In March 2008, ABC News set off a media firestorm by publishing controversial excerpts of sermons by Rev. Dr. Jeremiah Wright, the pastor of then-Senator and presidential candidate Barack Obama. In an attempt to distinguish his views on race from Wright's, Obama delivered one of his most well-known speeches, “A More Perfect Union,” on March 18, 2008. To close the speech, Obama described a young white woman named Ashley who had organized a roundtable discussion in a mostly Black community in South Carolina. Obama described how an unnamed elderly Black man said, “I am here because of Ashley.” Obama continued:

By itself, that single moment of recognition between that young white girl and that old black man is not enough. It is not enough to give health care to the sick, or jobs to the jobless, or education to our children. But it is where we start. It is where our union grows stronger … that is where the perfection begins.

Obama's message resonated with white liberal voters, and several political commentators attributed his “A More Perfect Union” speech as key to his electoral victory that November. But few have realized that the idea Obama so eloquently expressed has a history.Footnote 1

The idea that friendship and dialogue across lines of difference are the first steps to making a better world—an idea I call “talk-first activism”—flowered during the 1940s and 1950s as part of Protestant elites’ pursuit of consensus-driven liberal reforms. In the aftermath of wartime racial conflict, predominantly white ecumenical Protestant institutions such as the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA), the Federal Council of Churches (FCC), and the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), looked to Black people on their national staff to improve race relations. These Black staffers, middle-class leaders such as Dorothy Height, George Haynes, and Maynard Catchings, built on the social gospel-inspired movement for American interracialism and its traditional emphasis on talk and study. But they made several important changes. Backed by the financial and organizational power of their institutions, these Black ecumenical leaders created a series of interracial workshops and discussion guides designed to encourage white Americans to face their contradictions, rethink their assumptions, and live their religion and patriotism. Most importantly, Black leaders always insisted that interracial exchange was the beginning—not the end—of a process to eliminate racial prejudice and its effects. In doing so, they transformed the American interracial movement. Yet their work had more problematic and enduring consequences regarding how Americans conceived of the steps to transform society.Footnote 2

People inside and outside the academy continue to debate the uses and abuses of talk-first activism. Echoing a common narrative in Hollywood films since Sidney Poitier's rise to stardom during the civil rights era, some scholars have argued that friendship and talk across difference can eliminate prejudice and serve as an entry point for justice work.Footnote 3 Leaders of various institutions have embraced this idea. Diversity trainings, intergroup dialogues, and social justice book clubs are frequently suggested as first steps in a long-term effort to create a more equitable society.Footnote 4 Yet, just as criticism of racial reconciliation films has grown louder in recent years, so too has criticism of talk-first activism. Some scholars and activists have critiqued talk-first solutions as too focused on civility, individual prejudice, and consciousness raising. According to sociologist Saida Grundy, these initiatives often devolve into “mere filibustering.”Footnote 5 Here I explain the historical emergence of talk-first activism and why some of its original proponents came to see it as insufficient.Footnote 6 This article adds to a growing literature about how powerful religious institutions and networks facilitated an exchange of ideas that left an enduring imprint on American life.Footnote 7

After World War I, ecumenical Protestants embraced interracial talk and study as means to eliminate racial prejudice and violence. These practices came under increased scrutiny in the mid-1930s, leading to a major shift in the interracial movement during World War II. In the aftermath of wartime race riots, Black ecumenical leaders created dozens of “interracial clinics” to bring community leaders together to discuss and diagnose the causes of racial tensions in their communities. Insisting that each clinic create an action plan to follow the workshop, Black ecumenical leaders seeded the idea that interracial exchange was only the first of many steps toward ending racial discrimination. In the postwar period, printed interracial discussion guides helped spread this idea to the masses. These guides encouraged interracial groups to follow a series of successive steps to move from friendship to talk to action. Black ecumenical leaders’ emphasis on “action” suggested that friendship and discussion were not enough to end discrimination, even as the term's ambiguity allowed its meaning to change. Positioned as quintessentially American amidst an escalating Cold War, talk-first activism blossomed in the early 1950s alongside the rise of social psychology. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the growing urgency of the civil rights movement necessitated that Black ecumenical leaders and their institutions rethink their talk-first approach to ending racial injustice. However, by this point, these leaders no longer had control over the fate of the now-popular notion that dialogue across difference “is where the perfection begins.”

“Nothing But Talk”: Promoting Cooperation and Harmony in Interwar America

Ecumenical Protestant institutions’ tradition of talking about race had deep roots. Born of a desire to promote Protestant unity among different denominations, ecumenical Protestantism had long sought to bring Protestants together across lines of difference. Conversations about race became increasingly common in predominantly white ecumenical institutions with the rise of the Social Gospel in the early 1900s. For instance, from 1910 to 1916, nearly 50,000 white college students met in study groups to discuss white Student YMCA Secretary Willis Duke Weatherford's 1910 book, Negro Life in the South: Present Conditions and Needs.Footnote 8

In the aftermath of the race riots that ripped through the United States during and after World War I, ecumenical Protestants—especially women—increasingly cooperated across racial lines. Black and white women regularly interacted to promote wartime mobilization and fundraising efforts. Many of their efforts were facilitated by the YWCA.Footnote 9 Another major force for postwar interracialism was the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC), formed in early 1919. Led primarily by white Southern ministers and YMCA staffers such as Weatherford and Will Alexander, and backed by the YMCA to the tune of $500,000 in its first two years alone, the CIC prioritized easing tensions and ending mob violence.Footnote 10 Two years later, after the Tulsa race massacre, the Federal Council of Churches established a Commission on Church and Race Relations and asked Alexander and George Haynes, a prominent Black sociologist who had co-founded the National Urban League, to serve as co-secretaries for the new commission.Footnote 11 Unsurprisingly, considering the leadership role of Alexander and other CIC leaders, the commission focused on creating “pleasant experiences” across the color line, such as “Race Relations Sunday,” instituted in 1923.Footnote 12 Though ridiculed for its timidity in later years, even this modest initiative was viewed as suspect by many segregationists.Footnote 13 By actively promoting interracial cooperation, predominantly white ecumenical institutions provided reform-minded Americans with a gradualist alternative to more radical organizations such as Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, the Communist Party, and even the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).Footnote 14

Interwar interracialism achieved some limited successes. Some Black participants, such as Charlotte Hawkins Brown, successfully leveraged their interracial contacts to fundraise for Black organizations.Footnote 15 White people also benefited from interracial exchanges. A white participant in the 1926 interracial conference hosted by George Haynes and the FCC's Church Women's Committee (CWC) described the event as “the deepest spiritual experience” she had ever had (Figure 1).Footnote 16 Similarly, several white Southerners such as Katharine Lumpkin and Jessie Daniel Ames later cited their experiences with the interracial movement as turning points in their work for civil rights. More progressive than their male-led ecumenical counterparts, the YWCA and CWC likely sparked more of these racial epiphanies. And, occasionally, these epiphanies led to reforms regarding healthcare, journalism, or racial violence.Footnote 17

Figure 1: The 1926 CWC interracial conference. Participants of note include Charlotte Hawkins Brown (first row, fifth from left), Conference Chair Mary Westbrook (first row, sixth from left), and George Haynes (fourth row, center). “Interracial Conference of Church Women, Eagles Mere, Pa., September 21–22, 1926,” courtesy of Social Welfare History Image Portal, Virginia Commonwealth University, https://images.socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/items/show/492 (accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

Interwar interracialism had clear limitations. In practice, “interracial” meetings often had a disproportionate number of white participants.Footnote 18 Many of these white participants struggled to envision a world that did not include Jim Crow. Interracialism was, for them, a temporary coming together of Black and white Christians to break down prejudice and eliminate racial violence—not a bridge to an integrated society.Footnote 19 White participants’ limited goals for the movement meant, “It is easy for inter-racial gatherings to deliquesce into sentimental experience meetings or love feasts,” as Black poet Alice Dunbar-Nelson noted following a 1928 CWC conference. According to Dunbar-Nelson, Black women were the ones “who struggled hardest to prevent the conference from descending into a sentimental mutual admiration society, and who insisted that all is not right and perfect in this country of ours.”Footnote 20 In other words, few in number, Black participants had to convince white participants that racism and discrimination even existed. Moreover, emblematic of what historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham has termed the “politics of respectability,” interwar interracialism demanded that participants subscribe to white middle-class values, burdening its few Black participants with speaking these truths in a polite, calm manner.Footnote 21 Pointing out racism and discrimination risked alienating white allies and benefactors, but many Black participants considered it essential if the interracial movement was to create a more just society.

Interwar interracialism was also hampered by its gradualist methods. During a 1925 National Interracial Conference co-sponsored by the FCC and CIC, for instance, Will Alexander claimed that “patient study” was far more effective than the “moral heroics” of denouncing racial intolerance and injustice, much to the chagrin of Black delegates such as sociologist E. Franklin Frazier.Footnote 22 Frazier and other Black delegates recognized that the interracial movement's preference for study effectively functioned as a stalling tactic. Like gathering facts, talking about race could also become a circular endeavor. Some participants, especially Black participants, harbored dreams that open and honest discussion would lead to action. Alice Dunbar-Nelson admitted as much after the 1928 CWC Conference. Still, she knew that with “all smug and satisfied” white leaders, that was too much to ask.Footnote 23 Ultimately, Dunbar-Nelson concluded that if an interracial conference “does no more than clarify the wisdom of those present, it has justified itself.”Footnote 24 Yet, time proved that such assessments were overly optimistic. After several more years of discussions, observers increasingly called out the lack of action stemming from the interracial movement. In a 1934 issue of Opportunity, a journal co-founded and financially supported by George Haynes, white minister Cranston Clayton accused the Student YMCA and YWCA interracial programs of having “the atmosphere of a literary club” where students “do nothing but talk.… They literally talk themselves to death.”Footnote 25

By the mid-1930s, criticism from the left and fear of Americans’ growing interest in communism led American interracialism to more explicitly condemn segregation. Economic hardship and the Communist Party's defense of Black teenagers known as the Scottsboro boys led an increasing number of working-class Black Americans to become interested in the Communist Party.Footnote 26 In 1933, Haynes used communists’ appeal to Black Americans as leverage to garner white support for interracialism and its reforms, and the following year the FCC made Haynes the executive director of the recently rechristened Department of Race Relations.Footnote 27 Around the same time, young people also increasingly embraced desegregation (Figure 2). In 1934, a group of young left-leaning Protestant ministers—mostly white men but a handful of women and Black men as well—formed a group soon to be known as the Fellowship of Southern Churchmen to agitate against poor labor conditions, anti-Semitism, and segregation.Footnote 28 Increasingly collaborating after the creation of the National Intercollegiate Christian Council in 1935, YMCA and YWCA college students also pushed their parent institutions to embrace desegregation. At its 1936 convention, college student members of the YWCA voted to condemn segregation and recommended the national organization move toward the integration of local YWCAs. As Black, white, and Asian students increasingly pushed predominantly white ecumenical institutions to embrace desegregation, Black staff members moved to ensure that interracial exchange was just the first step of many toward ending racial discrimination.Footnote 29

Figure 2: In the 1930s, student YMCAs and YWCAs pushed their parent institutions to embrace desegregation. “[Group at YWCA Student Conference Waveland, MS],” 1931, Conferences: Southern, YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection MS 0324, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, MA, https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:497531 (accessed Dec. 20, 2021). Reproduced with permission.

“The Beginning of a Process”: Seeking Consensus and Seeding Action in Wartime America

The United States's entrance into World War II ushered in major shifts in the U.S. racial landscape. Thousands of Black men signed up for the armed forces while Black women volunteered for the Red Cross, United Service Organizations (USO), and other organizations that assisted in the war effort. At the same time, Black Americans, their newspapers, and their allies worked to define the meaning of the war by linking Hitlerism abroad to Jim Crowism at home. As part of this “Double V” campaign, A. Philip Randolph and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters successfully lobbied for an executive order that guaranteed war industry jobs would be open to Black Americans. Spurred in part by the dream of new vocational opportunities, Black migrants followed the footsteps of millions of others and moved to urban settings during the war. The movement of Black and white Southerners into urban areas resulted in a woeful shortage of housing and increased friction between Black migrants and their new urban neighbors. In the summer of 1943, racial tensions reached a boiling point, and race riots—frequently brought about by white Americans’ anxieties about Black soldiers—erupted across the country, most notably in Detroit, Harlem, Los Angeles, and Beaumont, Texas.Footnote 30

Several prominent Black social scientists attempted to respond to these riots by facilitating interracial exchanges that could “stem the tide” of rising racial tension. Historians have written about Fisk sociologist Charles S. Johnson and his community self-surveys and Race Relations Institute.Footnote 31 Less well known is the wartime work of George Haynes (Figure 3). Having reported on the wave of lynchings and race riots that followed World War I demobilization, Haynes knew all too well how war could inflame racial hatred, endangering both Black people and U.S. geopolitical aims.Footnote 32 After the 1943 riots, Haynes designed and implemented a series of “interracial clinics” across the nation. In these clinics, Haynes arranged for a multiracial group of community leaders to come together, discuss what they perceived as the underlying causes of racial tension in their community, and come up with solutions to address those underlying causes.Footnote 33 Haynes sought to use the spiritual, organizational, and financial strength of his organization to implement his vision. “Within the Church,” he later explained, “we have the machinery for getting our methods down to apply to the everyday life of the people.”Footnote 34 That machinery was spiritual, but it was also financial and organizational. Between 1944 and 1946, Haynes used the Church's machinery to conduct interracial clinics in over thirty cities and to distribute information about his materials and methods to over 140,000 pulpits.Footnote 35

Figure 3: As the Executive Director of the FCC's Department of Race Relations, George Haynes conducted over thirty interracial clinics from 1944 to 1946. “George Edmund Haynes, Ph.D., sociologist, author, educator, May 11, 1880–Jan.8, 1960,” 1945, courtesy of Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota, http://purl.umn.edu/77787 (accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

Haynes's interracial clinics had much in common with interwar interracialism. Like the initiatives in the late 1910s, Haynes organized his World War II–era conversations in the aftermath of race riots and uprisings as a way to quell violence. In some senses, interracial clinics—like their interwar predecessors—could be understood as conservative instruments to pacify Black complainants. Moreover, these wartime efforts echoed interwar interracialism's politics of respectability. Interracial clinics were not for the general public but for “key people.”Footnote 36 Wartime interracialism again attempted to channel Black rage, forcing middle-class Black people to engage in polite conversation about the racial terror and discrimination that affected their communities.Footnote 37

Still, Haynes's interracial clinics diverged from interwar interracialism in important ways. Haynes insisted that interracial clinics should not rely on one or two token people of color, as was frequently the case during the interwar years. Rather, he wrote, “Delegations should comprise equal numbers of White and Negro persons both men and women.”Footnote 38 Recruiting delegations was not always easy. Irving K. Merchant wrote Haynes about the clinic in Trenton, New Jersey: “We have gotten everybody interested in our Clinic except the YMCA. If you, or the Lord, can do anything with those birds, go to it, and do it before I go to Heaven.”Footnote 39 Despite difficulties, many clinics did successfully recruit relatively equal numbers of white and Black delegates, and a handful of clinics, especially those on the West coast, also included several Mexican American and Japanese American participants.Footnote 40 While a participant of color still had to endure the spiritual and emotional toll of educating white people about racism, relatively balanced racial demographics at least ensured that they were not expected to be the sole representative of their race to a largely white audience.

Haynes's clinics also diverged from interwar interracialism by framing discussions with social science facts, pointed questions, and resource leaders that steered conversations toward particular conclusions. An early member of the Du Bois-Atlanta school of sociology, Haynes believed that social science could convince white Americans that racism was a problem in their communities.Footnote 41 Local leaders needed to “face the facts … about local employment, housing, schools, religious barriers, leisure-time or other situations.”Footnote 42 Haynes carefully cultivated the facts participants should face. Prior to a clinic in Springfield, Illinois, Haynes ordered 100 copies of The Races of Mankind, a pamphlet by anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish that linked biological racism to Nazism.Footnote 43 Haynes also shepherded conversations to particular conclusions with his use of pointed discussion questions. He asked the attendees of the Trenton clinic questions like, “From what occupations have Negroes been excluded?” and “What are some of the difficulties Negroes or members of other minority groups have in obtaining mortgage money for the purchase of homes?” Haynes did not ask whether Negroes were excluded from occupations or faced difficulties obtaining mortgages; he asked how. Finally, Haynes shaped conversations by selecting “resource leaders” to “guide discussion” and interject as needed to provide “expert information.”Footnote 44 These tweaks to interwar interracialism helped ensure that clinics were, to quote Irving Merchant, “eye-openers to the White people.”Footnote 45

The most important difference from interwar interracialism, however, was Haynes's insistence that discussion and study had to lead to something else. In an article about the program, Haynes wrote, “The clinic is to be regarded as the beginning rather than the end of a program of race relations.” And to make sure the point sunk in, Haynes repeated the claim several sentences later, this time with added textual emphasis: “It is the beginning of a process aiming to end in social action.”Footnote 46 To ensure clinics were not “mere lip service to the ideal of justice and goodwill,” Haynes had each clinic create “an action program” and designate an agency to follow through on that program.Footnote 47 For clinics struggling for ideas, Haynes created a list of possible actions that included everything from promoting Race Relations Sunday to organizing boycotts and legislative efforts to end segregation.Footnote 48

The results of these clinics were mixed. Some interracial clinics in the East, Midwest, and West did achieve tangible successes. The Trenton interracial clinic led to the creation of the Trenton Committee for Unity, an organization that spearheaded the desegregation of Trenton's school system and public housing and helped draft and pass New Jersey's Fair Employment Practices Commission.Footnote 49 However, according to Benjamin Mays, the President of Morehouse College and the first Black Vice President of the FCC, the Department of Race Relations’ initiatives faced difficulty garnering “full cooperation from some of the Southern churches.”Footnote 50 The Southernmost city to hold an interracial clinic was Louisville, Kentucky.Footnote 51 Reliant upon white participants’ willingness to sit, eat, and converse with Black leaders and participants, Haynes's interracial clinics had few takers in the Jim Crow South.

Religious and patriotic demands for unity helped interracial clinics seed the idea that interracialism should lead to reform. Wartime race riots represented discord that threatened not only Christian unity but also the American war effort. Thus, addressing the underlying causes of the riots was both a patriotic act and a religious act. Like other Black leaders, Haynes used the wartime context as leverage. “How can we keep the confidence of hundreds of millions of colored peoples in South America, in India, China, Africa and the Pacific Islands,” he exclaimed in 1945, “if we continue to deny to our minority racial groups at home the freedom we are fighting for and talking about abroad?”Footnote 52

Interracial clinics’ emphasis on unity limited their action plans. Representative of an ideology of consensus that pervaded ecumenical Protestantism and elite circles more broadly throughout the 1940s and 1950s, interracial clinics brought community leaders together to discuss and “seek a consensus of judgement on what should be done.”Footnote 53 But what does it mean to seek “consensus” with a segregationist? While the Trenton Interracial Clinic achieved important results, the inclusion of segregationists like Trenton's Superintendent of Education Paul Loser dulled the clinic's recommendations.Footnote 54 The clinic failed to condemn segregation in education and instead had to create the Trenton Committee for Unity to do so. Haynes's emphasis on middle-class community leaders and his inclusion of segregationists like Loser shaped the clinics’ priorities and limited participants’ imaginations of what was possible. Thus, amplified by the wartime demand for unity, the ideology of consensus that undergirded interracial clinics simultaneously facilitated and limited racial reform.

“Step by Step with Interracial Groups”: Spreading the Gospel of a Multistep Process for Integrating Postwar America

Black Americans continued to push for economic and civil rights after the end of World War II. Returning Black veterans became symbols for an increasingly rights-conscious generation, while disgust at the horrors committed by the Nazi racial regime helped crack holes in the racial ideology of Jim Crow. Advocates for Black rights seized the opportunity and increasingly fought for change in the workplace and in local, national, and international politics.Footnote 55 Some Black religious leaders and practitioners, especially women, also increasingly advocated for Black rights and integration.Footnote 56 Many of these leaders drew on Ghandian pacifism to organize interracial protests such as the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation that prefigured the 1961 Freedom Rides.Footnote 57

Black ecumenical leaders achieved their first major institutional victories in March 1946. On March 6, the FCC overwhelmingly passed a resolution declaring racial segregation “a violation of the Gospel of love and human brotherhood,” and called upon its constituent denominations to pass similar resolutions.Footnote 58 A week later, the YWCA overwhelmingly passed an “Interracial Charter” that pledged that “wherever there is injustice on the basis of race, whether in the community, the nation or the world our protest must be clear and our labor for its removal, vigorous and steady.”Footnote 59 A few days after that, the YMCA followed suit. It resolved to eliminate segregation as part of its national policy and encouraged local YMCAs to “work steadfastly toward the goal of eliminating all racial discriminations.”Footnote 60 Though imperfect, the resolutions were tremendous feats.Footnote 61 After all, Black leaders and young people had convinced three of the most powerful ecumenical institutions—all of which had a significant presence in the U.S. South—to boldly denounce segregation in 1946, almost two decades before the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The Pittsburgh Courier credited Dorothy I. Height as the woman primarily responsible for the passage of the YWCA's Interracial Charter, by far the boldest and most specific of the three institutions’ resolutions.Footnote 62 Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1912, Height began working for local YWCAs in 1937, and in 1944 she became the YWCA national office's Secretary of Interracial Education (Figure 4). In this position, Height traveled around the country facilitating discussions with local YWCAs as a way to build support for the Interracial Charter.Footnote 63 She was particularly suited for this role; almost all of her professional references noted her exceptional ability to lead discussions and “break down prejudice.”Footnote 64 During these discussions, Height likely drew on the information and discussion questions included in The Core of America's Race Problem, a ten-cent pamphlet she edited in 1945. America's race problem, according to the pamphlet, was not racial separation per se but the resultant inequities and discrimination that sprang from an enforced system of racial separation.Footnote 65 In the words of one reviewer, the pamphlet “pulls no punches in attacking, on both religious and scientific grounds, the causes and the basic absurdities of racial discrimination and prejudice.”Footnote 66

Figure 4: In 1944, Dorothy Height began working as the national YWCA's Secretary of Interracial Education. Many considered her the woman primarily responsible for the passage of the YWCA's groundbreaking Interracial Charter in 1946. “Dorothy Height, 1946 January, head and shoulders, with pearls,” 1946, by Jan Pach, courtesy of YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

Unsurprisingly, Height faced numerous challenges during her visits to local YWCAs. According to one of her references, Height sometimes provoked an “unfavorable reaction” because “she is an attractive, well dressed Negro, and the subject matter we were dealing with.”Footnote 67 Height's middle-class presentation irked some white Americans as she traveled between local YWCAs too. While on the train from Dayton, Ohio, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a white woman became upset about Height's presence in the Pullman car. The Pullman conductor tried to persuade Height to move to the coach car, even though the YWCA had purchased a ticket for the Pullman car. For over four hours, Height resisted near-constant pestering and name-calling by the Pullman conductor and the supposedly aggrieved white passenger before she eventually headed to the dining car for something to eat.Footnote 68 As the episode demonstrates, Height was not one to be bullied or intimidated from standing—or sitting—for what she believed was right, and this perseverance proved crucial to passing the YWCA Interracial Charter.

After March 1946, the challenge for ecumenical Protestant institutions like the YWCA became how to translate their national pronouncements regarding segregation into actual changes in local churches and Christian associations. The national leadership of the YWCA asked Height to create a primer on integrating local associations. Height discussed the matter with her friend and colleague Polly Cochran. After weeks of questioning the need for such a primer, Height admitted to Cochran:

Well, there are different steps that you take. You have to understand different places where people are; to choose what kinds of activities help people who are of different races come together more easily than others; what kinds of activities are people fearful of doing with people that they might have some ideas about; how do such things as myths about health and disease and all that, how do these things affect the way people react in groups? And so forth.

Cochran astutely responded, “Well you really are talking about doing it step by step.”Footnote 69 Height liked the phrase so much it became the title of her influential next pamphlet.

In Step by Step with Interracial Groups, Height provided local YWCAs with a guide for integrating their organizations (Figure 5). In the twenty-five-cent pamphlet, Height wrote: “Pleasant interracial experience was often the first step in moving from a racial to an interracial group.” She suggested that activities of mutual interest such as crafts, sports, or dancing could provide opportunities for pleasant exchanges. Though she encouraged YWCAs not to rush into discussing race, Height made clear that this second step was essential. “Some day, every group needs to move from the ‘getting acquainted’ stage to a realization of the life struggles of fellow Americans,” and she listed ways, such as listening to popular Black protest songs, to stimulate the discussion. After that, interracial groups should work “for laws in keeping with democracy at its best.” This multistep process would not be easy, but Height and other Black ecumenical leaders believed that the journey would make for a better world.Footnote 70

Figure 5: In 1946, Dorothy Height wrote Step by Step with Interracial Groups as a guide to help local YWCAs integrate their organizations. The book epitomized the YWCA's philosophy on race for the next seventeen years. “Cover of the revised edition of a publication by Dorothy I. Height, YWCA Publications Services, 1955,” YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, MS 0324, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA. Reproduced with permission.

Step by Step and The Core of America's Race Problem had a lot in common with Haynes's interracial clinics. Like Haynes, Height employed social science facts and Christian rhetoric, pushed groups to be racially balanced, and used pointed questions to frame conversations.Footnote 71 She also insisted that “interracial” should not be limited to Black and white people. Though somewhat edgier than Haynes's interracial clinics, Height's initiatives also operated within a framework of consensus: interracial experiences “set in motion [a process] out of which the members develop a genuine consensus. The alert leader finds the way and the moment to get this consensus … and to help the group act upon it.”Footnote 72 In other words, both Haynes and Height wanted participants to take actions that could make real the promises of Christianity and democracy, but they insisted these actions should spring from a sense of unity and togetherness.

At the same time, Step by Step and The Core of America's Race Problem differed from Haynes's clinics in ways that contributed to the spread of talk-first activism. Most obviously, these were affordable printed guides rather than two-day conferences. This meant that Height did not have to be physically present for discussions as Haynes had been for his interracial clinics. And whereas Haynes recruited community leaders for his clinics, Height designed her initiatives to appeal to everyday members of local YWCAs. These differences increased the circulation of Height's ideas, but it also meant she had less control over the process and outcome.

“The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights”: Combatting the Constraints of the Early Cold War

Over the next two years, as the movement for civil rights and human rights continued to swell, Black ecumenical leaders ramped up their efforts to ensure that American Christians continued the step-by-step process. Unfortunately, the momentum did not last. By the late 1940s, civil and human rights leaders had to grapple with a growing anticommunist movement. Suspicious of any change to the status quo, anticommunism fractured rights-advocates’ big-tent coalition and effectively “chilled” their movement.Footnote 73

Ecumenical institutions also felt the sting of anticommunism. In 1948, just a few months after Whittaker Chambers accused Alger Hiss of running a spy ring within the U.S. State Department, Joseph Kamp claimed that communists had infiltrated the YWCA. Critics made similar claims about the Federal Council of Churches and Student YMCAs.Footnote 74 The ever-present possibility of being labeled a communist curtailed Black ecumenical leaders’ efforts. Height later lamented, “If you protested against the lack of jobs or against discrimination, immediately you were considered a Communist. You were considered unpatriotic.”Footnote 75 In this restricted environment, Black ecumenical leaders worked determinedly to position their work as quintessentially American and fundamental to one's civil and religious duties (Figure 6).Footnote 76

Figure 6: With its gradualism and Christian and democratic rhetoric, talk-first activism bloomed during the early Cold War. “Commission on Interracial Policies, National Board YMCA, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 10–11, 1949,” by Edward Brinker, courtesy of Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota, http://purl.umn.edu/77702 (accessed Dec. 20, 2021).

Co-written by Dorothy Height and J. Oscar Lee, George Haynes's successor at the Federal Council of Churches, the 1948 pamphlet The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights: A Guide to Study and Action exemplifies how Black leaders navigated the constraints of the early Cold War. Published days after the United Nations's adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Height and Lee wrote The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights to popularize the conclusions of President Truman's Committee on Civil Rights. They outlined various civil rights issues, such as poll taxes, housing discrimination, segregation of the army, and police violence, and they distributed tens of thousands of copies to churches and Christian associations across the country—a Methodist women's organization alone purchased 15,000 copies.Footnote 77 Though some Americans considered discussing these issues unpatriotic, Height and Lee countered these claims by emphasizing the individualistic, democratic, and Christian roots of their work.

Though elements of early Cold War ecumenical dialogue guides were radical, Black ecumenical leaders frequently deflected accusations by insisting upon the gradualist nature of their work. In The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights, Height and Lee wrote, “There can be no miraculous overnight conversion of the public. One by one, individuals are enlightened.”Footnote 78 The authors’ emphasis on converting individuals was steeped in Protestant tradition. But Cold War fears of collectivism, as well as Lee's anti-confrontational tendencies, also shaped their tactics.Footnote 79

Democratic and patriotic rhetoric also helped Black leaders acquire space to operate amidst the constraints of the early Cold War. Black ecumenical leaders suggested that reform-minded interracialists, unlike status-quo segregationists, were true patriots because they helped make what sociologist Gunnar Myrdal called the “American Creed” a reality.Footnote 80 In The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights, Height and Lee emphasized the geopolitical reasons for supporting civil rights.Footnote 81 Height became even more explicit in her 1951 guide Taking a Hand in Race Relations. Writing as Chinese and North Korean forces captured Seoul during the Korean War, she declared that other countries “hear our words about democracy at the same time that they feel the pull of communism.… How can our love of democracy be real, they ask, when we will not practice it at home? Show us democracy, don't tell us about it, they seem to be saying.”Footnote 82 By positioning their projects as a defense of democracy's moral integrity, Black ecumenical leaders provided an additional reason why white Americans should join them: even if they refused to hear Black Americans’ cries of injustice, white Americans might listen to patriotic appeals to American superiority and exceptionalism.

Black leaders’ insistence on the religious nature of talk-first activism also proved beneficial in this era. As tensions with “godless” communists grew into a full-fledged Cold War, religious expressions became a form of patriotism.Footnote 83 Though Black ecumenical leaders had never shied away from the religious nature of their work, they became more explicit about it in this period. Echoing social gospel ideas, Height and Lee wrote that talk-first activism sprang from the “Christian belief that man—each man, every man—is of supreme worth because he is a child of God.” In other words, humans, regardless of race, had the same relationship to God. Height and Lee wrote that in order to fulfill Jesus's command to “love thy neighbor as thyself,” Christians had a responsibility to “create the kind of society which safeguards the intrinsic worth of every person as a child of God.”Footnote 84

Black ecumenical leaders pressed their readers and discussants to commit to concrete actions to do just that. In her autobiography, Height recalled how many Christians were quick to agree with the theology but slow to act on it: “Too often, people in Christian groups babbled on about how ‘all men are created equal’ or ‘we're all children of God,’ but if you asked them what line they were going to pursue to make those ideas reality.… They'd always have some excuse for not taking direct action.”Footnote 85 In The Christian Citizen and Civil Rights, Height and Lee acknowledged that many American Christians feared becoming “involved in the ‘dirty matter of politics,’” but they insisted on the need to engage mechanisms that create change.Footnote 86 “While laws are not the whole answer, good ones help,” Height wrote in Taking a Hand in Race Relations.Footnote 87 Black ecumenical leaders encouraged their participants to act on their newfound consciousness as soon as possible. As Height and Lee concluded a section about segregation in the armed forces, “It is not enough to have fun discussing things; get everyone present to begin to act by sending letters … to the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of the Army … to the President … to the special committee.” The authors hoped that these discussions and subsequent actions—no matter how small—would be “a little leaven in the whole organization … to bring about the widest possible interest and the most effective action.”Footnote 88 In this era when any critique of the status quo could be construed as unpatriotic, Black ecumenical leaders hoped that integrating minor actions into interracial discussion groups would create ripples of activism in churches and Christian associations across the country.

“These Sessions Proved Therapeutic”: Psychology and the Flowering of Talk-First Activism

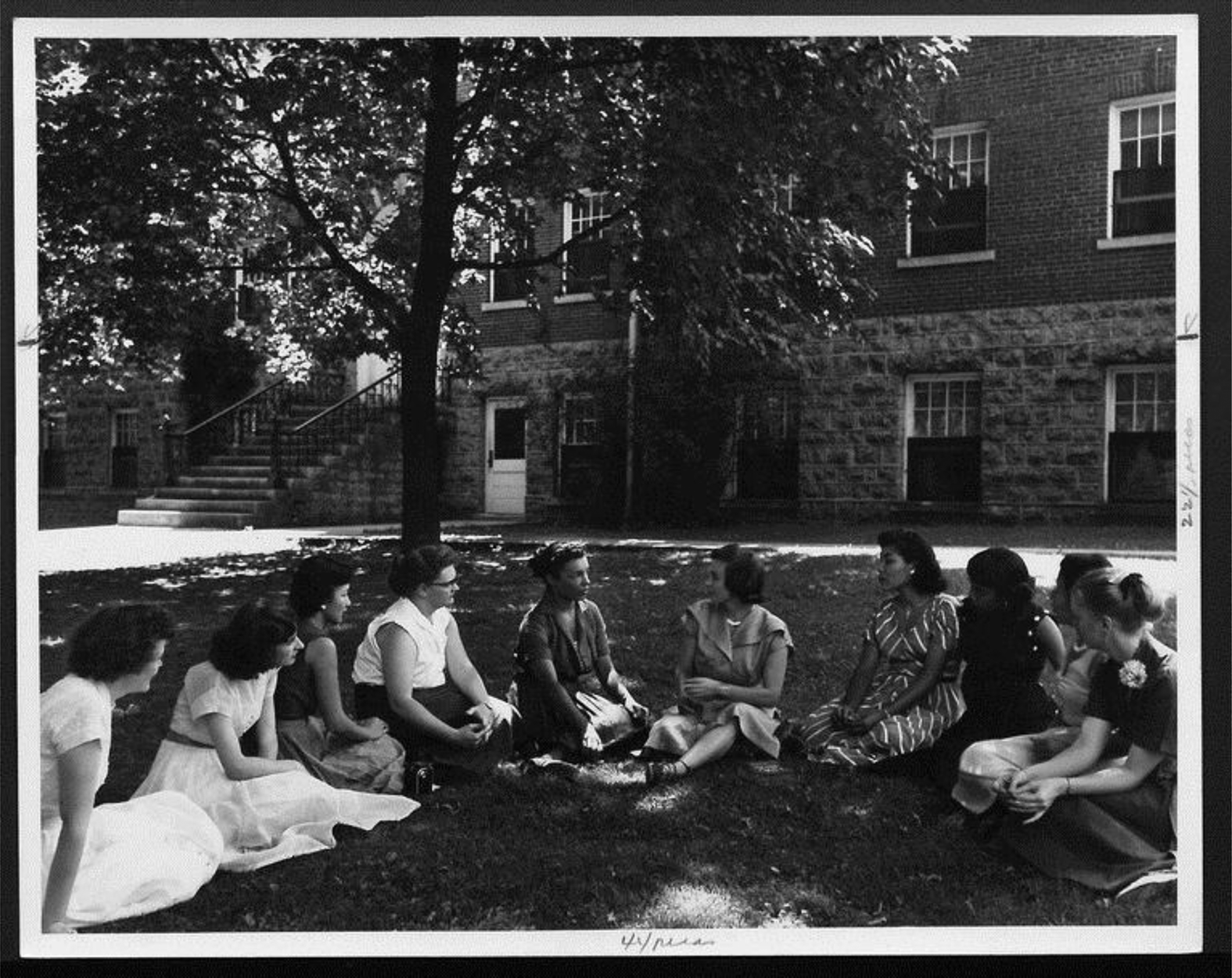

Though they rarely created tidal waves of activism, Protestant-led interracial conferences and discussions became even more popular during the 1950s (Figure 7).Footnote 89 Their popularity stemmed from how Black ecumenical leaders had successfully framed these discussions as quintessentially American, as well as the cultural shift from direct action back toward gradual reform. But these were not the only factors that contributed to talk-first activism's popularity in the 1950s. Growing societal interest in using psychology to combat prejudice also proved crucial to the flowering and pollination of talk-first activism.Footnote 90

Figure 7: This photograph of a YWCA discussion group in 1954 had “Return to D. Height” written on the back. “Discussion Group – 1954 YWCA School for Professional Workers,” 1954, Personnel and training: School for Professional Workers, YWCA of the U.S.A. Records, Sophia Smith Collection, MS 0324, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, MA, https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:487667 (accessed Dec. 21, 2021). Reproduced with permission.

Beginning during World War II and continuing throughout the 1950s, social scientists increasingly published research about how to eliminate racial and religious prejudice. Social psychologists were at the forefront of this work. Often underwritten by Jewish and ecumenical Protestant foundations and organizations, their research had a monumental impact on American culture and society. For example, research by psychologists Mamie Phipps Clark and her husband Kenneth Clark, a longtime friend of Dorothy Height, significantly influenced the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.Footnote 91

Arguably the most influential postwar social psychologist was Harvard professor Gordon Allport. Allport had long moved in ecumenical Protestant circles. The Episcopalian and former local YMCA committee chairman was a popular and frequent speaker at Charles S. Johnson's Institute of Race Relations.Footnote 92 In his 1954 book The Nature of Prejudice, Allport distilled the idea that had animated the interracial movement for decades: that under proper conditions, interracial contact could lead to a decrease in religious and racial prejudice. Written for both academic and popular audiences, The Nature of Prejudice helped spread this idea far beyond ecumenical Protestant circles.Footnote 93

Though social science had long influenced American interracialism, the postwar popularization of psychological ideas spurred interest in the interracialist movement and led ecumenical Protestants in the 1950s to describe their work using the language of psychology and therapy. “With the break-through in the segregated social structure [due to Brown v. Board of Education], the frontier in integration is fast coming to rest in psychology,” a subgroup of the National Council of the Student YMCA-YWCA declared in 1957.Footnote 94 In other words, many ecumenical Protestants believed that psychology was necessary because simply outlawing segregation would not achieve integration. With a presence on hundreds of campuses, the Student YMCA-YWCA led ecumenical Protestants’ attempts to dismantle Americans’ Jim Crow mindset.

L. Maynard Catchings, a young Black minister who had spent over a decade operating in religious and racial justice circles, directed the Student YMCA-YWCA during these years (Figure 8). As a student at Howard University, Catchings roomed with future civil rights icon James Farmer and worked as the student assistant to Howard Thurman, a future mentor of Martin Luther King Jr.Footnote 95 Catchings met his wife, Rose Mae Catchings, an activist in her own right, at a Student YMCA-YWCA conference in the early 1940s, and soon after both began working as Southern field secretaries, Maynard for the YMCA and Rose for the YWCA. In the mid-1940s, Maynard Catchings began teaching at Fisk University and working with Charles S. Johnson's Institute of Race Relations where he led worship services, conducted community self-surveys, and met social science experts like Allport.Footnote 96 These diverse experiences prepared him for his role as the Secretary of Student Services for the YMCA beginning in 1953. Backed by a $45,000 grant over three years, Catchings traveled to hundreds of universities across the country leading interracial discussions and workshops with Student YMCA-YWCAs.Footnote 97

Figure 8: L. Maynard Catchings worked as the Secretary of Student Services for the YMCA from 1953–1958. “Rev. Lincoln Maynard Catchings,” [1955–1966], courtesy of Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota, http://purl.umn.edu/77589 (accessed Dec. 23, 2021).

Catchings's YMCA-YWCA workshops reflected many of the characteristics of mid-century interracialism, but with a twist. Catchings's workshops wove social science, theological and scriptural justifications, and an insistence that interracialism was the first—not the last—step toward racial justice. But Catchings added an emphasis on feelings and emotions. For instance, Gladys Lawther began her report of a Catchings-led workshop in Portland, Oregon, in February 1956, by saying, “‘You've got to have the facts, ma'am.’ Yes, and you must also feel the impact of those facts.”Footnote 98 Catchings encouraged participants to “feel” facts through interracial exchange and worship.

Catchings believed that these felt interracial experiences could serve as a form of group therapy. In 1955, he concluded:

These sessions proved therapeutic in that they aided the student to discover his own attitudes and to evaluate them in the light of his faith, or to reexamine his faith in the light of his attitudes. Often students who attended interracial projects or student conferences testified that their personal growth in this area was directly related to their experiences in a community of acceptance.Footnote 99

Therapeutic experiences in a “community of acceptance” were not intended to make participants feel good, at least not initially. Rather, to quote the Student YMCA-YWCA National Council a few years later, these experiences were designed to expose “the contradiction between the Christian faith and race prejudice” and bring about a “real crisis of faith” for Christians who believed God ordained segregation. The community would then serve as a “supporting and forgiving community” for those who had experienced the crisis.Footnote 100 In other words, drawing on the ideas of his former teacher Howard Thurman, Catchings was working to bring about inner spiritual transformations in order to prime students for activism.Footnote 101 During their many interracial gatherings and conferences, Catchings and Student YMCA-YWCA leaders continued to use group therapy to challenge individuals’ racial prejudice and spark social action.Footnote 102

“Toward a New Strategy”: Reckoning with the Limits of Consensus Interracialism

While some student leaders were celebrating how an interracial community of acceptance could alter prejudice, developments in Mississippi and Alabama were leading Black ecumenical leaders to rethink their strategies. The brutal lynching of Emmett Till, the bravery of Rosa Parks and other activists in Alabama, and white Southern legislators’ defiant response in the “Southern Manifesto” rendered the consensus-claiming liberal gradualism that many white Protestants preferred increasingly untenable.

In the spring of 1956, as the initial three-year grant and its stipulations that Student YMCA-YWCAs “develop understanding, friendship and common interests across racial lines” came to an end, Maynard Catchings had the freedom to imagine and propose new possibilities (Figure 9).Footnote 103 In the middle of the Montgomery bus boycott in the spring of 1956, Catchings wrote an editorial in the Student YMCA-YWCA magazine urging students “toward a new strategy in race relations.” To meet the demands of the present, Catchings recommended that ecumenical Protestants “continue the older strategy but add to it.” Echoing Height and Haynes but with even greater urgency, Catchings insisted that YMCA-YWCA interracial conferences and discussions could no longer prioritize the creation of interracial friendships. They must also facilitate increased coordination with other student groups working for integration in order “to influence the power structures.”Footnote 104 While Catchings continued to support interracial exchange, discussion, and friendship for their capacity to eliminate individual prejudice, he believed that the Student YMCA-YWCA must simultaneously advocate for changing systems of oppression. The latter approach did not necessarily flow out of the former in a step-by-step fashion—the “steps” had to be taken concurrently.

Figure 9: Backed by a $45,000 grant, Catchings spent the early 1950s leading interracial discussions and workshops in hundreds of Student YMCA-YWCAs. Beginning in 1956, Catchings urged students to meet the demands of the moment and shift from an overreliance on talk-first activism. “L. Maynard Catchings meeting with the Southern Regional Student Conference at Blue Ridge. Work group on the Christian amid racial and cultural tensions. 1952 – first year both YMCA and YWCA held only official regional conferences at Blue Ridge,” by Edward L. DuPuy, courtesy of Kautz Family YMCA Archives, University of Minnesota, http://purl.umn.edu/77727 (accessed Dec. 23, 2021).

Catchings's increased concern about the limits of consensus politics amidst an escalating civil rights movement motivated his turn from talk-first activism. In an unpublished pamphlet from the fall of 1956, Catchings argued that striking the proper balance between judgment and mercy remained a fundamental difficulty for a “community of acceptance.” In the past three years, Catchings had observed that many Christian students intellectually supported integration but did not actively work toward it. The problem, according to Catchings, was that an all-inclusive community of acceptance could be too accepting. “Personal devotion to an idea of community which includes those who believe in racial segregation as well as those who oppose it, makes it difficult for one to make an incisive thrust toward racial integration,” Catchings reasoned. A student's desire to respect everyone made him “less sensitive to God's call on him for a radical social witness.… With all standing in need of salvation, who is he to attack others, however wrong their positions may be.”Footnote 105 Catchings lamented how a community's emphasis on the acceptance of all people—originally intended to eliminate segregation with its radical inclusivity—could easily morph into an acceptance of all opinions, thereby undercutting the community's prophetic witness.

To avoid this fate, Catchings encouraged Christian students “devoted to racial equality” to surround themselves with a “nourishing community.” He hoped that these smaller communities of like-minded students would provide needed support and encouragement for students as they attempted to integrate their university and surrounding communities. Catchings came to believe, in other words, that smaller “nourishing communities” of activists would be far more effective in the “struggle for community and freedom” than larger “accepting communities” that emphasized forgiveness at the expense of freedom.Footnote 106 Catchings spent the next two years cultivating nourishing communities at Student YMCA-YWCAs around the nation. Over the next decade, many of these Student YMCA-YWCAs became epicenters of the civil rights movement on their respective campuses.Footnote 107

Other Black ecumenical Protestant leaders and their respective institutions also came to see the shortcomings of previous methods. After completing nationwide listening tours following the student sit-ins of the 1960s, YWCA national leaders—including Edith Lerrigo, a white woman who had worked with Catchings in the 1950s—concluded that the civil rights movement rendered their step-by-step program “inadequate.” Dorothy Height, by now the President of the National Council of Negro Women, helped craft the YWCA's “Action Program” in 1963, as well as its “One Imperative” program to eliminate racism “wherever it exists and by any means necessary” in 1970.Footnote 108 1963 also proved a crucial year for the successor to the FCC, the National Council of Churches (NCC). Animated by Martin Luther King Jr.'s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” and the escalating freedom struggle more broadly, the NCC pivoted to a more activist approach with its formation of a Commission on Religion and Race in 1963. The NCC proved influential in the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Freedom Summer, and the Delta Ministry.Footnote 109

Thus, the groundswell of freedom that has come to be known as the civil rights movement forced ecumenical Protestantism's national leaders to rethink their ideas about societal transformation. Many came to believe that prioritizing interracial discussion, friendship, and unity undermined ecumenical Protestantism's prophetic witness. They reasoned that ecumenical Protestants could not be effective agents for liberation if they continued to cling to a sequential process that sought consensus at every step. Consequently, Black ecumenical leaders and their institutions ceased insisting that interracial friendship and dialogue were the first steps to transforming society.

While Black ecumenical leaders and their institutions had come to question the merits of talk-first activism, the idea continued to appeal to Americans across the country. By the mid-1960s, the racial gradualism of talk-first activism appealed to local ecumenical laypersons who increasingly disagreed with their national leadership's recent embrace of bold steps for civil rights.Footnote 110 Moreover, due especially to Allport's Nature of Prejudice, talk-first activism had moved well beyond ecumenical Protestant circles. Described by scholars in 2005 as still the “most widely cited work on prejudice,” the book helped talk-first activism endure for decades to come.Footnote 111 Thus, while Black ecumenical leaders may have called for moving toward new strategies, talk-first activism—the idea that they had helped seed and spread—had moved beyond their control and would not be uprooted. In the sixty years since, Americans have continued to call for friendship, dialogue, and discussion across lines of difference as the first steps toward eliminating injustice.Footnote 112

Conclusion

A longtime advocate for freedom, civil rights, and intersectionality, Dorothy Height passed away at the age of ninety-eight in April 2010. A few days later, the nation's first Black president delivered the eulogy for the woman he referred to as the “godmother” of the civil rights movement.Footnote 113 “Let us honor her life,” Obama concluded, “by changing this country for the better as long as we are blessed to live. May God bless Dr. Dorothy Height and the union that she made more perfect.”Footnote 114 The nod to the preamble of the U.S. Constitution echoed the close of Obama's 2008 “A More Perfect Union” speech. Obama's tribute was more fitting than even he realized, as Height and her fellow mid-century Black ecumenical leaders had helped seed and spread the very idea that undergirded the conclusion of that speech.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Black ecumenical leaders such as Dorothy Height transformed how Americans conceived of societal change. These leaders continued to believe that interracial exchange, friendship, and discussion were valuable, but they insisted these experiences had to lead to concrete social actions that would create a more Christian and democratic society. Backed by their institutions’ financial, moral, and organizational resources, Black ecumenical leaders and their writings crisscrossed the nation spreading their new gospel of talk-first activism. With its gradualism, Christian and democratic rhetoric, and natural alliance with the growing field of social psychology, talk-first activism thrived during the early Cold War. While the civil rights movement made it clear to Black ecumenical leaders and some of their white allies that a consensus-driven, step-by-step approach to dismantling racism was too slow and ineffective, the idea that friendship and exchange across difference “is where the perfection begins” has continued to flourish outside the institutions that originally nourished it. Thus, while Black ecumenical leaders successfully subverted the idea that facilitating interracial exchange was the “final step” in ending discrimination, they unintentionally cemented the idea that friendship and dialogue were the “first steps” in making a more just world.