“This sexy, lush, complex, perfumed Pomerol […] is fleshy, silky, and voluptuous in its elegant, feminine style.”

—Robert Parker Jr., about Hosanna 1999I. Introduction

Gender identity is defined as the result of a social construction (Lorber, Reference Lorber, Grusky and Szelényi2018) that influences both attitudes and behaviors (Zayer and Pounders, Reference Zayer, Pounders, Kahle, Lowrey and Huber2022). Gender differences are well documented in wine information searches (Barber, Dodd, and Kolyesnikova, Reference Barber, Dodd and Kolyesnikova2009), visitor perceptions of a winery’s wine and service (Mitchell and Hall, Reference Mitchell and Hall2001), and wine drinking patterns (Forbes, Reference Forbes2012). More recently, gender differences have been highlighted on the supply side of the wine industry, with differences in terms of careers (Bryant and Garnham, Reference Bryant and Garnham2014), management style and leadership (Galbreath and Tisch, Reference Galbreath and Tisch2020), and performance (D’Amato, Reference D’Amato2017). Most products, services, and brands also have a gender (Grohmann, Reference Grohmann2009), which can be constructed when masculine or feminine cues (visual or semantic) are displayed (Spielmann, Dobscha, and Lowrey, Reference Spielmann, Dobscha and Lowrey2021).

Gender dimensions of brands include symbolic aspects that influence a consumer response in the marketplace. Traditionally, elements considered masculine are associated with competence, while elements considered feminine are associated with warmth (Hess and Melnyk, Reference Hess and Melnyk2016; Pogacar, et al., Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021). Schnurr (Reference Schnurr2018) shows that when pursuing hedonic (utilitarian) consumption goals, products perceived as feminine (masculine) are generally preferred over those perceived as masculine (feminine), with no differences between consumer genders. Similarly, Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) show that feminine brands (the masculinity/femininity of a brand can be inferred by linguistic cues) are perceived as warmer, which gives them an advantage over masculine brands. This advantage is all the greater when the products associated with these brands are hedonic (vs. utilitarian).

In this article, we focus on wine, which is often associated with a particular gender. Fugate and Phillips (Reference Fugate and Phillips2010, p. 256) note that “wine, originally labelled ‘masculine’, was categorized as ‘feminine’ in this research, indicating a 180-degree shift in the gender identity of this product,” largely attributed to popular media and entertainment. Certain grape varieties and winemaking techniques produce particularly fine, delicate, and elegant wines, frequently described as feminine. Conversely, adjectives such as powerful, tannic, bold, and strong are associated with masculinity. Indeed, anthropomorphic metaphors associating wine with a person are often used in wine discourse (Normand-Marconnet and Jones, Reference Normand-Marconnet and Jones2020). Peynaud (Reference Peynaud1980) proposed a model of wine evaluation based on three axes, including a “masculine/feminine” axis. As summarized by Lehrer and Lehrer (Reference Lehrer, Lehrer and Allhoff2008, p. 114), ‘‘wines are described as masculine or feminine, muscular or sinewy, for example, in addition to being described as heavy or light, delicate or harsh.’’

Livat and Jaffré (Reference Livat, Jaffré, Charters, Demossier, Dutton, Harding, Maguire, Marks and Unwin2022) identify two main areas of gender-related research in the wine context. One is the issue of gender and its impact on wine choice, consumption, purchase, and appreciation. The other area focuses on women and their influence in the wine value chain. In this article, we look at a third area, the gender of wine as such. It should be noted that the gender of wine, as conveyed by the wine vocabulary, is a social construct, as is the expression of terroir (Castello, Reference Castello2021). We are interested in the gendered description—or gender profile—of a wine and its implications for quality and price. More specifically, by analyzing expert tasting notes, we aim to assess:

(i) The gender profile of wines and its evolution over time. Women are becoming increasingly important on both the supply and demand sides of the market. Therefore, one can expect wine to become more feminine.

(ii) The relationship between a wine’s gender profile and its score. As feminine linguistic attributes for gendering products improve consumer attitude (Pogacar et al., Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021), the gender profile of the wine can also have an impact on the wine’s rating.

(iii) The relationship between a wine’s gender profile and its drinking window. More masculine wines tend to have a stronger structure (more tannins and acidity) and should therefore have a longer aging potential.

(iv) The relationship between a wine’s gender profile and its price. Scores and aging potential correlate with wine prices (see, e.g., Ashenfelter, Ashmore, and Lalonde, Reference Ashenfelter, Ashmore and Lalonde1995). Thus, if propositions (ii) and (iii) are verified, a wine’s gender profile should also correlate with its price.

Our results show that some wines are indeed described as more feminine than others, but their prevalence has not increased over time. Moreover, feminine-related wine descriptors do not significantly correlate with scores and prices, but they can be associated with wines benefiting from a shorter drinking window.

II. Background

a. Gendered wine preferences and gendered wine vocabulary

Gender differences in wine consumption behavior and attitudes have been observed across studies. Some have found that the ability to discriminate odors and tastes in wine is more acute in women than in men (Doty et al., Reference Doty, Applebaum, Zusho and Settle1985). While women are often the primary wine purchasers, they are more concerned about making the “wrong” wine decision than men (Barber, Almanza, and Donovan, Reference Barber, Almanza and Donovan2006), seeking information from knowledgeable professionals, and leaving higher-priced or special occasion purchases to their male counterparts (Atkin, Nowak, and Garcia, Reference Atkin, Nowak and Garcia2007).

Wine preferences may differ by gender. Some researchers report a stronger preference for young and sweet wines among women, especially younger women, than among men, although both women and men prefer dry wines (Bruwer, Saliba, and Miller, Reference Bruwer, Saliba and Miller2011). Similarly, while men have a strong preference for red wines, women appreciate both red and white wines. They prefer wines with vegetal characteristics, fruit aromas, and mouthfeel, while men prefer older wines (Bruwer, Saliba, and Miller, Reference Bruwer, Saliba and Miller2011). Women also look for wines with vanilla, floral, and spicy aromas. They are less interested in earthy flavors than men. Women are also more likely to enjoy complex wines, preferring wines with low tannins and more subtle acidity (Fuhrman, Reference Fuhrman2001).

In recent years, the wine industry has seen a significant increase in the number of women occupying various positions, particularly winemakers and sommeliers (Gilbert and Gilbert, Reference Gilbert and Gilbert2012; Almila, Reference Almila, Inglis and Almila2019). The growing importance of women in the industry may influence the production and marketing of wines, which could lead to an increase in the availability of wines with feminine characteristics. Certain aromas are commonly associated with femininity, and gender metaphors are common in wine vocabulary (Negro, Reference Negro2012). For example, the presence of floral notes such as rose or violet, or adjectives such as silky or voluptuous, could contribute to the perception of wine as feminine. On this basis, we can expect wines to become increasingly feminine and make the following proposition: the use of feminine wine descriptors increases over time (Proposition 1).

b. Feminine wines, critics’ scores, and aging potential

Gilbert and Gilbert (Reference Gilbert and Gilbert2012) show that female winemakers are more highly regarded by experts than male winemakers in proportion to their presence in the field, particularly in California. In such a context, we can examine if wine talk or wine discourse, defined as the language employed by critics, has also developed. Wine talk is distinct from the “wine language” employed by academics in the industry (Inglis, Reference Inglis, Stanley and Kehrein2020). Indeed, descriptors with gradable and evaluative concepts (Lehrer, Reference Lehrer1975, Reference Lehrer2009), metaphors, and personification are used liberally to convey emotions associated with wine consumption (Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson, Reference Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson2013). As Vanini et al. (Reference Vannini, Ahluwalia-Lopez, Waskul and Gottschalk2010, p. 391) explain:

“Metaphors provide a colorful, convenient, and widely accepted tool to elaborate on sensuous qualities of wine and experiences of taste.”

One of these metaphors is the description of wines as either “feminine” or “masculine” (Lehrer, Reference Lehrer1975, Reference Lehrer1978, Reference Lehrer2009; Negro, Reference Negro2012). If wine itself is a gender-neutral commodity, the semantic relations of certain words used together can suggest a particular gender. As described by Lehrer (Reference Lehrer2009, p. 32):

“Feminine is associated with soft, smooth, light, round, perfumed, possibly sweet, and these words do have definite meanings in the wine domain. Hence, a feminine wine will be understood as one having those properties. A masculine wine is big and perhaps rough.”

Previous research has shown that male and female judges assign the same scores to the same wines (Bodington, Reference Bodington2017; Bodington and Malfeito-Ferreira, Reference Bodington and Malfeito-Ferreira2018), but the relationship between wine quality and its gendered description is uncertain. Some authors have argued that gendered wine descriptors are used to transfer societal gender distinctions to the wine sector, with lighter “feminine” wines rated as inferior and less interesting than larger “masculine” wines (Matasar, Reference Matasar2006; Inglis, Reference Inglis, Stanley and Kehrein2020). Pogacar et al. (Reference Pogacar, Angle, Lowrey, Shrum and Kardes2021) assert that feminine names are positively associated with warmth and could provide a branding advantage and increased choice. Femininity is associated with hedonic products that create sensory, experiential, and pleasurable benefits (Schnurr, Reference Schnurr2018). Given that taste-related words cannot be independent of a hedonistic consideration and that experts recognize the hedonistic value of wine (Brochet and Dubourdieu, Reference Brochet and Dubourdieu2001), we make the following propositions:

- The more feminine the wines, the higher their tasting score (Proposition 2);

- The more masculine the wines, the higher their aging potential (Proposition 3).

c. The price of feminine wines

Assessing wine quality is as much a sensory as a cognitive process for experts, where numerous contextual and environmental factors can influence the perception and evaluation of wine (Charters and Pettigrew, Reference Charters and Pettigrew2007; Spence, Reference Spence2020). Research suggests that expert evaluations contain little private information. Most of the price of fine wine can be explained by reference to public information, such as weather data (Ashenfelter, Ashmore, and Lalonde, Reference Ashenfelter, Ashmore and Lalonde1995; Ashenfelter and Jones, Reference Ashenfelter and Jones2013).

However, for some influential experts, their assessment of wine ends up with a score that can have a direct impact on prices (Ali, Lecocq, and Visser, Reference Ali, Lecocq and Visser2008). Previous research has investigated how wine reviews predict quality (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Barth, Katumullage and Cao2022) and how tasting notes relate to price. Tasting note length is positively associated with price (Ramirez, Reference Ramirez2010). Although previous research has unequivocally dismissed wine descriptors as “bullshit” (Quandt, Reference Quandt2007), the content of the tasting notes is also important. Some of these are valued by consumers (Capehart, Reference Capehart2021a), with different themes depending on wine region and varietal (McCannon, Reference McCannon2020). Capehart (Reference Capehart2021b) shows that some “expensive” and “cheap” words are more likely to be used for high- and low-priced wines, respectively; for example, specific or elite words such as truffle, elegant, and vintage are associated with expensive wines, whereas general or accessible words such as tasty, pleasing, or harvest are associated with cheap wines. Thus, and based on the positive outcomes of feminine elements in hedonic consumption, gendered descriptors may also be of some value to consumers, and we make the following proposition: the more feminine the wine description, the higher the price (Proposition 4).

III. Method and data

To answer our questions, we used an extensive database of Robert Parker Jr.’s tasting notes and ratings on vintages from 1994 to 2013, for a total of 1,404 observations. We use Bordeaux data to make the analyses perfectly comparable and only consider en primeur ratings and prices. Focusing on a single expert and a single wine region may seem restrictive. However, it is worth noting that (i) Robert Parker Jr. is the best known and most influential taster in the world (Masset, Weisskopf, and Cossutta, Reference Masset, Weisskopf and Cossutta2015), (ii) he is known to have stable preferences, (iii) his scores are accompanied by tasting notes and a suggested drinking window, and (iv) Bordeaux wines represent more than 50% of the global fine wine market (see Liv-ex.com).

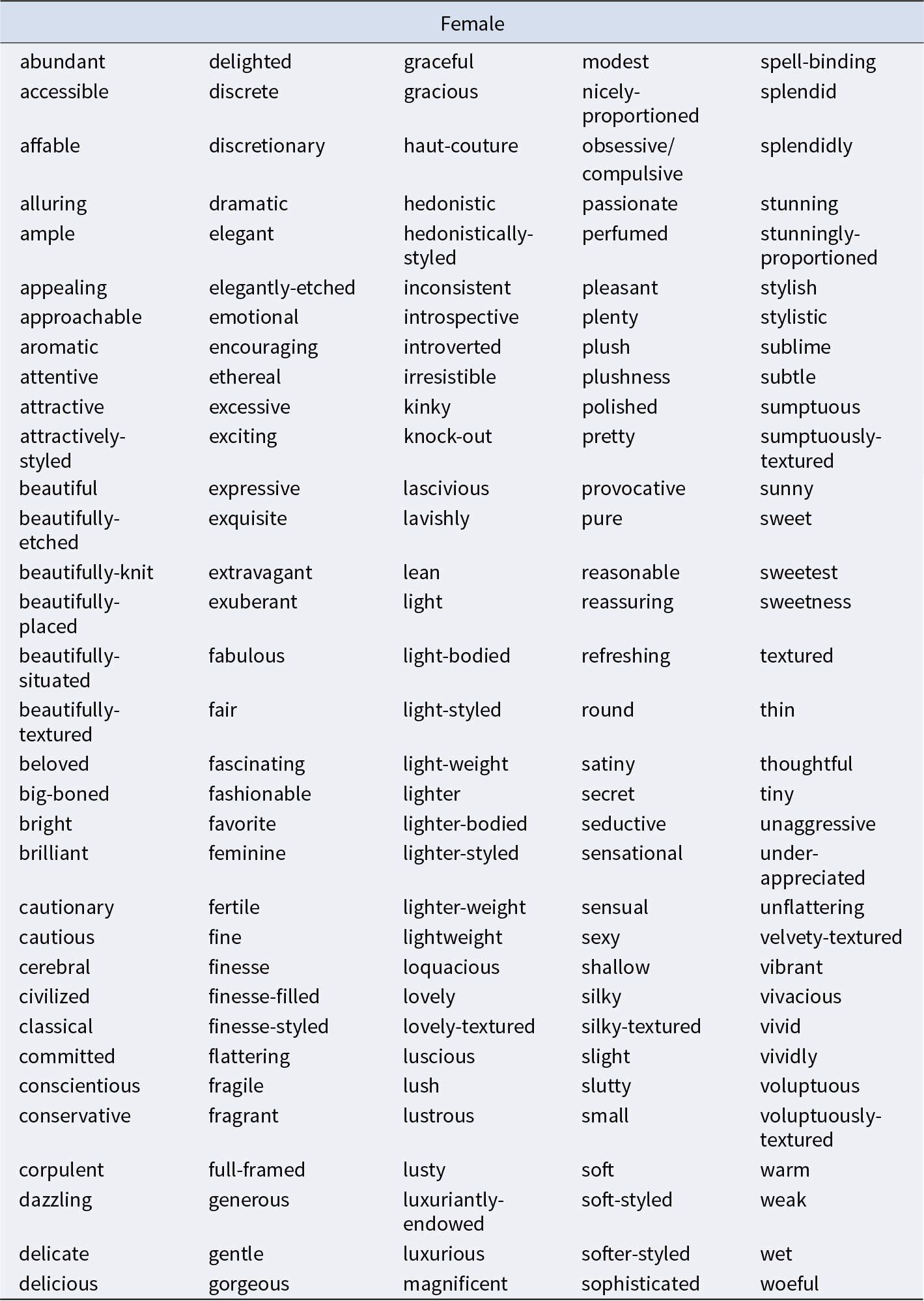

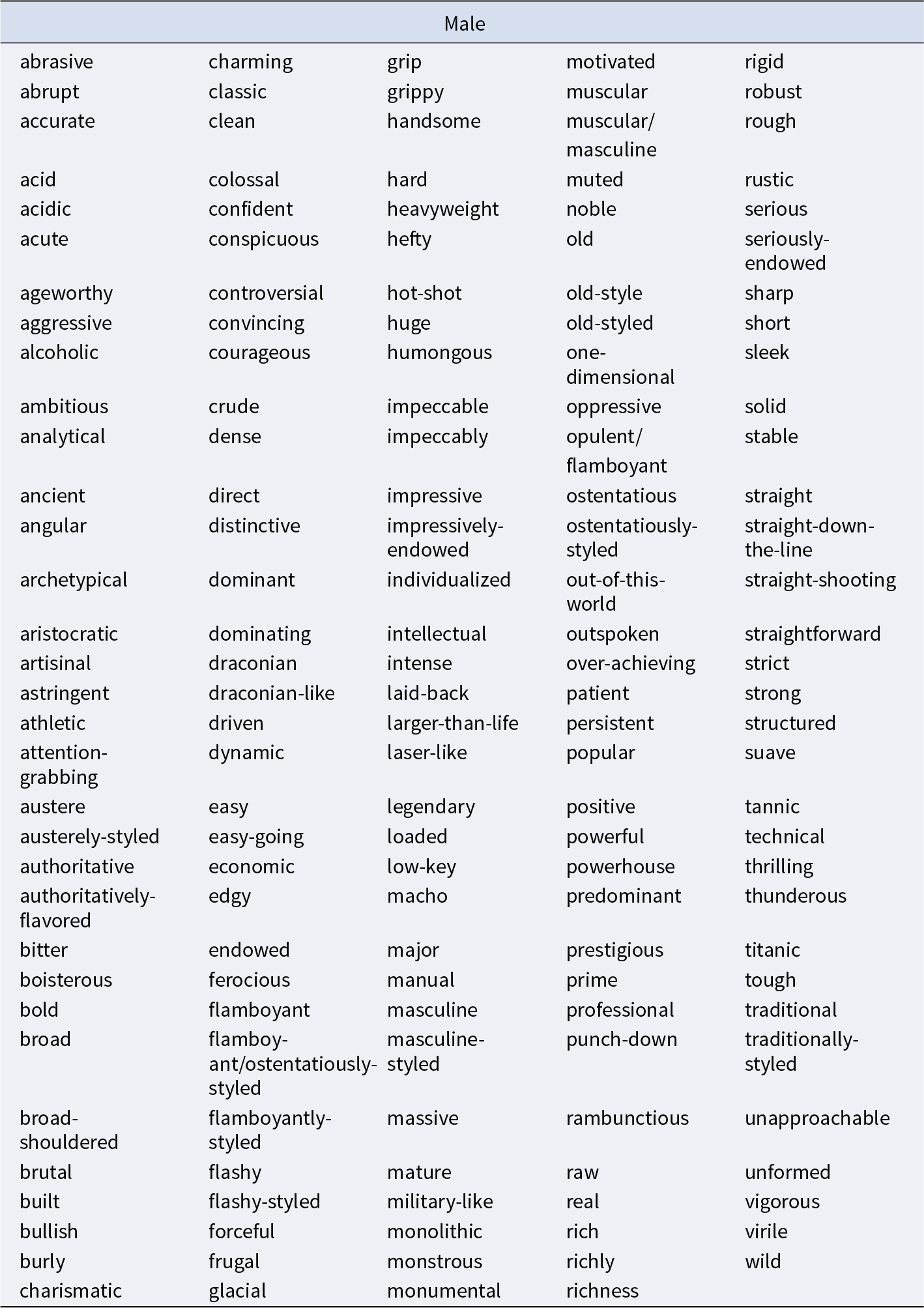

To determine the level of femininity of the wines in our sample, we created an indicator based on the gender of the descriptors used in the tasting notes. We extracted all individual adjectives and words. This gave us 1,183 wine descriptors in our sample, including 194 references to wine aromas (e.g., blackcurrant, floral). Each of these descriptors was then evaluated by three experts (specializing in linguistics, communication and culture, and psychology, respectively) to determine the gender with which it could traditionally be associated and classified as either masculine, neutral, or feminine. In case of disagreement, the gender was discussed within the group. If no agreement was reached, the descriptor was considered gender-neutral and not gender-related (e.g., questionable, insipid). We identified 329 gender-related descriptors (GRDs), well-balanced between masculine (e.g., muscular, solid) and feminine (e.g., elegant, soft) ones (164 and 165, respectively). The list can be found in Appendix 1. The most frequently encountered gender-related adjectives are the following: sweet (present in 45% of the tasting notes), fine (26%), pure (18%), elegant (17%), and light (16%) for female-related adjectives; rich (31%), acidic (28%), dense (25%), impressive (16%), and powerful (13%) for male-related adjectives.Footnote 1

On this basis, we calculated a ratio that measures the proportion of female-related descriptors (FRD) out of all the GRD used in each tasting note: the higher the score, the greater the degree of feminine descriptors. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on both the independent (gender-related adjectives, upper panel) and the dependent (rating, aging potential, and price, lower panel) variables. Overall, the number of adjectives associated with the feminine and masculine genders is very close. The proportion of feminine terms is slightly higher, as some wines have a particularly large number of descriptors associated with this gender. The average rating is close to 92 points, with a standard deviation of 3.55. Some wines achieve near-perfect scores (99.5 points), while the worst performers score below 80 points. Aging potential is highly variable, and some wines were considered ready to drink when the tasting note was written (the minimum age being equal to 0). Prices are quite variable, reflecting significant château and vintage effects. Indeed, some châteaux and vintages sell for much higher prices. It will be important to take this into account in the empirical analysis by including fixed effects in the regression models.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Château Trotanoy 1994 is the wine with the least feminine descriptors (or the lowest FRD score), with 29% FRD in the tasting note, while Domaine de Chevalier 2000 is the wine described as the most feminine one, with 70% FRD. Overall, the average proportion of feminine descriptors within a tasting note is 30%, with a minimum of 16% for vintage 2007 and a maximum of 38% for vintage 2000 (see Figure 1). The trend over the vintages is slightly decreasing, which contradicts Proposition 1.

Figure 1. Percentage of feminine descriptors by vintage.

IV. Empirical analysis

We run a series of regressions to explain (1) Robert Parker’s rating, (2) aging potential measured at the beginning and end of the drinking window, and (3) en primeur release price. For each of these three models, we estimate a series of regressions with château and vintage fixed effects (Model I), the percentage of female-related descriptors (FRD) (Model II), the number of gender-related descriptors (GRD) (Model III), and the length of the tasting note (TN) (Model IV) as explanatory variables. In addition, the age and price equations include Parker’s rating (Model V). Aging and price equations are estimated using a double-log specification. Estimation results are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2. Rating equation—estimation results

Note:

* , **, and *** denote significance at the 90%, 95%, and 99% levels, respectively.

Table 3. Age equations—estimation results

Note:

* , **, and *** denote significance at the 90%, 95%, and 99% levels, respectively.

Table 4. Price equation—estimation results

Note:

* , **, and *** denote significance at the 90%, 95%, and 99% levels, respectively.

FRD does not play a role in the evaluation (Table 2), which contradicts Proposition 2. The total number of gender-related descriptors appears to be significant (III), but this effect vanishes when controlling for the length of the tasting note (IV).

In Table 3, FRD is highly significant in each specification. It seems that wines described as feminine enter their drinking window earlier than wines described as masculine, as the coefficient associated with FRD is negative when considering age at the beginning of the drinking window. This means that wines described in a feminine way can be enjoyed much younger than those described in a masculine way. These wines also tend to have a more limited aging potential, as they are also associated with a negative coefficient when considering age at the end of the drinking window. These results are in line with Proposition 3. This result holds even when we control for the relationship between score and aging potential.

In Table 4, we obtain very high R-squared values thanks to the château and vintage fixed effects. Previous empirical literature suggests that reputation and vintage are the most important determinants of Bordeaux wine prices (see, e.g., Masset and Weisskopf, Reference Masset and Weisskopf2022). Ratings appear to play a limited but significant role. Neither the FRD nor the number of GRD are significant, suggesting that wines described as feminine sell for essentially the same price as wines described as being more “masculine.” Proposition 4 is not supported.

V. Concluding remarks

Given the increasing gender diversity in the wine industry and the extensive use of gendered metaphors and descriptors in tasting notes, we analyze the ways in which wine descriptions are gendered and how this relates to quality and price. Interestingly, despite the growing role of women in the wine industry, the description of wine has not become more feminine. Moreover, the gendered description of a wine appears to impact neither its ratings nor its price. However, wines described as more feminine both enter their drinking window and start to decline at a younger age than those described as more masculine. This finding is consistent with the premise that the attributes described are more commonly associated with hedonism, such as quick consumption. In contrast, masculine descriptors are more readily associated with the wine’s aging potential (Schnurr, Reference Schnurr2018). So, while a feminine description of a wine may not significantly impact its price or rating, it may nevertheless have repercussions on consumer behavior.

Our results are based on data from only one expert, who is known to prefer bold wines. In addition, our dataset covers a period when consumers also tended to prefer bold wines. Further research could examine the tasting notes of multiple judges and analyze whether wine descriptors vary according to their gender. The valence of gender-related descriptors could also be considered in the analysis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for his/her insightful comments and suggestions. The article has also benefited from discussions with AAWE 2023 conference participants. The usual disclaimers apply.

Appendix: List of gender-related descriptors