1. Introduction

The defense policy of radical right populist parties (RRPPs) has attracted significant attention. In the context of the Russian war in Ukraine, RRPPs have advocated more ambiguous and pro-Russian position than established or mainstream parties, defined as parties that have held parliamentary seats for longer than RRPPs. Important RRPPs have long been close to Russian policy (Snegovaya, Reference Snegovaya2022; Heinisch and Hofmann, Reference Heinisch, Hofmann, Gilles and Zankina2023). Most hold distinct defense policy positions more generally. In line with their ideological orientation, they are cautious with respect to military engagements abroad and multilateral obligations within the European Union and NATO (Verbeek and Zaslove, Reference Verbeek and Zaslove2015; Balfour et al., Reference Balfour, Emmanouilidis, Grabbe, Lochocki, Mudde, Schmidt, Fieschi, Hill, Mendras, Niemi and Stratulat2016; Ishiyama et al., Reference Ishiyama, Pace and Stewart2018; Chryssogelos, Reference Chryssogelos2021; Henke and Maher, Reference Henke and Maher2021).

We examine whether the electoral success of RRPPs influences the defense policy positions of established parties. We suggest that the positions of RRPPs overlap sufficiently with military skeptical stances of left parties to raise concerns. Given the low electoral salience of defense policy, this proximity is electorally unproblematic. Yet, it is a problem for the reputation of left parties as coalition parties and international partners. Illustrating this logic, the head of the German parliament's defense committee, a leading Liberal party member, harshly criticized the head of the Social Democrat parliamentary group for sharing defense positions with the radical right AfD that deviate from the country's foreign policy commitments. The Social Democrats aggressively rejected any similarity between their and the radical right's stance.Footnote 1 Importantly, the comparison with the AfD triggered the strong reactions, highlighting not only the Social Democrats' effort to avoid any perception of similarity, but also a dynamic we might not have observed absent of a parliamentary presence of the radical right. We suspect that this example illustrates a more general mechanism. We thus argue that the electoral success of RRPPs might encourage left parties to adopt more assertive defense positions to safeguard their reputation, whereas mainstream right parties are likely to stand their ground. The overall result is increased mainstream consensus on defense policy.

While most literature argues that mainstream parties adopt an accommodation strategy toward the radical right for electoral reasons, we highlight an adversarial strategy and nonelectoral mechanisms. However, we do not so much dispute existing findings than stress that adaptation strategies and mechanisms vary across policy domains. Existing literature focuses on the electorally salient core issues of RRPPs, especially immigration, and stresses electoral mechanisms (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Merrill and Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman2019; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Krause and Giebler, Reference Krause and Giebler2020). These works suggest that, for fear of losing votes to RRPPs, mainstream parties adopt an accommodation strategy by moving closer to radical right stances (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Yet, in the defense domain, electoral incentives are likely to be secondary compared to reputation concerns. In this context, we expect the closest mainstream parties, left parties, to move away from RRPPs, thus adopting an adversarial strategy.

Empirically, we focus on parties' positions on defense policy. In Europe, defense mainly refers to support for European and international military collaboration such as NATO and peacekeeping missions (Deighton, Reference Deighton2002; Balfour et al., Reference Balfour, Emmanouilidis, Grabbe, Lochocki, Mudde, Schmidt, Fieschi, Hill, Mendras, Niemi and Stratulat2016; Ishiyama et al., Reference Ishiyama, Pace and Stewart2018; Chryssogelos, Reference Chryssogelos2021). We draw on a cross-national regression discontinuity design (RDD). Cross-national data are important for explaining RRPP effects so as to go beyond geographic and situational political opportunities. Hence, we created quasi-panel data combining 27 European democracies that include Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. European countries have experienced significant successes of RRPPs, albeit to varying degrees and at different times. Following recent work (e.g., Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021), we build an RDD around electoral thresholds for obtaining parliamentary seats. Our focus is on proportional systems, in which legal or effective thresholds can be found.

Our main contribution is to provide cross-national evidence for the adversarial strategy, often thought to have lost out to accommodation, and mechanisms other than electoral incentives in a highly consequential policy domain. In contrast, we find no evidence for the accommodation strategy in defense policy, neither on the left nor on the right. As discussed in the conclusion, while further, electorally less salient domains need to be studied, this finding suggests limits as to the policy scope of the impact of the radical right on party policy in Europe. It indicates reluctance of party leaders to accommodate radical right policy absent of (perceived) electoral pressure. And it raises broader questions as to whether the adversarial strategy could gradually become more relevant even in electorally salient domains.

Our study also contributes to understanding the party politics of the defense domain. We agree with recent work that parties play an important role in defense policy (e.g., Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018). In this respect, the literature raises concern as to the detrimental impact of radical right governments on EU-level defense policy (Orenstein and Kelemen, Reference Orenstein and Kelemen2017). Moreover, since work on other policy domains suggests that mainstream parties adopt accommodation strategies, RRPPs could have been expected to have a detrimental indirect effect by jeopardizing the assertiveness on defense of mainstream parties. Especially left parties, given difficult internal politics around defense issues, could have been considered at risk. Our results instead suggest that such concerns might be overstated and that the success of RRPPs so far reinforces rather than undermines the mainstream's relatively united defense policy stance.

2. Mainstream parties and RRPPs

The current debate focuses on how established parties adapt to the core issues of RRPPs. It conceptualizes RRPPs as challenger parties that benefit from opposition to cultural, political, and economic openness of the national community, the liberalization of societal values, and the perceived socio-economic marginalization of certain groups, with immigration becoming their most important issue (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Norris and Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; de Vries and Hobolt, Reference de Vries and Hobolt2020; Gidron and Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2020). RRPPs are crucial drivers of the salience of immigration, globalization, and European integration issues (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Green-Pedersen and Otje, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otje2019). In their core domains, they trigger policy shifts by the other parties (Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Merrill and Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman2019; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Krause and Giebler, Reference Krause and Giebler2020).

The literature explains the success of RRPPs with their ability to politicize “wedge issues” (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006; Hobolt and de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2015; de Vries and Hobolt, Reference de Vries and Hobolt2020). Wedge issues are ill-aligned with existing dimensions of competition and can divide the platform of other parties (van de Wardt et al., Reference van de Wardt, de Vries and Hobolt2014: 987). By politicizing these issues, RRPPs pressure mainstream parties to define a reaction and, potentially, shift their positions (Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Merrill and Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman2019; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). Specifically, RRPPs seek to target mainstream voters that doubt the party leadership's stance, expose divides within governing coalitions, and highlight conflict within mainstream parties (van de Wardt et al., Reference van de Wardt, de Vries and Hobolt2014).

Most studies stress an electoral mechanism. Abou-Chadi and Krause (Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020: 831) suggest that mainstream parties try to “keep the niche party from stealing their votes at the subsequent elections.” For Meijers (Reference Meijers2017: 415), they hope “to lure supporters of the challenger to their party by incorporating elements of the challenger's policy.” In Meguid's (Reference Meguid2005) classification, this is the accommodation strategy, in which parties challenge the issue ownership and positional exclusivity of the challenger to win back voters. The main alternative, for which limited evidence exists so far, would be an adversarial strategy, in which parties distance themselves from the challenger. Meguid (Reference Meguid2005) recommends adversity for “non-proximal” parties to aggravate the electoral competition between the challenger and the closest mainstream party.

Whereas most literature focuses on the electoral mechanism, we note that parties adopt positions, legislate, and govern in highly consequential yet less electorally salient domains as well. They might ignore RRPPs in these domains, Meguid's dismissive strategy, but they might also respond due to non-electoral mechanisms. Some studies mention such mechanisms, including constraints on policy change arising from policy-seeking (Merrill and Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman2019), the need to remain a coalition partner (van de Wardt et al., Reference van de Wardt, de Vries and Hobolt2014), or international commitments (Bardi et al., Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2014). For example, in the European Parliament, which is one step removed from electoral politics, parties have upheld a (imperfect) cordon sanitaire to radical right parties, demanded sanction against radical right governments, and the European Peoples Party split with the Hungarian Fidesz party (Meijers and van der Veer, Reference Meijers and van der Veer2019; Kantola and Miller, Reference Kantola and Miller2021; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2024), all despite radical right electoral gains. What the aforementioned mechanisms imply for party strategy more generally remains unclear, however.

Defense is a paradigmatic case of a highly consequential yet low salience domain. In data on the salience for 15 policy areas based on the comparative manifesto project (Gunderson, Reference Gunderson2024), “peace” ranked only as the 9th priority on average (SD: 2.9, median: 10) considering all parties and elections in the countries we study since 2000. Peace ranked among the top 3 priorities in only 26 of 1145 party-election observations. The numbers differ little for successful parties (e.g., with more than 5 percent of the vote). There are certainly moments in which defense gains high salience, but these focus on exceptional decisions on war, peace, and military missions, and even then the electoral relevance is subject to debate (Aldrich et al., Reference Aldrich, Gelpi, Feaver, Reifler and Sharp2006; Clements, Reference Clements2013).

Defense policy exemplifies domains in which constraints besides electoral politics are crucial. The point is not, as recent work highlights (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018), that “politics stops at the water's edge”. Yet, European countries are deeply embedded in decades-old multilateral structures, which rely heavily on the credibility of commitments, so that parties' credibility as coalition and international partners could suffer if they appear close to challengers with deviant policy stances. For example, exploring why government and opposition parties kept supporting involvement in Afghanistan, Kreps (Reference Kreps2010) highlights party leaders' awareness of the reputation costs and defense implications of deviating from the alliance consensus. This, alongside limited electoral salience, raises the question as to whether arguments based on the electoral mechanism apply in defense policy.

3. Reacting to the defense policy positions of RRPPs

A pre-condition for RRPP influence on the positions of mainstream parties is that they adopt distinct positions. The literature indicates strongly that this condition is met. Regarding mainstream responses, we stress coalition-reputation concerns and international commitments. Emphasizing these rather than electoral motivations leads us to expect that left parties will adopt an adversarial strategy, in line with demands from potential coalition partners and international commitments.

RRPPs hold distinct and controversial positions in defense policy. Being characterized by authoritarianism, nativism, and populism (Stanley, Reference Stanley2008; Mudde, Reference Mudde2013; Caramani, Reference Caramani2017), and situated at the authoritarian end of the GAL-TAN dimension, they value law and order and security services, including the military (Biard, Reference Biard2019; Henke and Maher, Reference Henke and Maher2021). They consider the role of the security services as domestic, however. Nativism – RRPPs' focus on “the people” – suggests a focus on domestic concerns. Border protection agencies, countering the perceived threat of immigration, and territorial defense assume greater importance than foreign engagements (Balfour et al., Reference Balfour, Emmanouilidis, Grabbe, Lochocki, Mudde, Schmidt, Fieschi, Hill, Mendras, Niemi and Stratulat2016; Özdamar and Ceydilek, Reference Özdamar and Ceydilek2020; Henke and Maher, Reference Henke and Maher2021). Moreover, populism, and its skepticism of institutional constraints, collides with the multilateral nature of European defense policy (Falkner and Plattner, Reference Falkner and Plattner2020; Chryssogelos, Reference Chryssogelos2021; Henke and Maher, Reference Henke and Maher2021).

The defense policy of many, but not all (Wondreys, Reference Wondreys2023), RRPPs is further characterized by their relationship with Russia and ambiguous stance toward transatlantic relations. Snegovaya (Reference Snegovaya2022: 410) highlights an “intellectual and ideological fascination among many European radical right populist parties with Putin's Russia.” Russia, in turn, has cultivated “trojan horses” in Europe's foreign policy among parties and governments on the radical right (Orenstein and Kelemen, Reference Orenstein and Kelemen2017). RRPPs sympathize with Russia and reduce support for the military if Russia is a potential target (Ishiyama et al., Reference Ishiyama, Pace and Stewart2018). They often oppose the dominant role of the US at the global level and in NATO (Chryssogelos, Reference Chryssogelos2021).

RRPPs' association with Russia has triggered strong criticism. The Italian Northern League leader Salvini saw his credibility questioned due to his stance toward Russia.Footnote 2 The former leader of the UK Independence Party, Nigel Farage, has oscillated between praise for the Russian president Putin and rejection of the conditions in Russia, and has been challenged strongly by established parties.Footnote 3 The German AfD has hesitated to blame Russia for the war in Ukraine and faced harsh criticism.Footnote 4 RRPPs' sympathies toward the Russian regime are evident in their reactions to current events,Footnote 5 contrasting sharply with established parties that have reinforced their defense stances, especially some historically cautious parties on the left.

How do established parties respond to RRPPs? Center-right parties are in a comfortable position. They have long-standing positions on defense (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018), are most supportive of the use of force in European comparison (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020), and endorse Europe's multilateral defense commitments. Indeed, they are not the “proximal competitor” (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005), but far away from RRPPs' positions and likely to oppose these parties' stances strongly. Moving toward RRPPs in defense would require center-right parties to forgo longstanding policy commitments without, given low electoral salience, expecting to gain votes. In fact, even if the defense domain was electorally salient, the best option of the center-right, according to Meguid, would be adversarial: to stand their ground so as to underline the difficult position of the left.

The situation of the left is more difficult. Left parties are more critical of the military, more cautious on defense, and question military engagements abroad (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018). A study of expert surveys and party manifestos from 2010 to 2014 indicates that center-left parties held similar views on peace and security missions as RRPPs, with far-left parties being moderately more skeptical (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020: 575). If party families are compared, socialist parties differ more from RRPPs, albeit with exceptions (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020: 577). Additionally, far-left parties and factions within center-left parties harbor sympathies toward Russia (e.g., Snegovaya, Reference Snegovaya2022). This is not to deny that, following long-term moderation, center-left parties now hold more moderate positions than before the 1990s. Yet, they frequently retain influential factions with cautious views, as the example of the German Social Democrats in the introduction illustrates. This renders them vulnerable to criticism when RRPPs enter parliament and become a relevant comparison.

We suggest that this policy proximity motivates left parties to move away from RRPPs by adopting more assertive positions. Defense policy might not be electorally decisive, but proximity to RRPPs calls into question parties' and leaders' credibility as coalition and international partners. This challenge comes to the fore if RRPPs succeed electorally and thus draw attention to similarities with other parties. As government parties have to work with defense commitments within NATO and the EU (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018: 542), the success of RRPPs could draw attention to questions as to whether left parties are committed to these policies and willing to act accordingly in key decisions. And it could raise questions about their own relationship with Russia, given RRPPs' alleged proximity to Russia (e.g., Snegovaya, Reference Snegovaya2022). Center-right parties as well as party elites from the European party family, within which party elites regularly meet to debate policy (Senninger et al., Reference Senninger, Bischof and Ezrow2022), can be expected to challenge left parties for proximity to the radical right. Faced with these challenges, left party leaders are likely to distance themselves and their parties from RRPPs' defense policy stances.

We have not distinguished party families on the left but suggest that the argument extends to radical left parties that seek government participation. Which parties are office-seeking is hard to identify and some radical left parties remain shut out of coalition politics, as in Germany (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Constantin Wurthmann and Thomeczek2023). However, many have moderated their demands (Fagerholm, Reference Fagerholm2017), have participated in governments (Bale and Dunphy, Reference Bale and Dunphy2011; McDonnell and Newell, Reference McDonnell and Newell2011), and have voters who endorse institutional participation and gradual reform (Krauss and Wagner, Reference Krauss and Wagner2023). Interviews with Northern European radical left leaders show readiness to join governments and to demonstrate “one's cooperativeness, one's responsibility, one's competence, one's continuing koalitionsfähigkeit” (Bale and Dunphy, Reference Bale and Dunphy2011: 280). In Portugal the radical left supported the government and reliably voted for government policy in exchange for policy gains (Giorgi and Cancela, Reference Giorgi and Cancela2021). Moreover, radical left parties likely find sharing policy stances with the radical right troubling in principle. We thus suspect that, in defense policy, many radical left parties will react similarly to RRPPs as center-left parties.

Our argument builds on the assumption of low electoral salience, but might also hold if the electoral salience of defense increased. Even then, left parties might still opt for the adversarial strategy. First, the available evidence increasingly challenges the electoral benefit of accommodation, at least for left parties (Abou-Chadi and Wagner, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020), which might gradually affect the choices of party strategists. Second, many left parties are intrinsically sympathetic toward certain multilateral defense commitments (e.g., policies with a UN Security Council mandate, within European Union structures, or focused on human security) (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018: 541). Third, center-left parties in government have proven willing to vote for military engagements, indicating willingness to uphold commitments and governing responsibilities even in difficult situations (Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020: 578–582).

In sum, we expect that the success of RRPPs creates pressure to change positions for left parties that face a threat to their credibility as coalition and international partners. That center-right parties, as the non-proximal actors, are likely to stand their ground and criticize defense policy proximity between left and radical right populist parties adds pressure. Adopting an adversarial strategy, left party leaders are thus likely to shift positions away from RRPPs and toward more assertive defense policies. We assume, in line with the evidence, that electoral salience is low in defense and electoral considerations secondary. Yet, even under salience, the characteristics of this domain would be conducive to an adversarial strategy. The overall result of the positioning that we envisage is greater mainstream consensus in defense policy.

4. Research strategy

We examine the argument based on the fuzzy RDD. The RDD is a quasi-experimental method that has been widely used in the social sciences since Thistlewaite and Campbell (Reference Thistlewaite and Campbell1960) first introduced (e.g., Lee and Lemieux, Reference Lee and Lemieux2010; Caughey and Sekhon, Reference Caughey and Sekhon2011). A key idea behind RDD is that a series of observations in a treatment group that exceed an assigned threshold would have substantively different effects from observations in a control group. In this paper, we consider the entrance into the national parliament as the threshold (Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015; Bischof and Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021). As Abou-Chadi and Krause (Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020) notes, participation in the national parliament means that parties receive attention, participate in debates, committees, and decisions. Parliamentary representation also signals existing elites that RRPPs are serious competitors.

We make use of a standard fuzzy RD design that introduces an IV in addition to the treatment status (Imbens and Kalyanaraman, Reference Imbens and Kalyanaraman2012; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021). Since we cannot exclude entirely that, for various reasons, parties enter the parliament even if they are below the threshold, the fuzzy design is more appropriate than the standard sharp RDD because if the estimation considers samples far from the cutoff point, it is more likely to rely on extrapolation. To avoid this, the nonparametric RDD looks at observations around the cutoff point; hence potential bias caused by outliers is minimized. Since the change of policy positions is presumably clearer around the cutoff point, we primarily calculated optimal bandwidths by the Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (CCT) method (Calonico et al., Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014). While the non-parametric fuzzy RD design offers better convergence and bias properties, we also perform parametric fuzzy RD estimation to ascertain that the results do not rely on a particular approach. The method is also a suitable strategy since we have a relatively large sample (N = 1097). Following Valentim et al. (Reference Valentim, Núñez and Dinas2021), we first predict a treatment status (D).

where Di is a treatment status of each country (i). Di = 1 if subject i received treatment and Di = 0 otherwise. Here, Di = 1(Xi ⩾ c) and Zi is a dummy variable. c is a cutoff point. In the first stage, δ should not be 0 and thus, a value over the threshold has non-zero change in the probability of receiving the treatment (Valentim et al., Reference Valentim, Núñez and Dinas2021).

In the second stage, Yi in the left-hand side of the equation stands for a potential shift in defense policy of established parties. Because our goal is to look at the shifts of party positions in response to RRPP success, we drop RRPPs from the analysis. On the right-hand side of the equation, x is a running variable that denotes a percentage of the vote given to RRPPs. In our model, x meets assumptions of continuity and as-if randomness. The range of x is expressed as c − h ⩽ x ⩽ c + h, where c is a cutoff and h is an optimal bandwidth. D denotes a binary treatment status. We assigned zero to D when the vote given to RRPPs is below the electoral threshold, x ⩽ c. Whereas when RRPP votes exceed the electoral threshold (x ⩾ c), we gave one. Here, the cutoff point equals zero because it represents a borderline whether an RRPP joins in the national assembly or not. The running variable is lagged for one election term since we are interested in whether the entrance of RRPPs in parliament in a given election affects established parties' subsequent national defense policy stances. α represents an intercept, and is an error term. The equation contains country fixed effect (i) to reduce sample variance across countries. As discussed by Valentim et al. (Reference Valentim, Núñez and Dinas2021), the assumption of exclusion that “the only way in which crossing the threshold can affect the outcome is via the change in the probability of treatment status” is applied to the fuzzy RD that employs IV approach.

Our parametric fuzzy RD models set the polynomial order as one and the non-parametric fuzzy RD models set the polynomial order as two, since high-order polynomials cause noise (Gelman and Imbens, Reference Gelman and Imbens2019). We scrutinize the robustness of the model with different polynomial orders and covariates to control for East and West Europe, participation in militarized conflict, and parties' participation in a cabinet.Footnote 6

The RD design relies on two critical assumptions: continuity and as-if-randomization (no manipulation) of the running variable. We performed sorting test to check the continuity assumption of the running variable. The T value is −1.125 and it is not statistically significant (p > 0.260). It shows that observations of the running variables do not have discontinuity around the cut-off point. The second assumption is “no-manipulation-with-precision” where the running variable should be randomized around the cutoff point. The as-if random assumption is violated if a running variable is arbitrarily manipulated (McCrary, Reference McCrary2008). In this regard, Abou-Chadi and Krause (Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020) stresses that, while exerting control over the electoral results of RRPPs is possible under electoral fraud and through manipulation of the legal electoral threshold, these techniques are unavailable to political actors in consolidated European democracies. Moreover, Valentim (Reference Valentim2021: 14) points out: “Electoral thresholds vary from country to country and RRPPs cannot self-select into countries with lower electoral thresholds, nor can they manipulate their vote share to be just below or just above the threshold.” Thus, importantly, while the fuzzy nature of the electoral threshold makes it difficult to maintain continuity around the cut-off, it does not automatically mean that it fails to meet the assumption of RD design. Crespo (Reference Crespo2020) notes that standard literature on the RD design overlooked “administrative sorting” where administrative procedures which individuals cannot control or manipulate affect the running variables near the cut-off and confuses as-if-random assumption. In fact, electoral threshold and results cannot be manipulated in advanced democracies unless elections are rigged. Thus, while a part of density test does not ensure continuity and randomization of the running variable, we think that the continuity assumption also holds. Yet, to ensure further that the cutoff of the running variable is not caused by factors other than the treatment variable, we also estimated models with additional control variables and dropped observations without legal thresholds, respectively.

5. Data

Our RD model consists of three critical elements: we employ established parties' policy shifts in defense policy as the outcome variable, votes given to RRPPs in general elections as a running variable, and the nationwide electoral threshold as a cutoff point.

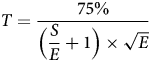

We use the legal, nationwide electoral threshold as the cutoff point, but some European countries do not have a legal threshold in electoral law. When a legal electoral threshold was missing, we manually calculated it. Following a similar strategy as Abou-Chadi and Krause (Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), we calculated the electoral threshold based on Taagepera (Reference Taagepera2002):

where T denotes the electoral threshold, S is the total number of obtained seats, and E is the number of electoral districts. Taagepera (Reference Taagepera2002: 383–384) asserted that “most often the combined effect of electoral rules and other factors brings about a zone of nationwide vote shares where parties sometimes succeed and sometimes fail in gaining representation. Within this zone, an average threshold of representation can be defined where parties have a 50–50 chance of winning their first seat.” We made use of Democratic Electoral Systems Around the World, 1946–2011 (DES Version 2.0) (Golder and Bormann, Reference Golder and Bormann2013) to obtain data of the number of electoral districts. Since DES only covers years up to 2011, we manually extended the data to 2013.

Electoral outcome data for the running variable, Vote given to RRPPs, was retrieved from MARPOR (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Theres, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020). We identify RRPPs based on PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou, Froio, Van Kessel, De Lange, Mudde and Taggart2023). PopuList codes parties from 31 European countries as, amongst others, populist and far-right.Footnote 7 The inclusion criteria are that parties have won more than a single seat or 2 percent votes in general elections since 1989 (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Pirro, Halikiopoulou, Froio, Van Kessel, De Lange, Mudde and Taggart2023).

Our core outcome variable is the party position on defense policy. To make sure that the result is isolated from this paradigmatic event, we focus on the period between 1990 and 2013. We benefited from MARPOR (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Theres, Merz, Regel, Weßels and Zehnter2020) to identify positions and salience. MARPOR has collected party manifestos from 424 parties and 172 elections between 1990 and 2013 to measure party policy stances. We do not include elections before 1990 because debates concerning defense issue have fundamentally changed since the fall of the Soviet Union. We also dropped observations after 2013 since Russia's occupation of Crimea in 2014 changed the European security perceptions, and might thus have affected party positions on defense policy. Drawing on this cross-national quasi-panel data, we created the defense position variable by subtracting Military Negative (Per105) from Military Positive (Per104).Footnote 8 This approach follows Ishiyama et al. (Reference Ishiyama, Pace and Stewart2018: 328), who elaborate that “smaller values indicate less importance in military preparedness and national defense, while higher values indicate a more militaristic party manifesto.” In the appendix, we present further analyses of salience in addition to positions. For these analyses, we measure salience as the overall space parties devote to defense in their manifestos by taking the sum of Per104 and Per105 (see also Gunderson, Reference Gunderson2024). The appendix also probes results for a separate measure, which captures a mix of salience and positions, based on the Chapel Hill expert survey (CHES), which is unfortunately only available for a few time points.

Furthermore, we conduct some analyses with additional outcome variables: the salience that parties attribute to Russia and the United States, important actors in Europe's security environment toward which RRPPs have a complicated stance. These variables are significant in light of current debates but whether they prove relevant in the period prior to the Russian occupation of Crimea is unclear. We again rely on MARPOR data. Our Russia Salience variable is the sum of “Russia/USSR/CIS: Positive (Per1011) (favorable mention to Russia and CIS countries)” and “Russia/USSR/CIS: Negative (Per1021) (negative mention to Russia and CIS countries).” The variable, US Salience sums “Western States: Negative (Per1022)” and “Western States: Positive (Per1012).” Per1012 and Per1022 measure favorable and unfavorable mentions of Western states in party manifestos. This measure can be expected to correlate with mentions of the US, but it is less precise than Russia Salience, which only refers to Russia and closely affiliated countries. A measurement that exclusively focuses on the US is not available in MARPOR.

6. Results

We start with an analysis of the effect of RRPPs on the defense position of all established parties and then distinguish left and right parties in subsequent analyses. Table 1 presents models with a running variable lagged for one election term. We transformed the outcome variable into a logarithm, as recommended in the literature (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011). We focus on fuzzy RDD, since the electoral threshold is not sharply defined in some countries (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021).

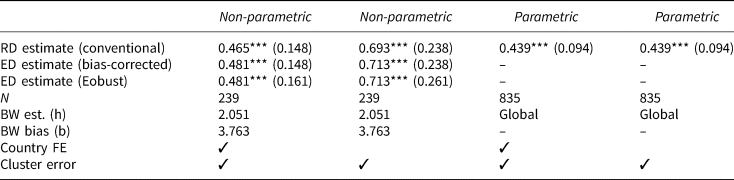

Table 1. Position of national defense policy: fuzzy regression discontinuity

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note: Observational period is between 1990 and 2013 before Russia's occupation of Crimea in 2014. We dropped observations after Russia's occupation of Crimea because the incident substantively changed European security framework. Position of national defense policy is calculated with Per 104–Per105. A running variable is lagged for an election term. Parametric RD is calculated with R. package “rddtools” and non-parametric RD is calculated with “rdrobust” package. Band widths are calculated by CCT method. Polynomial order is 2 in non-parametric models and 1 in parametric models.

Turning to the results, the local average treatment effect (LATE) on the main outcome variable, conventional estimates of position of national defense policy are 0.465 (p < 0.01) in the fuzzy non-parametric RD model with country fixed effects and 0.693 (p < 0.01) without country fixed effect. The conventional RD estimate of the parametric model is 0.439 (p < 0.01). As the outcome is log-transformed, for a unit increase in RRPP votes, established parties' position of national defense policy increases by approximately 55.1 to 104 percent. The results kept a similar direction and significance level after we added several covariates including an East Europe dummy variable, a participation of international military intervention, and RRPPs' participation to government. We also tested the results by focusing on the legal threshold only. Table A7 in the appendix shows the similar direction and significance level. However, while the parametric RDDs with and without country fixed effects consistently maintain statistical significance, the non-parametric model without country fixed effects loses significance. The analyses constitute evidence that established parties adopt a more assertive defense position in response to RRPP entry into the parliament and the effect within countries is robust.

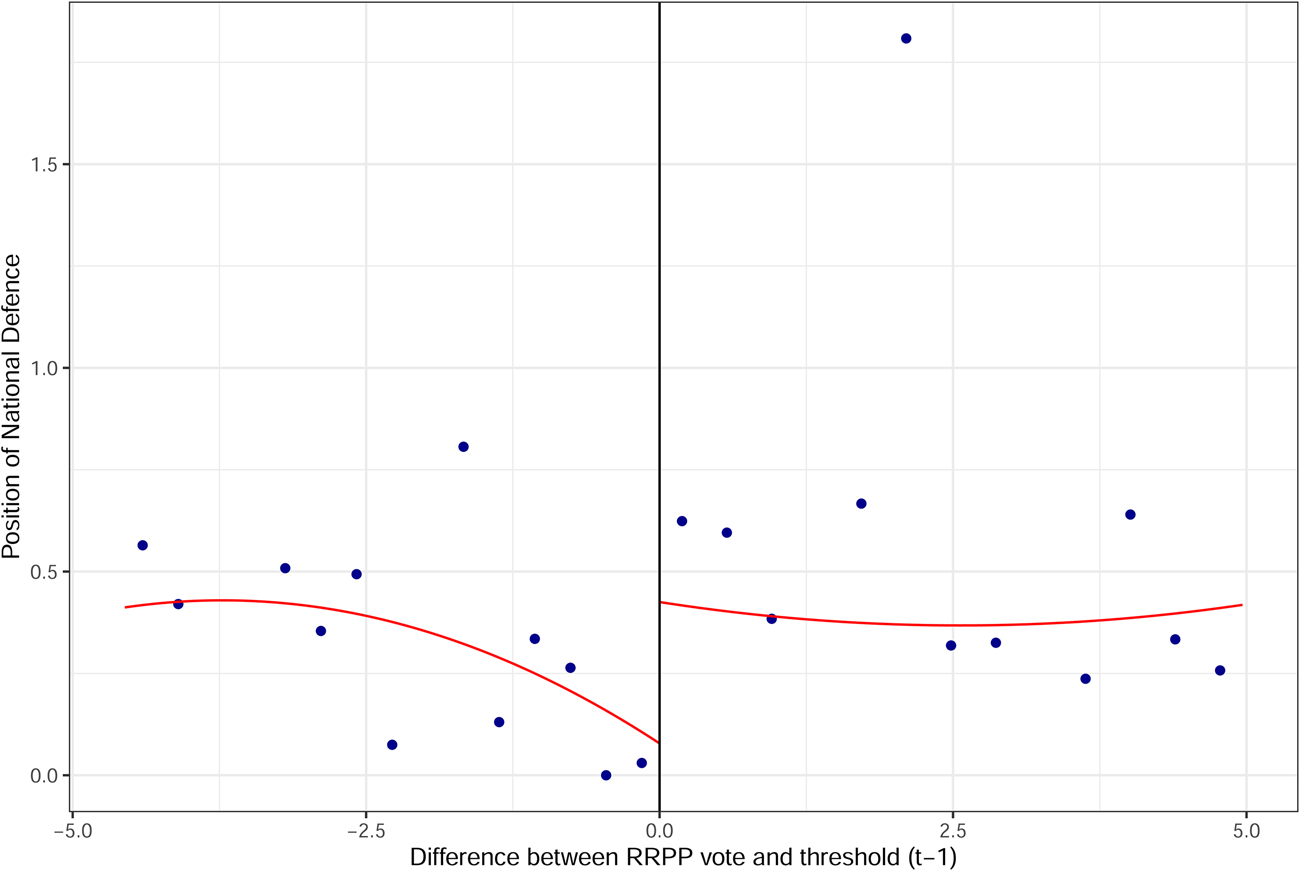

Figure 1 visualizes the non-parametric RD models (polynomial = 2) that estimate the local average effects on the position on national defense policy. The x-axis shows the difference between RRPP vote and the electoral threshold, the y-axis the position on defense policy. Dots are bin means. In substantive terms, the gap at the threshold of ca. 0.438 (in the share of positive minus the share of negative manifesto sentences) is a moderate but non-trivial effect given the overall range of this variable from ca. 4.423 to 2.743 and keeping in mind the wide range of issues covered in party manifestos.

Figure 1. Radical right populist parties and shift of defense position.

Note: Vote for RRPPs are lagged for one election term. Data of defense position are calculated as Per 104–Per105. Position of national defense is log.

The results presented above have parties' defense positions as a dependent variable. An alternative is to examine the change of a party's defense position from the previous election (for this approach, see, e.g., Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). Do we see changes if RRPPs passed the electoral threshold? We performed the analysis by making use of the change in defense positions as the dependent variable and checked model robustness with various bandwidths. Table A3 in the appendix is in line with the claim that parties change toward more assertive positions in response to the electoral success of RRPPs. A corresponding parametric fuzzy RD estimate is 0.319 (p < 0.05) and non-parametric conventional RD estimate is 0.954 (p < 0.01) when we apply CCT optimal bandwidth and lagged the running variable for an election term.

We ran additional fuzzy RDD to inspect the salience of Russia and the United States (see Table A2 in the appendix). However, we do not see any consistent change in our observational period. Figure A1 in the appendix plots the RD analyses on Russia salience and US salience. As noted, it is possible that between the end of the Cold War and Russia's occupation of Crimea, these variables lacked the relevance they seem to have in current debates.Footnote 9 We conducted further analyses of these two variables using CHES data (see the appendix).

We checked the robustness of the main findings with a series of alternative model specifications, such as RDD models with different polynomial order as suggested by Pei et al. (Reference Pei, Lee, Card and Weber2021) (Table A5 in the appendix) and placebo test (Table A6 in the appendix). Finally, we extended data and tested with different periods. Table A9 in the appendix covers a period between 1990 and 2021. Additionally, we added covariates such as an East-West European dummy variable, interstate war participation, and a government (cabinet) participation dummy variable (Table A4 in the appendix). All of the results aligned with our main finding that established parties shifted their defense policy by raising assertiveness. Yet, the estimates and significance of the results for defense policy salience are not fully consistent.

In sum, we find evidence that established parties adopt more assertive defense policy positions in response to RRPPs securing parliamentary seats. We also assessed whether established parties might raise the salience of defense policy and key security actors (see Table A8). In this respect, the findings are ambiguous. They do not suggest a significant effect on overall policy salience or the salience of key actors (anecdotal evidence from recent years notwithstanding). It thus seems conservative to conclude that established parties tend to respond to RRPPs by shifting their defense positions but not necessarily or consistently by altering the programmatic salience of defense policy or paying particular attention to Russia and the USA.

6.1 Which parties react to RRPP success?

We showed that established parties adopt more assertive defense policy positions in response to RRPP entry into national parliament. However, it remains untested which parties drive this effect. We argued that left parties have more reason to respond to RRPPs than right parties. To test this idea, we divide the party families in the Manifesto Project into left and right after having dropped missing values: “Socialist or other left parties (N = 133)” and “Social democratic parties (N = 190)” are coded as mainstream left parties. The mainstream right party family includes “Christian democratic parties (N = 167)” and “Conservative parties (N = 102).” Since “Liberal parties (N = 173)” can be both mainstream left and right, we do not include them. As a party family, liberal parties oscillate between center-right and center-left positions and do not fit the left category perfectly. In light of our argument, one could have expected the green parties to respond as well but we cannot test them separately because of the small number of observations. Note that our analysis includes only few observations on disaggregated party families, rendering more disaggregated tests difficult in practice. Finally, since the goal is to see the response to the radical right, we exclude RRPPs themselves.

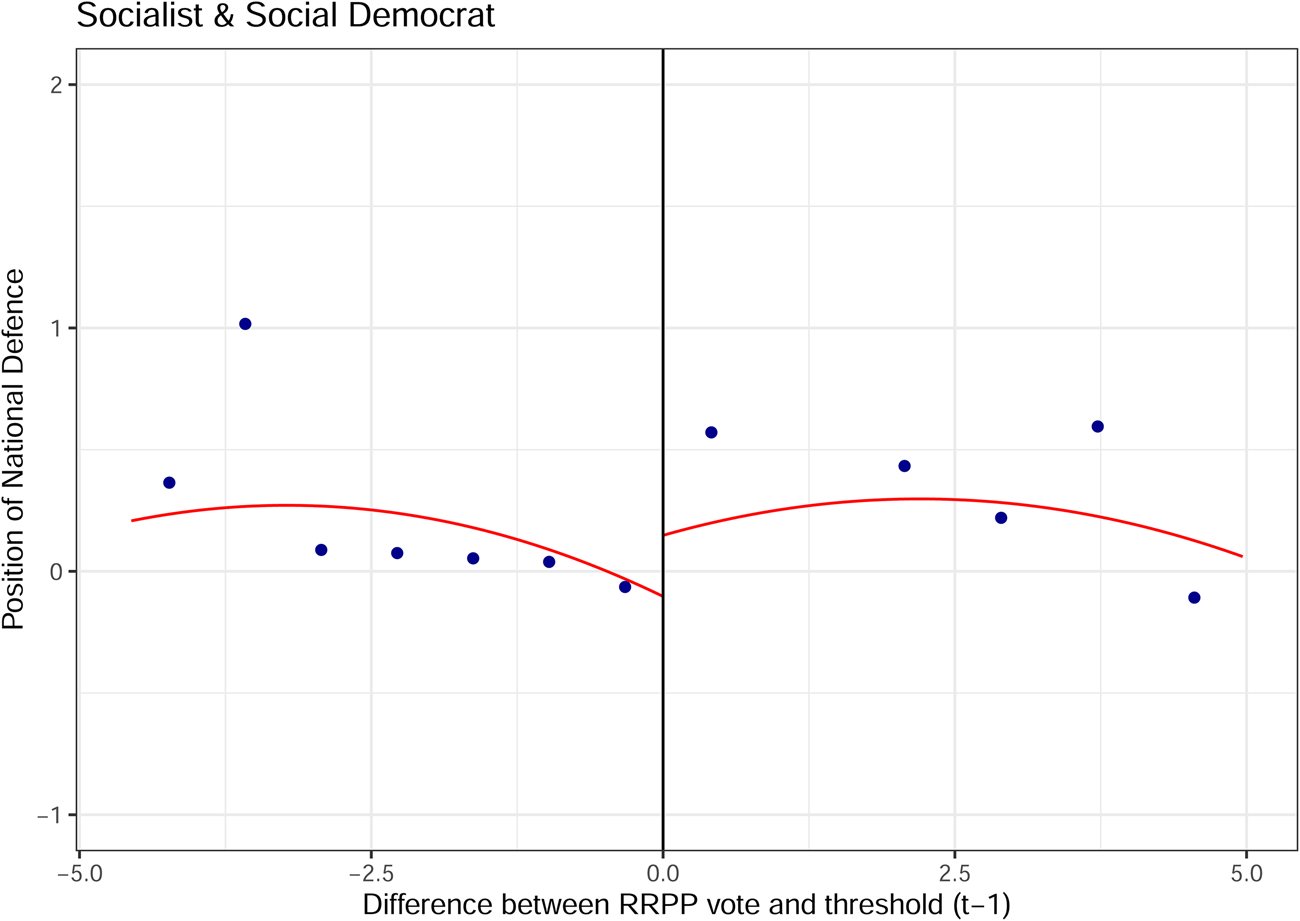

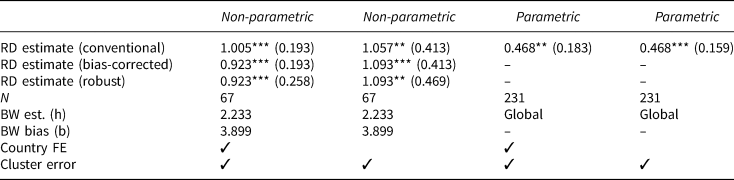

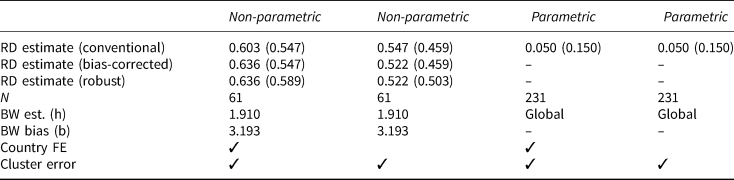

We ran further fuzzy RD models. Figure 2 visualizes the results for mainstream left-wing (Socialist and Social Democrat) parties. Tables 2 and 3 show that estimates of left-wing but not right-wing parties are statistically significant. In the parametric model, summarized in Table 2, the effects are about 0.5 (p < 0.01). While in non-parametric models, the effect ranges from 0.923 to 1.093 (p<0.01). Compared to the estimates for national defense position presented in Table 1, the magnitude of the effects is relatively large. Tables 3 presents the null effects of mainstream right parties.

Figure 2. Defense position of mainstream left parties.

Table 2. Mainstream left parties' shift in defense policy position

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note: Left-block parties include Socialist and Social Democratic Parties. Since Liberal parties are often classified as right-block party category, we dropped these parties from our observations. Green parties are also excluded since they are niche parties. Optimal bandwidth is calculated by CCT method.

Table 3. Mainstream right parties' shifts in defense policy position

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Note: Right-block parties include Christian Democrat and Conservatives. Since Liberal parties are often classified as right-block party category, we dropped these parties from our observations.

In sum, the results suggest that parties on the mainstream left adopt an adversarial strategy by changing their defense positions in response to the electoral success of RRPPs. In contrast, while mainstream right parties have adopted accommodation strategies in core policies of the radical right agenda, there is no evidence that they change their defense positions. This finding is consistent with the dismissive as well as adversarial strategy. Considering that mainstream right parties already have assertive defense stances by European standards and might be prevented from reinforcing assertiveness further by a ceiling effect, standing their ground could be an adversarial attempt to increase the pressure that left parties face from coalition and international partners over proximity to RRPPs' defense positions.

7. Conclusion

This study examined how established parties react to RRPPs in defense policy. Our main contribution is to highlight the relevance of the adversarial strategy suggested by Meguid (Reference Meguid2005). The literature frequently stresses that parties accommodate the positions of RRPPs under perceived electoral pressure. However, most studies focus on the electorally salient core domains of RRPPs (see, e.g., Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005; Zhirkov, Reference Zhirkov2014; Norocel, Reference Norocel2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Merrill and Grofman, Reference Merrill and Grofman2019; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Krause and Giebler, Reference Krause and Giebler2020; Rovny and Polk, Reference Rovny and Polk2020). We highlight that, in a highly consequential but electorally less salient domain, another response prevails. Left parties, the proximal parties, follow an adversarial strategy and right parties maintain their already assertive positions. We find no signs of the accommodation strategy so far seen as the dominant mainstream response to successes of the radical right.

Our argument draws attention to the possibility that parties consider their reputation with coalition and international partners when responding to the radical right. This indicates that, at least absent of perceived electoral pressures, party leaders have reason to avoid proximity to RRPPs, reducing the range of policies that could be affected detrimentally by the electoral success of the radical right. Whether this result holds in policy domains other than defense remains to be tested. There are many consequential policy domains in which electoral salience is low. Yet, many of these domains lack the decade-old international commitments that characterize defense policy.

It is currently less likely that the results extend to the electorally most salient domains often studied in the literature. In these domains, the electoral considerations that have motivated the adoption of accommodation strategies are likely to outweigh other factors (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). However, this picture could change. Growing evidence calls into question the electoral calculations of mainstream party strategists as to the electoral success of accommodation (for this debate, see, e.g., Abou-Chadi and Wagner, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Spoon and Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2020). If this evidence takes hold among party actors, the relevance of other influences on party strategy, including the mechanisms suggested here, might grow.

Finally, our results are crucial for the defense domain in which RRPPs have been seen as a detrimental and divisive influence at the EU level (Orenstein and Kelemen, Reference Orenstein and Kelemen2017). However, their domestic impact has remained unclear as they have, so far, rarely been in government. Moreover, most literature focuses on variation in defense positions across parties rather than on the impact of the radical right on mainstream parties (e.g., Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Herranz-Surrallés, Kaarbo and Ostermann2018; Haesebrouck and Mello, Reference Haesebrouck and Mello2020). Our results suggest that RRPPs fail to sow divisions among mainstream parties. The success of the radical right rather seems to foster mainstream unity.

We have focused on the effect of RRPPs on mainstream positions, but further research on the underlying mechanisms and consequences would be desirable. One might ask how left party leaders debate RRPP positions in defense policy within their parties and in the parliamentary arena. Another line of inquiry would be to examine more comprehensively how often left parties face the kind of criticism that the example from our introduction illustrates, and whether the adoption of more assertive defense positions in turn averts criticism and enhances reputation with other parties and international partners.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2024.40. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AOOX7Z.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the PSRM editors and three anonymous reviewers for insightful comments. We also appreciate the PSRM replication assistance team for helping us to finalize the replication material. Finally, we thank Yuliy Sannikov, participants of the Populism Seminar, and APSA 2021.