Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men within the UK, with 56,780 men in the UK diagnosed in 2020. 1 Of those diagnosed with prostate cancer, 30% will undergo external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) treatment 2 and 78% are expected to survive for 10 years or more after diagnosis; 2 therefore, there is an increasing population of prostate cancer survivors who are living with the long-term effects of cancer treatment.

Sexual dysfunction (SD) is a long-term side effect associated with all prostate cancer treatments Reference Ávila, Patel and López3 and is self-reported as an important concern to both patients Reference Watson, Shinkins and Frith4 and their partners. Reference Bobridge, Bond, Marshall and Paterson5–Reference Mehta, Pollack and Gillespie10 The most well-known radiation-induced sexual dysfunction (RISD) is erectile dysfunction (ED), Reference White11 and it occurs in approximately 67–85% of patients receiving EBRT. Reference Dyer, Kirby, White and Cooper12,Reference White, Wilson and Aslet13 Additional sexual side effects of EBRT include altered sensation during orgasm, orgasmic dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, incontinence during sexual activity, and changes to penile morphology and sensation. Reference Parekh, Chen and Hoffman14–Reference Gallagher and Ramsden19 The effect of SD on the quality of life (QoL) for men who have sex with men (MSM) is different as male–male sexual intercourse places a greater emphasis on erections, seminal fluid release, penis size, and the prostate as a pleasure centre, and also the change to an anal receptive role within a relationship may not be comfortable due to treatment, or desirable. Reference Ussher, Perz and Kellett20,Reference McInnis and Pukall21

The evidence base relating to these issues suffers from variance in methods including ranges of scoring criteria, Reference Ferrer, Guedea and Suárez22–Reference Neal, Metcalfe and Donovan32 and timing of both data collection and interventions. Reference Ferrer, Guedea and Suárez22–Reference Olsson, Alsadius and Pettersson33 It is not surprising then that there are deficiencies in the UK for the provision of support for treatment-associated SD. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34–Reference Downing, Wright and Hounsome36 For example, a national UK review of practices for radiotherapy departments found that only 8% of respondents recommended abstinence from a receptive role in anal sex, Reference Nightingale, Conroy, Elliott, Coyle, Wylie and Choudhury37 showing that many MSM patients in the UK are not being given this information.

There is a dearth of studies analysing the quality of SD information given to prostate cancer patients receiving EBRT, only one study was found. Reference Grondhuis Palacios, Krouwel and Duijn38 This study’s findings showed that one in four patients treated for prostate cancer said that their sexual side effect information was inadequate. Reference Grondhuis Palacios, Krouwel and Duijn38 Correctly conveying SD information verbally and in written form is essential for patients to understand at the time of explanation and refer to later, and this reduces the chance of a discrepancy between what is expected and the reality of the sexual side effects. Reference Grondhuis Palacios, van Zanten and den Ouden39 It is in the patient’s best interest to be fully informed about RISDs, even if they do not think it a priority for themselves, for example, they are not sexually active. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34 Pre-treatment conversations surrounding all SDs, the impact on self-perception and negative impacts on relationships should all frankly discussed Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34 as with any other treatment-related side effect. Reference Lynch, O’Donovan and Murphy40

This study, therefore, aimed to build on this evidence to critically evaluate the quality, timing and format of SD information given to EBRT patients before, during and after treatment to the prostate.

Methods

The development of the questionnaire was based on clinical experience of one of the authors, due to time restrictions no pilot study was performed, and the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of the questionnaire were not tested.

The study adopted a survey method to harvest a range of anonymous quantitative data regarding provision of SD information. The survey utilised an online questionnaire via ‘SurveyMonkey’ to gather feedback on

-

Demographics of participants (multiple choice)

-

Timing and format of SD information (multiple answer)

-

Evaluation of provided SD information (Likert questions)

-

Side effects included in information (multiple answer)

-

Abstinence from anal intercourse advice (yes/no)

-

Suggested improvements (free text)

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from 134 UK prostate cancer support groups via email invitation, using publicly available email addresses. An initial email was sent to the support group administrators describing the basic premise of the study. If the administrators were then willing, an introductory email was forwarded to members including participant information sheet, debriefing materials and survey link. The survey was open for 2 months and encompassed the following inclusion criteria:

-

Finished radical EBRT for prostate cancer

-

Over the age of 18 years

-

Able to consent for the study

-

Able to access the internet

Data analysis

Those who had received radiotherapy over 10 years ago were removed before data analysis. The reason to remove these questionnaires was to ensure that the experiences of the participants were current as possible.

A positivist approach was taken for quantitative data analysis Reference Norman and Eva41 following compilation of data in SSPS software. 42 The questionnaires were checked manually for formatting errors before analysis and excluded any questionnaires with that were incomplete. To avoid duplications, the online questionnaire tool was set up to prevent participants returning multiple questionnaires. Qualitative data from the open question underwent thematic analysis using an approach adapted from Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological method. Reference Giorgi43 All responses were read initially, and then each was assigned a code from common words or phrases. Codes were then collated into broader categories to form the themes.

Ethical approval, data handling and confidentiality

Ethical approval was gained through the University of Liverpool Ethical committee, with no NHS ethics committee approval necessary as the participants were recruited from prostate cancer support groups. Helpline information was provided in the debriefing materials for any respondents who became distressed through participation. Consent was embedded within the survey, and participation was impossible without this.

Confidentiality of the participants were maintained throughout the study by using the support group administrators as gatekeepers so that the study members had no contact with any participant. Study participants were not asked any identifying information, and IP addresses of the participants were not collected. All study data were securely stored on a University of Liverpool server.

Results

Study population

In total 97 men consented, and out of these there were 62 completed questionnaires. Six participants were excluded due to having their EBRT treatment over 10 years ago (Figure 1) to increase the applicability of the study data to current health care practice within the UK. Out of the 56 men whose responses were analysed, 32 (57·1%) had been given some form of SD information before, during or after EBRT treatment (Table 1). Table 1 shows the demographics of the population with each demographic apart from < 55 years old represented in both those who received SD information and those who did not. Thirty-three (58·9%) respondents had their EBRT treatment up to 48 months prior to participation and 23 (41·1%) respondents were between 49 and 120 months post-treatment. There were no identifiable trends linking information provision, age at time of treatment or time since treatment (Figure 2), although analysis of the Likert data indicated that the three participants who were most satisfied with their information were all under the age of 55 years at the time of treatment.

Figure 1. Inclusion and exclusion of returned questionnaires.

Table 1. Participant demographics and sexual dysfunction information provision

Figure 2. Influence of age and time since treatment on information provision.

Information format

Respondents were asked in what medium the SD information was given to them, that is, verbally, written or signposted to online resources. Of those who were given SD information (n = 32), 25 (78·1%) were given verbal information, 20 (62·5%) were given written information and 15 (46·9%) were signposted to online resources (Figure 3). From those who responded, 9 (28·1%) individuals were given all three forms of information at some point before, during, and after EBRT, 10 (31·3%) were given two forms of information, and 13 (40·6%) were given one form of information. Out of those who were given one form of information, 3 (9·4%) were only signposted to online information (Figure 3). Most information was provided before radiotherapy had begun with 25 (78·1%) participants receiving information during consent or at hospital clinics before EBRT. The least common location for SD information provision was during radiotherapy (Figure 3). After completion of treatment, 46 out of 56 participants did not receive any further information about SD.

Figure 3. Location and format of information provision (n = 32).

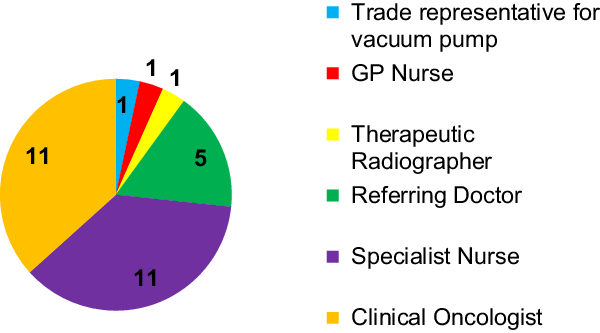

Information provider

Out of the 25 participants given verbal SD information, only 11 participants spoke with a clinical oncologist and 5 with referring physicians (Figure 4). Nurses were the next largest demographic of medical professionals who spoke to patients, while therapeutic radiographers only provided verbal information to one participant. These results were also reflected in the provision of written information, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Roles of people providing verbal sexual dysfunction information (n = 25).

Figure 5. Roles of people providing written sexual dysfunction information (n = 20).

Patient satisfaction

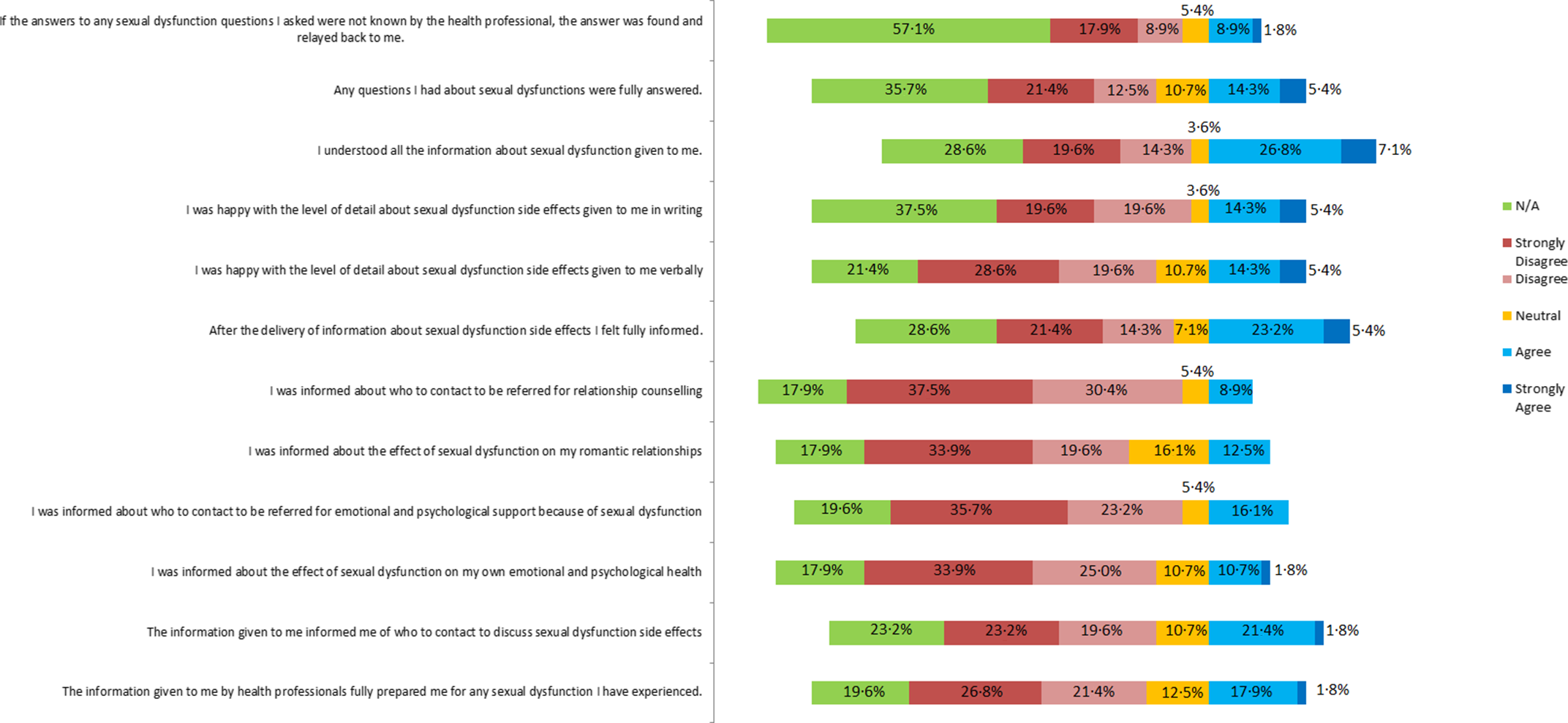

Likert scale responses to most prompts were either negative, neutral or non-applicable, with only a minority providing positive response to questions as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Responses to Likert scale questions about sexual dysfunction information received before during and after radical external beam radiotherapy to treat prostate cancer (n = 56).

Reported side effects

Participants were asked which SD side effects caused by EBRT they had been informed about. Out of 27 responses, the majority (n = 25) received information about ED, 7 were told about altered penile shape and size, and altered sensation at orgasm, 5 were informed about altered penile sensation, 4 participants were informed about urinary incontinence during sexual activity and 2 were told about pain during orgasm. Participants who have anal sex were asked whether they were offered any advice, that if they were the receptive partner and were having EBRT, to abstain from having anal sex for at least 2 months after finishing EBRT treatment. Five participants answered this question, and they all answered that no one gave them any advice about anal sex and abstinence during and after EBRT treatment.

Potential improvements

Fifty-four out of a total of 56 participants answered the free text question which simply asked what improvements could be made to the SD information that they received before, during and after radiotherapy treatment. Three themes emerged from the analysis of the free text question as seen in Table 2: ‘give information’, ‘support throughout the cancer journey’ and ‘no improvements mentioned’.

Table 2. Themes, subthemes and poignant quotes from the free text question

Theme 1 – give information

This was the theme with the most responses in which participants wanted at a minimum some SD information, and for those who received information they did not just want a greater depth of information, but who they thought should be delivering the information, and what medium of information, that is, written, verbal signposting should be given as a minimum.

Participant 37 – ‘I was totally let down from the very beginning as I had no information’.

More specifically participants wanted to have information given to them before radiotherapy treatment began in a full and frank manner, discussing everything that may happen to them. Some participants wanted a formal SD education session, either in person or virtually, before they started treatment as well as the option to involve their partner to learn with them. Other participants wanted medical professionals to engage and support them before, during and after treatment giving SD information and advice.

Participant 33 – ‘Written information prior to radiotherapy. Checks by Oncologist during treatment. Invitation to [a] sexual dysfunctional clinic after treatment’.

Theme 2 – support throughout the cancer journey

Participants voiced that there could be more SD support available for them, alluding to a reluctance from health care practitioners to refer patients to these services or a lack of services in their area. One participant stated that more information and someone to address their concerns would have prevented them from making decisions that they might not have needed to do, that is, refraining from sexual activity because they thought it would have a detrimental effect on their treatment.

Participant 82 – ‘We need more support, it is rather brushed under the carpet, I had to fight for all my support, it is like a taboo subject’.

Others wanted to have routine follow-ups at SD clinics and GP practices to assess their sexual function needs after treatment. Participants self-referred to sexual function clinics, so they could receive support and sexual function rehabilitation which they thought would be beneficial for them. Psychosexual counselling was mentioned as a service which more people should be referred to, as participants thought that psychological support would have been useful for their sexual function rehabilitation. In addition, some found the prostate cancer support groups psychologically effective and useful and wanted them to be recommended to patients on a routine basis.

Theme 3 – no improvements mentioned

A minority were pleased with the sexual function information they had received before, during, and after treatment, and therefore, mentioned no improvements. Another subgroup of participants assumed the information provision had improved since their treatment and similarly suggested no improvements.

Participant 44 – ‘Am sure it’s addressed now almost 10 years on’.

Discussion

Paucity of SD information provision

Just under half (42·9%) of participants in this study were not given any form of SD information, and there was reported variability in quantity and standards of that provided. This inequity in information provision has led to a detrimental effect on the expectations of this group as seen in Figure 6. These results correlate well with the results of recent studies, which suggested a lack of support for treatment-related SDs for this patient group. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34–Reference Downing, Wright and Hounsome36

Within the study, 73·2% of participants were not signposted to any online resources; this is at odds with a 2017 study, which reported that 86% of UK radiotherapy centres did signpost prostate cancer patients to further information. Reference Nightingale, Conroy, Elliott, Coyle, Wylie and Choudhury37 This large difference between the two results suggests that signposting to information services for SD may not be as common as for other treatment-related toxicities.

Provision of information is essential for shared decision-making and to avoid prioritising evidence-based practice over patients’ individual values and preferences. Reference Leech, Katz, Kazmierska, McCrossin and Turner44 With high numbers of patients failing to receive information about SD, there is a high possibility of treatment-related regret. More SD information discussions during and after EBRT could reduce the observed lack of support and underreporting of sexual side effects for this patient group detailed in recent UK studies. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34–Reference Downing, Wright and Hounsome36 Fewer clinicians (including clinical oncologists, nurses and therapeutic radiographers) provided SD information than recommended by recent studies. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34,Reference van Stam, Aaronson and Bosch45,Reference Christie, Sharpley and Bitsika46 Reported barriers to this include a lack of training and knowledge, a perceived lack of time, a shortage of specialists, or long referral times. Reference Watson, Wilding and Matheson35,Reference Grondhuis Palacios, Hendriks and den Ouden47 Therapeutic radiographers were the most underutilised medical professional in the provision of SD information. Studies have found that the involvement therapeutic radiographers are a positive indicator of a better understanding of treatment-related sexual side effects, Reference Grondhuis Palacios, van Zanten and den Ouden39 but they may lack confidence or subject knowledge in addressing this common radiotherapy-related side effect. Reference Lynch, O’Donovan and Murphy40

Participant satisfaction with information

The results displayed in Figure 6 predominantly show neutral and negative feelings related to SD information provision satisfaction. Many participants were unhappy with the detail of information and felt uninformed and unprepared for the SD which had occurred. Analysis of data relating to age at treatment suggested that younger patients were more satisfied with information; this also suggests that clinicians provide more detailed SD information to patients who are 55 years of age and under. Further research is needed to confirm these findings.

A stronger negative reaction was recorded from questions relating to the information the participants received about the effect on their own psychological health and the effect on their relationships. Most participants felt uninformed about potential emotional, psychological problems and support pathways. Previous findings indicate that prostate cancer patients regard psychosocial changes to be as important as physical side effects, which can be at odds with clinician’s focus in discussions. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34 The resulting anxiety, psychological distress and depression Reference Sciarra, Gentilucci and Salciccia26 can themselves in turn lead to poorer sexual function outcomes. Reference Punnen, Cowan, Dunn, Shumay, Carroll and Cooperberg48

Many participant responses were also negative or neutral in relation to the provision of information regarding the effect of SD on their relationships. Relational issues and marital dissatisfaction caused by SD are well reported in relation to prostate radiotherapy patients. Reference Grondhuis Palacios, den Ouden, den Oudsten, Putter, Pelger and Elzevier9 Pinks et al. Reference Pinks, Davis and Pinks8 discussed a spectrum of issues which many partners of patients face after cancer treatment, with many partners feeling burdened with caring responsibilities, feeling unable to discuss issues caused by SD, a lack of information for partners about SD, and feeling overlooked and ignored by medical professionals. Both patients and partners require information Reference Mehta, Pollack and Gillespie10 but have different educational and informational needs Reference Bobridge, Bond, Marshall and Paterson5 which need to be addressed by medical professionals who are advising couples. Focusing on ED and not the patients’ wider psychosocial context, for example, relationship status, sexuality, willingness to adapt to SD, and how supportive their partner is, can reduce chances of rehabilitation. Reference Walker49

Side effects

This study showed that ED was the most commonly discussed sexual side effect, with other SDs caused by EBRT not explained to many participants. Failure to include all common side effects has been suggested as a cause of treatment regret and anxiety. Reference Christie, Sharpley and Bitsika46 Among these, abstinence from receiving anal sex for 2 months post-treatment was not mentioned to the five participants who answered the question. This triangulates with Nightingale et al. Reference Nightingale, Conroy, Elliott, Coyle, Wylie and Choudhury37 who reported a small proportion of men receiving this advice.

Participant suggested improvements

Although some participants were happy with the information they received, most participants who answered the free text question recommended improvement to provision of SD information. These data highlighted the strong desire of patients to receive this information before, during and after EBRT. The patient-led desire correlates with other studies into prostate patient support. Reference Kinnaird and Stewart-Lord34–Reference Downing, Wright and Hounsome36

Limitations

This study drew on a convenience-sample patient population who had all accessed post-treatment support groups. The findings, therefore, will not reflect the feelings of those patients who do not access support. Data have also not been received from patients without access to the internet. In addition, the sensitive nature of the topic may have reduced engagement, despite anonymity measures. Participants submitted their answers to the questionnaire retrospectively introducing a possible recall bias. Finally, the study questionnaire was a non-validated tool, and so the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of the tool have not been analysed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the overall quality of SD information provision to prostate radiotherapy patients is poor. Just under half (42·9%) of participants were not given any form of SD information. Furthermore, the information provided to prostate radiotherapy patients regarding radiation induced sexual side effects concentrated on ED and rarely included other SD issues. Physicians were the medical professional most involved with information provision with nurses and especially therapeutic radiographers underutilised. There was inadequate provision of information about impact on psychological health and relationships and also tailored information for those engaging in anal intercourse.

Medical professionals who are involved in the EBRT pathway before, during and after treatment should use these findings to improve SD information provision and ensure that patients are aware of all potential side effects of treatment. Frank discussion should include specific information about the full range of side effects and should be undertaken by a range of allied health professionals and nurses and include signposting to additional support. A concerted effort is needed to ensure that no patient goes through radical prostate EBRT without a clear understanding of how SD may affect them and their relationships.

Recommendations for practice

For physicians and consultant radiographers to discuss the wide range of radiation-induced SDs which may occur, as well as the personal psychological impact and impact on their romantic relationships, before allowing a patient to consent to radiotherapy to the prostate.

To train therapeutic radiographers as specialist SD health care professionals, who are ideally placed within the radiotherapy pre-treatment and treatment pathway to give SD information and advice before, during, and after radiotherapy treatment, to patients and their partners.

To further utilise specialist SD nursing staff and increase referrals to SD clinics.

To refer patients to specialist sexual counselling support and couples counselling for those who need further support.

Tailored SD information given to all patients who have anal intercourse

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the support group administrators and the study participants without whom it would not have been possible to complete this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.