In 1976, in an affirmative action lawsuit that had not yet gained national attention, the California Supreme Court decided that the University of California was not allowed to consider race as a factor in the admissions process. University of California lawyers appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which had declined to rule on a similar case involving the University of Washington a few years earlier.Footnote 1 In 1978, the Supreme Court issued a split opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. The Court’s four liberal justices, joined by the swing vote of Justice Lewis Powell, found that the Constitution permitted the consideration of race in admissions. But four conservative justices, also joined by Justice Powell, found that the plaintiff, Allan Bakke, had been discriminated against as a White applicant who was twice rejected by a medical school that gave “preferential treatment” to minority applicants, a violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This unusual outcome meant that a single justice determined the fate of a policy issue that had “convulsed and deeply disturbed” the Supreme Court as well as the nation over the previous year.Footnote 2

Several years before the debate over affirmative action convulsed the nine justices, Bakke’s lawsuit galvanized Mexican Americans in California. Latinos as a group had gained more than anyone in the nation from the special admissions programs the plaintiff aimed to dismantle.Footnote 3 When Bakke filed his lawsuit in 1974, the number of Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans enrolled in U.S. medical schools and law schools was still very small, but it was more than 500 percent higher than it had been just five years earlier. Combined enrollments of Mexican American and Puerto Rican undergraduate students across the country nearly doubled in the same period. In California, where the Mexican American population was almost 20 percent, the gains were even bigger.Footnote 4 In a brief submitted to California’s Supreme Court in the Bakke case in 1975, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) recounted over several pages the remarkable increase in opportunity for Mexican Americans generated by special admission programs.

MALDEF lawyers asserted in the brief that affirmative action represented “one of the most important civil rights issues since that posed by Brown.”Footnote 5 Indeed, Chicano and Puerto Rican legal activists and higher education advocates had been working diligently since the early 1970s to ensure the survival of policies focused on equality of educational opportunity. When the Bakke case threatened to end these new pathways to higher education in the mid-1970s, Latino lawyers, academic leaders, and student activists drafted legal briefs, formed statewide committees, and took to the streets. Mexican Americans in California led the way, mobilizing as soon as Bakke was filed in a state trial court. When it looked like the case was headed to the Supreme Court, Chicano and Puerto Rican activists in the East and Midwest joined the opposition, working to shape the national discussion leading up to the 1978 Supreme Court decision. The nation’s newest and fastest-growing population of university students and higher education advocates positioned themselves at the leading edge of the strategic defense of affirmative action because they saw how much they had to lose. They were fighting for the survival of institutions and points of access to higher education that their generation had played a substantial role in creating.Footnote 6

Often in collaboration with their Black counterparts, Latino legal scholars and organizations argued forcefully for the necessity of protecting affirmative action as a remedy to ensure the survival of the equality of educational opportunity promised but not yet achieved by Brown, and they made powerful and coordinated arguments to demonstrate the constitutionality of affirmative action. Yet when Bakke was decided by the Supreme Court in 1978, it was the rather vague benefits of “diversity” that proved the pivotal justification for affirmative action as national policy. “Genuine diversity,” wrote the moderate Justice Powell, author of the deciding opinion, provided campus communities with “a broad…array of qualifications and characteristics of which racial or ethnic origin is but a single though important element.”Footnote 7 Very quickly, this version of affirmative action replaced the vision advanced by Latino and Black advocates: a reparative policy that, they argued, could open up foreclosed opportunity and remedy some of the damage caused by generations of racial discrimination.

For Latinos, exclusion from helping define the future of affirmative action was a particularly frustrating setback. Major civil rights questions in this era were usually analyzed in black and white terms, meaning that Latinos’ perspectives were less likely to be heard and considered—even though, in many parts of the West, Latinos comprised the plurality or even majority in the cities and towns where they lived.Footnote 8 Advocates and activists had been building organizations around the country since the 1960s to protect Latinos’ rights to bilingual voting, equal schooling, and bilingual education, adding distinctive perspectives to debates over civil rights.Footnote 9 But the group had been labeled “the invisible minority” by bureaucrats and journalists a decade earlier, and its leaders and representatives were still struggling to counter that image. Just after the Bakke decision was announced in 1978, Jack Greenberg, the legal director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, wrote in The Nation that the case boiled down to a ubiquitous and timeless issue: “‘Who gets what? Or, how [to] distribute power, prestige, and wealth?’” Researcher Carlos Haro, an administrator at the Univeristy of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Chicano Studies Center, observed that for Latinos, affirmative action was a tool to protect something even more basic: their fair share of opportunity in a nation whose prosperity they worked hard to advance.Footnote 10

Latinos’ lack of voice during the unfolding of the Bakke case meant that they reached the end of the 1970s with less chance than they might have had at changing the unequal distribution of power, prestige, and wealth in the United States. In the decades since, it has also resulted in a distortion of the historical narrative about the defining civil rights issue of the 1970s. Among the scores of major scholarly analyses of the Bakke case, none has acknowledged the vital participation of Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans in this first major round of what would become an ongoing battle over affirmative action.Footnote 11 A more accurate history of these policy negotiations in the 1970s allows us to see the unacknowledged contributions of participants who would be deeply affected by their outcome. It pushes us to focus on the actual gains and probable losses for a large group of Americans who fought hard to achieve one of the core promises of the civil rights movement: an equal chance at an education.

Special Admissions in Higher Education

The original concept of compensatory social programs had been developed in the early 1960s by National Urban League director Whitney Young, although most White policymakers and politicians ignored the core elements of his “Marshall Plan for racial justice” until they confronted violent social unrest in the late 1960s.Footnote 12 In 1967, after four summers of rioting in urban ghettos—most of them African American communities, although riots exploded in dozens of Puerto Rican and Mexican American neighborhoods too—President Johnson convened the Kerner Commission to study the causes of the riots. The commission report, issued in 1968, came to the obvious conclusion that rioters were frustrated at the slow pace of civil rights reform on issues like police brutality, school segregation, as well as housing and employment discrimination. The Johnson administration took seriously the report’s recommendation to “remove arbitrary barriers to employment of ghetto residents.” Despite Nixon’s conservatism on questions of “law and order,” his administration would follow the same basic logic of crisis management in the early 1970s.Footnote 13

The Kerner report mentioned “the Spanish speaking” only twice in more than 300 pages, a notable oversight given the fact that there were millions of people in this category suffering from the very conditions detailed in the report. However, despite their exclusion from the policy conversation, Latinos in many parts of the West and in a handful of Eastern and Midwestern cities with large Puerto Rican and Mexican American populations were beginning to benefit substantially from the special admission programs that many colleges and universities implemented. And within a few more years, a new world of opportunity was emerging for Latinos through a combination of policy and activism: organizing by college students who demanded the creation of Chicano, Puerto Rican, and Third World Studies programs and by the scholars who founded and taught in those programs; and demonstrating by thousands of Mexican American high school students in Los Angeles, Denver, South Texas, and beyond who demanded equal resources in their schools, in part so that those who wanted to could make it to college.

When Allan Bakke applied to the medical school at the University of California at Davis (UCD) in 1972, at age thirty-three, admissions practices in higher education were beginning to change in response to demands for greater equity across the United States. Bakke had served as a Marine Corps officer in Vietnam, gotten a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, worked as a research engineer at the National Aeuronatics and Space Administration (NASA), and then decided that his calling was medicine. Despite good grades and test scores in addition to his work experience, Bakke was rejected from eleven programs over the course of two years. He knew that his age was a liability. In that era, medical schools made no effort to hide their strong preference for applicants under thirty; a UCD admissions official had written to Bakke, in response to a question about his age, that “The Committee believes that an older applicant must be unusually highly qualified if he is to be seriously considered.”Footnote 14 Before Bakke applied to UCD a second time, he met with an admissions officer who explained that the university’s special admissions program set aside sixteen out of one hundred available admissions spots for applicants who were identified as disadvantaged; all admitted through this program thus far were members of underrepresented minority groups.

The special admissions program had been developed in 1969, just three years after the medical school opened its doors with forty-eight entering students. The program was a response to increasing pressure on universities to improve access for marginalized groups, and it resembled admissions strategies recently adopted by many other professional schools.Footnote 15 The program at UCD medical school was administered by a Task Force comprised of Black, Mexican American, and Asian American faculty and students. Although the special admission program did not exclude White applicants, of the seventy-two students admitted by the Task Force between 1970 and 1974, all were Mexican American, Black, Asian American, or Native American. On the other hand, according to the chair of the Task Force, minority candidates who showed no evidence of disadvantage were reviewed by the regular admissions committee, and some were admitted that way.Footnote 16

In a letter prior to the meeting Bakke had requested, the UCD admissions officer, a thirty-year-old White man, had implied that he was personally opposed to “admissions policies based on quota-oriented minority recruiting.” He suggested that Bakke look into the case DeFunis v. Odegaard, which had recently challenged an affirmative action program at the University of Washington law school. In the thank you note Bakke sent the following week, he wrote, “Our discussion was very helpful to me in considering possible courses of action.”Footnote 17 After he was rejected after a second admissions cycle, in 1974, Bakke filed a complaint against the university in California Superior Court.

The lawsuit Bakke filed in June 1974 alleged that, in treating his application differently because of his race, the university had violated his Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection of the laws and had violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which stipulated that no program receiving federal funding could discriminate on the basis of race or color. Bakke’s lawyer, Reynold Colvin, asserted that the university’s goal in setting aside the sixteen admission spots did not justify the practice of excluding members of a certain racial group from consideration for those spots. The university responded that Bakke had been rejected not because the special admission program robbed him of fair treatment but because the score admissions officers assigned him as an applicant was not high enough to compete with the other highly qualified applicants in the pool. The university argued that the special admission program complied with the law, since a “compelling state interest” justified the consideration of race in admissions decisions.Footnote 18

In his ruling in spring 1975, California Superior Court Judge Leslie Manker concurred with Colvin’s assessment that the university’s admissions program relied on a quota, and that this policy thus relied on an “invidious” form of racial discrimination that violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.Footnote 19 Judge Manker also determined that there was no clear evidence that Bakke would have been admitted even in the absence of the special admission program. Therefore, he rejected Bakke’s petition to be admitted to UCD, but told the university that Bakke’s application should be considered again without consideration of his race. The question of whether programs like UCD’s relied on “quotas” or “set-asides” had been debated since the earliest introduction of affirmative action, first in employment and then in higher education admissions.Footnote 20 Both parties in the lawsuit, dissatisfied with the district court’s decision, appealed to the California Supreme Court.

The progression of the Bakke case through California state courts coincided with an increasing presence of Mexican Americans working in higher education, which was, in turn, a direct result of the Chicano student movement that had swelled throughout California and the Southwest in the late 1960s. By 1975, there were at least twenty programs in Chicano Studies in California state universities and community colleges, and that growth meant that scores of Mexican American academics were hired to expand, administer, and teach in these programs. Most of these Mexican American faculty members and administrators were not just pursuing academic research and nurturing the growing group of students that had gained access to the state’s colleges and universities. They were also busy with institution-building—growing academic programs, ensuring enrollments robust enough to justify them to their universities’ administrations, and constructing networks of Chicano academics throughout the state.Footnote 21

This new wave of institution-building in academia was supported by, and in some cases modeled after, the many Mexican American advocacy organizations that had emerged in California and elsewhere in the West over the previous decades, and in increasing numbers since the early 1960s. The Mexican American Legal and Defense Fund (MALDEF) was a relatively new organization at the start of the Bakke case, and it would play a central role in the action of the case all the way up to the Supreme Court in 1977. MALDEF had been founded in 1968 by activists in Texas who identified the need for an organization that could address the interrelated civil rights problems of Mexican Americans—job and wage discrimination, police brutality, unequal education, school and housing segregation, voting rights—and within a few years, by 1972, had opened an office in San Francisco. Three years later, MALDEF was one of eight organizations to submit amicus briefs to the Supreme Court of California on behalf of UCD, arguing for the constitutionality of its special admission program.Footnote 22

Building a Defense of Affirmative Action

Mexican American civil rights organizations had been watching the development of a legal challenge to affirmative action in university admissions for several years before Bakke initiated his lawsuit in 1974. In 1971, a White applicant to the University of Washington Law School, Marco DeFunis, filed a discrimination suit after being rejected twice. DeFunis’s lawyer argued that the university’s approach to its new minority admissions program—resulting in the admission of a number of minority applicants with a lower admissions ranking score than DeFunis’s—represented a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. A Washington Superior Court judge sided with DeFunis and ordered that he be admitted to the law school class starting in fall 1971. Meanwhile, the university appealed to the Washington Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court’s order because it found that the university had a compelling interest not just in reversing a proven pattern of past discrimination, but also in reducing racial imbalance in the legal profession by increasing access of minority students to law school.Footnote 23

DeFunis appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. The handful of amicus briefs submitted in support of DeFunis argued that the Constitution required a “colorblind” approach to law and that affirmative action programs were unconstitutional because they were fundamentally reliant on race-based quotas, which, the briefs argued, produced “reverse discrimination.”Footnote 24 Nearly two dozen amicus briefs—an unusually large number at the time—were submitted on behalf of the University of Washington by leaders of a wide range of Black, Latino, and women’s groups, labor unions, civil rights and civil liberties organizations, professional societies, academic associations, law schools, and universities. They reflected a consensus view that affirmative action programs offered the only viable remedy for historic discrimination and patterns of exclusion from jobs and higher education; and that because most such programs employed goals rather than quotas for increasing minority enrollment, they did not violate laws against discrimination.

MALDEF attorneys collaborated on an amicus brief with lawyers for the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund (PRLDEF), formed just two years earlier, along with representatives of organizations of Mexican American and Puerto Rican lawyers and law students. This would be the first joint effort by Mexican American and Puerto Rican leaders to help shape the legal debate about a major civil rights issue. MALDEF and PRLDEF would go on to work together on dozens of cases throughout the decade, with particular successes in their coordinated campaigns to protect bilingual education and extend voting rights for their constituencies.

The joint brief opened by pointing out that the DeFunis case represented the Court’s first opportunity to address the constitutionality of a state-sponsored affirmative action program. It went on to explain how “pervasive and historic deprivations,” which affirmative action was designed to correct, had been suffered by Latinos as well as African Americans and that “[t]he Court should…rule that government is not barred from recognizing race and ethnicity in designing programs to eliminate [these harms] from our society…” MALDEF and PRLDEF lawyers, concurring with their African American counterparts, argued that the Court should use a standard of review that distinguished between invidious discrimination and “benign discrimination.” The distinction rested on a definition of “benign racial classification” that was central to legal scholarship on civil rights dating back several decades.Footnote 25 The Latino lawyers also emphasized the problem of bias in the standardized tests that colleges and graduate programs relied on as a criterion for admission. They cited a growing body of research on this problem—some of it, notably, conducted by the College Board, which developed and administered standardized admisssions tests in the United States.Footnote 26

After considering all the arguments presented in DeFunis, the Supreme Court decided, five to four, that the case was moot because DeFunis would soon be graduating from law school. This meant that the Court would not address the merits of the case, nor would it issue an opinion. Four of the justices disagreed with this decision; Justice Brennan, who wrote a dissent for the four, argued that “few constitutional questions in recent history have stirred as much debate and they will not disappear. They must inevitably return to the Federal courts and ultimately again to this Court.”Footnote 27 It would not take long for Brennan’s prediction to be proven correct. Allan Bakke received his second rejection letter from UCD the same month the Court announced it would not rule on DeFunis. Two months later, as Marco DeFunis was graduating from law school, Bakke filed his lawsuit in California.

When Bakke landed in California’s Supreme Court a year later, MALDEF once again submitted a brief to the Court on behalf of a university defending its affirmative action admissions policy. MALDEF’s brief, similar to the one it had submitted jointly with PRLDEF in DeFunis, demonstrated that there existed “clear facts of the pervasive and historical discrimination that constitutionally identifiable minorities continue to suffer in California.” (The phrase “constitutionally identifiable minorities” might have sounded opaque to a lay reader, but as the MALDEF brief explained, the Court had only recently established—in a 1973 school desegregation case—that Latinos in the United States were part of the class of people harmed by racial discrimination and therefore eligible for remedial action.Footnote 28 ) The result of this discrimination was a “critical shortage” of Mexican American and African American doctors in California, which the state must take steps to correct. Thus, argued MALDEF, the development of a race-conscious admissions program at the UCD medical school met the legal test of being justified by a “compelling state interest.”

By the time MALDEF was drafting this second major brief on affirmative action, its lawyers could draw on data and reports on college access produced by a growing networks of Mexican Americans working in higher education in California and throughout the Southwest. Shortly after the lower court ruled in the Bakke case in spring 1975, a group of faculty members and administrators based in universities in California, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, Colorado, and Washington convened a symposium on the status of Chicanos in higher education. A major topic of discussion was the problem of bias in standardized testing, which MALDEF and PRLDEF had raised in their joint brief in DeFunis. (Although more evidence of bias in standardized testing had accumulated over the previous couple of years, MALDEF lawyers chose not to discuss the issue in their Bakke brief, which was tightly focused on the issue of “compelling state interest.”)Footnote 29 The California legislature’s Permanent Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, established in 1972, issued a major report a few months later showing “inequities” in college access affecting Mexican Americans that representative John Vasconcellos, chair of the subcommittee, called “disturbing.” The report noted that, “despite significant progress…access to college remains unequal,” with particularly damaging outcomes for “high achieving low income [high school] graduates.”Footnote 30

The California Supreme Court Decision and “el Grito de Bakke”

The California Supreme Court announced its decision in favor of Alan Bakke on September 16, 1976. This happened to be the date Mexicans celebrated their national independence and memorialized the “Grito de Dolores,” the call to arms that marked the start of Mexico’s successful overthrow of Spanish colonial rule in 1810. It was a coincidence that some regarded not as an accident but as a historic challenge: now Mexican Americans in California must issue their own grito against the injustice of this attack against their recent gains in higher education access. Judge Stanley Mosk had written in his opinion that the university’s special admission program “violates the constitutional rights of nonminority applicants” because it gave preference on the basis of race to minority applicants who were “not as qualified for the study of medicine as nonminority applicants denied admission.”Footnote 31 For Mexican Americans across the state with any connections to higher education or with aspirations to attend college, this characterization of minority applicants echoed the arguments of school district officials who, a few decades earlier, had explained that they assigned Mexican American children to separate schools because they were less academically capable than their White peers. For those who had been part of or witnessed walkouts and other civil rights protests over the previous decade, Judge Mosk’s decision was a provocation.Footnote 32

Mexican American academic leaders and legal experts began formulating a response as soon as the opinion was announced. Within a few weeks, several dozen faculty members and administrators representing a handful of California’s public universities had laid the groundwork for what would become the Chicano Task Force in Higher Education, which would serve in an advisory capacity to MALDEF as it continued to provide legal guidance in response to the Bakke challenge. “Many things are being said and done in the name of the ruling that are highly detrimental to our goal of maintaining and improving Chicano access to higher education and the professions,” task force leaders wrote to MALDEF.Footnote 33

The first order of business the task force set for itself was to persuade the university’s board of regents not to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. This was on the advice of MALDEF legal director Peter Roos, who predicted that, if Bakke were to be heard by the Supreme Court—which had shifted to the right with the appointment of four justices during the Nixon administration—“their decision will be more damaging” than the state high court ruling. “At least the California Supreme Court did leave some loopholes,” Roos said; special admission programs could remain in place as long as they were based on criteria like “disadvantage” rather than on ethnicity or race.Footnote 34 The other major reason Roos advised against appealing the Bakke case to the Supreme Court was that the university’s lawyers had failed to fully develop the facts of the case, particularly regarding the patterns of exclusion that existed prior to the establishment of the special admissions program. This omission would hinder the defense in its efforts to prove that the university policy was designed to correct the harmful impact of discrimination.Footnote 35

On all of these points—that this was the wrong case to bring to the Supreme Court, and that the prospective appeal was unfolding at the wrong time, before the implications of the state supreme court opinion could become clear—Mexican American leaders in California were closely aligned with their Black counterparts who were also mobilizing in response to the state court ruling.Footnote 36 Legal scholar Derrick Bell, one of the most prominent members of the National Conference of Black Lawyers (NCBL)—he had argued dozens of school desegregation cases for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in the 1960s then became Harvard law school’s first Black tenured professor—wrote separately to the chair of the board of regents with a different argument. Bell emphasized the ethical and philosophical reasons to scrap the appeal, urging university officials to take seriously the concerns of members of the minority groups who would be most affected by a high court decision against affirmative action. They had so much to lose, and with a shaky case like Bakke, “many, if not most…are unwilling to take this risk.”Footnote 37

What was at stake was the decade’s most important tool for the advancement of civil rights. One of Bell’s NCBL colleagues warned that Bakke “has awesome implications for admission programs across the country” and that a Supreme Court decision against the university “could effectively destroy the programs and with them the hopes and aspirations of millions of Americans.” As MALDEF legal director Peter Roos asserted in his first public comments about the case following the decision in September, the California Supreme Court had issued its own anti-affirmative action “grito”—one that ultimately, he predicted, would have the effect of “barring all minorities from access to higher education.”Footnote 38

Student Protest and Higher Education Access

Roos’s audience did not hear his stark assessment as an exaggeration. The expansion of affirmative action programs over the previous decade had produced a dramatic increase in enrollments of Black and Latino students in both undergraduate and graduate programs throughout California and in many other parts of the country. The number of Mexican American and Puerto Rican students entering college across the nation had increased by 50 percent during the previous four years alone; over the previous decade, the numbers had more than doubled.Footnote 39 The first phase of this increase was a result of the antidiscrimination requirements of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which spurred the development of “bridge” programs designed to help motivated students from poor school districts get to college.Footnote 40 Within a couple of years, universities began implementing more structured affirmative action programs in their admissions process.

Another source of momentum driving the rise in enrollments was the wave Latino student activism beginning in the late 1960s. African American students had begun building campus-based organizations for civil rights and racial justice starting in the 1940s, then captured the attention of the nation with their lunch counter sit-ins that became a turning point in the national civil rights movement in 1960. These students served as a model for the small but growing populations of Mexican American and Puerto Rican college students by the mid-1960s.Footnote 41 The antiwar, free speech, and Black Power movements inspired even more radical critiques among young Latinos. In the Southwest, the achievements of the United Farm Workers movement and the growing celebrity of its primary leader, Cesar Chávez, made Mexican Americans’ struggle for civil rights visible to the nation for the first time; then a charismatic political activist based in Colorado, Rudolfo ‘Corky’ González, helped connect the concerns of migrant workers and urban youth through his organization Crusade for Justice in 1966. Scores of Mexican American student organizations had emerged on college campuses in Southern California, Texas, and elsewhere in the Southwest by 1967.Footnote 42

1968 was the turning point. That spring, Mexican American high school students in Los Angeles staged a series of demonstrations and walkouts to demand better resources for their schools, an end to discriminatory treatment by White teachers and administrators, and the development of bilingual programs. A teacher and Chicano rights activist named Sal Castro had encouraged discontented students to mobilize, and he introduced them to groups of Chicano university students in Los Angeles who had similar concerns—and who had themselves recently experienced the kind of discriminatory treatment in the city’s schools that the younger students were protesting. Some of the university students would join high school student walkouts, called “blowouts” by the participants. The high school students’ actions were more focused on conditions in their schools than on access to higher education access per se, but involvement in the protests motivated many young people to continue their education beyond high school. According to Carlos Haro, an undergraduate at the time who later became the associate director of the Chicano Studies Research Center at UCLA, the college students were inspired by the courage and vision of the younger activists; that spring they began formulating their own demands for racial justice at UCLA.Footnote 43

Also that spring, Latino students at San Francisco State College began collaborating with Black and Asian American students to demand the hiring of more minority faculty members and to build solidarity across marginalized communities. By the fall, the students had founded the Third World Liberation Front and initiated a strike on campus—a series of daily rallies that lasted for five months—pressuring the administration to establish a School of Ethnic Studies. Student organizers at UC Berkeley followed suit, forming their own Third World Liberation Front and persuading the Berkeley administration to create an ethnic studies program. Similar successful actions unfolded at UC San Diego and many other California campuses over the next year. At the City College of New York, Black and Puerto Rican students, making demands similar to those of their West Coast counterparts, staged a major strike that shut down their campus for two weeks in spring 1969; soon other City University campuses were involved.Footnote 44 Throughout the next year, Latino students at dozens of other colleges and university campuses across the country were meeting, organizing, and demonstrating, and by 1970, most groups had persuaded their campus administrators to agree to the creation of Chicano, Puerto Rican, or Third World Studies departments or programs.Footnote 45 Younger students were also part of the wave of activism: during the same month that City College students shut down their campus, high school students in Crystal City, Texas, and Denver, Colorado, organized high-profile walkouts that got national attention.Footnote 46

In addition to demands for ethnic and Third World studies programs, the other major goal of these student activists—increasing Latino students’ access to higher education—was harder to achieve in the short term and required sustained pressure on both campus administrators and public officials. Seeing the long road ahead, Chicano student leaders at colleges and universities across California worked to institutionalize a network of activists to facilitate the work of leaders on their individual campuses. A group of twenty or so gathered at UC Santa Barbara in fall 1969 and drafted a resolution, “El Plan de Santa Barbara,” to establish a permanent network of Mexican American campus groups. The group named itself MEChA, El Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (Aztlán was the homeland of Aztec peoples). MEChA’s mission was to draw Chicano students into the movement not just in California but around the country. Its members developed important connections to a range of other activists in the growing Chicano movement—among the proliferation of radical groups emerging in Southern California but also with cross-regional or national groups like the Brown Berets, La Raza Law Students Association, and La Raza Unida Party (a political third party that emerged in Texas in 1970).Footnote 47

Soon after the California Supreme Court’s finding that the affirmative action admissions program at UCD was unconstitutional, MEChA’s leadership wrote to Governor Ed Brown expressing the urgency of their concern that Mexican Americans were “uniquely underrepresented in every sector of higher education in California” even after “years of effort by the Mexican community to bring about change.” Given the tenuousness of Mexican American students’ gains in higher education and the ongoing problems of discrimination and exploitation, MEChA leaders could only see the landmark ruling by the California Supreme Court as a “landmark reversal.”Footnote 48

Other student protesters echoed these concerns about the Bakke decision. Student activists wrote to legislators and university administrators and sounded the alarm in campus newspapers across the state about the damage Bakke was likely to cause. In a guest column in the UCD Cal Aggie, published a few days after the decision, the campus chapter of Chicano Pre-Law Students raised suspicions about the goals that had guided the university’s handling of the case. After describing the thin factual record established by the university’s defense counsel, the authors concluded that “one wonder[s] if the University wants to stop minority admissions.”Footnote 49 The Bay Area Third World Students’ Alliance issued a position paper making the same point: “It is not surprising that the University of California would put on such an inadequate defense in light of the fact that these [special admission] programs were established only as a result of the struggles of minority students against the University. The conflict of interest involved in the University’s defense of the program that it opposed in the first place is obvious.”Footnote 50 At a rally in San Francisco that the group organized in October, 500 or so demonstrators listened as speakers repeated accusations that the UC counsel had mounted a weak case in response to Bakke’s claim. All through the fall and winter, student groups continued to meet, debate, draft letters, and plan protests, sounding the alarm about the threat to their hard-won gains in access to higher education.

Preparing for the Battle over Bakke at the Supreme Court

The regents of the University of California appealed the case to the Supreme Court in December. As the justices deliberated over whether to grant the request, they considered a handful of amicus briefs, submitted along with the university’s brief requesting the Court’s review, which emphasized various arguments for and against the question of whether the justices should agree to hear the case.Footnote 51 The longest of these briefs was submitted by a group of seventeen civil rights organizations, which included the National Conference of Black Lawyers, La Raza National Lawyers Association, MALDEF, and PRLDEF. The brief detailed the groups’ position that, despite their firm support for the UCD special admission program on the merits (that is, on the basis of its constitutional legitimacy), the case was not an appropriate vehicle for a final, national ruling on affirmative action. Because Bakke provided a “sketchy record” of fact—weakened by omissions of evidence regarding both past discrimination and the harms of bias in standardized tests like the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT)—it was the wrong case on which the Supreme Court should decide the future of such a crucial civil rights question. The Court, unpersuaded by these points, announced in February that a majority of the justices had voted to hear the case and oral argument was set for October 12, 1977.Footnote 52

Soon after the Court announced it would hear the Bakke case, NCBL sponsored an unusual gathering of legal experts. More than fifty participants, representing about forty organizations and law schools, spent a day at the University of Pennsylvania Law School discussing the legal strategies and arguments they planned to develop in the amicus briefs they planned to submit on behalf of the University of California in the Bakke case. The 300-page transcript of the twelve-hour event displayed the range of expertise of the participants—constitutional law, higher education policy, legislative strategy—and their determination to collaborate in defense of affirmative action. In his opening remarks, University of Pennsylvania Law School dean told attendees that, while their gathering was perhaps not “unprecedented…it is at least unusual for Amici in a major constitutional litigation to try to address themselves systematically to what their most appropriate roles can be.”Footnote 53

Only a few representatives of California-based groups attended. MALDEF did not send a representative, but a lawyer for PRLDEF, with whom MALDEF would partner on its amicus brief, traveled from New York to attend.Footnote 54 Two members of UC Berkeley’s law faculty attended, as did faculty members from a range of other law schools—Howard, Temple, Rutgers, Georgetown, Wayne State, Yale, and North Carolina Central University—and university counsel from a handful of others, including the lawyer who had served as principal counsel for the University of Washington in the DeFunis case.Footnote 55

As the group discussed the arguments the various assembled representatives might make in their briefs, a number of the elements of the DeFunis case were assessed for their relevance to Bakke. The fundamental questions about the constitutionality of a race-specific approach to admissions had not changed since DeFunis filed his first lawsuit nearly six years earlier. Proponents of affirmative action policies continued to argue vigorously that the policies were a form of “benign discrimination” justified by a compelling state interest in redressing the ongoing harms of racial discrimination; conference participants discussed various ways they intended to develop this argument in their briefs.

Another issue the group discussed at length during the University of Pennsylvania conference—the problem of racial and cultural bias in standardized testing—had arisen only peripherally in the DeFunis case (although it had been addressed in several of the amicus briefs and was raised by Justice Douglass during oral argument). Standardized testing had become common in professional school admissions in the 1950s as one of multiple factors considered but had become a primary tool of admissions committees only in the mid-1960s, when elite colleges and universities saw a massive increase in application numbers as baby boomers became young adults. The Law School Admission Test (LSAT) and the MCAT became particularly important to admissions in law and medical schools as the number of applicants nationwide had nearly quadrupled between the mid-1960s and the mid-1970s. In their DeFunis brief in 1973, PRLDEF and MALDEF had noted that “there is now a great deal more than a suspicion” that traditional admissions criteria, including the LSAT, are “either culturally biased or insufficiently validated to justify exclusive reliance upon them.”Footnote 56 Justice William O. Douglas, in his dissent from the Court’s decision that the DeFunis case was moot, had spent several pages discussing the flaws in standardized tests, particularly as a measure of minority applicants’ capabilities as law students and future lawyers.Footnote 57

In the joint brief drafted by the seventeen civil rights groups early in 1977, as the Supreme Court was still deliberating about whether to hear the Bakke case, the “racially disproportionate impact of the MCAT” was highlighted as one of “most glaring evidentiary omissions” in the record of fact the university presented in its original case. By this point, the Educational Testing Service, responsible for administering and scoring the standardized tests, had been able to analyze some of the data on the disparate test results across racial groups, which it had begun collecting in 1970.Footnote 58 At the meeting at the University of Pennsylvania a few months later, a Berkeley law professor noted that he was working with his school’s Black Law Students Association to ensure that the question of testing bias would be brought into the Bakke case. Indeed, it would be the Black Law Students Association whose brief, submitted to the Court later that year, made a thorough argument that “racially biased admission tests require different interpretations for members of different racial groups.”Footnote 59

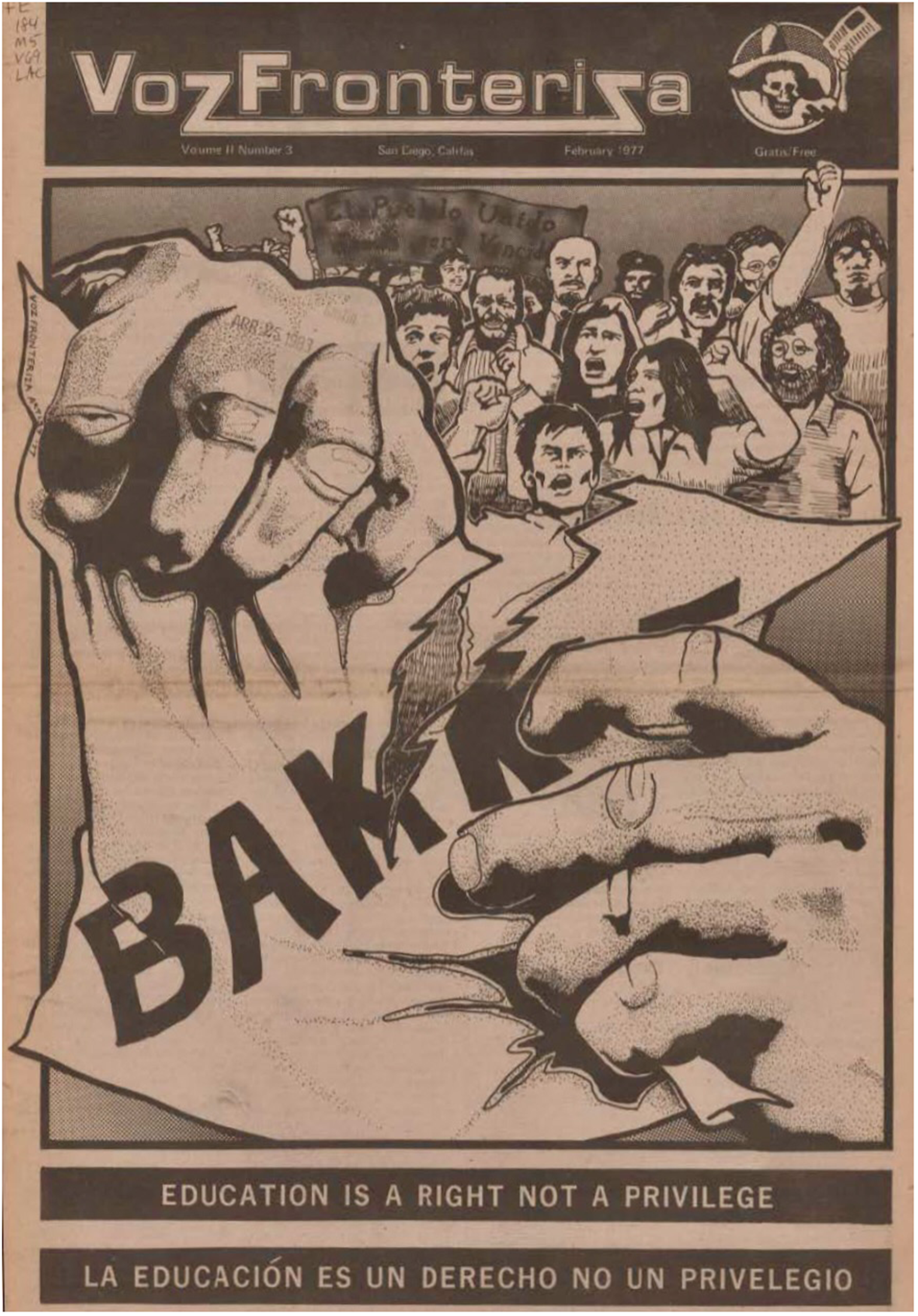

As scores of university representatives, law professors, and civil rights advocates were plotting their legal response to Bakke as friends of the court, thousands of students across California were continuing to meet, demonstrate, and write about the ominous challenge to affirmative action and the perils of the looming Supreme Court decision. Existing groups like MEChA and campus-based Chicano organizations had been the first to respond to the state supreme court decision; within a few months, dozens of new organizations had formed to join the fight to save affirmative action (Figure 1).Footnote 60 Coalitions of students and faculty unified under the banner of Third World affiliation. In May, the Statewide Coalition of Third World Law Students organized a protest of about 2,000 demonstrators at La Plaza de Los Ángeles in the heart of the city’s historic district. It ended with a rally under the banner “Education is a Right, Not a Privilege” that drew participation not just from college campuses but also from several nationalist political organizations—the Puerto Rican Socialist Party, the Union of Democratic Filipinos, and the American Indian Movement—and two Mexican American labor organizations, the United Farm Workers and the Centro de Acción Social Autónomo (CASA-General Brotherhood of Workers).Footnote 61

Figure 1. Shortly after the Supreme Court decided to hear the Bakke case, in February 1977, Voz Fronteriza (Voice of the Border), the Chicano student newspaper at UC San Diego, ran this front-page image of an anti-Bakke protest. The banner in the background reads, “El Pueblo Unido Jamás Será Vencido” (“The People United Will Never Be Defeated”). Voz Fronteriza newspaper, Rodolfo F. Acuña Collection, California State University, Northridge University Library, Special Collections and Archives, Northridge, CA.

CASA, based in Los Angeles, had gotten involved in organizing the response by Mexican American leaders and activists soon after the state supreme court’s “grito” in the fall. Since the beginning of the DeFunis case five years earlier, labor leaders around the country had understood that any decision about affirmative action in higher education would almost immediately affect employment-related affirmative action rules. The California Supreme Court’s decision in 1976 signaled the likely imposition of new constraints on employment affirmative action that would affect Mexican Americans more than any other residents in the state. CASA’s monthly newspaper, Sin Fronteras, described the Bakke case as “nothing more than a legal-judicial accommodation of the racist backlash during this extended economic crisis to preserve the privileges white people have to university education and the professions.”Footnote 62

Reporters for Sin Fronteras tracked the steady march of protests in cities throughout the state and across the country throughout 1977. Chicago was a particular focus, since a CASA chapter had been founded there by labor and community activist Rudy Lozano and others.Footnote 63 At Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) in Chicago, the number of Puerto Rican and Mexican American students had increased substantially since the late 1960s through a program called Proyecto Pa’lante—“Project Onward”—that combined a special admissions process with ongoing support for students on campus.Footnote 64 Students at NEIU had founded a newspaper, Que Ondee Sola (“May it Wave Alone,” referring to the Puerto Rican flag and nationalist aspirations for political independence), which by fall 1977 was printing extensive commentary about the Bakke case and the meaning of the legal assault on affirmative action. “If the Supreme Court rules in favor of Bakke,” warned Que Ondee Sola editors, “PROYECTO PA’LANTE would be among the first to go. Third world students would be forced to attend inner city community colleges and the major universities and colleges would be left for white middle and upper class students.” The authors of the editorial situated the Bakke case as part of a “growing reactionary movement” in the United States and called for national leadership on issues of concern to the Third World student movement in the United States.Footnote 65

At around that time, members of Marxist and Third World labor organizations based in Berkeley did just that, forming the National Committee to Overturn the Bakke Decision, which would sponsor demonstrations around the country and began planning a massive action in Washington D.C. to coincide with the presentation of oral arguments in Bakke at the Supreme Court in October.Footnote 66 Across California, demonstrations on campuses across California were practically continuous in 1977 and tended to feature faculty members who had established careers as both scholars and activists. A rally and teach-in at Berkeley, just after the announcement that the Supreme Court would hear Bakke, featured a list of high-profile speakers and drew more than 5,000 participants. Sociologist Harry Edwards, the “eloquent radical” who first called for Black athletes to boycott the 1968 summer Olympics in Mexico City, spoke about his recent denial of tenure at Berkeley despite his many accomplishments as a researcher and teacher. (The university would reverse its decision later that year.)Footnote 67 Angela Davis followed Edwards to the microphone, needing no introduction. She had been fired from her position in the UCLA Department of Philosophy in 1970 due to her affiliation with the U.S. Communist Party and in the years since had become a highly visible figure in various leftist movements.

Less well-known outside of his professional milieu at that point was Charles Lawrence III, a featured speaker at many of the major anti-Bakke demonstrations in California that year. Lawrence was a member of the law faculty of the University of San Francisco, a rising leader of the NCBL, and the primary author of the NAACP’s brief on behalf of the University of Washington in the DeFunis case. Lawrence often told crowds that the Bakke case reminded him of an old folk tale about “the goose being sued by the fox before a fox judge and a foxy jury,” an allegory that reflected, Lawrence said, “the traditional history of American justice for Black people.” Bakke represented an even greater injustice, he would say: “The judge was white, the jury was white, but this time even the defendant was white.”Footnote 68 The absence of participants who suffered from real discrimination, he meant, illustrated their exclusion not just from this particularly significant civil rights case but from the justice system writ large.

“Benign Discrimination”

The year after the Supreme Court delivered its opinion in Bakke, Lawrence published the only contemporaneous book-length account of the case, co-authored with journalist Joel Dreyfuss. Their analysis identified an additional element of distorted justice in the Fox v. Goose tale. “The great frustration that Bakke presented to minority groups was their exclusion from the preparation and defense of the case,” wrote Lawrence and Dreyfuss. Unlike the cases conceived and argued by Black attorneys in their “well-prepared legal assault on segregation” beginning in the 1930s (the authors do not mention the decades of parallel efforts by Mexican American civil rights advocates in the West), “Bakke was a defensive action, and minorities found themselves on the sidelines, reminded that despite the rhetoric of progress so popular in the 1970s, most American institutions remained solely in the hands of white men who made decisions that would profoundly affect their welfare.”Footnote 69

Once the Supreme Court decided to hear Bakke and University of California leaders began planning for what would likely be the final phase of the case, organizations of Black and Mexican American lawyers criticized the university administration for not drawing on their expertise.Footnote 70 Instead, the university tapped Archibald Cox, a Harvard Law professor who had been the solicitor general in the Kennedy administration and served as the special prosecutor of the Watergate investigation. Another of Archibald Cox’s qualifications was that he had written the amicus brief submitted by Harvard in the DeFunis case a few years earlier, supporting the University of Washington’s affirmative action program with a set of arguments that, it turned out, had made a lasting impression on Justice Lewis Powell, one of the two likely swing votes in Bakke.Footnote 71 Drawing on the experience of three Harvard deans with whom Cox had worked over two decades, Cox emphasized in the 1974 brief the importance of diversity—broadly defined in terms of racial, economic, and experiential differences—in maintaining the excellence of a university’s student body.Footnote 72 Cox was probably unaware that Justice Powell was so interested in diversity as an argument for affirmative action. In the petitioner’s brief Cox drafted in the Bakke case in 1977, he mentioned but did not focus on the importance of “the range of significant diversities” that university admissions could help create on their campuses.Footnote 73

Instead, Cox made the same basic argument that Black, Mexican American, and Puerto Rican advocates developed in their own briefs that year: that “the legacy of pervasive racial discrimination” in education and the professions burdened minority groups “as well as the larger society,” and that the effects of discrimination could not be “undone by mere reliance on formulas of formal equality.” In other words, “colorblind” policies could never repair the harms caused by centuries of racism and discrimination. In his brief, Cox described the potential beneficiaries of affirmative action as “black, Chicano, Asian, and Native American”; with “Chicano,” Cox was relying on the description of Latinos that was at that point commonly used by Mexican American activists and students in California. This usage made sense in the state context, since the overwhelming majority of California’s Latinos were Mexican American or Mexican immigrants. But relying on “Chicano” as Cox did was problematic. First, there was significant generational tension related to the term in the Mexican American community. Older Mexican Americans rarely used it and, in some cases, actively objected to its usage. More important, the term excluded Puerto Ricans, who comprised the second-largest Latino group in the United States and who experienced racism and discrimination in their own regional contexts.

Puerto Rican and Mexican American advocates collaborated on the separate briefs they filed in Bakke, laying out complementary arguments that they had introduced together in the joint brief written for the Supreme Court several years earlier in DeFunis. The brief submitted to the Supreme Court by MALDEF and about ten other Mexican American organizations relied on the same two-part argument that MALDEF had made to the California Supreme Court two years earlier: that Mexican Americans, no less than Black Americans, suffered from “pervasive and systematic racial prejudice which has been incorporated into governmental policy”; and therefore, the University of California had a compelling interest in ensuring a greater presence of minority groups in medical schools and in the medical profession, which justified the Task Force admissions program.

More broadly, the brief detailed the “gross disparities” between the standard of living of Mexican Americans and other minority groups, on the one hand, and those of Whites in the United States on the other. While the Bakke case concerned social conditions and the status of medical training in California, the brief argued, these were in fact national problems. To drive home this point, the brief highlighted the warning issued by the Kerner Commission a decade earlier, following several years of dramatic urban riots: “our nation is moving toward two societies—separate and unequal.” It was an interesting decision on the part of the authors of the brief to frame this section of the brief around the Kerner Commission report, since Latinos had been omitted from the commission’s analysis despite the fact that Puerto Rican communities in Chicago and New York had also experienced major riots by the time the commission was convened.Footnote 74 (Just a few months after MALDEF filed its brief, Senator Edward Brooke (R-MA), the first African American elected to the Senate, told a Washington Post reporter, “The prediction of the Kerner Commission is coming true. But with three societies separate and unequal—black, white and Hispanic.”Footnote 75 )

Writing separately from the group of Mexican American organizations, the two most prominent national Puerto Rican civil rights organizations, PRLDEF and Aspira, Inc., made similar points to establish the importance of the participation of Latino and particularly Puerto Rican groups in the litigation. The PRLDEF and Aspira brief amplified the significance of “the unmet health needs of minority communities.” Despite the acute health needs of Puerto Rican communities, with a population of about 1.5 million across the United States, there were fewer than 200 Puerto Ricans enrolled in U.S. medical schools in 1976—and this represented an increase of 400 percent since 1970.Footnote 76 Because past discrimination had a “particularly devastating impact” on the ability of minority applicants to gain entrance to professional schools, the brief argued, it was legally permissible for the University to consider ethnic and racial background as one of the many factors in selecting among qualified applicants for admission. In constitutional terms, the special admissions program enabled the university to meet a “compelling state interest in remedying the consequences of discrimination and serving the unmet health needs of minority communities.”Footnote 77

The brief also reiterated and expanded on a crucial legal argument that Mexican American and Puerto Rican advocates had advanced in their joint amicus brief in DeFunis in 1974: that to call affirmative action programs “reverse discrimination” was to misunderstand the constitutional principle of equality. That is, the “equal protection of the laws” required by the Fourteenth Amendment did not require that the state treat different racial groups in the same way at all times. In fact, differential treatment was necessary in situations where a law or policy was intended to remediate existing discrimination.Footnote 78

A few months too late to be cited in the Bakke briefs, José Acosta, a law student at UCLA, published an article in the university’s Chicano Law Review making precisely this point. Acosta explored recent examples of cases in which the concept of benign discrimination had been upheld by the courts “to relieve the abuse by historical invidious discriminations.” Like many others who had defended the legal principle of benign discrimination before him, Acosta argued that a compelling state interest in reducing discrimination justified a policy that treated differently applicants classified by race.Footnote 79 Acosta also pointed out that special admissions programs that relied on race as one of many criteria should be assessed by the courts no differently than the less formalized “special admissions” process that often admitted children of alumni and donors. (This was a point that Justice Blackmun would make a few months later during the Bakke oral argument, when he noted the special consideration given to applicants who were athletes.)Footnote 80 The editorial team at Que Ondee Sola on the Northeastern Illinois campus put the point more succinctly. Far from producing or promoting “reverse discrimination,” the editors asserted, affirmative action “is reversing discrimination which continues in its inhumanity and injustice up to this day.”Footnote 81

An extraordinary amount of commentary on the ethics and legality of affirmative action was published in the months between the presentation of oral argument in Bakke and the Court’s decision on the case, which came in June 1978. A month after the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Bakke, legal scholar Ronald Dworkin observed that “[n]o lawsuit has ever been more widely watched or more thoroughly debated in the national and international press before the Court’s decision.”Footnote 82 The number of front-page articles, magazine cover stories, and opinion pieces that appeared in major publications over the following months bore this out. Justice Brennan had more or less predicted such a scenario in his dissent in DeFunis when he warned that the legal questions surrounding affirmative action “will not disappear.”Footnote 83 A small amount of commentary by Black interlocutors made it into national publications; Latinos’ perspectives were all but absent in the national media.

While the nation awaited the Supreme Court’s answer to these legal questions, members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) introduced a bill to advance equal opportunity and affirmative action—which, unlike the Bakke case itself, got very little news coverage.Footnote 84 The media’s inattention to the CBC’s affirmative action bill could have had something to do with the drama surrounding its circumstances: the legislation was proposed as an add-on during negotiations over the Hyde amendment, a controversial bill that prohibited the use of federal funds to pay for abortions. But to many of the Black and Latino scholars and activists who had been watching or trying to participate in the case would have seen, the lack of interest in the CBC’s proposal was the logical extension of Charles Lawrence’s description of the all-White Fox v. Goose case. It was also connected to what Lawrence and his coauthor Dreyfuss described as the marginalization of minority advocates in building the case against Bakke. A few years later, UCLA law professor Richard Delgado would explore this problem in a law review article, arguing that, from the perspective of scholars and advocates seeking a reparative remedy for long-standing discrimination, most White scholars’ defense of affirmative action was problematic because “it enables [them] to concentrate on the present and the future and overlook the past.”Footnote 85 Black and Latino scholars could testify in detail to the patterns of discrimination and exclusion in the past that they themselves had experienced—and that affirmative action had the potential to alter.

The Limits of Diversity

During the oral argument heard by the Supreme Court in fall 1977, U.S. Solicitor General Wade McCree, Jr.—the second African American, after Thurgood Marshall, to serve in that role—also referenced the country’s long history of racial discrimination to argue that compensatory action by government and institutions was necessary. McCree used the metaphor that Lyndon Johnson often relied on to explain the logic of affirmative action: “[W]e suggest that the Fourteenth Amendment should not only require equality of treatment, but should also permit persons who were held back to be brought up to the starting line, where the opportunity for equality will be meaningful.”Footnote 86 Archibald Cox, representing UCD, made a similar assertion about the Fourteenth Amendment in simpler terms: “there is no perceived rule of color blindness incorporated in the Equal Protection Clause.”

Cox had begun by presenting the justices with three facts to demonstrate the essential logic of the university’s action: there were many more applicants than seats in professional schools; “generations [of] racial discrimination” limited minorities’ access to higher education and professional training; and “there is no racially blind method of selection” to change the pattern of exclusion. Cox’s strategy during oral argument—focusing on the basic logic of the university’s action, emphasizing the “compelling state interest” involved and asserting its constitutional validity—took into account the two likely swing votes on the Court, Justices Powell and Blackmun. Justice Powell, appointed by Nixon, had been known as a conventional Southern conservative earlier in his career—for example, he served as chairman of the Richmond school board throughout the decade after Brown, during the years that state officials were actively defying the desegregation ruling. Yet, since joining the Court, Powell had demonstrated nuanced and sensitive views about the harms of racial discrimination.Footnote 87 Blackmun, also a Nixon appointee, had taken some liberal positions during his eight years on the Court, most notably in Roe v. Wade. But Blackmun had voted against the Supreme Court’s hearing of the Bakke case because he viewed affirmative action as a matter of “social policy” to be resolved in the political sphere, not in the courts.Footnote 88 Perhaps this is one reason that Cox only briefly mentioned the argument he had written about at length in his DeFunis brief: the broader societal goal of “improving education through greater diversity.”

Yet, of all the arguments Cox presented, it was this idea about diversity that had the most significant influence on Powell, who turned out to wield the decisive vote.Footnote 89 In late June 1978, the Court issued a split judgment in the Bakke decision. When Justice Powell announced the unusual result—six justices had filed separate opinions, none of which got support from a majority, with Justice Powell writing a tie-breaking opinion that represented his views alone—he remarked on the Court’s “notable lack of unanimity” in the case.Footnote 90 Powell agreed with the opinion of four of the justices (Stevens, Burger, Stewart, and Rehnquist, its author), who argued on narrow grounds that the UCD ’s special admission program had violated Allan Bakke’s rights under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and therefore that Bakke must be admitted to the medical school. But Powell also concurred with the other four (Blackmun, Marshall, White, and Brennan, who wrote the opinion) that, in general, university admissions programs that considered race among other factors in selecting applicants did not violate the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

Justice Marshall wrote a concurrence that challenged arguments that the Constitution was “colorblind” and asserted that the law could not and should not be colorblind in a society in which Black Americans continued to suffer from “the tragic but inevitable consequence of centuries of unequal treatment.”Footnote 91 In his own concurrence, Justice Blackmun made a similar point, though in a more circumspect tone: “I suspect that it would be impossible to arrange an affirmative action program in a racially neutral way and have it [be] successful. To ask that this be so is to demand the impossible.” As Blackmun was drafting his opinion, one of his clerks had urged the justice to read a recent article in the Atlantic Monthly by McGeorge Bundy, then president of the Ford Foundation; the clerk later recalled the article was “acclaimed by some as the best piece to appear on the subject.”Footnote 92 Although Blackmun did not cite Bundy in his opinion, he leaned heavily on Bundy’s words, first in his argument against racially neutral policy and then in his more forceful assertion that would become one of the most frequently quoted passages in the case’s 300 pages of opinions: “In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently. We cannot—we dare not let the Equal Protection Clause perpetuate racial supremacy.” With just a few words changed, this was what Bundy had written shortly after he listened to the oral argument in Bakke in the fall.Footnote 93

Justice Powell’s compromise vote meant that, as soon as the Court’s decision was announced, partisans on both sides claimed victory. Opponents of affirmative action crowed that Allan Bakke had won his case; Yale law professor Robert Bork pronounced churlishly that “the hard-core racists of reverse discrimination are defeated.”Footnote 94 University of California president David Saxon said “I consider it a victory” for the university. Attorney General Griffin Bell, speaking for the Carter administration, said the ruling was “a great gain for affirmative action.”Footnote 95

But the judgment about such a gain was based on a definition of affirmative action’s goals that fell short of the remedy envisioned by many of the people whose lives would be most affected by the Court’s decision. Powell’s singular focus on the diversity model of affirmative action had enabled what legal scholar Derrick Bell would later identify as “interest-convergence,” wherein the members of minority groups fighting to achieve racial equality for themselves “will be accommodated only when it converges with the interest of whites.”Footnote 96 The dozens of briefs filed by Latino, Black, Asian American, and Native American organizations in both DeFunis and Bakke argued for admissions programs that would create opportunity for those who had confronted both present and historical discrimination and that would also challenge assumptions about “what they call racially neutral and fair admissions criteria in higher education,” particularly the standardized tests that had been proven to produce racially disparate results.Footnote 97 In the end, however, the tie-breaking ruling by the Supreme Court simply brushed aside arguments about remedial justice.

On June 28, the day the Court’s decision was announced, a group of Chicano law students and activists in the Los Angeles area gathered at the city’s federal courthouse in protest. A University of Southern California law student told a reporter for the Spanish-language daily newspaper La Opinión that the decision was racist and would be a “giant step backward” for Chicanos. “Young Chicanos in the barrios are now going to have a much harder time getting into college and entering the professions,” he said.Footnote 98 MEChA’s counterpart in Colorado, United Mexican American Students (UMAS), issued a statement that called the Bakke decision “a declaration of war against affirmative action, the opening shot in an all-out offensive to take always all of the gains…won through the long and bitter struggle of the last 25 years.”Footnote 99 Mexican American organizations across California held planning events and seminars throughout the summer of 1978 that focused on preparing the largest group of state residents affected by the ruling—Mexican American students, parents, teachers, college advisors and administrators—for the challenges of conforming to a new set of rules in university admissions and for the rollback of the kinds of opportunities that had helped Latino students double their numbers on campuses over the previous decade.Footnote 100 Those gains had been forged over years of determined activism, and now it seemed that another generation of youth would have to find a different path to educational opportunity.

Black and Latino students all over the country worried about what the Bakke ruling would do to their tenuous gains in college and especially professional school admissions over the previous decade. Members of minority law and medical student organizations struggled to protect some semblance of equal educational opportunity, pushing to stay involved in their schools’ admissions processes. Soon after graduating, a UCLA law school alumnus, Rogelio Flores, was invited back to speak to a group of Chicano law students about his experience as a student activist during the year after Bakke. He recalled a hunger strike a group of forty students had staged in spring 1979, protesting what they regarded as faculty’s and administrators’ abandonment of their obligation to “assist Chicanos who desired to fill the legal needs of our communities.” Instead, faculty and administrators recruited minority students primarily “in order to benefit the institution.” What the small population of Chicano students were left with, he said, was “a ‘diversity’ program with virtually no…input” from the students who were most invested in institutional change.Footnote 101

Those who had predicted a dramatic reversal in Latinos’ access to higher education were soon proven right: “diversity” was no substitute for corrective action to expand opportunity. When Carlos Haro, a researcher and associate director at the Chicano Studies Research Center at UCLA, reviewed the scholarly literature and government data on Chicanos in higher education a few years after Bakke, he found a steep drop in Latino student enrollments between fall 1977 and fall 1978. Total college enrollments declined by 3.5 percent, but the figure for Latinos was nearly 10 percent (Black student enrollments declined about 7.5 percent). It was an alarming trend that emerged sooner and more starkly than most observers had feared.Footnote 102

This backsliding in higher education gains was happening during a moment that Latinos in many parts of the country regarded as an inflection point. By the late 1970s, those who had worked toward or simply tracked the progress of recent civil rights campaigns—in voting rights, school desegregation, anti-poverty reform, bilingual education—had reason for optimism. Not only had courts and policymakers supported progress on these issues; there were now many more Latino judges on the bench and politicians in elected office than there had been a decade earlier, increasing the chances that Latinos’ policy concerns would be heard.Footnote 103 On the other hand, the country was in recession, and the combination of “stagflation” and fiscal crisis in most cities with large Latino populations meant that the poor had grown poorer during the 1970s, and even many who had made it into the middle class were less secure in their socioeconomic gains.Footnote 104 In this climate, access to higher education was more important than it had ever been for Latinos aspiring to long-term economic security.

The remarkable demographic growth of Spanish-speaking groups in the United States throughout the 1970s also meant that Latinos had become increasingly significant to politicians and to businesses. By 1979, members of the media had popularized the idea that the 1980s would be the “the Decade of the Hispanic,” and soon reporters and news editors deployed the phrase in countless headlines and articles.Footnote 105 For Latinos, the optimistic framing would exact a certain cost. In its upbeat emphasis on traits that business leaders and social conservatives might value—the group’s presumptive strong work ethic and conventional family values—the campaign ignored what many, especially young people, would have regarded as the most important aspects of their experience as Americans as they transitioned from one decade to the next. Not unlike the embrace of “diversity” as a justification for affirmative action, the idea of a “Hispanic decade” emphasized the present and future benefits to mainstream society, masking the ongoing challenges of racism and discrimination. Latinos’ vigorous fight to protect their chance for an equal education was edited out of the story even before the new decade dawned.