The study of failure is undergoing a critical turn. Integrative work is now moving beyond long-standing questions. What constitutes failure? Can it be avoided? And how is it best understood — from a realist position for which objective criteria exist, or a social constructivist one that reflects subjective interpretations? Case studies are also expanding to include new areas of investigation: redefinitions of failure as success, failure as a mode of resistance to neoliberalism, failure modelling to anticipate scenarios of future breakdown in an era of accelerating climate change, and so on.Footnote 1 This article draws upon this critical turn to reimagine failure in a context where failure is omnipresent — the world of development policy. The literature on this topic is vast, with much of it traditionally adopting the view that such policy either is a technocratic tool for rational problem-solving or a political one for extending bureaucratic power. Of course, the dichotomy is a false one.Footnote 2 Neither position is mutually exclusive of the other and other possibilities exist, as this case study shows.Footnote 3 Historically, the study concerns the Communist Party's efforts to violently transform property relations in northern Vietnam (1952–1956). Analytically, it takes up the methodological question of how to engage with the source base — dozens of anonymous field reports — without reducing our understanding of what allegedly occurred to the dichotomy of success versus failure. With that in mind, this article examines how the nearly always anonymous report authors rhetorically communicated failure, both in imaginative and material terms, via different ‘storytelling devices’.

Oliver Kessler, writing about neoliberal forms of governmentality, identifies three framings related to it: ‘failure as empirical irregularity, failure as miscommunication, and failure as a mode of organization’.Footnote 4 His focus is on how these explanations identify the purported causes of these failures but in a manner that leaves the structural logics and values of neoliberalism intact. Failure, from this perspective, is a type of success, as it perpetuates, if not strengthens, neoliberalism in its varied forms.

My focus is similar, despite unfolding in a radically different context — the final years of the First Indochina War (1946–1954) followed by the initial efforts to institutionalise Party-state rule across the newly independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The efforts to implement this goal relied heavily upon the concept of ‘emulation’ (thi đua), a model for change that remained in use for decades thereafter in both the public and private spheres.Footnote 5 In practice, emulation required people to reproduce desired forms of thought and action. The theory being that they would, through repetition, become ‘exemplary’ (gương mẫu) and thus models for others to emulate, driving the process forward in cumulative fashion until the desired goal was attained.Footnote 6 But the examination of the ‘storytelling devices’ in the reports reveals that emulation of the mobilisation model did not occur, at least not in the way policy documents prescribed. Yet, the model remained fundamentally unchanged for the duration of the multi-year campaign, raising the question as to whether the absence of iterative policy learning was deliberate and/or due to something else. This question informs but does not determine the analysis here of failure (re-)framed.

The stated purpose of the campaign, which utilised Maoist models of class struggle, was to end ‘feudal’ and ‘capitalist’ exploitation of poor and landless peasants with the expected outcome being greater food security that would, in turn, fuel rapid agricultural development. The campaign unfolded in a series of ‘waves’ that began in November 1952 and ended in October 1956, with eight rounds of land rent reductions and six more of the land reforms proper. The campaign affected more than 3,300 communes, with some undergoing only one round of class struggle while others experienced multiple ones.Footnote 7 The word ‘error’ (sai lầm) frequently appears in accounts of the period, including official ones. (The Rectification of Errors, the Party-state's multi-year effort to restore order follow the campaign is a case in point.) An ‘error’ was a capacious concept that covered not only deviations from policy, but also things such as the tens of thousands of incidents of wrongful imprisonment, torture, and execution.Footnote 8 Not surprisingly, the frequency and severity of these reported ‘errors’ increased dramatically following the end of the First Indochina War, as the number of communes undergoing the campaign exploded, doubling approximately twice from ‘waves’ three to four and then again from four to five, which affected 466, 859, and 1,720 communes, respectively.Footnote 9

But why use the concept of failure rather than ‘error’? Broadly defined, failure means the fact of someone or something not succeeding. The concept of failure thus includes not only the ‘errors’ the mobilisation cadres identified, but also less serious instances where desired end(s) were not met or fell short, what the reports described as ‘mistakes’, ‘limitations’, ‘shortcomings’, and so on. The goal here is not to definitively prove whether the campaign as a whole or specific aspects of it failed either programmatically or ideologically. Rather, the goal is to understand how the mobilisation cadres themselves framed failure in their ‘recapitulation’ (tổng kết) reports, which focused on what they called the ‘experiential lessons learned’ during campaign implementation.

The narration of failures appears most clearly with regard to the ‘reorganisation’ (chỉnh đốn) of rural Party cells, the final step of the five-step Maoist model and the focus of this case study. Reorganisation consisted of three main tasks.Footnote 10 First, the expulsion and punishment of those existing members categorised as belonging to groups targeted for class struggle. Second, the re-education of those with somewhat problematic but still acceptable backgrounds and behaviour. Third, the promotion of some radicalised peasants, then called ‘backbone elements’, into positions of leadership despite having little to no relevant knowledge, skills and, quite often, the ability to read or write. Structured activities to help build solidarity between the remaining ‘old’ and the ‘new’ cadres followed, with the average rural cell then consisting of 10 to 20 members. The point of these activities had a larger purpose as well. Specifically, it was to strengthen the cell's legitimacy in the eyes of the commune's inhabitants and, by extension, deepen Party and state control over local affairs, especially in recently liberated areas where it previously exercised little or none.Footnote 11

Precisely who authored the reports is rarely known. The trajectories of these reports are still poorly understood as well. In vertical terms, the reports made their way up the administrative chain-of-command with the ultimate readership likely being members of the Central Land Reform Committee. In horizontal terms, the Central Land Reform Committee periodically compiled large numbers of the ‘recapitulation’ reports into published volumes, presumably for other cadres tasked with implementing the campaign to study. (The longest one obtained was nearly 450 pages.) The publisher, the Central Land Reform Committee, did not organise the contents in any systematic fashion beyond chronology by ‘wave’, however. Neither is there any attempt to synthesise the separate findings into patterns of ‘lessons learned’.

Despite such limitations, the ‘recapitulation’ reports warrant more than a passing footnote in the historiography of the mobilisation campaign. Indeed, the first official scholarly history of the mobilisation campaign, published by the Institute of Economics in 1968, noted that the ‘reorganisation’ process was, when the Party leadership abruptly halted the campaign in 1956, the first of three ‘errors’ most in need of urgent ‘rectification’.Footnote 12 Yet, this part of the process has received almost no attention. To address this oversight, it is important to remember that ‘reforms themselves are cultural’, as Colin Hoag and Matthew Hull point out. ‘They entail norms, ways of speaking and interpreting, and a politics.’Footnote 13 Close attention to these cultural aspects of the reports through their ‘storytelling devices’ offers the means to deepen our understanding of failure, both as the report authors framed them and, by extension, how we might re-frame them from the vantage point of the present.

This article consists of four main sections, each focusing on how different ‘storytelling devices’ narrate cadre assessments of failure and the interpretive challenges they raise when subject to analysis. The first section provides further details on the historiography of this period and how the ‘recapitulation’ reports can be situated within it. The second section directs attention on the initial task of ‘reorganisation’, the assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the extant Party cell at the individual level as well as collectively. The third section details the next task, the ‘purification’ of the partially ‘reorganised’ cell via different forms of disciplinary action. The fourth section examines the final task, the techniques the mobilisation teams used to foster ‘unity’ between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ cell members to consolidate the ‘reorganised’ cell ideologically as well as socially. The conclusion returns to the question of what the ‘recapitulation’ reports offer, theoretically and methodologically, towards more fully understanding this still highly controversial mobilisation campaign, and studies of failure more broadly.

Context

A consensus now exists that the Communist Party's senior leadership, including Hồ Chí Minh, embraced the Maoist model for waging class warfare from the very start with full knowledge of the violent chaos it would unleash across the countryside. Indeed, in the most definitive work to date, Mass mobilization in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 1945–1960, Alec Holcombe argues that the key purpose of the campaign was from its inception narrowly self-interested. The central goal, he states, was ‘to use the landlord class as a scapegoat for six years of unsuccessful economic policies and other unpleasant aspects of rural life in northern Vietnam's liberated zones’.Footnote 14 But two additional factors mattered tremendously as well. Commune residents frequently manipulated the process to retain power and wealth, settle personal scores, obtain coveted property, become cadres themselves, and so on.Footnote 15 Cadres tasked with carrying out the campaign also received little training beyond ‘study sessions’ beforehand. The sessions, which were largely ideological rather than practical in nature, meant that mobilisation cadres were methodologically ill-prepared to implement the campaign properly, even where they acted in good faith.Footnote 16 It is possible to argue, as Holcombe does, that the campaign's architects were well aware that these latter two factors would reinforce the scapegoating of ‘class enemies’ as a means to deflect criticism away from the Party. From this perspective, the violent chaos was a success. But it was also a failure, when contextualised more broadly. The same chaos significantly threatened the newly independent regime's stability, and it also hindered post-campaign efforts to promote agriculture productivity via gradual collectivisation.Footnote 17

Interestingly, report contents do not exhibit obvious signs of a scapegoating strategy. It is difficult to believe the report authors were not aware of the results desired, however. Memories of the 1951–1952 Maoist-style ‘Thought Reform’ campaign, which purged many thousands of Party members, were still fresh.Footnote 18 Fresher still was a May 1953 Politburo directive, issued just prior to ‘wave’ one of the land reforms. It declared that landlords constituted at least five per cent of the total population, irrespective of realities on the ground, meaning there was an official quota in effect.Footnote 19 Yet, the report contents were usually measured in tone, empirically oriented, and largely devoid of political slogans as this representative example illustrates:

During the land rent reduction campaign, why is it that [we have] not yet replaced the landlords in the [Party] cell with the poorest and most wretched of peasants? The causes:

1. [We] have yet to correctly assess the situation of those rural cell members who lack clean [personal] histories. [We] have yet to sufficiently perceive the landlord situation that has controlled the cell for a long time. Resultingly, there are cadres who blindly believe in the bad cadres.

2. With regard to the bad cadres that [we] discovered, there are some cadres who regret [their actions] because they believe in labouring [as peasants], have ability, are cultured, etc. Those [cadres] should not be disciplined.

3. [We] have used the Party's methods to carry out reorganisation, but [we] did not learn to rely upon the masses and did not listen to their opinions. Consequently, we did not clearly distinguish these bad Party members from good ones, therefore, [we] lacked the means to purge these Party [bad] members perfectly.Footnote 20

References to Marx, Lenin, Mao, or socialism are rare as well. Nevertheless, the language in the reports makes it clear that the authors had undergone significant ideological training judging by the fluency with which they expressed themselves in such terminology. Such jargon can be off-putting, and it likely was at the time to ordinary people. But it is crucial to attend to how they deploy it to frame failure because it also conveys the conceptual life-worlds these mobilisation cadres inhabited at the time.Footnote 21

The reports are striking in many other respects as well. They vary considerably in length, with the average length of those examined being approximately 15 typewritten pages, and the longest reaching 51 pages. Considerable differences in narrative detail and analytical sophistication also exist, further indicating that there was no official template to guide their authors. The lack of such a template meant that there were no apparent limitations on the amount and type of information sought. As a result, the reports contain a diverse array of information ranging from micro- to macro-level issues. Brief profiles of the landlords targeted sometimes appear.Footnote 22 So, too, do the commentaries on the poor and landless peasants recruited, periodically including dialogue-style excerpts of their indoctrination.Footnote 23 Notably, the affective dimension, in terms of the language of peasant victimisation, is almost entirely lacking, however. Quotes taken from the denunciation of landlords do not appear, for example. Neither do details on trial outcomes. Also missing are references to other important concurrent events, such as the 1953 famine, then unfolding across large swathes of the northern countryside. The authors, except in very few cases, do not cite other pertinent policy documents either, while the important 1953 Land Reform Law is not mentioned at all.

These variations aside, all of the reports shared two basic components. The opening section detailed what the mobilisation team accomplished. In nearly all cases, the results took the form of statistics, such as the types of ‘class enemies’ identified, the amount of land and private property redistributed, the number of previously marginalised peasants promoted into positions of administrative authority, and so on. The accuracy of these figures, later revised, sometimes significantly, should not be dismissed as merely being politically expedient claims crafted to please their superiors. The campaign did, in fact, produce positive outcomes and changed the lives of millions for the better. But, as the next section of the reports made clear, the achievements did not come without costs. These costs, which generally received far more attention and narrative space in the reports than did the achievements, detailed what the typically anonymous authors framed as failures.

The lifecycle of the reports is very difficult to reconstruct as well. Most obviously, the reports do not include dates, only subtitles that indicate that a report concerns events that occurred during a specific ‘wave’. Consequently, it is not possible to accurately determine when the report was written, much less when it was submitted to the team's superiors to be read. The timeliness of the reports with regard to policymaker decision-making schedules is thus unknown. Additionally, internal government documents customarily list which branches of the bureaucracy are to receive copies, making the institutional audience for them clear in the process. The ‘recapitulation’ reports do not include such details either, so identifying the likely trajectories of these reports must rely upon conjecture.

In several instances, the Central Land Reform Committee compiled dozens of separate reports, as well as policies that did not always appear in the Complete collection of Party documents, and then published them in the form of lengthy volumes.Footnote 24 The 1955 Experiences of reorganisation of rural Party cells during the land rent reductions and the land reforms, is one such example. The page numbers of other ‘recapitulation’ reports indicate that they were once part of a published volume but are no longer so. Other reports have no page numbers at all and may (or may not) have circulated as standalone ones. These uncertainties reflect the source of the materials, used-book dealers in Hanoi, who, when asked, either could not or would not explain how they themselves acquired Xerox copies of the original typewritten reports.

These limitations aside, the reports are nonetheless illuminating. To demonstrate how, this case study draws upon 89 primary source documents. Thirty-four of the reports focus on different aspects of the ‘reorganisation’ of rural Party cells; 43 on issues specific to the land rent reductions and land reforms, and 15 more on these efforts in Thái Nguyên Province, the geographic location featured.

Several features made Thái Nguyên an ideal, though not the sole, site for the start of the mass mobilisation campaign. Much of Thái Nguyên was in a liberated area during the First Indochina War, the population was portrayed in official documents as being ‘patriotic’, and the province contained numerous genuine ‘landlords’ that collectively owned nearly 20 per cent of all the arable land according to assessments.Footnote 25 Communes in Thái Nguyên served as sites of experimentation and, in theory, the implementation of ‘experiential lessons learned’ over several years for these reasons.Footnote 26 Interestingly, ‘recapitulation’ reports that mobilisation teams in other provinces submitted (e.g., Phú Thọ, Tuyên Quang, Yên Bái, Bắc Giang, and Hà Tĩnh) over these early ‘waves’ exhibit strong similarities. These similarities indicate that the Thái Nguyên reports were not atypical. But Thái Nguyên Province was different from the other provincial reports in one important respect. Thái Nguyên was the only province to undergo successive ‘waves’ of both the land rent reductions and land reforms, meaning there was a degree of continuity and, in theory, accrued knowledge regarding the ‘experiential lessons learned’ not necessarily generated elsewhere. Several direct and indirect references to Thái Nguyên in central-level policy documents promulgated during this initial period (late-1952 to late-1954) further suggest that the architects of the campaign did in fact regard the province as a useful case-study as a result.Footnote 27

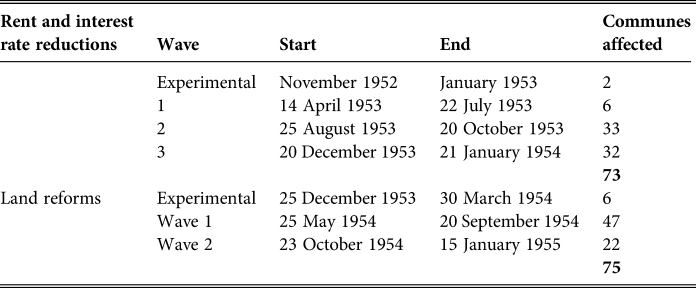

Table 1. Thái Nguyên mass mobilisation timeline

Source: Nguyễn Duy Tiến, ‘Qúa trình giải quyết vấn đề ruộng đất ở Thái Nguyên từ sau cách mạng tháng 8 năm 1945 đến hết cải cách ruộng đất’ [Resolving land issues in Thai Nguyen from the August 1945 Revolution through the end of the land reforms] (Ph.D. diss., Institute of History, Hanoi, 2000), pp. 6, 17–18, 74, 82, 88.

Cell assessment

A circular, issued in mid-March of 1953, shortly before the first wave of land rent reductions began in Thái Nguyên, summarised the central goal of the ‘reorganisation’ of rural Party cells. The main purpose of the process was to ensure that the new cell would be ‘pure’, the relationship between its members and non-members ‘tight’, and the political and economic interests of peasants ‘regained’.Footnote 28 The point of departure for achieving the second two goals was thus the first: purification. But the circular did not specify how the teams should actually ‘purify’ a cell. The situation changed in mid-November when a new instruction provided a typology for teams to use. The typology, which remained substantively unchanged over the course of the entire multi-year campaign, called on the teams to first assess a cell member's ‘class fraction’, ‘point of view’, and ‘ideology’ to determine whether they should be individually categorised as ‘good’, ‘mixed’, or ‘bad’.Footnote 29 People assigned to the first category were to be retained, the second ‘reformed’ if possible, and the third expelled. (By default, landlords and rich peasants fell into the third category, though they were not always expelled in practice.Footnote 30) Determinations regarding the members categorised as ‘mixed’ were not always easy to make, however.

A person's ‘history’, that is, one's track record of support for the revolutionary cause, was an indicator that could sway the team's decision either way. So, too, was the nebulous concept of liên quan, which in this context meant ‘to have connections’ with a ‘class enemy’. The nature of the connection (both frequency and type) did not receive policy clarification beyond specifying blood relatives and ‘lackeys’ as givens. Due this partial silence, it is not surprising the ‘recapitulation’ reports frequently noted the teams employed the concept too broadly and ‘disciplined’ otherwise acceptable cell members, who were then expelled.Footnote 31 One Thái Nguyên report, to offer a representative example, bluntly acknowledged that the team's ‘documentation was always vague, fragmentary, [as well as] insufficiently investigated and synthesised, so there were incorrect conclusions’.Footnote 32 The numbers were telling in this regard.

Numbers may be ‘gestural’ in nature, meaning their primary importance may lie in their metaphorical or rhetorical use.Footnote 33 In the context of the campaign, the numbers regarding ‘class enemies’ included in the reports represented the scale of the threat and thus the perceived urgency of the need to eradicate it. Determining the scale of the threat by reading the reports is challenging, however. Most of the reports have a narrow geographic focus, such as a single commune out of the several targeted. In addition, these reports break down the cell's membership by ‘class fraction’, but typically only in percentage terms, meaning the totals out of which these figures were determined was missing.

A report on the land rent reductions in Thái Nguyên, for example, stated that the number of landlords in Party cells relative to the total number of landlords in the province was nearly 50 per cent, with some communes reaching between 70–80 per cent.Footnote 34 Another report, this one on the land reforms experimental ‘wave’, found that 63 per cent of the Party cells in the six communes targeted were ‘bad’ as a result of the number of landlords and rich peasants in them.Footnote 35 Land reform ‘wave’ one findings were similarly alarming, if accurate. The teams identified 76 landlords, 129 rich peasants, and 44 ‘other exploiters’ within the 47 Party cells examined.Footnote 36 According to the report's author, 32.94 per cent of these cells needed to be completely disbanded and created anew; 52.24 per cent partially reorganised following a period of ‘re-education’ for those not expelled; and a mere 14.38 per cent requiring no significant changes in member composition.Footnote 37

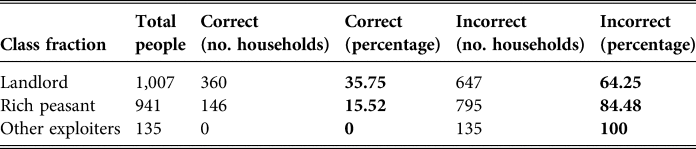

These statistics should be treated with caution, however. Provincial data later revealed that the totals were often wrong by a significant margin (Table 2). A re-assessment, conducted during the post-land reform ‘Rectification of Errors’ campaign found that the Thái Nguyên teams had wrongly categorised 30.79 per cent of the cell members. Out of total of 3,488 people, 1,074 were incorrectly assigned as being either ‘exploiters’ or having ‘connections’ with them.Footnote 38 The ideological ‘error’ of ‘Leftism’, defined here as excessive revolutionary zeal when carrying out policies, was even worse when all ‘class enemies’ in the 75 communes targeted are included.

Table 2. Provincial data on ‘errors’ by ‘class fraction’

Source: Nguyễn Duy Tiến (2000), p. 128.

Unfortunately, the provincial statistics do not indicate what percentage of the totals included Party cell members, but the figures certainly suggest that ‘Leftism’ was a problem from the very beginning of the campaign rather than predominantly towards its end. Nor do the data provide details on what happened to the members following the assignment of the incorrect ‘class fraction’. The question of punishment, which the reports described in terms of ‘disciplinary’ action, provides possible clues.

Cell purification

The ultimate goal of ‘reorganisation’, policy documents regularly stated, was for each cell to become the ‘seed for political leadership in the countryside’. To achieve this goal, the cell's purification was required. The first step, as previously mentioned, required the teams to determine which members were ‘good’, ‘mixed’ (sometimes referred to as ‘weak’) and ‘bad’. Teams used these categories to assess each cell member individually and then tabulated the respective totals to classify the cell as a whole. To make these assessments, the teams relied upon a range of indicators, though they were rarely concretely defined. As the reports make clear, the lack of specificity was problematic because the question of who chose what indicators to emphasise was an ideological decision in addition to a technical one. In the highly charged context of class struggle, for example, the indicators were almost exclusively qualitative and hence subjective in nature. Thus, their utilisation tended to ‘produce the phenomenon that they claimed to measure’.Footnote 39 Their utilisation did so because the five-step model greatly oversimplified complex local realities, which ensured that the teams’ interpretation of the indicators used would largely conform with the ideological abstractions that policymakers prescribed.

‘Good’ cell members, policy after policy explained, worked ‘diligently’, were Party ‘loyalists’, enjoyed the people's ‘trust’, had a ‘clean history’, and so on. Some of the indicators, such as a ‘clean history’, were at first glance simple to determine. Policy documents and ‘recapitulation’ reports variously specified prior service in the French military or administration, collaboration with the Japanese during the second World War, lack of support for the August 1945 Revolution and the subsequent independence struggle, the exploitation of others, and serious acts of violence as resulting in ‘unclean’ histories. People's past histories were rarely this straightforward, however. An individual might enthusiastically support the revolutionary struggle at one moment, but less so at another, and not at all at yet another. The question then was, how much overall support over time was needed to be considered sufficiently ‘clean’? Party policies were quiet on this issue.

The category of ‘bad’ Party cell members similarly appears uncomplicated at first reading. Source material distinguished five subgroups: ‘spies’, ‘traitors’, ‘reactionaries’, those that engage in ‘class exploitation’ (four sub-types listed), and those who have committed serious ‘crimes against the state and people’.Footnote 40 The boundaries distinguishing the subgroups were less distinct in reality than their descriptions would suggest, however. By definition, ‘traitors’ committed serious ‘crimes’ against the state. But, policies provided no advice on what, if any, implications such situations should have on the process, as not all of the indicators, such as acts of ‘class exploitation’, resulted in immediate expulsion. The silence in the reports extended to include what happened to these individuals once expelled. It is likely that many, if not most, experienced further punishment (e.g., loss of property, physical beatings, imprisonment, or execution) depending on the nature of their alleged ‘crimes’. Unfortunately, the Thái Nguyên ‘recapitulation’ reports limit their discussions to the breakdown of the ‘reorganised’ cell by the ‘class fraction’ of its members, leaving entirely open the question of the punitive consequences.

The category of ‘mixed’ cell members was more ambiguous. Such members had a good ‘class fraction’ (meaning middle or poor peasant) according to policies, but a ‘low level of class consciousness’. They were additionally described in reports as being ‘lazy’ in terms of their ‘work habits’ and lacked a strong desire ‘to improve’ themselves. In such cases, the teams and ‘good’ cell members were jointly to try to ‘rehabilitate’ them, but if that did not succeed, they too were to be expelled.Footnote 41 How to determine a person's level of ‘class consciousness’ went unexplained, however. Much like a person's ‘history’, the question became how much ‘consciousness’ was enough. Did awareness of the relevant policies suffice? Was it the ability to speak about the policies using the appropriate terminology? Or did sufficient ‘class consciousness’ require a demonstration of genuine understanding? If so, then in comparison with whom (ordinary people, ‘good’ cell members, or the mobilisation team themselves)?

Significant ambiguities also appear in the next step of purification: the ‘disciplining’ of all cell members, but especially the ‘mixed’ and ‘bad’ ones. Successive policies did not define what ‘discipline’ (xử trí) entailed. Instead, the Thái Nguyên source material makes scattered references to different activities, which are sometimes presented in sequence, but at other times not. When ordered logically, the process appears to have assumed the following sequence: ideological and policy study, ‘criticism and self-criticism’ sessions, the collective review of both tasks, followed by ‘cornering’ (i.e., targeting of) selected individuals, which may or may not have resulted in their demotion or expulsion.Footnote 42 On the one hand, the failure to define the various forms of ‘discipline’ may simply indicate the assumption that everyone already possessed a shared understanding of what it entailed. But, on the other hand, the policies also instructed the teams not to follow regular administrative procedures, suggesting that an alternative one was used.Footnote 43 No details on what the alternative procedures entailed were forthcoming, however.

Finally, the policies required the creation of a cell committee, under the teams’ supervision, to ‘discipline’ everyone in a ‘timely fashion’ and in a ‘resolute and prudent’ manner.Footnote 44 The wording — timely in the sense of prompt rather than rushed or delayed, and resolute and prudent in the sense of in a determined yet thoughtful fashion — can be read as a warning against the ideological ‘error’ of either excessive zeal (‘Leftism’) or insufficient discipline (‘Rightism). Three brief examples from Thái Nguyên reveal why these ideological ‘errors’ were frequently perhaps unavoidable.

The Government's Department of Organisation provided a lengthy critique of the ‘reorganisation’ process during the land rent reductions in Thái Nguyên. The teams, the authors opined, had ‘deviated’ from policy. In their view, they had ‘not yet grasped’ three essential issues: the ‘true’ class structure of the cells, how ‘class enemies’ had gained entry in the cells, come to dominate it, and undermine Party policies for within; and the extent to which the ‘reorganised’ cell remained ‘unclean’.Footnote 45 Consequently, the disciplinary process was ‘resolute but not prudent’ in some cases (a form of ‘Leftism’) and ‘prudent but not resolute’ (a form of ‘Rightism’).Footnote 46 A separate Thái Nguyên report on the first ‘wave’ of the land reforms additionally directed attention to the vague concept of ‘having connections with’. According to the report, a significant number of ‘class enemies’ had ‘slipped the knot’, and still occupied decision-making positions within the cell, and thus had yet to be properly ‘disciplined’. The result, the report conceded, was ‘Rightism’ due to the fact that many landlords and rich peasants remained.Footnote 47 By the same token, the report continued, cell members had sought to prevent people who had performed wage labour for rich peasants in the past from joining the cell on the grounds that they ‘had connections’ with ‘class enemies’, which was an example of ‘Leftism’.Footnote 48

In yet another report, the Government Department of Organisation provided a high-level summary of the ‘purification’ process in four provinces (Thái Nguyên, Bắc Giang, Phú Thọ, and Thanh Hóa) targeted for land reform ‘wave’ two. Teams ‘reorganised’ 268 cells between March 1953 and December 1954, out of which a total of 3,882 cell members were expelled; 3,333 of them were categorised as ‘bad’, and the remaining 549 as ‘mixed’. Consequently, only 2,908 ‘good’ members retained their positions in the cells.Footnote 49 The report does not break down the statistics on a province-by-province basis, unfortunately. Without access to provincial data that may have been gathered during the ‘Rectification of Errors’ campaign, it is impossible to assess the degree to which ‘Leftism’ and ‘Rightism’ contributed to these outcomes. But the collective figures, to the extent accurate, do reveal that the number of ‘impure’ cell members significantly outnumbered ‘pure’ ones. Hence, the officially stated urgency to rapidly replace them with ‘new’ cadres, who may or may not have been vetted closely. (As one Thái Nguyên report noted, the ‘new’ ones were not always an improvement over the ‘old’ ones.Footnote 50) Not surprisingly, the next step, the consolidation of the cell, raises interpretive challenges of its own.

Cell consolidation

Information regarding the consolidation of ‘reorganised’ cells takes three main forms in the source material. The first was ‘reform though education’. The second entailed the ‘development of the new cadres’. The third focused on reconstruction via the election of new cell committee leaders. The order in which these tasks were to be carried out was not consistent, however, making it unclear as to whether there was a fixed sequence or some flexibility to carry out some aspects of each task concurrently. The issue of order aside, the goal remained the same: to create ‘unity’ between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ cadres so as to enable the ‘reorganised’ cell to function efficiently and effectively.

Surprisingly, Instruction no. 59, Circular no. 104, and Instruction no. 107, the three most important policy documents on ‘reorganisation’ issued during the first three land reform ‘waves’, offer only a modicum of information on these essential tasks. First, efforts to ‘reform through education’ recommended learning-by-doing rather than textual study, likely due to very low literacy rates in the countryside coupled with the abstract nature of the ideological concepts. Circular no. 104 stressed the need for ongoing ‘criticism and self-criticism’ sessions as the most suitable method for raising everyone's ‘ideological levels’.Footnote 51 While Instruction no. 107 recommended that the teams take this method further and identify ‘exemplary’ cell members for their colleagues to emulate.Footnote 52 The category of ‘exemplary’ received only general description, however. But, one report did provide what might be a representative list of the qualities needed: ‘to struggle resolutely, be persistent in one's viewpoint, not fear landlords’; ‘to be diligent and work selflessly on behalf of the masses’; and ‘to have a good relationship with the masses’.Footnote 53

Second, consolidation was not limited to the members’ education. It is also included the ‘development of new members’. The task, despite the name, actually concerned the need to ensure that previously poor and landless peasants now constituted the majority of the ‘reorganised’ cell members. From the point of view of policymakers, such a majority would ipso facto prevent the resurgence of ‘feudal’ and ‘capitalist’ ideas from subverting the cell from within. Subsequent studies proved the assumption wrong, however.Footnote 54

Third, local elections, organised around a choice of vetted candidates, provided the primary means to accomplish cell consolidation, if the amount of text devoted to this task in the policies is indicative. The process should be done ‘diligently and prudently’ and in a manner the ‘people would accept’, presumably to avoid dissension and to maintain Party legitimacy.Footnote 55 Not surprisingly, eligible cadres had to be poor or landless peasants, have a ‘clean history’, the ‘trust of the masses’, the capacity to safeguard the cell's ‘political and ideological leadership’, as well as preserve the Party's ‘line’ with some external district and provincial support.Footnote 56 The policies presented these requirements as if they were self-evident. Some of them arguably were, such as a person's past history, which could be crowd-sourced to verify. But some of the selection criteria were based upon expectations of future performance. The ability to defend the ‘Party's line’ in the face of possible resistance was one such example. Such predictions did not always prove to be accurate, however, and further admissions in the Thái Nguyên reports reveals why this presumption was deeply problematic.

A compilation of documents on the first land rent reduction ‘wave’ indicates that policies on the consolidation of the Party cells was already in place prior to the land reforms. But the majority of provincial and district cadres who guided the process in collaboration with the teams, had yet to ‘centralise the leadership task of strengthening the Party’, the documents conceded.Footnote 57 The Government Department of Organisation recommended that more attention to the ‘re-education’ of cell members would help resolve this problem. (The Vietnamese term can also be translated more literally as, ‘to rectify thought patterns’.) But once again, what the process of ‘re-education’ actually entailed went unspecified.Footnote 58 It perhaps went without explanation because political and ideological re-education was a central component of the broader purge of ‘impure’ Party members at the central and provincial levels of the administration between 1951 and 1953. Thus, it is likely that these cadres understood, to varying degrees, what the process required as a consequence.Footnote 59

But the Thái Nguyên reports confessed that the teams had carried out the disciplining process either ‘indiscriminately’, a form of ‘Leftism, or ‘timidly’, a type of ‘Rightism’. These outcomes respectively meant that the cells were either ‘purified’ to the point that they had too few experienced members or not enough so too many ‘impure’ members remained.Footnote 60 A separate Thái Nguyên ‘recapitulation’ report on the experimental land reform ‘wave’ offered a far more ambiguous assessment of the teams’ performance. On the one hand, the report's conclusion was that the ‘reorganisation’ process was very ‘arduous’, very ‘complicated’, and very ‘trying’, which is why teams must truly ‘comprehend’ the five-step model of mobilisation before beginning.Footnote 61 On the other hand, the advice, while sensible, does not admit that any ‘errors’ occurred in the six communes targeted during this ‘wave’. Subsequent ‘recapitulation’ reports suggest why this silence existed.

An inspection report on ‘wave’ one in Thái Nguyên, based on what occurred in a single commune, critiqued the ‘reorganised’ cell and, by extension, its own team members, for the ‘lack of results’ and ‘waste of money’. The cell had organised three separate conferences — one each for all other cadres, the ‘backbone’ elements, and local representatives of the mass organisations — to consolidate their respective member's leadership positions. The presenters, according to the report, did not ‘organise carefully, went on too long, debated in an unstructured manner, did not explain their points clearly, and, as a consequence, the participants’ understanding was ‘very mechanical’.Footnote 62

A different report on all six of the Thái Nguyên communes targeted acknowledged that the ‘re-education’ of all of the local Party members following ‘reorganisation’ was ‘weak’ and contributed to serious ‘doubts’ about the process.Footnote 63 This problem, one among the many the report admitted, reflected the inexperience of the teams. Their mobilisation efforts did not fully comply with ‘regulations’, and ‘failure’ was the result according to the author.Footnote 64

The final ‘recapitulation’ report, presented at a national conference, likely held in early 1955, provided a broader overview of the land rent reductions and land reform ‘waves’ carried out between March 1953 and December 1954. The Government's Department of Organisation report covers familiar ground with one notable exception. It does not single out Thái Nguyên by name. (Three other provinces underwent land reform ‘waves’ during this period.) Nevertheless, 73 communes in Thái Nguyên participated in three ‘waves’ of rent reductions and 75 more during three ‘waves’ of land reforms, respectively, indicating that the department had ample information on the ‘errors’ that occurred via prior ‘recapitulation’ reports. Yet, the department's report offers no substantive reflections on the results to date.Footnote 65

The silence on the consolidation of the ‘reorganised’ cells was not complete, however. The Central Land Reform Committee published a ‘lessons learned’ volume entitled, Mission leadership experiences during the rent reductions and land reforms, in April of 1955.Footnote 66 The contents, which primarily consisted of ‘recapitulation’ reports, including several from Thái Nguyên, were presumably once again troubling from a leadership point of view. As one Thái Nguyên report put it, each step of the campaign was implemented ‘out-of-order’ because the cadres were ‘disorganised’, did not understand ‘specific methods’, and ‘lacked personal experience’.Footnote 67 Similar confessions appear throughout the volume. The significance of the volume is difficult to assess, however. As is the case with all of the ‘recapitulation’ reports, the number of copies published, the extent of their circulation, and their actual impact of the ‘experiential lessons learned’ on other teams as well as policymakers is unknown. So, too, is the importance of the timing of the volume's release, which came three months prior to the massive volume the Central Land Reform Committee published on experiences with the ‘reorganisation’ of rural Party cells, which was based on ‘recapitulation’ reports from teams working in a half-dozen different provinces. The first volume's narrow focus, how to improve the teams’ leadership through emulating the positive examples of others, suggests that the committee had by that point recognised the nature of the problems to date. But, as the content of the policies connected with the ‘Rectification of Errors’ campaign that officially began in October of 1956 made clear, the ‘experiential lessons learned’ went largely unheeded.

The Party, presenting itself as a unified whole in the form of a conference resolution, issued a response to the disorder at the start of the ‘Rectification’ campaign. The resolution announced the disciplining of two senior officials: Hồ Việt Thắng, who oversaw the work of the Central Land Reform Committee, and Lê Văn Lương, who directed the ‘reorganisation’ process. The resolution listed their respective punishments. For Lê Văn Lương, it was his expulsion from both the Politburo and the Party Secretariat, as well as his demotion within the Party's Executive Committee.Footnote 68 The following month, the Department of Organisation also removed him from his post. Both men made for convenient scapegoats due to their leadership positions. Neither of the men were solely responsible for all the policy decisions, however. While Lê Văn Lương personally signed many of the instructions concerning ‘reorganisation’, it was the Party Secretariat that attached its name as the issuing authority of the Instructions promulgated during the campaign. None of the Secretariat's other members are known to have suffered any public punishment for their roles in the debacle.Footnote 69

Conclusion

‘Failure is always framed… failure is also rhetoric and narrative, and it engages in communicative and storytelling devices that influence models of coping with and coming to terms with it.’Footnote 70 Kessler, again quoted here, identified three patterns in which this coping and coming to terms occurs in neoliberal contexts: failure as empirical irregularity, failure as miscommunication, and failure as a mode of organisation. These framings clearly function as post hoc attributes of blame, he explains. But, as Kessler demonstrates, these frames do not fundamentally challenge the structures and logic of neoliberalism itself, meaning that future failures will continue to successfully serve the interests of capital.

Despite immense differences in context, the ‘recapitulation’ reports exhibited some surprising parallels in terms of the framing of failure. Report authors typically used each step in the mobilisation model to structure their narratives. The section on ‘reorganisation’ consisted of three sub-steps: cell assessment, cell purification, and then cell consolidation. My analysis adopted this structure to highlight what did and did not change during each sub-step of the process over successive ‘waves’ in Thái Nguyên Province. Close attention to the patterned descriptions of ‘shortcomings’, ‘limitations’, ‘mistakes’, as well as more serious ‘errors’ that occurred during ‘reorganisation’ reveals that all three of Kessler's framings were also in evidence, albeit expressed in terms that reflected the revolutionary context of the time. Importantly, these patterns additionally reveal how the report authors described where success ended and failure began, making some implementation outcomes visible to the reader and others invisible.

Failure in terms of empirical irregularities focused on the consistent misidentification and/or mischaracterisation of peoples’ ‘class fractions’ (landlords, rich peasants, etc.) by cadres, allegedly due to their poor grasp of official policies. The conclusion, however, made no mention of the fact that policymakers assigned quotas that required the mobilisation teams to label a fixed percentage of people as ‘class enemies’ when in empirical fact they generally were not. There was a related silence in the reports on the many ways ordinary people exploited the process to hide the true extent of their property holdings and wealth or to carry out vendettas against others, a tactic known as ‘fishing in troubled waters’. Not surprisingly, the resulting chaos produced significant conflict between ‘old’ and ‘new’ members of the ‘reorganised’ cells, hindering consolidation and subsequent policy implementation.

Failure in terms of miscommunication took multiple forms as well, the most serious silence arguably being the vaguely worded central-level policies themselves. Ironically, the majority of these policy documents were titled ‘Instructions’ (chỉ thị). Their content did become somewhat more detailed over time, especially during the ‘Rectification of Errors’ campaign.Footnote 71 However, the Instructions prior to that point did not provide significant ‘how-to’ guidance to mobilisation cadres, leaving them largely to their own devices. Consequently, the implementation failures, attributed to the mobilisation cadres as well as the ‘reorganised’ cell members, served as a major focus of the reports, while the inadequacies of the Instructions went unremarked upon.Footnote 72

Finally, a silence regarding failure as a mode of organisation took striking form. Bluntly, the mobilisation model itself went without any critique. This deafening silence may reflect the fact that report authors were well aware that any such critique would not be tolerated in this political climate, especially in light of the massive purges of Party cadres that occurred during 1951–1952.Footnote 73 A ‘public secret’, according to Michael Taussig is ‘knowing what to know’, particularly in contexts of violence.Footnote 74 Here, a public secret can be understood as knowing what not to write, which may have been partly the case with the reports. But, given the official position on the efficacy of emulation in terms of personal and collective transformation, as well as high levels of cadre ideological indoctrination, the silence may also reflect knowing what not to question.

It should be stressed that the reported failures were not specific to Thái Nguyen Province. Contemporaneous ‘recapitulation’ reports covering ‘waves’ in other provinces were quite similar. Central-level policies on ‘reorganisation’ later selected and published in the Complete collection of Party documents provide further support for this conclusion. The number of policies promulgated on ‘reorganisation’ jumped from 1 in 1954, 2 in 1955, to 11 in 1956. Despite this sharp increase, the policy documents reiterated the same findings in general terms meaning that no iterative policy learning appears to have occurred over time. The success of the campaign was very short-lived as a result. Indeed, the violent chaos genuinely threatened the Party's legitimacy at the time as well as the ability of the ‘reorganised’ cells to advance central-level policies in rural areas in its wake. The redistribution of land and other resources to people who had little or none prior to the campaign did not last long either. Initial efforts to collectivise agricultural began almost immediately after the ‘Rectification of Errors’ campaign. So too, did popular resistance to this development approach, and it seriously hampered subsequent efforts to ‘build socialism’ in the countryside for decades.Footnote 75 For these reasons, judgements as to what constitutes ‘success’ and ‘failure’, be they contemporaneous or after the fact, need also consider what types of histories and their temporalities such (re-)framings do and do not make possible to write.