Following Trump's surprising victory in the 2016 Presidential election, numerous studies drawing on post-election surveys sought to understand which factors played crucial roles in influencing Americans to vote for Trump. Along with political party identification and ideology (which are always the strongest predictors of partisan voting behavior), social scientists identified ethnocentrism and racism (Major, Blodorn, and Blascovich Reference Major, Blodorn and Blascovich2018; Schaffner, MacWilliams, and Nteta Reference Schaffner, Macwilliams and Nteta2018; Guth Reference Guth2019; Reny, Loren, Valenzuela Reference Reny, Loren and Valenzuela2019), fear of terrorism driven or amplified by Islamophobia (Whitehead, Perry, and Baker Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018; Guth Reference Guth2019; Tucker et al. Reference Tucker, Torres, Sinclair and Smith2019), hostile sexism (Schaffner et al. Reference Schaffner, Macwilliams and Nteta2018; Bracic, Israel-Trummel, and Shortle Reference Bracic, Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019), economic anxiety or dissatisfaction (Morgan and Lee Reference Morgan and Lee2018; Sides et al. Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018), and religious or Christian nationalism (Gorski Reference Gorski2017; Whitehead et al. Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020) as powerful predictors. Within the past year, an emerging body of research sought to predict who intended to vote for Trump in 2020, and analyses yielded similar results. Specifically, researchers showed that Christian nationalism along with xenophobia, Islamophobia, and other factors remained powerful indicators that Americans planned on casting their ballot for Trump in November 2020 (Baker, Perry, and Whitehead Reference Baker, Perry and Whitehead2020).

Though critical for understanding the powerful and persistent association between Christian nationalist ideology and Trump support in 2016 and again in 2020, descriptively, Christian nationalism is quite prevalent among Americans we would already expect to vote for Donald Trump: white evangelical Protestants, partisan Republicans, Americans who hold more xenophobic, militarist, and ethnocentric views (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2021; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). While models can account for correlates of Trump support to isolate the net influence of Christian nationalism, an arguably more robust test of Christian nationalism's influence would be an analysis of whether it had the power to influence Americans to vote for Trump in 2020 who previously did not vote for him. The reverse is also consequential, namely, whether Christian nationalism inoculated Americans who previously voted for Trump in 2016 from turning to other possible options in 2020. Drawing on a recent nationally representative survey that asks about Americans' vote choice in 2016 and their intended voting behavior in November 2020 (as of February 2020), in this study, we document the “converting” and “prophylactic” potential of Christian nationalism regarding Trump's presidency.

CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM AND VOTING FOR TRUMP IN 2016 AND 2020

Leading up to the 2016 Presidential election, pollsters and social scientists began to identify several common cultural threads uniting the swelling ranks of Americans throwing their enthusiasm behind Trump's candidacy. These included concerns over jobs, fear of Mexican immigrants and terrorism, grieving the perceived decline of masculinity, the importance of Supreme Court appointments (a proxy both for pro-life and “religious liberty” issues), and a general fear of the nation “losing its culture and identity” (representing the view of roughly four out of five white working-class evangelicals) (Pew Research Center 2016; Cox et al. Reference Cox, Lienesch and Jones2017). Following Trump's victory in 2016, polls and surveys confirmed much of the same. A burgeoning literature identified “Christian nationalism,” especially when held by white Americans, as uniting and amplifying these attitudinal trends, which mobilized support for Trump in the election. Drawing on 2017 data, for example, Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018) found that, behind only partisan identification and conservative ideology, Christian nationalism along with Islamophobia were the strongest predictors that Americans voted for Trump in 2016.

An expanding collection of studies document Christian nationalism's direct association with nearly all attitudinal correlates of Trump support. For instance, (white) Americans who more strongly hold to Christian nationalist views exhibit nativist and xenophobic attitudes (McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Nooruddin and Shortle2011; Sherkat and Lehman Reference Sherkat and Lehman2018; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2021; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), and particularly toward Muslims or refugees from Muslim-majority countries (Shortle and Gaddie Reference Shortle and Gaddie2015; Dahab and Omori Reference Dahab and Omori2019); they are less favorable toward gun control (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020); they are more in favor of strong military intervention as well as authoritarian policing tactics, potentially justified with tacit racism (Davis and Perry Reference Davis and Perry2020; Perry, Whitehead, and Davis Reference Perry, Whitehead and Davis2019); they tend to be against racial boundary-crossing in any context (Perry and Whitehead Reference Perry and Whitehead2015); and they are most favorable toward heterosexual, patriarchal romantic and family relationships (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2019; Reference Whitehead and Perry2020).

Unsurprisingly, given the attitudinal correlates of Christian nationalism, recent research examining the 2020 Presidential election documents the centrality of this ideology in shaping Americans' voting intentions. Using 2019 data with similar measures of Christian nationalism used by Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018), Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Perry and Whitehead2020) documented that Christian nationalism―again, in close connection with xenophobia and Islamophobia―remained a powerful predictor that Americans intended to vote for Trump in 2020 over other options.

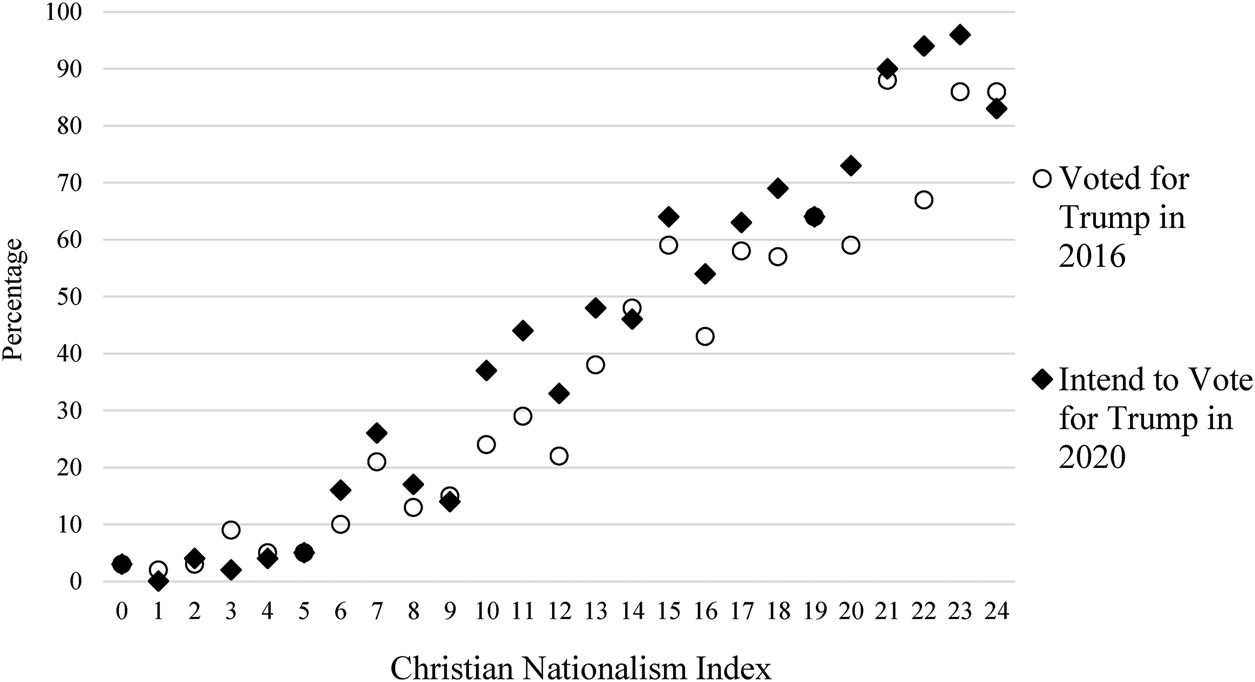

The unique data we use for this study confirm both Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018) and Baker et al.'s (Reference Baker, Perry and Whitehead2020) findings. Using a Christian nationalism index like that of Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018) (see Methods section below for how we operationalize this), Figure 1 plots both the percentage of Americans who voted for Trump in 2016 and the percentage who planned on voting for Trump in 2020 across index values (higher values indicate greater adherence to Christian nationalism). Clearly, our data also show that Christian nationalism's association with Trump support in both 2016 and 2020 is essentially linear, like that of the studies cited above.

Figure 1. Percentages of Americans who voted for Trump in 2016 and those who planned on voting for Trump in November 2020 across scores on Christian nationalism index.

But considering the 2020 Presidential election, how might Christian nationalism have influenced those who in 2016 opted not to vote for Trump? Correspondingly, among those who did vote for Trump in 2016, would Christian nationalism still be associated with planning on voting for him again in 2020? Our analyses provide an initial answer to these questions.

METHODS

Data

Data are taken from Wave 2 of the Public Discourse Ethics Survey (PDES) (Perry and Grubbs Reference Perry and Grubbs2020). The longitudinal survey was designed by the authors and Wave 2 was fielded in February 2020 by YouGov, an international research data and analytics company. YouGov recruits a panel of respondents through websites and banner ads. These respondents are not paid directly but are entered into lotteries for monetary prizes. In order to draw a nationally representative sample, YouGov employs a method called “matching.” Drawing a random sample from the American Community Survey, YouGov then matches a respondent in the opt-in panel who is the closest to the Census respondent based on key sociodemographic factors. Because of the specific recruitment and sampling design used by YouGov, the company does not publish traditional response rates. However, YouGov develops sampling weights in order to ensure that the survey sample is in line with nationally representative norms for age, gender, race, education, and census region. Results from the PDES compare favorably with results from the 2018 General Social Survey on demographic factors such as age, gender, race, marital status, region, educational attainment, and evangelical affiliation (see Supplemental Table S1). The resulting original survey sample included 2,519 Americans that were matched and weighted. Due to sample attrition between waves and a very modest amount of missing data, our final analytic sample consists of 1,665 Americans (1,086 who did not vote for Trump in 2016; 579 who voted for Trump in 2016) who provided information on all the measures we use in this study.

Measures

Intent to Change One's Voting Behavior For or Away From Trump

Our two outcomes for this study involve intent to change one's voting behavior between the 2016 and 2020 Presidential elections. The survey asked respondents who they voted for in 2016. Options included Hilary Clinton, Donald Trump, Gary Johnson, Jill Stein, Evan McMullin, Other, and did not vote for President. They were also asked who they planned on voting for in the 2020 Presidential election. Options included Donald Trump, the Democratic nominee, a third-party candidate, or I would not vote. As expected, most survey respondents planned on voting the same in 2020 as they did in 2016. For example, among those who indicated they did not vote for Trump in 2016, 87.8% indicated they would not vote for him in 2020. Even more consistent, among those who voted for Trump in 2016, 92.5% indicated they planned on voting for him again in 2020.

For our analyses, we focused on respondents who planned on changing their voting behavior. Among those who did not vote for Trump in 2016 (n = 1,086), 12.2% said they planned on voting for him in 2020. This outcome is coded 1 if former non-Trump voters intended to vote for Trump in 2020, 0 = all other options. Among those who did vote for Trump in 2016 (n = 579), 7.5% said they did not plan on voting for him in 2020. To explore the influence of Christian nationalism on Americans who intended to not vote for Trump in 2020 after voting for him in 2016, we created two different dependent variables. First, we coded respondents 1 if they planned on voting for the Democratic candidate, a third party candidate, or not at all. Second, we omitted the few who said they did not plan on voting at all to compare Christian nationalism's influence on voting for an actual alternate candidate besides Trump.Footnote 1 Because these outcomes are dichotomous, we used binary logistic regression as our model estimation strategy.

Christian Nationalism

Following studies by Whitehead and coworkers (e.g., Perry and Whitehead Reference Perry and Whitehead2015; Whitehead et al. Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Whitehead and Grubbs2021; Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2020), we adopted their six measures of Christian nationalism to create an identical index. This scale includes six level-of-agreement questions using the same statements: “The federal government should advocate Christian values,” “The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation,” “The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state (reverse coded),” “The federal government should allow religious symbols in public spaces,” “The federal government should allow prayer in public schools,” and “The success of the United States is part of God's plan.” Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. We combine these measures into an additive scale (set to zero) ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater adherence to Christian nationalism (Cronbach's α = 0.90).

Control Variables

The analysis includes a variety of controls that we theorized could be related to Americans intending to change their voting behavior for or against Trump. These include vote choice in 2016, relevant religious controls, ideological beliefs, and sociodemographic characteristics.

For the first analysis where we predicted intent to vote for Trump among Americans who previously did not vote for him in 2016, we include as controls Americans' vote choice in 2016. We created three categories: Did not vote, voted for Hilary Clinton, and voted for a third party candidate. The did not vote group are the reference and we create interaction terms with Christian nationalism × voted for Hilary Clinton and Christian nationalism × voted for a third party candidate.

Religious factors include religious commitment and whether respondents are white born-again or evangelical Protestants. Religious commitment is an index made from three measures that include church attendance (1 = never, 6 = more than once a week), prayer frequency (1 = never, 7 = several times a day), and religious importance (1 = not at all important, 4 = very important). Measures were transformed into Z-scores and summed to construct the index with a Cronbach's α of 0.84. Because evangelical or born-again Protestants were among the strongest supporters of Trump in the 2016 election and still overwhelmingly support him (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Perry and Whitehead2020), we created a dummy variable for whether Americans were white and considered themselves a “born-again or evangelical Christian” = 1, all other Americans = 0.Footnote 2

We account for several ideological controls that tap issues related to Trump support. First, we account for how someone considers themselves politically, ranging from 1 = very liberal to 5 = very conservative. The survey also asked respondents how much discrimination various groups received these days. Options ranged from 1 = “None at all” to 4 = “A lot.” We include respondents' responses to how much discrimination they thought “whites” and “Christians” received these days in order to tap whether respondents would change their vote for or against Trump because they perceived persecution against either group. We also include seven level-of-agreement statements intended to gauge respondents' attitudes toward terrorism, border control, climate change, transgender rights, gun control, racial inequality, and sexism. (The full wording of these statements is available from the authors upon request.) Response options to all ideological statements ranged from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree.

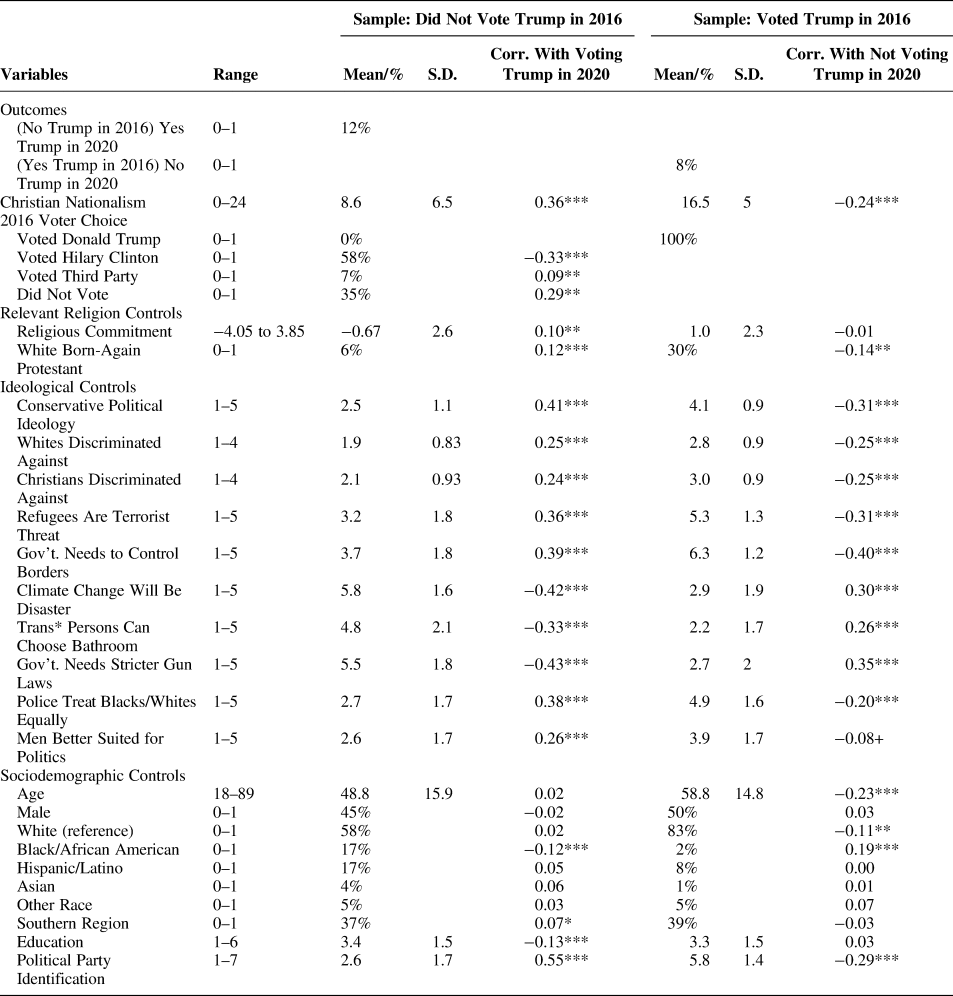

Last, the analysis includes a number of relevant sociodemographic factors: age (in years), gender (male = 1, female = 0), race (white = 0, Black = 1, Hispanic = 1, Asian = 1, Other race = 1), region (South = 1, other = 0), education (1 = no high school degree, 6 = post-graduate degree), and political party identification (1 = Strong Democrat, 7 = Strong Republican). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics as well as bivariate associations between the outcome variables and all predictors.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Source: 2020 Public Discourse and Ethics Survey, Wave 2.

+p < 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

RESULTS

Table 1 establishes clear bivariate associations between our variables of interest and intent to change one's voting behavior regarding Trump between 2016 and 2020. Notably, while almost all of the ideological and political variables are significantly associated with intent to change one's voting behavior, the association between Christian nationalism and intent to change one's voting behavior for Trump (r = 0.36, p < 0.001) or against Trump (r = −0.24, p < 0.001) is of comparable size. It is also far stronger than either religious commitment or being a white born-again Protestant.

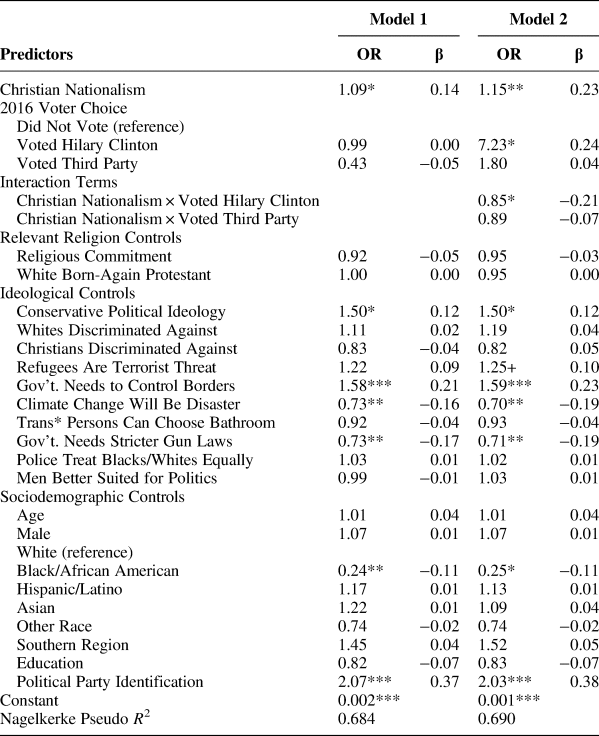

Turning to the multivariate models, Tables 2 and 3 present odds ratios and fully standardized logistic regression coefficients in order to establish the substantive magnitude of the effects. In Table 2, Model 1 demonstrates that Christian nationalism is significantly and positively associated with Americans who previously did not vote for Trump in 2016 planning on voting for him in 2020 (OR = 1.09; p < 0.05; β = 0.14). In terms of substantive significance, Christian nationalism is the fifth strongest predictor of intent to change one's voting behavior toward Trump, behind Republican party identification (β = 0.37), belief that the federal government must strengthen our Southern border (β = 0.21), opposition to stricter gun laws (β = −0.17), and disregard for the consequences of climate change (β = −0.16).

Table 2. Binary logistic regression models predicting intent to vote for Trump 2020 among Americans who did not vote for him in 2016

Source: 2020 Public Discourse and Ethics Survey, Wave 2 (N = 1,086).

+p < 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

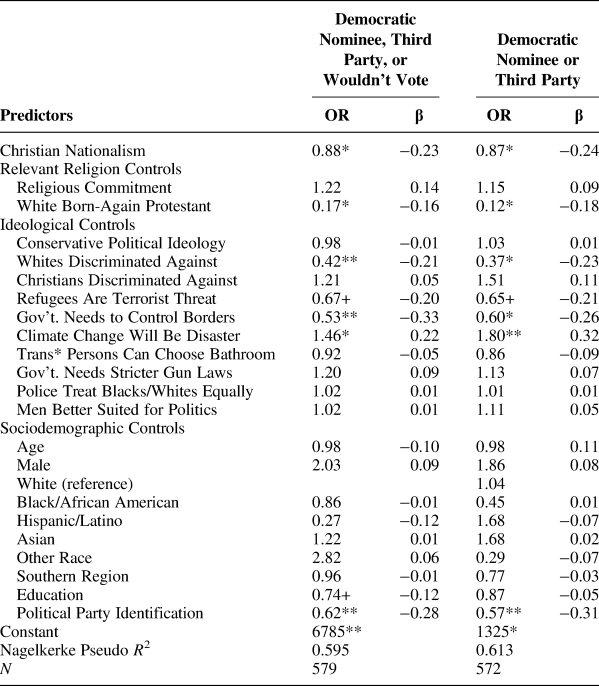

Table 3. Binary logistic regression models predicting intent to vote against Trump in 2020 among Americans who voted for him in 2016

Source: 2020 Public Discourse and Ethics Survey, Wave 2.

+p < 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests).

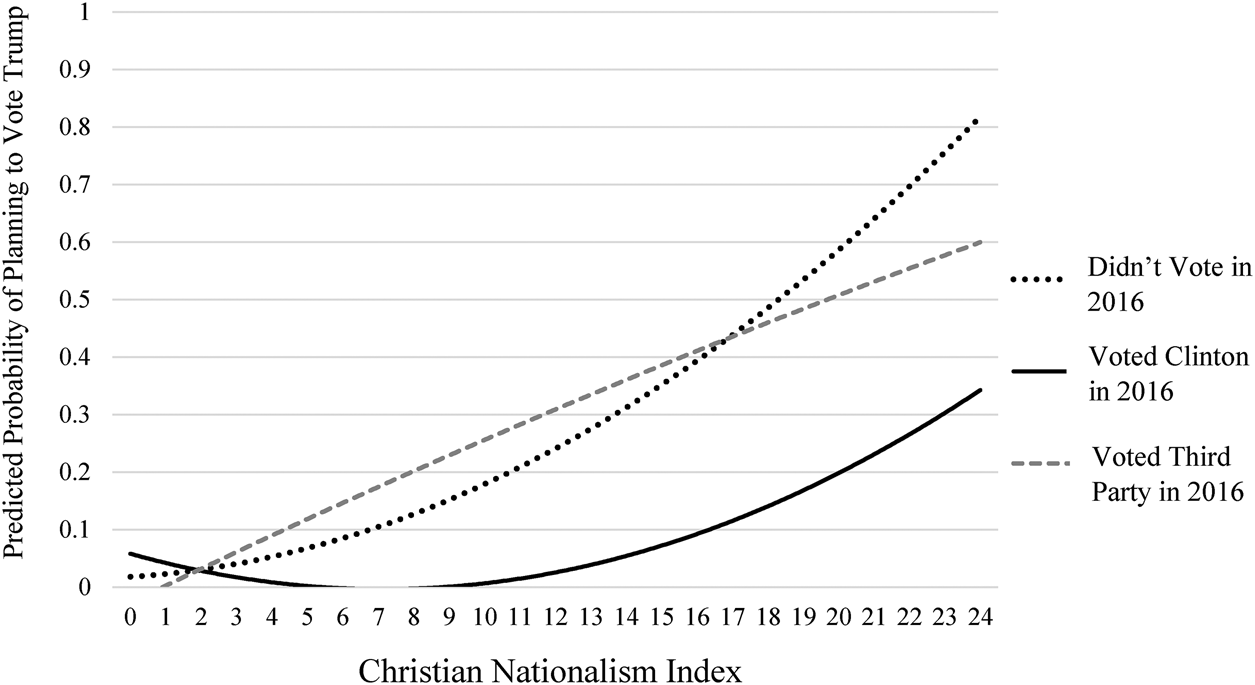

Model 2 includes interaction terms for Christian nationalism × voted for Hilary Clinton and Christian nationalism × voted for a third party candidate. Voting for Clinton in 2016 significantly moderated the association between Christian nationalism and intent to vote for Trump in 2020. Specifically, the interaction term (OR = 0.85; p < 0.05; β = −0.21) was negative indicating that for Americans who voted Clinton, the association between Christian nationalism and changing their vote to Trump was not as strong compared to those who did not vote at all in 2016. The interaction term for Christian nationalism and voting third party in 2016 was non-significant indicating that the slopes did not differ between third party voters and those who did not vote in 2016.

The predicted probabilities plotted out in Figure 2 illustrate these findings. As Christian nationalism increased, those who either did not vote in 2016 or voted third party in 2016 increased in their likelihood of intending to vote for Trump in 2020 at a steep rate. Compared to these two groups, however, Americans who voted for Clinton in 2016 only increased in their likelihood of intending to vote for Trump at the most extreme levels of Christian nationalist ideology. In sum, Christian nationalism increased the likelihood of intent to vote for Trump in 2020 among those who were less committed to strictly partisan Democratic choice in 2016.

Figure 2. Predicted probability that Americans who DID NOT vote for Trump in 2016 planned on voting for him in November 2020 by voting behavior in 2016 and Christian nationalism.

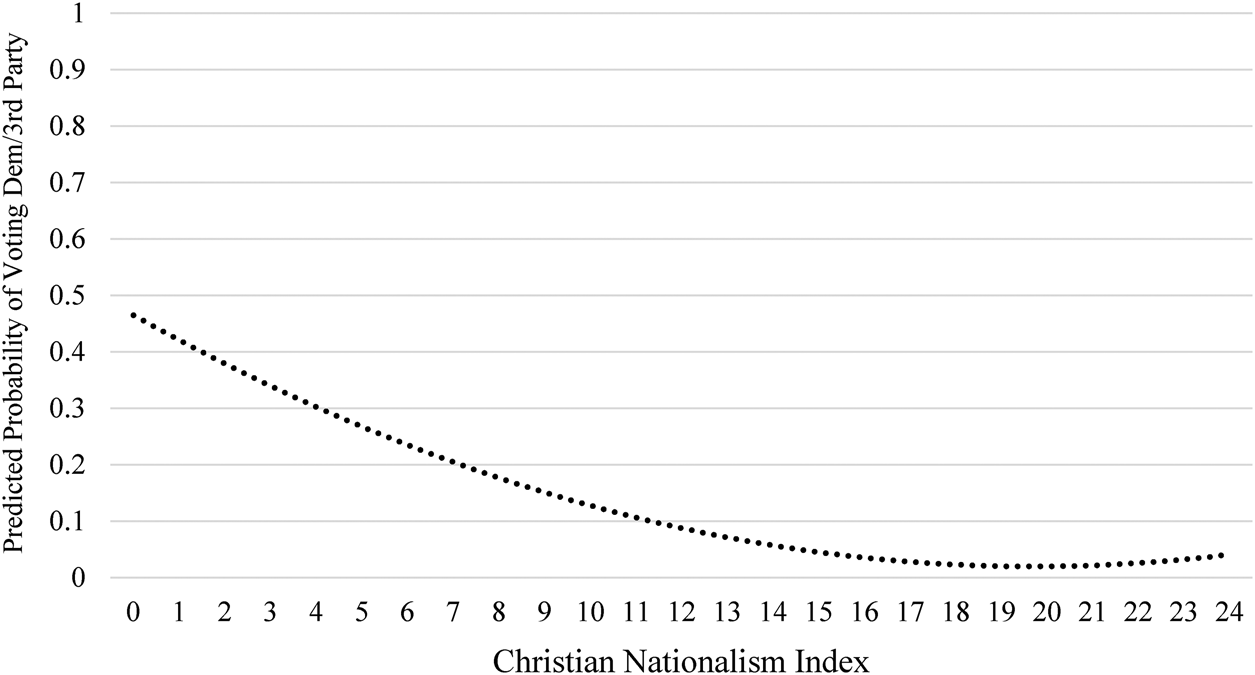

What about intending to change one's vote away from Trump in 2020? Table 3 presents two logistic regression models predicting choosing an alternative to Trump in 2020 among those Americans who voted for Trump in 2016. The first model includes all other options (voting Democrat, third party, or not voting at all) versus Trump. As expected, Christian nationalism was significantly and negatively associated with alternatives to voting Trump (OR = 0.88; p < 0.05; β = −0.23) and was the third strongest predictor in the model behind the belief that the government should do more to control our Southern border (β = −0.33) and Republican party identification (β = −0.28). In order to refine the analysis slightly, Model 2 omits the few respondents who indicated that they did not plan on voting in 2020. This allows us to focus on Americans who planned to make a choice between Trump and an actual alternate candidate. Again, Christian nationalism was a significant, negative predictor of planning to vote for anyone besides Trump (OR = 0.87; p < 0.05; β = −0.24), but it was the fourth strongest predictor behind disregard for climate change (β = 0.32), Republican party identification (β = −0.31), and belief that the government should control the Southern border (β = −0.26).

Figure 3 illustrates this relationship by plotting the predicted probability that those who voted for Trump in 2016 would intend to vote for another candidate in 2020 across values of Christian nationalism. While the likelihood of voting for a Democratic or third party candidate was essentially a coin flip for former Trump-voters who largely reject Christian nationalist ideology, this likelihood declined rapidly as adherence to Christian nationalism increased.

Figure 3. Predicted probability that Americans who voted for Trump in 2016 planned on voting for a Democratic or Third Party candidate in November 2020 across Christian nationalism.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Previous research establishes the strong association between Christian nationalism and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election as well as intent to vote for him in 2020 (Baker et al. Reference Baker, Perry and Whitehead2020; Whitehead et al. Reference Whitehead, Perry and Baker2018). In order to further explore the strength of Christian nationalism's influence on voter behavior and provide nuance to that association, our study shifts the focus to examine how this ideology potentially motivated or prevented changing one's voting behavior between 2016 and 2020. Among Americans who did not vote for Trump in 2016, Christian nationalism was a significant predictor that such Americans intended to vote for him in 2020, but mostly among those who either did not vote or voted third party in 2016. The influence of Christian nationalism was much less pronounced among Clinton voters. Conversely, focusing on Americans who voted for Trump in 2016, Christian nationalism was a significant, negative predictor that they would consider another candidate (either Democratic or third party) in 2020. Our findings thus suggest that Christian nationalism may have influenced the “conversion” of Americans into Trump-voters, and for those who earlier voted for Trump in 2016, it inoculated them from considering other candidates besides Trump.

Our findings extend our understanding of both Christian nationalism and the 2020 Presidential election in several important ways. First, Christian nationalism is a vital explanation of which Americans were most likely to become Trump-voters. However, it does not affect all voters equally. Americans who voted for Hilary Clinton in 2016 were likely solidly-partisan and would be reluctant to vote for Donald Trump in 2020 no matter their ideology regarding America's relationship to Christianity. Conversely, however, Americans who either did not vote in 2016 or voted third party were by comparison weakly tied to partisan commitments, and thus, Christian nationalist ideology (combined with Trump's appeals to Christian nationalist rhetoric) could have effectively drawn this population toward Trump as a candidate. That is, Christian nationalism had the potential to move Americans in the middle toward Trump. While those on the far right would already vote for Trump regardless, and those on the far left would vote against him, Trump's appeals to America's religious heritage, threats against religious freedom, stoking fears of ethno-religious outsiders (Muslims), and promises of Supreme Court justices may have attracted the Americans in the moderate middle, many of whom—as Whitehead and Perry (Reference Whitehead and Perry2020) have recently shown—are often quite amenable to Christian nationalist ideology.

Conversely, the fact that Christian nationalism was still a robust predictor that Americans who already voted for Trump in 2016 would vote for him again in 2020 over either a Democratic or third party candidate, even after taking into account relevant political and religious characteristics, suggests that Trump had been succeeding in the eyes of those who wished to realize Christian nationalist goals. Those goals may be understood by disaggregating the measures in our Christian nationalist index: Americans who believe the government should advocate Christian values and declare the United States a Christian nation, that religious iconography and rituals should have a place in the public square, that there need not be a strict separation of church and state, or that we should acknowledge America's special place in God's plan. Our findings suggest that Trump's appeals to Christian nationalism and his (reputed) track record at scoring political victories on the issues important to Christian nationalists solidified their support for Trump. The likelihood that they saw Trump as the best option among any collection of choices was a virtual certainty.

Before further discussing the implications of our findings, several data limitations should be acknowledged in order to chart a path for future research. First, the data are cross-sectional. While our analysis does take into consideration change in one's political behavior (e.g., from not voting for Trump in 2016 to voting for him in 2020, or vice versa), our working causal model (e.g., Christian nationalism influencing voting patterns) makes more sense than the alternative, and our models control for a large variety of potential confounds, our causal claims must be made with the caveat that we have not definitely determined temporal precedence. Future research would ideally make use of panel designs that inquire about these attitudes and behaviors over time—and especially after elections—in order to isolate how these factors vary together. Another data limitation would be the precise mechanisms at work in the relationships we identify. Though we propose that Trump's successful appeals to Christian nationalist dog whistles (“religious liberty,” “religious freedom,” generic “God” references) and his repeated claims of “promises made, promises kept” on such issues were effectually solidifying the connection between Christian nationalism and voting for him in 2020, qualitative data would be ideal to dig into the thought processes relevant to Christian nationalism that would lead Americans who did not vote for Trump in 2016 to plan on voting for him in 2020.

In addition to filling these gaps with future data, future studies on this topic should also attend to Christian nationalism's role in (1) continuing support for Trump despite his ultimate loss in November 2020, and (2) influencing support for whomever would be the next Republican presidential candidate to follow Trump. If Trump has intentionally drawn on Christian nationalist rhetoric in order to shore up support among a strategic voting block of Americans, despite his election loss and subsequent implication in the deadly Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021, it will be important to see whether this community's political utility for him will be spent. Correspondingly, to the extent that Trump no longer makes regular appeals to Christian nationalist rhetoric and issues, it will be interesting to see whether the link between Christian nationalism and ongoing support for him post-presidency remains as strong.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S175504832100002X.