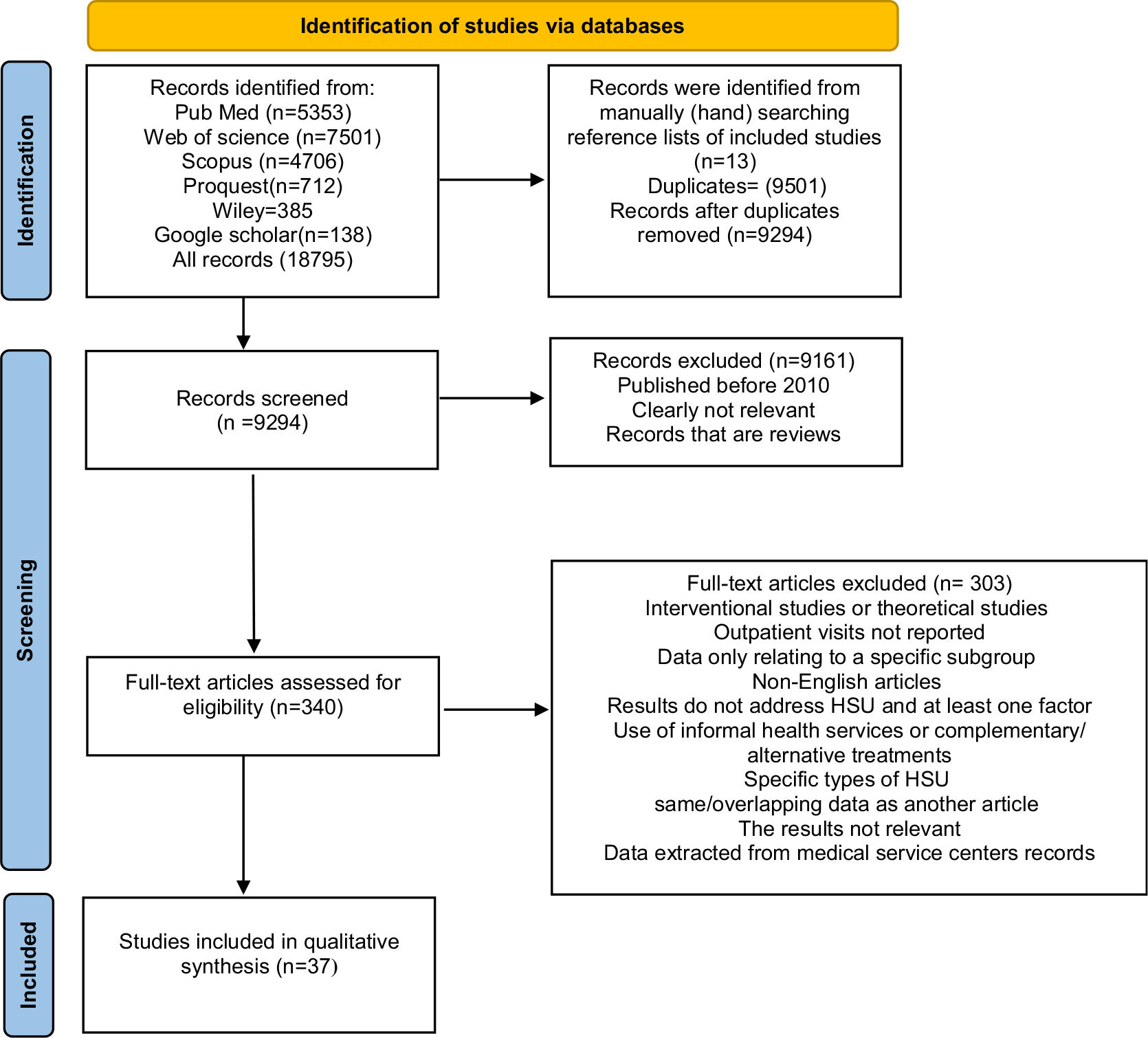

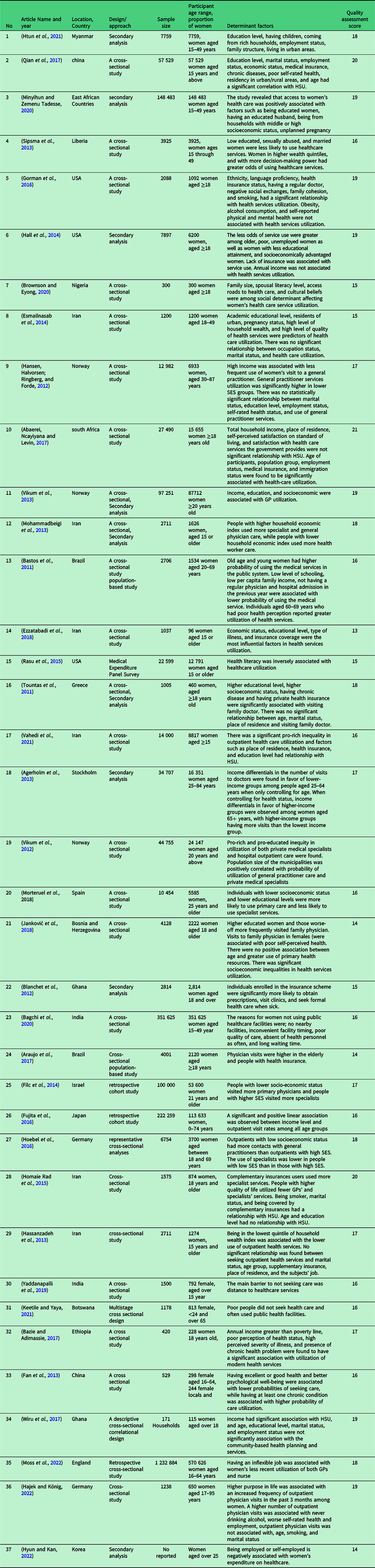

After searching scientific databases, 18 795 articles were obtained. After removing duplicates (9501) and screening by titles and abstracts (9294), 340 articles were obtained. Based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the full text of 340 articles was screened by two authors (NSA, SEK) independently (190 were eliminated), and the quality assessment of 150 remained articles was evaluated by two authors (NSA, SEK) independently, based on the STROBE checklist. Controversial studies were solved by the third person (BZ). Finally, 37 articles were included in this review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA chart (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018). STROBE guideline was used to aid the authors in ensuring a high-quality presentation of the observational studies such as cohort, a case–control, or a cross-sectional study (Cuschieri, Reference Cuschieri2019). In the quality assessment, the articles that scored below 11 were eliminated. Those scored between 11 and 16 (appropriate), and articles that scored more than 16 were evaluated as good quality and included in the final review synthesis (Vandenbroucke et al., Reference Vandenbroucke, Von Elm, Altman, Gøtzsche, Mulrow, Pocock, Poole, Schlesselman and Egger2009; Von Elm et al., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007). By using an Excel sheet, data such as author’s name, year of publication, place of study, design, and type of study, the sample size of the study and factors related to the utilization of outpatient health services among women were extracted from the articles (Table 2).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart showing a selection of studies

Table 2. Factors that facilitate and inhibit the use of outpatient health services among women

Data analysis

Considering the method of scoping review for examining the factors associated with outpatient HSU among women, a narrative synthesis was considered to be the most appropriate method of data analysis (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). The authors systematically combined the results based on the use of words, text, and findings of the articles to explain the correlated factors of OHSU.

Findings

We found 18 795 publications in the initial search. After removing duplicates and excluding noneligible articles, 340 were read in full text, of which 37 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The total number of participants ranged from 96 to 351 625. In general, the participants comprised women aged 15 and over (15–95). The most common design of articles was cross-sectional (n = 29, 87%), 4 were secondary analysis (10%), 2 were cohort studies, and was a panel survey. Asia was the most common country of origin (n = 13, 35%), Europe (n = 12, 32%), Africa (n = 7, 18%), and the USA (N = 5, 13%). Studies defined HSU as a dichotomous-dependent variable. Thus, less than 12 months HSU were used as HSU indices prior to data collection (the interview), whether there was a self-reported need for outpatient care services, including primary or secondary health services, and whether the respondents had contacts with (visit) health care professionals (e.g., general practitioners and specialists) and received medication in the preceding 2 weeks. The results of this review are summarized in Table 2.

Age

In some studies, aging was associated with a reduced chance of utilizing outpatient health services (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014), and in others, aging was associated with an increased chance of utilizing health services (Abaerei et al., Reference Abaerei, Ncayiyana and Levin2017; Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Silva, Galvao and Pereira2017; Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017). Also, some studies did not find a relationship between age and health services utilization (Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022; Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011; Wiru et al., Reference Wiru, Kumi-Kyereme, Mahama, Amenga-Etego and Owusu-Agyei2017).

Marital status

According to some studies, the use of outpatient services in widows and divorced women was higher than in other women (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017; Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013). Some research (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014; André Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011; Wiru et al., Reference Wiru, Kumi-Kyereme, Mahama, Amenga-Etego and Owusu-Agyei2017) did not discover a significant relationship between marital status and OHSU.

Level of education

Findings showed that women with higher education utilized more health services (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Bjørngaard, Westin and Krokstad2013; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Krokstad and Westin2012), while in other investigations, lower education was associated with less use of health services (Ezzatabadi et al., Reference Ezzatabadi, Khosravi, Bahrami and Rafiei2018; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013; Vahedi et al., Reference Vahedi, Ramezani-Doroh, Shamsadiny and Rezapour2021). Some studies also did not report a significant relationship between education level and OHSU (Abaerei et al., Reference Abaerei, Ncayiyana and Levin2017; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Wiru et al., Reference Wiru, Kumi-Kyereme, Mahama, Amenga-Etego and Owusu-Agyei2017). In the study of Qian et al. (Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017), the rate of OHSU in the last 2 weeks was higher in illiterate women than in women with higher education, and this rate decreased with increasing educational levels.

Spouse education

Higher education of the spouse increased the chances of health services utilization in women (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020), and lower education of spouses was one of the barriers to the use of health services among women (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020).

Rape experiences

In the study of Sipsma et al. (Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013), women who experienced sexual harassment were less likely to seek medical services.

Place of residence (urban/rural)

The findings of the reviewed studies showed that residing in urban areas increased the use of health services among women (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014; Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Krokstad and Westin2012). Rural living was associated with fewer health services utilization according to some investigations (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020; Vahedi et al., Reference Vahedi, Ramezani-Doroh, Shamsadiny and Rezapour2021). Some studies also did not report differences between living in urban or rural areas and the use of health services (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011).

The number of children

Having fewer children was associated with more use of health services in one study (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021).

Employment status

A review of studies showed that having a job could increase the use of health services (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021). While two studies showed that having a job was associated with a decrease in the use of health services (Abaerei et al., Reference Abaerei, Ncayiyana and Levin2017; Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022; Hyun and Kan, Reference Hyun and Kan2022), but in the study by Qian et al. (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017). The rate of OHSU in the last 2 weeks was higher among unemployed women. In other studies, no relationship was found between employment status and access to health services (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013; Wiru et al., Reference Wiru, Kumi-Kyereme, Mahama, Amenga-Etego and Owusu-Agyei2017); having an inflexible job was associated with women’s less recent utilization of both GPs and nurses’ services (Moss et al., Reference Moss, Munford and Sutton2022).

Socio-economic status

Findings from other studies showed that women with higher socioeconomic status were more likely to seek healthcare services than their poorer counterparts (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020; Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013). Some studies showed that poor women use health services less (Ezzatabadi et al., Reference Ezzatabadi, Khosravi, Bahrami and Rafiei2018; Fujita et al., Reference Fujita, Sato, Nagashima, Takahashi and Hata2016; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Keetile and Yaya, Reference Keetile and Yaya2021). In Qian et al. (Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017) study, the rate of outpatient services utilization in the past 2 weeks was not different in women with different socioeconomic statuses. A significant relationship was also found between higher socioeconomic status and the use of GP and family physician services in other studies (Fujita et al., Reference Fujita, Sato, Nagashima, Takahashi and Hata2016; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Bjørngaard, Westin and Krokstad2013). Also, higher socioeconomic status in other studies was indirectly correlated to the use of general practitioners’ services, but it was directly correlated to the utilization of health services provided by specialist physicians (Filc et al., Reference Filc, Davidovich, Novack and Balicer2014; Hoebel et al., Reference Hoebel, Rattay, Prutz, Rommel and Lampert2016; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Mohammadbeigi et al., Reference Mohammadbeigi, Hassanzadeh, Eshrati and Rezaianzadeh2013; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017). This is while people with low socioeconomic status used the services of general practitioners more often (Filc et al., Reference Filc, Davidovich, Novack and Balicer2014; Hoebel et al., Reference Hoebel, Rattay, Prutz, Rommel and Lampert2016; Keetile and Yaya, Reference Keetile and Yaya2021).

Income level

In a study by Hall and colleagues, no significant relationship was found between annual income and health services utilization (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014). In other studies, a relationship was found between increased income and less use of GP services in upper socioeconomic classes (Agerholm et al., Reference Agerholm, Bruce, BurstrÃm and Ponce Leon2013; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Bjørngaard, Westin and Krokstad2013), and more use of GP services in lower socioeconomic classes (Agerholm et al., Reference Agerholm, Bruce, BurstrÃm and Ponce Leon2013; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017). Some studies showed that women with low per capita incomes used more public health services than those with higher per capita incomes (Agerholm et al., Reference Agerholm, Bruce, BurstrÃm and Ponce Leon2013; Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Bazie and Adimassie, Reference Bazie and Adimassie2017), as well as those with higher incomes used more private specialized services (Agerholm et al., Reference Agerholm, Bruce, BurstrÃm and Ponce Leon2013; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017; Vikum et al., Reference Vikum, Krokstad and Westin2012; Wiru et al., Reference Wiru, Kumi-Kyereme, Mahama, Amenga-Etego and Owusu-Agyei2017).

Family structure

One study found that families with more family members had better chances of utilizing health care services (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021). However, another study showed that a larger number of family members reduced the chances of health services utilization (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020).

Having insurance

Studies showed that having health insurance was associated with higher use of health services (Abaerei et al., Reference Abaerei, Ncayiyana and Levin2017; Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Silva, Galvao and Pereira2017; Blanchet et al., Reference Blanchet, Fink and Osei-Akoto2012; Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Mohammadbeigi et al., Reference Mohammadbeigi, Hassanzadeh, Eshrati and Rezaianzadeh2013; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011), and on the other hand, lack of health insurance was therefore connected with lower use of health services (Ezzatabadi et al., Reference Ezzatabadi, Khosravi, Bahrami and Rafiei2018; Vahedi et al., Reference Vahedi, Ramezani-Doroh, Shamsadiny and Rezapour2021). In one study, health insurance was not associated with HSU (André Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022).

Having a chronic illness

Some studies reported that women with chronic diseases used more health services than others (Bazie and Adimassie, Reference Bazie and Adimassie2017; Ezzatabadi et al., Reference Ezzatabadi, Khosravi, Bahrami and Rafiei2018; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wen, Jin and Wang2013; Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017; Tountas et al., Reference Tountas, Oikonomou, Pallikarona, Dimitrakaki, Tzavara, Souliotis, Anargiros, Pappa, Kontodimopoulos and Niakas2011).

Health status

Women who reported poor health status were more likely to use health services (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Bazie and Adimassie, Reference Bazie and Adimassie2017; Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Šiljak, Erić, Marinković and Janković2018; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017). According to some studies, there is no connection at all between health condition and the use of GP services (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012). Other studies showed that better health status was associated with less health services utilization (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Wen, Jin and Wang2013).

Decision-making power

In the study of Sipsma et al. (Sipsma et al., Reference Sipsma, Callands, Bradley, Harris, Johnson and Hansen2013), women with higher decision-making power in the family were more likely to visit medical centers.

Ethnicity

The ethnic minority was associated with less HSU (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016). In some studies, white women used health services more than colored women (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016).

Language

Women’s lack of familiarity with the official language of the country in which they resided or needed health services was reported as a barrier to using health services (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016).

Smoking

Smoking was linked in some studies to increased use of health facilities (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016). In some other studies, a negative relationship was observed between smoking and the use of health services (Homaie Rad et al., Reference Homaie Rad, Ghaisi, Arefnezhad and Bayati2015). Smoking was not linked to HSU in one research (Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022).

Social cohesion

Health services are utilized more in societies with more social cohesion (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016) and less in societies with negative social relationships.

Having a regular physician

Women who had a regular physician, such as a family doctor, were more likely to use health services, according to some research (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016), and women without a regular physician were less likely to use public health services (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011).

According to some studies, women who had a regular physician, such as a family medicine, were more likely to utilize health services (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016), and women who did not have a regular physician were less likely to use public health services (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011).

Unplanned pregnancy

According to several studies, unplanned pregnancy was a barrier to utilizing health services (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020), and a number of studies have reported a relationship between pregnancy and increased use of health services (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014).

Road accesses

Road access, travel time to medical facilities (Yaddanapalli et al., Reference Yaddanapalli, Srinivas, Simha, Devaki, Viswanath, Pachava and Chandu2019), and the expense of transit have all been identified as major obstacles to HSU for women in a number of studies (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020).

A number of studies have reported road access (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020), distance to health care centers, and transportation costs as significant barriers to HSU among women (Yaddanapalli et al., Reference Yaddanapalli, Srinivas, Simha, Devaki, Viswanath, Pachava and Chandu2019).

Cultural beliefs

Cultural beliefs, such as mistrust of some health services, like family planning services, were seen as obstacles to the use of health services in some cultures, particularly in some African nations (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020).

Quality of services

Reviewed studies showed that, if recipients of health services perceive them as desirable and high-quality services, they will use them more (Esmailnasab et al., Reference Esmailnasab, Hassanzadeh, Rezaeian and Barkhordari2014). Also, the lack of health care centers near the place of residence, inadequate health services timing, poor quality of health services, absence of healthcare personnel, and the long waiting time to receive services were other obstacles to the use of health services (Bagchi et al., Reference Bagchi, Das, Dawad and Dalal2020).

Alcohol consumption

No association was found between alcohol consumption and health services utilization in some studies (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016). A higher number of outpatient physician visits was associated with never drinking alcohol which was reported in André Hajek & König’s study (Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022).

Obesity

There was no relationship between obesity and OHSU (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016).

Facilities in the place of residence

Studies have shown that the more affluent the place of residence, the more health services utilization would be for people living in these areas (Mohammadbeigi et al., Reference Mohammadbeigi, Hassanzadeh, Eshrati and Rezaianzadeh2013). Some studies also did not find a relationship between the facilities of the place of residence and the use of health services (Hassanzadeh et al., Reference Hassanzadeh, Mohammadbeigi, Eshrati, Rezaianzadeh and Rajaeefard2013).

History of hospitalization

Bastos et al. (Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011) reported that women with a previous history of hospitalization were less likely to use public health services (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011).

Health literacy

According to Rasu et al. (Reference Rasu, Bawa, Suminski, Snella and Warady2015), women with a low level of health literacy were using more health services than their counterparts (Rasu et al., Reference Rasu, Bawa, Suminski, Snella and Warady2015).

Having a purpose in life

Having a higher purpose in life was associated with an increased frequency of outpatient physician visits in the past 3 months among women (Hajek and König, Reference Hajek and König2022).

Discussion

Women, especially in less developed countries, are minorities due to cultural and social norms and have little power to make decisions about their health issues, and also in most countries, they have difficulty accessing healthcare services (Htun et al., Reference Htun, Hnin and Khaing2021).

The findings of the reviewed studies showed that in general, with increasing age, the utilization of health services increases, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Rattay et al., Reference Rattay, Butschalowsky, Rommel, Prütz, Jordan, Nowossadeck and Domanska2013). Previous studies have shown that aging is correlated with more use of health services (Gisele Alsina Nader Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Capilheira and Santos, Reference Capilheira and Santos2006), so it can be told that aging is a contributing factor to more health services utilization due to physical mobility problems and increasing chronic diseases. The extensive and free coverage of health care services in some nations may be another factor in older people’s greater use of health services. However, some studies’ results revealed that aging was linked to a decline in the use of preventive services. In this sense, it can be said that getting older is linked to a decline in revenue and the capacity to pay for health care expenses. The danger of sexually transmitted diseases increases with age, and fertility declines as well. As a result, although more proof is required to back up this assertion, it is likely to result in a decrease in the use of preventive services.

The findings of studies that examined the relationship between educational level and the use of health services are contradictory. In general, it can be said that a higher educational level is associated with more health services utilization, especially visiting specialists, and women with lower education use health services less than educated women, but we found that less-educated women used services provided by general practitioners and the public health system more than educated women. As studies have pointed out, it seems that more health services utilization by less-educated women may be due to the high incidence of common diseases in this group, especially in rural areas (Li and Chen, Reference Li and Chen2005). According to studies, women with lower levels of education have lower socioeconomic status and are more vulnerable to diseases (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Andrianopoulos, Cleland, Crawford and Ball2013). Educational level is not only the basis for assessing women’s growth and social participation but also a significant indicator of women’s socioeconomic status. In general, it can be said that more education gives women more knowledge and sources of income and make it possible for them to use more health services (Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse, Reference Minyihun and Zemenu Tadesse2020).

The review of studies revealed inconsistent results on the relationship between marital status and health services utilization. The present study showed that widows and divorced women used more health services than married women. In this regard, it can be said that being divorced or widowed has a negative effect on women’s health. This effect leads to more use of health services by them, as indicated in some studies. This finding, however, is in contrast with the results of previous studies, which have shown that married people use more health services (Girma et al., Reference Girma, Jira and Girma2011). Therefore, the hypothesis that married women seek more health services under the influence of those around them seems unbelievable.

Although employment and related income seem to have a positive effect on the HSU among women, the contradictory findings of the present review regarding the more use of health services by unemployed women can be justified by the fact that it is generally accepted that unemployment has a negative effect on an individual’s health (Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017), and unemployed individuals may become unemployed because of illness, so they need more health services. In this review, several studies have shown that employed women use health service less frequently. Being employed and working can have a positive effect on health if working conditions are favorable (Urtasun and Nuñez, Reference Urtasun and Nuñez2018). This explains why working and employed women are less likely to utilize health services.

The review of the studies showed that having more children prevented women from using health services (Brownson and Eyong, Reference Brownson and Eyong2020). Previous studies have shown that having more children, especially children under 5 years of age, makes it difficult for women to visit and utilize health services (Halwindi et al., Reference Halwindi, Siziya, Magnussen and Olsen2013). It seems that having more family members and, as a result, more responsibilities towards them, such as cooking, cleaning the house, and taking care of children causes women to care less about their health status and not utilize health services when needed. This seems to be partly related to the insufficient income of large families.

According to our findings, socioeconomic status in most of the reviewed studies had the greatest effect on the use of health services by women, and this finding is consistent with the results of other studies (Annan et al., Reference Annan, Donald, Goldstein, Martinez and Koolwal2021; Fagbamigbe and Idemudia, Reference Fagbamigbe and Idemudia2017; Hoebel et al., Reference Hoebel, Rattay, Prutz, Rommel and Lampert2016; Pons-Duran et al., Reference Pons-Duran, Lucas, Narayan, Dabalen and Menéndez2019). Various studies have also documented inequality in the use of health services in favor of the rich (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Zhou, Yan, Gao, Wang, Yang, Xu and Li2017). Higher levels of socioeconomic status and wealth were important factors in the use of health services in most studies, and the rich were more able and willing to pay for those services (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012). Previous studies have shown that people with low socioeconomic status are more likely to be affected by physical and mental health hazards and are more in need of services provided by health care systems (Hoebel et al., Reference Hoebel, Rattay, Prutz, Rommel and Lampert2016). Also, living in poverty and disadvantaged region is associated with increased health care needs (Kirby and Kaneda, Reference Kirby and Kaneda2005), and even more use of health care in these people is due to their unhealthy lifestyle, which puts them at more risk of diseases (Limpuangthip et al., Reference Limpuangthip, Purnaveja and Somkotra2019).

The results of the present study showed that, by increasing income, the use of GP services decreased. The results of international studies in most high-income countries also show a consistent pattern that GP services utilization is in favor of the poor, while specialized outpatient services are mainly used by people with higher incomes (Van Doorslaer et al., Reference Van Doorslaer, Masseria and Koolman2006). This phenomenon is more pronounced in areas where private health insurance is common and private specialists cover a significant portion of existing health services (Doorslaer et al., Reference Doorslaer, Koolman and Jones2004). In low- and middle-income countries, the use of health services provided by general practitioners and the use of specialized outpatient care is generally lower among the poor (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Halvorsen, Ringberg and Forde2012; Janković et al., Reference Janković, Simić and Marinković2010). This may be due to problems with the use of public health services such as long queues and a lack of an adequate number of specialists in the public centers, but higher-income individuals have easy access to specialists in the private sector. Thus, policymakers need to pay attention to increasing the number of physicians, particularly experts in the public sector and marginalized areas, in order to provide easy access to high-quality health services for the poor. Because the existence and use of public health services are associated with better access and reduced inequality in access to health services for disadvantaged groups (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Fang, Liu, Yuan and Xu2015; Narain et al., Reference Narain, Bitler, Ponce, Kominski and Ettner2017).

The results of this study, in line with other studies, showed that those who described their health status as poor were using health services more than others (George et al., Reference George, Heng, Molina, Wong, Lin and Cheah2012; Janko Janković et al., Reference Janković, Simić and Marinković2010). It can be said that these people often have lower incomes and lower education (Rattay et al., Reference Rattay, Butschalowsky, Rommel, Prütz, Jordan, Nowossadeck and Domanska2013), and for reasons such as having unhealthy nutrition and lifestyle and not using preventive services, they have poorer health status and, as a result, need to utilize more health services.

Chronic diseases are often caused by unhealthy living conditions (Solhi et al., Reference Solhi, Azar, Abolghasemi, Maheri, Irandoost and Khalili2020). This study showed that women with chronic diseases used more health services. It is not surprising that people with chronic diseases do not have any choice but to follow their treatment and utilize related health services, which is consistent with other studies (Bazie and Adimassie, Reference Bazie and Adimassie2017; Girma et al., Reference Girma, Jira and Girma2011).

Our study’s results, which are consistent with those of other studies, indicated that living in rural areas was associated with less use of health services (Bhatt and Bathija, Reference Bhatt and Bathija2018; Mekonnen et al., Reference Mekonnen, Dune and Perz2019; Tsawe and Susuman, Reference Tsawe and Susuman2014). Other studies have shown that the use of health services by urban dwellers is more than in rural ones (Fields et al., Reference Fields, Bell, Moyce and Bigbee2015; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Xie, Wu, Zhang, Cheng, Tao and Quan2020; Sözmen and Ünal, Reference Sözmen and Ünal2016). In this regard, it can be said that living in rural areas can reduce access to health services due to factors such as a shortage of health care centers and long distance to health care centers compared to cities. Rural dwellers also have less access to secondary-level health services such as hospitals due to their lower ability to pay for the services compared to urban dwellers. Finally, it can be said that the distribution of specialists is such that they are mostly concentrated in urban areas. This can be the reason for the different use of health services between urban and rural residents.

The present investigation’s findings, in line with other studies, showed that unplanned pregnancy was associated with less use of health services (Haddrill et al., Reference Haddrill, Jones, Mitchell and Anumba2014; Sakeah et al., Reference Sakeah, Okawa, Rexford Oduro, Shibanuma, Ansah, Kikuchi, Debpuur, Gyapong, Owusu-Agyei, Williams, Debpuur, Yeji, Kukula, Enuameh, Asare, Agyekum, Addai, Sarpong, Adjei, Tawiah, Yasuoka, Nanishi, Jimba and Hodgson2017). This is perhaps due to the low literacy and socioeconomic status of these mothers.

Smoking and health services utilization were also found to be contradictory in our study. It is expected that smokers will face more health problems, thus seeking more health services. Other studies have shown that smokers are more likely to seek health services because they are concerned about their health (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Rankin, Stewart and Oka2008; Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016).

More health services utilization was associated with higher social cohesion and family relationships in the present study. Social support is an empowering factor at HSU, so it seems that a high level of family cohesion and strong social networks encourage and facilitate the use of health services (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016).

Language restrictions were associated with lower health services utilization in the present review. In this regard, it can be said that not being familiar with the official language of the country is one of the considerable barriers to communicating with health care providers. Consistent with our findings, other studies have shown that ethnic minorities, especially colored women and those who are less familiar with the official language like immigrants, experience lower use of health services (Blendon et al., Reference Blendon, Buhr, Cassidy, Perez, Hunt, Fleischfresser, Benson and Herrmann2007; Dias et al., Reference Dias, Gama, Cortes and de Sousa2011; Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Wade and Solazzo2016; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dalton and Johnson2014).

The present study’s most significant finding is that people’s perception of health services’ quality was one of the factors which was associated with a higher chance of health services utilization. It seems that service providers, in addition to providing desirable and qualified services, need to be careful in dealing with patients and communicating with them.

Although alcohol consumption was expected to increase health services utilization due to its impact on physical and mental health, our study found no association between alcohol consumption and HSU. However, previous studies have found that not consuming alcohol can be associated with reduced use of medical and dental services (Limpuangthip et al., Reference Limpuangthip, Purnaveja and Somkotra2019; SoleimanvandiAzar et al., Reference SoleimanvandiAzar, Kamal, Sajjadi, Ardakani, Forouzan, Karimi and Harouni2021).

In this study, we did not find a correlation between obesity and the use of health services. Being overweight or obese due to a lack of knowledge, inadequate nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle (Zokaei et al., Reference Zokaei, Ziapour, Khanghahi, Lebni, Irandoost, Toghroli, Mehedi, Foroughinia and Chaboksavar2020) can lead to low health status. As a result, it can increase the need to utilize more health services. So, due to the lack of evidence, it is necessary for future studies to examine the use of health services among obese people and alcohol users.

As expected, the results of the present study indicate that having insurance in any form, whether public or private, could have a positive effect on more use of health services (Abaerei et al., Reference Abaerei, Ncayiyana and Levin2017). Lack of insurance is the main barrier to the use of health services, especially among poor and deprived groups (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Goudge, Ataguba, McIntyre, Nxumalo, Jikwana and Chersich2011).

In line with earlier studies (Gisele Alsina Nader Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Duca, Hallal and Santos2011; Mendoza-Sassi and Béria, Reference Mendoza-Sassi and Béria2003), the current review showed that having a regular physician such as a family doctor was associated with increased use of health services.

Contrary to our expectations, one study found that people with low health literacy utilized more health services. Although more evidence is needed to support this finding, the conclusion can be justified by the fact that people with low health literacy often use more health services due to factors such as unhealthy diet and lifestyle, being more exposed to risk factors, and having more underlying diseases. It is also possible that people with a higher level of health literacy use more preventive and self-management services, so their use of health services is less. In any case, this finding is a warning signal for policymakers to design interventions to increase individuals’ health literacy and facilitate communication between people and health service providers.

Utilization of health services is the outcome of interactions between those in need of health services and the supporting apparatus of the health care system. In agreement with this finding, other studies have revealed that despite some women’s favorable socioeconomic circumstances, they were using fewer health services because of the subpar quality of those services, a shortage of providers, and the constrained amount of time for those services in the health centers (Barik and Thorat, Reference Barik and Thorat2015; Organization W. H., 2006; Prinja et al., Reference Prinja, Kaur and Kumar2012).

Women scoring high in purpose in life may also particularly use preventive healthcare services as previously shown by other studies (Hajek et al., Reference Hajek, De Bock, Huebl, Kretzler and König2021; Hajek et al., Reference Hajek, De Bock, Kretzler and König2021). The link between purpose in life and an increased frequency of outpatient physician visits may be particularly explained by health-conscious behavior among women who score high on purpose in life.

The present review has some limitations. First off, only papers published in English were considered for the study; abstracts, dissertations, and unreviewed studies were excluded. So, caution should be taken in generalizing the results of this study. Since contradictory results were observed in some of the findings, it seems that primary studies and even meta-analysis are necessary to be done to show the causal relationships and the real effect of variables on health services utilization. To some extent, it can be said that the controversial results in our findings may be due to differences in the definitions of health services, study time, and sample size. As another limitation, this review did not investigate studies that were published before 2010. It is suggested that future systematic review studies explore the relationship between variables and health services utilization regardless of time limitations.

Conclusion

The results of the present review showed that in order to achieve the universal goals of health services coverage and health service utilization, it is necessary for countries to provide insurance coverage to the maximum number of people. Policymakers need to understand the correlated factors of women’s health services utilization in the healthcare system. An effective health policy should promote improvements in general health conditions for women while achieving absolute and relative reductions in inequalities. The identification of factors related to women’s health services utilization will be a good help for planning for the increase in health services accessibility. Policy and decision-makers have to consider improving the capability of women to access health services utilization. Also, policies should change in favor of the elderly, poor and low-income, low-educated, rural, ethnic minority, and chronically ill people and provide them with free preventive health services. Since there are other factors that can affect health services utilization among women but have not been considered in the reviewed studies, future primary studies should consider these variables, which include the nature of the job, patient awareness, attitudes toward medical institutions, and so on. The findings of the present study can extend the knowledge of factors related to health services utilization among women. Therefore, the development of health services models and the provision of services based on the results of the present review is recommended.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express many thanks for Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Health Management and Safety Promotion Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for giving us the opportunity to carry out this study

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, and the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ Contributions

Study concept and design: NSA, MA, and SEK. Search, analysis and interpretation of data: SEK, AE, and BZ. Drafting the manuscript: SEK, NSA, GK, and MA. Critical revision of the manuscript: MAMG and BZ. Field investigation supervision: SEK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This study was financially supported by the Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Competing interest

None.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.