1. Introduction

The temptation to ignore past acts of plagiarism in theology is great. Why direct attention to failures of long ago? Concerns about gossip and detraction may loom large in the minds of some. One major reason in favor of attention, however, pertains to the extended shelf life of scholarship in the field. Articles in theology do not ‘expire’ quickly, and older articles are regularly cited many decades after publication. These new citations to older articles testify to the enduring relevance of the scholarly contributions of earlier generations. Present-day students and scholars need to know, however, whether past scholarship is defective. When an older article is discovered to be substantially a work of plagiarism, two key interventions should be applied to limit further positive downstream citations to it: (1) an open discussion of the case, taking the form of post-publication peer review, and (2) a statement of retraction issued by the publisher.Footnote 1 Without these interventions, new generations of researchers will unwittingly regard a substantially plagiarized article as original and authentic, and citations to it will continue to accrue. Such misdirected citations distort the history of discovery in the field of theology, and they extend an unwarranted influence to the unoriginal article.Footnote 2

In 2019, The Bible Today issued a statement of retraction for two plagiarized articles that had been published in 1991 and 1993 by one author of record.Footnote 3 The passage of nearly three decades was not an impediment to correcting the published record. Indeed, the editors at several academic journals (as well as more popular venues) ultimately issued retractions for other biblically themed publications by the same author of record.Footnote 4 In issuing the retractions, the various editors were following standard research integrity practices for dealing with cases of research and publishing misconduct.

The present article brings to light an unrelated case of serial plagiarism involving articles in The Bible Today by a different author of record. The named author for the articles in question is Augustine Stock, O.S.B. (1920–2001), a longtime member of the Society of Biblical Literature and the Catholic Biblical Association of America. Stock published 7 monographs and more than 60 articles and book chapters over the course of half a century, and The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies lists him among major figures who contributed to new approaches ‘found in modern literary analyses of the biblical narratives’.Footnote 5 Even by 1964, prior to the publication of most of his articles and books, Stock was already judged to be worthy of mention in a historiographical overview celebrating the achievements of American biblical scholarship.Footnote 6 Downstream citations to Stock’s works reach into the thousands, and various publications of his have been commended by notable Catholic biblical scholars, including Raymond E. Brown, John P. Meier, Donald Senior, Adela Yarbro Collins, Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, and Avery Cardinal Dulles, among many others.Footnote 7 Stock’s publications are also commended in major reference works, ranging from The New Jerome Biblical Commentary to the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. Standard commentaries on scripture commend his publications.Footnote 8

During the period 1972–1985, Stock was the named author for four pieces that appeared in The Bible Today. These four short publications included exegetical articles on passages of the New Testament as well as more theoretical articles on how to interpret scripture.Footnote 9 The principal concern here will be two of those four articles. After setting forth the evidence of citation failures in both of those articles, the present article argues that the complexity of the cases is likely one reason why the problem has gone undiscovered. The history of positive downstream citations to the two articles illustrates how defective articles generate misattributions in the body of published research literature for extensive periods as later scholars credit the wrong researchers for discoveries.

2. Post-publication peer review

Some practitioners of theological scholarship may not support an open and candid discussion of problems in the field. One consideration in favor of the approach set forth here is the positive contribution that post-publication peer review has made in other disciplines. Post-publication peer review (PPPR) is a necessary task for ensuring the reliability of the body of published research literature. Its importance has been underscored in the natural, social, and biomedical sciences, but to a lesser degree in humanistic fields. One assessment puts the matter this way: ‘PPPR is having a rapidly increasing impact on science. Rigorous post-publication assessment of papers is crucial for the filtering and potential integration of meritorious data into the scientific collective.’Footnote 10 The re-evaluation of the reliability of published research should be viewed as an ongoing task shared by members of the scholarly community. One account frames the matter as: ‘post-publication review of any published manuscript can be done, independent of what kind of review it went through during the publication process’.Footnote 11 The platforms for post-publication peer review vary, ranging from traditional publishing venues (e.g., books and journal articles) to newer online venues.Footnote 12 The assessment of past publications – both in terms of trustworthiness and originality – should be approached as the obligation of practitioners in every field; research integrity is furthered by transparency. If scholars of other disciplines can offer open discussions of their problems, and those discussions have improved the quality and reliability of scholarship, then humanistic disciplines – including theology – should follow suit.Footnote 13

The information identified in this article is easily verifiable and presupposes no insider knowledge.Footnote 14 The research concerns academic publications in the field of Catholic biblical studies that have been in print for decades; all the facts have been in public view for a long time. To scrutinize what has been put forth in the public scholarly domain, residing there for decades, is not a violation of anyone’s privacy. When authors of record – and publishers at academic journals – issue articles, they implicitly warrant the reliability of what is published. No objection can be made if the published works are scrutinized by members of the community of scholars using the basic categories of research integrity. The focus in what follows is the relationship among texts and not biography.

The problem of plagiarism in Catholic biblical scholarship cannot be downplayed as some historical offense that possesses no import for today. The reason is clear and undeniable: the flow of continued positive downstream citations to the unoriginal articles shows that the problem reaches the present. Distinct acts of plagiarism committed in the past do not stay there, but they are immanentized with every new citation – made in good faith – by a later researcher. Publication should not be seen as the death of an article but its birth, and its long life is reflected in citations by later generations of scholars who engage a prior publication in their own new publications. The registration of downstream citations allows one to demonstrate the enduring influence of a given journal article across decades. Post-publication peer review of any defective articles is an ethical necessity for maintaining reliability of the body of published research.

When later researchers in good faith cite plagiarizing works, unwittingly crediting the plagiarized text – rather than the genuine author – for certain insights and discoveries, they allocate credit wrongly in a highly visible way. The genuine authors do not receive the recognition they deserve for the findings they have made. This misallocation of credit disrupts the argumentative lines in the published research of a field and distorts the history of discovery, impeding an accurate assessment of a discipline’s progress. The covert recycling of old insights as new also creates confusion for students and scholars who wish to assess the status quaestionis of a given issue. Plagiarism creates the illusion that prior scholarship on a given topic does not exist or is of such inferior quality that it does not deserve mention or credit. What is old is presented as new, and readers are thereby misled.

But plagiarism is not merely a misallocation of credit. The copied versions of passages are sometimes worse than their original versions in at least three ways. First, shorn of their original contexts, they lose layers of meaning and are thereby made less intelligible. Second, plagiarists do not always comprehend fully what they are copying, and hence what they produce can be a heap of borrowed sentences and paragraphs rather than a unified whole. Third, copied versions of texts can be inferior to their originals due to the introduction of unintentional copying errors.Footnote 15

Some theorists have proposed that the body of research literature should be conceived as ‘a daily workplace for millions of researchers and scholars across all career stages, where every publication can serve as key research equipment’.Footnote 16 The presence of any secretly defective or broken articles creates significant ‘safety hazards’ for practitioners. On this analogy, the body of research literature is deemed an ‘unsafe workplace’ for scholars. The needed interventions to improve the quality of scholarship include open discussions of defective articles in every field.

Thus, an exercise in post-publication review – such as the one offered in the present paper – is not a historical investigation possessing only antiquarian interest, but it consists of a real-time snapshot of problems in a field along with a contribution for improving it. In short, post-publication peer review is a necessary intervention for maintaining the reliability of published research literature for students and scholars.

3. The Bible Today as a venue for scholarship in biblical studies

The Bible Today commenced publication in 1962. Its appearance was a solution to a problem that had troubled members of the Catholic Biblical Association for decades. In 1939, the association had founded its flagship journal, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly, declaring at the time that ‘ours will be the only Catholic review devoted exclusively to the Bible in the English-speaking world’.Footnote 17 The problem, viewed in hindsight, was that ‘the original purposes of CBQ seemed to call for both a scientific and a popular journal, and this duality generated a kind of tension’.Footnote 18 That tension governing the first four decades of the journal was typically ‘resolved’ by privileging the academic manuscripts over the popular ones in publication decisions.Footnote 19 The real solution came about only with the founding of The Bible Today by members of the CBA via an independent venture with Liturgical Press. The new publishing venture was viewed as ‘a release for CBQ from the duty of popularization’.Footnote 20 As a result, The Bible Today ‘has flourished over the years as a superb model of haute vulgarisation and has freed up the CBQ as a vehicle of scholarly research’.Footnote 21

This theoretical dividing line between a strictly scholarly approach and a popular one in Catholic biblical studies has been asserted in various venues. The opening essay for the inaugural issue of The Bible Today in 1962 described the journal as ‘a publication that will provide a gradual and continuing education in the Bible for those who have not the time nor the background necessary to correlate all the published material’ and ‘the established conclusions of the scholars must be translated into meaningful phrases for them’.Footnote 22 The essay explained that the majority of contributors would be members of the CBA. Authors would be ‘thoroughly trained in biblical studies’ since ‘only the professional exegete’ could fulfill the goals established for the journal.Footnote 23 Much later, in a volume commemorating a half-century of publishing by Liturgical Press, an associate editor of The Bible Today located the journal’s founding within a Catholic popular biblical movement that began in the wake of Pope Pius XII’s encyclical on the study of scripture, Divino Afflante Spiritu.Footnote 24 The Bible Today does not accept submissions; all articles are commissioned by the editors on the basis of the reputation and scholarly competence of prospective authors.

Despite various attempts to demarcate a proper scholarly approach and from a popular one for the expression of research findings in area of biblical studies, in actual practice, the articles published in The Bible Today are regularly cited in academic works of biblical scholarship. The journal attracts a wide readership, both lay and expert, and the undeniable evidence of learned readers consists in the many downstream citations to its articles in a variety of scholarly journals and academic monographs. Stock’s four articles in The Bible Today are not an exception in this regard. Furthermore, the articles in the journal are catalogued and abstracted in standard research tools serving theologians and biblical scholars.Footnote 25

4. A new case of old plagiarism: Case 1

In 1982, The Bible Today published the second of Stock’s four articles in the journal. Titled ‘Resurrection Appearances and the Disciples’ Faith’, the study has been well received. Downstream citations to it can be found in well-regarded biblical commentaries and monographs.Footnote 26 Writing in 2000, liturgical theologian Mark Searle used Stock’s article as evidence for his claim that ‘recent scholarship has tended to place more emphasis on the encounters with the Risen One and to see the accounts of the empty tomb as secondary’.Footnote 27 The article in The Bible Today analyzes the post-resurrection episodes where the disciples meet Christ as variously recounted in the gospels of Mark, Luke, and John. In Stock’s article, select biblical passages are placed within a larger account that is informed by Thomas Aquinas’s views on the resurrection of Jesus as expressed in the Tertia pars of the Summa theologiae. The problem is that the most distinctive portions of Stock’s article overlap verbatim and near verbatim with unacknowledged sources by several authors.

4.1. The Thomistic account

The issue is exemplified by the last four paragraphs of Stock’s 1982 article; they consist of an uncredited re-presentation of sentences copied from three pages of a monograph titled Jesus in Gethsemane by Jesuit David Stanley that had been published two years earlier.Footnote 28 An accomplished scholar, Stanley was a member of the Pontifical Biblical Commission in the mid-1970s and served as president of the CBA in 1965–1966. Table 1 displays one example of how analyses by Stanley covertly reappear as Stock’s in the 1982 article. Stanley’s name does not appear anywhere in Stock’s article.

Table 1. Aquinas’s account of the resurrected Christ

The verbatim overlap is extensive, and the non-verbatim portions are largely due to synonym substitutions (e.g., ‘Gospels’ becomes ‘Scriptures’; ‘St. Thomas’ becomes ‘he’); paraphrasing (e.g., ‘observed appositely’ becomes ‘puts it’); as well as corrections (e.g., ‘defy’ becomes ‘defies’ and ‘explain’ becomes ‘explains’ for proper subject-verb agreement). These modifications are cosmetic; the substance of both accounts is the same, down to the particular quotation from the Summa theologiae and the overarching analysis of the Thomistic account of what it means to ‘see’ with faith.

4.2. Manipulations of Stanley’s research

Other articles published in The Bible Today at the time of Stock’s article regularly feature in-text citations and footnotes, but attributions of that sort are not present in Stock’s article. Undoubtedly, serving a wide readership – both popular as well as academic – may support a limitation to the number of references to the works of others, yet such constraints do not justify a total failure to acknowledge Stanley’s scholarship. Nor do such constraints justify the verbatim and near-verbatim copying of his text; biblical scholars are expected to write their own sentences. One does not find in the 1982 article a properly credited re-presentation of current advances in biblical scholarship, but only a covert suppression of authorship that creates the illusion of something new. Those who cite Stock’s article in their own research have unwittingly taken his words as original, when credit properly belongs to the uncredited sources.

Sometimes Stock manipulates a copied passage in a way that makes it especially difficult for a reader to trace the passage back to its true origin in the previously published work of a theologian. Table 2 displays a different passage that is copied from Stanley, but the principal difference is that Stock has silently replaced Stanley’s English translations of four verses from Luke’s gospel with translations from the RSV-CE.

Table 2. The Lucan account of the recognition of Jesus on the road to Emmaus

Stock’s main contribution is the substitution of one translation with another, while retaining Stanley’s analyses. Although much of this passage consists of a presentation of four quotations from Luke’s gospel, amidst the quotations are found Stanley’s particular insights about the meanings of the texts, including very particular claims that cannot be dismissed as commonplaces. Stock has condensed a slightly lengthier account found in Stanley’s book in fashioning this portion of the article in The Bible Today. The point remains: the analyses are not original to Stock, but only to Stanley.

4.3. Copying a distinctive source

Despite the above examples, the major undisclosed source for Stock’s 1982 article in The Bible Today is not Stanley’s monograph, however. That covert role belongs to a well-known work of scholarship: the 2-volume commentary on the gospel of John by Raymond E. Brown that was published a dozen years earlier (1966–1970) as part of The Anchor Bible series.Footnote 29 Brown is no small figure in biblical scholarship; he was described by a longtime editor of The Bible Today as ‘the foremost American Catholic biblical scholar of the twentieth century, with tremendous influence within and beyond the Catholic community’.Footnote 30 It is no exaggeration to say that Brown was ‘perhaps the best known Catholic biblical scholar of his time’, and Brown did not have to wait for a later generation to have his published scholarship recognized as possessing significant merit.Footnote 31 Brown himself authored articles in The Bible Today throughout his career, and two of them were reissued in a volume celebrating the best articles published during the first decade of the journal’s existence.Footnote 32

The covert re-presentation of the work of so famous a scholar as Brown, repackaged as a new interpretation in Stock’s 1982 article in The Bible Today, is notable. More surprising, however, may be that this fact has apparently been unrecognized in later decades, judging from the positive citations to Stock’s article in the downstream research literature. The uncredited source text by Stock is certainly not an obscure one. On one account, Brown’s ‘Anchor Bible commentary on the Fourth Gospel would remain Brown’s most significant academic achievement and would be the warrant for his academic credentials for the rest of his life’.Footnote 33 No hyperbole is required to state that Stock is copying the most famous work of the most famous scholar of American Catholic biblical scholarship, and Stock is presenting the copied text as his own within the pages of The Bible Today.

Table 3 displays how sentences taken from the second volume of Brown’s commentary on John have been refashioned and rearranged to produce the illusion of a new analysis. That volume of Brown’s commentary consists of 1208 pages, and Stock has copied from a small handful of passages in proximity (pages 1004, 1009–1011, 1014). Even with the rearrangement of text, the extent of verbatim and near-verbatim plagiarism remains, with strings of up to 63 verbatim words across sentences. Surprisingly, Brown’s words could still pass as new under Stock’s name in the pages of The Bible Today.

Table 3. Stock 1982 and Brown’s Anchor Bible volume on John

Stock has intervened upon Brown’s text with some paraphrasing. Brown’s expression ‘the Marcan Appendix (xvi 12)’ becomes in Stock’s article ‘the long ending to Mark’s Gospel […] (16:12)’. Stock preserves Brown’s use of the first-person plural pronoun ‘we’, but few – if any – readers of the text will realize that the ‘we’ is in fact Brown speaking rather than Stock. All the remaining changes are minor interventions upon Brown’s analysis.

The lack of attribution whereby Stock fails to credit Brown has a second layer of misdirection. Despite the extensive copying, one portion not carried over from Brown’s text is Brown’s attributive phrase ‘Dodd is correct in insisting that […]’, which immediately precedes the section were Stock has first started copying from Brown’s commentary. In the source text, Brown is crediting a book chapter by C. H. Dodd, another major scholar characterized in some historiographical overviews as ‘probably the most significant British NT scholar of the [20th] century’.Footnote 34

The excision of the portion of the passage whereby Brown offers credit to Dodd, in Stock’s act of copying Brown, generates further difficulties for readers in understanding the true origins the of insights regarding scripture that are being presented as original in Stock’s 1982 article. By stripping away the names of the true authors, as well as the authors credited in the source texts, a twofold misdirection is created to suggest that what is being offered to the reader is new, and with the resultant illusion that Stock is author of the biblical analysis presented with the pages of the short article. Readers do not see the continuity of interpretations endorsed by authoritative scholars, but instead they are presented with a façade of novelty.

4.4. Comparing genres of articles in biblical theology

To be clear: the 1982 article does not present itself as a précis of works by Stanley and Brown offered in condensed form to apprise readers of current movements in areas of New Testament studies. Rather, the article is presented as new work in biblical theology as if Stock were the true author. Articles of the former type, when done with explicit declarations of intent to readers about their purposes, can constitute especially valuable contributions, and articles of that type accord well with the orientation guiding the historical founding of The Bible Today as described above. Stock could have stated that Dodd, Brown, and Stanley have each published important works of research that deserve to be widely known, and Stock could have registered his agreement with any positions he found suitable in their respective publications. Attributions of that sort would have guided the reader (and later scholars who cite Stock’s articles) to draw correct conclusions about the origin and significance of the content that is being presented. As it stands, the article creates a disruption in the scholarly literature insofar as attention is directed away from the true authors of the sentences and paragraphs of the 1982 article.

Indeed, Stock is undoubtedly familiar with the genre of articles that are credited digests of the scholarly research findings by others that are written to popularize those findings to a wider audience. Stock’s earliest article in The Bible Today, his 1972 ‘Render to Caesar’, is precisely such an article. It summarizes, with continual invocations of its source, the then-recent research of J. Duncan M. Derrett concerning the line ‘render to Caesar’ found in the three synoptic gospels (Matthew 22:21; Mark 12:17; Luke 20:25). Derrett had examined the key phrase in a chapter of his 1970 monograph, Law in the New Testament.Footnote 35

Stock’s 1972 article presents, in a shortened form, the principal elements of Derrett’s findings. Throughout Stock’s 1972 account, the reader finds clear attributive guiderails that show that the insights of Derrett, rather than Stock, are being set forth. These markers include extract quotations from Derrett’s article with in-text citations to page numbers, as well as a variety of attributive phrases that credit the genuine author (e.g., ‘says Derrett’; ‘is preferred by Derrett’; ‘at this point Derrett interjects’; ‘claims Derrett’). Derrett’s name is mentioned ten times in Stock’s six-page article. Indeed, the closing paragraph of the article ends with Stock’s declaration, ‘we can conclude with Derrett […]’. The reader is left with no uncertainty about whose findings are being set forth in the article; the article offers an explicitly credited précis of Derrett’s work.

In a similar fashion, the last of Stock’s four articles in The Bible Today seems to be of this same genre. A summary of the work of others is provided, with explicit notices to the reader, and the account is replete with named authors, quoted extracts, and in-text citations. It appeared in September 1985 as ‘The Structure of Mark: A Five-Fold Concentric Framework’, and it is presented as a documented précis of the insights of certain authors who have located a chiastic structure in Mark’s gospel. The article is replete with attributions, introduced with clear declarations to the reader about various sources, including:

• ‘J. Lambrecht showed […]’

• ‘W. Marxsen understands […]’

• ‘F. Neirynk [sic] initiated […]’

• ‘Standaert had already indicated […]’

With such introductory phrases, no reader should mistake what follows those declarations to be the insights of Stock. Elsewhere in the article Stock is more explicit about the origins of the account being presented. Halfway through the article Stock declares to the reader, ‘What follows is a summary of van Iersel’s position worked out from an article in Dutch. Professor van Iersel was kind enough to pronounce this summary “free from real mistranslations”’.Footnote 36 The reader is thereby informed that the text is largely a collaboration between Stock and Bas M. F. van Iersel, produced so that an Anglophone audience might be made familiar with research findings originally expressed by an author who writes in Dutch. There is no suppression of authorship in that genre of article; such articles inform a wider audience about new trends in biblical scholarship and supplement the account with clear credit to relevant contributors. Despite serving a lay audience in addition a scholarly one, articles in The Bible Today can offer credit to prior scholarship.

5. A new case of old plagiarism: Case 2

The third of the four articles Stock published in The Bible Today is titled ‘Literary Criticism and Mark’s Mystery Play’. That article appeared in the February 1979 issue, and it seems to be an original and valuable contribution to biblical studies. Since its publication, it has enjoyed a warm reception in the downstream research literature, Major monographs and biblical commentaries, written from a variety of confessional perspectives, have commended it to readers.Footnote 37 All indications suggest that the 1979 article will continue to receive positive citations in future decades. The problem is that the article is substantially unoriginal: it is an undocumented anthology of passages appropriated from various books by several authors who remain either uncredited or deficiently credited. Key sentences in the 1979 article are unoriginal to it, but they are presented as if they constitute new research by the author of record. The extent of the overlap with previously published scholarship means that positive citations to the 1979 article in the downstream research literature often should have been directed instead to real authors whose sentences remain uncredited (or deficiently credited) in the 1979 article.

5.1. Simple copying

The unattributed copying in the 1979 article begins right away. The left column of Table 4 displays the second and third paragraphs of the article. The right column displays the real source text, which is a 1978 monograph by Donald Juel.Footnote 38

Table 4. Stock 1979 and Juel 1987

The overlap includes complete sentences and verbatim strings of up to 55 words across 2 sentences. The non-verbatim overlap, indicated by a lack of highlighting, is largely the result of minor changes by Stock (e.g., the orthographic alteration to render ‘esthetic’ as ‘aesthetic’; the replacement of ‘Scholars’ with the pronoun ‘They’). All the scholarly content in this portion of the 1979 article was already present in Juel’s then-new monograph. Oddly, Juel’s monograph is mentioned on the second page of the article, in the fifth paragraph, but not as the source for these preceding paragraphs. No quotation marks or in-text citations are present to disclose to the reader that the preceding words are unoriginal to the 1979 article. To the reader, Stock seems to be setting forth a new account of a trend that uses the tools of literary criticism to analyze biblical texts, with Juel invoked in a supporting role as just one among many others.

5.2. Two levels of manipulation

The defects in the 1979 article are typically more complex than the example of simple unattributed copying that was set forth in Table 4. The source texts themselves possess extract citations – with quotation marks and clear attribution – of the words of other scholars. When Stock copies a source text that itself contains a quotation from another author, he sometimes removes the name of that author and omits the quotation marks around the cited author’s words. This manipulation creates a twofold denial of credit. First, the author of the source text is not given credit for the words. Second, the author of the text cited by the source text is not given credit for those words either. Two classes of authors are thereby denied credit for their scholarship.

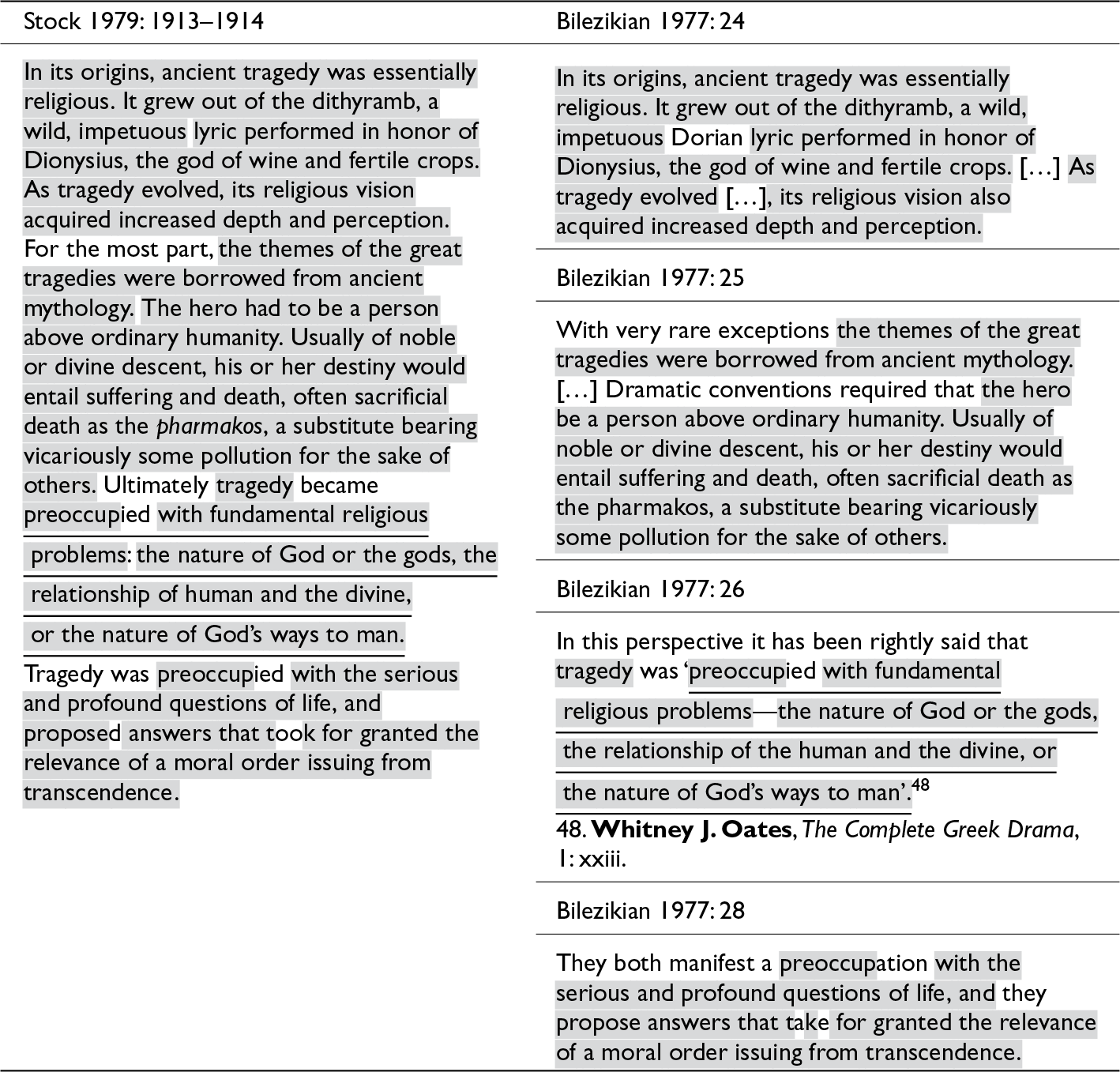

Table 5 provides an example of this dual-level manipulation. The left column displays a passage from the second half of the 1979 article. The right column reveals the uncredited source text for it: a 1977 book by Gilbert Bilezikian.Footnote 39 In the right column, bolding has been added to the name of an author – Whitney Oates – who is clearly credited by Bilezikian. In both columns, underlining displays the words of Oates as they appear as credited by Bilezikian and then as uncredited by Stock.

Table 5. How Oates 1938 appears in Stock 1979 through Bilezikian 1977

When readers encounter the 1979 article, they are led to believe that they are being presented with Stock’s insights about the origins of Greek tragedy and its potential influence on the composition of Mark’s gospel. As the table displays, however, readers are unwittingly being presented with sentences drawn from several pages of Bilezikian’s then-recent monograph. Furthermore, a text cited by Bilezikian – from Whitney Oates’s introductory essay in a 1938 anthology – is present in the 1979 article, but the quotation marks and footnote attribution that Bilezikian had correctly supplied have been quietly discarded.Footnote 40 The words of both Bilezikian and Oates thus show up in the 1979 article as if they were original to Stock. The copying includes complete sentences from Bilezikian of 8, 11, 32 verbatim words and also 26 verbatim words from Oates.

Bilezikian’s book appears to be the instrumental source by which Stock has accessed the words of Oates’s 1938 essay. In this act of copying, Stock claims originality for the words of both Bilezikian and Oates; their authorship has been effaced when their words reappear in the 1979 article. The highlighting displays that nearly all the passage is verbatim from Bilezikian’s text, and the part that is not verbatim is largely the result of minor alterations (e.g., ‘take’ becomes ‘took’).

No reader of the 1979 article is likely to know, on the basis of any signals given in the text itself, that the words of both Bilezikian and Oates are being presented without attribution as if they were original to Stock. The façade of originality is furthered by the presence of four fully documented extract quotations from Bilezikian elsewhere in the 1979 article. Those credited quotations sustain the illusion that Stock is following the standard rules of attribution throughout the article.

6. Gravity

Violations of research integrity admit of degrees of gravity. One way of dividing violations is according to kind. In the natural and biomedical sciences, the fabrication and falsification of empirical data are typically treated as the most serious, followed next by plagiarism. These three are commonly classified as FFP violations. A host of practices designated as ‘questionable research practices’ are typically classified next as lesser threats to the reliability of research.Footnote 41 Examples include ‘hypothesizing after the results are known’ (‘H.A.R.K.ing’) and data manipulation to attain statistically significant results (P-hacking). In humanistic disciplines, however, plagiarism remains the principal form of research misconduct. But even violations of plagiarism can be evaluated by degrees of severity. Some acts of plagiarism are more serious than others. A completely unoriginal paper can be assessed differently than a paper that merely copies one background sentence or two.

In considering the severity of particular acts of plagiarism, one should avoid a default application of the scholastic maxim bonum ex integra causa, malum ex quocumque defectu (a thing is good if what goes into it is entirely good, but bad if it is defective in any way). Post-publication peer review should privilege cases where the lack of originality is not incidental. In the case of Stock’s ‘Resurrection Appearances and the Disciples’ Faith’, and ‘Literary Criticism and Mark’s Mystery Play’, the unoriginal portions pertain the chief parts of each article. The copied sections, as the examples above show, cannot be dismissed as extrinsic or peripheral to the declared subject of each article.

7. Text recycling

A short biographical blurb about Stock appears toward the end of the 1979 article that states, ‘This article is part of a book on Mark in progress.’ In the 1982 article, a similar blurb asserts ‘The Gospel of Mark has been the object of a long study by Father Stock. The fruit of that study is a book entitled Call to Discipleship: A Literary Study of Mark’s Gospel.’ That monograph served as the inaugural volume of Good News Studies (1982–1995), a series of 41 books that featured such authors as John P. Meier, Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, Raymond F. Collins, Daniel J. Harrington, Jan Lambrecht, and Jerome Neyrey, among others.Footnote 42 (An edited collection in the series contained chapters by other notable scripture scholars, including Raymond E. Brown and Elisabeth Schüsser Fiorenza.) Stock’s inaugural volume repurposes sections of the both the 1979 and 1982 articles from The Bible Today across several chapters. When a deficient text is published a second time, it compounds the problem by occasioning further disruptions in the downstream research literature, drawing citations that should have been directed to the genuine authors of the words.

8. Conclusion

To stem the further misattributions in the downstream research literature, both the 1979 and 1982 articles in The Bible Today should not only be discussed in light of their defects but they should also be retracted. The issuance of statements of retraction for all substantially defective articles strengthens a journal’s reputation, since retractions are a public sign of the journal’s commitment to research and publishing integrity. Nevertheless, retraction notices alone do not suffice; they tend to be short, and they ‘are widely criticized for uninformativeness and opacity’.Footnote 43 PPPR provides the in-depth analysis that specifies the precise kind of misconduct, presents representative evidence, and offers credit to those whose works were copied. Without such interventions, yesterday’s plagiarism in The Bible Today will distort the scholarship of tomorrow.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the two peer reviewers for helpful critical comments. I am also thankful to the editors of New Blackfriars. I am especially indebted to Fr. Alkuin Schachenmayr, Pernille Harsting, Lawrence Masek, Michelle Dougherty, Leo Madden, Danny Garland, and Jeremy Skrzypek for helpful conversations.