Every politician knows: ask for more than you want (or need). President Reagan famously claimed that any negotiation where he could get 70% of what he asked for was a win.Footnote 1 Senator Bernie Sanders vociferously campaigned for $6 trillion to tackle climate change, later conceding that “there will have to be some give and take.”Footnote 2 Similarly, President Biden campaigned to increase funding for the Community Oriented Policing Program by $300 million dollars. When he was elected president, he followed through on that promise by seeking a commensurate increase, but in the end the program received an increase of $125 million, less than 50% of what was originally sought. Similarly, voters discount politician platforms that they expect are not fulfillable. President Donald Trump campaigned on building a wall on the Mexican-American border to deter immigrants before the 2016 US presidential election. According to a poll by The Washington Post and ABC News, 52% of Republican voters believed he would not be able to deliver on this promise.Footnote 3

The above examples highlight a broad regularity: politicians’ campaign platforms are pledges that pull policy imperfectly in the direction of their proposed platform and away from a status quo. The degree to which policy pledges are accomplished depends on a politician’s skill at passing a legislative agenda, hiring advisers, staffing bureaucratic posts, delegating to experts (Patty and Turner, Reference Patty and Turner2021), or the extent of institutional support the politician enjoys, affecting her ability to mobilize support from other members of government (Turner, Reference Turner2017).Footnote 4 All these different components encapsulate a politician’s capability, which is an important consideration in political selection and accountability (Fearon, Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999; Manin et al., Reference Manin, Przeworski, Stokes, Przeworski, Stokes and Manin1999; Besley, Reference Besley2006; Ashworth, Reference Ashworth2012; Schnakenberg, Reference Schnakenberg2021). Scholars have often thought of political selection in theories of ideological competition through valence, a comprehensive term that encapsulates electoral considerations which are orthogonal to ideology. The theoretical and empirical literature on the relationship between valence and ideological platforms, however, has found mixed results, sometimes finding evidence that a valence advantage causes (relative) ideological moderation (Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001; Stone and Simas, Reference Stone and Simas2010), while also documenting that valence advantages cause ideological extremism (Burden, Reference Burden2004; Peress, Reference Peress2010). Are these seemingly contradictory empirical findings the result of measurement issues or other empirical concerns? Or is there a theoretical mechanism that gives rise to both kinds of findings simultaneously?

In this article, we develop a theory of electoral competition where voters evaluate politicians in terms of their ideological platforms as well as their capability to implement policy ambitions. We present a model where two politicians, one preferring left-leaning ideological policies, and one preferring right-leaning ideological policies, propose platforms that determine the policy they will ultimately implement if elected. Platforms in our model serve as pledges: a goal that politicians attempt to fulfill—to the best of their abilities—relative to a status quo. The degree to which a politician fulfills her platform, or pledge, depends on the capability of the politician, what Grofman Reference Grofman(1985) calls “the neglected role of the status quo.” We embed this critical feature in a model of electoral competition with probabilistic voting. Imperfect capability with regards to policy implementation naturally introduces a distinction between campaign platforms—goals that politicians profess to work toward—and the policies they ultimately implement. Voters, therefore, “discount” announced platforms, with platforms announced by more capable politicians being taken more seriously than those announced by relatively incapable politicians. Our theory, therefore, advances political capability as a factor that determines the link between platforms and policies, i.e., the platform-policy linkage. As a result, our model and results directly determine the conditions under which policies and platforms cohere in a reliable and meaningful way.

Our analysis focuses on a (relatively) moderate representative voter, whose ideological position falls between the ideal points of the leftist and rightist politicians. The voter prefers ideological policies that are closer to her ideal point, and all-else-equal also has a preference for a politician that is more capable at implementing common-value policies, such as those dealing with national crises. Therefore, the voter has a direct preference for capability, because this improves the implementation of nonpartisan policies. The voter may also indirectly fear a competent politician with an unpalatable ideological platform. The voter in our model is thus swayed by three key substantive forces. First, the ideological policy gap measures the extent to which politicians depart (spatially) from the voter’s most preferred ideological policy. Second, the capability gap represents the difference between politicians’ ability to “get things done,” and third, the salience of capability determines how important politician capability is directly to voters. Our theory elucidates the trade-off between political selection and ideological concerns and the novel empirical implications that follow when capability influences both.

First, a politician’s inability to implement her full platform means that the policies that ultimately get implemented are “anchored” by a status quo. We show that when status quo policies are extreme (in either direction), this anchoring causes the logic normally associated with left-right ideological competition to break down. An extreme status quo becomes the dominant concern in electoral competition and compels politicians to primarily compete with the status quo rather than each other, leading to both politicians’ platforms being on the same side of the voter. Our results thus provide a novel rationale for the link between extreme historical political legacies and populism, conceptualized as an extreme slant among both politicians relative to the voter (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Egorov and Sonin2013). We thus provide a theoretical account of the “embarrassed right” phenomenon in post-transition Brazil (Power and Rodrigues-Silveira, Reference Power, Rodrigues-Silveira and Ames2018), where even right-wing politicians campaigned on leftist labels, potentially owing to the extreme legacy left behind by Brazil’s erstwhile authoritarian regime.

We also consider whether relatively incapable politicians are more likely to profess an extreme platform. When electoral platforms follow the traditional left-right divide—with the leftist politician’s platform to the left and the rightist politician’s platform to the right of the voter—a capability advantage is translated into policy gains both directly because a politician is more effective at implementing her platform, and indirectly, because she is more desirable to the voter. But greater capability implies that the politician’s platforms are also taken more seriously, making the relationship between capability and platform extremism complex. We find that capability and platform extremism are negatively related in societies that value ideological performance over performance on common-value issues, because the incapable politician is not expected to fully implement her platform. Our results thus stress the importance of disentangling various politically relevant attributes of politicians, such as capability, rather than pigeonholing such attributes into valence. Our model also shows that extreme platforms are not necessarily cause for concern: when the salience of capability is low, it is the incapable politician who professes a more extreme platform, which she will ultimately be unable to fulfill.

The second part of our contribution develops a number of important empirical implications regarding platform competition, with particular emphasis on when changes to features of the environment affect platforms and policies the same way and when they do not. By distinguishing between platforms politicians compete on, from the policies they ultimately implement, our analysis allows us to determine when platforms and policies are coherent, meaning they respond to exogenous changes the same way. These results are useful because they suggest when platforms provide a good proxy for policies in empirical measurement. We first focus on the voter and consider the relationship between the salience of capability and politician platforms/policies. As the salience of capability increases, the voter likes the relatively capable politician more and tolerates a more ideologically extreme policy from that politician. How this affects the policy of the incapable politician depends on the relationship between the size of the capability gap and the magnitude of electoral uncertainty. When the capability gap is large (relative to uncertainty about the voter’s decision), then increasing the salience of capability causes the disadvantaged politician to moderate, whereas when the capability gap is small, increasing the salience of capability leads the competence-disadvantaged politician to a more ideologically extreme policy. We also show that changes in the salience of capability lead to qualitatively identical effects between policies and platforms, i.e., the sign of effects on platforms and policies is the same, which means that platforms are a good measure of policy implications when considering shocks to voter preferences.

Our last set of results address how changes in the platform-policy linkage, specifically the capability profile of politicians, impact policies and platforms differently. For the incapable politician, increasing her opponent’s capability leads her to moderate her ideological platform, compensating for becoming less attractive to the voter on nonpartisan issues. But for the capable politician, increased effectiveness is a double-edged sword. Although increased capability makes her more attractive to the voter, it also makes her more effective at implementing her ideological platform. This latter channel implies that increased capability is tantamount to making the capability-advantaged politician more ideologically extreme (relative to her opponent). When taken together, these competing forces imply that increasing the capability-advantaged politician’s capability has an ambiguous effect on her ideological platform, whereas its influence on her policy is straightforward, and the crucial factor driving this difference is the status quo.Footnote 5 When taken together, our results elucidate that changes to the voter’s calculus would have qualitatively the same effect on electoral platforms as on latent policies, but this coherence breaks down when a shock affects the technology connecting platforms and policies. Our results show when empirical specifications can interchange between using implemented policies or professed platforms.

1. Related literature

We contribute to the literature conceptualizing ideological competition spatially, which is comprehensively reviewed in Dewan and Shepsle Reference Dewan and Shepsle(2011) and Duggan and Martinelli Reference Duggan and Martinelli(2017). In this literature, a politician’s capability is typically interpreted as a component of her “valence,” along with other attributes like charm or charisma, that are orthogonal to the ideological dimension of political competition (Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001; Aragones and Palfrey, Reference Aragones and Palfrey2002; Reference Aragones and Palfrey2004; Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Buisseret and Hidir2020; Desai, Reference DesaiForthcoming). Within the large literature on electoral competition with valence gaps, as opposed to studying purely office-motivated politicians (Ansolabehere and Snyder Jr, Reference Ansolabehere and Snyder2000) or politicians with mixed motivation (Groseclose, Reference Groseclose2001), we study purely policy-motivated politicians. Furthermore, the source of electoral uncertainty in our model comes from a residual valence shock rather than the ideal point of the voter, allowing us to solve the model for any capability gap as opposed to Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001 who only looks at the limiting case when the valence gap shrinks to essentially zero. Another strand of this literature looks at the joint determination of ideological platforms and valence, thereby evaluating the strategic dependence between ideological platforms and valence (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2006; Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita, Reference Ashworth and Bueno de Mesquita2009; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2024). Depending on the objectives of politicians, these authors either find that office-motivated politicians diverge to soften competition on valence or policy-motivated politicians increase competition on valence to be able to diverge further ideologically.

Most of this highly influential literature abstracts away from questions about the platform-policy linkage and typically pigeonholes qualities such as capability or effectiveness into valence. Kartik et al. Reference Kartik, Van Weelden and Wolton(2017) are an exception, who assume that platforms constrain politicians to choose a policy from a particular set, which is otherwise unrelated to other politician characteristics. In this paper, we suggest that another aspect drives a disconnect between platform and policy—politician capability—and investigate its implications. Our model essentially does away with the assumption that the voter’s utility is additively separable in capability and policy, similar to the approach taken by Groseclose (Reference Groseclose2001, Appendix B). Our analysis, by contrast, focuses on the relationship between platforms and policy outcomes, which Groseclose Reference Groseclose2001 does not address.

Although platform discounting has not been addressed much in recent formal work, Downs (Reference Downs1957, p. 39) notes that “[The voter] knows that no party will be able to do everything it says it will do. Hence he cannot merely compare platforms; instead he must estimate in his own mind what the parties would actually do if they were in power.” There is strong empirical evidence that voters discount platforms and vote according to their expectations of what politicians can feasibly implement rather than what they propose (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bishin and Dow2004; Tomz and Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2008). Similarly, there is also strong empirical evidence that politicians propose pledges that may not be completely fulfilled due to factors such as power sharing, economic conditions, and even issue capability (Thomson, Reference Thomson2001; Sagarzazu and Klüver, Reference Sagarzazu and Klüver2017; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury and Pétry2017). Similarly, one can interpret the feasibility of what a politician can implement as a function of the legislative effectiveness that her party enjoys in the legislature, a feature incorporated in Wiseman Reference Wiseman(2006). Subsequent empirical literature on effectiveness is mixed, mattering more depending on the informational context. Voters demonstrate a preference for a more effective representative only when informed about their representative effectiveness in an experimental setting (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Hughes, Volden and Wiseman2023), and effective incumbents seem to enjoy an advantage over a relatively unknown primary challenger (Treul et al., Reference Treul, Thomsen, Volden and Wiseman2022). We combine the two insights of the existing literature—that voters discount platforms and that politicians may differ in their ability to implement platforms—into a unified model of electoral competition . In this vein, we take advantage of what Merrill III and Grofman Reference Merrill and Grofman(1998) call “shadow positions”—voter choice is based on proximity to the “shadow” of politician platforms, which depends on both politician capability and the status quo position.

Our platform-policy linkage builds on existing models of policy development, where policy developers choose both the policy and the quality of their proposal (Hirsch and Shotts, Reference Hirsch and Shotts2015; Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2023). However, when considering discounted platforms, it becomes natural to think of politician capability as their capacity to move policy from an existing status quo. We base this aspect of our model on Grofman Reference Grofman(1985) who models policymaking as a function of the distance between the status quo and the proposed platform. Subsequent work models politician effectiveness as her ability to move (spatial) ideological policy from a status quo and questions the conflation of candidate quality with valence (Miller, Reference Miller2011; Lee, Reference Lee2024). These authors show that voters have a more nuanced preference for capability relative to valence. Specifically, when capability serves to move ideological policies away from a status quo, voters may dislike more capable politicians. However, conceptualizing capability exclusively as ideological effectiveness is similarly incomplete. In most accounts of political accountability, a politician’s managerial capability is an important consideration for political selection (Ashworth, Reference Ashworth2012), and empirical evidence suggests that corruption, or a perceived lack of capability or competence, can be electorally decisive (see, e.g.,Ferraz and Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2008). We capture both core substantive elements in our model: voters care about ideological issues and common-value issues, but capability plays a very different role from the voter’s perspective depending on the type of issue.Footnote 6

The literature addressing “valence” considerations in ideological political competition has found mixed evidence regarding the impact of valence advantages on ideological platforms. Some have found that valence advantages allow politicians to move away from a median voter (Burden, Reference Burden2004; Dodlova and Zudenkova, Reference Dodlova and Zudenkova2021), while others have found that politician quality on valence issues push politicians toward the median voter (Stone and Simas, Reference Stone and Simas2010). Typically, the measurement of valence includes considerations about the politician’s capability, effectiveness, or competence. Allowing these aspects to be both desirable from a selection perspective, while also increasing the effectiveness of a politician’s platform implementation, allows us to show how these disparate empirical findings can emerge from a common framework. Our model outlines a mechanism by which voters might care about a politician’s policymaking capability, rather than simply black-boxing the value of policymaking into an additive valence term voters care about by fiat.

2. The model

Our theory proceeds over two stages: (1) politicians publicly announce an ideological policy platform that they are committed to implementing to the best of their abilities; (2) a decisive voter sees these platforms and chooses between politicians. The key ingredient in our model is that politicians differ not only in terms of their ideological preferences but also in terms of their capability, which determines their ability to implement both ideological and nonpartisan policy objectives.

In the first stage, a leftist politician, L, and a rightist politician, R, who are indexed by ![]() $i \in \{L,R\}$, simultaneously choose an ideological platform

$i \in \{L,R\}$, simultaneously choose an ideological platform ![]() $x_i \in \mathbb{R}$. Platforms represent the ideological (spatial) policy that politician i will imperfectly implement. A politician’s capability,

$x_i \in \mathbb{R}$. Platforms represent the ideological (spatial) policy that politician i will imperfectly implement. A politician’s capability, ![]() $c_i \in [0,1]$, determines her overall efficacy at implementing both ideological and nonpartisan policies. The policy a politician with platform xi implements depends on the status quo from past ideological policies, formalized by an exogenous status quo,

$c_i \in [0,1]$, determines her overall efficacy at implementing both ideological and nonpartisan policies. The policy a politician with platform xi implements depends on the status quo from past ideological policies, formalized by an exogenous status quo, ![]() $s \in \mathbb{R}$. In the second stage, there is an election which is decided by a decisive representative voter who, after observing the platform proposals of politicians,

$s \in \mathbb{R}$. In the second stage, there is an election which is decided by a decisive representative voter who, after observing the platform proposals of politicians, ![]() $(x_L,x_R)$, makes a vote choice, υ, between L and R.

$(x_L,x_R)$, makes a vote choice, υ, between L and R.

Platforms and the status quo produce a policy outcome according to a smooth function ![]() $\pi(x_i ; c_i , s)$, which strictly increases in xi and s and whose image is between xi and s. Moreover,

$\pi(x_i ; c_i , s)$, which strictly increases in xi and s and whose image is between xi and s. Moreover, ![]() $|x_i - \pi(x_i ; c_i , s)|$ monotonically decreases in ci,

$|x_i - \pi(x_i ; c_i , s)|$ monotonically decreases in ci, ![]() $|s - \pi(x_i ; c_i, s)|$ monotonically increases in ci, which says that capability pulls policy toward a politician’s platform and further from the status quo. Furthermore, to reflect that capability is more consequential for policy the greater the disconnect between platform and status quo, we assume that for all

$|s - \pi(x_i ; c_i, s)|$ monotonically increases in ci, which says that capability pulls policy toward a politician’s platform and further from the status quo. Furthermore, to reflect that capability is more consequential for policy the greater the disconnect between platform and status quo, we assume that for all ![]() $c \in (0,1)$,

$c \in (0,1)$, ![]() $\lim_{s \to \pm \infty} \pi(x;c,s) = \pm \infty$ and

$\lim_{s \to \pm \infty} \pi(x;c,s) = \pm \infty$ and ![]() $\lim_{x \to \pm \infty} \pi(x;c,s) = \pm \infty$, with

$\lim_{x \to \pm \infty} \pi(x;c,s) = \pm \infty$, with  $\tfrac{\partial^2 \pi}{\partial c_i \partial x_i} \gt 0$.Footnote 7

$\tfrac{\partial^2 \pi}{\partial c_i \partial x_i} \gt 0$.Footnote 7

Politicians also differ in their ideological preferences. Politician i’s ideological position is characterized by her ideal point yi, where ![]() $y_L \lt y_R$, and her payoff is

$y_L \lt y_R$, and her payoff is

which is the distance between i’s ideal point and the policy that is implemented.Footnote 8

The voter’s preferences over ideological policies are characterized by an ideal point, which we normalize to 0. The substantive importance of this normalization is that we focus on a voter who is relatively moderate, meaning that ![]() $y_L \lt 0 \lt y_R$. We also assume that politician ideal points are symmetric around the voter, i.e.,

$y_L \lt 0 \lt y_R$. We also assume that politician ideal points are symmetric around the voter, i.e., ![]() $-y_L = y_R$. Additionally, the voter values nonpartisan issues, and we capture this by the salience of capability

$-y_L = y_R$. Additionally, the voter values nonpartisan issues, and we capture this by the salience of capability ![]() $\alpha \in [0,1]$, which is normalized so that when α = 1, the voter does not value ideological policies, and when α = 0, the voter does not directly value capability.Footnote 9

$\alpha \in [0,1]$, which is normalized so that when α = 1, the voter does not value ideological policies, and when α = 0, the voter does not directly value capability.Footnote 9

The representative voter’s payoff from politician i being elected is

where ɛi is a preference shock known only to the voter, i.e., it is realized after the platform choices but before the election. We call ![]() $\varepsilon \equiv \varepsilon_R-\varepsilon_L$ the residual valence of the representative voter, which represents factors that determine the voter’s preference independent of ideological policies and politician capability. The voter’s residual valence is distributed according to a uniform distribution on the interval

$\varepsilon \equiv \varepsilon_R-\varepsilon_L$ the residual valence of the representative voter, which represents factors that determine the voter’s preference independent of ideological policies and politician capability. The voter’s residual valence is distributed according to a uniform distribution on the interval  $\left[\frac{-1}{\psi},\frac{1}{\psi}\right]$, where ψ > 0 measures the variance of the residual valence.

$\left[\frac{-1}{\psi},\frac{1}{\psi}\right]$, where ψ > 0 measures the variance of the residual valence.

To focus our presentation, we restrict attention to cases where there is sufficient uncertainty about the electoral outcome that campaigning is worthwhile, which occurs whenever  $\psi \lt \frac{3}{c_L - c_R}$. We also focus on cases where, in principle, both politicians can win the election with positive probability, which requires that the capability-advantaged politician, L, is ideologically extreme enough relative to the representative voter, which formally corresponds to

$\psi \lt \frac{3}{c_L - c_R}$. We also focus on cases where, in principle, both politicians can win the election with positive probability, which requires that the capability-advantaged politician, L, is ideologically extreme enough relative to the representative voter, which formally corresponds to  $y_L \lt \frac{1-\alpha \psi (c_L-c_R)}{\psi (1 - \alpha)}$. These two assumptions allow us to focus on cases where politicians’ policy choices are interior, i.e., contained in the interval

$y_L \lt \frac{1-\alpha \psi (c_L-c_R)}{\psi (1 - \alpha)}$. These two assumptions allow us to focus on cases where politicians’ policy choices are interior, i.e., contained in the interval ![]() $(y_L,y_R)$.Footnote 10

$(y_L,y_R)$.Footnote 10

We focus on Nash equilibria in weakly undominated strategies. Since voting is costless, the representative voter never abstains, and in the nongeneric event that the voter is indifferent between politicians, we assume she votes for the capability-advantaged politician.

2.1. Comments on the model

Valence is orthogonal to ideology and is commonly interpreted as containing capability (among other factors). In our model, capability affects a politician’s performance on ideological policies and hence is not entirely separate from ideological concerns. We thus essentially unpack the traditional role of valence into two components. First, things related to a politician’s ability to get things done, which cannot be fully separated from the implementation of ideological policies. Second, other attributes that are truly orthogonal to policy implementation, which we fold into the residual valence of the representative voter. These latter features can be specific to a particular election or something that is associated with a party rather than a politician, similar to incumbency advantage.

In our model, we assume that politicians are committed to implementing their ideological platforms, i.e., they cannot campaign on an ideological platform and completely ignore it once in office. We do this to focus attention on the role of capability, especially concerning its effect on how well a politician implements her ideological platform. While there may be reasons for politicians to profess a platform that they do not work toward implementing, if there were no connection between the professed platform and the implemented policy, then voters would ignore platforms entirely, expecting politicians to implement their ideal points. Then, since ![]() $y_L = - y_R$, capability would become a liability for the capability-advantaged politician who would like to commit to not use her full competence. When the ideal points of politicians are sufficiently extreme, our model where politicians commit to platforms but not to using less than full capability, and one with an inability to commit to platforms but where politicians commit to underprovide capability, would yield the same results.

$y_L = - y_R$, capability would become a liability for the capability-advantaged politician who would like to commit to not use her full competence. When the ideal points of politicians are sufficiently extreme, our model where politicians commit to platforms but not to using less than full capability, and one with an inability to commit to platforms but where politicians commit to underprovide capability, would yield the same results.

Platforms in our model should be thought of as party pledges, which depend on the capability of the politician (Vodová, Reference Vodová2021), and are more likely to be taken more seriously if the politician has demonstrated capability over some issue area (Dupont et al., Reference Dupont, Bytzek, Steffens and Schneider2019). The salience of capability is a way of capturing electoral selection in our model. It would be straightforward, as is done in standard career-concerns models of political accountability, to introduce a second stage where the politician makes policy choices. In such contexts, α would represent the voter’s continuation value from this more elaborate game (by sequential rationality).

We are interested in how capability influences electoral competition, which means that we need a model where electoral platforms respond to changes in capability, but not through effects on her own policy preferences, but through how it affects her platform choices in response to electoral concerns. This is why the payoff specifications we adopt are useful—they focus attention precisely on the substantive channels we intend to study, and nothing else (Paine and Tyson, Reference Paine, Tyson, Berg-Schlosser, Badie and Morlino2020).Footnote 11 Our formulation is thus motivated by a need to maintain conceptual clarity, to better connect with existing concepts in voter behavior, rather than a desire to provide a literal description of “real” voters. Similarly, our formulation of the policy function, π, is not meant to reflect the policy formation process, but to reflect how the difference between platforms and policies depends on the capability of politicians, and how voters react to this difference.

We stress that one gets a fairly standard probabilistic voting model from ours by setting ![]() $c_L = c_R = 1$ and α = 0, i.e., by removing the role of capability in the model. This is a desirable feature of our model for at least two reasons. First, it means that our model connects naturally to existing models of electoral competition, implying that canonical formulations of probabilistic voting are a natural baseline. Second, it also shows that our results, which deviate from those in canonical models of electoral competition, are the consequence of politician capability, rather than irregular features of our model of electoral competition, relative to the standard model, similar to a causal effect (Paine and Tyson, Reference Paine, Tyson, Berg-Schlosser, Badie and Morlino2020).

$c_L = c_R = 1$ and α = 0, i.e., by removing the role of capability in the model. This is a desirable feature of our model for at least two reasons. First, it means that our model connects naturally to existing models of electoral competition, implying that canonical formulations of probabilistic voting are a natural baseline. Second, it also shows that our results, which deviate from those in canonical models of electoral competition, are the consequence of politician capability, rather than irregular features of our model of electoral competition, relative to the standard model, similar to a causal effect (Paine and Tyson, Reference Paine, Tyson, Berg-Schlosser, Badie and Morlino2020).

In our model, capability does not constrain the ideological policy ambitions of politicians. This essentially allows even an incompetent politician to achieve their preferred policy (i.e., the policy they would like to use to compete). We blackbox the direct value of competence to voters, which can be thought of as a politician’s capability of achieving nonideological policy ambitions. In this way, capability in our model can be thought of as what constrains politicians’ nonideological policy ambitions, which also affects what platforms she must pursue to achieve her ideological policy ambitions. Our model focuses on voters’ perception of the relationship between campaign pledges and policy and how this perception impacts electoral campaign platforms. Our results are largely the same if capability also constrained politicians’ ideological policy ambitions.

3.The representative voter

We begin our analysis with the representative voter, who, in the last stage of the game, takes the ideological policy platforms and capability profiles of politicians L and R as given, and chooses how to vote. When she makes her decision, the voter knows that the policy actually implemented by politician i follows from ![]() $\pi_i = \pi (x_i ; c_i , s)$ and depends on i’s platform, xi, her capability, ci, and the status quo, s.Footnote 12

$\pi_i = \pi (x_i ; c_i , s)$ and depends on i’s platform, xi, her capability, ci, and the status quo, s.Footnote 12

The representative voter in our model is motivated by both ideological and nonpartisan concerns, captured in our model by two components. First is the capability gap,

which, because the leftist politician enjoys a capability advantage, γ > 0.Footnote 13 The capability gap measures the difference between L and R in terms of their ability to achieve various policy objectives, regardless of whether those policy objectives are ideological in nature (like tax policy or corporate welfare) or nonpartisan (like natural disasters or public health crises). Second, the voter’s decision depends on how far ideological policies are from her most preferred policy (i.e., her ideal point 0). This is measured by the ideological policy gap,

These two substantive forces, the capability and policy gaps, jointly determine the voter’s preference between politicians L and R.

Recalling that the voter’s private residual valence is given by ![]() $\varepsilon = \varepsilon_R - \varepsilon_L$, for a fixed ideological platform,

$\varepsilon = \varepsilon_R - \varepsilon_L$, for a fixed ideological platform, ![]() $(x_L, x_R)$, and capability profile,

$(x_L, x_R)$, and capability profile, ![]() $(c_L,c_R)$, the residual valence for the indifferent voter, denoted by

$(c_L,c_R)$, the residual valence for the indifferent voter, denoted by ![]() $\varepsilon^*$, solves

$\varepsilon^*$, solves

If the voter’s residual valence is to the left, specifically, ![]() $\varepsilon \lt \varepsilon^*$, then she strictly prefers the leftist politician, and similarly, if the voter’s residual valence is to the right, i.e.,

$\varepsilon \lt \varepsilon^*$, then she strictly prefers the leftist politician, and similarly, if the voter’s residual valence is to the right, i.e., ![]() $\varepsilon \gt \varepsilon^*$, then she strictly prefers the rightist politician.

$\varepsilon \gt \varepsilon^*$, then she strictly prefers the rightist politician.

Lemma 1. For a fixed ideological platform, ![]() $(x_L, x_R)$, and capability profile,

$(x_L, x_R)$, and capability profile, ![]() $(c_L,c_R)$, the representative voter’s vote choice, v, is determined by the cutoff:

$(c_L,c_R)$, the representative voter’s vote choice, v, is determined by the cutoff:

where

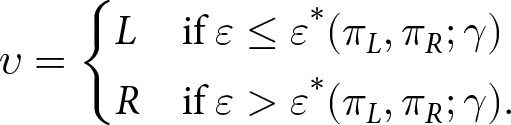

\begin{equation*} \upsilon =

\begin{cases}

L & \text{if}\ \varepsilon \le \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) \\

R & \text{if}\ \varepsilon \gt \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) .

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \upsilon =

\begin{cases}

L & \text{if}\ \varepsilon \le \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) \\

R & \text{if}\ \varepsilon \gt \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) .

\end{cases}

\end{equation*} Lemma 1 presents the voter’s decision rule in terms of the set of residual valences for which she prefers L instead of R, and vice versa. Since ![]() $\varepsilon^*$ is the cutoff where the decisive voter’s preference switches from L to R (as ɛ increases), changes in substantive factors that increase

$\varepsilon^*$ is the cutoff where the decisive voter’s preference switches from L to R (as ɛ increases), changes in substantive factors that increase ![]() $\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$ are those that lead the voter to become more inclined to vote for L, and any change that decreases

$\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$ are those that lead the voter to become more inclined to vote for L, and any change that decreases ![]() $\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$ implies that the voter is becoming more inclined to vote for R.

$\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$ implies that the voter is becoming more inclined to vote for R.

Inspection of (2) highlights three distinct substantive forces which are critical for understanding how the voter evaluates politicians when capability influences politicians’ effectiveness at implementing ideological policies. The first term in (2) is the capability gap, γ, and an increase in γ leads to an (all-else-equal) increase in ![]() $\varepsilon^*$, thus, as L’s capability advantage gets larger, the voter is more willing to vote for L. The second term in (2),

$\varepsilon^*$, thus, as L’s capability advantage gets larger, the voter is more willing to vote for L. The second term in (2), ![]() $\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$, is the ideological policy gap, and since

$\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$, is the ideological policy gap, and since ![]() $\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$ increases in

$\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$ increases in ![]() $|\pi_R |$ and decreases in

$|\pi_R |$ and decreases in ![]() $|\pi_L |$, the voter becomes more inclined to vote for L as πR increases and as πL decreases. The final ingredient in

$|\pi_L |$, the voter becomes more inclined to vote for L as πR increases and as πL decreases. The final ingredient in ![]() $\varepsilon^*$ is the voter’s salience of capability, α. As capability becomes more salient, i.e., as α increases, the importance of the capability gap increases while that of the policy gap decreases.

$\varepsilon^*$ is the voter’s salience of capability, α. As capability becomes more salient, i.e., as α increases, the importance of the capability gap increases while that of the policy gap decreases.

4. Equilibrium platforms and policies

We now shift our focus to politicians, who choose their platforms simultaneously, taking into account the downstream influence of their platform choices on their electoral prospects. When politicians choose the ideological platforms that they intend to implement (should they win the election), they do not yet know the representative voter’s residual valence, ɛ. Instead, they know only that the decisive voter’s residual valence is uniformly distributed on the interval  $\left[\frac{-1}{\psi},\frac{1}{\psi}\right]$, and that the voter’s decision rule is

$\left[\frac{-1}{\psi},\frac{1}{\psi}\right]$, and that the voter’s decision rule is ![]() $\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$. Politicians thus face some risk when choosing platforms because some ideological policies, which they may favor personally, entail a larger risk of losing the election, and the degree to which politicians face this kind of uncertainty is measured by ψ. When ψ is large (meaning

$\varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma)$. Politicians thus face some risk when choosing platforms because some ideological policies, which they may favor personally, entail a larger risk of losing the election, and the degree to which politicians face this kind of uncertainty is measured by ψ. When ψ is large (meaning ![]() ${1}/{\psi}$ is small), the residual valence of the voter is relatively well known, as opposed to when ψ is small (i.e.,

${1}/{\psi}$ is small), the residual valence of the voter is relatively well known, as opposed to when ψ is small (i.e., ![]() ${1}/{\psi}$ is large), perhaps due to increased voter polarization since the last election.

${1}/{\psi}$ is large), perhaps due to increased voter polarization since the last election.

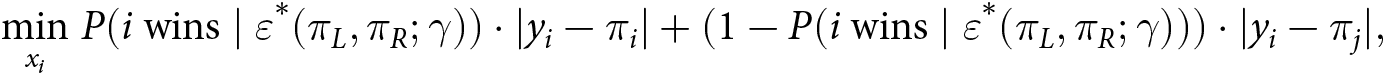

Proceeding to the politicians’ platform choices, politician i chooses her platform to solve:

\begin{equation*}

\underset{x_i }{\min} \; P( i\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) \cdot |y_i - \pi_i | + (1- P(i\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) ) \cdot |y_i - \pi_j | ,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\underset{x_i }{\min} \; P( i\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) \cdot |y_i - \pi_i | + (1- P(i\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) ) \cdot |y_i - \pi_j | ,

\end{equation*} where politician i’s platform choice, xi, enters her decision problem because ![]() $\pi_i = \pi(x_i ; c_i, s)$. Each politician treats the voter’s decision rule, and her opponent’s platform, as fixed, so from Lemma 1, and the uniform distribution, we can simplify the expression for i’s probability of winning the election, which for L, is

$\pi_i = \pi(x_i ; c_i, s)$. Each politician treats the voter’s decision rule, and her opponent’s platform, as fixed, so from Lemma 1, and the uniform distribution, we can simplify the expression for i’s probability of winning the election, which for L, is

\begin{align}

P( L\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) & = P(\varepsilon \le \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) =P( \varepsilon \le (1-\alpha)\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)+ \alpha \gamma )) \nonumber \\ &

= \min \left \{1, \max \left \{0, \frac{\psi((1-\alpha)\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R) + \alpha \gamma) + 1}{2} \right \} \right \} .

\end{align}

\begin{align}

P( L\ \text{wins} \mid \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) & = P(\varepsilon \le \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma) ) =P( \varepsilon \le (1-\alpha)\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)+ \alpha \gamma )) \nonumber \\ &

= \min \left \{1, \max \left \{0, \frac{\psi((1-\alpha)\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R) + \alpha \gamma) + 1}{2} \right \} \right \} .

\end{align}The calculation for R’s win probability is similar and is in the appendix.

Examining the probability L wins, which depends directly on the (exogenous) capability gap, γ, as well as the (endogenously determined) ideological policy gap, ![]() $\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$, captures politicians’ anticipation of how their platform choices will affect their likelihood of winning the election. Inspection of (3) shows that an increase in the capability gap and an increase in the ideological policy gap each increase the probability L wins.

$\Delta(\pi_L, \pi_R)$, captures politicians’ anticipation of how their platform choices will affect their likelihood of winning the election. Inspection of (3) shows that an increase in the capability gap and an increase in the ideological policy gap each increase the probability L wins.

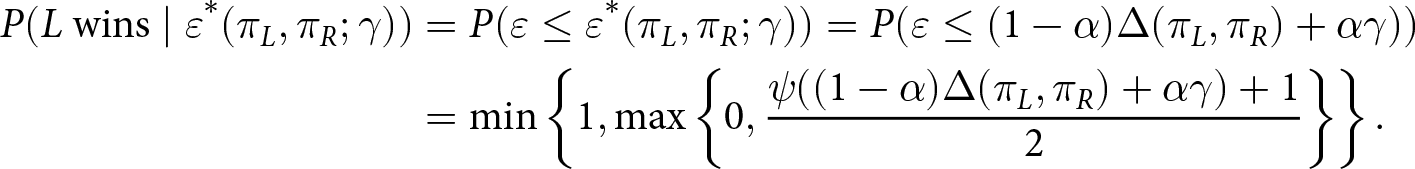

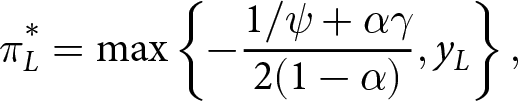

Proposition 1.

There exists a unique equilibrium, ![]() $(x^*_L, x^*_R, \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma))$, where the equilibrium policies,

$(x^*_L, x^*_R, \varepsilon^*(\pi_L,\pi_R ; \gamma))$, where the equilibrium policies, ![]() $\pi_L^*$ and

$\pi_L^*$ and ![]() $\pi_R^*$, satisfy

$\pi_R^*$, satisfy

and are

\begin{equation}

\pi_L^* = \max \left\{- \frac{{1}/{\psi} + \alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} , y_L \right\},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\pi_L^* = \max \left\{- \frac{{1}/{\psi} + \alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} , y_L \right\},

\end{equation}and

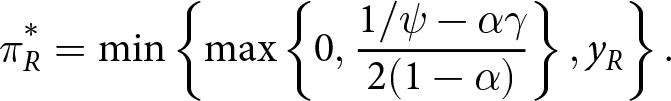

\begin{equation}

\pi_R^* = \min \left\{ \max \left \{0, \frac{{1}/{\psi}- \alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} \right \} , y_R \right\} .

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\pi_R^* = \min \left\{ \max \left \{0, \frac{{1}/{\psi}- \alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} \right \} , y_R \right\} .

\end{equation} The equilibrium platform for ![]() $i \in \{L, R\}$,

$i \in \{L, R\}$, ![]() $x_i^*$, solves

$x_i^*$, solves

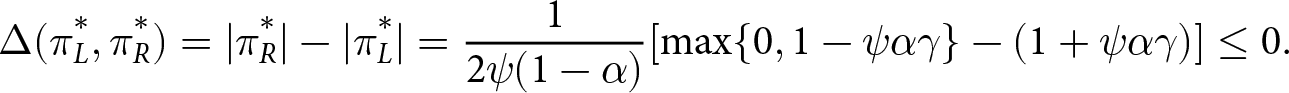

Moreover, the ideological policy gap, at equilibrium, is

\begin{equation*} \Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) = |\pi_R^*| - |\pi_L^*| = \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} [\max \{0, 1- \psi \alpha \gamma \} - (1+ \psi \alpha \gamma)] \leq 0. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) = |\pi_R^*| - |\pi_L^*| = \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} [\max \{0, 1- \psi \alpha \gamma \} - (1+ \psi \alpha \gamma)] \leq 0. \end{equation*} That ![]() $ \Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) \le 0$ reflects L’s capability advantage. Each equilibrium policy essentially constitutes a shift away from the representative voter’s ideal point. For L, (5) becomes

$ \Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) \le 0$ reflects L’s capability advantage. Each equilibrium policy essentially constitutes a shift away from the representative voter’s ideal point. For L, (5) becomes

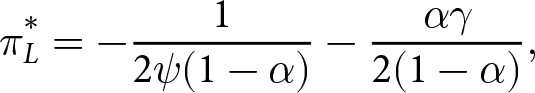

\begin{equation}

\pi_L^* = - \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} - \frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} ,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\pi_L^* = - \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} - \frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} ,

\end{equation}and for R, (6) can be written as

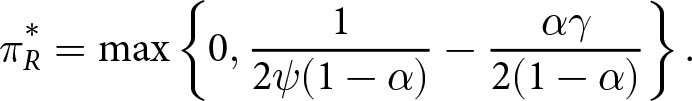

\begin{equation}

\pi_R^* = \max \left \{0, \frac{1}{2\psi(1-\alpha)} - \frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} \right \} .

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\pi_R^* = \max \left \{0, \frac{1}{2\psi(1-\alpha)} - \frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} \right \} .

\end{equation} Comparing (8) and (9) highlights the role of uncertainty about the representative voter’s residual valence, which causes L to shift leftward and R to shift rightward (from 0) by  $ \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)}$. This kind of shift is common in probabilistic voting models as it mitigates the forces typically associated with median-voter style results that lead politicians toward centrist policy positions. Indeed, if there were no capability gap, so that γ = 0, then L’s policy and R’s policy would be equidistant from the voter’s ideal point, i.e., they would both be

$ \frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)}$. This kind of shift is common in probabilistic voting models as it mitigates the forces typically associated with median-voter style results that lead politicians toward centrist policy positions. Indeed, if there were no capability gap, so that γ = 0, then L’s policy and R’s policy would be equidistant from the voter’s ideal point, i.e., they would both be  $\frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} $ from the voter.

$\frac{1}{2 \psi (1-\alpha)} $ from the voter.

What’s novel to our setup is the second terms in (8) and (9), which for both L and R constitute a leftward shift of  $\frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} $. The capability advantage enjoyed by L pushes both L and R to the left. The presence of a capability gap, γ > 0, allows L—the capability-advantaged politician—to move further from the voter’s ideal point, but forces R to moderate, pulling her policy leftward. If the capability gap is large enough, then R goes all the way to the representative voter’s ideal point, 0.

$\frac{\alpha \gamma}{2(1-\alpha)} $. The capability advantage enjoyed by L pushes both L and R to the left. The presence of a capability gap, γ > 0, allows L—the capability-advantaged politician—to move further from the voter’s ideal point, but forces R to moderate, pulling her policy leftward. If the capability gap is large enough, then R goes all the way to the representative voter’s ideal point, 0.

Proposition 1 establishes that in any equilibrium ideological policies are “moderate” in the sense that (4) holds, which says that equilibrium policies are bounded by the ideological positions of politicians (captured by their ideal points yL and yR) and separated by the ideal point of the decisive voter, which is normalized at 0. This property is common in conventional models of electoral competition with policy-motivated politicians, but critically, in our model this is not true of the ideological platforms on which politicians compete. This crucially depends on the linkage between platforms and policies, and how this linkage is affected by capability.

5. Populism, extremism, and the status quo effect

What distinguishes our model from most models of electoral competition is that a politician’s capability determines the extent to which she can implement her ideological platform, as well as respond to other nonpartisan issues, like a national crisis. The other ingredient affecting policy in the model is the status quo, s, because it anchors policies relative to the politician’s platform. We interpret the status quo, s, in our model, as capturing existing political legacies, and thus, our analysis isolates how such legacies impact politicians’ platforms, and consequently, the observed nature of electoral competition.

The status quo impacts platform competition in our model by introducing a separate policy position that politicians compete with (in addition to each other).

Proposition 2.

[The Status Quo Effect] There exist ![]() $\bar{s} \leq 0$ and

$\bar{s} \leq 0$ and ![]() $\bar{s} \geq 0$ such that if

$\bar{s} \geq 0$ such that if

(a) the status quo is sufficiently to the left, i.e., if

$s \leq \bar{s}$, then platforms will be to the right of the voter:

$s \leq \bar{s}$, then platforms will be to the right of the voter:  $0 \leq x_L^* \lt x_R^*$;

$0 \leq x_L^* \lt x_R^*$;(b) the status quo is centrist, i.e., if

$s \in (\bar{s},\bar{s}]$, then the voter’s ideal point is in between platforms:

$s \in (\bar{s},\bar{s}]$, then the voter’s ideal point is in between platforms:  $x_L^* \lt 0 \le x_R^*$;

$x_L^* \lt 0 \le x_R^*$;(c) the status quo is sufficiently to the right, i.e.,

$s \gt \bar{s}$, then platforms will be to the left of the voter:

$s \gt \bar{s}$, then platforms will be to the left of the voter:  $x_L^* \lt 0$ and

$x_L^* \lt 0$ and  $x_R^* \lt 0$.

$x_R^* \lt 0$.

This result establishes that platforms are ordered the same way as latent policies, i.e., ![]() $x_L^* \lt 0 \lt x_R^*$, when status quos are relatively centrist,

$x_L^* \lt 0 \lt x_R^*$, when status quos are relatively centrist, ![]() $s \in (\underline{s}, \overline{s}]$. In this case, both politicians announce platforms to pull policy away from the voter. Thus, a moderate status quo structures ideological competition around the traditional left-right orientation, with L competing with a leftist platform and R choosing a rightist platform. When status quos are relatively extreme (in either direction), then platform competition is qualitatively different.

$s \in (\underline{s}, \overline{s}]$. In this case, both politicians announce platforms to pull policy away from the voter. Thus, a moderate status quo structures ideological competition around the traditional left-right orientation, with L competing with a leftist platform and R choosing a rightist platform. When status quos are relatively extreme (in either direction), then platform competition is qualitatively different.

Imperfect capability implies that the logic normally associated with the left-right ideological orientation of political competition breaks down. In these cases, politicians end up facing two competitors: their opponent and an extreme status quo. The further away the status quo is from the voter, the more salient the status quo is as an opponent policy, and the larger incentive the politicians have to choose platforms in the opposite direction of s, even if it means getting closer to each other. Proposition 2 provides a novel rationale for, and characterization of, populist electoral competition: it is when the dominant issue of electoral competition is not between candidates but with an extreme status quo.

The influence of an extreme status quo on the platforms of politicians, exhibited in our model, is illustrated by populist campaigns in several Latin American countries. For instance, leaders like Evo Morales, who gained political prominence by campaigning on aggressively leftist populist platforms, following the fall of the right-wing dictatorship in Bolivia. Proposition 2 shows that when the status quo, s, is to the right (left), and far from the voter’s ideal point, 0, then both the leftist and the rightist politicians campaign on platforms which are to the left (right) of the voter. Populism features aggressive political campaigns that extol “the people” against an elite establishment who is considered out of touch with the people (e.g., Mudde and Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Kaltwasser, Freeden and Stears2013), which fits naturally into our model where the decisive voter represents the “people” and elite interests are represented by the status quo, s. Our result shows when the status quo is sufficiently extreme, both politicians propose platforms that are to the left or to the right of the voter.

From Proposition 1, ![]() $\Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) \le 0$, which means that R’s implemented policy is more moderate than L’s. It is tempting to conclude, then, that capability and ideological extremism are positively related. However, as the previous discussion about status quos makes clear, platforms and policies are not equivalent. Thus, this pattern may not be replicated when it comes to platforms. There are three channels that lead to relative platform moderation (or extremism) in our model. First, capability advantages can be leveraged for policy gains, which allows L to choose a platform that is further to the left. Second, capability leads voters to take a politician’s platform more seriously, leading R to campaign on a platform that is more extreme than the policy she ultimately implements. Finally, imperfect capability means that the status quo remains relevant. In order to focus on how the first two channels that are more directly related to capability, we let s = 0 in the following proposition.Footnote 14 We provide a sufficient condition for capability and platform extremism to be negatively related.

$\Delta(\pi_L^*, \pi_R^*) \le 0$, which means that R’s implemented policy is more moderate than L’s. It is tempting to conclude, then, that capability and ideological extremism are positively related. However, as the previous discussion about status quos makes clear, platforms and policies are not equivalent. Thus, this pattern may not be replicated when it comes to platforms. There are three channels that lead to relative platform moderation (or extremism) in our model. First, capability advantages can be leveraged for policy gains, which allows L to choose a platform that is further to the left. Second, capability leads voters to take a politician’s platform more seriously, leading R to campaign on a platform that is more extreme than the policy she ultimately implements. Finally, imperfect capability means that the status quo remains relevant. In order to focus on how the first two channels that are more directly related to capability, we let s = 0 in the following proposition.Footnote 14 We provide a sufficient condition for capability and platform extremism to be negatively related.

Proposition 3.

[Capability and Extremism] Let s = 0. There exists an ![]() $\hat{\alpha}$, with

$\hat{\alpha}$, with ![]() $0 \lt \hat{\alpha} \le 1$, such that if

$0 \lt \hat{\alpha} \le 1$, such that if ![]() $\alpha \lt \hat{\alpha}$, then R’s platform,

$\alpha \lt \hat{\alpha}$, then R’s platform, ![]() $x^*_R$, is further from the voter’s ideal point, 0, than L’s platform,

$x^*_R$, is further from the voter’s ideal point, 0, than L’s platform, ![]() $x^*_L$.

$x^*_L$.

Proposition 3 establishes that a key force determining the relationship between capability and extremism is the salience of capability, α. We establish that in relatively ideologically motivated polities, i.e., with low α, capability and extremism are negatively related. This means that low salience of capability is associated with a more capable politician being less extreme. Additionally, policy extremism is asymmetric, in the sense that L’s policy diverges further from the voter than R’s, and this asymmetry is a function of α. With higher α, L can leverage the capability gap and achieve a more extreme ideological policy. So when α is high, the distance between L’s policy and the voter is much bigger than that between R’s policy and the voter. A low α means that L and R’s policies are close to equidistant from the voter, and because R is capability-disadvantaged, there is a larger gap between her policy and platform. Consequently, if α is small enough, R’s platform is further from the voter than L’s platform.

For policymakers who are purely interested in policy, and its relation to capability gaps, an extreme platform may be less concerning. Our model suggests that in electorates that value ideology relative to capability (low α), an extreme platform is not likely to translate to extreme policies because it is likely espoused by the incapable politician. If α is low enough, a politician’s platform is extreme because she is incapable and unlikely to achieve most of her ideological goals. Instead, when α is high, it is capability-advantaged politicians that are the more extreme, and concerns of this sort are more justified.Footnote 15

Before moving on, we note that valence is typically a catch-all term encapsulating various considerations that are important electorally but which are orthogonal to ideological issues—and capability is frequently used as an example. But, a critical difference between our model and those of valence is that capability is not completely orthogonal to ideological concerns, since it partially determines how much of a politician’s ideological platform gets implemented—and the voter is aware of this. Proposition 3 shows the importance of disentangling different dimensions of nonideological political competition, showing that the correlation between politician capability and ideological extremism (of platforms) can be negative or positive, depending on the salience of capability. Our model thus provides a common framework that gives rise to seemingly disparate empirical findings seeking to identify the effect of valence on ideological extremism by isolating capability which affects both ideological extremism and valence (traditionally understood).

6. Empirical implications

The contrast between politician i’s platform, ![]() $x^*_i$, and the policy she implements,

$x^*_i$, and the policy she implements, ![]() $\pi^*_i$, highlights an important distinction: the ideological platforms politicians campaign on are not the same as the ideological policies that they ultimately implement. In this section, we investigate when exactly platforms serve as a good proxy for latent policy outcomes when it comes to empirically evaluating theories of electoral competition, and when platforms and policies are markedly different. This is important because politicians’ policies may be difficult to reliably measure in practice, since policies are often highly complex and take many years to materialize. Assessing when platforms can proxy for policies provides a theoretical foundation for using such proxies in the first place.

$\pi^*_i$, highlights an important distinction: the ideological platforms politicians campaign on are not the same as the ideological policies that they ultimately implement. In this section, we investigate when exactly platforms serve as a good proxy for latent policy outcomes when it comes to empirically evaluating theories of electoral competition, and when platforms and policies are markedly different. This is important because politicians’ policies may be difficult to reliably measure in practice, since policies are often highly complex and take many years to materialize. Assessing when platforms can proxy for policies provides a theoretical foundation for using such proxies in the first place.

Most formal work regarding electoral competition and valence advantages abstracts from the platform-policy linkage question by assuming that the platform is the policy that is implemented. The empirical work that evaluates the connection between valence and political competition generally focuses on platforms, or policy positions, rather than implemented policies. Platforms are typically measured either through the analysis of manifestos (Adams and Merrill III, Reference Adams and Merrill2009), speeches (Green and Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019), or expert/voter/politician surveys (Burden, Reference Burden2004; Stone and Simas, Reference Stone and Simas2010; Adams et al., Reference James, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011). The focus on these different measures of platforms, rather than the policies that are ultimately implemented by the electoral winner, is understandable given that platforms are more easily measured than the long-term policy implications of politicians’ tenure and, moreover, are available for both the winner and the loser of the election. Our model highlights that capability determines how closely platforms and policies coincide—and when they don’t.

We first focus on the salience of capability, α, which could come from a “shock” to the importance of politician capability among voters, due to national crises, public health emergencies, natural disasters, etc.

Proposition 4.

An increase in the salience of capability, α, causes a leftward shift of L’s policy, ![]() $\pi_L^*$, and

$\pi_L^*$, and

(i) when the capability gap is large relative to uncertainty, i.e.,

$\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, a leftward shift of R’s policy; and

$\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, a leftward shift of R’s policy; and(ii) when the capability gap is small relative to uncertainty, i.e.,

$\gamma \le \frac{1}{\psi}$, a rightward shift of R’s policy.

$\gamma \le \frac{1}{\psi}$, a rightward shift of R’s policy.

An increase in the salience of capability, i.e., an increase in α, makes the capability gap more important to the voter and moves L’s ideological policy further left. Instead, for R, who is capability-disadvantaged, such an increase only leads R to moderate policy under certain conditions. When the voter cares more about capability, L is more desirable to the voter, and as a consequence, L uses this advantage to gain more on policy, moving closer to her ideal point, yL. While a similar incentive to move to the left, thereby becoming more moderate, is present for R, there is another force. An increase in α also reduces the importance of ideological concerns. In particular, because increasing α makes the voter less responsive to changes in ideological platforms, the (marginal) benefit of moderating for R reduces with increased α. For R, the interaction of these two forces depends crucially on the magnitude of the capability gap, γ, relative to partisan uncertainty, ![]() $\frac{1}{\psi}$. When the capability gap is large relative to partisan uncertainty, i.e., when

$\frac{1}{\psi}$. When the capability gap is large relative to partisan uncertainty, i.e., when  $\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, then R moves to the left—in order to reduce the impact of the capability gap. By contrast, when

$\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, then R moves to the left—in order to reduce the impact of the capability gap. By contrast, when  $\gamma \leq \frac{1}{\psi}$, an increase in α magnifies the impact of partisan uncertainty much more than it does the capability gap. Consequently, R moves to the right as the salience of capability, α, increases.

$\gamma \leq \frac{1}{\psi}$, an increase in α magnifies the impact of partisan uncertainty much more than it does the capability gap. Consequently, R moves to the right as the salience of capability, α, increases.

We now consider the relationship between policies and platforms with respect to the salience of capability.

Proposition 5.

In any equilibrium,  $sign \left (\frac{\partial x_i^*}{\partial \alpha} \right) = sign \left(\tfrac{\partial \pi^*_i}{\partial \alpha} \right)$. An increase in the salience of capability, α, causes a leftward shift of platforms of both L and R if the capability gap is large relative to uncertainty, i.e.,

$sign \left (\frac{\partial x_i^*}{\partial \alpha} \right) = sign \left(\tfrac{\partial \pi^*_i}{\partial \alpha} \right)$. An increase in the salience of capability, α, causes a leftward shift of platforms of both L and R if the capability gap is large relative to uncertainty, i.e.,  $\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, and a leftward (rightward) shift of L(R)’s platform otherwise.

$\gamma \gt \frac{1}{\psi}$, and a leftward (rightward) shift of L(R)’s platform otherwise.

The first part of this result shows that the relationship between the salience of capability and the politicians’ platforms and the salience of capability and politicians’ policies is qualitatively the same. In particular, Proposition 5 shows that increasing α affects platforms and policies in the same direction. Empirically, this implies that if one can isolate the relationship between politicians’ platforms and the importance of politician capability to voters, be it polarization or moderation, the relationship between the salience of capability and politicians’ policies will be the same.

The second part of Proposition 5 illustrates the usefulness of the first part. Specifically, it connects the theoretical result from Proposition 4, which is extremely difficult to address in practice, to a more easily assessed effect, which is the influence of the salience of capability on platforms. This result implies that using a shock to the salience of capability and measuring the effect that shock has on politicians’ platforms (polarizing, moderating, etc.) will also identify the sign of the all-else-equal effect that shock will ultimately have on the policies implemented by the politicians.Footnote 16

We now consider the relationship between platforms and policies when there is a change to the platform-policy linkage and show that the convenient feature highlighted above no longer holds. In particular, changes to the capability gap have an ambiguous effect on electoral platforms compared to its unambiguous effect on policies. Recall that the capability gap is ![]() $\gamma = c_L-c_R$ and note that a change in γ can be brought about in two ways: either by changing cL or changing cR. We separately investigate the impact of increasing cL or decreasing cR, as both serve to increase the capability gap, but impact platforms differently.

$\gamma = c_L-c_R$ and note that a change in γ can be brought about in two ways: either by changing cL or changing cR. We separately investigate the impact of increasing cL or decreasing cR, as both serve to increase the capability gap, but impact platforms differently.

Proposition 6.

An increase in γ pushes L’s policy, ![]() $\pi^*_L$, strictly to the left and R’s policy,

$\pi^*_L$, strictly to the left and R’s policy, ![]() $\pi^*_R$, weakly to the left. If an increase in γ is facilitated by

$\pi^*_R$, weakly to the left. If an increase in γ is facilitated by

(1) an increase in cL, then

$x_R^*$ shifts leftward and

$x_R^*$ shifts leftward and  $x_L^*$ shifts leftward if and only if the status quo is far enough to the left,

$x_L^*$ shifts leftward if and only if the status quo is far enough to the left,(2) a decrease in cR, then

$x_L^*$ shifts leftward and

$x_L^*$ shifts leftward and  $x_R^*$ shifts leftward if and only if the status quo is far enough to the right.

$x_R^*$ shifts leftward if and only if the status quo is far enough to the right.

An increase in cL pushes R to moderate by moving her platform to the left, responding to the voter’s increased preference for L resulting from (nonideological) selection concerns. For L, however, there are two important forces. First, an increase in cL makes L more attractive to the voter, which she uses to move her platform leftward. Second—and more interestingly—an increase in cL also effectively makes L more ideologically extreme relative to the status quo. Fixing L’s platform, an increase in cL implies that the ideological policy L will implement will be closer to her platform. Depending on the location of the status quo, this might not be desirable for the voter, and L may be forced to move her platform to the right, thereby moderating, as her capability, cL, increases. Which of these effects dominate depends on the location and ideological extremity of the status quo, s.

An increase in cL moves L’s platform to the left when the status quo, s, is not too far to the right and moves it rightward otherwise. To see the logic more clearly, consider a status quo that is far to the right. In this case, L’s platform corrects for this extreme right status quo by choosing a platform that is extremely far to the left, possibly further away from the voter than the status quo. An increase in cL, then, is tantamount to making L more ideologically extreme, despite a larger capability gap. As a result, L moderates her platform to the right as her capability increases. The last part of Proposition 6 corresponding to an increase in the capability gap that results from a decrease in cR follows a similar logic, but where the directions are reversed. For instance, decreasing cR could shift ![]() $x_R^*$ to the right because decreased capability means that the voter takes R’s platforms less seriously, knowing that much of it will remain undone.

$x_R^*$ to the right because decreased capability means that the voter takes R’s platforms less seriously, knowing that much of it will remain undone.

The empirical import of Proposition 6 is to identify when changing the capability gap influences platforms and policies differently. In particular, the effect on platforms from changes to the capability gap is dependent on the source of the change, which is not the case for policies. Assuming a regular left-right configuration of platforms, an increase in the capability of the advantaged politician could moderate both platforms, both toward each other and the voter. In contrast, a decrease in the capability of the disadvantaged politician could lead to more extreme platforms. This is in contrast to the capability gap’s effect on policies, which always makes the capability-advantaged politician more extreme and moderates the capability-disadvantaged politician. This implies that platforms are not a sufficient statistic for policies in an empirical study that looks at the policy impact of capability and uses platforms as its primary measure of ideological positions.

Contrasting Propositions 5 and 6 highlights when platforms can serve as useful empirical proxies for policies. They show that when there is a shock to voter preferences, the effect on platforms and policies is qualitatively the same, and hence, measuring platforms is a useful measurement strategy, i.e., it has construct validity (Adcock and Collier, Reference Adcock and Collier2001; Slough and Tyson, Reference Slough and Tyson2023). For example, a shock to direct voter preference for capability through a health crisis such as COVID-19 has the same effect on platforms and policies. Indeed, Desai et al. Reference Desai, Frey and Tyson(Forthcoming) exploit this fact when documenting an increase in polarization in Brazil after the first wave of COVID-19 in the country. However, our results also show that a shock to the platform-policy linkage (making politicians’ disconnect between platform and policy larger or smaller) affects policies and platforms differently, and hence, platforms are not a useful measure for the impact on policy in this case.

7. Conclusion

A politician’s influence over ideological and nonpartisan policies depends on her overall talent or ability to implement her ambitions, and this depends on a number of factors including skill, experience, or persuasive talents. We develop a theory of electoral competition between two politicians, one who is left-leaning and another who is right-leaning, and a moderate representative voter. The novelty of our contribution comes from incorporating a politician’s capability, i.e., her ability to “get things done,” and studying how electoral competition, in terms of politicians’ platforms, depends on a capability gap, an ideological policy gap, the salience of capability for voters, as well as status quo policies.

The introduction of capability into our model introduces a role for a “status quo effect” in electoral competition, and our results thus provide a novel rationale for the link between extreme historical political legacies and populism—because such status quo legacies become the dominant dimension of electoral competition. Our results thus provide a novel way of classifying when left-vs-right political competition manifests, in short, when the status quo is relatively centrist. Moreover, we identify how extreme ideological status quos lead political competition to reflect competition with that status quo rather the ideological differences between politicians.

We conclude our analysis by considering the relationship between the platforms on which politicians compete and the policies they will ultimately implement. We focus on when platforms and policies react the same way to changes in the electoral environment. These results are useful because they suggest when platforms provide a good proxy for policies in empirical measurement. We show that changes to voter preferences, in particular the salience of capability, i.e., how much voters care directly about capability, impact policies and platforms the same way, whereas changes to the politicians, in particular changing the capability gap, lead to different effects on policy than on platforms. In particular, our analysis shows that the policy effects of increasing capability (and the capability gap) are relatively straightforward, but that the effect on platforms is less straightforward.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/.10.1017/psrm.2025.25.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emiel Awad, Peter Bils, Peter Buisseret, Marina Dodlova, Helios Herrera, Federica Izzo, Barton Lee, Clement Minaudier, Torsten Persson, Ronny Razin, Jesse Richman, Keith Schnakenberg, Dana Sisak, Galina Zudenkova, seminar participants at the London School of Economics and Political Science, Online Political Economy Seminar Series, Washington University at St. Louis, and Midwest Political Science Association annual meeting for helpful comments and conversations.