Introduction

In October 1949, a steamer carrying caste Hindus and marginalized castes was about to set sail for India from Karachi when Pakistani police stopped it from leaving and detained approximately 200 people. The detained included labourers such as cobblers and ‘sweepers’ (workers who wielded brooms and handled dry solid and human waste—essentially sanitation labourers).Footnote 1 At that time, an Essential Services Ordinance was in place that classified sweepers as providing essential services.Footnote 2 In this instance, the Indian High Commission in Karachi used this Ordinance to secure the release of all the detainees, except for six who were sweepers. In the wake of this incident in which most of the 200 detained were allowed to leave Pakistan, the national government rapidly amended the Essential Services Ordinance to include other categories of labourers to block future departures of this kind.Footnote 3 The amended Ordinance also allowed the government to ban trade unions and forbade agricultural workers from forming unions.Footnote 4

This article focuses on Sindh province, particularly Karachi, which was its capital before Partition and the capital of Pakistan in 1947. A mixture of communities inhabited Karachi—colonial Karachi’s merchant communities included Sindhi Hindu Bhaibands and Shikarpuris, Europeans, Parsis, Ismaili Khojas, Jewish traders, Gujarati banias, and Kutchi Memons. Sindhi Muslims from various clans constituted the majority of the provincial governing class at the time of Partition. The growing port city was also home to migrant labourers from all over the subcontinent with widely varying linguistic, cultural, caste, and religious backgrounds, including migrant Dalit labour.Footnote 5

Partition did not divide the regions of Sindh and Uttar Pradesh. Yet, these regions were crucial sites of refugee movement, shaping conceptions of the status of minorities and citizenship.Footnote 6 As a result of Partition, many people in caste-oppressed groups, which included sanitation workers and agriculturists, were stuck in Sindh and appealed to the Indian government to be allowed to leave Pakistan and enter India. Questions about where these groups belonged and whether India would facilitate their evacuation were ‘under consideration’ for the whole of 1948 and 1949, as different Indian ministries continued to receive but dither over their appeals for help. This is not to suggest that marginalized caste groups who wanted to migrate did not ever succeed (many did cross the border),Footnote 7 but the available archival record is patchy, so we do not know for certain how many left Sindh, how many returned, and how many people Pakistan was able to stop as they tried to leave. What the evidence does show is that some were forced to stay behind. They are the subject of this article. The caste-oppressed groups attempting to exit Sindh were left to fend for themselves. Those who continue to cross the border from Sindh to India in the present still fight protracted and difficult battles for citizenship and welfare rights.Footnote 8

Historians of the South Asian Partition have chiefly understood it as involving the mass movement of people across international borders and in terms of their conditions of departure and reception. As Ravinder Kaur argues, in dominant upper caste Partition narratives, the archetypal Partition refugee is produced through the act of displacement and their religious identity. Mainstream narratives elide caste in experiences of migration and segregated resettlement schemes.Footnote 9 The ‘master narrative’ of Partition historiography followed suit, omitting ‘untouchable’ accounts.Footnote 10 More recent studies on migration and resettlement after Partition have highlighted how social class, gender, and caste mediated modes of travel and official ‘rehabilitation' schemes,Footnote 11 and shown how post-Partition permit and citizenship regimes shaped the category of ‘minority-citizen’ that emerged out of mass migration.Footnote 12 The literature on Karachi in the aftermath of Partition has concentrated on the immigration into the city of hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from India, the emigration of Hindu refugees from Sindh, and how these migrations helped define citizenship and provincial nationality in Pakistan.Footnote 13 This article takes a novel approach in shifting the focus from immigration to emigration control, as Pakistan’s new government decided to throttle the movement of caste-oppressed labourers and agriculturalists from Karachi and rural Sindh while simultaneously threatening their job security. I also examine the response to their petitions for evacuation in India, where they received a less than lukewarm response. Building on B. R. Ambedkar’s contention that marginalized castes were ‘more than a minority’Footnote 14 and Joya Chatterji’s work on ‘mobility capital’, immobility, and ‘stuckness’ in the aftermath of PartitionFootnote 15 as well as her suggestion that minorities in South Asia occupied a distinctly inegalitarian legal category of ‘partial’ citizenship,Footnote 16 I argue that the prevention of exit produced a forced or ‘bonded’ citizenship for caste-oppressed groups.

Chatterji contends that ‘bundles’ of ‘mobility capital’, consisting of predispositions, assets, resources, and competences, frequently derived from family and community histories of mobility, determined the paths of those migrating, how far and where they chose to go, and whether they stayed on or were stuck. Some minorities travelled only a short distance while others stayed on because of disability, duties of care, or other obligations. Gender, age, and caste shaped mobility. The mobility capital of the poor and those with low social status was limited. Some were reluctant to migrate, could not consider moving at all, or were only able to cross international borders long after Partition.Footnote 17 The marginalized castes in this article did not possess sufficient education, professional connections, capital assets, or robust enough networks—even if, as this article shows, they did possess ‘contacts’ and tried to make use of them—to help facilitate their evacuation from Pakistan.

At Partition, South Asian religious minorities emerged as a distinct legal category. They endured a peculiar form of citizenship Chatterji calls ‘partial citizenship’ as India and Pakistan removed minorities’ right to property and deprived them of their freedom of mobility and return. Who moved where and on what date dictated the formal entitlement to citizenship in India and Pakistan. Pakistan drafted its citizenship laws in 1951 and 1952, and India introduced its Citizenship Act in 1955. India denied citizenship to anyone who had ever immigrated to or resided in Pakistan, and took this trajectory to prevent the return of Muslim evacuees.Footnote 18 Similarly, Pakistan began to halt the return of Hindu and Sikh evacuees.Footnote 19 Both countries retreated from their initial commitments to protect the evacuee property of minorities as refugees occupied it and refused to vacate it. Footnote 20 Chatterji argues that the power of India and Pakistan over their minorities exceeded their sovereignty over ‘ordinary’ citizens.Footnote 21 South Asian minorities ‘have a form of citizenship which is profoundly inflexible’, inflicting on them a unique form of immobility.Footnote 22

From the perspective of oppressor caste-Hindus, Dalits (whom upper castes assign to the lowest rung of the caste hierarchy) have a ‘partial internality’ to Hinduism.Footnote 23 They are, as Charu Gupta explains, ‘both outside and within the pale of Hinduism: outside in that they were denied all the privileges of caste Hindus; within in the sense that their labor was essential for the maintenance of social structures’.Footnote 24 South Asian Muslims also adopt the social hierarchies of caste, leaving the most condemned occupations, such as sanitation labour, to marginalized caste Christians and Hindus and specific Muslim communities.Footnote 25 In B. R. Ambedkar’s analysis of the status of minorities and who constituted a minority for the Indian Constituent Assembly, he described the marginalized castes as ‘more than a minority’ reflecting his belief that the social and economic discrimination and deprivation imposed on caste-oppressed groups required them to have special safeguards over and above those provided for other minorities.Footnote 26 At the time of Partition, Dalits and other marginalized caste groups attempting to move across the border from Pakistan to India experienced an upper-caste-inflicted immobilizing partial citizenship not only as religious minorities. They suffered the ignominy of occupying both the status of a ‘non-Muslim’ religious minority, as well as the additional humiliations of an upper-caste-inflicted lowered social status, which made their position more precarious than that of other ‘non-Muslims’ who were also struggling with the upheavals wrought by Partition.

I discuss the status of two large and heterogeneous categories of marginalized caste groups. The first are Dalits, who worked as sanitation labourers, and the second are agriculturalists. ‘Bonded labour’ is generally used as a descriptor for forced labour. The vast majority of bonded labourers are from caste-oppressed groups. I use ‘bonded’ here to describe citizenship in the context of the marginalized castes forced to stay in Sindh as they were compelled to continue labouring in jobs they wanted to leave. Their inability to leave bound them to citizenship of Pakistan. Extending Chatterji’s arguments about mobility capital and Partition producing a form of partial citizenship for religious minorities and taking account of Ambedkar’s analysis of caste-oppressed groups constituting ‘more than a minority’, this article argues that ‘partial citizenship’ incorporated the perpetual political allegiance of ‘non-Muslim’ marginalized-caste groups, in this case, intending to evacuate but forced to stay behind.Footnote 27 The binding of the labour of minority marginalized caste groups to Pakistan and their enforced immobilization and nationalization produced a form of not only partial but bonded citizenship.

Some of the marginalized caste refugees, notably Dalits, identified themselves as Indian nationals as they or their families had migrated to Sindh from other parts of India. India and Pakistan placed religious minorities in a state of flux during the time it took to craft their citizenship laws, but, as this article will show, they decided the nationality of marginalized castes stuck in Pakistan at an early stage: Pakistan by refusing to let them emigrate, and India by its insufficient response to their pleas for help to evacuate. The prevention of exit and the imposition of nationality took away the possibility not only for marginalized castes to withdraw their labour and leave Pakistan but also to ‘withdraw from its political constituency’.Footnote 28

This article’s use of terms to designate castes is provisional and tentative.Footnote 29 Where the primary sources mention terms that marginalized castes reject today, such as the Gandhian ‘Harijan’, I have indicated that this is the case. Where a person uses a pejorative term—such as ‘Bhangi’—for self-description, I have retained it. The people in this story did not use the term ‘Dalit’ (literally: broken, scattered, crushed). Since then, it has come into use to describe, affirm, and assert a political, religious, social, and cultural identity, albeit not without contestation. I use Dalit to mean the set of ‘untouchable’ castes involved in sanitation labour. I also use the term ‘Scheduled Castes’ (previously categorized as ‘Depressed Classes’), an official category that the governments of India and Pakistan use to categorize marginalized castes.

‘Citizenship’ indicates the nation in which a person possesses a bundle of status, rights, and responsibilities, and the relationship between the individual and the state and among fellow citizens. ‘Nationality’ establishes a legal relationship of belonging with a particular country and establishes membership of a particular state vis-à-vis other states. In this article, I use them interchangeably.

The ‘right to leave’ and exit control in the global context

States decide who can claim citizenship within their territory and, from the point of view of social contract theory, assume the tacit consent of citizens who automatically gain it. An element of compulsion in legal citizenship is implicit under the prevailing international political order. As far back as the seventeenth century, social contract theorists Hobbes and Locke considered how and when one could leave a state. For Hobbes, the sovereign had the absolute authority to include citizens,Footnote 30 whereas, for Locke, ‘the right to expatriate oneself was a manifestation of self-governance and individual self-determination’.Footnote 31 More recently, scholars of international law and human rights have considered the ‘right to leave’ as part of the right to freedom of movement, and that there is a relationship between the right to leave and the right to liberty and freedom of association.Footnote 32 Caste-oppressed groups have already historically operated with these freedoms severely reduced. And, as Hume pointed out some centuries ago, the choice of the poor to leave is often non-existent; therefore, even the idea of tacit consent to the governing political authority to control movement cannot be real.Footnote 33 While it may be helpful to consider the range of political deprivations that may be imposed by the denial of the right to emigrate in the modern world, the focus on individual liberty and a state’s right to implement emigration and immigration restrictions do not capture the social structures that may dictate where a person is stuck and subject to forceful political assimilation.

Empire states attempted to prevent exit in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but modern nation-states are more successful in sealing borders to block legal entry and exit.Footnote 34 Different states experimented with regulating and prohibiting departures in the post-Second World War (Sartre’s play No Exit was also first performed in 1944).Footnote 35 Although Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized the right of a person ‘to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country’ in 1948,Footnote 36 various countries recognized this as a limited right. They saw ‘outstanding obligations with regard to national service, tax liabilities or voluntarily contracted obligations as some of the circumstances binding the individual to the Government’.Footnote 37 The Soviet Union instituted strict emigration controls, and from the late 1940s, emigration restrictions and no-exit policies were common as part of Cold War migration restrictions in Eastern Bloc countries such as East Germany, but they were also sometimes applied in the United States.Footnote 38 Issuing a passport was an exception that required extensive justification.Footnote 39 Often, the same countries involved in holding people captive were implicated in the expulsion of millions from their homelands ‘directly or indirectly’.Footnote 40 If a person managed to ‘illegally’ migrate abroad and acquire another citizenship, only their original government could release them from their first citizenship and could choose to possess the migrant in ‘the bonds of citizenship against their will’.Footnote 41

In the same period, just-emerged post-colonial governments set up systems of exit controls to prohibit emigration for a variety of reasons, often to preclude the loss of labour they perceived to be non-substitutable—to prevent ‘brain drain’ and the loss of technical expertise, as part of class and caste-inflected regimes of political, social,Footnote 42 and, as I will show, economic labour control. In Kashmir, among the plethora of oppressive measures the Indian state has continued to apply is the Jammu and Kashmir Egress and Internal Movement Control Ordinance,Footnote 43 despite challenges to it.Footnote 44 In the recent past, India has applied this law to Pakistani women who crossed the Line of Control and entered Indian-occupied Kashmir with their Kashmiri husbands, and whom the Indian government prevented from returning to Pakistan.Footnote 45 The Indian government has also tried to implement a colour-coded passport scheme to apply emigration restrictions to ‘undesirable’ emigrants deemed unworthy of the ‘honour’ of an Indian passport and travelling abroad as representatives of India, an idea that had a more extended genealogy of Indian emigration control and had the support of the British.Footnote 46

The parallel processes of the prevention of exit and the prevention of return as modes of political and social control are also evident in partitioned polities other than in South Asia, where mass migrations also occurred. After the partition of Vietnam in 1954, French and American military personnel promoted and enabled a mass migration to the South while the Viet Minh used force to detain people from leaving the areas it controlled.Footnote 47 Israel denies Palestinian refugees the right to return in contrast to Jewish immigrants, whom it categorizes as ‘returnees’ and to whom it gives citizenship.Footnote 48 While Israel kills and expels Palestinians, it has encouraged Jewish immigration and applied ‘moral and ideological pressure’ to discourage Jewish exit.Footnote 49 Israel subjects Palestinians who remain in the region to restrictive permit regimes controlling their ability to exit the occupied territories.Footnote 50 Certain Jewish communities were also impeded from leaving for Israel. Similar to the history discussed in this article is that of Yemeni Jews who belonged to a scavenger ‘caste’. They collected filth from towns from medieval times to 1949, and other Jews treated them as ‘untouchables’. When they tried to leave Yemen for Israel, the townspeople of Sana’a attempted to prevent their departure.Footnote 51 The history of the South Asian Partition and exit control, to which I now turn, is a part of this broader history.

Immobility as national policy in the aftermath of the South Asian Partition

The Pakistani leadership chose Karachi, the capital of the province of Sindh, as the capital of the new nation of Pakistan at the invitation of members of the provincial Sindh governmentFootnote 52 and because it had the necessary attributes for a country divided into disconnected wings by the massive landmass of India. Karachi was a financial hub with a well-established port. In the words of Chaudhri Mohammad Ali, who sat on the Partition council and oversaw arrangements for the new capital, it ‘was a clean modern town with a mild climate’ and, importantly, had airports, which ‘provided ready means of communication with East Pakistan and the outside world’.Footnote 53 In 1948, Pakistan separated Karachi from Sindh and administered it as a separate federal district.Footnote 54 As Sarah Ansari has shown, the relationship between provincial Sindhi politicians and the new centre began to sour as Sindhis felt marginalized in the new Cabinet and Constituent Assembly and were chafing at the loss of their erstwhile capital as well as its port’s income.Footnote 55 As hundreds of thousands of refugees made their way to the province from India, disputes arose between Sindhi provincial leaders and the centre about how resources would be deployed, who would pay for the resettlement of the refugees, and how many refugees Sindh could accommodate.Footnote 56

The Pakistani leadership itself sought to find ways to limit the arrival of more refugees. Outside of the planned evacuation and the ‘exchange of population’ for Punjab, both the Indian and Pakistani governments acted to stop further cross-border movement. The prime ministers of India and Pakistan, Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan, insisted with reference to their own countries that no other country in the world had to set itself up while facing such formidable odds in rehabilitating such vast numbers of refugeesFootnote 57 or coping with the scale of violence Partition had unleashed.Footnote 58 During and after the upheavals of Partition in August 1947, India and Pakistan produced a ‘common statecraft’Footnote 59 and worked ‘in tandem’.Footnote 60 At the Inter-Dominion Conferences of 1948, both governments ‘agreed that [the] mass exodus of minorities is not in the interest of either Dominion and that the two governments are determined to take every possible step to discourage such exodus in either direction and would encourage and facilitate, as far as possible, the return of evacuees to their ancestral home’.Footnote 61 The main aim of the Conferences was to reassure minorities that it was safe to stay where they were and, to that end, the Conferences agreed that the two countries would set up minority and evacuee property management boards composed of minorities to safeguard their ability to stay home. As Chatterji writes, India and Pakistan displayed a ‘Canute-like hope of reversing the tide’ of refugees.Footnote 62 Neither government was able to keep its promise to protect evacuee property from refugees who occupied and refused to leave it, successfully forcing a change of government policy that made it very challenging for those wishing to return to go back to their homes. The introduction of a system of permits, the eventual introduction of harsh visa and passport regimes in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and restrictive citizenship rules made cross-border movement much harder.Footnote 63 The official desire to implement an immobilizing regime to stop people in their tracks as they fled or tried to return was plain.

The violence that had torn through Punjab did not affect Sindh to the extent it had in its northern neighbour. However, the situation in Punjab heightened minorities’ fears and influenced their decisions to quit Sindh. Communal violence afflicted Sindh towards the end of 1947 and in January 1948. Yet, minorities who could, began to leave well before this violence occurred.Footnote 64 The closure of shopsFootnote 65 and the movement of capital was one of the first signs that Hindu merchants were planning to emigrate from Sindh,Footnote 66 sparking panic about unemployment.Footnote 67 Neither the Indian nor the Pakistan governments viewed these migrations with favour. Pakistan suspected Sindhi Congressmen of leading a campaign to encourage Sindhi Hindus as well as Dalits to leave so as to jeopardize the economic stability of Pakistan.Footnote 68

Dalit labour as capital and national wealth

Omprakash Valmiki opened his history of the Valmikis, Safai Devata (Gods of Cleanliness), thus: ‘How surprising it is that the man who keeps society neat and clean counts even lower than dogs and cats in the same society which he makes liveable. What could be a bigger irony than this, that what is most useful for society is the same which is inferior and worthless.’Footnote 69 Oppressive inclusion and exclusion and social and economic immobility are inherent in the hierarchies of caste. Under colonial rule, certain caste groups became associated with particular forms of labour. Dominant colonial understandings of ‘traditional’ caste groups were not always accurate.Footnote 70 As urban areas expanded and the colonial state penetrated rural areas, Indian labour regimes and caste’s relationship to occupation were sometimes transformed. In collusion with upper castes, the state locked some castes into particular professions; colonial administrators justified this practice by citing caste culture, even if there was little link between the caste’s historical labour and the modern profession. A large proportion of the Bhangi caste, who have now rejected this name in exchange for Valmiki or Balmiki, were employed as landless field workers until the 1880s when those who relocated to the cities joined the sanitation industry, where they were thereafter cast in the role of sweepers and sanitation labourers.Footnote 71 However, there is evidence that some castes, such as Chuhras and Doms, collected waste for much longer, with this connection pre-dating the British era.Footnote 72 By the time we get to Partition, Valmikis were largely locked into the labour of sweeping and manual scavenging, and expected to remain stuck both to occupation and to the nation they were in despite the mass migrations of religious minorities all around them.

Another feature of the colonial period that persisted into post-colonial South Asia and is, thus, worth recalling for our purposes is the criminalization of ‘wandering’ and itinerant groups classified as ‘criminal tribes’, who were relocated to and confined to specific areas.Footnote 73 Criminalized tribes, a contingent category, were later subsumed under the category of ‘Scheduled Castes’.Footnote 74 In post-colonial India and Pakistan, the new states maintained or reworked the institutions involved in implementing the colonial Criminal Tribes Act (CTA), even after its repeal, in legal regimes and welfare policies, including in the regulation of refugees.Footnote 75 In the transition to post-colonial state sovereignty after Partition in 1947, in a post-war economic climate when control over the economy and economic resources was paramount for the new nations, India and Pakistan configured minority citizens as a category of economic citizen, subject to particular forms of ‘law and order’.Footnote 76 This was, additionally, an extractive socioeconomic sovereignty when seen through the lens of caste—when the control of mobility and forced belonging underscored exclusion and emplaced exile.

India and Pakistan faced severe economic challenges at their birth. However, Pakistan had several more obstacles to overcome. It had to set up a state from scratch from its base in Karachi, as much of the existing apparatus of governance fell on the Indian side. For instance, the Reserve Bank of India, which acted as Pakistan’s Central Bank, was slow to release funds to Pakistan.Footnote 77 The Sindh provincial government, in the meanwhile, had made plans for extensive post-war development schemes.Footnote 78 Fearing economic collapse, it began to enact ordinances on its own behalf, as well as that of Pakistan’s, to prevent the economically significant Hindus from leaving.Footnote 79 They found ways to leave anyway. After communal riots broke out in Karachi in January 1948, the Indian government organized an official evacuation for minorities from Sindh,Footnote 80 and the Pakistan government did not manage to stem the exodus of bankers and traders.Footnote 81 Among those leaving were also people who cleaned sewers. Muhajirs (refugees/migrants) had criticized government attempts to get Hindus to stay,Footnote 82 but in February 1948, the newspaper Dawn began publishing letters and articles from residents of Karachi who complained that ‘Asia’s cleanest city’ had become a cesspit.Footnote 83 Rubbish covered the roads that sweepers had washed daily during colonial rule, and boys could no longer swim or fish in the clear waters of the streams that had become sewers.Footnote 84 Karachi could no longer bear the stench. Throughout February 1948, the Government of Pakistan printed reviews of its performance in Dawn. In its review, the Interior Ministry announced:

Lately in view of the apprehended blow to the social and economic structure of the province as a result of the wholesale migration of depressed classes, the Government of Sind have been compelled to take legal powers to slow down the migration of such persons who in their opinion constitute the essential services of the province.Footnote 85

Here again, these events unfolded differently in Sindh and Punjab. An Indian fact-finding committee for Punjab noted that while there was enthusiasm to get rid of landholders so the land could be divided among Muslim refugees, there was less readiness to allow the ‘migration of the kamins (menials) and the Harijan non-Muslims for they could be useful slaves of the community’.Footnote 86 Ravinder Kaur has shown that there was a mixed picture: some marginalized castes wanted to leave West Punjab, Indian officials coaxed others to ‘evacuate’, and some stayed behind.Footnote 87 The Indian government managed to evacuate marginalized caste refugees who wanted to leave Punjab in May 1948 towards the end of the planned evacuations for that province.Footnote 88 Meanwhile, in 1947, the Pakistan government had resurrected the colonial Essential Services (Maintenance) Ordinance of 1941 to prevent people deemed to perform ‘essential services’ from leaving for India. Resurrected, and through a process of amendments, the Ordinance was more successful in keeping behind Dalits in Karachi who fell under its purview. The ‘more than a minority’ status of Scheduled Castes stuck in Sindh and their lack of mobility capital was clear, as long after lakhs of caste Hindus had left Sindh, the issue of their desire to migrate to India remained under negotiation between the governments of the two states after Pakistan began to prevent their leaving.

The Indian high commissioner to Karachi after Partition was Sri Prakasa, from Uttar Pradesh. The High Commission was by no means a nonpartisan operator.Footnote 89 Like Pakistan, Sri Prakasa wanted to retain certain skilled labourers for India. He wanted to issue permits to skilled Muslim weavers of Banarsi silk saris and fabrics (in the face of resistance from his deputy) to return to his home city of Benaras, as he did not want the city to lose the art that had made it famous,Footnote 90 but otherwise advised the Indian government to discourage the return of Muslim refugees to India.Footnote 91 He regarded Scheduled Caste labourers as Hindu and worked to secure their evacuation—the Pakistan Ministry of the Interior suspected him of distributing ‘money to servants, malis [gardeners], dhobis [washermen] and sweepers to pay their fare by ship to Bombay’.Footnote 92 These suspicions were not unfounded, as we shall see.

Sri Prakasa attributed the passing of the Essential Services Ordinance to the departure of non-Muslim migrant labourers and domestic workers from Uttar Pradesh, his home province. He recalled in his memoirs that for a very long time, many people ‘from our Uttar Pradesh’, especially the eastern regions, travelled to western India in search of work. Thousands of men from Sultanpur, Jaunpur, Benaras, Ghazipur, and other areas travelled to Ahmedabad, Bombay, and other locations to work in factories and other jobs. Their wives and children stayed at home. Every year, their employers granted them one month off. They visited their communities during that time to meet their relatives. They led uncomfortable lives, living alone in far-off cities and sent what little money they could save to their homes to pay off rents for their farms and their debts to moneylenders. They also flocked to Karachi in significant numbers before Partition.Footnote 93 Sri Prakasa and Liaquat Ali Khan were old acquaintances. Liaquat had grown up in Punjab, but his aristocratic family maintained their ancestral ties to Muzaffarnagar, the constituency Liaquat had represented in the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Council.Footnote 94 Sri Prakasa appealed to this history and recounted his meeting with Liaquat on the issue of the Pakistan government stopping the labourers of Uttar Pradesh from leaving as follows:

When all such Hindu workmen of Uttar Pradesh also started leaving from Karachi, then the Essential Services Act was brought into operation, and orders were issued that labourers, domestic servants of government officers and such others could not go away … I met Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan, and said to him that it was an old custom with such people to spend their month of leave at their village homes. It was improper to prevent them from going. The Nawabzada thereupon said to me that in former years they used to return after the period of their leave but this time they would not come back. That is why it was necessary to prevent their departure. I told him that I could not understand his argument, for if persons desired to go back home, they should not be prevented from doing so. They should not be forced to labour there. I added that he himself belonged to Uttar Pradesh, and that he at least should have sympathy with such folks. The Prime Minister at this asked me as to who would clean the streets and latrines of Karachi in case they did not come back?Footnote 95

Sri Prakasa referred to the labourers from Uttar Pradesh as ‘Hindus’, but not all of them would have been a part of caste Hindu society. The underlying implication of Liaquat’s query, from one upper-caste, upper-class man to another about who would clean the streets and latrines should marginalized caste sanitation labourers leave, was one he expected Sri Prakasa to understand: nobody else would do this stigmatized work, and surely they could not be expected to? Upper castes see the work of sanitation as polluting and take a series of elaborate measures to distance themselves from it or to remove it from their consciousness. It involves cleaning dry latrines, the ‘gutter work’Footnote 96 of unclogging sewers filled with ordure, emptying pits, septic tanks, and manholes, and transporting excreta.Footnote 97 It was, and is, work that kills those who do it.Footnote 98

Pakistan feared that the departure of sanitation labourers would result in ‘epidemic and pestilence’.Footnote 99 Refugee camps in different parts of the subcontinent were rife with diseases like cholera, malaria, diarrhoea, and respiratory illnesses, and many died.Footnote 100 Epidemics (and the accompanying necessity of quarantine) come with a high financial cost and disruption to the life of cities.Footnote 101 Fears that sanitation workers might choose to leave in a context of disease and mass exodus were not new nor exclusive to Partition. In plague-ridden late nineteenth-century Bombay, the Plague Committee relied on teams of ‘sweepers’ to ‘disinfect’ affected areas. Coercive sanitary measures to control the spread of infection led to rioting and a mass exodus from the city, halving the number of people resident in the city and causing factories to shut down. ‘The city authorities realized too late that the specialized sanitary workers’ from the Halalkhor caste,Footnote 102 on whom street cleaning and general sanitation depended, might also flee, making the city ‘uninhabitable’.Footnote 103 These fears surged again during Partition when an outbreak of cholera in camps in Lahore and protests about the inefficacy of the West Punjab government’s handling of the situation (where police had fired upon protesting refugees)Footnote 104 led to the Pakistan government deciding to send more refugees to Sindh. It declared a state of emergency, giving itself the authority to resettle 200,000 more refugees in Sindh instead of the 100,000 planned initially. Each day 6,000 refugees arrived, coinciding with serious floods and an outbreak of cholera in Sindh.Footnote 105 With the threat of disease looming large and refugee anger at their treatment simmering, the Pakistan government continued to refuse to yield to the demand that it allow sanitation labourers to leave. It risked rebellion from both Sindhi leaders resentful at the presence of the new arrivals and the refugees reeling from sickness and squalid living conditions.

Apart from the migrant labourers from Uttar Pradesh whose release Sri Prakasa was keen to secure, other marginalized caste communities in Karachi were from Marwar in what is now Rajasthan and northern Gujarat, regions south and east of Sindh that fell within India after Partition. The Dalits had migrated to Karachi in the wake of the drought that had begun at the close of the nineteenth century. At that time, they left rural regions bordering Sindh and relocated to the Bombay Presidency’s major cities, Karachi and Bombay, which offered better prospects for employment, to avoid degrading social discrimination, and because their landlords persecuted them. Many of these migrants belonged to the Meghwal and Valmiki castes. They obtained jobs in the sanitation departments of Karachi and Bombay municipalities.Footnote 106 The deputy high commissioner for India in Karachi, the Sindhi M. K. Kirpalani, insisted that these sweepers, thus, ‘belong to India—they have their homes in India and in many cases their families are also in India’ and that ‘they had never lost their contact with India and invariably went there once a year’.Footnote 107 However, these Dalits found it difficult—to the point of it being impossible—to obtain permits to leave Pakistan after Partition. The Pakistan government went so far as to shut them into the sweeper colonies, posting police around to ensure they had no way out.Footnote 108 The Sindh branch of the Gandhian Harijan Sewak Sangh (Servants of Harijan Society) attempted to disguise sweepers in ‘Marwari turbans’ to send them to India via Mirpur Khas but had limited success with this ploy.Footnote 109

Gandhi, who wanted to keep Dalits ‘Hindu’, said that he had received many reports from ‘Harijans’ that they would have to convert to Islam if they stayed behind in Pakistan.Footnote 110 Unlike Nehru, Gandhi believed the princely states had a pivotal role in post-colonial India and leaned on them to accommodate refugees.Footnote 111 In September 1947, he urged shipping magnates with links to Kathiawar to send ships to Karachi to bring Dalits to Kathiawar free of charge.Footnote 112 Gandhi was from Kathiawar and was born in the princely state of Porbandar. He used his linguistic and community ties to facilitate the resettlement of refugees there. Gandhi’s intervention did result in some Dalits evacuating by ship,Footnote 113 but at the end of January 1948 Gandhi was dead, shot by Godse, so his efforts to secure their departure came to an end. Leaving became ever more difficult for the marginalized castes as the Pakistan government started to intercept those who tried to leave. The High Commissioner’s Office in Karachi wrote to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, telling them to stop publicizing efforts in the Indian newspapers to evacuate and settle ‘Sind Harijans’ as it would result in Pakistan acting to hamper their evacuation.Footnote 114

Ambedkar and Sri Prakasa raised the issue of labourers stuck in Karachi with Nehru.Footnote 115 In December 1947, Ambedkar, who had received several letters from marginalized castes who could not leave, wrote to Nehru:

The Pakistan Government are preventing in every possible way the evacuation of the Scheduled Castes from their territory. The reason behind this seems to me that they want the Scheduled Castes to remain in Pakistan to do the menial jobs and to serve as landless labourers for the land-holding population of Pakistan. The Pakistan Government is particularly anxious to impound the sweepers whom they have declared as persons belonging to Essential Services and whom they are not prepared to release except on one month’s notice.Footnote 116

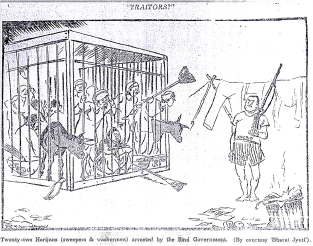

Ambedkar told Nehru that he had heard from marginalized caste refugees that the Pakistan government was stopping them from contacting the Military Evacuation Organisation (MEO), which India and Pakistan had set up for the organized exchange of refugees in Punjab and North India.Footnote 117 But the issue dragged on. Nehru telegraphed Liaquat in October 1948 requesting that Pakistan release the 20,000 ‘sweepers, washermen etc. who coming as they are from Gujarat, U.P. and other Indian provinces are Indian nationals’ on humanitarian grounds but did not receive an immediate response.Footnote 118 In the interim, Ministry of External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations officials were divided on what to do next—whether to approach the governor general of Pakistan to suggest that Pakistan ‘bring about such conditions as would induce the Harijans to continue to remain in Sind’ and whether Sri Prakasa’s assessment of the situation of the marginalized castes wanting to leave was accurate.Footnote 119 Both these ‘solutions’ involved kicking the can down the road. Finally, Karachi replied in November 1948 that the living conditions of the sanitation labourers were good in Sindh, where they received ‘very high wages’ and had no desire to go away to India. Pakistan would not overturn the laws prohibiting them from leaving but would consider allowing the district magistrate to issue permits in ‘individual cases’.Footnote 120 In practice, permits to leave were tough to obtain. The Indian government itself began to demand details of ‘individual incidents’ of discrimination that it could raise with Pakistan, thus putting sanitation labourers in the invidious position of facing prosecution while absolving itself of the responsibility to evacuate them (Figure 1).Footnote 121

Figure 1. R. K. Laxman’s casteist cartoon in the Bharat Jyoti newspaper showing Sindh’s chief minister, Khuhro, as a gaoler restraining sweepers, washermen and women, and agriculturalists from leaving, circa 1947. The title at top of the cartoon implies that the Pakistan government viewed the marginalized castes who were trying to emigrate as traitors to the nation.Footnote 122

Sweepers would have been, for the most part, unlettered. However, a series of distressed letters that Mohan Bhika Bhangi either wrote, or asked a scribe to write, to his kin in Radhanpur and Mubarakpur (now in Gujarat, India) to appeal to the Indian government survive in a government file. He wrote these letters on behalf of himself

and others in his situation. We do not know if Mohan Bhika knew how to read, write, or speak the languages required to apply for a permit to leave or if he and others like him could communicate in Urdu, the new language of governance. The letters are in a Kathaiawari dialect and provide an insight into how challenging the circumstances were for Dalits trying to migrate. I reproduce translations of three of his letters below:Footnote 123

n.d.

We, Mohan Bhikha, Bhana Sacha, and Vahla Kaala, all from Karachi, request that Bhangi Moti and sister Jivi, residing at Radhanpur, accept our kind regards. Jai Hind [Victory to India/Hindustan].

We write with a request that you take this application to Congressmen Narbheram and Kanjibhai and inform the Collector on our behalf that the Pakistan government is harassing the Harijans of Karachi. Although we have applied for a permanent job, we are constantly disturbed and harassed. They have confiscated our house and our jobs, recruited other people, and even dragged us to the courts. They have thrown our luggage on the road, and we are barred from doing our job. We request that dear Moti convey to the Collector that the Government of Pakistan should provide us with a house and a job or permit us to move to Hindustan. Please do this favour for us. There are eighteen people against whom cases have been filed, and eight are in prison. Please send us an official telegram.

30/8/1948

Jai hind

May the reader of my letter always be blissful. Let this letter reach Bhangi Dhanji Bhikha of village Mubarakpur. The senders are Mohan Bhikha and Mani Moti from the town of Karachi.

Dear Bhikha Vahla, Dhanji Bhikha, Kanji Bhikha, Karsan Bhikha, and other Bhangis of village Mubarakpur,

We pray that the lord always blesses you and keeps you happy. You must be doing well. We appeal to you. Mr. Dhanji Bhikha, we (Mohan Bhikha, Mani Moti, and others) have been facing great trouble since you left Karachi.

We were leaving Pakistan until we reached Nawabshah railway station, where we were caught and returned to Karachi. The government of Pakistan has stripped us of our jobs and homes and allotted those to other Bhangis. They have forcefully thrown our belongings on the road. Given this situation, we request Mr Dhanji Bhikha to take our letter to the Congress party of Radhanpur and insist that the Congress party either recommend to the Pakistan government to allow us to shift to Hindustan or return our jobs and houses with honour. We are facing adverse conditions with our children. Please insist that the Congress leader takes suitable steps, and if he fails, please immediately go to the Delhi government.

Dear Brother Dhanji Bhikha, we are very sad and dejected; please arrange for our return to India or help us get our job and shelter back in Karachi. Every week, we are forced to appear in court, and they harass us for no reason. We once again request Bhangi Dhanji Bhikha of village Mubarakpur to immediately approach either Congress leaders or the Collector to write a strong letter to Mr Sargul Hussain and others of Karachi to allow us to move back to Hindustan or return our jobs and houses as we have no place to live. We are living on public roads.

Dear Dhanji Bhikha, if you don’t get any local cooperation, please be kind enough to visit the Delhi government to explain our difficulties. We feel sorry that Hindustanis are not taking any initiative to help us with our horrible conditions.

28/09/1948.

Jai Hind.

May the reader always be blessed.

To the ones residing in Mubarakpur—Bhikha Vahla, Dhanji Bhikha, Kanji Bhikha, Karsan Bhikha, and other Bhangis of village Mubarakpur, I, Mohan Bhikha, pray that the lord always blesses you and keeps you happy. You must be doing well. We have been facing a very tough time for ten months since you left Karachi. The Pakistanis are harassing us. They have taken away our homes and jobs. We are made to appear at the court every day of the week. Pain and misery inflict us. Bhangi Dhanji Bhikha from Mubarakpur, please know that you must go to Radhanpur to meet the Congress Collector or Sargul Hussain of Karachi and tell them about our plight. We need permission to come from Karachi to Hindustan, or we will be destitute. The Pakistan government is not giving us our jobs and homes. Instead, they give them to other people. Dhanji Bhikha, if you do not get a response at Radhanpur, you must go to Delhi and plead our case. We are miserable here, and the Hindustanis are not bothered.Footnote 124

Mohan Bhika’s letters recall Ambedkar’s autobiographical Waiting for a Visa, which describes the vicious circles, dead ends, and closed doors he encounters on his journeys. Ankit Kawade has observed that these journeys and stays are experiences of being ‘homeless’ and ‘waiting’ in Ambedkar’s own homeland, where caste structures determine the temporal experience of Dalits.Footnote 125 Mohan Bhika’s letters demonstrate how Pakistan kept Dalits in a state of limbo. Even if the Pakistan government was determined not to let Dalits leave and force them to stay because it classified their labour as ‘essential’, this did not mean it would guarantee them employment or accommodation, making an already precarious life even more insecure and unsustainable.

As ethnographies of the bureaucratic regimes of the post-colonial ‘paper states’ of India and Pakistan show, new forms of documentation proliferated to shape social lifeFootnote 126 and ‘developmentalist’ projects.Footnote 127 These regimes include the poor in ‘welfare’ schemes that repeatedly produce arbitrary outcomes. In contrast, the purpose of this early post-colonial permit system for caste-oppressed sanitation workers did not have their welfare as its object but that of everyone else, including refugees, who lived in Karachi, requiring their forceful inclusion into the nation while they continued to be subject to the exclusions of caste and a state of exception under the law for the sake of the public good. They were ‘partial’ citizens but bonded to the Pakistani state. In contrast, other minorities had the mobility capital to get onto trains and ships to leave. The illogical next steps mentioned in Mohan Bhika’s letters of denying sanitation labourers their jobs and accommodation, imprisoning them, and forcing them to appear in court every week after officials had intercepted their movement did not seem to matter as long as officials had followed the rules to retain them.Footnote 128

It is worth noting here that Jogendranath Mandal, from the Bengali Dalit community of Namasudras, was Pakistan’s first minister of law and labour and, at Jinnah’s invitation, was temporary chairman of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. At first, Mandal believed that Dalits would find political emancipation in Pakistan rather than in a caste-based Hindu-majority India. In this, he had the support of Holaram Punjabi of the Sind Scheduled Castes Federation.Footnote 129 Recent scholarship on minorities in Pakistan, such as that by Ghazal Asif Farrukhi, shows that post-colonial Pakistan erased certain types of distinction, including caste, to create recognizable groups of religious minorities.Footnote 130 Mandal himself had the dual responsibility of representing both the nation’s Scheduled Castes and Hindus. Mandal was soon to be disappointed in Pakistan as the government failed to respond to Dalit concerns and demands on the representation of minorities and their security when communal violence occurred.Footnote 131

Marginalized caste labourers in Karachi, mostly ‘corporation employees, dock labourers, and servants’, approached Mandal to request badges that resembled Pakistani flags so that they were safe from both caste-Hindu Congress propaganda and anti-Hindu violence from Muslims.Footnote 132 But they found themselves recognized only as suspect minority Hindus, putting an end to any initial dreams of political emancipation for marginalized castes in Pakistan.Footnote 133 In 1949, at the same time as marginalized castes were trying to leave Karachi in the west, but Pakistan was forcing them to stay, communal violence broke out in East Pakistan, where many of the victims were Dalits.Footnote 134 Mandal resigned from Liaquat’s cabinet.Footnote 135 In his letter to Liaquat, he pointed to the perilous status of the Hindu minority in Karachi. He alleged that Muslims were converting Hindu women, the majority of whom were Scheduled Castes, to Islam.Footnote 136 The matter of religious conversion would also come up in connection with the Indian government’s failure to assist Scheduled Caste refugees, as I will show below.

The letters Mohan Bhika wrote took a circuitous route. One of those to whom he had appealed, Bhika Vahla Bhangi, passed the letters on to the Backward Class welfare officer of Banaskantha and Sabarkantha districts, who in turn handed them to the Backward Class officer of Bombay province, who forwarded them to the chief secretary of the government of Bombay, who sent them to the central government in Delhi. Mohan Bhika wrote his letters in August and September 1948, but the Indian government received them only in January 1949.Footnote 137 Mohan Bhika’s ability to write (or to have letters written) may have been of limited use. We do not know what happened to him and the others on whose behalf he communicated. There was no direct connection between literacy and justice in his case.Footnote 138 A lack of social, cultural, and political capital circumscribed the assets or mobility capital on which Mohan Bhika and others like him could draw.

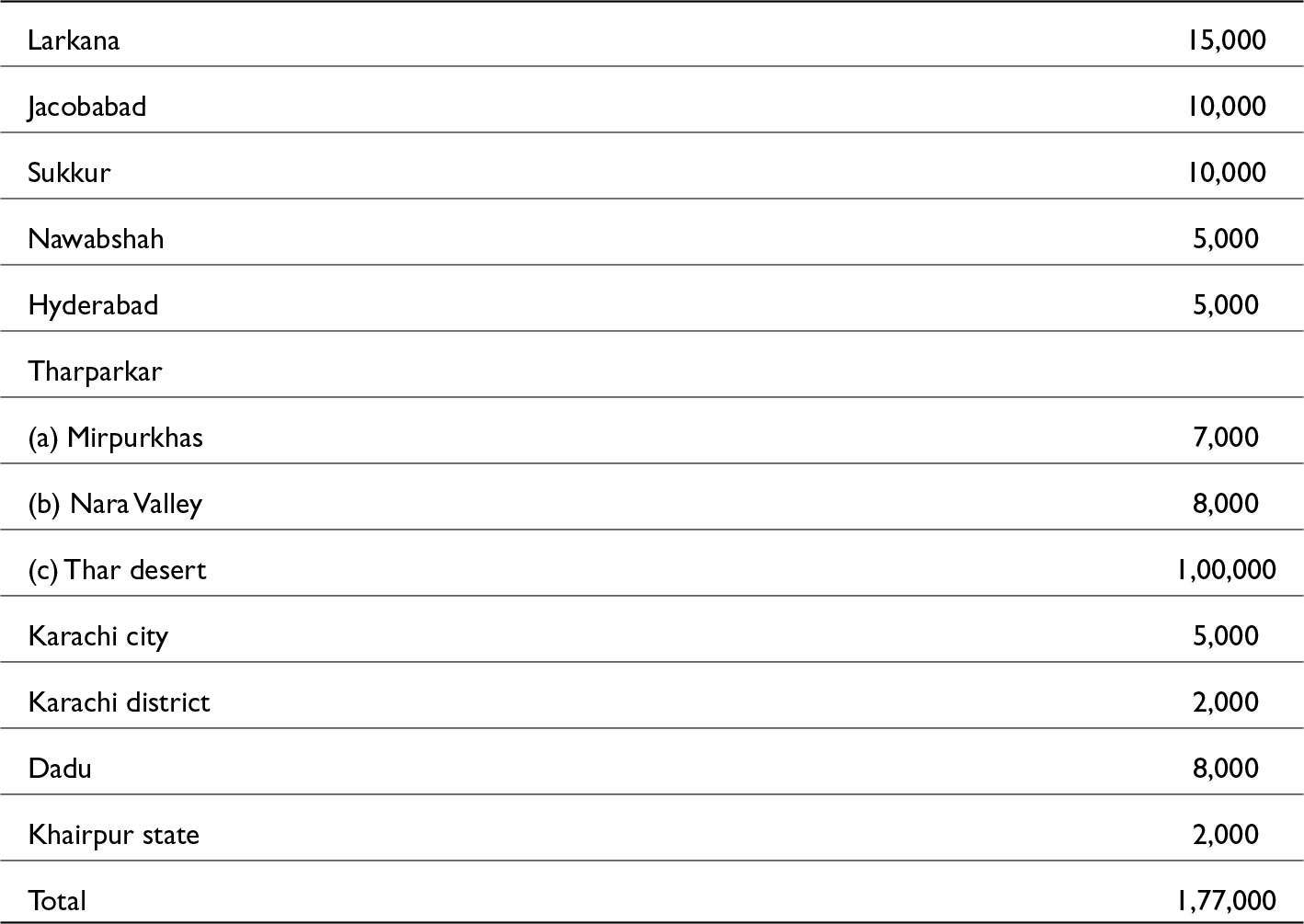

In December 1948, a year after Ambedkar had written to Nehru, Nanak Chand, a ‘Harijan activist’ and spokesman in Sindh, was still urging the Indian government to act with more haste, arguing that it was ‘Indian nationals’ whom Pakistan was forcing to stay behind against their will to do the work of scavengers. He produced a table of Scheduled Castes remaining in Sindh to show their location (Table 1). Delhi’s response remained dilatory, and it proposed instead a system of emigration by stealth.

Table 1. Nanak Chand’s table showing the number of ‘Harijans’ remaining in Sindh in December 1948.Footnote 139

‘Infiltration’ and crossing the border ‘quietly’

In addition to Dalit sanitation labourers, groups of marginalized caste agriculturalists from Tharparkar in the east of Sindh ventured to cross the border with their cattle. They had a history of seasonal circulation between Sindh and the western princely states of India. This changed after Partition as the Pakistan government suspected them of wanting to migrate permanently. The Sind Cattle and Fodder Control Act II of 1947 prohibited agriculturalists from ‘exporting’ cattle. Under existing agreements between India and Pakistan, evacuees could move cattle from one dominion to another and were exempt from export and import trade regulations and duties, provided the evacuees had a permit to take their cattle across the border. Nonetheless, the Pakistan government obstructed the departure of agriculturists with their cattle and, as was the case with the Dalit sanitation labourers, did not issue permits.Footnote 140 Nanak Chand argued that the Indian government should take up the matter with Pakistan at the highest levels because export was different from ‘taking one’s own cattle … on migration and not for sale or profit’.Footnote 141 However, officials in the Ministry of External Affairs in India considered that Pakistan was unlikely to allow the movement of cattle on a ‘mass scale’. They thought selling the cattle would be a more realistic alternative for the agriculturists who wanted to migrate.Footnote 142

Tharparkar cattle must interact with people daily to keep them from being ‘shy and wild’.Footnote 143 Also known as White Sindhi and Thari, they are excellent draft animals and produce large quantities of milk even in adverse conditions. Due to these qualities, the colonial government transported them to army camps in the Near East during the First World War.Footnote 144 For the Scheduled Caste agriculturalists of Tharparkar, their cattle constituted almost all their wealth (the cattle clearly also constituted capital for the Pakistani state) as they depended on their animals’ produce, so leaving them behind was out of the question.

Sri Prakasa wrote to Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy prime minister and home minister of India, that the Pakistan government had told the Indian High Commission to withdraw its liaison officers from Tharparkar and that he had told the peasants intending to emigrate to cross the border ‘quietly’ with their cattle. He wrote, ‘Their devotion to cattle is natural’, perhaps trying to emphasize their Hindu credentials to upper castes for whom the cow is sacred. Sri Prakasa asked that Patel arrange for the reception of these refugees and their cattle in the western princely states of Saurashtra, Jodhpur, and Kachchh in India.Footnote 145 Patel had only recently strongarmed these former princely states into becoming a part of the Indian Union. They were in the process of transitioning to Indian rule but were still in charge of refugee resettlement on their territories.

Although Jodhpur had shown signs of willingness to accept agriculturists rather than the numbers of Sindhi petty traders it had already received,Footnote 146 the ‘movement branch’ of India’s Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation insisted that the western princely states had made it ‘abundantly clear’ that they were not willing to take more refugees from Sindh and that unless the government ‘had tackled and resolved the problem of the resettlement’ of those who were already ‘in the Indian Dominion since the last 18 months’ it was ‘not advisable to invite trouble by undertaking major operation [sic] of evacuating non-Muslims including Harijans numbering 1,77,000 from Sind … It is therefore suggested that no action be taken in the matter at present unless [the] situation in Sind … deteriorates further to endanger the life and properties of those who are still in Sind.’Footnote 147 A letter Choithram Gidwani, the erstwhile leader of the Sindh Provincial Congress Committee, wrote to Mohanlal Saxena, who led the Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation, in December 1948 about the state of refugees in Saurashtra, a union of 217 princely states of Kathiawar, including the former Junagadh state, demonstrates the reluctance of Saurashtra to accommodate marginalized caste refugees:Footnote 148

Hundreds of Harijan refugees are arriving in Saurashtra. The Saurashtra Government are not prepared to take any more. The Government of India have sent no instructions. The local workers are surprised for the callous indifference shown by the authorities in making no arrangements for the refugees. They are lying in the open without any shelter.Footnote 149

When the Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation received Gidwani’s letter, it told the Ministry of States that it did not know what ‘Harijan refugees’ Gidwani was talking about, as ‘Our High Commissioner in Karachi is not supposed to send out any refugees without our prior authorisation.’Footnote 150

One of the tactics Sri Prakasa used to provoke the Indian government to take official action on evacuating Scheduled Caste refugees was to mention that if they did not migrate, they faced the possibility of forced conversion to Islam in Pakistan. His assumption here was that they were converting from ‘Hinduism’ rather than their own religious traditions.Footnote 151 He framed the problem as one in which the marginalized castes would lose their Hindu identity if the Indian government did not intervene on their behalf.Footnote 152 Upper-caste Hindu Indian government ministers sometimes reacted to this element of Sri Prakasa’s missives as if briefly jolted, galvanized into bursts of transient action when the possibility of conversion entered the conversation.Footnote 153 Conversion, among other things, threatened to reignite old upper-caste Hindu fears about maintaining a so-called majority, a competitive logic of numbers that the introduction of the colonial census made possible.Footnote 154 Still, even these jolts were not enough.

Considering that the situation had further ‘deteriorated’ in 1949 because of reports of forcible conversion, some government officials again proposed that rather than pursue organized evacuation, they adopt an unofficial policy of allowing ‘infiltration’ across the western border.Footnote 155 In October 1949, Minister of Transport Gopalaswami Ayyangar urged the government of India to deploy ‘non-official’ agencies at the border to help those intending to migrate so that Pakistan would not accuse India of official involvement in moving agriculturalists out of Sindh.Footnote 156 However, in November 1949, the issue was still ‘under consideration’.Footnote 157 The approach of the Indian government, then, was to make the occasional suggestion of undercover operations to assist Scheduled Caste refugees but not undertake any significant evacuation or resettlement programme for them.

Sri Prakasa said that he had managed to get some Scheduled Caste refugees across the border in a clandestine fashion. He had had more success with dhobhis who washed and ironed clothes because he had advised them to leave their irons behind. Sweepers faced a greater likelihood of arrest ‘as they are very strictly watched; and as they are all known to municipal headmen, they are invariably caught as they try to board steamers. I gave up the effort to send them.’Footnote 158 According to Jeevanlal Jairamdas, a member of the Congress Party and a leader of the Harijan Sewak Sangh in Sindh, approximately 200,000 Dalits were in Sindh at the time of Partition, with about 5 per cent of them emigrating to India.Footnote 159 But some marginalized caste refugees who had managed to reach India found conditions in India so bad and the lack of assistance so appalling that they started to make their way back to Pakistan, a chapter in this story that requires separate treatment.Footnote 160

While Partition divided Punjab, Assam, and Bengal between India and Pakistan, Sindh remained whole on one side of the new border. Sindhi Hindu refugees lost most connections to Sindh, including cultural and linguistic ties.Footnote 161 Still, those Sindhi Partition refugees who managed to cross the border could deploy their mobility capital to exercise an element of personal liberty in ‘voting with their feet’ to choose their country of residence and where they felt safest.Footnote 162 They exercised a level of choice in their political allegiances and citizenship, albeit in different ways and to different extents in the tumultuous circumstances of Partition.Footnote 163 These choices were not available to marginalized castes stuck on one side of the border.

Marginalized castes’ attempts to escape the constraints on their movement through formal means, such as written petitions, were unsuccessful. The Indian government’s suggestion that they use informal means to cross the border perhaps allowed for intermittent departures, but this process depended on chance. Caste constrained the mobility capital of these emigrants and, consequently, their eligibility to move as freely as those above them in the caste hierarchy who chose to leave.

Conclusion

Echoes of the past continue to reverberate in the present. In Pakistan today, bureaucratic practice and case law often conflate the terms ‘Hindu’, ‘Dalit’, and ‘hari’ (landless labourer or agriculturist). Historical caste stigma and ritual impurity are linked to the religious marginalization of minority groups like Christians and Hindus.Footnote 164 Advertisements for ‘non-Muslim’ sanitation workers have recently appeared in Punjab and Sindh, reserving these jobs for low-caste Christians and Hindus.Footnote 165 ‘Pakistani Hindus’ continue to migrate to India clandestinely or on short-term pilgrimage visas after which they apply for long-term visas.Footnote 166 They cross the India–Pakistan border each year for a range of reasons, believing that they will be subject to less religious discrimination in India and able to procure better work and living conditions. Low-caste identity impedes resettlement, and the path to citizenship is long and challenging, sometimes ending with fatal results. In 2020, a group of Bhils who had migrated across the border from Pakistan and worked on a farm in Jodhpur district in India died by mass suicide. Reports suggest that they were under duress because of the expiry of their visas.Footnote 167

Immigration and emigration are intimately connected, but the two processes are rarely studied in conjunction. Widening one’s lens to accommodate the constraints on emigration as well as immigration uncovers essential elements of the history of how the post-Partition states of India and Pakistan determined citizenship and the contours of nationhood itself. As the rich scholarship on the legal and material ‘differentiated’ rights and realities for minorities has shown, once India and Pakistan introduced their citizenship laws,Footnote 168 they took time to settle on who their citizens would be.Footnote 169 Restrictions on immigration—limiting entry and eliminating the right to return—shaped minority citizenship. However, as this article has demonstrated, restrictions on emigration also defined citizenship.

Though it took a while for India and Pakistan to arrive at the final citizenship rules that resulted in a liminal status for religious minorities, both countries decided the nationality of marginalized castes early—even if they did not announce their decisions as such. Pakistan deprived them of the freedom to emigrate, and India refused to facilitate their right to return or to immigrate when permits and ordinances framed putative and potential nationality and citizenship.Footnote 170 Section 3 of the Citizenship Act of 1951 of Pakistan provides that Pakistani citizens were those ‘who or any of whose parents or grandparents was born in the territory now included in Pakistan and who after the fourteenth day of August, 1947, has not been permanently resident in any country outside Pakistan’.Footnote 171 As Ali Usman Qasmi points out, ‘this reaffirmed the status of those who had ordinarily been resident in “Pakistan” and were also born there while successfully excluding those—almost all of whom were either Hindu or Sikh—who had migrated and were permanently resident in another country’.Footnote 172 In the case of the coercive inclusion of the marginalized caste refugees that this article discusses, they had not necessarily been born in Pakistan. Pakistan had forced their country of residence upon them even before it framed its citizenship laws excluding religious minorities who had emigrated.

India also adopted citizenship laws that made it difficult for anyone who had immigrated to or resided in Pakistan to claim citizenship in India after 1955, making ‘return’ and emigration to India all the more difficult for marginalized castes. Viewing the status of marginalized castes at Partition through the lens of the category of religious minority is, therefore, not sufficient. Like other religious minorities, they were ‘partial citizens’, but their particular lack of mobility capital was an additional hindrance, and in Ambedkar’s terms, they constituted ‘more than a minority’. The prohibitions on exit resulted in forced political assimilation and the same deprivations of denationalization: material statelessness and arbitrariness. It operated as a mechanism of social controlFootnote 173 and sovereign confinement.Footnote 174 It established not only a hierarchy of citizenship but kept people bound to it without their consent.

Migration ‘crises’ have dominated the headlines in the recent past, highlighting the numbers of people on the move. Exit control, containment, immobilization, and detention continue to correspond with regimes of non-entrée as part of modern nation-states’ management of mobility. Current policies of externalization that rich nations of the Global North implement are one of the starkest examples of this. At the same time that Europe works to limit entry by impeding exit through border externalization and the interception of migrants to prevent them from reaching their destinations, Israel is using all-too-familiar tactics of expulsion, refusing return, and containment to maintain violent control over Palestinians. Better accounting for histories of controlling who can and cannot emigrate is essential for understanding and responding to present violence. Immobilizing people can be just as powerful as forcing them into movement. Consequently, immobility and constraints on the ability to leave continue to remain significant in many contexts and demand greater attention alongside immigration control in studies of border control, refugee regimes, and modern citizenship.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and Sumit Guha of Modern Asian Studies for their thoughtful and encouraging engagement with the article. I have presented the research in this article in various forms at the South Asia Legal Studies Workshop, University of Wisconsin; the Migration History Seminar; the ‘In and Out of South Asia: Race, Capitalism, and Mobility’ conference at the University of Michigan; and the Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford. I am grateful for the feedback I received at these venues. Suggestions and questions on previous drafts from Catherine Briddick, Joya Chatterji, Matthew Gibney, Kali Handelman, Ankit Kawade, Sundeep Lidher, Natasha Raheja, Julia Schweers, Neelofer Qadir, and Nurfadzilah Yahaya pushed me to refine my arguments. Shrimoyee Nandini Ghosh and Farhan Zia helped me understand Indian egress control laws. Aparna Kapadia and Tejaswini Niranjana found a way to translate the letters, Manisha Shah transcribed them, and Tana Trivedi translated them. Sarfaraz Hamid and Mohsin Afzal Dawar procured some essential sources. I thank them all.

Funding statement

A British Academy fellowship helped to support some of the research in this article.

Competing interests

The author declares none.