The identification of species at high risk of extinction is fundamental for conservation of biodiversity (Collen et al., Reference Collen, Dulvy, Gaston, Gärdenfors, Keith and Punt2016). The IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria (2012) were developed for objective and quantitative assessment of the extinction risk of species. Application of these criteria for the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and for national assessments is used to inform conservation planning, monitoring and management (Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Hilton-Taylor, Angulo, Böhm, Brooks and Butchart2010). For this, however, it is imperative that species are reassessed regularly, at least every 10 years (The Rules of Procedure for IUCN Red List Assessments 2017–2020; IUCN, 2016).

Ameerega planipaleae, a frog of the family Dendrobatidae, was originally described as Epipedobates planipaleae by Morales & Velazco (Reference Morales and Velazco1998), who indicated that the species was known only from its type locality, in the Llamaquizú River Basin, on the western slope of Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park, Oxapampa province, Pasco region, Peru. Although subsequent studies have recorded the species at its type locality (Medina-Müller & Chávez, Reference Medina-Müller and Chávez2008; Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Cosmópolis and Luján2012), the geographical coordinates provided by Morales & Velazco (Reference Morales and Velazco1998) do not match the description of the locality, placing the species outside the Llamaquizú River Basin. Relatively little is known about this frog's natural history (Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Cosmópolis and Luján2012), although it is diurnal, mostly active in the afternoon, and can be found in the leaf litter of secondary forests (Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Cosmópolis and Luján2012). Habitat loss has been a concern since the species was first described. Morales & Velazco (Reference Morales and Velazco1998) found individuals in a swampy forest fragment, isolated by loss of surrounding habitat. The area surrounding the frog's known range comprises farms and buildings (Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Cosmópolis and Luján2012). The most recent migration of people from the Andes has pushed agriculture and livestock farming onto the higher valley slopes, and cultivation of Capsicum (known locally as rocoto), in particular, has driven loss of primary forest and use of agrochemicals, and constitutes the main threat in the Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park buffer zone, especially in Chacos (Laura Contreras, Reference Laura Contreras2007), where A. planipaleae occurs.

According to the information available at the time of its 2004 assessment, A. planipaleae was assessed as Critically Endangered based on criteria B1ab(iii) (Icochea et al., Reference Icochea, Lehr, Jungfer and Lötters2004). Previously the most recent sightings of this species were in the buffer zone of Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park, where 11 individuals were observed over multiple surveys during May 2007–April 2008, with a total sampling effort of 23 person-days (von May et al., Reference von May, Catenazzi, Angulo, Brown, Carrillo and Chávez2008). Seven individuals were recorded by M. Medina-Müller and G. Chávez over 22 person-days of surveys during May 2007–January 2008 (Medina-Müller & Chávez, Reference Medina-Müller and Chávez2008), and four individuals were recorded by R. von May on 25 April 2008.

We sought to locate A. planipaleae and identify any threats to its survival, and combine our findings with all available published data to reassess the species' conservation status. Between April 2014 and July 2015 we conducted four surveys, for a total of 12 person-days, in the cloud forest of Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park and its buffer zone. Three of these surveys included the Llamaquizú River Basin (April/August 2014 and November/December 2014), covering both dry and rainy seasons.

Visual encounter surveys (Crump & Scott, Reference Crump, Scott, Heyer, Donnelly, McDiarmid, Hayek and Foster1994) were used, during daytime. Acoustic recordings of the species’ advertisement calls were played, to entice males to respond (King, Reference King2015), because A. planipaleae is difficult to locate visually and calls are a reliable way to locate males (it is the only diurnal frog species with this type of call in the area). Species presence was assessed based on both the visual encounter and auditory surveys. Coordinates of sites, recorded with a global positioning system, were used to calculate extent of occurrence (EOO) and area of occupancy (AOO) (IUCN, 2012), with GeoCAT (Bachman et al., Reference Bachman, Moat, Hill, de la Torre and Scott2011). Our local field team also identified sites aurally.

We located A. planipaleae at 10 sites (one in April 2014, three in August 2014, three in November 2014 and three in July 2015) in close proximity to each other (the furthest distance between sites was 2.03 km, with a mean distance of 0.88 km) over altitudes of 1,924–2,080 m. Four of the records were visual (three adults and one juvenile) and seven (of males) were auditory. These records gave an estimated EOO of 0.542 km2, in the Chacos sector of the National Park's buffer zone. Combining these records with one published georeferenced record (Chávez et al., Reference Chávez, Cosmópolis and Luján2012; geographical coordinates from the species description of Morales & Velazco, Reference Morales and Velazco1998, and Medina-Müller & Chávez, Reference Medina-Müller and Chávez2008, were not used as they are believed to be erroneous) increased the known EOO to 0.740 km2 and the known AOO (with a cell size of 2 km) to 8 km2.

Although A. planipaleae has not been found in trade, and all species of the genus Ameerega are included in Appendix II of CITES (CITES, 2017), there is a general demand for poison frogs for the pet trade (CITES, 2018) and therefore detailed information for the 10 sites is not included here, as primary literature has been used to locate species coveted by the pet trade (Neslen, Reference Neslen2016). This information will, however, be made available to scientists, conservationists and government officials upon request.

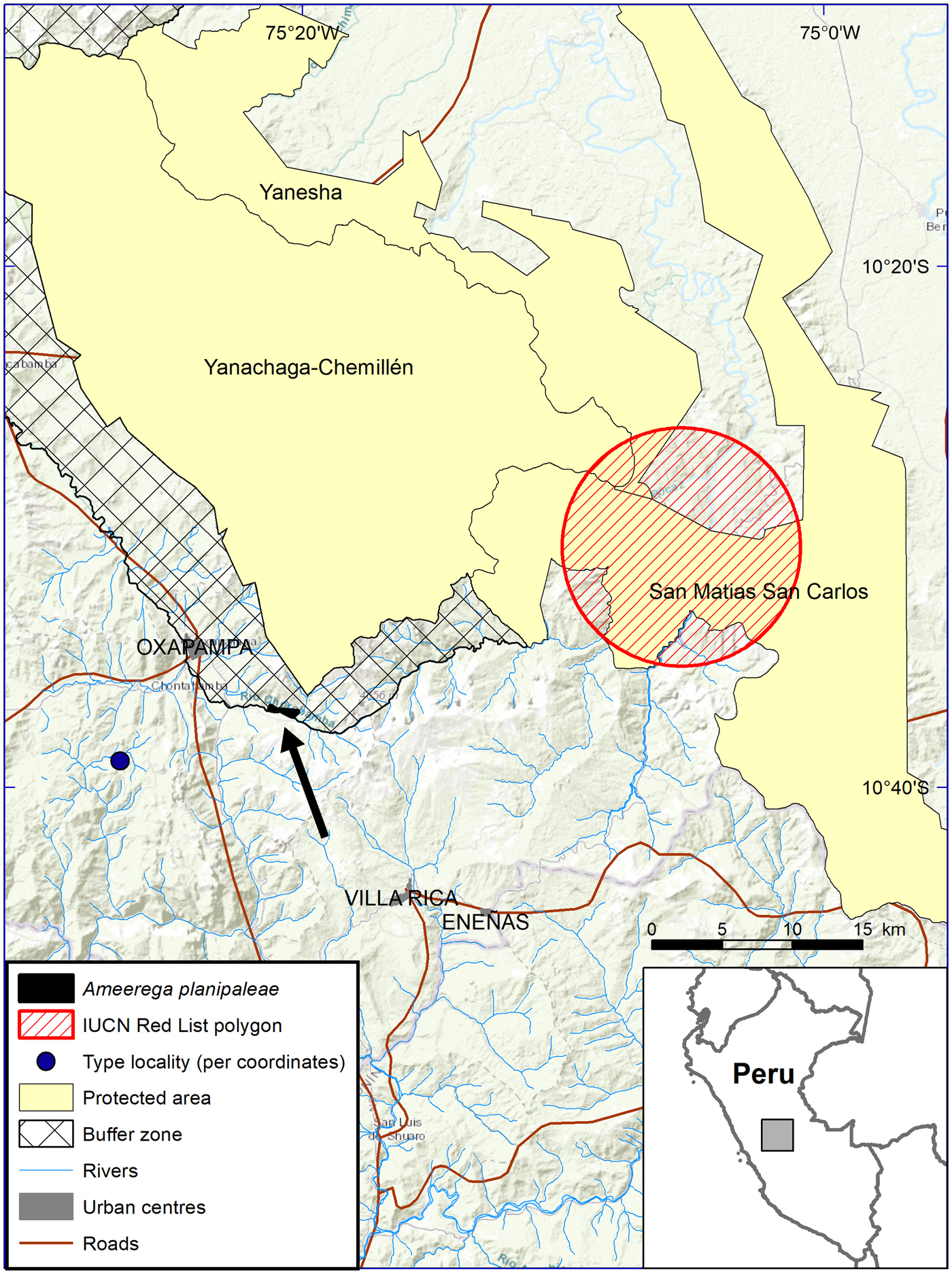

All of the known sites for this species fall outside the species’ range polygon in the IUCN Red List, which is 21–23 km east-north-east of the sites we located (Fig. 1). This is probably a result of the constraints of the mapping technology available at the time of the 2004 assessment. The IUCN Red List polygon does not include the type locality coordinates provided in the species description (Morales & Velazco, Reference Morales and Velazco1998), which lie further west of both the polygon and the documented sites for this species.

Fig. 1 The distribution of A. planipaleae in Peru and the current IUCN Red List polygon for the species, the known range and described type locality in the Chacos sector in the buffer zone of the Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park (indicated by the arrow), and the supposed location of the type locality in the species' description, which does not align with the description of the type locality in the Llamaquizú River Basin.

Ameerega planipaleae occurs in an area heavily impacted by human use, and is associated with various modified habitats: secondary forests close to plantations of pines, small streams and ditches, an inactive fish farm, and smallholdings with Capsicum and Passiflora crops that are heavily sprayed with agrochemicals such as Herbosato and Paraquat (the latter is based on information provided by a local farmer, a field team member who has knowledge of local agricultural practices, and discarded agrochemical waste that we found). Laura Contreras (Reference Laura Contreras2007) also noted the pervasiveness of Capsicum crops and associated agrochemical use in this area. The level of agrochemical use in the province is such that an agrochemical waste recycling project is being implemented (SPDA, 2018).

Ameerega planipaleae, like other species of Ameerega, has aquatic larvae, and the adults found were all in close proximity to running water, which often receives agrochemical runoff. To date, there are no records of the species within Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park, in spite of efforts by Park staff to locate the frog within the Park boundary closest to the Chacos buffer zone sector to the south of the Park.

Based on published information and our data, we make the following extinction risk assessment for A. planipaleae: (1) The species has an estimated EOO of 0.740 km2, adjusted to 8 km2 (as EOO should not exceed AOO; IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee, 2016), which is within the threshold for Critically Endangered (100 km2) under criterion B1. (2) The species has an estimated AOO of 8 km2, which is within the threshold for Critically Endangered (10 km2) under criterion B2. (3) The ubiquitous use of agrochemicals throughout much of the species' restricted range and the species’ obligatory association with water merit considering it a single threat-defined location. (4) There is ongoing decline of the terrestrial and aquatic habitats of the species as a result of heavy and continued use of agrochemicals, loss of forest to agriculture, and afforestation with commercial tree species.

We therefore propose that A. planipaleae remain categorized as Critically Endangered but based on criteria B1ab(iii) + 2ab(iii) rather than B1ab(iii). Given the species’ restricted range and the ongoing threats, conservationists need to work with the local community to reduce the use of agrochemicals and explore more benign options to control crop pests, and to investigate the use of native species as commercially viable options for timber plantations. Raising awareness of these issues is also important, as is the continued monitoring of the status of A. planipaleae.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Yanachaga–Chemillén National Park for their support, in particular park directors Genaro Yarupaitán and Salomé Antezano. Werner Loechle transported the team to field sites and Dante López and Edgar Curi provided field support in Chacos. The Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre (SERFOR, Resolución Directoral No. 0288–2014-MINAGRI-DGFFS/DGEFFS and Resolución de Dirección General No. 105-2014-SERFOR-DGGSPFFS) and the Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado (SERNANP, Resolución Jefatural No. 004-2014-SERNANP-DGANP-JEF) issued research permits for field work outside and within protected areas, respectively. This study was supported by Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund Project No. 13257928 and Global Wildlife Conservation. The Department of Herpetology at the Museo de Historia Natural de San Marcos houses specimens collected. IUCN facilitated use of geographical information system data and software. RvM thanks the National Geographic Society (Grant # 9191-12) for support. This is publication 6 of Peru's Amphibian Specialist Group.

Author contributions

All authors designed the project, conducted fieldwork and wrote the article.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research complies with the journal's Code of Conduct for authors.