Introduction

In 1956, the Nordic Saami Council, now known simply as the Saami Council, was founded in Kárášjoka/Karasjok, on the Norwegian side of Sápmi, the traditional Sámi homeland (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004). The formation of this organisation came at a pivotal time, as it coincided with a wider political awakening within Sámi society, which led to the creation of a formalised civil society based on cultural associations and labour organisations (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto and Mörkenstam2008; Minde, Reference Minde1996). Then as now, the Nordic Saami Council represented the international dimension of this civil society – coordinating and connecting Sámi voices across the borders that divided them. At the time of its foundation, the Council’s efforts centred on organising periodic conferences between these civil society organisations. As time went on, these duties expanded to encompass speaking on behalf of their people on the world stage. The role of the Saami Council has evolved over the 70 years of its existence, positioning it as one of the oldest and most enduring Indigenous Peoples’ Organisations in the international arena.

Although it is of great importance for the political history of the Sámi, the evolution and role of the Saami Council have seldom been covered by research, at least until recently. If the organisation is mentioned at all, it often only appears as a mere footnote – usually in connection to the Sámi parliaments founded in the last quarter of the 20th century (Broderstad, Reference Broderstad2011; Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1999; Josefsen et al., Reference Josefsen, Mörkenstam and Saglie2014; Stępień et al., Reference Stępień, Petrétei and Koivurova2015). Despite this erasure, the Saami Council has been part of several key moments in international Indigenous people’s history, including the formation of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP), the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Peoples, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII), and lastly, the Arctic Council (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004).

As such, an examination of the Saami Council’s history is overdue, and so is a consideration of its role as an international actor. Throughout its history, the organisation has taken on the role of a diplomatic actor representing a people that remains divided across state borders. This situation of the Sámi is not unique among Indigenous peoples, though the phenomenon remains understudied nonetheless (Álvarez & Ovando, Reference Álvarez and Ovando2022). The study of such non-states acting on diplomatic impulses is often covered by a field known as paradiplomacy, a subfield of international relations (Cornago, Reference Cornago2000; Kuznetsov, Reference Kuznetsov2014; Lecours, Reference Lecours2002). This discipline has long focused on the activities of formal sub-state actors such as the German Länder or Canadian provinces, which remain something of an edge case within the wider literature, as nation-states continue to be seen as the main players in international diplomacy (Cornago, Reference Cornago2000). There has been an increasing interest in the role of other non-state actors more recently, though the mechanisms and extent of such operations have remained underexplored (Chater, Reference Chater2021; Landriault et al., Reference Landriault, Payette and Roussel2021).

The purpose of this study is two-fold. First, it will explore the Council’s organisational and political evolution, from its foundation in 1956 to its consolidation in the late 1990s, and highlight its changing role within Sámi society and as an Indigenous People’s Organisation (IPO). Second, it will examine how the Saami Council entered the wider world of international politics and how it began to become involved in activities that resemble diplomatic action. To fulfil these goals, this article will begin with an introduction to paradiplomacy as the key analytical lens through which to study the Saami Council as an Indigenous diplomatic actor. This will be followed by a brief background account introducing the Sámi and the political context of the Saami Council’s foundation. From there, the methodology used for this contribution will be explained in more detail. The case study was built using the process of data triangulation, meaning that a variety of secondary sources was used to fully capture every relevant detail of the historical development process. Building on this approach, the history of the Saami Council will then be presented, starting with the first actions that led to its formation and on through until the writing of Sámiráđđi 50 Jagi (Saami Council at 50 Years), a history of the organisation written by long-time member Leif Rantala. The article will conclude with an examination of how the organisation fits as a paradiplomatic actor and what this means for the study of non-state diplomatic action. Though the Saami Council may not appear to be a typical paradiplomatic actor, its diplomatic evolution throughout the years makes it a clear example of the blurring of the line between statehood and non-statehood on the world stage.

Theory: An Overview of Paradiplomacy and Stages of Paradiplomatic Activity

To begin, paradiplomacy can be considered both a theory and a concept that attempts to bridge the gap between formal diplomacy and the everyday realities of an interconnected world. Simply put, it is an attempt to theorise how and why subnational actors interact on the international stage (Kuznetsov, Reference Kuznetsov2014; Lecours, Reference Lecours2002; Paquin, Reference Paquin2020). Paradiplomacy was founded as a distinct discipline in the late 1980s and early 1990s through the work of authors such as Ivo Duchacek and Panayotis Soldatos, who first proposed models to explain how non-state diplomatic actors function (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986; Landriault et al., Reference Landriault, Payette and Roussel2021; Lecours, Reference Lecours2002; Paquin, Reference Paquin2020; Soldatos, Reference Soldatos1990). The reality of borders and the interconnected nature of neighbours that may exist far from the capital means that relationships between sub-state actors have been inevitable but seldom considered (Cornago, Reference Cornago2000). In the early years, the field focused on relatively few cases mostly within North America – with Quebec being one of the main focal points. As the field expanded, the scope of research began to include other examples of sub-state activity, though these remain somewhat rare (Álvarez & Ovando, Reference Álvarez and Ovando2022; Chater, Reference Chater2021; Meissner & Warner, Reference Meissner and Warner2021).

One of the more widespread frameworks used in the field is also one of the most enduring: Duchacek’s model of paradiplomatic activity (Kuznetsov, Reference Kuznetsov2014; Landriault et al., Reference Landriault, Payette and Roussel2021). According to this model, there are four conceptual forms or patterns of international activities that subnational actors conduct: transborder regional micro-diplomacy, transregional micro-diplomacy, global paradiplomacy, and the proto-diplomacy of a breakaway state (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986). Each describes a different form of subnational diplomacy – relating to a varying degree of closeness and complexity – that ranges from cross-border agreements between subnational actors, representation at regional or international fora, and the more eye-catching attempts at nation-building by secessionist states or regions. These designations are by no means fixed, and subnational actors can and will move along this spectrum at will.

On the least state-like end of the spectrum, we begin with the somewhat unwieldy transborder regional micro-diplomacy. In brief, this form of paradiplomatic action is the everyday diplomacy of subnational states, brought about by the need to coexist across borders with neighbours that share common interests (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986, pp. 240–243). This form of cooperation is inherent to most subnational constituent units within unitary states and is usually conducted through cross-border – and generally informal – meetings and agreements that focus on strictly local, often highly specific, issues that do not require the immediate involvement of the nation-state.

The second stage on the spectrum is transregional micro-diplomacy, which takes things a step further (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986, pp. 243–246). Unlike the transborder regional micro-diplomacy, the sub-states involved focus on a wider range of issues that go beyond simply the regional into the international. This oftentimes takes the form of missions abroad or agreements between sub-states. The establishment of city partnerships or regional fora between subnational states are typical examples of this form of paradiplomacy. What distinguishes this from a more state-level approach is the limited scope of such agreements or missions, both in expense and in aspiration.

The third stage, global paradiplomacy, takes the diplomatic actions of the previous stages and expands them to include not just peer actors but also fully recognised nation-states (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986, pp. 246–248, 274–277). Furthermore, this stage distinguishes itself through a higher level of sophistication and permanence. As such, physical offices or departments within the sub-state devoted to external relations are not uncommon. Actions that fall under this umbrella resemble the traditional model of diplomacy more properly – enacted and performed by a sub-state or non-state actor. That said, these diplomatic endeavours are not tied to aspirations towards greater independence or even sovereignty. Their goal lies more in expanding and maintaining business interests abroad rather than achieving international recognition (Cornago, Reference Cornago2000; Landriault et al., Reference Landriault, Payette and Roussel2021, pp. 3–4).

Finally, proto-diplomacy represents the fourth and final stage of paradiplomacy (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986, pp. 274–276). At this stage, the actions taken are intentionally akin to those of a nation-state, such as the establishment of permanent international missions and the cultivation of strong and comprehensive sub-state-to-state relationships. These types of arrangements tend to be very present in public perception as they are oftentimes seen as the first steps towards claims of enhanced autonomy or even secession. Reaching this level of paradiplomatic activity thus requires a high degree of sophistication and funding that is oftentimes beyond the reach of most subnational actors.

Indigenous Peoples as Diplomatic Actors

Thus far, paradiplomacy has primarily been discussed in relation to subnational actors, with limited attention being given to non-state or non-governmental diplomatic activities. One area where this limitation is particularly notable is the role of Indigenous Peoples’ Organisations (Álvarez & Ovando, Reference Álvarez and Ovando2022; Chater, Reference Chater2021; Meissner & Warner, Reference Meissner and Warner2021; Tennberg, Reference Tennberg2009). IPOs represent a departure from the aforementioned units of study on (para)diplomatic activity as they serve as representative agents of peoples that have been denied the right to statehood through conquest and assimilation (Lindroth & Sinevaara-Niskanen, Reference Lindroth and Sinevaara-Niskanen2022; Tennberg, Reference Tennberg2009).

Some scholars argue that these organisations, and the peoples they represent, are but an extension of a long history of engaging with states on a peer-to-peer level (Beier, Reference Beier2009, Reference Beier2016; Corntassel, Reference Corntassel2021; Wilmer, Reference Wilmer1993). These sorts of activities are typically covered by a small but growing framework of Indigenous diplomacy, which attempts to reckon with the erasure of Indigenous voices from foreign policy discussions and how such peoples have continued to operate on an International level despite such removal (Lightfoot, Reference Lightfoot2016). This has taken many forms, as the diplomatic traditions of Indigenous peoples differ widely.

It is at this point that the usefulness of paradiplomacy for analysing Indigenous diplomatic actors becomes most apparent. As a theory, it represents a pathway towards highlighting the sort of diplomacy that such diffuse and diverse actors undertake while also taking into consideration the material conditions that present barriers towards achieving true diplomacy recognition. Despite this, paradiplomacy scholars have only recently considered these groups and even then only in a limited manner. The little scientific work that has been done thus far has focused on international fora such as the Arctic Council or the United Nations (UN) – arenas of diplomatic activity in which IPOs have been able to confront governments directly (Carpenter & Tsykarev, Reference Carpenter and Tsykarev2021; Chater, Reference Chater2019; Davis, Reference Davis2008; Gamble & Shadian, Reference Gamble and Shadian2017). Andrew Chater, one of the few scholars to tackle this topic, explains why it may have been difficult to grasp Indigenous groups as paradiplomatic actors, particularly in the Arctic.

Are these [Indigenous] groups paradiplomatic actors? On one hand, they are. Paradiplomacy refers to a “sub-state, subnational or regional actor” participating in international diplomatic action. Arctic Indigenous Peoples’ Organisations fit this definition because they exist under national governments and engage in diplomatic activities…[However] Indigenous peoples play an important role in the response to regional issues but lack the de jure sovereignty necessary for recognition as a government (Chater, Reference Chater2021, p. 140).

However, this lack of de jure sovereignty may not be the barrier that Chater assumes. Rather, as this case will show, it is quite possible for Indigenous people to represent themselves on the world stage through an IPO despite not being recognised as a government, as it has been the case for some time already. Indigenous diplomacy scholars argue that highlighting these aspects makes Indigenous actors more visible on the world stage. To this end, paradiplomacy provides an analytical framework in which their diplomatic actions can be understood as unique, for the barriers for such activity are often disproportionately high, but also typical, for the steps taken resemble that of any other politically minded organisation.

Background: An Overview of Sámi Political History

The Sámi are a people considered native to the northernmost regions of modern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of north-western Russia (John B. Henriksen, Reference Henriksen2008, p. 27). Traditionally, Sámi have been – and in some cases continue to be – pastoralists who made their living in the way that best suited the landscape. As a result, hunting, fishing, and early forms of reindeer herding were widespread (Hansen & Olsen, Reference Hansen and Olsen2014). While interactions between Sámi and Southerners were not infrequent throughout their history, the relatively high distances between peoples constituted a barrier towards a greater connection (Tacitus & Rives, Reference Tacitus and Rives1999). This also applied to borders, as the conditions in the northern region meant that sovereignty over the area was often more hypothetical than literal. However, a gradual colonisation process that had begun in the Middle Ages eventually culminated in the states claiming dominion over the Sámi territories, often through tax policies that resulted in payments to one, two, or even three crowns (Hansen & Olsen, Reference Hansen and Olsen2014, p. 229). This situation continued up until the 18th century when the process of dividing up the common territories by establishing fixed state borders began.

In 1751, the Treaty of Strömstad was signed between Denmark-controlled Norway and Sweden (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen2008; Lantto, Reference Lantto2010, p. 545), which marked the resolution of centuries-long border disputes over the northern edge of both states’ assumed domains. Though a useful treaty to the state powers involved, dividing the previously common region also separated the populations that lived there, mostly predominantly the Sámi, which posed a threat to their traditional resource use. To avoid this, the Lapp Codicil was born. This was an addendum to the border treaty that confirmed traditional Sámi rights to use lands across these newly agreed-upon borders and was intended to protect their ancestral way of life (Lantto, Reference Lantto2010, p. 545; Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2006). As such, the Lapp Codicil has remained a foundational document on which the rights of the Sami have been based and asserted ever since.

Following the Napoleonic wars, borders were defined even more clearly and, in turn, solidified (Lantto, Reference Lantto2010). Throughout a period of 50 years, both these boundaries and the attitudes that established them would harden, as nationalist sentiment and suspicion became more dominant. Following a series of border agreements, and subsequent border closures, the Sami would have become a territorially divided people, with the rights granted by the Lapp Codicil forgotten or ignored. It was then that the formal process of state assimilation began. In Sweden, this was done through the “Lapp-Shall-Remain-Lapp” policy, which encouraged cultural survival primarily for reindeer herders, while others were forcibly assimilated into Swedish society (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto and Mörkenstam2008, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015). Norway pursued a policy of “Norwegianisation,” which aimed to assimilate the Sámi through mandatory schooling, land removal, and strict language laws (Aarsæther et al., Reference Aarsæther, Bendixen and Føleide2023; Minde, Reference Minde2003a; Ravna, Reference Ravna2011). These efforts to assimilate the Sámi persisted from the mid-1850s well into the 20th century (Sannhets- og forsoningkommisjonen, 2023).

In response to both these assimilation efforts and the tightening of reindeer herding laws, Sámi activists and leaders began to emerge and resist (Lantto, Reference Lantto2000; Össbo, Reference Össbo2020). At the centre of this early resistance movement were newly formed reindeer herding and cultural associations, which served as new units of social connectivity and representation (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015). The first of these was founded in 1904 in Sweden, and though short-lived, many more similar organisations would emerge across the north (Johansen, Reference Johansen2015; Svendsen, Reference Svendsen2021). Although they initially only had a limited following and reach, these associations brought together activists who would become key figures for the Sámi cause, such as Elsa Laula Renberg, Daniel Mortenson, and Torkel Tomasson (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015; Minde, Reference Minde2005; Svendsen, Reference Svendsen2021). Around the same time, the first newspapers and journals to be written in the Sámi languages were published. These early associations and stirrings of media culture resulted in the emergence – and eventually, the formalisation – of a joint political identity that transcended borders (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto and Mörkenstam2008). Building upon this sense of a common cause, a series of cross-border meetings were organised. The first was held in Tråånte/Trondheim in 1917 (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015). Such was the success that several other meetings were held across the region, most notably in Staare/Östersund. However, this first wave of cross-border organising would prove short-lived as an increasingly oppressive political climate and a lack of funding meant that further attempts at mobilisation were rendered impossible (Larsen, Reference Larsen2012). It would not be until after the Second World War that a second attempt would become possible.

Methods and Methodology

Methodologically, this case study takes the form of a historical narrative examining the first 50 years of Saami Council’s history from 1956 to 2000 (Lange, Reference Lange2013; Yin, Reference Yin2009). This period was chosen for two reasons. First, for practical purposes. One of the primary documents on the Saami Council is a chronology, titled Sámiráđđi 50 Jagi (Saami Council 50 Years), which was published by the organisation in 2004. It covers the chosen investigation period explicitly and has not been explored before in English. Second, as will be discussed, this period was a time of great changes for the Council and the Sámi people themselves. If one wants to understand how the Saami Council evolved into the international actor it is today, the first 50 years of its existence are the best place to start. To explore the paradiplomatic aspects of the Saami Council, pattern matching will be applied (Lange, Reference Lange2013, pp. 43–44). In brief, pattern matching is a process that is used to compare the steps taken by the subject with the suppositions of a theory to determine if the theory provides an adequate explanation for the case itself.

The method of data collection utilised in this paper is a form of data triangulation using textual sources (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Blythe and Neville2014; Patton, Reference Patton1999). The aim was to synthesise primary, secondary, and academic tertiary data materials to build a historical narrative. The foundation of this synthesis is the aforementioned Sámiráđđi 50 Jagi. Using this chronology as a guidepost, the narrative was further supplemented by a series of declarations made by the Saami Council during the periodic political conferences it hosted. These events, called simply Saami Conferences, constitute significant assets to this study and will be discussed further on. These primary documents were then scaffolded by a variety of secondary sources, including contemporary reports and later academic papers, to fill out the narrative and corroborate the data provided by Sámiráđđi 50 Jagi. Particularly useful were two academic studies that were published by the Bibliothèque Arctique et Antarctique in the 1960s, following the Saami Council’s earliest conferences: Johnathan Crossen’s ongoing work on the WCIP and John Henriksen’s overview of Sámi civil society in the late 1990s (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, Reference Crossen2017; Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1999; Hill, Reference Hill1960; Nickul & Hill, Reference Nickul and Hill1969). Including the aforementioned conference documents, around 20 major secondary sources were used.

The case study of the Saami Council is presented in three sections. The first part covers its foundation in 1956, its early structure, and the first 20 years of its existence. The second part examines the 1970s when the Saami Council began its international activities and its collaboration with the WCIP in particular. The third part focuses on the final 20 years of the 20th century, during which the Saami Council established itself as a significant international actor with representation at the UN, while gradually distancing itself from the World Council. Once the historical narrative is complete, this study will examine the development of the Saami Council with the sliding scale of paradiplomatic activity introduced earlier in this paper.

Case: The Saami Council

Saami Conferences and Nordic Saami Council Foundation (1954–1970)

The First Saami Conference and the birth of the Pan-Sámi Movement

Following the false spring of the first wave of cross-border mobilisation, Sámi interests turned inwards to preserve what they could and hope for better years. These were finally to come in the 1950s when a second wave of organisation began – albeit in fits and starts. It was in this environment that a meeting in Stockholm in 1952 would spark the first discussions towards building bonds across borders, even though the focus of the meeting was actually and officially on the topic of duodji – traditional handicrafts that remain a key part of Sámi cultural identity. In attendance were organisations as well as activists and thinkers that were, or were to become, prominent figures within Sámi political circles. Among them were Israel Ruong from Sweden, Asbjörn Nesheim from Norway, and Karl Nickul from Finland (Hill, Reference Hill1960, p. 19; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 2). As is common at such meetings, the conversation branched into further topics, particularly the conditions faced by their people. Recognising the need for renewed cooperation, it became clear that the time was right to bring Sámi from the different northern countries, and the respective organisations that represented them, together in a more formalised way. To this end, their goals turned to planning a gathering reminiscent of the conferences held in the 1910s (Hill, Reference Hill1960, p. 19). As each person in attendance was closely associated with nascent Sámi cultural and labour organisations that had begun to flourish in this period, including Sámi Ätnam from Sweden and Sámi Saer’vi from Norway, they were well placed to make this happen (Nickul et al., Reference Nickul, Asbjørn and Ruong1953; Saami Council, 2023).

As such, after a short year of planning, the first revived Saami Conference took place in Jåhkåmåhke/Jokkmokk, Sweden in 1953. The meeting was well attended, with around 200 participants and representatives from four Sámi-focused associations gathered from across Sápmi. The theme was “Activating the Sámi,” specifically by creating a greater group consciousness among the Sámi (Hill, Reference Hill1960; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 1; Saami Council, 2023). The theme was aptly chosen, as the goal of this first conference was to reconnect a people that had been split apart by borders, as well as to discuss and debate the common issues that they faced. A glance at the conference schedule reveals the main topics of interest to the Sámi civil society of the time, which revolved around Sámi-language schooling, hunting and fishing rights, and reindeer herding (Nickul et al., Reference Nickul, Asbjørn and Ruong1953, pp. 17–22). These topics would become perennial at the Saami Conferences, reflecting shared desires and struggles that continue to be part of political conversations in Sápmi to this day. It was also here that an emblem consisting of three concentric rings was introduced to symbolise both the conference itself and the broader hopes for Sámi unity (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 2). It eventually became the symbol of the Nordic Saami Council, yet it also could be considered the first national symbol of the Sámi, predating all others (Hill, Reference Hill1960, p. 95). Following this symbolic milestone and the success of the event, preparations began for a second conference and the formation of a more permanent organisation committee (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004 ). It would also mark the beginning of what would later be referred to as the Pan-Sámi movement or Pan-Sámi process, in which the struggle for greater rights recognition to land and language would transcend borders through the continual connection brought about first by this first conference and then through other means as time went on (Minde, Reference Minde1996, p. 237).

The Foundation and Structuring of the Nordic Saami Council

The second Saami Conference was held in Kárášjohka/Karasjok, Norway, in 1956. The agenda for the event was similar to the previous conference, but the bulk of space and planning was dedicated to the formation of an official political organisation (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1956, pp. 13–18; Hill, Reference Hill1960, p. 97; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 3): Given the title of the Nordic Saami Council, the new body was formed primarily to serve as the official organiser of the conference itself – a role it holds to this day – though it was set up to take on further duties as – and if – required (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 3). It was also during this second conference that the system of Saami Conferences was officially codified (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004; Saami Council, 2023). They were supposed to take place once every three years – though in practice, this would be between three and five. Members of the community, through their respective organisations, would come together to discuss issues of importance that pertained to all Sámi life and connect across the very borders that had previously disconnected them.

From the start, the civil organisations that took part in the Saami Conferences were placed at the centre of the Nordic Saami Council’s overall structure (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1956; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004). In 1956, there were 12 organisations in attendance, and these became its founding members. Representatives from these organisations were elected to the Council, serving as speakers for their member associations and the Sámi within their respective host countries (Nickul et al., Reference Nickul, Asbjørn and Ruong1953, pp. 15–16). At the time, the number of representatives sent to the Council was proportional to the size of the Sámi population within each state. As such, at the 1956 Conference, three representatives were elected from Finland, five from Norway, and four from Sweden (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1956, pp. 15, 17–18). Moving forward, the representatives of these organisations would be voted to the Council at every new meeting of the Saami Conference and would serve until the next one. This created a natural rotation period analogous to a typical election cycle, while also remaining embedded into the established conference structure. If a new member organisation wished to join, the Council members would vote on it during the conference (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004 ). This system adapted as time went on and new organisations petitioned to join, while previous ones merged or disbanded. Nevertheless, the Council would never grow to be very large. It was understood that it was, first and foremost, the keeper of the Saami Conference. As time went on, however, this role would expand.

The Council’s First 20 Years

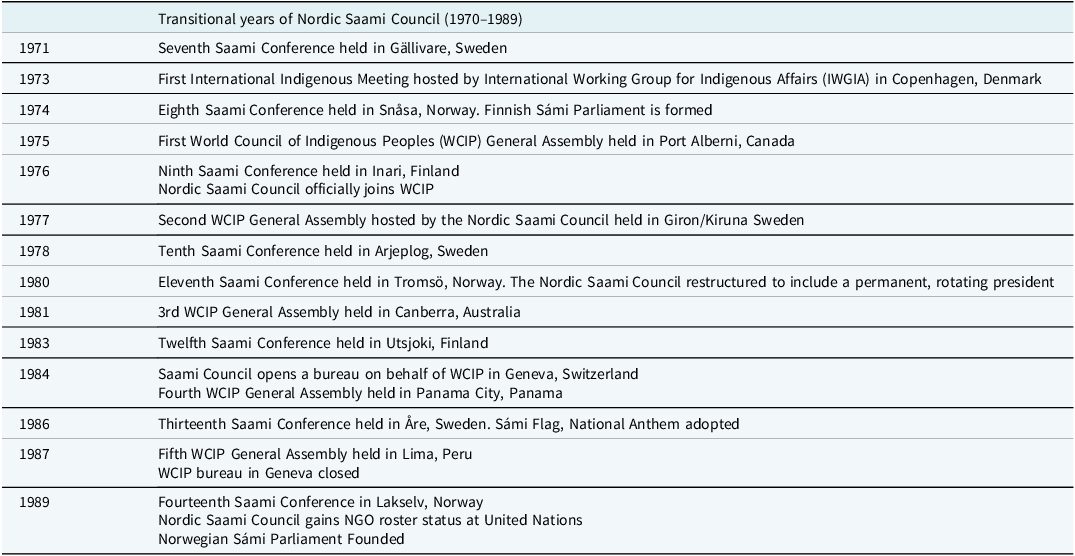

The first 15 years of the Nordic Saami Council’s existence could be described as active but quiet. This is most clearly depicted at a glance at Table 1. Looking through statements and documents from this period, the topics discussed during the first conference had become established as key areas of debate (Hill, Reference Hill1960; Nickul & Hill, Reference Nickul and Hill1969). These included language rights for children, reindeer herding regulation and management, and the marketing and protection of duodji (Hill, Reference Hill1960; Nickul & Hill, Reference Nickul and Hill1969; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004 ). Politics and political themes were often at the centre of the conversation, particularly when it came to language and cultural rights. However, it has to be pointed out that there were initially hardly any efforts to address topics beyond the Nordic region. The emphasis was clearly a regional one, focusing on the more local struggles Sámi experienced in their day-to-day lives. That each conference rotated between the Norwegian, Swedish, and Finnish parts of Sápmi served to highlight these shared concerns and the commonalities between people separated across national borders.

Table 1. Timeline of Nordic Saami Council early years 1952–1969 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004)

An interesting aspect that came to light when examining the documents of the time is the repeated mention of the active engagement of non-Sámi allies – both within the member organisations and as outside actors (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004 ). These non-Sami actors appear to have mostly been academics, but the general makeup is not made explicit in the texts. Interestingly, their involvement did not seem to obstruct the goals of the early movement, quite the contrary. Rantala and others have noted that even during this early period, demands for the protection of Sámi rights and greater recognition of their special connection to the land were some of the chief claims (Henriksen, Reference Henriksen1956; Hill, Reference Hill1960; Nickul et al., Reference Nickul, Asbjørn and Ruong1953; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004). Through these non-Sámi allies, early connections were made with the Nordic Council, which was founded in 1952 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 3). As historian Henry Minde notes about this period, “Thanks to these ‘friends of the Sámi’, the Nordic Saami Council, under the auspices of the Nordic Council, was able to arrange conferences on Sámi rights; to publish extensive reports of conferences and meetings; to set up a Nordic joint body on the issue of reindeer herding; and get Sámi matters onto the agenda in the interparliamentary Nordic assembly” (Minde, Reference Minde1996, p. 237).

By the end of the decade, the imbalance would eventually end and the Sámi would come to the fore of both their nascent movement and the conferences that supported it. As noted by Rantala, the 1968 Conference in Heahttá/Hetta, Finland, would be the last to host a majority of non-Sámi participants (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 4). What effect this had on proceedings is difficult to judge as other events would arise to change the direction of the Nordic Saami Council and bring it into greater alignment with the wider Indigenous world (Table 1).

First International Meetings and the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (1970–1980)

The 1970s would be something of a growth period for both the Sámi political consciousness awareness and the Nordic Saami Council itself. The post-colonial divestment and civil rights movements of the time had borne fruit across the world, with many marginalised groups banding together to claim the rights that had been denied to them by state policy (Crossen, Reference Crossen2017). Indigenous peoples also joined these endeavours and were often at the forefront of renewing the struggle against beneficiaries of settler colonialism. The term pan-Indigenous movement – sometimes referred to as the Fourth World at the time – would come to be used to encompass this broadening group of diverse peoples that were united by a shared history and reality of systemic marginalisation and oppression (Niezen, Reference Niezen2000). The Sámi would be brought into this movement in 1973 when the International Working Group of Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), a Copenhagen-based human rights group, put George Manuel, a Canadian First Nations chief, in touch with Sámi herders in northern Sweden (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014).

This meeting came at a pivotal time for Sámi rights and recognition, as they began to voice demands which were beyond the primarily cultural scope of an ethnic minority in their respective countries. In Norway, activists began to show the first rumblings of resistance to the Alta hydroelectric dam project (Andersen & Midttun, Reference Andersen and Midttun1985; Laframboise, Reference Laframboise2024; Minde, Reference Minde, Jentoft, Minde and Nilsen2003b). In Sweden, a highly critical case considering Sámi rights known as Skattefjällsmålet (the Taxed Mountain Case) worked its way through the courts (Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015; Össbo & Lantto, Reference Össbo and Lantto2011).

Amid these events, the meeting between a First Nations chief and Sámi herders represented the moment in which the cause of Sámi rights and the wider Indigenous world were linked. This was further strengthened during the same year, as the first IWGIA Arctic Indigenous Peoples’ Conference was held. This conference was the first time that Indigenous people of the Arctic were brought together in a formalised way (Magga, Reference Magga, Dahl, Holmberg, Olsvig and Wessendorf2024; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 6). As Minde notes, “The atmosphere and discussion at this conference was intense, arousing great expectations for the worldwide organisation of Indigenous peoples that were in the planning stage” (Minde, Reference Minde1996, p. 238). This meeting would go on to spark greater collaborations in the years to come, but the most immediate was the beginning of plans for a wider conference to bring together not just the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic but across the world.

To this end, two years later, Sámi representatives would travel to Georgetown, Guyana, for the first preparatory meeting for what would eventually become the WCIP, one of the first formal organisations to represent itself as a joint Indigenous movement on the world stage (Crossen, Reference Crossen2017, p. 543). Arrayed at this meeting were representatives from across the world, including the First Nations of Canada, the Māori of Aotearoa/New Zealand, and others (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, pp. 172–173). By the end of the Guianan meeting, a definition of indigeneity was established that focused on minority status and political history rather than race or skin colour. For the Sámi, this meant acceptance as part of a broader political movement. In 1976, at the ninth Saami Conference in Aanaar/Inari, Finland, the Nordic Saami Council became a member of the WCIP (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 6). This event and date were significant, as it had been 30 years since the organisation’s founding, and in many ways served as a transitionary year for both the Sámi and the Council. WCIP chair George Manuel had been invited to attend, and with him came the proposal that the Nordic Saami Council might organise the second General Meeting of the WCIP, set to be held in 1977 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 6).

The Transition from Regional to International

The General Meeting of the WCIP was hosted in Giron/Kiruna, Sweden. It was the largest event hosted by the Nordic Saami Council until that point – over 1000 participants that represented 18 countries were in attendance – and, by all indications, a significant success (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 6). As a result, the 1978 Saami Conference in Árjepluovve/Arjeplog, Sweden, saw an energised Nordic Saami Council. Influenced by its newfound connections to the wider Indigenous world, members of the Saami Council began to call for the establishment of a formal political agenda for the Sámi people (Nordiska samerådet, 1978, pp. 6–7, 24; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 7). This was proposed jointly with the call for the creation of national symbols to define the Sámi people. What these symbols would be was decided later, but the signal alone constituted a more formal attempt at nation-building and unity than had ever been the case before. These steps were necessary as the Sámi began to see themselves not only as a political people but also political actors in their own right – capable of representing themselves and proud of their history and traditions.

Overall, the 1970s marked a period of consolidation and internationalisation that fundamentally shifted the role and position of the Saami Council. This shift can be seen when plotted out in Table 2. It began the decade as a mere facilitator of the Saami Conference, which was held every three to four years. Apart from that, it only had a few other minor duties. However, by the end of the decade, it had evolved into a formalised international non-governmental organisation (NGO) that was taking part in transnational conferences by itself and was also getting increasingly involved in the broader global struggle for Indigenous rights. To quote Leif Halonen, a former Nordic Saami Council President, “We didn’t think of the Saami Council as an international body. It was a Sámi body… But in 1977 at a meeting in Geneva, the Saami Council discovered it was an international body” (Grid-Arendel, 2017). In the context of the greater decolonial movement, this represented a clear shift in the organisation’s trajectory (Table 2).

Table 2. Timeline of Nordic Saami Council transition period 1970–1989 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004)

International Institutions and the Maturation of the Nordic Saami Council (1980–2000)

As the 1980s began, the Nordic Saami Council itself underwent profound institutional changes, as semi-committees were set up and the office of a permanent president was established (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, pp. 7–8). A set term limit of one year was determined, as was a rotation between national groups, with the overall goal to ensure the even and united representation of all Sámi. All this resulted in the formalisation of an organisation that would be able to represent the Sámi internationally. As an organisation newly introduced to the world stage, it kept close ties to the WCIP, through which it was able to position itself at the centre of the pan-Indigenous movement. The last two decades of the 20th century would be a time of both growing power for the Nordic Saami Council and also changing relationships. One key example of this was the growing involvement in the UN.

Since the first reports on the condition of Indigenous peoples in the 1960s, the UN has become a vector for greater decolonising efforts (Davis, Reference Davis2008; Minde, Reference Minde2008). In 1971, the Cobo Report outlined several structural and discriminatory barriers to the participation of Indigenous leaders at the UN (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, p. 55). To change this, the UN began to view Indigenous peoples not as subjects but as “autonomous and self-sustaining societies that faced discrimination, marginalisation and the assimilation of their cultures because of larger, dominant settler populations” (Hossain, Reference Hossain2013, p. 322). To open up to their participation, the Working Group on Indigenous Peoples was established in 1982 under the aegis of the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, an important subsidiary branch of the UN Commission of Human Rights (Hossain, Reference Hossain2013, p. 320; Magga, Reference Magga, Dahl, Holmberg, Olsvig and Wessendorf2024). This working group would become the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and as the name would suggest, it served as a key monitor and promoter of the rights of Indigenous peoples. This granted the WCIP – and, by extension, the Nordic Saami Council –direct access to the broader UN. This, in turn, would lay the groundwork for the foundation of the UNPFII in 2000 and, eventually, the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

Initially, the Nordic Saami Council came to the UN as part of the WCIP rather than as its independent voice. The dream of the World Council and its chair was to gain NGO status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014). This had been achieved previously by the National Indian Brotherhood, a Canadian First Nations organisation, in 1974 – meaning that such a path was viable, though it would take a long time. In the hope of giving this goal more legitimacy, an office was established in Geneva, near the UN premises, in 1984 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, p. 8). While it was run on behalf of WCIP, it was funded and operated by the Nordic Saami Council. While this mission only a short time – until 1986 – it was the first modern example of a diplomatic-like office set up on behalf of an Indigenous Peoples’ Organisation.

The End of the WCIP and the Foundation of the Arctic Council

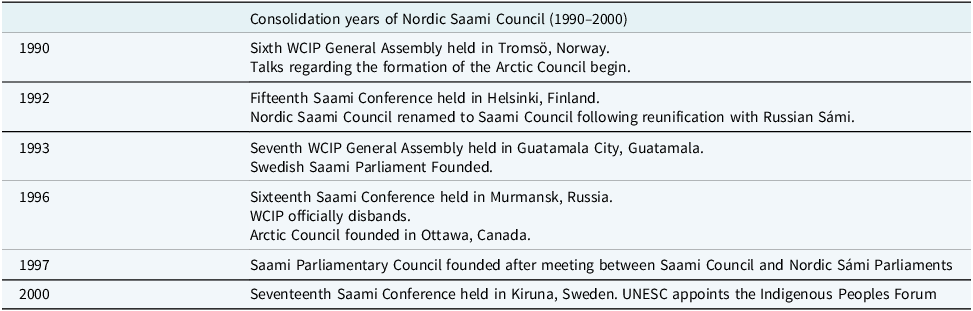

Unfortunately, the office in Geneva would mark the peak of the association between the Nordic Saami Council and the WCIP, as their connections began to fray towards the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, pp. 280–283). This decline can be charted through the timeline presented in Table 3 and was for several reasons.

Table 3. Timeline of Saami Council consolidation period 1990–2000 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004)

The first reason was that 15 years after its elevation to the international stage, the Nordic Saami Council found itself more independent than it had initially expected. One example of this was the growing closeness between the Sámi-led organisation and the Inuit Circumpolar Council, a similarly Arctic-focused body. As Jonathan Crossen notes, “Both the Sámi and Greenland’s Inuit had already sought transnational regional connections with the Arctic Circumpolar Conference and the Nordic Sámi Council; for them, it was only an additional step to form an even broader international organisation” (Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, p. 238). In 1986, the Nordic Saami Council, along with the Inuit Circumpolar Council, discussed the creation of an Arctic environmental organisation, which would be, in turn, connected to a nation-state lead Arctic strategy (Murray, Reference Murray2014). Termed the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy, this would bring several IPOs in direct connection with the national governments of Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the then Soviet Union (later the Russian Federation), and the United States (Bloom, Reference Bloom1999, pp. 712–713). This agreement, which tied Indigenous peoples, governments, and scientists together, would result in the formation of the Arctic Council in 1996.

The Nordic Saami Council’s inclusion in the Arctic Council is emblematic of a greater shift in fortunes that occurred during the 1990s. This leads to the second reason for the WCIP’s growing irrelevance in the Nordics, where the conditions faced by the Sámi changed profoundly around this time. Most notably, the Alta conflict in Norway and Skattefjell case in Sweden ushered in a new era in Sámi-state relations in both countries (Aanesland, Reference Aanesland2021; Lantto & Mörkenstam, Reference Lantto, Mörkenstam, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie and Ann2015; Minde, Reference Minde1996). In 1989, Norway established a Sámi Parliament – completing a process that had been initiated after the end of the Alta conflict ten years earlier (Minde, Reference Minde, Jentoft, Minde and Nilsen2003b; Selle & Strømsnes, Reference Selle and Strømsnes2023). Sweden would follow suit in 1995, though its Sámi Parliament was granted far fewer responsibilities compared to the bevvy given to its Norwegian counterpart (Kuokkanen, Reference Kuokkanen and Beiar2009). This meant that each territory represented within the Nordic Saami Council now had an official Sámi Parliament. This included Finland, which had already created such a body in 1973, but which would undergo significant reorganisation to bring it closer in scope with its peers in 1995. This gave Sámi people an unprecedented degree of direct government power.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly on a symbolic level, the Nordic Saami Council and the Sámi people at large would be reunited with their cousins in Russia with the fall of the Soviet system in 1991 (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, pp. 10–11). In recognition of this reunification, the Nordic Saami Council was renamed to simply the Saami Council at the 1992 Saami Conference in Helsinki (Samerådet, 1992). On the more material level, funding and aid were swiftly put into place to help their long-separated kin – thus rebuilding bonds that had been severed since the end of the Russian Civil War in 1922.

It is perhaps because of these positive developments and the growing strength of the Saami Council as an NGO that led to it being among the most surprised when the WCIP eventually collapsed in 1996 Crossen, Reference Crossen2014, pp. 280–283). The Saami Council had been the most well-funded of the organisations involved, so when it began to lose interest due to political disagreements, the sense of international solidarity faltered. Though the WCIP was missed as a project, the Saami Council had outgrown it as a political platform. This was perhaps best illustrated by its acceptance as an NGO observer to the UN in 1993 (Kent, Reference Kent2014, p. 76; Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, pp. 9–10). Although the Saami Council’s focus had shifted back to its home region, it did not become any less international. Its presence on the world stage remains deeply tied to that of other Indigenous peoples, but now as its own and independent actor. However, as its cooperation with the Inuit Circumpolar Council has shown, it still connects with allies whose specific issues also matter to it (Table 3).

Analysis: A Model of Indigenous (Para)diplomacy

As the new millennium began, the Saami Council was firmly placed as not just an Indigenous Peoples’ Organisation, but something more. As the history traced by Sámiráđđi 50 Jagi comes to a close, it is prudent to consider what kind of organisation it has evolved into and in what manner. At the time of the organisation’s inception, the (then) Nordic Saami Council was at its least state-like in both scope and reach: Its primary purpose was to facilitate cross-border dialogue between Sámi organisations by organising the Saami Conferences (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004, pp. 1–3). This was strictly on a regional basis, with organisations that represented Sámi civil society standing in as the voice for their respective people. These representatives are key to understanding the development here. While they were not states, they spoke on behalf of a people, even if they did not have – as Andrew Chater noted – de jure sovereignty (Chater, Reference Chater2021, p. 140). In this early period, contacts outside the Nordic region were marginal at best. While there were some external relations, most notably with the Nordic Council, there was little desire – or even capacity – to expand outward. In paradiplomatic terms, this places the Nordic Saami Council at the level of regional micro-diplomacy through its connections across state borders. However, its lack of capacity and reach put it on tenuous ground.

The 1970s represented a transitionary point for the Nordic Saami Council, not only regarding its goals but also in terms of its paradiplomatic activities, as its reach and connections expanded greatly. The Georgetown conference in 1974 and its hosting of the WCIP General Assembly in Giron/Kiruna in 1977 were two pivotal points. In short order, the organisation went from primarily organising conferences to representing the Sámi people in an international capacity through its connections with the WCIP, which coincided with a general increase in international interest in Indigenous causes. As such, the Council shifted its focus from regional to international relations to further its goals of greater recognition of Sámi rights through the solidarity found with other Indigenous groups (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004). To strengthen their chances of meeting these goals even further, the Council adjusted its structure to become a more representative body. The result of these reforms was the formation of a formal presidential body and task groups, which were focused on both regional and international issues, in 1980, which strengthened the Council’s organisational capabilities. The greater connection with an international community, beyond its home region, put the Nordic Saami Council of the time well in line with the second level of paradiplomatic activity, regional micro-diplomacy (Duchacek, Reference Duchacek1986, pp. 243–246). This is reflected in the participation in international conferences and meetings with Indigenous organisations from all over the world – a clear expansion of activities compared to the past.

The events of the latter two decades of the century would solidify this position, as the connections made during the 1970s would become entrenched. The Council’s forays to the UN and, later on, the Arctic Council point to a growing confidence in its own abilities – outside of its commitment to the WCIP (Rantala, Reference Rantala2004). This coincided with successes at the local and regional level, as events in Norway and Sweden resulted in a strengthening of rights that had been hard fought and built, in part, on the back of solidarity across the Indigenous Fourth World. With that being said, and even though the Nordic Saami Council became more formalised during this period, establishing permanent links between organisations and any sort of permanent office was – and, to a certain degree, remains – beyond their capacity.

As has been shown, the Saami Council does appear to fit into the paradiplomatic model reasonably well, but it is possible to take this a step further. At its core, paradiplomacy attempts to understand how non-state actors operate on the world stage. For practical reasons, this has often focused on sub-state units, as these bodies are best equipped at both a material and legal level to undertake diplomatic actions. They are, in essence, the most state-like non-states and, as such, are most likely to act like them. In contrast, IPOs such as the Saami Council represent people who have been denied these state-like structures – and all their benefits – despite constituting a people on territory that has since been taken from them (Broderstad, Reference Broderstad2002). Despite structural limitations, a shared sense of “Sámi-ness” pervades the history presented in this case study, representing a sense of Indigenous nationalism that appears little different than the same nation-building projects that other peoples undertook during the earlier periods of state formation. The moment the Saami Council gained access to the international stage, it also began a nation-building project of its own, though its first steps had been taken in 1956. Since its development coincided with an emerging sense of a Sámi national identity, the turn of the Saami Council – from its humble beginnings to its ambitious claim of representing and connecting the Sámi across borders – was hardly a surprise.

It is for this reason that the Saami Council has evolved into a paradiplomatic body. It may not be quite as strong as a typical sub-state actor in that regard, but it certainly has been undertaking actions that resemble diplomacy – and it continues to do so. This can be considered remarkable, but it should also be recognised for it what is: an Indigenous effort to make themselves heard in an arena that has been denied to them. That the Saami Council has become such a bedrock organisation for Indigenous representation demonstrates that de jure sovereignty is not a barrier to become a representative actor on the world stage. Rather, it is something that is imposed and, as such, can be overcome through other means. Further work is needed to make these efforts more visible, but for now, the Saami Council stands as an example of Indigenous-led diplomatic work that operates despite the constraints placed on a colonised people.

Conclusion: A Sámi Body, but also an International Body

At its founding, the Saami Council served as a non-governmental organisation focused on connecting Sápmi – the homeland of a people that had been split apart by the borders of nation-states. This was done through the Saami Conferences and a structure that prioritised the equal representation of the civil society organisations that constituted its members. As the organisation became more established, its responsibilities were expanded to not just connect the Sámi but to represent them as well. The fact that it drew member from across Sápmi meant that it was ideally placed to speak on behalf of their people on the world stage. Thus, advocacy – both on the regional and the international level – became more firmly entrenched as a goal of the organisation.

By the turn of the century, the Saami Council had become more than just a regional gathering of politically interested Sámi, but a key actor in representing its people on the world stage. This came as a result of a greater sense of connection with the wider pan-Indigenous movement, but also a strengthening of the position of the Sámi as a political actor within their region. As have been discussed, the actions they took to achieve this fell neatly in line with the evolution of other non-state actors in international politics. This case study shows that the Saami Council is involved in such a role, based on the changing needs of its community.

This article represents a small, but significant expansion of what it means to be active on the world stage. The Saami Council, and organisations like it, demonstrate that diplomatic action can take a variety of forms – transcending the traditional view of diplomacy as the sole domain of states and state-like actors. Furthermore, it highlights the work of people(s) that have often been erased from the typical discussion of what it means to be a diplomatic actor, which paradiplomacy helps to clarify within the wider international system. Further research is needed to understand how such organisations have made use of the structures of the international system and how they can be better accommodated within said system. The fact remains, however, that Indigenous peoples such as the Sámi have made strides in overcoming barriers and having their voices heard, and they are not going away anytime soon.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my supervisors Anna-Lill Drugge and Elsa Reimerson for their comments and feedback throughout the process. Thank you also to Thomas Klöckner for proofreading and additional feedback before submission. This paper was presented at the European Consortium of Politica Research (ECPR) General Conference in 2023 in Prague, Czech Republic, and the Várdduo Insight and Outlook Conference in 2024 in Umeå, Sweden.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.