Introduction: European museums, exhibitions and colonialism: an ongoing reflection

At the 2019 Venice Biennale, the Chilean pavilion exhibited the work of artist Voluspa Jarpa. Jarpa's exhibit Altered Views was divided into three parts: Hegemony Museum, Subaltern Portrait Gallery, and Emancipating Opera. The work challenged visitors to reconsider the very notion of civilisation (white, masculine, colonial) as understood by the West. For this paper, two aspects of the exhibit are particularly striking. In Jarpa's vision, the museum is a hegemonic space, identified as the place where hegemony was – and continues to be – exercised and exhibited by European countries. Moreover, at the entrance to the pavilion a panel displayed the words of sociologist Aníbal Quijano: ‘the Eurocentric perception of knowledge operates like a mirror, which distorts all it reflects’.

For years, European museums have been at the centre of a bitter controversy concerning their exhibits, which at best are seen as the fruit of an imperialist and colonialist culture by the exhibits’ nations of origin, and at worst, the ill-gotten gains of thefts and crimes perpetrated against the indigenous populations and inhabitants of the former colonies (Sarr and Savoy Reference Sarr and Savoy2018). In addition, the ways in which artefacts are presented has been heavily criticised. Racist and obsolete captions (Surge Reference Surge2007, 162), fictitious and instrumental labels, colonial toponyms, and arbitrary categorisations of tribes and populations created by colonisers for Western, classificatory, and repressive purposes (Turner Reference Turner2020) are still used in museums today (and elsewhere, Amselle and M'Bokolo Reference Amselle and M'Bokolo2008). The issue is by no means simple or minor, and involves not only museum curators but all those who work on and write about colonialism (Gouaffo Reference Gouaffo, Gouaffo, Götze and Lüsebrink2012). Museums, especially ethnographic museums, considered to be ‘contact zones’ (Pratt Reference Pratt1992; Clifford Reference Clifford and Clifford1997) and spaces of colonial encounters par excellence, have been the subject of dedicated study and serious scrutiny by historians, museologists, and curators for the past 30 years (Macdonald Reference Macdonald1998; Philips Reference Philips2005; Boast Reference Boast2011). The new museology, which emerged in the 1990s and developed in the early 2000s (Assunção dos Santos Reference Assunção dos Santos, Assunção dos Santos and Prima2010), has vigorously confronted the colonial and post-colonial museum, questioning exhibition methods, the acquisition of objects, curatorial choices regarding what to include in the exhibition and what to leave in the storerooms, the involvement of the public, and the educational impact and value of such museums.

In Italy, the material remains of colonialism are visible (Labanca Reference Labanca1992; Tomasella Reference Tomasella2017; Troilo Reference Troilo2021), but ignored and elided from the national consciousness. Italy has ‘struggled to grasp colonialism in an appropriate manner and in all its complexity’ (Calchi Novati Reference Calchi Novati2011, 13) perpetuating false notions of Italian exceptionalism (Benigno and Mineo Reference Benigno and Mineo2020), which has long excluded Italian colonialism from ‘transimperial’ studies (Hedinger and Heé Reference Hedinger and Heé2018). Many aspects of the historical collection and exhibition of artefacts from the former colonies, which offer such fertile ground for studies, comparisons, and reflections within a broader European context, are also under-researched. As Carter and Martin have pointed out, the way in which a society relates to its heritage (even, and especially, if it is ‘difficult’ or ‘inconvenient’) is the best indication of how that same society has metabolised, understood, and come to terms with the past that material heritage represents (Carter and Martin Reference Carter and Martin2017).

The collections displayed in temporary exhibitions are particularly valuable for historical analysis. In contrast to museums, collecting for exhibitions is a purposeful activity, as objects are especially ordered and commissioned for display (Ter Keurs Reference Ter Keurs and Keurs2007, 1). Although held in the Trocadéro Museum of Paris, one of the most important colonial museums in Europe, the 1934 Expo du Sahara, the object of this paper, was a temporary international colonial exhibition that was very purposeful in its organisation and, as we shall see, incorporated many other ‘collateral’ events, showcases, and conferences into its broader programme and agenda. The planning and realisation of the exhibition at the European level is interesting precisely from the perspective of the practice and history of exhibiting ‘the colonial’ in Europe.

Collecting and exhibiting the colonial: the Italian case study and transimperial analysis

From the mid-nineteenth century, a small but growing number of Italian soldiers, businessmen, explorers, naturalists, adventurers, and prelates ventured into Africa, each one driven by a unique and diverse agenda (Surdich Reference Surdich1982; Puccini Reference Puccini1999; Coglitore Reference Coglitore2020). While some travelled with clear scientific, mostly ethnological, interests, many had no preparation, education, or training, nor the necessary tools to collect information about African territories and populations, which still remained largely unstudied in a systematic way. This did not prevent them, in the classic positivist spirit, from collecting a wide variety of materials, choosing especially curious objects, drawing sketches of what they had seen (Bleichmar Reference Bleichmar, Jay and Ramaswamy2014), taking photographs, then writing and publishing travel memoirs when they returned home. Such artefacts, photographs (Palma Reference Palma1999) and later films (Mancosu Reference Mancosu2021), were considered irrefutable scientific data and not objects mediated by the opinions and training (or lack thereof) of those who collected them (Henare Reference Henare2005, 215; Tilley Reference Tilley, Tilley and Gordon2007, 5).

The acquisition of objects and artefacts intensified with the so-called pacification of Libya (1922–32) and the brutal conquest of Ethiopia (1935) and proclamation of Empire (May 1936) (Labanca Reference Labanca2002). Consequently, there was an increase in publications about the colonies, donations of memorabilia to Italian museums, and scientific missions specifically organised by geographical societies to increase knowledge of these distant places and peoples. African artefacts resulting from thefts, exchanges, purchases, and scientific missions (Wellington Gahtan and Troelenberg Reference Wellington Gahtan, Troelenberg, Wellington Gahtan and Troelenberg2019) flooded into Italian museums and temporary exhibitions (Castelli Reference Castelli and Cerreti1994). The ever-expanding collections of the Italian colonial museums took on characteristics and valences informed by the political, economic, and intellectual conditions Italian explorers and scientists found themselves operating in. The economic weakness underlying the colonial project (Maione Reference Maione and Del Boca2001; Podestà Reference Podestà2004; Gagliardi Reference Gagliardi2016) and the relative youth of the Italian national project, which contributed to Italy's position as the ‘least of the great powers’ (Bosworth Reference Bosworth1979; Labanca Reference Labanca and Rothermund2015), meant that the colonial terrain – and the representation of that terrain in Europe – became an opportunity for the country to present itself as the equal of the British and French empires. On a visual level, the confrontation took place during the great European exhibitions, which started in the mid-nineteenth century and continued until the outbreak of the Second World War, as well as smaller regional and local exhibitions. Italian participation in the major exhibitions was an important moment of nation building and credibility construction, both nationally and internationally (Misiti Reference Misiti1996; Bassignana Reference Bassignana1997; Baioni Reference Baioni2020; Carli Reference Carli2021). As Sandrine Lemaire noted, the presence of colonial sections in the many regional fairs and local exhibitions of that era deeply affected public opinion all over Europe (Reference Lemaire, Lemaire, Blanchard, Bancel and Thomas2013, 259).

In Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said reread the cultural archive ‘not univocally but contrapuntally, with a simultaneous awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts’ (Said Reference Said1993, 59). Following Said's theoretical concept of ‘counterpoint’, I believe it is necessary to investigate different imperialisms in counterpoint. The 1934 international exhibition in Paris dedicated to the Sahara, which was divided at the time between several colonial powers, was a watershed moment in the history of Italy's relationship to the rest of Europe. Rather than just being innovative from an exhibition or museological point of view, the Sahara exhibition was a political laboratory for the colonial partition of North Africa. And in this sense, after years of border disputes, it is interesting to interpret the event as an exaltation of the pacifying power of European colonialism.

Although this contribution will not address the question of post-colonial and decolonial museums, I believe that such work can nevertheless bring arguments for a European approach to the question of (post-)colonial display, to decolonial analyses of Italian culture, and to museum culture more generally.

An experiment in European colonial display: Italy at the Trocadéro and the colonial co-operation of 1934

The 1930s was a crucial decade in the history of Europe (Blom Reference Blom2019). It was a decade that witnessed increasing violence throughout the continent, and, in the Italian case, renewed colonial aggression in Libya and the Horn of Africa (Del Boca Reference Del Boca1991). It was also a particularly delicate decade for Italian diplomacy. Mussolini took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from Dino Grandi in the summer of 1932 and kept it until June 1936, when he handed it off to Galeazzo Ciano (Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Craig and Gilbert1953). At the beginning of the decade, Mussolini wanted Italian foreign policy to better reflect Fascist ideals of power and strength inspired by the Roman Empire (Scott Reference Scott1932; Cagnetta Reference Cagnetta1979; Burdett Reference Burdett2010), but once he became Minister, the changes were far less radical than promised and the Duce quite cautious.

In terms of collection and display, Silvia Cecchini noted that ‘the 1930s represented a watershed in the history of museology’ (Reference Cecchini and Catalano2014, 57), and Patrizia Dragoni and Giovanna Pinna have argued for the emergence of real ‘media propaganda’ through museums and exhibitions in the same period (Dragoni Reference Dragoni2015, 169; Pinna Reference Pinna2009). During the final decades of the nineteenth century, exhibitions devoted more and more space to the colonies, with their reconstructions of so-called Oriental-style buildings, bazaars, and ethnographic villages (Lemaire and Blanchard Reference Lemaire, Blanchard, Lemaire, Blanchard, Bancel and Thomas2013). In many cases, temporary exhibitions gave rise to the creation of museums (e.g. the former Museum of Manufactures in London and the Musée du Congo Belge in Tervuren) which allowed the public to enjoy the collections on permanent display, thus making the museum one of the preferred places for the education and nationalisation of the masses. However, large-scale temporary exhibitions, where the public could explore their nations’ colonial empires without having to go there, was the most effective tool in reaching the popular classes and conveying propaganda (Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh1988; Pellegrino Reference Pellegrino2015). Mario Gennari wrote that ‘to survive, a culture needs exposure. This is ensured by the so-called Great Events’ (Reference Gennari2012, 602). It was precisely such ‘great events’, temporary exhibitions rather than permanent museums, that achieved considerable success in the first half of the twentieth century, attracting a large, heterogeneous and undemanding public.

In Italy, exhibitions ran parallel to the processes of national unification, accompanying the transition from the liberal era to Fascism. The 1891 Italian National Exhibition was held in Palermo, the first in southern Italy, organised with the support of Francesco Crispi, and hosted a special section dedicated entirely to the Eritrean colony. In 1906, the Great Expo of Work was held at Parco Sempione in Milan hosting fine arts displays, industrial and engineering exhibits, along with foreign pavilions. The International Exhibition of Art was a world's fair held in Rome in 1911 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the unification of Italy, marking the beginning of the National Roman Museum. In the same year, another world's fair was held in Turin, which focused more on science, technology, industry, and labour. In 1914, the world's fair International Exhibition of Marine and Maritime Hygiene was held in Genoa with the aim of depicting life in Italian colonies, including the newly conquered Libya. In the 1920s, colonial-themed art exhibitions intensified, both in Italy and abroad.Footnote 1 In 1932 the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution was a popular and critical success, attracting over 2,800,000 visitors in its two-year run (Stone Reference Stone1998; Picone Petrusa, Pessolano and Bianco Reference Picone Petrusa, Pessolano and Bianco1998; Della Coletta Reference Della Coletta2006; Massari Reference Massari2011; Abbattista Reference Abbattista2013).

Preceding the Exposition du Sahara, Italy participated in the important 1931 Exposition coloniale internationale et des pays d'outre-mer, also in Paris, which included European powers as well as the United States and Japan. On this occasion, Italy displayed ‘the myth of empire’ by playing with the concepts of Latin identity and the Roman past (Carli Reference Carli2004). The Italian exhibition reproduced the Basilica of Leptis Magna surrounded with pools and obelisks inspired by ancient Rome and white-domed marabouts typical of Libya. Meanwhile the pavilion dedicated to Rhodes (an Italian colony since 1912) recalled the island's medieval past and was inspired by the buildings of the Knights of Malta (Guide officiel de la section italienne a l'Exposition coloniale Paris 1931, 12–13). Through its exhibits, in fact, Italy proposed a reinterpretation of its past, both distant and recent, in a colonial key, thus standing in its own right as a colonialist nation on par with France, Britain, and Portugal. The 1931 Parisian event prepared Italy's participation in the Exposition du Sahara three years later, a thematic exhibition dedicated to the well-circumscribed area of North Africa. While the 1931 exhibition also included Japan and the United States, the 1934 exhibition had a much more precise focus, as evidenced by the chosen location of Paris’ ethnographic museum.

The Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro (MET) was established in Paris in 1878 by the Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale, with the official name of Muséum ethnographique des missions scientifiques (De Watteville Reference De Watteville1877), and was housed in the Palais du Trocadéro, built for the Exposition universelle of the same year (Exposition universelle de 1878. Description complète et détaillé des palais Champ de Mars et du Trocadéro 1897). Initially configured more as an institution dedicated to research than to colonial propaganda (Dias Reference Dias1991), due to the efforts of assistant director Georges Henri Rivière (1897–1985), the Trocadéro was modernised in the spirit of creating ‘a museum of public education to seduce the colonial Republic’ (Grognet Reference Grognet, Delpuech, Laurière and Peltier–Caroff2017, 103). Reorganised in 1931 (Rivet and Rivière Reference Rivet and Rivière1931), the museum was one of the key institutions for the articulation of French colonial culture, and a model for all others (including Italy).Footnote 2 The Exposition du Sahara was held at the Trocadéro, 15 May–28 October 1934 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Poster of the Exposition du Sahara at Trocadéro; Archives du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris.

It was a moment of cooperation between the European colonial powers (including Germany, despite the loss of its colonies following the First World War), celebrating their military and technological superiority. They had, according to their narrative, explored, mapped, conquered, and now, finally, exhibited what was perceived as the fascinating and mysterious territory of North Africa, now entirely controlled by colonial powers (Guide Illustré Exposition du Sahara 1934). In fact, such control was a recent development. During the 1920s, the so-called ‘pacification’ of the French Sahara had been consolidated (Brower Reference Brower2009), and in the first months of 1930 the ‘pacification’ of the Italian Sahara was completed with the reconquest of Fezzan by Badoglio and Graziani, and the capture of Cufra in 1931 (Graziani Reference Graziani1934).

The exhibition, organised by the Musée du Trocadéro in collaboration with the colonial government of Algeria and various French ministries, was inaugurated by the Minister of Colonies, Pierre Laval (Dépȇche Algerienne 1934) was visited by over 66,000 people,Footnote 3 making it the most successful event in the museum's history (Conklin Reference Conklin2013, 217). The exhibition occupied eight rooms: two of its largest sections were devoted to Italy and France, the real protagonists of European colonial action in the Sahara; smaller spaces were allocated to German and English colonisation and exploration. The circular design of the Trocadéro could be understood as a form of Foucault's panopticon (Bennett Reference Bennett1988): visiting the museum one would find ‘response to the problem of order, but […] seeking to transform that problem into one of culture – a question of winning hearts and minds as well as the disciplining and training of bodies’ (Bennett Reference Bennett1988, 76), combining politics, educative exhibition, and entertainment. The exhibition was born out of an assumption of European colonial collaboration, following a period of international tension.Footnote 4 While many of these tensions remained unresolved – the invitation to participate in the exhibition arrived at the Italian Ministry of Colonies on 20 October 1933, and at the Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin a month later,Footnote 5 despite the fact that Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of the Reich in January 1933 and had withdrawn Germany from the League of Nations in October – they were put aside in the face of the ‘civilising’ task in Africa, for which it was deemed necessary to create a united front:

There exists among the colonial powers a kind of common sense or feeling that one might well call ‘Saharan solidarity’. Just as there is a bond of camaraderie and a spirit of cooperation among aviators and seafarers, whatever nation they belong to, so there is a bond of camaraderie and a spirit of cooperation among Saharans, whether they be soldiers or explorers, officials or scholars (Italia Coloniale 1934).Footnote 6

The exhibition was intended as a colonial propaganda event, both scientific and popular, which documented the anthropology and ethnography of the Saharan peoples, displayed examples of medieval cartography, highlighted archaeological, palaeontological, and mineralogical discoveries, and exhibited specimens of natural history, while also playing on the visitors’ exotic imagination. The fascination with the Tuareg (Fig. 2), present in the form of both mannequins and flesh-and-blood ‘extras’, the presence of African troops from the various countries, and complementary events such as Une soirée au Hoggar (17 March 1934) organised by the Société des amis du Musée du Trocadéro at the Hotel Georges V, were each inspired by popular exotic themes, such as a fascination with the desert, its dangerous flora and fauna, and the nomadic life of the people who inhabited it (Excelsior 1934).Footnote 7

Figure 2. A showcase dedicated to Tuareg clothing in the French section (PP0001359); Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

At the Trocadéro, Germany displayed the results of Gerard Rohlfs’ explorations, while France exhibited the gifts of Henri Duveyrier, loans from the Musée du Bardo in Algiers and objects from the M'zab region in southern Algeria collected by Lieutenant d'Armagnac, as well as the original diary of Saharan explorer René Caille (1799–1838) (France Afrique 1934). In this regard it is interesting to note that in 1933, in preparation for the exhibition, the Trocadéro museum circulated instructions to colonial officials for the collection of material to be sent to Paris entitled Exposition du Sahara: Note sur les instructions detaillées pour le rassemblement des documents et objets ethnographiques.Footnote 8 These insisted on the ‘purity’ of the objects and the need to search for ‘authentic’ artefacts, free of European influence. It was not the Saharan society of 1933 that French colonial officials were charged with representing, but rather an idea of Saharan society as it existed before the French occupation, which could capture the public's imagination and crystallise a rapidly declining culture.

As far as the Musée was concerned, the exhibition was a success and with the materials collected it was able to inaugurate a new hall:

As far as White Africa is concerned, the new hall was opened on the occasion of the Sahara Exhibition, in which Mr Conrad Kilián (Director), Mr Henri-Paul Eydoux (Secretary General) and Mr Eric Lutten (Commissioner) collaborated as members of the Organising Committee. Conceived on an international level, this exhibition, which remained open from 15 May to 28 October 1934, was a great success; among the foreign sections, the Italian section was particularly noteworthy (Leiris Reference Leiris1934).

Positive reviews of the Italian section (Fig. 3) were picked up and amplified by the Fascist press in Italy (Fig. 4):

The Italian Exhibition was, by unanimous recognition, the most interesting and instructive […] In the Information, a specialist in African affairs, the writer and explorer Henry De Munfreid, acknowledged that Italy's contribution to today's exhibition was undoubtedly the most valuable of all (Corriere di Napoli 1934).

Figure 3. The entrance to the Italian section of the exhibition (PP0001204); Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Figure 4. Il Giornale d'Italia, 5 June 1934; Archives du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris.

The display of the materials and the organisation of the Italian section of the exhibition had been prepared by the Museo Coloniale of Rome (Falcucci Reference Falcucci2021), which had coordinated the loans of materials from other Italian institutions and museums (Zoli Reference Zoli1934a) and produced an illustrated guide of the section for the occasion (Le Sahara Italien. Guide Officiel de la Section Italienne 1934). Umberto Giglio, director of the Museo Coloniale and head of the Italian organising committee, had asked for a larger space than that granted to the other colonial powers,Footnote 9 thus creating an exhibition that could challenge that of their French hosts (Corò Reference Corò1934). Italy organised its section to celebrate ‘the fascinating desert tracks of the Sahara on which Fascist Italy revives trade and restores life’ (Il Popolo d'Italia 1934) with frequent references to Libya as an ancient Roman province (Dorato Reference Dorato1934), whose Fezzan rock graffiti (Fig. 5) and archaeological remains Italy had discovered, restored, and protected, returning them to their former glory (Il Giornale d'Italia, 1934).Footnote 10 Christianity and the Christianising mission, which went hand-in-hand with the civilisation of the Saharan territories, was also underlined by the participation in the exhibition of the Catholic Missions, which made loans of documents and objects (L'Italia 1934).

Figure 5. Il Legionario, 23 June 1934; Archives du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, Paris.

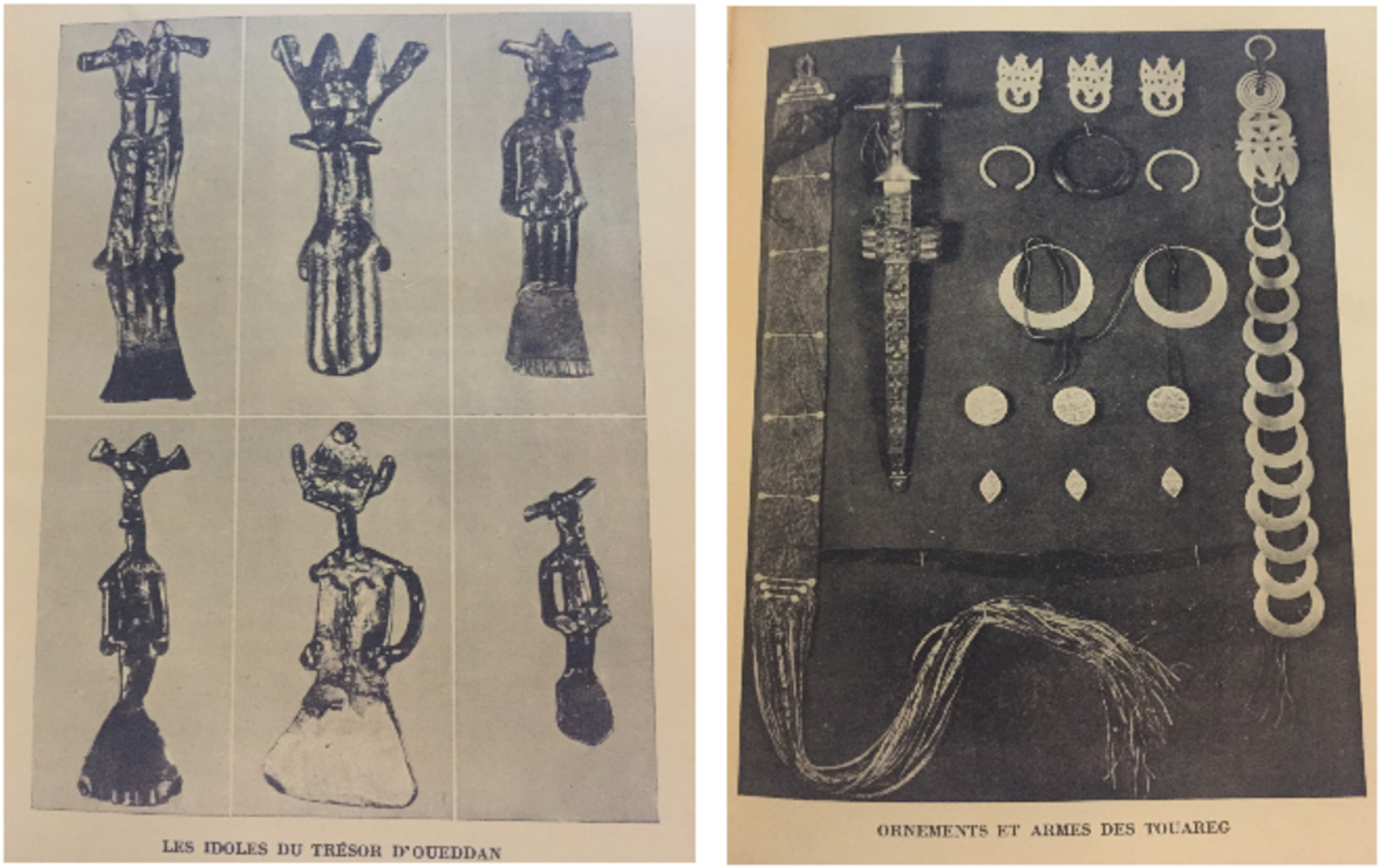

The emphasis was on ancient maps and scale models, well-lit and displayed in simple, standardised showcases as precious objects to accredit Italy as a colonial power, rather than as ‘curious’ ethnographic objects. Archaeological finds, mainly from Gherma, were restored and presented to the public: amphorae, funerary steles, and ancient pottery were arranged, illuminated, and described to enhance and highlight Italy's conservation efforts. At the same time, pictures of military operations and aerial photographs testified to Italy's final conquest of the Libyan Sahara. Ethnography was not completely excluded from the exhibition, but compared to the past, the choice of objects was aimed at exalting their manufacture (Fig. 6). This is the case of the so-called ‘treasure of Ueddan’ from Tripoli's museum (Falcucci Reference Falcucci2020): a series of more than one hundred objects, idols, ornaments, and gold jewellery (Le Sahara Italien. Guide Officiel de la Section Italienne 1934, 53–4). Thus, the display distanced itself from some of the earlier colonial exhibitions, mainly aimed at the creation of an Italian orientalist and exotic imagery, adhering instead to the ‘modern’ museological principles that would be set out at the Madrid conference a few weeks after the opening of the Paris exhibition.

Figure 6. Manifactures of the peoples of the Italian Sahara; Guide Illustré Exposition du Sahara, 1934.

The committee for the organisation of the Italian section was composed of colonial officials like Umberto Giglio and Enrico Cerulli, while the scientific committee included scholars such as Armando Maugini, Nello Puccioni, Ardito Desio, Raffaele Gestro, Saverio Patrizi, Edoardo Zavattari, and Lidio Cipriani (whose plaster face casts and anthropometric photographs were exhibited). Institutions including the Istituto Geografico Militare of Florence (IGM), the Accademia d'Italia, the Museo di Antropologia e Etnologia of Florence, the Istituto botanico of Pisa, the Società Geografica Italiana (SGI) of Rome, the Istituto Agricolo Coloniale Italiano (IACI), as well as the colonial governments, took part in the exhibition (Le Sahara Italien. Guide Officiel de la Section Italienne 1934, 8–10). The Italian pavilion displayed the results of the geological and naturalistic explorations carried out in the early 1930s by Desio and Patrizi under the auspices of the SGI, the mapping of the territory by the IGM, and the archaeological results of the Sergi-Caputo mission. Corti and Scortecci, who had just returned from Fezzan, together with Monterin and Tedeschi returning from Cufra, presented a preview of the latest results of the scientific expeditions sponsored by the SGI. News was also given of missions still in progress: alongside the geographers Elio Migliorini and Emilio Scarin, Francesco Beguinot was still in Fezzan on behalf of the SGI with the aim of carrying out linguistic research (Le Sahara Italien. Guide Officiel de la Section Italienne 1934, 17–18). A geological map of Libya and an album of photographs donated by Ardito Desio were on display along with geological samples (in particular from the Saharan oases of Kufra e Djialo), illustrating the richness of Libyan natural resources that Italy would be able to exploit.

A cycle of conferences complemented the Italian exhibition.Footnote 11 A screening of a silent film about the Italian capture of the oasis of Jufra (Centola Reference Centola1934) at the Société de Géographie was accompanied by a talk by Corrado Zoli, journalist and former governor of Eritrea. Archaeologist Biagio Pace, a collaborator of Caputo, also gave a lecture entitled Les Fouilles du Fezzan at the Institut d'Ethnologie.

These conferences and invited talks were emblematic of a period of Italo-French ‘colonial cooperation’ after decades of tensions on the Saharan border (Tittoni Reference Tittoni1927; Salvati Reference Salvati1929). It was a very short period if we consider that only a year after the exhibition Italy would invade Ethiopia, ending the moment of colonial cooperation and placing France and Britain in clear opposition to Mussolini's expansionist ambitions (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1999). Until early 1935, the British and French saw Italy as a nation committed to collective European security and had signed a series of agreements that seemed to indicate genuine international cooperation, but Italy's invasion of Ethiopia and rapprochement with Germany changed this (Quartararo Reference Quartararo1980; Salerno Reference Salerno, Alexander and Philpott2002).Footnote 12 Even at the exhibit in 1934 there was also a certain amount of competition among European nations in the scientific and exhibition fields. Italy was very eager to make a good impression in Paris and did not hesitate to use its best ‘weapons’.

Through the Italian section of the exhibition, Fascism sought to highlight the presence of Italian explorers in the Sahara, trying to build legitimacy for the recent brutal conquest of Libya that had just been completed (using hangings, gas, and deportations. Salerno Reference Salerno1979, Rochat Reference Rochat1991, Volterra and Zinni Reference Volterra and Zinni2021). Besides rich ethnographic material (Le Sahara Italien. Guide Officiel de la Section Italienne 1934, 72–6), the Italian section presented rare examples of ancient cartography (Fig. 7). Ancient maps of the North African region produced by ‘Italians’ such as Stefano da Monte Oliveto in 1578 were exhibited, as well as the 1325 planisphere by the Genoese Giovanni da Carignano and the famous world map by Fra Mauro of 1467, lent by the SGI for the occasion (De Agostini Reference De Agostini1958, 18). The Sahara was presented as an area that had always been known and studied by the Italians, who had finally ‘returned’ to it. In this narrative, the ancient Romans were likened to the Italians of the 1930s, and maps of their penetration into the Sahara territories were also displayed. Fascist Italy, in fact, intended to illustrate its destiny of Mediterranean domination, heir to a glorious history of supremacy over the sea reaching from ancient Rome, through the Maritime Republics, to 1934.

Figure 7. Section italienne. Cartographie ancienne (PP0001191); Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

At the Trocadéro, France, Britain, and Italy all presented themselves as ‘pacifying’ powers, and Italy was pleased to finally be fully integrated into the assembly of European colonial powers. In January 1935, Giglio wrote to Rivière:

The magnificent days of the Franco-Italian conversations have made me think that the Sahara Exhibition probably served some purpose in the political field as well. The words pronounced on that occasion by Minister Laval to Italy and the Duce certainly had a significance that went beyond the contingency of the moment.Footnote 13

Beyond the competition between nations, the exhibition celebrated the evident dominance of European technology over ‘hostile’ African nature (Cattaneo Reference Cattaneo1934), the ordering European spirit, politically and intellectually, as well as the ‘collective’ colonial experience which collapsed the significant differences between states and the heterogeneity of the subjected territories (Tilley Reference Tilley, Tilley and Gordon2007, 3). Imperialism was thus presented in Paris as a necessary task and burden for which Europeans collectively assumed full responsibility. Such an idea was, moreover, already very much present in the activity of the Institut Colonial International (ICI) in Brussels. France and Belgium were the most prominent members of the ICI, but Italy intensified its activities during the 1920s with Cerulli and Maugini, among others, representing Italy (Poncelet Reference Poncelet2008, 302–06).Footnote 14

The Sahara was again the protagonist at the second Mostra Internazionale di Arte Coloniale, held in Naples (October 1934–January 1935). The exhibition, organised by the Ente Autonomo Fiera of Tripoli, had been realised thanks to the collaboration between the Minister of the Colonies, Emilio De Bono, Umberto Giglio, art experts such as Ugo Ortona, architects known for their work in the colonies such as Florestano Di Fausto, and organisers of missionary exhibitions such as Pietro Ercole (Zoli Reference Zoli1934b). Belgium, Portugal, and France all participated, and Italy again presented a pavilion dedicated to the Italian Sahara, which for the most part reproduced the Paris exhibition (La Mostra del Sahara italiano. II Mostra Internazionale d'Arte Coloniale. Maschio Angioino-Napoli, 1934).

The international conference Muséographie, architecture et aménagement de musées d'art, in Madrid (28 October–4 November 1934) immediately following the conclusion of the Exposition du Sahara, represented a crucial moment for reflections on the organisation and layout of museums in Europe (and the United States). The conference took place just before relations between the European powers markedly deteriorated, with the growing political violence, the advent of the Popular Front in France and Spain and Italy's invasion of Ethiopia and the sanctions decreed by the League of Nations. It is precisely this peculiar temporal position that makes the conference so relevant and interesting on many levels. The debates were already at the heart of the work of the promoter of the Madrid event, the Office International des Musées (OIM), founded in Paris in 1926 (Dalai Emiliani Reference Dalai Emiliani2008, 13). Its official publication, Mouseion, which began in 1927, anticipated many of the topics that were later debated in Madrid and subsequently presented in the conference proceedings, providing an up-to-date repertoire of the topics of exhibition science and a decalogue for display (Ducci Reference Ducci2005).

For the first time in Madrid, Western museums, their exhibits, and displays, from art history to archaeology and anthropology, were compared in a systematic way. Everything, from the proper way to artificially light rooms to how to evaluate and record reactions and the visiting times of the public, was discussed. European and American museums were thought of as a web of institutions responding to the same needs, adhering to the same common principles and demands. Above all, beyond the discussion of innovative technical aspects related to displays in temporary exhibitions and museums, the Madrid conference confirmed the momentum of collaboration and encounter underway in the mid-1930s. It represented an actual theorisation of the encounter between diplomacy, culture, and museography that had already been successfully put into practice a few weeks before in Paris. The Madrid Conference was also the moment that sanctioned the birth of the term museography (Marini Clarelli Reference Marini Clarelli2011) and created the environment in which its subsequent semantic transformations developed up to the constitution of ICOM (International Council Of Museums) in 1946.

Of course, European colonial exhibition practices were already unified by the circulation of scientific works, of knowledge in the persons of scientists, curators, and museum directors, who visited different European institutions and expos and drew inspiration from each another, but also by structured moments of encounter such as the Exposition du Sahara. In fact, 1934 also saw the Congrès international des sciences anthropologiques et ethnologiques (CISAE) in London, which brought together over 800 European scholars to discuss modes of colonial administration, theories of race, and the need for an in-depth shared knowledge of the subject peoples (Pogliano Reference Pogliano2005, 52).

The case study of the 1934 Paris exhibition, as well as the Madrid and London conferences of the same year, were not marginal events in the larger panorama of European colonial and exhibition history. Indeed, these episodes should be read in the light of the complex intertwining of collaboration and competition between Italy and the other European powers in Africa (and beyond). In the search, momentary as it was, for a European ‘colonial concord’, museums and exhibitions emerged as a meeting place and battle ground for the European colonial powers, as well as an invaluable tool of imperial propaganda.

Collecting and displaying otherness as a means of European power and networking

Barbara Sòrgoni (Reference Sòrgoni1998, 41) pointed out how Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1789 indirectly led to the first crack in the biblically derived Hamitic theory, which held that European science and technology was superior to all others. The encounter of the French and Europeans with Egyptian antiquities posed an urgent question that had to be answered, namely how was it possible that races considered inferior could have given rise to such advanced societies? Benedict Anderson writes:

The prestige of the colonial state was accordingly intimately linked to that of its homeland superior. It is noticeable how heavily concentrated archaeological efforts were on the restoration of imposing monuments […] The timing of the archaeological push coincided with the first political struggle over the state's education policies (Anderson Reference Anderson and Anderson1991, 165).

Something similar happened in Ethiopia at the time of the Italian occupation. On finding themselves in front of the castles of Gondar, the Italians wondered about the nature of the civilisation that had produced them, clearly not as backward as had been touted. The solution was to attribute what was (in their opinion) architecturally ‘significant’ in Ethiopia to European influence: ‘what is sumptuous in the palaces of Gondar, in the convent of Quosquam, in the tower of Uoizerò Mentuab, is all Portuguese’ (Guida Reference Guida1941, 14).

The importance for the colonisers of studying the material culture of the colonised peoples, an essential stage in imposing lasting domination over them, is thus clear. Hence the need to study these peoples, catalogue their customs and habits, and theorise on their origins and ‘decline’ (Mazzolini Reference Mazzolini2005). Such hegemony, as Quijano sensed, could find representation in the exhibition. In the second half of the nineteenth century, several museums of a clearly colonial nature were established (often developing from pre-existing collections displayed at temporary exhibitions [Stocking Reference Stocking and Stocking1985]), which highlighted a growing concern with the themes of race and human variation, as well as a new preoccupation with the material ‘things’ of the colonial subjects.

The European colonial exhibition model, however, proved to be so pervasive that it could even be found on the African continent itself, where it survived long after the end of European rule. This is the famous case of the so-called ‘bushman diorama’ of the South African Museum in Cape Town, created in 1960 by assembling plaster casts made in the early twentieth century of farm workers and prisoners, which was supposed to represent a community of hunter-gatherers of the Khoisan ethnic group (Davison Reference Davison2018, Rassool Reference Rassool2015). It is, as Witz argues, a reconstruction of an invented cultural world, bringing together mythic elements of material culture from different times and geographic areas, selected intentionally to create an idealisation of the savage for (white) museum visitors in the years of racial segregation (Witz Reference Witz, Karp, Kratz, Szwaja and Ybarra–Frausto2006).

European museums and exhibitions have long been recognised as ‘tools of Empire’ (Headrick Reference Headrick1981), which presented imperialism as something necessary and race as something logical and obvious:

Historically, museums and other exhibitionary spaces have been crucial agents in constructing race […] Most familiar in this history are nineteenth-century presentations in natural history museums. Race was presented as a thing instantiated in the body, represented for the public through display of skulls, bones, brains, casts, photographs, and bronze busts, as well as graphs and charts that offered a quantitative, statistical dimension and authority to the otherwise visual logic of physical anthropology (Teslow Reference Teslow2007, 13).

New types of showcases were used to present sequences of objects. The use of graphic material inside them, consisting of drawings and photographs, the use of lights, the isolation or grouping of artefacts, can all be qualified as ‘emotional practices’, designed strategically to evoke feelings and convey objectivity (Griffiths and Scarantino Reference Griffiths, Scarantino, Robbins and Aydede2005). In the exhibition, visitors took part in a real ‘social drama’,Footnote 15 curated and coded in every aspect. Viewing the exhibition and participating in the event as a member of the audience implied citizenship and ‘identity’ to the spectator, who was technically, culturally, and biologically superior to the peoples on display. The ethnographic museum can be seen as a place where identities were (and still are) staged, of both the beholder and the beheld (Burke and Stets Reference Burke and Stets2009, 12). Barbara Melosh has argued that museums possess a ‘sanctifying voice’, through which they exert a powerful influence on the visitors’ judgement and opinion of the content of the exhibitions (Melosh Reference Melosh, Leon and Rosenzweig1989).

In this sense, the 1934 exhibition at the Trocadéro codified the way Europeans viewed and understood Africa (or at least North Africa), offering the public a setting in which to recognise themselves and an imagery by which to be impressed. An analysis of Italian participation in this event, therefore, is essential to understanding Italy within a European framework, denying its exceptionalism by placing its Fascist brand of colonialism alongside those of the other imperial powers. We know that, following the Four-Power Pact (July 1933) between Italy, Britain, France, and Germany, Mussolini wished for closer relations with France (Jarausch Reference Jarausch1965). At the same time, France and the other European powers also saw strategic opportunities in coming together and operating in an orderly way throughout their colonies and throughout the world. In this sense, therefore, the 1934 exhibition is exceptional in several respects: it took place in one of the most important and oldest colonial museums in Europe, it represented a moment of colonial harmony between the old and new European powers, renewed the practice of colonial display, and proposed a new way of doing museum diplomacy.

A final moment of Italo-French collaboration in the cultural sphere is to be found in the Mostra d'arte italiana at the Petit Palais and Jeu de Paume in Paris (May–June 1935), shortly after the creation of the short-lived and never implemented Stresa Front between Italy, France and Britain. Opened by French President Lebrun and Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, the French press described it as ‘a treatise on high art. A treatise of spiritual alliance’ (Le Tour 1935; La Stampa della Sera 1935).Footnote 16 The exhibition marked the peak of friendship and collaboration between France and Italy in the early 1930s, a relationship that the invasion of Ethiopia a few months later would compromise. Additionally, the exhibitions of 1934 and 1935 are signposts of the gradual transition in how exhibitions and events were organised in Fascist Italy. In contrast to the Expo du Sahara, the 1935 exhibition was organised under the aegis of the Under-Secretariat of State for the Press and Propaganda, later the Ministry of Popular Culture, and with it a further step was taken towards totalitarian centralisation (Fabi Reference Fabi2014).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of the manuscript and their many insightful comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank the Società italiana per lo studio della storia contemporanea (Sissco) for the grant offered me for the linguistic review of this paper. Finally, I would like to thank Matilde Cartolari for the many stimulating Florentine conversations about the topic of this article in particular and museology in general.

Competing interests

the author declares none.

Beatrice Falcucci is postdoctoral researcher in Contemporary History at the University of L'Aquila and is fellow at the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome (KNIR). She has earned a PhD at the University of Florence, undertaking research about the colonial collections in Italian museums. She has been Italian Fellow at the American Academy in Rome and won a scholarship from the Fondazione Einaudi. Her book on colonial collections in Italy is due out at the end of 2022.