Even before its inaugural journey in January 1983, the Caracas Metro shaped Venezuela’s capital city. It has in turn been shaped by the desires, frustrations, and identities of caraqueños (residents of Caracas). More than a technical structure of public transport or a response to the traffic and congestion of the city, the metro has always been a social project. It produces and directs both urban space and the political subjectivity of residents in an open-ended and sometimes antagonistic sequence. It is an object of political contests and one of the principle terrains on which struggles that define Caracas, and Venezuela more generally, are fought.Footnote 1

By the twenty-first century the stakes of these struggles could hardly be higher. Economic collapse in the 1980s and 1990s triggered the implosion of Venezuela’s once praised Punto Fijo system of pacted democracy.Footnote 2 After a neoliberal 1990s, the return of record oil prices and a series of key victories by popular and especially urban social movements opened space for the Chávez government to carry out sweeping changes to Venezuela’s political, social, and human infrastructure. The expansion of the Caracas Metro (hereafter, MetroCCS) is a key example of these reforms, providing a way to productively invest windfall oil revenues while altering the physical terrain of politics in Venezuela for years to come. The twenty-first-century expansion of the MetroCCS system to include modernized buses, extended subway routes, light-rail networks throughout the Caracas area, and a series of cable-car routes linking precarious and informal districts along the hillsides of the capital to the city center are not merely public works projects. They are also projections of an ethical stance vis-à-vis the collective life of the city, democratizing space and amplifying the mobility of caraqueños. That is to say, the MetroCCS not only functions as a pedagogical apparatus oriented toward the behaviors of passengers and citizens. It is also, importantly, an egalitarian vector of a right to the city for all who inhabit and traverse it.

For the French Marxist Henri Lefebvre, the right to the city extends classical concepts of political, civil, and social rights. Lefebvre, whose theorization was “more provocative than careful” developed the term in response to the global—but especially Parisian—uprisings of 1968 as a way to assert the increasingly social and spatial aspects of capitalist accumulation and antisystemic struggles for equality (Reference Marcuse, Brenner, Marcuse and MayerMarcuse 2012, 29). The right to the city demands access to what the city has to offer, but also, and more important, a voice in how the city is defined; it is a demand for both appropriation and participation (Reference PurcellPurcell 2014, 150). Since its original formulation, the demand for a right to the city has been asserted in fights against gentrification, privatization, police and private surveillance, socioeconomic inequality, and political exclusion. It has, in short, crystallized a multitude of demands and movements against the late-capitalist tendency to fragment and commodify collective life (Reference HarveyHarvey 2008; Reference MayerMayer 2009; Reference McCannMcCann 2002; Reference MitchellMitchell 2003; Reference PurcellPurcell 2014).

Academic treatments of the right to the city in Venezuela for the most part center on questions of land ownership and infrastructural support in the urban periphery, or on participatory—protagonistic is the preferred adjective of the Bolivarian Revolution—aspects of twenty-first-century democracy (Reference FernandesFernandes 2010; Reference Humphrey, Valverde and Angosto-FerrándezHumphrey and Valverde 2014; Reference Lajoie, Sugranyes and MathivetLajoie 2010; Reference Madera, Sugranyes and MathivetMadera 2010). However, significantly less has been written concerning the role of urban transport infrastructure in extending and facilitating these new rights, perhaps because of the extent to which “the expansion of the right to the city through citizen participation has been restricted by urban segregation and social polarization. The city is not a shared space for social integration and transformation but an increasingly divided one between rich and poor, Chavistas and anti-Chavistas” (Reference Humphrey, Valverde and Angosto-FerrándezHumphrey and Valverde 2014, 158). The MetroCCS cuts across these frontiers physically, carrying with it the potential to open settled spaces and substantiate the right to access, appropriate, and transform the city. This is precisely why it has become a preferred target of the more violent sectors of the Venezuelan opposition.

This article examines the MetroCCS as an infrastructural assemblage and result of contests over space and power across three sections. The first provides a brief history of the Metro as conceived by elites in the mid-twentieth century. In this moment the pedagogical function of urban infrastructure corresponds with those positivisms that see citizens as raw materials for the modernizing designs of technocrats and experts. The second section examines a shift in the composition of Caracas and the social relations that define it after El Caracazo of 1989. Here I suggest that the politics enacted by social movements in response to the neoliberalization of Venezuela can be usefully interpreted as a demand for a right to the city—that subjects have the right to access, shape, and themselves be shaped by the urban environment (Reference HarveyHarvey 2008; Reference MarcuseMarcuse 2009). These demands in turn laid the groundwork for a newly conceived role for the MetroCCS in the twenty-first century. While the metro continues to act as a social engineer in Caracas and to display vestiges of the past’s positivisms, its interventions reflect a reconfigured and often contradictory balance of forces in Venezuelan politics between the government and the opposition and between forces of order and more democratic tendencies among the government and its allies. I conclude with a brief analysis of 2014’s violent antigovernment protests. The tactics and targets of these protests—barricades and direct attacks on public infrastructures such as the metro—illustrate the perceived threat democratized urban space poses to traditional elites.

La Gran Solución para Caracas: Planning, Social Engineering, and the MetroCCS (1926–1983)

The use of infrastructure as social project has a well-established history in Venezuela. Military and civilian governments throughout the twentieth century adhered to a positivist social philosophy that aimed to transform Venezuelans whose “effective constitution” was stunted by history, geography, climate, race, and the built environment into subjects responsible enough to enjoy the “written constitution” of a modern liberal democracy (Reference Bautista UrbanejaBautista Urbaneja 2013, 8; Reference Vallenilla Lanz and ZeaVallenilla 1980, 369). Urbanisms have played key roles in these attempts at modernization, and city life was imagined as a means by which elites could “discipline the barbarity” they saw in their co-nationals (Reference CartayCartay 2003, 192). Even still, in Venezuela, as in much of Latin America, most urbanization has been unplanned. The pace of urban growth has far outstripped the ability, or desire, of planners to provide for the basic needs of a majority of the population (Reference López MayaLópez Maya 2011, 44); by some estimates more than half of caraqueños currently reside in informal and often precarious settlements (Reference Ocaña Ortiz and RolandoOcaña and Guardia 2005, 165). As late as 1992, Aristobúlo Istúriz (then newly elected mayor of Libertador, the largest of Caracas’s five municipalities) noted with dismay that his office all but completely lacked even basic information about the city. The absence of zoning codes, an accurate census of residents, or even a reliable map of streets and services all contributed to what he described as the “special anarchy” of Venezuela’s capital city (Reference HarneckerHarnecker 2005, 24).

The planning and construction of the MetroCCS was part of a series of attempts to bring order to this situation. It originally followed in the path of previous modes of pedagogical developmentalism that stretched from the French-inspired and Hausmannesque Plan Monumental de Caracas (Monumental Plan of Caracas, PMC) of 1938 (Reference AlmandozAlmandoz 1999) to the no-less-Eurocentric architectural vision of the Nuevo Ideal Nacional (New National Ideal) of the midcentury Pérez Jiménez dictatorship (1948–1958). In these schemes, planners and policy makers insisted that order, stability, and a conquered environment were prerequisites for the “moral, intellectual, and material” improvement of the people and the country (Pérez Jiménez, quoted in Reference Ramos RodríguezRamos 2010, 30). Public infrastructure projects like the MetroCCS were not only “concrete embodiments of progress … transplanted from metropolitan centers to the national soil”; they were also considered endowed with the power “to bring progress to Venezuela” (Reference CoronilCoronil 1997, 173). As a result, most urban planning in Caracas focused on monumentality and automobility as markers of progress, while geography and demographics conspired to make traversing the capital an increasingly arduous ordeal for its 3.2 million residents—nearly a fifth of the national population—when construction of the MetroCCS began in the late 1970s (Reference Marcano RequenaMarcano Requena 1979).

Given the layout of the city, plans for subterranean transit settled on a major east-west conduit shortly after the World Bank published a position paper in 1959 recognizing urban transport as key to economic growth, with explicit reference to Caracas (Reference Padrón ToroPadrón 1990, 11–14). It was only with the oil bonanza of the 1970s that construction began. By 1978, ten stations and connecting tracks were under construction, as were massive public works and arts projects, such as the expansion of the Bulevar de Sabana Grande and the water-fountain complex at the Plaza Venezuela (Metro de Caracas 1982). Plans also included two future north-south lines, eventually opened in 1987 at El Silencio-Zoológico and 1994 at Plaza Venezuela-La Rinconada (Metro de Caracas 1979, 19–35). In 1986 the MetroBús fleet was incorporated into the MetroCCS as a subsystem, with a service map initially limited to future subway routes (Metro de Caracas 2007, 47).

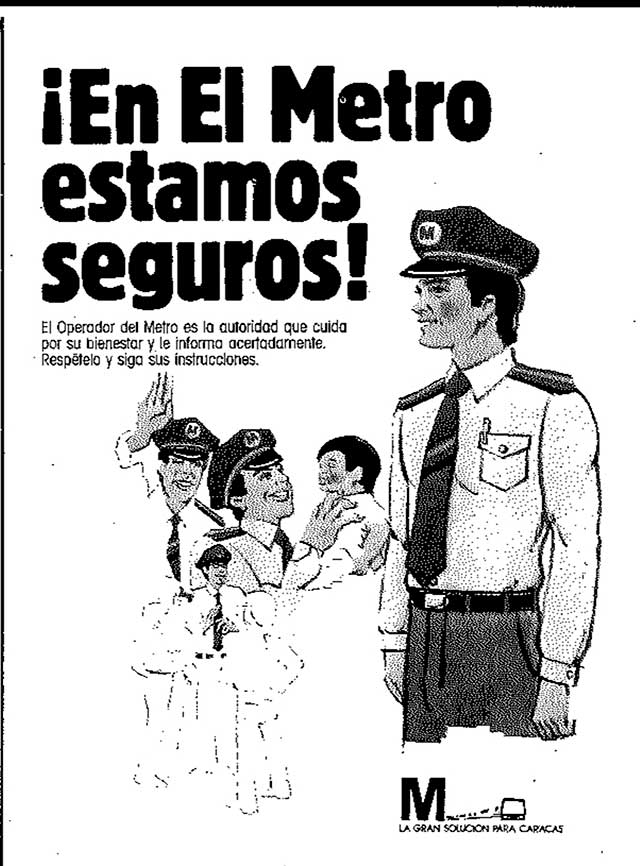

In the two years immediately preceding its opening in 1983, a massive campaign—La Gran Solución para Caracas (The Grand Solution for Caracas; see Figures 1, 2, 3)—sought to train residents for what planners promised would bring about the most “radical and beneficial changes to daily life that the city had ever seen” (Reference Padrón ToroPadrón 1990, 161).

Figure 1: Viajar en El Metro es muy fácil … siguiendo estas sencillas instrucciones. (It’s very easy to travel on the Metro … following these simple instructions). (Metro de Caracas n.d.).

Figure 2: ¡En El Metro estamos seguros! El Operador del Metro es la autoridad que cuida por su bienestar y le informa acertadamente. Respételo y siga sus instrucciones. (We’re safe on the Metro! The Metro’s conductor is an authority that cares for your well-being and wisely guides you. Respect him, and follow his instructions). (Metro de Caracas, n.d.).

Figure 3: Sienta orgullo de El Metro …! Y ayude a conservarlo limpio: Respete las normas del usuario y así estará colaborando a mantener El Metro en buen estado. Recuerde no botar basura en el suelo ni entrar al Sistema con alimentos o bebidas. (Feel pride in the Metro …! And help keep it clean: by following the rules as a user you’ll be contributing to the upkeep of the Metro. Remember not to throw garbage on the ground, or to enter the system with food or beverages). (Metro de Caracas n.d.).

The designers of both the MetroCCS and the Gran Solución campaign were explicit in their belief that theirs was an endeavor of civic and social as well as civil engineering. These were not merely step-by-step instructions on how to use a new technology. They were rather key elements of a coherent vision for Caracas and Venezuela as a whole. Indeed, official MetroCCS publications are explicit in this regard, elaborating a five-point program for its role in this new social project:

1. Urbanism—The MetroCCS is a key element of the modern city for reasons both practical (the circulation of people and goods) and symbolic (the overcoming of the city’s natural limits, and a means to secure membership among the ranks of world class cities).

2. Urban regeneration—The MetroCCS would open the city for new waves of economic growth (construction of the metro itself, but also of secondary effects in real estate markets and cross-sector increases in efficiency), and a means by which to transform “the cultural life of Caracas.”

3. Stable source of work—The MetroCCS promises a steady source of income for future operators, support staff, and construction workers. It would also create new economic hubs around stations that would also stimulate employment.

4. Testimony of progress—The MetroCCS illustrates Venezuela’s national development and progress.

5. Acts of government—The MetroCCS shows the “institutional commitment on the part of the state to benefit the collectivity, but especially for the popular sectors” (adapted from Reference Padrón ToroPadrón 1990, 163).

The MetroCCS was meant to be a political and civilization-defining achievement, a tool of economic intervention and, perhaps most important, a means to transform the city and its inhabitants. As a disciplinary apparatus it altered the behaviors and consciousness—the very subjectivity—of bodies “accustomed” to what planners described as the reigning “casual lawlessness of urban transit” into manageable, orderly, and rule-abiding citizens (Reference Padrón ToroPadrón 1990, 164–165). The MetroCCS was thus at one and the same time conceived as a practical solution to traffic, a symbol of national progress, the means of achieving said progress, and a motor for the production of modern subjects.Footnote 3

What is most striking about the Gran Solución campaign is not so much its content—safety advisories, instructions for use, anti-graffiti and -litter messages, cues on how to navigate the mechanical and physical environments of the subway—but rather the way in which it updated existing grammars of power for a new configuration of infrastructure and subjectivity. New regimes of authority and affect were grafted onto the city, with smiling and uniformed conductors ensuring an orderly and almost familial extension of the pedagogical state-citizen dynamics of the past. The Gran Solución incorporates riders as responsible and autonomous individuals and as part of a collective endeavor, but it does so treating them as passive bodies in need of instruction, called on to obey as beneficiaries of a massive technological feat. Thus, while its egalitarian aim of easing access for all caraqueños can be said to have potentially democratizing effects, at this stage the MetroCCS cannot be said to be democratic or participatory. It operates on citizens, and perhaps it looks to operate through them. At this stage, the MetroCCS does not attempt to act with caraqueños.

The Gran Solución would be the last attempt of the Punto Fijo state in Venezuela to pursue development through massive infrastructural investment. By 1981 the project neared financial insolvency, requiring another round of emergency funding and another opportunity for the siphoning of public funds (Reference Padrón ToroPadrón 1990, 133). When it opened in 1983, the total cost reached more than US$1 billion (in 1983 dollars) (Reference DiehlDiehl 1983, A16). Beyond the perhaps predictable fiscal issues surrounding such a massive endeavor, the MetroCCS opened as the social, political, and economic order disintegrated. With iterated crises of the 1980s and neoliberalization in the 1990s, long-simmering social tensions along fault lines of race and class dominated urban and national imaginaries. The poor were increasingly cast as threats and as the vectors of the barbarity and ungovernability that elites had been working to discipline, redirect, and stifle for decades (Reference CartayCartay 2003; Reference GonzálezGonzález 2005; Reference RotkerRotker 1993). The MetroCCS sought to rationalize traffic and transit in the capital and to impose a more modern and metropolitan mode of life among caraqueños. These aims and the political order they reflected would not survive the coming crises that began a few short months after the pomp and ceremony of the inaugural journeys of the Gran Solución para Caracas.

From Pedagogical Infrastructure to a Right to the City: The Caracazo and After (1989–2000)

After nearly fifty years of plans, proposals, and half starts, the MetroCCS opened in 1983 amid a slow-burning economic collapse. The oil bonanza of the 1970s dissipated with alarming speed due to a toxic cocktail of mismanagement, predatory lending practices from abroad, and notorious corruption across every level of government (Reference Díaz, Rodríguez and VillegasDíaz, Cipriano, and Villegas 1996, 96–101). With this deteriorating political, economic, and social situation elites were dislodged from their traditional roles as “messengers of the future” and “brokers between Latin American and the ‘civilized’ or ‘modern’ world” (Reference Coronil, Calhoun and DerluguianCoronil 2011, 245). So too was their positivist-pedagogical program for top-down modernization.

Piecemeal austerity accompanied a global fall in oil prices, nullifying the “right to have rights” of the growing ranks of Venezuela’s poor and rendering democracy a “pantomime” of itself (Reference GonzálezGonzález 2005, 113). Cracks in puntofijismo became increasingly unmanageable.Footnote 4 By the early 1980s elite consensus had emerged on the need to open the system, but the proposed reforms—for example, allowing for the direct election of mayors—never matched the scale of the mounting crisis. The inadequacy of these proposals was laid bare with the Caracazo (the explosion in Caracas). In its aftermath, popular pressures accelerated the rate and scope of change—moving from reforms to the Punto Fijo system of pacted democracy to calls for the convocation of a constituent assembly and an overhaul of Venezuela’s socioeconomic order (Reference DenisDenis 2001; Reference López MayaLópez Maya 2011, 22).

Before reconstruction, implosion: almost immediately after assuming office for a second, nonconsecutive term in February 1989, Carlos Andrés Pérez announced one of the region’s most orthodox neoliberal reform packages—despite running an anti-neoliberal and anti–International Monetary Fund (IMF) campaign. In response, a massive, nationwide, and spontaneous uprising caught the government off guard. After its initial inaction and disorientation, the reprisal was brutal. While the figure varies, at least three hundred and up to three thousand people were killed in a five-day police and military crackdown.Footnote 5 Writers on the left (Reference Araujo, Ojeda, Giusti and PárragaAraujo et al. 1989; Reference Beasley-Murray, Cameron and HershbergBeasley-Murray 2010; Reference Coronil and SkurskiCoronil and Skurski 1991) and the right of the political spectrum of Venezuela observers (Reference Briceño-LeónBriceño-León 2006, Reference Briceño-León2012) agree that the Caracazo tore up the social contract of the Punto Fijo era. More fundamentally, however, the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s confirmed and intensified already circulating anxieties around class, race, and violence that were increasingly expressed spatially in the segregation of the city itself (Reference Rotker and RotkerRotker 2002b).

The Caracazo was a catalyst—radical and irrevocable, but one that multiplied rather than created social antagonisms—that left in its wake a city composed of islands of relative familiarity and security surrounded by a menacing sea of “others” (Reference ZubillagaZubillaga 2013, 109). As state and social institutions continued to deteriorate, both violence and the fear of violent crime grew—further undermining what faith remained in constituted authorities like the police and judiciary to guarantee the rule of law (Reference Briceño-LeónBriceño-León 2006, 321; Reference Sanjuán and RotkerSanjuán 2002, 93).

The Caracazo also extended beyond the uprising itself—the rioting, the looting, and the state repression—into competing demands for the future of the city. An isolating and increasingly militarized fear of violent crime and the “other” (Reference Rotker and RotkerRothker 2002b) met with countervailing and democratizing forces that attempted to break down barriers, to move, and to interact with the city and its inhabitants. Pitched battles were fought and continue to be fought over access, over transport, over visibility, and over participation—in short, over the very meaning and practice of shared urban life.

Whereas models of urban life and governance based on private property, accumulation, and developmentalist designs reinforce the familiar exclusions of capitalist societies—all of which become intensified with neoliberalization—the right to the city envisions the urban as a constantly revising work in progress “in which all citizens participate” (Reference MitchellMitchell 2003, 17). The “all” in this formulation is of central importance. To assert a right to the city is also to ask continually, “Whose right? What right? What city?” As Peter Marcuse (Reference Marcuse2009, 191) insists, “It is not everyone’s right to the city with which we are concerned …. There is in fact a conflict among rights that needs to be faced and resolved, rather than wished away. Some already have the right to the city, are running it now, have it well in hand …. It is the right of the city of those who do not have it now” that animates right to the city movements. The demand for the right to the city is transformative and antagonistic. It is a demand to be part of a future city that will necessarily supplant the unequal city of the present (Reference MarcuseMarcuse 2009, 193).

David Harvey adds that to demand this right is to pose a fundamentally dialectical relation between the city and its inhabitants. He writes that “the right to the city is an active right to make the city different, to shape it in accord with our collective needs and desires and so remake our daily lives … to define an alternative way of simply being human” (Reference Harvey, Potter, Marcuse, Connolly, Novy, Olivo, Potter and SteilHarvey and Potter 2009, 49). The right to the city is thus “far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is the right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is … a common rather than an individual right …. [It] inevitably depends on the exercise of a collective power to reshape the process of urbanization” (Reference HarveyHarvey 2008, 23). The right to the city is more than a demand for access to an actually existing polity: it demands an inclusive and collective process to transform social relations and urban space.

The most obvious expressions of a right to the city emerged as local projects in autogestión and cogestión (self-management and co-management) as well as growing incidences of protest over deteriorating public services, police repression, and access to the city (Reference López MayaLópez Maya 2005). Innovative responses to economic decline and political implosion—such as the Mesas Técnicas de Agua (Water Working Groups), the Comités de Tierra Urbana (Urban Land Committees), the Círculos Femininos (Women’s Circles), and the Asemblea de Barrios (Neighborhood Assemblies)—elaborate different aspects of a collective right to appropriation and participation that is vital to any articulation of a right to the city, even when that specific framework is not invoked (Reference AzzelliniAzzellini 2010; Ciccariello-Maher 2012; Reference FernandesFernandes 2007; Reference GrohmannGrohmann 1996; Reference Martinez and FoxMartinez and Fox 2010; Reference MottaMotta 2013). These movements were by their nature intensely local and were born of the necessity of structural adjustment rather than ideological preference. Furthermore, they were often only tangentially unified, especially prior to the coagulating effects of chavismo at the end of the century (Reference DenisDenis 2001). In this respect, the 1999 constitution—particularly articles 26, 82, and 182 concerning popular participation in municipal and regional affairs and a fundamental human right to housing—recognized and concretized but did not create demands for greater autonomy and cogestión.

These calls to transform the unequal city of the 1990s would not have grown in strength and volume were they not consistently faced with countervailing economic, political, and social tendencies. As the crises of neoliberalization deepened, security increasingly became a preoccupation, and the wealthy especially developed a festering siege mentality in the face of what they saw as threatening and racialized “hordes” menacing their civilized parts of the city (Reference Duno-GottbergDuno-Gottberg 2013). Violence—and the fear of violence—increasingly shaped an urban and national imaginary haunted by highly publicized murders, kidnappings, and robberies, all shadowed by a proliferation of walls, security checkpoints, and armed guards (Reference Ciccariello-MaherCiccariello-Maher 2007; Reference Rotker and RotkerRotker 2002a; Reference Sanjuán and RotkerSanjuán 2002; Reference ZubillagaZubillaga 2013).

In the decade between the Caracazo and the election of Hugo Chávez, the social role of the MetroCCS, of urban transit and planning, and of the pedagogical state moved in contradictory and ultimately untenable directions. While Venezuela certainly followed the regional trend toward the decentralization of administrative functions (Reference García-GuadillaGarcía-Guadilla 1997), this was also the moment—in 1989 and 1991—that the central government implemented integrated national transportation plans for the first time. While these plans ran against trends toward decentralization, they were nonetheless neoliberal in orientation and were directed by the architects of key privatizations, such as that of Cantv—the national telecommunications company—in late 1991 (Reference Ocaña Ortiz and RolandoOcaña and Guardia 2005, 166). Urban transit plans, furthermore, were increasingly marked by buzzwords of marketization and a general freeze in construction due to fiscal constraints. Plans prioritized “efficiency” and piecemeal improvements to existing infrastructure while allocating funds for private-sector operators in the hybrid public-sector and informal-sector transit systems of Venezuelan cities (Reference Ocaña Ortiz and RolandoOcaña and Guardia 2005, 168). In one such plan, the state offered loans and grants to entrepreneurs and public-private enterprises in the hillside communities inaccessible by conventional means of mass transit like buses and subways (Reference Ocaña Ortiz and UrdanetaOcaña and Urdaneta 2005, 172, 198). However, these initiatives tended to replicate rather than replace entrenched patterns of bureaucratic bloat, inefficiency, and clientelism, particularly in the capital (Reference Ocaña OrtizOcaña 2005, 174).

As the MetroCCS transformed itself in step with the rest of the Venezuelan state, it also exhibited traits of what María Pilar García-Guadilla (Reference García-Guadilla1997, 47) has characterized as a process of decentralization without democratization, even demobilizing some democratizing movements of the 1980s and early 1990s. Adding to this potentially destabilizing moment of fiscal austerity and administrative overhaul, internal and international immigration patterns to the capital city took on a more impoverished and precarious character as privatization, deregulation, and trade liberalization evaporated middle-class jobs (Reference Portes and RobertsPortes and Roberts 2005, 76). In Venezuela, the artificially large public sector shrank as oil prices dropped throughout the 1990s, contributing to an explosion of the informal sector to over half of the working population and what had become a generalized cross-class obsession with insecurity (Reference HumphreyHumphrey 2014, 256).

In response to growing concerns around insecurity and violent crime, already car-cultured caraqueños saw private autos as a refuge, and urban space was increasingly defined in terms of exposure and vulnerability (Reference AngottiAngotti 1998, 106). As in most other Latin American cities of the time, privatization and the securitization of public space marched in lockstep. The perceived and real dangers of life in Caracas were exacerbated by the jurisdictional fragmentation of decentralizing reforms that multiplied police forces—one for each of the capital’s five municipalities as well as an overarching Metropolitan Police—moves that confused responsibilities and opened new spaces for corruption, a legacy of which can be seen in the persistence of record-breaking murder rates and police complicity with criminal syndicates (Reference HumphreyHumphrey 2014, 257).

The demand for a right to the city in Caracas emerged in response to these social and political crises of neoliberalization. Just as economic adjustment rolled back the project of the city as a shared (if hierarchical and managed) space, new social movements created counterpublics and new visions of collective life. With the electoral successes of the Bolivarian Revolution and Hugo Chávez in 1998, this uneven and contested process of negotiating life in the city entered a new stage, as the state attempted to reassert its historically strong position in Venezuelan polity and society by capturing and institutionalizing expressions of autonomous constituent power (Reference AzzelliniAzzellini 2010; Reference Beasley-Murray, Cameron and HershbergBeasley-Murray 2010; Reference KingsburyKingsbury 2013). These processes can be observed in the reconstruction of the built environment of the city of Caracas and the reimagined role of the MetroCCS in processes of social transformation that pick up pace by 2006. Just as important, we can appreciate the stakes of Caracas’s spatial reorganization by witnessing the forceful counterattacks of those who, recalling Marcuse’s diagnosis, have historically already enjoyed a privileged access to the city, and who are doing everything in their power to maintain that exclusive prerogative.

Bolivarian Infrastructure? Un metro en revolución (2006–2015)

The demand for a right to the city has been implicit but constant across the actions of a number of urban social movements since the 1990s. Expressions of autogestión and cogestión resulted in renovated practices of civic identity and participation beyond the circumscribed representative system of Punto Fijo. Many of these political transformations were institutionalized in the 1999 constitution of the now Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Even more fundamentally, the new constitution acknowledged its basis in a constituent power characterized by Joel Colón Ríos (2011, 368, 378) as “unlimited” and “popular,” where “democracy … trump[s] constitutionalism.” The same forces reflected in Venezuela’s new juridical scaffolding have also been at work reshaping the physical environment of the capital.

As I have argued, concretizing political visions through massive public works and construction projects is nothing new to Venezuela. Indeed, one could plausibly argue that converting oil profits into spectacular feats of social engineering has been a preferred mode of public policy since at least the mid-twentieth century (Reference CoronilCoronil 1997; Reference VelascoVelasco 2015). However, if construction was in many ways predictable given the early twenty-first-century flush of oil money, its direction and new social role were not. While elements of the MetroCCS’s expansion were “shovel ready” before Chávez and the oil boom of the early 2000s, priority was given to housing and transit policies and projects that facilitated access to the city for its poorest and most vulnerable residents. Public transit fare schedules of the MetroCCS and MetroBús—as in other cities—remain far below market price for transport, even by the low standards established by Venezuela’s almost-free consumer gasoline. Perhaps the most emblematic of these policies and projects—the MetroCable in Caracas—operates at a loss and has never sought to justify itself in economic terms, citing instead the need to provide access to the city for those with the least resources (Reference UrdanetaUrdaneta 2012, 458).

The MetroCCS has entered a new phase in its role as social project. In response to opposition attacks on transit infrastructure as part of extraparliamentary attempts to overthrow the government from 2002 to 2004, the MetroCCS initiated a series of internal reforms and took on a more protagonistic role within the wider Bolivarian process. In accord with national reforms to the military, its employees formed a worker militia (Metro de Caracas 2007, 151). In the typical fashion of Bolivarian iconography, the MetroCCS revised Simón Bolívar’s maxim and proclaimed that “all of the metro is a classroom” (Metro de Caracas 2007, 170). Workers convened reading groups on socialism and Latin American History, among other topics (Metro de Caracas 2007, 175). In addition to monies invested in social and cultural infrastructure around subway and MetroCable stations, the public company also developed mobile libraries to serve less accessible corners of the capital (Metro de Caracas 2007, 133). These projects took place at the prerogative of the MetroCCS’s Gerencia de Corresponsibilidad Social (Office of Social Coresponsibility), which was created in 2006 with the aim of integrating riders, workers, and residents in the shared management of urban and transit spaces “according to principles of cooperation, solidarity, knowledge, and shared social responsibility” (Metro de Caracas 2007, 128).

While the MetroCCS has always seen itself as a “cultural and social system” embedded in the greater urban environment, what this means has changed over its lifetime (Metro de Caracas 2007, 57). By 2006, as the system expanded to include cable cars, light-rail, and regional transit, the metro outlined four orienting goals for itself in relation to the larger processes of the Bolivarian Revolution:

1. To produce functional public spaces and order to their constitutive elements.

2. To produce cultural public spaces that provide urban landmarks and shared protected sites.

3. To conceive of public space as an instrument of social redistribution, of community cohesion, and collective self-esteem.

4. To promote public space for the formation and expression of the collective will of the citizenry (adapted from Metro de Caracas 2007, 92).

In contrast to the previous mission statement of the metro and its role in the life of Caracas that emphasized modernization, economic growth, and a symbol of government prowess, the “Bolivarian” metro emphasizes social justice, the formation of shared public space, and participation. As opposed to the monumental approach of public works of previous models, new stations along the expanded network were to serve as cultural and educational hubs for community participation and empowerment. Along the San Agustín MetroCable line, for example, the metro built sports fields, communal kitchens, meeting spaces, and schools directly adjacent to its five stations. Before, during, and after the construction process, the metro sought out the direct participation of local communal councils and other grassroots assemblies for planning and grievances and to fully integrate the community not only as passive beneficiary of public works but also as an active participant in an ongoing process of urban cogestión (Metro de Caracas 2007, 98–100).

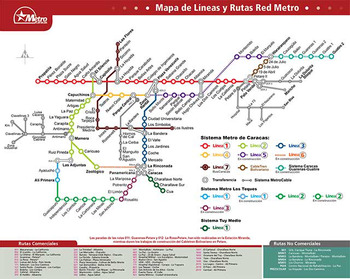

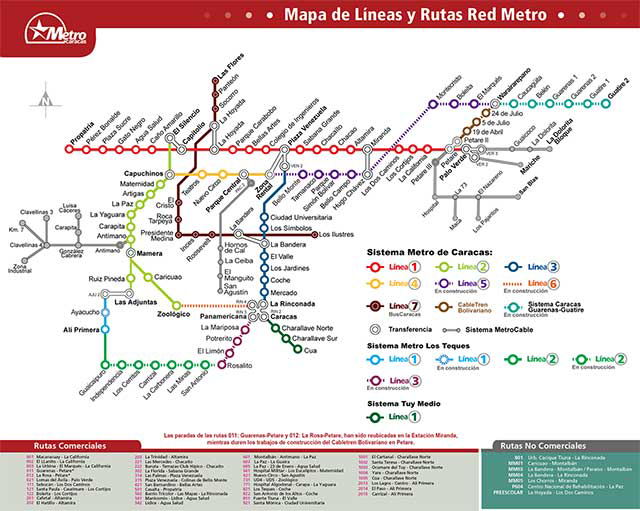

Starting in 2006, the MetroCCS expanded both within the city of Caracas—through a relief line in the east, light-rail lines around Petare (Latin America’s largest barrio), more stations, and a series of MetroCable gondola lines linking hillside settlements to the center of the city (see Figure 4). The first MetroCable installation linking the area of San Agustín to the Parque Central district was inaugurated in 2010. A second line was opened at El Mariche in the east of the city in 2012, and several other cable-car projects are currently in development. The MetroCCS has also worked toward integrating the Caracas region, with commuter rail service to satellite cities such as Los Teques, Guarenas, and Guatire. The company has finally expanded its MetroBús fleet with vehicles that meet contemporary safety, emissions, and disability accessible standards, in an attempt to ease the perennial congestion of the capital and rationalize its anarchic and aging network of private buses (Metro de Caracas 2007, 48). By 2007 there were no fewer than ten new public mass transit projects—subterranean metro lines, light-rail, cable-car routes, and buses—in the works (Reference UrdanetaUrdaneta 2012, 458).

Figure 4: Caracas Metro and MetroBus System Map, 2015.

Of course there have been bumps in the road. The stated goal of cogestión has often held more in principle than practice, and the overbearing role of the state persists into the present. Justin McGuirk (Reference McGuirk2014, 162–173) contends that corruption, petty politics, and government paranoia have contributed to projects going over budget, opening late, or not happening at all. The construction of the cable cars and the expansion of subway routes have all but universally been carried out by foreign firms—Swiss, Austrian, and especially Brazilian—thus missing a potential opportunity to meet the need to develop and diversify domestic industry. Finally, MetroCable projects inevitably find themselves inserted into larger issues that have an impact on the city as a whole. By 2014, for example, residents in San Agustín expressed fears for their safety when walking home from MetroCable stations after dark for lack of adequate lighting, malandros (delinquents) preying on tired commuters, or absent or equally untrustworthy security forces. Special operations of the Guardia Nacional Bolivariana (Bolivarian National Guard) were launched periodically to address these concerns, but in the climate of persistent and generalized insecurity in Caracas, such steps can only hope to be temporary and episodic in nature.

These are in many ways, however, inherited and unavoidable problems in the present conjuncture. Attempts to transform Caracas physically in order to ensure a lasting right to the city occur in spite of entrenched corruption and worsening insecurity, and these blights are by no means caused by attempts to democratize space in Venezuela. More enduringly, the very concrete nature of expanded public transit infrastructures extends the democratizing potentials of the present moment into an uncertain future. The demand for a right to the city—implicit but forceful and prior to the Bolivarian moment—becomes an emplaced fact on the ground. In this way it outlives a given regime, affecting the mobilities, expectations, and behaviors of subjects far into the future.

If infrastructures force future reactions and form subjects in ways that cannot be predicted, the way in which the MetroCCS figured in antigovernment protests of 2014 is far less open and ambiguous. On January 23, 2014—the anniversary of the 1958 fall of Pérez Jiménez—two leaders of Venezuela’s opposition, Leopoldo López and Maria Corina Machado, denounced the “dictatorship” of Nicolás Maduro and called for Venezuelans to take to the streets until the fall of the regime. At a press conference ready made for the Twitter age, they launched their brand, #LaSalida (“the exit,” or alternatively “the solution”) and distanced themselves from the electoral strategy of the mainstream opposition Mesa de Unidad Democrática (Democratic Unity Coalition, or MUD). Over the following months, Venezuela’s major cities were rocked by violent street protests called guarimbas, which included barricades of burning cars, tires, and trash, as well as pitched battles with police and national guard forces, the intimidation of government supporters, and a media campaign that had both sides claiming fraud and misrepresentation.Footnote 6

The MetroCCS was consistently a target of these protests. In the first weeks of the protests, at least forty buses were singled out for attack by protesters (Reference PadrinoPadrino 2014). From February to May, stations were often closed in response to the protests. Kiosks, stations, and bus stops in the opposition strongholds of eastern Caracas—the municipalities of Chacao, Baruta, and El Hatillo—were regularly vandalized and set ablaze (Noticias 24 2014). By April, guarimberos had attacked a number of MetroBús vehicles with Molotov cocktails—often with passengers aboard, hospitalizing two drivers in May alone. On May 6, Haiman El Troudi (minister of transport) reported that more than one hundred buses had been firebombed (YVKE Mundial 2014) and at least fifty-seven employees of the MetroCCS system suffered various injuries (Correo del Orinoco 2014). Protesters also attacked the Parque del Este (Miranda) subway station during operating hours with flaming tires and Molotovs (Noticiero Digital 2014).

Opposition mayors in East Caracas condemned specific incidents—for example, the May 26 attacks on the Ministry of Housing and Habitat in Chacao (Reference BautistaBautista 2014)—and publicly exhorted their residents to engage in peaceful protest (Reference SmolanskySmolansky 2014). Indeed, by late 2015 the guarimbas and the #LaSalida campaign exposed divisions among the tenuous opposition coalition when Henrique Capriles Radonski—former presidential candidate and governor of Miranda, the state in which a majority of Caracas’s guarimbas occurred—described the protests as “a massive national failure” (fracaso) (Reference AmayaAmaya 2015). Most government officials and supporters, however, maintained that opposition mayors like David Smolansky in El Hatillo, Carlos Ocariz in Sucre, and Ramón Muchacho in Chacao contributed to disturbances at the very least by validating protesters’ claims that they were fighting a dictatorship and dragging their feet when it came to enforcing the law (Correo del Orinoco 2014). By the time the wave of guarimbas ebbed in late May, forty-three people from both sides of the political divide were left dead, hundreds more were seriously injured, López was jailed for inciting violence, millions of dollars in damage was recorded, and the sharp polarization of Venezuelan politics was once again forcefully underlined.

Of course, guarimberos burned and attacked anything associated with the government and its social programs. Antigovernment protestors burned food delivery vehicles, medical facilities, schools, cultural centers, and the headquarters of the Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela (Great Venezuelan Housing Mission), betraying their opposition to any attempt to expand access and democratize consumption. However, the destruction of metro stations, kiosks, and buses not only struck at visible representations of the government. They also asserted a specific configuration of intraurban territorial sovereignty, refusing right of passage to citizens of other zones.

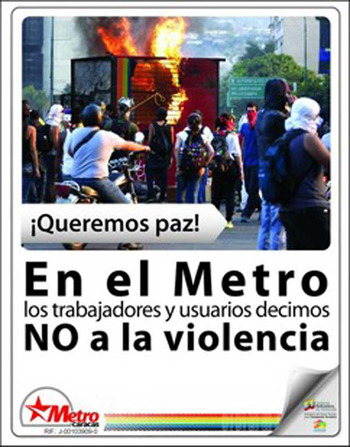

On April 16, MetroCCS workers initiated a campaign against the guarimbas, calling for protestors to respect their right to a safe work environment as well as the right of all caraqueños to safely traverse the city (see Figure 5). They distributed flyers that included photographs of masked protesters burning a metro kiosk, illustrating the competing projects of the opposition and the MetroCCS. In a statement marking the start of the campaign, Edinson Alvarado, president of the MetroCCS workers union said, “While the opposition is destroying buses and attacking our workers and other public institutions, we are making a call for peace and love. We say to them that the only road is that called for by President Nicolás Maduro, that of dialogue and peace” (quoted in Venezolana de Televisión 2014).

Figure 5: ¡Queremos paz! En el Metro los trabajadores y usarios decimos NO a la violencia. (We want peace! Workers and riders of the metro say NO to violence). http://www.vtv.gob.ve/articulos/2014/04/02/con-actividades-culturales-y-entrega-de-volantes-trabajadores-metro-iniciaron-jornada-por-la-paz-4079.html.

The tenor and trajectory of actions carried out in response to the guarimbas by the MetroCCS reflect a highly politicized institutional culture. Most obviously, statements in support of the president against the La Salida campaign are partisan, explicitly taking sides in struggles between the opposition and the government. It should be little surprise that a public company integrated into the national government would follow the orders of the chief executive.Footnote 7 More interesting is the way in which the MetroCCS responded directly to attacks by mobilizing ridership in defense of the transit infrastructure and publicly shaming opposition officials it deemed responsible for the violence. By directly entering the fray, the MetroCCS acted more as a protagonist in complex social struggle than inert infrastructure. It was defending not only itself but also the vision it had adopted for its role in a present and future Caracas.

In a country that is more than 90 percent urban, it borders on banality to suggest that protests shape and are shaped by cities. What is striking about the opposition protests of 2014, however, is the degree to which they both physically exemplify the content of their demands and the way in which they appropriate and redeploy tactics often associated with more progressive ends. First, the protests universally took place in opposition and affluent sectors of the city (Reference NeumanNeuman 2014). The barricade, a tactic perhaps most romantically associated with the New Left of Paris 1968, was in Caracas of 2014 explicitly framed as a means of protecting established zones of privilege from government supporters. They are symptomatic of a deeper siege mentality, a blocking off of a protected zone from a dangerous invasion or contagion.Footnote 8 The guarimbas extend a decades-long practice of erecting policed borders at the internal—racial and class—borders of the city. Protesters sought to destabilize the government, but in actions such as burning dark-skinned and red-shirted effigies at their barricades, they also betrayed a more crassly racist motivation to their desires to interrupt ongoing social reforms (Reference Ciccariello-MaherCiccariello-Maher 2007, Reference Ciccariello-Maher2014a, Reference Ciccariello-Maher2014b; Reference Tinker SalasTinker Salas 2014).

The events of 2014 highlight the degree to which the city of Caracas has become both the object and terrain of political struggle in Venezuela. They also illustrate the importance of transit infrastructure in this conflict. The MetroCCS has served to physically shape and transform the city and to provide access to its processes and services in accordance with the desires of inhabitants previously excluded from the life of the metropolis. It has also become a prominent and representative site of contestation and antagonism, in the military-strategic sense of opposition actions as well as in the imaginary of a city that has been struggling to redefine itself for generations.

Conclusion: Infrastructure and the Right to the City

Like most Latin American cities, Caracas is often a traffic nightmare. Bound by geography and demographic pressures, the city is congested, polluted, and difficult to traverse via surface transportation. The MetroCCS was thus in many ways a natural solution to the practical difficulties of urban life.

However, in each of its three dominant modalities since planning and construction began in the 1970s, the MetroCCS has also been a social project. In the early moments of planning and the Gran Solución campaigns, the MetroCCS extended a postivist-pedagogical relationship of the state to the citizenry established in the early twentieth century. The cultural politics of the subway, like other public works, followed familiar developmentalist hierarchies in which the inhabitants of Venezuela’s capital were seen as raw material, wanting in the cultivation and training necessary for modern citizenship.

The second moment of the MetroCCS stepped away from this emphasis on training. During the economic downturns of the lost decades, the traditionally interventionist Venezuelan state followed regional trends in privatization and decentralization, and while the MetroCCS remained a public company providing a vital service during this era, it did so in a larger discursive environment dominated by the language of efficiency, entrepreneurship, and austerity. It was also during this moment that Venezuelan politics saw a long-standing national project—the Punto Fijo state—collapse. The resulting vacuum was increasingly filled with local projects in autogestión and cogestión and the demand for access and inclusion characterized thematically by the right to the city.

With the electoral success of the Bolivarian Revolution, the MetroCCS again played a key role in a statist project contoured by an ultimately developmentalist worldview, but in importantly different if incomplete ways. First and foremost, the positivistic consideration of passengers as passive pupils has been realigned according to principles of cogestión. Even in moments where this realignment has been carried out in word more than deed, the shift to a more participatory, democratic, and protagonistic metro is striking. The MetroCCS has become more overtly politicized, reflecting changes that have shaped Venezuela since the 1990s. The MetroCCS increasingly acts as a guarantor of a right to the city, and as such, it should be recognized as a terrain, object, and indeed, a protagonist in processes of social transformation.

Transit lines, public services, and the built environment shape the time and space of daily life. Strategies of users and the demands they make on planners and operators shape these vital aspects of the built urban environment. The movements of the 1990s levied political and ethical demands for a future—more inclusive, accessible, and open—city. The backlash to the Bolivarian Revolution in the twenty-first century is also a reaction to these demands.

With each new sequence in the political life of the city, the MetroCCS has been recast as a component in this struggle. However, unlike social relations and political positions—which, to be sure, engender inheritances, identities, and worldviews that structure politics in real and often seemingly immutable ways—there is something about the quite literally concrete nature of these infrastructures that projects a present ethical commitment into the uncertain future. This is why opposition attacks on the MetroCCS have been so violent. An attack on the metro is an attack on the principle and practice of the right to the city.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are in order to the librarians at the Biblioteca del MetroCCS and the Instituto de Urbanismo, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad Central de Venezuela, for their assistance in locating planning documents and official publications. Also to Gregorio Darwich and Beate Jungemann at CENDES, Froilán José Ramos-Rodríguez, Franco Vielma, Victor Rivas, and especially to Theresa Enright for their insights, assistance, and criticisms along the way. Any errors in the finished product are of course solely the fault of the author. Part of the research for this article was made possible by a research grant from Department of Political Science, University of Toronto.