1. Introduction

Accounting for the relationship between the Synoptics — not to mention, their correspondence with Johannine tradition — continues to inspire lively debate.Footnote 1 Yet amidst many conversations about the Synoptic Problem in recent years, recognition of the parallels between Q material and the Epistle of James has simultaneously developed, ushering the previously neglected ‘epistle of straw’Footnote 2 into the foreground. Although the text is framed as a Judean diaspora letter, contains only one unambiguous reference to Christ in its incipit (1.1)Footnote 3 and never cites any sayings of Jesus verbatim, there is now widespread agreement that the author of James alludes to the Jesus tradition in Q on several occasions, with sufficient knowledge of Q’s Sermon on the Mount/Plain.Footnote 4

James’ lack of verbatim agreement with Q is, of course, unsurprising. Consistent with his treatment of the Hebrew Bible, Kloppenborg has demonstrated that James rather engages in rhetorical paraphrase (aemulatio) of the Jesus tradition and offers allusions to Q sayings while considerably reworking and adapting them for his own purposes.Footnote 5 If James does constitute an independent witness to the Sayings Gospel, there indeed may be some merit to a limited deployment of the Jacobean epistle in studies of the Synoptic Problem.

This is precisely the kind of thought experiment this essay conducts. To introduce another methodological challenge within a continuum of methodological challenges with Q, the present contribution considers the reconstruction of Q through comparison with several of its Jacobean parallels, surveying the extent to which James can be fruitfully deployed. I argue that while scholars should certainly exercise caution in using James to reconstruct Q, selective comparison may offer us some new insights, particularly in adjudicating discrepancies between Matthew and Luke. Although the epistle’s utility is limited because of its lack of verbatim citation of Q, which is typical of aemulatio, I will argue that James may be particularly helpful in the contentious debate about the inclusion of the Lucan woes (Q/Luke 6.24–6) into Q and offers some force to the minority position that the woes constituted an original component of Q’s Beatitudes.

2. Aemulatio and the ‘Adaptive Reuse’ of the Jesus Tradition in James

Few today maintain James’ dependence on the Synoptics. Despite his clear knowledge of the Jesus tradition, James neither displays familiarity with Matthean or Lucan redactional features nor any explicit knowledge of Markan material, which has effectively disqualified the Synoptics as probable sources.Footnote 6 The case for Q underlying the fabric of James, on the other hand, has become quite persuasive: while Jas 2.5 does not take the form of a macarism, it has now formed a scholarly consensus that James paraphrases Q 6.20b, especially since these passages contain the sole instances of pairing βασιλεία and πτωχοί in the Jesus tradition and elsewhere.Footnote 7 There is, however, little consensus concerning how many points of contact exist between the two texts. In a survey of the nearly two hundred possible allusions identified in Jacobean scholarship, Deppe concluded that there were likely eight ‘conscious allusions’ to Synoptic tradition in James: Jas 1.5, 4.2c–3 (Matt 7.7/Luke 11.9); 2.5 (Matt 5.3/Luke 6.20b); 5.2–3a (Matt 6.19–20/Luke 12.33b); 4.9 (Luke 6.21, 25b); 5.1 (Luke 6.24); 5.12 (Matt 5.33–7); 4.10 (Matt 23.12/Luke 14.11, 18.14b).Footnote 8 Apart from the saying on oaths (Jas 5.12; cf. Matt 5.33–7), which does not betray any features of Matthean redaction, all of these allusions are either undisputed or disputed Q material. To these parallels, we might also add the likely allusions of Jas 4.4 (Q 16.13), 5.9 (Q 6.37–8), 5.10 (Q 6.22–3) and 5.19–20 (Q 17.3b).Footnote 9

Although Foster has expressed some reticence due to the lack of verbatim agreements between Q and James,Footnote 10 Kloppenborg’s emphasis upon the rhetorical practice of aemulatio has rather persuasively demonstrated that we should not expect James to have reproduced his sources verbatim, nor explicitly cited his sources.Footnote 11 Learning to paraphrase was a component of advanced rhetorical training,Footnote 12 prompting seasoned pupils to imagine themselves in a competition for excellence with their literary predecessors. The younger Pliny advocated for such an imagined rivalry to improve one’s prose:

When you have read an author sufficiently to master his subject and treatment, it will do you no harm to try and rival him, as it were, and write your version out, and then compare it with the book, carefully considering where the original is better expressed than your copy, and vice versa. You may justly congratulate yourself if yours is the superior in a few places, and you may be heartily ashamed of yourself if his beats yours at every point. Occasionally, you may with profit select some very well-known passages and try to improve even on them.Footnote 13

This kind of exercise, he maintained, would eventually enable oneself to surpass the facilities of many talented authors and orators of the past, composing text which, as Quintilian described, could ‘rival and vie with the original in the expression of the same thought’.Footnote 14 Just as Philo could freely paraphrase the Decalogue with little to no verbatim agreement with the Septuagint,Footnote 15 the fifth-century poet Nonnus of Panopolis took no issue in producing a paraphrastic account of the Gospel of John with considerable elaboration of key pericopes and sayings.Footnote 16 Nonnus could take, for instance, the simple saying ἐγὼ οὐκ εἰμὶ ἐκ τοῦ κόσμου τούτου (John 8.23) and greatly expand to: ξεῖνος ἔφυν κόσμοιο καὶ οὐ βροτὸν οἶδα τοκῆα· ξεῖνος ἐγὼ κόσμοιο καὶ αἰθέρος εἰμὶ πολίτης,Footnote 17 retaining only the original reference to the κόσμος.

Nor should we expect James to have always transmitted his sources verbatim. While James cites biblical texts verbatim on four occasions – probably to rival Paul’s citation of the same texts – the author is certainly capable of paraphrasing the Hebrew Bible and seems to adopt this same rhetorical praxis towards the Jesus tradition he receives in Q.Footnote 18 Jas 1.5–8 and 4.2c–3, for instance, are likely emulations of the ‘ask and you shall receive’ aphorism of Q 11.9–13, wherein the author deploys Q’s pairing of αἰτείτω–δοθήσεται in his own insistence upon petitioning God with the correct mental disposition.Footnote 19 With instances of rhetorical paraphrase located plentifully within the works of Josephus,Footnote 20 Origen,Footnote 21 Clement,Footnote 22 Apuleius,Footnote 23 SirachFootnote 24 and Seneca,Footnote 25 to name a few, verbatim reproduction of one’s source was not a prevailing virtue or goal. Rather, performing an aemulatio of one’s predecessors would simultaneously enable one’s audience to recognise the echoes of the parent text and offer the author the opportunity to innovate, develop and extend the argument for their own purposes.

To borrow the architectural concept of ‘adaptive reuse’, like how a developer can revitalise and reuse a heritage building for novel purposes, James’ emulation of Q material performs an adaptive reuse of the Jesus tradition. By emulating and embedding several allusions to Jesus’ sayings throughout his epistle, the author revitalises, extends and promotes continuity with older ‘heritage’ traditions, bringing the relevancy of Jesus’ sayings into new contexts and for his own interests. For Kloppenborg, James emends and elaborates these traditions to suit his interest in psychagogy and the cultivation of the soul, as he grounds his arguments not solely in appeals to the Hebrew Bible or Hellenistic philosophical thought but in allusions to the Jesus tradition for recognition by the Christ followers in his audience.Footnote 26

As we now turn to James’ potential role in the reconstruction of Q, I do not mean to assert that the author’s lack of verbatim agreement with Q should not give us pause. While persuasive in its plentiful (albeit subtle) appeals to the Jesus tradition, James’ failure to explicitly attribute these sayings to Jesus or faithfully reproduce any given saying restricts the extent to which the text can be used to reliably establish Q. As it is maintained, however, there is indeed some merit in deploying James as an independent witness to the Q material, particularly in the adjudication of whether the Lucan woes (6.24–6) originated in the Sayings Gospel.

3. A Case Study in James and the Reconstruction of Q: The Woes (Jas 4.9 //Q 6.21, 25b and Jas 5.1, 2–3 //Q 6.24–25b, 12.33b)

It is the minority view today to consider the woes against the rich (οἱ πλούσῐοι), those who are satiated (οἱ ἐμπεπλησμένοι) and those who are laughing (οἱ γελῶντες) as an original component of Q.Footnote 27 With the woes omitted from the IQP’s critical edition, 6.24–6 is usually taken as Lucan Sondergut. The traditional challenge against their inclusion is that it is curious for Matthew to have omitted the woes if he had known them, especially since Matthew’s extensive woes against the Pharisees (Matt 23.13–36) seemingly demonstrated that he ‘was not averse to such sayings’.Footnote 28 Many scholars who observe the presence of Lucan vocabulary have thus relegated the woes to special L material which must have been independent to the Beatitudes or not known to Matthew in any meaningful capacity.Footnote 29 There are, nevertheless, compelling reasons for considering the Lucan woes as Q material, without appealing to a hypothetical QLk to which Matthew had no access. Some scholars, for instance, have attempted to establish plausible reasons for Matthew’s omission, such as a desire to omit the materialistic woes in light of his ‘spiritualised’ BeatitudesFootnote 30 or an interest in developing the positive theme of righteousness for the disciples.Footnote 31 Others have noted that Q 6.24–6 is not solely the case where pairs of blessings and woes appear in Jewish thought (Ps 1.1–16, 146.5–9; Prov 8.34–6, 28.14; Ecclus 10.16–17; Wis 3.13–15), and have asserted that it is quite telling that several sets of woes are located in Q (10.13–15, 11.?39a?–44, 46b–52, 17.1), but never within L material.Footnote 32

Schürmann, however, has usefully tackled the question from a different angle.Footnote 33 Noting that both Matthew and Luke bear vestigial presences or ‘linguistic reminiscences’ (sprachliche Reminiszesen) of their sources even when they omit Q or Markan material, he remarks that Matthew may have inherited and omitted the woes as a component of Q since there are verbal reminiscences of the tradition throughout his Sermon. We can note, for instance, that one of Matthew’s additions to the Beatitudes μακάριοι οἱ πενθοῦντες, ὅτι αὐτοὶ παρακληθήσονται (5.4) bears lexical similarities with the woes in its address to πενθοῦντες (cf. Luke 6.25 ὅτι πενθήσετε καὶ κλαύσετε) and promised reward παρακληθήσονται (cf. Luke 6.24 ὅτι ἀπέχετε τὴν παράκλησιν ὑμῶν). The ψευδοπροφῆται of Luke 6.26 also parallels the Matthean Beatitude for those who have fallen victim to individuals who εἴπωσιν πᾶν πονηρὸν καθ’ ὑμῶν ψευδόμενοι ἕνεκεν ἐμοῦ (5.11). Frankemölle has even suggested that Matthew’s threefold didactic prayer in 6.2, 5, 16 may be influenced by the threefold structure of the woes, particularly, since they are structurally founded upon the verb ἀπέχω (cf. Luke 6.24).Footnote 34 The close parallelism between the Beatitudes and woes has also led Tuckett to conclude that the woes were likely an original component of Q as antitheses to the Beatitudes, having had no independent existence apart from them.Footnote 35

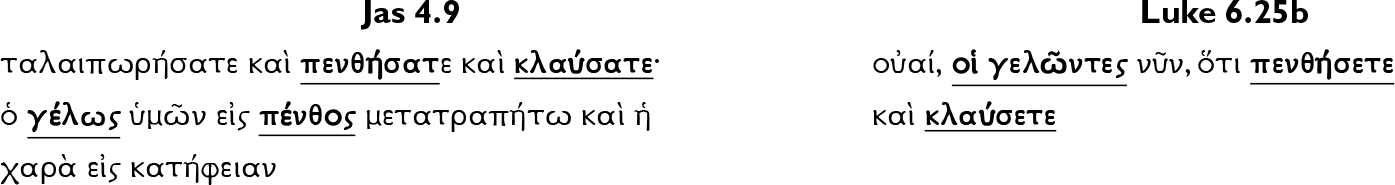

How might James help us in this contentious issue? We begin in Jas 4.9, the verse which immediately precedes our first case study (Jas 4.10). Nearing the conclusion of his indictment of envy, James has just instructed the ἁμαρτωλοί and δίψυχοι to purify their hearts and hands, and now directs them to humble themselves through the following behaviour: ταλαιπωρήσατε καὶ πενθήσατε καὶ κλαύσατε· ὁ γέλως ὑμῶν εἰς πένθος μετατραπήτω καὶ ἡ χαρὰ εἰς κατήφειαν (Jas 4.9). It is through this humility, he declares, that they will become exalted by the Lord (4.10). Interestingly, it is within James’ command in 4.9 for his audience to exchange their present laughter for lamentation, mourning and weeping that forms a compelling correspondence between James and the second woe in Luke 6.25b:

Both the woe against ‘those who laugh’ (6. 25b οἱ γελῶντες) and Jas 4.9 are directives in the second-person plural with a largely similar polemic toward worldly individuals. James, on the one hand, has rebuked arrogant and double-minded folk who have been enslaved to envy, selfish ambition and their pleasures (Jas 3.14–4.3), while Jesus similarly reviles the ‘haves’ of society, who are currently rich, satiated and laughing (Luke 6.24–6). Yet perhaps what is most striking here is the close lexical triad concerning laughter, mourning and weeping in both texts, since the woe of 6.25b and Jas 4.9 are the sole instances of the terminology of laughter (γελάω/γέλως) in the New Testament.Footnote 36 It is thus difficult to attribute the reference of οἱ γελῶντες to Lucan redactional interests due to the absence of any other reference to laughing in Luke-Acts or elsewhere.

Yet how can one be sure that James inherited the woes from Q if he fails to cite them verbatim? Through the theory of aemulatio or rhetorical paraphrase, if James had inherited the woes tradition, the excision of the οὐαί formulation, eschatological undertones and addition of καί ὁ χαρά εἰς κατήφεια are still perfectly sensible. Authors who engaged in rhetorical paraphrase were free to innovatively epitomise, extend or expand their predecessor texts as it fit their current purpose. Take, for instance, Nonnus of Panopolis’ paraphrase of the rather simple saying of Jn 15.4 μείνατε ἐν ἐμοὶ κἀγὼ ἐν ὑμῖν (‘abide in me as I abide in you’) into the following:

μίμνετε συμπεφυῶτες ἐμῷ παλιναυξέι θάμνῳ, μίμνετε συμπεφυῶτες ἐμοί, βλαστήματα κόσμου.

Stay, growing together into one, on my ever-growing plant; stay, growing together into one with me, off-shoots for the world.Footnote 37

The structure of the phrase has been dramatically transformed: the laconic expression of unity between Jesus and his disciples has doubled in length; John’s μένω has been altered to the closely related μίμνω (‘stay, abide’); the reciprocal κἀγὼ ἐν ὑμῖν has been excised; and there is a conspicuous addition of horticultural language (συμφύω, θάμνος, βλαστήματα) which nods to the viticultural language of Jesus as the ‘true vine’ in Jn 15.1–11. Nonnus, however, still retains the notion of Jesus’ embeddedness within the disciples through the interconnectedness implied in the verb συμφύω and the repetition of the imperative μίμνετε in the secondary clause, twice deploying the pronouns ἐμῷ/ἐμοί to replace the Johannine κἀγὼ ἐν ὑμῖν. Such an editorial process is indeed entirely possible for James, who is evidently quite capable of reworking and extending his inherited sources, as his allusions to the Hebrew Bible have demonstrated. In fact, Jas 4.9 is closer to the woe of 6.25b than Nonnus’ paraphrastic adaptation of Jn 15.4, with significant lexical and contextual parallels such as the triad of laughter–mourning–weeping.

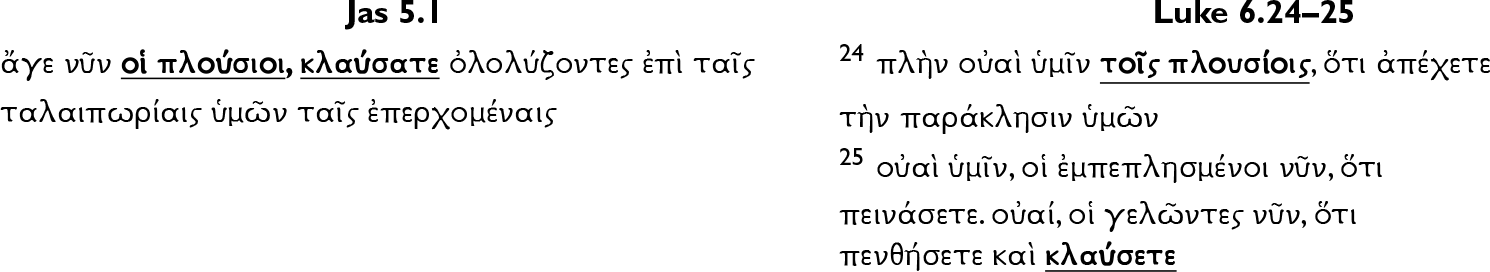

This is not all; in a passage with echoes of 4.9, Jas 5.1, 2–3 seems to betray further knowledge of Q and the woes. Compare, for instance, James’ denunciation of the wealthy (οἱ πλούσιοι) in Jas 5.1 with the woe against οἱ πλούσιοι in Q/Luke 6.24–5.

For James, the use of both κλαίω and ταλαιπωρία offer a link to Jas 4.9, with the former also promoting continuity with the woe of 6.25b ὅτι πενθήσετε καὶ κλαύσετε. James may have dispensed with the ‘woe’ prefix in favour of the Homeric ἄγε νῦν (cf. 4.13), but his reference to the wealthy’s imminent ταλαιπωρίαι preserves the overtly negative sense of the woes. Indeed, James’ vocabulary and construction of the phrase actually comes quite close to that of a woe. Not only are the terms οὐαὶ and ταλαιπωρία linked elsewhere such as in Jer 4.13 οὐαὶ ἡμῖν ὅτι ταλαιπωροῦμεν, they are interchangeable in GThom 87 and 112, and the woes pronounced over Babylon in Rev 18.10–11,15–16,19 are also strongly associated with those who weep (κλαίοντες) and mourn (πενθοῦντες).Footnote 38 Like other authors who engaged in rhetorical paraphrasing, James extends and develops the woe as he has received it in Q to fit his present purposes. Just as the rich have already received their comfort in the woe (6.24b), Jas 5.5 specifies the kinds of comforts they have enjoyed thus far which will soon be reversed: ἐτρυφήσατε ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς καὶ ἐσπαταλήσατε, ἐθρέψατε τὰς καρδίας ὑμῶν ἐν ἡμέρᾳ σφαγῆς. In addition to the reference to laughter, it is important to note that the present woe and Jas 5.1–6 are the sole instances of the direct condemnation of the rich in the second-person plural within the New Testament, and James here connects the two passages (4.9, 5.1) through lexical parallels. This correspondence seems best explained if we hold that James is emulating a text wherein those who are rich and those who are laughing are condemned; the most likely source is certainly the woes and even more likely, it seems that James has found the woes as a component of Q.

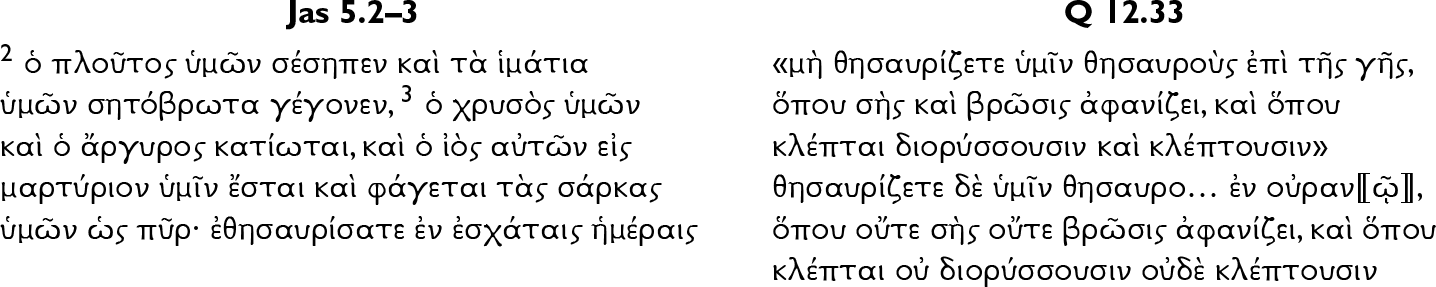

We may take this probable dependence even further. The rationale for Jas 5.1 in the succeeding two verses seems to have been composed with another Q text in mind:

In one of James’ closest parallels to the Jesus tradition, there are immediate convergences between the two texts. Rather than concentrating on the personal fate of the wealthy, Q 12.33 and Jas 5.2–3 are interested in the negative fate of their wealth, which is castigated by both as transitory and susceptible to decay.Footnote 39 In fact, James and Q mirror one another in their similar remarks about the dangers of material wealth – while Q 12.33 notes that one’s possessions are vulnerable to deface through moths (σής) and rust (βρῶσις), James instead notes that the rich’s clothing have become σητόβρωτα (‘moth-eaten’), thereby combining both words and elevating the terminology as we might expect for someone conducting a rhetorical paraphrase.Footnote 40 Moreover, the reference in Jas 5.3 to the wealthy having ‘laid up treasure in the last days’ (ἐθησαυρίσατε ἐν ἐσχάταις ἡμέραις) using the term θησαυρός recalls Q’s admonition μὴ θησαυρίζετε ὑμῖν θησαυροὺς ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς, with both texts emphasising an eschatological need not to collect material wealth, but rather treasures in heaven.Footnote 41 The allusion to Q material here aligns well with James’ thematic interests throughout the epistle, as he has already condemned the practice of patronage (2.1–13) and treated the wealthy with incessantly negative terms as individuals who will inevitably wither away (1.9–11; 5.1–6).

Where does this all leave us with James and the reconstruction of Q? Since there is no positive indication of James’ direct dependence on Luke (or Matthew, for that matter), it is quite plausible and probable that he knows Q, particularly in the Sermon material but additionally in several other sections of the Sayings Gospel. There are also good reasons, I have argued, for considering the traditional Lucan woes (6.24–6) as Q material which was composed to parallel the Beatitudes and which was later omitted by Matthew, even if he left certain vestigial traces of the tradition in his own gospel. It thus makes the best sense of the evidence not only to accept the widely held notion that James is dependent upon Q but to posit that he has inherited the woes from Q.

Foster has challenged James’ knowledge of the woes through Q, arguing that the woes ‘align with Lucan interests in Deuteronomic themes, and it is methodologically indefensible to introduce Sondergut material into Q simply because it solves a source-critical issue in James’.Footnote 42 Despite recognising the links between James and the woes, Hartin similarly excludes Luke 6.24–6 from Q and thereby denies James’ knowledge of the woes as a component of the author’s literary dependence upon Q. For Hartin, it is rather more plausible that both James and Luke are familiar with the woes as a later development of QLk to succeed the Beatitudes.Footnote 43 To these arguments, I contend that, first, Q is manifestly interested in Deuteronomistic theology, and we need not attribute the woes as indicative of a necessarily Lucan interest,Footnote 44 since Q contains several sets of woes (10.13–15, 11.?39a?–44,46b–52, 17.1), while none exist within L material. Second, this solution does not introduce Sondergut material into Q to resolve a source-critical issue in James – it rather experimentally deploys James’ knowledge of Q as an independent witness into the reconstruction of Q. Third, positing QLk as an origin for the woes cannot adequately explain their verbal reminiscences in Matthew’s Sermon and merely offers more hypothetical sources than rather simply accepting that Matthew had chosen to omit the woes he had inherited in Q. Simply put, in addition to his clear emulation of Q 12.33, Jas 4.9 and 5.1, 2–3 both largely rework and extend a tradition in which those who are wealthy and laughing are denounced, reprimanded for their dependence upon earthly possessions and encouraged to seek heavenly wealth – and the best answer for this hypothetical source is Q.

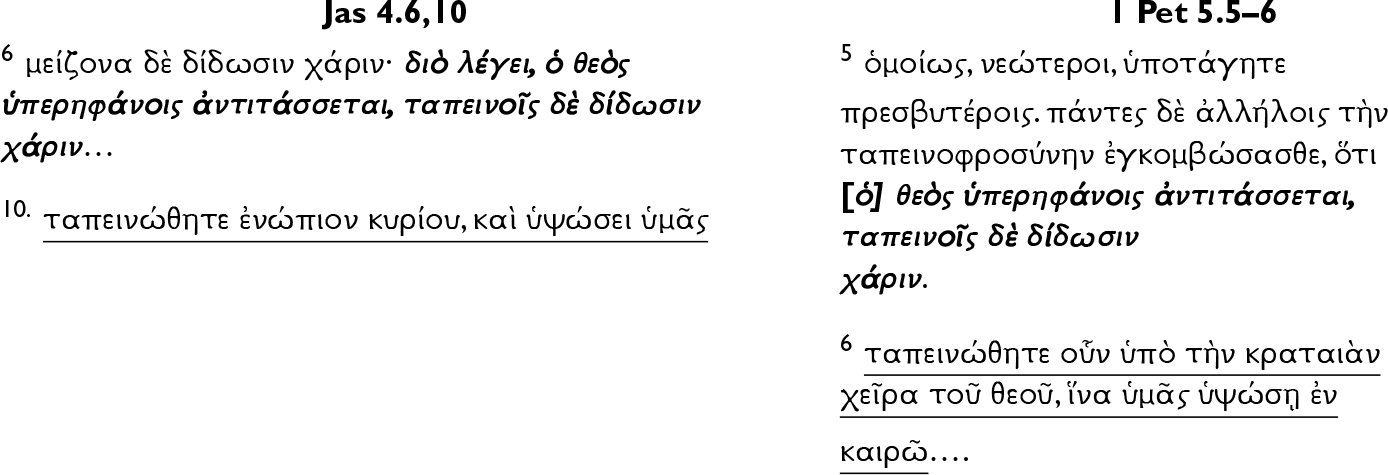

It remains to be seen whether the deployment of James is productive for adjudicating other issues in the reconstruction of Q. Future research would not only need to select case studies in which there is a high likelihood of a Jacobean paraphrase of Q material, but a passage in which there is a clear discrepancy between Matthew and Luke in the reconstructed Q text. For instance, while Jas 1.5, 17, 4.2c–3 clearly emulates elements of Q 11.9–13, the IQP text does not denote any problems in Q’s reconstruction, that is, irreconcilable differences between Matthew and Luke, and thus cannot be considered for the present experiment. In a slightly different issue, although the maxim of humility and exaltation in Jas 4.10 might initially bolster the inclusion of a remarkably similar maxim which is often attributed to Q (14.11/18.14?), the matter is far from conclusive. Jas 4.10 and Q 14.11/18.14? both employ the pair of ταπεινόω–ὑψόω, yet Deppe has convincingly cited several passages from the Hebrew Bible which employ this lexical pair in addition to the notion of humbling oneself ἐνώπιον κυρίου that is absent in Q (e.g. Job 5.11, Sir 2.17, Ezek 21.31 LXX, Isa 2.11, 10.33).Footnote 45 To complicate this matter further, if we accept James’ dependence on 1 Peter,Footnote 46 we observe that both 1 Peter 5.5–6 and Jas 4.6–10 have quoted a version of this maxim and have respectively positioned it after their citation of Prov 3.34:

Prov 3.34–5 might have inspired the humility–exaltation maxim in 1 Pet 5.5–6, and by extension Jas 4.10, since the dyad of ταπεινὸω–ὑψόω appears in Prov 3.35 directly after its quoted portion of v. 34 in both texts. Here, however, ὑψόω is deployed there in a negative sense concerning the fate of the impious: δόξαν σοφοὶ κληρονομήσουσιν οἱ δὲ ἀσεβεῖς ὕψωσαν ἀτιμίαν (Prov 3.35). Considering these limitations, although Jas 4.10 may closely resemble Q 14.11/18.14?, it does not make a convincing case for the text’s inclusion into the Sayings Gospel, unlike the case of the woes treated here.

We might caution, however, that the inclusion of the woes still imparts the methodological challenge of reconstructing their original form, a matter with which James cannot offer much help. It is likely that the earliest form of the woes displayed ‘precise symmetry’ and parallelism with the Beatitudes,Footnote 47 and elements of potential Lucan redaction can even be posited in his addition of παράκλησις in 6.24b (cf. Luke 2.25; Acts 4.36, 9.31, 13.15, 15.31), οἱ ἄνθρωποι (6.26, cf. 6.22), and the dual use of νῦν in 6.25.Footnote 48 Should we accept that the woes originated in Q, their proposed parallelism with the Beatitudes evinces a compositional technique not unlike the symmetry in its gendered coupletsFootnote 49 or the balancing of fates for the two builders (6.47–9). The text’s familiarity and stylistic preference for balanced rhetoric further implicates sub-elite village scribes as its authors, who would have been routinely exposed to this practice in legal and administrative documents.Footnote 50 Nevertheless, it is precisely James’ knowledge of the woes which can helpfully buttress the stance that the woes constituted an original component of Q’s Beatitudes. Perhaps the once-neglected ‘epistle of straw’ bears some merit in studies of the Synoptic Problem.

Competing interests

The author declares none.