1. Introduction

The historical preference accorded to formal sector workers and the presence of large informal labour markets in Latin America left large segments of the population without social protection (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago1978). This situation began to change in the decade of the 2000s when the region experienced a period of sustained social policy expansion intended to increase protections for outsiders, i.e. individuals outside of formal employment not covered by contributory social insurance (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Garay, Reference Garay2016). Across the region, countries introduced reforms aimed at reducing inequalities in education, healthcare and pensions (Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). These changes marked a stark departure from both the long-standing tendency to privilege middle and upper class formal sector workers and the neoliberal turn of the previous period.

Social pensions are cash transfers aimed at providing income to older people – and often also to people with disability – who are not entitled to a contributory pension. The creation and extension of these programmes is emblematic of the turn towards inclusive social policies in Latin America. As stated by the OECD (2014), the expansion of social pensions is a global phenomenon but nowhere has it been more pronounced than in Latin America. Pension systems in the region have traditionally suffered from persistently low coverage, which was aggravated by the wave of privatization of the 1980-1990s (Brooks, Reference Brooks2009; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2008). A few countries already had non-contributory schemes in place at the turn of the decade, but the pace and number of reforms during the 2000s was unprecedented (Lloyd-Sherlock, Reference Lloyd-Sherlock2008; Rofman et al., Reference Rofman, Apella and Vezza2013). Eleven of the eighteen countries analysed in our study implemented a reform during this period, and for many it was the first social pension scheme ever implemented. These programmes are all aimed at diminishing inequalities in old-age income protection but have taken different forms. While Bolivia pays a universal benefit to all adults 65 years or older, several other systems make eligibility conditional on having an income below a certain threshold or not receiving a contributory pension. As a result, some countries have social pensions with nearly universal coverage and others cover only a small proportion of the population (Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago1978; Arza, Reference Arza2019). Why does social pensions coverage differ so strongly across countries?

Patterns of reforms in social pensions have received less attention than other non-contributory programmes typical of the inclusive turn such as conditional cash transfers and healthcare. Nonetheless, pensions represent the cornerstone of the Bismarckian type of welfare state typical of many Latin American countries and an area of intensive reform activity aimed at reducing inequalities in access to social protection (Arza, Reference Arza2019; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013; Rofman et al., Reference Rofman, Apella and Vezza2013). As such, they offer an interesting case study to investigate the political challenge of extending social protection in societies with deep insider-outsiders divides.

Several explanations have been offered of the inclusive turn in Latin American social policies (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). This scholarship generally identifies combinations of economic, institutional and political factors, in particular the rise in commodity prices, the consolidation of democracy and the strength of the Left in the period (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a; Levitsky and Roberts, Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011). The emphasis of this scholarship remains on the institutional arena and electoral dynamics. However, citizens engage in politics in different ways and in Latin America, where political institutions have historically been frail, protest is a pervasive element of the political landscape (Roberts, Reference Roberts2016; Silva, Reference Silva2015). Case study research has shown that social movements and popular mobilizations directly affected reforms (Anria and Niedzwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedzwiecki2016; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2014; Yoruk et al., Reference Yoruk, Oker and Sarlak2019), but there is a lack of systematic examination of the long-term effects of high levels of contention on social policy development in the region.

The aim of this paper is to extend current theoretical frameworks used to explain the inclusive turn in Latin American social policies by incorporating the long-term effect of protest.

We contend that in societies where contention played a larger role, the whole field of politics is itself structured differently with consequences on the dynamics of social policy reform. We use a two-step qualitative comparative analysis to investigate the influence of high levels of contention on reforms extending the coverage of social pensions in 18 Latin American countries (2000-2011). In the first step, we investigate the structural contexts faced by governments. In the second step, we incorporate proximate political conditions (protest, the strength of the Left, union density and electoral competition). By combining these two levels of analysis, this study aims to examine the ways in which the interplay between contentious and electoral politics influenced the expansion of social pensions in different contexts of need and opportunity for reform.

The article begins by tracing the historical trajectory of the welfare divide in Latin America. The following sections review explanations of the inclusive turn in the region and make a case for the incorporation of protest in the analyses of reforms expanding social protection for outsiders. The paper proceeds to describe data and method used and discusses the results of the analysis in light of the state-of-the-art. The final section offers concluding remarks.

2. The welfare divide in Latin America: origins and evolutions

Welfare state trajectories in Latin America differ in many ways from those of the advanced economies of Western Europe and North America (Segura-Ubiergo, Reference Segura-Ubiergo2007). The history of welfare state development in Latin America is generally viewed as a top-down process, as stated by Filgueira it is rather a “…history of elite accommodation, elite’s state building and elite’s attempts to co-opt and control non-elite sectors than a history of popular achievements and shaping from below” (Reference Filgueira2005: 4). Social policies in the 1960s and 1970s targeted strategic groups (military, civil servants) with new social security schemes progressively developed to incorporate the urban working and middle classes. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay were the pioneers in this period. The dominant pattern of welfare state construction followed a Bismarckian model, i.e. protection based on employment status (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a). Social policies were financed prevalently through high payroll contributions made possible by high tariff protections enjoyed by the manufacturing sector (also known as Import Substitution Industrialization). These welfare systems catered to a minority of the population and did not offer protection to those outside the formal labour market (Gough et al., Reference Gough, Wood, Barrientos, Bevan, Davis and Room2004). These systems were also inherently gender biased since women were over-represented in the informal economy and enjoyed fewer social rights including pension entitlements (Arza, Reference Arza2019). In many ways, this model represented an exclusionary version of European corporatism because of the absence of a social assistance pillar and deep insider-outsider divides between protected and unprotected sectors in societies.

The thrust towards the progressive incorporation of increasing shares of the population came to an end during the so-called lost decade of the 1980s. Despite a clear trend in the region toward more competitive and representative political systems, deep economic crises and the need to obtain external financial aid undermined governments’ ability to expand social protection. The widespread debt crisis provided institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank with leverage to impose structural adjustment policies inspired by the neoliberal doctrine (the “Washington consensus”). In the area of social policies, recommendations emphasized the privatization of social security, increasing reliance on market providers and the targeting of public resources only to the neediest groups (Barrientos et al., Reference Barrientos, Gideon and Molyneux2008; Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a). Social protection was further weakened by labour market and trade reforms that produced loss of industrial jobs, effectively reducing both the coverage and the funding sources of social security systems in the region. Pension programs were among the most deeply affected by the new measures. The Chilean pension reform of 1981 paved the way to the full or partial privatization of pension systems in almost all countries with developed social security systems in the region (Brooks, Reference Brooks2009; Mesa-Lago, Reference Mesa-Lago2008). The implementation of mandatory private accounts strengthened the link between individual benefits and past contributions (Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Bertranou and Bertranou2010; Hujo and Rulli, Reference Hujo and Rulli2014). These new pension systems did not perform well both in terms of coverage and benefit adequacy, and their legacy is still present today (Arza, Reference Arza2019).

Since the early 2000s Latin America is considered to have taken a decisive inclusive turn (Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea, Reference Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea2016; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). The magnitude of social policy change has been striking. The most significant innovation has been expansion of coverage to previously excluded groups such as workers in the informal sector and people with insufficient histories of contributions to social insurance. Although Latin America remains the most unequal region in the world, the Gini index fell on average 5 percent during this period and the share of people living in poverty declined from 45.9 to 30.7 (ECLAC, 2018). Reforms swept across all major policy sectors (Barrientos et al., Reference Barrientos, Gideon and Molyneux2008; Lloyd-Sherlock, Reference Lloyd-Sherlock2008). In this context, pensions systems became the object of intensive activity aimed at expanding their coverage (Rofman et al., Reference Rofman, Apella and Vezza2013). While Argentina backtracked on previous reforms making its pension system public again (Hujo and Rulli, Reference Hujo and Rulli2014; Arza, Reference Arza2019), several countries introduced a supplementary non-contributory public scheme for people without any social security or state-financed pension (Garay, Reference Garay2016). In Bolivia, former President Evo Morales replaced the universal pension already in place with a new scheme (Renta Dignidad) with a lower eligibility age (60 instead of 65) and without the cohort restrictions of the Bono Solidario that preceded it (Arza, Reference Arza2019). The former Chilean President Michelle Bachelet introduced a Basic Solidarity Pension in 2008 that guaranteed a minimum pension to older adults not entitled to contributory benefits conditional on residence, age and socio-economic criteria. The same reform also introduced a Solidarity Pension Contribution, a non-contributory supplement for older adults with some pension savings but low benefits (Arza, Reference Arza2019) Many other countries also introduced new social pension programmes in this period (Table 1).

Table 1. Social (non-contributory), pensions programmes, Latin American Countries, reforms 1919-2011

Source: ECLAC (2019a)

3. Explaining the inclusive turn in social pension in 2000s

The inclusive turn in Latin American social policy generated a rich literature trying to explain why some countries were more successful than others in expanding social protection. The theoretical frameworks generally used stress the importance of a combination of contextual and political factors.

Contextual factors include the rise in commodity prices providing governments with the necessary resources to finance the reforms (Levitsky and Roberts, Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011). Several authors also found that states with longer history of democratic development invested more in social policy. Democracy brought to the fore electoral pressure, thus making political leaders more sensitive to the needs and demands of low-income groups (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a; Segura-Ubiergo, Reference Segura-Ubiergo2007). A third set of factors concerns existing policy legacies (Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea, Reference Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). Governments in countries with larger welfare states and contributory pension systems with nearly universal coverage were less pressured to implement social pensions. Specific policy legacies in social pensions also influenced policymakers, although the direction of this effect is not clear cut. The presence of programmes already in place signals a pre-existing technical capacity and willingness of government to legislate in this area, but may also render further reforms unnecessary, especially in the context of already well-developed pension programmes. Overall, these factors – economic prosperity, democratic rule and favourable social policy legacies – were preconditions of expansive reforms, but do not alone explain why certain governments decided to implement such measures, while others facing similar contexts did not (Garay, Reference Garay2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013)

To understand the different reform patterns, we need to incorporate political actors. Given that the inclusive turn took place during a period of rise of left-wing governments in Latin America (the so-called pink tide), several authors have emphasized the importance of the political ideology of governments. Part of the literature posited that the strength of the Left was a key determinant of reforms (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a; Levitsky and Roberts, Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011); yet, a number of studies showed that in several cases significant policy innovations benefitting outsiders were introduced also by right-of-centre parties: for instance, in Chile, Mexico and Colombia (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Fairfield and Garay, Reference Fairfield and Garay2017; Niedzwiecki and Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017). This does not imply that partisanship did not matter for reform trajectories, but rather that its effect was more nuanced than sometimes assumed.

The extent to which parties across the ideological spectrum were willing to undertake reforms depends on further conditions. Electoral competition has been widely acknowledged as a factor driving social policy expansion in the period (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Ewig, Reference Ewig2016; Fairfield and Garay, Reference Fairfield and Garay2017; Garay, Reference Garay2016; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). Where competition was high, incumbents had strong incentives to appeal to broad sectors in society and social policy expansion was deemed as a critical tool to that end. In such context, both left- and right-wing parties were more prone to expand social pensions in order to broaden their electoral support.

The effect of social mobilization on policy expansion has received less systematic attention despite several case studies showing that social movements played a role in the introduction of measures for outsiders (Anria and Niedzwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedzwiecki2016; Garay, Reference Garay2007, Reference Garay2016; Niedzwiecki, Reference Niedzwiecki2014), and that the strength of civil society has implications for social policy change in Latin America (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020). In the next section, we focus on these aspects.

4. The effects of protest on social policy reform

Countries exhibit different institutionalized models of political behaviours and voting is only one of the means that citizens use to express their preferences (Fourcade and Schofer, Reference Fourcade and Schofer2016). The last three decades have seen a resurgence of protest in the region (Roberts, Reference Roberts2016; Silva, Reference Silva2015). These protests were a reaction not only to the high levels of inequality but also to a political situation in which institutions were perceived to be closed to the demands of particular groups of citizens. Compared to electoral politics, the protest arena is open to actors who lack regular access to institutional channels, and thus enhances political participation among traditionally excluded constituencies (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande and Dolezal2012). In the absence of readily available institutionalized channels to voice their discontent, these groups are likely to resort to protests to make demands for more egalitarian social policies and obtain concessions from political elites.

Elaborating on the insights provided by the scholarship on social movements outcomes (Amenta et al., Reference Amenta, Caren and Chiarello2010; Giugni, Reference Giugni2004; Piven and Cloward, Reference Piven and Cloward1979), we distinguish different types of effects of protest on policy-making based on their timing (short- vs. long-term) and the underlying causal mechanism (direct vs. mediated).

Direct effects are by definition short-term and refer to immediate responses of authorities such as a change in the political agenda of parties, the adoption of new measures by governments or the involvement of movements’ representatives in the policy process. However, direct effects are rare as protesters generally lack the power to force authorities to concede to their demands. The effects of protest are generally mediated, i.e. contingent on other characteristics such as the ability of protesters to sway public opinion in their favour and mount an electoral threat to incumbents, or forge alliances with institutional actors such as political parties and trade unions (Giugni, Reference Giugni2004; Ciccia and Guzman-Concha, Reference Ciccia and Guzman-Concha2018). An example of this type of effect is the decisive role played by the alliance between Left parties and popular movements in the adoption of the Renta Dignidad in Bolivia (Anria and Niedzwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedzwiecki2016).

While protest can sometimes produce short-term impacts, many effects of protest on policymaking take time to materialize. Some of the reasons why this occurs relate to the time of the policy process: it often requires several years for an issue to move to the government’s agenda and be legislated. Thus, there is always a certain lag between protest events and policy outputs. By long-term effects, we refer to impacts that occur long after the initial mobilization took place. Large scale episodes of unrest such as the Chilean student protests of 2011, the Piquetero movement in Argentina, or the Bolivian water wars significantly altered trajectories of social policy reform in these countries (Anria, Reference Anria2018; Garay, Reference Garay2007; Roberts, Reference Roberts2016). Some of these effects occurred because governments became more sensitized to the demands of certain sectors in society or feared the resurgence of mobilization (latent threat) (Yoruk et al., Reference Yoruk, Oker and Sarlak2019). Oftentimes, members of protest movements became actively involved in political parties, and sometimes protest movements established their own organizations to compete in the electoral arena. The latter was the case of the MAS in Bolivia. Other effects concern cultural changes produced as results of protesters entering into public opinion battles to gain visibility and legitimacy for their issues. Thus, long-term effects can also be mediated and include spill-overs whereby protests initially targeting specific policies produce changes in other sectors and larger impacts on the whole system of social protection. Fairfield and Garay (Reference Fairfield and Garay2017) offer an example of such effects when they recount how student mobilization in Chile in 2011 did not only push the government to initiate substantial education reform but also placed additional social policy and tax reforms on the government’s agenda.

In sum, the effect of protest on policy-making is often not linear and immediate, but rather diffused and contingent on the characteristics of contexts in which governments operate and the ways in which contentious and electoral politics interact and shape each other. In this article, we take a long-term perspective to comparatively examine the cumulative effect of protest over time. We contend that in societies where contention plays a larger role, the whole field of politics is itself structured differently with consequences on the dynamics of social policy reform.

5. Data and Method

We employ a two-step fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) (Schneider and Wagemann, 2006) to investigate the long-term influence of protests on reforms extending the coverage of social pensions between 2000 and 2011 in 18 Latin American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a set-theoretic method which aims to detect complex causal relations between combinations of conditions and an outcome. These relationships are interpreted in terms of necessity (the outcome is always present when the condition is also present) and sufficiency (the condition is always present when the outcome is also present; Ragin, Reference Ragin2000). A QCA usually yields a number of solutions (or combinations of conditions) leading to the outcome. Indeed, an important advantage of this method is its emphasis on equifinality, i.e. the existence of multiple causal pathways to a given outcome. Consistency is a measure of goodness of fit or degree of validity of each configuration, and is measured as the proportion of cases showing particular combination of conditions which presents also the outcome. A consistency of 1 corresponds to the perfect intersection between conditions and outcome sets.

The two-step procedure adopted here was developed by Schneider and Wagemann (Reference Schneider and Wagemann2006) to deal with the problems of limited diversity, and is based on the distinction between remote and proximate conditions which are progressively entered in the analysis. In the first step, we consider conditions such as the level of economic growth, social expenditure, the share of the labour force affiliated to contributory pension schemes, pre-existing legacies of social pensions, and the history of democratic development (see table 2). Our assumption is that the way these conditions combine in particular settings describes different contexts of need and opportunity for reforms. For instance, a low coverage rate of contributory schemes and the lack of previous legislation on social pensions create greater need for incisive reforms, while sustained economic growth generates revenues which governments can then decide to ‘invest’ in expanding social pensions. In the second step, we incorporate proximate political conditions: the cumulative frequency of protests, the share of left-wing seats in parliament, union density, and political competition. By combining these two levels of analysis, this study aims to examine the ways in which the nexus between protest, parties and social policy is sensitive to the characteristics of contexts.

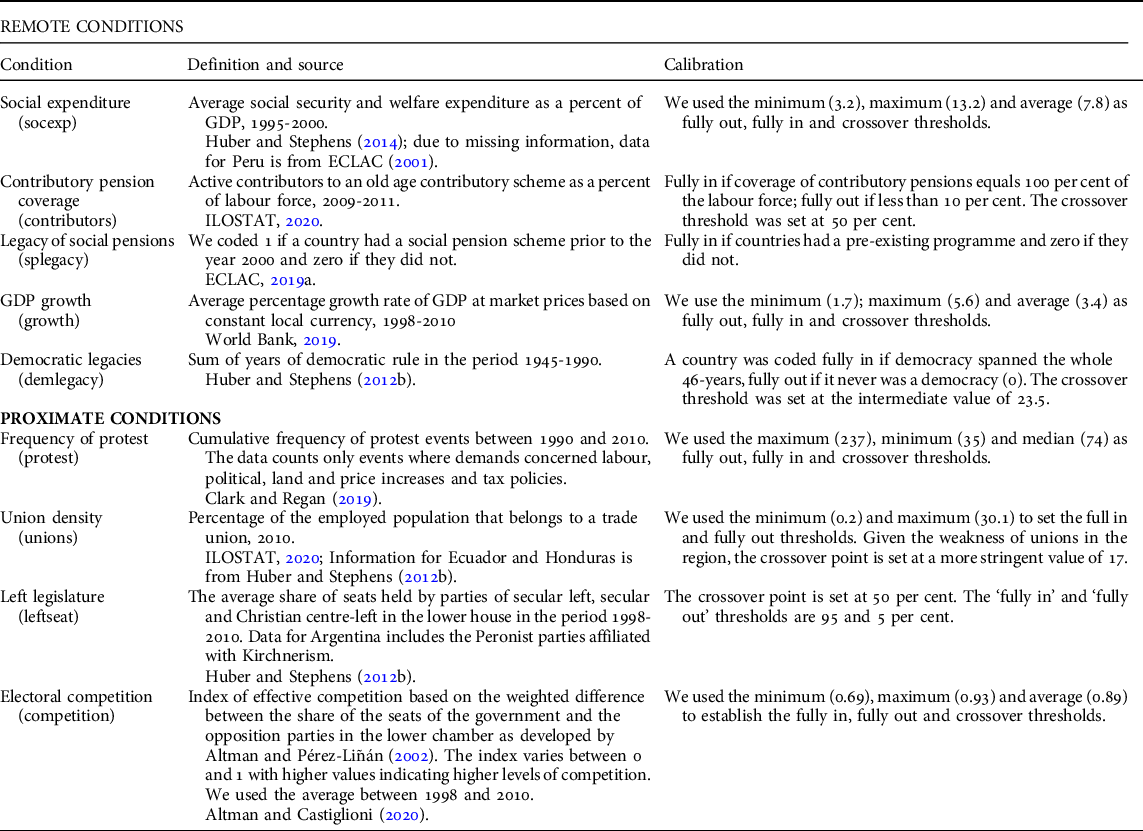

Table 2. Conditions, definitions and calibration

We began the analysis by transforming the raw data into fuzzy scores (calibration). Fuzzy scores vary between 0 and 1 and represent degrees of membership of cases in each condition and outcome sets (Ragin, Reference Ragin2000). The calibration entails the choice of three thresholds: full membership (0.95), full exclusion (0.05) and the crossover point (0.50) (Ragin, Reference Ragin2000). We used a mix of empirical, case and conceptual knowledge to identify thresholds (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). For four conditions (social expenditure, GDP growth, protest, electoral competition), we use the minimum, maximum and average values of the distribution. This implies that they should be interpreted in relative terms: e.g. if a country scores above 0.50 in social expenditure, it means that it is relatively more generous than other countries. For union density, we considered that trade unionism is generally weak in the region with a few exceptions represented by Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Uruguay (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2012a). In this case, the average is a biased threshold and so we resort to case knowledge to set the crossover point at a value (17) slightly inferior to that of those countries. For coverage of contributory pensions, legacy of social pensions and democracy, we use substantive criteria reflecting the presence and absence of the underlying phenomena. Table 2 details information about measures and calibration for all conditionsFootnote 1 . In what follows, we illustrate the approach used to measure the outcome and protest variables.

Measuring the expansion of social pension coverage

To measure the expansion of social pensions, we constructed an index which considered the extent to which new programmes effectively addressed poverty at the beginning of the period. Given our focus on the decade of the 2000s, we considered only programmes introduced in this period (table 1) and constructed an index of expansion of coverage of social pension using data from ECLAC (2019a). This index measured social pension expansion as the ratio between the coverage achieved in 2011 and the percentage of population over 65 years old living in poverty in 2000 (ECLAC, 2019b). For instance, the Basic Solidarity Pension in Chile achieved a coverage of 17 per cent in 2011 which corresponded to 64 per cent of the older-age population living in poverty in 2000.

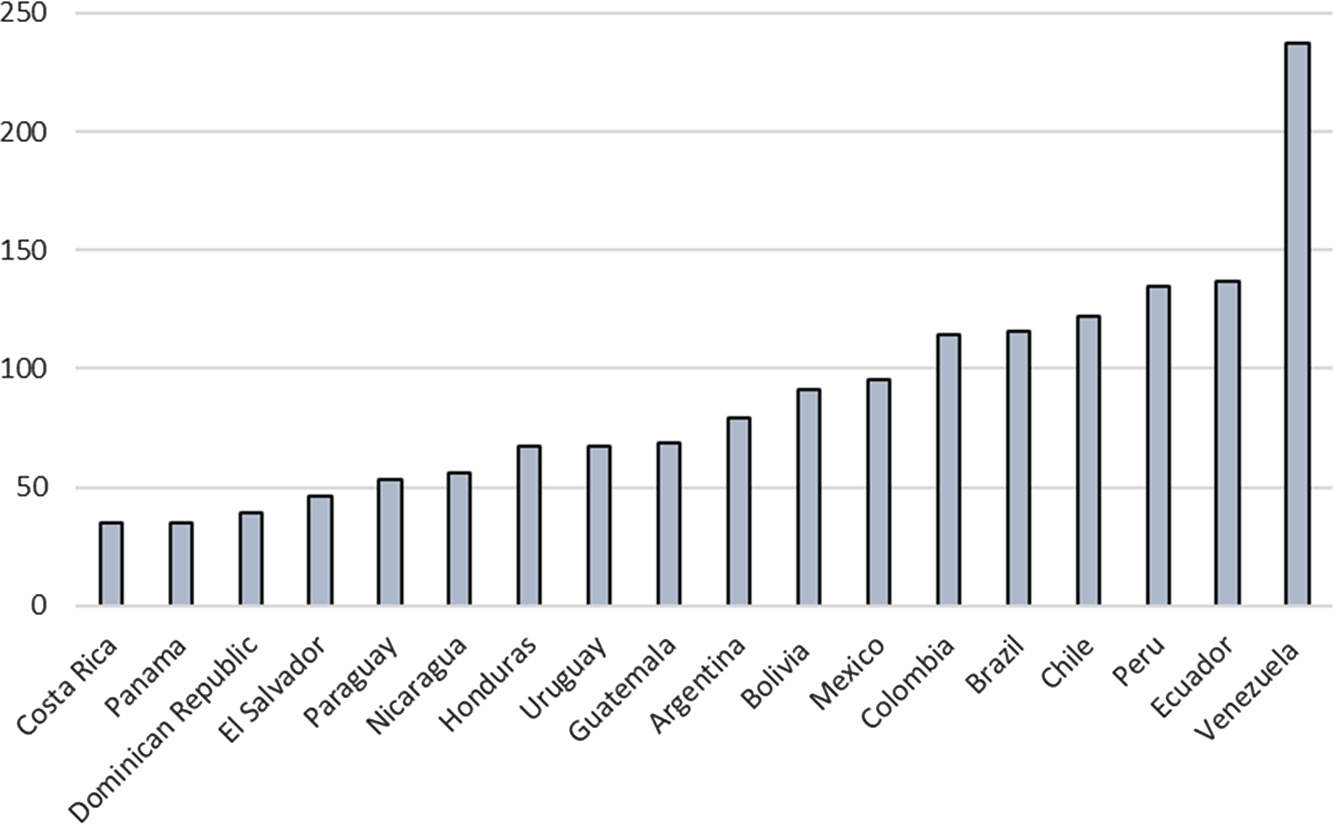

The thresholds used to calibrate this variable are 100 (fully in), 30 (crossover) and 1 (fully out) per cent. In the period investigated, 11 of the 18 countries analysed introduced a new social pension scheme, but only in seven the coverage was above the 30 per cent threshold (figure 1). The choice of this threshold reflects the consideration that programmes that did not reach at least a substantial proportion of the poor cannot be considered veritable cases of expansion. For instance, this was the case of Peru and El Salvador where coverage remained at less than 1 per cent of poverty rates. Conversely, values above 100 like the one in Bolivia (154) indicate that social pensions do not only cater to the poor but also reach other segments of the older-age population. Ecuador, Chile and Venezuela also perform well and have coverage rates between 60-75 per cent. Of the seven countries that did not undertake a reform, Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica and Uruguay already had social pension schemes and extensive contributory pension systems in place (see also table 1). In Brazil, the rural pension scheme (Previdencia Rural) underwent a major expansion and improvement of replacement rates already in the 1990s in the wake of the implementation of the 1988 Constitution (Lloyd-Sherlock, Reference Lloyd-Sherlock2008). Although Argentina did not reform its social pension scheme in this period, it changed its contributory system. The system was transformed back to a public pay-as-you-go system in 2008 and a moratorium further allowed people with insufficient histories of contribution to receive a pension. This measure produced a massive increase in coverage rates, especially among women. Nonetheless, this reform did not establish a universal pillar of basic provisions (Arza, Reference Arza2019).

FIGURE 1. Index of expansion of social pension coverage, 2000-2011*

*This index measures the ratio between the coverage achieved in 2011 and the poverty rate of the population over 65 years old in 2000.

Measuring protest

We use information provided by the Mass Mobilization (MM) project to measure the magnitude of protest in the region. This data was collected by searching Lexis-Nexis for terms such as “protest”, “demonstration”, “riot” and “mass mobilization” in four quality newspapers. A minimum threshold of 50 participants was used to report events (for more details see, Clark and Regan, Reference Clark and Regan2019). We selected protests that took place between 1990 and 2010, and where demands concerned socio-economic and political issues. The cumulative frequency over a 21-year period describes differences in the extent to which protests were a more (or less) regular feature of political expression across countries. By proceeding in this manner, we are thus not assessing the direct relationship between specific protests and government responses (or lack thereof), but rather the relationship between certain configurations of the polity and the medium and long-term propensity of governments to expand social pensions schemes.

As shown in figure 2, the frequency of protests varies from a minimum of 35 in Costa Rica to a maximum of 237 events in Venezuela. Other countries exhibiting high level of contention are Ecuador, Peru and Chile, while the lowest levels of contention are found in Costa Rica, Panama and Dominican Republic.

FIGURE 2. Cumulative frequency of protest events, 1990-2010

6. Results

In this section, we illustrate the results of the analysis. Having verified that no single condition was necessary for the occurrence of the outcome, we proceeded with the two-step analysis of sufficiency.

Step 1: The contexts of social pension expansion

The first step examined the combinations of contextual conditions under which a given outcome is made possible. Therefore, we did not establish a consistency threshold at this stage (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2006). The sufficiency analysis yielded six contexts (C1-C6). Table 3 reports membership scores for the cases in each context and their respective score in the outcome. As anticipated, this analysis generated several contradictory configurations, i.e. combinations including cases with both high and low scores in the outcome. We expected that the introduction of political variables in the second step would discriminate between them.

Table 3. Countries’ fuzzy scores in the outcome and context configurations

Note: scores in bold indicate membership scores (above 0.50) in the outcome.

Table 4 shows the specific combination of conditions for each of the six contexts. Uppercase characters indicate the presence of the condition, lowercases indicate its absence; * indicates the logical connector “and”. These contextual configurations showed different situations of need (C1, C2, C3), opportunity (C6) and no need for reforms (C4, C5).

Table 4. Context configurations

Contexts C1, C2, C3 generated considerable pressure on governments to legislate on social pensions because of the low coverage of pension systems. C1 and C2 characterize countries with less developed welfare states and a low share of the population affiliated to contributory systems. The majority of cases (11) belonged to these contexts. These conditions combined with the lack of a pre-existing social pension programmes in C1, and favourable economic conditions but weak democratic legacies in C2. Despite the presence of more developed welfare states, C3 is also a context of high need for reform because of the limited development of contributory systems. Brazil and Colombia belonged to this context.

Contexts 4 to 6 were characterized instead by relatively more developed welfare states with large contributory programmes. As discussed in section three, the occurrence of expansionary reforms in these contexts is less probable when social pension schemes are already in place. Indeed, Argentina, Costa Rica and Uruguay exhibiting this combination of conditions (C4, C5) did not introduce new social pension schemes. Conversely, in countries where these conditions combined with the lack of specific policy legacies and sustained economic growth, governments faced opportunities to implement reforms. As expected, C6 contains only cases of expansion of social pension (Chile and Panama).

Step 2. Proximate political conditions of expansion

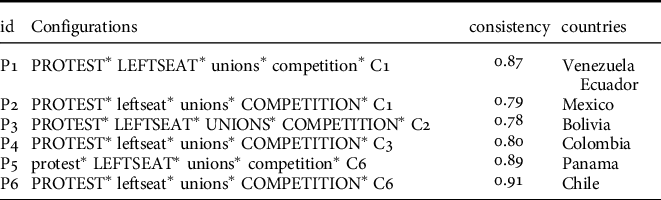

We then examined the effect of political conditions on the adoption of expansive social pension reforms. We ran four models for each context presenting cases with positive outcomes (C1, C2, C3 and C6). The intermediate solution identified six configurations with high consistency levels. As expected, the introduction of political conditions eliminated contradictory cases, and the seven cases with positive outcomes were all included in one of the formulas. Protest was present in five of the six configurations leading to significant expansions of social pensions (table 5).

Table 5. Analysis of sufficient conditions for the outcome expansion of social pension

The six formulas were further minimized by highlighting common terms and eliminating redundant conditions (Schneider and Wagemann, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). Thus, configurations P2, P4 and P6 become [PROTEST*leftseat*unions*COMPETITION] in C1 or C3 or C6. This explanatory pattern shows that the combination of sustained protest and higher levels of political competition drove governments to implement the reforms in countries where both unions and left-wing parties in parliament were relatively weak. This configuration occurred in countries facing both contexts of relatively strong need (Chile, Colombia and Mexico) and opportunity (Chile) for reforms. It should be noted that, with the exception of Chile where the reform was carried out by a centre-left coalition, the schemes introduced were narrower and more restrictive than those in other countries (figure 1). The configurations P1 and P3 were summarized as [PROTEST * LEFTSEAT] in C1 or C3. This configuration highlighted the combined effect of sustained protests and strong left-parties in government in countries facing contexts of high need for reform because of the limited coverage of contributory pension systems.

Panama represented a slightly different pattern from the ones described above. The country showed a strong presence of the Left, but low levels of protest, union density and political competition. However, this difference can be in part explained by the fact that the country faced a relatively favourable context of sustained economic growth and relatively high coverage of the contributory pension system (Rofman et al., Reference Rofman, Apella and Vezza2013).

7. Discussion

Our main finding is that reform trajectories in more contentious societies differed from those where social conflict was less prominent. Five of the six configurations leading to an expansion of social pensions show the presence of high level of protests. The two main explanatory patterns identified are: 1) sustained protest and high electoral competition pushed the expansion of social pensions in countries where the Left and unions were relatively weak (Chile, Colombia, Mexico); 2) a strong Left in parliament and high levels of contention led to the expansion of social pensions in countries with limited coverage of contributory pensions systems and strong need for reforms (Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela). The second pattern led to more inclusive reforms with higher levels of coverage. These findings are in line with previous research showing the existence of two distinct paths behind the inclusive turn (Garay, Reference Garay2007; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013). However, they add to this scholarship by showing that diffused social conflict was an important reason why conservative governments were sometimes induced to increase social protection for outsiders. It also shows that, while the Left was more inclined to expand social pensions (Panama), more extensive measures were introduced in countries with significant levels of protest (Venezuela, Ecuador), sometimes in combination with the presence of supportive labour organizations and higher electoral competition (Bolivia) (Anria and Niedzwiecki, Reference Anria and Niedzwiecki2016).

These results also contribute to debates about the role of political ideology and electoral competition in the expansion of social policies (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Fairfield and Garay, Reference Fairfield and Garay2017; Niedzwiecki and Pribble, Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017; Pribble, Reference Pribble2013) by showing that, in highly competitive contexts, widespread protests induced parties across the ideological spectrum to extend measures for outsiders. Overall, the findings of this article advance knowledge on the impact of protest on social policy reform and shed light on the political challenge of extending social benefits in societies with deep insider-outsiders divides.

8. Conclusions

Our results contribute to debates about the determinants of equitable social policy in Latin America (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2020; Martinez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea, Reference Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea2016) by showing that the interplay between contentious and electoral politics shaped the expansion of social pensions in Latin America in contexts of strong need (limited coverage of contributory systems) and/or opportunities provided by the favourable economic trend in the period under study. In particular, protest was present in five of the six configurations leading to significant expansion in social pension coverage. However, its effect was mediated by other characteristics such as the political ideology of governments, the levels of electoral competition and the strength of unions.

Protest is a regular feature of the democratic game and an important channel of expression of citizens’ preferences (Almeida, Reference Almeida2014; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande and Dolezal2012). Our findings bring support to the idea that the overall configuration of the polity is different in more contentious societies, and that social policy reforms are the outcomes of political struggles and power relations that take place in both the electoral and protest arena, and thus depend on negotiations across all these political environments. However, social policy analyses rarely considered the potential impact of protests on reforms (Amenta, Reference Amenta2006; Amenta et al., Reference Amenta, Caren and Olasky2005; Ciccia and Guzman-Concha, Reference Ciccia and Guzman-Concha2018; Yoruk et al., Reference Yoruk, Oker and Sarlak2019). The field remains overall focused on electoral dynamics, political parties’ behaviour and the ideology of governments. These aspects remain important, but in this article we made a case for expanding the theoretical frameworks to incorporate their relationship with contentious politics.

Future research should try to characterize the relationship between electoral and contentious politics in at least two directions. First, while our study shows that protest matters for the expansion of social protections for outsiders, its comparative nature did not allow to appraise the detailed mechanisms through which protests influenced policy development in particular cases. Case study research would be valuable to understand the nature of different types of effects of protest. Secondly, the findings presented here hold only for the specific policy field of social pensions, and more research is needed to assess their validity with regard to other policy sectors, particularly contributory programmes.

The expansion of social pensions in Latin America has represented an important step in the advancement of the right to a basic income in old age for many social groups without affiliation to contributory pension systems. In contrast to the previous wave of pension privatizations, they also reintroduced greater mechanisms of solidarity (Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Bertranou and Bertranou2010). Nonetheless, severe inequalities continue to exist (Lloyd-Sherlock, Reference Lloyd-Sherlock2008). In the majority of countries, social pensions were constructed in parallel to contributory programmes, and provide benefits of limited amount. With the exception of Chile and Venezuela, social pension benefits ranged between 12 and 50 per cent of the average monthly pensionFootnote 2 . Other countries such as Argentina, Uruguay or Brazil have gone further in transforming the nature of their pension systems by raising contributory pension coverage and/or providing higher basic benefits (Arza, Reference Arza2019). In all cases where social pensions were added as a universal minimal or means-tested anti-poverty measure there is a need of further reforms to overcome the dualistic nature of pension systems.

Acknowledgements

The research on which this article is based has been funded by the H2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie programme [No. 839483 MOBILISE]; Any dissemination of results reflects only the authors’ view and the Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. We thank Camila Arza, Marco Giugni, Katja Hujo and Luis Vargas Faulbaum and Gian-Andrea Monsch for their comments on previous versions of this article, and we are also grateful to David Altman and Rossana Castiglioni for sharing their data on electoral competition with us. We also acknowledge the useful comments received on an earlier version of this paper by participants at the ISA Forum of Sociology (February 23-28, 2021) and research seminars at the Scuola Normale Superiore, the University of Oxford and the University of Geneva. Finally, we thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Social Policy.

Competing interests

The authors Rossella Ciccia and Cesar Guzman-Concha declare none.