Introduction

Despite most nations of the world having implemented some legal framework to tackle the growing environmental crises, the level of global degradation continues to accelerate at an alarming pace. The environmental crisis is multifaceted, with biodiversity loss among the most pressing concerns. Whilst governments and corporations clearly have a critical role to play in combatting the loss of species, the actions of the public are also pivotal in saving or destroying wildlife. Regarding governments’ role, the key approach in most jurisdictions appears to be the implementation of a series of conservation laws – for example, laws intending to address specific habitats or species to help save them from destruction. Such legislation attempts to control the actions of the public through the imposition of individual (and corporate) obligations, in a bid to prevent the exacerbation of these matters. The public can also make small changes in their lives in order to help protect wildlife. To do this, however, they must fully appreciate environmental issues in general, the threats to wildlife in particular and the laws aimed at tackling these threats. Those laws often arise from international conventions, thus public knowledge of the international conventions is pertinent to a wider understanding of wildlife protection. Whilst the public are becoming more environmentally aware, there seems, at least in England, to be a lack of education regarding both wildlife conservation and the relevant legislation. With poor education about our natural world and the legal instruments in place to protect it, the risk is that wildlife conservation can never be fully achieved. There are, therefore, two areas of education focused on in this paper: environmental education and environmental legal education. Though they can be interlinked, they are distinct. Environmental education relates to environmental issues generally and explores environmentalism, whilst environmental legal education provides awareness and education on the environmental laws governing a country. As will be seen in this paper, laws can impact on the behaviours and norms in society, influencing change in how the public interact and relate to the environment, as well as the public's views and behaviours impacting on legislative change. We argue that environmental legal education, though different, should be included in environmental education more generally.

Little has been written about the obligations often stipulated in conservation and biodiversity treaties of education and outreach, which the government and those drafting legislation appear to treat as boilerplate, and thus not taken seriously or actioned in practice. With the introduction of the Environment Act 2021 to address the UK's departure from the EU, further consideration needs to be given to how the public are educated on both environmental issues and the laws which seek to secure and enhance wildlife conservation, and in particular those that fulfil the requirements of the Bern Convention. It needs to be recognised that there is a greater need for environmental education for the public and, as a part of this, environmental legal education. Accordingly, this paper shares the findings of a small study into the relationship between the general public and their knowledge of biodiversity loss and a portion of the environmental policy regime pertaining to wildlife conservation within England.

Various phrases are used during this paper and it is important to define them from the outset. Environmental issues relate to human-caused threats to the environment, such as climate change, pollution, biodiversity loss etc. These issues can vary depending on locations and communities, as can the concern felt for them over time.Footnote 1 Environmentalism is argued to be both an ideology, denoting the set of beliefs, and a purposive action, to change the way people relate to the environment and also how collective action can create social environmental movements.Footnote 2 Thus, environmentalism also incorporates environmental attitudes, beliefs, and values, as well as environmental action. Where discussion relates to environmentalism, it is incorporating environmental attitudes. Further, though this study presents findings which relate to the public in England, the background provided often discusses environmentalism relating to the UK as a whole. This is due to many studies being conducted on the UK-wide population and results relating only to England not being presented separately. Again, the discussion is clear as to what relates to England specifically and what relates to other areas of the UK.

This study is a smaller part of a larger project funded by the Norwegian Research CouncilFootnote 3 looking at the norms and ambiguities within the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Washington, 1973) (CITES) and the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern, 19 September 1979) (the Bern Convention) in Norway, Germany, Spain, and the UK. This smaller part explored the English public's knowledge of biodiversity loss and the relevant legislation. The focus was on the Bern Convention in particular, because findings from the interviews from the larger project found little awareness on the part of other stakeholders – law enforcement and civil society – in the UK of the Bern ConventionFootnote 4 (though this lack of knowledge likely stems from different sources). Since public attitudes, awareness and understanding impact upon their compliance with the law, we sought to explore in more depth what people in England know about the Bern Convention and wildlife conservation more generally. The overarching research question was ‘What is the English public's awareness of the Bern Convention and perception of it and conservation in general?’Footnote 5 Before sharing the methodology of our study and the findings, we first provide background information on the relevant areas. We begin with previous studies on environmental attitudes in the UK, and the role of environmental education, including legal elements – a requirement of the Bern Convention. This is then linked to the specifics of the Bern Convention and how multiple EU directives over numerous years have transposed the Convention into the UK legal system and how this is only part of the conservation/environmental legislation. Following those sections, we then analyse the findings and suggest improvements.

1. Environmental attitudes in England

Before exploring the English public's knowledge of the UK's conservation regime, it is important to understand the environmental attitudes which have previously been investigated. It is highlighted that environmental attitudes can differ with certain characteristics, such as age, gender, socio-economic status, and education.Footnote 6 Further, a community with apathetic feelings towards the environment may contribute towards its destruction, and socio-psychological studies reveal that ‘attitudes are important determinants of environmentally oriented behaviour’.Footnote 7 Therefore, a country apathetic towards the environment is more likely to be breaching conservation laws. Further, morals and values influence environmental behaviours, though it depends on the kind of value system the individual aligns to. Stern and Dietz argue that ‘the evolved nature of human cognition makes us better able to make comparisons and follow rules than to make multiple calculations’, and thus, ‘individuals typically use rule-based methods to simplify the process of estimating utility’.Footnote 8 They identified in the literature three value bases for environmentalism: egoistic values (predisposition to protect or not protect the environment due to personal affects), altruistic values (a sense of moral obligation to others), and biospheric values (environmental effects on humans, non-humans and the biosphere).Footnote 9 Their study, published in 1994, empirically demonstrated that these three distinct values are tied to environmentalism. Further, they argued that increasing environmentalism of younger cohorts reflects a ‘value shift’, which could ‘have major implications for the future of mass environmental concern if it holds in succeeding cohorts’.Footnote 10 This work has been taken further, and subsequent studies have indicated that values can play a part in the environmental behaviours and attitudes amongst various groups.Footnote 11

Whilst it has been shown that values and morals can influence environmental behaviours, there is also an argument that laws generally can shape and change behaviours with what they regulate.Footnote 12 This can be done through fear of sanctions or rewards, but also by indirectly changing attitudes and behaviours, which Bilz and Nadler argue can be most effective, ‘particularly if the regulation changes attitudes about the underlying morality of the behaviours’.Footnote 13 As discussed above, Stern and Dietz argued that a rules-based system makes it easier for humans to understand utility and adopt certain behaviours, which is supported by Galbiati and Vertova, who state that formally outlining how people should behave and the rules they are to follow provides ‘a focal point that helps people coordinate’.Footnote 14 Thus, if people are to change environmental behaviours and adopt certain environmental actions, they must understand the rules which govern them. This can then, in turn, help to shift their morals and values to more pro-environmental attitudes and actions. Social norms, however, also play a part in how effective the law can be, either by producing a new descriptive norm or providing information about societal values.Footnote 15 For example, legislation to introduce smoking bans in various public places has the potential to influence social norms surrounding the acceptability of smoking generally and send the message to the public that it is an unacceptable behaviour, thus decreasing smoking in a country.Footnote 16 In order for environmental laws, and the resulting attitudes and behaviours, to be more successful in contributing to conservation, the law needs to reflect social norms that are already established, or make them more visible so that the public adopt them as accepted behaviour. The importance of social norms should not be underestimated, as they can also influence the effectiveness of conservation measures and the success of legislative strategies in altering behaviour.Footnote 17

A recent study has suggested that developed countries such as the UK may have surpassed their ‘maximum level’ of environmental concern and are now going to face disinterest in its preservation.Footnote 18 Conclusions made by Ficko and Boncina suggest that as a country's economic development increases, there is a consequential depletion in environmental concerns as a result. This suggests that the environments of the most developed countries are therefore under more pressure due to this decreasing concern (although they are those most able to afford to preserve nature). Specific reasons for a potential reduction in environmental concern are unclear. However, one study proposes that socio-economic conflicts may be to blame, especially for residents living in protected areas.Footnote 19 These conflicts usually arise when the infrastructure and resources within that area are curtailed as a result of conservation initiatives.Footnote 20 Thus, as Ficko and Boncina found a correlation between the industrialism (ie development) of a country with its levels of environmental protection,Footnote 21 it might be inferred by taking Afonso et al's reasoning, that the further developed countries (especially in Europe, where sophisticated networks of protected areas such as the Natura 2000 are present) may experience higher levels of conflict, as infrastructure and resource development are restricted as a result of conservation initiatives.

Whilst it is likely that conflicts between the public and environmental initiatives will happen, a recent Eurobarometer survey carried out by the European Commission in 2020 found that 94% of the respondents considered environmental protection to be personally important to them.Footnote 22 With reference specifically to the UK, a 2019 YouGov survey found that the public is more concerned about the environment than ever before, with 27% of Britons classing it as the most important issue facing the country after Brexit and health.Footnote 23 Supporting this, membership of environmental NGOs has increased substantially in the UK over recent decades, with research indicating that nearly 1 in 10 UK adults is a member of an environmental group.Footnote 24

However, despite a proclaimed support for the environment, the extent that the public are willing to act on this support is a contentious issue. A study exploring the influence of the UK public environmental attitudes on their use of non-sustainable transport found that, whilst the vast majority of participants regarded environmentalism as a very important matter, they were unprepared to stop travelling by these modes of transport even when they may have had a sufficient opportunity to walk or cycle.Footnote 25 This may suggest that in the most developed countries, such as the UK, environmental concern does not cause the majority of the public to make sacrifices if it adds inconvenience to their daily routines despite them claiming to have a desire to improve the state of the environment. A potential explanation for this is because the public place the obligation on the government to resolve the crisis. According to the Eurobarometer survey, 72% of the respondents believe their government is not doing enough for the conservation of the planet.Footnote 26 Overall, the literature and statistical data imply that the public appreciate the need to preserve the environment and therefore feel more needs to be done. However, as the public often put the onus on the government to halt degradation, this appears to result, at least sometimes, in them feeling absolved of their environmental duties. Realistically, firm governmental action is required synchronously with pro-environmental attitudes, as they are both key leverage points of successful environmental policy.Footnote 27

2. Environmental education and environmental legal education

As stated in the introduction, there is a difference between general environmental education for the public, which explores environmentalism and specific environmental issues, and environmental legal education, which provides awareness and education on the environmental laws governing a country. This section outlines the difference between the two, as well as the importance of each, starting with environmental education and then moving onto environmental legal education.

Environmental education is provided for in various international laws and obligations. From a legislative standpoint, the Bern Convention obligates parties under Article 3(3) to ‘promote education and disseminate information on the need to conserve wild flora and fauna and their habitats’. Within England, this duty is given to the appropriate conservation body; for example, section 2(1)(b) of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 states that one of the functions of Natural England includes ‘promoting nature conservation’. This promotion would ultimately educate people as to the importance of wildlife conservation and the protection of biodiversity. The need for environmental education has also been recognised in the Convention on Biological Diversity, with Chapter 36 of Agenda 21 devoted to promoting education, public awareness and training. This is due to the acknowledgment that education and public awareness play an important role in conservation and sustainability. Thus, environmental education and environmental legal education are important to fulfil our international obligations.

One way to better educate the public on environmental and conservation issues is to increase awareness using (social) media platforms.Footnote 28 Whilst this can be a relatively easy way to spread awareness and gain support for conservation, there needs to be careful consideration of the content so that it does not negatively impact on public support. Research in the US has found that newspapers and the internet can have ‘positive overall influence on knowledge holding’ when delivering environmental information, but the delivery of information through TV and radio can have a negative influence on knowledge holding.Footnote 29 It is established that mass media can influence social attitudes and perceptions of wildlife conservation,Footnote 30 and is a common source of information on wild animals.Footnote 31 Thus, it is important that the information distributed by mass media is correct to increase public understanding of the issues faced and the steps needed to mitigate them, as highlighted by Wu et al:

Although environmental concern can increase public environmental awareness, inappropriate dissemination of information may instead lead to mis-understanding of governments and experts’ decisions or actions, and may weaken the public support for government-initiated environmental policies.Footnote 32

In order to ensure that the public are properly aware of conservation issues and initiatives, with the ability to understand the media content and recognise misinformation, there needs to be sufficient education. There have been copious investigations into the effectiveness of educating younger people on environmental issues.Footnote 33 Globally, it is encouraged for such programmes to be administered in schools, with a 2010 study highlighting how ‘teachers are most influential in educating children and teenagers to be the leaders of tomorrow in protecting the environment’.Footnote 34 Therefore, Norzian suggests that teachers have a salient responsibility in demonstrating positive environmental attitudes to students, but instead are contributing ‘to the lack of pro-environmental behaviour’ amongst the younger generation.Footnote 35

Supporting this, an earlier study investigated the attitudes and the knowledge of students before and after exposure to a 10-day environmental science course.Footnote 36 This study revealed a positive correlation between environmental education and pro-environmental attitudes as almost all the students were found to have more environmentally favourable attitudes after being educated on the issues. The study also revealed that the students who scored higher in the knowledge test were found to have more environmentally positive attitudes, indicating that school education is critical in shaping a more environmentally conscious society. Other studies also highlight the importance of this matter. For example, a 2007 study examined the long-term effects of an environmental education school trip on fourth-year elementary pupils. The authors found that one year after the experience, many students remembered what they had been taught and had developed a noticeable pro-environmental attitude as a result.Footnote 37 However, with current issues intensifying and evolving at such a rapid pace, the information taught to children and young teens will likely become out of date. Therefore, education should not be restricted to schools.

Regarding UK protected areas, a recent study explored how effective these public education efforts have been.Footnote 38 This study used on-site questionnaires at various Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). The surveys were used to determine whether visitors to the site were aware of the sites’ protected status. The results revealed that less than a third of the respondents knew of the fact that they were visiting a legislatively protected area. This highlights a fundamental flaw in the education system beyond schools, with the authors stating: ‘if public support for protected areas are to be engaged and maintained, there must be awareness of the conservation activities taking place, of why they are important and of the contribution that they and nature conservation make to wider society’.Footnote 39 Furthermore, this also suggests that whilst education in schools is important with regard to inculcating positive environmental attitudes into younger people, there need to be continuous education initiatives implemented to the entire nation to ensure that the public accept and adopt environmentally-orientated attitudes and behaviours.

Supporting this further, a different study concluded that the success of conservation initiatives is reliant upon public adherence to protective programmes for species, which may depend on the ‘implementation of education programmes focusing on aesthetic, ecological and utilitarian values’.Footnote 40 Moreover, Ciocanea et al argue that conservation initiatives require ‘an active participation of local communities in decision-making processes’.Footnote 41 The importance of public participation has been discussed for years and has been incorporated into various international instruments. For example, Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration states, ‘environmental issues are best handled with participation of all concerned citizens’.Footnote 42 Within UK law, public participation is incorporated into legislation implementing the Aarhus Convention, which places an obligation on its signatories to ‘provide for early public participation, when all options are open and effective public participation can take place’.Footnote 43 Public authorities must then consider the public's comments when making their decisions. Domestically, this obligation is implemented through a number of different measures, including those implementing the EIA Directive 2011Footnote 44 and the Industrial Emissions Directive 2010.Footnote 45 Accordingly, one theme of the literature highlights the relationship between environmental education and public participation in environmental decision-making, with regards to which is more effective in increasing public adherence. However, the interplay between the two notions is complex. According to Poppe et al, environmental education and public participation ‘interact with and are influenced by each other’.Footnote 46 For example, Fitzpatricka and Sinclair discuss how education is crucial for public participation as it creates an awareness of the major environmental issues.Footnote 47 This awareness then provides ‘members of the public a foundation for effective participation in consultation initiatives’ by ensuring ‘that participants have a basic comprehension of the complex issues related to the specific project under review’.Footnote 48 However, raised awareness of the environmental issue in question has been shown to be a consequence of public participation,Footnote 49 and ‘as such, education becomes both a precondition for, and a consequence of, fair and effective consultation of stakeholders’.Footnote 50

There appears to be very little written on the public's general education on environmental laws, with the literature instead focusing on environmental legal education within higher education.Footnote 51 It is important to note that this paper does not argue that the general public are expected to have a clear and in-depth knowledge of conservation laws resulting from the Bern Convention. Some knowledge of environmental laws, however, is important and environmental legal education can ‘contribute to the formation of a new, planetary thinking, a sense of belonging and responsibility for the fate of the planet’.Footnote 52 What is argued is that the public need to have a sufficient knowledge of the laws governing conservation in England, in order to understand why they are important and potentially influence social norms and environmentalism, as discussed above.

In summary, it has been demonstrated that most citizens at least claim to hold environmentally empathetic beliefs, but this may not always lead to actions in their daily lives that contribute to conservation of the environment and habitats. They appear unaware of environmental law and/or how it links concretely to environmental protection. The Bern Convention recognised that public awareness and knowledge of environmental issues is essential.

As stated above, the Bern Convention obligates parties to promote education and disseminate information under Article 3(3); in England this duty is given to the appropriate conservation body, such as Natural England. As mentioned, it is recognised in the literature that in order to tackle conservation and environmental challenges, we need to engage society and work together to achieve change.Footnote 53 To do this, the public must be educated sufficiently on environmental issues and conservation efforts, to understand and support policy initiatives. Where, how and by whom needs to be further researched (eg school and/or adult education). The literature discussed in the sections above indicates that whilst there is environmental awareness in England, there is perhaps a lack of focus on the importance of conservation and the laws which aim to promote it. If this is so, then the Government is failing to fulfil its duty under Article 3(3) of the Bern Convention.

Based on these possibilities, and a lack of data on public knowledge of specific environmental legislation, we conducted a social survey to assess public awareness of the environment and the legislation protecting it. Before presenting the findings of the survey, the Bern Convention and how it has been transposed into EU and domestic legislation is discussed in the next section.

3. The Bern Convention and its transposition into EU and domestic law

With reference to wildlife conservation, the UK has obligations under a series of domestic legal duties, which principally stem from the transposition of international agreements and European directives. One of the most significant legal instruments governing wildlife conservation is the Bern Convention, which came into force in 1982 and aims to ‘conserve wild flora and fauna and their natural habitats, especially those species and habitats whose conservation requires the co-operation of several States, and to promote such co-operation’.Footnote 54 The minimum requirements are to promote conservation policies, consider conservation in planning and development policies and promote education and information.Footnote 55 The Bern Convention, adopted under the auspices of the Council of Europe, is mainly applied in Europe, with the EU and individual member states as signatories, but also extends to some countries in Africa, for a total of 50 signatory countries.Footnote 56 This section outlines the Bern Convention generally, before going on to discuss how it has been transposed through EU and domestic laws, and the impact of Brexit on the current conservation laws in England.

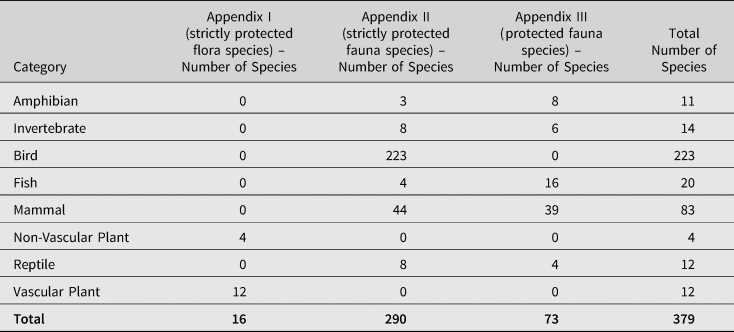

The Convention primarily prohibits the interference with, destruction of and trade in fauna and flora and does so by assigning them varying levels of protection dependent on their level of endangeredness, through listing in Appendices (I–III). The Appendices are periodically updated when the danger to a species needs to be reconsidered, and may not necessarily apply to all parties. Currently, there are over 500 wild plant species and more than 1,000 wild animal species specified in the Appendices which parties are legally required to protect where applicable.Footnote 57 Within the UK, there are 379 species (see Table 1).Footnote 58

Table 1: UK Flora and Fauna Species Protected under the Bern Convention

The table shows that birds are the most protected category, followed by mammals. There are more strictly protected fauna species than just protected fauna species. Only 16 flora species are protected under the Bern Convention in the UK. The number of protected species in the UK is relatively small compared to the Convention as a whole but, particularly for fauna, is substantial and contains the species that need conservation action within the UK.

Article 4 of the Convention mandates the protection of habitats and incorporates principles such as precaution and public participation, rather than the often-preferred way to protect wildlife, which is to regulate their destruction after it has taken place.Footnote 59 Diaz highlights that the drafting of the Bern Convention recognised the need for flexibility, as ‘the species concerned are rarely present in all European countries and that the status of those species is often different in different States’.Footnote 60 Thus, the flexibility aims to achieve ‘the minimum level of nature conservation in Europe and enable the maximum number of States to become Contracting Parties’.Footnote 61

Since its birth in 1982, perhaps the most contentious yet impactful signatory to the Bern Convention has been the EU itself.Footnote 62 As a signatory, the EU is required to implement the obligations of the Bern Convention, which then become legally binding on the EU member states. However, all 27 of those EU states are also signatories to the Bern Convention, which has resulted in complexity and overlaps within the transposition of both legal instruments, as well as tension between EU and non-EU parties, which is to be discussed.Footnote 63

The EU's relationship with the Bern Convention and the Nature Directives

The EU has transposed the Bern Convention through the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive (the Nature Directives). The Birds Directive, although consolidated in 2009, was originally enacted in 1979.Footnote 64 Its purpose is to conserve and govern the exploitation of wild birds naturally occurring in the EU, by maintaining their populations at a satisfactory level. This protection includes designating special protection areas (SPAs) for endangered birds and migratory species.Footnote 65 The purpose of the Habitats DirectiveFootnote 66 is the conservation of species and habitats, with conservation being defined as a series of measures required to maintain or restore the natural habitats and the populations of species of wild fauna and flora at a favourable status.Footnote 67 Species are protected directly through provisions that have been implemented in a way that echoes those of the Bern Convention.Footnote 68 However, over time, the protection of habitats has become the primary focus of the Habitats Directive and the EU more generally.Footnote 69 The Habitats Directive thus legislates for the creation of Special Areas of ConservationFootnote 70 (SACs). SACs cover 18% of the EU's land area, more than 8% of its marine territory, and form a network of core breeding and resting sites for rare or threatened species.Footnote 71 Member states of the EU must ensure that the sites are managed in an ecologically and economically sustainable way. Together with the SPAs mentioned above, these areas form the Natura 2000Footnote 72 – the EU's contribution to the Bern Convention's Emerald Network of Areas of Special Conservation Interest (ASCIs).

The link between the EU and the Bern Convention has not been entirely synergistic but has nonetheless had several benefits. Epstein contends that over time, the two have had a dynamic relationship whereby each has used its counterpart's strengths to compensate for its own weaknesses.Footnote 73 For example, since the funding of the Bern Convention has steadily decreased since 2008,Footnote 74 the Council of Europe has become dependent on project funding from the EU for the improvement of biodiversity across the continent.Footnote 75 However, this has resulted in the EU having the power to effectively choose the methods in which conservation measures are implemented.Footnote 76

Over time, conservation prioritisation has shifted towards the funding of projects aimed at enhancing and improving the ecological condition of habitats.Footnote 77 Thus, because the EU has opted to focus on habitat preservation rather than direct species conservation, the emphasis of the Bern Convention has swayed towards enhancing the Emerald Network/Natura 2000. For example, in 1992 the EU began the LIFE scheme, which mainly prioritises the conservation of habitats to combat biodiversity loss.Footnote 78 On the one hand, this focus has been celebrated by an array of stakeholders such as NGOs, academics, and politicians; in 2003, the House of Lords stated that LIFE had ‘enabled improvements to many Heathland SSSIs’.Footnote 79 Likewise, this focus has been celebrated by those who specialise in the protection of migratory species, such as Kate Jennings from RSPB who has informed James Ageyong Parsons that ‘there is rock solid evidence that these protected spaces work’.Footnote 80 Continuing, Jennings told how ‘EU protected species do better in countries that have SPAs than in countries that don't’,Footnote 81 and that ‘these birds do better in countries that have more and bigger SPAs… and they have done better in countries that have been inside the EU longer’.Footnote 82

On the other hand, it cannot be said for all species that habitat degradation is the biggest threat to their populations. For example, Trouburst claims that ‘deliberate killing’ has been ‘and to date remains, the prevailing human impact on large European carnivore populations’.Footnote 83 For several large carnivores, their territories are too large to be given protected status. Epstein discusses how wolves are generalists and can adapt to urbanised environments;Footnote 84 thus, rather than focusing primarily on habitat conservation, ‘direct species protection is also essential’.Footnote 85 Further, direct species protection was one of the fundamental aims of the Bern Convention, but this appears to have become of secondary importance as a result of the EU's impact on policy. Therefore, EU funding towards the enhancement of the Habitats Directive has ‘led to a shift in focus of actions pursued under the Bern Convention towards habitat conservation rather than direct species protection’.Footnote 86 Not only has the EU been able to dictate conservation policy, but it has also been argued that ‘the ability of the Convention to operate without the EU has floundered’.Footnote 87 Thus, whilst the Habitats Directive must be implemented in line with the Bern Convention, over time the Bern Convention has almost been superseded by the Habitats Directive.

Transposition of the Nature Directives into domestic law

The focus and prevalence of the Nature Directives has had large implications on UK domestic law and questions have been raised as to how Brexit will impact the British legal system since the EU's Habitats Directive has in recent years guided conservation. The main Act in England and Wales implementing the Bern Convention and Directives is the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (WCA 1981).Footnote 88 At the time of its implementation, the WCA 1981 was established to transpose the ConventionFootnote 89 and the Birds Directive.Footnote 90 The Act criminalises unlawful interference with animal and plant species and regulates licensing procedures for certain kinds of exploitation or use. Furthermore, the WCA 1981 was used to amend the law relating to SSSIs. Whilst SSSIs have not traditionally been a part of the UK's contribution towards the Emerald Network, the SPAs and SACs that do contribute are often made up of several SSSIs together,Footnote 91 with SSSIs being protected under a different legislative framework to the European sites mentioned above. The sites are designated consequent to the fauna, flora, geological or physiographical features that they contain.Footnote 92 The WCA 1981 makes it an offence to intentionally or recklessly damage or disturb SSSIs or the species living within them.Footnote 93 There are currently 4,124 SSSIs in EnglandFootnote 94 and over 1,000 in Wales.Footnote 95

Furthermore, England and Wales had to enact further legislation to transpose the Habitats Directive in 1992 and did this by implementing secondary legislation which has since been amended into what are now the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017.Footnote 96 Although required under EU law, this secondary legislation is repetitive in that it enacted the same prohibitions to protect fauna and flora as did the WCA 1981. Furthermore, the Regulations outlined the procedure for establishing a list of sites of Community Importance.Footnote 97 These sites must be selected on the basis of them hosting natural habitat types of Annex I to the Habitats Directive, or protected species of Annex II. Moreover, regulation 13 states that after this list is established, the sites are to be designated as SACs within six years, thus enhancing the Natura 2000.Footnote 98 The Law Commission has noted that the approach to wildlife conservation is ‘a complex patchwork of overlapping and sometimes conflicting provisions’.Footnote 99

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has stated that the same legal protections for SACs and SPAs will be upheld in the UK after Brexit for several reasons.Footnote 100 For the most part, there is a consensus that designated areas have improved the ecological conditions of those sites and are supported by several wildlife NGOs, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), who claim ‘Natura 2000 provides us with the best achievement of Europe in protecting biodiversity’.Footnote 101 Thus, the government has opted to retain a similar network in order to contribute to the achievement of natural and international biodiversity objectives. Furthermore, the UK remains a signatory to the Bern Convention, despite the majority of those obligations having being achieved through European law. Accordingly, the Conservation of Habitats and Species (Amendment) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019Footnote 102 were implemented to amend the aforementioned 2017 Regulations. Effectively, the legislation retains the majority of the protections that were in force pre-Brexit and transfers oversight to the appropriate domestic authorities.Footnote 103 Perhaps most importantly, the new regulations include the creation of a national protected site network within the UK territory which consists of the existing protected sites established under the Directives,Footnote 104 an amendment process for the designation of new SACs, and a new reporting system on the implementation of the Regulations. Thus, any references to Natura 2000 in the 2017 Regulations have been replaced and now refer to this national site network. Kleining has considered whether or not, in light of Brexit, the UK should continue to prioritise habitat preservation, arguing that creating a network of sites might ‘result in the creation of “islands of nature”’,Footnote 105 as well as an attitude that all non-designated land is free to exploit.Footnote 106 She concludes, however, that overall, the Natura 2000 network has ‘led to a conservation status that Europe would probably not have attained without it’.Footnote 107 Therefore, continuing to follow the EU's path in habitat conservation and ecological networks should be celebrated.

Post-Brexit implications for conservation laws in England

Since the UK is still bound by the Bern Convention, it was unlikely that the domestic legislative framework would be altered drastically. The most disconcerting issue regarding Brexit has been the loss of EU enforcement which has been paramount in the upholding of wildlife law since the Habitats Directive came to fruition in 1992.Footnote 108 Upon complaint by a signatory that another member of the Bern Convention has been in non-compliance, the Convention does have a governing body, the Standing Committee.Footnote 109 The Standing Committee is a non-binding method of dispute resolution which is directed to use its best endeavours to facilitate a friendly settlement of any difficulty to which the execution of this Convention may arise.Footnote 110 In order to achieve this, the Committee has devised a case-filing system, though the Standing Committee ‘has been hesitant to even open case-files, as doing so brings an adversarial nature to the conversation’.Footnote 111

Comparatively, the European Commission has the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The CJEU has the power to issue legally binding decisions and to financially sanction member states found to be in non-compliance with European law. It is for this reason that Donald McGillivray has claimed that anyone who thinks the Bern Convention Standing Committee ‘will be able to provide the same protections as the Nature Directives are living in a fantasy world’,Footnote 112 as the ‘toothless’ Bern Convention lacks the ‘enforcement machinery that you get in the European court system’.Footnote 113 Several pieces of EU case law can demonstrate this concern. For example, in Commission v Germany,Footnote 114 the CJEU held that by authorising the construction of the Moorburg coal-fired power plant without conducting an appropriate assessment of its implications, Germany had failed to satisfy Article 6(3) of the Habitats Directive and was therefore in non-compliance. This case highlights the enforcement power of the EU. Alternatively, Commission v Hellenic Republic Footnote 115 demonstrates the lack of enforcement power of the Bern Convention. This case involved the endangered loggerhead turtle, whose breeding behaviour was being harmed by tourism. For several years the Bern Convention had tried to negotiate with Greece and hold the country to account but this was futile, and the turtle population remained threatened. However, Greece was eventually forced to remedy the situation by the CJEU following the implementation of the Bern Convention. Thus, several scholars have feared an enforcement gap being left by Brexit,Footnote 116 though the recent Environment Act 2021 aims to calm such worries via the creation of the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP).Footnote 117

According to an Environmental Audit Committee discussing the draft Environment (Principles and Governance) Bill, the government's ambition was to create ‘a new, world-leading independent environmental watchdog’,Footnote 118 responsible for holding the government and other public bodies to account for their non-compliance with environmental law. The OEP has the power to investigate public complaints of statutory breaches of environmental law,Footnote 119 and to issue information noticesFootnote 120 (highlighting the potential breach) and then decision notices if they find the public authority to have committed a serious breach of law.Footnote 121 The decision notice will set out measures to be taken in relation to the non-compliance and suggest remedies to mitigate the situation or prevent recurrence. If the notice is not complied with, the OEP can apply to the High Court for an Environmental Review.Footnote 122 Here, the court will determine whether the authority has failed to comply with the law. If a breach is found to have occurred, then the court must make a statement of non-compliance and may grant any remedy that could be granted under judicial review, apart from damages. Whilst this new function will perhaps go some way to filling to the enforcement vacuum left by the loss of the CJEU, the OEP will not have the same level of independence as the European court. For example, the Secretary of State under section 25 is given the authority to provide guidance to the OEP as to what kind of breaches are considered serious and therefore can be subject to OEP enforcement.Footnote 123 According to Owens, ‘this offers a clear pathway for the government to lean on the OEP if it starts embarrassing the government by pointing out too many of its failings’.Footnote 124 Moreover, the inability to hand the government direct fines shows that the enforcement power is of less merit than that of the European Commission.

The OEP has not been functioning long enough to receive unduly harsh criticism, and the next year will be interesting to see how the new enforcement functions play out and compare to those of the CJEU. It will also be interesting to see how the public engage with the OEP, and whether they will use the complaints procedure in order to hold the government to account. As this paper has reiterated, the legislative framework is complex and overlapping and this may have negative implications for the public's ability to engage with the law and to highlight potential breaches by public authorities. This confusing system of legislation has led the authors to question how the public may know and engage with the conservation regimes and ultimately with environmental law more generally.

4. Methodology

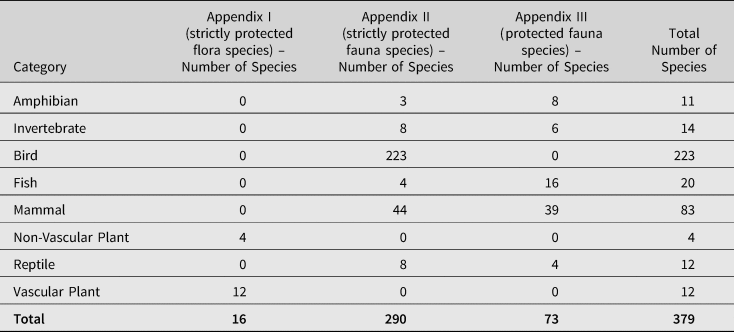

In order to gauge the public's knowledge and perceptions of environmental laws, a survey was designed and distributed using Bristol Online Surveys. The survey collected both qualitative and quantitative data, using a variety of multiple choice, Likert scale, and open text responses. Random sampling was used, and the survey was shared on various social media platforms and via email. All responses were anonymous, and we did not ask for names or contact information. The survey was open to any member of the general public resident in the UK. Overall, there were 168 responses to the survey, which was open from 17 January 2020 to 16 February 2020. Whilst there was a good range of respondents, we had limited response from Scotland (6) and Northern Ireland (1) and Wales (0). Due to the lack of responses from these countries, and a lack of generalisability, it was decided that this data be excluded, and the results from England only presented, resulting in 161 responses. Thus, any reference to laws outside of England were removed from the results presented below. Graph 1

Graph 1: Geographic range of participants.

The ages of participants varied, with 18–25 being our largest group of respondents (29.8%), followed by 46–55 (25.5%), 26–35 (16.1%), 56+ (14.9%) and finally 36–45 (13.7%). In terms of gender, 104 women and 54 men responded, with one person identifying as other and two respondents preferring not to say. We also asked for dietary requirements, and the majority of respondents ate meat, with nine vegetarians, one vegan, nine pescatarians and three declaring themselves as having another diet. The quantitative data was exported to Excel and used to make the graphs presented below. The qualitative data was collated, and provides context or further explanation behind the quantitative data.

As with all research, there were some limitations to this study, which are important to highlight for transparency. As stated above, most of the respondents were from England and responses from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were excluded, though that does not mean they are not of use or interest to those outside of England. Further, there were many more responses coming from the North of England (the location of the research team), which may have been because we used our own social media sites and email to advertise the survey. In addition, there may be a selection bias to the survey, where people interested in environmental issues chose to participate, where those not interested chose not to.

5. Findings

This section presents and discusses the results of the survey. We outline the public's general awareness and perceptions of environmental laws and conservation regimes, with a particular focus on the Bern Convention and related legislation. Further, we explored and present findings related to the public's views on whose responsibility it is to protect the environment, which issues are important and how they have been educated on environmental laws and issues. Although we never expressly asked participants their views on how the legislation relates to the different environmental issues, we were able to draw conclusions as to what is shaping the norms about environmental issues in the UK, and how little the legislation currently in place is influencing this. This directly contributes to the recommendations made in the final part of this article.

Public awareness of international environmental laws

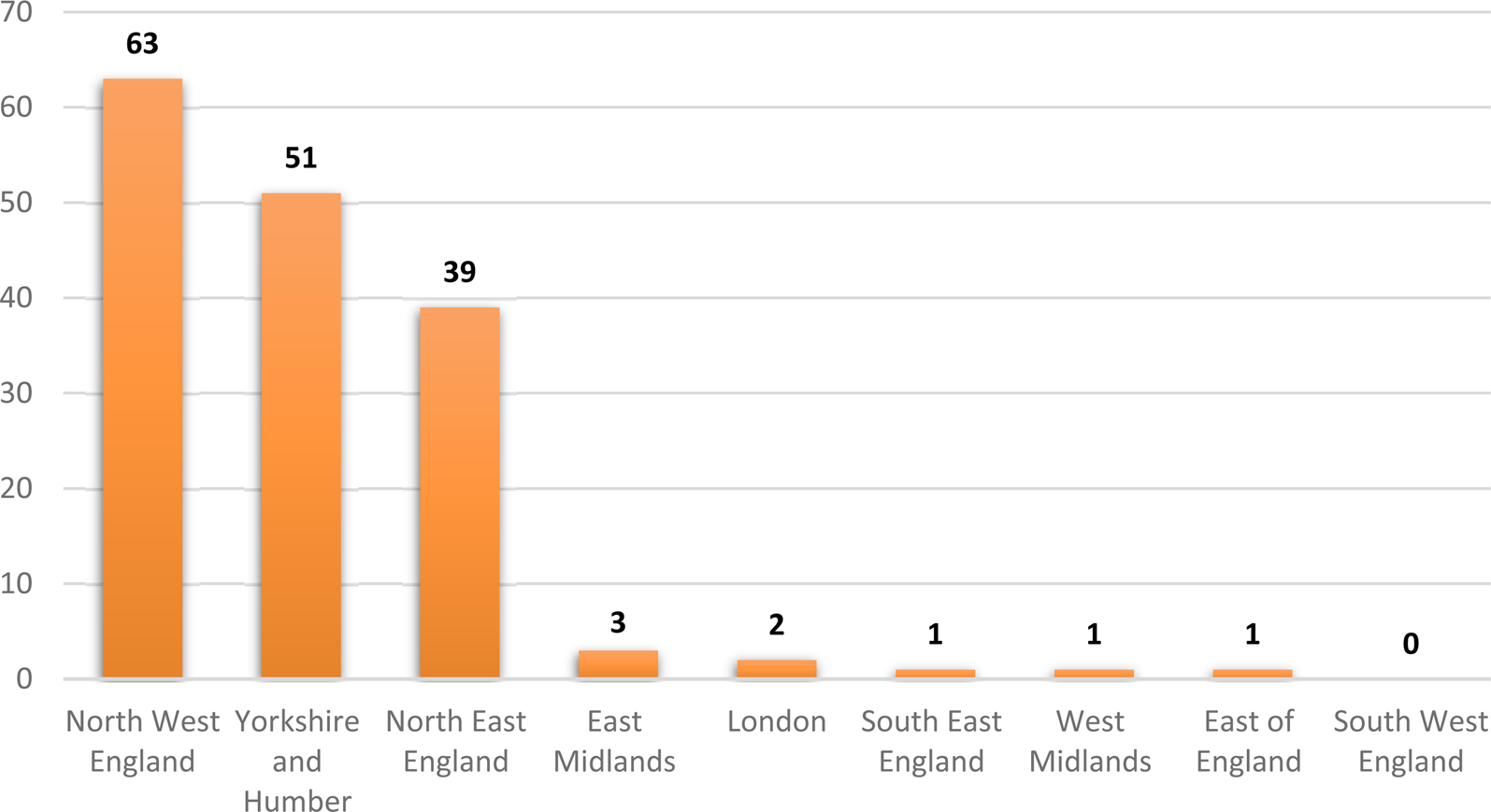

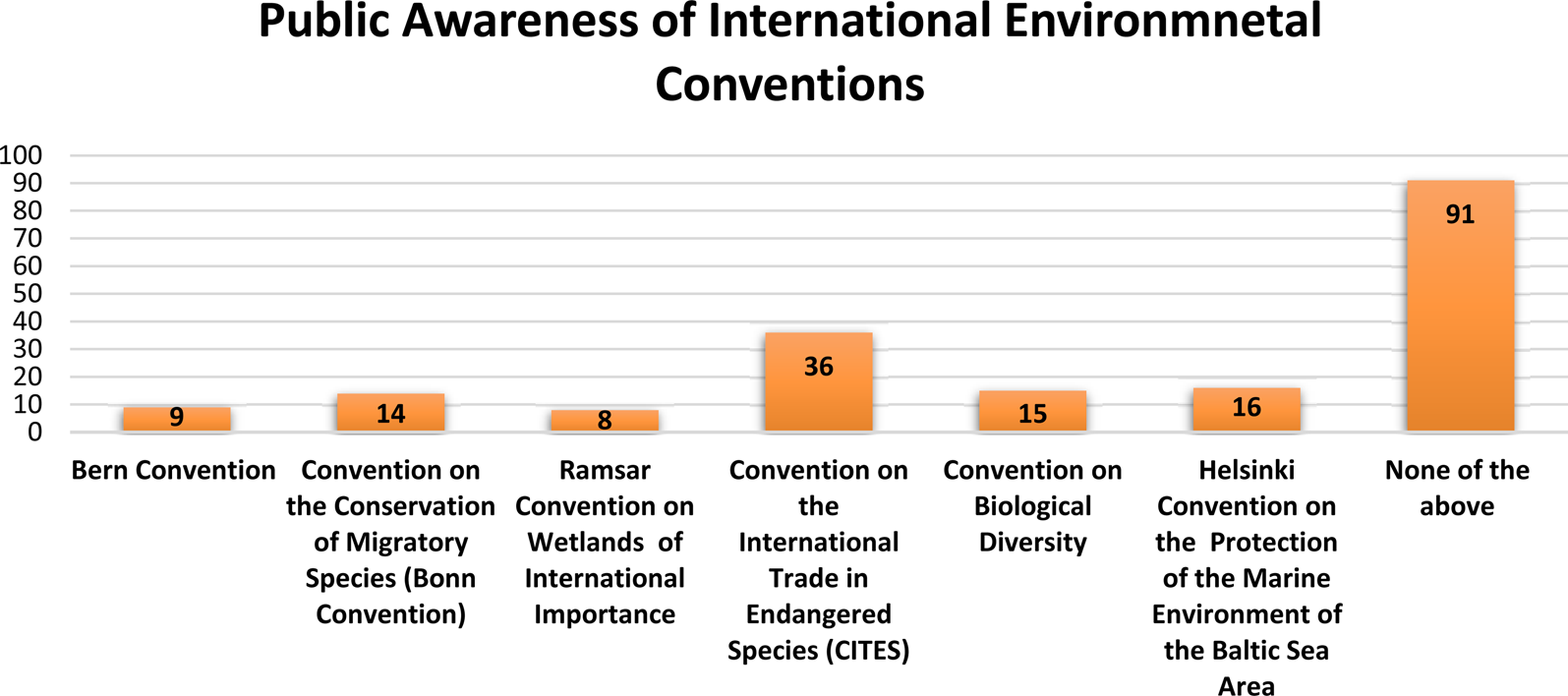

The survey asked respondents to share any environmental conventions and legislation that they were aware of. This did not require them to have a working or in-depth knowledge of the conventions, but just an awareness of their existence.

Overall, there was some awareness of conventions but 56.5% of respondents said they did not recognise any of the listed conventions. Those that did respond, had predominantly gained their insights from the news and social media as suggested, with 36 respondents saying this is how they were aware. The others were aware by conversations with family and friends (3), education (10, from school to university), and work (4). Some respondents just stated that they were familiar or listed some detail about the conventions they were familiar with (12). Overall, the knowledge of the conventions was minimal.

Although included in Graph 2 above, we asked in a separate question specifically about the public's knowledge of the Bern Convention and the Emerald Network. The survey showed that only 9 (5.6%) of respondents had heard of the Bern Convention or Emerald Network and over half of the respondents that were aware of it said only that they recognised the Convention and knew nothing of its contents or operation. Furthermore, results showed that only two respondents who had heard of the Bern Convention stated that they had learnt about environmental issues through their work or university education. Another respondent stated that they had not been educated on environmental issues, three were educated through a mixture of school, social media, and newspapers/news, two through newspapers/new alone and one stating through friends/family. Of those who had heard of the Bern Convention, however, only one person claimed to have extensive knowledge of the Convention and Emerald Network. It can be said from these findings that it appears that the Bern Convention is not commonly known about by the general public in England, and that those who are aware of it are likely to have discovered it through work and studying relevant disciplines.

Graph 2: Number of respondents with an awareness of international environmental conventions.

Public awareness of domestic environmental laws

Out of the respondents who had stated that they had not recognised any of the examples of international conventions, 92.5% of them had heard of and recognised at least one piece of domestic environmental legislation or EU Directives, listed in a later question. Three of the respondents who had not heard of the international conventions listed, however, had heard of the Bern Convention/Emerald Network. Despite most respondents being unaware of the international conventions that have influenced English legislation, the EU Directives and domestic legislation that govern wildlife conservation directly were more familiar to the participants.

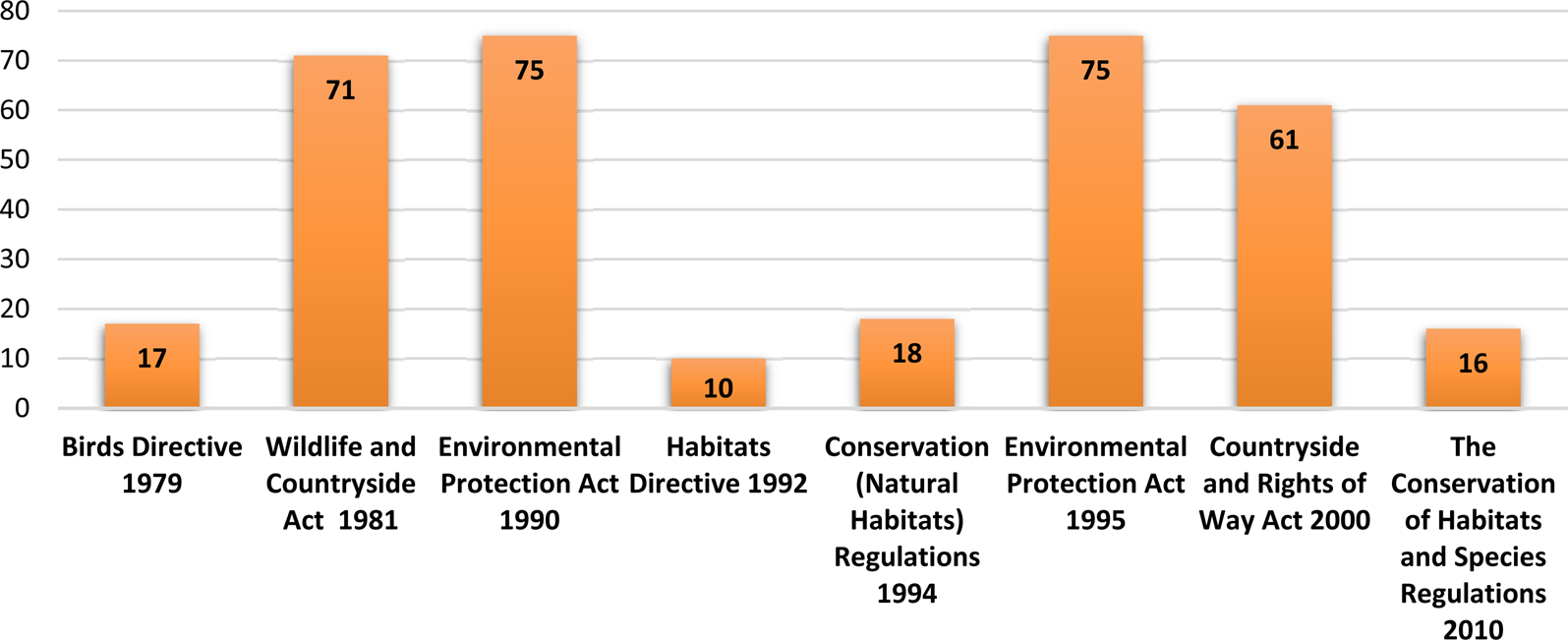

Graph 3 illustrates the number of respondents who were aware of several pieces of conservation-related legislation (primary and secondary and international), both transposing the Bern Convention and legislation not related to it. At least for the participants of our study, it seems that there is more knowledge of domestic laws relating to conservation, but little knowledge of the international legislation governing the transposition of these laws. There is also an indication that some domestic laws are more prominent than others. There is an overlap of conservation protection regimes between the WCA 1981 and the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 (revoked and replaced by the 2017 Regulations of the same name), but there was little awareness evident of the Regulations, with only 16 respondents aware of the statutory instrument compared to the 71 people aware of the WCA 1981. Ten participants had heard of the Habitats Directive, which has been the main way of implementing the Bern Convention in England. This indicates indirect awareness of the Bern Convention. The apparent low level of public knowledge of the complex array of wildlife conservation legislation, outlined in the background above, is perhaps unsurprising.

Graph 3: Awareness of domestic environmental laws.

Perceptions of sufficiency of conservation laws

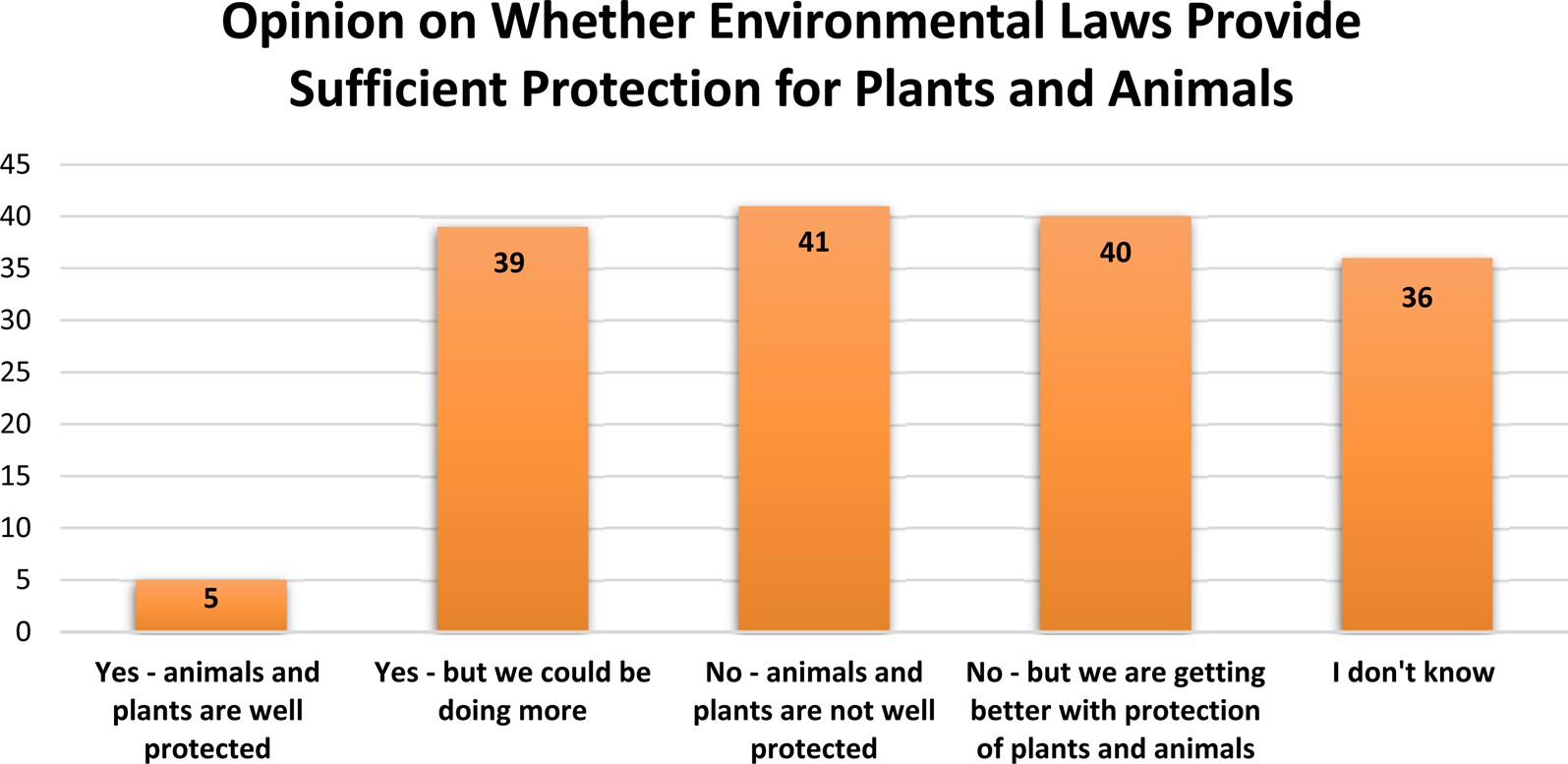

When asking the public about their perceptions as to the sufficiency of laws relating to the protection of plants and animals, 39 respondents answered ‘yes – but we could be doing more’, 41 proclaimed that ‘animals and plants are not well protected’ and 40 stated ‘no – but are getting better with protection of plants and animals’. As the WCA 1981 is the leading piece of legislation offering protection to plants and animals, these results would suggest that a large percentage of the respondents would have been aware of its existence, yet the results as shown above imply that around 100 respondents had never heard of it. This poses the question of how their response to this question has been informed, as only 36 people admitted they were unsure of the sufficiency of environmental laws. As stated in the introduction, there was no expectation that respondents would be aware of perhaps obscure legislation which governs conservation in England. It is interesting to note that they have little awareness of the main legislative framework, but strong opinions as to whether the legislation was sufficient in protecting plants and animals.

It can be seen from Graph 4 that respondents on the whole believe that environmental laws in England do not sufficiently protect plants and animals. Yet, overall, they do not express specific knowledge of that environmental legislation. This addresses one of the main aims of the project with regard to whether conventions (ie the Bern Convention) and resulting domestic legislation play a role in setting the norms in relation to wildlife and environmental conservation. The Bern Convention at least does not appear to be viewed as playing an identifiable part in norm-setting for the public, and the public's limited awareness of the Bern Convention may affect the implementation of relevant norms, though they are nevertheless in place. This may not be unusual, as domestic laws are introduced to embed international obligations and enforcement into a country. Being sufficiently familiar with domestic and EU legislation may suffice to ensure we are meeting our obligation under the Bern Convention to educate the public on conservation. The issue, however, relates back to the introductory discussion of how laws can help shape societal norms and resulting values and behaviours. If the public are not adequately educated on these laws, how do they know and understand what is expected of them for conservation compliance, and, what then is influencing or setting the norms? Further, if it is considered that environmentalism is an ideology and an action, the laws which can help influence the social norm can then feed into future environmentalism and potential behaviour change.

Graph 4: Graph showing perceptions of whether environmental laws offer sufficient protection.

Graph 5 below shows how public opinion is more in line with the Bern Convention and resulting legislation:

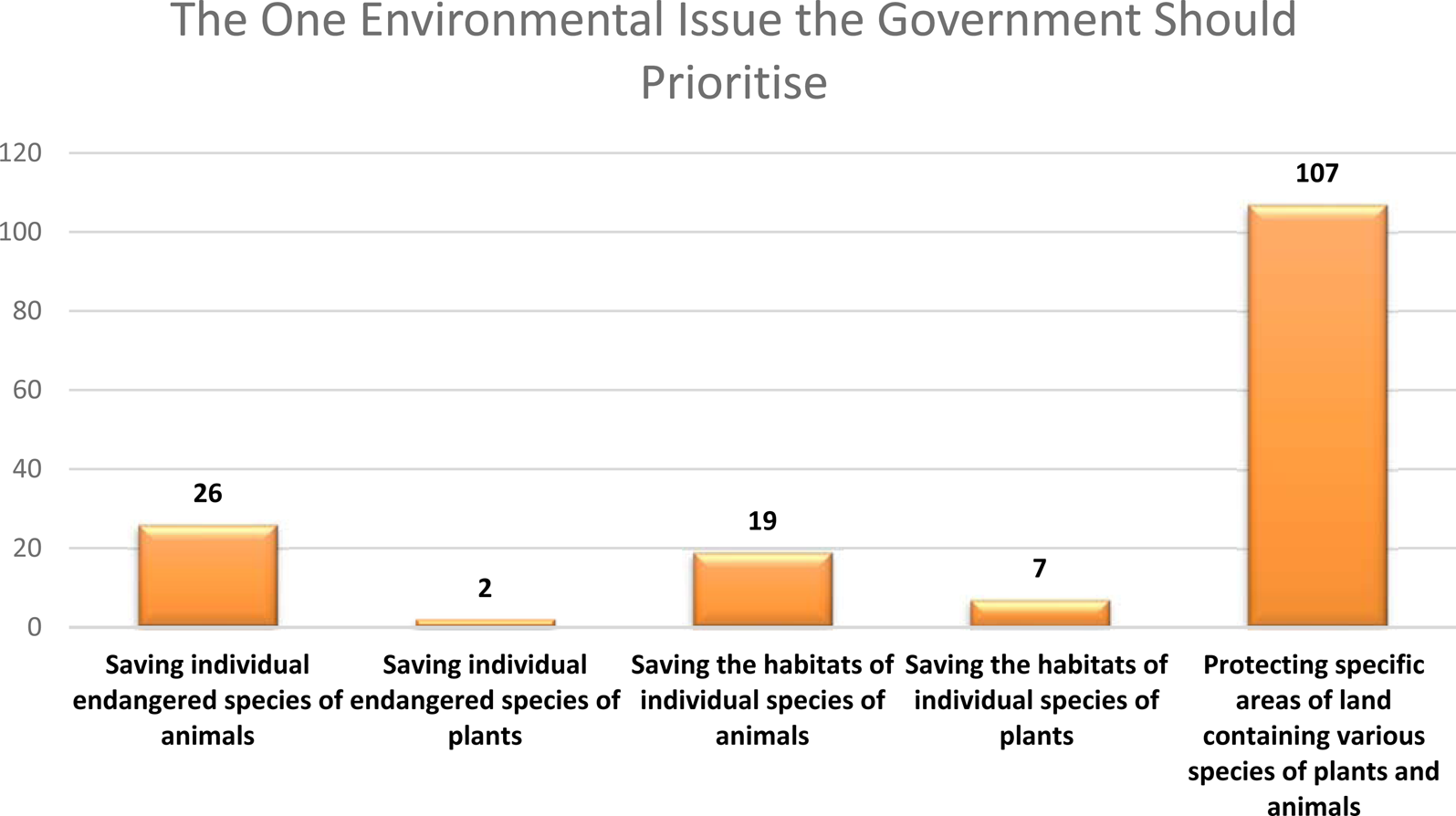

When asked to name one environmental/conservation issue that the government should prioritise, 66.5% of respondents chose protecting specific areas of land containing various species of plants and animals. Saving individual species of plants was chosen by the fewest number of participants. Thus, Graph 5 highlights that the modern method of protecting wildlife – through habitat preservation rather than direct species protection – is by far the preferred conservation technique. As previously mentioned, the decision of the EU to focus primarily on habitats has led to a marked shift in funding away from programmes supporting direct species protection. It is clear from this survey that the public actually supports this change in policy.

Graph 5: Issues respondents believe the government should prioritise.

Education

Respondents were also asked how they had been educated on environmental issues and about the laws which resulted from the Bern Convention. The apparent absence of education on important environmental issues and wildlife conservation legislation appears to be recognised by the participants of our survey, with 96.3% of respondents believing that there should be more education on these issues. A total of 12.4% of respondents said that they had not been educated on environmental issues, which highlights a need for England to do more in providing people with information on environmental issues. In relation to the way that education should be conducted, 81.9% of respondents said that pupils in primary and secondary education should be educated on conservation issues, building it into the national curriculum.

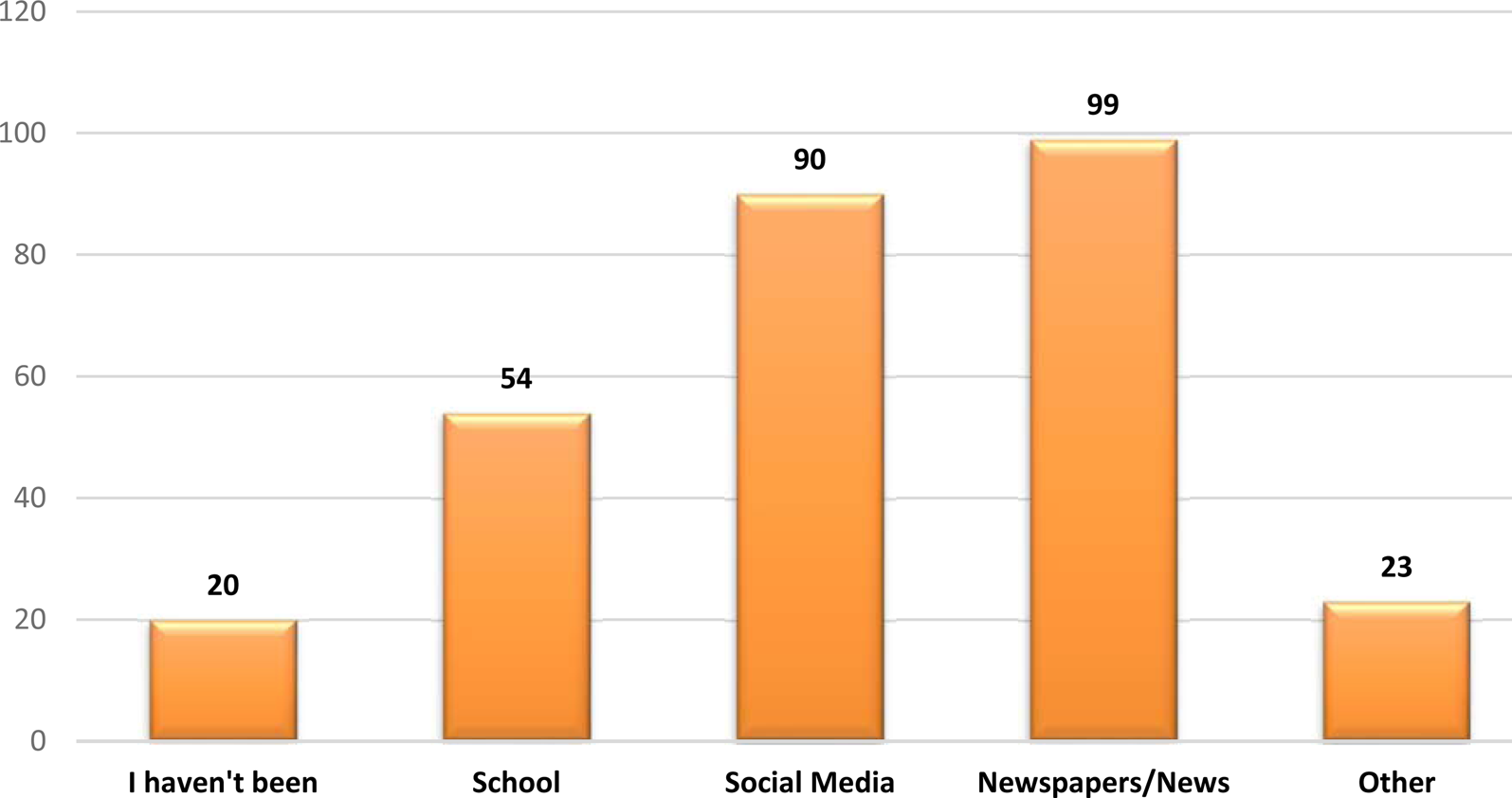

Where our respondents were getting their environmental information from varied. Graph 6 shows that the most common sources of information for the general public on environmental issues are the news and social media. Only 33.5% of respondents had learned about environmental issues and laws in school. Typed responses which expanded on ‘other’ included university (3), university and work (1), work and industry (2), self-directed research (6), family/friends (6), environmental organisations (1) agricultural environmental schemes (1), and David Attenborough documentaries or TV (3).

Graph 6: How respondents have been educated on environmental issues.

6. Discussion

Our survey has enabled us to determine where further research is needed, to better understand how the public understand environmental laws and issues, and possible ways to inform them about these laws and issues. This section will discuss the findings and provide recommendations on how the public can be made more fully aware of conservation issues and laws within England. First, further consolidation of environmental laws is needed. Secondly, environmental education, including on environmental legislation, is warranted both in school and in the wider public.

It is clear from the findings that the public in England have very little knowledge of the laws that govern wildlife conservation. The public are aware of different international treaties, particularly those which are often discussed in the media, such as the Paris Agreement 2014, but the majority of respondents have very little knowledge of international agreements aimed at protecting the environment. The knowledge of the Bern Convention/Emerald Network was extremely lacking, though this is not necessarily surprising, and those who had heard of it mostly did not know further details of it. As noted in the background section above, the laws implementing the Bern Convention have been added to over 40 years and can be confusing. The Law Commission in 2015 highlighted how ‘in the last two centuries wildlife legislation has developed in a piecemeal fashion, often in reaction to specific pressures on domestic legislation, whether local or international’,Footnote 125 primarily following the EU directives. That is not to say that the EU Directives have not made a valuable contribution to wildlife protection at the national and international levels. Through the EU's push for harmonisation and implementation, conservation and the relevant legislation has improved.

However, the English public appear to have limited knowledge of the EU directives implementing the Bern Convention at an EU level, though just under half have heard of the WCA 1981, the main legislation implementing the Bern Convention and directives on a domestic scale. Thus, respondents were more likely to have heard of domestic legislation applying in their home country, without knowing or understanding where the laws had come from. One way in which the government could help with ensuring the public understand conservation laws in England is to consolidate the legislation to make it easier to follow and be more accessible to the general public. This is an idea shared by the Law Commission, which has advocated for a new regulatory regime that ‘should take the form of a single statute, or a pair of materially identical statutes’.Footnote 126 This would incorporate ‘all legislation on the protection, control and exploitation of wild fauna and flora in England and Wales’.Footnote 127

Although the Law Commission report was published before Brexit, the fundamental call for a new statute is still a valuable suggestion in a post-Brexit England. Moreover, the legislative reform would be less complicated as a result of no longer being strictly bound by the Directives. During the implementation of the 2019 Regulations, we believe that the UK government could have used the opportunity to address other areas of the conservation regime which are lacking clarity or are in need of development. The law on conservation could have been consolidated into one large Act which would have rid the current legislative regime of ambiguity and confusion, but this opportunity was not taken upon the exit from the EU.

As seen from our results, the public are not able to keep up with all environmental legislation, nor do many have an awareness of the UK laws which are influenced by international conventions, such as the Bern Convention. Respondents mainly, however, expressed the view that conserving specific areas of land containing various species of plants and animals as the one environmental/conservation issue the government should prioritise. Thus, whilst the general public are not familiar with international laws protecting the environment, particularly the Bern Convention, their views are reflective of more modern approaches (like the Bern Convention) of protecting areas of land, rather than the older conservation methods of protecting specific species only. We cannot say why this is the case from these data, and further research is needed to understand where this knowledge comes from. It may be that more is in the news and media about protecting specific areas of land for multiple species, but this is speculation.

From our results, respondents were more likely to be concerned with an environmental issue which is talked about often and/or they had some knowledge about. For example, endangered plants were seen to be the least important environmental issue, with a common reason being that the respondents did not know about the issue. In order for the public to take these issues seriously, there needs to be a more holistic approach to education. When dealing with environmental issues, the government's usual strategy is to implement legislation, placing obligations on the public. However, if the public are unaware of the statutory protections offered to SSSIs, shown in this study and previous research, then the legislation is fruitless and unappreciated, and these sites are more likely to be damaged. For example, ‘on the first weekend after the lockdown was eased, with the sun shining, reports streamed in of cars driving onto the SSSI habitats, and of barbecues, litter, out-of-control dogs, and livestock feeding all over the New Forest’.Footnote 128 This could be a result of lockdown and members of the public acting in an unusually destructive way once they regained some freedoms. However, it relates back to the social norms and expectations of society when in the environment. If values and beliefs are what drive behaviour, and the law can help to shape these values and modify behaviour, then there appears to be a larger issue than regained freedoms. When relating it back to Stern and Dietz's identified three value bases,Footnote 129 the public appear to act more with egoistic values, rather than altruistic or biospheric values. If they had greater knowledge of conservation law, the offences they may be committing and the importance of SSSIs, they may move away from egoistic values. This demonstrates a lack of knowledge of the protection afforded to SSSIs that the conservation regime is intending to preserve; it also raises the question of whether increased statutory awareness would lead to the areas being conserved to a greater extent.

It was highlighted in the background section above that mass media can be a vehicle to make the public aware of different conservation issues, but that misinformation can be a hindrance to effective policy strategies. It should also be noted that media outlets may have a political agenda behind them and that is often a driving force in how any story is portrayed, as demonstrated by Bollin and Hamilton with regard to climate change.Footnote 130 Although the public gain environmental awareness and knowledge from various media outlets, it does not seem to be effective in educating them about the legislative conservation regime in England, nor is it always accurate in explaining environmental issues.

The following quote from the ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 2017, which discusses the recent phenomenon of ‘fake news’ on social media explains how this could be detrimental:

Social media for news consumption is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, its low cost and easy access to information, on the other hand, it enables the wide spread of ‘fake news’, i.e., low quality news with intentionally false information. The extensive spread of fake news has the potential for extremely negative impacts on individuals and society.Footnote 131

Of course, not everything seen on social media is ‘fake news’, but the heightened risk of ‘fake news’ and the relatively large percentage of respondents who rely on social media for information on environmental issues could be more harmful than helpful.

It has already been outlined how crucial the role of environmental education and environmental legal education is in the literature review. Knowledge of the environment has been shown to increase positive environmental attitudesFootnote 132 and it is generally accepted that learning about the environment in school is of particular importance, as demonstrated by the previously noted studies of Norzian and Farmer et al.Footnote 133 Clearly our sample size is small and cross generational, and general attitudes towards the environment and how it has been taught may have changed over the last 40 years. It is not possible to generalise across the country with the relatively small number of respondents to our survey. However, even taking that into consideration, the results from this question do not paint the government in the best light. Despite the research outlining how valuable it can be to learn about the environment in school, it certainly appears that not enough is being done in regard to environmental education, as the majority of respondents are learning about the environment outside of school. The gap, therefore, between the general public, legislation and the government is apparent, and we are perhaps not fulfilling our obligation under Article 3(3) of the Bern Convention to promote education and disseminate information on conservation of wild flora and fauna. The evidence that teachers can be influential in their teaching of environmental protectionFootnote 134 and the link between environmental education, including environmental legal education, and pro-environmental attitudesFootnote 135 is present in the literature, yet it seems that environmental education in schools is potentially not widespread, with current English adults having not received any formal education on these matters. As stated throughout this paper, the importance of public support on conservation initiatives depends on their awareness and understanding of the issues surrounding them and the laws governing them, to push for environmental social change. This is particularly important given that the Environment Act 2021 is now in force, and that the public can make complaints to the OEP, and the public will have more direct influence over holding public authorities to account.

The findings of our research have therefore led us to conclude that reform is needed in how education on the conservation regime takes place, but implementing further legislative measures in order to achieve this is probably unnecessary. We recommend a two-pronged approach. First, the United Kingdom Environmental Law Association (UKELA), a charity with functions including improving understanding and awareness of the law, has recognised the use of ‘multi-faceted, online options for sourcing content’ due to the prominence of social media in providing educational content.Footnote 136 UKELA has consequently decided that its four-year plan will involve adapting the way social media is used in order to maximise contact with the public. The use of social media to promote education is clearly supported by the survey results due to the large portion of respondents who claimed to source at least some of their information on environmental issues through social media. In order for the public's awareness and understanding of environmental issues to advance, we must educate using means that are accessible and favourable to them. Perhaps a consortium of civil society organisations and DEFRA could collaborate on an initiative to increase public awareness of environmental legislation via social media, in particular.

Secondly, the government should consider building such education into the national curriculum. In particular, and reinforced by the pandemic, schools should consider ‘forest schools’ or teaching in natural settings to not only increase young people's affinity and thus protection of nature,Footnote 137 but to improve mental health.Footnote 138 Natural England (and their equivalent agencies in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) could collaborate to increase the education in schools about wildlife conservation. This is the favoured measure based on our research, whereby 81.9% of respondents called for the teaching of conservation in both primary and secondary school. Other useful ideas suggested by Moss, such as ‘leaflets’ being ‘passed out at the end of year wide assemblies’ or ‘more extra-curricular activities should be funded’ would also help to spread awareness of conservation and environmental issues.Footnote 139

Conclusion

Our study sought to answer, ‘What is the English public's awareness of the Bern Convention and their education on environmental issues and laws?’ We were not the first to find that environmental legislation for England and Wales is complex, with multiple pieces of legislation implementing different portions of international conventions and EU directives. Although proposals to simplify the conservation regime have been made since well before Brexit, such consolidation of Acts has never taken place. This means that environmental legislation, including wildlife conservation as set out in the Bern Convention, sits within various pieces of transposed legislation in England and Wales. This probably contributes to the lack of public awareness due to the complexity and sheer volume of legislation. Our survey found little public knowledge of the Bern Convention along with the majority perception that England is not doing enough to protect flora and fauna. This speaks to the issue that conservation legislation (and perhaps its enforcement) may not be effective in protecting wildlife. The lack of public awareness may also stem from the lack of environmental education in formal schools, which we suggest is an area to target to improve the public's knowledge of and attitudes towards conservation. It would also improve compliance with the Bern Convention within England, which requires education in this regard. It is critical to enforce legislation to protect the environment whilst at the same time increasing people's (and corporations’) awareness of environmental degradation. These multi-pronged approaches that change people's attitudes to care more about the environment and wildlife and at the same legally ensure greater protection are vital to curbing the planet's many environmental crises.