Soft power is the ability to exercise influence through attraction (Nye Reference Nye1990; Reference Nye2004). For political scientist Joseph Nye, who coined the term in the dying days of the Cold War, soft power involves three aspects: the appeal of a country’s culture, the attractiveness of its political values, and its foreign policy. In recent years, with the increase in student mobility, growth of technologies, and development of the internet and social networks, projects and programs in the field of education and culture have become an effective means of projecting soft power. Higher education is traditionally considered an opportunity to shape worldviews and generate positive exposure to the local culture. Student exchanges form a key part of this effort (Nye Reference Nye2004). This article examines academic diplomacy and the role of educational programs and research collaboration in the projection of China and Russia’s soft power in Tajikistan.

In this article, we examine how Russia and China use education to implement soft power in Tajikistan and the differences between the two approaches. We conclude that Russia is in a stronger position to project soft power in Tajikistan, and, although the escalation of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 will undermine this influence, China will not displace Russia’s soft power in the near future.

In Tajikistan, the poorest country in Central Asia, the level of teaching in higher educational institutions is steadily declining with low pay, underqualified teachers, limited research funding, and barriers to academic freedom all hampering the development of the education sector in the country (Kataeva and DeYoung Reference Kataeva and DeYoung2018; Jonbekova Reference Jonbekova2015, Reference Jonbekova2018; Kataeva Reference Kataeva2017; Shamatov, Schatz, and Niyozov Reference Shamatov, Schatz and Niyozov2010). Therefore, the demand for quality education abroad significantly exceeds the supply. Under these conditions, there are ample opportunities for foreign powers to strengthen their influence in the country through the implementation of education programs. Within the context of the country’s authoritarian system, in which higher education is a tool of indoctrination and legitimation of the regime, the government has opted for educational cooperation primarily with autocratic partners. Our focus in this article is Tajikistan’s two most prominent educational partners: Russia and China.

First, we analyze the content of educational programs and the scientific and educational disciplines that they cover. Another criterion for evaluation is the volume and coverage of educational and scientific programs, their duration and sustainability. Second, we analyze the instruments or institutions of soft power in the field of education and science – this includes organizations and structures through which relevant educational and scientific programs and projects are implemented.

China and Russia’s Soft Power Push

Over the past thirty years, soft power has become a widely used concept in academia and policy circles. Soft power refers to the ability to “get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments” (Nye Reference Nye2004, x) by shaping “the preferences of others” (Nye Reference Nye2004, 5). The soft power of a country rests primarily on three resources: its culture, its political values, and its foreign policies. Nye’s conception of soft power bears a close resemblance to political scientist Steven Lukes’ (Reference Nye2005) “third face of power,” the ability to shape other’s beliefs and preferences and Barnett and Duvall’s concept of productive power, the production of subjectivity in systems of meaning and signification that embed a particular consciousness onto members of that society (Barnett and Duvall Reference Barnett and Duvall2005). This in turn is derived from Italian communist theorist Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, which argued that discourses help the dominant social group normalize their rule though the generation of consent (Gramsci Reference Gramsci2011; Cox Reference Cox1983). Soft power is based on representational force; it involves the wielder representing reality in a certain way in an effort to attract others (Bially Reference Bially2005). The study of soft power in international relations is linked to other work on the importance of status (Larson et al. Reference Larson, Paul, Wohlforth, Larson, Paul and Wohlforth2014; Holbig Reference Holbig2011) and prestige (Fordham and Asal Reference Fordham and Asal2007) both as aspects of influence and qualities that need to be defended.

While soft power cannot be arbitrarily created, it can be harnessed and manipulated by actors (Nye Reference Nye2013). As Gallarotti argues, “harnessing the benefits of soft power will depend on decision-makers’ abilities to appreciate and exploit such benefits” (Gallarotti Reference Gallarotti2011, 39). One aspect of the harnessing of soft power is known as public diplomacy. Public diplomacy refers to “the process by which direct relations with people in another country are pursued” by state and non-state actors “to advance the interests and extend the values of those being represented” (Sharp Reference Sharp and Melissen2007, 106). Nicholas Cull divides public diplomacy into five elements: “advocacy, cultural diplomacy, exchange diplomacy, and international broadcasting” (Cull Reference Cull2008, 33). The medium of higher education is one aspect of public diplomacy and soft power, linked most closely to exchange diplomacy and cultural diplomacy (Gallarotti Reference Gallarotti2022; Nye Reference Nye2005, Atkinson Reference Atkinson2010, Kramer Reference Kramer2009). For example, the US Fulbright program has financed over 400,000 students from 150 countries since 1946. Educational exchanges create a sense of community or understanding between participants and their hosts, and the attainment of a politically influential position by the exchange participant after returning home (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2010). People gain a particular kind of human capital from cultural immersion as a result of study abroad. Some have referred to this as imprinting, denoting the positive effects that exposure has on individuals who study abroad and the way in which this shapes international influence (Lowe Reference Lowe2015). For example, Atkinson finds that educational exchanges were associated with increased propensity to respect human rights (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2010).

According to Nye, soft power, with its roots in a vibrant civil society and an attractive political culture, is incompatible with authoritarian regimes (Nye Reference Nye2013). Yet the concept has been eagerly engaged with in authoritarian countries as well. Nye’s 1990 article was translated into Chinese in 1992. One year later, the first article on soft power authored by Chinese academic Wang Huning appeared. In the article, Wang Huning argued that “culture is not only the basis for policy making, but also the ability to influence and set the tone for the public in other countries” (Mingjiang Reference Mingjiang2008, 167). Interest in soft power within China has grown steadily over the subsequent decades (see Figure 1). Based on the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database, which compiles Chinese-language scholarship, from 1992 to 2021, there were 27,929 articles published in academic journals in China with the term “soft power” in them. References to the term peaked at 2,493 in 2012, the year Xi Jinping came to power, before decreasing to 1,130 by 2021. This tracks with Xi Jinping’s shift away from the narratives of “peaceful rise” and “harmonious world” toward a more assertive foreign policy of “great rejuvenation” (Economy Reference Economy2020).

Figure 1. References to “Soft Power” in Chinese Academic Journals (1992–2021)

Source: https://oversea.cnki.net/index/.

Since 2001, when China announced it would be “going global” (zou chu qu), China has been trying to establish itself as a cultural power with a favorable national image (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2015). During his speech at the 17th National Congress of the CCP in 2007, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Hu Jintao stated that

Culture has become a more and more important source of national cohesion and creativity and a factor of growing significance in the competition in overall national strength […] We must enhance culture as part of the soft power of our country to better guarantee the people’s basic cultural rights and interests. (China Daily 2007)

This prioritization of shaping China’s image abroad continued, but has evolved, during the administration of his successor. In 2013, Xi Jinping made a speech where he told diplomats that the government needs to “tell China’s story well” (jianghao zhongguo gushi). Chinese soft power aims to dissuade people from thinking China is a threat and cultivate those who see it as an opportunity. China has promoted a “politics of harmony,” seeking to impress on the world that there is no reason to worry about a rising China (Hagström and Nordin 2019). China’s soft power relies on the positive values of morality, good governance, and peace associated with traditional religions and schools of thought associated with Chinese culture such as Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism (Huang and Ding Reference Huang and Ding2006; Ding Reference Ding2008; Blanchard and Fu Reference Blanchard and Lu2012). Chinese soft power is exercised via the global media, including China Global Television Network and via mega events such as the 2008 and 2022 Olympics and the 2010 Shanghai Expo.

Education is at the center of this “authoritarian image management” (Dukalskis Reference Dukalskis2021). The educational aspects of China’s soft power rest on a number of pillars. First, China established a series of Confucius Institutes to promote and teach Chinese culture and language around the world. Confucius Institutes have become key tools of China’s soft power. The first Confucius Institute was founded in Seoul in 2004, and the first in Central Asia opened in Tashkent in 2005. The programs consist mainly of language courses at various levels and a wide range of cultural events such as exhibitions, film screenings, and various talks (Hartig Reference Hartig2015). Brazys and Dukalskis found that Confucius Institutes improve tone of media reporting about events relevant to China in that locality by an average of 6% (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2019). Second, China has attracted almost half a million foreign students to the country. “University soft power” or “scientific diplomacy” forms an effort to develop common understandings and positive attitudes towards China (Altbach Reference Altbach1998; Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen2012; Li Reference Li2018; Lo and Pan Reference Lo and Pan2021). Government figures show that in 2018 there were a total of 492,185 international students from 196 countries in China. Further, 63,041 international students (12.81%) received Chinese government scholarships (Ministry of Education 2019). These educational policies have focused on promoting knowledge of the Chinese language and STEM. They aim to bolster the reputation of China’s universities and turn students into a “bridge” to promote China abroad.

Chinese soft power has been subject to many studies (Barr Reference Barr2011; Edney Reference Edney2012; Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2007). Some articles have focused on the role and effectiveness of Confucius Institutes in what Brazys and Dukalskis call “grassroots image management” (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2019). Confucius Institutes “unabashedly serve as the global-local keystone for China’s commercial, cultural, and linguistic proselytization” (Ding and Saunders Reference Ding and Saunders2006, 20). Other studies have attempted to measure the effectiveness of soft power. Sheng Ye (Reference Ye2013) found that students in Shanghai held a positive view of China and Hong (2014) found more mixed effects, with only half of the students from the EU studying in China leaving with a positive impression of the country.

Russia took longer than China to engage with the concept of soft power, with the first reference only appearing in 2000. Russia included the concept of soft power in the 2000 Doctrine of Information Security and its 2013 Foreign Policy Concept (Sergunin and Karabeshkin Reference Sergunin and Karabeshkin2015). In a 2012 speech, Putin defined soft power as the “promotion of one’s own interests and approaches through persuasion and attraction of empathy.” In the wake of the colored revolutions in Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004), and Kyrgyzstan (2005), Russia intensified its efforts to shape its image abroad. It founded the Valdai Club of international experts in 2004, the news channel Russia Today in 2005, the Russian World Foundation in 2007, the government agency for supporting “compatriots” (sootschestvenii) abroad, Rossotrudinichestvo in 2008, and the Gorchakov Foundation 2010. These became the tools for image management and for managing diaspora relations. Much of Russia’s use of soft power is negative insofar as it focused on undermining the soft power of the West (Kiseleva Reference Kiseleva2015; Callahan Reference Callahan2015, 219–220).

Russian soft power has been the source of increasing scholarly attention in recent years (Simons 2014; Velikaya and Simons Reference Velikaya and Simons2020), with some arguing that Russia has limited soft power (Leichtova Reference Leichtova2014; Skriba Reference Skriba2016; Rutland and Kazantsev Reference Rutland and Kazantsev2016) and others arguing its soft power is significant (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2015, Reference Laruelle2021; Kaczmarska and Keating 2017; Sergunin and Karabeshkin Reference Sergunin and Karabeshkin2015). Russia specialist Marlene Laruelle argues that Russia’s use of soft power rests on four pillars: its history and culture; the Soviet legacy; its political identity as an authoritarian, non-Western state; and its disruptive role in international relations (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2021).

Scholars have examined how the kinds of activities organized by the Russian state to manage its image abroad and maintain relations with its diaspora bear striking resemblances to the Soviet past. The friendship associations and cultural programs appear modeled on Soviet practices and framings, such as narratives of druzhba narodov (friendship of the peoples), which stressed fraternal relations of peoples of different nations and dom kultury (Houses of Culture), which were sites for the projection of state power. Russian officials have even openly acknowledged this. Head of Rossotrudnichestvo Konstatin Kosachev stated his organization was a successor to the “traditions and practical skills which emerged in the old Soviet times” (Kosachev Reference Kosachev2012). Scholars working on soft power in Central Asia have generally concluded that Russia and China’s use of soft power in the region has been inconsistent and ineffective (Nourzhanov Reference Nourzhanov, Nourzhanov and Peyrouse2021; Peyrouse Reference Peyrouse, Nourzhanov and Peyrouse2021). In the next section, we unpack this with reference to Tajikistan.

The Educational Landscape in Tajikistan

There are currently 40 institutions of higher education in Tajikistan. Upgraded from its original status as a pedagogical institute in 1947, the Tajik National University (TNU) remains the main university in Tajikistan. According to official statistics, there are currently 227,026 university students, 83,557 of whom are women. In addition, there are 2,108,942 students studying in primary and secondary schools in the country (Ministry of Education 2021).

The government does stress the importance of higher education for the socioeconomic development of the country, placing emphasis on universities as training grounds for the next generation of specialists in the country (Government of Tajikistan 2012). The 2020 budget for education is $442 million, which is 20% of the total state budget and 5.2% of the country’s GDP. Yet, in reality, academia in Tajikistan is characterized by “state control over curricula and assessment; corruption and sale of grades and degrees; isolation of academics from supranational professional communities” (Amsler Reference Amsler2007, 9). Tajikistan’s higher educational system is subsumed by the state, functioning as a conveyor belt to produce docile citizens and future government employees (Antonov, Mullojonov, and Lemon Reference Antonov, Lemon and Mullojonov2021). Researchers are underpaid and lack institutional resources for research. Only one third of all faculty meet minimum criteria to teach in universities (Jonbekova Reference Jonbekova2015).

In this context, higher education institutions in Tajikistan have sought international partnerships (Sabzalieva Reference Sabzalieva2020). While they have sought partnerships with universities, foundations such as the Open Society Foundations and government-run institutions such as British Councils, Goethe Institute, and American Spaces, the authoritarian government has treated such programs with suspicion. In 2022, the Open Society Foundations closed its office in Tajikistan after coming under too much pressure from the government. Within such an authoritarian context, Tajikistan has increasingly sought educational partnerships with authoritarian states such as Russia and China.

Russia’s Resilient Soft Power

Independent Tajikistan is still geopolitically dependent on the Russian Federation. Russia has provided over 90% of the arms imports to the country since 1991 (Lemon and Jardine Reference Lemon and Jardine2020). It has over 7,000 troops stationed in the country at its 201st Military Base. Bilateral trade amounted to $1.3 billion in 2021, or one fifth of Tajikistan’s total trade turnover (TASS 2022). Over one million migrants from Tajikistan live in Russia, with remittances contributing to one third of Tajikistan’s economy. In short, Tajikistan remains highly dependent on Russia. But one understudied aspect of Russia’s role is its influence in higher education.

Russia’s position in Tajikistan is still shaped by the legacies of over seventy years of Soviet rule. During the Soviet Union, Moscow hosted a number of educational institutions aimed at fermenting communist movements around the world, including strengthening communist values in Central Asia. The Communist University for Toilers of the East and the Lenin International School were founded in 1921 and 1926, respectively, to carry out this mission. The Patrice Lumumba University, later renamed Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, was founded in 1960 to target countries in the Third World (Katsakioris Reference Katsakioris2019).

It was during the Soviet Union that Tajikistan’s first universities were established. Academics in the Soviet Union had access to significant salaries, resources, and networks as part of the large Soviet educational system (Kalinovsky Reference Kalinovsky2018). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia remained the main external educational actor in the country. The Russian language remained the lingua franca of academia. Russia remained the primary destination for students to study abroad.

Scholarly links remain strong between academics in both countries. Officially, there are 20 protocols, treaties, and agreements between the government of the Republic of Tajikistan and the government of the Russian Federation on international cooperation in the field of science, health, culture, and higher education. A 1998 agreement establishes mutual recognition of degree programs in both countries. The Soviet-era Accreditation Commission and its Councils of Scientists set both bureaucratic and political rules, preventing critical engagement by Tajik scholars. The body, which is housed at the Academy of Sciences, is responsible for the certification of personnel and accreditation of PhD dissertations. It was created as part of the agreement between the government of the Russian Federation and the government of the Republic of Tajikistan signed in February 1997 (Antonov, Lemon, and Mullojonov Reference Antonov, Lemon and Mullojonov2021). At the moment, under the Higher Attestation Commission of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation on the territory of the Republic of Tajikistan, more than 20 dissertation councils are accredited and operate in which citizens of Tajikistan defend their doctoral dissertations. The Russian language is still considered the main scientific language in the republic, which also increases the interest in studying in Russian scientific institutes and connecting with scholars there.

Despite moves toward adopting the Bologna Process, Tajikistan’s education system remains largely modeled on Russia’s and the law On Higher and Postgraduate Professional Education, containing wording directly copied from Russian legislation and from the Commonwealth of Independent States Interparliamentary Assembly, the body tasked with legal harmonization in the former Soviet Union (Antonov and Lemon Reference Antonov and Lemon2020). According to our analysis, the Tajik law contains 17% of the wording of the Russian law, first adopted in 1996, and 60% of the CIS model law, adopted in 2002.Footnote 1 They all contain the same understanding of the purpose of higher education as (1) “the intellectual, cultural and moral development,” (2) “the development of sciences and arts through scientific research,” and (3) training for professional development.

Cooperation in the field of higher education includes activities that take place in Russia and those with Russian support within Tajikistan. Student exchanges form a cornerstone of this academic diplomacy. Russia has quotas allocated to applicants from Tajikistan to its universities. Russia still maintains a system of discounts and benefits for applicants from Tajikistan, which makes it more attractive in comparison with studying in Western universities. An annual educational fair of Russian universities is held, during which graduates of Tajik schools get acquainted with the Russian education system, programs, entrance requirements, and conditions of study. Russia is not alone in offering such scholarships.

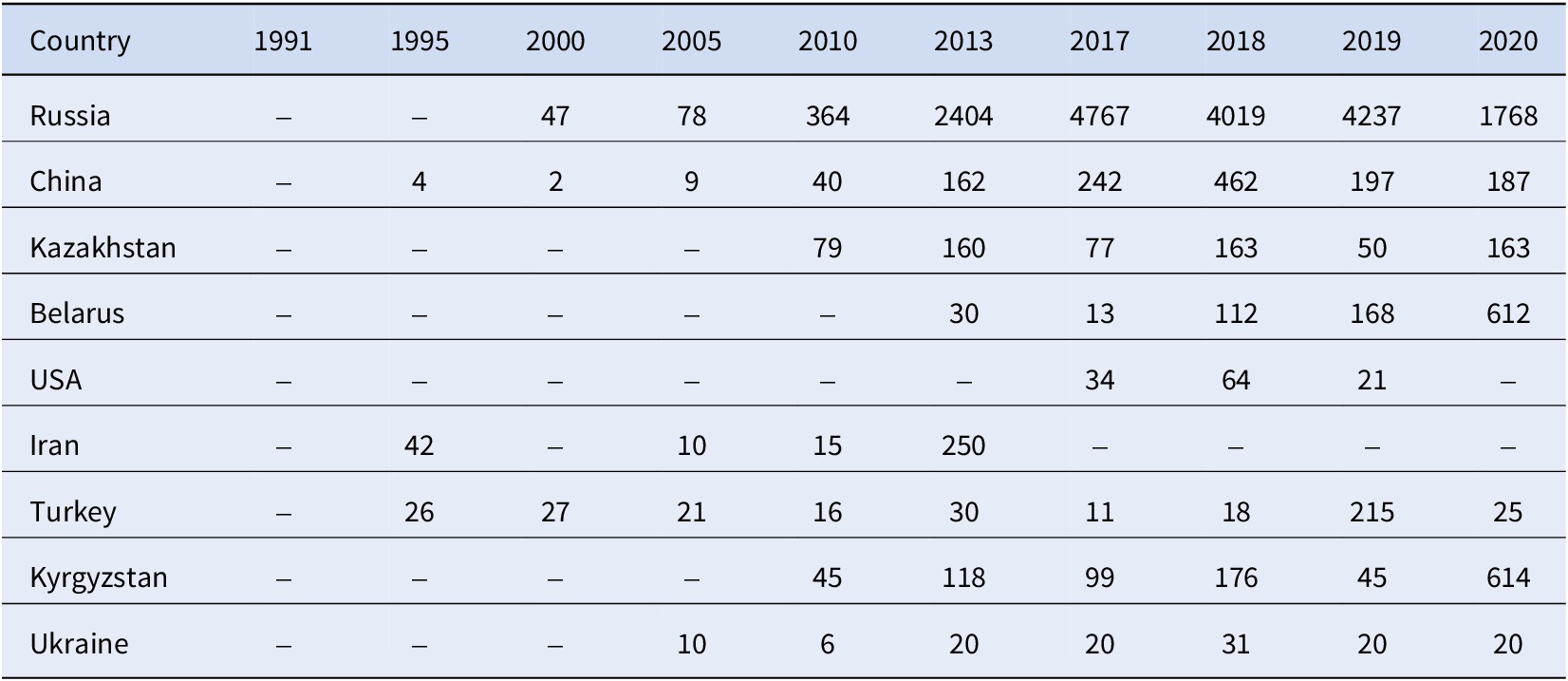

As the Table 1 shows, the majority of Tajik students receive stipends from Russia, which ranks first in the table. China is in second place in terms of scholarships offered to Tajik students. The rest are mainly sent to study in the post-Soviet autocratic countries in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and semi-democratic Ukraine, as well as Turkey and Iran (since 2015; due to the deteriorating relations, cooperation in the field of education has been suspended).

Table 1. Educational Scholarship Quotas of Foreign Countries for Citizens of TajikistanFootnote 2

Source: “Statistical Compendium of the Sphere of Education of the Republic of Tajikistan,” Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Tajikistan, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

In 2020, the total number of Tajik citizens studying in Russian universities amounted to more than 26,000 students (RFE/RL 2021). By 2022, that figure had increased to 30,900. In 2021, Tajikistan received the largest share of Russian educational grants among all former Soviet countries. Winners of international school subject Olympiads are granted the right to preferential admission to the most prestigious universities in Russia.

Within Tajikistan, the Russian government also organizes events of a cultural and educational nature – such as seminars and lectures, language courses, celebrations of Russian holidays, days of culture, and so on – with the involvement of Russian artists, producers, theater and film actors, famous musicians, and performers. Russia has placed emphasis on education, science, and electronic media, considering them as the most effective and basic elements of soft power in Tajikistan. In recent years, a network of Russian secondary schools has been developed in the country. Currently there are 32 Russian-only language schools in the country, with 5 more scheduled to open in September 2022. In 2020, 50 teachers from Russia teach in the country as part of the Russian Teacher Abroad program launched by the Russian Ministry of Education. Further, 12% of students receive at least half of their education in Russian (Ministry of Education 2021).

As part of this approach, Russia intends to popularize the Russian language, education, and science, as well as to form a stable positive image of Russia in the Tajik society (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2015). By actively developing its soft power, Moscow seeks not only to increase its influence in the country but also to create conditions for Tajikistan to join its integration efforts – most notably, in the Eurasian Economic Union. The Union, which brings together Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan, offers members free movement of labor, goods, services, and capital. But Tajikistan has so far resisted Russia’s efforts to have it join the organization.

Russia operates through various institutions. Russian universities are the only foreign universities to have established branches in Tajikistan. Established in 1996, the largest joint educational project is the Russian-Tajik (Slavic) University (RTSU), which has more than 3,500 students and about 300 full-time teachers. In the years that followed, a range of Russian universities established satellite campuses in Tajikistan. A branch of the Lomonosov Moscow State University opened in 2009. The next year, the Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education, National Research University (MPEI) opened its doors in Dushanbe. Two more institutions, Moscow Power Engineering Institute and Moscow Institute of Steel and Alloys also operate facilities in Tajikistan.

In Tajikistan, Rossotrudnichestvo has two offices – the Russian Centers for Science and Culture (RCSC) in Dushanbe and in Khujand, the country’s two largest cities. Rossotrudnichestvo implements its most significant programs through the Russkiy Mir Foundation and the A. A. M. Gorchakov Foundation. The Russkiy Mir Foundation is officially considered a public organization; at the same time, the founders of the fund on behalf of the Russian Federation are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation and the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation. See Table 2.

Table 2. List of Representative Offices of Educational Institutions of Russia in Tajikistan

Since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia’s activities have focused on convincing Tajik citizens about the validity of their narrative on Ukraine and on Russian military might (for example, the “Immortal Regiment”). A good example is the cooperation of Rossotrudnichestvo with 201st Military Base of the Russian Federation in Tajikistan to hold a conference on the topic “Tajiks participants in the Battle of Stalingrad,” which took place in early February 2023. The event was attended by students of secondary school No. 28 in Dushanbe, students of the Russian-Tajik Slavic University and a branch of Moscow State University, including military personnel of the military base. The press release noted that

The conference participants emphasized that today attempts are being actively made to replace historical facts and events. Therefore, they expressed the hope that schoolchildren and students throughout the post-Soviet space will study history more deeply so as not to become the hostages of falsifiers. (Ministry of Defense 2023)

In addition to this, Rossotrudnichestvo in Tajikistan, as in other post-Soviet countries, “carries out a politicized, propaganda, militaristic and pro-war action,” such as the “Victory Dictation,” a competition to test knowledge about the Great Patriotic War (Radio Azattyq 2022). The official Facebook page of Rossotrudnichestvo reports that on September 3, 2022, with the support of Rossotrudnichestvo, the Victory Dictation was held in Tajikistan, in which more than 200 people took part, from among schoolchildren, cadets, Russian military personnel from the 201st Russian military base and military unit 52168 (Facebook 2022). By organizing such actions, Russia spreads the Russian nationalist imperial ideology and ambitions, and also promotes the pro-Kremlin imperial-colonial discourse of military-patriotic continuity toward Russia’s great power in the post-Soviet space.

In addition, the military personnel of the 201 military base of the Russian Federation conduct lessons, seminars, and competitions in secondary schools in Tajikistan and systematically organize public events dedicated to significant dates, in which they actively involve pupils from schools in Dushanbe. A vivid illustration is the 201st military base, together with Combat Brotherhood, an association of veterans of the war in Afghanistan (1979–1989), who organized the event for high school students of the 108th school of the village of Daryobod of the Republic of Tajikistan, in which they told students about large-scale combined-arms operation of the Soviet Army in Afghanistan, code-named “Typhoon” from January 23 to 26, 1989, and about the feat of Soviet paratroopers in the battle near Hill 3234 during the war in Afghanistan (News.Asia 2023). Another example is the provision by representatives of the Russian 201st military base among Tajik schoolchildren of a competition on the topic “What does the 201st Russian Military Base mean for me?” (Asia Plus 2013). Consequently, Russia today, using “soft power” and elements of public diplomacy in its foreign policy through Rossotrudnichestvo, promotes its colonial domination and the new-imperial system of influence in the context of its historical greatness in the former Soviet Tajikistan.

There are four Russkiy Mir centers operating in Tajikistan, which are mainly engaged in the implementation of programs in the field of education and culture, holding various competitions and seminars. Two projects of the A. A. M. Gorchakov Foundation are operating in Tajikistan – the School of Young Experts in Central Asia (since 2012) and the Dialogue for the Future Program (since 2011). There is also a Coordinating Council of Associations of Russian Compatriots (KSORS), which includes 26 organizations with various statuses, cultural centers, and national-cultural communities.

Through these activities, Russia aims to form a stable positive image of the country in Tajik society. Moscow seeks not only to increase its influence in the country, but also to create conditions for Tajikistan to enter the regional organizations it promotes in the post-Soviet space, most notably the Eurasian Economic Union. At the same time, one of the unspoken, but nevertheless, significant goals of this strategy is to prevent the rapprochement of Tajikistan with other great and regional powers such as the US, EU, Iran, Turkey, and China.

China’s Rising Soft Power

China’s influence over Tajikistan has grown sharply in recent years. It has become the country’s second largest trade partner, largest investor and creditor, owning just under half of the country’s foreign debt. Concerned over the potential for spillovers from Afghanistan, China’s role as a security provider in Tajikistan has also grown, with the country establishing its first overseas military facility in the region in 2016.

To help promote China’s image and reduce the potential for resistance to its expanding role in the country, China has used education as a tool of soft power. Cooperation between Tajikistan and China in the field of research education started in 1993 when the sides concluded the Agreement on Scientific and Technical Cooperation. Due to the civil war, between 1993 and 2005, only 263 students from the Republic of Tajikistan were enrolled in Chinese universities.

In 2006, both governments signed a Memorandum of Cooperation in the field of science. In 2007, an Agreement of Cooperation between the Tajik Academy of Science and Chinese Center for Scientific, Technical and Economic Information of Xinjiang (CSTEI) was concluded in Dushanbe. In 2013, the Tajik Academy of Science concluded the Memorandum of cooperation with the Academy of Social Science of China, which is one main Chinese think-tank institutions under the auspices of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China.

Like Russia, cooperation in the field of higher education in Tajikistan includes special quotas allocated to applicants from Tajikistan to Chinese universities. There has been significant growth in recent years. The new agreements considerably increased the number of Tajik students in China; 3,677 Tajik citizens were enrolled in Chinese universities from between 2006 and 2011. Initially, the vast majority of Tajik students studied at their own expense, usually focusing on STEM subjects. According to the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, in the 2012–2013 academic year, 1,389 students from the Republic of Tajikistan studied at Chinese universities, while only 285 received scholarships provided by the government of China or their universities (Alimov Reference Alimov2013). According to the Tajik Ministry of Education, more than 3,000 Tajik students are currently studying in China.

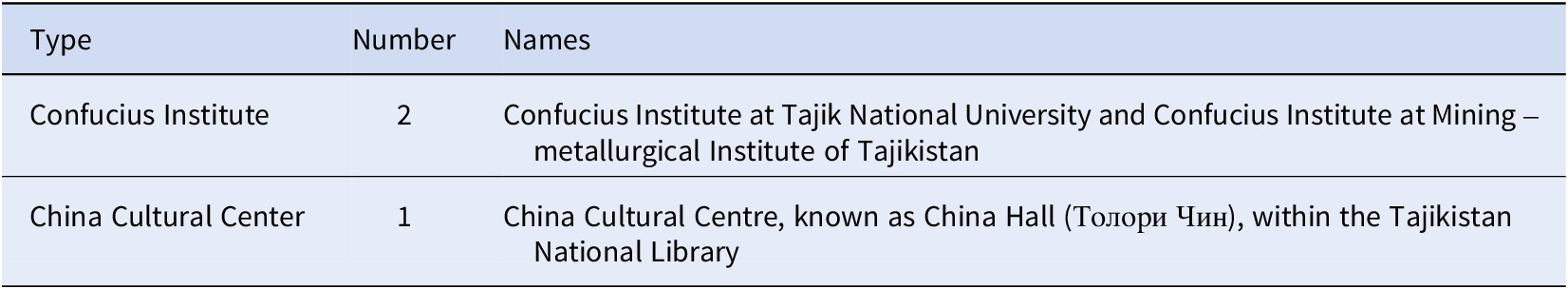

China has also used academic diplomacy in Tajikistan itself. Two Confucius Institutes have been created in Tajikistan – one at the Tajik National University and the other at the Mining Institute in the city of Chkalovsk in Sughd region. Over the past decade, almost 10,000 Tajik students have passed through the Confucius Institute at TNU alone, some of whom then continued their studies in China. In both institutes, the main focus is on the study of the Chinese language, but Chkalovsk also trains specialists for the mining and metallurgical and oil industries, with the goal of also their employment by Chinese enterprises and companies operating in the country.

The opening of a new building for the Confucius Institute at the Tajik National University in Dushanbe in June 2022 was attended by the Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of Tajikistan Matlubahon Sattoriyon, Chairperson of the Committee on Science, Education, Culture, and Youth Policy Nasiba Nurullozoda and Deputy Minister of Education Lutfiya Abdulkholikzoda. A respondent from Tajik National University noted that “such pompous celebrations with the participation of high-ranking politicians and ministers of Tajikistan have not recently been observed with events related to the Russian Embassy, Rossotrudnichestvo and branches of the Russian World in the Republic (see Table 3).”

Table 3. List of Representative Offices of Educational Institutions of China in Tajikistan

A distinctive feature of the Chinese soft power is that it is largely tied to the Belt and Road Initiative. This is also reflected in the specifics of the Chinese educational and scientific programs implemented in Tajikistan and other countries. The overwhelming majority of Tajik students are sent to China to study the language and technical specialties necessary to meet the needs of Chinese companies. Only about 10% of free quotas are allocated for master’s programs. More recently, as part of its strategy to support the Belt and Road Initiative, China has launched its Luban Workshops in the region. The workshops provide vocational training and technological education (China Daily 2022). First launched in 2016, there are now Luban Workshops in 19 countries around the world. In June 2022, the Governments of China and Tajikistan announced the opening of a Luban Workshop at Tajik Technical University that will focus on land surveying and gas transportation (Huang Reference Huang2022). Some scholars in the region note that Luban Workshops may be a new strategy to combat negative views that China’s relationships with the region are purely extractive. While these workshops officially develop vocational skills and boost employability while supporting China’s BRI, experts worry they will make local workers dependent on Chinese technology (The BL 2022).

Tajik scientists, the main representatives of official analytical institutions (Center for Strategic Research and the Academy of Sciences), are often invited to participate in international conferences organized by Chinese universities and research centers dealing with the CIS. The main goal of such joint academic initiatives sponsored by China is to provide the relevant government agencies in China with high-quality analytics and to assist in the development of the main directions and strategies of Chinese foreign policy.

Another equally important goal is to develop cooperation with foreign scientists and analytical institutions, as well as to create a positive image of China. In the past few years, there has been a rapid growth in the number of research institutes in China for the study of Central Asia and the CIS. In other words, while in the West and in Russia funding for Central Asian research has been steadily declining over the past decade, in China we are witnessing the opposite picture (Zhu, Jardine, and Marrachione Reference Zhu, Jardine and Marrachione2022).

Scientific cooperation between the two countries is still limited when compared with Russia. It is mainly somewhat one-sided, with students and academics from Tajikistan going to China rather than vice versa. Despite the growing number of Chinese academic institutions dealing with the CIS countries, Tajikistan has not yet developed its own school of Sinology. China has not proven a popular destination for Tajik students. Language barriers and visa regulations, coupled with the cost of living, have deterred many from studying there.

Comparing China and Russia’s Soft Power

Russia and China have similar approaches to soft power. As Wilson argues, they both adopt a top-down approach, viewing the state as the primary agent of soft power rather than civil society (Wilson Reference Wilson2015). Both Russia and China are interested in promoting alternative values to those promoted by the West (Beeson 2013). This appears to be the case in Tajikistan. First, the main directions, topics and design of educational programs and projects resemble one another. For example, in both cases, the main emphasis is on youth and student programs, including the allocation of significant quotas for education in the best higher educational institutions, grants and scholarships, providing access to other universities and institutions, opening courses on language and culture, providing training workshops and seminars. Both countries support scientific and academic projects with the participation of Tajik scientists.

Second, the approach to the formation and design of educational programs is also similar. In Russia (as well as in other authoritarian countries) and China, the teaching methods mainly emphasize memorization without any attempt to develop critical thinking. Of course, this approach is more appealing to the authoritarian regime in Tajikistan, which promotes the education of their citizens in fellow authoritarian regimes Russia and China and do not particularly welcome educational exchanges with Western universities (Radio Ozodi 2019).

Nevertheless, significant differences between the two powers exist. First, China has at its disposal much greater financial resources and funds that it can spend on educational and academic projects. For example, Russia doubled its spending on cooperation with other countries in the field of culture and education from 3.7 billion rubles ($56.5 million) to 7.4 billion rubles ($113 million) between 2016 and 2019 (Ministry of Education 2019).Footnote 3 At the same time, the total budget of Chinese soft power programs is about $10 billion (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2015).

With more funding, China can pay more attention to the development and design of its programs and projects, fund large scholarships and grants, provide better conditions, and organize more scientific conferences. If we take the dynamics of the growth of quotas and grants for Tajik students and scientists, here China is somewhat ahead of Russia. As Table 1 documents, scholarships from China increased tenfold from 2010 and 2020, while Russian scholarships increased fivefold.

At the same time, there are a number of other factors that give Russia an advantage. Among these factors is a common historical past – namely, 70 years of common history within the USSR. Here, we are talking not only about the general knowledge of the Russian language and culture in Tajikistan. Tajik public consciousness is still characterized by a sense of nostalgia for the Soviet times, when the level and quality of life far exceeded today. The large number of Tajik labor migrants in Russia and the continued dominance of the Russian-speaking information space in the country are also key factors. All these factors have a positive effect on the perception of Russia, creating exceptionally favorable conditions for the development and strengthening of the Russian “soft power” in the republic.

What little survey data that exists indicates that perceptions of Russia are more favorable than those of China. Surveys conducted by Pew, the Central Asia Barometer, and others within the country have not asked questions about perceptions of foreign powers due to Tajikistan’s authoritarian system. The Eurasia Development Bank conducted a survey of perceptions of foreign powers in the country from 2012 to 2017. Their data pointed to Russia being perceived within Tajikistan as the friendliest foreign power with 78% labeling it as such in 2017 (Zadorin et al. Reference Zadorin, Karpov, Kunakhov, Kuznetsov, Rykov, Shubina and Pereboev2017). Just under half of respondents said they would go to Russia to study, by far the most popular country. Of the respondents, 37% called for more cultural exchanges and 51% more educational cooperation.

Chinese “soft power” in Tajikistan is developing rapidly, especially in the past few years as it has expanded its economic and security footprint in the country. But its effectiveness appears limited. In contrast to perceptions of the West, and to some extent Russia, China does not have the same imperial baggage (Dadparvar and Azizi Reference Dadparvar and Azizi2019). Nonetheless, levels of Sinophobia remain high in the country, hampering the effectiveness of China’s soft power push. The Eurasia Development Bank Survey points to just 10% of Tajik respondents calling for more educational exchanges, 3% supporting cultural exchanges, and just 20% viewing China as friendly, significantly lower figures than for Russia.

One of the other important factors is the significant decline of Chinese “soft power” in light of reports of pending repression against the Muslim population in China. In addition, against the background of the transfer of land, the ever-growing economic and debt dependence on China, Tajik society today has a somewhat stern attitude toward China. Accordingly, this creates unfavorable conditions for a positive perception of China and the development of Chinese “soft power” in Tajikistan. And, undoubtedly, this gives Russia a significant advantage in the fight against the expansion of “soft power” in Tajikistan and the region as a whole.

If we take other aspects into account, Russian projects are still aimed at reaching a larger audience and a larger number of educational disciplines. As for Chinese educational programs, there is much less space for choice; as mentioned above, many projects funded by China are aimed at learning the language and technical specialties necessary to meet the needs of Chinese companies. Accordingly, thanks to these factors (widespread knowledge of the Russian language, greater choice, and accessibility of universities), Russian educational projects in Tajikistan are still popular and in greater demand than their Chinese counterparts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the attractiveness of Russian educational programs and academic opportunities continues to dominate in Tajikistan even in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Russians do not have serious competitors in this field. Western education is available only to a limited circle of selected representatives of the elite and the upper middle class; but for the vast majority of ordinary citizens, the Russian direction is the most optimal combination of price and quality.

As for the geopolitical influence of China, it is still based mainly on the economy and investment. This creates conditions for influencing the policy of local authorities, but is by no means enough to ensure the growth of the popularity of China. Overall, the similarity of approaches and strategies only exacerbate the geopolitical competition between China and Russia, which is not manifested or declared openly but nevertheless exists and is gradually increasing.

Two factors may undermine Russia’s position in the coming years. First, its invasion of Ukraine may undermine public support for Russia in Tajikistan. No polling data exists. But estimates from CABAR Asia indicate that two-thirds of posts and comments on the war on Tajik social media support Russia’s position (Mullojonov Reference Mullojonov2022). Despite the sanctions, Tajik citizens continue to migrate to Russia in record numbers, with 103,000 receiving citizenship in the first half of 2022 alone, up from 44,700 in 2019. Therefore, the invasion may not cause significant damage to Russia’s soft power in Tajikistan. Second, with China’s influence growing and the similarities with Russia’s approach, tensions between the two are only becoming exacerbated. This rivalry is not openly declared, but it exists and looks set to grow as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine undermines its position in Tajikistan.

Disclosure

None.

Financial support

Research for this article is funded as part of the project “Authoritarian Policy Transfer in Post-Soviet States,” a project funded by the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies, and the European Research Council (ERC) project “Building a Better Tomorrow: Development Knowledge and Practice in Central Asia and Beyond, 1970–2017.”