Introduction

The perceived welfare deservingness of the unemployed, the elderly, the sick/disabled, and immigrants has been widely investigated in recent years (e.g. Kootstra, Reference Kootstra, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Laenen and Meuleman, Reference Laenen, Meuleman, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017; Reeskens and van der Meer, Reference Reeskens and van der Meer2019). Meanwhile, there are fewer studies on attitudes toward other groups of potential welfare beneficiaries, such as single parents. What is more, the available evidence is conflicting. Most of the studies investigate the undeserving public images of lazy, immoral single mothers, who were perceived as threatening the welfare state as well as traditional family values in the 1990s United States and United Kingdom (e.g. Duncan and Edwards, Reference Duncan and Edwards1999; Gilman, Reference Gilman2014; Monnat, Reference Monnat2010). In contrast, survey results (Roosma and Jeene, Reference Roosma, Jeene, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017), even from the 1990s US (Groskind, Reference Groskind1991), show that people find single parents deserving based on their perceived need.

Meanwhile, more profound knowledge regarding the underlying factors of single mothers’ deservingness would be important, as single-parent households have a high poverty risk in most countries of the European Union and OECD, and single-mother families have an even higher risk compared to single-father families (Eurostat, 2020; The European Institute for Gender Equality, 2016; OECD, 2018). Hungary serves as an interesting case to investigate the underlying factors of single mothers’ perceived deservingness, as attitudes show a complicated picture. While a large majority of Hungarian voters see single mothers as deserving and needy, they also strongly prefer the traditional family (Herke, Reference Herke2021).

In this paper, we combine two theoretical approaches of deservingness research to study the determining factors of single mothers’ perceived deservingness. First, our analysis relies on the “CARIN” theory which claims that five criteria influence the perceived welfare deservingness of a group (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000; van Oorschot and Roosma, Reference van Oorschot, Roosma, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017). According to these criteria, those target groups seen (more) deserving in the eye of the public who: seem not responsible for their situation (control), seem grateful for the benefits they receive (attitude), have contributed, or will be able to contribute to the work of the welfare system (reciprocity), are similar to the majority society (identity) and seem in need of help (need). Second, we also incorporate the theory of the deservingness heuristic (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011), which argues that people judge recipients’ deservingness differently in the absence and presence of specific deservingness cues. If individuating information regarding a potential beneficiary is available, people disregard their political values and stereotypes and base their judgments on the deservingness heuristic, a psychological process developed during evolution to distinguish reciprocators from cheaters. Accordingly, we aim to answer two research questions in this paper: 1) Which CARIN criteria explain single mothers’ perceived deservingness in Hungary? 2) To what extent do the weights of the deservingness criteria regarding single mothers vary in the presence and absence of specific deservingness cues?

To account for both theories (i.e. to investigate the importance of the CARIN criteria in a situation that triggers the deservingness heuristic and also in another situation that does not), we use two different methods in our study. First, we investigate to what extent the acceptance of five statements, each measuring one of the CARIN criteria in the case of single mothers as a group, explains the overall deservingness of single mothers. Second, we conduct a vignette-based factorial survey experiment, where detailed information on individuals’ deservingness is available (the characteristics in the vignettes reflect on the CARIN criteria).

The article is structured as follows. First, we review earlier research findings on single mothers’ perceived deservingness and the deservingness heuristic, then we present the Hungarian context and form our hypotheses. Subsequently, we describe the methodology of the research and then analyse the results of both measurements. In the discussion and conclusions section, we summarize the main findings of our research.

Two theories of deservingness judgments

Single mothers and the five deservingness criteria

First, regarding the need criterion, Groskind (Reference Groskind1991) found in a vignette-based survey experiment that compared to two-parent families, where the father’s work status and effort to find a job (reciprocity and control criteria) were the most important, the number of children and the weekly income (both reflecting on the need criterion) were the most influential factors when US respondents evaluated the deservingness of single-mother families. In the case of single mothers, the mother’s work status and effort to find a job were even less important predictors than the absent father’s work status and effort, and the marital status of the mother (reflecting also on the control criterion) was not a significant predictor. The role of the need criterion is also supported by the results of Roosma and Jeene (Reference Roosma, Jeene, van Oorschot, Roosma, Meuleman and Reeskens2017), who found that Dutch survey respondents showed more leniency regarding benefit obligations in the case of those single parents who had younger children (higher level of need).

Other studies, however, highlight the importance of control criterion. Control is often understood as the responsibility for being alone with the children, which is usually measured by the marital status of the single mother. While widows cannot be blamed for living alone with their children, divorced and never-married single mothers are frequently seen as responsible for their situation (Battle, Reference Battle, Brekhus and Ignatow2019: 599). For instance, in American new poverty discourses of the 1980s, the narrators exclusively blamed single mothers, except the worthy widows (Fineman, Reference Fineman1991). Furthermore, van Oorschot (Reference van Oorschot2000: 38) found at the end of the 1990s that groups facing one of the acknowledged social risks have a higher score on the deservingness criteria. One of the investigated social risks was widowhood, besides being sick or disabled or being a pensioner. More recent research findings show that the perceived responsibility of becoming a single mother is still an important criterion. Baumberg et al. (Reference Baumberg, Bell and Gaffney2012: 26) found that British focus group participants ranked single parents as more deserving in cases where their partner had left them, while those who intentionally selected single parenthood were judged as less deserving.

There is also evidence about the importance of the other three deservingness criteria, but it is related to government and public discourses, and not public attitudes. The American welfare discourse of the 1990s was interwoven with the ‘welfare queen’ stereotype. Single mothers on welfare were depicted as black (identity), lazy (control) women from the lower classes (identity), who received more of the taxpayers’ money than they were entitled to (attitude) (Gilman, Reference Gilman2014: 259-260). Class-based stereotypes regarding single mothers who do not like to and do not work (low level of control and reciprocity) were also very salient in the welfare discourse of the 1990s in the UK, where single motherhood was strongly connected to teenage pregnancy as well (Duncan and Edwards, Reference Duncan and Edwards1999: 28-31). The latter one simultaneously reflected on the identity and reciprocity criteria, as teenage motherhood was seen as a form of parenting that deviates from middle-class norms (identity), while it was also associated with welfare dependency (low level of reciprocity) (Wilson and Huntington, Reference Wilson and Huntington2006).

The misuse of benefits (attitude) was also present in recent debates about single mothers’ welfare in Denmark (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2018), but in a different context. The Danish legislation defines that single mothers are entitled to extra benefits only in cases where they are ‘genuinely single’. However, it is hard to identify who is genuinely single, which means that the person does not have a marriage-like relationship. This uncertainty – which was also supported by the rising number of Muslim mothers on welfare benefits (identity) – had led to a fear of welfare fraud.

Based on the above findings, it could be hard to select one dominant criterion, as evidence is quite scattered regarding the time and place of the investigations. Furthermore, the role of the criteria could be dependent on available information on recipients’ deservingness.

Deservingness heuristic

According to the theory of deservingness heuristic (Petersen, Reference Petersen2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011), people rely on a psychological process developed during evolution to distinguish reciprocators from cheaters in interpersonal help-giving situations. The deservingness heuristic helps people to judge someone’s deservingness when a limited set of concrete cues are available and directs people’s attention especially to the perceived effort and reciprocity of the recipient. Those recipients who demonstrated low effort to avoid requiring others’ help are categorized as “cheaters”, while recipients who showed high effort (and consequently also demonstrated a willingness to contribute to the work of the community) but still in need of help are categorized as “reciprocators”. The automaticity of the heuristic implies that people disregard their values and stereotypes regarding the target group if enough information on the recipient is available, and people with and without related knowledge produce consistent judgments.

This theory, therefore, highlights the importance of control and reciprocity criteria in interpersonal settings. Within those settings, empirical results also proved the priority of these perceptions over political values and stereotypes in the case of public assistance recipients and the unemployed (Aarøe and Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Petersen, Reference Petersen2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011). Meanwhile, Jensen and Petersen (Reference Jensen and Petersen2017) highlight that the deservingness heuristic does not necessarily work in the same way regarding all target groups. They show that perceived control is a less dominant factor in the case of health care recipients compared to the unemployed, as sickness is in general more likely to be seen as a random and not a personally caused event.

Based on these findings, it seems relevant to include other deservingness criteria besides control and reciprocity in the investigation of the deservingness heuristic, as in the case of other target groups, the heuristic might drive the attention to other criteria.

CARIN and deservingness heuristic combined

We use these two theories together and combine their advantages to investigate the underlying factors of single mothers’ perceived deservingness. The CARIN deservingness theory is more detailed compared to the deservingness heuristic regarding the applied criteria predicting perceived deservingness, as it not only investigates the role of reciprocity and control but also attitude, identity, and need. Meanwhile, the theory of the deservingness heuristic is more nuanced compared to CARIN by considering the effect of the available information in predicting deservingness judgments. It states that in the absence of specific cues of deservingness, people tend to form an opinion based on their political values and stereotypes that are dependent on the societal context, while in the presence of specific deservingness cues, people use the heuristic to make judgments irrespective of the societal context.

The combination of these theories seems to allow us to explain previous conflicting results regarding single mothers’ deservingness. While stereotypes and values matter in the absence but not in the presence of deservingness cues, respondents of a survey experiment in the US (within which deservingness cues were specified) could have found single mothers deserving based on their neediness despite the negative stereotypes regarding single mothers’ laziness. Meanwhile, the result that control and reciprocity are less important criteria in the presence of deservingness cues – and people base their judgments mainly on the perceived need of the recipients (Groskind, Reference Groskind1991) – suggests that, similar to the case with health care recipients, the deservingness heuristic works differently in the case of single mothers. Accordingly, if there is a universal mechanism driving the attention to the perception of need, we should receive the same finding on Hungarian data. Therefore, we hypothesize that respondents will rely on their stereotypes and values in the absence of deservingness cues but will primarily judge single mothers’ deservingness based on their perceived need in the presence of deservingness cues. To formulate more detailed hypotheses for the context of the absence of deservingness cues, we briefly review the Hungarian context.

Single mothers in the Hungarian family policy system and welfare attitudes towards them

Hungarian family policy could be described as ‘welfare for the wealthy’ since the election of the second Orbán government in 2010 (Szikra, Reference Szikra2014). The main tool of this family policy, the tax allowance, provides a higher amount of available reduction for families with a higher level of income and with more children. This kind of distinction reflects on the reciprocity criterion, as it suggests that working families are more deserving. It also highlights the importance of the identity criterion, as the state aims to control the reproduction of lower classes by providing a higher level of reduction to better-off families.

Identity, however, is important also in another form in the current Hungarian family policy, as the government connects the declining fertility rate to the liberalization of relationships (Grzebalska and Pető, Reference Grzebalska and Pető2018: 4; Juhász, Reference Juhász2012: 4). As the support of the better-off families is paired with the promotion of the traditional family, single parents are finding themselves in an unfavourable position regarding both intentions. Their poverty and social exclusion risk is the highest from all types of households (Eurostat, 2020), so they are usually not better-off families; neither are they traditional families. Single-parent families are targeted with only the universal family allowance scheme that gives a symbolically higher amount to single parents compared to two-parent families. In addition, the family allowance continually loses its value, as the government has not indexed it with inflation since 2008.

While single parents are not well-targeted in the current benefit system, the public believes that single mothers need a higher level of state support (Gregor and Kováts, Reference Gregor and Kováts2018: 106). Furthermore, Herke (Reference Herke2021) previously showed that almost a third of survey respondents associated single motherhood with poverty and financial need in an open-ended question. The identity criterion measured as a distance between the public and the target group was also very frequent in the associations, as 20 percent of the respondents reflected on the incompleteness of single-mother families and the preference of the two-parent family. Despite this preference, perceptions of single mothers are quite positive regarding the other four deservingness criteria. These positive perceptions explain why the great majority (80%) of the respondents agreed that it is the role of the state to support single mothers. The complexity of the identity criterion, however, could also explain these results: while a large part of the public still believes that married people are happier, and a child needs both parents to live a happy life, the majority also accepts divorce as the best solution to marriage problems.

Hypotheses

The descriptive results presented above on public attitudes and policies suggest some differences regarding the importance of the five criteria in Hungary, based on which we formulate our hypotheses for the context of the absence of deservingness cues. First, we hypothesize that control, attitude, reciprocity, and need explain single mothers’ deservingness (H1), as most respondents found single mothers deserving based on these criteria; similarly, most of the respondents agreed that it is a role of the state to support single mothers. Second, we hypothesize that some aspects of the identity criterion (attitudes regarding divorce) explain the deservingness of single mothers, while others (attitudes regarding the need of both parents) do not (H2), because previous results showed that the family values of the Hungarian population are not entirely conservative. Third, as respondents most often associated single motherhood with the need and identity criteria in the open-ended question (hence, the strongest stereotypes in Hungary seem to be the financial neediness and the incompleteness of these families: perceptions which are also strengthened by the family policy system), but, as identity proved to be an incoherent criterion in the Hungarian context, we hypothesize that need has the highest relative importance from the five criteria. Relying on Groskind’s (Reference Groskind1991) results we suppose that the need criterion is going to be the strongest predictor not only in the absence but also in the presence of concrete deservingness cues (H3). Based on Petersen et al. (Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011), we also expect that family values influence public attitudes in the absence of deservingness cues, but do not affect dilemmas about concrete persons (H4).

Data and methods

For this study, a block of six survey items and a vignette-based survey experiment were designed. While the survey items measure single mothers’ deservingness in the absence of deservingness cues by asking about single mothers in general, the vignette experiment measures deservingness judgments in the presence of deservingness cues by asking about the deservingness of single mothers with specific characteristics. The dependent variables also capture two different aspects of deservingness (which are suitable to the contexts). In the absence of deservingness cues, the dependent variable is abstract and measures single mothers’ deservingness without concretizing the form of support. In contrast, in the presence of deservingness cues, the form and level of support are also concretized.

Both measurements were embedded in a larger survey that was asked on a quota sample of 2000 Hungarian adult internet users (age 18-65) in November 2018. The sample was selected from the respondent panel of one of the largest Hungarian polling firms, NRC. The sample was split at that point in the survey, where the blocks and the experiment would follow. Consequently, both of the six survey items and the survey experiment were asked from approximately 1000 respondents – as one of the two versions was randomly assigned to each respondent. The sample is similar to the Hungarian population regarding gender and settlement type – however, the lower educated and the younger segments of the population are underrepresented. Sampling weights were used in the analyses to correct for these differences.

Absence of deservingness cues – using statements

Five items measured the five deservingness criteria, and the following statement measured the overall deservingness of single mothers: “It’s a role of the state to support single mothers”. The five other statements were: “Most single mothers are responsible for remaining with their child/children alone” (control); “Most single mothers demand too much support from the state” (attitude); “Most single mothers work hard to make a living for the family” (control & reciprocity); “Single motherhood is not an uncommon situation” (identity); “Most single mothers have a bad financial situation” (need). The statement used for reciprocity also reflected on the control criterion, but in a different sense from the first statement. In this case, it measured the control over the current situation (i.e. they work hard to make a living for their family and avoid poverty) and not the control over causing the situation (i.e. becoming a single mother). The answers for the negative statements (control and attitude) were recoded for the analysis, to have the same direction for all of the questions.

To account for the incoherent family values of the Hungarian population that might affect the role of the identity criterion, we added additional statements to the questionnaire: “It is all right for a couple with an unhappy marriage to get a divorce even if they have children”; “A woman can have a child as a single parent even if she doesn’t want to have a stable relationship with a man”; “A child needs a home with both a father and a mother to grow up happily.”

Variables measuring deservingness, deservingness perceptions, and traditional family values were measured on the same scale: 1 – not agree at all, 2 – somewhat disagree, 3 – somewhat agree, 4 – absolutely agree, 0 – do not know/would not like to answer. The dependent variable (deservingness), and variables measuring deservingness perceptions and traditional family values, were recoded into binary ones (not agree=0; agree=1), and we used logistic regression models for the analysis. It helps to achieve a reasonable statistical power of the analysis (low number of respondents in the first category; N=20) and makes the interpretation of the parameters straightforward (we present ordered logit estimates with three outcomes in Table 1 of the online appendix, Supplementary Materials). The first model contains solely the deservingness perceptions, while family values are included in the second model. Due to the incoherent values of the population (and missing or only weak level of correlations between variables), family values variables are added separately to the models. Both models control for demographic variables (gender, age, education, settlement type, involvement). The analysis includes only those respondents who evaluated all deservingness and family values statements, therefore the sample was reduced to 725 respondents.

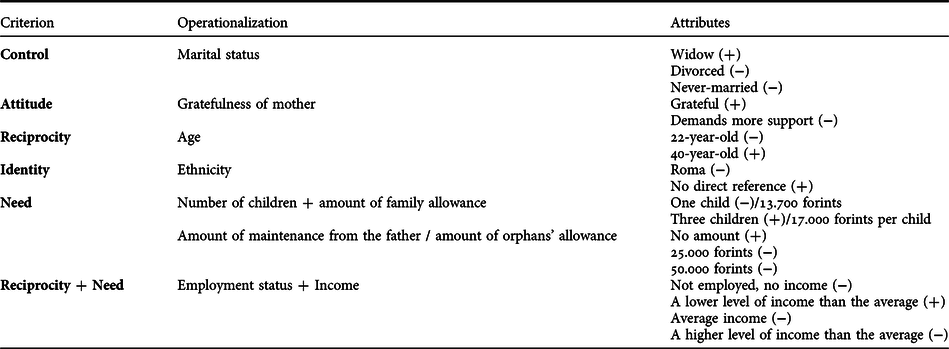

Table 1. Operationalization of the Deservingness Criteria in the Vignettes

Signs (+) and (−) show the expected effects: (+) = more deserving, (−) = less deserving

Presence of deservingness cues – A vignette-based factorial survey experiment

In the experiment, respondents were asked to evaluate the fairness of the family allowance of hypothetical single mothers. The characteristics of hypothetical single mothers were designed to reflect on the deservingness criteria. Seven characteristics were manipulated between the vignettes: each of them had two, three, or four categories. On the whole, the vignette universe covered 576 possible combinations of all characteristics (2x2x2x2x3x3x4). From this universe, we selected 100 vignettes with random sampling technique (without replacement). These vignettes were sorted randomly into ten distinct vignette decks, and all of them contained ten vignettes. In consequence, all respondents had to evaluate ten vignettes. Vignette decks and the order of the vignettes within decks were assigned to the respondents randomly.

Control was measured with the marital status of the mothers, as earlier studies (Battle, Reference Battle, Brekhus and Ignatow2019; Fineman, Reference Fineman1991) showed that widowed mothers are usually perceived as more deserving than divorced or never-married single mothers, because they could not be blamed for their situation. The attitude criterion was operationalized by concrete information about the gratefulness of the mothers towards the received support from the state. Reciprocity was measured in the vignettes with two factors. First, the descriptions provided information about the employment status of the mothers. This characteristic, however, was paired with information about the mothers’ income, which referred to the recipient’s neediness. Second, age was also used as a proxy variable of reciprocity; as, based on the deservingness logic, older mothers should be seen as more deserving, as they had more time to contribute to the work of the welfare system. Age could also be important because of negative stereotypes about teenage pregnancy – however, the younger age was set to 22 years, as using vignettes with 18-year-old mothers would have made some cases unrealistic.

In the case of single mothers, not only does personal income reflect on the level of need, but also the amount of maintenance received from the father of the child or the amount of the orphan’s pension. The number of children was also added as a factor of need. In this regard, the expectation is that the number of children increases the perceived deservingness of single mothers. Furthermore, the amount of the family allowance was systematically varied with the number of children: as, in Hungary, single parents with one child are entitled to a lower amount of money (13.700 forints ∼ 42 €) compared to lone parents with three children, who earn 17.000 forints (∼ 52 €) after each of their children.

While most of the criteria can be captured similarly in both measurements, identity is a problematic criterion. Identity on the abstract level was measured by the acceptance of single-mother families as an alternative to the traditional family. This dimension, however, could be applied in a context-specific way only if we would compare the deservingness of single-mother families with traditional families. Nevertheless, as respondents of the experiment also had to evaluate the same three statements of family values as respondents of the other measurement, we include these variables in the vignette analysis as respondent-level characteristics. Furthermore, Roma origin was included in the vignettes as another aspect of the identity criterion, as race and ethnicity proved to be an important factor in other welfare contexts (Foster, Reference Foster2008; Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2018).

The same ten female names were used in the ten vignette decks. As these are usual Hungarian names and were assigned to the vignettes randomly, they did not have a special role. Table 1 summarizes the vignette characteristics, attributes, and the measured criteria.

Consequently, in the most favourable vignette, the character is a widow (low level of control), 40-year-old (high level of reciprocity) non-Roma (absence of identity gap) single mother, who works (high level of reciprocity), but has a lower level of income than the average (high level of need). She has three children (high level of need) and does not receive orphan’s allowance (high level of need). She is grateful to the state for the family allowance (positive attitude). This vignette is the following:

“Erika is a 40-year-old, widowed single mother with three children. She works and has a lower level of income than the average wage. She is not entitled to an orphan’s allowance for her children and receives a family allowance of 17.000 forints for each of her children from the state. Erika is grateful for the support received from the state.”

Each vignette was followed by the question: ‘In your opinion, the amount of family allowance of (name of the mother) is fair, unfairly too low, or unfairly too high?’ and respondents had to answer it on an 11-point scale, where -5 was labelled as unfairly too low, 0 as fair, and 5 as unfairly too high.

To evaluate the judgments on the vignettes, we considered the hierarchical design of the dataset: the sample of the hundred vignettes were clustered into ten different decks (Level 3), and each respondent (Level 2) had to evaluate one deck with ten vignettes. In consequence, vignettes (Level 1) were clustered within the other two levels. The decomposition of the variance showed that a two-level model was sufficient to use, as vignette decks explained only 0,005% of the variance. On the contrary, the respondent level explained 45% of the variance.

We used linear multilevel regression models for the estimation. The dependent variable was treated as a metric variable, as each level of the 11-point scale was used by the respondents, and there was a normal distribution of the values. In the original scale, the most deserving option had the lowest value (-5), while the least deserving, had the highest (5). This scale was reversed for the analysis to make understanding of the estimates easier: furthermore, each number was recomputed into positive numbers.

We estimated three models with the mixed command in Stata. The first model includes solely the vignette characteristics, while the family values of the respondents were added in the second model. The third model also contains the demographic characteristics of the respondents (gender, age, education, settlement type, involvement). Table 3, however, does not contain the results of the third model, as the coefficients of the deservingness variables are stable over the models. Of the 1021 respondents, only those who evaluated the family values questions as well were included in the analysis, resulting in 910 respondents and a 9100 vignettes large sample.

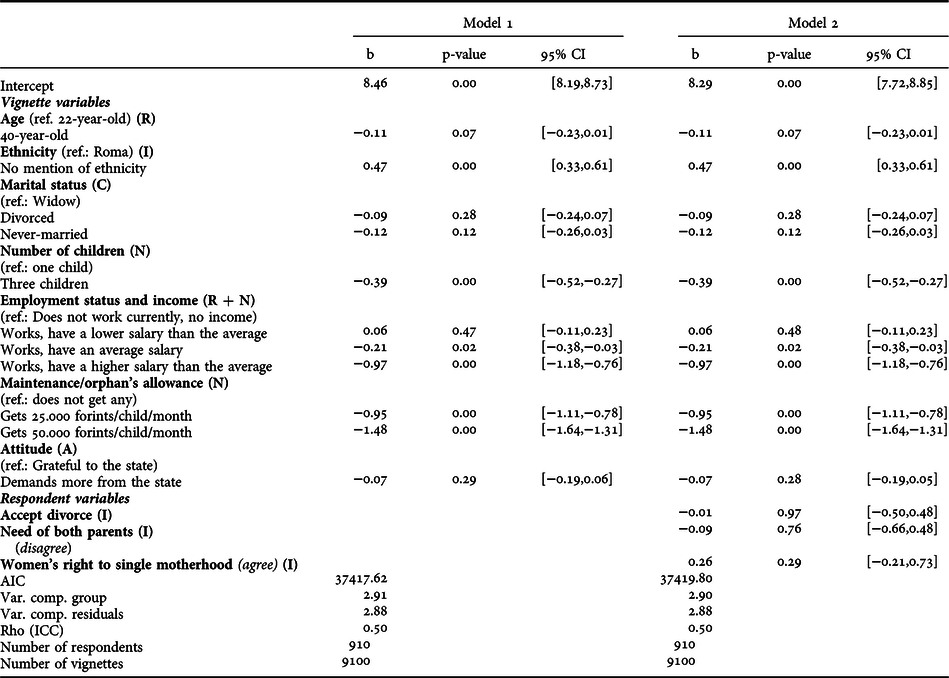

Table 3. Multilevel models of the vignette-based survey experiment

Notes: Dependent variable: ‘In your opinion, the amount of family allowance of (name of the mother) is fair, unfairly too low, or unfairly too high?’ (11-point scale). Initials of the reflected CARIN criteria are marked in parentheses after the attributes.

Results

Absence of deservingness cues – statements

From the respondents, 629 agreed and 96 disagreed with the statement that it is a role of the state to support single mothers. The overall level of deservingness of single mothers is quite high, and single mothers are clearly seen as deserving based on the ‘need’ and the mixed ‘control and reciprocity’ criterion (agreement level: 85%; 90%). There is a lower level of disagreement regarding the negative statements about control and attitude criteria (76%; 73%), while respondents are strongly divided regarding the item measuring identity (43% agree that single motherhood is not an uncommon situation). But which CARIN criteria explain the perceived deservingness of single mothers?

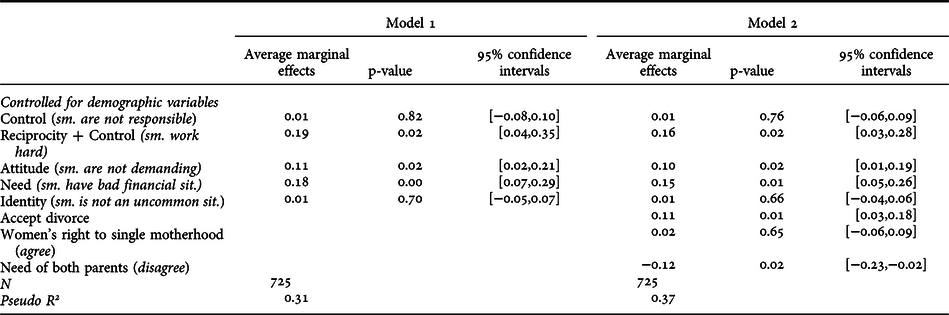

Table 2 shows that three of the five criteria have a significant effect on the overall deservingness variable, and these effects remain quite stable in the second model when the family values of the respondents are also included. Agreement with the statement about single mothers’ hard work (reciprocity + control) is associated with an almost 20 percentage point higher probability of agreeing with the dependent variable. Furthermore, the belief that single mothers have a bad financial situation (need) means an 18 percentage point higher probability of finding the state responsible to support single mothers. In addition, finding single mothers not demanding (attitude) increases the probability by 11 percentage points. Agreeing statements about the control and identity criteria do not affect the overall deservingness variable.

Table 2. Average marginal effects of deservingness perceptions and traditional family values

Note: Dependent variable: “It’s a role of the state to support single mothers” (0=not agree; 1=agree).

The results of the second model reveal a quite interesting relationship: those who disagree that a child needs both parents to live a happy life are more likely to believe that it is not the role of the state to support single mothers. Based on the deservingness logic, we expected that agreeing with this statement would decrease the probability of finding single mothers deserving. We supposed the belief that the ideal family is the two-parent one also incorporates the concept that other family forms, such as single-parent families, should not be supported by the state. The negative relationship, however, suggests something different. The belief that single parents could provide a happy life for their children seems to incorporate the concept that they do not need extra help from the state. Regarding the acceptance of divorce, the result is in line with the expectation: the belief that divorce is an acceptable solution for marriage problems increases the probability of finding single mothers deserving of state support by eleven percentage points. These results contradict H2, as the acceptance of divorce, together with the belief that a child needs both parents to live a happy life, predicts higher level of deservingness of single mothers.

In addition, post estimation tests show that there is no significant difference between the coefficients of reciprocity/control and need (p=0.99), and need and attitude (p=0.69). The coefficient of belief about a child’s need of both parents is significantly different from the coefficient of need (p=0.00), but only due to the diverse directions of the two effects, while the sizes of these coefficients are also not significantly different (p=0.80). Finally, the difference is also not significant regarding the coefficients of accepting divorce and need (p=0.60). These tests partly support H1 as the results show that reciprocity/control, attitude and need, are all determinant deservingness criteria, while control (in the sense of causing the situation) is not. On the other hand, the priority of the need criterion (H3) is not supported, as there is not a single criterion that could be claimed as the most determinant one in this case.

Presence of deservingness cues – vignettes

The mean score of the dependent variable is 7,24, which strengthens that single mothers, in general, are perceived as a deserving group. Nevertheless, as Table 3 shows, all vignette characteristics, except marital status, attitude, and the age of the mother, have significantly influenced the evaluation of the deservingness of hypothetical single mothers.

The received amount of maintenance from the father/orphan’s allowance shows the highest coefficient, followed by the level of income. Post estimation tests indicate that these coefficients are significantly different from the others, proving that these characteristics influenced the evaluation to the highest extent, and supporting H3 about the priority of the need criterion. The number of children (also reflecting on the need criterion) indicates the fourth highest coefficient (after ethnicity). While the received amount of orphan’s allowance/maintenance from the father clearly proves that a higher level of financial need makes single mothers more deserving, the results of the other two dimensions require further explanation. As the dimension of income was linked to the employment status of the mother, it did not simply reflect on the role of the need criterion, but also on reciprocity. The results of this mixed dimension prove that, in this situation, need is more important than reciprocity, as there is no significant difference between the evaluation of unemployed (low level of reciprocity) and employed (high level of reciprocity), but underpaid (high level of need), single mothers. The importance of the need criterion is also highlighted by the further results of this dimension, as single mothers with an average or high level of income were evaluated as less deserving compared to unemployed mothers. Regarding the last dimension of need, results show that single mothers with one child received significantly higher scores compared to mothers with three children. These results do not again solely reflect on the need criterion, as the number of children systematically varied with the amount of the family allowance. It rather shows that respondents do not agree with the principle that single mothers with more children need to receive a higher amount of support after each of their children.

The received amount of maintenance from the father/orphan’s allowance and the level of income were followed by the ethnicity of the mothers (identity). Similar to other contexts, results show that minority single mothers (in this case Roma) were judged as less deserving compared to those mothers whose ethnicity was not explicitly mentioned in the vignettes.

The difference regarding the age of the mother is not significant at the 5%, but only at the 10% level (p=0.07). Nevertheless, the results show that older single mothers earned lower scores on the scale compared to younger mothers, which might have happened because age was not understood as a proxy of reciprocity, but as a factor of need. Respondents might believe that younger mothers need more financial help as they usually have less work experience than older mothers. Cross-level interaction effects (Table 2 in the online appendix), however, show that the understanding of this attribute was diverse between different groups. Men and people above the age of 50 were less likely to differentiate between older and younger single mothers compared to women and people between the ages of 18 and 29. These groups might also have associated young single motherhood with a low level of reciprocity, or due to more conservative gender attitudes, with deviation from middle-class parenting norms (identity).

Family values variables were added in the second model – however, none of these variables had a significant effect on the evaluation. These results seem to confirm the theory of Petersen et al. (Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011) on the decreasing role of values in the presence of deservingness cues (H4). On the other hand, interaction effects show (Table 2 in the online appendix) that while these values did not have a direct effect on judgments, they did influence the understanding of some attributes. First, results indicate that people agreeing with women’s right to have a child without a stable relationship were less likely to differentiate between widow and never-married single mothers. Second, people disagreeing that ‘a child needs both parents to live a happy life’ found more deserving those single mothers who received the highest amount of child support, compared to people who agreed with this statement. At first sight, it seems to contradict the results of the previous method, which showed that people agreeing with this statement judge single mothers as more deserving. In this case, however, this relationship is mediated by the amount of child support/orphan’s pension received from the father/state. Therefore, it rather shows that people agreeing with this statement find single mothers more deserving because of the perceived lack of financial support from the father, and whenever this support is appropriately guaranteed, they are less supportive of state’s role in helping single mothers.

Discussion and conclusions

The article explored the relative weights of the deservingness criteria in predicting single mothers’ perceived deservingness with Hungarian data by using two different methods: regression analysis of statements and a vignette-based survey experiment. The article’s contribution to the literature is twofold. First, it provides a detailed investigation about the importance of the criteria in the case of single mothers, a group regarding previous studies showed scarce and conflicting results. Second, it combines two deservingness theories, CARIN (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000) and deservingness heuristic (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011), by investigating the importance of the CARIN deservingness criteria in the case of single mothers both in the presence and absence of deservingness cues.

We showed that beliefs about Hungarian single mothers’ strong work ethic, non-demanding attitude, and neediness, as well as liberal, but also some conservative family values, explain their perceived deservingness. These results also indicate that in the absence of specific deservingness cues, respondents relied on the attitude, reciprocity/control, and identity criteria as much as on the criterion of need. In contrast, in the presence of concrete deservingness cues, the perception of single mothers’ neediness became the strongest predictor, and the direct effects of perceived attitude and reciprocity, as well as family values, disappeared. These findings support the existence of the deservingness heuristic, as stereotypes and family values did matter in the absence of deservingness cues, while respondents disregarded them when specific cues of deservingness were available. In light of these results, it is also reasonable that even in the US, where strong negative stereotypes about single mothers’ welfare dependency exist, respondents in a vignette experiment (Groskind Reference Groskind1991) mainly relied on cues related to single-mother families’ neediness, instead of their perceived level of control and reciprocity (effort to find a job and employment status).

On the other hand, it seems that, compared to the unemployed and public assistance recipients (Aarøe and Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014; Petersen, Reference Petersen2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011), in the case of single mothers, the deservingness heuristic directs people’s attention towards cues of need, instead of control and reciprocity. Further research could explore the mechanisms behind this finding. One could hypothesize, for instance, that the perception of need might be more important regarding single mothers, due to the presence of a third party, their children. When specific information on single mothers’ financial situation is available, respondents are more likely to realize that these circumstances also affect the welfare of children. Thus, they focus more on children’s needs than mothers’ characteristics.

Similarly, it would be reasonable to think that this mechanism works in the same way in the case of two-parent families with children. However, Groskind (Reference Groskind1991) found that in those situations, respondents relied more on fathers’ perceived effort and employment status than families’ perceived level of need. This finding is in line with the assumption that the above mechanism also is driven by traditional gender roles (i.e. women’s role is to care for children, and men’s role is to make a living for the family), and suggests that it works this way only in the case of single mothers, and not in the case of single fathers. This gender bias in the mechanism of deservingness heuristic is further supported by our result that the most important attribute in the vignettes was the amount of child support/orphan’s allowance received from the father/state, and not the mother’s level of income. A future vignette study including single parents’ gender could test this hypothesis directly.

Our analysis also leads us to the conclusion that the theory of CARIN, which points to the diversity of potential factors behind judgments on deservingness, and the theory of deservingness heuristic that emphasizes the dependence of judgments on the presence of individuating information on welfare beneficiaries, together can explain the variance of public attitudes on welfare deservingness of different social groups. Further studies on the CARIN criteria might take into account the varying role of the criteria in the presence and absence of deservingness cues, while future studies on deservingness heuristic might test the role of other criteria besides control and reciprocity in the perception of different benefit groups.

Lastly, regarding the complexity of the Hungarian attitudes, our results revealed that, despite the population’s preference towards traditional family, some of the conservative beliefs such as “a child needs both parents to live a happy life” increases, not decreases, the perceived deservingness of single mothers. Therefore, single-mother families could also be seen as deserving in those societies, where a large majority of the population does not accept single-parent family as an alternative to the traditional one.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ivett Szalma, Wim van Oorschot, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of the article. Data collections were funded by the grant K 120070 of NKFIH (Hungarian Public Research Funding Agency).

Competing interests declaration

Competing interests: The authors declare none.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727942100074X