The expanding operations of finance-controlled providers in Nordic eldercare

Market-inspired reforms seeking cost savings and quality improvements have deeply transformed the provision of eldercare services in public sectors throughout Europe. This transformation is perhaps particularly noticeable in the Nordic welfare states, where three decades of recurring reforms have blended traditional public-sector governance principles – emphasising standardisation and universalisation – with novel private-sector management models – stressing customisation and individualisation (Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013; Moberg, Reference Moberg2017).

Various features of these market-inspired reforms have attracted considerable attention from scholars in Sweden, Norway, Finland and Denmark, regarding, for example, how users are framed as customers (Askheim et al., Reference Askheim, Christensen, Fluge and Guldvik2017), how private providers create domicile services and nursing homes with particular profiles (Edlund and Lövgren, Reference Edlund and Lövgren2022)Footnote 1 and how support for choice and competition in publicly funded eldercare persists among most politicians (Stolt and Winblad, Reference Stolt and Winblad2009), although there is no firm evidence pointing to cost savings and quality improvements (Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013). While such market-inspired features have garnered much interest from Nordic scholars, surveys suggest for-profit providers controlled by financial entities generate the biggest concerns among Nordic citizens when queried about their perceptions of eldercare (Svallfors and Tyllström, Reference Svallfors and Tyllström2019).Footnote 2 Finance-controlled providers (FCPs) engender concerns because these providers bring the opaque and elusive dynamics of financialisation – including debt-based mergers, tax-planning schemes and other finance-based business tools – into national eldercare contexts (Hoppania et al., Reference Hoppania, Karsio, Näre, Vaittinen and Zechner2024).

Despite concerns among Nordic citizens about FCPs in publicly funded eldercare, such providers have received little attention from Nordic scholars to date. Extant literature primarily comes from English-speaking countries (e.g. Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2022; Kamimura et al., Reference Kamimura, Banaszak-Holl, Berta, Baum, Weigelt and Mitchell2007; Mercille and O’Neill, Reference Mercille and O’Neill2024), where FCPs have commanded an established presence for several decades. For example, US eldercare has been dominated by FCPs since the early 2000s. And more than 35 per cent of certain UK eldercare services were delivered by FCPs during the mid-2010s (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017). This literature highlights how FCPs have expanded their operations through finance-based business tools that require high investment returns, suggesting the financialisation of eldercare has become an international phenomenon with significant implications. In the Nordic countries, however, FCPs largely remain a novelty. Nordic literature on FCPs has shown that successive reforms slowly opened Finnish eldercare, rendering lucrative conditions for such providers to begin launching operations (Hoppania et al., Reference Hoppania, Karsio, Näre, Vaittinen and Zechner2024). Other Nordic literature has highlighted how private providers in Swedish eldercare – several of them FCPs – initially launched their domicile services and nursing homes across urban areas governed by right-wing political majorities that welcomed these providers throughout the mid-2000s (Stolt and Winblad, Reference Stolt and Winblad2009). Nowadays, Sweden stands out. Whereas FCPs also operate in Danish, Finnish and Norwegian eldercare, their operations are currently larger in Swedish eldercare than anywhere else throughout the Nordic countries. FCPs thus managed 16 per cent of all nursing home beds (and 74 per cent of all beds managed by private providers) in Sweden during 2023.Footnote 3 Such extensive operations in Swedish eldercare may seem paradoxical, considering that FCPs performed worse than other private providers on various service quality parameters throughout the 2010s (Broms et al., Reference Broms, Dahlström and Nistotskaya2024).

With multiple FCPs presently operating in urban areas, it is now a pertinent time to begin redirecting our attention towards how these providers are further expanding their operations throughout Swedish eldercare – a national context that has been characterised by an ‘astonishingly fast growth of for-profit providers’ (Svallfors and Tyllström, Reference Svallfors and Tyllström2019, p. 746). Centring on nursing homes as a specific segment, our aim throughout this paper is to develop new knowledge about the expansion strategies guiding FCPs in Sweden. We ask: How do FCPs integrate their perceptions of opportunities and challenges into strategies for expansion? And what do these strategies imply for FCPs and other eldercare actors? To address our aim, we approach FCPs as actors situated within a social field (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1985; Bourdieu and Wacquant, Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992) and explore their expansion strategies through an abductive study consisting of 379 documents (7,148 pages) focusing on the three largest FCPs that operated nursing homes in Swedish eldercare between 2015 and 2023: Attendo, Vardaga and Humana. Our focus lies on these three FCPs because they have achieved a significant presence; together, Attendo, Vardaga and Humana managed 58 percent of all nursing home beds managed by private providers throughout Sweden during 2023.Footnote 4 In situating three major FCPs within an eldercare field, we recognise they are affected by norms, values and beliefs as well as by other actors – including users, regulators, politicians, public providers and property developers – that both enable Attendo, Vardaga and Humana to expand their operations and constrain their agency when it comes to expansion of their operations. But in situating our three focal FCPs within a field, we also recognise their significant presence is key to the emergence of norms, values and beliefs that affect other actors.

Our findings indicate FCPs in the Swedish eldercare field sensed ‘booming opportunities’ for expansion fuelled by demographic trends among older citizens and economic difficulties within municipalities. However, FCPs also perceived ‘looming challenges’ deriving from labour shortages and latent debates about profits in the public sector that made it a complex endeavour to leverage demographic trends and economic difficulties as business possibilities. FCPs sought to handle the perceived expansion challenges through strategies centred on acquiring eldercare providers for their valuable competencies, and – most notably – on building nursing homes that could provide stability amidst shifting political conditions. We discuss such strategies in terms of expanding operations and expanding positions, stressing that FCPs strove to become eldercare providers as well as nursing home builders and welfare policy actors influencing the legal frameworks through which public-sector services were outsourced and delivered. Our findings contribute to recent conversations about FCPs in the Journal of Social Policy (e.g. Hoppania et al., Reference Hoppania, Karsio, Näre, Vaittinen and Zechner2024; Mercille and O’Neill, Reference Mercille and O’Neill2024) by highlighting how not only business tools but also field perceptions are incorporated into expansion strategies that guide these providers as they develop their operations and positions throughout Nordic welfare states. We suggest our contributions ultimately shed light on the ways that a distinct and controversial type of for-profit providers may grow powerful in welfare states transformed by market-inspired reforms.

A field perspective to the expansion of finance-controlled providers in Sweden

To approach change and inertia in empirical contexts, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1985; Bourdieu and Wacquant, Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992) used the notion of fields. Bourdieu conceptualised fields as social spaces where actors connected by different – yet largely interdependent – interests command specific positions deriving from various material and immaterial assets. Such positions, in turn, affect the opportunities and challenges that actors perceive as salient throughout fields.

However, the field-specific positions of actors affect not only their own perceptions; these positions also affect whether some actors can influence what other actors perceive as salient. The influence associated with certain positions in fields implies some actors are keen on sustaining their positions, while other actors are keen on improving their positions. Perhaps not surprisingly, tensions in fields often revolve around actors attempting to improve their positions among actors attempting to sustain their positions. Although actors may exercise agency to sustain or improve their positions, this agency is filtered through and moderated by field-specific logics. Such logics comprise the norms, values and beliefs that together yield frameworks guiding actors in specific fields. Field-specific logics are not deterministic, but they condition what operations actors see as worthy or unworthy of pursuing (see also Swartz, Reference Swartz1997).

In devising a field perspective, we highlight how Swedish eldercare – despite its far-reaching ‘marketization’ (c.f. Moberg, Reference Moberg2017) – features social dynamics that contrast with the supply-and-demand transactions permeating markets. Whereas fields can direct our attention to the positions of various economic and non-economic actors operating in eldercare, and how they affect one another from and through their positions, markets would largely restrict our attention to the transactions of economic actors. By leveraging a field perspective, we also highlight how eldercare in Sweden displays social dynamics that differ from the information-centred ties characterising networks. Fields can broaden our view to incorporate political and regulatory dimensions that influence actors beyond the ties through which specific information flows (c.f. Fligstein and McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2010). Using Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of fields as a perspective to ‘look at, grasp, and represent’ (Abend, Reference Abend2008, p. 179) phenomena, we thus approach FCPs as economic actors that – considering recent concerns among Nordic citizens about these for-profit providers (Svallfors and Tyllström, Reference Svallfors and Tyllström2019) – would be keen on improving their positions among other economic and non-economic actors populating the Swedish eldercare field. This field traditionally revolved around a public-sector logic of standardisation and universalisation that placed responsibility on nation-level states for providing equal services to older citizens. However, such standardisation and universalisation has, since the late 1980s, gradually meshed with a private-sector logic of customisation and individualisation, fuelled by market-inspired ideas emphasising choice and competition (Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013; Moberg, Reference Moberg2017).

To understand how these logics have meshed, and how their meshing affects what opportunities and challenges FCPs perceive for expansion in Sweden’s eldercare field, we focus on three closely connected reforms that became an historical inflection point during the 1990s. In 1991, a wide-ranging Local Government Act transferred most responsibility for public sector services from the Swedish state to Sweden’s 290 newly created municipalities. Moreover, in 1992, an Elderly Reform Statute developed parts of the Local Government Act to make municipalities responsible for all eldercare services. Finally, also in 1992, an Act on Public Procurement – commonly labelled the ‘LOU’ law for its Swedish initials – introduced tender procedures through which municipalities could purchase certain services – including eldercare – by contracting them to public and private providers on quality and efficiency grounds. In eldercare, contracts included occupancy guarantees, and providers were required to utilise existing municipal buildings throughout the delivery of services. These three reforms can be understood as coordinated organising efforts by regulators and politicians in Sweden’s eldercare field to construct local markets. In such markets, public and private providers could compete for multi-year service contracts from municipalities, and users would choose among contracted providers (Edlund and Lövgren, Reference Edlund and Lövgren2022).

Efforts such as these generated shifts among actors and positions in the field. By 1993, four municipalities in the greater Stockholm area were already contracting eldercare services to private providers. A year later, 10 per cent of Swedish municipalities did so (Svensson and Edebalk, Reference Svensson and Edebalk2006). Throughout the 1990s, a growing number of municipalities implemented tender procedures, often as bases for purchaser–provider systems. By the mid-2000s, such procedures had been implemented in 80 per cent of Sweden’s municipalities, although many only allowed contracting to public providers (Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013). Further organising efforts to enhance the creation of local markets soon followed, and a fourth reform became an additional inflection point.

In 2009, an Act on System of Choice in the Public Sector – popularly labelled the ‘LOV’ law – allowed municipalities to receive and accept service offers from public and private providers. The LOV law featured two important novelties that differentiated it from the LOU law. One novelty was that the LOV law did not feature tender procedures. Providers could submit offers whenever, and Swedish municipalities decided whether the offered services were needed. As for eldercare, another novelty was that the LOV law did not include occupancy guarantees nor requirements to utilise municipal buildings when delivering services. Providers with accepted offers were responsible for attracting all users, recruiting all employees and preparing all necessary buildings (Moberg, Reference Moberg2017).

Positions in the field had now shifted considerably. By 2015, public and private eldercare providers operated – through the LOU and LOV laws – alongside one another in almost half of Sweden’s 290 municipalities. While private providers offering domicile-based eldercare services had multiplied exponentially across Sweden since 1992, the range of private providers offering nursing-home-based services was, by 2015, highly concentrated to a few for-profit providers operating in urban areas (Jönson and Szebehely, Reference Jönson and Szebehely2018). Such concentration took form as various financial entities drew on the LOV law to develop their previous engagements in Swedish eldercare. Few private providers other than for-profits controlled by financial entities – such as private equity firms or private investment companies – could rapidly muster all resources required to offer nursing-home-based services on any significant scale (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017). Tellingly, Sweden’s three largest private providers per number of managed nursing homes and nursing home beds in 2023 – Attendo (98 homes; 5,597 beds), Vardaga (105 homes; 5,702 beds) and Humana (22 homes; 1,237 beds) – were controlled by private equity firms between the mid-2000s and mid-2010s, and are now controlled by private investment companies.4 We turn our empirical attention to an exploration of the perceived opportunities and challenges for further expansion that these three FCPs expressed through their strategies.

A study of expansion strategies among finance-controlled providers

In addressing our aim, we designed an explorative study concentrating on Attendo, Vardaga and Humana during the 2015–2023 period. This period is aligned with our focus on recent expansion strategies guiding FCPs that have begun venturing beyond urban areas. This period also denotes time when the LOV law had been running in Swedish eldercare for several years.

Delimiting our study to 2015–2023, we searched for textual data within which Attendo, Vardaga and Humana not only outlined their expansion strategies but also justified their strategies by explaining the opportunities and challenges for expansion that were perceived in Sweden’s eldercare field. Textual data from documents offered concrete sources through which we could identify how Attendo, Vardaga and Humana sought to position themselves against other field actors when the focal documents were authored. Documents thus made it possible to circumvent certain shortcomings that can surface in verbal data sources, including retrospective biases deriving from interviews with field actors (c.f. Vaughan, Reference Vaughan2008).

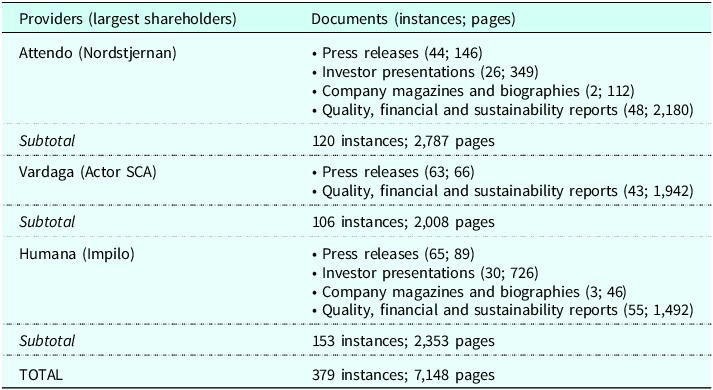

Using Retriever Research’s Mediearkivet – a digital archive featuring Nordic media content – and Bolagsinfo – a digital archive featuring Nordic business information – we located and collected documents that included press releases, website updates, investor presentations, company magazines and biographies as well as quality, financial and sustainability reports issued by Attendo, Vardaga and Humana (Table 1). Through Mediearkivet and Bolagsinfo, we also located and collected relevant documents issued by three private investment companies that became the largest shareholders in Attendo (i.e. Nordstjernan), Vardaga (i.e. Actor SCA) and Humana (i.e. Impilo) after these FCPs were transformed from non-traded to traded limited liability businesses (Table 1; see endnote 5). Our textual data amount to 379 documents (7,148 pages) in total (Table 1). We gathered these data as part of a research project that has received approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

Table 1. Data overview

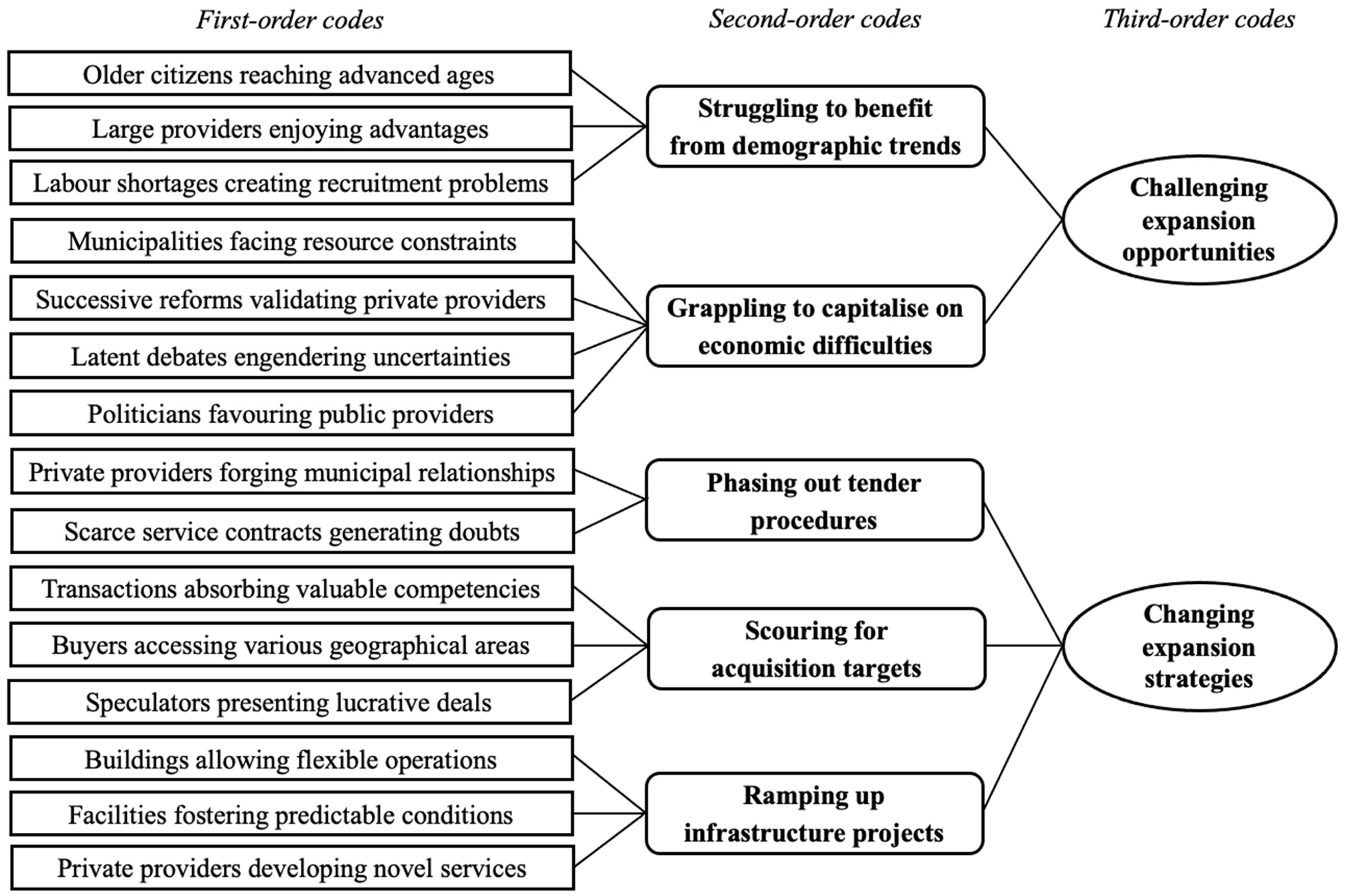

We deployed an abductive analysis procedure (Tavory and Timmermans, Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014) – consisting of repeated iterations between theories (i.e. a field perspective) and empirics (i.e. our document data) – to discern recurring themes at different abstraction levels. This analysis followed three steps inspired by Gioia et al.’s (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) well-known technique for coding qualitative data, such as documents.

First, we engaged in open exploration to spot terms, sentences and paragraphs associated with the strategies for expansion formulated by Attendo, Vardaga and Humana. This step rendered numerous first-order codes reflecting field perceptions underlying expansion strategies (e.g. ‘Labour shortages creating recruitment problems’) (Figure 1). Second, we relied on constant contrasting to detect related and/or overlapping themes. This step involved merging first-order codes into a reduced number of second-order codes that reflected how FCPs as field actors attempted to improve their positions (e.g. ‘Struggling to benefit from demographic trends’) (Figure 1). Finally, we engaged in further contrasting to delineate overarching themes running through our data. This step ultimately included abstracting second-order codes into third-order codes (e.g. ‘Challenging expansion opportunities’) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Coding structure.

Opportunities, challenges and strategies for finance-controlled expansion

A key tenet of entrepreneurship is that certain actors sense business possibilities when and where other actors see few or no opportunities (and mostly or only challenges) (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1961 [1934]). This tenet was highly palpable as we analysed how FCPs attempted to expand their operations in the Swedish eldercare field. For instance, despite being one of Sweden’s largest eldercare providers, Attendo sought to project an entrepreneurial aura, suggesting that, ‘where others see barriers and problems, the entrepreneur sees possibilities and visions’ (Attendo; 2015 corporate biography [CR]). FCPs generally sensed two expansion opportunities in a field within which other actors mostly sensed resource shortcomings and subsistence problems for Swedish eldercare. These two opportunities were challenging in many aspects, however, making expansion a complex endeavour to strategise.

Struggling to benefit from demographic trends

One of the most salient expansion opportunities perceived by FCPs concerned demographic trends suggesting older citizens in Sweden are increasingly reaching advanced ages – what Attendo called an ‘elderly boom’ (Attendo; 2021 quarterly report [QR]). Such trends were approached as beneficial developments that could generate a steady inflow of users for many years to the nursing homes managed by FCPs. This approach to demographic trends was, for example, stressed by Vardaga:

During the upcoming decade, the age group 80+ will increase by approximately 50 percent in Scandinavia, at the same time as the population in general will increase by approximately six percent. This will demand further nursing home beds… In this task, Vardaga has an important role to play (Vardaga/Ambea; 2020 annual report [AR]).Footnote 5

A similar approach was noticeable when Humana mentioned that it ‘plans for continued growth… as the number of persons aged above 80 will increase by approximately 50 percent during the upcoming ten years’ (Humana; 2022 AR).

FCPs believed they could benefit from demographic trends by drawing on competitive advantages associated with the positions of large eldercare providers. These advantages were grounded in the scale and scope of material and immaterial assets amassed through operations in Sweden’s eldercare field over considerable time periods. FCPs understood such assets as grounds for competitive advantages that small providers were hardly able to access or imitate in a foreseeable future (c.f. Barney, Reference Barney1991). Attendo’s following statement highlights the advantages commanded by – and, thus, the expansion opportunities accruing to – large providers:

Through our breadth and size, we have a unique stock of experiences to provide appreciated care services, and we will become even better in making users and relatives appreciate our services regardless of where they live (Attendo; 2022a press release [PR]).

Although demographic trends were seen as important opportunities, FCPs struggled to benefit from these trends. As with most – if not all – public and private providers, FCPs grappled with labour shortages that generated recruitment problems throughout Sweden’s eldercare field. Owing to pension retirements and expanded operations, FCPs predicted that massive numbers of new nurses and nursing assistants would be needed before the early 2030s. ‘Care consists of meetings between persons, so it is people-intensive by nature. Already today, there is a shortage of staff on many sites and within certain professions’ (Attendo; 2021 AR). Yet ‘finding and retaining skilled personnel is a decisive factor…to continue growing and providing good care’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2022 AR). FCPs thus expended considerable energy on framing themselves as attractive employers, regularly pointing to not only career development possibilities but also prizes, certificates and survey results that portrayed these providers as worthy actors in the Swedish eldercare field.

Grappling to capitalise on economic difficulties

Another salient expansion opportunity perceived by FCPs included the economic difficulties many municipalities in Sweden were allegedly facing. Such difficulties are not new; resource constraints in the public sector have been a major driver behind three decades of market-inspired reforms (Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013; Moberg, Reference Moberg2017). FCPs sensed how significant economic difficulties converged with sweeping demographic trends to affect the Swedish eldercare field in ways that generated and reinforced an almost continuous need for additional nursing home beds. Noticing this need, FCPs claimed they stood prepared to alleviate the lack of beds through high-quality and low-cost services. As such, Attendo emphasised that:

Many purchasers [e.g. municipalities] across the Nordics are struggling with weak economic conditions, making it very difficult to reach the investments that will be needed. The conclusion is that, if we in the future want to be able to afford care of high quality, private alternatives must be allowed to contribute… Attendo pushes systematic improvement efforts throughout all its divisions, with an aim to offer care of high quality, but to a lower cost for the purchaser (Attendo; 2017 AR).

FCPs sensed their positions were comparatively propitious to leverage the economic difficulties of municipalities. Reaching the late 2010s, FCPs perceived they had been validated by successive reforms that continued to profess political support for private providers in Swedish eldercare. There was a ‘favourable climate for private alternatives’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2018 AR), and ‘the right to choose and leave providers has become well established among Swedish citizens’ (Humana; 2018 AR).

Despite perceiving an important expansion opportunity in the economic difficulties of municipalities, FCPs grappled to capitalise on it. They approached successive reforms as signals of continued political support for private providers, but profit-making nonetheless remained unworthy among many other actors in publicly funded eldercare (Svallfors and Tyllström, Reference Svallfors and Tyllström2019). Most notably, for-profit providers conflicted with a public-sector logic of standardisation and universalisation that still permeated the eldercare field (Moberg, Reference Moberg2017). FCPs thus regarded debates from the early and mid-2010s about limiting or prohibiting profit-making as latent debates that could resurface. Debates such as these generated uncertainties that FCPs approached as ‘political risks’ (Humana; 2016 QR). Such uncertainties are described in relation to profit-making through Humana’s statement below:

Some political parties in the Nordic countries still question the privatisation of care services and work for limitations in the possibility to operate private companies with profit…If legal requirements were introduced to prohibit or only allow limited profits,…the business model for private care companies could be negatively affected (Humana; 2019 AR).

These shifting political conditions transformed profit-making from the economic difficulties of municipalities into a complicated expansion opportunity. FCPs perceived this opportunity was further complicated by a recurring notion that regulators and politicians unjustly favoured public providers over private providers in the Swedish eldercare field. Public providers supposedly received larger reimbursements for nursing-home-based services than private providers. And public providers could – in contrast to private providers – allegedly present repeated financial deficits without being shut down. FCPs claimed the ‘high demands placed on privately performed care are not being similarly placed on publicly performed care’, even though Sweden’s government has allegedly ‘declared an intention to strive towards more equal conditions between [public and private] providers’ (Attendo; 2019 AR). Such dissimilar demands and unequal conditions amounted to what FCPs regarded as unfair competition. This supposed unfairness was exacerbated by beliefs that regulators and politicians approached failure and misconduct among public providers in a more lenient manner than among private providers.

FCPs ultimately incorporated their field perceptions of opportunities associated with demographic trends and economic difficulties into expansion strategies that oriented these providers. The formulated strategies typically comprised three simultaneous ways through which FCPs intended to expand their operations beyond urban areas. In comprising three simultaneous ways to expand operations, the strategies also comprised three simultaneous ways to spread risks. Owing to shifting conditions, however, FCPs begun changing their strategies towards the late 2010s and early 2020s, placing increasing weight on certain ways of expanding operations.

Phasing out tender procedures

One way of expanding operations was to compete for service contracts through tender procedures within the LOU law (Edlund and Lövgren, Reference Edlund and Lövgren2022). That said, such expansion only played a peripheral role in the strategies of FCPs. Admittedly, ‘contracting [through tender procedures] contributes to developing relationships with municipalities that Vardaga has not previously been in contact with’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2021 AR). And competing for further service contracts could also help reinforce relationships with municipalities where FCPs had previously been present (Edlund and Lövgren, Reference Edlund and Lövgren2022). But the role played by tender procedures in the expansion strategies of FCPs was clearly waning. The main reason for this waning was a shrinking supply and worrying scarcity of service contracts. A ‘clear market trend is that the number of care operations conducted through contracting has decreased’ (Humana; 2015 AR), and ‘the volume of contracting will continue to show a negative development in the future’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2017 AR).

This development created doubts among FCPs about the viability of tender procedures as an expansion strategy. Competing for service contracts was seen as an increasingly unviable way of expanding operations in the field. FCPs were thus phasing out this strategy. Over and above tender procedures, FCPs instead focused their strategies on two other ways of expanding operations that were largely fuelled by Sweden’s LOV law.

Scouring for acquisition targets

Seeking acquisition targets was one way of expanding operations that had typically played an important role for FCPs (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017). Between 2015 and 2023, Attendo, Vardaga and Humana acquired numerous domicile-based eldercare providers in Sweden’s eldercare field. Attendo also acquired three nursing-home-based providers, while Vardaga acquired two. Scouring for providers to buy, FCPs expended considerable energy on framing themselves as appealing acquirers. Attendo, for instance, stressed it was ‘an attractive partner for entrepreneurs who want to transfer their companies’ (Attendo; 2016 PR). Most successful ‘transfers’ concerned acquisitions of small, promising and entrepreneurial providers that managed a few nursing homes. Such acquisitions allowed FCPs to grow gradually. FCPs seldom grew exponentially through acquisitions. An exception was Vardaga’s ‘dreamlike acquisition’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2018 AR) of the nursing-home-based provider Aleris Care in 2018. This single acquisition amalgamated Aleris Care’s twenty-eight nursing homes into Vardaga’s operations, allowing the latter to grow exponentially.

Acquisitions were partly driven by a desire to absorb valuable competencies. In a representative statement of this desire to absorb competencies – whether it be through acquisitions generating gradual or exponential growth – Vardaga emphasised that:

The transaction [with Aleris Care] facilitates an exchange of experiences involving operations and quality development. Ambea and former Aleris Care complement each other…There are significant possibilities to lay the basis for even higher quality through collaboration, and this will, by extension, imply higher profitability in our operations (Vardaga/Ambea; 2018 AR).

Acquisitions were also driven by a desire to access geographical areas where FCPs currently commanded weak positions. While FCPs in Swedish eldercare had initially launched their operations throughout urban areas – and presently commanded strong positions there – FCPs had additionally commenced to acquire private providers operating beyond Sweden’s metropolitan regions. Attendo’s following quote shows how acquisitions were perceived as transactions that could deepen the existing operations of FCPs in areas where these providers currently commanded weak positions:

The [acquired] company was present throughout all of Sweden, but was particularly strong in Northern and Western Sweden – areas where Attendo was not as well established as in other parts of the country…On the one hand, Attendo could get help to enter municipalities where it was not traditionally strong…It was important for Attendo to not only be a Stockholm-based company (Attendo; 2015 CR).

On rare occasions, acquisitions afforded leaps into geographical areas where FCPs previously counted with no presence. Such acquisitions were preceded by particularly extensive evaluations of political and demographic conditions in attempts to forecast future eldercare developments.

That said, regardless of whether acquisitions expedited access to areas where FCPs had been present or absent before, acquisitions constituted an attractive expansion strategy for these providers. A mounting complication in realising this strategy was, however, that few private providers remained as potential acquisition targets. By the late 2010s and early 2020s, most attractive providers had already been acquired. FCPs thus acted as avid speculators, advancing lucrative deals to the few remaining providers that had not been acquired.

Ramping up infrastructure projects

Considering most attractive providers had already been acquired, FCPs gradually turned their expansion strategies towards infrastructure projects through which new nursing homes were built. Perhaps sensing a lowered number of tender procedures and acquisition targets ahead, FCPs ramped up their infrastructure projects during the mid-2010s (see Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017, as well). Previously uncommon, such projects soon played a central role for the expansion strategies of FCPs in Swedish eldercare. Humana, for example, mentioned that it looks for tender procedures and acquisition targets, but that it ‘primarily invests in own-operated homes’ (Humana; 2016 AR). Originally used by public providers, the notion of ‘own-operated homes’ had subsequently been adopted by FCPs. For FCPs, own-operated homes denoted nursing homes built as private facilities, often owned by property developers but managed by private eldercare providers. Between 2015 and 2023, Attendo built thirty-seven homes (2,511 beds), Vardaga twenty-nine homes (1,877 beds) and Humana twelve homes (829 beds). These homes were offered to municipalities in what constituted one of Humana’s core ‘value creation levers’ (Humana/Impilo; 2021 AR) and Attendo’s ‘single most important future growth stream’ (Attendo; 2015 CR). Similarly signalling the importance of own-operated homes, Vardaga recounted how:

During 2018, the board’s work has largely focused on Vardaga’s expansion strategy. After suggestions from the expansion division, the board decided to start the construction of nine new own-operated nursing homes, which is our biggest number this far (Vardaga/Ambea; 2018 AR).

The infrastructure projects of FCPs were regularly fuelled by a perception that private buildings allowed flexible operations. This perception was stressed by Vardaga in the statement below:

Vardaga’s strategic focus is to increase the share of own-operations, as this contract form gives more…flexibility. Here, we can use our own care concepts and our steering system, which improves quality and efficiency and, thus, contributes to increased profitability (Vardaga/Ambea; 2019 AR).

Flexible nursing homes highlight how a private-sector logic of customisation and individualisation physically was expressed in infrastructure projects throughout Sweden’s eldercare field. Nonetheless, flexibility could be differently understood by FCPs and property developers when they collaborated to build nursing homes. The narrower understanding of FCPs indicated they desired buildings that were flexible for various eldercare services. The broader understanding of property developers instead suggested they desired buildings that were flexible for various business possibilities – including eldercare as well as education and hospitality (see also Horton, Reference Horton2021). These different understandings of flexibility implied that FCPs typically had to negotiate compromises with property developers.

In addition, the infrastructure projects of FCPs were regularly fuelled by a perception that private buildings fostered predictable conditions. Attendo underscored the predictability afforded by private buildings during shifting political conditions in Sweden:

By owning buildings, Attendo becomes less dependent on political decisions about what services will and will not be tendered out – something that has varied considerably throughout the years and implied that our operations have been difficult to plan in a longer term (Attendo; 2015 CR)Footnote 6 .

FCPs thus hoped they could gain predictability by building nursing homes. Instead of reactively competing in tender procedures through the LOU law, FCPs built nursing homes to proactively submit service offers through the LOV law. FCPs ultimately hoped to gain the predictability that came from signing long-term service contracts with municipalities before building nursing homes.Footnote 7

Contracts signed through the LOU law warranted four to five years of operations (and two to four years of potential extensions) with occupancy guarantees in nursing homes managed by FCPs yet owned and largely steered by municipalities. Contracts signed through the LOV law instead warranted ten to fifteen years of operations without occupancy guarantees in nursing homes owned by property developers yet managed and largely steered by FCPs. Extensions and guarantees were occasionally granted to FCPs through the LOV law. For instance, Humana publicised that it ‘recently signed a 20-year contract in [the municipality of] Strängnäs with guaranteed occupancy’ (Humana; 2022 AR). However, FCPs increasingly sought extensions and guarantees from municipalities to compensate for the ‘considerable economic investments implied in [building] new nursing homes’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2020 AR), and for the ‘negative impact on revenues [such homes generate], as occupancy is initially low’ (Attendo; 2017 QR).

Drawing on experience from past infrastructure projects and long-term contracts, FCPs had as of late commenced expanding their positions throughout the Swedish eldercare field by creating novel service offerings, most notably encompassing consultancy in building, managing and steering nursing homes. Vardaga, for example, offered consultancy packaged as a ‘process for new establishments…’, geared towards ‘the average municipality that does not build more than a few new homes’ (Vardaga/Ambea; 2020 AR). And Attendo offered consultancy ranging ‘from the identification of sites, construction companies, and investors, to employee recruitment, launch, and opening of homes’ (Attendo; 2020 AR). Such consultancy offers demonstrated the widening influence of FCPs throughout Sweden’s eldercare field.

The expanding positions of finance-controlled providers in Swedish eldercare

Throughout this paper, our aim has been to develop new knowledge about the expansion strategies guiding FCPs in Sweden. Mobilising a Bourdieusian field perspective, we showed how the three largest FCPs in Swedish eldercare services perceived significant opportunities for expansion following from demographic trends among older citizens and economic difficulties within municipalities. But labour shortages and latent profit debates in the eldercare field meant that FCPs faced considerable challenges when it came to realising demographic trends and economic difficulties as business possibilities. Attempting to fulfil these possibilities, FCPs formulated expansion strategies centred on accessing valuable competencies by acquiring eldercare providers, and – most importantly – on creating predictable business conditions by devising infrastructure projects that consisted of building nursing homes.

Previous literature focusing on FCPs in Nordic eldercare has shown how national contexts were gradually opened for these providers through a string of reforms fuelled by market-inspired ideas (Hoppania et al., Reference Hoppania, Karsio, Näre, Vaittinen and Zechner2024). Other Nordic literature has shown the ways that private providers – among them, FCPs – initially launched their eldercare operations in metropolitan regions (Stolt and Winblad, Reference Stolt and Winblad2009). We contribute to the literature on FCPs in Nordic eldercare by highlighting how they incorporate field perceptions into expansion strategies that orient these providers as they seek to further extend their operations throughout national contexts. By attending to field perceptions, our paper additionally extends the literature on eldercare FCPs in English-speaking countries (Corlet Walker et al., Reference Corlet Walker, Druckman and Jackson2022; Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017; Kamimura et al., Reference Kamimura, Banaszak-Holl, Berta, Baum, Weigelt and Mitchell2007; Mercille and O’Neill, Reference Mercille and O’Neill2024), where researchers have demonstrated how finance-based business tools are incorporated into expansion strategies. However, in highlighting acquisition targets and infrastructure projects as key strategy dimensions, we point not only to the expanding operations of FCPs but also to their expanding positions. This dual expansion in terms of operations and positions holds important insights and implications for eldercare fields across the Nordic countries and beyond.

In our study, acquisition targets and infrastructure projects as key components suggest FCPs attempted to expand their operations following Porter’s (Reference Porter1979) classic strategy notion of horizontal integration (i.e. when buying private providers) and vertical integration (i.e. when building nursing homes). Although successive reforms had already fuelled outsourcing decisions through governmental and municipal organising efforts to construct local eldercare markets, recent horizontal and vertical integration indicates FCPs believed such outsourcing would continue. Vertical integration was most prevalent in our study, and through this integration, FCPs increasingly managed the delivery of eldercare services in nursing homes these providers built together with property developers. Summing recent horizontal and vertical integration, FCPs have become sizeable actors in the Swedish eldercare field, managing 16 per cent of all nursing home beds (and 74 per cent of all beds outsourced to private providers) during 2023.

The increasing tendency of FCPs to integrate vertically by building nursing homes is a clear example that highlights how these providers have expanded their positions. Driven by dual desires to achieve flexibility and predictability, FCPs acted not only as service providers but also as builders of nursing homes through which eldercare services were provided. Such expanding positions have been supported by three decades of market-inspired reforms that attest to a far-reaching development when private providers regularly offered both services and buildings. Certain findings in our study suggest FCPs have continued to expand their positions throughout Sweden’s eldercare field. These findings indicate FCPs also acted as consultants offering expertise in the building and management of nursing homes. Acting as builders, providers and consultants, FCPs thus became full-range, start-to-finish, upstream-and-downstream actors offering what could be described along the lines of ‘complete eldercare solutions’.

Contracting such actors can be alluring for Swedish municipalities possessing scant and sporadic experience of building and managing nursing homes. But contracting FCPs as builders, providers and consultants can also make municipalities dependent on these private actors. ‘The more facilities built by private companies’, as Harrington et al. (Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017, p. 12) succinctly put it, ‘the more dependent the municipalities are on their contribution’. We know from Pfeffer and Salancik’s (Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978) resource dependence theory that both material assets (e.g. nursing homes) and immaterial assets (e.g. expertise in building and managing nursing homes) constitute powerful bases for the establishment of dependency relationships among organisations. With FCPs contracted as builders, providers and consultants in municipalities, an increasing proportion of material and immaterial assets is shifting hands from public actors to private actors, potentially locking municipalities into dependency relationships. Thinking along the lines of Pfeffer and Salancik, we can, by extension, approach the establishment of dependency relationships as a strategy through which certain organisations (e.g. FCPs) attempt to ain influence over other organisations (e.g. municipalities).

It is important to note that the expanding positions of FCPs have developed in tandem with – and, thus, been reinforced by – the retracting positions of public providers throughout Sweden’s eldercare field. Public providers have, as of late, focused on empowering users – and responsibilising them for their own care – to a much larger degree than before. This focus on empowerment and responsibility is one way to cope with the deficient supply of nursing homes generated by economic difficulties in municipalities (Hoppania et al., Reference Hoppania, Karsio, Näre, Vaittinen and Zechner2024). We showed that FCPs perceive the economic difficulties of municipalities as opportunities for expansion, albeit it remains unclear how this expansion will unfold if public funds are running short. Augmenting the efficiency of resource utilisation – which FCPs already claim they do through their operations – may not be enough over time.

We have this far implicitly discussed FCPs as actors expanding their positions to become builders, providers and consultants within a mesh of public- and private-sector logics in the Swedish eldercare field. Yet, FCPs are also seeking to affect these logics, fretting about uncertain political conditions generated by past debates and present concerns revolving around profit-making in publicly funded eldercare. Focusing on political conditions, Jobér (Reference Jobér2024) proposed the term ‘policyneurs’ when stressing how certain private providers of public services identify and exploit opportunities to affect policy in ways that benefit those providers. Policyneurs can be understood as actors exercising agency to affect the norms, values and beliefs that underlie logics in fields, ultimately aiming for improved positions. The expanding positions of FCPs in Sweden nonetheless raise important mandate and accountability questions that should not be ignored as private actors increasingly take on functions traditionally reserved for and assumed by public actors.

In this paper, we focused on expansion strategies. Recent organising efforts among Swedish municipalities nonetheless seek to revoke certain market-inspired reforms by restricting what has become a key expansion strategy component for FCPs: building nursing homes (e.g. Smedberg et al., Reference Smedberg, Eskilsson, Hanna and Pelling2024). Such efforts constitute an interesting avenue for future research on FCPs. How will they respond to the organising efforts of municipalities? And what do these responses imply for the expanding operations and positions of FCPs? We specifically focused on national expansion strategies; another interesting future research avenue thus concerns the international expansion strategies of FCPs. The three largest FCPs in Sweden’s eldercare field have already expanded internationally to Norway, Finland and Denmark. Such internationalisation has evidently required expanding operations and positions to new fields, albeit the logics of Danish, Finnish and Norwegian eldercare resemble those of Swedish eldercare (c.f. Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Jacobsen, Panos, Pollock, Sutaria and Szebehely2017; Meagher and Szebehely, Reference Meagher and Szebehely2013). Attendo’s goal to become the largest private provider of eldercare services in Europe by 2025 is particularly ambitious, however. Realising this goal will presumably require expanding to new fields featuring different logics than Sweden’s eldercare field. What strategies guide FCPs as they attempt to expand their operations and positions internationally? And how do these strategies overlap with and/or depart from those guiding FCPs as they seek to expand nationally? Last but not least, a field perspective invites scholars to engage in another interesting avenue for future research that partly stretches beyond eldercare. Scholars studying welfare state actors in a comparative light (e.g. Gingrich, Reference Gingrich2011; Goosen, Reference Goosen2024) have showed that private providers of public-sector services can influence one another across service sectors. Bourdieusian fields are useful to explore the ways that norms, values and beliefs fuelled by private providers – such as FCPs – operating in Swedish eldercare may traverse into neighbouring sectors where other private providers operate (and vice versa). How do private providers, for instance, influence one another across the eldercare and primary care sectors in Sweden? We believe our questions point to important issues meriting close attention from scholars in times when FCPs perceive ‘booming opportunities’ and ‘looming challenges’ throughout the field of Swedish eldercare and beyond.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Health Services Research Group at Uppsala University as well as our editors and reviewers at the Journal of Social Policy for helpful comments that undoubtedly improved this paper in many important ways.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.