More than two decades into the “populist zeitgeist” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004), populist parties are flourishing on every continent. One of the major debates of scholarship on this phenomenon is whether the rise of populism is an attempted corrective to democracy’s failings. Demand for populist representation seems to rise when governments become distant from “the people,” when corruption is rampant, and when the public has lost trust in the existing political order (e.g., Hanley and Sikk Reference Hanley and Sikk2016; Engler Reference Engler2020). By promising to bring power to people who have been excluded, to enact the popular will, and to reduce the influence of elites, populism creates the potential for democratic renewal. Indeed, there is strong individual-level evidence that individuals who are disillusioned with democracy and have low levels of trust in political actors and institutions are likely to turn to populism (e.g., Doyle Reference Doyle2011; Pauwels Reference Pauwels2014; Roberts Reference Roberts2019; Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, van der Brug and de Lange2016; Schumacher and Rooduijn Reference Schumacher and Rooduijn2013; Voogd and Dassonneville Reference Voogd and Dassonneville2020). Reviewing this literature, Ivaldi (Reference Ivaldi2021, 219) concludes that “one aspect that stands out as a possible unifier of populist voters across time and space is political distrust and disillusionment with mainstream politics,” while Bornschier (Reference Bornschier2019, 219) argues that “representation failure is a necessary condition to make populism successful.”

We contend, however, that the relationship between democratic performance and populist party support becomes more complicated when populists enter office. In this context, incumbent parties should be held accountable for the recasting of the institutional order to alleviate democratic failures they previously attributed to state institutions captured by the corrupt elite. Thus, voters who approve of the remodeled institutional setting will vote for their continuance in office, while those who perceive democracy as weak, because they believe either that it has not improved under populist rule or that its quality has deteriorated, are likely to turn away from the populist incumbent. In other words, in places where populism has entered office, the sustained support of populist incumbents may stem from perceived representational successes, not its failures.

Taking advantage of expert survey data to identify populist parties inside and outside of government in eighteen Latin American countries, we test whether Latin Americans hold populists accountable for changes in democratic performance. While the existing literature suggests that populist party support is negatively associated with institutional trust and satisfaction with democracy, we find the exact opposite in a sample that pools all populist parties. Yet breaking them down by governing status reveals a more nuanced picture. Results show that institutional distrust, a weak economy, and corruption concerns correlate with support for populist parties outside of government. Populists in power, in turn, gain the highest levels of support from those who are confident in institutional arrangements and who are satisfied with democracy. Complementary analyses of survey data from Bolivia spanning 2008 to 2019 show that evaluations of democratic performance even cause those who previously voted for or against the populist incumbent to consider changing their vote intention and induce even partisans to change their electoral choices. Taken together, the results suggest that populists who take office promising to serve as a corrective may face electoral sanction if they fail to help people like democracy is working well.

What drives support for populist parties?

The ideational approach (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rosario Aguilar, Jenne, Kocijan and Rovira Kaltwasser2019) defines populism as a moralized worldview that considers politics as a zero-sum conflict between the virtuous common people who are the true democratic sovereign and a conspiratorial, self-serving elite. Appeals based on this antagonistic understanding of politics can be utilized in support of a variety of political programs from both the Left and the Right; populism is sometimes considered a “thin” ideology that can be grafted onto a variety of “thick” programmatic approaches (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Stanley Reference Stanley2008). This marriage allows populist parties to focus on broad representational failures but also on specific policy goals.

However, this ideological flexibility creates a challenge in modeling the vote for populist parties: One must distinguish factors that lead people to support the thick ideology of the populist party from factors that specifically lead people to endorse a populist approach. For example, many populist parties in Europe draw support from individuals who hold right-wing ideological positions (Agerberg Reference Agerberg2017), who have negative views about immigration (Taggart Reference Taggart2017; Margalit Reference Margalit2019), or who worry about the rise of new “woke” social values that challenge the existing order (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Noury and Roland Reference Noury and Roland2020). However, these factors are not a function of the parties’ populism but instead reflect the overlap between populist rhetoric and nativist worldviews among much of the European radical right (see Hunger and Paxton Reference Hunger and Paxton2022). As a result, many of the ideological, issue-based, and demographic correlates of “populist” voting identified in existing studies are not connected to the level of populism these parties espouse.

Still, populism does seem to generate its own specific appeal. The most explicit evidence for this comes from studies showing that populist party supporters also tend to have populist attitudes, a bundle of beliefs that emphasizes the preeminence of a general will of “the people” that ought to be sovereign, underscores distrust of “elites,” and entails rejecting pluralism (see Castanho Silva et al. Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020 for discussion and critique). The existence of such attitudes suggests that there are specific elements of populism’s thin ideology that can attract voters and create scenarios for populist victories. Indeed, individuals who hold populist attitudes are significantly more likely to support parties that make populist appeals (e.g., Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017; van Hauwaert and van Kessel Reference Van, Steven and Van Kessel2018; Marcos-Marne Reference Marcos-Marne, Plaza-Colodro and Hawkins2020; cf. Neuner and Wratil Reference Neuner and Wratil2022). Populists critique the failings of the democratic system to represent the popular will and allege that elite interests have captured it. Thus, populists argue that a populist victory can improve representation and representative institutions. Populism is therefore also an appeal to rational grievances, and scholars have pointed to voters’ concerns with weak democratic performance and misgivings about failings they see in political, economic, and social relations that lead them to support populist parties.Footnote 1

Unsurprisingly, a linkage between perceived representational failures and support for populists has been well documented, albeit in a body of literature predominantly focused on European populist parties.Footnote 2 The support for populist parties is higher among those who perceive the quality of government to be poor (Agerberg Reference Agerberg2017) or who express lower levels of trust in domestic political institutions (Doyle Reference Doyle2011; Ivaldi and Zaslove Reference Ivaldi and Zaslove2015; Akkerman Reference Akkerman, Zaslove and Spruyt2017; Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Guth and Nelsen Reference Guth and Nelsen2021; van Kessel Reference Van Kessel, Sajuria and Van Hauwaert2021). Similarly, those who perceive politicians as corrupt (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Castanho Silva Reference Castanho Silva2019; Busby et al. Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019) or who are less satisfied with democracy as it is being practiced (Roccato et al. Reference Roccato, Cavazza, Colloca and Russo2020; van Kessel Reference Van Kessel, Sajuria and Van Hauwaert2021) are more likely to opt for populist parties. Political distrust and dissatisfaction generate support for populists on both the left and the right (Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020). While the effect of political distrust is smaller than the direct effect of holding populist attitudes (Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink, Zaslove, Sluiter and Jacobs2020), low levels of political trust and democratic satisfaction generate greater endorsement of populist attitudes (Balta et al. Reference Balta, Rovira Kaltwasser and Yagci2022; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020).

Populist actors explicitly cultivate these feelings, and supporting populist parties further reinforces negative views of the political system and political elites (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn, van der Brug and de Lange2016). Indeed, highlighting representation failures may be particularly effective at generating support from voters who are not already ideologically predisposed to supporting populist parties (Castanho Silva and Wratil Reference Castanho Silva and Wratil2023).

Taken together, we have ample empirical evidence that voters looking to correct systemic failings turn to populist parties. While most of this evidence comes from Europe, some studies suggested that similar factors explained the rise of populist parties in Latin America (e.g., Doyle Reference Doyle2011; Roberts Reference Roberts2015, Reference Roberts2019; Azpuru Reference Azpuru2024)—if institutions are unrepresentative, democracy is performing badly, generating unfavorable outcomes, or corruption is rampant, populists’ projects may indeed be necessary to re-found democratic representation.

However, what happens to these dynamics when populist parties are in government? While the literature on populist party support has firmly established the connection between perceived poor governance and support for populists, the predominance of European samples means that most of the cases examined have been opposition parties or, occasionally, populist parties that have entered coalitions as junior partners. This raises questions about whether the same dynamics continue to hold when populists govern, especially when they control the executive or the legislative branches.

We contend that when populist parties govern, it should be more difficult for those who believe that democracy still needs a corrective to support an incumbent populist. Part of this change may occur as formerly outsider populists become part of the political elite, thus diluting the antielitist appeals and ability to position themselves as a corrective (Barr Reference Barr2009; Balta et al. Reference Balta, Rovira Kaltwasser and Yagci2022). More importantly, we propose that voters examining institutional performance under a populist government should recognize that the incumbent controls many of those institutions and is therefore in a position to fix their shortcomings. If institutions remain weak, the populist party has failed in its objectives, and the logic of political accountability suggests that it should be rejected at the ballot box. Incumbent populists’ failures to improve or revitalize democracy might create space for alternative populist movements or might delegitimize populism itself, but incumbent populist actors should be hurt when institutions remain weak and distrusted on their watch. In contrast, populists who are perceived to successfully provide institutional correctives should be rewarded by the public for accomplishing their goals.

If this proposition is accurate, then the widely documented inverse relationship between evaluations of institutions and support for populist parties should become inverted when populist parties enter government. In other words, voters who perceive institutions as weak, untrustworthy, or nonresponsive should be more likely to prospectively vote for populist opposition parties as a corrective but should be more likely to retrospectively reject both populist and nonpopulist incumbents when failures of democratic representation have not been addressed. This leads us to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Negative views of political institutions and democratic performance will make people more likely to support populist opposition parties.

Hypothesis 2: Negative views of political institutions and democratic performance will make people less likely to support incumbent populist parties.

We recognize that feelings of satisfaction or dissatisfaction underpinning this process of accountability may stem from different considerations or evaluations. The public can, for example, judge the actual quality of institutions: Are elections clean, are civil liberties protected, are representative institutions being empowered or being sidelined? However, those who prefer a more majoritarian style of democracy might be less concerned about horizontal accountability than those who focus on more liberal definitions (e.g., Torcal and Trechsel Reference Torcal and Trechsel2016), especially if their party is in power (e.g., Singer Reference Singer2018; Mazepus and Toshkov Reference Mazepus and Toshkov2022).Footnote 3 Thus, citizens living under the same system of rules might react differently to those changes and evaluate democracy differently. Similarly, the public might evaluate both the substantive changes implemented and the symbolic steps undertaken to address the concerns of underprivileged groups, making those citizens feel like democratic representation is enhanced even when formal institutional checks and balances are being weakened.Footnote 4 The multifaceted nature of representation and responsiveness leads us to focus on the perceived state of democratic performance whereby citizens weigh these different changes and filter them through their own expectations of what democracy should be as the arena of political accountability.

Our expectation about incumbent populist parties differs from recent studies that also acknowledge that the effect of dissatisfaction is likely to differ for populist incumbents. Rooduijn and van Slageren (Reference Rooduijn and van Slageren2022), Castanho (Reference Castanho Silva2019), and Jungkunz et al. (Reference Jungkunz, Fahey and Hino2021), for example, make similar claims, arguing that populist parties in power are unable to mobilize supporters on the basis of populist appeals and antiestablishment messages because they are now the political elite. In contrast to our argument, however, these studies contend that views of democratic performance have no effect on support for incumbent populist parties and that when populists govern, “the unique (political) populism-distrust connection has evaporated” (Rooduijn and van Slageren Reference Rooduijn and van Slageren2022, 7). If, however, voters hold populist parties accountable for their effects on democracy as advanced here, then we expect that views of democratic performance will have a strong positive effect on how the public evaluates incumbent populists.

Several previous studies provide preliminary evidence consistent with our expectations. Albeit studying radical parties instead of populist parties in Europe, Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos (Reference Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos2020) find that high levels of political dissatisfaction generate support for radical opposition parties but lower levels of support for leftist-radical parties in government (but not conservative radical parties in government). However, the authors are focused on coalition parties and not chief executives. Aytaç et al. (Reference Aytaç, Çarkoğlu and Elçi2021), in turn, look at populist attitudes in Turkey during the rule of populist president Recep Erdoğan and find that satisfaction with democracy and the economy is positively correlated with populist attitudes. Most relevantly for the present study, Remmer (Reference Remmer2012) shows that the approval of left-populist presidents in Latin America is higher among those who are satisfied with democracy.Footnote 5 We build on these studies by looking at populist parties of all ideological stripes and by explicitly comparing the factors that generate support for populists inside and outside of office.

Data and measures

Latin America is the ideal region to test our argument. Populist parties are more common than in Europe and have won more chief executives (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rosario Aguilar, Jenne, Kocijan and Rovira Kaltwasser2019). Yet we also find many populist parties that are not particularly successful at winning votes. Latin America thus provides a context where the public has a wide variety of populist parties to choose from both inside and outside of power, with varied track records. More importantly, the success of populist parties in the region and their mixed (at best) record on democratic improvements (Ruth-Lovell and Grahn Reference Ruth-Lovell and Grahn2023) makes it important to know if Latin Americans hold populists accountable for whether their actions are perceived to strengthen or weaken democratic performance.

One potential challenge for establishing the dynamics of populist representation, however, may be that Latin American populist parties may not be directly comparable to populist parties in Europe. Notably, European populist parties span the entire ideological spectrum, while most present Latin American populists are left-leaning “inclusionary populists” (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013). Yet this difference is a contemporary one. Neoliberal populists have frequently won office (Roberts Reference Roberts1995). Moreover, the success of Jair Bolsonaro in 2019 in Brazil, Javier Milei in Argentina in 2023, and the strong showing of José Kast in the 2021 Chilean presidential elections remind us that conservative populism remains a potential force (Zanotti and Roberts Reference Zanotti and Roberts2021). Thus, the regions might be more comparable than one might think.

In analyzing populism, we focus explicitly on support for political parties as units of analysis, as most vote intention surveys record responses at the level of parties. While we expect that voters are thinking about both parties and their leaders as they respond to those questions, the data must be analyzed at the level of the political party, even if a vote against a populist party could be read as a repudiation of its leader. We also recognize that parties take on the flavor of their nominees or leaders, so levels of populism in a party can potentially ebb and flow within a party as the leader changes; Ecuador’s PAIS alliance switched from the very populist Rafael Correa (2017–2017) to the less populist Lenín Moreno (2017–2021), for example. However, dramatic switches are fairly rare among institutionalized parties, while noninstitutionalized parties are, by definition, as populist as their leader is at any given moment. Moreover, inasmuch as the public evaluates the degree of populism in a party as a function of its leader, we would expect evaluations of how populist a party is and its leader is to be highly correlated.Footnote 6 Thus, as long as the study of vote intentions is conducted temporally close to when levels of populism are measured, we can ensure that the survey captures citizen views of a party in light of how populist that party is when looking at it broadly.

To identify populist parties, we use the 2018–2019 Political Representation, Executives, and Political Parties Survey (PREPPS),Footnote 7 an expert survey conducted in Latin America between June 2018 and January 2019 that asked party politics specialists to score whether parties meet each of the specific attributes of the ideational definition of populism (Wiesehomeier et al. Reference Wiesehomeier, Singer and Ruth-Lovell2021). PREPPS avoids the use of the term populism but instead asks respondents to score parties on “a few general characteristics of the kind of appeals political actors make and the kind of rhetoric political actors use.” Respondents are asked to locate parties on the three elements of antielitism, people-centrism, and a moralized worldview while avoiding these labels. The question on people-centrism places parties on a continuum of whether a party “refers to the common people as an authentic and homogeneous unit, with which s/he identifies. (1) or … Refers more generally to citizens with their different interests and values (20).” Respondents were also asked about antielite rhetoric: “For each of the following actors, how important is antiestablishment and antielite rhetoric? Not important at all (1) … Extremely important (20).” Finally, respondents were asked if parties employ Manichaean rhetoric that rejects compromise and instead paints opponents as going beyond the national interest or dehumanizing them (see also Urbinati Reference Urbinati2019) on the following continuum: “Demonizes and vilifies opponents (1) or Treats opponents with respect (20).” For all three questions, respondents scored parties on a 1–20 scale. After rescaling each of the indexes such that the populist positions took the high value, we created an index that scored how well parties met each of these three conditions. Because the three items are not substitutable (Wuttke et al. Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020), we average them using the geometric mean, which accounts for the compounded effect of the underlying dimensions (Klugman et al. Reference Klugman, Rodríguez and Choi2011; OECD et al. 2008, 112–116).

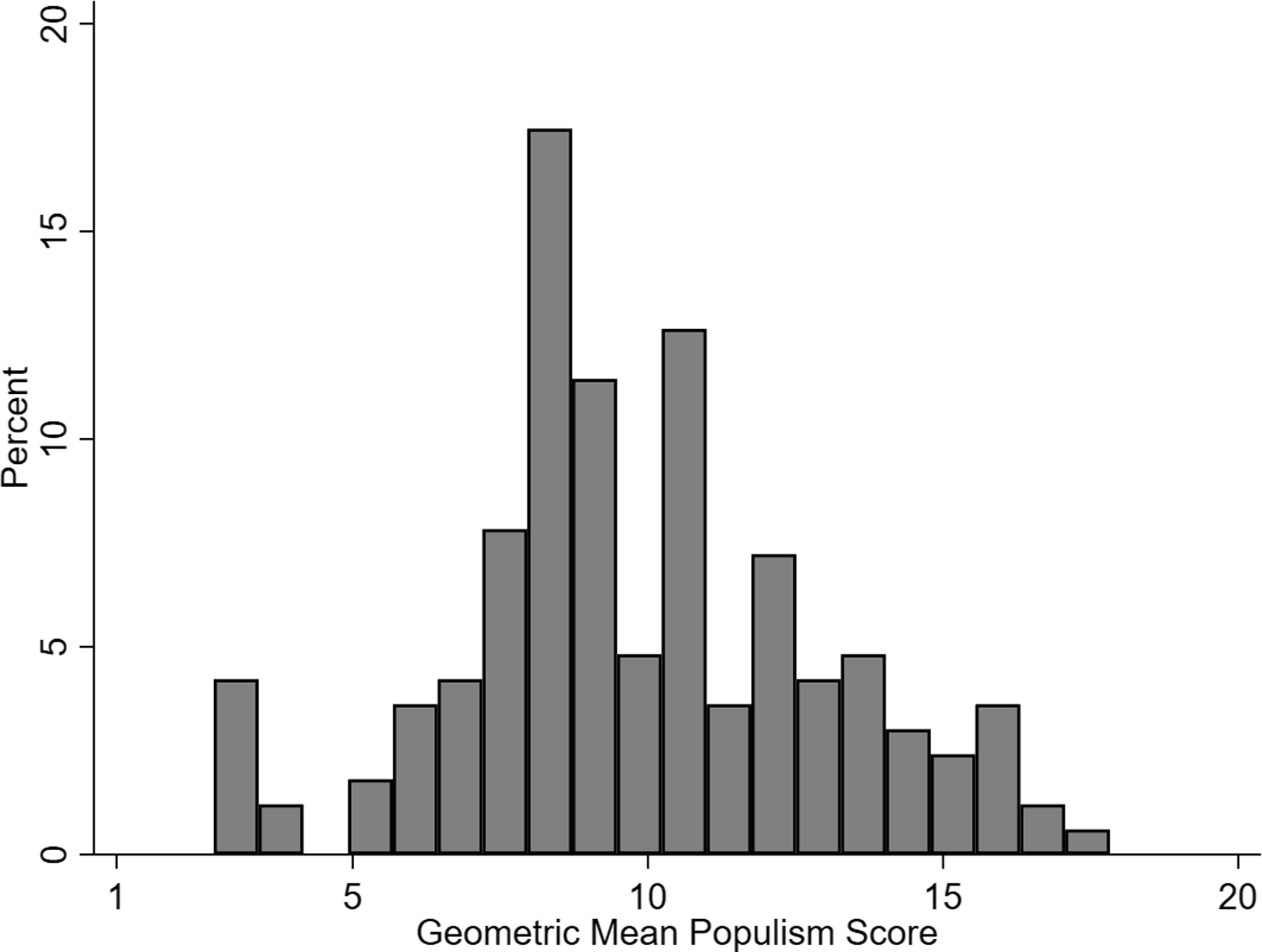

As Figure 1 indicates, Latin American parties vary considerably in their usage of populism. Most parties are well below the midpoint of the scale. Yet many parties strongly embrace all three elements of the ideational definition. The three most populist parties in the dataset are the Venezuelan PSUV (17.82), Ecuador’s PAIS (16.73), and Bolivia’s MAS (16.4). But 75 of the 166 parties in the dataset are above the midpoint of the populism scale, which includes ruling parties and very small parties; the median party above the midpoint of the scale had won only 2.9 percent of the seats in the previous legislative election (we code parties above the midpoint of the populism scale as populist; see Appendix 1 for a comprehensive list). This variation in populist party strength and incumbency status allows us to test our expectations about how the drivers of support for populists vary by governing status.

Figure 1. Populist usage by party

To measure the correlates of populist party support, we use data on vote intentions from the 2017 Latinobarómetro survey. We use the Latinobarómetro because it has an open-ended vote intention question where respondents can indicate which party they would vote for were an election to be held next Sunday,Footnote 8 and we use the 2017 wave because it was temporally proximate to the PREPPS survey. We code the choices of respondents who reported a vote intention as either being a vote for the incumbent (populist/nonpopulist) or a nonpresidential party (populist/nonpopulist).Footnote 9 Each of these options finds widespread support within the sample: 44 percent of respondents intended to vote for the incumbent, 33 percent would vote for a nonpopulist opposition party, and 23 percent would vote for a populist opposition party. Support for incumbents was particularly high among populists: Almost 58 percent of respondents reported an intention to vote for the president in the four countries where the president was coded above the midpoint of the populism scale (Bolivia, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela).Footnote 10 Yet these are not the only populist party options; another 11.5 percent of respondents (or one in three opposition party voters) in those four countries said they intended to vote for a populist opposition party, while 25.5 percent (or two of every five opposition party voters) respondents in countries where nonpopulist parties ruled said that they intended to vote for a populist party. The type of party that the respondent intended to support is the dependent variable in the analysis that follows.Footnote 11

To test our argument about the changing dynamics of populist party support and perceived representational failures, we focus our attention on two measures of system discontent. The first is whether respondents view institutions in the country as trustworthy. To replicate Doyle (Reference Doyle2011), we look at trust in the national legislature, the judiciary, and political parties, averaging trust across the three institutions, with high values representing higher levels of trust.Footnote 12 Our second measure looks at whether respondents report feeling satisfied with the working of democracy in the country.Footnote 13 While the extant literature predicts that institutional trust and satisfaction will be negatively associated with support for populist parties, we expect that they will have this effect only for populist opposition parties (H1) but will reinforce support for governing populists (H2).

In addition, we consider measures of regime performance more broadly by focusing on how respondents perceive the country’s economic situation, crime situation, and level of corruption (see Appendix 2 for question wording). The expectation is that these factors will shift levels of support for the incumbent party as they are held accountable for their performance in office (see Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Singer and Zechmeister2015 for a review in Latin America), while weak performance should particularly generate support for populist opposition parties. As a measure of potential support for incumbent party support, we control for whether the recipient received benefits from a welfare program.

Because we are pooling data on incumbent parties, populist parties, and opposition parties of different ideologies, we do not include demographic, ideological, or issue variables whose main association with vote intentions should be by generating support for a party’s main ideology.Footnote 14 The results are consistent with those presented below if we include those variables (see Appendix 3). We also estimate the models with country-specific fixed effects to capture any residual country-specific factors we are excluding, and the substantive results are unchanged (Appendix 7). Finally, we also estimate the models by adding presidential approval to control for potential endogeneity between support for the leader and views of regime performance (Appendix 5). However, as the Latinobarómetro survey does not have a question about partisanship we control for political predispositions more explicitly in the case study on Bolivia.

Results

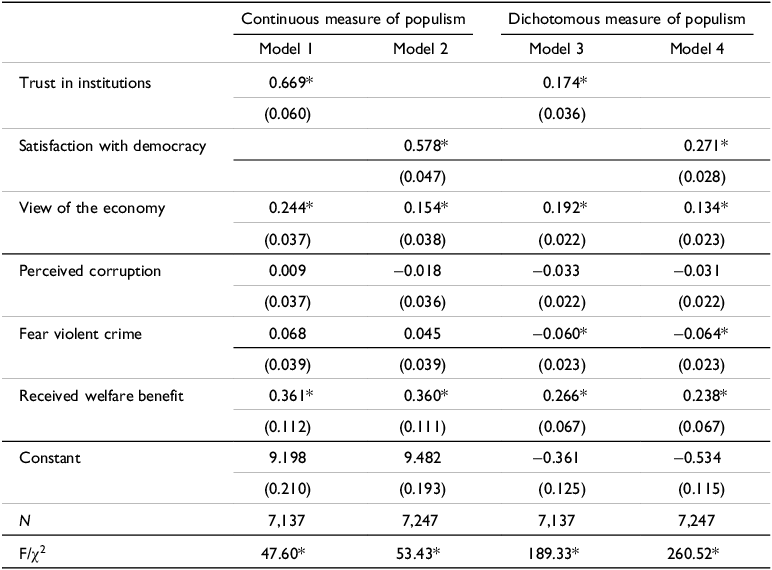

As a starting point, Table 1 simply models the correlates of voting for a populist party. Models 1–2 use the populism measure as a continuous variable (see Figure 1); in Models 3–4 we dichotomize parties as populist or not if they are above the midpoint of the scale. In each case, the correlates of populist party support in Latin America diverge from theoretical expectations from the dominant extant literature: individuals who express higher levels of institutional trust or who are satisfied with democracy tend to be more likely to vote for populist parties. Thus, the average populist party supporter in Latin America is not a disillusioned democrat. Rather, on average, populist supporters in Latin America believe that institutions and democracy are functioning well.

Table 1. Correlates of voting for a populist party

Note: Models 1 and 2 are ordinary least squares regression models, and Models 3–4 are logit models. Standard errors in parentheses

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

These results diverge strongly not only from theoretical priors established in the literature and from results in other regions but also from Doyle’s (Reference Doyle2011) results on support for populist candidates in presidential elections across Latin America. Doyle’s study, however, was done in an era where populist parties were less ascendant in the region. We believe the dominance of populist incumbents drives these results.

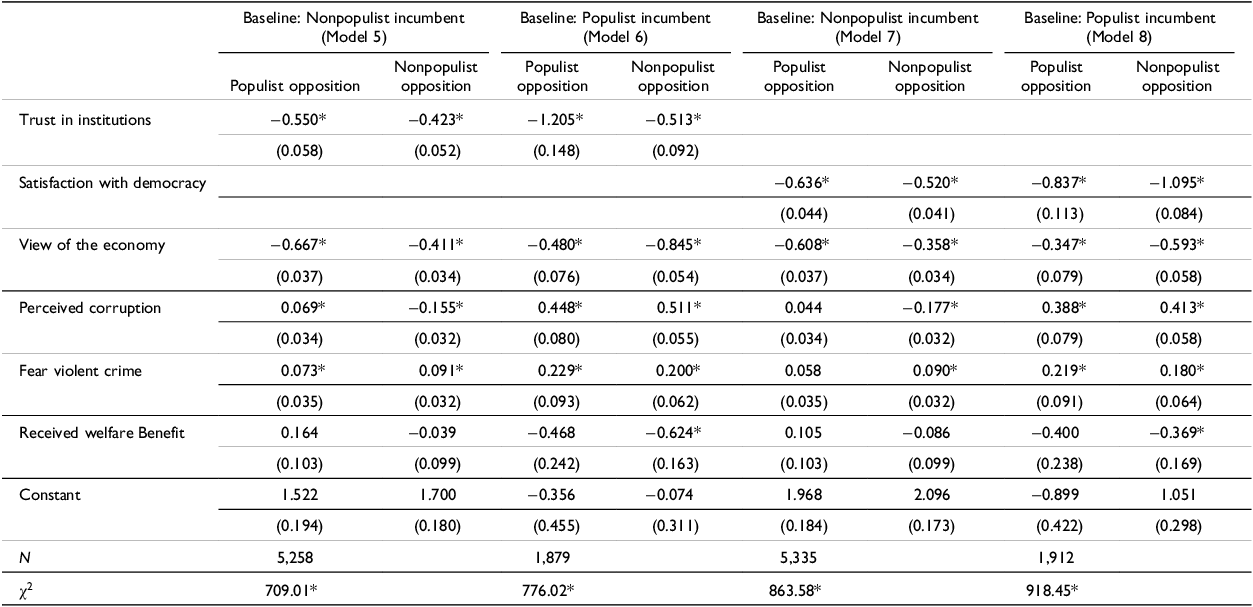

To explicitly test whether this is because the relationship between dissatisfaction and support for populism is contingent upon incumbency, in Table 2 we separate voter intentions into a four-category variable: support for a populist incumbent party, support for a populist opposition party, support for a nonpopulist incumbent party, and support for a nonpopulist opposition party. Because one cannot vote for a populist incumbent party in countries where a nonpopulist is president or vice versa, we split the sample and analyze voting choices separately in countries where the president was below or above the midpoint on the populism scale. In Table 2, we model the factors that make voters choose to vote for either a populist or nonpopulist alternative to the incumbent. In Appendix 4 we present the coefficients differentiating the choice between a populist and a nonpopulist opposition party, making the correlates of that choice easier to interpret.

Table 2. Correlates of vote intentions for populist opposition party, and nonpopulist opposition party by incumbent party type

Note: Multinomial logit, standard errors in parentheses.

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Looking first at countries with nonpopulist presidents, individuals who have confidence in the country’s institutions (Model 5) or who are satisfied with democracy (Model 7) are more likely to report a vote intention for the incumbent. Those who distrust democratic institutions or are dissatisfied with the functioning of democracy, in contrast, are likely to support some form of opposition party but are particularly likely to support a populist opposition party; both variables significantly differentiate between populist and nonpopulist opposition parties (Table A2). Thus, when the incumbent is not a populist, system discontent leads Latin American voters to turn their support to populist alternatives, a dynamic observed in most studies of populism in other regions, by Doyle (Reference Doyle2011) in Latin America and consistent with Hypothesis 1.

When the president is a populist (Models 6 and 8) however, institutional trust and satisfaction with democracy do not lead voters away from populism but instead, consistent with Hypothesis 2, remain strongly correlated with support for the incumbent and thus buoy support for the continuance of populist rule. Yet distrust in institutions under populist rule can also generate support for some form of populism; individuals who believe that institutions are flawed under a populist are more likely to vote for a populist opposition party than for a nonpopulist opposition. Dissatisfaction with democracy under populist rule, in contrast, is more likely to lead people to support a nonpopulist alternative. While our data do not allow us to explicate the mechanism underlying these results, these divergent results suggest that dissatisfied voters who are focused on institutions still believe that a populist alternative could improve them. In contrast, those who are dissatisfied with the overall quality of democracy under one populist party may have become disillusioned with populism more generally. But our results clearly illustrate that support for the incumbent populists is driven by satisfaction with institutions and democracy, not disillusionment in the way that support for populist challengers is.

While we focus on democratic performance, a similar pattern emerges for other aspects of performance. Populist opposition parties facing a nonpopulist incumbent (Models 5 and 7) benefit strongly from those who believe the economy is worsening or that bribery is widespread in their country while fear of crime generates support for both populist and nonpopulist opposition parties. These dynamics again change, however, when populists are in power (Models 6 and 8): Populist incumbents have higher support among those who believe that the economy is strong, who view corruption as rare, or do not fear becoming a crime victim. Yet, under a populist incumbent, individuals with negative views of corruption or crime are as likely to support a nonpopulist alternative as a populist one, while negative views of the economy under populist rule correlate more strongly with support for a nonpopulist alternative.Footnote 15 These results suggest that good performance is key for populists to maintain support once they enter office, while poor outcomes under populist rule negate some opportunities that populist opposition parties would have if the same outcomes occurred under nonpopulist rule.

We have conducted several robustness tests (see Appendix 5). To test for the possibility that these results reflect underlying levels of support for the incumbent president and are thus endogenous to attitudes about the president, we control for presidential approval (Table A3). Those who disapprove of a nonpopulist president are particularly likely to support a populist opposition party, while presidential disapproval does not have a significant effect in distinguishing between populist and nonpopulist opposition to a populist incumbent. More importantly, including presidential approval in the model reduces the importance of economic outcomes, and in particular the effect of corruption in generating support for populist alternatives to nonpopulist governments; but distrust in institutions and dissatisfaction with democracy remain significantly correlated with populist party support inside and outside of the government. These effects remain robust also if we control for whether the respondent believes that democracy is the best system of government (Table A4). Table A4 also suggests that populist supporters are less enamored of democracy than the rest of the public, especially supporters of populist opposition parties. In sum, our robustness checks do not change the fundamental associations: System discontent increases support for populist opposition parties, whereas populist incumbent support is higher if citizens have positive views of democratic performance under the regime.

An illustrative example: Perceived state of democracy and support for Bolivia’s MAS

We believe that the rise and fall of Evo Morales and his Movement for Socialism (MAS) party in Bolivia are illustrative of how populists are held accountable for the strength of democracy. Morales took office riding a wave of popular discontent with existing political parties and political institutions that did not seem to reflect the interests of Bolivia’s poor. In office, Morales spearheaded constitutional reforms that increased the power of the executive and weakened horizontal accountability (Ruth Reference Ruth2018) but that also expanded modes of citizen participation and brought social movements into government in new ways, enhancing symbolic and substantive representation (Anria Reference Anria2016). Furthermore, he oversaw the expansion of government welfare programs and impressive levels of economic growth and poverty reductions. Consistent with a positive model of accountability, the result of these changes was resounding victories in the 2010 and 2015 elections.

However, by the end of the 2010s, portions of the public were growing disillusioned with his political project, including his proposed referendum to enhance his powers and weaken term limits and his failure to reduce corruption. Survey data from the AmericasBarometer showed that in May 2019, five months before the election, levels of democratic satisfaction were lower than they had been prior to him taking office, while trust in the legislature, political parties, and the Supreme Court were at the lowest levels that they had been in his presidency.Footnote 16 As a result of this dissatisfaction, the party lost the referendum on whether Morales could serve another term and when disregarding this outcome and running for reelection did not achieve a majority in the 2019 election, a substantial drop from his previous levels of electoral support.

The apparent correlation between perceived institutional performance under populism and support for the MAS makes Bolivia a most likely case to test our hypotheses in the context of a populist incumbent who saw perceived governance outcomes change throughout his term and who faced a nonpopulist opposition. A detailed analysis of this case with various waves of the AmericasBarometer allows us to control more explicitly for political predispositions that might make associations between perceived governance and electoral intentions endogenous.Footnote 17 The data also include measures of previous electoral choice that allow us to look at changes in support from that baseline to evaluate if individuals who have previously voted for the incumbent can be turned off by bad performance or if those who voted against the populist party can be persuaded to support it if democracy is functioning well.Footnote 18

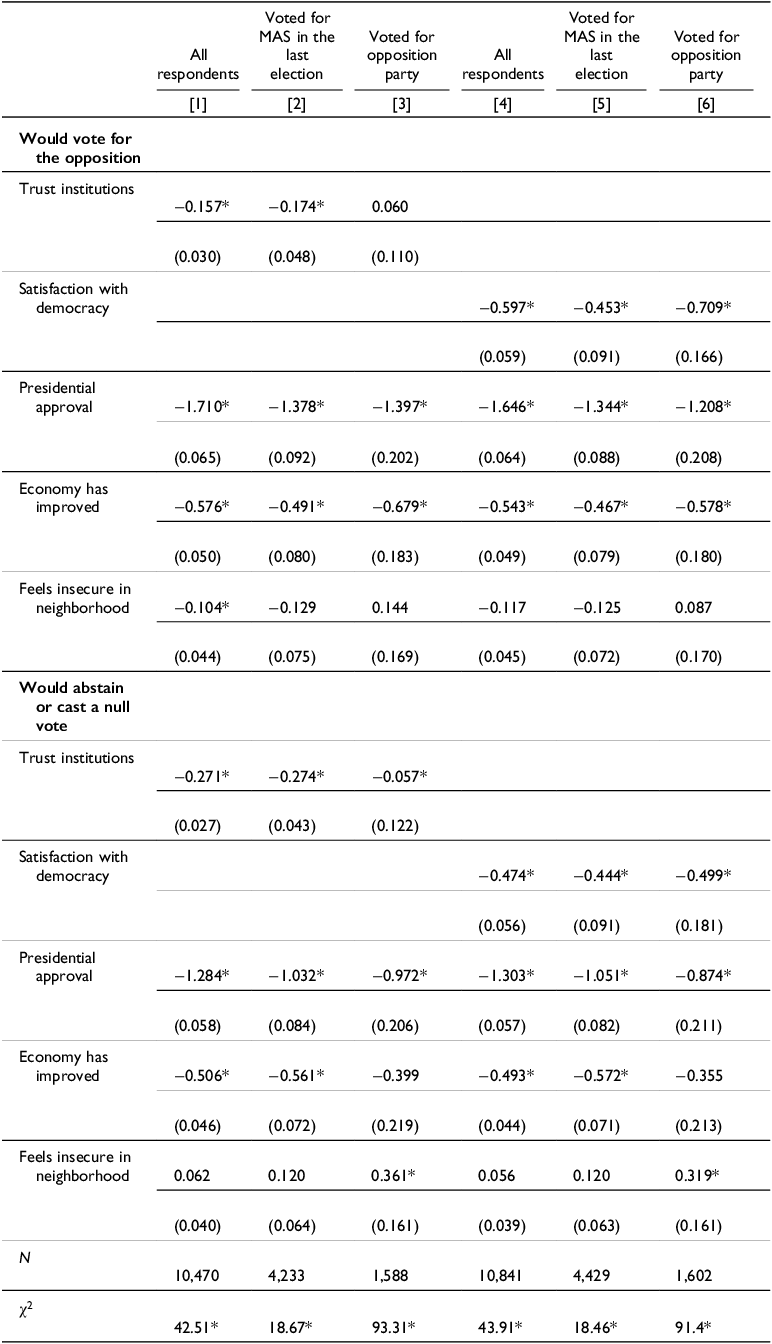

The AmericasBarometer asked respondents what they would do if an election were to be held this weekend: support the governing party, support an opposition party, abstain, or cast a null vote; we combine the last two as a rejection of all existing political parties.Footnote 19 We model vote intentions as a function of institutional trust (specifically the congress and political parties, the two national institutions included in all waves of the survey) and democratic satisfaction while controlling for other factors that might predispose people to support the incumbent such as presidential approval, economic performance, perceived insecurity, corruption victimization, and demographic variables. The details of the variables are in Appendix 8; the coefficients for the controls are in Appendix 9.

Columns 1 and 4 of Table 3 indicate that, on average, individuals who trusted institutions or who were satisfied with democracy were less likely to support either an opposition party or to intend to abstain or cast a null vote even when presidential approval and ideology are controlled for. The positive correlation between perceived democratic performance and support for the populist incumbent is consistent with the cross-national results presented above and Hypothesis 2.

Table 3. Evaluations of democracy under MAS rule and vote intentions by previous vote, 2008–2019

Note: Multinomial logit with a baseline of “would vote for the governing party”; standard errors in parentheses. Includes controls for corruption victimization, rural, sex, wealth, education, ethnicity, and age (Appendix 8).

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

But while these data for the whole sample look at the correlations inside the data, the AmericasBarometer allows us to further explore whether evaluations of democratic performance led people to change their vote from their prior behavior and partisan predispositions. We first run these models separately for individuals who reported having previously voted for (against) the MAS in the last presidential election.Footnote 20 This allows us to control for the possibility that MAS supporters (opponents) were predisposed to have higher (lower) levels of democratic satisfaction or institutional trust and to explore whether these factors can lead previous supporters or previous opponents of the populist incumbent to change their opinion. Models 3 and 6 look at individuals who voted for an opposition party in the last election. While most of them continue to reject the incumbent, the models show that among these opponents, those who are satisfied with democracy are significantly more likely to vote for the MAS: Good performance makes former opposition supporters more likely to reward the incumbent with their support. Models 2 and 5, in contrast, look at respondents who reported that they voted for the MAS in the last election. Most remain loyal; 70 percent intend to vote for the MAS again. However, the significant coefficients for institutional trust and democratic satisfaction imply that previous MAS supporters who were discontented with system or democracy performance became more likely to switch their support away from the MAS. Dissatisfied MAS voters endorse different types of opposition depending on the form their dissatisfaction took; those who are dissatisfied with democracy have an increased probability to either vote for an opposition party or abstain or nullify their vote, while those who have low levels of trust in existing political institutions are more likely to abstain or nullify their vote. In sum, the results confirm that Morales’ voters were increasingly willing to abandon him when confidence in his institutional rule faltered. This helps explain why his support dropped before the 2019 election: Bolivians held him accountable for the declining quality of democracy.

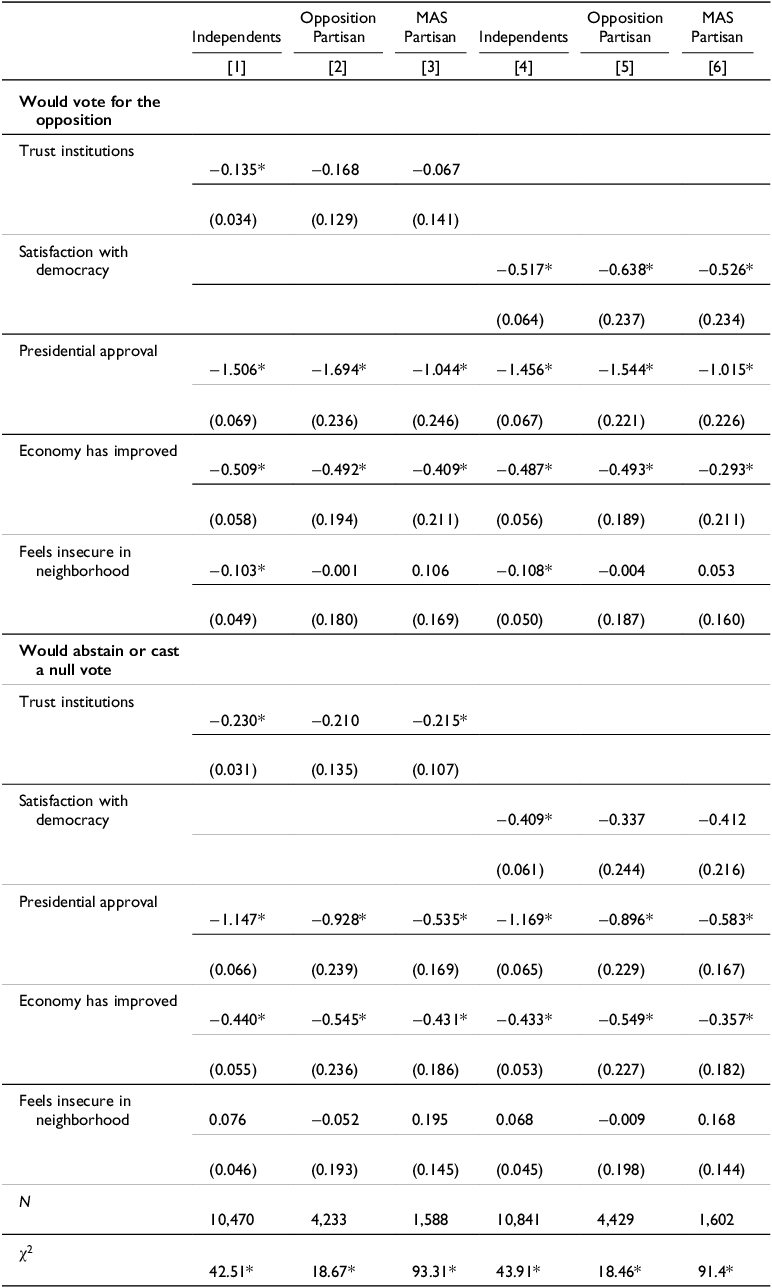

The AmericasBarometer survey also allows us to test whether evaluations of democratic performance affect voting choices even among partisans. The survey asks respondents if there is a party that they sympathize with and, if so, which party that is.Footnote 21 In Table 4 we estimate the model of vote choice for those who do not sympathize with a party, those who sympathize with a party other than the MAS, and those who sympathize with the MAS. The results show that while independents who distrust institutions or who are dissatisfied with democracy are less likely to support the populist MAS in Models 1 and 4, negative reactions to the MAS among those dissatisfied with democracy are not limited to independents. MAS partisans who distrust institutions are more likely to reject the MAS and abstain while those who are dissatisfied with democracy are likely to support an opposition party. In contrast to an accountability model, opposition partisans do not significantly change their vote based on perceived institutional performance, but they are significantly more likely to defect from an opposition party to support the MAS when they are satisfied with democracy. This does not mean that partisanship is erased; opposition partisans who are satisfied with democracy are still unlikely to support the MAS, while MAS partisans who are dissatisfied with democracy are unlikely to vote for an opposition party. However, democratic performance affects even partisans’ levels of support for the populist incumbent in a way consistent with a model of political accountability.

Table 4. Evaluations of democracy under MAS rule and vote intentions by partisanship, 2008–2019

Note: Multinomial logit with a baseline of “would vote for the governing party”; standard errors in parentheses. Includes controls for corruption victimization, rural, sex, wealth, education, ethnicity, and age (Appendix 8).

*p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Conclusions

Populists tend to depict themselves as defenders of democracy who will address failures of democratic representation. Extent literature highlights that voters concerned with the failings of representative democracy will turn to populist parties as a potential corrective for democracy. We contend that these appeals should have resonance when institutions are weak and populists are political outsiders, but that populism’s continuance in power should become dependent upon changing those perceptions. Indeed, that is what we find in our analyses: Populist opposition parties have strong bases of support among those who distrust existing institutions, are dissatisfied with democracy, believe the economy is poor, and believe that bribery is a major part of the political system. In this sense, the individual-level findings underscore that despite the many differences in form and ideology of European and Latin American populist parties, their electoral bases when outside of power are very similar.

Yet while these factors create opportunities for political outsiders, ruling populist parties have concentrated support among those who are satisfied with the system and with the economy and governance under populist rule. Those who perceive performance as poor under populists, in contrast, are split as to whether they should support a different populist or should support a nonpopulist challenger. But in our data, citizens dissatisfied with democratic and institutional outcomes under a populist ruler tend to reject the incumbent, even those who voted for the populist incumbent in the past.

Our results, therefore, suggest that while the public is willing to give populists a mandate to reform the political system, they may also hold them accountable for whether they actually act as a corrective to the perceived shortcomings of democracy. Accordingly, an optimistic reading of our results implies that even when populists rule, elections work as instruments of democracy (cf. Powell Reference Powell2000), with voters evaluating populists’ performance and responsiveness, ultimately holding them accountable. By holding populists accountable for how they manage democracy, the public should create incentives for populists to improve government responsiveness and governance.

This optimistic implication, however, may be overstated if the process of political accountability becomes blunted at the ballot box, and indeed accountability faces several threats under populism. For example, models of accountability assume that individuals perceive that their preferred party has performed poorly in office whereas many individuals who support the ruling party in countries where democracy has weakened are unwilling to acknowledge those failings as long as their group is prospering (Singer Reference Singer2023; Monsiváis-Carrillo Reference Monsiváis-Carrillo2021). Indeed, results from Brazil suggest that at least in the immediate aftermath of the elections, Bolsonaro’s supporters grew more supportive of democracy, while at the same time approving of institutional ruptures such as military or executive coups (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Erica Smith, Moseley and Layton2023). Thus, even if populist party supporters perceive that the government has not done as well as they hoped, they might be unwilling or unable to sanction the government. Individuals who believe that the government has performed poorly are, however, less likely to sanction them if they have strong ideological disagreements with or distrust of the political alternatives (Svolik Reference Svolik2019). Populism, with its polarizing rhetoric, is likely to build and exacerbate such feelings of distrust as is the ability of populists to reinforce their support by emphasizing their thick ideology (e.g., Gidron et al. Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023). At the same time, many populists in office have weakened the institutions of vertical accountability that would enable a disenchanted public to express that dissatisfaction (e.g., Houle and Kenny Reference Houle and Kenny2018; Ruth-Lovell and Grahn Reference Ruth-Lovell and Grahn2023). While the Bolivia results presented above show that accountability can overcome partisanship and electoral loyalty, for many voters it may not. Finally, our results also suggest that many populist party supporters are not entirely sold on the importance of democracy, which may entail that they might not be motivated to stand up for it. So, while our results presented here suggest that dissatisfaction with poor-performing populism might create weaknesses for populist rulers, there is no guarantee that the public will act or will be able to act on that dissatisfaction.

However, the cross-sectional results presented here suggest that populists face the possibility of accountability for their actions with regard to democracy; if there were no correlations between views of democracy and populist party support, then the possibility of accountability for governance would be foreclosed. This suggests that opposition parties facing populist incumbents should emphasize ways in which their rule has weakened democracy or undermine and corrupted institutions, bringing them away from the demands of the public. Populist challengers win support when democracy is perceived to perform badly, but incumbents who can’t fix the problem risk losing public support.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2025.1

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sofia Moreno, Melissa Meyer-Berg, Tanya Sinha, and Catherine Sollose for their research assistance, participants at WAPOR-Latin America and EPSA and especially Robert Huber for their feedback, and IE University, the University of Leiden, and the Alan R. Bennett Professorship for financial support. This paper won the Edgardo Catterberg Prize for the best paper presented at the 2023 WAPOR-LA conference under its previous title “Who Votes for Populists in Latin America? It Depends upon If the Populist Is the President.”