INTRODUCTION

The link between public participation and legitimacy is a core tenet of democratic theory (Fishkin Reference Fishkin1991, Reference Fishkin2009; Landemore Reference Landemore2020). Political outcomes that reflect, or are perceived to reflect, popular will expressed through fair, free, and open participation are commonly viewed as more legitimate than those decided on behind closed doors or imposed by sheer power with minimal or no public input. Constitution making is no exception. When the people have been consulted about a new constitution, conventional wisdom has it, they are more likely to see the constitution as being a legitimate national charter (Hart Reference Hart2003). Footnote 1

A broad popular assessment of legitimacy, often understood as “diffuse support” (Easton Reference Easton1975), is vital for a new constitution as direct enforcement may be difficult and the power of the constitution to command voluntary obedience from institutions and individuals alike is crucial to allow the constitution to fulfill its major functions. Optimizing the starting legitimacy of a constitution is thus one of the most important aspects of any constitution-making process. Consequently, the current accepted wisdom regarding the design of constitution-making processes is that public participation (of some kind) is a necessity.

Virtually all successful constitutional renewal efforts in the last quarter century have involved wide public participation. Often this involves some form of participation in the convening or drafting stages (Eisenstadt, LeVan, and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017), and/or participation through ratifying referenda (Elkins and Hudson Reference Elkins, Hudson, Landau and Lerner2019). This has been the case even in instances where the constitution-making process has included the heavy involvement of international advisors and mediators (see, for example, Iraq in 2005, South Sudan in 2011, and Nepal in 2015). Footnote 2 In recent decades, the trend has been to create more space for public participation in the earlier (upstream) stages of the constitution-making process (Elster Reference Elster1995). Precedent-setting instances of upstream participation of this type took place in Brazil in 1987–88, South Africa in 1993–96, Iceland in 2011, and even at the subnational and municipal level (for example, there was extensive solicitation of public input in the constitutional transformation of Mexico City). In short, as Coel Kirkby and Christina Murray (Reference Kirkby, Murray, Ndulo and Gazibo2016, 87) emphatically describe this common view, “today it is inconceivable that a government would attempt to draft a new constitution without at least a nominal commitment to a process in which the public is consulted.” The chief apparent virtues of public participation include creating a sense of public ownership, educating the public, and, most importantly, legitimizing the new constitution (Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Cottrell, Ghai and Regan2011). It is this last point that we particularly wish to interrogate in this article.

Established and commonly practiced as the conventional wisdom regarding participation may be, the scholarship on the topic to this point is largely missing several key elements: (1) an individual-level mechanism that can explain why participation would lead an individual to believe that the constitution is legitimate (or at least ought to be supported); (2) a societal-level mechanism that can explain the views of non-participants (for example, why merely hearing about participation would increase legitimacy); and (3) an account of how these effects may change over time.

A straightforward explanation might suggest that the people are more likely to view the constitution as legitimate if it accurately reflects their views or has been influenced by popular input. However, recent empirical research has demonstrated that few constitutions actually meet these conditions. To begin with, comparative analyses suggest that, in most cases, the link between people’s values and the values enshrined in their respective polity’s constitution is weak and, at times, non-existent (Versteeg Reference Versteeg2014). More importantly, public participation rarely has a significant impact on the constitutional text and seems to matter mainly in cases where political parties are relatively weak or uninvolved (and so are less likely to strategically filter public preferences that do not serve their interests) (Hudson Reference Hudson2021b). If participation matters little in affecting actual outcomes and if, more often than not, the people’s choices are made irrelevant in constitution-making processes, then how does their participation legitimate the constitution? Should we not rather find the opposite—that these ineffective opportunities for public input reduce support for the constitution?

In this article, we seek to experimentally model aspects of the constitution-making process in order to test individual and societal mechanisms through which public support is generated. We argue that the identification of these mechanisms may facilitate further research on the longer-term dynamics, but we do not pursue that here. We begin by outlining and critically evaluating the pertinent scholarship concerning public participation as a legitimacy-enhancing practice in constitution-making processes. We highlight the dissonance between the widely held belief that participation is an essential part of modern constitution making and the dearth of research on its effects. Furthermore, we focus on a particular puzzle: how are we to explain the legitimacy-enhancing function often attributed to participation while research suggests that the actual impact of such participation on constitutional outcomes is far lower than assumed and, at times, even non-existent.

To address this puzzle, we introduce in the article’s second section the results of two original recontact surveys that we conducted in six countries during 2021. These surveys were designed to evaluate two main dimensions of participation as a support-generating act: (1) a micro-foundational mechanism whereby support for the constitution is enhanced by virtue of individual participation and (2) a broader, societal mechanism whereby support depends upon public perceptions of fairness, openness, and transparency in constitution-making processes. We then turn to discuss the apparent merits and potential limitations of drawing on an experimental method such as the one we deploy to study the effect of public participation on support for the constitution. Taken as a whole, our two-stage study suggests that the act of participating in itself has little effect on public support but that the bigger picture of a fair process can have significant and potentially long-lasting positive effects. This suggests that, under certain conditions, participation can engender public support for a constitution regardless of the extent to which it has an impact on the constitutional text and that the appearance of a fair process is the link between participation and legitimacy.

PROBLEM AND THEORY

In his writings on the legitimacy of the American constitution, Richard Fallon (Reference Fallon2005) makes a vital distinction between the different possible conceptions of legitimacy in the context of constitutional law, dividing the larger concept into legal, sociological, and moral dimensions. This echoes in large part David Beetham’s (Reference Beetham1991, 3–7) description of the distinct understandings of legitimacy developed in different academic disciplines as lawyers equate legitimacy with “legal validity,” philosophers with “moral justifiability,” while social scientists have reduced legitimacy to “belief in legitimacy.” Our interest here is primarily in this “belief in legitimacy” that Fallon calls sociological legitimacy. This social phenomenon is realized when the relevant public regards a regime, governmental institution, or official decision “as justified, appropriate, or otherwise deserving of support for reasons beyond fear of sanctions or mere hope for reward” (Fallon Reference Fallon2005, 1795).

The conventional wisdom in contemporary constitution-making processes worldwide is that, in order for a new constitution to achieve sociological legitimacy (and, potentially, also moral legitimacy), it must be created in a participatory process. Such participation in constitution making increasingly involves considerable public input in the convening or drafting stages (including through mechanisms approaching crowdsourcing) and most commonly through ratifying referenda. As a broad matter, in a book that provides one of the best overviews of the phenomenon, Todd Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan, and Tofigh Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017, 3) define participatory constitution making as “transparent, substantive, and often direct citizen involvement.” The activities included in participatory constitution-making processes are diverse and have included public education programs, public meetings, petitions, parades, referendums, and (of greatest interest to us) written submissions of suggestions for constitutional content.

Taken as a whole, these measures reflect wide acceptance among constitution makers and scholars alike that, as expressed by Vivien Hart (Reference Hart2003, 12), “process has joined outcome as a necessary criterion for legitimating a new constitution: how the constitution is made, as well as what it says, matters” (see also Ginsburg, Elkins, and Blount Reference Ginsburg, Elkins and Blount2009). The significance of public participation in constitution making and the legitimacy it helps create is further highlighted as constitutions may ultimately fail to deliver on most, let alone all, of their promises.

As common as public participation practices are, there has been very little comparative empirical research on the sociological legitimacy of new constitutions and the role of public participation in generating it. While both “upstream” and “downstream” participation (to use Jon Elster’s (Reference Elster1995) metaphor) could have important legitimizing effects, the mechanisms and justifications for these various forms of participation could be different. Footnote 3 In the case of the former, recent research has shown that upstream participation is unlikely to affect the content of the constitution (Hudson Reference Hudson2021a, Reference Hudson2021b). In the case of downstream participation, despite research that has suggested that individuals can make reasonably accurate assessments of their interests in referenda (Lupia Reference Lupia1994), Jeffrey Lenowitz (Reference Lenowitz2021) has argued that the inability of voters to fully understand the constitution undercuts any claim that they have exercised popular sovereignty in these votes. Thus, while downstream participation in the form of ratifying referenda does not suffer from the lack of efficacy that undermines upstream participation, its claims to support legitimacy are similarly suspect.

In one of the two existing studies that are perhaps most relevant to the questions we seek to address here, Devra Moehler (Reference Moehler2006, Reference Moehler2008) sought to establish the extent to which participation in the constitution-making process in Uganda affected participants’ views of the constitution and politics more generally. Crucially, Moehler found that participation did not increase perceptions of the legitimacy of the constitution. Yet while Moehler discusses the connection between participation and legitimacy in some depth, her survey of participants in the Ugandan constitution-making process only asked respondents to indicate their level of “support” for the constitution. While there are good reasons to suggest that mere support is only a partial measure of legitimacy, it may in fact be a reasonable approximation of the larger concept, and it is an approach we take on ourselves in the experimental work described below.

A second pertinent study conducted by Tofigh Maboudi and Ghazal Nadi (Reference Maboudi and Nadi2022) using data collected immediately after the adoption of a new constitution in Tunisia in 2014 shows that participants in the constitution-making process in that country were more likely to support the constitution than non-participants. Maboudi and Nadi included in their measure of participation a wide range of actions, including voting in the constituent assembly election and merely following the news as well as more rare and direct forms of participation—namely, working to influence the constitution (undertaken by 5 percent of respondents) and attending a meeting that addressed constitution drafting (6 percent of respondents). Nonetheless, they found that citizens who participated were more likely to say that the constitution expressed their values and to say that it effectively protects rights. These effects were stronger for people who participated more (that is, attended a meeting rather than just reading the news). Maboudi and Nadi then go on to suggest that the link between participation and legitimacy might be through an increase in citizens’ knowledge about the constitution. However, what may be missing from this important account, we argue, is the ability to identify the concrete causal effect of participation on legitimacy through control of who participates in the constitution-making process and to what exact extent, as well as the ability to accurately trace (at the individual participant level) the concrete effect (or lack thereof) of each participant’s input on the actual constitutional text adopted. In this sense, Maboudi and Nadi exhausted the explanatory value that was available from a survey, but the data did not allow for the isolation of the causal process.

To the extent that these works test the veracity of our intuitive sense of the relationship between participation and constitutional legitimacy, they highlight the importance of identifying and understanding the process through which participation (which may be ineffective, uninformed, or both) contributes to the formation of sociological legitimacy. It seems paradoxical that participation in a constitution-making process could legitimate the constitution without having a considerable (or at times any) impact on the constitution itself. A resolution to this paradox may be found by identifying the mechanism(s) through which public participation contributes to sociological legitimacy. While it seems likely that citizen participants will be unable to estimate the broader (non-)effects of aggregate participation, they should be able to determine whether or not their own contributions have been effective. Indeed, one very interested participant in the constitution-making process in South Africa in 1995 wrote a series of letters expressing his dissatisfaction on exactly this point (Hudson Reference Hudson2021b). This suggests that the mechanism through which participation contributes to legitimacy may be entirely separate from the effectiveness of participation.

Politicians, too, recognize the legitimating potential of participation. One of the members of South Africa’s Constitutional Assembly (Mohammed Valli Moosa) said in a speech in 1994 that “[t]he legitimacy of a constitution is in no small way influenced by the legitimacy of the process which produces it” (Parliament of South Africa 1994, 221). Another said in an interview that “[t]he South African public felt like they’d been part of the process, and therefore made the end product more legitimate” (quoted in Hudson Reference Hudson2021b, 67). It is interesting that—for both politicians and scholars—the link between participation and legitimacy is independent of any consideration of the extent to which participation was effectual.

A final consideration regarding the current prominent role of participation is the question of whether or not participatory processes produce better outcomes. One important outcome is the consolidation of democracy. Here, there is some evidence to suggest that participatory processes are predictive of higher levels of democracy in the years that follow (Eisenstadt, LeVan, and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017). Participation has also been found to increase the number of rights included in constitutions (Ginsburg, Elkins, and Blount Reference Ginsburg, Elkins and Blount2009) and to produce constitutions with more pro-democracy provisions (Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020). However, the qualities of participatory processes that produce these outcomes (largely relating to inclusion, deliberation, and consensus building) can also be cultivated in processes that utilize representation through elections (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2021).

In our view, there are at least two contending explanations for the psychological relationship between participation and legitimacy in the context of constitution making regardless of the actual impact of participation on the final constitutional text. One relies on the experiences of the individuals who participate in the constitution-making process, and the other on the larger perception of fairness and openness of the constitution-making process that the drafters create. The first (individual or micro-foundational) mechanism advances through what we might call the expressive path. Here, we build on the arguments that various scholars have used when addressing the basic paradox concerning the rationality of voting identified by Anthony Downs (Reference Downs1957). William Riker and Peter Ordeshook (Reference Riker and Ordeshook1968) resolved the apparent irrationality of voting by adding a consideration of an individual’s beliefs about civic duty. John Ferejohn and Morris Fiorina (Reference Ferejohn and Fiorina1974, 526) summarized the substantive meaning of this civic duty in more expressive terms, describing it as “the psychic pleasure of pulling the lever.” This insight was taken further in Bart Engelen’s (Reference Engelen2006, 435) work on the “expressive rationality” of voting. Engelen suggests that “[c]itizens who are motivated purely expressively will vote if they are committed to democracy or to a particular political candidate or party. If they feel a strong sense of duty to vote, they will vote, without paying much attention to the consequences of this decision.”

We are not especially concerned with the rationality of participation (although we assume that the calculation could follow the general lines of the work on voting). However, the insight from the research on voting that is applicable here is the idea that the act of expressing a political preference is in some way satisfying regardless of the outcome. The leap that we would like to make from the literature on the rationality of voting is to suggest that these same feelings of “psychic pleasure” (Ferejohn and Fiorina Reference Ferejohn and Fiorina1974, 526), or “strong sense of duty” (Engelen Reference Engelen2006, 435), may also lead individuals to ascribe a higher level of legitimacy to the outcome of a democratic process in which they have participated than they otherwise would have. This also follows some recent experimental research on the legitimacy of political decision-making processes. Placing participation, personal involvement, and fairness in competition, Peter Esaiasson, Mikael Gilljam, and Mikael Persson (Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012) found that personal involvement (even through it is something as simple as voting) is the most important factor for generating legitimacy. Here, the expressive mechanism highlights the value derived from the very act of participation—the civic duty it entails—rather than its impact. Legitimacy here does not rely on the result of the process. It rests on the individual’s agency in voting and participating and is not conditioned on the participant’s being heard. To state this in the form of a testable hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The expressive value of participation leads individuals to view the outcome of a constitution-making process as legitimate, irrespective of the effect of that participation.

The second potential mechanism that may explain the effect of participation on legitimacy regardless of the outcome is broader in nature and focuses on perceptions of fairness, openness, and transparency and draws on the literature on procedural justice. In many areas of life that involve group decision-making, individuals regularly (consciously or unconsciously) evaluate their satisfaction with what happened based on the process that was used to arrive at a decision, not exclusively or even primarily on the merits of the decision itself. In a quotidian context, one might be content to dine with friends at a restaurant that one does not enjoy if the discussion that preceded the choice of location was conducted in a fair and open-minded manner. In a more complicated and weighty negotiation, perhaps the outcome would matter more than the process, but fair procedures have been shown to lead to higher levels of satisfaction and acceptance when the outcome would be independently viewed as being suboptimal (Thibaut and Walker Reference Thibaut and Walker1975; Lind and Tyler Reference Lind and Tyler1988). The foundational experimental work in the field that became known as procedural justice has been widely adapted in research on trial proceedings and criminal justice (Wemmers and Cyr Reference Wemmers and Cyr2006), environmental regulation (Lawrence, Daniels, and Stankey Reference Lawrence, Daniels and Stankey1997; Smith and McDonough Reference Smith and McDonough2001), and other fields of broad interest to social scientists.

Procedural justice has a clear potential application to constitution-making processes. As in other fields of human endeavor, both process and outcome matter. First, as we have established, a democratic (participatory) process is necessary to create a constitution that can be viewed as legitimate, at least by scholars (Hart Reference Hart2003; Colón-Ríos Reference Colón-Ríos2012). Research in this area has highlighted the importance of procedure as a determinant of legitimacy. Specifically, people are more likely to voluntarily comply with decisions or rules that have been developed through what they view as fair procedures (de Fine Licht et al. Reference De Fine Licht, Naurin, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014). Summarizing a wide range of relevant literature, Tom Tyler (Reference Tyler2006, 382) writes that “[t]his procedural justice effect on legitimacy is found to be widespread and robust and occurs in legal, political, and managerial settings.” In the case of constitution making, the implication is that a constitution could be viewed as legitimate because it was drafted in a fair process even if the content of the constitution produced unfair or otherwise suboptimal outcomes.

However, other research on procedural fairness highlights the fact that the outcome is not always irrelevant. As Ronald Cohen (Reference Cohen1985) has shown, participation that is not effective can produce a “frustration effect” that actually reduces the legitimacy of a decision in comparison with a non-participatory process. On this account, “ineffective” public participation could lead to reduced constitutional legitimacy. Working with survey data (rather than the experiments that have been more common in the research on procedural fairness), Stacy Ulbig (Reference Ulbig2008, 530) finds that, when citizens perceive that they have a strong voice but are not heard, they have lower trust in the political system than those who believe that they have little voice but are heard. (A finding much in sympathy with what Moehler (Reference Moehler2008) found in Uganda). Despite these notes of caution, observational data seem to suggest that the appearance of a participatory constitution-making process could go a long way in legitimating the constitution, regardless of the extent to which the constitution responded to public input. Therefore, our second hypothesis is a slight alteration of the first:

Hypothesis 2: The appearance of a fair procedure leads individuals to view the outcome of a constitution-making process as legitimate, irrespective of the real level of public influence.

Embedded within the procedural justice explanation are two related but distinct phenomena. One relates to the experience of participants, while the other can accommodate the experience of non-participants with knowledge of the process. Adaptations of theories of procedural justice in the field of criminal justice (and especially alternative dispute resolution) have highlighted the importance of the participants’ perceptions that they were heard. Specifically, research into how victims of crime are impacted by mediation or alternative dispute resolution has highlighted the fact that victims especially value being heard (Van Camp and Wemmers Reference Van Camp and Wemmers2013). More broadly, the concept of “voice” in procedural justice includes both the opportunity to express oneself and the interest that others show in what one has to say (Wemmers and Cyr Reference Wemmers and Cyr2006). For participants in a constitution-making process, both aspects of voice could be important in legitimating a new constitution. All citizens (both participants and non-participants) may value the opportunity to contribute something to the constitution making process. In this way, the mere invitation to participate could have a legitimating effect. For participants, the second aspect of voice could be important as they weigh the respect given to their contribution. While it may be rare to have evidence that one was heard at an individual level, it is likely that some aspects of the process may give greater or lesser evidence that citizen participants have been heard. For example, public statements made by drafters, or the level of transparency about the content of submissions from the public, could indicate that participants have been heard and that the process therefore was fair.

Beyond the participant-focused aspect of voice (and, specifically, being heard), the idea of procedural justice can also accommodate broader evaluations of the fairness of a constitution-making process. Here, the key points might involve the inclusive nature of the process (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019), opportunities for a citizen veto in the form of a ratifying referendum (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Blount Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Blount2008), or actions taken by the drafters to demonstrate their engagement with submissions from the public. These features of a constitution-making process realize the aspects of procedural justice that deal with neutrality and trust (Tyler Reference Tyler2000). Thus, while the specific concept of voice (as described above) could explain the attitudes of participants, broader systemic evaluations of the fairness of the process are applicable to any person who observes the constitution-making process.

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH

As plausible as these theoretical connections between participation and legitimacy may be, substantiation requires an empirical test of some kind. And, while survey data have been used in past studies to evaluate aspects of this relationship, there are some obvious limitations to drawing on such an approach. The most important of these is the potentially endogenous relationship between the personal characteristics that predict voluntary participation and those that might predict views regarding constitutional legitimacy. For example, it could be the case that people who are positively disposed to the constitution-making process both participate and have positive evaluations of constitutional legitimacy. In an experimental research design that uses randomization between control and treatment groups, the effects of potentially confounding variables such as these can be radically reduced.

However, the analytical clarity that an experiment offers is accompanied by a narrowing of the scope of enquiry. In our experimental work, we limited our analysis to tests of upstream participation. While participation in downstream mechanisms such as ratifying referenda is also common, our theory of legitimation appears to have stronger implications for upstream forms of participation where more substantive and nuanced opportunities for the expression of preferences are available. Moreover, we are skeptical of the legitimating effects of referendums in general. As Zachary Elkins and Alexander Hudson (Reference Elkins, Hudson, Landau and Lerner2019) have found, the vast majority of referendums to ratify new constitutions have passed, often with low turnout, and have taken place in countries with generally low democratic performance. In contrast, as Eisenstadt, LeVan, and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017, 40) have shown, participation in the earliest stages (convening) of the constitution-making process matters much more for democratic outcomes than participation in the later stages. Our experimental design thus focuses on the early stages of the constitution-making process, though our experimental vignettes described a process that would eventually culminate in a referendum.

We further sought to reduce the potential impacts of ongoing real-world constitutional issues by using constitutional texts and vignettes that are devoid of national references. While this reduces the degree to which the experiment simulates the reality of constitution making (with all its passions and high stakes), it allows us to focus the analysis on the few variables that we can reasonably control in an experimental setting. Working with these limitations in mind, we fielded two survey experiments that were each delivered in two waves. The experiments involved presenting participants with some information about a fictional constitution-making process in which they were invited to participate in the first wave, including either a full constitutional text (hereinafter Full Text Experiment) or a selection of articles from the proposed constitution (hereinafter Selected Articles Experiment). Footnote 4 In the second wave of each experiment, we presented respondents with a revision of the constitutional text they had seen in the first wave. We varied a number of the aspects of the information and tasks to create treatments that test the hypotheses described earlier.

As noted above, the most obvious difference between the two experiments was the amount of constitutional text with which respondents were presented. However, the length of the text varied with the specific questions we sought to answer. In the Selected Articles Experiment, we wanted to specifically and clearly manipulate the changes in the constitutional text between the two waves such that the changes would be obvious to our respondents. To that end, we only asked respondents to read five articles of the constitution. To mimic what takes place in real constitution-making processes, we invited written comments. But we also asked respondents in some treatment groups to indicate the direction in which they would like the text to be revised (for example, to explicitly permit or prohibit abortion) through a simple vote. This provided us with simple but important information about respondents’ preferences with regard to the constitutional text. In the Full Text Experiment, we sought to maintain the reality and complexity of a real-world constitution-making process and asked respondents to read a full (though short) constitution. Further mimicking the reality of participation in constitution-making processes, we asked respondents in some of the treatment groups to provide a short, written comment on the proposed text, with the implicit promise that this would be informative for revisions to the text. This longer experiment allowed us to test the more generalized effects of participatory constitution-making processes on the public at large.

Operationalization of the Concept of Legitimacy

To this point, we have spoken for the most part in terms of legitimacy. It is an important concept in the literature and has an intuitive value for both scholars and participants in constitution-making processes. However, its manifold meanings and manifestations make it difficult to measure. Following the example of other studies of the legitimacy of legal institutions, we operationalize the concept of constitutional legitimacy (in a sociological sense) through measures of support for the constitution. In their study of the public acceptance of disagreeable decisions at the US Supreme Court, James Gibson, Gregory Caldeira and Lester Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Kenyatta Spence2005) invoked David Easton’s (Reference Easton1967, 267) concept of “diffuse support” as a more empirically manageable equivalent of legitimacy. Easton (Reference Easton1975, 437, 444) contrasted diffuse support (“generalized attachment to political objects”) with specific support (satisfaction with the “outputs and performance of the political authorities”). It is this “generalized attachment” that new constitutions must develop in order to become established, and it is almost synonymous with the concept of legitimacy that the scholars we cited earlier in this article described. We find that the same approach of renaming the dependent variable taken by Gibson, Caldeira and Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Kenyatta Spence2005) is advantageous, principally because it allows us to pursue reasonable empirical tests without being encumbered with an overly capacious concept. Therefore, in these experiments, we measure legitimacy via a battery of questions that approximate diffuse support for the new constitution (see Appendix 1 for the full text of these questions).

Selected Articles Experiment: Design

While it is certainly the case that in a process of constitutional replacement the details of particular textual choices may be lost in the larger political and textual context, it is also the case that there are usually a few articles that receive a significant amount of attention in both elite negotiations and popular discussions. We recreated this aspect of constitution-making processes by asking respondents to read five articles of a hypothetical constitution and to give us their views of how these texts should be changed. In this Selected Articles Experiment, we sought to understand how the experience of participating in a constitution-making process would impact diffuse support for the constitution.

In recruiting a panel for this experiment, we sought to involve participants who would have some recent exposure to constitutional revisions. To that end, the Selected Articles Experiment included participants from Switzerland (425), Ireland (600), and Australia (600). Given the salience of foundational constitution questions in the United Kingdom (for example, Brexit) at the time that the survey was fielded (end of June 2021 to middle of November 2021), we also included a sizable sample from the United Kingdom (1,800). Participants were recruited by Qualtrics, using their panel providers in each country. We included quotas for age and gender to match census data in each country. Our Swiss sample was limited to residents of cantons where French and/or German were official languages, and we made the full survey (including the constitutional articles) available in either English, French, or Swiss German. As we had anticipated, there was some attrition between waves, and the second-wave sample included 240 from Australia, 243 from Ireland, 114 from Switzerland, and 553 from the United Kingdom, for a total of 1,150 valid responses.

At the beginning of the survey, we used a simple vignette to introduce the hypothetical constitution-making process and then invited participants to read the five articles (presented in a random order) and answer some questions about their support for the constitution and the constitution-making process (see Appendix 1 for the full text of the vignette and articles). Across all treatment groups, we provided an optional text entry box after the five articles that asked respondents to share their ideas about the constitution with the drafters. The vast majority (85 percent) of respondents wrote something (usually very short) in this box. Seeking to approximate real-life conditions without contaminating the experiment by touching on details of current debates in these countries, our five hypothetical constitutional articles covered a spectrum of political salience. They dealt with (1) the right to life; (2) the right to free expression; (3) legislative thresholds for the approval of taxation; (4) term limits for members of the legislature; and (5) the powers of an ombudsperson.

We expected that most respondents would have reasonably settled views on Themes 1, 2, and 3, some opinions on Theme 4, and less interest in Theme 5. We prepared three versions of each of the articles. In the first wave, every respondent saw the same basic version of the article. For example, the basic version of the article on the right to life simply stated: “Everyone has the right to life” without any further elaboration on what the limitations to that right might be. We also wrote versions of these articles that made clear choices in one of two directions. Continuing with the right to life example, our second version of this article clearly prohibited abortion, while the third version permitted abortion. The additional versions of the other articles made similar choices plain. In the second wave, each respondent saw a different version of the articles, with the specific text depending on their treatment group and their answers to questions in the first wave.

We randomly and evenly assigned the respondents into a control group and four treatment groups. The control group read the simple version of the articles in the first wave and read a randomly selected revision of those articles in the second wave. A “procedural fairness treatment” group also read the simple versions in the first wave and randomly selected revisions in the second wave. This “procedural fairness treatment” group read a vignette describing feedback from the public collected in the hypothetical process and how the drafters were using that information in their deliberations. The remaining three treatment groups had a further opportunity for participation in the first wave. Respondents in each of these groups were required to answer an additional question after reading each of the articles in the first wave, indicating the direction in which they would like to see the article changed in response to a clear question. For example, regarding the article on the right to life, we asked respondents to indicate whether they thought that the article should be more restrictive or more permissive with regard to abortion.

These three groups then differed in terms of their experience in the second wave. A “random effectiveness treatment” group saw a randomly selected revised text in the second wave. An “effective participation treatment” group saw revised articles in the second wave that all went in the same direction that they indicated they preferred in the first wave, while an “ineffective participation treatment” group saw revised articles in the second wave that all went in the opposite direction to their indicated preference in the first wave. The variation between these groups allows us to measure the difference that effective or ineffective participation makes in support for the constitution, while also covering the more likely possibility that one will “win” on some issues and “lose” on others.

While we collected data on a number of issues (including attachment to the existing constitution), the main outcome of interest for us was a battery of five questions on support for the constitution (these questions are included in Appendix 1). We estimated an item response theory (IRT) measure that combines this battery of questions and uses this as our primary outcome measure. Footnote 5 In addition, we considered a simple one-to-ten rating of support for the constitution as a stand-alone outcome measure. We also calculated the difference in the IRT measure of support for the constitution for each respondent across the two waves. Finally, since this experiment specifically sought to trigger an evaluation of the extent to which respondents found that their views were included in the constitutional text, we used a question on precisely this aspect of support for the constitution (scaled from one to five) as an additional outcome variable.

Selected Articles Experiment: Results

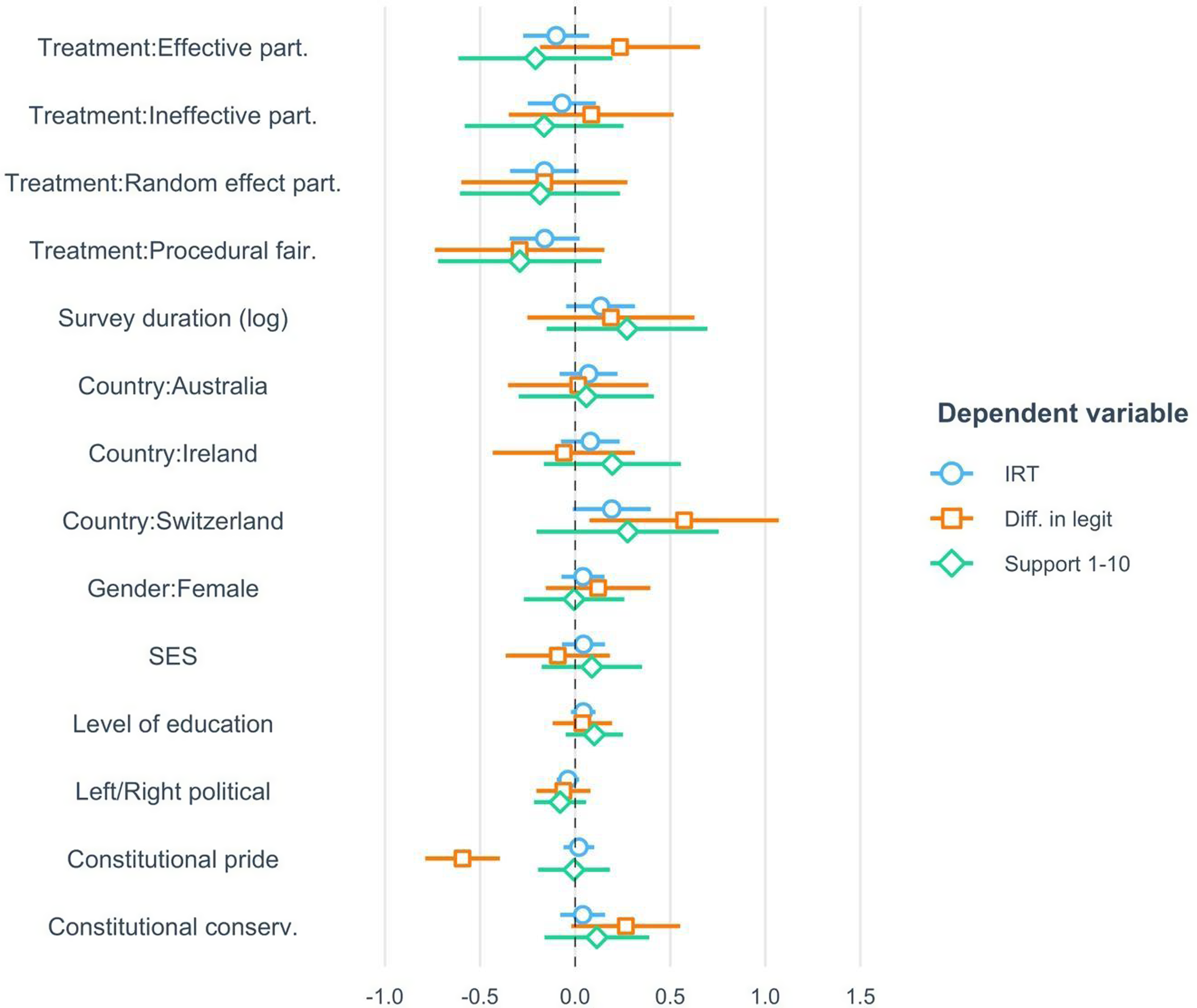

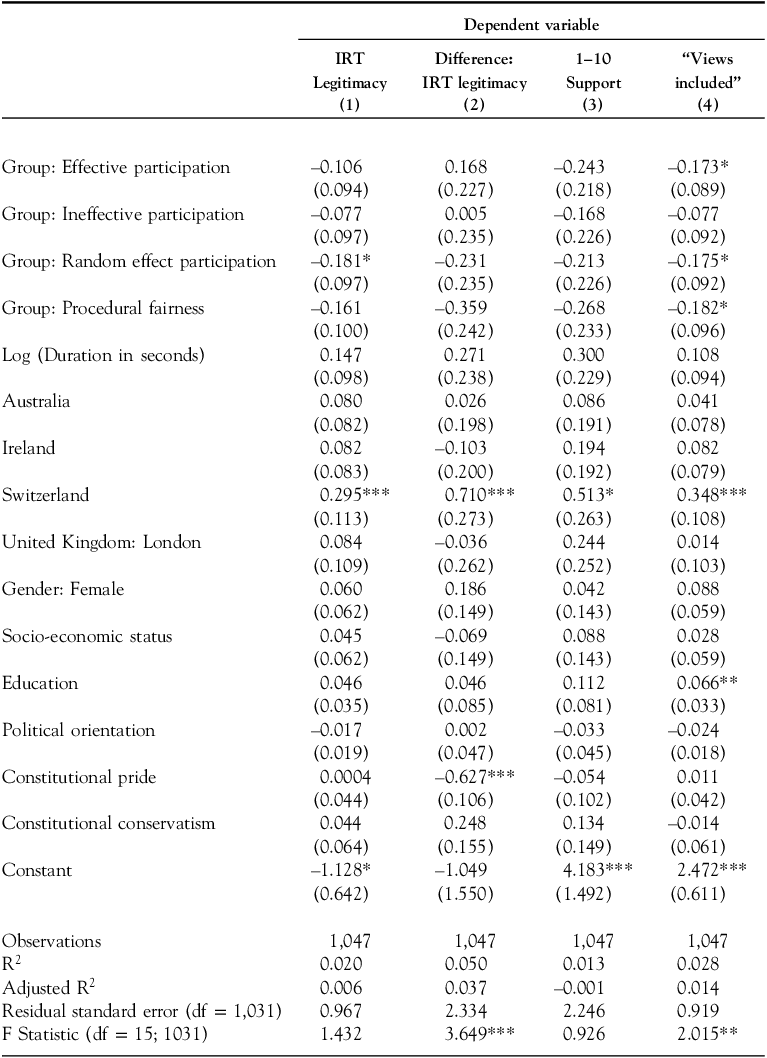

Coefficients for four ordinary least square (OLS) models with a number of relevant controls are presented in Table 1 in Appendix 2. In the main text, we graphically illustrate the regression analysis in Figure 1. In these models, we included controls for a number of geographical, political, and demographic characteristics that might have an impact on the respondents’ support for the constitution. A few require a brief explanatory note. “Political orientation” is a simple (self-reported) left-right orientation, where positive values are right leaning and negative values are left leaning. “Constitutional pride” is a measure of the extent to which respondents report pride in their constitution (whatever they interpret this to be). “Constitutional conservatism” is a measure of the respondent’s interest in changing their constitution, with response options ranging from “the constitution is basically fine as it is” (highest score) to “the constitution should be entirely rewritten and replaced” (lowest score). While we view these last two as controls for other attitudes that might confound our analysis here, they provide interesting information as stand-alone items.

FIGURE 1. OLS models, Selected Articles Experiment.

The Selected Articles Experiment was designed to test the effects of individual participation on support for the constitution. In this experiment, we made it very simple for respondents to see the outcome and how it related to their own participation. This allowed us to differentiate clearly between experimental manipulations that featured effective and ineffective participation.

Perhaps the best way to discuss the results is to take each treatment in turn. The three versions of the effectiveness of participation varied considerably but not necessarily in the expected manner. This experimental approach of course depends to some degree on the assumption that participants remember their expressed preferences in the first stage. This may vary slightly between the issues considered. As noted above, we expected that participants would have settled preferences on some issues (for example, abortion) and have devoted less time previously to considering other issues (for example, the powers of ombudspersons). Nevertheless, we find it reasonable to think that, having once given this some thought, participants would be able to discern whether or not the amended texts (which were short and bluntly worded) followed their preferences.

Effective participation would seem to be most likely to increase respondents’ support for the constitution; after all, these respondents saw exactly the kind of text for which they had voted. However, we found that the effective participation treatment had no discernible effect for most outcomes of interest. In the case of a simple question asking if one’s views have been included, the treatment actually had a negative effect in comparison with the control group. The ineffective participation treatment would seem most likely to reduce support for the constitution. Instead, we found no statistically significant effect for the ineffective participation treatment. These respondents were shown text that went exactly opposite to their expressed preferences for the five articles. Yet their responses were not systematically different to the control group who did not express a preference (except in a free text response) and who saw a random selection of revised texts.

The random effect participation treatment group emerges here as the most interesting. These respondents indicated their preferences in the first wave and saw some of their preferences reflected in the revised texts in the second wave, while other articles were revised in the opposite direction. This treatment produced negative effects in both our IRT measure of support for the constitution and in the extent to which participants understood their views to be reflected in the text (though it is only significant at the 0.1 level). Why might this group have a more negative reaction than the group that saw none of their views reflected in the revised text? One explanation might be that, when one has won on two out of five issues, the losses on the other three are much more obvious and are felt more deeply. As this group most closely corresponds to political processes in the real world, the negative effect of participation in this treatment should be weighed carefully.

Our treatment that sought to cue procedural fairness had no significant effects on our main outcomes of interest. This suggests that, in a narrowly drawn process that focuses attention on a few specific linguistic choices, it is difficult to craft a narrative of a fair process. However, the major finding from this experiment is that participation, whether effective or ineffective, has little impact on individual-level support for the constitution. On the whole, this experiment found no support for Hypothesis 1 (regarding the expressive value of participation), nor does it find support for Hypothesis 2 (regarding the appearance of a fair process). The null hypotheses stand thus far.

FULL TEXT EXPERIMENT: DESIGN

In the Full Text Experiment, we used a similar set up that leveraged delivery of the manipulations across two waves but crafted the experiment in a broader way that is both in some ways more realistic and also more able to capture the larger societal effects of a participatory constitution-making process. In this experiment, after reading a vignette describing the constitution-making process, participants were presented with what was described as the first official draft of the new constitution. The various treatment groups completed different tasks in this first wave (more on this later). Participants were then asked to return to the experiment three weeks later and react to a slightly revised version of the constitutional text.

We used a de-nationalized version of an English translation of Iceland’s 2011 draft constitution for the first wave—a constitution that was in fact crowdsourced. This text is rather short by comparative standards (7,926 words) and relatively simple in its content and language. In the second wave, we showed respondents a revised version of this text. The revised text had a total of 494 changes (240 insertions and 254 deletions), but the changes were minor in the main. The revised text shares 92 percent of its text with the original text (mimicking the low levels of change in between penultimate and final drafts in real-world constitution-making processes (Hudson Reference Hudson2021b).

The key item to measure is, of course, support for the constitution. As in the Selected Articles Experiment, we asked respondents in both waves to answer a battery of questions about their support for the constitution—in this case, six questions: five questions using a Likert scale and one rating of the constitution on a scale from one to ten. In our analysis, we again combined the five Likert items into a single measure of latent support for the constitution using an IRT measurement model. Other data were also collected, relating to perceptions of the fairness and legitimacy of the process, correspondence between participants’ values and the content of the constitution, and the overall quality of the constitution. We also collected data on some demographic and political characteristics that might have an impact on their views concerning the constitution.

In this experiment, we used a recontact study with a total of 2,552 respondents divided into four groups to identify the legitimating/support-generating mechanism. The three treatment groups either participated in the constitution-making process through written comments on a proposed text or were given detailed information about the substance of participation. These groups are described in more detail below. A third treatment group both participated and received information about the fairness of the process. Working with the survey research firm Qualtrics, we recruited a sample of 1,027 respondents from the United Kingdom, 1,011 from the United States, 257 from Australia, and 257 from Canada for participation in the first wave. Within each country, we included quotas to match census data on gender and age. In the second wave, we allowed for some attrition and finished with a sample of 1,299 respondents (520 from the United Kingdom, 519 from the United States, 130 from Australia, and 130 from Canada). For this experiment, we chose to recruit participants from these countries since we needed a large population of native speakers of English (as this was the language of the constitutional text we used). We also wanted to include some variation in constitutional culture or constitutional history in the sample.

Participants in the control group were presented with the constitutional text in the first wave, the revised text in the second wave, and questions about support for the constitution and the process that created it in both waves. Respondents in what we call the “commented treatment” were either asked or were required (we evenly split respondents between these) to contribute some substantive comments on the draft constitution in the first wave, with the implicit suggestion that the draft might be revised to better accommodate their preferences. In the second wave of the experiment, participants in the treatment group were asked about their level of support for the constitution and other matters relating to the process. Crucially, the second constitutional text was revised but not in line with the comments from the participants. This feature of the experimental design isolates the difference in support for the constitution between those who had an opportunity to express their views (commented treatment) and those who did not (the control group). As noted above, we varied this treatment between required and optional participation. The optional participation version of the treatment is likely to be more valid, but we needed to cover the possibility that too few respondents will respond to an optional prompt to gather sufficient data. In the end, these groups appeared broadly similar.

The main focus of the Full Text Experiment is a manipulation that emphasized the fairness of the process, while not actually changing the constitutional text in response to the input from the participants. To fully isolate this “fairness treatment” from the experience of the participants in the “commented treatment,” respondents in this group were not given an opportunity to make a substantive comment in the first wave (in an identical way to the control group at that stage). Differing from the control group, the second wave of our “fairness treatment” presented participants with data about what other participants (those in the “commented group”) had to say when we asked them to comment on the constitution in the first wave. We did not tell the participants in the “fairness group” the real source of the data, but the fact that the comments were generated based on the same constitutional text added some realism to the treatment. The key thing was to demonstrate that there was a high level of participation and extensive engagement with what the participants had to say. We therefore provided summary data on the subject matter of the comments we received and described the care and thoroughness with which this content was handled. We did not make any statements that claimed that the text was revised to incorporate these preferences. Crucially, while the constitutional text was changed in the second wave, it was identical to the text presented to the control group and the “commented treatment” in their versions of the second wave and was not changed to match the preferences expressed by participants in the first wave of the “commented treatment.”

Full Text Experiment: Analysis

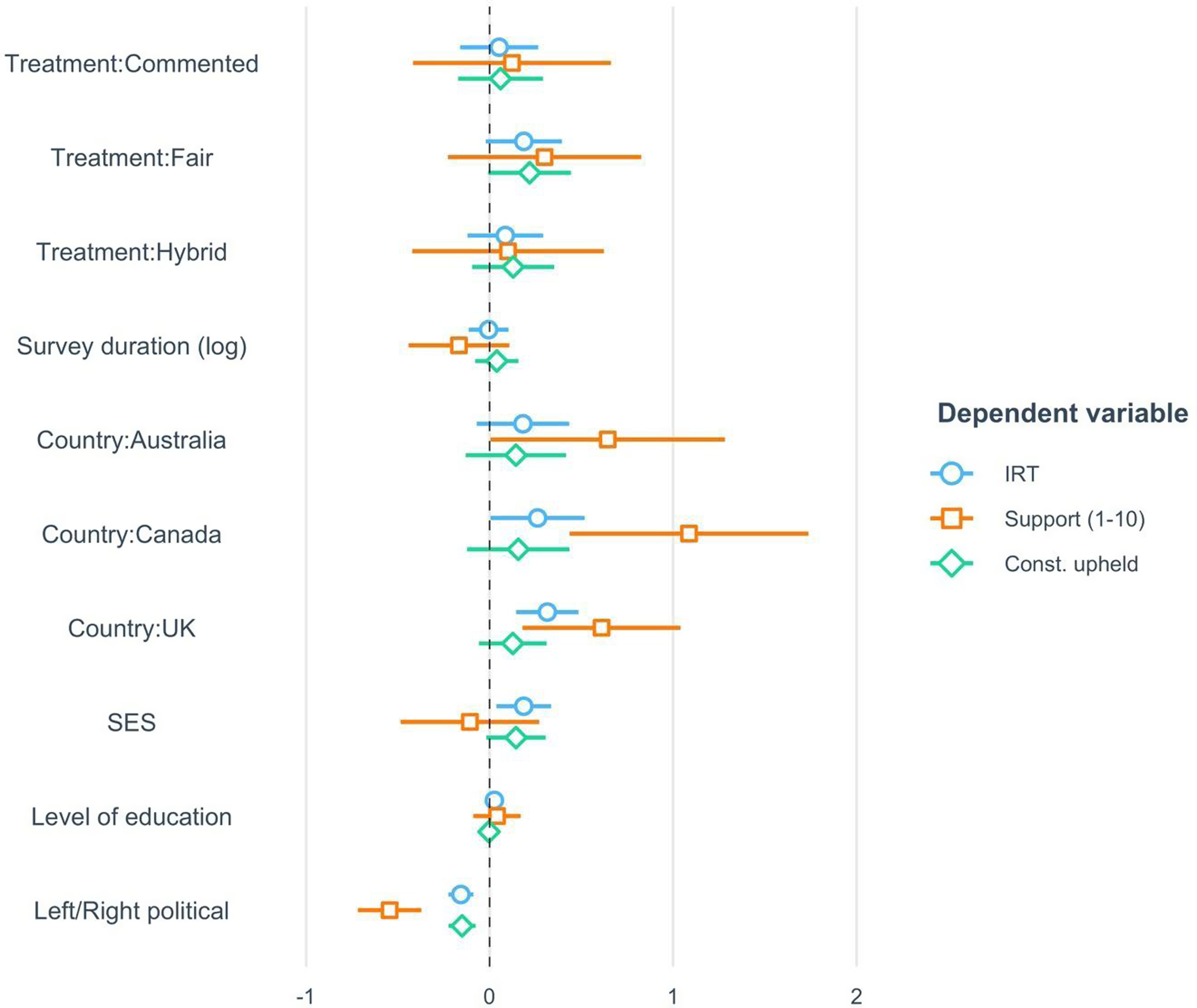

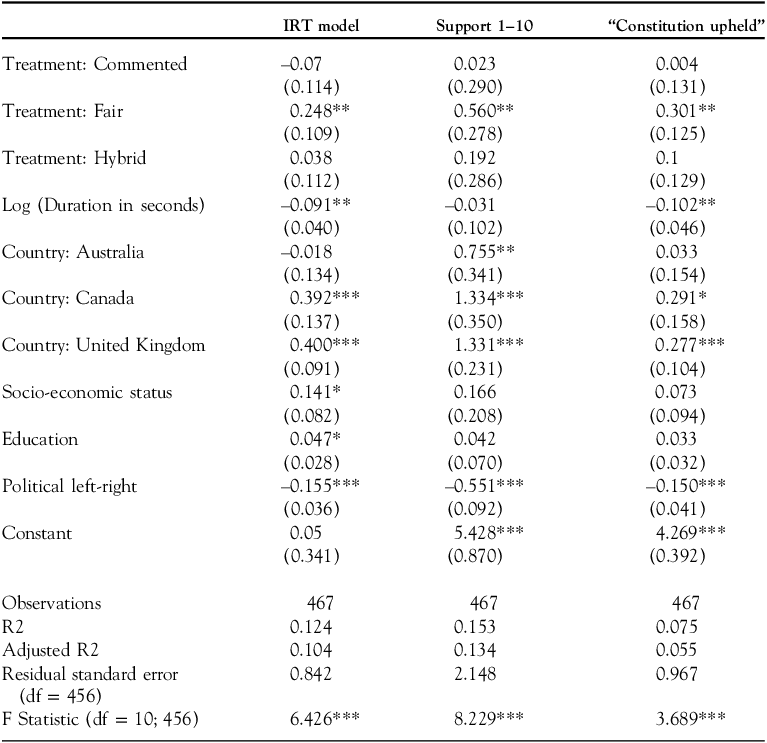

The survey experiment produced some interesting results for our primary research interests and also some interesting information about the differences between the countries in our sample. Including, as it did, such a lengthy text, our survey was quite demanding and explicitly asked respondents for twenty-five minutes of their time. As we presented them with a full (though comparatively short) constitutional text, we expected that committed respondents would need some time to complete the survey. However, a substantial minority of our respondents sped through relatively quickly. For some of our analyses, we subset the data to only include those who spent at least ten minutes on the survey in the second wave. In Table 2 in Appendix 2, we present three regression models (OLS) using different measures of support for the constitution. Model 1 uses an IRT measure of a single factor for support for the constitution. Model 2 uses a single question that asked respondents to rate their support for the constitution on a scale from one to ten. Model 3 uses a single question that best captures the underlying concept of diffuse support for the constitution, asking to what extent respondents agree with the statement: “If it is ratified, this proposed constitution must be upheld and respected in all circumstances.” The comparison category for the treatment groups is the control group, and the comparison country was the United States. In Figure 2, we graphically illustrate the regression analysis.

FIGURE 2. OLS models, Full Text Experiment.

Having noted the significance of the country effects, we also ran several regression models that isolated respondents from each country. We present four regression models using the full sample from each country in Table 3 in Appendix 2. The most notable finding when we separate the countries is the difference between the United States and Canada with regard to the “commented treatment.” In the United States, we find that asking respondents to comment on the proposed constitution actually decreases their support for the constitution, while, in Canada, it increases it. On the whole, the mean score on our IRT measure of support for the constitution varies by country, with Canadian respondents being the most positive about the constitution (see Table 4 in Appendix 2).

The results of this survey experiment support one of our proposed mechanisms of legitimation and produced differential effects depending on the country for another. The “fairness treatment” demonstrated strong support for a mechanism relating to procedural justice that applies at the societal level (in contrast with what we found in the Selected Articles Experiment). In this experimental manipulation, the text of the constitution was not changed to reflect the preferences of respondents (even as we presented this information), but respondents were influenced by the description of the fairness of the process and the substance of the participatory elements and reflected this in their answers to questions about support for the constitution. This offers some support for Hypothesis 2 (regarding a fair process).

In the main, we did not find support for an individual-level explanation as operationalized through the “commented treatment.” Much in line with what we found in the Selected Articles Experiment, it appears that merely expressing one’s views concerning the constitution does not have a positive effect on one’s level of support for the constitution. Between the two experiments, we see no evidence for Hypothesis 1 (regarding the value of expression for support). In the case of our US respondents, it actually had a negative effect. This is an interesting outcome. We cannot yet say whether this surprising finding in the United States is the result of respondents paying greater attention to the content of the constitutional text or other aspects of US political or constitutional culture (for example, cynicism generated by the events surrounding the 2020 election and the inauguration of President Joe Biden).

DISCUSSION

The two experiments touched upon different aspects of public participation in a constitution-making process. The Selected Articles Experiment isolated the potentially different effects of effective and ineffective participation. Contrary to what we would have expected, participation had no significant effect on support for the constitution and was not enhanced by the effectiveness of that participation. While more experimental work in this area would be valuable, we are confident in rejecting an alternative hypothesis that participation is directly influential on support for the constitution. Instead, it seems that participation has no effect in most cases and may have a weakly negative effect in cases where participants can see that they were heard on some issues and ignored on others. In the Full Text Experiment, procedural fairness emerges as the most plausible link between processes for public participation and support for the constitution. In that experiment we were able to reject the null hypothesis (no effect) and find a significant and positive relationship between cues about the extent, fairness, and inclusiveness of participation and support for the constitution.

The two experiments we conducted provide us with valuable insight into how participation in a constitution-making process affects the views of the participants and how the larger picture of the participatory process might inculcate a higher level of support for the process among non-participants. However, even recontact studies cannot tell us a great deal about how these dynamics change over time and what may be the long-term legitimating/support generating effects of public participation in constitution drafting.

A cursory look at the history of twentieth-century constitution making presents a mixed picture in that respect. A given country’s constitution may well acquire legitimacy over time, even where minimal or no public participation at the drafting or approval stage has taken place. Japan’s 1946 Constitution or Germany’s 1949 Basic Law, to pick two examples, both adopted in the wake of the Second World War without public participation and with heavy involvement of foreign drafters, now enjoy wide legitimacy and support in their respective polities. In other, more recent instances—arguably more relevant to our study as upstream public participation has only become the norm since the 1990s—constitutional transformations that did not involve meaningful public participation (for instance, in Ecuador in 2008 and in Thailand in 2007) failed to develop support for the constitution and were short-lived. By contrast, in South Africa, where an extensive public participation process took place during the drafting stage in 1994–96 and where that drafting process was generally perceived as fair and inclusive (Everatt, Fenyves, and Davies Reference Everatt, Fenyves and Davies1996; Segal and Cort Reference Segal and Cort2011), the constitution has enjoyed wide support despite the considerable political crises that country has been through since the new constitution was adopted (including two presidents who resigned under duress). That South Africa’s constitutional order successfully withstood such fierce political pressures is a triumph that is unlikely to have taken place without well-established diffuse support for the constitution and the institutions it created.

Either way, measuring such longitudinal support-generating effects of public participation in constitution drafting appears to require a different experimental set-up that not only involves long-term recontact (say along the lines of decades-long medical follow-up studies) but also holding constant a number of possible intervening variables that may well render such a longitudinal study non-feasible. This is a challenge that our short-term recontact design naturally avoids.

This study further highlights the possible difference between the legitimating effect of public participation in wholesale constitutional overhauls and in instances of targeted replacement of particular provisions. In the case of a process of wholesale constitutional replacement, where the full text is under discussion, a rejection of an individual participant’s preferences is less likely to affect that participant’s level of support for the constitution than in a context where there is particular attention to only a select few articles of the constitution. In the latter scenario, the discrepancies between popular inputs and constitutional outputs are much clearer to participants, and a participatory process that does not produce all of the desired outcomes may actually have a negative effect on diffuse support for the constitution.

CONCLUSION

Public participation in the early stages of constitution-making processes is now commonly practiced and is widely perceived as a best practice and as necessary for the adopted constitution to achieve a high level of diffuse support. Yet, as the actual effect of such participation on the constitutional text is often modest at best, the supposed legitimating effect of participation begs for close analysis. One way to think of the participation of the public in a constitution-making process is to return to the (admittedly) hackneyed philosophical question: “When a tree falls in a lonely forest, and no animal is nearby to hear it, does it make a sound” (Twiss and Mann Reference Twiss and Riborg Mann1910, 235)? Or, metaphorically interpreted for our present purposes, if the people participate in a constitution-making process, but the drafters do not hear them, do they still legitimate the constitution? The answer is yes but only sometimes.

Our two survey experiments featuring recontact studies of participation in constitutional drafting of selected articles and of full text constitutional drafting exercises suggest that two separate mechanisms may link participation to diffuse support. The first addresses the individual act of participation, while the second reflects a broader perception of the drafting process’s fairness and openness. We find that, while the act of participation has limited legitimating effects regardless of the extent to which it has an impact on the constitutional text, it is the appearance of a fair and open process that may be the key link between participation and diffuse support for the constitution. Put differently, our experimental research here bears out what many participants in drafting processes may have suspected—namely, that in cases of constitutional replacement, an important legitimating aspect of participation is the appearance of genuine fairness. In these cases—the 1997 Constitution of South Africa or the 1988 “People’s Constitution” in Brazil are prime examples—the particular flaws of the constitution and the ways in which input from the public was ignored can be overlooked in favor of the larger aspect of massive and open public involvement in a pivotal moment of a nation’s political life.

Legitimating a new constitution is an immensely important consideration for designers of constitution-making processes. Our research suggests that current best practices in terms of participation in the drafting stage may be successful in achieving that purpose but perhaps not for the reasons one might assume. The appearance of fairness is the most important factor in creating diffuse support at the moment of drafting and is likely to produce effects that persist despite some problems in constitutional performance. Even so, a fair process could be achieved through purely representational processes in most contexts, and designers of constitution-making processes in the years to come will need to critically examine whether the present trend toward participation has much to offer their particular case, particularly given the time and expense it involves.

APPENDIX 1. SURVEY MATERIALS

Survey Questions Measuring Diffuse Support

-

1. Are your views included in the proposed constitution? Would you say:

-

a. All my views (1)

-

b. Most of my views (2)

-

c. Some of my views (3)

-

d. Few of my views (4)

-

e. None of my views (5)

-

-

2. This proposed constitution expresses the values and aspirations of the people.

-

a. Strongly agree (1)

-

b. Somewhat agree (2)

-

c. Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

d. Somewhat disagree (4)

-

e. Strongly disagree (5)

-

-

3. If it becomes law, people should follow what is written in this proposed constitution whether they agree with it or not.

-

a. Strongly agree (1)

-

b. Somewhat agree (2)

-

c. Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

d. Somewhat disagree (4)

-

e. Strongly disagree (5)

-

-

4. If it becomes the law, this proposed constitution must be upheld and respected in all circumstances.

-

a. Strongly agree (1)

-

b. Somewhat agree (2)

-

c. Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

d. Somewhat disagree (4)

-

e. Strongly disagree (5)

-

-

5. If it is ratified, the rulings of the courts should be in accordance with the new constitution, even if it contradicts what the majority of the people want.

-

a. Strongly agree (1)

-

b. Somewhat agree (2)

-

c. Neither agree nor disagree (3)

-

d. Somewhat disagree (4)

-

e. Strongly disagree (5)

-

-

6. On a scale from 1 to 10, how much would you support this proposed constitution?

The “selected articles” experiment used questions 1-4 and 6 in a IRT model. The “full text” experiment used questions 1-5 in an IRT model.

Introductory Vignette (First Wave of Surveys)

Imagine that your country is drafting a new constitution. A popularly elected constitutional assembly has been preparing a draft constitution, and has asked for feedback and input from members of the public. Individuals and groups will have some weeks to send the constitutional assembly their ideas about the constitution. After this, the constitutional assembly will revise the draft. The constitutional assembly will vote to approve the draft, and then put it before the public for ratification in a binding referendum.

“Fair Process” Vignette (Second Wave of Surveys)

This vignette describing a participatory process of constitution-making was used in the “fair process” treatment in both experiments.

A few weeks ago we contacted you about a constitution-making process in your country. We’d like to give you an update, and ask you to interact with the constitution-making process again.

A popularly elected constitutional assembly has been meeting in the capital to draft the new constitution. They published a preliminary draft some weeks ago, and invited members of the public across the country to comment on the draft and suggest changes to it.

The response to the constitutional assembly’s request for public comments on the draft constitution was excellent. Tens of thousands of people from across the country wrote to the constitutional assembly through various means, and suggested changes to the draft constitutional text.

The staff at the constitutional assembly carefully analysed the input from members of the public. They compiled a number of reports, including summaries, tables, and the full texts of the input from the public. These reports were distributed to the members of the constitutional assembly.

The constitutional assembly members considered these reports carefully, and made references to the input from the public in their deliberations.

The volume of contributions from the public was itself impressive. Tens of thousands of people from across the country participated in some way, either through the official channels set up by the constitutional assembly, a petition, or other means of communication with individual members of the constitutional assembly.

One of the key tasks of the constitutional assembly’s staff was to group the comments thematically, providing the drafters with an overview of the issues of concern to members of the public. Here are ten of the most popular themes in the comments from the public.

Many other themes were addressed in fewer comments, as the participation from the public captured a diverse representation of political views. Conservative suggestions on topics such as taxation, firearms, and immigration were included in the comments from the public, as were more liberal suggestions on topics such as environmental protection, gender rights, and economic redistribution.

As the full texts of the comments from the public were provided to the members of the constitutional assembly, even issues that do not appear in the summary tables informed the deliberations.

Members of the constitutional assembly expressed their gratitude to the multitude of people from across the country for such an impressive level of engagement with the draft constitution. They carefully considered the input from the public and used that information to inform their deliberations.

APPENDIX 2. STATISTICAL MODELS

Table 1. OLS models, the Selected Articles Experiment

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Table 2. OLS models, Full Text Experiment regressions

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Table 3. Countries treated singly (OLS)

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Table 4. Mean legitimacy scores by country