On July 10, 2015, a 28-year-old African American woman named Sandra Bland was pulled over by State Trooper Officer Brian Encinia in Prairie View, Texas for failing to signal a lane change. The traffic stop that followed devolved into shouting, a physical confrontation, and Bland's subsequent arrest for assaulting a public servant. What began as a routine traffic stop resulted in Bland's jailing and eventual suicide at the Waller County jail (Reference Hennessy-FiskeHennessy-Fiske 2015). These events were the subject of public outrage, especially as they came amidst a number of other police-citizen incidents, including those involving Michael Brown of Ferguson, Missouri; Eric Garner of New York City; and Tamir Rice of Cleveland, Ohio. Encinia was later indicted for perjury and his employment was terminated (Burnside & Reference Burnside and BerlingerBerlinger 2016). A wrongful death lawsuit brought by Bland's family was settled for $1.9 million (Reference HauserHauser 2016). Sandra Bland's traffic stop raises several questions with important implications for police-citizen interactions. How did a routine traffic stop become such a violent encounter? What interactional factors could explain such rapidly escalating tensions between an officer and a civilian?

Unlike many cases of police-citizen confrontations discussed in the media, Officer Encinia's dashboard camera captured the entire interaction, from the time Bland was pulled to the side of the road through Officer Encinia's call to his supervisor after the conclusion of the incident. In our analysis, we use a transcript of Bland's traffic stop and arrest to examine the rapid escalation of the encounter with a focus on procedural justice (Sunshine & Reference Sunshine and TylerTyler 2003) and the dialogic approach to legitimacy proposed by Reference Bottoms and TankebeBottoms and Tankebe (2012). While procedural justice provides a lens through which to understand how individual portions of the discourse convey legitimacy, the dialogic approach provides a broader framework for understanding the progression of the interaction. Using discourse analysis, this article will explore the formulation of procedural justice and police legitimacy in Bland's traffic stop, more specifically how authority is claimed by Encinia, how it is resisted by Bland, and the role it plays in the escalation of the encounter.

This case study of Bland's traffic stop adds to the small body of literature on the language of police-citizen interactions and is the first, to our knowledge, to focus on the language of police legitimacy and procedural justice. In analyzing the transcript of Sandra Bland's traffic stop, we address several key questions: How is procedural justice manifested linguistically? Can the dialogic legitimacy framework be used to understand the dynamics of individual police-citizen interactions? The conclusions of this analysis provide a concrete and interdisciplinary view of how procedural justice and legitimacy are manifested and negotiated in a police-citizen interaction.

Literature Review

Several bodies of literature are important in understanding the devolution of Sandra Bland's traffic stop and the manifestation of procedural justice and legitimacy therein. Here, we review the literature on race and identity in police-citizen interactions, procedural justice theory, dialogic legitimacy, and the use of discourse analysis in the legal context.

Police, Race, and Identity

It is impossible to ignore the role that race and social identity may play in today's police-citizen interactions, especially in light of the history of race and policing in the United States (Reference BerryBerry 1994; Reference Hawkins, Thomas, Cashmore and McLaughlinHawkins & Thomas 1991), police shootings of African-American men and women, and protests against the police use of force that have accompanied these events (Davey & Reference Davey and BosmanBosman 2014; Reference Lee and LandyLee & Landy 2015; Reference Mueller and SouthallMueller & Southall 2014; Reference Yan and FordYan & Ford 2015). From this perspective, it is not surprising that studies have found that minority citizens hold more negative views of police than do White citizens (Albrecht & Reference Albrecht and GreenGreen 1977; Reference DeckerDecker 1981; Reference JacobJacob 1971; Reference Lundman and KaufmanLundman & Kauffman 2003; Reference Scaglion and CondonScaglion & Condon 1980; Reference Tuch and WeitzerTuch & Weitzer 1997). Moreover, minorities perceive discrimination and misconduct to be more widespread among police than do Whites (Hagan & Reference Hagan and AlbonettiAlbonetti 1982; Reference Hagan, Shedd and PayneHagan, Shedd, & Payne 2006; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer & Tuch 2004; Reference Wortley, Hagan and MacmillanWortley, Hagan, & Macmillan 1997).

These deep-seated beliefs regarding fairness and discrimination may influence minority citizens’ interpretations of police actions. For example, in a recent mixed-methods study of citizens’ perceptions of police, Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-MarkelEpp, Maynard-Moody, and Haider-Markel (2014) found that race is a significant factor in how investigatory traffic stops are interpreted by citizens. The researchers argue that the institutionalized practice of conducting investigatory stops undermines the legitimacy of the police in the eyes of Black Americans and sends a strong message about their identity and belonging as citizens. Similarly, Reference SkoganSkogan (2012) notes that citizens’ “prior expectations could independently color how they view specific features of an encounter” (276), a statement that echoes the findings of other researchers (Levin & Reference Levin and ThomasThomas 1997; Reference RosenbaumRosenbaum et al. 2005).

Officers themselves may be subject to conscious and unconscious biases that can affect their interpretations of citizens’ words and actions (Reference CorrellCorrell et al. 2002; Reference FridellFridell 2013; Reference Lane, Kang and BanajiLane, Kang, & Banaji 2007). Relatedly, Reference PricePrice (2005) and Reference Bottoms, Tankebe, Tankebe and LeiblingBottoms and Tankebe (2014) explain that power-holders can come to believe that particular groups are not restricted by or entitled to certain moral obligations.Footnote 1 Moreover, aspects of a citizens’ “moral worthiness,” including age, sex, race, and role have been theorized to influence police actions in individual encounters (Reference MastrofskiMastrofski et al. 2016: 121). Officers’ underlying beliefs about citizens’ moral worthiness may, in turn, shape behaviors in individual interactions. For instance, recent research found that officers in Oakland, California used more informal terms when speaking with Black drivers than with White drivers. These linguistic choices may reflect officers’ unconscious biases toward Black drivers (Reference HeteyHetey et al. 2016). Taken together, this research suggests that both officer and citizen identity may influence their respective expectations and actions.

Procedurally Just Policing

Research on how to improve the relationship between the police and the public has increasingly focused on police legitimacy.Footnote 2 The concept of legitimacy originated within the political science literature, where it is defined as “the recognition of the right to govern” (as cited in Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 124). Important works in conceptualizing legitimacy include the writings of Reference WeberMax Weber (1978), David Beetham (1991), and Reference CoicaudJean-Marc Coicaud (1997). The study of legitimacy essentially addresses “whether a power-holder is justified in claiming the right to hold power over other citizens” (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 124, emphasis in original). Police legitimacy is central to the large body of procedural justice scholarship. Tom Tyler's influential and extensive work has found that police are evaluated more favorably when law enforcement officers are perceived as trustworthy, respectful, and neutral in their decision-making, and as giving people an opportunity to voice their questions and concerns (Lind & Reference Lind and TylerTyler 1988; Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine & Tyler 2003; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002). These factors are grouped into the concepts of quality of treatment and quality of decision making. Procedurally just treatment by law enforcement is associated with greater police legitimacy, while legitimacy itself is has been found to promote greater cooperation with police and compliance with the law and legal authorities (Sunshine & Reference Sunshine and TylerTyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 2006; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002).Footnote 3 The benefits of procedural justice have been recognized by scholars and practitioners alike, including the President's Task Force in Twenty-first Century Policing (2015) and others (e.g., Reference CarignanCarignan 2013; Reference MastersonMasterson 2014).

Despite the strong support that procedurally just policing has received, how to effectively translate the theoretical principles of procedural justice into police practice has received less attention. A notable exception can be found in the work of Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and MoyalJonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski, and Moyal (2013) in which the researchers operationalize procedurally justice policing. For instance, citizen participation was measured by assessing whether the officer asked for information or for the citizen's viewpoint, whether the citizen provided his or her view, and the degree to which the officer expressed interest in the citizen's viewpoint. By breaking down procedural justice into specific officer behaviors, the researchers take an important step toward understanding how citizens form their impressions of the quality of treatment and quality of decision-making they receive.

Yet, questions remain surrounding the expression of procedural justice in individual encounters. For example, which linguistic strategies law enforcement officers use to convey respect (or disrespect) toward drivers has yet to be thoroughly addressed. The formulation of questions, requests, and commands, has also been underexplored in the policing context. Moreover, the relative importance of quality of treatment and quality of decision making in shaping citizen perception of police is unclear. Do citizens care more about being treated respectfully or being treated fairly? Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-MarkelEpp et al. (2014) conclude that respectful treatment does little to improve impression of police if unaccompanied by fair policing practices, but this issue is largely unaddressed in the literature. Linguistic analysis of police-citizen dialogue can provide nuanced and multifaceted perspective to these issues.

The importance of communication in procedural justice theory is the most recent iteration of a concept that has been stressed in previous policing research. Reference ThompsonThompson (1983), for example, reports that 97 percent of police work involves communication with members of the community. The ability of officers to appropriately and skillfully communicate also features prominently in Reference MuirMuir's (1977) typology of police officers. In particular, Muir argues that language skills are a key attribute of the “professional” officer, noting they are of “critical and obvious importance” (146) in handling challenging situations without resorting to coercion. Others have also found that communicative and interactional dynamics shape citizens’ attitudes toward the police (Cox & Reference Cox and WhiteWhite 1988; Reference Giles, Dailey and Le PoireGiles et al. 2006; Reference Griffiths and WinfreeGriffiths & Winfree 1982). Officer communication skills therefore have a long history in policing scholarship. Integrating these concepts with linguistic analysis has the potential to further advance our understanding of how communication strategies affect the outcome of police-citizen encounters.

The Dialogic Approach to Legitimacy

Proposed by Reference Bottoms and TankebeBottoms and Tankebe (2012) and based on the theorizing of the political science scholar Reference WeberMax Weber (1978), the dialogic conceptualization of legitimacy is built upon the idea that legitimacy is a back-and-forth interactive process between power-holders and the public, their audience:Footnote 4

… those in power (or seeking power) in a given context make a claim to be the legitimate ruler(s); then members of the audience respond to this claim; the power-holder might adjust the nature of the claim in light of the audience's response; and this process repeats itself. It follows that legitimacy should not be viewed as a single transaction; it is more like a perpetual discussion (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 129).

This framework conceptualizes legitimacy as an ongoing process of claim and response that can be broken down into a series of steps such that 1) a power-holder claims authority; 2) the audience responds; 3) the power-holder adjusts the claim to authority; and 4) the audience responds. This process may repeat itself several times. As an example of the dialogic approach to legitimacy, the authors describe the 1981 Brixton riots in London in which perceived unjust policing practices resulted in civil unrest. The riots led to changes within the local police department, including increased efforts to recruit officers who were racially representative of the community. In this case the perceived lack of legitimacy by the police (the unfair police practices) led to a response by the citizens (the riots), which in turn led to a revised claim to legitimacy in the form of the police department's efforts to hire minority officers.

This dialogic conceptualization of legitimacy differs from the approach taken by many criminal justice scholars. Legitimacy is often thought of as being constituted solely by a concept Bottoms and Tankebe refer to as audience legitimacy, or the public's perception of the power-holder's right to wield authority (or lack thereof). As a complement to audience legitimacy, the authors emphasize the importance of power-holder legitimacy, or the authority's own “recognition of the right to govern” (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 168). Power-holders must possess the knowledge that they are justified in claiming power and authority over the public. Importantly, power-holder legitimacy is a necessary precondition to audience legitimacy. Particularly relevant to the present study is the idea that power-holder legitimacy is mutable, such that “…it is a significant test for power-holders when it becomes clear that a relevant audience has rejected one or more aspects of their initial claim to legitimacy. In such circumstances, the power-holder must put forward a revised claim to legitimacy” (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 152). Thus, power-holders’ understanding of their own legitimacy may evolve in reaction to audience feedback as part of the dialogic process.

Reference Jackson, Meško and TankebeJackson et al. (2014) suggest that the dialogic nature of legitimacy can be observed within an individual interaction between an officer and a citizen:

Consider a street stop… The dynamic partly reflects the interplay between the officer's sense of authority and power (and his or her consequent actions) and the citizen's reception of the officer's claims to power and authority (and his or her consequent actions). Reference TylerTyler (2011) has called such an encounter a “teachable moment,” in which the individual learns something about the law and legal authority and his or her status and value within some large, superordinate group. But as Bottoms and Tankebe (2013: 62) note, the encounter is also a “teachable moment” for the power-holder, because the officer learns something about his authority in the eyes of a member of the public (Reference Jackson, Meško and TankebeJackson 2014: 140).

Police legitimacy may therefore be negotiated on an individual level between an officer and a citizen. By stopping a citizen, the officer makes a claim “about his or her right to make the stop, to question the individual, and to expect them to behave in certain ways” (140). This claim is evaluated by the citizen, whose resulting actions are a product of his or her belief that the officer's claims are legitimate.

Within the dialogic approach to legitimacy, the responses of both participants are key to understanding the evolution of an encounter. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-MarkelEpp et al. (2014) make a similar observation, calling this dynamic the “tit-for-tat” hypothesis. Thus, both audience legitimacy and power-holder legitimacy must be jointly examined in any evaluation of the dialogic legitimacy framework. Such an analysis has not yet been undertaken, leaving Bottoms and Tankebe's legitimacy-as-dialogue proposition an abstract and theoretical proposition. In analyzing the transcript of Sandra Bland's traffic stop we provide, to our knowledge, the first empirical analysis of the dialogic legitimacy framework while attending to the dynamics of legitimacy via discourse.

Discourse in the Legal Context

The literature on procedural justice and police legitimacy draws on a number of methodologies including surveys (Sunshine & Reference Sunshine and TylerTyler 2003; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler & Huo 2002; among many others), interviews (e.g., Gau & Reference Gau and BrunsonBrunson 2010; Reference StoutlandStoutland 2001), observations (e.g., Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and MoyalJonathan-Zamir et al. 2013; Reference Mastrofski, Snipes and SupinaMastrofski, Snipes & Supina 1996; Reference MastrofskiMastrofski et al. 2016) and, more recently, experimental methods (e.g., Reference MazerolleMazerolle et al. 2013; Reference SahinSahin 2014). Few studies in criminal justice have addressed the linguistic strategies used by police officers and citizens in interpersonal interactions. This is an important omission, as the core messages of procedural justice are communicated verbally. To address this gap, the present analysis approaches the analysis of legitimacy from a discourse analytic perspective.

Discourse analysis highlights specific words, interactional patterns, and linguistic strategies used in conversation. Forensic linguist Roger Shuy emphasizes the importance of discourse analysis within the legal context and explains that “discourse analysis is helpful to reveal language structures and features that the jury might easily miss; to assist the jury keep track of the themes, topics and agendas of the speakers … to identify conversational strategies of the speakers; and to show how clues to the intentions of speakers are revealed through what they say” (Reference ShuyShuy 2007: 3). In addition to courtroom studies (Conley, O'Barr, & Reference Conley, O'Barr and LindLind 1979; Reference Cotterill and FlowerdewCotterill 2014), discourse analysis has been fruitfully applied to other legal contexts including police interrogations and confessions (Reference HaworthHaworth 2006; Reference HeydonHeydon 2005; Reference ShuyShuy 1998).

With only two studies focusing on the dialogue of traffic stop interactions (Reference SmithSmith 2010; Reference Gallois, Weatherall, Giles and GilesGallois, Weatherall, & Giles 2016), there is a dearth of literature on the linguistic strategies used by police officers. To our knowledge, no studies have focused on linguistic strategies used in procedurally just, or unjust, interactions or how legitimacy is claimed by officers and contested by citizens. In our analysis, we combine linguistic discourse analysis, procedural justice theory, and the dialogic approach to legitimacy and focus on the negotiation of legal authority between Officer Encinia and Sandra Bland. In particular, we highlight how the language choices of each speaker reflect their attempts to claim and contest legitimacy. In doing so, we provide an empirical analysis of these theoretical concepts as well as an interdisciplinary and holistic approach to understanding the events of Sandra Bland's traffic stop.

Method

Data: The Transcript of Sandra Bland's Traffic Stop

On the afternoon of July 10, 2015 Sandra Bland was driving on University Drive in Prairie View, Texas. She was pulled over by State Trooper Brian Encinia for failing to signal a lane change. Encinia began the traffic stop with a request for Bland's driver's license and vehicle registration information. After Bland handed Encinia these documents, the exchange between the two changed drastically. Encinia asked Bland to put out her cigarette. When Bland refused, Encinia told Bland to exit her vehicle. The exchange that followed was a heated argument between the two. Encinia drew his Taser and pointed it at Bland, after which she exited her vehicle.

Once out of the vehicle, Encinia informed Bland that she was under arrest. Bland emphasized that she did not understand why she was being placed under arrest for a failure to signal. During Encinia's ensuing attempt to place Bland under arrest, he accused Bland of kicking him and called for back-up over his radio. Bland then claimed that Encinia slammed her head into the ground. It is worth noting that the tone of both speakers is aggressive and confrontational, especially after Encinia tells Bland to exit her vehicle. Once Bland was driven away in the custody of another officer, Encinia made a call to his commanding officer to explain what had occurred during the traffic stop (Texas Department of Public Safety 2015).

The Texas Department of Public Safety released the dash camera footage of the traffic stop in response to the controversy that surrounded Bland's arrest and subsequent death in custody. In its entirety, the video is 49 minutes and 11 seconds in length. The traffic stop begins at minute 2:30 and the dialogue with Bland ends at approximately minute 15:50. The remaining video captures the officers searching Bland's car, Encinia's call to his supervisor, and Bland's car being towed. Although some of the physicality that is mentioned in the transcript (e.g., Encinia's accusation of being kicked by Bland, Bland's accusation of having her head slammed) is not visible, the audio was of high enough quality to yield a transcript of the interaction. Bland recorded a portion of the initial traffic stop on her cellphone and a bystander also approached the interaction and began to videotape. However, we limit the scope of this investigation to the dialogue captured in the dash camera footage provided by the Texas Department of Public Safety (2015).

The data for the present analysis consists of a transcript of Sandra Bland's stop. We used a 16-page transcript of Bland's stop made available by The Huffington Post (Reference GrimGrim 2015). In order to ensure the accuracy of the transcript, both authors watched the original dash camera footage, editing the transcript as necessary. Any divergence between the transcript and the footage was noted and discrepancies between the two were discussed by the authors and thus reconciled. The resulting edited transcript served as the data in the present analysis.Footnote 5

Discourse Analysis: An Interdisciplinary Approach

Discourse analysis refers to a set of analytical frameworks used to approach the formation of meaning through spoken or written language. Within the broader field of discourse analysis is a set of methodologies that focus on specific interactional features and processes of message formation and transmission. In this analysis, we will primarily analyze the data described above using the approach of interactional sociolinguistics and conversation analysis. Using these methods, we approach the question of legitimacy through the lens of individual lexical items as well as the structure of the dialogue.

Interactional sociolinguistics (IS) examines how individuals make sense of the world around them, create identity, and construct relationships via conversation. This approach incorporates methodologies from linguistics, sociology, and anthropology and applies these analytical measures to audio or audiovisual recordings of naturally occurring conversation (Reference SchiffrinSchiffrin 1994). The field of IS was founded by linguistic anthropologist John Gumperz and is also heavily influenced by the theorizing of sociologist Erving Goffman (1974) and his work on social meaning in interaction. Gumperz contributed an approach to discourse within which language is analyzed as constructing social and cultural meaning. In Gumperz's (Reference Gumperz1982a, Reference Gumperz and Gumperz1982b) work on cross-cultural communication, he examined how speakers interpret interactions by means of interpreting speaker-produced “contextualization cues,” or the linguistic and paralinguistic features that allow participants in interactions to understand what is intended by an utterance.

A second form of discourse analysis used in the present analysis is the framework of conversation analysis (CA). Sociologists Reference Sacks, Schegloff and JeffersonSacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974) developed this field as an interdisciplinary approach to examining conversation. Similar to IS, CA is applied to data from audio or audio-visual recorded naturally occurring conversations. In CA, the analytical focus lies in the microinteractional processes used by speakers to convey meaning, including word choice, turn-taking, pauses, and other means of message formulation. Importantly, analysis within a CA framework examines solely the linguistic structures present within an interaction, without taking into consideration contextual pre-existing power structures or outside knowledge of the interlocutors’ relationship (Reference van Dijkvan Dijk 1997).

CA's focus on the notion of turn-taking, or the shift between speakers’ turns at talking, is particularly relevant to the present analysis. There has been extensive work on the allocation of turns between speakers (see Sacks, Schegloff, & Reference Sacks, Schegloff and JeffersonJefferson 1974). Moreover, in recent years, within the field of CA epistemics and interaction have been examined in great depth. As Reference Heritage, Sidnell and StiversHeritage (2013) states, epistemics in CA “focuses on the knowledge claims that interactants assert, contest, and defend in and through turns-at-talk and sequences of interaction” (370). Similarly, Reference van Dijkvan Dijk (2014) expands upon this idea of epistemics, or knowledge in interaction, stating that “CA has more recently begun to explore which speakers may express what kind of knowledge to what kind of recipients, and how entitlements, responsibility, imbalances and norms influence such talk” (9). The CA approach is therefore an analytical tool that can be used to examine potential knowledge discrepancies within conversation, and is directly applicable to transcript of Sandra Bland's arrest.

The Present Study

In our analysis, we assess how linguistic strategies reflect the distribution and contestation of power, authority, and knowledge between a civilian and a law enforcement officer. We draw upon the methodologies of IS and CA to analyze an array of conversational events that relate to procedural justice and institutional legitimacy in the routine traffic stop that culminated in the arrest of Sandra Bland. The linguistic resources of each interlocutor are examined with an eye toward the strategies used by each to bolster their respective positions. Our study makes several contributions to the literature on procedural justice and legitimacy.

First, the applicability of the legitimacy-as-dialogue framework to a real-world scenario has yet to be tested. In this vein, our study provides an empirical analysis of the dialogic framework that has thus far not been attempted. Further, we examine the linguistic mechanics of procedural justice and how they shape the interaction. In this way, the present study examines the ways in which theoretical concepts from procedural justice theory and dialogic legitimacy are manifested in an actual police-citizen encounter.

Analysis

The present analysis is organized around three linguistic elements that reflect the contested nature of legitimacy in Bland's traffic stop: the use of questions, the escalation of requests, and access to jargon and epistemics.

Questions

Questions are a central communicative element within procedural justice theory. The extent to which officers attend to citizen questions and concerns has been used as a measure of citizen participation and police fairness in citizen surveys measuring procedural justice.Footnote 6 Additionally, officer invitations for citizens to ask questions were an operationalization of citizen participation in sample scripts and approved key messages in the Queensland Community Engagement Trial (Reference MazerolleMazerolle et al. 2011) and in the Scotland Community Engagement Trial (MacQueen & Reference MacQueen and BradfordBradford 2015), two field trials of procedural justice. Questions therefore play an important role in procedural justice theory. Within this section, we will discuss the frequency and type of question per participant in the interaction as well as the presence or absence of an appropriate answer to the question. Finally, we will address the legitimacy implications of these features within the interaction.

First, we consider the distribution of the question-asking. Table 1 displays three categories of participants: Sandra Bland, Officer Encinia, and other institutional representatives (the back-up officers who were called to assist Encinia as well as a paramedic). Additionally, we have examined the number of questions the individual asks and the number of questions that were answered by the interlocutors. As demonstrated in Table 1, of the 51 total questions in the interaction Sandra Bland asks 67% of questions, by far the largest percentage.

Table 1. Questions and Answers by Speaker

Bland's extensive use of questions is noteworthy because scholars of institutional discourse, especially within the judicial system, conclude that it is rare for the layperson to pose questions (Agar 1984; Reference Cotterill and FlowerdewCotterill 2014; Shuy 1983). Typically, a layperson is restricted to responses that conform to the question being posed by the institutional representative. Similarly, by nature of the structure of institutional interactions, the layperson is generally constrained in what type of questions he or she is able to ask. This structure ensures that the institutional representatives control the topic of the conversation as well as constrain the type and amount of participation from the layperson. If the layperson poses a question, it is typically limited to requests for clarification (Reference AgarAgar 1985; Shuy 1983). Outside the court context, other scholars have noted that questions allow speakers to control the direction of the interaction (Reference Ainsworth-VaughnAinsworth-Vaughn 1998) and introduce topics (Reference SmithSmith 2010). Questions, therefore, “gain the asker power” (Reference SmithSmith 2010: 178).

The relatively informal nature of traffic stops results in these interactions being a combination of a formal, institutional discourse and an informal one. This melding of contexts makes Bland's many questions not technically inappropriate, but somewhat unexpected because questions are a marker of power in discourse (Reference Ainsworth-VaughnAinsworth-Vaughn 1998; Reference SmithSmith 2010). As the layperson, Bland does not have the institutionally granted power to direct the discourse, while Encinia does. Moreover, the content of Bland's questions does not conform to that of a layperson, as she not only requests additional information but also challenges Officer Encinia's actions: “When are you going to let me go?”; “Why do I have to put out my cigarette?”; “Why won't you tell me that part?”; and “Why am I being arrested?” Importantly, approximately 26% of Bland's questions begin with “Why”, indicating a request for an explanation of reasons (Reference KouraKoura 1988). This linguistic construction reveals that Bland uses questions to ask for a Basic Legitimation Demand, defined as a “demand … that the power-holder should offer normatively appropriate reasons why the citizen must obey the command” (Bottoms & Tankebe forthcoming: 13). Through her use of questions, Bland calls on Encinia to provide her with a reasonable “legitimation story” that would provide justification for his demands (Tankebe, personal communication). By posing these questions, Bland therefore communicates her doubts that Encinia is a legitimate authority with the power to direct her actions.

Key to discerning the role of questions in the evolution of the encounter is understanding their reception and interpretation by Encinia. As noted by Reference Jackson, Meško and TankebeJackson et al. (2014) in their discussion of dialogic legitimacy, in an encounter the officer “learns something about his authority in the eyes of a member of the public,” calling this a “teachable moment” (140). What message does Bland's unusual use of questions convey to Encinia? Bland uses questions as a tool to challenge Encinia's legitimacy and his actions as an institutional representative. This is accomplished in two ways. First, by asking questions Bland demonstrates that she chooses not to act within the boundaries of what is expected of her as a layperson when speaking to an institutional representative. Second, and more importantly, the content of her questions is a direct challenge to Encinia's actions, as she constantly demands that Encinia justify his commands to her. Bland's use of questions therefore sends the clear message that she does not accept Encinia's claim to legitimacy.

Within the dialogic legitimacy framework, the power-holder's response to a legitimacy challenge is key. After the citizen's challenge, the power-holder may revise his claim to legitimacy. In the case of Bland's traffic stop, it is instructive to examine how Encinia responds to the Basic Legitimation Demand that Bland conveys through her questions. As referenced in Table 1, Encinia responds to only two of Bland's questions:

(1) Q: Bland: When are you going to let me go?

A: Encinia: I don't know.

(2) Q: Bland: Why will you not tell me what's going on?

A: Encinia: You are not complying.

The findings of research in procedural justice theory suggest that, were Encinia's to give full explanations for his decisions, these would contribute to his legitimacy in the interaction. Rather than attend to her concerns, Encinia only answers two of Bland's fifty-one questions. Even in these two instances, Encinia's responses leave much to be desired. Both answers are short, vague, and lacking in detail, hardly a robust response to Bland's demand for a legitimation story.Footnote 7

Encinia's refusal to address Bland's Basic Legitimation Demand is his response to Bland's legitimacy challenge. This decision is likely an attempt to maintain the expected conversational conventions in which the layperson does not have the power or the right to ask questions. That is, by refusing to answer her questions, Encinia establishes that he has the right to govern how the interaction unfolds. At the same time, Encinia's strategy reflects two ways in which the procedural injustice of the interaction is manifested. First, expressing interest in the citizen's information or viewpoints is one way that officers can add to the procedurally just nature of an encounter (Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and MoyalJonathan-Zamir et al. 2013). Conversely, being dismissive of citizen concerns is an aspect of procedural injustice. Instead of addressing Bland's questions and demonstrating a concern for her questions, Encinia focuses on maintaining his legal authority through his control of the discourse. Second, providing citizens with an explanation for their decisions is another strategy for procedurally fair policing that can contribute to the perceived neutrality of a decision (Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and MoyalJonathan-Zamir et al. 2013; see also MacQueen & Reference MacQueen and BradfordBradford 2015). By not explaining himself, Encinia not only loses another opportunity to build procedural justice in the encounter but also actively contributes to the perceived injustice of his actions.

Consistent with dialogic legitimacy, Encinia's strategy appears to reaffirm Bland's belief that this law enforcement officer is not a legitimate authority because he refuses to answer her questions, address her concerns, or provider her with a legitimation narrative. Moreover, Encinia's lack of responsiveness is one way in which the procedural injustice of the encounter is manifested. Interpreted through the lens of dialogic legitimacy, Encinia's refusal to answer Bland's questions is an attempt to retain his legitimacy in the face of her challenges, but is one that in the end only appears to further the discord.

Requests and Commands

Requests and commands are a second communicative feature that reflect Encinia's attempts to maintain legitimacy in the traffic stop. This aspect of the interaction is best understood within the framework of politeness theory (Brown & Reference Brown and LevinsonLevinson 1987). In their theory, Brown and Levinson outline a detailed set of linguistic techniques used by speakers to maintain the “face” of their conversational partner.Footnote 8 Face is an individual's public self, taken into consideration by speakers in their interactions. A hearer's face can be threatened through speech that is disrespectful to the individual, or elevated through respectful or thoughtful actions. This conceptualization of politeness is closely tied to the notion of quality of treatment in procedural justice. Officer respect for citizens has consistently been found to be a large factor in citizen evaluations of police. For example, Reference Jonathan-Zamir, Mastrofski and MoyalJonathan-Zamir et al. (2013) found that “the dignity indicator shows the strongest relationship to satisfaction” (862). Both procedural justice theory and politeness theory highlight how language can be used as a tool to promote rapport. We have chosen requests and commands as the focus of the present analysis because speakers are likely be particularly sensitive to their composition due to the way in which they can impose, perhaps unwantedly, on the face needs of the other person (Brown & Reference Brown and LevinsonLevinson 1987). As outlined below, concepts from politeness theory can be used to understand how Encinia's language shifts as Bland challenges his legitimacy.

The linguistic escalation of Encinia's requests and commands is most clearly illustrated in the excerpt below, which takes place approximately 9 minutes into the recording:

(3) Encinia: You mind putting out your cigarette, please? If you don't mind?

Bland: (pause) I'm in my car, why do I have to put out my cigarette?

Encinia: Well you can step on out now.

Bland: I don't have to step out of my car.

Encinia: Step out of the car.

Bland: (as Encinia opens her car door) Why am I…

Encinia: Step out of the car.

Bland: (Overlapping) No, you don't have the right. No, you don't have the right.

Encinia: Step out of the car.

Bland: You do not have the right. You do not have the right to do this.

Encinia: I do have the right, now step out or I will remove you (overlapping)

Bland: I refuse to talk to you other than to identify myself.

Encinia: Step out or I will remove you.

Bland: I am getting removed for a failure to signal? (overlapping)

Encinia: Step out or I will remove you. I'm giving you a lawful order. (pause) Get out of the car now or I'm going to remove you.

Bland: (Overlapping) I'm calling my lawyer. And I'm calling my lawyer.

Encinia: I'm going to yank you out of here. (Reaches inside the car.)

The first line of this sequence (“You mind putting out your cigarette, please? If you don't mind?”) is Encinia's initial attempt to direct Bland's actions. Encinia phrases this first claim to legitimacy as set of two questions, rather than as a direct command. Alternatively, Encinia might have used the imperative construction “Put out your cigarette.” Encinia chooses to phrase his claim in a question format instead. Questions are less threatening to a hearer than a direct command because this linguistic construction does not presuppose that the hearer must comply (Brown & Reference Brown and LevinsonLevinson 1987). At the same time, within the context of a traffic stop questions are commonly understood to be commands when uttered by a law enforcement officer (Solan & Tiersma 2005). Alternatively, Encinia's choice of phrasing may be due to the fact that smoking a cigarette is not unlawful, therefore he had little authority to command her to put out her cigarette. In either interpretation, Encinia effectively asserts his right to influence Bland's actions while simultaneously beginning the sequence by avoiding a direct command.Footnote 9

In her response, Bland does not acquiesce by putting out her cigarette. Instead, she counters with a question of her own (“I'm in my car, why do I have to put out my cigarette?”). This conversational turn represents the second step in Bottoms and Tankebe's dialogic legitimacy framework, in which the audience (Bland) responds to the power-holder's (Encinia's) claim to power. Instead of accepting Encinia's questions as the implied command that they are, Bland calls into question Encinia's right to control her. By challenging Encinia's request, rather than complying, Bland sends a clear message to Encinia: if he is to successfully assert his authority to direct her actions, he must explain the basis for his request. This conversational turn further adds to the argument that Bland does not view Encinia as a legitimate authority.

As predicted by the dialogic approach, Encinia revises his claim to legitimacy in the following line: “Well you can step on out now.” Here, Encinia reasserts and strengthens his institutional right to power. The revised nature of this claim is evident in the linguistic structure of this turn. Here, Encinia escalates both the nature of his command and the linguistic form it takes. Encinia now tells Bland to exit her vehicle, rather than simply put out her cigarette. This action not only requires more effort from her than before but would also cause Bland to leave the physical protection of her vehicle. Additionally, the structure of the command shifts from the question construction used previously (“You mind putting out your cigarette, please? If you don't mind?”), to a command (“Well you can step on out now”).

On its surface, this turn still maintains politeness forms, including the modal “can” and the informal “step on out,” both of which fall into Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson's (1987) characterization how to avoid threatening a speaker's autonomy. Encinia's use of “can” is interesting, since the word itself conveys an ability to act. However, since it is issued by an authority it implies a command and is therefore used in an ironic sense. Nevertheless, Encinia's word choice reflects that even after Bland's challenge, Encinia continues to assert his right to power. It is also instructive to note Encinia's use of the discourse marker “well.” Lakoff (1973) has examined “well” as a preface to a response that is an insufficient or unsatisfactory answer to a question, other scholars have found similar conversational moves wherein “well” signals disagreement (Reference Pomerantz, Maxwell Atkinson and HeritagePomerantz 1984) or noncompliance with a request (Wootton 1981). We therefore conclude that Encinia's “well” signals that Bland may interpret the words that follow as unsatisfactory.

Mirroring Encinia's sentence structure, Bland counters his statement with a statement of her own: “I don't have to step out of my car.” As in her previous line, Bland again demonstrates her belief that Encinia's request is unfounded and illegitimate. Rather than downgrading her challenge, Bland verbally affirms her belief that Encinia does not have the right to make her exit her vehicle. This challenge is follow by Encinia's command: “Step out of the car.” In stark contrast to his previous two legitimacy claims, this third claim takes the form of a direct command. Brown and Levinson explain that imperatives may occur under several social conditions, including where S[peakers]'s want to satisfy H[earer]'s face is small… because S[peaker] is powerful and does not fear retaliation or noncooperation from H[earer] (1987: 97). The communicative environment between Encinia and Bland in this turn falls neatly into this characterization. After twice having his authority challenged by Bland, Encinia resorts to a linguistic construction that unambiguously conveys his greater level of power in the interaction.

The claim-response pattern continues over the following six turns. Encinia repeats “Step out of the car” in his next two turns, in increasingly elevated tones. Bland counters with repeated rejection of Encinia's legitimacy: “You do not have the right.” Here, Bland moves beyond her refusal to acquiesce, instead challenging the very basis of Encinia's orders. Following these repeated and unequivocal rejections of his legitimacy, Encinia proceeds to add a threat to his command: “I do have the right, now step out or I will remove you.” As in previous lines, here Encinia linguistically escalates his command. In this case, this is accomplished through the use of an explicit reference to his legitimacy (“I do have the right”) and a threat (or “I will remove you”). This is followed closely by “I'm giving you a lawful order,” a reference by Encinia to his institutional authority that will be addressed in greater depth in the following section. Consistent with the dialogic approach, in each successive turn Encinia invariably revises his claim to legitimacy. However, rather than weakening his claim or accommodating to Bland's objections, Encinia strengthens his claim with each line of dialogue. In doing so, Encinia contributes to the procedurally unjust nature of the encounter.

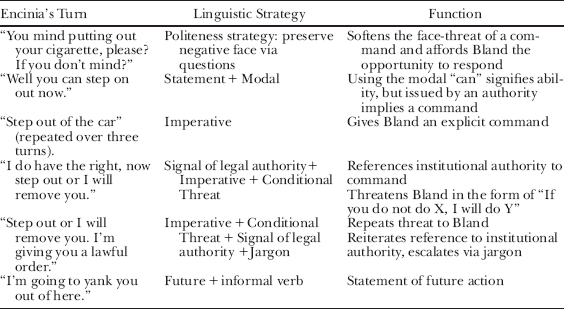

Interestingly, toward the end of the exchange Encinia asserts “I'm going to yank you out of here.” This is the first instance of Encinia using an informal verb in his attempt to convince Bland to exit her vehicle. Encinia's use of the word “yank” suggests that he has lost a degree of professionalism in the interaction. This pattern is consistent with a study in which researchers investigated command patterns preceding violent police-citizen encounters. In analyzing recorded interactions the researchers found a consistent pattern in the types of commands issued by an officer at the beginning of an interaction “which is followed by increasingly erratic command dialogue patterns, seemingly precedent to the violent event between the officer and the citizen” (Reference VandermayVandermay et al. 2008: 150). A similar pattern is evident in Encinia and Bland's interaction. With each subsequent turn, Encinia intensifies his claim in response to Bland's refusal to accept his directives. The escalated nature of Encinia's claims over Bland is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Linguistic Escalation of Encinia's Claims to Legitimacy

As Encinia attempts to make Bland exit her vehicle he linguistically escalates each successive conversational turn in response to her challenges. After asking her to put out her cigarette, each of Encinia's turns have the same underlying purpose (to make Bland exit), although the form of these attempts shifts considerably. While Encinia opens using a request in question form, he quickly progresses to commands. In the end, his revised claims include threats and direct references to his legitimacy as a representative of the state. This linguistic escalation reflects the evolution of procedural justice of the encounter. Whereas Encinia's opening utterances are respectful (at least on the surface) as the analysis above has demonstrated, this respect quickly dissolves. The escalation of Encinia's requests and commands is one of the linguistic features that most clearly reflects Encinia's revised claims to legitimacy in his attempts to maintain control of Bland.

Jargon and Epistemics

Within institutional discourse, much of the research has focused on the asymmetries in knowledge and power when a lay-person enters into the domain of knowledge held by that professional (Reference AgarAgar 1985; Reference Heritage and SilvermanHeritage 1997; Reference MatoesianMatoesian 1999). For instance, in Philips’ (1982) study of law students, she finds that budding lawyers use jargon in everyday conversation to create camaraderie and membership as lawyers, but also effectively alienate those who are not members of that community of practice. This section will examine the use of two specific points of jargon in Bland's traffic stop: “failure to signal” and “lawful order.” We argue that Bland's adoption of “failure to signal” is a method of challenging Encinia's legitimacy, while Encinia's use of “lawful order” is his attempt to maintain it.

In this section, we will synthesize the speakers’ use of jargon with epistemic references. Epistemics, or knowledge in interaction, has been thoroughly researched in discourse analysis and conversation analysis. In Reference Heritage, Sidnell and StiversHeritage's (2013), work on epistemics and perspectives in conversation analysis, he writes, that researchers “[focus] on the knowledge claims that interactants assert, contest and defend in and through turns-at-talk and sequences of interaction” (370). Furthermore, Reference van Dijkvan Dijk (2014) discusses knowledge and interaction and states that “[scholars have] begun to explore which speakers may express what kind of knowledge to what kind of recipients, and how entitlements, responsibility, and imbalances and norms influence such talk” (9).

Failure to Signal

Consider the phrase “failure” or “failed to signal” as a term used by law enforcement professionals to categorize the specific traffic violation being committed. This term was introduced by Encinia in the first line of dialogue as an explanation for why he was pulling over Bland:

(4) Encinia: Hello, ma'am

Bland: Hi

Encinia: We're the Texas Highway Patrol the reason for your stop is you didn't fail- you failed to signal the lane change.

From the first line of dialogue, Encinia uses jargon to explain the reason for the stop. By choosing to use a specialized law enforcement term to describe Bland's traffic violation, Encinia highlights his institutionally based power. His claim to intuitional authority is further reinforced by his use of the first-person plural pronoun in “We're the Texas Highway Patrol.” However, in attempting to reinforce his own legal authority, Encinia appears to unintentionally undermine himself through his incorrect use of the term: “you didn't fail.” This mistake in jargon usage is quickly followed by a self-correction (“you failed to signal”) in which Encinia switches to the appropriate form of the term. By choosing to introduce the jargon and then using it incorrectly, Encinia undermines his own legitimacy from the opening line of interaction.

Subsequently, there were nine instances “failure to signal” all of which were uttered by Bland, as in the following example:

(5) Encinia: Get out of the car!

Bland: For a failure to signal? You're doing all of this for a failure to signal?

Encinia: Get over there.

Bland: Right. Yeah, yeah let's take this to court, let's do this.

Encinia: Go ahead.

Bland: For a failure to signal? Yup, for a failure to signal!

The term “failure to signal” is very rare outside of the institutional setting. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) contains over 450 million words compiled from mainstream American sources, written and spoken, from 1990 to 2016 (Reference DaviesDavies 2008). Within this corpus there were only seven documented instances of the phrase “failure to signal,” four of which were news articles containing the transcript of the Sandra Bland arrest. The remaining three instances were of news sources documenting the phenomenon of African Americans getting pulled over for a “failure to signal,” such as the Aaron Campbell case (Reference SalamoneSalamone 1998). Of the phrase “failed to signal,” there were three results: a news source containing the Sandra Bland arrest transcript in 2015, another news source documenting an arrest made for an individual who failed to signal a turn, and a third instance within a novel. The term “failure to signal” is therefore an infrequent term in everyday communication.

Although the term is originally introduced by Encinia, Bland promptly integrates this term into her own speech. By repeating the legal jargon “failure to signal” and embedding it after the phrase “You're doing all of this,” she indicates that she knows that this is an atypical response for a traffic violation. In this excerpt, she articulates that she is knowledgeable about the interactional norms of a traffic violation and adopts Encinia's professional jargon to reveal her understanding of institutional norms. Moreover, Bland signals that she understands the workings of the judicial system more broadly, as she asserts “let's take this to court.” This line demonstrates Bland's grasp of the resources available to her within the judicial system. Additionally, this is yet another indication to Encinia that Bland considers his actions to be illegitimate since she believes a higher authority (the court) would find her to be in the right.

Further, Bland shows that she understands the extent of Encinia's legal influence over her:

(6) Encinia: Get off the phone!

Bland: I'm not on the phone. I have a right to record.

Encinia: (Overlapping) Put your phone down!

Bland: (Overlapping)… my property

Encinia: Put your phone down.

Bland: (Overlapping) This is my property.

Encinia offers two commands: “get off the phone and put your phone down.” Bland answers the first command by indicating that she is not making a phone call. Instead, she is recording the interaction, and states “I have a right to record. This is my property.” In this line, Bland signals her understanding of larger interactional and institutional norms of her rights as a U.S citizen. Moreover, Bland once again challenges Encinia's right to command her and demonstrates that she is well-versed as to the limits of his authority. Encinia does not accept her knowledge within the interaction, but instead responds with yet another command for her to put her phone down.

Bland's incorporation of the term “failure to signal” and her epistemological references to her rights in the interaction signal that she is knowledgeable about law enforcement procedures, her rights, and the judicial system. She clearly conveys her understanding of the norms and requirements of the interaction. Moreover, by adopting “failure to signal” and using it both repeatedly and incredulously, Bland signals that she does not agree with Encinia's professional assessment of this traffic violation. Bland's use of “failure to signal,” combined with epistemic references to the workings of the criminal justice system are another indication to Encinia that she does not accept either his decision, his status, or his legitimacy.

A Lawful Order

Another piece of jargon woven into the interaction is “lawful order.” In the context of law enforcement, a lawful order is an instruction from an officer that a citizen is legally bound to obey and does not require the citizen to break the law to obey (Reference KerrKerr 2015). This term has a more serious connotation in the context of the military, where disobeying a lawful order from a superior is basis for a court martial (Manual for Courts-Martial 2012). Given the parallels between the military and law enforcement, it is possible that from both an officer and a citizen's perspective the use of “lawful order” will evoke images of grave legal consequences. In the transcript of Bland's arrest, “lawful order” was uttered four times by Encinia in the context of attempting to make Bland follow his orders. Encinia uses the phrase “lawful order” as a legitimizing tool to illustrate that he is in complete control in the interaction and will exercise such authority to ensure Bland's compliance.

The first instance of this term was in the context of ordering Bland to exit her vehicle (see Table 2). Subsequently, the term was used as Encinia attempted to make Bland to turn around in order for him to put handcuffs on her wrists. In each of these instances, however, Bland does not acknowledge the order, nor does she give any indication that she is aware of what constitutes a lawful order:

(7) Bland: I am getting removed for a failure to signal?

Encinia: (Overlapping) Step out or I will remove you. I'm giving you a lawful order. (Pause). Get out of the car now or I'm going to remove you.

(8) Encinia: (Overlapping) I said get out of the car

Bland: Why am I being apprehended? You just opened my-

Encinia: I'm giving you a lawful order.

(9) Bland: Why am I being arrested?

Encinia: Turn around

Bland: Why can't you tell me…

Encinia: (Overlapping) I'm giving you a lawful order. I will tell you.

Bland: (Overlapping) Why am I being arrested?

Encinia: Turn around!

Bland: Why won't you tell me that part?

Encinia: I'm giving you a lawful order. Turn around…

The term “lawful order” is not as infrequent as “failure to signal” in colloquial American English as categorized by the COCA Corpus (Reference DaviesDavies 2008). However, all 21 instances of the term in the corpus were either direct quotes of a law enforcement official or paraphrasing what a law enforcement official had said or done. This suggests that this term is highly centralized to members of that community of practice.

What purpose does Encinia's use of this specialized term serve in the context of Bland's traffic stop? Because the term “lawful order” appears to be a lexical item that is not typically used, nor understood, outside of the law enforcement profession, Encinia's use of the term invokes his authority as a member of law enforcement. By characterizing his directives as “lawful orders,” Encinia places the source of his legitimacy with the state and conveys to Bland that, as a representative of the state, his commands do indeed require her compliance. This phrase therefore serves as silencing tool because it signals that Encinia is the legal authority and thus has the upper hand in the epistemological rights of the interaction overall. The repeated use of this term is another strategy through which Encinia makes a strong legitimacy claim, one that has been revised and strengthened several times over the course of the interaction as a result of Bland's challenges.

Further, the formulation and placement of this term suggest that Encinia may have used the term purposefully, either to avoid answering Bland's questions or as an answer in itself. As demonstrated in the excerpts above, Encinia formulates each utterance in which this term is used in the same way (“I'm giving you a lawful order”) and each is placed directly after a question asked by Bland. Instead of addressing Bland's concerns, Encinia's responses further emphasize his control over the situation by demonstrating that he is not obligated to respond with an explanation. In this way, Encinia's use of “lawful order” is consistent with a revised claim to legitimacy that maintains his right to authority, rather than accommodating to Bland's concerns.

In sum, law enforcement jargon and epistemics are used by both speakers in this interaction to strengthen their respective claims. Although Bland was not a law enforcement officer, and therefore had less access to the rights of knowledge in the legal domain, she nevertheless adopts “failure to signal” as well as references to her rights and resources in the judicial system. In particular, we consider Bland's use of jargon to be a linguistic strategy that signals to Encinia that she rejects his claims to legitimacy. However, Encinia's use of the term “lawful order” is a strong and unequivocal message to Bland that Encinia will only strengthen his claims to authority, rather than back down in the face of her intensified challenges.

Discussion

This linguistic analysis is an early effort to address how legitimacy is negotiated on an interactional level between a citizen and a law enforcement officer. Using the tools of interactional sociolinguistics and conversation analysis, this study has presented a nuanced view of legitimacy as it is contested on a turn-by-turn basis between two individuals: Sandra Bland and Officer Brian Encinia. Our analysis proceeded within the framework of Bottoms and Tankebe's dialogic approach to legitimacy, which conceptualizes legitimacy as “a perpetual discussion, in which the content of power-holders’ later claims will be affected by the nature of the audience response” (2012: 129). We have explored how Bland and Encinia's linguistic choices reveal the continual process through which claims to legitimacy evolved over the course of the traffic stop. We argue that at the center of this rapidly escalating encounter lies Encinia's contested legitimacy as an institutional representative with the power to issue commands.

This analysis has highlighted the use of questions, requests, commands, jargon, and epistemics by each speaker and how each feature reflects the speakers’ adherence to their legitimacy beliefs. By adopting a conversation analytic approach, we have demonstrated that Encinia's revised claims to legitimacy are at no point downgraded; at each stage Encinia intensifies his right to issue commands. We conclude that the acute escalation of the encounter was due in large part to each speaker's steadfast adherence to their respective beliefs about Encinia's legitimacy. The events of Bland's traffic stop therefore exemplify the consequences of audience legitimacy and power-holder legitimacy incongruence, in which “the power-holder has a secure view of his legitimacy that is not shared by the audience” (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms and TankebeTankebe 2012: 159). Although, we are cautious to make causal statements, we argue that one key element to understanding what went wrong in Bland's traffic stop is this lack of alignment between audience legitimacy and power-holder legitimacy.

In contextualizing the contributions of our study, we return to the questions posed at the outset of this article. First, can the dialogic legitimacy framework be used to understand the dynamics of individual police-citizen interactions? Although Reference Bottoms and TankebeBottoms and Tankebe (2012) engage in a thorough discussion of power-holder and audience legitimacy, they provide few concrete examples of how the dialogic framework works in practice or can be used to understand real-life situations. Using discourse analysis and dialogic legitimacy to understand Sandra Bland's arrest we show how legitimacy evolves on a turn-by-turn basis in an actual police-citizen interaction. Moreover, we demonstrate how the dialogic legitimacy framework is a useful lens through which to view problematic interpersonal encounters, especially those between power-holder and audience. Additionally, our analysis explicitly engages with Encinia's concept of his own legitimacy as a power-holder, an aspect of legitimacy thus far largely neglected in the criminal justice literature. Our analysis confirms that the ways in which power-holders’ authority evolve over the course of an interaction has implications for citizens’ reactions and perceptions of legitimacy. In this analysis, we have therefore provided concrete examples of concepts from the dialogic legitimacy literature that have thus far only been abstractly described and we demonstrate how they apply to an actual police-citizen interaction.

Moreover, the conclusions of our analysis can speak to another under-addressed question: how is procedural justice manifested linguistically? In examining the minute interactional details in Bland's traffic stop we shed light on the linguistic mechanics of procedural justice and legitimacy dialogue. Of the linguistic features, we examine in this study, the most substantial for procedural justice theory is how Encinia formulates commands and requests. We found that as the interaction devolved, Encinia's language shifts in accordance with the politeness forms outlined in Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson's (1987) politeness theory. While Encinia begins the interaction using linguistic forms established in politeness theory, he drops these as the encounter progresses. This observation suggests there may be an intersection between procedural justice, legitimacy, and politeness theory that can be explored in future research. For instance, insights from politeness theory could help create a nuanced description of police displays of dignity and respect that has thus far been elusive in the operationalization of procedural justice. In this way, approaching procedural justice's quality of treatment concept from an interdisciplinary stance may help move forward the theory and implementation of procedural justice theory.

Interestingly, our analysis found that an early display of respect by Encinia did not prevent Bland from challenging his legitimacy. This suggests that Bland's underlying beliefs, likely a result of her prior direct and vicarious experiences with police, shaped her perception of Encinia's actions. This finding reinforces previous research on the importance of prior experiences in shaping police-citizen encounters (Levin & Reference Levin and ThomasThomas 1997; Reference RosenbaumRosenbaum et al. 2005; Reference SkoganSkogan 2012). Experimental work in procedural justice has also found that one encounter with police may be insufficient to alter a person's more general perception of law enforcement, even if that interaction is a positive one (Reference Lowrey, Maguire and BennettLowrey, Maguire, & Bennett, 2016; Reference SahinSahin, 2014). The evidence therefore suggests that citizens’ attitudes toward police are the result of multiple interactions over a span of time. Especially within the context of racialized police-citizen tensions, in is unclear whether alternative language choices by Encinia in this isolated encounter could have prevented the escalation that resulted.

Our conclusion that respect alone was insufficient to deescalate the encounter may speak to the relative importance of quality of treatment and quality of decision making in shaping citizen perceptions of police. While Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-MarkelEpp et al. (2014) argue that the perceived fairness of a stop, particularly an investigative stop, weighs more in citizen's evaluations than does respectful treatment, other studies have found the opposite (see Jonathan-Zamir et al. 2014 for a summary). As Epp et al. conclude, our analysis found that the veneer of respect was insufficient to ensure a positive outcome in Bland's traffic stop, although we stress that causal statements cannot be drawn from our qualitative analysis. Nevertheless, this conclusion adds weight to the call that law enforcement's implementation of procedural justice must constitute more than simply a change in superficial treatment (Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-MarkelEpp et al. 2014). A more fundamental shift in attitude and treatment is needed.

This analysis of Sandra Bland's traffic stop contributes to the growing synthesis of communication and policing studies. For example, in our analysis we argue that Encinia's lack of willingness to address Bland's questions reflected his desire to retain control of the interaction. This conclusion is consistent with recent findings from a large-scale project examining military cross-cultural communication and police-citizen encounters. As part of their analysis, the researchers found that refusing to acknowledge a citizen's questions and concerns often led to use of force:

…when officers ignored the questions or other actions that civilians posed they were much more likely to use force. By contrast, where officers responded to or simply acknowledged civilian actions, civilians were much more likely to cooperate and officers were much more likely to complete their projects cooperatively. All of this suggests that … unilaterally asserting authority generates more problems than it solves (Reference PrecodaPrecoda 2013: 13–14).

Officers’ attempts to assert authority, without pausing to address citizen concerns, were found to escalate the encounter. These findings are in line with our determination that Encinia's failure to properly respond to Bland's questions and concerns is at the heart of the legitimacy disconnect in this interaction. Thus, attending to citizen voice and participation in an encounter is a communicative strategy that has gained support from a variety of sources and which can be integrated into police training.

From a methodological standpoint, we introduced discourse analysis into the study of police legitimacy and procedural justice. Well-established in the linguistics literature, discourse analysis is relatively a new method of inquiry in criminal justice, especially the scholarship on policing. Although a large number of studies have examined police-citizen interactions and perceptions of police using survey, interview, and even experimental methodologies, this type of data does not speak to the issue of how legitimacy and procedural justice are manifested in an interaction. Which communication strategies foster police legitimacy? How is respect conveyed from officer to citizen, and from citizen to officer? These questions have been largely unaddressed in the criminal justice literature. Discourse analysis, with its detailed approach to word choice and dialogue construction, is a method well-suited to addressing these gaps and should be used to a greater extent in future studies.

Nonetheless, the present analysis is a case study and therefore has weaknesses that should be noted. A primary limitation of case studies is the degree to which their findings are generalizable, and our conclusions are no exception. We do not claim that our findings could be generalized to different instances of police escalation of force. Further, we are limited in our ability to make causal claims as to the effect of Bland's language on power-holder legitimacy or the consequences of Encinia's linguistic choices on audience legitimacy. However, we believe that the dialogic nature of legitimacy is best examined within a case study approach. The back-and-forth process of claim and response outlined by the dialogic approach necessitates a precise focus on the nature of conversational turns. As such, this linguistic analysis of the dialogue in Sandra Bland's traffic stop is a first step toward improving our understanding of how legitimacy is negotiated as an evolving, dialogic process.

Our analysis focused in-depth on a single police-citizen encounter. Future research in the study of legitimacy and police-citizen interactions should build upon the present analysis to include a greater number of interactions under a wider array of circumstances. With the expansion of police body-camera programs, more and more interactions are now being recorded, providing researchers with a wealth of data to improve our understanding of the negotiation of legitimacy. In particular, a replication of our analysis with the dialogue from an interaction in which the officer successfully de-escalated the encounter would add to our knowledge of how claims to legitimacy can be successfully revised, rather than merely which tactics to avoid. Such an analysis would provide an interesting contrast to the present analysis, especially as it relates to the evolving character of legitimacy. Moreover, future studies might apply our method to the dialogue of officers with different policing styles. Encinia appears to fall into Reference MuirMuir's (1977) “enforcer” policing style, evidenced by his “total reliance on the legality of his orders” (Tankebe, personal communication). Distinctions between Muir's four policing styles (professional, enforcer, reciprocator, and avoider) are closely related to conceptions of power-holder legitimacy (Bottoms & Reference Bottoms, Tankebe, Tankebe and LeiblingTankebe 2014). Understanding dialogic legitimacy within the context of individual policing styles may be instructive in identifying effective communication strategies and responses the public's demand for legitimation narratives.

Conclusion

The transcript of Sandra Bland's traffic stop provides a glimpse into a police-citizen encounter that escalated rapidly to a physical confrontation. At a time when the police were under public scrutiny for their use of force against unarmed African Americans, Sandra Bland's case gained widespread notoriety. Many members of the public and the press have speculated as to why this encounter progressed as it did. In analyzing the linguistic patterns of each speaker, we have highlighted the central importance of legitimacy in the rapid unravelling of the interaction and we argue that there was a disconnect between audience and power-holder legitimacy at a fundamental level. At the same time, the conclusions of this analysis add to the body of work recommending increased communication training for law enforcement officers, particularly training that incorporates the principles of procedural justice. Together, these future avenues of research can contribute to improving the relationship between law enforcement and the community.