The study of mergers and splits has been of great importance to historical linguistics, dialectology, and sociolinguistics. While phonetic mergers have been well studied, splits, which are the reversal of previously merged phones, remain a relatively underexplored topic. The possibility of the split of a merger is disputed in the literature under the conventions of Garde's Principle, which holds that once a merger has occurred, it will persist, and Herzog's Principle, which states that mergers expand at the expense of distinctions (Labov, Reference Labov1994). However, a growing number of studies demonstrate that, with adequate dialect contact, a split may occur (Johnson, Reference Johnson2010; Maguire, Reference Maguire2008; Maguire, Clark, & Watson, Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013; Nycz, Reference Nycz2011, Reference Nycz2013; Trudgill, Schreier, Long, & Williams, Reference Trudgill, Schreier, Long and Williams2003; Yao & Chang, Reference Yao and Chang2016). Nevertheless, the variationist literature informing theories on mergers and splits is biased towards the phonology of English, specifically vowels (Gordon, Reference Gordon, Chambers and Schilling2013:204, Reference Gordon, Honeybone and Salmons2015:174). Thus, the current study analyzes a consonant split in Andalusian Spanish.

In the last several decades, sociolinguists in Andalusia have been chronicling the ongoing split of the ceceo (and seseo) merger into distinción. Distinción is the direct phoneme-to-grapheme realization of (apico-)alveolar /s/ for <s> and interdental /θ/ for <z,ci,ce>, while ceceo is the voiceless dental fricative [s̪θ] merger for <s> and <z,ci,ce>. The findings that several communities have shifted from ceceo to distinción have led scholars to suggest that the demerger of ceceo presents an exception to Garde's and Herzog's Principles (Moya Corral & Sosiński, Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015:35; Regan, Reference Regan2017a:152, Reference Regan2017b:259; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda2001:126; Villena & Vida Castro, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Vida Castro, Villena Ponsoda and Ávila Muñoz2012:117–18). To further examine these claims, the current study provides the first large-scale sub-segmental analysis of Andalusian coronal fricative variation based on 80 Western Andalusian speakers from the city of Huelva and the town of Lepe. The aims of the study were fivefold: (i) to assess the status of the centuries-old ceceo merger as a complete or near-merger; (ii) to determine if a demerger is in progress in Huelva and/or Lepe; (iii) to investigate which linguistic and extralinguistic factors promote the demerger of ceceo into distinción; (iv) to compare an urban speech community to a neighboring rural speech community to assess the extent of the change; and, (v) building on Lasarte Cervantes (Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010), to provide a preliminary acoustic profile of ceceo and distinción.

BACKGROUND

Mergers, near-mergers, and splits

Merger reversal is disputed in the literature under the convention of Garde's Principle (Labov, Reference Labov1994:311). Specifically, Garde (Reference Garde1961:38–9) stated, “Innovations can create mergers, but cannot reverse them” (Labov's translation, Reference Labov1994:311). Labov suggested,

The impossibility of reversal established by Garde's Principle is not a deduction, but rests on empirical observations. Garde's Principle does not say that it is theoretically impossible for a person to reverse a merger accurately. It is based on the empirical observation that at no known time in the history of the language has such a reversal been accomplished by enough individualFootnote 1 speakers to restore two original word classes for a given language as a whole (Reference Labov1994:312).

Another major convention regarding mergers is Herzog's Principle, which states, “mergers expand at the expense of distinctions” (Herzog, Reference Herzog1965; Labov, Reference Labov1994:313). This receives empirical support through the Atlas of North American English (Labov, Ash, & Boberg, Reference Labov, Ash and Boberg2006) in which mergers such as cot-caught have expanded over many regions.

Most linguists agree that a merger will not split for language-internal reasons alone, but rather by language-external motivations such as dialect contact or social pressures initiated by education or mass media (Hickey, Reference Hickey, Kay and Wotherspoon2004:134–35; Labov, Reference Labov1994:343; Thomas, Reference Thomas and Brown2006:490). The split of a near-merger (Labov, Reference Labov and Heilmann1975, Reference Labov1994; Labov, Karen, & Miller, Reference Labov, Karen and Miller1991; Labov, Yaeger, & Steiner, Reference Labov, Yaeger and Steiner1972), remains compatible with Garde's Principle, as there was never a complete phonetic neutralization,Footnote 2 but rather a subtle acoustic differenceFootnote 3 between phonemes. However, even when scholars take care to distinguish between near-mergers and complete mergers (Bullock & Nichols, Reference Bullock, Nichols, Perpiñán, Heap, Moreno-Villamar and Soto-Corominas2017; Di Paolo & Faber, Reference Di Paolo and Faber1990; Faber & Di Paolo, Reference Faber and Di Paolo1995; Nunberg, Reference Nunberg and Labov1980; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1974), there still seems to be evidence for the split of a complete merger due to dialect contact. Specifically, studies have documented the split of the cot-caught merger among Canadians in NYC (Nycz, Reference Nycz2011, Reference Nycz2013), cot-caught merger among mobile New Englanders (Johnson, Reference Johnson2010), /w/-/v/ merger in lesser-known Englishes (Trudgill et al., Reference Trudgill, Schreier, Long and Williams2003), nurse-north merger in Tyneside English (Maguire, Reference Maguire2008; Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013; Watt, Reference Watt, Paradis, Vincent, Deshaies and Laforest1998), and /ɛ/ merger into /ɛ/-/e/ in Shanghainese due to language contact with Mandarin (Yao & Chang, Reference Yao and Chang2016).

Maguire et al. (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:234) posited that Labov's claim that no split has occurred at the level of a language is too strong (also Nycz, Reference Nycz2013:328) and that, instead of speaking about languages, one should speak about individual phonological systems, as intra- and interspeaker variability impacts an individual's phonological knowledge. The irreversibility of mergers becomes more susceptible to exceptions in a community constituted by individuals with a merger, others a split, and others in between the two norms. Maguire et al. (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013) argued that such is the case in situations of “swamping” (Thomas, Reference Thomas and Brown2006:490), where a merged community is inundated with migrant speakersFootnote 4 with the phonemic distinction, resulting in exposure to grammars with and without the merger. Swamping enables the coexistence of the one-phoneme and two-phoneme systems in the same community with the prestige of the latter allowing for the gradual loss of the former. Consequently, Herzog's Principle “may be compromised when the merger involved is, or becomes heavily stigmatized” (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:235).

European societal changes and dialect contact

In the twentieth century, large-scale societal changes throughout Europe increased dialect contact, which has led to the levelling of local traditional dialectal features in favor of regional or national features (Auer & Hinskens, Reference Auer and Hinskens1996; Hinskens, Auer, & Kerswill, Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005; Mattheier, Reference Mattheier2000; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1986). The transition from agrarian, to industrial, to a postindustrial society has increased urbanization, mobility, dialect contact, mass media, and educational attainment (Auer & Hinskens, Reference Auer and Hinskens1996:4; Hinskens et al., Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005:23–24). The change from multigenerational to nuclear family living has reduced the dialect input from grandparents to grandchildren (Hinskens et al., Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005). These changes have catalyzed dialect levelling of traditional dialectal features throughout Europe, Spain included.

Andalusian coronal fricatives

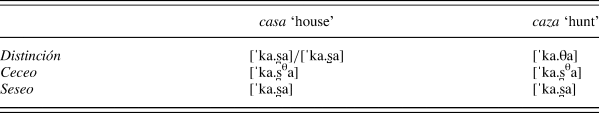

Andalusian Spanish presents dialectal variation in the pronunciation of the graphemes <s>, <z>, <ci>, and <ce>, variously realized as [s̪], [θ], and [s̪θ]. These phonetic norms are the result of the reduction of four medieval Spanish sibilants: /ts/, /dz/, /s/, /z/ (Penny, Reference Penny2000:118–19, Reference Penny2002:124–5). In Castilian Spanish, these sibilants were reduced to the voiceless interdental fricative /θ/ and the voiceless apicoalveolar fricative /s̺/, known as distinción, giving rise to minimal pairs such as casa-caza ‘house-hunt.’ Distinción reflects a direct grapheme-to-phoneme correlation of /s/ for <s> and /θ/ for <z,ci,ce> (Table 1). In Andalusian Spanish, however, the four medieval sibilants merged into dental /s̪/ (Penny, Reference Penny2000:118, Reference Penny2002:125). This phonemic merger is phonetically realized as ceceo or seseo. Ceceo is realized as a voiceless dental fricative, represented as [θ̪], [s̪θ],Footnote 5 or [θs] as it is perceptually similar to, but not quite as fronted as, [θ] (Hualde, Reference Hualde2005:153; Penny, Reference Penny2000:118, Reference Penny2002:125). Seseo is realized as an (predorso-)alveolar [s̪] (Hualde, Reference Hualde2005:153; Penny, Reference Penny2000:118). Most Andalusian speakers with distinción realize an alveolar [s̪] as opposed to the apicoalveolar Castilian [s̺] (Narbona, Cano, & Morillo, Reference Narbona, Cano and Morillo1998:156). Distinción is not native to mid- and southern Andalusia but has been brought by dialect contact through rural emigration, migration of northern Spaniards to Andalusia, and increased education and mass media (Narbona et al., Reference Narbona, Cano and Morillo1998:155–60).

Table 1. Minimal pairs per idealized phonic norm

Traditional dialectology works (Alvar, Llorente, Salvador, & Mondéjar, Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973,Footnote 6 Navarro Tomás, Espinosa, & Rodríguez Castellano, Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa and Rodríguez-Castellano1933) demonstrated that ceceo and seseo dominated most of Andalusia through the mid-twentieth century. Beginning in the 1980s, sociolinguistic studies in Eastern Andalusia in Granada (Martínez & Moya Corral, Reference Moya Corral and Mattheier2000; Melguizo Moreno, Reference Melguizo Moreno2007, Reference Melguizo Moreno2009; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Moya Corral & Sosiński, Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015; Salvador, Reference Salvador1980) and Málaga (Ávila, Reference Ávila1994; Lasarte Cervantes, Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda1996, Reference Villena Ponsoda2001, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Moya Corral and Sosiński2007; Villena, Sánchez, & Ávila, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Sánchez Sáez and Ávila Muñoz1995; Villena & Requena, Reference Villena Ponsoda and Requena Santos1996) demonstrated a shift from ceceo (and seseo) to distinción. Contrastingly, studies in Western Andalusia in Sevilla (Carbonero, Reference Carbonero, Lamíquiz and Carbonero1982, Reference Carbonero1985; Dalbor, Reference Dalbor1980; Lamíquiz & Carbonero, Reference Lamíquiz and Carbonero1987; Sawoff, Reference Sawoff1980), Jerez (Carbonero, Álvarez, Casas, & Gutiérrez, Reference Carbonero, Álvarez, Casas and Gutiérrez1992), and Lepe (Mendoza Abreu, Reference Mendoza Abreu1985) revealed the maintenance of ceceo and seseo. These differences, in addition to findings from other linguistic variables, led scholars to posit that Eastern Andalusian Spanish is structurally closer to Castilian Spanish than Western Andalusian Spanish (Hernández-Campoy & Villena, Reference Hernández-Campoy and Villena Ponsoda2009; Moya Corral & Sosiński, Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda1996, Reference Villena Ponsoda2008; Villena & Ávila, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Ávila Muñoz, Braunmüller, Höder and Kühl2014; Villena & Vida Castro, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Vida Castro, Villena Ponsoda and Ávila Muñoz2012).

Recent studies in Western Andalusia, however, in JerezFootnote 7 (García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008), Huelva (Regan, Reference Regan2015, Reference Regan2017a, Reference Regan2017b), and peripheral towns around Huelva (de las Heras, Bardallo, Castrillo, Gallego, Padilla, Romero, Torrejón, & Vacas, Reference de las Heras, Bardallo, Castrillo, Gallego, Padilla, Romero, Torrejón and Vacas1996) suggest that ceceo is demerging into distinción. Studies in Sevilla (Gylfadottir, Reference Gylfadottir2018; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017) also suggest that seseo is demerging into distinción. The leaders of change are younger generations, those with more formal education, and women. All previous studies of ceceo used impressionistic analysis, with a few exceptions of acoustic analysis (Lasarte Cervantes, Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Regan, Reference Regan2015, Reference Regan2017b).

The speech communities: Huelva and Lepe

The city of Huelva has experienced significant societal changes since the 1950s when ceceo was the dominant norm (Alvar et al., Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973). The major catalyst for these changes was in 1964 when Dictator Franco's regime made Huelva home to one of Spain's largest industrial plants. Immigrants came from all over the province, especially from la sierra de Aracena (the north of the province where distinción is the norm), and from other parts of Spain, for employment in the factories (Feria Toribio, Reference Feria Toribio1994; Martínez Chacón, Reference Martínez Chacón1992; Ruiz García, Reference Ruiz García2001). Morillo-Velarde (Reference Morillo-Velarde, Narbona and Ropero1997:209) posited that this immigration from the north of the province brought distinción speakers into the city. Huelva's population increased from 83,648 to 147,808 between 1950 and 2011 (INEFootnote 8). Historically, Huelva's economy was based on agriculture and fishing, then was industrialized but has become increasingly service-oriented, as several factories have closed. In 2011 (INE), 6.5% of working Huelvans were employed in agriculture, 19.1% in manufacturing/construction, and 74.5% in service. Educational attainment of Huelva's inhabitants increased dramatically between 1950 (37.9% no studies; 60.1% primary; 1.3% secondary/professional; 0.7% university) and 2011 (9.9% no studies; 12.7% primary; 57.5% secondary/professional; 20% university).

Lepe, 33 km west of Huelva, never underwent industrialization, but has experienced other changes since the 1950s and 1980s when ceceo was the dominant norm (Alvar et al., Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973; Mendoza Abreu, Reference Mendoza Abreu1985). Lepe maintained its population due to the predominance of fishing and agriculture (Feria Toribio, Reference Feria Toribio1994:190), increasing from 9,285 to 26,538 between 1950 and 2011 (IECA, 2016). Despite this growth, Lepe still maintains its small town identity. While Lepe has retained its agricultural sector, it is increasingly relying on service and professional occupations and has essentially lost its fishing industry. In 2011 (INE), 29.7% of working Leperos were employed in agriculture, 16.3% in manufacturing/construction, and 54% in service. Educational attainment of Lepe's inhabitants increased dramatically between 1960 (78.2% no studies; 21% primary; 0.7% secondary/professional; 0.1% university) and 2011 (14.3% no studies; 20.7% primary; 61.8% secondary/professional; 3.2% university).

Finally, mass media began in 1956 with television broadcasting throughout Spain (Palacio, Reference Palacio2001; Rueda & Chicarro, Reference Rueda and Chicarro2006; Stewart, Reference Stewart1999), resulting in increased exposure to speakers with distinción.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

First, is there evidence that there was a complete merger or a near-merger? As dialectology studies in Huelva and Lepe (Alvar et al., Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973; Mendoza Abreu, Reference Mendoza Abreu1985; Navarro Tomás et al., Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa and Rodríguez-Castellano1933) reported a merger based on impressionistic analyses, there is no reason to assume a priori that ceceo is a complete or a near-merger. Given the lack of acoustic studies, there is no formal hypothesis.

Second, is there phonetic evidence that the split of the ceceo merger into distinción is underway in Huelva and/or Lepe? Regan's (Reference Regan2017a) auditory analysis of 38 sociolinguistic interviews from 2013 and 2014 provided segmental evidence of a demerger, while Regan's (Reference Regan2015) pilot subsegmental study of 15 sociolinguistic interviews in and around Huelva indicated that some speakers demonstrate differences between graphemes in intensity (dB). Building on these studies, it is hypothesized that there is a phonetic demerger from ceceo into distinción, that is, two separate phonemes of /s/ and /θ/.

Third, what social and linguistic factors contribute most to the probability that a speaker will manifest a split (distinción) rather than a merger (ceceo)? In terms of gender, age, and education, based on previous studies (Ávila, Reference Ávila1994; García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Melguizo Moreno, Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda1996, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Moya Corral and Sosiński2007; Villena & Requena, Reference Villena Ponsoda and Requena Santos1996; inter alia), it is hypothesized that those most likely to favor distinción will be women, younger speakers, and those with more formal education. In line with the notion of the linguistic market (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1991; Bourdieu & Boltanski, Reference Bourdieu and Boltanski1975; Sankoff & Laberge, Reference Sankoff, Laberge and Sankoff1978), it is hypothesized that those with professional and service occupations will demonstrate more evidence of distinción than those with manual occupations. As the shift toward distinción is a change from above (Labov, Reference Labov1994:78), it is hypothesized that wordlists will elicit more distinción than reading passage data.

With respect to linguistic factors, following García-Amaya (Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008), Regan (Reference Regan2017a), and Villena and Requena (Reference Villena Ponsoda and Requena Santos1996), it is hypothesized that orthography will be a strong main effect, with significant acoustic differences found between word sets with <s> and <z,ci,ce>. Although previous impressionistic studies have not found syllable stress to be significant, it was included to test whether tonic syllables favor distinción more than atonic syllables given their acoustic prominence. Finally, as assimilation effects have been found in words with two fricatives (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Moya Corral and Sosiński2007), it is hypothesized that words with two different orthographic environments will produce less acoustic distance between phonemes compared to words with two same orthographic environments.

Fourth, does rural Lepe demonstrate differences in the linguistic change as compared to urban Huelva? As Britain (Reference Britain and Al-Wer2009, Reference Britain, Auer and Schmidt2010, Reference Britain, Hansen, Schwarz, Stoeckle and Streck2012) noted, although many assume that dialect contact and linguistic change is more common in urban areas, this should not be assumed a priori. Instead, Britain proposed that variationists focus on causal social processes of change, regardless of environment. Thus, it is hypothesized that similar social factors will influence both communities, although perhaps at different rates of change.

Finally, what are the acoustic properties of distinción and ceceo? Based on Lasarte Cervantes’ (Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010) findings, it is hypothesized that mean intensity (dB) will serve as a valid acoustic measure with distinción having higher mean intensity for [s] than [θ] and with intermediate ceceo [s̪θ] realizations.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Participants

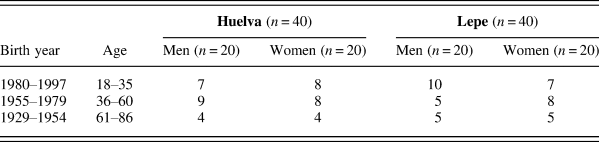

This apparent time study (Labov, Reference Labov1994:45) was conducted during summer 2015 and 2016. Participants were recruited through the author's social networks in Huelva and Lepe and subsequent snowball sampling of “friends of friends” (Milroy, Reference Milroy1980:453). Eighty participants were selected from a larger sample in order to balance populations based on occupational background, origin (40 Huelva, 40 Lepe), gender (40 men, 40 women), and age (overall, range: 18–86, M: 43.7, SD: 17.2; Huelva, range: 18–70, M: 43.03, SD: 16.03; Lepe, range: 18–86, M: 44.4, SD: 18.48) (online Appendix I for demographics). Although age is treated as continuous in the analysis in order to examine a gradient apparent time change, Table 2 presents binned categories of age and birth year by origin and gender.

Table 2. Speakers by origin, birth year, age (in 2015), and gender

Materials & Procedure

Data collection consisted of an informal sociolinguistic interview (Labov, Reference Labov1972:79–80), a reading passage, a wordlist, and metalinguistic and demographic questions, in that order; only the passage and list are analyzed here. Recordings were conducted by the author in quiet places such as the interviewees' homes, the Universidad de Huelva, and offices at Lepe's senior center or municipal theater. Participants were recorded with a solid-state digital recorder Marantz PMD660 (digitized at 44.1kHz, 16-bit sampling rate) wearing a Shure WH20XLR Headworn Dynamic Microphone. Two distinct levels of style were analyzed: reading passage and wordlist, following Labov's (Reference Labov1972:99) attention to speech approach. Participants read a one-page passage, constructed by the author, of 575 words with 170 syllable-initial target tokens (97 <s>; 73 <z,ci,ce>) (see Regan, Reference Regan2017b:279). Only syllable-initial coronal fricatives were considered, as syllable coda are aspirated or elided in Western Andalusian Spanish (Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda2008). The passage focused on local rivalries, customs, foods, and lifestyles. It was designed to be informal, interesting, relatable, and enjoyable so that speakers would pay more attention to the themes than their speech. The wordlist included both minimal pair and nonminimal pair tokens that contained 86 syllable-initial target tokens (44 <s>; 42 <z,ci,ce>) as well as distractors (see Regan, Reference Regan2017b:281). Several words contained more than one token (i.e., gracioso ‘funny’). The author never asked participants to produce distinción nor if they were capable of producing distinción, but rather asked if they would be able to read the passage and wordlist. Two speakers were not able to read the passage, one due to limited literacy and the other due to not having their glasses during the recording. All were able to read the wordlist. Afterwards, interviewees orally responded to demographic questions.

Preprocessing of data

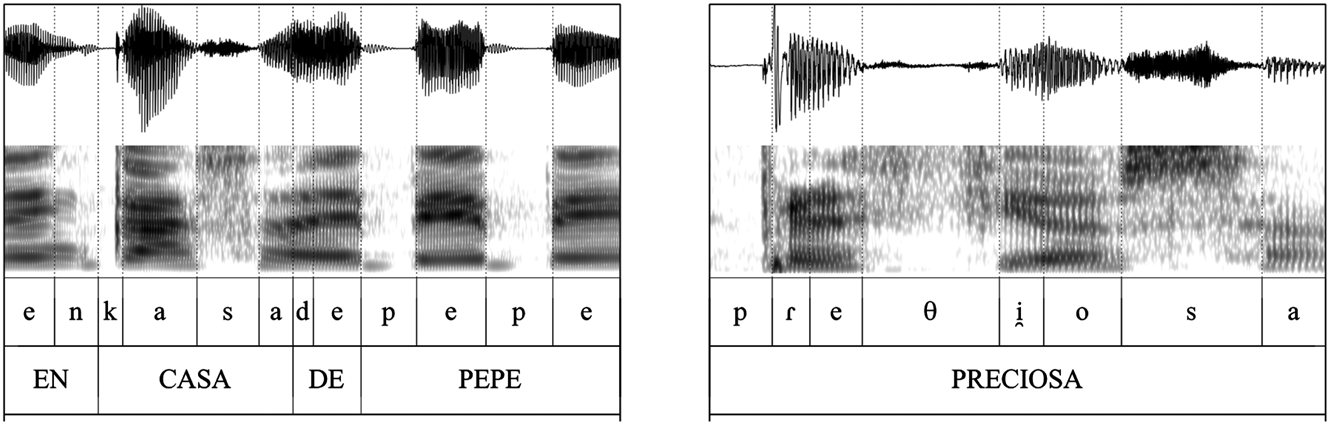

Several tokens were eliminated due to speakers’ misreading or skipping a word, or an overlap of external noise, resulting in a total of 19,420 tokens included in the analysis (passage: 12,651 tokens; wordlist: 6,769 tokens). The data were forced-aligned using FASE (Wilbanks, Reference Wilbanks2015). Figure 1 shows an example of an /s/ realization from the passage reading: en casa de Pepe ‘in Pepe's house.’ Once the alignments were made, each text grid fricative boundary was corrected by hand in Praat (Boersma & Weenink, Reference Boersma and Weenink2017) to assure that the fricatives were properly segmented. Specifically, following Jongman, Wayland, and Wong (Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000:1255), the fricative onset was marked at the point in which high frequency energy appears on the spectrogram and where aperiodic zero crossings increase dramatically. The fricative offset was marked at the end of the aperiodic noise prior to the rise of the following vowel's periodicity and intensity (dB).

Figure 1. Left: Example of /s/ segmentation in a forced-aligned textgrid; Right: Andalusian [θ] and [s̪] produced by 29-year-old Huelva woman with distinción.

Independent factors

Six social factors were included: gender, age (18–86), education, occupation, origin, and speech style. For education, participants were placed in the highest degree earned or actively completing. For occupation, speakers were divided into three categories: manual (fishermen, construction, factory, field workers); service (bartenders, cashiers, small store workers); professional (teachers, professors, lawyers, civil servants, nurses).

Three linguistic factors were included: orthography, syllable stress, and assimilation. Initially, preceding phonetic context and following vowel were considered. However, given the lack of Spanish words containing <z> + /u,o/, they were removed from analyses. Additionally, functionality, whether fricatives distinguished minimal pairs, was also considered, as phonological maintenance is increased when phonemes serve a functional load (Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Moya Corral and Sosiński2007; Wedel, Kaplan, & Jackson, Reference Wedel, Kaplan and Jackson2013). However, it was not significant and thus was removed from analyses. While orthography is related to education, it is placed with linguistic factors following previous studies. Assimilation refers to whether there is an additional coronal fricative in the same word. For example, tokens in cereza ‘cherry’ have the same orthographic environment (<z,ci,ce>); tokens in precioso ‘precious’ have different orthographic environments (<z,ci,ce> versus <s>); and, the token in Mazagón, a town near Huelva, has no additional fricative.

Dependent measures

An automated Praat script (Elvira-García, Reference Elvira-García2014) was used to measure all tokens. The script uses a Filter pass Hand band (1,000, 11,000, 100). For the spectral moments, the script creates an averaged power spectrum using the “to Ltas” function, in which spectral slices are subject to cepstral smoothing for Fast Fourier Transform analysis, in line with previous studies (Forrest, Weismer, Milenkovic, & Dougall, Reference Forrest, Weismer, Milenkovic and Dougall1988; Jesus & Shadle, Reference Jesus and Shadle2002; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Shadle, Reference Shadle, Cohn, Fougeron and Huffman2012). The script took the following acoustic measures: the four spectral moments (center of gravity (Hz), variance (Hz), skewness, kurtosis), spectral peak (Hz), mean intensity (dB), and duration (ms). Center of gravity (henceforth COG) is the mean of spectral energy (Ladefoged, Reference Ladefoged2003:156), a useful measure for coda /s/ (Erker, Reference Erker2010; File-Muriel & Brown, Reference File-Muriel and Brown2011). Variance (Hz) is the “range” of spectral energy (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000:1253). Skewness refers to the spectral tilt and kurtosis to the peakedness of the spectrum (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000:1253). The rationale for using several acoustic parameters is that previous studies on near-mergers have found that speakers have utilized a nonprimary acoustic parameter to maintain a subtle phonetic difference in phonemes (Bullock & Nichols, Reference Bullock, Nichols, Perpiñán, Heap, Moreno-Villamar and Soto-Corominas2017; Di Paolo & Faber, Reference Di Paolo and Faber1990). Figure 1 displays differences between [θ] and [s̪] in COG (spectrogram) and intensity (waveform).

In terms of spectralFootnote 9 parameters, /s/ has higher COG than /θ/, but /θ/ has higher variance (Hz) than /s/ (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Nissen & Fox, Reference Nissen and Fox2005); /s/ has greater negative skewnessFootnote 10 than /θ/ (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000), and, in general, spectral peak (Hz) is higher for /θ/ than /s/ (Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman, et al. Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Martínez Celdrán & Fernández Planas, Reference Martínez Celdrán and Fernández Planas2007). Findings for kurtosis are mixed, where Jongman et al. (Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000) found higher kurtosis for /s/ while Fox and Nissen (Reference Fox and Nissen2005) found higher kurtosis for /θ/. However, there are biological sex-related acoustic differences for spectral parameters. Specifically, women compared to men have higher COG (Flipsen, Shriberg, Weismer, Karlsson, & McSweeny, Reference Flipsen, Shriberg, Weismer, Karlsson and McSweeney1999; Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Haley, Seelinger, Callahan, Mandulak, & Zajac, Reference Haley, Seelinger, Callahan Mandulak and Zajac2010; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Maniwa, Jongman, & Wade, Reference Maniwa, Jongman and Wade2009), higher variance (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000), more negative skewness (Flipsen et al., Reference Flipsen, Shriberg, Weismer, Karlsson and McSweeney1999; Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000), and higher kurtosis (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000). Spectral peak is complicated as men and women do not differ for /θ/, but women have a higher spectral peak for /s/ than men, sometimes resulting in a higher spectral peak for /s/ than /θ/ for women (Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000). For the current study, each community has the same number of men and women, which helps to neutralize sex-based effects on spectral parameters. Additionally, the results section proposes a Demerger Index to normalize sex-related spectral differences.

In terms of amplitudinal parameters, /s/ has higher mean intensity (dB) than /θ/ for nonnormalized mean intensity (Behrens & Blumstein, Reference Behrens and Blumstein1988a, Reference Behrens and Blumstein1988b; Lasarte Cervantes, Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010; Strevens, Reference Strevens1960) and for relative or dynamic intensity (Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Martínez Celdrán & Fernández Planas, Reference Martínez Celdrán and Fernández Planas2007; Nissen & Fox, Reference Nissen and Fox2005; Shadle & Mair, Reference Shadle and Mair1996; Stevens, Reference Stevens and Fromkin1985). For the temporal parameter, /s/ has longer duration (ms) than /θ/ (Behrens & Blumstein, Reference Behrens and Blumstein1988a; Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000). There are no sex effects for intensity (Fox & Nissen, Reference Fox and Nissen2005; Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000; Koenig, Shadle, Preston, & Mooshammer, Reference Koenig, Shadle, Preston and Mooshammer2013) or duration (Jongman et al., Reference Jongman, Wayland and Wong2000).

Statistical analysis

For each dependent measure, a mixed effects linear regression model was run using the lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2014) packages in R (R Core Team, 2017), including all social and linguistic factors as fixed factors with speaker and word as random factors. Post hoc analyses were conducted with estimated marginal means, emmeans (Lenth, Singmann, Love, Buerkner, & Herve, Reference Lenth, Singmann, Love, Buerkner and Herve2018), in order to analyze categorical predictors with more than two levels. The data from all 80 participants was incorporated into these models for a total of 19,420 tokens. Within each model, nonsignificant independent variables were removed from subsequent models. Marginal R-squared (R2m) and conditional R-squared (R2c) values were obtained for each model in order to assess the goodness-of-fit of the variation per measure (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, Reference Nakagawa and Schielzeth2013). R2m conveys the amount of variation accounted for by the fixed factors alone, while R2c represents the amount of variation accounted for by both fixed and random effects. These models revealed the following values for each measure in descending order from best explanation of variation to least: COG (R2m: 0.390, R2c: 0.587), mean intensity (R2m: 0.328, R2c: 0.676), duration (R2m: 0.284, R2c: 0.565), skewness (R2m: 0.226, R2c: 0.405), variance (R2m: 0.221, R2c: 0.414), spectral peak (R2m: 0.184, R2c: 0.324), and kurtosis (R2m: 0.029, R2c: 0.180). As COG and mean intensity (henceforth MI) best explain the variation, only these models are presented. Paired Welch Two Sample t-tests with Bonferroni correction were used to analyze individual speaker differences for word sets with <s> and <z,ci,ce> for all seven measures. Finally, follow-up mixed effects linear regressions were run for COG and MI Demerger Indexes with social variables as fixed factors and speaker as a random factor. Images were created with ggplot2 (Wickham, Reference Wickham2013).

RESULTS

Community-wide analysis: COG and MI linear regressions

COG and MI regression tables display the emmeans (EMM), estimate, standard error (SE), t-value, number of tokens per level (n), and p-value. Positive estimates indicate a higher COG/MI compared to the reference value, while negative estimates indicate a lower COG/MI compared to the reference value. Given the importance of the direct grapheme-to-phoneme correspondence, only the main effect of orthography and the interaction of orthography with other fixed factors is discussed. The best-fit mixed effects linear regression model for COG is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of linear mixed effects regression model for COG, speaker and word as random factors; n = 19,420 (R2m: 0.390, R2c: 0.588). EMM = estimated marginal means

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001

The main effect of orthography indicates that <s> had a significantly higher COG than <z,ci,ce> (henceforth <z>) (p < 0.001). For the orthography by assimilation interaction, <s> had a higher COG than <z> for different additional fricative (p < 0.001), for no additional fricative (p < 0.001), and for same additional fricative (p < 0.001). For <s>, different had a lower COG than no additional fricative (p < .05) and same (p < 0.05). No other differences were significant. The interaction indicates that words with two different orthographic environments have a smaller COG difference between phonemes as compared to words with no additional fricatives or words with the same fricative environment (Figure 2).

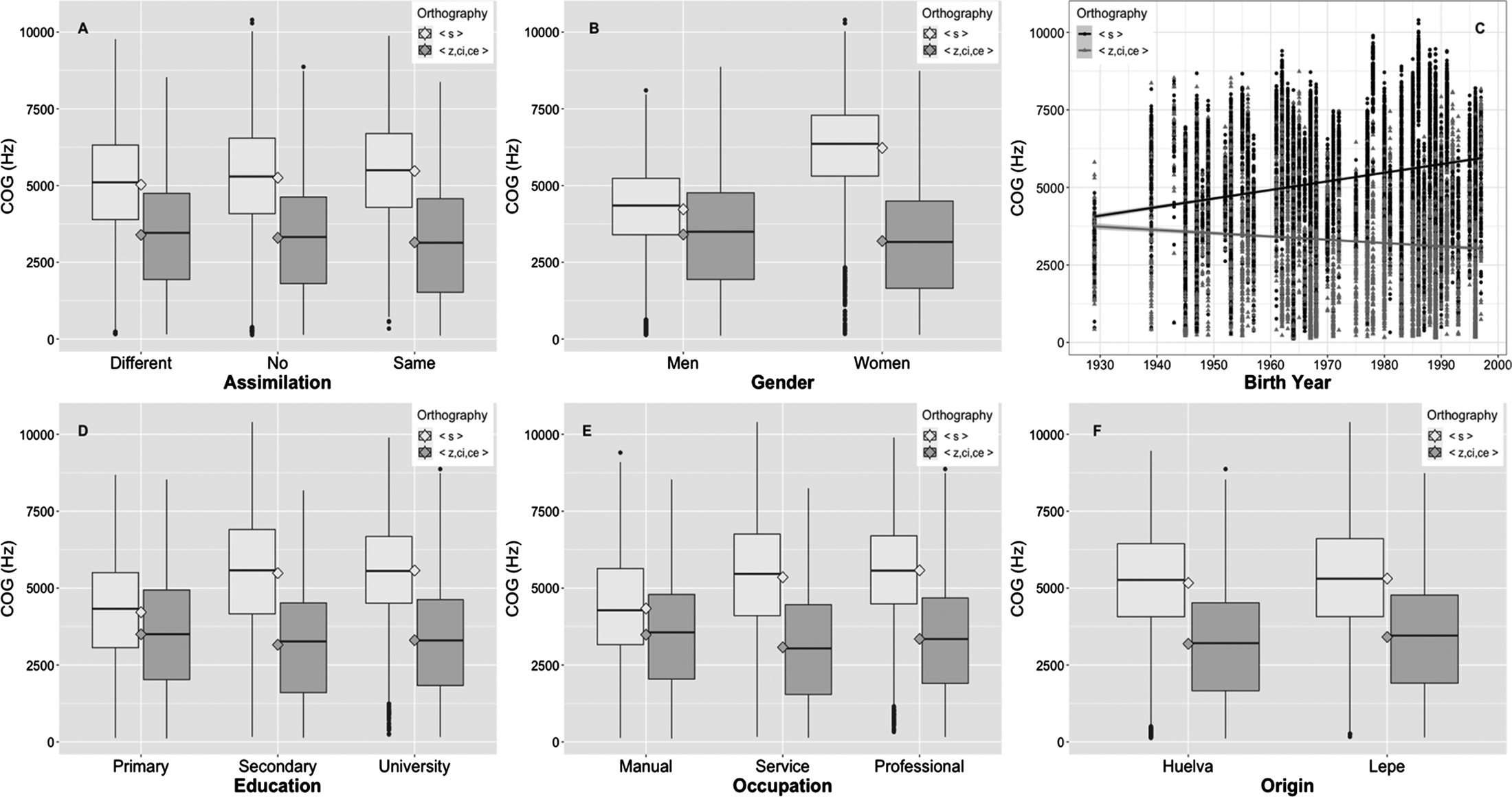

Figure 2. Interactions of orthography by assimilation (a), by gender (b), by ageFootnote 11 (1929 = 86, 1997 = 18) (c), by education (d), by occupation (e), and by origin (f) for COG (Hz).

For the orthography by gender interaction, <s> had higher COG than <z> for men (p < 0.001) and women (p < 0.001). However, women had higher COG for <s> than men (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates a larger separation in phonemes for women than men (Figure 2). For the orthography by education interaction, <s> had higher COG than <z> for those with primary (p < 0.001), secondary (p < 0.001), and university education (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that those with primary education have smaller COG differences between phonemes than those with secondary or university education (Figure 2).

The orthography by age interaction demonstrates that, for a one-year increase in age, COG for <s> decreases by 21.64 Hz and for <z> increases by 11.20 Hz. This indicates that the difference in COG between orthographic environments is largest between younger speakers, and this difference decreases as age increases (Figure 2). A Pearson correlation indicated a weak negative association between COG and age for <s> (n = 10683, df = 10681, r = -0.246, R2 = 0.061, p < 0.0001) and a weak positive association between COG and age for <z> (n = 8737, df = 8735, r = 0.097, R2 = 0.009, p < 0.0001). For the orthography by occupation interaction, <s> had higher COG than <z> for those with manual (p < 0.001), service (p < 0.001), and professional occupations (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that those with manual occupations have a smaller difference in COG between <s> and <z> than those with service or professional occupations (Figure 2). For the orthography by origin interaction, <s> had higher COG than <z> for Huelva (p < 0.001) and Lepe (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that Huelva has a larger difference in COG between <s> and <z> than Lepe (Figure 2).

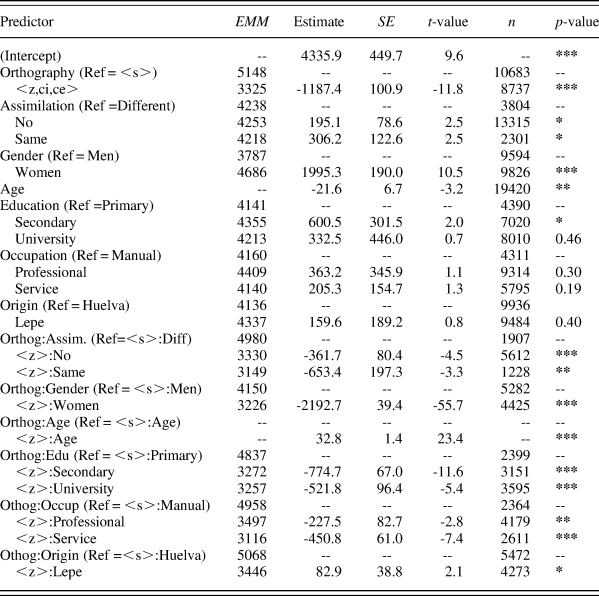

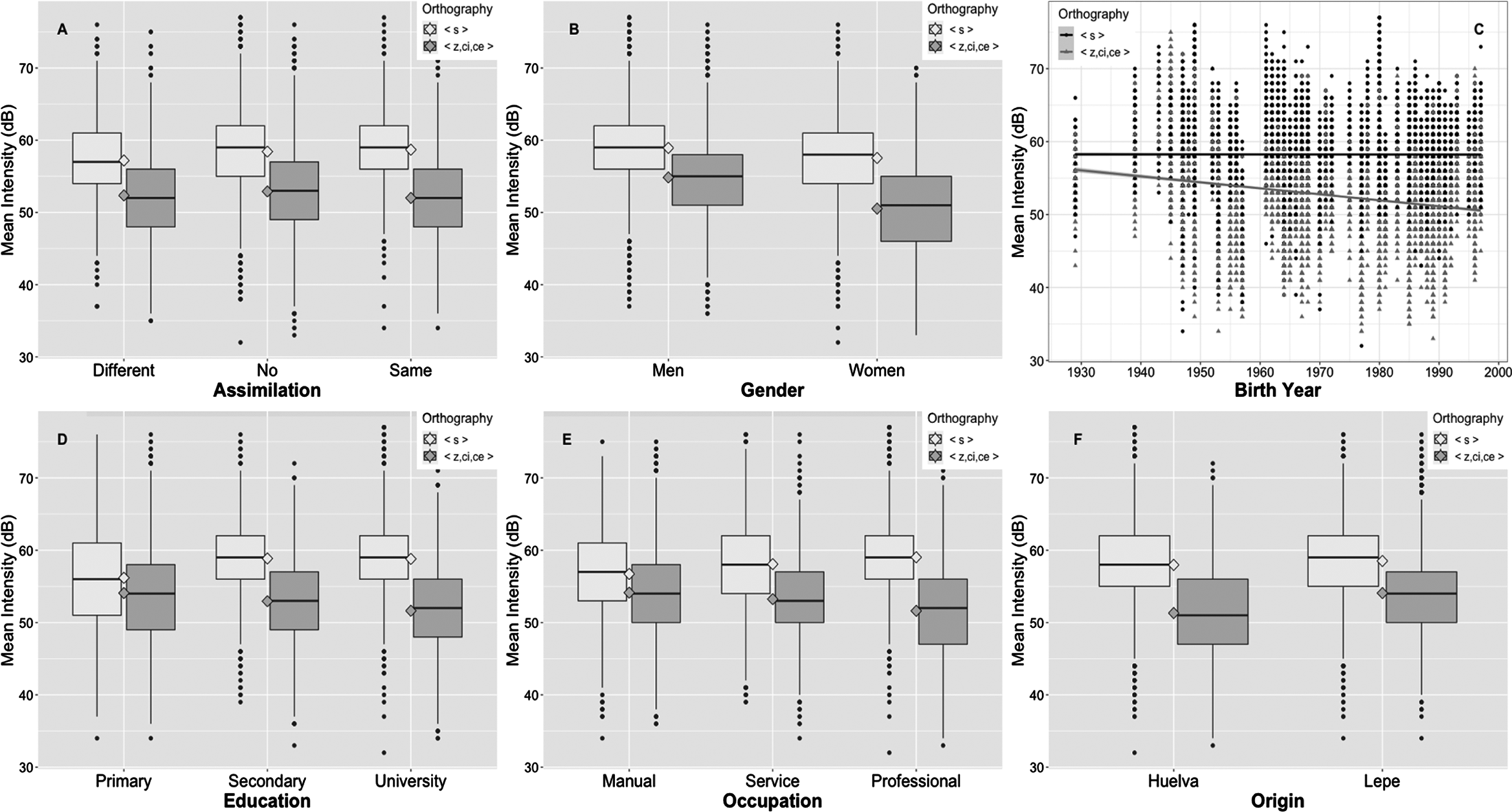

The best-fit mixed effects linear regression model for MI is shown in Table 4. The main effect of orthography indicates that <s> had a significantly higher MI than <z> (p < 0.001). For the orthography by assimilation interaction, <s> had a higher MI than <z> for different (p < 0.001), no (p < 0.001), and same additional fricative (p < 0.001). For <s>, different had a smaller MI than no (p < 0.001) and same additional fricative (p < 0.05). The interaction indicates that words with two different orthographic environments have a smaller MI difference between phonemes as compared to words with no additional fricatives or words with the same orthographic environment (Figure 3). For orthography by stress, <s> had a higher MI than <z> for atonic (p < 0.001) and tonic syllables (p < 0.001). For <s>, atonic had lower MI than tonic (p < 0.001). For <z>, atonic had greater MI than tonic (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that tonic syllables have a greater MI difference between phonemes than atonic syllables.

Table 4. Summary of linear mixed effects regression model for MI, speaker and word as random factors; n = 19,420 (R2m: 0.327, R2c: 0.676). EMM = estimated marginal means

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001

Figure 3. Interactions of orthography by assimilation (a), by gender (b), by age (1929 = 86, 1997 = 18) (c), by education (d), by occupation (e), and by origin (f) for MI (dB).

The orthography by age interaction demonstrates that for a one-year increase in age, MI for <s> increases by 0.051 dB and MI for <z> increases by 0.098 dB. Thus, with each increase in year, the difference in MI between phonemes decreases (Figure 3). A Pearson correlation indicated a nonsignificant weak positive association between MI and age for <s> (n = 10683, df = 10681, r = 0.006, R2 = 0.000004, p = 0.55), but a weak positive association between MI and age for <z> (n = 8737, df = 8735, r = 0.227, R2 = 0.052, p < 0.0001). For the orthography by gender interaction, <s> had higher MI than <z> for men (p < 0.001) and women (p < 0.001). For <s>, men had higher MI than women (p < 0.05). For <z>, men had higher MI than women (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that there is a larger separation in MI between phonemes for women than men (Figure 3).

For the orthography by education interaction, <s> had higher MI than <z> for those with primary (p < 0.001), secondary (p < 0.001), and university education (p < 0.001). The interaction indicates that there is a larger separation in MI between phonemes for those with secondary or university education compared to those with primary education (Figure 3). For the orthography by occupation interaction, <s> had a greater MI than <z> for those with manual (p < 0.001), service (p < 0.001), and professional occupations (p < 0.001). For <s>, those with manual occupations had smaller MI than those with service occupations (p < 0.001). For <z>, those with manual occupations had smaller MI than those with service occupations (p < 0.05). The interaction indicates that there is a larger separation in MI between phonemes for those with service or professional occupations than those with manual occupations (Figure 3). For the orthography by origin interaction, <s> had higher MI than <z> for Huelva (p < 0.001) and Lepe (p < 0.001). For <z>, Lepe had higher MI than Huelva (p < 0.01). The interaction indicates that there is a larger separation in MI between phonemes for Huelva than Lepe (Figure 3).

Individual speaker analysis

In addition to the community-wide trends, individual speakers were analyzed to see if there are individuals with a complete merger, or perhaps a near-merger, as well as to analyze the number of speakers who demonstrate statistically significant differences on various dependent measures between word sets with <s> or <z,ci,ce>. A paired Welch Two Sample t-test was conducted for all seven dependent measures per style (passage, wordlist) based on orthography for each individual. As there were 14 t-tests run for each individual, a Bonferroni correction was made. Specifically, the alpha of 0.05 was divided by fourteen to produce 0.0036. Thus, only p-values below the adjusted alpha of 0.0036 were considered significant. Table 5 demonstrates that the most robust measures are COG, variance, skewness, and MI. Given the lack of significance for so many speakers for kurtosis, spectral peak, and duration, they will not be discussed further as they do not appear to be adequate measures to distinguish Andalusian coronal fricatives. As one can observe from the individual speaker mean scores from Huelva (online Appendix II) and Lepe (online Appendix III), the majority of speakers are able to produce a significant difference between <s> and <z,ci,ce> in at least one of the acoustic parameters. However, for the reading passage, there were seven speakers (L6, L9, L46, L47, H4, H12, H54) that did not produce a significant difference for any acoustic measure, indicating a complete merger. There were two additional speakers (H27, H59) that only demonstrated significance on one measure: variance. For the wordlist, there were six speakers (L3, L23, L54, H32, H54, H59) that did not show a significant difference for any acoustic measure. There were an additional four speakers (L46, L47, H12, H59) that only demonstrated significance on one measure: variance.

Table 5. Number of speakers per measure per style (passage, list) demonstrating a significant difference between <s> and <z,ci,ce> in expected direction

For a visualization of the individual data, here we look at one speaker who realizes what appears to be a complete merger, and another speaker with a clear separation of phonemes for the reading passage. Figure 4 plots the two most robust measures of MI on the x-axis and COG on the y-axis. L9's scatterplot reflects the lack of significant difference in both measures. L9's mean <s> (4,280.34 Hz, 48.68 dB) and <z,ci,ce> (4,336.64 Hz, 48.97 dB) are separated by -130.47 Hz and -0.295 dB. However, H20 produces a clear separation between phonemes, with the exception of two <s> outliers. H20's mean <s> (7,317 Hz, 55.84 dB) and <z> (2,145.33 Hz, 41.55 dB) are separated by 5,172.67 Hz and 14.29 dB. Figure 4 demonstrates a similar pattern with skewness on the x-axis and variance on the y-axis. L9's mean <s> (0.56 skewness, 3,183 Hz variance) and <z> (0.46 skewness, 3,183 Hz variance) overlap completely, while H20's mean <s> (-1.51 skewness, 1,750 Hz variance) and <z> (2.42 skewness, 2,637 Hz variance) are fully separated. It appears that the ceceo merger presents intermediate values between alveolar [s̪] and interdental [θ] for COG, MI, and skewness, but perhaps a variance similar to [θ].

Figure 4. Scatterplots of COG (Hz) by MI (dB) for reading passage for L9 (a) and H20 (b); Scatterplots of variance (Hz) by skewness for reading passage for L9 (c) and H20 (d).

Demerger Index analysis

Given the large amount of inter- and intraspeaker variation across measures, a “Demerger Index” was created to conduct follow-up analyses. The purpose of creating a Demerger Index was threefold: (i) to normalize the data to avoid sex-related effects on spectral parameters; (ii) to quantify the degree of demerger as individual analyses of speakers only reveal whether or not differences were significant; and (iii) to better investigate the main effects and interactions of the social factors, as the previous analyses had to incorporate orthography in interaction with all factors. The Demerger Index was calculated by subtracting an individual's means from each orthographic environment per style (passage = μ<s> - μ<z,ci,ce>; list = μ<s> - μ<z,ci,ce>). Thus, all means were calculated over all linguistic factor environments. Demerger Index scores should be interpreted as follows: larger index numbers suggest a larger separation in phonemes based on the given acoustic cue, while scores closer to zero indicate either a merger or a near-merger. Given COG, MI, skewness, and variance were the most robust measures from the individual speaker analysis, demerger indexes were created for each of these measures. Expected directions for acoustic measures of a speaker with distinción (/s/ and /θ/) should produce positive indexes for COG, positive indexes for MI, negative indexes for skewness, and negative indexes for variance. For each measure, a mixed effects linear regression model was run, including all social factors as fixed factors with speaker as a random factor. Within each model, each factor that was not significant was removed from subsequent models. Marginal R2 values and conditional R2 values were obtained for each model in order to assess the best fit of variation per measure: COG (R2m: 0.513, R2c: 0.937), MI (R2m: 0.440, R2c: 0.859), skewness (R2m: 0.256, R2c: 0.918), and variance (R2m: 0.229, R2c: 0.849). As the COG and MI Demerger Indexes produced better models of the variation, only they will be discussed.

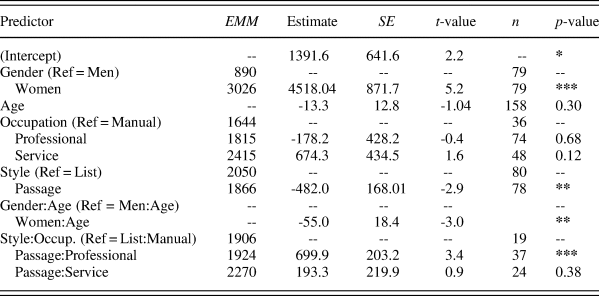

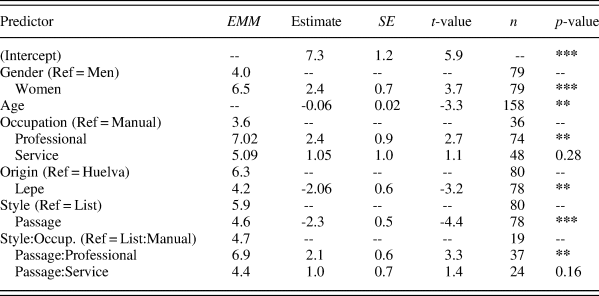

COG and MI Demerger Index regression tables display the emmeans (EMM), estimate, standard error (SE), t-value, number of tokens per level (n), and p-value. Positive estimates indicate a higher COG/MI Demerger Index compared to the reference value, while negative estimates indicate a lower COG/MI Demerger Index compared to the reference value. The best-fit mixed effects linear regression model for COG Demerger Index is shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Summary of mixed effects linear regression for COG Demerger Index, speaker as a random factor; n = 158 (R2m: 0.513, R2c: 0.937). EMM = estimated marginal means

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001

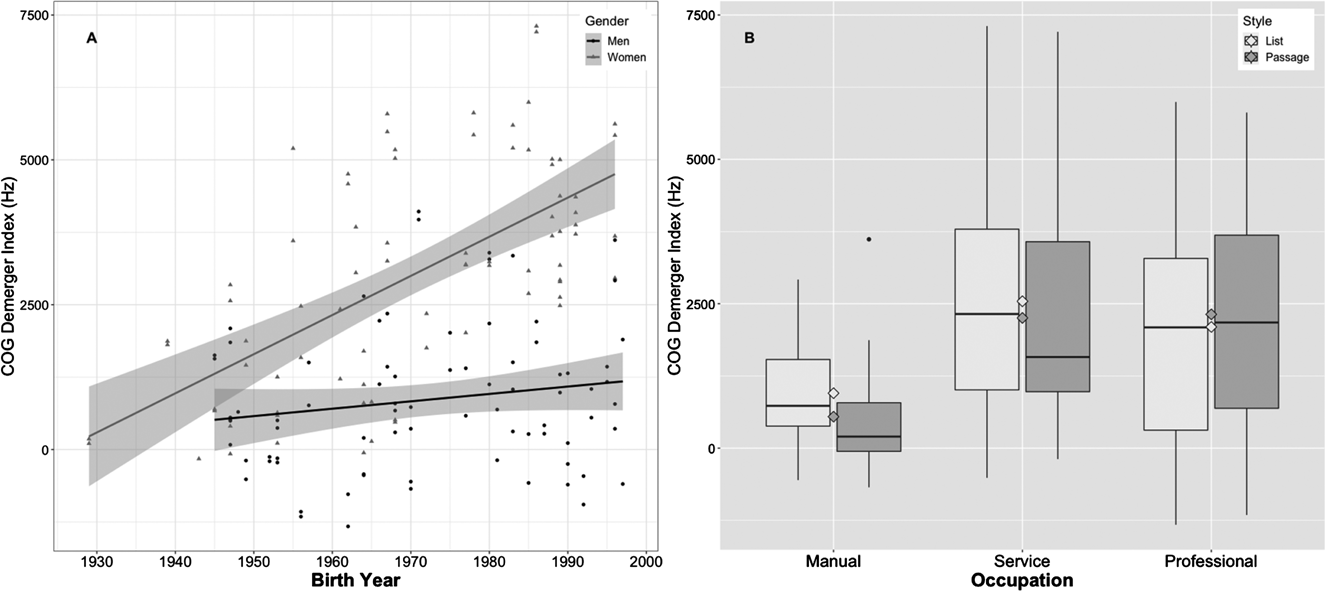

The main effect of gender indicates that women have a larger COG Demerger Index than men (p < 0.001). The gender by age interaction indicates that, for each year increase in age, men's COG Demerger Index decreases by 13.28 Hz while women's Demerger Index decreases by 68.23 Hz (Figure 5). Pearson correlations indicated that there was a nonsignificant negative association between age and COG Demerger Index for men (n = 78, df = 77, r = -0.175, R2 = 0.031, p = 0.12) but a significant moderate negative association between age and COG Demerger Index for women (n = 78, df = 77, r = -0.609, R2 = 0.371, p < 0.001). The main effect of style indicates that the wordlist had a larger COG Demerger Index than the reading passage (p < 0.05). The style by occupation interaction indicates that the COG Demerger Index is greater in the wordlist than the reading passage for those with manual (p < 0.01) and service occupations (p < 0.05) but no significant difference for professional occupations (p = 0.06) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Gender by age (1929 = 86, 1997 = 18) interaction (a) and occupation by style interaction (b) for COG Demerger Index (Hz).

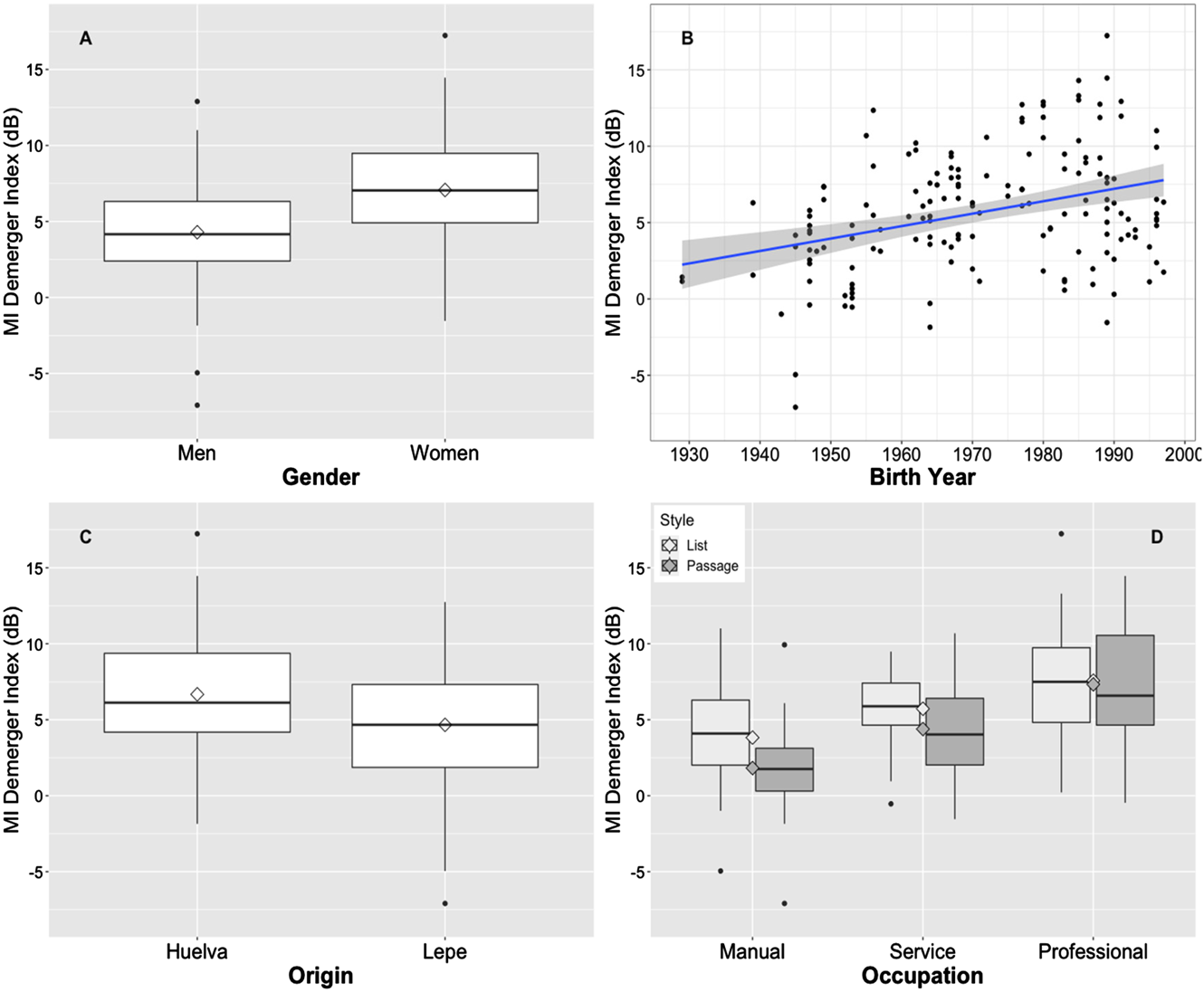

Table 7 displays the best-fit mixed effects linear regression for MI Demerger Index. The main effect of gender indicates that women had a higher MI Demerger Index than men (p < 0.001) (Figure 6). The main effect of age indicates that, with each year increase in age, the MI Demerger Index decreases by 0.064 dB (Figure 6). A Pearson correlation indicates a moderately negative association between increase in age and MI Demerger Index (n = 158, df = 156, r = -0.345, R2 = 0.119, p < 0.001). The main effect of style indicates that the wordlist had a higher MI Demerger Index than the reading passage (p < 0.0001). The main effect of origin indicates that Huelva had a higher MI Demerger Index than Lepe (p < 0.001) (Figure 6). The main effect of occupation indicates that those with professional occupations had a higher MI Demerger Index than those with manual (p < 0.001) and service occupations (p < 0.05), but that those with manual and service occupations did not differ. The occupation by style interaction demonstrates that the wordlist had a higher MI Demerger Index than the passage for those with manual (p < 0.0001) and service occupations (p < 0.01), but not for professional occupations (p = 0.50) (Figure 6).

Table 7. Summary of mixed effects linear regression for MI Demerger Index, speaker as a random factor; n = 158 (R2m: 0.440, R2c: 0.859). EMM = estimated marginal means

Note: * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001

Figure 6: Main effect of gender (a), main effect of age (1929 = 86, 1997 = 18) (b), main effect of origin (c), and style by occupation interaction (d) for MI Demerger Index (dB).

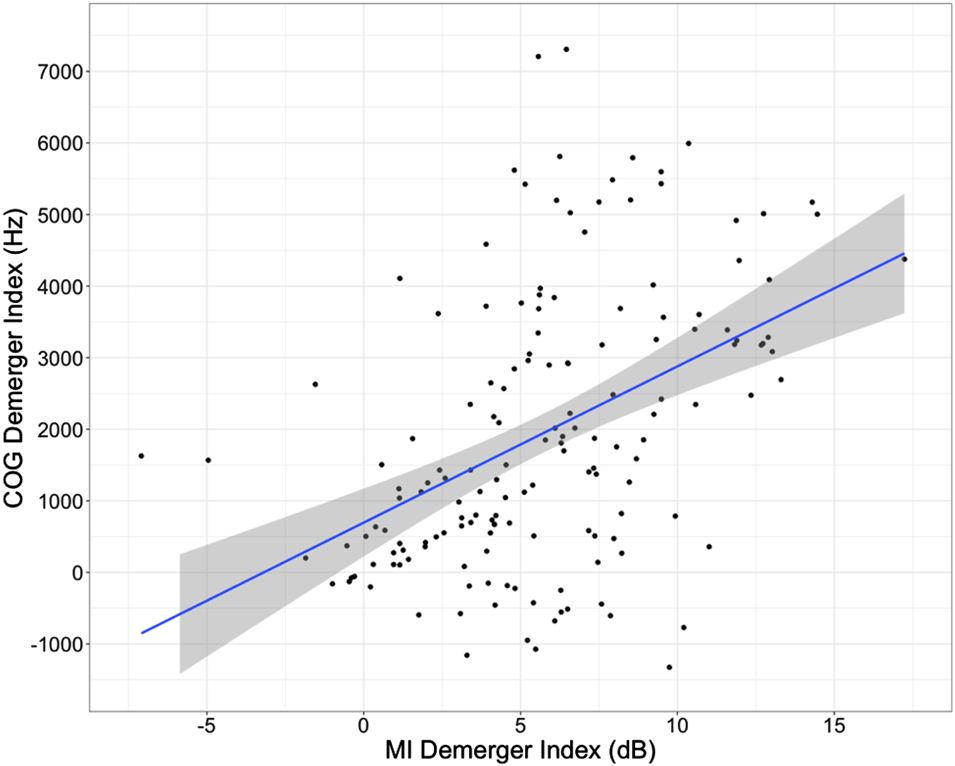

In order to assess the relationship between the COG and MI Demerger Indexes, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was computed. The two measures are moderately correlated (n = 158, df = 156, r = 0.45, R2 = 0.203, p < 0.001). A scatterplot summarizes the results (Figure 7). For a reference point, the absolute point of merger is 0,0, meaning there is no difference between an individual's mean <s> and <z,ci,ce> realizations for COG or MI. Positive numbers indicate that an individual's mean <s> realization is higher than their mean <z,ci,ce> for either COG or MI (the expected direction of a split following the acoustic properties of [s̪] and [θ]). Negative numbers indicate that an individual's mean <s> realization is lower than their mean <z,ci,ce> for either COG or MI, indicating a potential flip-flop (Di Paolo, Reference Di Paolo1992; Hall-Lew, Reference Hall-Lew2013; Labov et. al., Reference Labov, Yaeger and Steiner1972; Labov et al., Reference Labov, Karen and Miller1991). The moderate correlation suggests that increases in the COG Demerger Index are correlated with increases in the MI Demerger Index. However, there are several speakers who are close to a zero on the COG Demeger Index but have a positive score on the MI Demerger Index, indicating that perhaps MI is a more acquirable acoustic parameter.

Figure 7. Scatterplot of COG Demerger Index (Hz) and MI Demerger Index (dB) correlation.

DISCUSSION

RQ1: Complete vs. near-merger

The finding that several speakers did not demonstrate a significant difference across several or any acoustic measures between orthographic environments for one or both tasks suggests that ceceo is a complete merger as reported by dialectologists and historical linguists. This does not, however, preclude the existence of speakers with a near-merger. There are several speakers that demonstrate subtle, but statistically significant, differences in one or more acoustic measures. This could be true of the first generation of speakers to separate the phonemes; that is, the near-merger could be the first step in the split of a complete merger. It seems unlikely that speakers would have maintained some subtle difference since the seventeenth century, as there would have been little dialect contact and high illiteracy rates until the twentieth century.

RQ2: Demerger

The hypothesis that there is a split of ceceo into distinción is supported by the findings. However, given it is read speech, similar to Lasarte Cervantes (Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010), the study can only speak to phonetic abilities as opposed to underlying phonological representation. The orthography results demonstrate that residents of Huelva and Lepe produce significant acoustic differences between word sets with <s> and <z,ci,ce>, contrasting dialectology accounts of Huelva and Lepe as predominantly ceceante (Alvar et al., Reference Alvar, Llorente, Salvador and Mondéjar1973; Mendoza Abreu, Reference Mendoza Abreu1985; Navarro Tomás et al., Reference Navarro Tomás, Espinosa and Rodríguez-Castellano1933).

RQ3: Factors leading to demerger

The results supported previous findings for orthography (García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Villena & Requena, Reference Villena Ponsoda and Requena Santos1996) and assimilation (Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Moya Corral and Sosiński2007). The results demonstrate that words with an additional same grapheme have the largest phonetic separation between phonemes, followed by no additional fricative, and then an additional different grapheme. These findings expand on Moya Corral and García Wiedemann's (Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995) distinction between “simple” and “double” environment by demonstrating that there are also differences within the double environment in which the presence of a different grapheme in a word can trigger an assimilation effect. Finally, it was found that tonic fricatives had a larger difference in intensity between phonemes than atonic fricatives.

The hypotheses regarding gender, age, education, occupation, and style were supported. The leaders of demerger are woman, younger speakers, those with secondary or university education, those employed in service or professional occupations, those from Huelva, and in more formal styles. Thus, this demerger is a socially motivated change from above (Labov, Reference Labov1994:78). The gender results support previous work of Andalusian coronal fricatives in which women favor distinción more than men (García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Melguizo Moreno, Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; inter alia). This finding supports Principle 3 of the Gender Pattern: “In linguistic change from above, women adopt prestige forms at a higher rate than men” (Labov, Reference Labov1990:213; Reference Labov2001:274). This is not to say that each group behaves monolithically. As Eckert (Reference Eckert1989:253) noted, gender does not have a uniform effect, but interacts with other social factors.

The age results demonstrate an apparent time change from ceceo to distinción, supporting Villena's (Reference Villena Ponsoda2001) and Morillo-Velarde's (Reference Morillo-Velarde2001) claims that the demerger of ceceo began in the 1950s. Younger speakers are producing larger acoustic differences between orthographic environments than older generations. This is unmistakably related to education, as younger generations have higher educational attainment than older generations. However, the age by gender interaction indicates that younger woman have an even larger separation of phonemes than younger men.

The education results support previous studies in which those with more education favor distinción (Ávila, Reference Ávila1994; García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Melguizo Moreno, Reference Melguizo Moreno2007; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, Reference Moya Corral and García Wiedemann1995; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda1996; inter alia). Those with secondary and university education demonstrate a larger phonetic difference between orthographic environments than those with primary education. This is due to the fact that Andalusian educational settings teach distinción. It appears to be a case where there has been an educational campaign (Labov, Reference Labov1994:343) to promote a split.

The occupation results exhibit the importance of the linguistic market (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1991; Bourdieu & Boltanski, Reference Bourdieu and Boltanski1975; Sankoff & Laberge, Reference Sankoff, Laberge and Sankoff1978). Those with professional or service-oriented occupations demonstrate a significantly larger phonetic separation of phonemes than do those with manual occupations. As distinción has more linguistic capital,Footnote 12 speakers in professional environments are both exposed to and expected to use more distinción. The interaction of style and occupation in the Demerger Indexes indicates that those with manual and service-oriented occupations increase phonetic differences between phonemes in more formal styles. Although those with professional occupations demonstrated the largest overall Demerger Indexes, they exhibited no difference between styles, indicating that this change is advanced for these speakers.

RQ4: Rural-urban differences

The findings suggest that, as speech communities, Huelva produces a larger phonetic difference between orthographic environments than Lepe, supporting previous findings comparing rural and urban Andalusian communities (Lasarte Cervantes, Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010, Reference Lasarte Cervantes, Villena-Ponsoda and Ávila-Muñoz2012; Melguizo Moreno, Reference Melguizo Moreno2007, Reference Melguizo Moreno2009). This is not to say that each community behaves monolithically, but rather the demerger is more advanced in Huelva. In this sense, urban Huelva is significantly different from rural Lepe. However, in line with Britain's (Reference Britain and Al-Wer2009, Reference Britain, Auer and Schmidt2010, Reference Britain, Hansen, Schwarz, Stoeckle and Streck2012) rejection of the rural-urban dichotomy, it is proposed that Huelva is different than Lepe in the rate/stage of linguistic change, but not necessarily in the process of linguistic change. While large-scale societal changes have affected both communities, it is the specific histories of each community (i.e., earlier dialect contact in Huelva) that have led to this difference in rate of change.

RQ5: Acoustic profiles

The results suggest that ceceo [s̪θ] is an intermediate realization between alveolar [s̪] and interdental [θ] in MI, COG, and skewness, while similar in variance to [θ]. The MI results support Lasarte Cervantes’ (Reference Lasarte Cervantes2010:489) addition of ceceo to Martínez Celdrán and Fernánez Planas’ (Reference Martínez Celdrán and Fernández Planas2007:107) intensity continuum. Similarly, the results suggest a COG continuum in which [s̪θ] is between [s̪] and [θ]. Although these two continuums work in tandem, Figure 7 indicates that demerging speakers are better able to acquire the parameter of MI to separate the phonemes. From an articulatory standpoint, this may indicate that it is more difficult to acquire a change in place of articulation as reflected by COG and, instead, are relying on an amplitudinal parameter. That is, perhaps MI is an easier parameter to acquire as an adult. Although read-speech may be a limitation for sociolinguistic claims, it serves as an advantage for a preliminary description of the acoustic profiles of ceceo and distinción. Thus, COG, MI, skewness, and variance appear to be meaningful acoustic parameters for Andalusian coronal fricatives but not spectral peak, kurtosis, or duration.

Sociolinguistic theory of mergers/splits

Labov (Reference Labov1994:343, 348; Reference Labov2010:121) acknowledges that dialect contact and education may allow individuals to reverse a merger with the appropriate context but that a community-wide split is unlikely. In the current case, the original innovation was during the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries in which dialect contact led to the merger of four medieval sibilants into dental /s̪/ in Andalusian Spanish, phonetically realized as ceceo or seseo. However, in Castilian Spanish, these four medieval sibilants merged into two phonemes; apicoalveolar /s̺/ and interdental /θ/ (Penny, Reference Penny2000, Reference Penny2002). The modern-day contact of Castilian speakers with Andalusian speakers, perhaps beginning in the 1960s in Huelva with the arrival of speakers with distinción from other regions to work in the industrial plants, allowed for dialect contact and subsequent split of the centuries-old merger. This timeline also co-occurs with the arrival of television broadcasting in 1956, increasing exposure to distinción. Thus, dialect contact likely was the catalyst for the split of ceceo. If Garde's Principle (Reference Garde1961:38–9) is taken to mean that, in the absence of dialect contact, a merger will not split, then the results have little to say about Garde's Principle. If, however, Garde's Principle is interpreted to mean that splits are impossible no matter the context, the current study provides phonetic support for previous claims that the demerger of ceceo is an exception to Garde's Principle (Moya Corral & Sosiński, Reference Moya Corral and Sosiński2015:35; Regan, Reference Regan2017a:152, Reference Regan2017b:259; Villena, Reference Villena Ponsoda2001:126; Villena & Vida Castro, Reference Villena Ponsoda, Vida Castro, Villena Ponsoda and Ávila Muñoz2012:117–18).

Supporting Maguire et al.'s (Reference Maguire, Clark and Watson2013:234) claim, the current study also provides an example that Herzog's Principle (Herzog, Reference Herzog1965; Labov, Reference Labov1994:313) may be “compromised” when a merger becomes stigmatized. That is, a distinction is expanding at the expense of a merger due to social stigmatization as a result of dialect contact. In fact, if we connect previous studies of the demerger of ceceo (and of seseo) throughout Andalusia to the current results, the split of ceceo into distinción is not only one of the largest phonological changes occurring in the Spanish-speaking world, but also perhaps one of the largest demergers in recorded linguistics. Thus, while there is ample support for Garde's and Herzog's Principles, in light of the current results in connection with recent studies it appears that both principles represent overarching tendencies, but that adequate dialect contact and social contexts allow for exceptions.

Societal change and dialect contact

The results support the overwhelming trend found in European social dialectology in which large-scale societal changes have increased dialect contact, leading to the levellingFootnote 13, Footnote 14 of local traditional dialectal features in favor of regional or national features (Auer & Hinskens, Reference Auer and Hinskens1996; Hinskens et al., Reference Hinskens, Auer, Kerswill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005). Societal changes appear to have first affected Huelva, beginning in the 1960s with the industrial plants, which brought speakers with distinción from other regions. However, both communities have shifted toward more service-based and professionally oriented occupations where distinción receives more linguistic capital and have seen a dramatic increase in educational attainment. As distinción is a direct grapheme-to-phoneme prescriptive correspondence taught in schools, this is a principle mechanism of the change.

The current results and other recent findings (García-Amaya, Reference García-Amaya, Siegel, Nagle, Lorente-Lapole and Auger2008; Gylfadottir, Reference Gylfadottir2018; Regan, Reference Regan2017a; Santana, Reference Santana Marrero2016, Reference Santana Marrero2016–2017) indicate that parts of Western Andalusia, particularly among highly educated younger speakers, favor distinción, similar to Eastern Andalusia. An increase in sociolinguistic salience of ceceo due to societal changes likely prompted this dialect levelling. As noted in situations of dialect contact, salience can promote levelling (Erker, Reference Erker2017; Kerswill & Trudgill, Reference Kerswill, Trudgill, Auer, Hinskens and Kerswill2005; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1986).

CONCLUSION

This study has provided the first large-scale acoustic analysis of Andalusian coronal fricatives, supporting previous claims that the ceceo merger is splitting into distinción. The findings demonstrate that societal changes in Huelva and Lepe have provided the adequate social context to promote the split of a merger. This change from above demonstrates the importance of societal change in sound change, even if it runs contrary to natural language tendencies. While the study analyzed phonetic abilities with read speech, future work will examine underlying phonological representations with spontaneous speech. In conclusion, the split of ceceo into distinción demonstrates a socially motivated, community-wide demerger, providing further evidence to a growing body of literature that the split of a merger is possible given the adequate social context and dialect contact.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954394520000113

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am greatly indebted to Jacqueline Toribio, Barbara Bullock, Malcah Yaeger-Dror, Rajka Smiljanic, Dale Koike, Danny Erker, and Sergio Romero for instrumental feedback, to Sally Ragsdale for statistical guidance, to four anonymous reviewers for their invaluable input, and to audiences at NWAV 45, HLS 2016, and ICLAVE-9. I am truly grateful to the buena gente of Huelva and Lepe who were so gracious to share their time and stories with me. This investigation was funded by a NSF DDRI Award (BCS-1528551). All errors remain my own.