Introduction: the diplomat and the gardener

In 1905, the Italian ambassador to the United States, Edmondo Mayor des Planches, toured the numerous settlements of Italian migrants scattered amongst the southern states of the USA. The purpose of his visit was to evaluate conditions (environmental, political, and economic) with a view to establishing agricultural colonies with Italian migrants. Whilst in Mississippi, he observed the relative prosperity of Italian vegetable gardeners (ortolani) or ‘truck farmers’ as they were referred to in the US.Footnote 1 During a visit to the town of Greenwood, he noticed that despite highly cultivatable soil, there was a shortage of vegetables and the agricultural trucking industry was poor. It was one of his accompanying party who raised the question: ‘Why don't Italians in America apply themselves more to truck farming? They would prosper in many towns, small and large, as they did in Memphis, New Orleans and San Francisco!’ (Mayor des Planches Reference Mayor des Planches1913, 131).

This short story introduces the elements and actors this essay explores. On the one hand, Italian migrants were living on the peripheries of American towns, carving out a way of life by using their agricultural skills to produce food for their own consumption and to sell; on the other hand, the authorities were looking to exploit this skill in order to establish Italian agricultural colonies. Of course, there is more to the story, not least the relationships with other non-Italian residents: however, this essay focuses on the interplay of these two elements. It explores US ItaliannessFootnote 2 in the context of a convergence between informal situational agricultural cultivation, achieved by the immigrants themselves, and the governmental visions of agricultural colonisation.

Food and its consumption had a key role in the construction of Italian American diasporic identity (Cinotto Reference Cinotto2014). Indeed, not only food but the agricultural production of food has been seen as a key practice of Italianness abroad. Of course, what exactly Italianness abroad may or may not mean is an entirely complex issue: an interplay between a sense of belonging brought from home and the contextual conditions of being abroad. As this essay explores, certain features allow us to understand this condition further. There has been insufficient documentation on the informal production practices of food, such as urban farming and gardening, that shaped and blurred the dimensions of work and leisure (Fisher Reference Fisher2015). Whilst the central discourse of Italians as undesirable immigrants, perceived as unclean, unhealthy carriers of disease and posing a threat of political radicalism (Kraut Reference Kraut1994) has been explored, less has been said on how this was overcome.

Both Italian and US officials dealing with migration saw agricultural talent as an innate feature of Italianness. Exploiting this assumption, Italian diplomats proposed establishing agricultural colonies in rural southern states, in order to transform Italians into ‘desirable’ immigrants, while providing them with opportunities to profit from these skills. As Mark Choate explains, these strategies should be understood as a form of ‘emigrant colonialism’ (Choate Reference Choate2008). The 1901 Emigration Law saw the Liberal Italian government implement official policies and related private programmes with the aim of turning Italy into a ‘global nation, beyond imperial control and territorial jurisdiction, held together by ties of culture, communications, ethnicity, and nationality’ (Choate Reference Choate2008, 2). The law transferred responsibility for emigration from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This loosened the restrictions defined by the Lanza circular of 1873, the first Italian regulation on emigration. Emigration became a political issue of ‘international expansion instead of an internal haemorrhage’ (Choate Reference Choate2008, 59).

This essay illustrates how Italian migrants and state officials, both Italian and American, were bound together in a relationship that I define as agricultural diplomacy. This revolved around the exploitation of migrants’ agricultural skills on foreign territories in order to spread Italianness abroad. Italianness, as I will demonstrate, held different meanings for each of the main actors involved – meanings which gradually both connected and divided them.

The importance of Italian communities in the US cannot be overlooked when considering the environmental history of Italian migration (Armiero and Tucker Reference Armiero, Tucker, Armiero and Tucker2017, 5). Among the 13 million Italians who crossed the Atlantic Ocean between 1880 and 1924, more than four million reached the United States: the number of Italians in the land of the dollar rose from 55,759 in the 1880s to 4,195,880 in 1920, with a peak of 2,045,877 arrivals between 1900 and 1910 (Daniels Reference Daniels1990). The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the majority of arrivals coming from northern Italian regions such as Veneto, Piedmont, and Friuli-Venezia Giulia, in contrast to the first quarter of the twentieth century, when emigrants were largely poor peasants from the southern regions of Calabria, Campania, and Sicily (Sanfilippo Reference Sanfilippo, Bevilacqua, de Clementi and Franzina2001). The outbreak of the First World War and the emanation of restrictive laws like the Emergency Quota Act in 1921 and the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924, consistently reduced migratory flows into the USA. A migratory pattern emerged that emphasised the link between Italian migrants, senses of belonging, and farming activities (Bevilacqua 2001). For instance, some Italians travelled annually back and forth ‘both from small towns in Sicily and from urban/industrial areas such as Chicago, New Orleans and St Louis, to Louisiana's sugarcane region for the annual harvest, or zuccarata’ (Scarpaci Reference Scarpaci, LaGumina, Cavaioli, Primeggia and Varacalli2000, 2).

This essay introduces agricultural diplomacy as an analytical category to explore, through the lens of environmental history, the entanglement of ‘emigrant colonialism’ with migrants’ practices and the environment, with a comparison between the Italian and US public discourses on Italian immigrants’ agricultural skills, and an analysis of some institutional attempts to create agricultural colonies with Italian immigrants in the United States. To do this, I rely on multiple sources such as American newspapers, archival files and briefs produced by Italian and American diplomats, intellectuals, and agronomists, such as travel reports in the US and emigration guides for Italians.

Migrant Italianness: hybrid gardens in urban spaces

The movements of migrants, combining nature and culture (Armiero and Tucker Reference Armiero, Tucker, Armiero and Tucker2017, 5), leaves traces on landscapes, for example crops or agricultural techniques (Carney Reference Carney2002, Moon Reference Moon2020). Specifically, migrants’ gardens demonstrate a ‘different appreciation of land and natural resources and a porous space blending work, living, and leisure times’ (Armiero and Tucker Reference Armiero, Tucker, Armiero and Tucker2017, 9).

Like other migrants in the Americas (Armiero Reference Armiero, Armiero and Tucker2017), Italians left marks on the landscape, urban and rural. Gardening and urban farming became a major feature of the adjustment practices made by Italians after their arrival in the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Migrants’ gardens should be considered as an informal hybrid space. Seeds brought from the homeland were planted in a new soil and homeland agricultural knowledge was applied to a new landscape. A different vision of managing space and resources emerged. These gardens became defined as ‘ubiquitous’ and often developed in ‘urban farm spaces’ (Diner Reference Diner2002, 62). All urban spaces, from vacant lots, rooftops, or fire escape stairs, were seen in terms of their potential for vegetable growth. This resilient attitude involved a different way of reading the city and its resources: what was urban waste, became fertile (Armiero Reference Armiero, Armiero and Tucker2017, 53–4). ‘Italians, starting with the earliest years of settlement in America, found scraps of urban land, patches of city soil to grow tomatoes, corn, parsley, onions, various greens, zucchini, artichokes. They creatively engineered small spaces to raise goats and chickens’ (Diner Reference Diner2002, 62). Through reclassifying waste, in this distinctly Italian way, they succeeded in finding a means to satisfy the basic needs of not only the immediate family but also the community, cultivating not only food but also a sense of community. Excess produce also provided a means of an entry to economic participation and the pushcarts of hundreds of Italian peddlers selling fruit and vegetables were a feature of many Little Italies in US cities.

For example, the first two decades of the twentieth century saw Italians of New York City cultivating distinctively Italian kitchen garden herbs and vegetables on ‘wooden planters made from discarded soap-boxes’ placed on rooftops (Ziegelman Reference Ziegelman2010, 64) or in the narrow alleys and tenement backyards of Little Italies, where fig trees were also grown.Footnote 3 The fig tree, along with basil and tomato plants, is still a feature of almost all Italian-American residential neighbourhoods in New York City today (Inguanti Reference Inguanti and Sciorra2011) alongside the addition of statues of a Roman Catholic saint, housed in stone grottos made of concrete (Sciorra Reference Sciorra1989, 1). I argue here, that it is the garden that is central to this process. Since medieval times, the vegetable garden has characterised Italian cooking, which is distinguished from other European traditions ‘by virtue of its abundant use of garden products, not only vegetables … but also aromatic herbs – often used with precious spices such as marjoram and mint …, as well as rosemary, parsley, sage, and dill’ (Capatti and Montanari Reference Capatti and Montanari2003, 38). From the Middle Ages, gardens of vegetables, legumes and fruit trees marked the landscape of many Italian cities, especially in the South. Gardens in the outskirts of cities provided urban dwellers with fresh vegetables, herbs, and fruits, while at the same time water from the city and urban wastes (as manures) were used for their maintenance (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua and Bevilacqua1989, 664–67). Along with migrant gardens came food. Food contributed to the reinvention and renegotiation of emerging Italian-American identities. Migrants did not have a singular common food identity, rather there were local habits with regional areas of provenance. All these localised food identities were reshaped through migratory experiences such as availability of ingredients. Through this process they became Italian-American food, spreading Italianness abroad (Cinotto Reference Cinotto2013). Gardening practices, therefore, should be simultaneously understood as attempts to recreate recognisable environments and a means to engage with the new environment.

Can we then, begin to define Italianness through these gardening practices? This Italianness must be considered not as an ethnic mark on the American urban and rural landscape, but as a process of adjustment that involved domestication of the environment in order to make it more readable, welcoming, and comfortable – in a word, familiar. As shown by Simone Cinotto, the resemblances between California and Piedmont were culturally emphasised by Italian and US observers, who in many cases also aimed at driving Italian emigration from and to these areas. In fact, these observers underestimated the work done by those immigrants from Italy who, earlier in the nineteenth century, had cleared the land and tilled the soil in order to recreate familiar landscapes full of vineyards (Cinotto Reference Cinotto2012). Familiar because, in Italy, in addition to their occupation as agricultural labourers, many peasants cultivated gardens for self-sustenance, sometimes even in the middle of cities (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua and Bevilacqua1989, 664–67; Agnoletti Reference Agnoletti and Agnoletti2013, 45-48).Footnote 4

So, from the perspective of Italian immigrants, the garden and related food practices represented the ideal place to create and implement a new identity, merging previous habits and memories with new surroundings whilst creating an entry point to economic participation. However, these Italian customs were not always appreciated by US citizens and authorities: they presented a delicate and often controversial issue, in particular during the Age of Mass Migration.

The American narrative: Italians are somewhere between unskilled peasants and talented farmers

After the inquiries and reports of social reformers and muckrakers, such as Jacob Riis and Upton Sinclair, revealed the unhealthy living and working conditions of migrants stuck in the tenements of the East Coast US cities, the management of these huddled masses became a priority in the US political agenda during the Progressive Era (1890–1920). The formation of the Dillingham Commission, and consequently the Immigration Act of 1907, was an attempt by the US government to find a solution to the immigration problem. However, the commission also created and justified – both legally and scientifically – persistent racial stereotypes (Carravetta Reference Carravetta, Connell and Pugliese2017, 142).

Firstly, the Dillingham Commission made a distinction between old and new immigrants: old immigrants were those who had arrived in the US before the late nineteenth century from England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia, whereas new immigrants were those from southern and eastern Europe, such as Italians, Jews, Poles, Greeks, Serbs, Romanians, and Russians. The latter group were labelled as unassimilable and dangerous, and they had to be Americanised.Footnote 5 This distinction was clearly instrumental in creating a discriminatory stereotype, supported by many historians at the time (Carravetta Reference Carravetta, Connell and Pugliese2017).

Secondly, the Dillingham Commission corroborated a further distinction between Italians of the North (desirable) and Italians of the South (undesirable) (Benton-Cohen Reference Benton-Cohen2018). This discrimination found a scientific rationale in the writings and theories of the physician Cesare Lombroso, founder of the Italian school of positivist criminology, and two of his pupils, the psychologist Giuseppe Sergi and the anthropologist Alfredo Niceforo (Reeder Reference Reeder2019). Their statements influenced the work of the Dillingham Commission, in particular the section dedicated to a census of immigrant races in Volume 5, ‘Dictionary of Races and People'. Italian diplomats, such as Edmondo Mayor des Planches, were aware of the racist attitudes of the US authorities. Mayor des Planches (Reference Mayor des Planches1913, 289) commented that this offensive racial distinction was established by the US government in the assumption that the political unification of Italy had not created an ethnic fusion.

The US press bolstered these stereotypes even before the publication of the Dillingham volumes. In 1881 the New York Times described Italian rag pickers as a ‘dirty horde’, while in 1906 the same newspaper labelled Polish and Italian people surviving by collecting urban refuse as ‘junk men’.Footnote 6

Despite the use of pejorative terms that contributed to building a narrative depicting immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe as problematic, it was still common to find newspaper reports praising migrants’ agricultural skills. The case of the Italians is therefore worth noting for two reasons: firstly, the geographical distribution of Italians employed in agriculture in the US;Footnote 7 secondly, the ways some Italian diplomats exploited their agricultural skills, in a quite precise historical moment which we will further explore, to explore the creation of agricultural colonies on US territory in order to spread their idea of Italianness abroad. For instance, in 1911, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle published an article about Italian truck farmers, describing how they ‘have kept alive farming activity in Brooklyn’. The article describes the quality of Italian farmers in New York, stating how ‘immigrants make gardening pay where natives fail’. Despite these celebratory tones, articles reflected the concerns of US institutions about the large presence of immigrants in city centres and the necessity to make these places less overcrowded. According to a Brooklyn Daily Eagle journalist, Italian immigrants remained in the congested city centres only due to ‘circumstance’: he claimed they felt ‘lost’ there, and would prefer to return to the country, to farms. In rural surroundings, Italians could be ‘the hardest of workers, the best of husbands, the most willing of citizens, the inventive and ingenious farmer’. This ingenuity was expressed in the immigrant's ability to make excellent use of the space available:

They utilize every available bit of space, even going on the roof with boxes containing all the kinds of plants capable of growth in this climate. Even the gardens (and the Italian must have his garden), are part of his labors, and the walks and alleys are used that no space will be lost.Footnote 8

This sort of praise was no surprise in the Daily Eagle. A few years earlier, in December 1904, the editor had written to Mayor des Planches to express support for his project to relocate Italian migrants from the East Coast cities to the US South.Footnote 9 Support of skilled Italian farmers went hand-in-hand with improving living conditions in tenements. Their talent for agriculture, it was said, could help them to choose an environment – defined by the press – that was healthier for them.Footnote 10 Both US authorities and Italian diplomats agreed on this dichotomous interpretation of place (city as unhealthy and countryside as healthy), and subjects (migrants as unhealthy, US citizens as healthy) with the common aim to relocate Italians from the urban tenements to the countryside through the creation of agricultural colonies.Footnote 11 For the Italian government, this was an opportunity to turn its emigrants into desirable subjects in the view of the US government and public opinion. Instead of being stuck in the urban tenements, Italians could use their skills as agriculturists in the US countryside or in the large farms of the southern states. For the US authorities the creation of agricultural colonies with migrants in the southern states was seen as an opportunity to manage this large mass of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, who were obstructing the perceived path towards American urban modernity.

Consolidating this, many US publications encouraged southern and eastern European migrants to settle in the countryside, such as John Foster Carr's 1910 guide to the USA, aimed at Italian immigrants. Various sections depict the countryside as the healthier place with more economic possibilities, where migrants could apply themselves in agriculture and even become landowners. Along with advice on how to buy empty plots of land or one of the many abandoned farms in the eastern part of the US, the handbook also praised Italians who were devoted to the cultivation of vegetables for self-sustenance and for local markets, listing all the Italian agricultural colonies with the crops cultivated. With a much less positive reasoning, the Dillingham Commission also identified the rural environment as a transformative place for Italian migrants:

All in all, the rural community has had a salutary effect on the Italians, especially those from the southern provinces of Italy. In many cases it has taken an ignorant, unskilled, dependent foreign laborer and made of him a shrewd, self-respecting, independent farmer and citizen.Footnote 12

And so, agriculture became the transformative means for otherwise undesirable migrants to become ‘independent farmers and citizens’, both in public opinion and policy. The re-placement of Italian migrants into rural environments was seen as a solution to the disorder of ethnic enclaves in the American metropolis. Aware of these views, Italian officials considered how they could kill two, or even more, birds with the one stone of Italian agricultural colonies, transforming the derogatory narrative of Italian immigrants into desirable subjects and skilled workers in public opinion, managing the migrants’ ‘urban problem’, and at the same time spreading Italianness abroad.

Establishing Italianness in the American landscape: the emergence of an agricultural diplomacy

In 1874, the politician Leone Carpi ‘observed that the Italian word colonia meant not only overseas possessions, but also settlements of emigrants in foreign countries. Carpi proposed, based on this definition, that emigration itself was a type of colonial expansion, though tenuous and unpredictable’ (Choate Reference Choate2008, 2). This semantic overlap affected Italy's foreign policies at the turn of the twentieth century, particularly from the date when Francesco Crispi became prime minister in 1887 to the Libyan war of 1911, and saw an acceleration after the defeat of Adwa in 1896. During these decades the Italian state turned its attention to Italian emigrant populations scattered in many colonies – or ‘Little Italies’ – around the globe, aiming at ‘tutelare l'Italianità’ abroad and building a ‘great ethnographic empire’ (Choate Reference Choate2008, 57–8). Endorsing these transnational relationships, the government promoted a continued sense of shared belonging, stating that Italians abroad were ‘an organic part of the nation … linked through a shared cultural background’ (Choate Reference Choate2008, 8). This endorsement saw cultural ties strengthened through the foundation of many institutions, in Italy and abroad, such as the Italian Chambers of Commerce Abroad, the Mutual Aid societies, the Dante Alighieri Society abroad, and the Italian Geographic Society (Choate Reference Choate2008, 8). The Italian diet was also exploited by the Italian government to reinforce cultural ties and develop commercial relationships with the USA through building numerous networks of Italian food exports from Italy to the US (Chiaricati Reference Chiaricati2020).

Between 1880 and 1912, the Italian government attempted to construct distinctly Italian agricultural colonies by exploiting migratory flows in two characteristically distinct phases. The first phase, in the last decade of the nineteenth century, saw key roles for Francesco Saverio Fava as ambassador of the Kingdom of Italy to the United States (serving from 1881 to 1901) and Alberto Blanc, the previous ambassador, as Minister of Foreign Affairs (1893–1896). This phase aimed to divert migratory flows from Italy directly to these desirable agricultural rural areas, in particular the states in the south of the US such as Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana.Footnote 13 The second phase, which we will explore in the next section, occurred in the first decade of the twentieth century, with Edmondo Mayor des Planches as the Italian ambassador to the USA (1901–1910). This phase focused on relocating Italian migrants from East Coast cities (where, as we demonstrated, they were often seen as a problem) to southern US states, Texas in particular.

For Italian diplomats, agricultural colonies offered an opportunity to spread Italianness abroad and for the American government it was a means to clear the path to urban modernity. Amongst these various institutional drives, agriculture played a crucial role, involving diplomats, international stakeholders and migrants (although sidelined as passive recipients) into a particular form of relationship – agricultural diplomacy.

The diplomatic scheme: how to ‘divert the stream of aliens’Footnote 14

One way the Italian government and its institutions organised and promoted a systematic agricultural colonisation in the United States was to send diplomats and agronomists to visit the settlements where Italians worked as miners, cotton growers, or railroad workers, settlements which in the main were started by Italian clergymen in the second part of the nineteenth century. The aim of these diplomatic missions was to inspect the working conditions of Italian migrants, establish direct relationships with investors and landowners, and study climate and soil in areas where colonisation was planned for the near future.

Edmondo Mayor des Planches was one of the strongest advocates of agricultural colonisation. In July 1903, the New York Times published a short article describing Mayor's aims to locate a colony with thousands of Italians in California because ‘it is most like our land, and we will make it such for our people’.Footnote 15 This image of California as an ideally similar physical environment, leading it to become the most favorable cultural environment, is reiterated with the precise purpose of attracting Italians to relocate there from cities. The article continues by describing Mayor's planned travels to support the migratory flow from East Coast cities to the West. In November 1904, another short piece in the New York Times reported that Mayor would be travelling to Florida, Louisiana, and Texas to make a decisive step towards the solution of ‘the Italian problem’ by considering the possibility of ‘dispersing city Italians into rural communities’.Footnote 16 It was also in 1904 that Professor Antonio Ravaioli, the Commercial Delegate at the Italian embassy in Washington, released his report, reaffirming that climatic similarity would lead to cultural familiarity through crop cultivation, making Italian migrants feel at home.Footnote 17

In 1904, too, Mayor des Planches suggested that the Italian government send Adolfo Rossi, the inspector of the Royal Immigration Department of Italy, to the United States. Rossi met with US Immigration general commissioner Frank Sargent, who supported limitations on immigration into the United States. Sargent told Rossi that the US Congress was planning to open a federal office at Ellis Island with the express purpose of directing migrants to southern states. Rossi replied that the Italian government had the same objective and asked for cooperation between the two governments in order to prevent Italian migrants from getting stuck in north-eastern cities, instead of going south to search for agricultural jobs (Ferraioli Reference Ferraioli2013). Managing the large mass of Italians living in the East Coast cities was a delicate issue for both governments. It became one of the main concerns to influence the pursuit of agricultural diplomacy by the Italian officers.

The extent of the perception of an ‘Italian problem’ emerges in a letter from Tommaso Tittoni,Footnote 18 the Italian prime minister, to Mayor des Planches on 20 March 1905. The letter describes the creation of an International Agricultural Institute in Rome. It voices concerns about the US administration's objective of collecting information on agriculture and crop prices worldwide with its Bureau of Census. The foundation of the International Agricultural Institute was perceived as a menace to US administrative powers, when, in fact, the aim of such a global institution would be to provide support to the regulation of agricultural labour and exchanges, commented Tittoni. The prime minister's letter also exposes the US administration's views on immigration to urban areas. In fact, as Tittoni asserted, the US government deplored immigration from southern Europe to the US cities of the East Coast and made clear attempts at diverting it to the countryside. The establishment of the International Agricultural Institute, concluded Tittoni, would be of enormous help in managing the immigration issue and hence indulge the desires of US government and farmers. The Institute, as Tittoni remarked, could work as a sort of stock market for the worldwide supply and demand of agricultural labourers, helping to divert migratory flows to the US countryside.Footnote 19

Mayor's 1905 reports from his investigative tour of the colonies unsurprisingly confirmed that agricultural colonisation would be beneficial, not least to fulfil the government interests of both Italy and the United States. As reported by the St Louis Globe Democrat on 19 February 1905, Mayor seemed extremely convinced of the possibility to relocate Italians from the cities to the countryside with projects of agricultural colonisation, as he stated: ‘If the Italian immigrants are properly handled, they would be of great benefit to this country. The trouble has been they have flocked to the cities. The United States needs farmers. The Italians will make the best of farmers.’Footnote 20 Cities would become less crowded, southern states more white, and Italianness would be propagated throughout the world. Italian migrants would work the land as they were used to in Italy.

This idea of a global Italian peasant was underpinned by various Italian state institutes such as the Italian Colonial Institute, founded in Rome in 1906, and the Italian Agricultural Colonial Institute (IACI), established in Florence in 1907 (Choate 2003). As underlined by the historian Gian Paolo Ferraioli, Mayor des Planches’ pursuit of his plan can be seen as an answer to US President Theodore Roosevelt's Congress speech on 5 December 1905, in which he reiterated feelings that immigration into Eastern Cities must be limited, and looked favourably on immigration to the south of the US, but only ‘of the right kind’ (Ferraioli Reference Ferraioli2013). Roosevelt explained that ‘the stocks out of which American citizenship is to be built should be strong and healthy, sound in body, mind, and character’.Footnote 21 To keep in line with this, the Italian consulate in New York formed a Labor Bureau managed by Guglielmo Di Palma Castiglione, in 1906, explicitly directing migrants to the south. The 1910 New York Times article ‘Making American Farmers of Italian Immigrants’ described how the Labor Bureau would work ‘in connection with the Bureau of the Department of Commerce and Labor and collaborate as far as possible with the various State Departments of Agriculture’.Footnote 22 In the same year, an Investigation Bureau was created to protect the legal rights of Italian immigrants. The next section explores other actors, namely scientific institutions, lawyers, and railroad agents, who took part in the attempts to relocate Italian migrants, both physically and culturally, away from being a problem in cities to a solution in rural agricultural colonies.

The roles of agricultural scientists, lawyers, and railroad agents in agricultural diplomacy

As we have touched upon, the political rhetoric of relocating and redirecting Italian migration from cities to colonies was achieved through a variety of means, one of which was the idea that physically similar climates would lead to culturally familiar Italianness, a view endorsed by the Italian government which shared the US administration's perception that this solved a perceived problem. A key to this tactic was to create the impression that skilled Italian farmers would be placed in climatically ideal conditions. The IACI had as one of its prime objectives ‘to prepare agents who are specialists in colonial agriculture, for service to our migrant population’ and ‘to act as an information centre for the diffusion of reports on colonial culture, and on the economic and agrarian conditions of non-European countries subject to agricultural immigration …’.Footnote 23 In February 1908, the Institute published a report by one of its agronomists, Dr Tito Tabet, who had been sent to south-west Texas to report on soil conditions and fertility with regard to the creation of an Italian migrant agricultural colony, as promoted heavily in their advertising by the railway company the Rock Island-Frisco System. To pursue this objective, the company employed a professor in agriculture (Dr White) with close links to the German recruiting agent C.B. Schmidt, who had helped create agricultural colonies with Mennonites in Kansas and with Germans and Italians in Pueblo, Colorado. Even without actually owning any land, the railway company strongly supported agricultural colonisation, reported Dr Tabet. The Rock Island company put effort into soliciting the cooperation of landowners and aimed to build a society to provide families of settlers with ‘soil, home, tools, livestock, and seeds’ (Tabet Reference Tabet1908, 3–4). Tabet specified three evaluatory criteria for choosing places to create agricultural colonies: salubrity; drinkable water; and a range of suitable weather temperatures. He also focused on setting the ‘fundamental parameters for an agricultural exploitation’ – the potential fertility of the soil; the availability of water in relation to suitable crops for the chosen place; the climate. In the same report, Tabet predicted a bright future for Texas as ‘the new California’, and he was positive about Italian colonisation projects in Texas: ‘We could compare the south of Texas to the northern shores of our Sicily: salubrious climate and mild temperature, but with lower rates of rainfall’ (Tabet Reference Tabet1908, 32).

This scientification of colonisation projects added significant weight. In addition to Tabet's report, there exists a large correspondence about specific agronomic matters in the archives of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Italian government asked the US Department of Agriculture for numerous scientific publications about diverse topics: the latest news in cultivation techniques and soil experiments; reports on crop diseases; innovations in farm tools and machinery; and there are some requests for sample sets of chemical fertiliser to be used in Italy for experimentation.Footnote 24

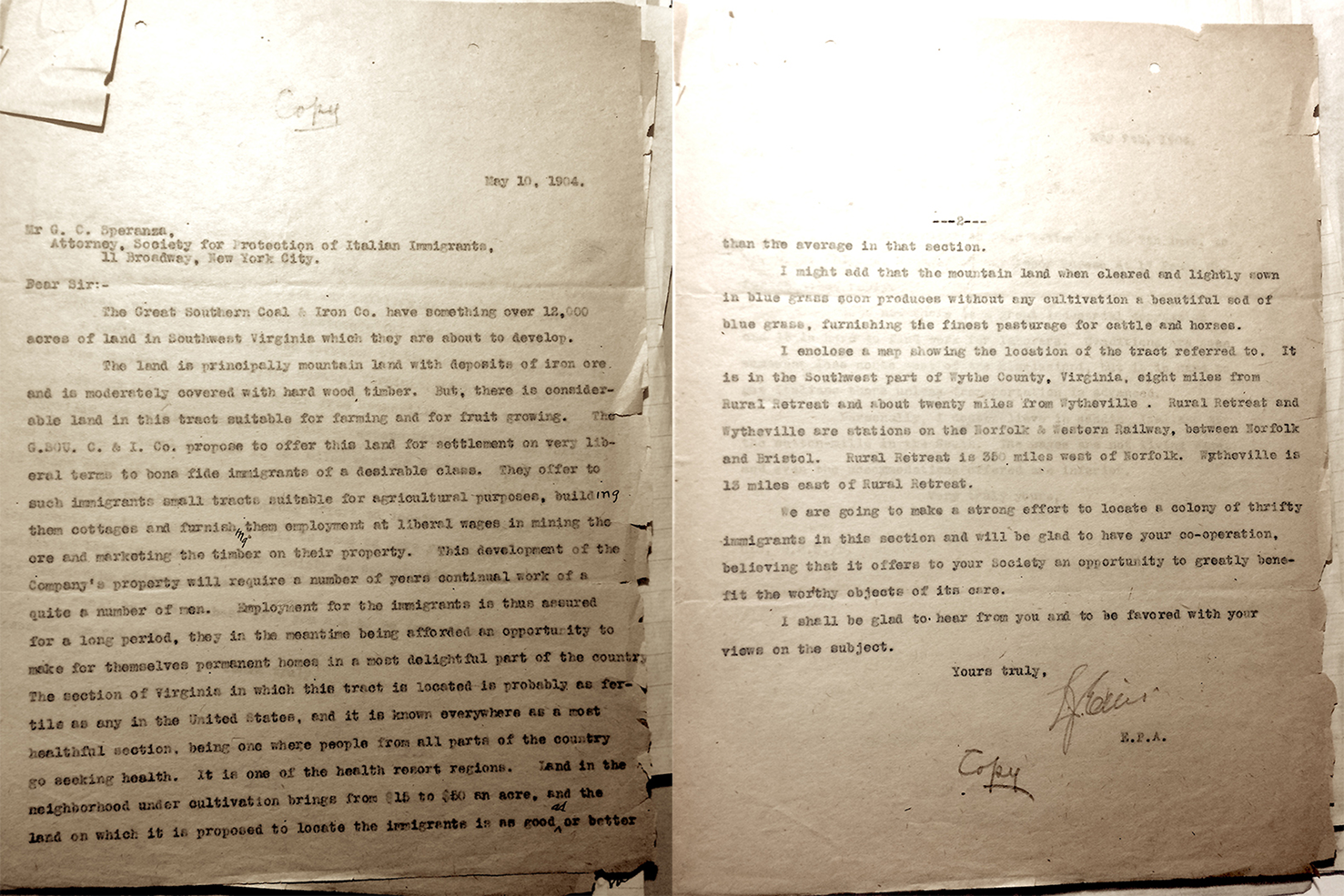

Whilst the science emerged to prove the potential of the southern US states as colonies, more was needed to cement the idea that this was the place to go. In 1897, the Italo-American journalist and lawyer Gino Speranza became legal counsellor to the Italian consulate general in New York. Speranza was also the lawyer for the Society for the Protection of Italian Immigrants (SPII), which had been founded to give legal support to Italian migrants who faced occupational injuries and disputes. On 25 May 1906, Speranza was sent to North Carolina to report on the conditions of workers in the Carolina Company, which had brought many Italian immigrants to North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia to clear land for the South & Western Railway Company. In his report, which was sent to the Italian consul general Conte Massiglia, Speranza expressed his support for US companies recruiting Italian unskilled labourers: however, he emphasised that their working conditions must not resemble forced labour. Reaffirming the discussion in the previous section, Speranza added that this was a good opportunity to study Italian non-farming labour in the south: ‘This possibility should not be lost, since for climatic and other reasons it is preferable than working in the cities’.Footnote 25 The society (SPII) was the connection between the Italian government, American societies and landowners who often asked Speranza to provide Italian migrants to work their lands. On 10 May 1904, Gino Speranza received a letter (see Figure 1) from the Great Southern Coal & Iron Co. (GSC&I). This company owned 12,000 acres of land in Virginia, of which they offered some tracts to lure Italians into mining jobs, including houses and ‘fertile’ land to cultivate as the family garden, for self-sustenance.Footnote 26

Gino Speranza was in close contact with Adolfo Rossi, the inspector of the Royal Immigration Department of Italy, and in 1906, organised another trip for him to Italian colonies in the United States. During this visit, Speranza interviewed Rossi and they talked about colonisation, considering it the ‘distribution of farm labourers and farm hands to agricultural sections, and their eventual conversion into farm owners’. The first question was: ‘Can this be done, or rather can this be ‘‘forced’’ by inducements or legislation?’ The answer for Adolfo Rossi was:

Two conditions are absolutely necessary to the success of any such plan …. First, that the utmost care be exercised in the selection of families who are used to farming, and second, that colonisation be started with small nuclei and not on any large scale. These nuclei, if successful, will themselves develop into larger centres by attracting the families, friends and paesani from the villages from which the pioneers came.Footnote 27

During the years of Fava and later Mayor des Planches as ambassadors in Washington, the Italian embassy received hundreds of letters from landowners, railroad and mining societies expressing the demand for Italian immigrants to create agricultural or working colonies.Footnote 28 Amongst these letters was one from J.P. Spanier's, the Naples-based European agent for the American company, Gould Railway System. Spanier worked for the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (ATSF), a society which, especially in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, was interested in recruiting peasants to convert the fertile agricultural soil of prairies next to railways. In fact, the work of these railroad agents largely shaped the western landscape of the USA, with the gridiron scheme they proposed for arranging migrants’ settlements in the US south (Fullilove Reference Fullilove2017).

In the last months of 1904, Spanier made contact with many companies, such as the Cotton Belt Development Company which was organising the creation of an agricultural colony in Cherokee County, south-west Texas, named ‘Giolitti’, after the Italian prime minister, Giovanni Giolitti.Footnote 29 To these proposals Spanier added a project to create 8,000-acre colonies with 2,560 Italian migrants: the land would be divided into 64 square sections of 120 acres each. Then, each section would be split again into eight triangular areas of 15 acres, each of which contained a farmhouse for a family of five. In the proposed scheme (see Figure 2), red dots represent farmhouses, organised in a circle and close to each other, in order to avoid social isolation. Spanier proposed this scheme many times: it always included a labour contract for the Italian family, and affordable land rent fees for the first years of activity.

Figure 1. Letter from the Great Southern Coal & Iron Co., May 1904. Source: Gino Speranza Papers, Box 12, New York Public Library.

Figure 2. Texas Colonisation Plan proposed by J.P. Spanier. Source: Archivio Storico Diplomatico, Ministero degli Affari Esteri (ASDMAE), Rome. Fondo Ambasciata Italiana a Washington, 1902–1912, b.170, f. 3814.

In 1905, on 5 January, Spanier wrote a long letter to Tommaso Tittoni, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, in which he mentioned his discussions with George Gould, Mayor des Planches and President Roosevelt regarding Italian immigration into the US. It underlined how ‘everyone agreed that immigration into US cities is detrimental for the United States and not recommended for the immigrants, since they could not find stable jobs’.Footnote 30 In the last part of the letter, Spanier supported a divergence of Italian migration to rural areas, where Italian peasants could achieve excellent results. In order to influence the Italian government to pursue this course of action, Spanier used a quite convincing rhetoric: he wrote that his objective was ‘to elevate the morale of the Italian emigrant peasants to take their place alongside other countries, in the agriculture of the United States, since they had the same, or even superior, agricultural skills’.Footnote 31

Conclusion: Italian-American socio-natures: the agricultural hub of Italianness

In a cookbook dedicated to the garden, the Italian writer and professor Angelo Pellegrini, who arrived in the US in 1914 when he was ten years old, captured a particular vision when he described his approach to gardening as utilitarian rather than ornamental: ‘When I use the word “gardening’’ my reference is invariably to the cultivation of those plants … that are used as food; and those … that are used to make food taste good, … my approach to gardening is fundamentally utilitarian’ (Pellegrini Reference Pellegrini1970, 4). This preference for useful gardening for food was paramount to Italian peasants’ livelihoods both at home and abroad. Gardening became a bridge to new surroundings, allowing a continuity of belonging to survive.Footnote 32 In the new contexts they found themselves in, useful gardening became an adjustment practice driven not only by nutritional necessity but by the desire to obtain certain ingredients: the vegetables, herbs and spices, the distinctly Italian flavours of their homeland like basil, tomato and garlic. In bringing homeland seeds to the US, by reading liminal urban spaces with this utilitarian gaze, and in rejecting state-driven (both from Italy and the US) attempts at agricultural colonisation, migrants from Italy were carrying out their own way of adaptation and resilience to the migratory experience: the Italianness performed through gardening helped Italians in the USA remember their distant homeland whilst shaping their new identities as Italian Americans.

This paper has focused on and developed the concept of agricultural diplomacy. This diplomacy revolved around both Italian and US governments agreeing that the most favourable outcome would be to direct new migrants and relocate urban migrants to rural colonies. The justification of this was done on agricultural lines. Focusing on perceived agricultural skill served not only to appease US negative popular opinion and state-level policies, but also the Italian government's desire to create Italianness abroad as a colonial project. The paper has considered the various and complex array of relationships which tried to transform Italian migrants from an urban problem to a skilled and desirable rural workforce. It looked at how attempts were made to lure migrants to southern states through offers of land to cultivate. At the same time, the Italian government activated institutional expertise to perform both scientific explorations and diplomatic journeys in the Americas in order to pursue plans to establish settlements with Italian emigrants, relocating them from cities to rural areas, which simultaneously found favour with US immigration policy and public opinion. Whilst establishing the concept of agricultural diplomacy, I wanted to illustrate how the environment emerged as a crucial actor in shaping this Italianness. It was the assumption that climatic similarity would lead to cultural familiarity that determined government policies to promote relocation and redirection to southern US states from cities, to transform undesirable immigrants into skilled citizens. The environment became crucial to this agricultural diplomacy, which shaped relationships between state policy, actors, workers and migrants. The framework of agricultural diplomacy may be useful when revisiting other relationships between Italian migration and Italian foreign policy, not only in other timeframes within the US context but in other migratory and diplomatic contexts. Furthermore, it may help us to understand current imaginaries of Italianness abroad as they stand today.

At the turn of the twentieth century, this agricultural diplomacy required the participation of both states. This essay aimed to unveil the intertwining of issues of colonialism and the active roles played by a multiplicity of actors, from governmental officers, railroad agents, lawyers, and agronomists. I wanted to express how the rebranding of Italian migrants through agricultural means was seen as beneficial to both states. Migrant bodies and their agricultural skills, were in turn disparaged, exploited, and celebrated. Italian urban migrants were labeled as dirty and their bodies as unfit, but they were also considered good market gardeners and appreciated as potential farmers. The same pattern affected different places, and thus the governmental policies and plans of both the US and Italy. The city was portrayed as an unhealthy place for southern European migrants (and thus a modern place for Americans only) and the countryside became a suitable environment for them. In between these two spaces, gardening emerged. Each character in this story developed a different discourse of Italianness: a political and expansionist opportunity for Italian diplomats, an administrative opportunity for the US authorities to manage their overcrowded cities, and a resilient practice of adjustment for Italian migrants.

These plans of relocation and redirection, from urban to rural, from problem to solution, from undesirable to desirable – justified through climatic and agricultural reasoning with complex arrays of actors and divergent discourses – ultimately failed. How and why they failed is another story, however one key component is that they failed to take into account individual agency and the immigrants’ desire to stay together in the urban Little Italies, forging a new hybrid yet still communal identity of American Italians, re-inscribing the city through seeing waste spaces as places to grow, and utilising this as an entry point to economic activity, as described in the opening sections. Arguably, by focusing on the structural components of creating and maintaining this agricultural diplomacy, the active roles played by Italian immigrants may have been neglected. While they were considered by both Italian and US authorities as passive subjects to be relocated, they chose instead to stay in the crowded cities or their outskirts. With their agricultural skills they created gardens and produced food that later became a characteristic of their new Italian-American identity. In this, they did not fail.Footnote 33

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank all the colleagues and professors with whom I discussed the matter of this article, and in particular Marco Armiero, Roberta Biasillo, Alessandro Bonvini, Marco Moschetti, Lucy Riall, Daniele Valisena, and Stéphane Van Damme. Furthermore, I am grateful to the editors of this journal and, lastly, to the anonymous peer reviewers for their remarks and comments.

Note on contributor

Gilberto Mazzoli is a PhD researcher in the Department of History and Civilization at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy. His dissertation, entitled ‘Portable Natures. Environmental Visions, Urban Practices, Migratory Flows. Agriculture and the Italian Experience in North American Cities’, explores the Italian migration to the US through the lens of environmental history, with a focus on urban agriculture in its manifold aspects: gardening as a resilient migrants’ practice and its relationship with the US urban spaces, and gardening as a tool used by diplomats and authorities to manage migratory flows.