SQUIRE LAW LIBRARY

The Squire Law Library is the library that supports the research and teaching of the Faculty of Law at the University of Cambridge. The Squire is an affiliated library of the main Cambridge University Library (UL) but is located separately in the David Williams Building with the Faculty of Law.

OPEN CAMBRIDGE

‘Open Cambridge’ is part of a national Heritage Open Day festival that aims to offer access to places not usually accessible to the public or that normally make a charge for admission. These events occur on an annual basis for people to discover more about the local history and heritage relating to their community. For the 2018 event, members of the public could book for tours and talks at college and university sites, for example a walk around Selwyn College Gardens or a tour around the University Library and its exhibition ‘Tall Tales: Secrets of the Tower’; as well as other, city-based interests such as a talk at Cambridge Fire Station, a behind the scenes look at the Cambridge branch of John Lewis or an afternoon hosted by the Mill Road History Society.

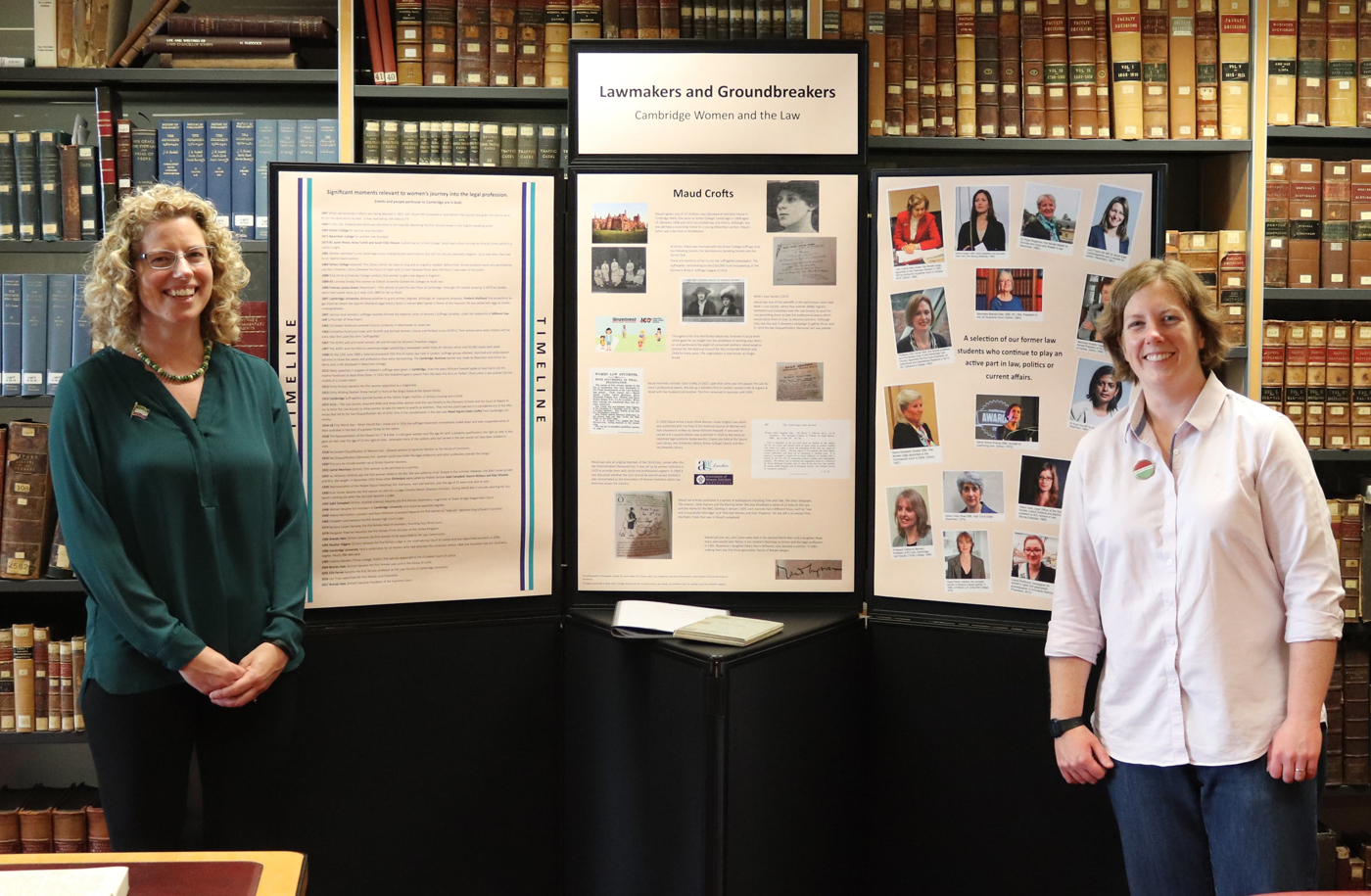

At the Squire Law Library, we wanted to participate in the 2018 Open Cambridge event too. The Squire is located in an architecturally interesting building, which opened in 1995, designed by the award-winning architects, Fosters and Partners. We decided to offer tours of the library at Open Cambridge so that members of the public could see inside the building and hear about the design. Equally, we wanted to draw attention to our exhibition called ‘Lawmakers and Groundbreakers: Cambridge Women and the Law’. The rest of this article details some highlights that were included by the exhibition.

WOMEN AND TWO CENTENARIES: 1918–2018 AND 1919–2019

As the year was 2018 it felt that it was appropriate to mark the centenary of the Representation of the People Act and, looking ahead towards 2019, to prepare material to acknowledge the centenary of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act which finally allowed women into the professions (that is, except into the clergy).

Carrie Morrison is acknowledged to be the first woman to be admitted as a solicitor and we are very proud that she was a Cambridge University graduate from Girton College. However, Carrie studied medieval and modern languages rather than law. We wanted to showcase someone who had actually studied in our faculty and someone a little less well known. Maud Crofts (nee Ingram) was the ideal candidate and, as a bonus, she was actually the first woman to be issued with a practising certificate.

Maud Ingram, one of 12 children, was educated at Hamilton House in Tunbridge Wells. She came to Girton College, Cambridge in 1908 aged 19. Between 1908 and 1912 she studied law and history. Although law was perhaps a surprising choice for a young Edwardian woman, Maud's father was a barrister in Wimbledon.

There are records showing that at Girton, Maud was involved with the Girton College Suffrage Club, the Debating Society, the Spontaneous Speaking Society and the Tennis Club. There are mentions of her in one the suffragette newspapers, The Suffragette, contributing to the £250,000 fund and speaking at the Women's Writers’ Suffrage League in 1913.

BEBB v LAW SOCIETY (1913)

Maud was one of the plaintiffs in the well-known court case Bebb v Law Society, where four women (Bebb, Ingram, Nettlefold and Costelloe) took the Law Society to court for not permitting them to take the professional exams which would allow them to become solicitors. Although they lost the case it allowed a campaign to gather force. Verkaik points out that “it was significant that costs were not awarded against the four women. While the case had been lost, the publicity and the hollowness of the Law Society's arguments had turned the tide for the women's cause”Footnote 1. Finally, in 1919 the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed.

Figure 1: Our exhibition - Lawmakers and Groundbreakers: Cambridge Women and the Law - with Kate Faulkner (left) and Lizz Edwards-Waller (right).

Figure 2: Maud Crofts. Image credit: Maud Crofts from her scrapbook held in the Women's Library.

Gwyneth Bebb had set her sights on joining the Bar but unfortunately died due to complications from childbirth after her second pregnancy in 1921.Footnote 2 Karin Costelloe retrained as a psychiatrist and Nancy Nettlefold went into business and later local government. Of the four, only Maud entered the legal profession.

MAUD CROFTS

Throughout the First World War, Maud had been involved in social work which gave her an insight into the conditions of working class women and particularly the plight of unmarried mothers. For many years Maud acted as solicitor for the National Council for the Unmarried Mother and her Child. The organisation became the National Council of One Parent Families and is now known as Gingerbread.

Figure 3: ‘Are men lawyers afraid of women's brains?’. Image credit: The Daily Sketch, 11th December 1913.

In 1914 the Committee for the Opening of the Legal Profession to Women was formed. Maud was an original member along with many other prominent men and women in legal and political life including Ray (Rachel) Strachey and the President of the Law Society, Samuel Garrett. The Committee focussed on introducing bills into Parliament. Maud, Bebb, Nettlefold and Costelloe and Dr Elizabeth Anderson met with the Lord Chancellor, Lord Haldane to gain his support. However, the First World War and a change in the office of Lord Chancellor meant progress stalled. After the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed the group held a celebration dinner on 8th March 1920 at the House of Commons. Maud and her fellow litigants were guests of honour.

Figure 4: Women Law Students. Image credit: The Times, 2nd December 1922, p.10.

Maud was also legal adviser to the Six Point Group. The Six Point Group was a group set-up by Lady Rhondda in 1921 to campaign for equality for women in six areas. The original priorities included legislation on child assault and equal pay for teachers but became refined into political, occupational, moral, social, economic and legal. Members, although usually numbering under 300, wielded considerable influence and included people such as Dorothy E. Evans and Vera Brittain.

In 1922, Maud married a fellow solicitor, Cecil Crofts. Later that same year she passed the Law Society's professional exams. She set up a solicitors firm in London named Crofts & Ingram & Wyatt with her husband and brother (or uncle – reports are conflicting). This firm remained in business until 1993.

In 1925 Maud wrote a book titled Women Under English Law which was published with the help of the National Council of Women and had a foreword written by Dame Millicent Fawcett. It was well received and a second edition was published in 1928 by the more established legal publisher Butterworths. Copies are still held at the Squire Law Library, the Cambridge University Library and other libraries across the country.

The Cambridge Law Journal book reviewer stated:

This is intended to be no more than an outline of the subject for the lay reader and should prove of great value to welfare workers and others who need to know the principles of the law, but might be confused by its details. Having regard to its purpose, the book rightly avoids difficulties, and there are no references to decided cases. It is logically arranged - a matter of no small difficulty in dealing with a branch of the law full of anomalies–clearly written and competently indexed. We should like to endorse the suggestion made in a foreword by Dame Millicent Fawcett, that in view of the fact that the position of women under English Law is changing rapidly, new editions should be frequently prepared.Footnote 3

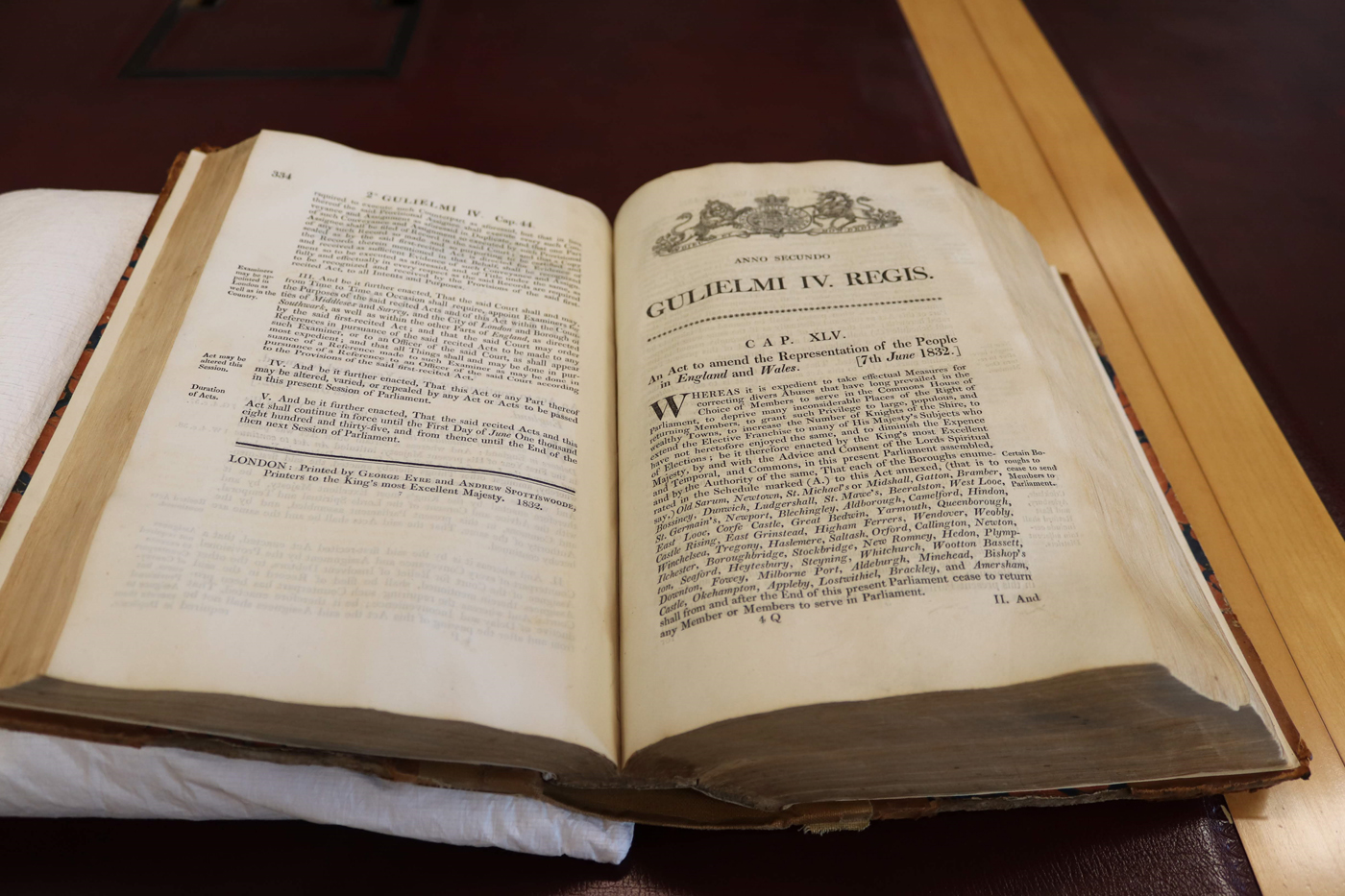

Figure 5: An Act to Amend the Representation of the People Act in England and Wales.

Most other reviews were also very complimentary although the Law Quarterly Review was not impressed with Dame Millicent Fawcett's foreword declaring it “lacks dispassionate quality.”Footnote 4

Maud was also an original member of the 1919 Club, named after the Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act. It was set up by women solicitors in 1923 to provide them with social and professional support. The Club continued until 1969 when it was discussed whether it should be wound up but instead it was reincarnated as the Association of Women Solicitors which has branches across the country.

Maud had articles published in a variety of publications including Time and Tide, The Daily Telegraph, The Listener, Daily Express and the Evening News. In an article in Legal Studies, Rosemary Auchmuty points out that “the women recognised the value of publicity”Footnote 5 before their 1913 case. But Maud continued to write even after they had won the vote and entry into the profession. Maud also broadcast a series of 12 talks on the Law and the Home for BBC radio. Starting in January 1929, each episode had a different focus, such as ‘Law and Unsuccessful Marriage’ and ‘Married Women and their Property’.

Maud had one son, John (who sadly died in the Second World War) and a daughter, Rosemary, who would later follow in her mother's footsteps to Girton and the legal profession in 1951. Rosemary's daughter (Mary Wynn-Williams), also became a solicitor, in 1981, presumably making them the first three-generation family of female solicitors in England.

Maud successfully juggled her career and family life at a time when parental leave and flexible working were unheard of. She took a reduced stake in the law firm so that she could leave early to pick her children up from school.Footnote 6 Her daughter is quoted as saying “Although we had nannies – everybody did – she would always take time off if we were ill”.Footnote 7 Maud Crofts continued practising until she retired in 1966.Footnote 8

THE EXHIBITION, 2018

In our exhibition as well as the information about Maud Crofts we displayed material illustrating key points in the suffrage movement (see Table 1 below), including items from the University Library, as well as the Squire's own collections. We aimed to highlight legislative landmarks whilst also throwing light on the personal stories of the men and women involved in the suffrage campaign. For example, visitors could view the Representation of the People Act 1832 and 1918 alongside a publication of 1907 by Annie S. Biggs: My prison life and why I am a suffragetteFootnote 9. This gave rise to some animated discussion with visitors over the tactics of suffragettes, positive discrimination and the need for more statues of women.

The display was not limited to books and pamphlets. Panko, or Votes for women: a card game dating from 1909 featuring 48 playing cards illustrated by the well-known Punch cartoonist, E.T. Reed, proved a popular addition.Footnote 10 Similarly, a Programme of banners, designed by the Artists’ League for Women's Suffrage and carried in a procession organised by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies on 13 June 1908 was a highlight for many visitors.Footnote 11 It became clear that this procession was highly organised: instructions on the reverse of the route map reminded participants that “punctuality is of the utmost importance”!

PROFESSORS FREDERIC MAITLAND AND HENRY MAINE

As a side note, when I began this project I had thought one angle would be to explore how the Cambridge Faculty of Law (the lecturers and staff) felt about women becoming lawyers. I was delighted to discover that the evidence was that the majority of the faculty supported the women's cause.

Indeed, it was gratifying to discover that Maitland had spoken out in support of women being admitted for degrees in 1897Footnote 12. He was apparently pelted with eggs by students in return for his speech. Rather fittingly, the Squire Law Library has a rare books room called the Maitland Legal History Room, which was established in the year 2000 and appropriately named after Frederic William Maitland, Downing Professorship of the Laws of England at Cambridge, 1888–1906. It is used to house our collection of antiquarian law books and is used by scholars interested in legal history. On the occasion of the Open Cambridge event we used the room to hold the exhibition.

Professor Emeritus Sir John Baker, himself Downing Professor of the Laws of England from 1998 to 2011, provided us with a letter from Sir Henry James Sumner Maine (Regius Professor of Civil Law 1847–1854 and Whewell Professor of International Law in 1887 at Cambridge) giving permission for Mary Bateson to attend his lectures in 1887. “So far as I myself am concerned you are exceedingly welcome”. However, Auchmuty points out that although privately academics were accommodating, few were prepared to put themselves outFootnote 13.

TODAY

Today, it is pleasing to say that women play a very significant role in the academic life and work of the Faculty of Law at Cambridge. Among some of those holding senior positions are Professor Catherine Barnard (Professor of European Union Law), Professor Christine Gray (Emeritus Professor of International Law), Professor Eilís Ferran (Professor of Company and Securities Law), Professor Nicola Padfield (Professor of Criminal and Penal Justice) Professor Sarah Worthington (Downing Professor of the Laws of England), and Professor Alison Young (Sir David Williams Professor of Public Law). From October 2019, the Faculty will welcome the arrival of the new Rouse Ball Professor of English Law, Professor Louise Gullifer.

POSTSCRIPT

The author would like to acknowledge the wonderful archive that is the Women's Library at the London School of Economics, where Maud Crofts’ scrapbooks are held and the essential contemporary resources of First 100 Years and Celebrating the Centenary of Women Lawyers, all essential for the preparation of our exhibition and this article.

With regard to the exhibition last September, the author wishes to acknowledge the work of her colleague, Lizz Edwards-Waller who helped greatly with the research and preparation and whose enthusiastic presentation brought the exhibits to life. Thanks are also due to her for writing the two paragraphs about the Exhibition in this article.

We are also both very grateful to the University Library Exhibitions and Public Programmes Team, the UL Rare Books Department, the UL Reference Department and Girton College Library and Archives whose support made this research and exhibition possible.

Table 1. Timeline of significant moments relevant to women's journey into the legal profession – from a Cambridge University perspective.