The understanding of language as part of a wider projection of identity and affiliation implies that linguistic features do not have static meaning and are not independent from each other. Instead, a single linguistic feature can take on social meanings and can occur in combination with other linguistic variables to project a collective social meaning (Campbell-Kibler, Reference Campbell-Kibler2011; Pharao, Maegaard, Møller, & Kristiansen, Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Møller and Kristiansen2014; Pharao & Maegaard, Reference Pharao and Maegaard2017; Podesva, Reference Podesva2008).

This paper investigates to what extent the differing social meanings held by linguistic features can lead to an implicational relationship between them. Rates of co-variation between (ing) and (h) at the between-speaker level are investigated as well as clustering effects at the within-speaker level. In Debden, the indexicalities of g-dropping (working-class and “improper” speech) are incorporated in the superordinate indexicalities of h-dropping (Cockney heritage). While it is possible for a Debden speaker to index working-class speech without indexing their Cockney heritage, the reverse is not possible. As such, I postulate that there is an implicational relationship between (h) and (ing): h-dropping implies g-dropping, but g-dropping can occur alongside any value of (h).

Style clusters

Approaches to style in sociolinguistics have evolved from earlier unidimensional definitions to consider linguistic features to be symbolic resources that hold variable indexicalities both individually, and in combination with, other linguistic features (Moore, Reference Moore2004). “Indexicality” refers to the ideological relationship between linguistic features and a social group, persona, characteristic, or place that they signal (see Eckert, Reference Eckert2008; Johnstone, Andrus, & Danielson, Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006; Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2003). Linguistic features can hold indexicalities that are not only connected to macro categories (e.g., class, ethnicity, or gender) but to locally meaningful characteristics (e.g., “jocks” versus “burnouts” in Detroit [Eckert, Reference Eckert1999]; “populars” versus “townies” in Northern England [Moore, Reference Moore2004]). Indexicalities are not limited to stable aspects of speaker identity but can be changeable (for instance, indexing interactional stance). Speakers are active, stylistic agents who tailor their linguistic output in variable projections of self (Eckert, Reference Eckert2012).

Single speakers can represent themselves in variable and complex ways, in part, through their linguistic production (Eckert & Labov, Reference Eckert and Labov2017; Rickford & Price, Reference Rickford and Price2013). For instance, Podesva (Reference Podesva2008) demonstrated variability in the speech of a single speaker, Heath, who was asked to record himself in different situations. Podesva identified style clusters of linguistic features when salient interactional moves in discourse occur such that Heath is projecting either his “diva” or “caring doctor” persona, suggesting that sociolinguistic styles and their meanings only materialize as a result of the overlapping meaning of each component linguistic feature. For instance, in Heath's speech, frequent (t,d) deletion indexes “informal” and frequent and extreme falsetto indexes “expressive.” While both of these features (among others) combine to index “diva,” only the former indexes “informal” (Podesva, Reference Podesva2008:4). It follows, then, that linguistic features that jointly index a certain stance or persona do not consistently cluster together across all utterances. That is, not every instance of (t,d) deletion must be accompanied by extreme falsetto, as Heath may solely be indexing informality but not “expressive” or the superordinate style “diva.”

Several phonetic perception studies also demonstrate that the social meaning of individual linguistic features can combine to create the overall, superordinate social meaning of an utterance. For instance, Campbell-Kibler (Reference Campbell-Kibler2011) played participants in the United States a range of variants and combinations of (ing) and /s/-fronting/backing. She found that /s/-fronting is associated with gayness and being less masculine while g-dropping is associated with masculinity. Nonetheless, a backed /s/ could also index associations of “country” when it was found in the speech of some Southern US speakers but this was dependent on its surrounding linguistic context. Similarly, in a matched-guise study, Pharao et al. (Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Møller and Kristiansen2014) found that, in Copenhagen, a fronted-/s/ could index either “gayness” or a “street” persona, depending on the cluster of linguistic features with which it co-occurred (see also Levon, Reference Levon2014; Pharao & Maegaard, Reference Pharao and Maegaard2017).

These studies demonstrate that linguistic variants do not occur independently of their surrounding linguistic and social context. In this sense, grammatical coherence is also an important consideration in determining the resultant linguistic variant (Guy, Reference Guy2013; Oushiro & Guy, Reference Oushiro and Guy2015). A morphological or syntactic repetition effect has long been noted in the persistence literature (Poplack, Reference Poplack1980; Scherre & Naro, Reference Scherre, and Naro and Anthony1991) such that a speaker is more likely to produce a particular linguistic structure if they (or an interlocutor) have recently used that structure. For instance, a speaker is more likely to use verb + gerundial as opposed to verb + infinitival complementation if they or an interlocutor have recently used the former (Szmrecsanyi, Reference Szmrecsanyi2006:1). In these instances, clustering of the same morphological or syntactic construction is not a social or stylistic effect but is considered to be psychologically motivated as a priming or recency effect (see Tamminga, Reference Tamminga2016:337). In this present study, there is no reason to believe that a dropped /h/ would psychologically prime g-dropping through grammatical persistence (and vice-versa) as they operate independently of each other in terms of syntactic or morphological conditioning. Therefore, any clustering between the two variables is more likely due to social and stylistic factors.

In summary, linguistic features can have overlapping or distinct indexicalities that can combine to create a meaningful package. Within the speech of an individual speaker, there may be stylistic clusterings of linguistic features that jointly index a certain association. Nonetheless, this may be, in part, mediated by the features’ respective social meanings. This paper explores to what extent the differing social meanings of (h) and (ing) result in an implicational relationship between the features.

Between-speaker co-variation in linguistic features

The above section has examined the clustering of linguistic features within individual speaker systems. In addition, this paper explores co-variation between linguistic features at the between-speaker level. It initially seems plausible that, if variable X and variable Y share a similar social distribution in a speech community, there will be between-speaker correlations between the rates of occurrence of these features. Nonetheless, a wide range of studies have found weak correlations between rates of similarly socially stratified linguistic variables (New York City English: Becker, Reference Becker2016; Copenhagen Danish: Gregersen & Pharao, Reference Gregersen, Pharao, Hinskens and Guy2016; Brazilian Portuguese: Oushiro & Guy, Reference Oushiro and Guy2015). That is, while variable X and variable Y may share a similar social distribution in a speech community, speakers who have relatively high rates of the vernacular form of variable X may not necessarily have relatively high rates of the vernacular variant of variable Y. The weak correlations found between linguistic variables with similar social stratifications suggests that social distribution alone is not enough to predict co-variation between linguistic features.

Instead, this paper predicts that the differing social meanings held by linguistic traits may mediate the rates of between-speaker co-variation. Not all linguistic features that have a social distribution are used stylistically (e.g., Sharma & Rampton, Reference Sharma and Rampton2015). If variable X does not hold social meaning and is not used agentively by speakers, we would expect relatively steady and predictable rates of production for this variable. In contrast, if variable Y holds social meaning and, as such, is used stylistically and agentively, there will likely be both within-speaker and between-speaker variability in the production of this variable. For instance, two speakers who, on the surface, share many macrosocial characteristics, may not equally identify with the indexicalities of a particular variant of variable Y. Thus, there may be imperfect correlations between rates of variable X and variable Y. It seems, then, that the social meaning as well as the social distribution of linguistic features may explain rates of co-variation.

It may initially seem somewhat paradoxical to simultaneously consider that linguistic variables can have a systematic social distribution while also considering speakers to be agentive, variable, and perhaps unpredictable in their speech. However, social distribution and social meaning are not unconnected. Indeed, the social distribution of a linguistic feature creates the environment for the feature to be incorporated into social meaning. Guy and Hinskens (Reference Guy, Hinskens, Hinskens and Guy2016) suggested that speakers’ repertoire of linguistic features only takes on social meaning through the features’ social distributions and associations acquired in the community. That is, a linguistic feature may index the social associations and expectations typically held about the social group(s) that most use the feature. As a result, Podesva (Reference Podesva2008:3) proposed that features with similar social distributions across different speech communities come to acquire somewhat similar social meanings. He provided the example of (th)-stopping. In many speech communities, this variant is firstly most prevalent among the lowest socioeconomic classes (e.g., Labov, Reference Labov1966), and secondly, is broadly indexing of “toughness.” It seems that the social distribution of a linguistic feature enables the feature to take on indexicalities that may lead to the stylistic use of a feature.

In summary, social distribution is not a sufficient predictor of the rates of between-speaker co-variation between two linguistic features (Guy & Hinskens, Reference Guy, Hinskens, Hinskens and Guy2016). Instead, some, but not all, features with social distributions can acquire social meaning. The varying levels and configurations of social meaning held by different linguistic features may mediate the rates of co-variation between the features.

Community of Interest

This paper investigates rates of co-variation at the between-speaker level and clustering effects at the within-speaker level between (h) and (ing) in the casual speech of sixty-three speakers from Debden. The Debden Estate (or Debden) formed part of the “Cockney Diaspora.” This term refers to the twentieth-century relocation of white, working-class East Londoners out of London and into the surrounding counties, particularly, to Essex (Watt, Millington, & Huq, Reference Watt, Millington, Huq, Watt and Smets2014:121). Debden was built in the town of Loughton in 1949 as part of a series of government-led slum clearance programs that sought to depopulate and alleviate poverty in East London (Abercrombie, Reference Abercrombie1944). The vast majority of those who relocated to Debden in the 1950s were white, working-class East Londoners and many identified as Cockney. My paternal grandparents were relocated from East London to the Debden Estate in approximately 1950 and I was raised on the estate. In present times, although Debden is in the county of Essex, it is around five miles from the Northeast London border and around thirty-five minutes from central London on the London Underground train service (for a more detailed description of the history, location and demographics of Debden, see Cole & Evans, Reference Cole and Evans2020).

While there is much debate about how to define Cockneys, often Cockneys are considered to be white, working-class East Londoners, who were born/live in London's traditional East End (Fox, Reference Fox2015:8). Often, the accents spoken in South East England have been considered to occur on a continuum between Received Pronunciation (or its successor dialect, Standard Southern British English) and Cockney (see Altendorf & Watt, Reference Altendorf, Watt, Kortmann and Upton2008: Cole, Reference Cole2020). In South East England, the linguistic continuum between Standard Southern British English and Cockney parallels the class continuum. While Cockney people are often portrayed as epitomizing the working class in South East England (see Dodd & Dodd, Reference Dodd, Dodd, Strinati and Wagg1992), Standard Southern British English is the variety spoken by and associated with the higher classes (Agha, Reference Agha2003; Badia Barrera, Reference Badia Barrera2015).

As Debden was originally inhabited almost exclusively by East Londoners, it seems probable that Debden speakers will use consonantal features that have previously been reported in Cockney. This is in line with previous research that found that, despite some apparent-time change toward Standard Southern British English variants, a Cockney vowel system was brought to Debden along with the Cockneys who relocated (Cole, Reference Cole2020; Cole & Evans, Reference Cole and Evans2020; Cole & Strycharczuk, Reference Cole and Strycharczuk2019). Nonetheless, this paper does not have the scope to provide detailed descriptions of the variety of English spoken in Debden.Footnote 1 Instead, this paper principally investigates to what extent the differing social meanings held by linguistic variables can lead to an implicational relationship between them at both the within-speaker and between-speaker levels.

(ing) and (h)

The linguistic variables of interest are both phonological alternations present in Cockney with similar social distributions, being most prevalent in men and the working class. Nevertheless, these variables differ in their indexicalities. As I will demonstrate, in Debden, h-dropping has comparatively very high social prominence and holds locally meaningful associations in relation to the community's East London heritage. In contrast, g-dropping has much less social salience and, more broadly, indexes working-class or “improper” speech.

Social distribution of (h) and (ing)

The (h) variable refers to an alternation between the presence and absence of the glottal fricative /h/ in syllable initial position in non-function words. The term “h-dropping” is widely used to refer to the latter. While in most varieties of English, h-dropping is widespread for function words (for instance pronouns; he, him her, his and auxiliaries; has, have, had), h-dropping (or at least variability) is also found in non-function words in most urban centres across England and Wales (Hughes, Trudgill, & Watt, Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012:66–7).

In South East England, (h) has traditionally had a rigid social distribution, and h-dropping is found most prevalently among Cockneys. In 1982, Wells reported that among white, working-class East Londoners (or Cockneys), h-dropping was found almost categorically but was almost never found in Received Pronunciation speakers (Wells, Reference Wells1982:254). Around this time, research also demonstrated that h-dropping in London was strongly conditioned by social class. For instance, Hudson and Holloway (Reference Hudson and Holloway1977) showed that, in London, working-class schoolboys dropped /h/ on an average of 81% of instances, compared to 14% for middle-class boys. Previous research, although not conducted in East London, has also consistently established that h-dropping is more prevalent in men than women (Baranowski & Turton, Reference Baranowski, Turton and Hickey2015; Bell & Holmes, Reference Bell and Holmes1992). In the South East England context, the social distribution of h-dropping (highest prevalence among the working class, males, and prevelant in East London) may have enabled the feature to take on social meaning (Guy & Hinskens, Reference Guy, Hinskens, Hinskens and Guy2016; Podesva, Reference Podesva2008).

More recent work has found that /h/ has been reinstated in East London (Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill, & Torgersen, Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008:15) as well as other southern dialects in the towns of Reading and Milton Keynes (Williams & Kerswill, Reference Williams, Kerswill, Foulkes and Docherty1999:147). In the inner East London borough of Hackney, young speakers had significantly lower rates of h-dropping than elderly speakers (11% compared to 58.1%). Rates of h-dropping were also conditioned by speaker ethnicity. White British (or “Anglo”) speakers had significantly higher rates than "non-Anglo" speakers (18% compared to 3.9%) (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008:15). It may be that, in general, young speakers in the South East and in London are ideologically distancing from the indexicalities held by h-dropping. In line with these trends observed in Milton Keynes, Reading, and East London, /h/ may also be in a process of reinstatement in Debden.

The second variable analyzed as part of this study is (ing), which refers to an alternation between the standard velar [ŋ] and the alveolar [n] (though not for -ing after stressed vowels in monomorphemic words, e.g., ring, sing, etc.). The term “g-dropping” is used to signal the alveolar variant. While this term is problematic in that it uses the pejorative and erroneous term “dropping” to refer to the substitution of one phoneme for another, it will be employed throughout this paper for clear reference to the alveolar variant and for easy comparison with h-dropping.

The alveolar variant is strongly favored in East London (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012:77; Labov, Reference Labov1989; Mott, Reference Mott2012:84). Rates of g-dropping are also conditioned by social factors in both the US and the UK. The alveolar is more common in men than women and in the lower classes (Labov, Reference Labov2001; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill1974; Wells, Reference Wells1982). The social distribution of (ing) is stable, as change has not been observed in any of the locations where the variable has been analyzed throughout decades (Hazen, Reference Hazen2008; Labov, Reference Labov2001).

In the United States, the alveolar variant is more strongly favored in verbal contexts than in nominal contexts (Houston, Reference Houston, Trudgill and Chambers1991; Labov, Reference Labov1994:583, Reference Labov2001:79), but this effect was not found for London-born adolescents (Schleef, Meyeroff, & Clark, Reference Schleef, Meyerhoff and Clark2011:222). As well as differences between nominal and verbal contexts, in the United States (ing) operates differently for -thing words (while something and nothing favor the alveolar variant, anything and everything categorically favor the velar; see Campbell-Kibler [Reference Campbell-Kibler2006:23]; Labov [Reference Labov2001:79]). The clear division between alveolar and velar endings in -thing words was not found to be as clearly marked in Britain as in North America (Houston, Reference Houston1985). In some very limited varieties of English, a third variant, [-ɪŋk] is also found for -thing words. These varieties include the English used in Canberra, Australia (Shopen, Reference Shopen1978) and Cockney (Schleef et al., Reference Schleef, Meyerhoff and Clark2011; Wright, Reference Wright1981). In this study, I refer to this variant as the “[-ɪŋk]” variant, and I use the term “velar variant” to refer to the standard [-ɪŋ] variant.

Social meaning of (h) and (ing) in Debden

(h) and (ing) appear to differ in their potential indexicalities that may lead to an implicational relationship between the two features. In Britain, there is evidence spanning centuries that h-dropping has drawn overt, social commentary, including in relation to Cockney. The feature has been observed since as early as the sixteenth century and appears to have been stigmatized throughout this period (Mugglestone, Reference Mugglestone2003). For instance, in 1791, John Walker published A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary that provided pronunciation advice to the Scottish, Irish, and, above all, Cockneys, who Walker believed spoke a variety of English “a thousand times more offensive and disgusting” (Walker, Reference Walker1791:17). The publication includes a list of “faults” commonly produced by Cockneys, including h-dropping and hypercorrection: “not founding ‘h’ where it ought to be found, and inversely.”

In modern times, there is ongoing evidence that h-dropping has high social prominence and is associated with Cockney. Indeed, Wells considered the feature to be “the single most powerful pronunciation shibboleth in England” (Wells, Reference Wells1982:254). Evidence for the association between Cockney and h-dropping can be found in online instructional videos that guide viewers on how to impersonate a Cockney accent. Without fail, these videos mention h-dropping as a key facet of a Cockney accent and encourage users to emulate this feature in order to sound Cockney. These pop-cultural references suggest that h-dropping is indexing of Cockney and could be considered an enregistered (cf., Agha, Reference Agha2003; Johnstone et al., Reference Johnstone, Andrus and Danielson2006) feature in the Cockney variety of English. That is, h-dropping has become overtly linked with the “Cockney” accent or dialect label.

Evidence for the enregisterment of h-dropping in Cockney is perhaps best demonstrated in the Cockney song (or “ding dong”) Wot's the good of hanyfink! Why! Nuffink! (for the full lyrics and piano music see Keeping [Reference Keeping1975:35]). The chorus lyrics are represented orthographically as:

The song finds humor in drawing overt attention to h-dropping in Cockney. In all instances where /h/ would be expected in standard British English it is removed (e.g., “humbug” becomes “umbug”), and vice versa (e.g., “earn” becomes “hearn”). The strategic and humorous use of h-dropping and hypercorrection in this song demonstrates a conscious awareness of h-dropping. The feature is indexing of Cockney and is used in stylistic projections.

With respect to (ing), the above song also includes orthographic representation of the [-ɪŋk] variant for -thing words, demonstrating some level of awareness of this feature. Furthermore, there are orthographic representations of g-dropping in non-thing words such as tryin’, ravin’, and savin.’ This attests the fact that speakers are familiar with the alternation. Nonetheless, of the previously mentioned videos that guide speakers to emulate a Cockney accent, with very few exceptions there are no mentions of g-dropping as a feature of Cockney. This chimes with previous research suggesting that, unlike in the United States, g-dropping does not draw overt social commentary and evaluations in the UK (Levon & Fox, Reference Levon and Fox2014). In Labovian terms, (ing) appears to be a marker while (h) is a stereotype (Labov, Reference Labov1972).

In Debden, interviews with participants also revealed discrepancies in the social prominence and indexicalities of (h) and (ing). For instance, in the below excerpt h-dropping is discussed by three participants from Debden (a 48-year-old woman, Jane, her 54-year-old husband, Brian, and her 75-year-old father, Michael).

Brian2: Well, it seems - it seems to me that if people can't pronounce their words properly, they seem to–they assume you come from London, init. If they're not saying their t's or h's or anything like that, there's–they'll say, “Oh, you come from London then, don't you?”

Jane: Oh, my nan though. She used to tell me off ‘cause I didn't sound my t's and h's.

Michael: Yeh, but why? She come from Shoreditch. What? She ashamed of it or summink [something]?

Jane: No, she always used to make me sound my letters, didn't she? And um, I mean, it was only when I had children–when I–when I had [my son] that I actually pronounced– started making sure that I pronounced my t's and h's so that it was–he ended up speaking lovely but then it–then it just went again. Went back to normal.

Michael: I suppose it sounds–it sounds better–it sounds nicer if you talk properly.

Although Michael ultimately concedes that it sounds “better” to talk “properly,” he initially seems offended by Jane's suggestion that h-dropping is shameful. He understands h-dropping as an indicator of their Shoreditch heritage (a traditionally Cockney area of East London). Similar sentiments arose frequently across the interviews in Debden. Therefore, h-dropping encompasses associations of working-class or “improper” speech but also indexes more local interpretations in relation to Debden's cultural heritage in East London. H-dropping may not explicitly index the linguistic label “Cockney,” or even “East London,” due to the community's relocation to Essex. Indeed, it has been found that young speakers in Debden have reinterpreted some “Cockney” linguistic features as an “Essex” accent (Cole & Evans, Reference Cole and Evans2020). Nonetheless, h-dropping does certainly seem to index something local and related to the community's working-class, East London heritage.

In contrast, participants in this present study rarely referenced g-dropping. Of the limited instances in which the feature was mentioned, it was associated with working-class, “improper,” and “incorrect” speech. For instance, in the below excerpt, a 51-year-old woman, Denise, describes her feelings of shame around her accent, which she does not believe is “proper.” After being mocked for her accent by her colleagues, she attempted to speak “better” for an entire day. As part of these efforts, she aims to “add ‘g’ on the end of words,” thus using the standard velar as opposed to the alveolar. However, she ultimately acknowledges that “speaking better” is “not [her],” such that her accent (of which g-dropping is part) is intrinsic to her sense of self. Although Denise associated g-dropping with “incorrect” or “improper” speech, she does not explicitly relate this feature with any local meaning.

I was saying, ‘I'm going to speak much better today, I'm going to speak and I'm going to say all my words properly and all my letters properly.’ And they were laughing at me ‘cause I suppose I'll say ‘laughin’’ and ‘jokin’’ and we don't put a ‘g’ on the end and–but I know–it was far too much effort ‘cause it's not me, is it?

In summary, although both g-dropping and h-dropping are supraregional in England, they differ in the extent and configuration of their social meaning in Debden. There is no substantial evidence to suggest that g-dropping has locally meaningful associations in Debden where it is broadly associated with working-class and “improper” speech. In contrast, h-dropping carries locally meaningful and overt indexicalities related to the community's Cockney heritage.

Hypotheses of this study

In terms of the distribution of (h) and (ing), as Debden is a working-class community with East London heritage, we would firstly expect that, at least to some extent, h-dropping and g-dropping will be present. Secondly, we would expect rates of both h-dropping and g-dropping to be more frequent among Debden men than women. Thirdly, it seems likely that h-dropping will be in a state of change toward reinstatement in line with changes observed in South East England (Williams & Kerswill, Reference Williams, Kerswill, Foulkes and Docherty1999:147) and London (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008:15). In contrast, (ing) is likely to be stable in apparent time following a wide range of work that has found the variable to be stable (see Labov, Reference Labov2001).

The principal hypothesis of this paper is that the differing social meanings held by linguistic features can lead to an implicational relationship between them. The prediction is that rates of h-dropping will be contingent on rates of g-dropping as the indexicalities of the latter (working-class and “improper”) are incorporated in the superordinate indexicalities of the former (Cockney heritage). Firstly, I investigate to what extent h-dropping and g-dropping cluster together in the speech of individual speakers. That is, I hypothesize that, if a speaker produces h-dropping, they will predictably produce the alveolar variant of (ing) if the variable occurs in proximity. In contrast, g-dropping may occur in proximity to any value of (h). I measure the distance between (h) and (ing) with a novel approach: using the number of phonemes as the denomination of distance. Secondly, I investigate to what extent the features co-vary at the between-speaker level. The hypothesis is that speakers with high rates of h-dropping must also have high rates of g-dropping. In contrast, a high rate of g-dropping does not necessitate high rates of h-dropping. While it is possible for a Debden speaker to index working-class speech without indexing their Cockney heritage, the reverse is not possible.

METHODS

Participants

Ranging from fourteen to ninety-one years of age (M = 49.3yrs, SD = 23.8), sixty-three participants (thirty-six female) were recruited from the Debden Estate using a friend-of-a-friend approach. The participants’ ages reflect their age at the time of recording in 2017. As previously mentioned, my grandparents were relocated to Debden from East London in approximately 1950 as part of the slum-clearance programs, and I was brought up in Debden. As a result, the data was mostly collected through my network of friends and family. All participants were white and from historically working-class, East London families, as ascertained through employment and educational patterns.

Procedure

The speakers took part in a sociolinguistic interview, consisting of reading a wordlist and passage as well as an open interview with myself, a native Debden speaker. The production data for this paper is extracted from the open interviews (see Cole & Evans [Reference Cole and Evans2020] or Cole & Strycharzuk [Reference Cole and Strycharczuk2019] for phonetic analyses of wordlist and passage data). The interviews consisted of semistructured conversations about a range of topics with a focus on the participants’ lives, views on the local area, experiences living in Debden, sense of identity, and the linguistic features found in Debden.

The recordings were mostly conducted one-on-one, but seven interviews were conducted in groups of up to four friends or family members. Interviews were a minimum of twenty minutes, a maximum of three hours, and averaged fifty minutes. The interviews were transcribed with Elan (Version 5.4) (Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, 2019) in full except for nine longer ones capped at fifty minutes per speaker. The interviews were aligned with FAVE align (Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini, Seyfarth, Gorman, Prichard, & Yuan, Reference Rosenfelder, Fruehwald, Evanini, Seyfarth, Gorman, Prichard and Yuan2014). A hand-coding, Praat script was then used to code auditorily for (h) and (ing) (Fruehwald, Reference Fruehwald2011). Function words, such as pronouns or auxiliaries, were not included for (h). Although, as previously mentioned, hypercorrection of h-dropping may be indexing of Cockney, no instances of hypercorrection were found in the data. Therefore, hypercorrection was not analyzed. For (ing), instances of -ing after stressed vowels in monomorphemic words (e.g., ring, sing, etc.) were not included, and-thing words were analyzed separately, as they have been shown to operate differently to other -ing words (see Campbell-Kibler, Reference Campbell-Kibler2006).

This gave a total of 2,183 tokens of (ing) for non-thing words, 492 tokens of (ing) for -thing words, and 4,058 tokens of the (h) variable.

Analysis

Variation and Change in (h) and (ing)

Firstly, the social distribution of (ing) and (h) was analyzed using logistic mixed effect regressions using the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Core Team, 2018). The dependent variables were the realizations of (ing) and (h) across all participants. The first analysis investigated rates of (h), the second and third analyzed rates of (ing) for -thing and non-thing words respectively. Of the sixty-three participants, four participants were not included in the analysis of -thing words, as they did not produce any -thing word during the interview. As the production of -thing words has three potential variants in Cockney [ɪŋ, ɪn, ɪŋk], three separate models were run to test each possible comparison of variants in the dependent variable: (1) [ɪŋ] and [ɪn]; (2) [ɪŋ] and [ɪŋk]; (3) [ɪn] and [ɪŋk]. For all analyses, statistical significance was tested with α set at 0.05.

The predictors included in the models were age (continuous), sex (female: n = 36; male: n = 27), and an interaction between these two variables. The sex predictor was treatment-coded (F = 0, M = 1). Participant and word were included as random effects to control for any participant or word-specific effects (words: n = 315 and n = 307 for (ing) and (h) respectively). For -thing words, carrier words were included as a predictor (anything, everything, something, or nothing: n = 109, 84, 93, 206, respectively). This predictor was included, as word-specific variation has been observed in the realization of (ing) (Campbell-Kibler, Reference Campbell-Kibler2006:23; Houston, Reference Houston1985; Labov, Reference Labov2001:79). Further, for the analyses of (ing) (for both -thing and non-thing words), the place of articulation of the following phoneme was also included as a predictor. Expanded from Tamminga (Reference Tamminga2016:339), this was coded as either (1) alveolar, (2) velar, or (3) neither alveolar nor velar (non-thing words: n = 315, 89, 1779, respectively; thing-words: n = 94, 6, 392, respectively). The only phonological conditioning that has been observed for this variable is in the form of regressive assimilation whereby the alveolar variant is more frequent when it precedes alveolar stops, and the velar variant is more common when preceding velar stops (see Campbell-Kibler [Reference Campbell-Kibler2006] for an overview). For each dependent variable, I fitted full models based on all the predictors listed above and tested for significance of the individual predictors by removing them step-by-step and comparing the model fit.

Although, in the United States, g-dropping is morphologically conditioned such that it is more likely in verbal than nominal contexts (Labov, Reference Labov2001:79), this effect was not found for London-born teenagers (Schleef et al., Reference Schleef, Meyerhoff and Clark2011:222), and, thus, nominal and verbal contexts have been analyzed together. No linguistic constraints were included in the analysis of (h), as the variable is not considered to have phonological or morphological conditioning, with the exception of the possibility that the quality of /h/ (but not its presence or absence) may differ depending on the following vowel (see Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012: 45; Ladefoged & Maddieson, Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996).

In each model, the vernacular variant of the dependent variable (h-dropping for (h) and g-dropping for (ing)) was coded as zero and the standard was coded as one. For the comparison between [-ɪŋk] and alveolar variants for -thing words, the [-ɪŋk] variant was coded as zero.

Co-variation and clustering between (h) and (ing)

At the within-speaker level, I analyzed to what extent h-dropping and g-dropping cluster together in the speech of individual speakers. The temporal distribution of style clusters within an individual speaker's discourse has been analyzed with different temporal units, such as utterance (Podesva, Reference Podesva2008; Sharma & Rampton, Reference Sharma and Rampton2015), discourse topic (Schilling-Estes, Reference Schilling-Estes2004), and tokens (Kendall, Reference Kendall2007). In this study, I use a novel approach to analyzing clustering effects by using number of phonemes as the denomination of distance between (h) and (ing). Rates of co-variation between (h) and (ing) were analyzed when the variables were, firstly, two phonemes apart in an utterance, secondly, three phonemes apart, thirdly, four phonemes apart, etc. The analysis continued until the point at which there was no significant co-variation between (h) and (ing) given the distance between them. For instance, would (h) and (ing) co-vary when they were three phonemes apart when produced in words such as “(h)av(ing),” or when they were six phonemes apart in phrases, such as “Music (h)all tak(ing)”?

A drawback of this method is that the phonetic realizations of the phonemes between (h) and (ing) were not adjusted for all phonological processes. In some instances, this may have altered the number of phonemes between (ing) and (h), for instance, if linking/intrusive-r or schwa deletion occurred. Nonetheless, there were very few instances when the number of phonemes between (h) and (ing) would have been altered by these phonological processes.

For each individual speaker, the probability of h-dropping occurring in proximity to g-dropping (for non-thing words) was calculated as follows: the number of times h-dropping occurred within X phonemes of g-dropping was divided by the number of times h-dropping occurred within X phonemes of (ing) (regardless of surface variant). This resultant probability was then contrasted with the probability of h-dropping occurring independently of its surrounding environment. That is, is the rate of speakers producing h-dropping within X phonemes of g-dropping higher than speakers’ overall rates of h-dropping throughout the interview? These probabilities were contrasted with a Mann-Whitney U test. The same process was then conducted to assess whether the probability of g-dropping in proximity to h-dropping was greater than the probability of g-dropping occurring independently of its surrounding environment.

For each analysis, only participants who had more than five occurrences of (h) and (ing) within X phonemes were included in the analysis so as to increase the reliability of results. For instance, twenty-five participants were included in the analysis of (h) and (ing) within three phonemes; this increased to forty-five participants within ten phonemes. An analysis of (h) and (ing) in immediately adjacent positions was not analyzed, as there were not enough instances of occurrence to provide sufficient statistical power. While not all participants could be included in the analysis in the interest of reliability and accuracy of results, this analysis was not looking at community-wide patterns in the first instance, but instead was interested in within-speaker patterns that could be interpreted independently. Clustering between (h) and -thing words could not be analyzed due to the limited number of realizations of -thing words across the corpus (492).

At the between-speaker level, rates of co-variation between (h) and (ing) (for non-thing words) were analyzed with a Pearson's correlation test. This test assessed whether speakers with relatively higher rates of g-dropping also had relatively higher rates of h-dropping (and vice versa).

RESULTS

Variation and change in (h) and (ing)

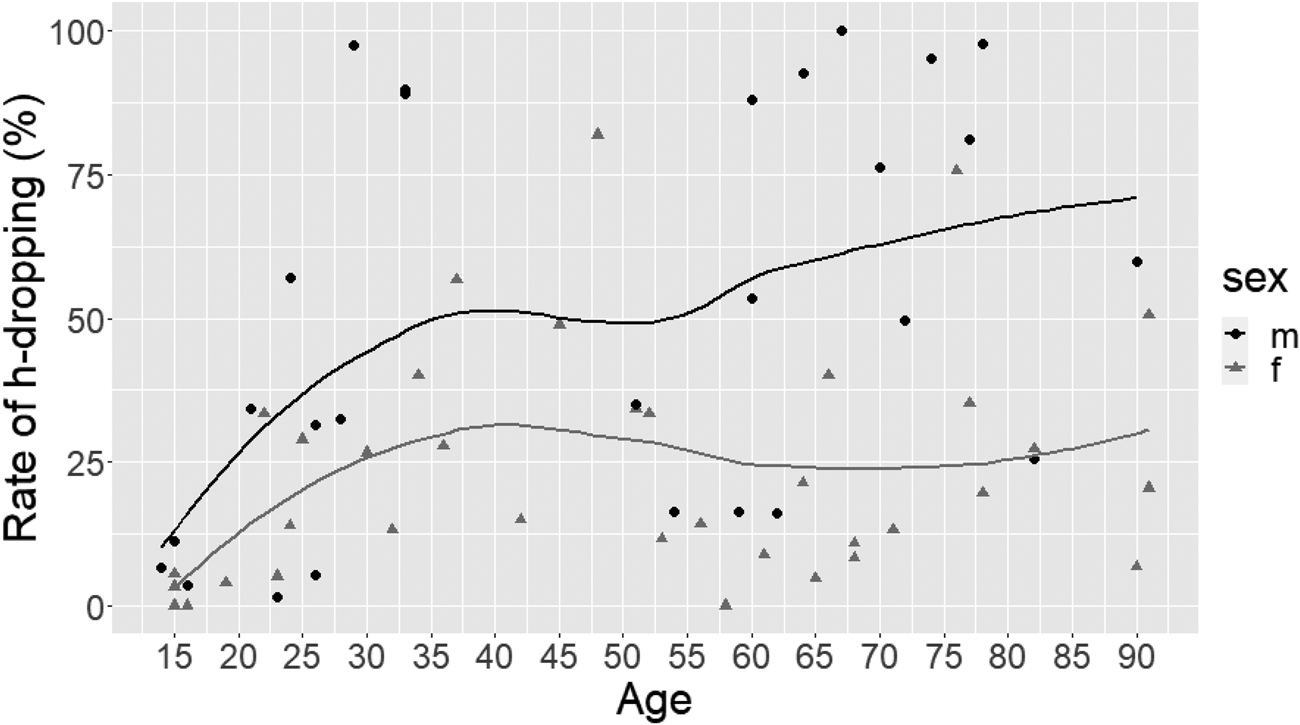

Logistic mixed effect regressions investigated to what extent rates of (ing) and (h) were related to age and sex. Both age (β = −0.04, z = −3.56, p < 0.001) and sex (β = −1.95, z = −3.81, p < 0.001) were significantly related to the rates of (h) (see Figure 1). Males had higher rates of h-dropping than females (48.4% h-dropping for men compared to 23.3% for women) and older participants had higher rates than younger participants. Change toward the retention of /h/ was observed most abruptly in those aged ≤ 35yrs. Retention of /h/ was very low among adolescents and almost categorical for female adolescents. While there was not a reduction in rates of h-dropping for women aged between thirty-five years and ninety-one years, there was a steady apparent-time decrease for men in this same age bracket. However, for both sexes, change toward retention occurred most abruptly in those aged ≤ 35yrs. There was no significant interaction between age and sex.

Figure 1. Rates of h-dropping by age and sex for sixty-three speakers from Debden, Essex. H-dropping is significantly more likely in older speakers (particularly those aged >35yrs) and in men.

For (ing) in non-thing words, there were no significant age or sex effects or interactions between these variables (Figure 2) (the velar form occurred on 17% of instances for males and 15.8% for women). The only significant effect in the model was the place of articulation of the following sound. The velar form was significantly more likely to occur when the following sound was velar (64% of instances) compared to when it was alveolar (13.7%) or neither alveolar nor velar (22%) (β = −2.23, z = 5.83, p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Rates of g-dropping for non-thing words by age and sex for sixty-three speakers from Debden, Essex. There are no significant sex or age effects in rates of (ing).

As found in previous research, in Debden, (ing) operates differently for -thing words compared to non-thing words. In Figure 2, for nearly all speakers, the alveolar form was favored across all ages for non-thing words. In contrast, the velar variant was favored for -thing words (Figure 3). For -thing words, no significant effects were found in the model that compared rates of production of the velar variant and the [-ɪŋk] variant. However, a significant age effect was found in the comparison between the alveolar form and [-ɪŋk] form (β = −0.15, z = −2.12, p = 0.03). Young speakers were more likely to use the alveolar and less likely to use the [-ɪŋk] form. There were no other significant main effects or interactions.

Figure 3. Rates of (ing) by age and word for -thing words for fifty-nine speakers in Debden, Essex. While the velar variant is most prevalent for all words across all ages, the youngest speakers increasingly favor the alveolar variant.

For the comparison between rates of the alveolar and the velar variants, the velar form was more likely if the following sound was a velar. This concorded with the finding for non-thing words. There was also a significant age effect: young speakers were more likely to use the alveolar and less likely to use the velar (β = −0.07, z = 2.77, p < 0.01). There was also a significant effect for carrier word. The word something operated differently from the other -thing words (β = −2.89, z = −2.72, p < 0.01). There was also a significant interaction between the production of the word something and age (β = −0.05, z = −2, p = 0.04). An apparent-time decrease in rates of the velar form and an increase in the alveolar form was found for anything, nothing, and everything. This effect was not found for something where rates of each variant have remained relatively stable in apparent time. The findings in Debden differ from the research conducted in the United States where anything and everything categorically favor the velar, while nothing and something comparatively favor the alveolar (see Campbell-Kibler, Reference Campbell-Kibler2006:23; Houston, Reference Houston1985; Labov, Reference Labov2001:79).

In summary, (h) is in an advanced process of reinstatement in Debden, which is almost complete in adolescents. Rates of h-dropping are higher in males than females across all ages. For non-thing words, the alveolar variant of (ing) is favored by all ages, and there are no significant apparent-time changes or sex differences. For -thing words (except for something), the velar form is favored by almost all ages and for all words except for the youngest speakers. In comparison to older speakers, young speakers increasingly disfavor the velar [-ɪŋ] or the [-ɪŋk] forms in favor of the alveolar variant. There are no significant differences in the comparison between the standard velar and the [-ɪŋk] variants.

Co-variation and clustering between (h) and (ing)

Clustering effects between (h) and (ing) within the speech of individual speakers was tested with Mann-Whitney U tests. Speakers were significantly more likely to produce h-dropping in proximity to g-dropping compared to the probability of them producing h-dropping independently of its surrounding environment. Likewise, g-dropping was significantly more likely to occur if h-dropping had occurred in proximity compared to the probability of g-dropping occurring independently. These effects were only significant when (ing) and (h) occurred within two or three phonemes of each other (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) (Figure 4). Nonetheless, although not significant, a tendency for co-occurrence persists across a wider phoneme window.

Figure 4. In Debden, Essex, speakers are significantly more likely to produce h-dropping within two (left panel) or three (right panel) phonemes of g-dropping compared to the probability of h-dropping occurring independently (and vice-versa). "h→∅" refers to the probability of h-dropping occurring independently of any surrounding environment. "h→∅ | ŋ→n" refers to the probability of h-dropping occurring given the fact that g-dropping has occurred.

As demonstrated in Figure 4, the rate of h-dropping when g-dropping occurred within two or three phonemes was greater than 50% and 33% respectively for all speakers. In contrast, when (h) was analyzed independently of surrounding environment, rates of h-dropping were almost null for some participants. Each individual speaker had a higher probability of h-dropping within both two and three phonemes of g-dropping, compared to the probability of that same speaker h-dropping throughout the interview. Similarly, all speakers were more likely to g-drop in proximity to h-dropping compared to their rates of g-dropping throughout their interviews. On all instances, for all speakers, g-dropping was the resultant variant when (ing) occurred within two or three phonemes of h-dropping. That is, on no instance did any single speaker produce the velar variant of (ing) within either two or three phonemes of h-dropping.Footnote 3

At the between-speaker level, rates of co-variation between (h) and (ing) (for non-thing words) were analyzed with a Pearson's correlation test. There was a significant correlation between speakers’ rates of (h) and (ing) (t(61) = 2.97, p = 0.04, r = 0.36). While this correlation was significant, it was weakened by an implicational relationship between (h) and (ing) (Figure 5). Speakers who had high rates of h-dropping always had high rates of g-dropping. However, speakers with high rates of g-dropping had variable rates of h-dropping (ranging from 0% to 100%).

Figure 5. There is a weak correlation (r = 0.36) between rates of (ing) (for non-thing words) and (h) for sixty-three speakers in Debden, Essex. There is an implicational relationship between these features: while h-dropping implies g-dropping, the reverse is not true.

DISCUSSION

This paper investigated to what extent the differing social meanings held by linguistic features can lead to an implicational relationship between them. Rates of co-variation between (ing) and (h) at the between-speaker level were investigated as well as clustering effects at the within-speaker level. This paper hypothesized that there would be an implicational relationship between (ing) and (h) as a result of their distinct but overlapping social meanings. That is, I predicated that h-dropping may be contingent on g-dropping as the indexicalities of the former (Cockney heritage) are superordinate to and incorporate the indexicalities of the latter (working-class and “improper”).

This hypothesis was confirmed at both the within-speaker and between-speaker levels. Speakers with high rates of h-dropping necessarily had high rates of g-dropping. In contrast, speakers with high rates of g-dropping had variable rates of h-dropping. This implicational relationship weakened the correlation coefficient between (h) and (ing). That is, it is possible to be a g-dropper who does not h-drop, but it is not possible to be an h-dropper who does not g-drop. To some extent, an implicational relationship between (h) and (ing) was also found within the speech of individual speakers. The probability of h-dropping was greater when (h) occurred within two or three phonemes of g-dropping compared to the probability of h-dropping occurring independently of its surrounding environment. The same effect was found but to a greater extent for (ing). If (ing) occurs in proximity to a dropped /h/, the resultant variant is always g-dropping and never retention. That is, for Debden speakers, it is possible to g-drop in proximity to a retained /h/. However, it is not possible to produce the velar variant of (ing) within two or three phonemes of h-dropping.

The implicational relationship between h-dropping and g-dropping seems to be mediated by the features’ different social meaning. In Debden, h-dropping is a locally meaningful dialect feature with indexicalities related to the community's Cockney heritage. In contrast, g-dropping does not carry local interpretations and, more generally, indexes working-class or “improper” speech. The indexicalities of h-dropping encompass and are superordinate to those of g-dropping. In general, a speaker in Debden may wish to index working-class speech more broadly without indexing more specific, local meaning around Cockney. However, a speaker cannot index their Cockney heritage without necessarily also indexing working-class speech. As a result, h-dropping implies g-dropping, but g-dropping can occur independently of h-dropping.

These results support an approach to sociolinguistic style which considers language to be a fluid and symbolic resource to project identity and affiliation. Linguistic features are not independent of each other, and, instead, the social meaning of linguistic features can combine to create a collective social meaning (Campbell-Kibler, Reference Campbell-Kibler2011; Coupland, Reference Coupland2007; Pharao et al., Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Møller and Kristiansen2014; Pharao & Maegaard, Reference Pharao and Maegaard2017). It has previously been demonstrated that language features that jointly index a certain style can cluster together in the speech of individual speakers (Podesva, Reference Podesva2008; Sharma & Rampton, Reference Sharma and Rampton2015). This result was confirmed by this paper: h-dropping and g-dropping did significantly cluster together within the speech of individual speakers. Nonetheless, this paper has expanded on this research to demonstrate an implicational relationship between linguistic variables as a result of their differing social meanings. That is, clustering effects between the features may not be entirely mutual as a result of the features’ differing social meanings.

In general, it seems that young speakers in Debden (most notably those aged ≤ 35yrs) are moving away from features that index Cockney or their East London heritage but have maintained features that have indexicalities more generally around working-class speech. As a result, although for non-thing words (ing) is stable with high rates of the non-standard alveolar variant across all speaker groups in Debden, /h/ is in an advanced process of reinstatement. This is in line with the reinstatement of /h/ in the southeastern towns of Milton Keynes and Reading (Williams & Kerswill, Reference Williams, Kerswill, Foulkes and Docherty1999:147) as well as in East London (Cheshire et al., Reference Cheshire, Fox, Kerswill and Torgersen2008:15). Dialects in South East England are typically conceived of as a linguistic continuum that parallels the class continuum from the most vernacular, localized, and working-class dialect, Cockney, to the most standard, supralocal, and higher-class dialect Standard Southern British English (Altendorf & Watt, Reference Altendorf, Watt, Kortmann and Upton2008; Cole, Reference Cole2020; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Trudgill and Watt2012; Wells, Reference Wells1997). Therefore, southeastern working-class speech norms incorporate, to some extent, many features of Cockney. Nonetheless, h-dropping, but not g-dropping, has often been cited as a key feature differentiating Cockney from more general southeastern speech patterns (Wells, Reference Wells1992). In Debden, then, young speakers are moving away from linguistic features that hold local associations with Cockney such as h-dropping, and, instead, favor features more broadly indexing southeastern working-class speech such as g-dropping in non-thing words.

The results for -thing words provide further evidence that working-class speech norms and not Standard Southern British English are the target of linguistic change in Debden (see also the Cockney vowel system: Cole & Evans, Reference Cole and Evans2020). Young speakers are moving away from both the standard velar form and the [-ɪŋk] form in favor of the alveolar form. It initially seems contradictory that young speakers are shifting away from both the most vernacular, Cockney variant [-ɪŋk] and the standard, velar form [ɪŋ]. Nonetheless, it may not be helpful in this instance to consider the velar variant solely as the standard form. The velar variant was favored among even the oldest speakers in Debden who strongly identify as Cockney, lived in East London into adulthood, and have many traditionally Cockney linguistic features. Perhaps it would be most accurate to consider the velar form as a Cockney variant. It may be that the velar form is, to some extent, a reduced variant of the traditional Cockney [-ɪŋk] form with which it shares the velar component [ŋ]. Indeed, no significant apparent-time changes were found between rates of the [-ɪŋk] and the “standard” velar form, suggesting that the forms are not diverging. In Debden, then, young speakers are shifting away from localized, "Cockney" forms toward broader, southeastern, working-class norms. Thus, for -thing words, young speakers are shifting toward alveolar variants.

In summary, in Debden, young speakers are moving away from localized linguistic features that index the community's Cockney heritage such as h-dropping and the [-ɪŋk] form (and potentially the velar form) of -thing words. In contrast, young speakers have maintained traditional “Cockney” features that represent broader, southeastern, working-class norms, such as the alveolar form of (ing) for non-thing words. Furthermore, young speakers are increasingly favoring the nonstandard alveolar form for -thing words and not the “standard” velar [-ɪŋ] variant or the most vernacular, traditional Cockney [-ɪŋk] form. The overlapping but distinct social meanings held by h-dropping and g-dropping (for non-thing words), has also led to an implicational relationship between the features at both the within-speaker and between-speaker levels. In order for speakers to index more local meaning related to their East London heritage, they must necessarily encompass broader working-class norms. As a result, there is a clustering effect in the speech of individual speakers between h-dropping and g-dropping. Although these results need to be replicated to explore the generalizability of the results, this paper has demonstrated that the differing social meanings held by linguistic features can lead to an implicational relationship between them.