Introduction

The debate about the introduction of a universal basic income (UBI) as a radically different conception of social policy has intensified significantly in recent years. Even almost 20 years ago, De Wispelaere and Stirton (Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004: 266) noted that UBI ‘is no longer perceived as yet another crackpot idea of the radical left’. Since then, scholarship has moved from discussing the normative foundations of UBI (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs1991, Reference Van Parijs2004) towards concrete questions of implementation and feasibility, in particular paying attention to the issue of costs and financing (Van Parijs and Vanderborght, Reference Van Parijs and Vanderborght2017; Widerquist, Reference Widerquist2017). Countries have launched experiments with variations of basic income schemes such as the widely discussed Finnish Basic Income experiment (Kangas et al., Reference Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simamainen and Ylikännö2021) or the local ‘basic income’ or ‘trust’ experiments in the Netherlands (Roosma, Reference Roosma2022).

Responding to increasing public and political interest, scholars have started to further explore public opinion regarding UBI. Even though public opinion is unlikely to be the only factor that matters with regard to the political feasibility of a UBI, it is nevertheless a ‘crucial factor’ (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 26). For so long, the analysis of public opinion towards UBI was hampered by a lack of adequate survey data. This changed dramatically when the European Social Survey (ESS) included a question on UBI in its 2016 wave, which has spawned a number of papers on public attitudes (Dermont and Weisstanner, Reference Dermont and Weisstanner2020; Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and Van Oorschot2020; Schwander and Vlandas, Reference Schwander and Vlandas2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2019, Reference Vlandas2021; see below for further details). The ESS data allow researchers to analyse public attitudes towards UBI from a cross-national, comparative perspective. A significant downside, however, is that the ESS uses a single item to measure support for UBI. Even though the particular operationalisation of a UBI in the ESS comes close to the ‘ideal-typical’ definition developed in early scholarship (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs1991, Reference Van Parijs2004) and later propagated by the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN),Footnote 1 scholars increasingly conceived of basic income as multi-dimensional (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020; De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004), exploring the variation of different types of basic income schemes across multiple dimensions (Gielens et al., Reference Gielens, Roosma and Achterberg2023). In response to this research, a string of recent papers has applied experimental survey methods to probe variations in public support for UBI schemes, depending on the particularities of policy design (see Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: chapter 3 for an excellent overview).

Our paper contributes to the latter literature by being the first to analyse public opinion towards basic income with a vignette survey design in the case of Germany, complementing similar studies for Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, Switzerland and Spain. By studying the case of Germany, we believe that our analysis can generate broader insights that are relevant beyond the concrete case for the following reasons.

In the classical comparative welfare state literature, Germany is considered a ‘conservative’ welfare state (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). A hallmark of this state model is the dominance of the ‘equivalence principle’, that is, a strong connection between the individual’s status in the labour market and their status in the social insurance system. In this context, the introduction of a UBI is likely to generate more public opposition because the notions of universalism and unconditionality are strongly at odds with the equivalence principle. In line with this thought, the ESS data show below average support for UBI in Germany, as well as in neighbouring Switzerland with a similar welfare state model (Adriaans et al., Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and Van Oorschot2020; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020). Nevertheless, there are indications that political support for basic income is growing even in the unlikely case of Germany (Heinze and Schupp, Reference Heinze and Schupp2022), also potentially because of rather strong political activism and grassroots activities (Liebermann, Reference Liebermann, Caputo and Liu2020). For example, the coalition government of social democrats, Greens and liberals (2021–2024) enacted a significant reform of the former unemployment assistance system (‘Hartz IV’), loosening conditionality requirements and renaming the transfer as ‘citizen’s income’ (Bürgergeld) in January 2023.Footnote 2 The coalition agreement also contained plans to implement a ‘basic income’ for children (Kindergrundsicherung).Footnote 3 Even though the government coalition eventually did not manage to implement this policy due to lack of funding, the example shows that notions of universality and unconditionality are gaining traction in policy-making debates in Germany. Furthermore, grassroots campaigns such as the initiative Mein Grundeinkommen (‘My basic income’) that uses crowd funding to raffle out temporary basic incomes indicate that public support for basic income amongst the population might be growing in spite of the obstacles in implementing actual policy reforms (Liebermann, Reference Liebermann, Caputo and Liu2020). Thus far, it remains unclear whether the below-average levels of support for UBI as measured in the ESS might mask latent support for basic income schemes whose design characteristics deviate to some extent from the ‘standard’ model captured in the ESS item.

Hence, to provide a short preview, the first contribution (and finding) of this paper using original survey data is to identify relatively strong latent public support for some form of basic income. However, the extent of such support crucially depends on the specific policy design characteristics of BI schemes. Somewhat different from existing research using similar vignette survey designs, we find that support for unconditional basic income schemes is significantly higher than for variants that involve conditionality, which might be due to the legacies of the unpopular ‘Hartz IV’ system that involved a high degree of conditionality. Second, we also find statistically significant interactions (i.e. heterogenous treatment effects) between support for different policy dimensions and respondent characteristics in the cases of age, ideology and income. For instance, the interaction between individual income and the generosity dimension of the vignette indicates that low-income respondents respond significantly more positively to a higher generosity of BI schemes than high-income respondents.

In the following section, we briefly review the literature on public opinion towards UBI and highlight the research gap we aim to address. In the theory section, we introduce the vignette design and develop hypotheses for our main variables of interest, followed by the empirical analysis. The concluding section reflects on the broader implications of our findings for the literature on the politics of basic income beyond the case of Germany.

Literature review

The academic literature on basic income has been moving from debates about its normative foundations (Van Parijs Reference Van Parijs1991, Reference Van Parijs2004) and economic feasibility (Widequist, Reference Widerquist2017) towards ‘questions of political feasibility and social legitimacy’ (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 218). Studies of public opinion towards UBI have become an active field of scholarship in this area. Early studies have relied on single-item research designs for particular countries or cross-national comparisons to gauge public support for the ‘ideal-typical’ version of UBI, as in the ESS. More recently, studies have started to probe the multi-dimensionality of UBI via conjoint or vignette experiments.

For the development of systematic knowledge about public attitudes on basic income, the inclusion of an item on UBI in the 2016 ESS was a crucial step forward (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020; Laenen, Reference Laenen2023). The ESS operationalisation is closely related to the ‘ideal-typical’ definition of a UBI, which, according to Laenen (Reference Laenen2023: 1), is ‘a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis, without any means test or work requirements’. Several papers have used the ESS data to explore various aspects such as individual- and country-level determinants of support for UBI (Parolin & Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2019, Reference Vlandas2021; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and Van Oorschot2020), the association between technological change and support for UBI (Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2021; Dermont and Weisstanner, Reference Dermont and Weisstanner2020) or attitudinal cleavages within the left (Schwander and Vlandas, Reference Schwander and Vlandas2020). The core findings of this literature can be summarized as follows (see also Laersen, 2023: chapter 2): First, overall support for UBI is substantial (hovering around 50 per cent), but not overwhelming, in particular in comparison with support for other social policies (Weisstanner, Reference Weisstanner2022: 101). Chrisp et al. (Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 225) also note that support for UBI is ‘extremely variable’, which may have to do with the fact that ‘public awareness of the idea of a basic income is low’. Second, individual-level support for UBI is positively associated with younger age, low income and a more precarious employment position, left-leaning ideology and support for green and liberal parties and pro-immigration attitudes, as well as higher levels of political trust. Third, regarding country-level contexts, support for UBI is generally found to be higher in countries with a generally less robust welfare state (Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021).

Further studies using survey data and a single-item operationalisation of UBI support for individual countries are largely in line with the findings from the ESS-based studies (e.g. Adriaans et al., Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019 [Germany]; Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020 [UK and Finland]; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Ferguson and Haglin2022 [USA]; Simamainen and Kangas, Reference Simamainen, Kangas, Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simamainen and Ylikännö2021 [Finland]; Weisstanner, Reference Weisstanner2022 [UK]). These and similar studies have not found evidence for a strong association between exposure to technological change (digitalisation and automation) and support for UBI, even though this connection is often discussed in the public (Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2021; Dermont and Weisstanner, Reference Dermont and Weisstanner2020). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic seems to have temporarily increased support for UBI, but did not fundamentally change the underlying political coalitional patterns (Weisstanner, Reference Weisstanner2022; see also Van Hootegem and Laenen, Reference Van Hootegem and Laenen2023).

As mentioned, the conceptual and normative debate has moved from Van Parijs’ ‘disarmingly simple’ idea of an ideal-typical UBI towards acknowledging its ‘Janus-faced’ and multi-dimensional qualities (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 219, 224; see also De Wispelaere amd Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004; Gielens et al., Reference Gielens, Roosma and Achterberg2024; Laenen, Reference Laenen2023; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020). These recent conceptual debates found resonance in empirical work that uses experimental vignette or conjoint research designs to probe the impact of design features of hypothetical basic income schemes on overall public support (see Auspurg and Hinz, Reference Auspurg, Hinz, Keuschnigg and Wolbring2015; Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020 for methodological introductions).

Conjoint/vignette designs are not regularly implemented in large cross-national surveys such as the ESS, but usually conducted by researchers themselves. As a consequence, they often generate data only for individual countries using idiosyncratic research designs, although cross-national studies are also feasible in principle (see e.g. Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020). The idiosyncratic nature of these studies somewhat restrains the potential for direct comparisons across countries, but as Laenen (Reference Laenen2023: chapter 3) demonstrates, some broad generalisations are possible. In spite of the general suitability of conjoint/vignette designs, their downside is that they could be ‘considerably more demanding for respondents’, in particular in the case of the basic income which is less well-known in the broader public (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 227). Hence, the risk of measuring non-attitudes remains, but is likely mitigated by the fact that respondents get a more concrete and tangible impression of what a basic income would entail compared with a more abstract, single-item question in a regular survey.

Studies of public support for basic income using conjoint/vignette designs were conducted in Finland, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium and the Netherlands (Gielens et al., Reference Gielens, Roosma and Achterberg2024; Laenen et al., Reference Laenen, Mulayi, Francisco and Van Lancker2023; Rincón, Reference Rincón2021; Rincón et al., Reference Rincón, Vlandas and Hiilamo2022; Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020; Van Hootegem and Laenen, Reference Van Hootegem and Laenen2023), but not yet in Germany. Taken together, these studies clearly indicate that policy design matters: overall support for basic income changes significantly depending on the design characteristics. A first core insight in that regard is that the ‘ideal-typical’ version of UBI is less popular than ‘other varieties that deviate more significantly from the ideal type’ (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 148). The feature that stands out most in this respect is conditionality. Accordingly, schemes in which the payment of a basic income is tied to particular conditions (the individual’s willingness to work, get training or participate in voluntary activities) are generally supported more than unconditional schemes (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 195). Furthermore, regarding universalism, studies find more support for basic income schemes that put some restrictions on who should have access (such as citizenship or long-term residence requirements). More generous basic income schemes tend to be more popular, but there is a ceiling effect in the sense that support does not increase further above a certain (probably country-specific) threshold (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 127). Basic income schemes below the subsistence level are particularly unpopular. Regarding financing, ‘popular support is greatest for basic income schemes that are funded by taxing the rich’ (ibid.: 137) and lowest for those that would be financed with cutbacks in other parts of the welfare state or increases in general taxation. Finally, there are indications of variation in support patterns across countries, but given the different research designs and data collections, it is hard to judge whether this variation is genuine or a statistical artefact.

In sum, research on public opinion towards UBI shows that beyond individual-level factors, policy design plays a crucial factor in shaping support. Against this background, this paper makes two key contributions: First, we present the first vignette-based study of public opinion towards UBI for the case of Germany. Given the importance of Germany as a signature case of a ‘conservative welfare state’, we believe that this analysis yields insights of broader relevance as we discuss further below. Second, we explore interaction effects between design features and individual-level respondent characteristics more extensively than previous studies, which have mainly examined interactions between vignette dimensions (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023; Rincón, Reference Rincón2021; Rincón et al., Reference Rincón, Vlandas and Hiilamo2022). We focus on how vignette dimensions interact with respondents’ ideology, income and age.

Theoretical expectations

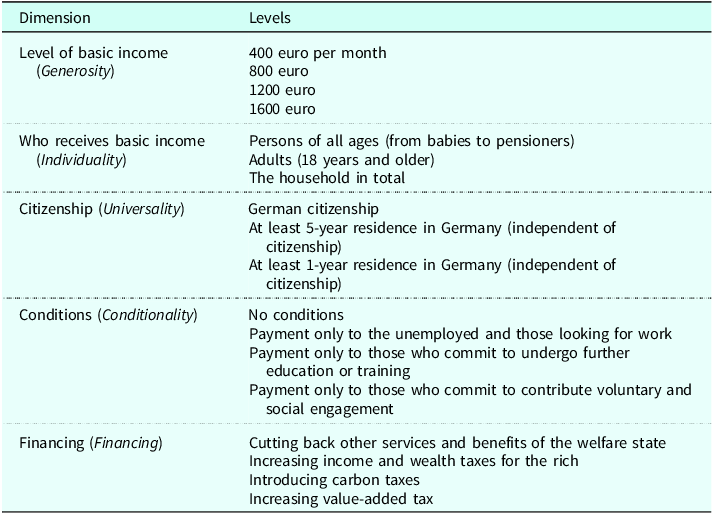

To facilitate the theoretical discussion, we introduce the basic design of our vignette. A first important matter to consider is how many dimensions should be taken into account. Even though researchers tend to agree that basic income is a fundamentally multi-dimensional concept, there is no agreement regarding the relevant number of dimensions, which might range from three (Gielens et al., Reference Gielens, Roosma and Achterberg2024) to seven (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2004) or even twelve (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023). Moving from theoretical discussion to empirical implementation, the conjoint/vignette design should not become overly complex to avoid overburdening respondents. Thus, the studies mentioned above typically choose five or six dimensions with several levels (two to five) per dimension. We proceed similarly. Table 1 presents the dimensions and their levels used for the vignette. In the vignettes, the information is not presented in tabular form (as in Table 1), but in the form of a written text. Further details are given below.

Table 1. Vignette design for a hypothetical basic income scheme

Note: The terms in brackets indicate the abstract (theoretical) dimension that the empirical dimension refers to (based on Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: Figure 1.1, p. 19).

Source: Own calculations.

Vignette dimensions

We first derive theoretical expectations regarding the different dimensions, that is, how and to what extent policy design features shape overall levels of support. Here, we focus on the theoretically most relevant associations, leaving some further issues to be discussed in the empirical section.

To start with the generosity of the basic income, we expect overall levels of support to increase in line with generosity, as more generous support from the welfare state should be welcomed in principle. However, the association might not be linear, as respondents could become concerned about the financing of a (very) generous basic income above a certain threshold. The first level in this dimension given in the vignette is slightly below the German subsistence level (as defined by the benefit level in the ‘Hartz IV’ system, which was about 450 euro per month for single individuals in 2022). Here it is important to note that housing subsidies are paid (depending on local market conditions) on top of ‘Hartz IV’ benefits, thus the effective subsistence level is rather in the range of 800–1000 euros. The official poverty threshold for singles amounts to 1250 euros per month in 2022,Footnote 4 hence it could be argued that even the third level in the vignette dimension (1200 euros) is still close to the subsistence level to some extent. Hence, benefit levels above this threshold could be perceived as too costly. In short, we hypothesise an increase in support if the level of the hypothetical basic income increases (H1.1).

Regarding individuality, there is little we can draw on in existing research as this dimension does not feature prominently in the existing conjoint/vignettes studies. Nevertheless, it is important to include in the case of Germany because of the abovementioned debate regarding introducing the basic insurance/income (Kindergrundsicherung) for children. As children are likely to be perceived as particularly deserving of support (because of their particular needs and their limited ability to control their circumstances), we expect that support will increase when children are mentioned as recipients of a basic income (H1.2).

In the case of universality, previous research paints a clear picture: public support should be highest for basic income schemes that restrict access to German citizens, and lowest for those that open up access to even short-term residents (H1.3). This is because citizenship still defines basic boundaries of solidarity, although it is an open empirical question whether respondents would differentiate between citizens and long-term residents. On the basis of the literature cited above, we also expect strong effects of conditionality. More specifically, conditional types of basic income, independent of the particular conditions enforced, should be more popular than unconditional types (H1.4). Given that the unemployed are typically seen as less deserving of support (Van Oorschot, Reference Van Oorschot2006), we expect public support for conditional basic income schemes referring to education and training as well as voluntary engagement to be higher than those that refer to the unemployed. The reference to voluntary engagement refers to Atkinson’s proposal of a participation income (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1996), which was found to enjoy high levels of popularity (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 230) (independent of the fact that an obligation to engage in voluntary activities is a contradiction in terms).

Finally, on financing, we expect the highest level of support for schemes that propose to finance the basic income by increasing taxes on the rich, whereas tax increases for everyone (via the value-added tax) or cutbacks in other welfare state services should be least popular (H1.5). This expectation is based on a simple redistributive logic, whereas the majority of the population expects to benefit from a universal basic income, but would like to externalise costs to ‘the rich’ – a relatively diffuse category that most people do not count themselves in (Bellani et al., Reference Bellani, Bledow, Busemeyer and Schwerdt2021). This hunch is supported by empirical research showing high public support for progressive taxation across a large number of countries (Barnes, Reference Barnes2015). By contrast, cutbacks to the welfare state are deeply unpopular (Busemeyer and Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017) and therefore less likely to have a negative effect on support for BI schemes that would be financed via this instrument. Finally, even without being aware of the details of taxation, people are likely to expect negative consequences for themselves in the case of increasing value-added taxes, as tax rises are generally unpopular (except when focussed on the rich).

Heterogenous treatment effects

Next, we develop hypotheses on the role of respondent characteristics in shaping public attitudes towards basic income. Again, we focus on the theoretically most relevant associations to keep things simple.

Regarding income, previous research has shown that low-income individuals are more likely to support the introduction of a UBI (Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2019, Reference Vlandas2021; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and Van Oorschot2020). Given that individual income is associated with general support for redistribution (Meltzer and Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981), we posit that interactions with the respondent’s income should be strongest for vignette dimensions with clear redistributive implications, namely generosity and financing. In these cases, high-income respondents should be more opposed to income schemes that are either more generous (i.e. expensive) and/or financed by taxes targeted on the rich (i.e. themselves). Low-income respondents, by contrast, should be more in favour of more generous schemes and supportive of schemes financed by tax hikes on the rich (H2.1).

Besides income, existing research has revealed a strong association between the individuals’ age and support for UBI, with younger individuals being more supportive of UBI (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023). It remains somewhat unclear whether this effect is primarily driven by labour market concerns (with the elderly expected to be in more secure positions) or whether age-related differences are driven by generational changes in value orientation (independent of political ideology). Given the limitations of our data, we cannot address this question directly, but would generally expect that young respondents should be more supportive of more generous and less conditional basic income schemes (H2.2), given the overall higher support for UBI amongst the young.

Finally, individual ideology has been identified as an important determinant of support for UBI (Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and Van Oorschot2020; Schwander and Vlandas, Reference Schwander and Vlandas2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2019). Even though some argue that basic income could be an issue ‘beyond left and right’ (Chrisp, Reference Chrisp2017) as it unites aspects of traditional right- and left-wing ideology, empirical work has clearly shown that the strongest support for UBI comes from the left, both in terms of individuals as well as political parties. Regarding the latter, Green (and related left-liberal) parties tend to stand out as the most ardent supporters of UBI. Thus, in general we expect individual left-wing ideology and support for the Greens to be associated with more support for basic income schemes. Regarding interactions with vignette dimensions, we expect that left-wing ideology/support for the Greens should be associated with more support the closer the hypothetical basic income scheme comes to the abovementioned ‘ideal-type’ of a universal, unconditional individual income given to all (H2.3). By contrast, support amongst right-leaning individuals should increase when policy design features point more towards the liberal, low-level and conditional variant of basic income.

Data and methods

The data for this analysis were collected by a professional survey company (Bilendi) in August 2022, using an online access panel with quotas for age, gender and educational background. The sampling population was the German resident population between the ages of 18 and 84 years. The survey company implemented quality control measures, leading to the exclusion of 171 respondents flagged as speeders or straight-liners and 211 respondents who failed an attention check. After these exclusions, the final sample consisted of 4500 respondents.

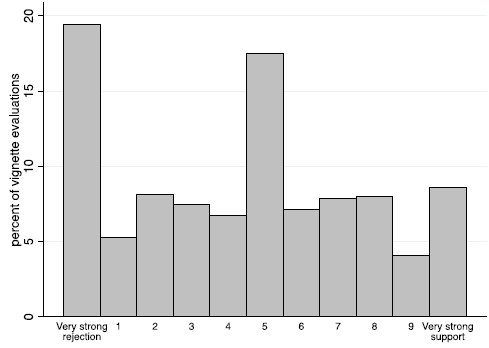

Figure A1 in the appendix is a screenshot of an exemplary vignette (implementing the design featured in Table 1 above). The vignette universe consists of 4 × 3 × 3 × 4 × 4 = 576 vignettes. We employed complete randomisation, so that each combination of dimensions had the same probability of being selected by the random generator. Each respondent received and assessed three randomly generated vignettes in sequence. The vignettes were introduced with a short text: ‘A further reform that is currently being discussed is the introduction of a universal basic income. In politics, different types of basic income schemes are discussed. In the following, we will show you three different reform proposals and subsequently ask for your opinion on these proposals’ (authors’ translation). After reading the vignette text, respondents were asked to indicate how strongly they would support each reform proposal, measured on an eleven-point scale from zero (very strong rejection) to ten (very strong support). This measure is the dependent variable for the following analyses. Figure 1 shows that even though there are upticks on the very low end of the scale as well as the mid-point, there is significant variation across the whole range of the dependent variable.

Figure 1. Distribution of support for basic income (independent of policy design features) across the whole scale.

Source: Own calculations.

The survey also contains questions on a number of individual-level variables, which we use in our analysis of heterogenous treatment effects. For respondents’ age, we generate five groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60+ years). Monthly household net income is captured in six categories (EUR < 900, EUR 900 – < 1500, EUR 1500 – < 2600, EUR 2600 – < 4000, EUR 4000 – < 6000, EUR 6000 and more); we merge the two categories with the highest income due to the low share of very high earners in the sample. For political ideology, we employ two measures: First, we use a question to gauge respondents’ self-placement on the left–right scale (from 0 = left to 10 = right), merging self-placements below five to ‘left’ and above five to ‘right’ for the analyses. Second, we ask whether respondents identify with a particular political party, and if so, which one.

Our dataset has a hierarchical structure, as each respondent rated three vignettes, resulting in repeated measures nested within individuals. Since ratings from the same respondent are likely to be correlated, ignoring this dependence in standard linear regression could lead to biased standard errors and inefficient estimates. To account for this, we apply random-intercept models with a generalised least squares (GLS) algorithm to estimate the impact of all policy design characteristics on support for basic income. The random intercept captures individual-level heterogeneity by allowing each respondent to have their own baseline level of support, thereby controlling for unobserved respondent-specific factors (Baguley et al., Reference Baguley, Dunham and Steer2022). In the following, we discuss the effects of regressing support for basic income on the five vignette dimensions.

Results

Vignette dimensions

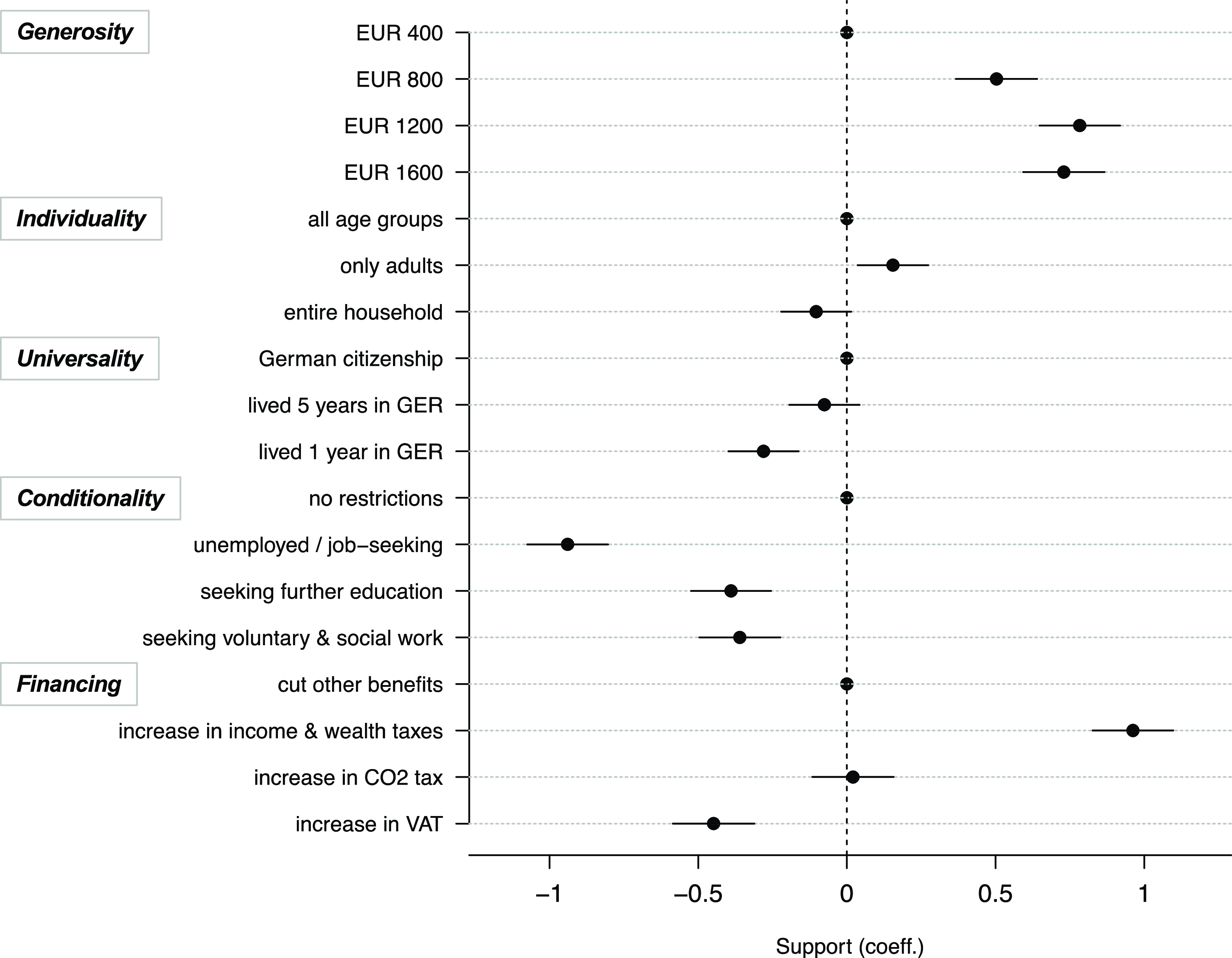

Figure 2 displays the impact of policy design characteristics on support for basic income schemes (the coefficients are supplied in the appendix in Table A2). As hypothesised (H1.1), a higher level of the hypothetical basic income is associated with a significant increase in support, but there is a clear ceiling effect: Setting the level at EUR 1600 does not lead to a further increase in support compared with a level of EUR 1200, even though both options are more supported than an income set at a low subsistence level (i.e. EUR 400). This ceiling effect could result from citizens being at least vaguely aware of the direct and indirect costs of a generous basic income for fiscal policy and the economy.

Figure 2. Impact of policy design characteristics on support for basic income.

Source: Own calculations.

Contrary to our expectations, the inclusion of children in the group of beneficiaries is associated with lower support compared with a basic income that would be paid out to adults only (H1.2). However, the magnitude of this effect is small, although statistically significant. In case that basic income is paid to the entire household rather than to individuals, public support decreases somewhat, which is more in line with our previous expectations. Regarding universality, we find that respondents do not strongly differentiate between German citizens and long-term residents when it comes to questions of eligibility (H1.3). However, support for basic income drops significantly if residence requirements are lowered to 1 year only.

The most surprising finding concerns conditionality. Contrary to much of the existing literature (as well as H1.4), we find that basic income schemes that impose no conditions on recipients are most popular when compared with schemes that are conditional on the recipient being unemployed or seeking work. The latter effect is likely related to low deservingness perceptions of the unemployed as a group. However, even the imposition of conditions for participating in education/training and doing voluntary work is associated with lower support relative to an unconditional basic income. Potentially, this unexpected finding could be explained with the legacy of the ‘Hartz IV’ system (named after the fourth reform law of the Hartz reforms). The so-called Hartz reforms of labour market policy enacted in 2005 significantly increased workfare components in the German unemployment system, such as training requirements and strong incentives to accept ‘suitable’ job offers. This change significantly enhanced the conditionality of unemployment benefits and became a symbol of more precarious labour market conditions. Our survey findings might indicate that because of this lasting legacy, notions of conditionality are less supported amongst the German resident population than in other countries.

Finally, again more in line with our theoretical expectations (H1.5), we find that taxing the rich is by far the most popular option regarding the financing of a hypothetical basic income, also indicated by the large magnitude of the effect. By contrast, increasing taxes for all (via value-added taxes) significantly lowers support. The two remaining options (cutting back other welfare state benefits and increasing carbon taxes) are significantly more popular than the increase of value-added taxes, but find significantly less support than increasing income and wealth taxes for the rich. These findings clearly show that – from the perspective of citizens – adding a redistributive component to basic income increases support.

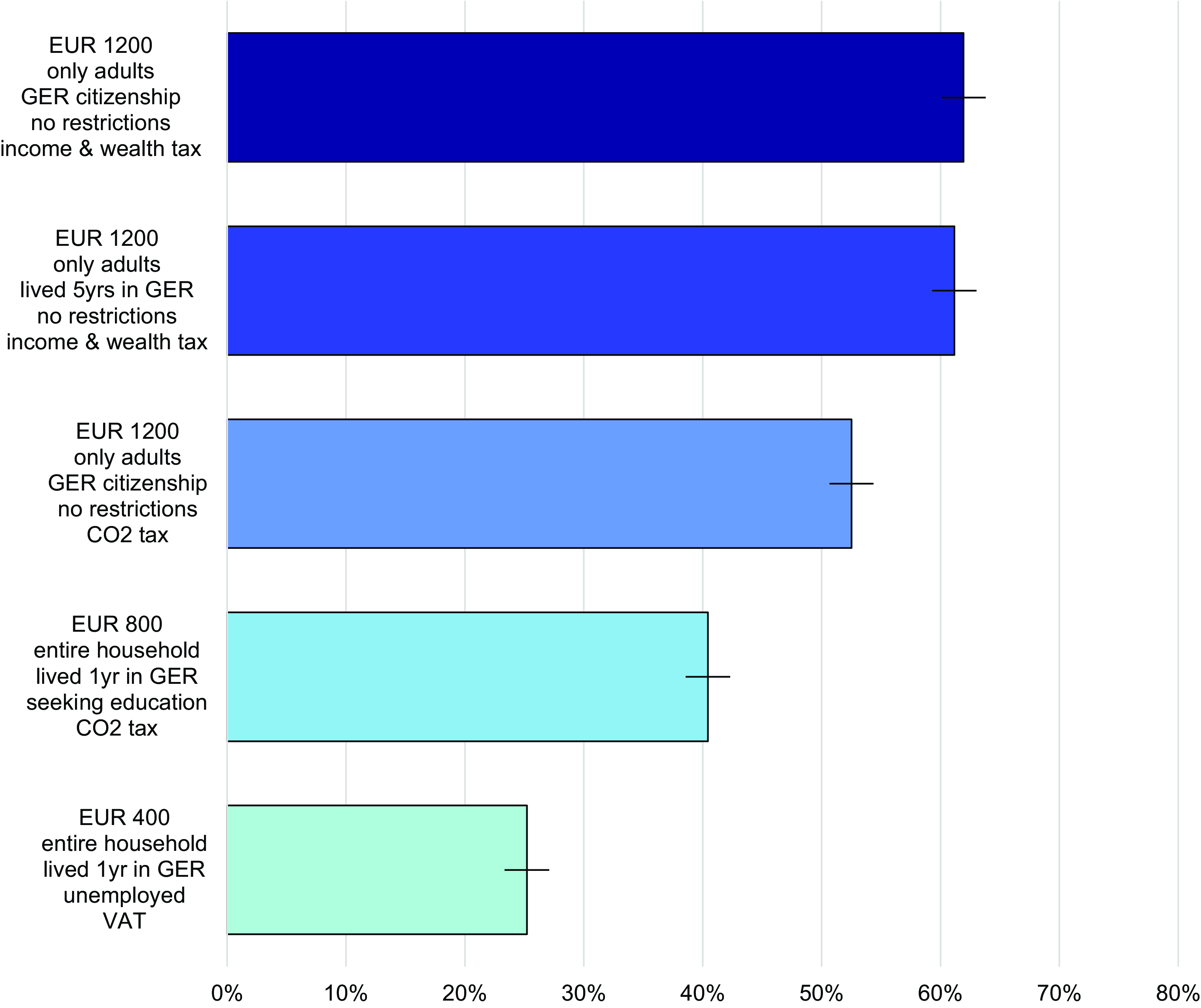

Figure 3 presents a different perspective on the results of the vignette study by giving predicted levels of support for selected policy designs. This selection is necessarily arbitrary. Out of the total of 576 policy designs, we select five representative policy designs on the basis of the findings from Figure 2 regarding the relative popularity of different design characteristics. This is done to highlight the potential impact of policy design on overall support for basic income. This exercise shows that a policy design that combines the most popular features is supported by 61 per cent of respondents. By contrast, the least popular combination is only endorsed by 26 per cent. These figures show that policy design matters strongly in shaping support.

Figure 3. Predicted levels of support for selected policy designs.

Source: Own calculations.

Respondent characteristics and support for basic income policies

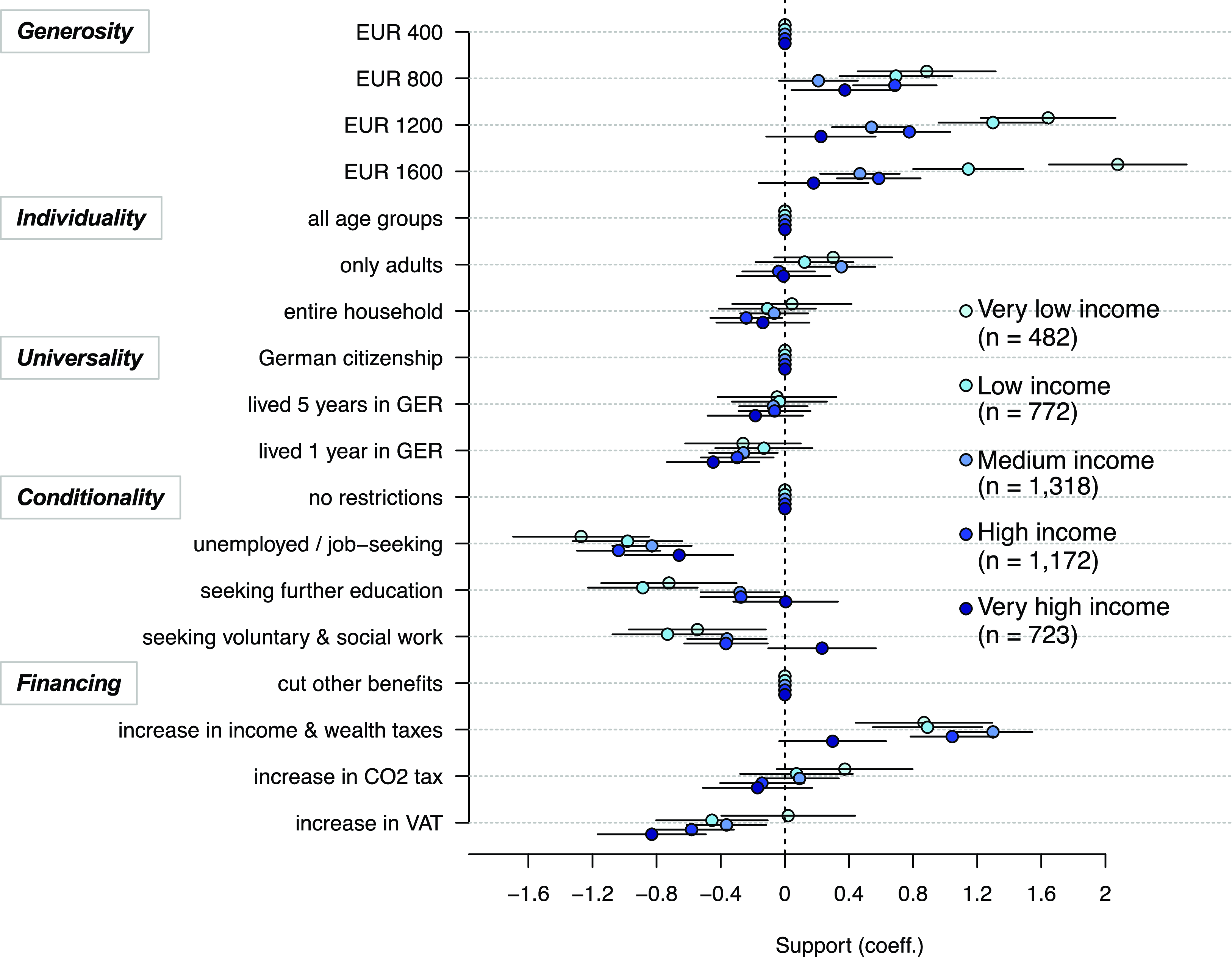

Next, we explore interaction effects between the vignette dimensions and individual respondent characteristics. Regarding individual income, we expected that income effects would be strongest for those vignette dimensions that are related to redistributive concerns (i.e. generosity and financing) (H2.1). In line with this finding, Figure 4 (related to Table A3 in the appendix) shows significant interaction effects between income and generosity such that support for basic income amongst low-income respondents increases to a much stronger extent compared with high-income respondents. Not surprisingly, high-income respondents are also much less likely to support increasing taxes on the rich. High-income respondents also react much more strongly to increasing value-added taxes than lower-income citizens. Potentially, tax and fiscal policy preferences of lower-income citizens are less well defined, which might explain why there is little variation in support across the different financing options for low-income citizens. Moving beyond our initial expectations, we also see relatively strong interaction effects between income and conditionality. In this case, support for basic income drops to a stronger extent for low-income citizens when conditions are imposed compared with high-income citizens. We find similar patterns when using a subjective measure of people’s economic situation instead of income (see Figure A2(a) in the appendix). This makes sense from a self-interest perspective: low-income respondents might perceive a higher risk of becoming unemployed in the future, therefore they are more opposed to conditions attached to transfers given the legacy of the Hartz system discussed above. Whilst our dataset only contains a relatively low share of unemployed (5.3 per cent) respondents, reflecting the currently low level of unemployment in Germany, we also tested whether employment status interacts with conditionality (see Figure A2(b) in the appendix). Accordingly, at least for two of the three levels capturing conditions, unemployed respondents indeed tend to reduce their support even more strongly compared with (self-)employed or retired respondents.

Figure 4. Heterogeneous treatment effects for different income groups.

Source: Own calculations.

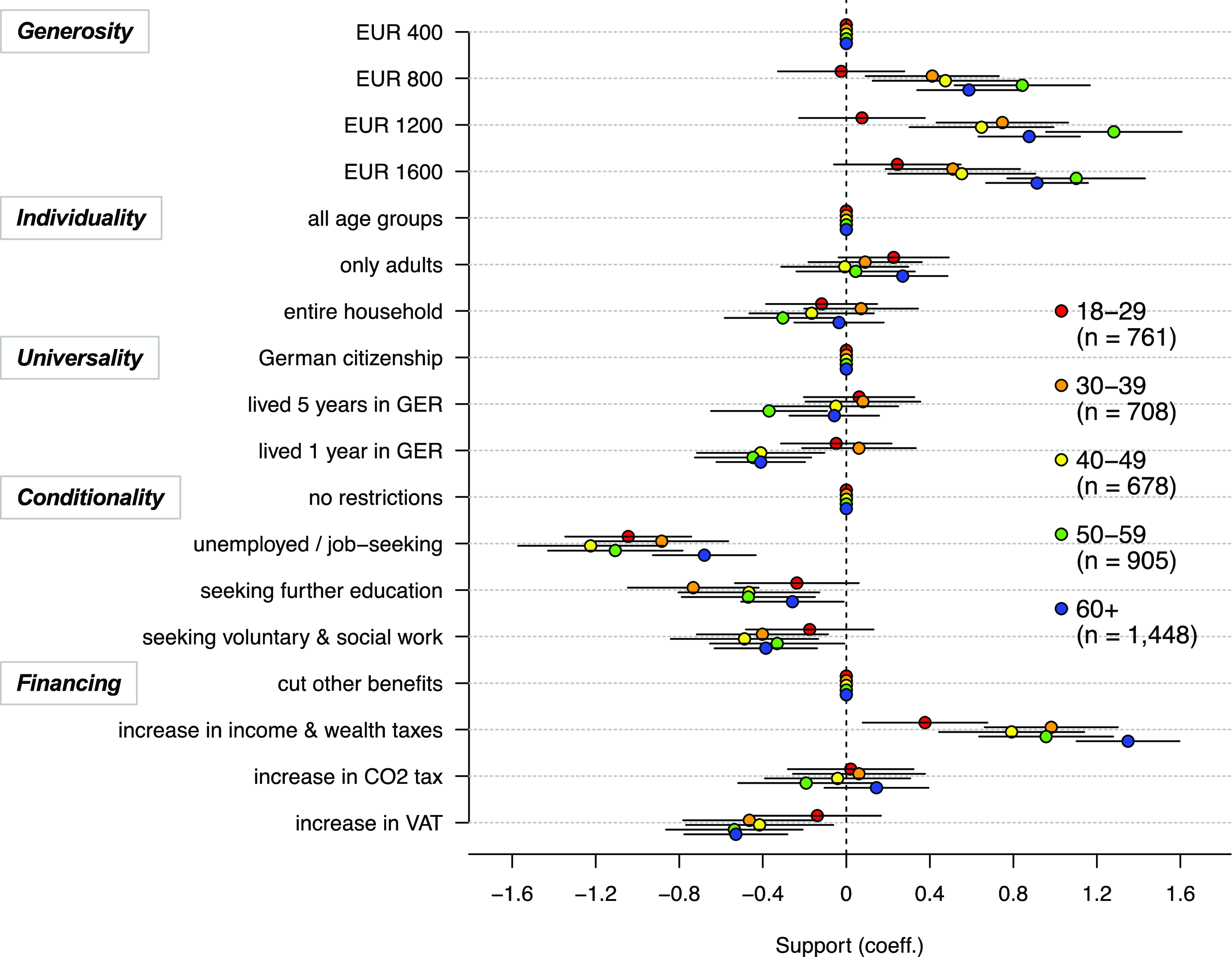

Figure 5 (related to Table A4 in the appendix) displays heterogeneous treatment effects for different age groups. Given the well-known negative association between age and general support for basic income, we expected young respondents to be more supportive of more generous and less conditional schemes (H2.2). The results only partly confirm these theoretical expectations. First of all, even though there is a significant interaction effect between age and generosity, it points into the opposite direction as expected, as elderly citizens are more likely to support generous basic income schemes, in particular the age group between the ages of 50 and 59 years. Given the rapid pace of technological change and related socio-economic transformations, this age group might perceive itself to be at higher labour market risk compared with the young. Regarding conditionality, differences in support across age groups are rather negligible, but there are more pronounced age-related differences when it comes to financing. In particular, support for basic income increases strongly if financed via taxing the rich (compared with the baseline of cutting other benefits) amongst the elderly, whilst this preference appears to be much less pronounced amongst respondents younger than 30 years.

Figure 5. Heterogeneous treatment effects for different age groups.

Source: Own calculations.

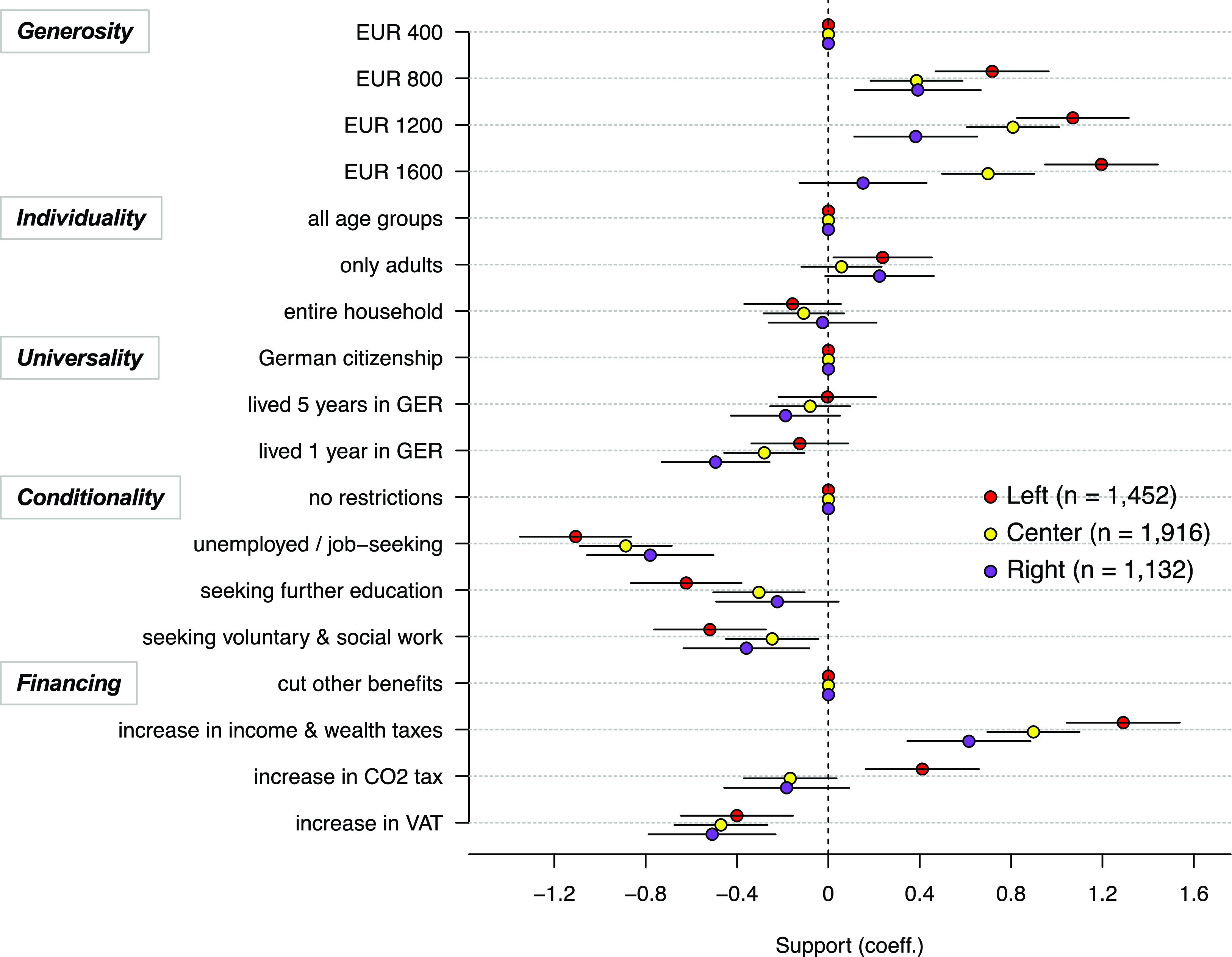

Finally, Figures 6 and 7 focus on the interactions between individual ideology on a left–right scale (Figure 6) or support for particular political parties (Figure 7) and the vignette dimensions (see also Tables A5 and A6 in the appendix). We expected that support amongst left-wing respondents and supporters of left-wing parties should increase the closer the proposed basic income scheme comes to the ideal-typical model discussed above (H2.3). This expectation receives some empirical support: support amongst left-wing respondents increases for more generous basic income schemes and drops to a stronger extent when conditions are introduced. In addition, support amongst left-wing respondents increases if basic income schemes would be financed by taxing the rich. Right-wing proponents’ support drops strongly when residence requirements are loosened.

Figure 6. Heterogeneous treatment effects for groups with different ideologies.

Source: Own calculations.

Figure 7. Heterogeneous treatment effects for groups supporting different parties.

Source: Own calculations.

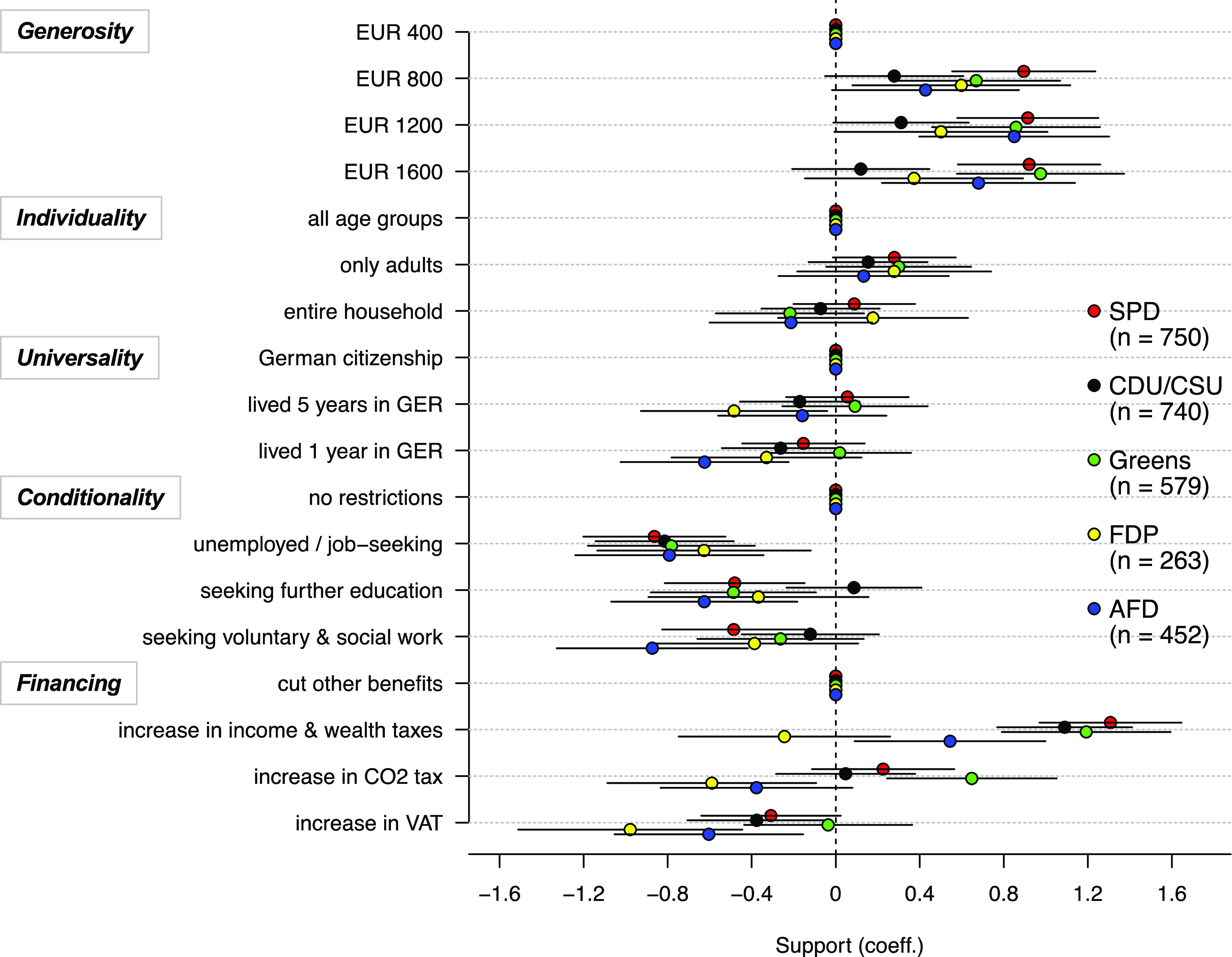

Moving beyond the simple left–right ideological scale, Figure 7 displays variation in support across different constituencies of political parties. Note that the number of respondents represented in this figure drops to 2,784 as some respondents did not identify with a particular party and are therefore excluded from this part of the analysis. Moreover, results for supporters of smaller parties (e.g., the Left) are not shown due to a relatively low number of cases.

As could be expected, with respect to increasing generosity, support for basic income increases to a stronger extent amongst supporters of left-wing parties (the Greens and the SPD) compared with conservative and liberal parties (CDU/CSU and FDP). Somewhat surprisingly, supporters of the right-wing populist AfD are in between these poles, which might indicate that AfD supporters perceive themselves to be economically vulnerable and therefore potential beneficiaries of a basic income. Interestingly, AfD supporters are also clearly different from supporters of the CDU/CSU, with the former being more supportive of less conditionality (see also Figure A3 in the appendix) and the latter of more conditionality. Support for basic income drops significantly amongst AfD supporters if residence and citizenship requirements are loosened, indicating the presence of welfare chauvinist attitudes. Pronounced partisan differences can also be observed in the case of financing, where supporters of left-wing parties generally react more positively to proposals of tax increases, whereas right-wing party supporters, in particular those of the liberal FDP, react more negatively.

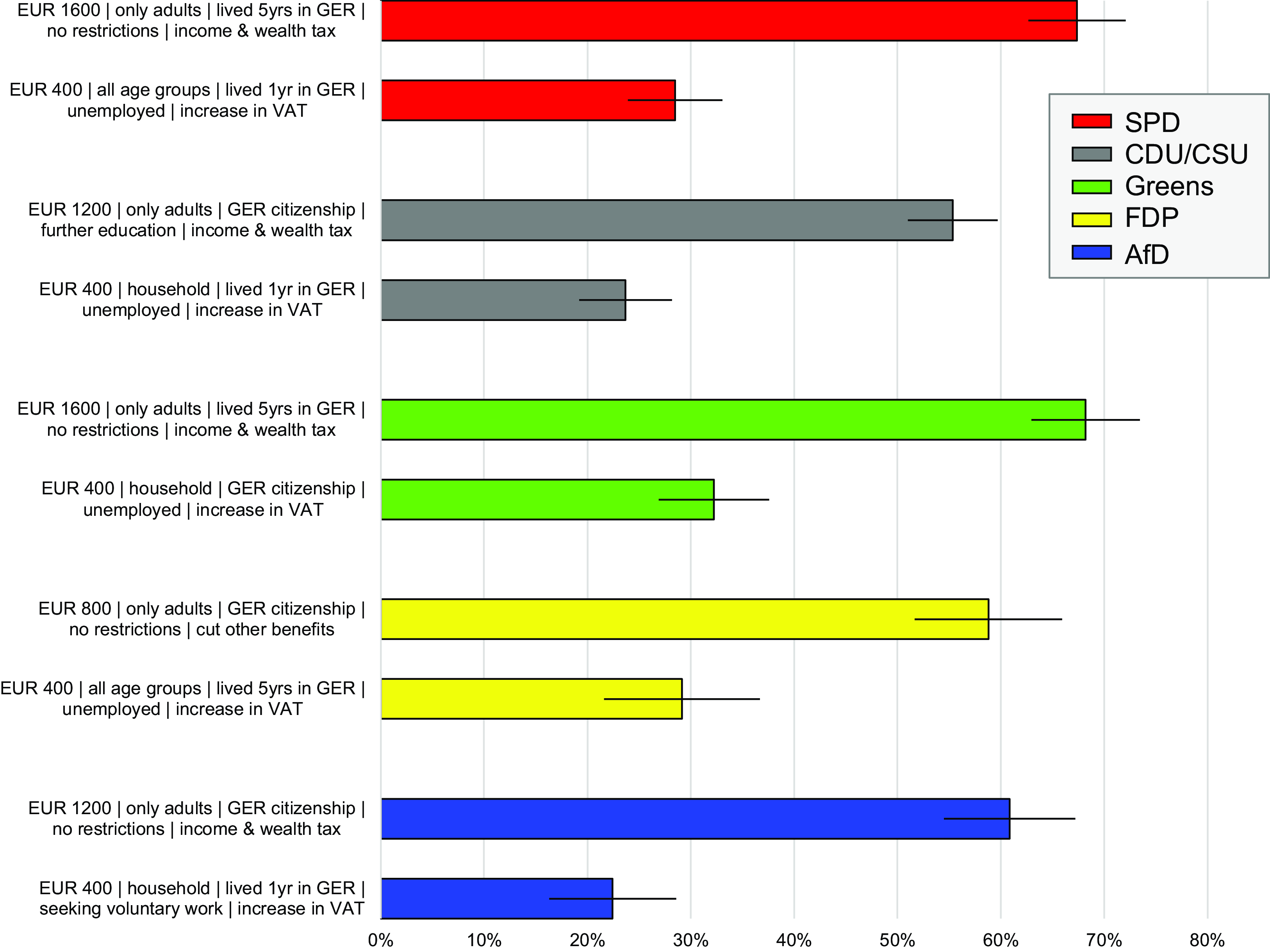

Figure 8 (constructed in analogy to Figure 3) provides an alternative perspective on these findings by showing the predicted levels of support for the most and least popular combination of design characteristics within the different partisan constituencies. This shift in perspective confirms H2.3 from above, which states that supporters of green and left-wing parties (i.e. the Greens and the SPD) are most supportive of basic income schemes that come closest to the ‘ideal-typical’ model of a generous, universal and unconditional basic income. The figure, however, also shows the substantial support for basic income schemes amongst supporters of right-wing and liberal parties (CDU/CSU, FDP and – to some extent – the AfD), although in this case, schemes that are somewhat less generous, less universal (by being tied to German citizenship) and partly more conditional (for supporters of CDU/CSU) receive the highest levels of support.

Figure 8. The most and least popular basic income schemes across different partisan constituencies.

Source: Own calculations.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper analysed public support for basic income, employing a vignette survey design to tease out how support changes depending on different policy characteristics of the hypothetical basic income scheme. It thereby complements existing studies using similar research designs in Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland, as cited above. A first important take-away is that even in Germany, where previous research has shown below-average level of general support for UBI, support for BI schemes increases significantly, depending on the particular design features. As Figure 3 shows, combining the most popular design features, support for basic income can go up to more than 60 per cent, which is significantly higher than the 45 per cent who expressed support for UBI in the ESS 2016 wave (Adriaans et al., Reference Adriaans, Liebig and Schupp2019: 129). This finding also puts into perspective some arguments in the literature, claiming that support for basic income is ‘fragile and susceptible to “wilting” once specific models are specified’ (Chrisp et al., Reference Chrisp, Laenen and Van Oorschot2020: 224, see also Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont, Reference Stadelmann-Steffen and Dermont2020: 384). We find the opposite, namely that providing further details on the design of hypothetical basic income schemes can significantly boost support. At the same time, policy designs that combine the least popular design characteristics will fail to mobilise support. Thus, as often is the case, the devil is in the details.

When it comes to particular dimensions of BI schemes, our results are in some regards similar to previous studies (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023): we also find that more generous basic income schemes are more popular (up to a certain upper limit) and that taxing the rich to finance basic income boosts support. Equally in line with previous work is that respondents support imposing some limits on universality, although German respondents do not differentiate between citizens and long-term residents. The biggest difference between our results and existing research concerns the dimension of conditionality. Whereas most other studies find increased support for BI schemes that enforce some kind of conditionality (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 195), in our case, unconditional basic income schemes receive more support than those that would impose some form of conditionality. This is all the more surprising against the background of Germany’s legacy as a ‘conservative welfare state regime’ (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), in which there is a tight connection between employment status and access to welfare state services and benefits.

This could be related, as we argue, to the lasting legacy of the Hartz system of unemployment insurance that enforced strong conditionality and was deeply unpopular, not only amongst the transfer recipients themselves, but also in the broader population, in particular amongst those who perceived themselves to be at risk of becoming unemployed. Therefore, support for more unconditional BI schemes could be an indication of a self-undermining policy feedback effect (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Abrassart and Nezi2021) in the sense that public opinion turns away from the status quo due to perceived negative feedback effects. In line with this idea, the reformed Hartz system, renamed ‘citizens’ income’ (Bürgergeld), has reduced conditionality starting in January 2023, even though it does not amount to a fully unconditional transfer payment in the sense of a UBI. Indicative evidence for a similar logic at work in other countries is provided by Rincón et al. (Reference Rincón, Vlandas and Hiilamo2022) for the case of Finland, where unconditionality seems to be much more contentious than in Germany, which could be interpreted as self-undermining policy feedback relative to the status quo of a universalist welfare state model. Future research could and should try to collect more systematic evidence on how welfare state regime characteristics are related to support for particular design features of BI and other transfer schemes, which would require a coordinated data collection effort of survey data in multiple countries.

When it comes to respondent characteristics, we mostly focussed on heterogeneous treatment effects of the vignette dimensions, as our results on the direct associations between individual-level factors and overall support for basic income largely confirm existing research. Existing research on support for BI using vignette designs has often not explored these heterogenous treatment effects. We found strong interaction effects between design features and individual respondent characteristics for income, with high-income citizens tending to reject basic income schemes with strong redistributive components (i.e. generous levels or financed by taxing the rich). Interactions with age reveal that middle-aged groups are most supportive of more generous basic income schemes, whereas the young tend to support conditionality comparatively less. We also find significant interaction effects with individual ideology: left-wing supporters are significantly more supportive of basic income schemes that come closer to the ideal-typical model of a universal, unconditional and generous basic income. More surprisingly, we also find indications of significant support for more generous basic income schemes amongst AfD supporters, which sets them apart from the constituencies of conservative and liberal parties.

In closing, we highlight some limitations of our study. Even though public opinion is a crucial factor in mobilising political support for the introduction of a basic income, it is not the only factor that matters. Other actors, in particular interest groups and administrative actors, matter as well, and could significantly slow down policy-making reforms in spite of favourable public opinion (Laenen, Reference Laenen2023: 27; Kangas, Reference Kangas, Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simamainen and Ylikännö2021) and intensifying political activism (Liebermann, Reference Liebermann, Caputo and Liu2020). It is also not a given that the positions of political parties immediately reflect their voters’ opinions (Gielens et al., Reference Gielens, Roosma and Achterberg2023), and existing welfare states might simply not have sufficient economic, fiscal and administrative capacities to implement ambitious basic income schemes even if the public demands them (Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020). Notably, even in Finland with its long history of policy debates about basic income, academic observers regard it as unlikely that a genuine UBI will be introduced any time soon (Halmetoja et al., Reference Halmetoja, De Wispelaere and Perkiö2019; Koistinen and Perkiö, Reference Koistinen and Perkiö2014; Kangas, Reference Kangas, Kangas, Jauhiainen, Simamainen and Ylikännö2021). Thus far, therefore, there is little evidence that the political coalition in support of UBI is strong enough to drive radical change, potentially also related to ongoing divisions within the left (Schwander and Vlandas, Reference Schwander and Vlandas2020; Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2018). Still, future research might continue to study patterns of public support to identify political coalitions in the making.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at a workshop of the working group on Comparative Political Economy at the University of Konstanz and the 2023 Annual Conference of FRIBIS at the University of Freiburg. We thank the participants at these events as well as, in particular, Jurgen De Wispelaere, Jürgen Schupp and Tim Vlandas for additional comments and feedback. We also thank the reviewers and editors of JSP for helpful feedback and suggestions.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279425100871