Introduction

On February 19, 1986, 12-year-old Kathy Richmond sent a letter to Marvel Comics’ Misty. She wrote, ‘Dear Misty, I realy [sic] like to read your comic, in fact I have every one. I’m twelve, and I like your comic so much I made a suit for you. Hope you like it’. On a separate scrap of paper, she included a picture she had drawn of the title character wearing a red off-the-shoulder top, leggings, and a blue pinafore (Figure 1; Richmond, Reference Richmond1986). This letter – along with hundreds like it – was received by Trina Robbins, prolific feminist comics artist, writer, historian, and creator of Misty. Much of the correspondence from readers served as direct inspiration for textual elements – from outfits, to jokes, to entire plotlines. Something about Richmond’s submission spoke to Trina, as she scrawled, ‘Use this’, on the back of Richmond’s envelope. Sure enough, Richmond’s fashion design appeared in Misty #6, the final issue of the six-issue limited series (Figure 2; Robbins, Reference Robbins1986).

Figure 1. Outfit design submitted by Kathy M. Richmond of British Columbia, Canada.

Figure 2. A panel from Misty #6 (October 1986) includes Trina Robbins’ rendering of Richmond’s design from Figure 1.

The inclusion of Richmond’s drawing in the Misty comic is just one instance of a larger tradition of participatory culture – a cultural system where audiences actively contribute to media rather than simply consuming it – seen here in the way professional comic book creators incorporated reader-contributed content into their works.Footnote 1 This tradition emerged in 1940’s teen humour comics like Archie Comics’ Katy Keene, by creator Bill Woggon, as well as Atlas/Timely/Marvel’s Patsy Walker and Millie the Model (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022). After declining in popularity in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the 1980s saw a revival of participatory teen humour fashion comics led by former readers of the earlier titles: familiar characters and titles, such as Katy Keene and Millie ‘the Model’ Collins, returned to comics stands (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 159). Misty itself is a spin-off of the older Millie the Model series, reintroducing the now middle-aged Millie as Misty’s aunt.

Despite its limited run, Misty stands out as a particularly fruitful case for exploring the dynamic and complementary relationship between comic book readers and creators. Kathy’s and other readers’ submissions for Misty are now archived in the Trina Robbins Collection and Papers at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at The Ohio State University. John A. Walsh (Reference Walsh2022) collected data from each of the 1,026 items in this collection of correspondence to explore the readership of Misty, identifying several recurring topics in the readers’ letters. These recurring topics include requests for advice, memories of reading Millie the Model, expressions of interest in comics or fashion design as careers, and calls for the comic’s continuation beyond six issues (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 165). Underscoring the social dimension of participation, readers also discussed the involvement of friends and family in reading or creating designs for Misty. Many of these topics were directly prompted by Robbins within the comic itself, revealing the many ways in which readers engaged with the comic’s content and community (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 165–67). The present study expands on this earlier research to explore the phenomenon of reader-contributed content in teen humour fashion comics. Utilising the archival material and later recollections of select Misty reader-contributors, we trace the activist impulse driving the intricate and impactful relationships among text, reader, creator, and publisher.

The reciprocal relationship between readers and creators of comics can be understood as part of a larger ‘rhizome of comic book culture’, in which the various domains of comics creation and reception – including creators, corporations, fans, critics, and texts themselves – are interrelated and interdependent. Scott Jeffery (Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b), drawing on the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987), develops this framework to challenge traditional binaries and to emphasise the multiplicity of social and creative influences in comics culture. The concept of the rhizome, which Deleuze and Guattari borrow from botany, serves here as a metaphor for a sprawling, interconnected network without a single centre or hierarchy.

Jeffery argues that reader-text relations should themselves be figured as assemblages, defined as ‘any amount of “things” or bits of “things” gathered into a single context’ (2016, 206). In other words, an assemblage is a collection of diverse elements – people, ideas, objects, or practices – that come together in a particular moment to shape meaning. Jeffery explains: ‘A comic book is an assemblage, capable of bringing about any number of effects, and of containing assemblages within itself and forming new assemblages with readers, libraries, church hall jumble sales, bonfires and so on’ (ibid).Footnote 2 Through this lens, the reader and the creator are seen not as discrete entities but as elements in a wide network of social and creative influences.

Misty’s reader-creator-text relationships are especially complex. The inclusion of reader-submitted material in the text of Misty directly implicates readers in the multifaceted process of comics production. To speak of a reader-text relationship for comics like Misty, then, necessarily involves considering the entire participatory apparatus, that is, the assemblage of influences on reader engagement comprising not just the text but also other assemblages of comics creation and consumption – for example, Trina Robbins, the corporate publishing system, and readers’ own environments and cultures. By examining the memories and archived correspondence of Misty’s readers, the nature of this relationship becomes clearer.

This view of reader engagement with participatory comics aligns closely with contemporary conceptualisations of activism. Marcelo Svirsky, also drawing on the works of Deleuze, moves beyond the conventional understanding of activism as ‘supporting or leading social struggles’ (2010, 163), articulating the intricate dynamics between activist efforts and the systems they critique. Svirsky stresses the importance of ‘investigation’ (ibid) and ‘imagination’ (ibid, 176), through which activist actors engage in the ‘production of situational or local knowledge’ (ibid, 175). In doing so, activists critique existing norms and dominant structures to experiment with, construct, and promote alternative social practices and visions for the world.

The first section of the present study explores Misty’s participatory apparatus through this frame. Misty encouraged its readers to create new elements that intersect with the ‘official’ published text, to investigate, experiment, and imagine it anew in conversation with their own desires, cultures, and lived experiences. In doing so, readers created a virtual structure of potential textual ideas which Robbins interpreted and drew upon to compose Misty. By incorporating these reader-created elements, the text becomes a continuously evolving entity that actively resists adherence to a singular dominant narrative identity.

Moreover, readers utilised the participatory apparatus to engage in a dialectical exchange with the publisher to preserve and extend support to Misty’s creative project. These appeals demonstrate reader engagement with corporate domains within the rhizome of comic book culture: readers contended with the fact that the production of comics is not merely an artistic or creative activity; it is also a commercial enterprise that responds to market forces, aiming to create and expand markets. Marvel ultimately rejected these appeals, but the title’s cancellation motivated Robbins and her readers to seek other commercial outlets through which they could re-establish their creative and participatory culture. In this way, Misty demonstrates that activism is truly ‘an open-ended process’ and cannot be constrained simply to ‘supporting or leading social struggles’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 163).

In the second section, we move beyond the archival collection to readers’ current memories, considering how activist participatory engagement has reciprocally affected the personal development of Misty’s readers. In the short term, readers who saw their contributions realised in Misty were affected emotionally, and in some cases – especially those who received advice from Misty – their lives outside comics could have been shaped by their participation. Further, turning to more recent recollections from select readers of Misty, we explore how engagement with participatory culture could reverberate across readers’ lives. Participation in Misty could affect what readers did and how they constructed meaning in the long term: the readers with whom we communicated all indicated that their participation encouraged their own self-empowerment and even informed the trajectories of their lives and personal philosophies. Viewing Misty through these lenses of activism and memory, then, enables a deeper understanding of the complex and enduring effects of twentieth-century comic book participatory culture.

The activism of Misty

The Trina Robbins Collection and Papers at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum houses over 1,000 items of correspondence from readers, most of which include fashion design contributions for inclusion in Misty. These materials – like other inter- and extra-textual social practices such as fanzines, discussion groups, and conventions – can be understood as ‘acts of deterritorialisation’ (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b, 207), that is, taking ideas or cultural forms out of their original context and reworking them in new settings. They function as textual engagements or reworkings through which ‘the creator’s rights are superseded by the reader’s desire… [but] each is a form of production, each is an action of desire, and all are connected as a “machine of machine”’ (Sweeney, Reference Sweeneyn.d., n.p.; cited in Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b, 207). Misty further complicates this dynamic, however, by actively incorporating these reworkings into the published text.

Seen in this way, Misty’s participatory apparatus aligns closely with Svirsky’s conceptualisation of activism. From a creative standpoint, the title’s participatory structure provides a venue for ‘critical engagement with dominant forms of life’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 170): readers (re)construct textual elements according to their own lived experiences, and Trina Robbins integrates these reader-contributed elements into her own narratives, resulting in a continually evolving textual-graphical assemblage. Furthermore, in their letters, readers engage with issues beyond the creation of individual designs and narratives, advocating, for instance, that Misty adopt narrative and socio-cultural practices in comic book culture, such as extended continuity and official fan clubs. In this regard, readers’ activism extends beyond the creative enterprise of comics production and meets the (often divergent) priorities and motivations of the commercial enterprises and fan-based cultures of comics.

The participatory and activist impulse of Misty is a bulwark against complacency, stasis, and stagnation in comics. As Svirsky puts it, ‘[L]ife has an ever-changing problematic structure. Every multiplicity changes its virtual structure by way of actualisations, that is, by passing into temporary solutions…’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 169). However, he also suggests that bodies exhibit a tendency towards resisting the ‘potentiality of virtual structure’ and falling into stagnation out of passive ‘social obedience’ (ibid, 170). It is this stagnation against which activist processes push as they investigate well-established systems ‘with a view to the emergence of an alternative sociability’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 175). Participatory comics titles like Misty resist this tendency toward stagnation by actively seeking out new textual potentialities from their readers.

In doing so, creators of participatory comics necessarily must consider this multiplicity of alternative possibilities, the various re-imaginings of the text that their readers offer.Footnote 3 Of course, there were practical limits to the extent to which readers could influence and contribute to Misty, but readers nonetheless had agency in most textual elements – from feature titles, to outfits, to one-off jokes, to entire narrative plotlines. Each implementation of a reader-submitted idea functions as a ‘temporary solution’ for a textual element in Misty. On a textual level, then, the participatory apparatus is a fundamentally activist endeavour, as it diverts the comic ‘from its tendency to eternalise and deepen itself in its actual forms’ (ibid).

The collection of fan mail to Robbins provides further evidence of the activist dynamic in Misty. The collective assemblage of reader correspondence constitutes Misty’s ‘virtual structure’, as each submission promotes one or more textual possibilities. On an individual level, each submission ‘comes into being through the creation of a new series of interconnected elements as a result of alternative connections with (a) given registers of the actualised world, and (b) new imaginations’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 177). In other words, readers experiment with the textual elements of Misty by disconnecting them from their ‘official’ contexts and reimagining them anew in conversation with their own local environments and experiences. This act of imaginative reconfiguration – detaching and recombining narrative and visual elements – functions as a mode of critical engagement through which readers assert agency over the meanings and futures of the text.

Imagination here is not merely fanciful, but a constitutive force that allows readers to rework cultural forms into new configurations grounded in their lived experiences. In this context, Svirsky’s (Reference Svirsky2010) conception of activism manifests not as overt political resistance but as the production of situated, localised knowledge through imaginative engagement with cultural forms. This framing allows us to interpret Misty readers’ creative participation as a kind of micropolitical intervention. In general, micropolitical activism refers to small-scale, everyday actions that subtly reshape larger social or cultural systems. Here, that dynamic takes the form of an activist act that reconfigures the comic’s text from the ground up. Thus, Misty’s ‘activism entails an engagement in the production of situational or local knowledge’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 175) in which readers borrow material and cultural practices from their local environments and incorporate them into their own creative ideas for Misty. Indeed, each reader’s drawing or narrative suggestion promotes textual possibilities formed out of a multiplicity of connections to the situational and local milieu (see also Knight, Reference Knight2013, 260).

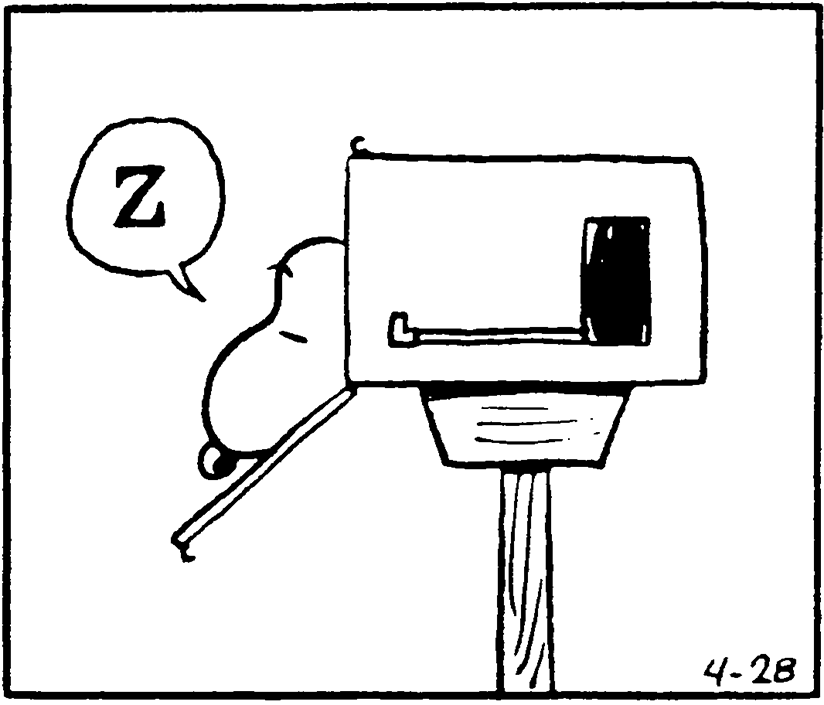

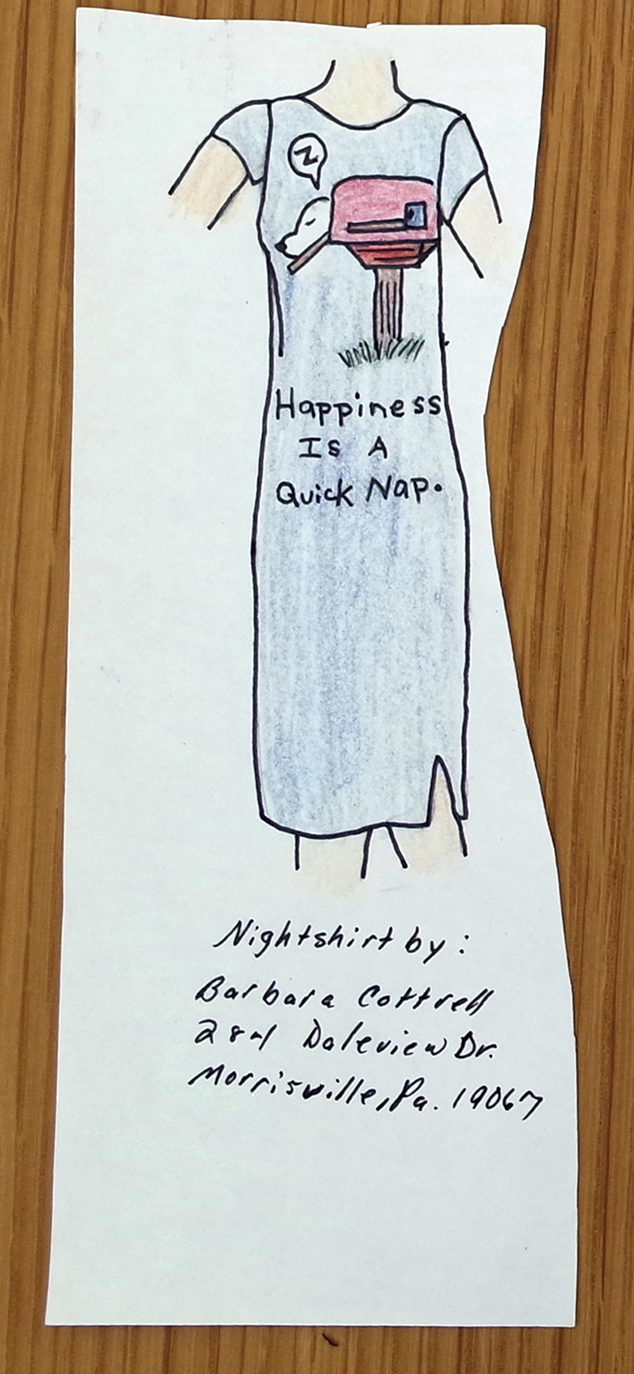

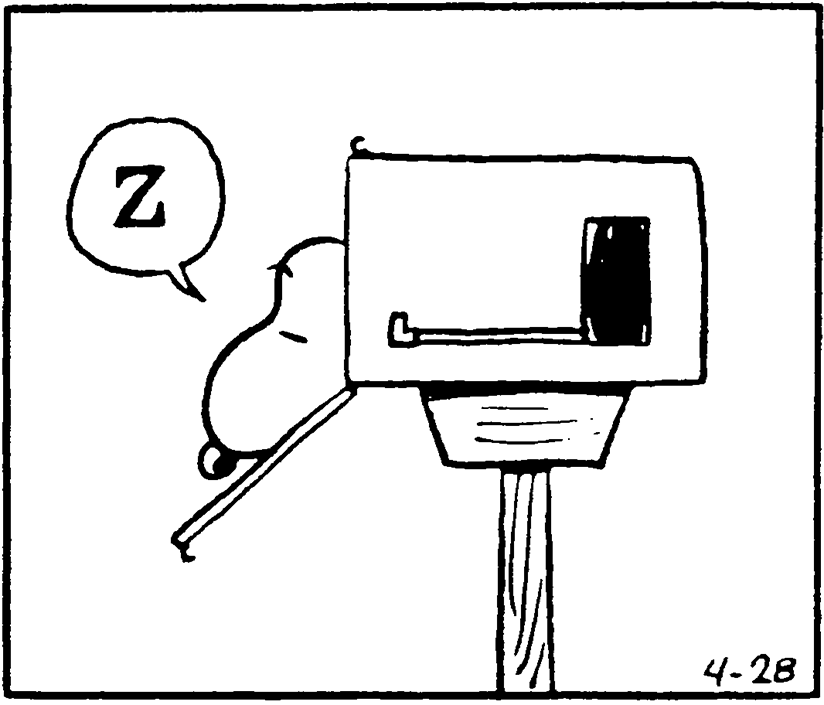

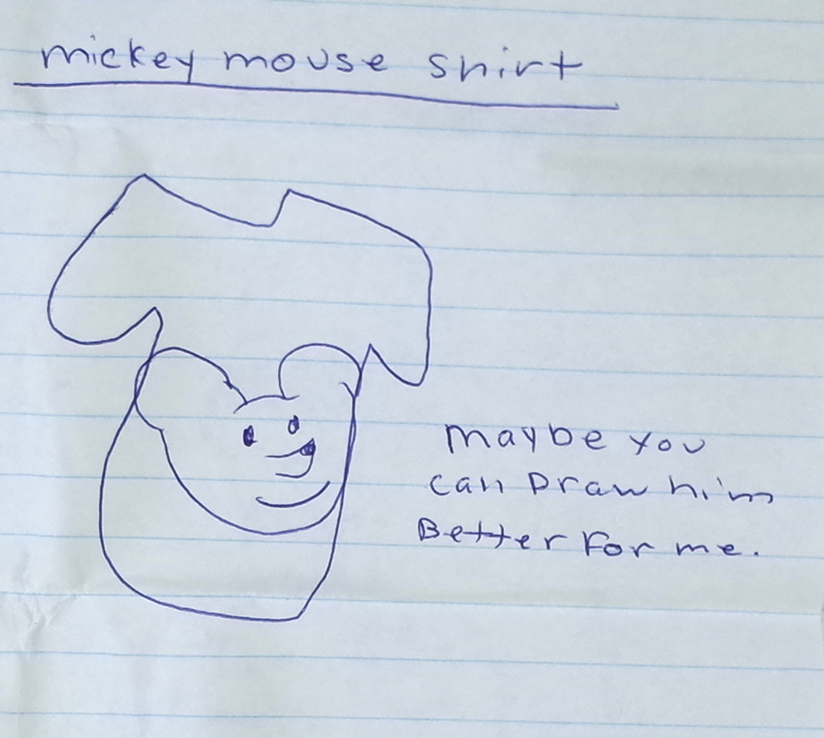

These various social, material, and environmental connections are sometimes readily apparent in readers’ drawings. For example, a design for a nightgown by Barbara Cottrell takes direct inspiration from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts. The design reworks a panel from an April 28, 1972 Peanuts comic strip, featuring Schulz’s Snoopy sleeping in a mailbox. Cottrell’s illustration is positioned above the phrase ‘Happiness is a quick nap’ (Figure 3; Cottrell, Reference Cottrell1985), which is not present in the source comic strip (Figure 4; Schulz, 1972). Similarly, Jenny Welka proposes a shirt design featuring the iconic Mickey Mouse (Figure 5; Welka, Reference Welka1986) and invites Robbins to render the character more faithfully. More personally, Patricia Buczek, from Buffalo, New York, includes a design consisting of a yellow and green striped suit and a pennant reading ‘St. Paul’s Tigers’ (Figure 6; Buczek, Reference Buczek1986). Buczek’s design is likely inspired by a certain local youth baseball team, which sports a similar colour scheme.Footnote 4 While we cannot know precisely the conscious or subconscious intentions and motivations behind these ‘contingent connections with the conditions surrounding their creation’ (Knight, Reference Knight2013, 255), these designs surely represent a mapping of the assemblage of these readers’ environments. They are ‘experimentation[s] in contact with the real’ (Deleuze and Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, 12) by which readers advocate for textual potentialities.

Figure 3. An outfit design submitted by Barbara Cottrell of Morrisville, PA.

Figure 4. The first panel from Charles Schulz’s Peanuts strip from April 28, Schulz, Reference Schulz1975, from which Cottrell’s design in Figure 3 above drew inspiration.

Figure 5. A design submitted by Jenny Welka of Oak Park, IL, featuring Mickey Mouse.

Figure 6. An outfit design submitted by Patricia Buczek of Buffalo, NY.

Although she was highly receptive to her readers’ ideas, Trina Robbins could not have included every submission, even if she had wanted to, within the limited confines of a six-issue series. We might wonder, then, how she negotiated this assemblage of contributions in shaping the final published text. Fortunately, Robbins left traces of her editorial process in the form of handwritten notes on envelopes and letters. These marginalia – such as ‘LOC’ (Letter of Comment), ‘advice’, ‘usable’, ‘primo’, ‘cute!!!’, or ‘good design’ – reveal a working editorial vocabulary used to assess the nature, utility, and appeal of each submission. While such notes offer insight into Robbins’ curatorial decision-making, they were not determinative: some marked submissions were not included in Misty, and some unmarked ones were. Robbins’ comments illustrate an extension of the ‘virtual structure’ of the text, providing insight into her interactions with and responses to this assemblage of local knowledge creation.Footnote 5

Beyond this curatorial layer, Robbins’ interactions with her readers extended into more public and participatory forms throughout the production of Misty – and later California Girls. Selected letters were published in the ‘Dear Misty’ column, where Robbins responded directly to readers’ questions and reflections. Contributors whose designs were featured in the comic received a ‘Misty Designers Club’ membership card, reinforcing their status as active participants in the creative process. These editorial, paratextual, and material exchanges together constitute a dialogic relationship between creator and audience. Svirsky (Reference Svirsky2010, 163) calls this ‘collective enunciation’, meaning a shared act of expression in which meaning is produced together rather than by a single voice. In this case, Robbins serves not merely as a gatekeeper but as a co-contributor in a distributed production of local knowledge and meaning.

A specific dialogic exchange can be seen in a group of letters referencing Hawaiian themes. Hawaiian reader Stacy Miyake submitted fashion designs and a letter of comment. She writes:

It’s a great idea to let the readers illustrate different parts of the comic… In your first issues it says you want story ideas. I have an idea below. What if Misty and the gang go to Hawaii to film a show… Mr. Collins can’t go so Misty makes a very hard decision. You can decide what it’ll be. (Miyake, Reference Miyake1985)

Apparently intrigued by this idea, Trina noted, ‘Hawaii travel idea’, on the back of Stacy’s submission. Victoria Leigh Dias, also from Hawaii, suggests similarly, ‘Maby [sic] you can even go to hawaii and become a hula dancer’. Robbins made another note, ‘Hawaii’, on Dias’s envelope (Dias, Reference Dias1986).

These narrative suggestions were complemented by other visual design suggestions. Robbins wrote notes about Hawaii on two other reader-contributed fashion designs. One design, by Hawaiian reader Carroll Kainui, included a floral headpiece, necklace, and dress, on whose envelope Robbins noted, ‘good designs – Hawaii!’ (Figure 7; Kainui, Reference Kainui1986). Likewise, Andrea Mucci’s submission included a design consisting of a floral skirt, bandeau, bracelet, headpiece, and even a lei, on which Robbins wrote, ‘usable fashions (plus Hawaiian!)’ (Figure 8; Mucchi, Reference Mucchi1986). Miyake, Dias, Kainui, and Mucci all engaged in local and situational knowledge-creation, combining their interest in Misty with their experiences of their own local, cultural, and sartorial practices. In conveying these experiences to Trina Robbins, readers promote a textual potentiality in which Misty herself embraces their local culture(s). Robbins’ annotations conceptually link each letter, ‘agglomerating very diverse acts, not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and cognitive’ (Deleuze and Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, 7). Taken together, these letters emphasise the possibility of a Hawaiian-themed feature in Misty, which Robbins evidently noticed. Unfortunately, this idea was never realised in the pages of Misty, and so it remains a potentiality.

Figure 7. Outfits designed by Carroll Kainui and annotations from Trina Robbins.

Figure 8. Outfit designed by Andrea Mucci.

Other collective enunciations, however, did make their way into the text. Misty #6 contains a feature in which Misty gains superpowers upon purchasing a new dress from the ‘Boutique Magique’. Robbins credits the story’s title, ‘Super Misty’, to reader Wren Britton, but Britton’s letter is unfortunately missing from the collection. However, two submissions contain notes from Robbins in reference to this plotline. Robbins wrote ‘use for Super Misty #6’ above Georgiana Leonard’s dress design featuring a lightning bolt decoration, and Robbins scrawled ‘Super heroine’ on the letter’s envelope (Figure 9; Leonard, Reference Leonard1986). Leonard’s design contribution was adapted for Super Misty’s costume (Figure 10; Misty #6 Robbins, Reference Robbins1986). Robbins apparently also considered Brenda Melville’s contribution of a similar lightning-themed design for the central outfit in the feature, writing ‘super heroine?’ on Melville’s envelope (Figure 11; Melville, Reference Melville1986). A pin-up page following the feature includes superhero-themed outfits adapted from other readers’ submissions (Figure 12; Misty #6 Robbins, Reference Robbins1986).

Figure 9. Outfit designed by Georgia Leonard.

Figure 10. A panel from Misty #6 (October 1986) includes Trina Robbins’ rendering of Leonard’s design from Figure 9.

Figure 11. Outfit designed by Brenda Melville.

Figure 12. Pinup page in Misty #6 (October 1986) with superhero-themed paper dolls.

Given the dominance of the superhero genre in comic-book culture during the 1980s, it is unsurprising that readers would suggest that Misty be portrayed as a superhero. Robbins’ choice to realise this idea from among the multiplicity of proposed potentialities results in a one-off parody of the superhero genre in Misty, in which the text temporarily adopts the logic and tropes of a superhero narrative. In fact, the transience of the superhero motif is made explicit: after a long day of crime-fighting, Misty washes her new superhero outfit, and the lightning-bolt design fades away along with Misty’s superpowers. Hoping to return the dress to Boutique Magique, Misty arrives at the store only to find a bakery in its place. Eerily, the shopkeeper informs Misty that the bakery has existed in that location for the last seven years. The feature concludes with Misty wondering: ‘Did I really have super-powers — or was it just my super imagination?!?’ (Robbins, Reference Robbins1986).

More than just explaining away the abrupt abandonment of the text’s fantastical superhero elements, this conclusion emphasises the nearly limitless creative potential enabled by the incorporation of reader-contributed ideas. In describing her motivation for creating Misty, Robbins had stated, ‘I was really so sick of editors saying, “Girls don’t read comics,” because I know that when you give girls comics they like to read, girls read comics. But they’re not interested in a bunch of muscular guys punching each other out’ ( Trina Robbins, personal communication, cited in Walsh Reference Walsh2022, 160). By incorporating the reader-suggested superhero genre and its tropes only to have the stereotypical superpowers fade away, Robbins subtly undermines the genre’s culture and associations, replacing them with the ‘superpower’ of the imaginations of both Misty and her readers.

Indeed, Svirsky explains that ‘imagination’ is a central function of activism, as it enables us to envision alternative ideas following from the investigation of dominant systems: it ‘not only leads to the conceptualisation of the passage into common notions [in this case, the superhero archetype], but also means that we might have a multiplicity of several and different affection-ideas…’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 176). Such a moment reminds us of this multiplicity of narrative possibilities within Misty, its resistance against establishing a stagnant textual identity: ‘the first steps into seemingly new terrain, posited on the old terrain, fighting against this old terrain and using it at the same time to transform it into something different’ (Raunig, Reference Raunig2007, 41–42). It is sadly ironic, however, that this would be Misty’s last full-length feature.

Readers also used Misty’s participatory apparatus to advocate for change beyond the text. Many letters indicate a desire that the comic reflect practices found in comic book culture more broadly, such as extended continuity, official fan clubs, or alternative distribution practices. This activism differs from that described above in that it is aimed not at participating in Misty’s system of ongoing collaborative creation but at preserving that system in the face of less supportive external structures (ie, the publisher and distributors). This view aligns closely with Jeffery’s conceptualisation of a ‘rhizome of comic book culture’ composed of stratified corporate, creator, and reader domains, whose activities and priorities are divergent but also interconnected and interdependent (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, 48). Both Robbins and her readers recognised that their creative interests in the comic are not always aligned with those of corporate structures, and so they used the participatory apparatus to voice their concerns.

In this way, this form of reader activism involves ‘the encounter of forces, bodies and things… [through which] activism collides with the stable structure, producing a sort of dialectical relation’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 170). In other words, readers’ advocacy for extra-textual change can be seen as negotiations among reader, creator, and corporate assemblages. The reader and creator want to preserve and make accessible the creative project of Misty, but the corporation is primarily interested in generating sufficient profit. Fundamentally, this relationship is predicated upon an unequal power dynamic: the creative activity of Robbins and her readers is dependent on the support of the corporate structure. Thus, this form of activism generally promotes a more cooperative relationship in which corporate systems generate profit while readers engage with Misty’s creative project.

This dialectical activism is most evident in letters advocating for Misty’s continued publication beyond its initial six-issue run. Twenty-seven-year-old Jeffery C. Branch, one of at least 64 readers who expressed interest in the series’ continuation, outlines a potential path forward for Misty:

…I think the book should be a regular part of Marvel’s Star line-up. Perhaps if enough kids write in to you or the editors, the series will continue. You’ve definitely got my vote to demand more of Misty, especially so I can try my hand again at designing more outfits. It’s a lot of fun, even for an amateur [sic] like me. (Jeffery C. Branch, Reference Branch1986)

Branch posits that readers should lobby the corporation in a manner similar to the process of political activism, in which constituents contact their government representatives. He believes that Misty’s continuity depended on reader advocacy, but he also recognises that the comic’s future ultimately rested with the publisher, highlighting the stark power differential between these domains. Svirsky suggests that such a democratic framework ‘limits and contains nomadic forms of resistance… creating distinctions between moral worlds… [and doing] nothing to further the exploration and intensification of present activist potentialities’ (2010, 166–167). Indeed, readers must balance advocating for their interests with accepting the corporation’s ultimate control. Marvel’s decision to conclude Misty after its planned six-issue run is perhaps evidence of the limitations of the dialectic activism practiced by Misty’s readers.

Furthermore, Robbins identifies distribution and the whims of comics shops and their perceived clientele as forces restricting access to Misty:

You know what killed all these attempts in the 80s to do girls’ comics was distribution. Because at this point, the only place that you could get a comic was comic book stores, and they did not want to carry girls’ comics, so Misty was not renewed after the six issues because it wasn’t selling, and it wasn’t selling because it wasn’t being distributed (Trina Robbins, personal communication; cited in Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 166).

According to Robbins, comic book stores excluded teen humour fashion comics like Misty because they were not marketed to their predominantly male clientele. Even though Misty was published by a mainstream publisher, it apparently was not, in Robbins’ view, fully embraced in social and retail comics spaces. Robbins’ comments here colour her later claim that ‘the majority of women who do read comics tend to gravitate to [indie comics]’ (Robbins, Reference Robbins2002, np).Footnote 6 Without access to the physical comic, readers also lost access to its participatory culture. Indeed, at least three readers either expressed difficulty in finding the comic in stores or asked about a subscription-based model of distribution (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 166–167). These readers used this open line of communication to advocate for their access to the text.

Finally, readers advocated for a social apparatus akin to the publisher-run fan clubs that emerged during the Golden Age of comics (see Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, 48), such as the Archie Club from M.L.J. Magazines/Archie comics or the Captain Marvel Club from Fawcett. Although readers whose material was included in Misty received a card certifying their membership in the ‘Misty Designer’s Club,’ there was no official Marvel-sponsored club that readers could join. At least six readers inquired about an official Misty fan club. For instance, a postscript on 7-year-old Angela Russell’s letter, likely written by a parent, asks: ‘Can you send information on a fan club? There are several little girls in the neighborhood who love the comic. Thanks!’ (Russell, Reference Russell1986). Readers (and their parents) were cognizant of the local social networks that formed around Misty and lobbied for publisher-supported infrastructure for those networks. Robbins seemed enthusiastic about the idea, writing on Russell’s envelope, ‘LOC wants fan club!’ The extent to which she herself communicated with Marvel about a publisher-sponsored organisation is unknown, but the archival collection certainly indicates a joint desire by both reader and creator to include Misty among the Marvel titles with officially sponsored social groups.Footnote 7

In the absence of an officially sanctioned fan organisation, however, some readers took it upon themselves to create their own fan clubs to support their local social networks. Nine-year-old Nausheen Hassan, for example, writes about starting a Misty fan club – complete with dress code and membership cards – with her friend. Through the establishment of an unofficial fan club, Hassan ‘bypasses existent stable practices’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 171) to construct a new, alternative institution based on local and situational exploration. However, Hassan’s work does not constitute a total rejection of the corporate dialectic. In the interest of attracting more members to her club, she requests that Misty extend its publication beyond six issues: ‘Like millions, we don’t want a limited series, we want one that goes on & on, like, for instance, Archie comics’ (Nausheen Hassan, July 21, Reference Hassan1986).

The aggregate of readers’ submissions constitutes ‘an assemblage of encounters pushing the system [ie Misty’s text and/or Marvel’s corporate-assemblage] towards new states’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 168). Misty’s participatory structure encouraged and embraced the promotion of reader-created potentialities based on local and situational knowledge creation, fostering an ever-evolving textual environment fuelled by activism. However, because of the comic’s inescapable connection to the profit-driven corporate assemblage, readers’ extratextual activisms generally involved a dialectical mode of critical engagement that sought to preserve Misty’s participatory apparatus and make it more accessible.

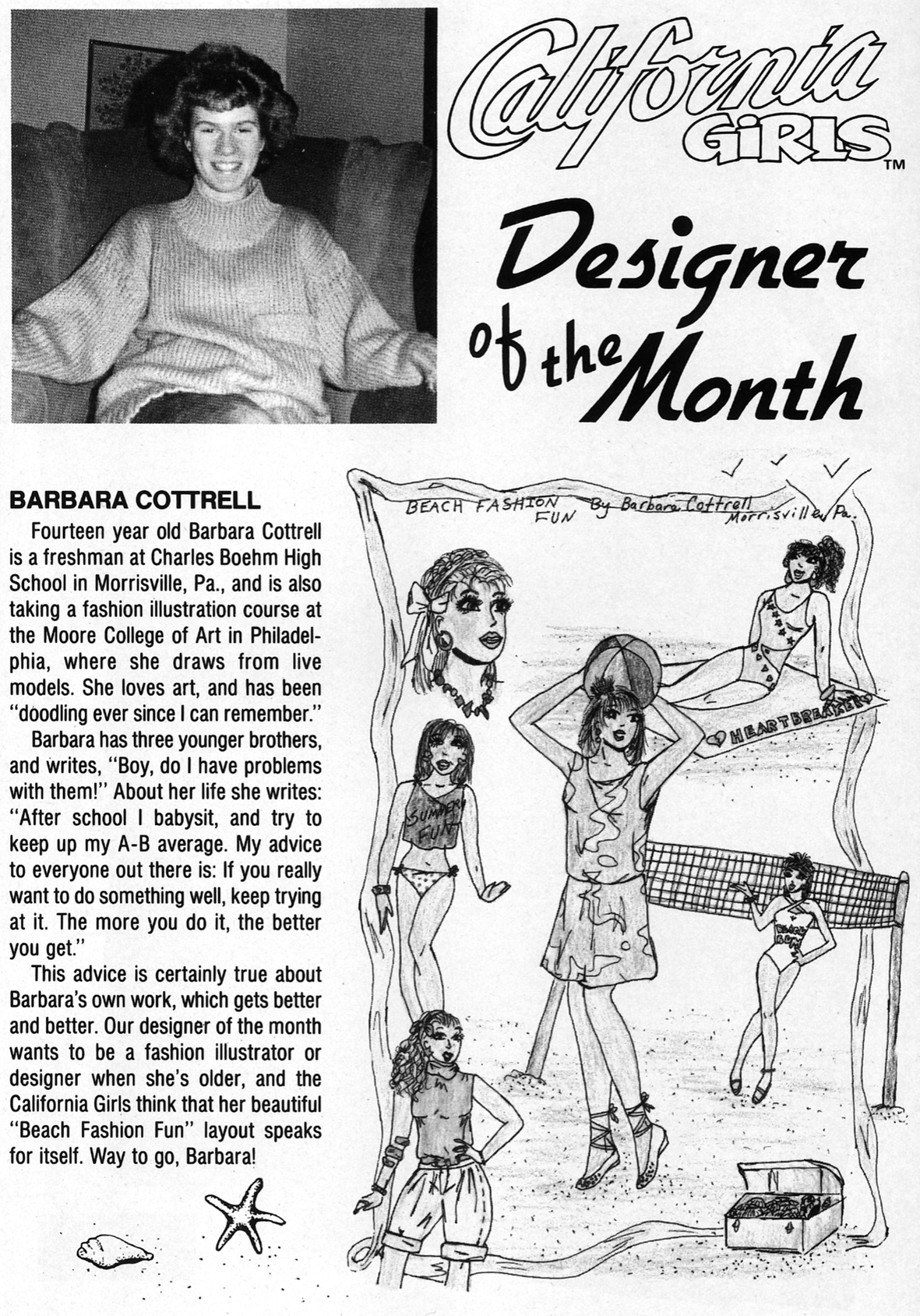

Ultimately, this activism was not successful in sustaining Misty. However, Robbins’ next project, California Girls, published by the independent publisher Eclipse Comics, included a participatory structure similar to Misty. It was an opportunity to experiment – to create the participatory culture anew. Many contributors to Misty – including Jeffery C. Branch, Barbara Cottrell, and Wren Britton (all mentioned above) – were attracted by this new opportunity to participate in comics creation and also submitted to California Girls.

Misty’s impact on readers

Readers engaged in activist practices to contribute to and affect the narrative direction of Misty and to advocate for the preservation of their creative enterprise. Likewise, Misty’s participatory culture itself affected its readers in turn. Jeffery points out that engaging with comic book culture can influence how readers construct their own identities both abstractly and materially – for example, through abstract self-identification as a ‘geek’ or through physical body alterations like tattoos (Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b, 214–217). Indeed, Misty’s rich participatory apparatus invites us to consider how involvement in this fundamentally activist endeavour could affect the construction of readers’ own identities. In this section, we explore how the creative project of Misty enabled the personal empowerment of its participants in both the short and long term.

Perhaps most immediately, engagement with participatory culture provided Misty’s readers – most of whom were children – with an outlet to engage with the world around them. On studying child development through children’s drawings, Linda Knight suggests that ‘what is relevant is how the child connected to the milieu, to the ‘assemblage,’ the multitude of objects, sensations, emotions, people, creatures that surrounded him as he drew’ (Knight, Reference Knight2013, 260; de Freitas, Reference de Freitas2012). Hannah Sackett embraces Knight’s idea in her study of children’s comic-book making, suggesting that ‘as with comic-making, children’s drawing activities are caught up with other people and places, they are performative and discursive, material and embodied, and they happen in the world and in time’ (Sackett, Reference Sackett2021, 44). In this way, children’s drawings help us understand ‘how learning takes place voluntarily and instinctively, with the possibility of embracing connections and complexity and open-ended learning’ (ibid, 53). As illustrated above, connections to the local milieu are apparent in many of the designs and drawings submitted to Misty, and analysis of these connections is crucial for understanding how readers critically engaged the text.

Moreover, readers could receive answers to requests for advice either in the published letter column or through direct correspondence from Robbins herself, suggesting that Robbins had a ‘marked interest in building connections between the comic-assemblage and the reader’s reality’ (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, 46). Indeed, the material and social realities of readers who considered or implemented Robbins’ advice may have been meaningfully shaped by their participation in the comic-creation process. Furthermore, the experience of seeing one’s conceptual, textual, or graphic contribution implemented in Misty could result in a range of affective responses such as validation, understanding, and acceptance. The ‘Misty Designer’s Club’ card materialised these intellectual, aesthetic, and emotive interactions: by inducting readers into an ‘official’ network of fellow Misty reader-creators, the card served as a physical reminder of readers’ impact on the creation of the text.

However, engaging in participatory culture can have more significant long-term effects. Indeed, we ‘are not only interested in how or why children draw, and how their works of art emerge through the process of making; [we] are also interested in the process of change that takes place in the children themselves’ (Sackett, Reference Sackett2021, 45). Misty’s readers, like the very text they helped create, are constantly changing and adapting, perpetually engaged in a continual process of ‘becoming’, a philosophical term for the idea that identities are always in process, never fixed. While reading comics habitually can aid in the construction of coded identities such as ‘geek’ or ‘fan’ (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b, 214–215), participatory culture prompted many of Misty’s young readers not just to construct who they are but to wonder who they might become. At least 17 readers indicated an interest in fashion design or comics authorship as a vocation in their letters (Walsh, Reference Walsh2022, 167). Just as Misty’s participatory culture enabled readers to advocate for the inclusion of their own textual ideas, it also encouraged readers to investigate their own potential futures in conversation with their present participation in collectivised comics creation.

It has been well-documented that many comics readers eventually become professional comics creators themselves (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, 50; Coogan, Reference Coogan2006, 218; Gordon, Reference Gordon2012), and Misty’s readership is no exception. Reader Bill Walko, for example, who was featured three times in Misty #6, is now a professional illustrator and comics author, creator of the long-running and critically acclaimed series, The Hero Business. Eric Shanower, known for his reimagining of the Trojan War in his Age of Bronze comics series, would have been a young man in his early twenties when he contributed designs to Misty. Others among Misty’s readership pursued creative professions similarly aligned with the comic’s scope and subject matter, such as fashion and visual art.

We now turn to more recent communications, conducted by email, telephone, and video conference, with three such readers. We contacted several former readers of Misty, many of whom have cultivated successful careers in diverse and often creative fields, including academia, photography and film, and pole dancing. Here, however, we highlight the recollections of Noémi Farkas, Shane Ballard, and Barbara Cottrell Trippeer because their professional work aligns most closely with the activity and subject matter of Misty’s participatory culture. These communications provided a venue for these former readers to remember their childhood engagement with Misty and to reflect on how this activity – even though they may have forgotten it before we contacted them – has shaped their lives and personal philosophies. In connecting these personal memories to the archival memory of reader’s contributions to Misty, we illustrate ‘how the mediated memory of earlier activism informs later activists and movements by feeding back into actions, mobilisations and expectations, though not necessarily in a linear way’ (Merrill and Rigney, Reference Merrill and Rigney2024, 999). In these rekindled memories, we found that engagement with Misty engendered a sense of self-empowerment, encouraging these readers to continue cultivating their creative interests long into adulthood.

Noémi Farkas, who sent two letters to Robbins and whose fashion design was featured on the cover of Misty #5 (Figure 13), has found success in the visual arts. Her most recent project, EGO, is the result of a process of deep self-reflection about her experience as a Romani woman and the ‘internal and external battles that take place between one’s own ego and the egos of others, even subconsciously’ (Farkas, 2024, EGO, NoémiFarkas.com). Her work was featured in a February 2024 exhibit at the Szentandrássy István Roma Art Gallery in Budapest. Drawing and art were fascinations for Farkas from an early age: ‘art sort of just came to me—I never really thought, “oh, I want to do art”… I’d just do it’ (Farkas, 2024, personal communication). Farkas drew constantly, recalling that her mother routinely brought home pencils and deposit slips from the bank that Farkas would use for drawing. The attention that her more recent work has attracted, she says, ‘makes me want to share what I’ve experienced so that I can help other people connect… It’s just wanting to connect…’ (ibid).

Figure 13. Outfit designed by Noémi Farkas for Darlene (standing figure) on the cover of Misty #5 (August 1986).

As for Farkas’s interest in Misty, she was attracted to the comic book both for its participatory elements and for its focus on women: ‘[Misty] had a girl power thing to it, and I was always drawn to girl-power things and empowering myself because I’ve always been so… well, lacking self-confidence. And I’m sure many little girls were like that’ (ibid). While she was not an avid ‘comic-head’, she enjoyed reading comics with female protagonists, including Misty and the British title, Tank Girl: ‘it empowered me when I saw other females empower themselves… it inspired me’ (ibid). Seeing powerful women represented in comics gave Farkas confidence that she could achieve her own ambitions.

Although Farkas recalled a close friend who shared her love of reading and art, Farkas described her engagement with Misty as a solitary activity. Even so, it was the collective aspect of Misty’s participatory culture that ultimately compelled her to contribute: ‘when I saw other girls doing it, I was like, “oh it’s so cool you got your design in Misty?”… I just felt like it was fun! I wanted to do it—I wanted to do it too’ (ibid). Even though her participation was locally individualised, her motivations were decidedly social. Indeed, as Woo notes, ‘while “activity” may be entirely individualised, practices are inescapably collective. Even when pursued alone, they depend on a dense, multiply articulated assemblage of know-how, beliefs, and material resources; they are social through and through’ (Woo, Reference Woo2012, 183). Farkas felt inspired by seeing the work of other fans, and she, too, wanted to engage with that collective effort, hoping to see her own work in the pages of Misty.

And indeed she did. Farkas recalls her excitement at seeing her work recreated in the comic and connects those feelings to her current motivation for creating art:

I remember… my heart was racing when I saw my artwork—my design… It was just such a feeling of not just magic—like I can’t believe this happened [and my submission] actually materialised and is being duplicated or replicated many times—that was so cool. I felt famous for a second, or something like that. But it definitely gives you such a boost in your self-confidence and self-worth. And that’s… again why I want to share my process of doing art with people so that maybe they could be open to freely expressing themselves, whether it be through visual art or dancing, because it’s a wonderful channel. And you create something that satisfies you, and makes you feel proud. You’re like, ‘oh damn I just did that, that’s so cool! (Farkas, personal communication)

The feeling of being ‘heard’ and understood by Robbins, seeing her submission realised in the text was invigorating to Farkas, and she has similar feelings regarding her current work:

I was like, ‘I can’t believe they actually heard me.’ And that’s sort of how I feel right now with this exhibit [EGO], that people actually sensed what I was trying to get across. And I’ve gotten so much feedback about how they really appreciated it and how it’s changing their perspective. (ibid)

The sense of pride, understanding, and impact that she felt upon seeing her work in Misty is found also in her reactions to seeing her current work in a public space. Both in childhood and today as an adult, Farkas feels empowered by creative endeavours and their capacity to connect with and affect others.

Shane Ballard, a reader whose fashion design was published in Misty #6 (Ballard, Reference Ballardn.d.; see Figures 14 and 15), later entered careers relevant to his interests in both comics and fashion. Ballard was an avid comics fan throughout his childhood – a ‘comic-book kid’ (Ballard 2024, personal communication). He also had a keen interest in illustration from the age of 2 years: his skill as an artist was highly developed even from an early age, and he particularly enjoyed drawing fantasy and science fiction subjects. As a teenager, fashion design became his primary artistic interest.

Figure 14. Outfit designed by Shane Ballard.

Figure 15. Panel in Misty #6 (October 1986) featuring Ballard’s design in Figure 14.

Ballard read mainstream Marvel and DC comics, but at around 11 years old, he became interested in titles like Misty, Katy Keene, and Betty and Veronica for their fashion-centred participatory elements: ‘I remember those three books all being a huge lightbulb moment for me. It was like two of the things that I loved the most merged together. And so, it was just a no-brainer for me to submit’ (ibid). His combined interests in comic books and fashion led Ballard to engage in participatory culture. His participation was foundational in that it demonstrated to him the potential impact of his ideas and work: ‘It was the perfect opportunity to see what I envisioned in my head from a fashion perspective on an actual character, and then to have it published. I think it was the first opportunity that I ever had to see something that I designed on a [published] page’ (ibid). Like Farkas, seeing Ballard’s own work in a widely distributed magazine was inspiring to him.

Ballard’s engagement in participatory culture was also a solitary endeavour. He had one friend who also read comics, but he recalls:

That wasn’t something I would have shared with him because I was a twelve-year-old boy who’s drawing fashion comics, which isn’t the coolest thing in the world… and I’m an only child, so a lot of my time was spent by myself drawing. It was a very solitary kind of hobby of mine. (ibid)

While we have shown that participation in Misty did help create local social networks, Ballard’s comments are evidence that teen humour fashion comics and their readership could be unwelcome in male-dominated comics spaces. He was even surprised to learn that a publication with such grassroots elements was an official Marvel publication: ‘I assumed that it was an indie comic book’ (ibid). Even as a male in the comics space, Ballard felt it would not have been ‘socially acceptable’ to share his engagement with these teen humour fashion comics with his larger friend group because of both gender expectations and wider social stigma surrounding comic book readership at the time.

After graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT), Ballard utilised his knack for conceptual design to launch a career in the corporate fashion industry. However, Ballard eventually left the corporate world after realising it was less creative and more profit-driven than he had anticipated – a situation reminiscent of the divergence between the corporate priorities of Marvel Comics and the creative visions of Trina Robbins and her readers. Spurred by his continued appreciation for comics, Ballard pursued positions at Marvel in concept art, packaging, and toy design, but his career would only evolve further after he began designing costumes for his theatre director friend. Ballard’s work was noticed by well-known costume designer Paul Tazewell, who subsequently hired Ballard as an illustrator for the television show The Wiz Live in 2015. Since then, Ballard has worked as a costume designer and illustrator for television and film, as well as an educator at Rutgers University and FIT.

Ballard realised during our conversation that engagement with Misty had a long-term impact on his life. In remembering his contributions to Misty, he traced the philosophy that he applies to his current work to his childhood engagement with participatory culture:

I’ve always had a love for stories and storytelling, and the marriage between character and clothing, and how clothing can really inform how you experience a character… when I was ten or eleven it wasn’t that sophisticated an ideology, but now that I see the thread—how these things have been sort of continuous… I can see how something like Misty really did inform a lot of how my career trajectory took place (ibid).

In fact, Ballard had forgotten about his engagement in comics participatory culture until receiving our initial message. He suggested that this might have been because his participation had ‘folded into’ his understanding of himself as an ‘artistic over-achiever kid’ (Ballard, 2024, personal communication). Reader participation in comics was just one of many artistic endeavours Ballard pursued as a child, and this multiplicity facilitated the construction of his identity as an artist. He forgot the particular activity of submitting designs to comics, but retained the larger persona which this activity helped to shape. Remembering Misty and his engagement with it prompted Ballard to deconstruct that persona and to reflect on how that particular activity affected him over time: ‘It’s incredibly validating to see what I was doing creatively at eleven or twelve and to see that it’s been a journey for me that started so long ago. I’ve definitely found my niche’ (Ballard, personal communication).

For Farkas, the recollection of her experience with Misty similarly illuminated aspects of her life’s trajectory, of which she had not been consciously aware. Farkas realised that being ‘heard’ by the creators of Misty may have been a ‘spark’ that contributed to her philosophy on artistic creation throughout her life. Moreover, it encouraged her to ‘keep faith’ in doing art. She recalled, ‘even if I forget why, just keep doing it… [Misty] assured me that I could be heard… Right now that’s not what I recall when I put myself out there with this EGO exhibit and body of work, but definitely what I desired was to be heard and to make change…’ (Farkas, 2024, personal communication). For both Farkas and Ballard, the distant childhood activity of contributing to a larger, communal creative project had a lasting impact on their long-term artistic motivations, attitudes, and philosophies, as well as on their career and life choices.

Finally, Barbara Cottrell (now Barbara Cottrell Trippeer), whose fashion designs were featured in Misty #5 and #6, also went on to pursue fashion as a vocation. Trippeer was an avid comic book reader and illustrator throughout her youth. Drawing paper dolls, she recounts, ‘was [her] entry point to fashion’ (Trippeer, 2024, personal communication). She, like Farkas, was attracted to Misty because it was ‘one of the few [comics] marketed toward a female audience’ (ibid). Trippeer was also attracted to the title’s participatory elements: even after Misty’s conclusion, she sought opportunities to engage in comic book participatory culture, routinely submitting designs for Trina Robbins’ next project, Eclipse Comics’ California Girls. In California Girls #2, Trippeer was featured as ‘Designer of the Month’ (Figure 16; Robbins, Reference Robbins1987). It was these comics’ participatory elements, then, that prompted her to cultivate further her creative interests. Trippeer recalls, ‘my “success” in having my work selected informed my passion to continue [pursuing fashion] — even though I was not trained in home economics’ (ibid). Engaging with comic book participatory culture gave her personal license to pursue her interests in fashion design and illustration.

Figure 16. Page in California Girls #2 (July 1987) highlighting Barbara Cottrell as ‘Designer of the Month’.

In high school, determined to pursue fashion illustration as a career, Trippeer took pre-college courses in fashion design at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. While pursuing a bachelor’s degree at Parsons School of Design, Trippeer expanded her focus of study ‘beyond simply being an illustrator and learn[ed] how to master garment construction’ (ibid). Following her studies, she launched her career in New York. Trippeer worked her way up the corporate fashion ladder, eventually designing for brands such as Liz Claiborne and Target. Like Ballard, she left the corporate design world due to her growing concerns about the industry’s ‘exploitative design practices’ (ibid). Aiming to make a positive impact on the fashion industry, Trippeer reoriented her career towards fashion education: ‘Determined that we could do better, I had a desire to take what I had learned about the industry and apply it toward becoming a fashion educator’ (ibid). She received her M.F.A. in Design Research in 2015 from the University of North Texas, and in 2017 she began teaching at FIT in New York. In 2019, she returned to the University of North Texas to teach fashion design, where she emphasises to her students the importance of drawing as a method for iterative design and concept generation.

This exploration of reader experiences highlights the important role that recollective memory can play in research about participatory culture in comics, offering a more comprehensive look into the reciprocal relationship between comic and reader. In this case, remembering Misty’s participatory culture prompted Farkas, Ballard, and Trippeer to trace the long-term effects of their engagement with Misty on their lives and careers.Footnote 8 Misty allowed these readers to see their own work directly shape the collectivised text of a professionally produced and widely distributed comic book magazine.

This was a personally empowering experience for all these readers. It not only motivated them to pursue their lifelong creative interests but also informed the personal philosophies that have guided their careers and life choices. Granted, these readers are only three of the hundreds who participated in Misty’s creation, and certainly, many readers who submitted did not pursue creative vocations. However, highlighting the memories of these successful contributors illustrates the potential of Misty’s participatory culture to encourage and foster creativity and to have long-lasting effects on readers’ lives.

Conclusion

This study contributes to comics studies by corroborating and expanding upon prior literature on participatory culture and comics, suggesting that comic book culture is not predicated on binary divisions between domains but involves an expansive network of interrelated and interdependent entities (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016a, Reference Jeffery and Jeffery2016b). Misty is particularly complex in this regard, as there was significant overlap in the roles of creators and readers, with readers contributing to multiple aspects of the comic’s production.

Utilising the archival collection of fan mail and reframing participatory culture in terms of activism, this study advances a deeper understanding of reader engagement in twentieth-century teen humour comics. In contributing content for inclusion in Misty, readers repurposed the text by drawing from myriad domains, including their local environments and cultures, other media, and abstract ideas like feminism and beauty. Robbins negotiated this assemblage of reader-contributed content in part by identifying trends within the reader-submitted material, thereby connecting several independently created submissions into a unified textual idea. In line with Svirsky’s conceptualisation of activism, this collaborative dynamic between reader and author results in a continual process of textual creation, by which the text actively resists stagnation.

Moreover, readers used this open channel of communication to lobby the publishing corporation to preserve and expand the creative project of Misty. Confronting the profit-motivated commercial enterprise of comics production, readers advocated for extra-textual changes such as extended continuity and the creation of officially sponsored fan clubs. This dialectical activism – a push-and-pull exchange where fans press for change but negotiate within corporate limits – failed to achieve the desired result, but Misty’s demise provided the incentive for both creator and reader to pursue their creative endeavours through alternative outlets. They migrated and rebuilt the participatory culture of Misty in a new publication, California Girls, under a smaller, independent publisher.

Reciprocally, participation in this activist process had meaningful effects on many of Misty’s readers. Evidence from the published and archival fan mail suggests that participation in Misty’s creation prompted immediate feelings of validation and acceptance in its readers. Further, the recollections of Farkas, Ballard, and Cottrell Trippeer also demonstrate the profound effect Misty could have in shaping readers’ careers and personal philosophies long into adulthood. Even though Farkas and Ballard had forgotten about their participation, rekindled memories of Misty enabled them to deconstruct their current identities and reflect on the manifold ways in which the comic had affected who they had become.

This study explores the activist impulse of twentieth-century comics through various sites of memory, including archived correspondence and personal recollections. By practically applying Svirsky’s conceptualisation of activism onto Misty’s participatory apparatus, we have shown that activism is indeed ‘an open-ended process’ (Svirsky, Reference Svirsky2010, 163) and cannot be understood simply as ‘supporting or leading social struggles’ (ibid). Moreover, in situating the archival memory of Misty in conversation with the recent recollections of its reader-participants, we have advanced scholarly understanding of the complex ways in which activism and memory interact (see, eg, Rigney, Reference Rigney2018, Rigney, Reference Rigney, Berger, Scalmer and Wicke2021, and Merrill and Rigney, Reference Merrill and Rigney2024). In doing so, we have laid the groundwork for further study of other participatory comics and comics titles that discuss social issues and causes more explicitly. We are not aware of similar archives of unpublished material recording the genetic history of a comic like Misty. However, published fan mail, widely available in comics collections in libraries and digital archives, merits further study for traces of readerly activism and engagement not just with comics production but also with issues that have motivated broader activist movements (eg, civil rights, military conflict, the environment, and LGBTQ awareness).Footnote 9

Conventional fan mail columns are a distinct form of reader participation when contrasted with the narrative and design contributions we find in Misty and other teen humour fashion comics. Nonetheless, readers contributing fan mail offer their thoughts and ideas, critiques on art and design, and suggestions for future narrative directions. More recently, reader interactions with comics, comics creators, and publishers have transitioned to online platforms and social media, and these digital interactions are yet another rich data source that may provide further insights into readerly activism and memory. We hope other researchers will join us in mining these rich sources of information – archival collections, published fan mail, and digital and online communications – to explore further the activist impulse in comics readership as well as the complex, impactful, and epistemically transformative interactions among comics, creators, and readers.

Data availability statement

The archival materials that support the findings of this study are available from the Trina Robbins Collection and Papers, housed at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at the Ohio State University. The finding aid for the Trina Robbins Collection and Papers is available at https://library.osu.edu/finding-aids/ead/CGA/SPEC.CGA.TR.xml.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at The Ohio State University for their assistance, Trina Robbins for discussing her work on Misty, and the Misty readers who shared their experiences.

Funding statement

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, whether in the commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Evan O. Brandon is the Accessioning Archivist at Indiana University Bloomington’s Lilly Library. His research interests include literary criticism, philology, and archival theory and practice.

John A. Walsh is an associate professor of information and library science and Director of the HathiTrust Research Center at Indiana University. His research interests include computational literary studies, textual studies and bibliography, text technologies, book history, nineteenth-century British literature, poetry and poetics, and comic books.