The study of politics in Latin America has become an important part of Comparative Politics, the field in Political Science dedicated to the study of politics around the world. It can be defined in terms of the community of scholars located in various countries who do research on Latin America, the fund of knowledge built over time, a set of research questions, and a set of procedures used to address these questions. In brief, this field of research encompasses the scholars who engage in research on Latin America and the scholarship they produce.

The authors of “A Unified Canon? Latin American Graduate Training in Comparative Politics” focus on who is producing knowledge and argue in favor of a one-way flow of knowledge from scholars in the Global North writing in English to those in the Global South writing in other languages. They frame the choice faced by scholars in Latin America as one between “North Americanization and parochialism.” They characterize research produced by Latin American scholars writing on their own countries in Spanish and Portuguese as largely “parochial.” And they imply that the ideas presented in “mainstream” texts written largely by scholars from the North and published in English should be “imported” by universities in Latin America. Indeed, only these “mainstream” materials are seen as meeting “a high standard of excellence.”

Setting aside methodological matters about the data presented in “A Unified Canon?” this commentary questions the granting of epistemological privilege to the research on Latin America produced by scholars based in the United States and published in English. It also holds that a consideration of other issues, such as what knowledge scholars seek to produce and how they go about producing knowledge, leads to a more nuanced view of the contributions made by the community of scholars who study Latin America and hence of what should be treated as materials worthy of being read and assigned in courses. In short, a serious and respectful discussion about how to foster the growth of knowledge about Latin American politics should not assume that some scholarship is epistemologically superior and must address these other central matters.

More specifically, this text disputes the blanket recommendation that Latin American universities should be modernized by giving a more central role to “mainstream” texts produced in the United States. A review of research patterns reveals strengths and weaknesses in the scholarship on Latin America produced both in the United States and Latin America. Thus, what is needed is a two-way flow of knowledge between scholars located in and outside of Latin America that recognizes their respective strengths. Additionally, some weaknesses of research in both the United States and Latin America will only be overcome through innovations that break with engrained research practices in both the United States and Latin America.

Scholars, Location and Language: Dismissing Claims About Epistemological Privilege

Since the 1990s, an important trend in some Latin American universities has been a decided push to modernize by emulating practices in Political Science and other social science disciplines in what are considered the most advanced universities in the world, those in the wealthy West and especially the United States. Further, this vision has been implemented through various measures. Departments of Political Science in Latin America have trained their students in the latest ideas in the Global North and encouraged them to get a PhD abroad, with a preference for the United States. They have hired Latin Americans and non-Latin Americans with PhDs from the Global North. They have offered incentives to their professors to publish in English, whether articles in peer-reviewed journals or books with university presses and other outlets. In general, scholars in Latin America have been encouraged to cultivate networks that provide opportunities for interacting with and learning from their peers in the Global North.

A different position has been articulated by scholars who have concerns about the impact of Eurocentrism and Anglocentricism on the social sciences in Latin America. These scholars provide a far-reaching critique of Eurocentric knowledge and the “coloniality of knowledge” (Lander Reference Lander2000). They reject the view that European or US ideas should be seen as more advanced and claim that such ideas underappreciate lo latinoamericano, that which is specifically Latin American. They question the treatment of the European or the US version of modernity as universal, and advocate for “another modernity” (Quijano Reference Quijano2000, 215). Furthermore, they promote the adoption of “epistemologies of the South” to counter the “hegemonic epistemologies in the West” (Santos Reference Santos2009, Reference Santos2016).

This framing of options is influential. And its persistence has a rationale. Indeed, both of these positions have some merit. But they both essentially rest on the same, more or less explicitly formulated, assumption: that research done in a certain location or from a certain perspective should be assigned epistemological privilege. And such a view is problematic and a hindrance to a respectful relationship among scholars in the large community working on Latin America and to the growth of knowledge about Latin America.

It is critical to underscore that academics in Latin America have authored important works in Spanish or Portuguese, and that some of these works never appeared in print in English. For example, Cardoso and Faletto’s ([1969] Reference Cardoso and Faletto1979) classic Dependency and Development in Latin America was originally published in Spanish and only appeared in English ten years later. O’Donnell’s ([1982] Reference O’Donnell1988) Bureaucratic Authoritarianism: Argentina, 1966–1973, in Comparative Perspective was initially published in Spanish and six years later in English. Also Jelin’s ([2002] Reference Jelin2003) State Repression and the Labors of Memory was first published in Spanish and appeared in English shortly thereafter. But some texts have never been published in English. Cotler’s (Reference Cotler1978) Clases, estado y nación en el Perú, and Torres Rivas’s (Reference Torres Rivas2011) Revoluciones sin cambios revolucionarios, were written in Spanish and are not available in English. Dos Santos’s (Reference Santos and Guilherme1979) Cidadania e justiça is only accessible in Portuguese. In fact, a considerable body of research written in Spanish and Portuguese exemplifies the significant contributions of Latin American scholars to the study of Latin American politics (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2007; Munck Reference Munck2023, 26–31).

Thus, not all the good ideas about Latin America are produced in the United States and written in English. Scholars based outside the Global North have displayed great creativity. And the claim that works written by authors from a Latin American country in the language of that country and about that country are somehow more parochial and less valuable than research produced in the United States is simply not credible.

Yet it is also indispensable to recognize the worth of research done in the United States. Universities in the United States are well-established and have considerable resources. They provide a stable environment within which academics can conduct research. They have, since the 1960s, given importance to the study of Latin America. Moreover, they are open institutions, which have been willing to offer jobs to Latin Americans. And in this setting important contributions to knowledge about Latin American politics and society have been made.

To give but a few examples, the contributions of US-born academics are well demonstrated by the works of Stepan (Reference Stepan1971) on the military in Brazil, the Colliers (Reference Collier and Collier1991) on labor and political regimes in eight Latin American countries, and Stokes (Reference Stokes2005) on clientelism in Argentina. Moreover, the same can be said about publications by scholars born in Latin America and employed by US universities, such as the books by Centeno (Reference Centeno2002) and Mazzuca (Reference Mazzuca2021) on the state in Latin America and by Magaloni (Reference Magaloni2006) on hegemonic party survival in Mexico. In brief, many academics in the United States dedicate considerable efforts to learning about Latin America. Some are true friends of Latin America. Others are Latin Americans. And it would be reckless to dismiss the value of a large literature simply because it was produced within US universities or was published in English.

In short, the social context of knowledge production matters. Nonetheless, broad claims assigning epistemological privilege to research produced in certain locations and languages are questionable. The Global North should not be assigned epistemological privilege. Neither should the Global South.

Scholars and Scholarship: Seeking Deep Answers to Big Questions

Moving beyond sweeping and unjustified claims about who has a cognitive advantage in discussions about Latin America, and considering what knowledge about Latin America scholars seek to produce and how researchers seek to generate knowledge about Latin America, a more nuanced picture emerges. Scholarship on Latin America produced in the United States and in Latin America has strengths and weaknesses. Scholars in the United States and Latin America have much to learn from each other. Also, in some areas, practices in both the United States and Latin America have shortcomings, such that new ways of producing knowledge must be sought.

Asking the Big Questions

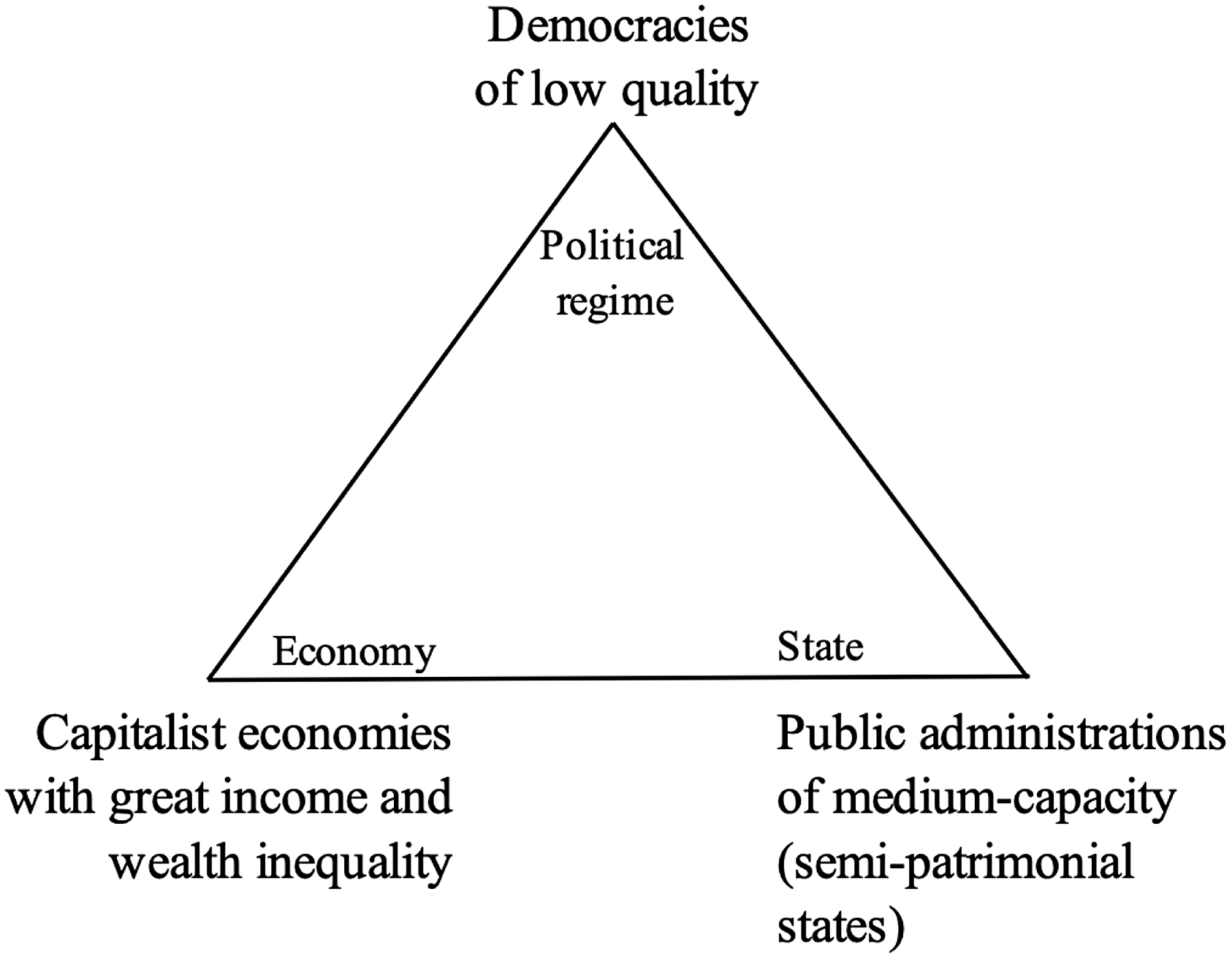

All research on Latin America addresses some kind of question or questions. But all questions are not equally important. In fact, considering only contemporary Latin American politics and without claiming to formulate a complete research agenda for this period, a case can be made that a core set of questions about contemporary Latin America revolves around what could be called the Latin American triangle (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Latin American Triangle, Twenty-first Century.

This triangle places the focus on three macro structures—the political regime, the state, and the economy—that shape the quality of life of inhabitants in the region. It highlights three modal characteristics of Latin American countries in the twenty-first century that make up a distinctive configuration not found in any other world region: regimes that are democratic but have many problems related to the quality of democracy, states that are semi-patrimonial and hence have a medium level of capacity, and economies that are capitalist and marked by high levels of inequality. And it draws attention to central matters in the study of contemporary Latin American politics. In a nutshell, to understand present-day Latin American politics we must be able to explain the origin, functioning, and stability of these three macro structures.

Answering any of these big questions (e.g., Why does Latin America mainly have democracies of low quality?)—let alone all of the questions related to the Latin American triangle—is by no means an easy task. But these questions must be asked. The history of the social sciences does not support the view that tackling small, easy questions will eventually provide an answer to big, tough questions. Rather, progress in knowledge requires confronting hard problems. And this is why the distinction between question- or problem-driven research vs. methods-driven research is of import.

A standard refrain in the US academia these days is that researchers need to be aware of the methodological difficulties involved in making causal inferences. And this call has a beneficial aspect. The increasingly stringent standards required to make causal claims has served to avoid and dispel erroneous explanations. However, this concern has also led to a narrowing of the questions that researchers are willing to ask. In effect, some methodologists argue that researchers should only focus on questions about which causal inferences can be made and express skepticism regarding research on precisely the kinds of questions at the heart of the research agenda formulated above.

Thus, the development of knowledge about contemporary Latin American politics requires that the tendency in US universities to favor methods-driven research be checked. Researchers need to be encouraged and provided with suitable incentives to address big questions. Certainly senior scholars should take advantage of their job security to take risks, even if some research projects might not pay off. Journals should provide a space for exploratory research. But, fundamentally, researchers should avoid putting the cart (matters of methods) ahead of the horse (the core research questions that ought to be addressed). And, in this regard, the greater engagement of Latin American scholars with the realities of their region may be a significant benefit—if anything else it serves as a constant reminder of the real-world problems that call for scholarly research.

Adopting a Scientific Approach That Values Theory

Turning to the task of answering big questions, one broad issue concerns the use of a scientific approach and the conception of science that is embraced. On this matter, it is tempting to assume that there is a convincing rationale for following the lead of US universities. In Latin American universities, there is a definite tendency to question the idea of objective knowledge. In fact, many academics in Latin America see the production of knowledge about societies as an inescapably political process and dispute the distinction between science and ideology. In the United States, in contrast, although similar views are held by some, the idea of the social sciences as sciences is more firmly rooted. Yet, questions can also be raised about the US model of social science.

The problem, in essence, is that academics in the United States are for the most part empiricists, who tend to treat all problems of knowledge as empirical problems, that is, as problems solvable through empirical research. Therefore, they place an inordinate emphasis on data and the analysis of data. Indeed, political scientists in the United States generally pay scant attention to theory or engage, at most, in theorizing that only considers observables or what is called by some phenomenological theorizing (Bunge Reference Bunge2006). Relatedly, US political scientists have little sense of the metatheoretical ideas they draw on, frequently confuse a theory with a hypotheses, and fail to treat research on theory as valuable in itself.

This state of affairs is seen by many in a positive light. But an empiricist conception of science has costs. Deep answers to the big questions related to the Latin American triangle—or to other big questions—will not be derived inductively, from data. All that empirical research can uncover is empirical patterns. Yet, to refine the questions posed above, considerable conceptual work is needed. Further, to orient empirical research, theoretical frameworks and explanatory arguments need to be elaborated, scrutinized and debated. Finally, even to assess the theoretical implications of empirical tests of hypotheses, it is imperative to first specify how a theory interfaces with facts. And these core tasks are disregarded when scholars treat empirical research as the main or only path to knowledge.

Therefore, concerning this issue, neither Latin American nor US universities currently offer a model to follow. What is needed is a commitment to science as the pursuit of truth about objective facts and a notion of social science that comprises both conceptual-theoretical and empirical research. Indeed, in this sense, progress in knowledge on Latin American politics requires a significant break with entrenched practices in both the United States and Latin America.

Using Comparison to Correct Eurocentrism and the Pitfall of the Best-Known Cases

Lastly—and it is important to note that no claim is made here to be offering a comprehensive discussion of relevant issues—a point about theorizing that is the focus of discussion in Latin America deserves consideration. It is fairly common for Latin American scholars to criticize at least some literature produced in the Global North for being Eurocentric—sometimes the focus is placed, more narrowly, on Anglocentricism. And the rather polemical nature of discussions about Eurocentrism notwithstanding, it is essential to recognize the need to correct Eurocentrism.

Eurocentrism, understood here as the treatment of European history as universal history, has strong roots and remains alive. A Eurocentric view of Latin America was initially proposed by evolutionary theorists in Europe in the nineteenth century. It was revived by modernization theorists in the United States in the 1950s and again in the 1990s. What is more, it continues to influence some research on Latin America produced in the United States, in more or less subtle ways.

Moreover, Eurocentrism is associated with some pernicious, slippery ways of thinking about Latin America. At times, a Eurocentric perspective is used to offer a flawed portrayal of Latin America as a “backward” instance of successful European cases. Indeed, such a characterization relies on biased criteria and/or a partial reading of history. Furthermore, even setting aside these problems, this image creates the false impression that the only difference between Latin America and Europe is that Latin America is at a stage of development Europe moved past decades or centuries earlier. Other times, a Eurocentric vantage point leads to an erroneous depiction of Latin America as failing to make progress because it is different in a more significant way, having deviated from “the correct path” to success blazed by Europe. In effect, this argument misleadingly assumes that there is only one path to success or one way of doing things—the European one.

Thus, a wholesale emulation of US research by Latin American scholars, that is not attentive to this problematic strain of thinking in the Global North, would be a mistake. Rather, it is better to build on the long-standing critiques of Eurocentric thinking by Latin American researchers such as Cardoso and Faletto ([1969] Reference Cardoso and Faletto1979, xiv–xvii, 11, 16–17) and O’Donnell (Reference O’Donnell1996, 38–39; Reference O’Donnell2010, 183–84).

At the same time, it is crucial to go beyond denunciations of Eurocentrism and to use comparative research to solve the problems of Eurocentric thinking. It is imperative to compare Latin America to Europe—rather than to treat any dispassionate inquiry about Europe as suspect. More pointedly, it is key to theorize how both regions fit, as special cases, within a truly general theory, as illustrated by Touraine’s (Reference Touraine1989, 46–51) analysis of modes of development, Mazzuca’s (Reference Mazzuca2021, 4–8, 21–24, Ch. 1) research on types of state formation, and my own work with Mazzuca on paths to a high capacity democracy (Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2020). That is, scholarship on Latin America should not only criticize Eurocentrism but also seek to correct the flaws of a Eurocentric view of world history and deuniversalize Europe.

It is also important to recognize that Latin American scholars are not immune to a mistake that is similar to the one they criticize, with reason, in the work on some scholars from the Global North. That is, if Eurocentrism errs in treating some cases as a basis for claims about the universe of cases, Latin American scholars have used some well-known Latin American cases to make assertions about the region as a whole. Indeed, this is precisely why Cotler (Reference Cotler and Collier1979, 255–56) warned about the dangers of extrapolating explanations about Southern Cone cases, and especially Brazil and Argentina, to other parts of Latin America, such as the Andean region. Similarly, this is why Torres Rivas (Reference Torres Rivas2023, 144) argued that analyses of South America that were assumed to hold throughout Latin America overlooked the distinctiveness of Central America. In other words, it is crucial to appreciate that the misuse of the best-known cases is not a distinctive feature of what Santos (Reference Santos2016, 42) calls the “hegemonic epistemologies in the West.”

In sum, critics of the “coloniality of knowledge” (Lander Reference Lander2000) have a point. But the solution to this problem is not the adoption of “epistemologies of the South” (Santos Reference Santos2016). Rather, the solution is to theorize the experience of different societies in such a way as to distinguish between what is general and what is specific of Europe, the United States and Latin America as well as to discriminate between what is general and specific within Latin America. And, to do this, broad comparative thinking is called for. That is, while acknowledging the value of studies of single countries—as noted above—the need for broad-ranging comparative research must be recognized.

Conclusions

Academics in the United States have a lot to offer to the study of politics in Latin America. Thus, scholars in Latin America would be remiss if they turned their back on some knowledge simply because it was produced outside of the region. However, the suggestion that research about Latin America generated in the Global North should be imported indiscriminately into Latin America does not recognize the problematic aspects of this literature.

It is also fundamental to recognize the value of research produced in Latin America in Spanish and Portuguese. Academics in the United States should do more to read, absorb, and cite the writings of Latin American authors. They should also collaborate more as equals with their Latin American peers. Indeed, the Comparative Politics of Latin America would benefit from more of a two-way flow of knowledge between scholars in the North and the South.

Still, an even more radical revision of current research practices is called for to foster the growth of knowledge about politics in Latin America. Some views about what constitutes social science research in the United States hamper the production of knowledge about Latin American politics. The same can be said about some outlooks on social science knowledge in Latin America. What is needed, then, is a set of innovations in research that will give greater centrality to the pursuit of deep answers to big questions.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.