Professional politicians often engage in linguistic classification by invoking the language/dialect dichotomy. Politicians may assign a particular linguistic variety the status of a distinct “language,” or, alternatively, deny that variety qualifies as “language” by declaring it a “dialect.” This article discusses a 2021 essay by Vladimir Putin as an unusually interesting example of such political rhetoric. The first half of Putin’s essay declared Ukrainian a “dialect” of Russian, but the second half depicted Ukrainian as a separate “language.” Participants in a language/dialect dispute typically take one side or the other, but Putin argued both sides. Exploring why Putin chose this curious rhetorical strategy not only illustrates how political actors invoke the language/dialect dichotomy to legitimize political claims but also shows that such claims are inherently problematic: political legitimacy ought not to rest on any particular linguistic taxonomy.

Putin’s essay “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” appeared on 12 July 2021, about six months before the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Politicians routinely use ghostwriters and the essay’s true author may never be known, but according to Andrew Wilson “Putin is widely assumed to have actually written it himself, which isn’t always the case with these kind[s] of things” (Wilson Reference Wilson2022, 0:52). Either way, Putin has clearly endorsed the article by claiming authorship and publishing it on the Kremlin website. His authorship will henceforth be assumed.

For a politician like Putin to invoke the language/dialect dichotomy is not in itself surprising. The language/dialect dichotomy is best understood as an arena of political contestation, not as a factual question to be resolved through linguistic analysis. Numerous theoretical linguists have insisted that the language/dialect dichotomy is “political, not linguistic,” to cite Noam Chomsky on “the definition of a language or a dialect” (Chomsky Reference Chomsky1977, 195; Chomsky Reference Chomsky1979, 190).

Indeed, one might juxtapose linguistic “agnosticism” that the dichotomy has any linguistic meaning with linguistic “assertionism,” a term intended to describe all those who accept the language/dialect dichotomy as a meaningful description of a linguistic variety. Assertionists may be further differentiated into “lumper” assertionists and “splitter” assertionists, respectively, defined by their desire to lump varieties together as “dialects” of a common language, or to split varieties into separate “languages.” As concerns Russian and Ukrainian, the “splitter” position posits a distinct Ukrainian language, while the “lumper” position treats Ukrainian and Russian as the same language, whether by classifying Ukrainian as a dialect of Russian or by classifying Ukrainian and Russian alike as dialects of some greater East Slavic whole.

The agnostic perspective views both lumper assertionism and splitter assertionism with equal skepticism. The dialect continuum stretching across the territory of the Ukrainian Republic shows gradual, continuous change, and no sharp linguistic discontinuity coincides with Ukraine’s political border with the Russian Federation. Even the crude methodology of sociological questionnaires quickly reveals linguistic complexities that confound any simplistic Ukrainian/Russian binary. When respondents were asked about their native language are permitted to choose the option “Ukrainian and Russian,” many declared themselves bilingual. When given the option, many claim to speak neither Ukrainian nor Russian but “Surzhyk,” a variety typically imagined as intermediate between the two. One sociolinguistic study rightly observed that including “dual and intermediate affiliations … undermines the sense in distinguishing two (or any) language groups” because Russian and Ukrainian “are neither fully formed, nor clearly separated from one another and appear as such only in a simplified view” (Shumlianskyi Reference Shumlianskyi2010, 137, 138; cf Bilaniuk Reference Bilaniuk2005, 103–142).

Agnosticism has the best claim to be the genuine linguistic position. Specialists in sociolinguistics, the branch of linguistics specifically devoted to the interaction between language and society, reject assertionism with a monotonous uniformity. Joshua Fishman, the founder of the Journal of Sociolinguistics, declared that “the dialect/language issue … is not resolvable on objective linguistic grounds alone” (Fishman Reference Fishman and Fishman1985, 6). A sociolinguistics textbook published by Cambridge University Press emphasized the point in italics: “there is no real distinction to draw between language and dialect” (Hudson Reference Hudson1980, 36). Another sociolinguistic textbook published by Oxford University Press judged the language/dialect dichotomy as “social and political rather than purely linguistic” (Reference SpolskySpolsky 1998, 30). Peter Trudgill’s sociolinguistic textbook not only declared that “there is no way to answer these questions on linguistic grounds,” but complained that “it seems that it is only linguists who fully understand the extent to which these are not linguistic questions” (Trudgill Reference Trudgill1995, 145).

If the issues raised by the language/dialect dichotomy are not linguistic but political, then assertionist positions are inevitably political stances. There is no sense in trying to analyze a political stance on purely linguistic grounds. Recognizing the language/dialect dichotomy as a field of political contestation, however, shows that it is appropriate for politicians to have an opinion: a politician’s job, after all, is to take a position on political questions.

The Politics of the Language/Dialect Dichotomy and Ukraine

What, then, are the political issues at stake in a language/dialect argument? In many parts of the world, but perhaps particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, perceptions of political legitimacy have been strongly influenced by an ideology Tomasz Kamusella has eloquently called “the normative isomorphism of language, nation and state.” Indeed, Kamusella memorably summarized it with a “handy algebraic-like equation language = nation = state” (Kamusella Reference Kamusella2022, 212, xiv, 66).

Nationalism theorists might recognize normative isomorphism as the linguistic counterpart of “ethnic nationalism.” Numerous theorists have pointed out that the simplistic civic/ethnic dichotomy does not capture the complexity of nationalism as observed in practice (Yack Reference Yack1996; Nikolas Reference Nikolas1999; Brubaker Reference Brubaker and Kriesi1999; Shulman Reference Shulman2002; Subotić Reference Subotić2005), but normative isomorphism, like “ethnic nationalism,” is best understood as an abstract ideal whose concrete individual manifestations require further analysis. Nevertheless, both ethnic nationalism and normative isomorphism inspire dreams of purity, policies of forceful assimilation, and the oppression of minority communities.

In the Ukrainian context, normative isomorphism means that the language/dialect dichotomy has political ramifications. Splitter assertionism, proclaiming the existence of a Ukrainian “language,” justifies an independent Ukrainian state: the independent language implies an independent nation with the right to an independent state. Conversely, lumper assertionism, denying that Ukrainian qualifies as a distinct “language,” undermines Ukrainian claims to statehood: denying Ukrainian the status of a language denies the existence of a Ukrainian nation and thus the legitimacy of a Ukrainian state. Classifying Ukrainian as a “dialect of Russian,” furthermore, gives the Russian Federation a claim to Ukrainian territory, at least according to the ideology of normative isomorphism.

In practice, normative isomorphism has never been an accurate description of either Russian or Ukrainian political loyalties. Within Russia itself, ethnolinguistic diversity has inspired different approaches to being “Russian.” The politics of distinguishing between the supposedly “ethnic” adjective русский [= russkij] and the supposedly “civic” adjective российский [= rossijskij] prove complex (Komalova and Sergeev Reference Komalova and Sergeev2018; Laruelle, Grek, Davydov Reference Laruelle, Grek and Davydov2023; Blakkisrud, Reference Blakkisrud2023). Nevertheless, citizens of the Russian Federation whose native language is not Russian often choose to proclaim themselves rossijskij but not russkij (Saarikivi Reference Saarikivi, Skutnabb-Kangas and Phillipson2022, 541).

The historical record also abounds with Ukrainians proclaiming themselves “Russian” in some linguistic or cultural sense, while expressing political loyalty to another state. In 1908, for example, Galician parliamentarian Mykola Hlibovyckyj of the “Old Ruthenian club” declared that his native language was Russian, not Ukrainian, while simultaneously insisting that his Russian ethnicity was compatible with Austrian loyalty: “Russisch heißt nicht Rußländisch” (Hlibovyckyj Reference Mykola1908, 4716). More recently, Oleksii Nikiforov, a Russian-speaking Ukrainian citizen, declared that “a nation [нация = natsiya] is when regardless of nationality [национальност = natsional′nost], you feel belonging to a people [к народу = k narodu]. That is, I cannot speak Ukrainian nicely, I am Russian by nationality [по национальности = po natsional′nosti], but I am a Ukrainian” (cited from Eminova Reference Eminova2015). The Russophone loyalties that Hlibovyckyj or Nikiforov articulated may generate suspicion in certain Ukrainian nationalist circles but are no less valid for that. Nikiforov, in any event, unmistakably demonstrated his loyalty to Ukraine: in 2014, he served in Crimea as a soldier in the Ukrainian armed forces.

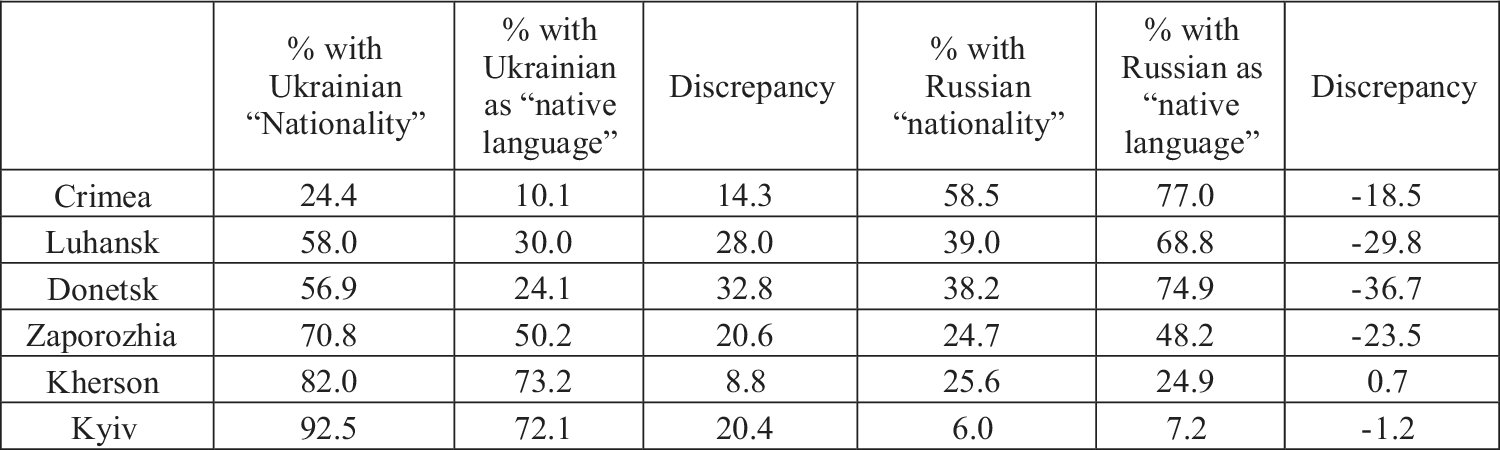

The failure of normative isomorphism is even visible in Ukrainian census data. Independent Ukraine has so far only held one census, the 2001 All-Ukrainian census. Even leaving aside the particular problems Dominique Arel has identified with its methodology (Arel Reference Arel2002), censuses, in general, are crude tools for probing national and linguistic loyalties because census officials tend to reify ethnic categories and ignore national indifference (Ver Reference Ver, Berliner, Bialer and Fitzpatrick1984; Kerzer & Arel Reference Kertzer, Arel, Kertzer and Arel2002; Zahra Reference Zahra2010). Nevertheless, even the most naïve reading of the 2001 All-Ukrainian census suggests that a demographically significant share of the population in Eastern Ukraine claims Russian as their “native language” [рідна мова = ridna mova / родной язык = rodnoy yazyk] without claiming Russian “nationality” [националнист = natsional′nist′ / националъностъ = natsional′nost], and, conversely, that many claim Ukrainian “nationality” without claiming Ukrainian as their “native language.” Figure 1 illustrates these discrepancies for the five oblasts of the 1991 Ukrainian state that the Russian Federation has sought to annex, adding Kyiv as a point of comparison (All-Ukrainian Census, 2001). The census figures suggest that more than one-fifth of the population of Zaporozhia, more than one-quarter of the population of Luhansk, and around a third of the population of Donetsk, claim to be Ukrainians by “nationality” but speak Russian as their “native language.” Speakers of Russian who claim Ukrainian nationality contradict normative isomorphism.

Figure 1. Discrepancies between Russian and Ukrainian “Nationality” and “Native Language” for selected Ukrainian regions (All-Ukrainian Census 2001).

Despite such inaccuracies, however, normative isomorphism remains popular, and Ukrainian patriots are often outspoken in their splitter assertionism. Ukrainian journalists have written articles providing “proofs that Ukrainian is not a dialect of Russian” (Kryzhanivska Reference Kryzhanivska2021), or “confirmations” that “the Ukrainian and Russian languages are very different grammatically, phonetically, orthographically” (Mashchenko Reference Mashchenko2022). Such proofs and confirmations owe their popularity to their perceived ability to legitimate Ukraine as an independent state.

Indeed, splitter assertionism in service of normative isomorphism extends from popular journalism to academic circles. Several Ukrainian philologists have argued the splitter assertionist case by compiling lists of differences between Ukrainian and Russian and calculating lexicostatistical differences (Tyshchenko Reference Tyshchenko2012, 56–58). Western linguists, who really ought to know better, have also succumbed to the temptations of splitter assertionism. A group of American linguists recently calculated “average lexical similarity” scores between Ukrainian and Russian by applying the Levenshtein algorithm to a corpus of movie subtitles. Defying the agnostic consensus of theoretical sociolinguistics, they concluded that “there is no question about the reality of their being two distinct languages” (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Whalen, Dubinsky, Gavin, Bailyn and Ginn2023, 1).

These assertionist claims, however, rest on weak epistemological foundations, since the amassed linguistic trivia proves nothing without some definition of what distinguishes “languages” from “dialects.” Assertionist articles generally fail to provide any such definition. British Slavist Niel Bermel, citing Tishchenko’s lexical distance calculations, argued that Russian and Ukrainian “share a lot of basic and core vocabulary – but not enough to be considered dialects of a single language.” Bermel neglected to specify how much shared vocabulary would be considered “enough” (Bermel Reference Bermel2022). Similarly, the American linguists mentioned above alluded merely to what “one would expect from two varieties of the same language” (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Whalen, Dubinsky, Gavin, Bailyn and Ginn2023, 9). They do not explain how anyone could know what to expect from their methodology, or provide any other figures for purposes of comparison.

Extensively documenting linguistic differences between Ukrainian and Russian flatters popular splitter assertionism in Ukrainian nationalist and Ukrainophile circles, but does little to persuade lumper assertionists. Lumper assertionists can acknowledge linguistic diversity: every “language” contains internal diversity, including Ukrainian, as numerous Ukrainian dialectologists have documented (Del Gaudio Reference Del Gaudio2017; Žylko Reference Žylko1966, 314–315; Shevelov Reference Shevelov, Comrie and Corbett1993, 994). There is no linguistic procedure for determining whether a particular linguistic difference, such as a vowel shift, indicates a difference between “languages” or a difference between “dialects.” Thus, lumper assertionists can always declare that any differences are merely “dialectical” (for example, Samsonov Reference Samsonov2022).

Splitter assertionism insists that the differences between “Ukrainian” and “Russian” are more important than similarities; lumper assertionism that the similarities are more important than differences. Judgements about “importance,” however, are inevitably value judgements, and as such are contextual. One must always ask: important to whom? Important for what purpose? Judgements of importance are value judgements, and no value judgement can ever be an objective truth. The agnostic position is therefore correct: there is no objective way to say whether, for example, Ukrainian is “really” a language or “really” a dialect.

One can, however, meaningfully study what opinions people hold about the language/dialect dichotomy and how those opinions change over time. Instead of asking whether the splitter assertionist position or the lumper assertionist position is “correct” an agnostic approach to language/dialect disputes investigates their respective popularity. Is there a consensus view? Alternatively, is there a majority opinion and a minority opinion? What is the relative strength of the majority and the minority? Who supports the lumper position, and who supports the splitter position? How fervently do participants in the language/dialect debate express their opinions? What do they believe is at stake?

As specifically concerns Ukrainian and Russian, we may observe that a strong majority has supported splitter assertionism for decades, even if Russian nationalists have recently been contesting it vigorously. Consider, as a test of expert opinion, reference works discussing the Slavic linguistic zone. A 2015 study comparing the entries for “Slavic languages” printed in various encyclopedias found that between 1917 and 2000 only three encyclopedias categorized Ukrainian as a “dialect” (or other subcategory) of Russian. By contrast, 27 encyclopedias recognized Ukrainian as a “language,” and another two acknowledged a distinct “Ruthenian” or “Little Russian” “language.” If we ignore the diversity of glottonym, then 90% of encyclopedia entries published between 1917-2000 acknowledged a distinct Ukrainian “language.” Among the 20 encyclopedias published since 1950, furthermore, all 20 acknowledged the Ukrainian language under the glottonym “Ukrainian.” For a century, in short, splitter assertionism has been the consensus opinion about Ukrainian, at least among the experts who write encyclopedia entries (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2015, 43–45).

At the same time, however, the same study demonstrated that over the past two hundred years, Slavists have changed their minds about the number of extant Slavic “languages.” In the early 19th century, most experts posited not “Ukrainian” but either “Ruthenian” or “Little Russian,” which they imagined “either as a subcategory of ‘Russian,’ or not at all.” Slavists have only recognized a distinct Ukrainian “language” only since the early 20th century. Nor is the emergence of Ukrainian a unique phenomenon. A strong majority has recognized a Macedonian language since around 1960, but hardly any encyclopedia entry authors acknowledged a Macedonian language before the Second World War (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2015, 35–36, 43–45).

When analyzing the status of a “language” as a question of popularity, scholars must also remember that even a consensus opinion does not imply universal agreement: there are always eccentrics and cranks. If linguistic assertionism is a value judgement about the importance of linguistic differences, then scholars must confront two irrefutable truths: values change over time, and some people have atypical values. Perhaps the most overwhelmingly accepted political consensus in contemporary Europe concerns the wickedness of Hitler: moral condemnation of Nazi Germany is so universal that the epithet “Nazi” has degenerated into the laziest of insults. Nevertheless, neo-Nazis exist, and before the Second World War so did the actual Nazis themselves. Nor can all minority views be stigmatized and dismissed the way neo-Nazis ought to be. After all, from 1800 to 1850 the notion of a “Ukrainian language” was an eccentric view. The subsequent agreement that the Ukrainian language exists reminds us that one generation’s marginal eccentricity can become another generation’s consensus. Eccentric cranks sometimes turn out to be visionaries, ahead of their time.

If linguistic taxonomies evolve over time, and if one generation’s eccentric minority opinion can become another generation’s consensus view, then it seems unremarkable that Ukrainian citizens of Russophile political convictions would contest the splitter assertionist consensus regarding Ukrainian. Scepticism about the distinctiveness of the Ukrainian “language” indeed predates Ukraine’s military confrontation with the Russian Federation (see, for example, Fournier Reference Fournier2002, 424, 427–428, 432; Shumlianskyi Reference Shumlianskyi2010, 148–149). Scholars investigating such scepticism, furthermore, ought to discuss it dispassionately. While Michael Moser has usefully documented lumper assertionism in his study of “anti-Galician” internet discourse, his Ukrainophile discussion article proved inappropriately partisan. Moser characterized Russophile talking points as “absurd propaganda,” “certain Russian chauvinist traditions,” “general anti-Ukrainian and ultimately anti-European discourse,” “totalitarian, anti-democratic, anti-Western (and often anti-Semitic) ideology,” and “certain linguistic ideologies, which … deserve to be studied, regardless of their intellectual level, which quite often appears to be very low” (Moser Reference Moser, Larissa and Maria2014, 318, 319). Such epithets are more pejorative than analytical. They establish Moser’s credentials as a friend of Ukraine but undermine his credibility as an analyst of Russophile sentiment.

The majority of Western scholars articulate a splitter assertionist position about the existence of a Ukrainian language, just as the majority of political actors recognize the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state. Nevertheless, majority views are often contested, and political actors routinely seek to undermine the legitimacy of one state or another. Language/dialect disputes, when viewed from the perspective of normative isomorphism, articulate different views of legitimate statehood. Lumper assertionism in Ukraine is thus an essentially normal and unsurprising type of politics. Scholars analyzing political rhetoric, furthermore, should be able to discuss and analyze political positions they do not themselves espouse. With these thoughts in mind, let us now consider how Putin invoked the language/dialect dichotomy in his 2022 essay.

Putin as Lumper Assertionist: The Ukrainian “dialect” and the Triune National Concept

Throughout his 2022 essay justifying the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Putin espoused normative isomorphism. Putin began his essay with a narrative of Russian-Ukrainian history, depicting Ukrainians and Russians as single people speaking a single “language.” The opening half of the essay, in short, articulated lumper assertionism. By denying Ukrainian linguistic distinctiveness, Putin denied the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state.

Putin’s historical narrative begins in the Middle Ages. The earliest chronicles from the era of Kyivan/Kievan Rus’ supposedly show that “Slavic and other tribes across the vast territory – from Ladoga, Novgorod, and Pskov to Kiev and Chernigov – were bound together by one language (which we now refer to as Old Russian).” In the early modern period, during the rivalry between Muscovy and the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, “people both in the western and eastern Russian lands spoke the same language,” and when the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth oppressed its Orthodox inhabitants, they crossed the Dniepr seeking “support from people who spoke the same language and had the same faith.” As recently as the 18th century, the “incorporation of the western Russian lands into the single state was not merely the result of political and diplomatic decisions. It was underlain by the common faith, shared cultural traditions, and – I would like to emphasize it once again – language similarity” (Putin Reference Putin2021).

Putin did acknowledge increasing linguistic diversity over time. He imagined “one language” or “the same language” in the more distant past but by the 18th century only “language similarity.” Putin attributed the emergence of linguistic divisions to foreign influence, and specifically to “Polish-Austrian ideologists.” Supposedly, “the idea of Ukrainian people as a nation separate from the Russians” first arose among “the Polish elite,” but by the 19th century “Austro-Hungarian authorities had latched onto this narrative … as a counterbalance to the Polish national movement and pro-Muscovite sentiments in Galicia” (Putin Reference Putin2021).

To downplay the importance of these emerging linguistic differences, Putin invoked the language/dialect dichotomy. He conceded that “living within different states naturally brought about regional language peculiarities, resulting in the emergence of dialects.” These “dialectical” differences did not, however, estrange Ukrainians from the Russian language. Instead, Putin argued,

The vernacular enriched the literary language. Ivan Kotlyarevsky, Grigory Skovoroda, and Taras Shevchenko played a huge role here. Their works are our common literary and cultural heritage. Taras Shevchenko wrote poetry in the Ukrainian language, and prose mainly in Russian. The books of Nikolay Gogol, a Russian patriot and native of Poltavshchyna, are written in Russian, bristling with Malorussian folk sayings and motifs. How can this heritage be divided between Russia and Ukraine? And why do it? (Putin Reference Putin2021).

Though this passage explicitly recognized “the Ukrainian language” as something in which Shevchenko wrote poetry, it depicts Ukrainian not as something alien to the Russian language, but as part of a common heritage shared by Ukrainians and Russians alike. Famous cultural heroes supposedly switched without effort from Ukrainian to Russian. It would be impossible to divide Ukrainian from Russian, and indeed why would anybody seek that division? With this celebration of linguistic differences, Putin here essentially argued that diversity leads to cultural enrichment, ironically recalling Western notions of multiculturalism.

Putin proclaimed linguistic unity between Russians and Ukrainians to argue that Ukrainians and Russians belong to the same nation. He specifically posited a “triune people comprising Velikorussians, Malorussians and Belorussians.” Putin’s vision of “a single large nation, a triune nation” denies the existence of a distinct Ukrainian nation; the triune concept instead posits Little Russian, Great Russian, and White Russian subcomponents of larger all-Russian nation (Putin Reference Putin2021). Since the triune concept denies not only the national distinctiveness of Ukraine but also that of Belarus, perhaps it is worth noting Putin has also espoused the triune national concept when speaking to Belarussians. On 12 April 2022, during the second month of the war, he told a Belarussian journalist: “We do not distinguish where Belarus ends and Russia begins, where is Russia and where is Belarus … I have always said that we are a triune people: Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia” (Putin Reference Putin2022a).

Putin did not invent the triune concept from thin air: both its linguistic and ethnographic incarnations can boast a long history. Triune nationalism became the official position of the Romanov government during the 19th century (Miller Reference Miller2003; Plokhy Reference Plokhy2006a, 299–353; Kravchenko Reference Kravchenko2019), and it still enjoys considerable support in contemporary Russian nationalist circles (Fournier Reference Fournier2002; Kolstø Reference Kolstø2023). Before the First World War, furthermore, Russophile sentiments were espoused by “Ukrainian” intellectuals in Eastern Galicia (Sereda Reference Sereda2001; Zayarnyuk Reference Zayarnyuk2010), in Transcarpathia (Mazur Reference Mazur2017, 47–53; Kovalchuk Reference Kovalchuk2021), and Romanov Ukraine (Plokhy Reference Plokhy2006b; Korolov Reference Korolov2021).

When combined with normative isomorphism, the triune national concept gives Moscow a territorial claim to Ukraine. The triune concept subordinates a Ukrainian “dialect” within a greater All-Russian “language.” According to normative isomorphism, the common language implies a common nation, and the common nation implies that Ukraine and Russia should belong to the same state. When Putin noted that Moscow had previously served as “the center of reunification, continuing the tradition of ancient Russian statehood,” furthermore, he implicitly declared the Russian Federation’s right to resume the same tradition in the 21st century (Putin Reference Putin2021). As Tom Casier put it, “Russia could only be great Russia if it constituted a greater Russia” (Casier Reference Casier2023, 21). In the first half of his essay, therefore, Putin used lumper assertionism to undermine the legitimacy of Ukrainian statehood. According to the logic of normative isomorphism, the triune language concept justifies the Russian Federation’s annexation of the entire Ukrainian republic.

Putin as Splitter Assertionist: The Ukrainian “language” as Threat

In the second half of his essay, however, Putin embraced splitter assertionism, depicting Ukrainian and Russian as fundamentally different languages. Splitter assertionism arose during Putin’s discussion of linguistic policies in post-Soviet Ukraine. Putin depicted Ukrainian as a “language” to depict Ukrainianization as the denationalization of ethnic Russians. The second half of the essay also justifies the 2022 invasion, but not the annexation of Ukraine as a whole. Instead, the second half of the essay justifies the annexation only of Ukraine’s predominantly Russian south-eastern territories.

Linguistic questions have played a prominent and divisive role in the political life of independent Ukraine. Ukrainian politicians have not legislated in a vacuum, but have been pressured by outside powers. As a precondition for joining the Council of Europe, the European Union in 1995 required Ukraine to ratify both the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Both the Convention and the Charter, if applied to Ukraine, would guarantee various rights for Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population. The Ukrainian authorities duly passed the appropriate laws in 1997 and 1999, but the 1999 law was repealed in 2000, and replaced by a new law only in 2003. In 2012, the Ukrainian government, then led by the pro-Russian “Party of Regions,” passed a new language law, sometimes called the Kivalov-Kolesnychenko law, granting “regional languages [rehional′ni movi = регіональні мови],” including Russian, greater salience in local administration. The Kivalov-Kolesnychenko law was, however, repealed after the 2014 Maidan Revolution, and in 2018 declared unconstitutional. A further 2017 law imposed Ukrainian as the sole medium of secondary and tertiary education throughout Ukraine. Throughout, public debate on linguistic issues has been inflammatory and divisive (Kuts′ Reference Kuts′2004; Besters-Dilger Reference Besters-Dilger2009; Moser Reference Moser2013; Reznik Reference Reznik and Andrews2018; Csernicskó Reference Csernicskó, Kornélia, Zoltán, Anita, Réka and Enikő2020; Knoblock Reference Knoblock2020).

The second half of Putin’s essay justifies Donbas separatism with reference to Ukrainian language laws. The post-Maidan Ukrainian authorities, whom Putin accuses of consorting with “radicals and neo-Nazis,” have supposedly sown division by attacking “the things that united us and bring us together.” Putin claimed, furthermore, that

people in the southeast peacefully tried to defend their stance. Yet, all of them, including children, were labeled as separatists and terrorists. They were threatened with ethnic cleansing and the use of military force. And the residents of Donetsk and Lugansk took up arms to defend their home, their language and their lives (Putin Reference Putin2021).

Putin’s narrative thus depicted Ukraine’s Russian minority as driven to rebellion by unendurable oppression.

Of all precious things supposedly endangered by the post-Maidan Ukrainian authorities, Putin listed “first and foremost, the Russian language,” threatened by assimiliationist policies.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the path of forced assimilation, the formation of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state, aggressive towards Russia, is comparable in its consequences to the use of weapons of mass destruction against us. As a result of such a harsh and artificial division of Russians and Ukrainians, the Russian people in all may decrease by hundreds of thousands or even millions.

Putin specifically complained that “the new ‘Maidan’ authorities first tried to repeal the law on state language policy,” that is, the 2012 Kivalov-Kolesnychenko law, by imposing Ukrainian in place of Russian in local administration. Putin also attacked the 2017 education law as “the law on education that virtually cut the Russian language out of the educational process” (Putin Reference Putin2021). Putin argued that laws promoting the Ukrainian language violate the national rights of Russophone Ukrainian citizens. Taken in conjunction with various other anti-Russian policies, such laws supposedly posed a dangerous threat to the Russian people. The Russian Federation invaded as a reaction to that threat.

According to the triune national concept, however, the Ukrainian language cannot threaten the Russian people. The triune theory views Ukrainians as already belonging to a greater All-Russian whole. Ukrainianization can only threaten the Russian language if Ukrainian and Russian are significantly different languages.

The second half of Putin’s article therefore assumes that the Ukrainian language is no longer part of a common heritage shared between Russia and Ukraine. The Ukrainian language has become something alien to the Russian language; Russians can switch from Russian to Ukrainian only with great effort. Describing the triune concept in the first half of his article, Putin asked: “what difference does it make who people consider themselves to be – Russians, Ukrainians, or Belarusians?” In the second half of Putin’s essay, by contrast, it makes a big difference, since imposing Ukrainian on Russian speakers “involves a forced change of identity” (Putin Reference Putin2021). The second half of his essay, therefore, Putin abandoned both the triune national concept and lumper assertionism, espousing splitter assertionism instead.

How, according to Putin, did the former Malorussian dialect of the All-Russian language become the alien Ukrainian language, so threatening to Russian-speakers? Putin emphasized the early Soviet period, and particularly the 1920s, when Soviet authorities introduced a series of policies collectively known as коренизация [= korenizatsiya]. The word literally means something like “putting down roots,” but the official English translation of Putin’s essay glossed it as “localization.” In a nutshell, the Soviet government launched aggressive policies of affirmative action, systematically promoting languages other than Russian in schools, local administration, and public life. Soviet authorities hoped that a sharp break with the great-Russian chauvinism of the Romanovs would win popular support among non-Russians. In the long term, however, such policies probably strengthened particularist national feeling (Liber Reference Liber1991; Slezkine Reference Slezkine1994; Smith Reference Smith1999, 108–143; Martin Reference Martin2001; Hosking Reference Hosking2002; Mironov Reference Mironov2021).

Putin argued that “the localization policy undoubtedly played a major role in the development and consolidation of the Ukrainian culture, language and identity,” complaining that in Soviet Ukraine “Ukrainization was often imposed on those who did not see themselves as Ukrainians” (Putin Reference Putin2021). Several western historians concur, depicting Soviet nationalities policy as a turning point in the spread of Ukrainian national feeling (Martin Reference Martin2001, 90–95, 122; Hirsch Reference Hirsch2014, 130; Brown Reference Brown2009, 226–240). Unlike western historians, however, Putin emphasized the role of korenizatsiya in order to deny the legitimacy of the Ukrainian state. By depicting Ukrainian nationalism as a product of Soviet policy, and therefore as recent, he implied that Ukrainian nationalism lacks genuine historical roots (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2022). Putin argued that there “was no historical basis” for “the idea of Ukrainian people as a nation separate from the Russians” (Putin Reference Putin2021), and in a subsequent speech justifying the invasion shortly after it began, declared that “Soviet Ukraine is the result of the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called ‘Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine’,” a term clearly intended as pejorative and delegitimizing (Putin Reference Putin2022b).

Nevertheless, Putin elsewhere acknowledged that the “Ukrainian language” predated the Soviet period. In his sole admission that the historical relationship between Ukrainians and Russians has ever been anything other than warm and brotherly, Putin acknowledged as an injustice that Romanov laws had forbidden books written in Ukrainian. Putin admittedly made some excuses for his Romanov predecessors: imperial Russian authorities had been forced to act because “leaders of the Polish national movement” had sought “to exploit the ‘Ukrainian issue’,” and anyway belles lettres including “works of fiction, books of Ukrainian poetry and folk songs continued to be published.” Nevertheless, when conceding that “the Valuev Circular of 1863 and then the Ems Ukaz of 1876 … restricted the publication and importation of religious and socio-political literature in the Ukrainian language,” Putin acknowledged the existence of a “Ukrainian language” as early as 1863; that is, well before Lenin and korenizatsiya (Putin Reference Putin2021).

However Putin understands the emergence of Ukrainian distinctiveness, the assertionist claims in the second half of his essay differed considerably from the assertionist claims made in the first half. The Ukrainian language can only threaten Russian-speaking Ukrainians if it is a separate “language.” The lumper assertionism in Putin’s historical background gave way to splitter assertionism in Putin’s discussion of post-Soviet Ukraine.

While both halves of Putin’s essay rest upon normative isomorphism, the different assertionist stances have different implications for the territorial aspirations they theoretically legitimate. The second half of Putin’s article, positing irreconcilably different Ukrainian and Russian languages and thus irreconcilably different Ukrainian and Russian nations, justified through normative isomorphism the annexation of Russophone regions in Ukraine’s south-east. The triune concept propounded in first half of the article, by contrast, implicitly justified through normative isomorphism the annexation of the entire Ukraine.

Conclusion: Normative Isomorphism and War

This analysis of Putin’s Reference Putin2021 essay holds lessons about Putin as a politician, about the politics of the language/dialect dichotomy, and about normative isomorphism. These three issues, however, prove interrelated. Let us begin with the particular context of the 2022 Russian invasion and then move to more general conclusions.

By taking both sides of a language/dialect dispute in a single essay, Putin calls his own intellectual consistency into question. Does he believe in a separate Ukrainian “language” or not? A definitive explanation must inevitably remain elusive: outsiders are not privy to Putin’s inner thoughts. His ideas might simply be muddled. It seems a plausible speculation, however, that Putin, as a canny and opportunistic politician, was leaving his options open.

Putin’s Reference Putin2021 speech provides preemptive justification for diverse Russian policies. The lumper assertionism offered in the first half of the speech supports the triune national concept, which according to normative isomorphism would justify the Russian Federation’s annexation of the entire Ukrainian Republic. Had the Ukrainian army and/or state collapsed in the face of the Russian invasion, perhaps Putin would have attempted to annex the entire Ukraine up to the frontier with Hungary and Slovakia. As it turned out, of course, the Ukrainian army and Ukrainian state did not collapse: Ukrainian resistance proved tenacious and valiant, and the Russian annexation of Galicia and Transcarpathia is currently very difficult to imagine. Putin’s Reference Putin2021 speech, however, also provided a fallback position. The splitter assertionism in the second half justified the 30 September 2022 annexation of territories in Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia in south-eastern Ukraine, since those territories can credibly described as “Russian,” or at least “Russian-speaking.” The outcome of military action is always uncertain. Perhaps Putin planned for different possible contingencies?

The surprising phenomenon that Putin harnessed both lumper assertionism and splitter assertionism in support of expansionist foreign policy objectives suggests that the political valence of the language/dialect dichotomy is more complex than a naïve analysis might anticipate. Splitter assertionism is indeed associated with Ukrainian nationalism, lumper assertionism is indeed associated with Russian nationalism. Nevertheless, neither Ukrainian nor Russian nationalism is monolithic. The diverse arguments made in Putin’s Reference Putin2021 speech, with their intellectual consistencies, reflect different strands of Russophile Ukrainian thought, or, alternatively, different strands of nationalist thinking within Russia itself (Goble Reference Goble2016). Indeed, Putin may have argued both sides of the language/dialect debate not to shape Russophone nationalist sentiment in any particular direction, but to cater to it in its full diversity.

Any analysis of Putin’s speech, however, must move beyond the mere recognition that Putin, the dominant politician in the Russian Federation, invoked the language/dialect dichotomy from “political” motives. Scholars discussing a language/dialect dispute are generally quick to point out the political ramifications of any stance adopted by their opponents, apparently from the belief that considering the influence of “political factors” is inherently problematic. Acknowledging the political ramifications of one’s own stance, however, often proves more difficult. Being sensitive to the political stakes of both lumper assertionism and splitter assertionism alike may help move the conversation beyond the sterile accusation that one’s political opponents have acted from political motives.

The agnostic approach to language/dialect disputes starts with the initial assumption the language/dialect dichotomy is a genre of politics. It begins with an openly political analysis, disregarding as essentially irrelevant the linguistic facts that so delight philologists. Indeed, Putin’s speech, as an instance of political rhetoric invoking the language/dialect dichotomy, spectacularly illustrates the irrelevance of linguistic trivia. It opportunistically makes both the lumper and splitter case as his rhetorical requirements shifted. It also ignored linguistic trivia: neither as a lumper or splitter did Putin allude to any sound changes, semantic differences, or even vocabulary. While his case for lumper assertionism alluded to folk sayings and cultural heroes such as Gogol and Shevchenko, his case for splitter assertionism moved straight from linguistic assertions to national claims.

Putin’s essay also suggests that the political potency of the language/dialect argument rests on the ideology of normative isomorphism. Given how much this ideology has contributed to “war, ethnic cleansing and genocide” (Kamusella Reference Kamusella2022, 150), let us end by reminding ourselves that normative isomorphism is not a law of nature. In many parts of the world, national states exist without their citizens feeling the need to proclaim a unique “language.” Australians are generally happy to consider themselves speakers of “English,” despite a vigorous sense of Australian national distinctiveness. Similarly, most Argentines are happy to be speakers of “Spanish.” In other parts of the world, furthermore, national feeling transcends linguistic frontiers. Singapore, South Africa, and Switzerland all boast multilingual nationalisms. Canadian nationalism doubly contradicts normative isomorphism: not only is Canadian nationalism proudly multilingual, but the leading Canadian languages, “English” and “French,” are spoken in other states. Normative isomorphism is not universal even in its supposed heartland in Central and Eastern Europe. While Austrians have in recent years developed a strong sense of national distinctiveness, most are happy to be speakers of “German.”

Rejecting normative isomorphism would facilitate both debate and analysis of the political issues at stake in Ukraine. Linguistic diversity should not threaten the Ukrainian state, and Ukrainian citizens who speak Russian, or would like to, should be able to defend their linguistic rights without being accused of treason. Nor should linguistic similarity across a political frontier justify territorial claims: the existence of Russophone Ukrainian citizens should not on its own give the Russian Federation territorial claims. Instead of trying to rebut Putin on assertionist grounds, linguists would better spend their time trying to undermine the ubiquitous popularity of normative isomorphism.

As concerns the language/dialect dichotomy, finally, Putin’s speech illustrates the need for agnosticism. Agnosticism equally rejects both Russian lumper assertionism and Ukrainian splitter assertionism. Agnosticism rejects the language/dialect dichotomy in its entirety, and thus the dichotomy’s relevance to Ukrainian politics one way or the other. While the language/dialect dichotomy is a form of politics, it is not a helpful form of politics. The political stances that both Russians and Ukrainians have been articulating with reference to the language/dialect dichotomy would be better discussed directly, not through linguistic proxies. A sceptical attitude toward splitter assertionism, finally, need not imply sympathy toward the Russian invasion. The legitimacy of Ukrainian independence depends on the consent of the governed, and that consent need not rest on any particular linguistic taxonomy.

Disclosure

None.