One of the striking features of most early (ninth-century) mosques in North Africa (the Maghrib) is their extremely modest exteriors, which stand in sharp contrast to the articulated façades of their interior courtyards. Indeed, one might argue that such early congregational mosques as those in the Tunisian cities of Kairouan, Sousse and Tunis were not meant to be seen from the exterior at all, revealing themselves only once one had entered. This feature stands, of course, in sharp contrast not only to earlier buildings in the region, many of which still stood at the time of the Muslim conquest, which placed great emphasis on the exterior and were usually meant to be seen from all sides. Although the interior focus of early Islamic architecture in the Maghrib is shared with early Islamic architecture elsewhere, its persistence in the region contrasts with architectural developments in the central and eastern lands of Islam, where façades and such exterior features as domes and towers become increasingly important.

The monuments

Muslim armies entered North Africa from Egypt in AD 641–42, a decade after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. They crossed Barqa and Tripolitania, in present-day Libya, and conquered the former Roman provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Byzacena, now in Tunisia and eastern Algeria. They called this province Ifriqīya and founded a garrison they called al-Qayrawān (Kairouan) in the middle of the Tunisian steppe. Muslim armies continued to move across North Africa, reaching the Atlantic coast in 681, but the first 150 years of Muslim rule in the region were marked by repeated local resistance, such that no structures are known to survive from this early period, and the earliest structures that do survive are all in present-day Tunisia (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 20–21).

The congregational mosque of Kairouan, known as the Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba after its purported founder ʿUqba b. Nafi’, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad, is the oldest surviving Islamic religious building in Tunisia (Creswell Reference Creswell1940 [repr. 1979], 208–26, 308–20; Marçais Reference Marçais1954, 9–22; Golvin Reference Golvin1968; Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 28–34). Founded in 670, the mosque is now located in an unusually eccentric position, a block away from the old city walls on the far north-eastern side of the medina, or old city. In most of the Islamic world, the congregational mosque normally stands in the heart of the medina, and we know from historical sources that this was once the case here as well. The present walls, which were erected after the collapse in the city's population, are much later than the mosque. The medieval historian al-Bakri reported that the main street of the Aghlabid city, al-Simāṭ, ran along the east side of the mosque and was about 4 km long, extending from the Abu'l-Rabiʿ in the south to the Tunis gate in the north, where the two Aghlabid basins still lie (EI2, s.v. ‘Ḳayrawān’). It was roofed from one end to the other and lined with shops on either side, in the words of Georges Marçais (Reference Marçais1937, 27) ‘like most of the suqs of Tunis’.

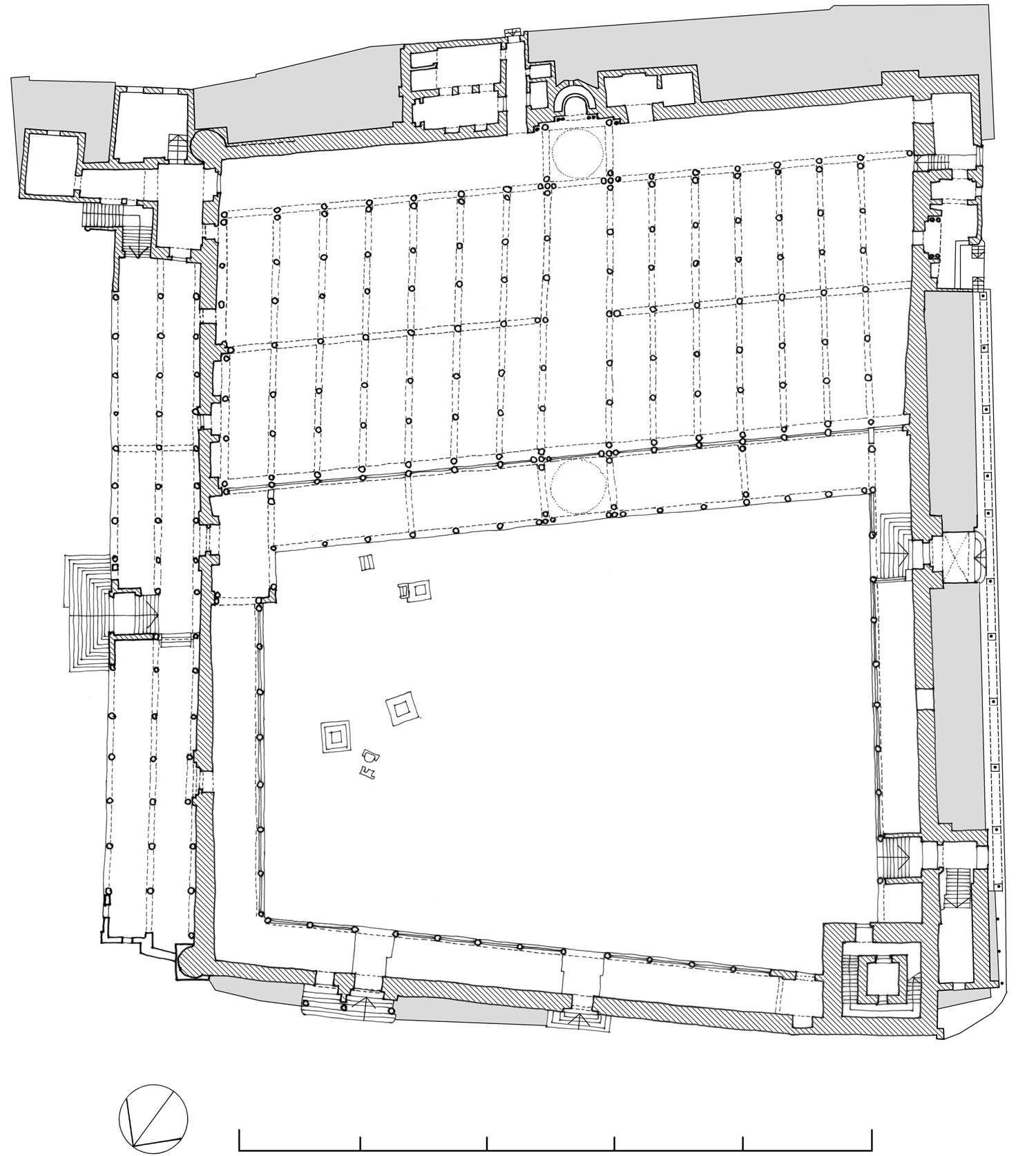

The oldest parts of the present building are no older than the ninth century, for in 836 the Aghlabid governor, Abu Muhammad Ziyadat Allah (r. 817–38), spent some 86,000 dinars (or more than twice the annual tribute sent to Baghdad) demolishing and reconstructing the old mosque. Another campaign in 862 by his successor Abu Ibrahim Ahmad (r. 856–63) repaired damage caused by earthquakes and floods in the region. The mosque (Figure 1) now consists of a roughly rectangular enclosure measuring about 70 × 120 m oriented towards the south-east. The two longer side walls are quite askew, showing the builders’ difficulty in setting out the plan. A massive three-storey tower stands in the middle of the north-west wall. The mosque's exterior brick walls (Figure 2) are punctuated with a great variety of buttresses, seemingly located at random, and several modest openings in the lateral walls lead into the interior. The three monumental projecting and domed portals opening onto the sides of the mosque are all, however, much later additions.

Figure 1. Kairouan, Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba (plan N. Warner).

Figure 2. Kairouan, Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba, exterior west wall (photo J.M. Bloom, 1978).

Apart from the upper parts of the of the dome over the mihrab (Figure 3), the minaret is the only part of the mosque that would have been visible from outside had the mosque been enclosed by other buildings. In any event, it seems that the minaret was principally meant to be seen from afar, but certainly not while praying in the mosque, when it would have been behind the worshippers (Bloom Reference Bloom2013). The interior of the mosque consists of a vast courtyard measuring about 50 × 60 m surrounded by double arcades, erected at various periods. Along the side of the courtyard in front of the prayer hall, the arcades form a sort of narthex or porch, at the centre of which stands an elegant ribbed dome known as the Qubbat Bab al-Bahw (or Bahu, meaning ‘covered gallery’ or ‘vestibule’), built by Abu Ibrahim Ahmad (Figure 4). The narthex certainly obscured the original façade of the prayer hall, which may have been decorated with an inscription running across its width (Bloom Reference Bloom and Eastmond2015). The prayer hall itself is a forest of reused antique columns, with 16 arcades forming 17 aisles ending a bay before the qibla, or Mecca-facing wall, thereby creating a transverse aisle equal in width to the wider central aisle of the prayer hall, with the crossing marked by another dome in front of the mihrab.

Figure 3. Kairouan, Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba, dome over the mihrab (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

Figure 4. Kairouan, Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba, courtyard façade (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

The congregational Mosque of Tunis, known as the Zaytūna or Olive Tree Mosque, is slightly later in date and mostly due to the patronage of the Aghlabid amir, Abu Ibrahim Ahmad, in 864–65 (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 38–41). It shares many features with the Kairouan mosque, although it is smaller and somewhat squarer in plan. The building is a very irregular quadrilateral measuring approximately 60 m (south-east = qibla) and 64.3 m (north-west) wide and 58.5 m (north-east) and 64.3 m (south-west) long (Figure 5). The courtyard is smaller than at Kairouan but is also surrounded by an arcade (here only single), with another elegant dome at the centre of the side in front of the prayer hall (Figure 6). As at Kairouan, the narthex arcade, added in 991, partially obscures the original façade of the prayer hall, which had an inscription frieze above the arches (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 86–87). The prayer hall is a forest of spoliated columns, arranged in 14 arcades forming 15 aisles running in the direction of the qibla, with an elegant dome at the crossing in front of the mihrab.

Figure 5. Tunis, Zaytuna Mosque (plan N. Warner).

Figure 6. Tunis, Zaytuna Mosque, courtyard façade (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

Two features of the plan are immediately striking. The first is its irregularity. In the words of Lucien Golvin (Reference Golvin1974, 156), ‘when one looks at the plan of the Zaytuna mosque the first thing that strikes one is the disorder of its lines: not a single right angle, no parallel lines in its outline which takes the form of an irregular trapezoid’. Some scholars have explained this feature as the legacy of an earlier fortress on the sloping site, but as the irregularities are comparable to those at Kairouan, it seems to reflect the builders’ indifference to orthogonal plans. The second striking feature is that nowhere is the exterior of the Aghlabid mosque visible, as it is nestled in Tunis’ medina and entirely enveloped in later constructions. The main entrance on the north-east from the Suq al-Fakka (Figure 7) leads up a flight of steps to a Hafsid-era veranda overlooking the suq, whereas the sides of the mosque facing the covered Suq al-Attarine on the north, the Suq al-Qamus on the west, and the Suq al-Suf on the south are all obscured by shops flanking rather modest entrances into the mosque. The elegant dome in front of the mihrab is hardly visible from anywhere in the vicinity, unless one climbs onto a neighbouring roof, and the organization of the building is understandable only from within. Unlike Kairouan, the mosque had no contemporary minaret (Lamine Reference Lamine2021).

Figure 7. Tunis, Zaytuna Mosque, Hafsid-era veranda overlooking the Suq al-Fakka as seen in a nineteenth-century photochrome print (Library of Congress, 06000-06043u).

The concealed exterior of the Zaytuna mosque stands in sharp contrast to the exposed, if undecorated, present exterior of the Kairouan mosque and supports the idea that in earlier times the exterior of the Kairouan mosque was also concealed by other structures. Therefore, we should probably imagine the mosque of Kairouan not as it is today, a freestanding building surrounded by dusty streets, but as an extension of the unbroken urban fabric. Like the mosque of Tunis, it would have been understandable only from within.

This arrangement may also be the case for the congregational mosque of Sousse and possibly that of Sfax, both ninth-century foundations as well. At Sousse, in 851 a new congregational mosque was erected opposite the ribat, which had initially served as the city's mosque (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 36). Built as a rectangle 57 m wide and expanded to 50 m deep with plain (and unbuttressed) stone walls, the mosque had a regular exterior distinguished only by a projecting round tower at the north corner (Figure 8), which once served as the place for the call to prayer. The courtyard, measuring 41 × 22.25 m, is surrounded on three sides by an arcade of horseshoe-shaped arches resting on T-shaped piers. On the fourth side, the prayer hall occupied the width of the building and originally consisted of 12 arcades of three horseshoe-shaped arches supported on cruciform piers. A dome covered the bay in front of the mihrab. At the end of the ninth century even this mosque was found to be too small, so the qibla wall was demolished and the prayer hall extended with three additional bays. Although the building now stands in splendid isolation in an open plaza, early photographs show now-demolished extensions on either side of the building (Creswell Reference Creswell1940 [repr. 1979], pl. 59). Several doors on the mosque's west side had articulated arches above the opening, visible in early photographs, but this decoration was removed during restoration, presumably because it was considered to be a later addition (Creswell Reference Creswell1940 [repr. 1979], 251, pl. 59c). One wonders how much, if any, of the exterior – apart from the tower minaret at the corner – might have been meant to be seen from outside. On the interior, a cornice with an inscription in an angular script containing largely Quranic texts runs all around the court.

Figure 8. Sousse, Congregational Mosque (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

The congregational mosque of Sfax, located over 100 km south of Sousse, is generally thought to have been begun in 849, around the same time as the mosque at Sousse and presumably for the same reason: that the Muslim community was growing (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 37). Over the centuries the mosque has contracted and expanded, but is believed to preserve its Aghlabid footprint, a rectangle roughly 52 m north-south and 41 m east-west. Because of these changes, little, if any, of its ninth-century aspect remains visible either on the interior or the exterior. Its north-east façade, which has five doors and five windows set in repeatedly recessed horseshoe-arched frames united by a continuous projecting moulding with arched recesses between the window and door arches, is generally thought to date from the eleventh-century renovations to the mosque (Golvin Reference Golvin1962, 581–82).

Two small ninth-century neighbourhood mosques (masjid) in Sousse and Kairouan appear to be exceptions to this principle of interior focus. The Mosque of Bu Fatata at Sousse is a small limestone structure roofed with nine barrel vaults supported by the exterior walls and four interior cruciform piers (Figure 9). A porch the width of the entire structure precedes this prayer hall and bears an inscription in an angular script across its façade offering ‘God's blessings on [ … ] al-Aghlab b. Ibrahim’ and stating that it was ‘built to proclaim His name by the hands of …[name missing]’. It can therefore be dated to 838–41, when al-Aghlab Abu ʿIqal b. Ibrahim ruled. The presence of the inscription, which actually begins just around the right end of the façade, under the later minaret, indicates that this part of the building was meant to be seen, although in the 1970s, when I first saw it, the façade was largely hidden by a high whitewashed wall, removed, along with the whitewash on the façade, during renovation.

Figure 9. Sousse, Mosque of Bu Fatata, façade from above (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

Far more elaborate is the Mosque of the Three Doors in Kairouan, built in 866–67 by Muhammad b. Khayrun al-Andalusi, which presents an elegant carved façade at the end of a short street (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 34–35) (Figure 10). All that remains of the Aghlabid nine-bay mosque is the façade, with its attractive, but rather clumsily carved limestone inscriptions over three horseshoe-shaped arches resting on four antique columns and capitals. The two upper bands of the inscription in angular script contain two texts: Quran 33: 71–72 and a fragment of 30:4, followed by the foundation inscription: ‘Muhammad b. Khayrun al-Maʿafiri al-Andalusi ordered the construction of this mosque, wishing to be closer to God and in the hope of His pardon and mercy in the year … ’. Although the actual date is missing, a medieval author noted it as 252 (866–67), and another inscription in an angular script across the bottom band records the restoration of the mosque in 844 (1440–41), when the minaret was added.

Figure 10. Kairouan, Mosque of the Three Doors, façade (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).

Lucien Golvin (Reference Golvin1962) suggested that the Iberian origins of the patron may have led to its unusual character. It is also possible that a decorated façade was a function of the mosques’ small size and lack of a courtyard, for the somewhat-later Mosque of Bab Mardum in Toledo, built in 999–1000, is also a nine-bay mosque with an articulated façade and no courtyard (Calvo Capilla Reference Calvo Capilla2014, 672–76; Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 79–81). In any event, the Mosque of the Three Doors is the only one of the two dozen or so small mosques known from medieval Kairouan that preserves any notable architectural features, whether on the exterior or interior (Mahfoudh Reference Mahfoudh2008). Elsewhere in the Maghrib, few, if any mosques survive from this early period and the little we know about them suggests that the same system held true – there was little, if any, emphasis on articulating their exteriors (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 41–43).

Historical context

Façades briefly become more important in Ifriqiyan architecture of the tenth and eleventh centuries. The only tenth-century mosque to survive in Tunisia is the Fatimid mosque at Mahdia, which, apart from the massive projecting portal modelled on a Roman arch (Figure 11), has an otherwise undecorated exterior, appearing today much like the mosque at Sousse (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 49–51). Erected in 916 to serve the new Fatimid capital on the coast between Sousse and Sfax, the mosque was severely altered over the centuries and entirely reconstructed in the 1960s, supposedly to its original Fatimid plan. Although inscriptions normally play a large role in the decoration of later Fatimid mosques, none was found at Mahdia, whether around the courtyard, in the prayer hall, or on the portal. Although the portal was undoubtedly meant to be seen and used, perhaps as the place of the call to prayer, Creswell's early plan and photographs show that the building, apart from the portal façade, had no side doors and was once encumbered on either side by later constructions, so the isolated aspect it has today reflects a modern aesthetic rather than how it was originally intended to be seen (Creswell Reference Creswell1952–59, 1, pl. 1).

Figure 11. Mahdia, Mosque, portal (photo J.M. Bloom, 1978).

Decorated façades appear on several religious and secular buildings of the eleventh century, which Golvin (Reference Golvin1962) termed the ‘Sanhajian’ period, after the various Berber dynasties that ruled the region. In addition to the mosque of Sfax, he noted that the mosque of Sidi ʿAli ʿAmmar in Sousse, the al-Qsar mosque in Tunis, and the courtyard of the Zaytuna mosque in Tunis all dated to the eleventh century and had articulated façades. He linked these façades to those with recesses encountered on secular architecture, such as the twelfth-century Qasr al-Manar at the Qalʿa of the Bani Hammad in Algeria, as well as related twelfth-century structures in Sicily (Golvin Reference Golvin1962, 585). He might also have included the enigmatic and now-lost Burj al-ʿArif, a freestanding structure with an illegible inscription known only through a nineteenth-century drawing (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 93).) Golvin linked this new interest in façades to oriental ‘influence’, citing earlier buildings in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and even Sasanian Iran, although he neglected to explain why and how this influence appeared when it did (Golvin Reference Golvin1962, 586–89). Nevertheless, despite this brief florescence of façades in the eleventh century, exteriors were not to play an important role in subsequent Maghribi architecture, where decoration was largely limited to the interiors of prayer halls, and even courtyards remained relatively plain, although minarets got increasingly elaborate decoration (see Bloom Reference Bloom2020, chapter 4).

Looking further afield, both geographically and chronologically, as far as we can tell, all mosques newly built in the first centuries of Islam had plain exteriors. Indeed, as Creswell wrote, ‘down to the end of the third/ninth century, no mosque had a monumental entrance. All mosques, large or small, were entered by simple rectangular doorways in the enclosure walls’ (EI2, s.v. ‘Bāb’). Creswell slightly overstated his case, however, as he certainly knew that the Bab al-Wuzuraʾ had been added to the Great Mosque of Córdoba in 855–56 (Creswell Reference Creswell1940 [repr. 1979], 153). It is a monumental portal decorated with carved stone, coloured bricks, and inscriptions, and appears to have been intended for the ruler's use when he entered the mosque from his palace across the street (Brisch Reference Brisch1965; Marfil Ruiz Reference Marfil Ruiz2009). In early Islamic architecture, in contrast, elaborate façades had normally been associated with palace portals (with the notable exception of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem), where they functioned as places of waiting, presumably for some favour from the prince who lived inside (Grabar Reference Grabar1973, 148–49).

We know virtually nothing about the entrances to early Islamic palaces in the Maghrib, apart from a few poorly published plans, but early publications about the Mahdia and Córdoba portals emphasized their connections to secular architecture, seeing a frankly triumphal character in the Mahdia portal and a militaristic one in the Córdoba example (Brisch Reference Brisch1965; Lézine Reference Lézine1967, 90; Bloom Reference Bloom1980, 187–89). It is also possible that the development of articulated portals was a broader phenomenon, for the ʿAbbasid rebuilding of the Masjid al-Haram at Mecca had 23 portals, ranging from a plain, single-arched opening, to a multi-arched portal lavishly decorated in mosaic, carved teak, and other precious materials (al-Azraqī, Reference al-Azraqī and Wüstenfeld1858 [repr. 1981], 1:323 ff; Bloom Reference Bloom1980, 189–90), and a decorated portal is known from late tenth-century Isfahan in Iran (Blair Reference Blair1992, 52–53).

To some degree, the interior orientation of Islamic religious architecture can be ascribed to a shift in religious practice. Ancient worship took place largely outdoors, with an altar placed in front of a temple housing the image of the deity, so religious buildings logically emphasized the exterior. Christian worship, in contrast, gathered the faithful for worship within an enclosed space containing the altar, so that architecturally the church was a temple turned inside out. The massive columns that once surrounded the temple moved to the interior, whose surfaces might be further decorated with carvings and figural mosaics, often leaving the exterior relatively bare. Muslim worship, however, could be conducted either indoors or outdoors, as long as the space was defined and oriented towards the Kaaba in Mecca. The many columns and capitals needed to create the mosque's hypostyle prayer hall were usually shorter than those taken from temples and churches, so mosques tended to be lower structures, and decoration was normally limited to the interior courtyard façades and the dome in front of the mihrab. In a sense it could be argued that early Islamic architecture simply continued a process that had been going on for centuries.

In another sense, however, something very new was at work that is particularly visible and persistent in the Maghrib. In contrast to ancient temples and early Christian churches, which were freestanding structures, the religious buildings of early Islamic Ifriqiya – and we cannot speak about any other kind since no others survive (apart from the quasi-religious ribāṭs) – appear to have been integrated seamlessly into the urban fabric of the stereotypical Arab-Islamic city, with its labyrinth of narrow and irregular streets (O'Meara Reference O'Meara2007). With few exceptions, the congregational mosques of Ifriqiya had only internal façades, apparent only after one had entered the building from the surrounding medina. Small mosques without courtyards, used for daily worship, might have more or less elaborate façades to announce their presence, but the other sides of the building were still nestled seamlessly into the urban fabric.

This combination of interiorization and integration was certainly not exclusively a feature of Islamic religious architecture in the Maghrib, but it seems to have persisted far longer there than elsewhere. From the late tenth century, builders in Egypt, Syria, Anatolia, Iran, and Central Asia began to explore the decorative potential of their buildings’ exteriors, employing such forms as domes, minarets, and portals along with such decorative techniques as complex brickwork, coloured tile, and carved stone. The reasons for this development are, however, unclear, although Barbara Finster (Reference Finster1994, 165–68) has suggested that these were signs of sovereignty adapted from secular architecture. In contrast, Maghribi builders from Ifriqiya to the far west (present-day Morocco) largely continued to focus their attention on the interiors of buildings, apart from that brief ‘Sanhajian’ flirtation with façades, leaving their exteriors relatively plain. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries under Almoravid and Almohad patronage, even courtyards remained quite understated, although their Marinid and Zayyanid successors changed course and favoured courtyards lavishly embellished with coloured tile, carved stucco, and carved wood hidden behind largely plain exterior walls. In Ifriqiya, however, Hafsid patrons continued to favour relatively plain interiors, perhaps because of their Almohad antecedents.

As vaulting was relatively unknown throughout the Islamic architecture of the Maghrib, large domes were non-existent. Abundant supplies of wood from mountain forests provided roofs which were covered with green glazed tiles where necessary to protect underlying structures from the weather, but these utilitarian coverings hardly called particular attention to the buildings below. Minarets, however, came to be elaborately decorated with stone or brick relief patterns and colourful glazed tiles that called attention to the buildings to which they were attached, and from the fourteenth century builders from Ifriqiya to al-Andalus cautiously began to emphasize the entrances to mosques and madrasas with more elaborate portals, although the outer walls of these buildings remained austere or obscured by adjacent structures. So it is in this context that in 1293 the Hafsid ruler Abu Hafs ʿUmar b. Yahya (r. 1284–95) added two monumental and projecting entrances, the Bab al-Maʾ and the Bab Lalla Rihana (Figure 12), to the venerable Mosque of Kairouan (Bloom Reference Bloom2020, 209). At roughly the same time, a veranda overlooking the Suq al-Fakka (Figure 7) was added to the east side of the Zaytuna Mosque in Tunis, giving it an exterior façade for the first time. One should conclude that these constructions were attempts to make these revered structures, which dated back to the first centuries of Islam in the region, appear a bit more up to date.

Figure 12. Kairouan, Mosque of Sidi ʿUqba, Bab Lalla Rihana (photo J.M. Bloom, 2010).