The question of whether to have a second, third or fourth child (why not?) for the happy, married couple is not only a personal matter. Here the interests of society are affected: problems of the birth rate, the growth of the population, and maybe even, to put it clearly, the fate of the nation.

Izvestia, March 9, 1979One of the enduring paradoxes of Soviet power, at least as far as Soviet leaders were concerned, was the fact that they apparently controlled vast swathes of territory in Central Asia and yet seemed to have little influence over the actions of the people who lived there. Revolutionary beliefs that the distinction between nationalities and cultures would fade away were proved incorrect as the decades went by (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005). In much of Central Asia, loyalties of kin, clan, tribe, and ethnicity continued to take preference over loyalty to the Soviet Union as a whole, making it difficult for the government to fully implement socialist reforms. And by the 1970s, this problem looked set to become more significant because the proportion of people from this region was steadily increasing as a result of their high birth rates. By 1976, Brezhnev was urging the study of “aggravated” population problems as one of the major tasks of scientific study (Materialy XXV s’ezda CPSS 1976, 73).

The falling fertility of Slavs in contrast to the high fertility of the Central Asian peoples meant the latter would eventually dominate numerically, a trend that was said to threaten the very nation itself. Predictions showed that by 1989 ethnic Russians would become a minority in the USSR (RGAE 1975).Footnote 1 In this new world, labor supplies would be unbalanced between regions as the centrally planned economy had been designed to match population dynamics from decades before, and it would be precisely those people who were hardest to integrate who dominated the Union. Over time, reshaping the population through reproduction began to seem easier than addressing the economic and social challenges brought by demographic change. Government campaigns aimed to raise the birth rate among Slavs, while suppressing it among Central Asians (and to some extent the people of the Caucasus too). For elite social observers in Moscow, both fertile Central-Asian mothers and reluctant Slavic mothers thus became abstract groupings, whose lives had no significance beyond the categories themselves, which must be altered in size to protect the nation.

This article will examine the impact of this demographic change and Soviet leaders’ perception of it as a threat to the security and economic development of the Soviet state from the 1970s onwards. The article will interrogate the ways in which prejudice, economic challenges, and security concerns converged in late Soviet population policy and discourse. I argue that the government’s response failed to appreciate the structural and operational issues of state socialism, instead positioning economic problems as an inevitable result of the changing proportion of nationalities in the USSR. Rather than trying to resolve economic concerns, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union ultimately attempted to change the population itself, with fatal consequences for the economy and often for the relationship with local leaders too. The article will place demographic change in the context of the broader literature about the dissolution of the USSR; it further discusses how economic challenges went unresolved and how a lack of faith in the Soviet system among the intelligentsia undermined the legitimacy of the regime.

A number of studies have examined the social effects of changing Soviet fertility, but these have been mostly focused on gender and motherhood. Historians such as Bridger and Nakachi have explored pronatalist campaigns to boost childbearing, showing how these reinforced traditional gender roles (Bridger Reference Bridger and Kay2007; Nakachi Reference Nakachi2020; Rivkin-Fish Reference Rivkin-Fish2003; Attwood Reference Attwood1990; Desfosses Reference Desfosses and Desfosses1981; Nakachi Reference Nakachi, Solinger and Nakachi2016). Studies on the early Soviet Union have demonstrated the fundamental importance of demographic statistics to the formulation of ethnic identities (Abramson Reference Abramson, Kertzer and Arel2002; Cadiot Reference Cadiot2005; Shearer Reference Shearer2004; Martin Reference Martin2001). Scholars have also identified tensions between ideas of integration and the right to self-determination for nationalities, showing these goals existed simultaneously within Soviet government but were at odds (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005; Edgar Reference Edgar and Smith2014). In addition, place specific studies have emphasized the depth of the economic challenges facing certain republics, where the enormous diversity was poorly understood in Moscow (Bremmer and Taras Reference Bremmer and Taras1993). In areas like Turkmen Republic (Edgar Reference Edgar2004) or the Tajik Republic (Kalinovsky Reference Kalinovsky2018), the slow pace of economic development encouraged economists to give up on these nationalities and question their place in the Soviet Union.

In addition, literature examining the history of Soviet demography has begun to explore the role it played in the late-Soviet era. Toft (Reference Toft2014), for example, has argued for the primacy of the 1979 census in flaring ethnic tensions that are widely acknowledged to have contributed to the dissolution of the USSR. Leykin’s (Reference Leykin2019) research shows that in the Brezhnev era the economic determinism of early Soviet demography was replaced by a behavioral approach, in which influencing individual demographic behavior was seen as the key to resolving population issues. This attempt to influence behavior is key to the study presented here and will be examined in more detail throughout. Demographers have, of course, also written about the changing ethnic makeup of the USSR, providing detailed statistical analysis on which many of these studies are based (Anderson and Silver Reference Anderson and Silver1985, Reference Anderson and Silver1989; Coale, Anderson, and Harm Reference Coale, Anderson and Harm1979; Blum Reference Blum, Kustova and Toritskaya2005; Karabchuck, Kurno, and Selezneva Reference Karabchuck, Kurno and Selezneva2017; Andreev, Darskii, and Khar’kova Reference Andreev, Darskii and Khar’kova1993). This paper aims to build on this literature, using archival evidence to examine how policymakers in Moscow misdiagnosed the economic problems of the Soviet system as demographic problems. In doing so, they failed to appreciate the structural and operational issues of state socialism and sometimes aggravated tensions with local Republic leaders – both factors that ultimately undermined the stability of the USSR.

This article will first outline demographic change that took place over the twentieth century. It will then turn to consider why first demographers, then bureaucrats, and ultimately political leaders saw this as a looming crisis, showing that labor imbalances, prejudice, security concerns, and language issues were all involved. Following this, the government response – which consisted primarily of propaganda aimed at changing patterns of reproduction – will be discussed. Finally, I show how the government’s response placed blame for economic issues on the reproductive behavior of Central Asian peoples and, in doing so, angered many local leaders and other elite commentators, particularly in places where there were preexisting tensions.

Demographic Trends in the USSR

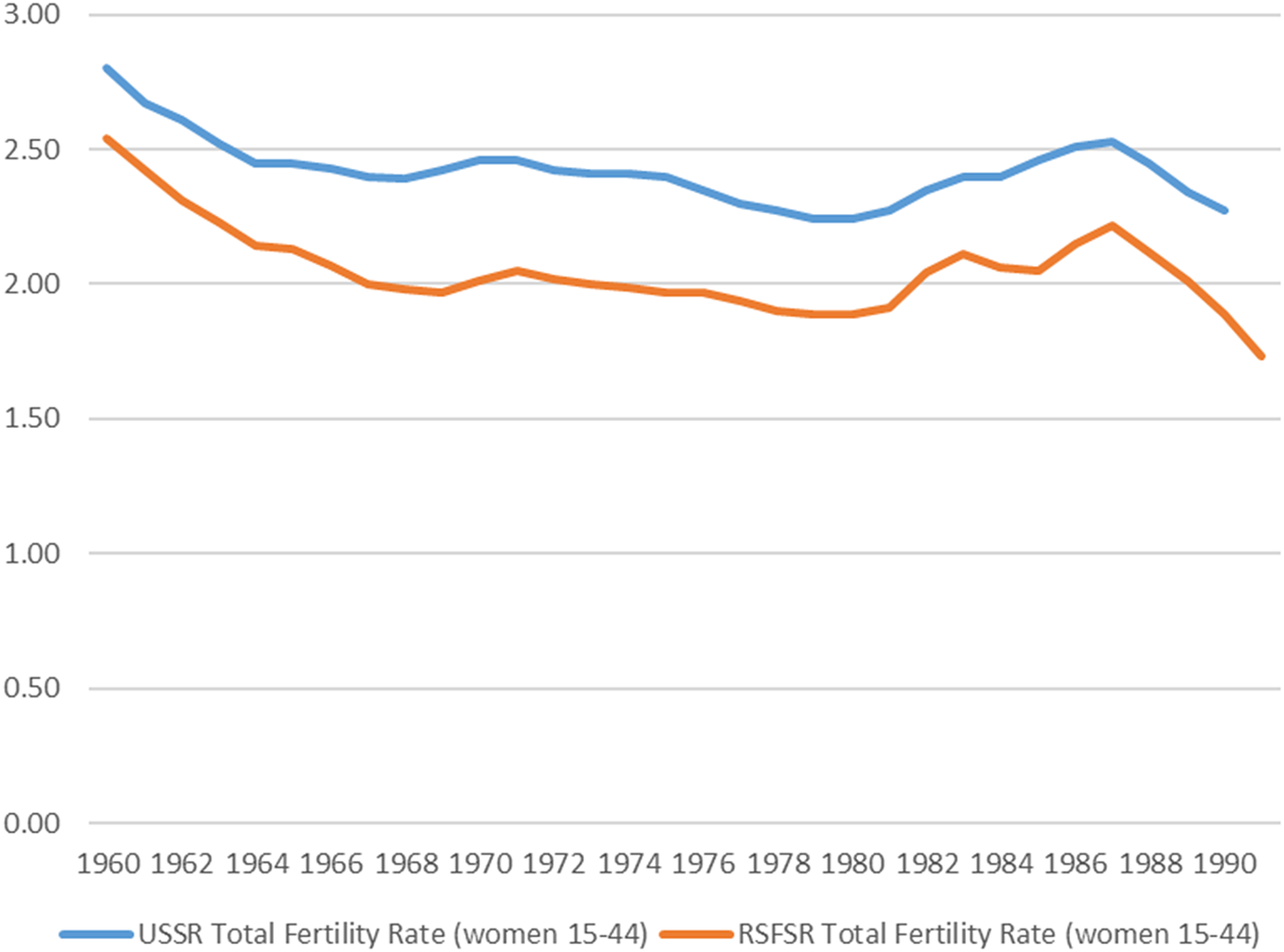

Like many countries, at the start of the twentieth century, the Russian empire had traditional, premodern patterns of birth and death where high numbers of children were born, many of whom died in infancy (Patterson Reference Patterson1995). With the advent of modern medicine, mortality rates began to fall rapidly, not only in Russia but across the developed world. The early Soviet state ran extensive public health campaigns to improve hygiene (Starks Reference Starks2009). Falling mortality was accompanied by falling fertility, as families needed fewer children to maintain the same family size, and the desirability of large families reduced in response to urbanization and changing lifestyles. The pace of this transition in reproductive practices varied from country to country. France, for example, experienced an unusually early decline in fertility in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Cole Reference Cole2000). In Britain, the transition began in the late nineteenth century (Soloway Reference Soloway2014). Russia, however, experienced a comparatively late and much more rapid transition; it took just fifty years at the start of the twentieth century for fertility rates to fall from an average of over seven births per woman to under three by 1950 (Zakharov Reference Zakharov2008). Levels continued to decrease: in 1940, the fertility rate in Russia was 4.25; by 1955, the average was 2.83; by the 1970s, it had fallen below the replacement level of 2.1 (David, Skilogianis, and Posadskaya-Vanderbeck Reference David, Skilogianis and Posadskaya-Vanderbeck1999, 230). The cohort of Russia women born in the 1960s were the first to give birth to fewer than 2.1 children on average, and fertility remained below replacement for most of the Brezhnev era (Frejka and Zakharov Reference Frejka and Zakharov2013) (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Graph showing the total fertility rates for the USSR and RSFSR combined for the years 1960–1990.

Source: Adapted from David et al. Reference David, Skilogianis and Posadskaya-Vanderbeck1999, 230–233.

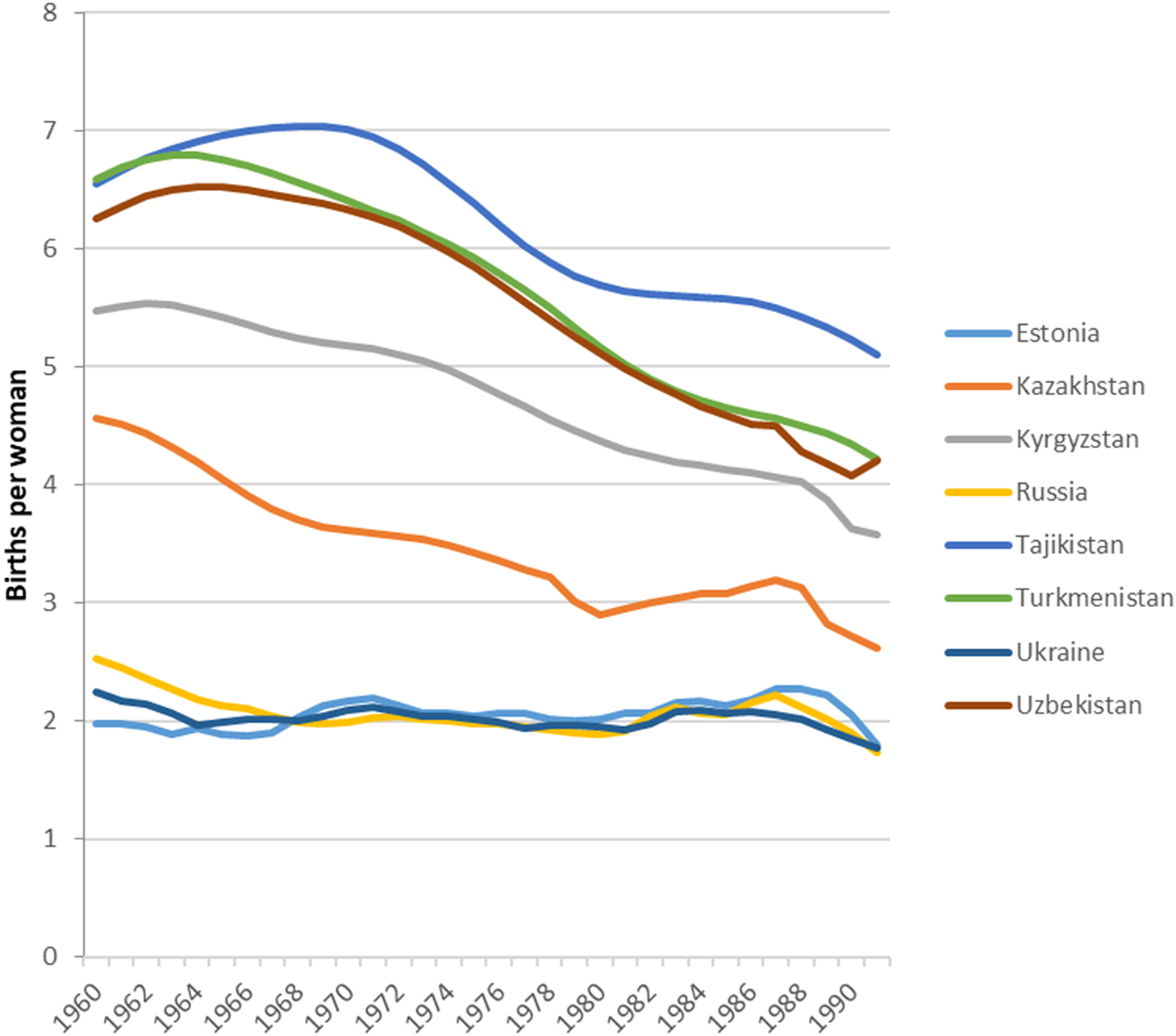

The Soviet Union as a whole, however, saw fertility decline much more gradually. This is because numbers masked the differences between ethnic groups within the USSR. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova all experienced similar declines in fertility. This was also true of the Baltic states, which had some of the lowest fertility rates in the entire country. The Azerbaijanian, Armenian, and Georgian Republics had slightly higher fertility, but the Central Asian Republics maintained fertility rates similar to pre-transition levels well into the 1970s. While Russians began to have fewer than two children in the early 1970s, Tajik women were giving birth to almost seven (see figure 2). In reality, there were significant demographic differences, not just between Central Asian Republics but also within them, as urban and rural regions saw wide variations in patterns of fertility and mortality (Buckley Reference Buckley1998). Nevertheless, in their reports, Soviet demographers tended to group republics by type of reproduction (RGAE 1976),Footnote 2 obscuring many of these differences for those in government who read the reports. One inevitable consequence of these fertility rates was the changing proportion of nationalities in the USSR. In 1959, those living in Russia accounted for 56.3% of the population. By 1989, this had reduced to 51.4%, barely a majority. In contrast, those from the five Muslim republics of Central Asia accounted no longer for 12.8% of the population but for 19.7% of it (Anderson and Silver Reference Anderson and Silver1989, 165).

Figure 2. Graph showing the total fertility rate by Soviet republic for the years 1960–1990.

Source: Blum Reference Blum, Kustova and Toritskaya2005; Goskomstat SSSR 1988.

Understanding Population Change – Elite Perceptions

Knowledge of the fact that differentiated birth rates were causing changes in the proportions of the nationalities in the USSR caused quite severe anxiety on the part of the government and demographers based in Moscow. Birth rates were so low in certain regions that, despite very high fertility in Central Asia, the Central Statistical Administration was privately predicting that by 1988 the overall number of newborns would be lower than the year before for the first time – and that this trend would continue (RGAE 1975).Footnote 3 In the specialist press, demographers called on the government to create “a social climate that will be conductive to a higher birth rate. To this end,” they wrote, “a vigorous campaign should be launched to propagandize the ideal Soviet family” (Ryabushkin quoted in Galetskaya, Voprosy Ekonomiki, Reference Galetskaya1975, 151). Demographers were not the only ones concerned. A 1971 report from Gosplan to the Council of Ministers recommended “influencing public opinion using the means of mass propaganda and education of a social, pedagogical and medical nature” (RGAE 1971, 42).Footnote 4 Why, exactly, were differentiated fertility rates so concerning to the government?

Anxiety about high birth rates in Central Asia and low Slavic birth rates can be explained in several ways. Firstly, prejudice and racism undoubtably existed against people from Central Asia who had different cultures and appearances than Russians, but written examples of ethnic slurs or open racism are rare in the archives. Instead, reports included veiled references to “social change” or wrote that it was problematic that the “most culturally developed regions” had the lowest birth rates (RGAE 1971, 41–42; GARF 1968, 32).Footnote 5 Letters by foreign ambassadors also sometimes note the distinctions drawn privately by Soviet politicians “between ‘the Russians’ and ‘the others’ in the USSR,” saying that they “regarded the Russians at the master race who controlled and should continue to control the USSR as a whole” (TNA 1971, 3).Footnote 6 Clearer evidence has been found elsewhere, such as Sahadeo’s (Reference Sahadeo2019) oral history study of Central Asian migrants in the Soviet Union. Controlling the USSR as a whole was a key concern for Russian political leaders in Moscow. Fear that the dominant position of ethnic Russians and Slavs within the USSR was being undermined was a clear motivation for discriminatory demographic policy. If Russians were no longer a majority, it was unclear whether they would continue to hold political power, something that became a great source of anxiety. Indeed, discussion of this issue was always tinged with prejudice, and it can be difficult, when looking at sources, to separate this from other concerns.

To write off concern simply as a matter of racism, however, would be to oversimplify the issues involved in changing population structure. The reasons for concern cited in documents also reveal a complex picture – forms of prejudice and legitimate economic concerns overlapped. In the Soviet centrally planned economy, uneven fertility meant large excesses of labor resources in some areas and severe shortages in others. Theoretically, workers could be sent where needed, but in practice this was difficult. Documents note that those from Central Asia and the Caucasus particularly resisted moving from their native republic, which, as Goskomtrud complained, made it more difficult to use their labor resources in regions of intensive development, particularly in the north and east of the country. According to Goskomtrud and Gosplan reports, workers from Central Asia and the Caucasus also mostly worked in light industry and tended to lack the skills needed to move to shortage areas (GARF 1979, 69).Footnote 7 The number of inflexible workers who could not be moved was growing excessively fast in certain areas. In others, low birth rates meant there was no ready supply of new labor. Sahadeo (Reference Sahadeo2019) shows Moscow and Leningrad offered sufficient opportunities to be attractive to migrants, but regions where labor was needed did not. In particular, the north and far east of the RFSFR appeared unattractive not just to the people of central Asia but to those from all republics. Climatic conditions were particularly harsh, and the regions tended to lack infrastructure such as nurseries and entertainment venues.Footnote 8 Government organizations such as Gosplan therefore perceived a high Central-Asian birth rate – which might otherwise have been welcomed in an economy hungry for labor – as unhelpful because the new generation could not be moved to the required areas.

The labor resources issue was further exacerbated by language differences. The data from the 1970 census found that only 14.5% of Uzbeks, 15.4% of Turkmens, and 15.4% of Tajiks fluently spoke Russian (ARAN 1971, 19–20).Footnote 9 This impeded the movement of excess of labor resources to shortage areas and also caused potential problems for the military. Fears were expressed in one 1977 article in journal Voprosy filosofii:

Such unfavourable demographic trends in our country as the drop in the birth rate, the halt in the growth of average life expectancy, the development of irrational migration patterns, the formation of disproportionate age and sex structures in the population in some regions and the systematic rise in the divorce rate all impact the Soviet military. These demographic trends manifest themselves in the size, geographic distribution and national make-up of cohorts of conscripts … Efforts must be made to surmount and offset the consequences of the country’s unfavourable demographic situation and to present them from affecting the combat capability of readiness of the Soviet military. (Sorokin Reference Sorokin1977, 11)

Though the “national make-up of cohorts of conscripts” should not have mattered, in practice it did. Scholars such as Toft have shown that, during the war with Afghanistan, the low level of Russian spoken meant Central Asian conscripts often did not understand instructions and had to communicate with their commander via an interpreter (Toft Reference Toft2014, 195). “The language barrier makes it harder to use these contingents in the military,” reports warned in the early 1970s (ARAN 1971, 19).Footnote 10

Cultural considerations and suspicions also came into play because the new ethnic mix increased the proportion of conscripts from the most politically alienated periphery regions (Rakowska-Harmstone Reference Rakowska-Harmstone, Hajda and Beissinger1990). The Soviet Union had a long history of mistrust of Central Asian recruits, despite their forming part of the military since the start of the Soviet Union. They were initially excluded from conscription in the Second World War along with others deemed “class enemies” by the Party (Feferman Reference Feferman, Bougarel, Branche and Drieu2017). Suspicions were heightened in the late-Soviet period by the conflict in Afghanistan. The Soviet leadership worried that the emergence of Islamism via the Iranian revolution and the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan represented a competing spiritual and moral authority to which the people of Central Asia would be drawn. In Politburo discussions from March 1979, Alexei Kosygin, Chairman of the Council of Ministers, voiced these concerns, asking “With whom will it be necessary for us to fight in the event it becomes necessary to deploy troops – who will it be that rises against the present leadership of Afghanistan? They are all Mohammedans, people of one belief, and their faith is sufficiently strong that they can close ranks on that basis” (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2001: 139).Footnote 11 Because Central Asians had historically been Muslims, even if many did not actively practice by the 1970s, leaders feared they would feel loyalties to these places and be encouraged to rise up against the Soviet leaders in Moscow or defect to join sides with the Mujahedeen, something that was very occasionally documented, though far from commonplace (Suny Reference Suny1998, 440–441; Toft Reference Toft2014). Language barriers, combined with highly sensitive conflicts, therefore caused issues for industry and the military. These barriers, though sometimes imagined more strongly than they existed in practice, were real and did present problems for the Soviet government. It encouraged a situation where central government saw Central Asian peoples as unreliable, un-Soviet, and inferior as an economic and military resource.

This perception was important because it affected the way the government tried to address economic and military issues. Rather than aiming to change the skills of the population, the government placed primary emphasis on changing patterns of reproduction. They sought to remedy the situation by changing the population itself. Family and cultural factors, particularly in the 1980s, came to be seen as fixed, meaning the government felt there was no point in trying to develop and upskill Central Asian Republics because their populations would continue to refuse to be drawn into the right areas of industry (Kalinovsky Reference Kalinovsky2018, 89–90). Many people from Central Asian Republics certainly did not want to move to areas where they faced prejudice and lack of support. Government attempts to assimilate them into the population were also perceived negatively because rather than incorporating the culture of these peoples, campaigns often sought to erase it (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005; Edgar Reference Edgar and Smith2014). Nevertheless, the government did little to really address these issues or provide effective incentives and support for career change. Scholars of Tajikistan, in particular, have noted that planners and academics in Moscow often had little understanding of the culture of different Republics in Central Asia. When early attempts to develop industry in Tajikistan failed, the Soviet system was too inflexible to adapt to the needs of the population to resolve economic challenges (Kalinovsky Reference Kalinovsky2018, 63–90; Yusufjonova-Abman Reference Yusufjonova-Abman and Ilic2018).

From Panic to Propaganda – The Soviet Government Response

Of the many issues facing the government, demography was initially quite low down the agenda. In the 1960s, demographers wrote at length about emerging problems but struggled to attract ministers’ attention (Elizarov Reference Elizarov2017; Leykin Reference Leykin2019; Vishnevsky Reference Vishnevskii1996). Gradually, as problems intensified, ministers began to take notice, and, by the late 1970s, the government in Moscow was determined to change differential fertility through policy. In 1978, Kosygin wrote to Goskomtrud, Gosplan, the Trades Union Council, the Academy of Sciences, and the Ministries of Law, Health, and Finance, asking them to reconsider the child and maternal benefits set up by the 1944 Family Law and create fresh proposals (GARF 1977–1981).Footnote 12 A fertility working group was established, and written proposals were circulated between the above agencies and the Party Central Committee (GARF 1976–1980).Footnote 13 Proposals on raising fertility recommended all kind of practical changes. For example, among the changes recommended in 1979 were increased benefits, better preschools, increasing living standards for those with children, better housing, increased maternity leave, banning women from dangerous physical labor, improved nursery food, increased leave for mothers with sick children, commissioning studies of infertility, producing more children’s shoes, and many more suggestions too (GARF 1976–1980).Footnote 14 Reports even included a recommendation for “the widespread production and promotion of modern contraceptive methods” due to the problem of medical infertility that was sometimes caused by repeat abortions (GARF 1976–1980),Footnote 15 an issue frequently noted by specialists in the Brezhnev era (ARAN 1966).Footnote 16 What is noticeable, however, is that most of these ideas were never realized, particularly where they were complex, costly, or required improved or increased production. Propaganda on the other hand was relatively cheap, the political system was well set up to implement it, and the size and intensity of a campaign could be increased very quickly. Accordingly, propaganda became the main method by which the Soviet government attempted to rectify fertility issues. Attwood (Reference Attwood1990, 7) highlights the fact that rising living standards had not prevented birth rates from falling, and this concerned planners, making them skeptical of the effectiveness of increased welfare, thus further encouraging a propaganda approach.

The working group on fertility set out extensive plans to change public opinion. Goskino and Gosteleradio were told “to extend the production of documentary and artistic films … on the problems of family life … preparing young people psychologically for family life.” The Ministry of Culture was told to run lectures that would prepare young people for their roles as mothers and fathers. The Academy of Pedagogical Science USSR was “to systematically put out propaganda on the experience of bringing up a family via the journal Family and school” (GARF 1976–1980, 93).Footnote 17 This was in addition to recommending propaganda in print, visual forms, and via the health and medical agencies. Any agency that could conceivably influence public opinion was required to do so. Sex education classes began in schools in the mid-1980s, encouraging traditional gender roles. It was these distinct predetermined roles that publications such as Nedelya (no. 3, 1978) argued were being rapidly lost to the detriment of society (Attwood Reference Attwood1990; Bridger Reference Bridger and Kay2007; Zdravomyslova and Temkin Reference Zdravomyslova and Temkin2013; Desfosses Reference Desfosses and Desfosses1981). As regular contributors to newspapers on the subject of fertility, demographers and population experts were also included in these requirements.

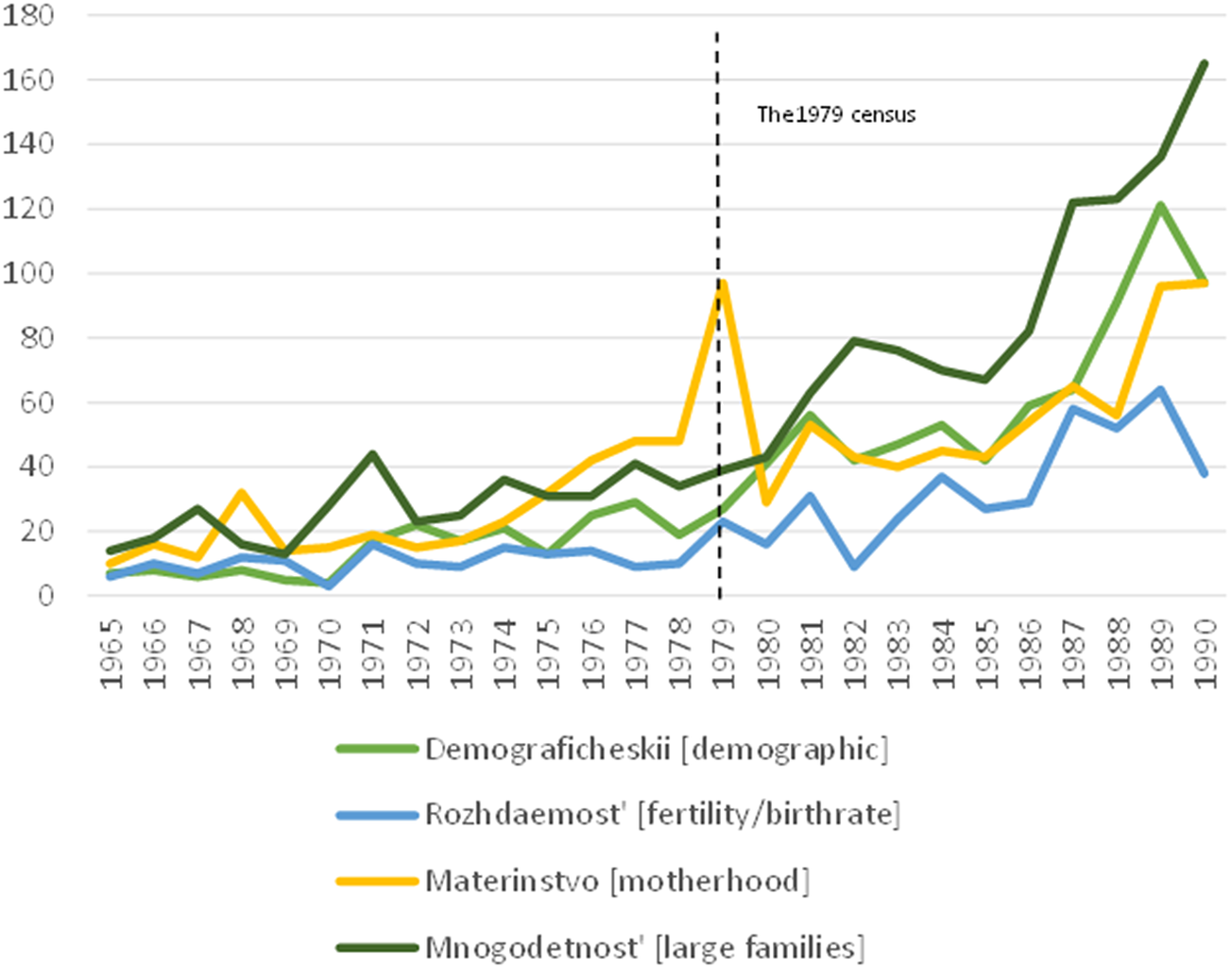

The 1979 census was crucial to this moment in history because it intensified the debate by highlighting the changing proportion of nationalities in the USSR. Results of the census were largely unpublished until perestroika; even then the data was limited to Republic rather than specific ethnic group (Anderson and Silver Reference Anderson and Silver1989). Evidence suggests the campaign to change fertility levels intensified sharply once the results of the census became apparent to experts and politicians. Between 1970 and 1979, the population of ethnic Russians was increasing by an average of 1.3% per year. Meanwhile, ethnic Tadzhiks were growing at 4%, Azerbaijanians at 3.6%, and Turkmens at 3.8% (Anderson and Silver Reference Anderson and Silver1989, 609–612). By 1989, ethnic Russians were predicted to be a minority in the USSR. This knowledge intensified the pressure, and existing propaganda was quickly stepped up. Figure 3 shows the frequency of terms relating to childbearing and fertility published in popular Soviet newspapers, demonstrating how discussion in the media of topics related to the campaign increased over the period as the demographic issues received more and more attention.

Figure 3. Frequency of Terms in Newspapers Pravda and Izvestia, 1965–1990. Data compiled by author from newspaper archives.

This propaganda campaign aimed to even out fertility rates by encouraging births in the European Republics and discouraging them in Central Asia and to a lesser extent in the Caucasus. The Communist Party had aimed at creating an ideal Soviet family since the revolution. Early Bolsheviks sought to break the bonds of the patriarchal family structure, while Stalin’s focus on strict morality with as many children as possible went some way to reversing this (Goldman Reference Goldman1993). Khrushchev’s family law sought to create two types of Soviet family – those with and without fathers – after a generation of men was lost to World War II (Nakachi Reference Nakachi2020). Brezhnev-era attempts to mold the Soviet family were therefore the latest in a long series of cultural and demographic visions for the family. By the Brezhnev era, the vast majority of demographers working with central government agreed that the ideal Soviet family was the three-child family. If families all had three children, demographers argued, then the population would grow at a steady, economically advantageous rate, while proportions of certain nationalities would remain constant, thus maintaining the status quo in the USSR. How to achieve this goal was the subject of much debate between demographers and policymakers (GARF 1971; ARAN 1968).Footnote 18

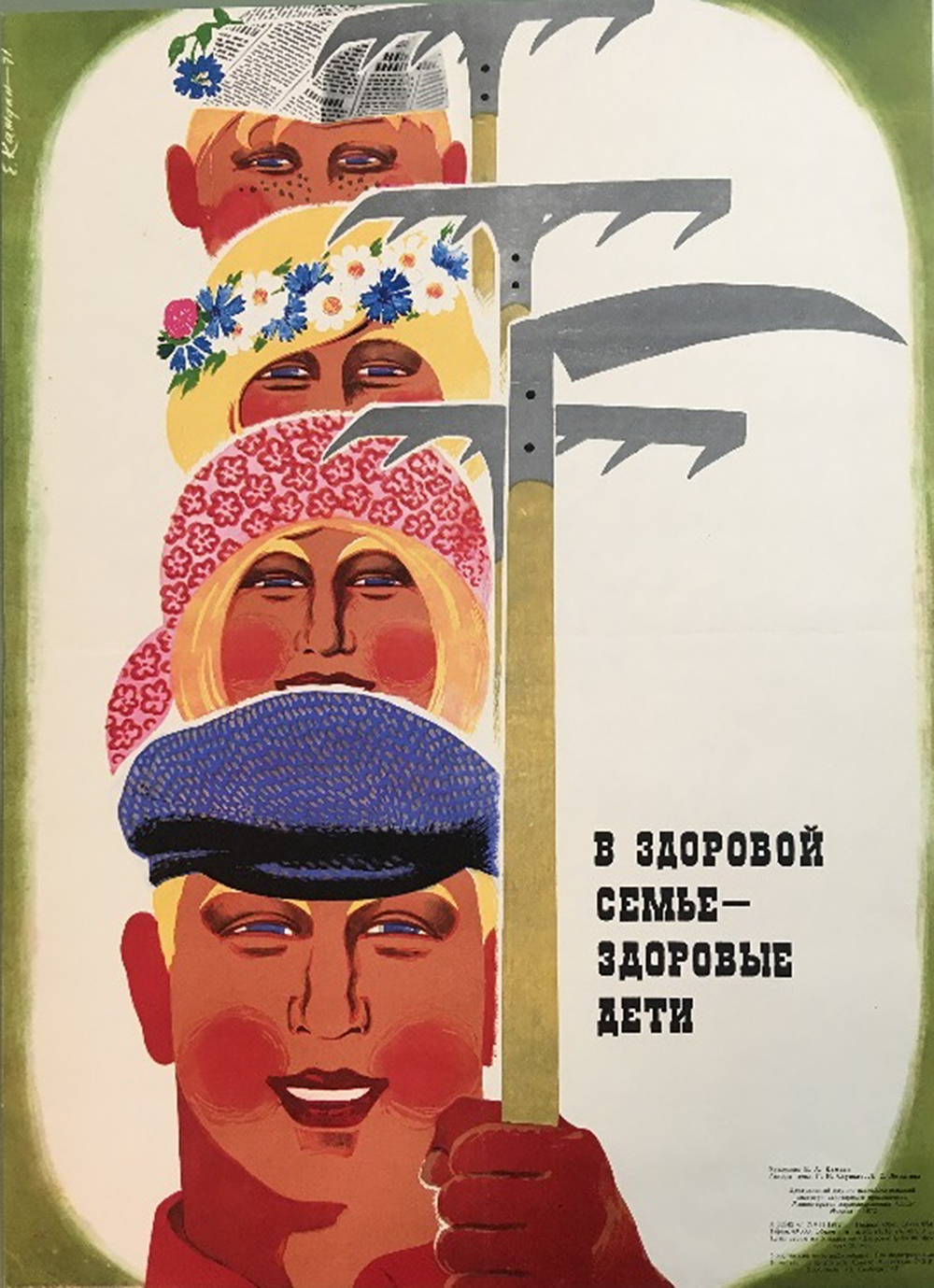

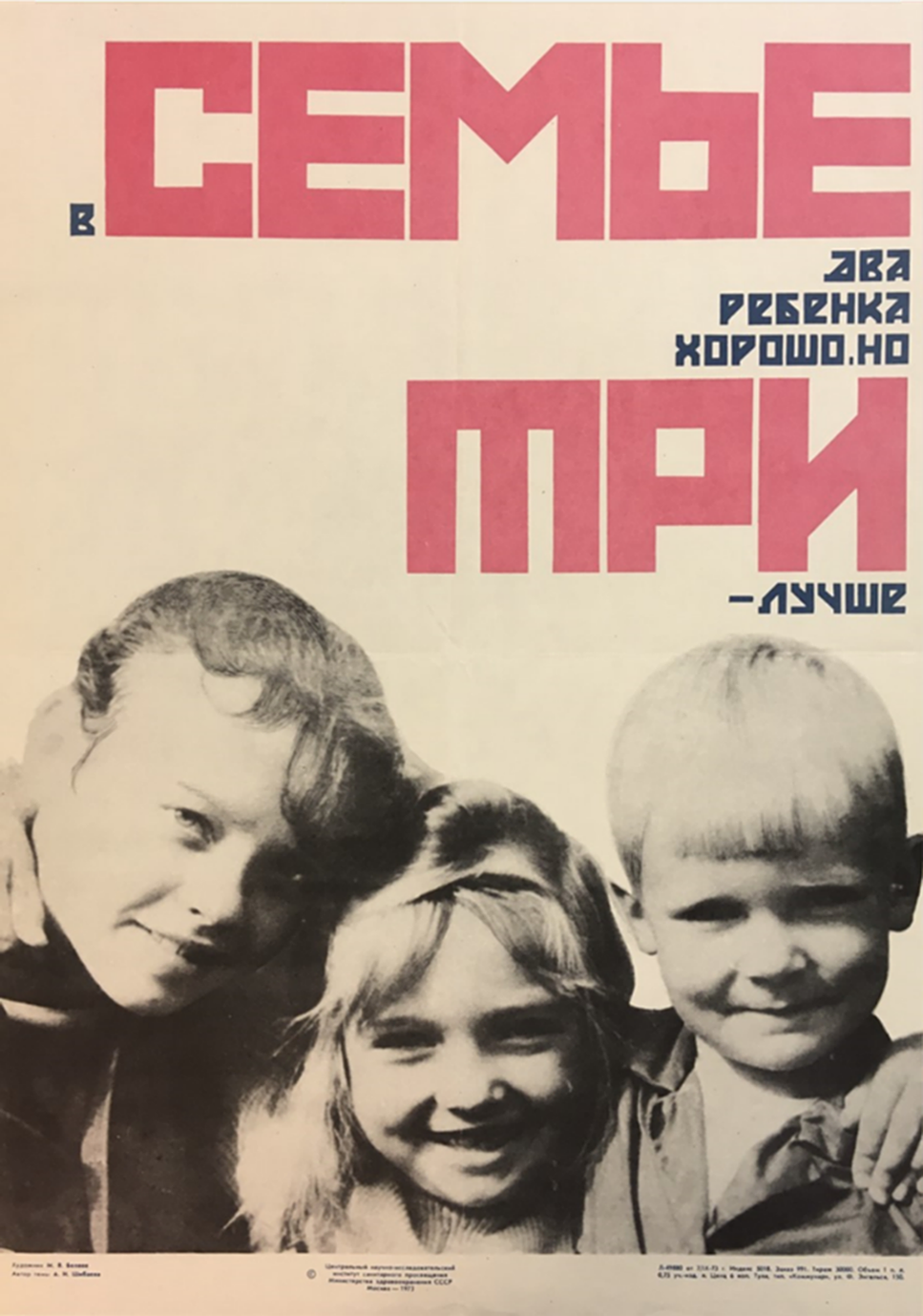

Three children was not seen as more desirable that four, but it was more realistic for Slavic women who were then typically only having one or two children (Desfosses Reference Desfosses and Desfosses1981). Demographer Boris Urlanis referred to this as the number that “satisfied the interests of society on the one hand, and the interests of parents on the other” (Literaturnaya gazeta, September 27, Reference Urlanis1972, 13). Though women in all Republics were meant to have three children, in practice, most propaganda in this area focused on inhabitants of European Republics either explicitly or implicitly. Posters encouraging families to have three children appeared. These posters warned of the dangers of small families and pushed the Soviet ideal of a multi-child family. Posters featured pictures of blond, Slavic children, implying that the ideal Soviet family was, in fact, ethnically specific (see figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. “In a healthy family there are healthy children.” Ministry of Health USSR, 1972 poster. Image courtesy of the Russian State Library.

Figure 5. “Two children is good but three is better.” Ministry of Health USSR, 1973 poster. Image courtesy of the Russian State Library.

Articles about the three-child family in the national press echoed this message of an ethnically specific ideal Soviet family. Articles consistently discussed the third child being an additional child, rather than a number at which to cease childbearing; in many cases, Central Asian families were simply excluded from this discourse. Literaturnaya gazeta spoke of fining families “who do not produce a second child within three years of the first,” asking “perhaps that would work?” (Alemaskin, Literaturnaya gazeta, February 14, Reference Alemaskin1973, 11). A typical article entitled “How Many Children to Have” in Izvestia from 1979 told readers:

In a big family it is easier to overcome troubles. The older children help the younger ones, they grow, as a rule, into more responsible and independent people, while an only child most often becomes an egotist. (Kalyuzhnaya, March 9, Reference Kalyuzhnaya1979, 8)

Parents were warned that childbearing was not simply for their own benefit but that the very future of their nation depended on this.

Indeed, the question of whether to have a second, third of fourth child (why not?) for happy, married couple is not only a personal matter. Here the interests of society are affected, problems of the birth rate, the growth of the population and maybe even, to put it clearly, the fate of the nation. (Kalyuzhnaya, March 9, Reference Kalyuzhnaya1979, 8)

Missing from any of these articles was an acknowledgement that Central Asian families already had many children, or any kind of encouragement to be more like those from the Muslim Republics. Articles never asked, for example, what Central Asia was doing right that other republics could learn from. Instead, high birth rates in Central Asia were also portrayed negatively.

The discussion of high Central Asian birth rates was more subtle than that of low Slavic ones. Suppression of fertility rates was a delicate topic, and so the issue was usually discussed either in terms either of health or of female emancipation and participation in the labor force. “Every effort,” one article read, “should be made to promote vocational education for women in the Central Asian Republics and to involve them in social production” (Galetskaya, Voprosy ekonomiki, 1975, 150). There were different motivations for encouraging Central Asian women’s involvement in the public sphere, but discussions by the population experts who were driving policy in Moscow showed that, for them, the primary purpose was to bring down the very high birth rates that characterized the region (ARAN 1971, 6–38)Footnote 19.

From a health perspective, articles discouraging births in Central Asia often argued that large families were dangerous for women’s health. Izvestia ran discussion pieces with headlines such as “The Large Family Through Doctor’s Eyes” (Dimov, Izvestia, February 28, Reference Dimov1987, 2).Footnote 20 In this particular piece, S. U. Sultanova, Vice-Chairman of the Uzbek Republic Council of Ministers, was interviewed, and he bemoaned the high fertility rate because of its effects on women’s health in the Republic. “Unfortunately,” he told readers, “we have not yet overcome the prevailing Eastern attitude that women are the active propagators of the species, which restricts their social statis and limits their opportunities to raise healthy children in the spirit of modern-day requirements.” In the Western Republics, being a propagator of the species was said to be a women’s natural role, and large families, allegedly, functioned better than small ones. In Central Asia, however, large families were shown as backward and “Eastern.” Rather than achieving progress, their fertility was said to be halting progress and development.

Of course, different motivations existed for promoting and discouraging births and those pointing to the adverse effects on women’s health were not wrong – bearing seven or eight children does indeed place significant stress on a woman’s body. Yet at the same time, Bridger shows that 1970s magazines aimed at rural Slavic women made heroine mothers (those with ten children) the focus of “sustained propaganda.” In these articles, which used examples of Ukrainian heroine mothers, no mention was made of the perceived health risks so often raised during discussions of Central Asian fertility levels. Nor did the concern – expressed elsewhere – that “the raising of a large number of children inhibits a rise in the cultural level of mothers of large families” (Kvasha Reference Kvasha and Volkov1970, 39) seem to apply to Slavic mothers. Central Asian women also allegedly needed to be drawn into the workforce, despite the excess labor resources already present in the region. So many of the concerns publicly expressed for the women of Central Asia seemed only to apply when they aligned with broader political goals. Reproductive labor was valuable to political leaders only when performed by “true members” of the nation.

By the start of the 1980s, propaganda campaigns were well underway, but the debate around demographic issues intensified significantly during glasnost’. By this time, a common angle for media publications was to focus on the very poor child and maternal health in Central Asia as well as the high rates of infant mortality there (something now permitted due to the reduction in censorship). Chauvinistic and nationalistic tendencies were sometimes mobilized by individuals to further their own aims and did not always represent the views of the government or professional groups to which they belonged. Nevertheless, the volume of such articles meant they became a significant part of the discourse on problems within Central Asia. Discussions tended to blame local culture and corruption, often implying people from these republics were too irresponsible to have large families. As the Republic with the highest infant mortality rate, Turkmenia was the focus of much of this criticism. For example, one 1990 article described how a state of “despotic oppression” existed in Turkmenia that caused the low standards of living and malnourishment leading to infant deaths.

The head of a farm in Turkmenia can say without hesitation how many livestock he has, how many of them died last year or last month, and what diseased they died of. But don’t bother to ask him how many children died on his collective farm in the same period and why. (Moskovskiye novosti, April 8, Reference Velsapar1990, 7)

According to the author, the “disunited tribal structure” and “large size of Turkmenian families,” which served to “inhibit the growth of social activism,” were to blame. Such articles were commonplace: “The family is big, but can one rejoice when there is no certainty the child will live and be healthy?,” Literaturnaya Gazeta asked its readers in relation to Central Asia (January 27, 1988, 12). Meanwhile, Komsomolskaya Pravda (April 25, 1990, 2) described the terrible conditions, alleging that men in Turkmenia would not give their wives enough to eat such that their babies died of malnourishment. Articles all urged better contraception for these regions as part of the solution. The economic deprivation and the lack of medical infrastructure, which lead to malnutrition and infant mortality, was therefore misdiagnosed as a population problem of overly large families and backward culture. Central Asian people themselves were blamed for their economic problems, absolving the Soviet government of any responsibility for the issue.

It was not only journalists who alleged that corruption was causing infant mortality but politicians too. Izvestia’s claims in 1986 (April 10, Reference Kuleshov1986, 2) that no nurseries, hospitals, or maternity clinics were being built because money was swallowed by corruption were echoed more and more strongly by leaders in Moscow. At the 19th Soviet Party Conference in June 1988, Minister for Health Yevgeniy Ivanovich Chazov told those assembled:

The Uzbek writer Sharif Rashidov wrote about happy children of a blossoming republic, but the leader of the Communist Party of Uzbekistan, Sh. Rashidov, did exactly nothing for saving the thirty-three thousand children who died every year not surviving up to one year of age. They squandered and embezzled milliards of rubles in the republic, but 46 percent of the hospitals were accommodated in buildings which did not answer minimum sanitary hygienic demands. (Chazov cited in Lane Reference Lane1990, 353)

The volume and frank nature of these criticisms meant that local elites – both politicians and administrative leaders like those running the healthcare system in the Republics – were only too aware of the accusations levelled at them in the media and at Party meetings, and this could hardly fail to aggravate relations. For example, Sadiniso Hakimova, Director of the Tajik SSR Ministry of Health Research Institute for the Protection of Mothers and Children, claimed she had long raised concern about infant mortality and poor health, only to be ignored by Soviet leaders in both the Republic and in Moscow (Hakimova, Reference Hakimova1998). If Hakimova is to be believed, then the sudden perestroika era’s apparent concern for infant health was nothing more than a cover story for years of inaction.

It is important to note that approval of birth control itself did not necessarily fall along ethnic lines. Hakimova, for example, was a strong proponent of birth control on the basis of women’s reproductive rights and health. But she did not fear, as did many in Moscow, that Tajiks were becoming too large a proportion of the population. Her goal was not to reduce family sizes but to provide choice, health, and agency. Different groups of people supported birth control for different reasons in what might otherwise seem an unlikely alliance of opinion, and this tendency has been noted too in larger global debates, which led to the spread of contraception worldwide in this period (Connelly Reference Connelly2008; Bashford Reference Bashford2014; Cooper Reference Cooper2017). Such debates drew on themes of development, living standards, food production, and religion, as much as they did on reproductive rights (Hartmann and Unger Reference Hartmann and Unger2014).

By blaming Central Asian Culture, even though no one single culture existed, Soviet leaders washed their hands of the economic issues of state socialism and positioned those from Central Asia as inherently corrupt and backward – features leaders saw as fixed. By doing so, Moscow was absolved of any responsibility because allegedly problems stemmed from the culture of these people, in which the Soviet system played no part. Even infant deaths were said to be the result of overly large families and corrupt officials. If these trends were inherent, then changing the population itself appeared to be the only way forward.

Demographic Policy Inflames Tensions

Discussion of demography in the media played into larger narratives in the 1980s, which alleged that the titular nationalities received preferential treatment over the Russian Federated Republic. By the early 1980s, allegations, which previously had only been mutterings, began to appear openly in the press, claiming that the Republics received preferential treatment because their leaders held the government to ransom. An ethnic “old boy network” was said to exist, to the detriment of ethnic Russians. The response these claims drew varied by Republic, and evidence suggests the backlash was strongest in places where local leaders already had a tense relationship with Moscow, such as Uzbekistan, where scholars have noted the significant animosity produced by the cotton affair (Cucciolla Reference Cucciolla2017). As both Republic leaders and the technical elite became increasingly disillusioned with the inability of the Soviet regime to manage problems (Suny Reference Suny1993, 126), they made their discontent with the demographic discourse known. Not only did infrastructure and economic issues go unresolved, but the Central Asian ways of life were now being regularly attacked.

Population issues in the late-Soviet period were studied throughout the Soviet Union by demographers and other experts. However, though lively debates took place within the regions and Republics, these seem to have had little impact on Moscow in this era; rather, meeting records from the Central Statistical Administration, policy proposals from Gosplan, and reports by the USSR Academy of Sciences tend to cite the same few names time and again. Discussions by Tajik economists, for example, tended to focus on how to draw the Tajik people into industry and raise their standard of living, while planners from Moscow focused primarily on moving the population itself to labor shortage areas in Siberia and the north (Kalinovsky Reference Kalinovsky2016, 596). When this failed, changing fertility became the primary concern in Moscow. But even within this “elite” cohort of Moscow demographers, there was disagreement. Soviet demographic literature at the time demonstrated consensus on two counts: firstly, the need for policy change; and secondly, the need to influence population growth and reduce differential fertility to achieve a three-child average, but there was significant disagreement between experts on what, precisely, the new policy should entail (Heer Reference Heer and Desfosses1981). Direct policy to limit population growth in Central Asia was highly controversial because of the obvious discrimination it entailed (Weber and Goodman Reference Weber and Goodman1981). Despite this, many scholars and planners began to argue strongly that the peripheral republics enjoyed special privileges, and, with the rapid population growth in Central Asia, this was becoming unsustainable. Such statements became a crucial part of the discourse about Central Asia population growth.

A particularly good example of this thinking is an article published in Sovetskaya gosudarstvo i pravda in 1982 entitled “The Demographic Policy of Soviet Union,” written by well-known demographers Galina Litvinova and Boris Urlanis. They called for the supposed imbalance of power between the Republics to be corrected and stated that, before 1917, many peoples of Asia were suffering depopulation, but that the introduction of the Soviet system and privileged treatment they received meant this situation was quickly reversed. They continued:

Even though the demographic situation in the USSR has altered sharply, the existing system of allocation budgetary resources, the policy of purchase prices, which affects the level of material security of the rural population and others, continues to remain privileged for the peripheral Republics and areas, although it is the central regions, the Non-Black Earth-Zone above all, which now needs such privileges more. (Urlanis and Litvinova, Reference Urlanis and Litvinova1982, 39)

The article flatly stated the that the 1944 family law that was aimed at “the maximum encouragement of large families” no longer made sense in the context of the new demographic reality. Women should not be receiving heroine mother medals, nor, they wrote, had the medals ever been particularly effective. The authors claimed that A) collective farms in Turkmen Republic each had several nurseries and kindergartens while parents in farms of other Republics were unable to find childcare and that B) Russian children faced an educational disadvantage.

Taxation, pricing policy, and wages were another bugbear:

In 1970 there were 11.5 hectares of arable land per able-bodied collective farmer in the RSFSR, while there were only 1.6 in the Uzbek SSR but incomes per collective farmer in the latter were 33% higher than in the RSFSR. (1982, 40)

The authors wrote that

For decades, taxation policy has been such that the greatest taxation privileges have been given to the peripheral areas of the country. As for budgetary policy, during all the years in which the Soviet State has existed, the RSFSR not only never enjoyed a subsidy from the All-Union budget like several other Republics, but the Republic’s budget has received one of the lowest rates of return from turnover tax — the basic form of budgetary income. (1982, 42)

Crucially, perceptions of budgetary fairness were linked with demographic change:

The All-Union censuses of 1970 and 1979 demonstrate a growth in the proportion of indigenous nationality in the majority of the Union and Autonomous Republics as well as a diminution in the proportion of such people living outside the boundaries of their Republics. One of the reasons for this consists in the fact that privileges are preserved in the Republics for the social advance of representatives of indigenous nationalities. This was justifiable in the first years after the Great October but demands to be changed under today’s conditions. (1982, 44)

This article was one of the most clear and open calls for a redress of the balance in the press, but others echoed its sentiments.

The perception of unfairness became linked to demographic issues because of the increase in the proportion of the population from Central Asian Republics and the Caucasus. As pronatalist policies were discussed, the key issue became whether any increased financial benefits should go to these Republics also. Who should bear the burden of the natural increase in nationalities from Central Asia and the Caucasus, society asked itself. If benefits were paid monthly for each child, then regions where five children were still common would receive the lion’s share of the welfare payments, which would, in effect, be subsidized by Republics with lower fertility rates. If welfare was differentiated by ethnic group or region, however, these groups were likely to protest and claim discrimination, upsetting the carefully managed balance of power. As a result, the government delayed the issue repeatedly while it debated what to do.

In 1981, a new set of pronatalist measures were finally announced. They raised benefits for the birth of each child and sought a compromise solution with regards to nationality. Lump sum benefits were introduced of 50 rubles for the first child and 100 rubles for the second and third (Selezneva Reference Selezneva2016). This benefit was not differentiated, but some were. Particular regions of Russia in the north and east were given higher benefits: residents in Vologda, Murmansk, Archangel, and other places were awarded 50 rubles a month in child benefit while all other areas of the USSR received 35 rubles. In addition, the rollout of the benefit was differentiated; though they eventually received the same amount, increased benefits were rolled out to Russia and the European Republics a year earlier than the Caucasus or Central Asia (Juviler Reference Juviler, Morton and Stuart1984, 101). Juviler (Reference Juviler, Morton and Stuart1984, 101) has noted that, by introducing the lump sum grant, small families still benefited, and this balanced the proportion of money going to each Republic more evenly.

Despite only slight differentiation in policy – the effect of which disappeared by the time benefits had been raised for all regions – those in Central Asia felt that government had acted in a discriminatory way (Nakachi Reference Nakachi, Solinger and Nakachi2016, 24), something that was encouraged by the frequent accusations in the press. It is true that local elites often used their bargaining power based on their rights as a nation to negotiate advantages for their people in exchange for cooperation with Moscow (Hirsch Reference Hirsch2005, 314–319; Suny Reference Suny1993, 120–127). Some scholars, such as Hosking (Reference Hosking2006), have gone so far as to argue Russians were in fact the victims of the system of Republics. Central Asian Republics did receive subsidies, but they were also by far the poorest areas and had the lowest standard of living. In their eyes, subsidies did not do nearly enough to make them equal, let alone give them a concrete advantage. Central Asia was thus discussed in elite Russian discourse as both incredibly prosperous and in a state of total turmoil – depending on who stood to gain from the diagnosis. If welfare payments were at stake, Central Asia was already said to be greedily taking too much. But when blame was being apportioned for poor health and mortality, it was the high fertility of women and selfish culture of local elites that was to blame.

As glasnost’ opened up what complaints could be made publicly, both leaders and technical elites from Central Asian Republics began to make their discontent with the discourse known. and this effect was most pronounced in the Republics of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. In Turkmenistan, for example, deputies of the Republic’s Supreme Soviet pronounced attempts to highlight problems of large families and infant mortality as “slander” (Voshchanov and Bushev, Komsomolskaya Pravda, April 25, 1990, 2). In 1989, the Second Congress of the USSR People’s Deputies saw a scathing attack from Ubaidullayeva, the Deputy Director of the Uzbek Republic Academy of Science, Institute of Economics in Tashkent. She complained that previous speeches had disrespected the Republic’s women by implying large families were to blame for the Republic’s economic problems. She argued that it was the years of stagnation and command administrative system that was to blame and not the birth rate. “We women and mothers of Uzbekistan demand that Deputy Bronshtein make a public apology to us,” she finished (Izvestia, December 18, 1989, 2–5). The “undesirability,” in the Soviet central government’s eyes, of large Central Asian families might not have been often openly mentioned, but the people of Central Asia easily perceived the dynamic and resented any discrimination from pronatalist polices that followed

There is disagreement in the literature over the origins of the conflict between ethnicities that ultimately resulted in the secession of the Republics and collapse of the USSR. One school of thought argues that undercurrents of tension started under Brezhnev, caused in part by Russification policies, which prepared the way for Soviet demise (Brubaker Reference Brubaker1996; Nahaylo and Swoboda Reference Nahaylo and Swoboda1990; Tishkov Reference Tishkov1997; Tompson Reference Tompson2003). Another school of thought alleges that under Brezhnev the policy of “corporatist compromise, ethnic equalization and masterly inactivity” kept the nationalities issue on an even keel without too much tension until perestroika (Fowkes Reference Fowkes, Bacon and Sandle2002, 68). Some have even gone so far as to argue that Russian leaders actually wanted to get rid of the Central Asian Republics by the 1980s, thus solving the demographic and economic problems in one go (Toft Reference Toft2014, 193). Proponents of this view point to the lack of coherent independence movements in Central Asia, as well as the concentration of natural resources within Russia itself, which meant Russia did not need to rely on the Southern Republics economically (Olcott Reference Olcott1998). While a few commentators, such as the nationalist dissident Solzhenitsyn, did express this view publicly, polls indicate that the vast majority of people in Russia wanted the union to remain together (CIA 1991), and there is little evidence that anyone in the Politburo supported this position before 1991. The desire to mold the population of the existing Soviet Union was far more common among leaders than any desire to reduce territory and population.

In considering events from a demographic perspective, this article supports the position of Tishkov (Reference Tishkov1997) and Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1994) who highlight the defining role of national elites over ordinary people in driving and shaping ethnic conflicts. Moscow-based technical elites and politicians alike failed to grasp the structural and economic issues of state socialism, too often seeing the problem as a fixed issue of population dynamics. Ordinary people from Central Asia may have paid little attention to the issue, but Moscow leaders antagonized politicians and experts in Central Asia by claiming local economic troubles were a result of their reproductive choices. In doing so, they undermined the stability of the relationship between central and peripheral ruling class, increasing tensions that lead to the secession of the Republics.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that, from the 1970s onwards, the Soviet government saw higher birth rates among Central Asian Republics as a threat to their control, to national identity, and to the stability of the USSR. Russian leaders and much of the Slavic intelligentsia worried that their dominance within the Union would be undermined if they were no longer a numerical majority. Real economic issues appeared as a result of differential fertility and the labor imbalances it caused. Low levels of Russian language in some Republics also presented a problem for the military and for industry. However, understanding of these issues was tinted with prejudice, and the Soviet government was all too willing to abandon other solutions in favor of changing the population itself by altering patterns of reproduction. In doing so, they divided Central Asians from other Soviet peoples, portraying them as distinct groups who had a predetermined role and place in life.

For all the hot air about population issues and fertility throughout the 1970s and 1980s, little actually changed from a policy perspective (Bridger Reference Bridger and Kay2007). The experience of bringing up children had hardly been transformed by moderate increases in benefits, and research by Russian demographers demonstrates that the completed cohort fertility rates were unchanged by pronatalist policies of the 1970s and 1980s (Frejka and Zakharov Reference Frejka and Zakharov2013; Zakharov Reference Zakharov2008). The government did not achieve its desired outcome of evening out differential fertility rates. In the process of trying, ministers actually damaged their relationship with key Republic leaders in parts of Central Asia. A vast literature has shown the role that ethnic tensions played in the ultimate dissolution of the USSR. Demographic change was a particularly important aspect of this because it made the tensions seem more urgent. The government did not perceive the status quo as a stable situation but as a ticking timebomb demanding urgent attention. By aiming to solve economic issues with demographic solutions, the government alienated parts of the Central Asian establishment who saw this as a discriminatory attack on their rights and culture.

Beyond angering local elites, the fact that Moscow leaders failed to appreciate the structural and operational issues of the Soviet system left them unable to tackle these challenges. In the end, the enormous problems facing leaders simply looked easier to tackle when viewed through the prism of population policy. Propaganda on childbearing was easy and cheap in comparison to reskilling the population, effectively incentivizing migration to labor shortage areas, or getting those on the periphery to effectively identify with the Soviet Union as a nation. Even had they been willing to seriously attempt these incentives, prejudice against Central Asian peoples meant Moscow leaders were unlikely to ever see these populations as an acceptable substitute for Slavic people. When considered in its entirety, the problem was one of both economics and belonging, as identity and culture led leaders to misdiagnose many economic issues through the frame of population, making them far more difficult to resolve.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Laurence Markowitz and Anna Greenwood for reading early versions of this article and providing valuable advice for refining it further. The Researcher Academy at the University of Nottingham granted funds for attendance at the ASN 2021 conference where this work was initially presented as a research paper. I am also grateful to Nick Baron and Sarah Badcock for their general academic guidance when completing this research.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council of the UK (grant number: ES/P000711/1)

Disclosures

None.