Introduction

Native Americans in Indian Country (IC)Footnote 1 face unique challenges within the U.S. criminal justice system (Cardani Reference Cardani2009; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009). Despite being U.S. citizens, they are also citizens of their respective tribal nations. Federal policies, including the Major Crimes Act, have imposed limitations on tribal autonomy and hindered access to justice (Cardani Reference Cardani2009; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009; Snipp Reference Snipp1992; Ulmer and Bradley Reference Ulmer and Bradley2018). Indeed, tribal nations have limited jurisdiction over criminal offenses committed in IC, with primary responsibility of prosecuting major crimes resting with U.S. Attorney Offices (USAO) (Droske Reference Droske2007; Franklin Reference Franklin2013; Pommersheim Reference Pommersheim1991).

USAO possess considerable autonomy in determining whether to pursue federal prosecutions, a decision influenced by factors such as district size, resources, case evidence, and the severity of the offense (Boldt and Boyd Reference Boldt and Boyd2018; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2004). However, handling IC cases poses a unique challenge for USAOs due to tribal law enforcement agencies lack the resources and support (Luna-Firebaugh and Walker Reference Luna-Firebaugh and Walker2006). Tribal police, often the first responders in IC, face challenges of understaffing, leading to delayed response times and compromised crime scenes (Jones Reference Jones, Deer, Clairmont and Martell2008). This creates difficulties in gathering evidence and building a strong case, making it even more challenging for USAOs to prosecute IC cases and often leads to declination of IC cases (Crepelle et al. Reference Crepelle2022). Declination refers to the decision not to prosecute a case due to insufficient evidence or other factors.

Consequently, a concerning trend has emerged, where a significant proportion of crimes committed in IC go unprosecuted. In 2018, for instance, 40% of all federal IC cases ended in declination as USAO chose not to try these cases (United States Department of Justice, 2018). The significance of high declination rates becomes apparent when considering the alarming prevalence of violent crime in IC. Violent crime rates in IC are more than double the national averages (Alvarez and Bachman Reference Alvarez and Bachman1996; Dobie Reference Dobie2011), with some reservations reporting rates over ten times higher than the national average (Holder Reference Holder2014). Issues such as widespread rape, victimization of women, alarming levels of murder or disappearance of Indian women, and high rates of violent crime among Indigenous men and children further emphasize the impact (Deer Reference Deer2004; Dorgan et al. Reference Dorgan2014; Profile 2004). The high declination rates of IC cases by the federal judicial system allow perpetrators to victimize their tribal communities without facing legal consequences.

Research on the federal government’s handling of crimes in IC remains limited. Branton et al. (Reference Branton, King and Walsh2022) examine individual case outcomes of IC and non-IC cases, finding that criminal cases in IC are significantly more likely to be declined for prosecution compared to those outside IC. Crepelle et al. (Reference Crepelle2022) applied the “Ostrom-Compliant Policing” design principles for self-governing systems to address the unique challenges of policing in IC, offering a theoretical model for improving safety and justice through governance systems that empower tribes and respect their sovereignty. While insightful, their study does not provide an empirical analysis of the model. This study aims to build on the existing literature by examining whether and how tribal law enforcement factors influence declination rates of crimes in IC. Utilizing the “National Caseload Data,” this study identifies instances of crimes committed in IC and whether the USAO declined to prosecute the case. The findings indicate in the aftermath of the passage of the Tribal Law and Order Act (TLOA), tribes with larger law enforcement agencies and external funding to enhance their criminal justice system exhibit significantly lower rates of declination. TLOA was enacted to address high rates of violent crime and limited law enforcement resources by improving coordination between tribal, federal, and state authorities, and expanding tribal law enforcement resources.

Jurisdictional Landscape for IC Cases

In IC, jurisdictional issues regarding the prosecution of criminal cases are complex and multifaceted, arising from the interaction between tribal sovereignty, federal authority, and state jurisdiction. Each of these entities has its own set of rules and responsibilities, which contribute to what is often referred to as a “jurisdictional maze” (Cardani Reference Cardani2009). However, it is important to understand that this complexity is rooted in the foundational principles of tribal sovereignty, a core tenet of self-determination for many Indigenous communities. Tribal sovereignty is viewed by many as essential for maintaining control over their lands and preserving their cultural practices, and any system of prosecution must navigate this principle (Cardani Reference Cardani2009).

The “interlocking forms of institutional power” within the tribal, state, and federal criminal justice system often leads to confusion, delays, and the inability to resolve criminal cases that occur in IC (Ulmer and Bradley Reference Ulmer and Bradley2018). Further, the dual citizenship status of Native Americans—as both U.S. citizens and members of their tribes—makes them particularly vulnerable to these “interlocking forms of institutional power” (Steinman Reference Steinman2012; Ulmer and Bradley Reference Ulmer and Bradley2018). The jurisdictional landscape in IC is a direct result of four key policies: the Major Crimes Act (1885), Public Law 280 (1953), the Indian Civil Rights Act (1968), and Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978). These policies reflect the internal colonial dominance exerted by the federal government over tribes, resulting in a complicated and fragmented approach to criminal jurisdiction in IC (Pommersheim Reference Pommersheim1991; Steinman Reference Steinman2012; Ulmer and Bradley Reference Ulmer and Bradley2018).

First, the Major Crimes Act (1885) established federal jurisdiction over major crimes committed by Native Americans in IC.Footnote 2 This means if a Native American commits a major crime on tribal land, they can be prosecuted and punished by federal authorities. This created tension between tribal sovereignty and federal jurisdiction in criminal matters (Ulmer and Bradley Reference Ulmer and Bradley2018).

Second, Public Law 280 (1953) transferred jurisdiction over IC crimes from the federal government to state governments in Alaska, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wisconsin. In Public 280 states, tribes must navigate the state judicial system instead of the federal judicial system. This legislation created a process whereby some tribes (non-Public 280) are subject to federal jurisdiction, while other tribes (Public 280) are subject to state jurisdiction (Droske Reference Droske2007).

Third, the Indian Civil Rights Act (1968) further constrained tribal jurisdiction over criminal cases in IC, by limiting the penalties tribes can impose on criminal defendants. This policy served to further limit tribal sovereignty over criminal proceedings, constraining tribal nations from exercising their full sovereignty (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008).

Finally, the Supreme Court decision in Oliphant v Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978) limited tribal authority regarding crimes committed by non-Indians on IC almost completely. The decision served to divest tribal courts of the power to prosecute non-Indians who defy both tribal and federal law. Further, this decision has resulted in major crimes being left to the discretion of the USOA to prosecute, often resulting in superficial efforts to address the high rates of crime in IC (Riley Reference Riley2016).

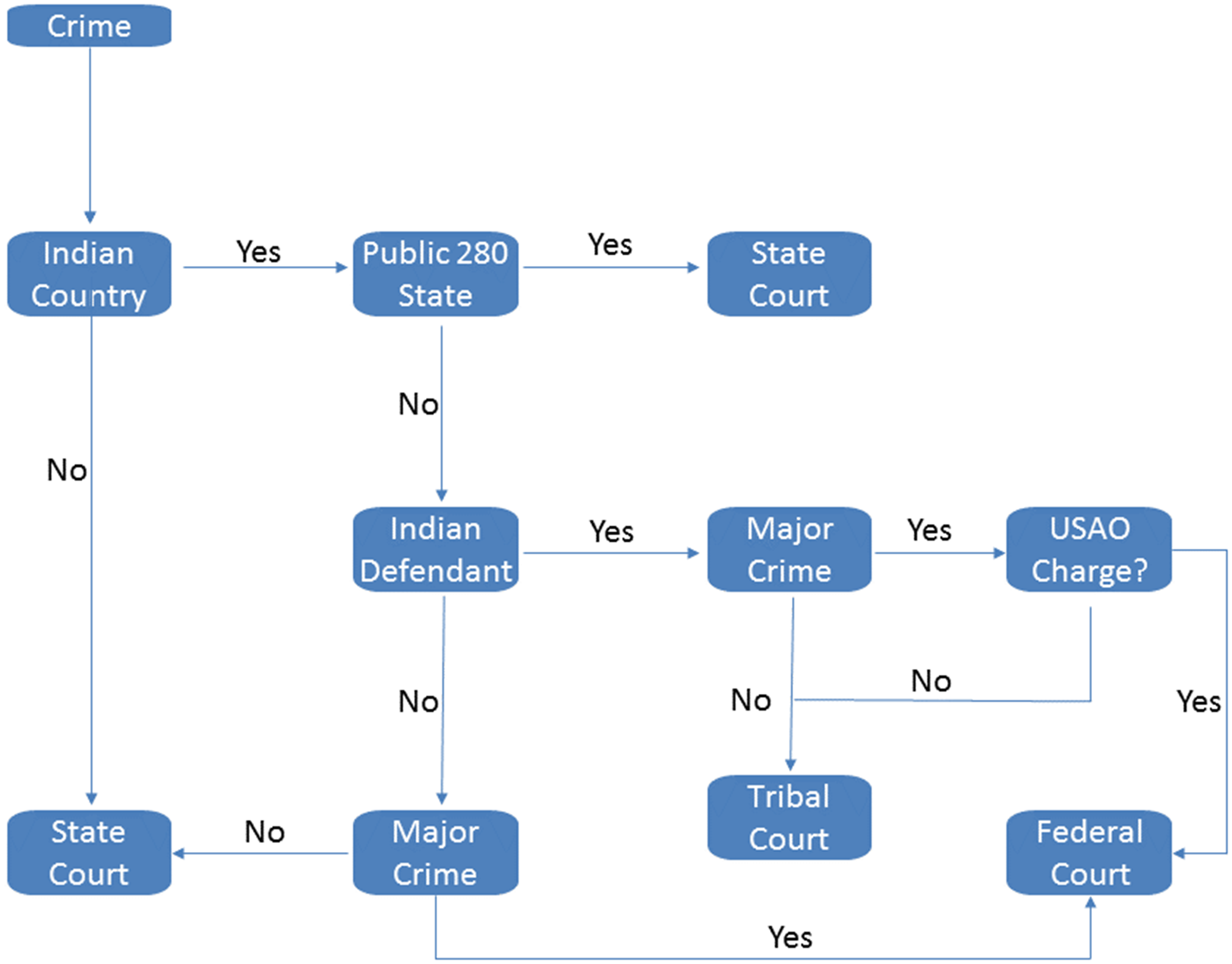

These policies have created a jurisdictional nightmare that often results in the declination of cases originating in IC.Footnote 3 In order to elucidate the impact of these policies on the processing of crimes in IC, consider the diagram in Figure 1, which delineates the complex web of jurisdictional authority that crimes in IC must navigate.

Figure 1. Jurisdictional landscape IC cases navigate.

The first step is to establish if the crime occurred in IC. If the crime did not occur in IC, it is typically under the jurisdiction of the state. If the crime occurred in IC, the next step is to determine whether it occurred in a Public 280 state (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). If the crime occurred in a Public 280 state, jurisdiction falls to the state judicial system (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). If the crime occurred in IC and in a non-Public 280 state, next it is necessary to determine if the alleged perpetrator is Native American (Reese Reference Reese2020). If the defendant is not Native American and the crime is not considered a “major” crime, jurisdiction lies with the state. If the defendant is not a Native American and the crime is considered a “major” crime, jurisdiction lies with the federal court. However, if the defendant is a Native American, the next determination is whether the alleged crime falls under the classification of a major crime (Reese Reference Reese2020). If the crime is not a “major crime,” jurisdiction typically rests with the tribe. If the crime is deemed a “major crime,” the federal government has jurisdiction and the USAO determines whether or not to prosecute the case (Reese Reference Reese2020). If the USAO decides to prosecute, the case is officially within the federal courts’ caseload. If the USAO declines to try the case, jurisdiction rests with the tribe. Given the limitations imposed by the Indian Civil Rights Act and the Oliphant decision, this limits the power of tribal nations to penalize non-Indian and Indian criminal defendants; thus, leaving the victim(s) without justice and perpetuates a system of unequal justice for tribal communities (Reese Reference Reese2020).

The Impact of Tribal Law Enforcement Capacity on Declination Rates

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 granted tribes the legal right to take on the responsibility of various programs that were previously administered by the federal government, including the right to establish their own police force (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). A 2018 Department of Justice report indicates there are 217 tribal nations with tribal law enforcement agencies with almost 3,800 full-time sworn tribal police officers providing services in IC (Gardner and Scott Reference Gardner and Scott2022). These officers are responsible for a variety of tasks, including examining crime scenes, executing arrest warrants, enforcing protection orders, serving process, and apprehending fugitives (Reaves Reference Reaves2011). The size of tribal police departments varies greatly, with the Navajo Nation in New Mexico having a force of 210 persons and the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe in Nevada with a very modest force of 1 full-time deputy, while many tribal nations lack a law enforcement agency altogether. This disparity highlights the diverse and complex nature of law enforcement in IC.

Tribal police are often the first law enforcement agents on crime scenes in IC (Crepelle Reference Crepelle2021; NCAI (National Congress of American Indians), 2014). This is largely due to the fact that IC is often located over a hundred miles away from non-Indian law enforcement agencies such as the FBI (Crepelle Reference Crepelle2021). Tribal police are thus tasked with interviewing victims and witnesses, detaining potential perpetrators, assessing the crime scene, and providing photographs of the crime scene. Yet, many tribes often lack modern technology such as 911 response systems, access to cell service, and limited car-radio services due to the rural nature of many tribal nations (Luna-Firebaugh Reference Luna-Firebaugh2007; Hill Reference Hill2009). Without reliable communication capabilities, there are often delays in the reporting of crimes. Further, as noted, tribal police departments are often under-staffed due to low levels of funding (Martin Reference Martin2014). As a result, response time to reported crimes can be hours or even days because these agencies have only a few officers to cover hundreds of miles (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). This means gathering evidence may be difficult as crime scenes can become compromised and witnesses may be difficult to locate (Jones Reference Jones, Deer, Clairmont and Martell2008). These factors make it difficult for tribal law enforcement when overseeing criminal investigations in IC (Crepelle et al. Reference Crepelle2022).

As noted, USAOs have significant discretion in deciding whether to pursue federal prosecutions, considering factors such as district size, available resources, case evidence, and the seriousness of the offense (Boldt and Boyd Reference Boldt and Boyd2018; O’Neill Reference O’Neill2004). However, USAOs face a distinct challenge when it comes to handling cases in IC due to the limited resources and support available to tribal law enforcement agencies (Luna-Firebaugh and Walker Reference Luna-Firebaugh and Walker2006). These challenges make it more difficult for USAOs to gather evidence and build strong cases, often leading to the declination of IC cases (Crepelle et al. Reference Crepelle2022).

Due to the challenges tribal law enforcement agencies face and the unique role they play in addressing crimes in IC, tribal law enforcement may have an impact on the declination rates of major crimes that occur in IC. It seems reasonable to expect the enhancement of the capacity of tribal law enforcement agencies could potentially lead to a reduction in the number of criminal cases that are declined in IC. Thus, this research note proposes heightened numbers of tribal officers may serve to reduce the rates of declination. A more fully staffed law enforcement likely results in more attention focused on crime, greater coordination with federal law enforcement investigations, and more thorough investigations of crime scenes. This may lead to fewer cases ending in declination. Formally stated:

H1: Increased tribal law enforcement staffing serves to reduce the rate of IC declinations.

The efficacy of law enforcement is contingent upon its efficiency and effectiveness, as demonstrated by the positive relationship between effective patrols and decreased illegal activity (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). However, the ability to manage law enforcement effectively is often hindered by insufficient financial resources (Wells and Falcone Reference Wells and Falcone2008). This issue is particularly pronounced in tribal law enforcement agencies, which are severely underfunded. The federal government consistently fails to provide basic levels of funding to IC police forces (Crepelle Reference Crepelle2021). Indeed, the United States Commission on Civil Rights (2003) reported tribal law enforcement agencies have between 55 and 75 percent of the resources available to non-Indian law enforcement agencies. For instance, many tribal police departments lack basic technology, such as laptops installed in police vehicles and cloud computing, which makes it even more difficult to access data and process crime scenes. This funding shortfall is especially concerning given that increased funding has been shown to significantly reduce crime in IC (Crepelle Reference Crepelle2021; NCAI, 2014).

Even when a tribal nation has a tribal police department, these agencies face numerous challenges, which are attributable to a lack of sufficient funding (United States Commission on Civil Rights 2018). State governments are unwilling to donate adequate resources to tribes or the federal government to enforce laws over which they have no jurisdiction to prosecute (Crepelle Reference Crepelle2021). Further, tribes have very limited monetary and personnel resources. Indeed, lack of police training and technology (Luna, Reference Luna1998; Luna-Firebaugh and Walker Reference Luna-Firebaugh and Walker2006), high turnover rates (Angell Reference Angell1981; Wood Reference Wood2002), low wages (Wood Reference Wood2002), and limited personnel (Luna-Firebaugh and Walker Reference Luna-Firebaugh and Walker2006; Wood Reference Wood2002) are among the most significant issues that impede their ability to effectively address crime and violence. According to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (2018), the insufficient level of funding for tribal police has contributed to high rates of violence in IC.

This research note proposes heightened support for tribal law enforcement efforts to control crime and administer justice may serve to reduce rates of declination. External funding provides resources necessary to train law enforcement officials and improve the criminal justice system. The funds are often used to train officers to address specific crime trends in their jurisdiction, purchase technology that assist with criminal investigations, and support prosecution programs. Although major crimes that occur in IC are handled through federal agencies such as the FBI, tribal law enforcement agencies are often the first line of contact on crime scenes in IC (NCAI, 2014). As such, they are vital in terms of initially managing all aspects of crime scenes (NCAI, 2014). This research note proposes the more professionalized the tribal law enforcement agency—tribal police with better funding, better training, and up-to-date technology—the more likely the cases are handled in a proper manner, which reduces the likelihood of declination. Formally stated:

H2: Increased external funding for tribal police serves to reduce the rate of IC declinations.

TLOA

TLOA, signed into law by President Obama in 2010, was designed to address the high rates of crime in IC by increasing federal accountability, enhancing tribal authority, and improving public safety. This was to be achieved through two key objectives: (1) by improving the recruitment and retention of tribal law enforcement officers, and (2) by promoting greater cooperation between tribal police and federal authorities. By doing so, the legislation aimed to reduce the number of cases that were declined due to investigative difficulties. Specifically, the legislation expands the authority of tribes to prosecute and punish criminals, while also enhancing efforts to train and retain tribal police officers. Additionally, the Act provides tribal police officers with greater access to criminal information sharing databases, which can aid in investigations. Altogether, the ultimate goal was and is to reduce crime rates in IC and to reduce rates of declination of cases emanating in IC. Thus, it seems plausible tribal law enforcement capacity may be more effective in reducing declination rates in the aftermath of the passage of TLOA. Stated formally:

H3: The capacity of tribal law enforcement increased after the passage of TLOA serving to reduce the rate of IC declinations.

Data and Methods

In order to assess the disparities in declination rates among tribal nations, the study employs the Executive Office for U.S. Attorney’s “National Caseload Data” from 2006 to 2020, which is archived at the United States Department of Justice. The “Legal Information Office Network System (LIONS)” is utilized to record detailed case information across all 94 U.S. District Courts. The “National Caseload Data” is organized by fiscal year, spanning from October 1 to September 30, and provides case-level data, with each observation representing a case being processed by the USAOs. To assess the variability in declination rates across tribal nations, using the “National Caseload Data,”Footnote 4 all tribal cases with a court ruling were identified and extracted from the original dataset. Next, this subset of cases was aggregated to the tribal level by year. For instance, in the original caseload dataset there were a total 225 cases entered into the LIONS system for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in North Dakota in the observed time period. After aggregating the data by year, there were the following observations for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians: 34 cases (2007), 23 cases (2008), 18 cases (2009), 16 cases (2010), 36 cases (2011), 15 cases (2012), 26 cases (2013), 24 cases (2014), 31 cases (2015), 16 cases (2016), 3 cases (2017), 1 case (2018), and 0 cases (2019 and 2020). To assess the impact of tribal law enforcement factors on decisions to decline IC cases, the tribe-level caseload data were merged with tribal law enforcement data. Note, the analysis includes crimes that occurred in non-Public 280 states where the jurisdiction rests with the federal government.Footnote 5

The dependent variable is the percentage of cases processed by USAOs that end in declination by tribal nation in each year from 2006 through 2020. The tribal-level declination rate ranges from 0 to 100%, with a mean of 39.43%.Footnote 6

The models include two primary variables of interest: Full-Time Officers and JAG Funding.Footnote 7 The Full-Time Officers measure is a count of the number of full-time sworn-in police officers with full arrest powers for each tribal law enforcement agency. The data were culled from the Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies (CSLLEA). The CSLLEA is a survey (2008 and 2018) that provides data on all state and local law enforcement agencies in the United States, including the number of sworn personnel by type of agency. The CSLLEA includes information for tribal law enforcement agencies. To make the measure comparable across tribes, the measure included in the model reflects the number of Full-Time Officers per capita (1000 residents), which ranges from 0 to 357.14 with a mean of 8.04 officers.

The JAG Funding measure reflects the level of funding each tribe received from the Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG). This is a program sponsored by the Bureau of Justice Assistance housed within the U.S. Office of Justice Programs, which is a branch of the U.S. Department of Justice. JAGs provide funding to state, local, and tribal governments for the purpose of supporting initiatives to aid criminal justice systems. The measure reflects the amount of funding per capita each tribe received during the observed time period. The rational for the inclusion of this measure is to account for efforts on the part of tribal nations to access funds to address crime in IC and to account for the level of support the tribes received to improve law enforcement in IC. The tribe-level per capita JAG measure ranges from 0 to 56.12 dollars, with a mean of 2.17 dollars. Note the correlation between the Full-Time Officers and JAG fundings is −.04, indicating there is little, if any, connection between the two measures.

To examine if there is a difference in USAO declination rates of tribe cases as a function of the passage of the TLOA, two additional models are estimated: before (2006–2010) and after the passage (2011–2020) of the TLOA. This approach offers the opportunity to determine if the passage of TLOA influenced the impact of Full-Time Officers and JAG Funding on the rates of declination of cases originating in IC. The expectation is that the impact of these law enforcement measures on declination rates is heightened in the aftermath of the passage of TLOA. As stated, the primary objective of the TLOA is to combat the high incidence of crime in IC by increasing federal accountability, empowering tribal authorities, and enhancing public safety. The legislation seeks to achieve this goal by promoting the recruitment and retention of law enforcement officers and providing additional resources to address critical needs. Specifically, the act expands the jurisdiction of tribes to prosecute and punish criminals, while also improving the training of tribal police officers. Furthermore, the act provides tribal police officers greater access to criminal information sharing databases, which can facilitate investigations and enhance overall effectiveness of tribal law enforcement.

The models also include case-level, US District Court (USDC)-level, and tribal-level control variables. First, the models include a case-level continuous variable reflecting the percentage of tribal cases in a given year that are violent in nature, Violent Crime. The percentage of violent crimes processed by tribe across each year ranges from 0 to 100%, with a mean of 57.28%. This measure is included to account for the proliferation of violent crimes in IC and the variability in violent crimes across tribes. The expectation is violent crimes may receive higher rates of declination than compared to non-violent crimes. As O’Neill (Reference O’Neill2004, p. 1475) notes:

“[i]t might be assumed that violent crimes, which place the life or safety of the public at risk, would more likely be pursued than minor property offenses. The data show prosecutors declined alleged violent offenses at a relatively high rate because of jurisdiction or venue problems.”

Second, the models also include two USDC-level variables: DC % GOP Judges and DC Caseload. The variable DC % GOP Judges represents the percentage of judges on each USDC in a given fiscal year who were nominated by a Republican President. The variable serves as a proxy for potential ideological influences on prosecutorial decision-making. Branton et al. (Reference Branton, King and Walsh2022) lend evidence that the partisan makeup of a USDC influences case-level declination rates. These data were obtained from the Federal Judicial Center’s “Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges” archive. The range of this measure is 16.67 to 100%, with an average of 62.85%.Footnote 8

The variable “DC Caseload” is a continuous measure representing the size of a USDC caseload per year, divided by the number of judges presiding over that court. This variable is used to reflect the caseload of the USDC that handles cases for a particular tribe. The size of a USDC’s caseload can have a significant impact on case processing and outcomes, with some courts handling only a few thousand criminal cases per year, while others handle over 130,000 cases annually (Hartley and Tillyer, Reference Hartley and Tillyer2018). Heavier caseloads can create pressures on USAOs, who must decide whether to continue investing resources in bringing a criminal case to trial. Overburdened USAOs may not be as effective in their efforts to prosecute cases (Shermer and Johnson, Reference Shermer and Johnson2010). We utilize caseload data culled from the “Federal District Caseload Statistics” report archives by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. The caseload measure ranges from 21 to 1455.67 cases per capita with a mean of 394 cases per capita.

Finally, the models include two tribe-level demographic control measures: Tribe % Poverty and Tribe Population. Poverty rates provide insight into tribal resource constraints, which could affect their capacity to address and process crimes. Population size serves as a proxy for the scale of law enforcement needs within a tribal community. Both measures are culled from the U.S Census the “American Community Survey” between 2006 and 2020. Tribe % Poverty is a continuous measure reflecting of the poverty rate on tribal land, which ranges from 0 to 100%, with a mean of 24.94%. Tribe Population is a continuous measure reflecting the size of the tribal population (per 10,000), which ranges from .001 to 80.01, with a mean of 2.76. Finally, the full model includes year dummy variables to account for any temporal variance in USDC declination rates.

Results

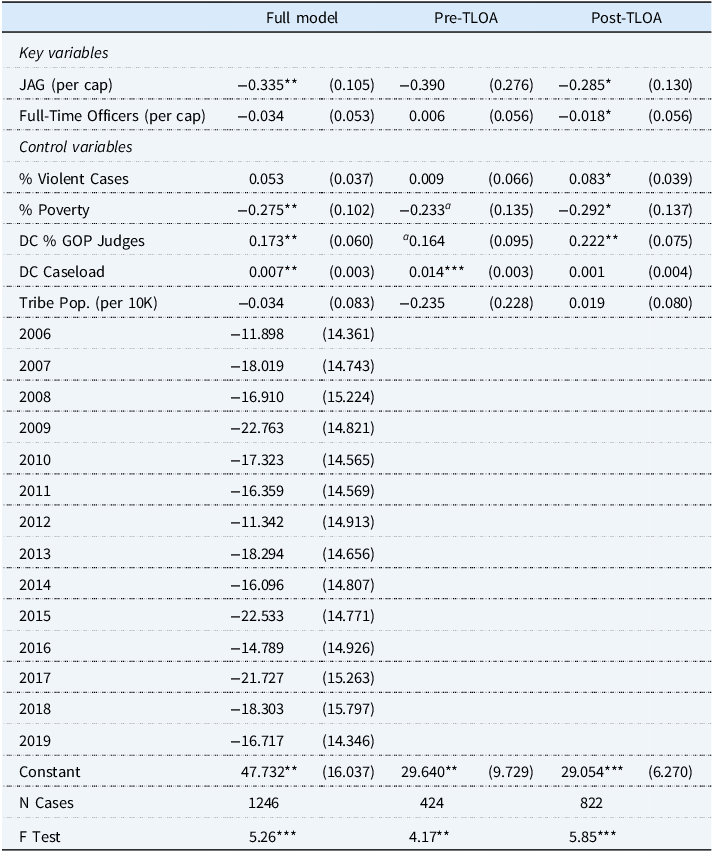

Given that the dependent variable is a continuous measure, OLS regression is used to estimate the models. The results are presented in Table 1. The first two columns contain the main model OLS coefficients and corresponding standard errors, the second two columns contain the pre-TLOA OLS coefficients and corresponding standard errors, and the last two columns contain the post-TLOA OLS coefficients and corresponding standard errors. The main model includes all cases decided between 2006 and 2020 to allow for the examination of differences of declination rates. The pre-TLOA model includes all cases decided between 2006 and 2010, while the post-TLOA model includes all cases decided between 2011 and 2020.

Table 1. USAO declination rates of tribal cases

a*p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Coefficients are OLS regression coefficients with standard errors clustered on tribe. Standard errors in parentheses.

First, we examine the “full” model, in which the two key variables of interest are Full-Time Officers and JAG Per Capita. The results reveal there is no significant relationship between the size of a tribe’s law enforcement and the declination of federal criminal cases in IC. This outcome fails to support H1. However, the findings do indicate a negative and significant relationship between the declination of criminal cases and JAG funding, which provides support for H2. Substantively, the results demonstrate declination rates decrease significantly as access to external funding for supporting criminal justice efforts in IC increases. Specifically, as JAG funding (per capita) rises from its minimum to maximum value, the declination rate drops from 40.16% to 21.36% (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −18.81%). This finding suggests tribal nations that successfully secure JAG grants experience lower declination rates than those without JAG funding.

${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −18.81%). This finding suggests tribal nations that successfully secure JAG grants experience lower declination rates than those without JAG funding.

Second, we examine the “Pre-TLOA” model, which pertains to cases filed between 2006 and 2010, prior to the implementation of TLOA. Notably, the findings reveal there is no statistically significant relationship between either Full-Time Officers or JAG Per Capita and the rates of declination at the tribal level. Collectively, these outcomes imply the magnitude of law enforcement and external funding does not appear to be linked to the rates of declination among tribes in the “Pre-TLOA” time period.

Finally, we turn to the “Post-TLOA” results, which includes cases filed between 2011 and 2020, after TLOA was implemented. The findings indicate there is a significant relationship between the size of a tribe’s law enforcement and tribal external law enforcement funding and the declination rate of federal criminal cases in IC. Specifically, the analysis shows as the number of Full-Time Police Officers (per capita) increases from minimum (0) to maximum (7.72), the declination rates decrease from 39.49% to 8.99% (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −30.49%), which lends support for H1. Similarly, as the number of JAG Per Capita increases from minimum to maximum value, the declination rate decreases from 39.30% to 23.33% (

${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −30.49%), which lends support for H1. Similarly, as the number of JAG Per Capita increases from minimum to maximum value, the declination rate decreases from 39.30% to 23.33% (

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −15.97%), which lends support for H2. Contrary to the pre-TLOA findings, the post-TLOA findings suggest tribal nations with a larger law enforcement presence and tribes that secure external funding to bolster their criminal justice system experience lower declination rates. Unlike the pre-TLOA results, the post-TLOA results lend support for H1 and H2. Further, the findings lend support for H3 suggesting there is a greater difference in the impact of these law enforcement indicators on declination rates after the implementation of TLOA.

${\rm{\Delta }}$

= −15.97%), which lends support for H2. Contrary to the pre-TLOA findings, the post-TLOA findings suggest tribal nations with a larger law enforcement presence and tribes that secure external funding to bolster their criminal justice system experience lower declination rates. Unlike the pre-TLOA results, the post-TLOA results lend support for H1 and H2. Further, the findings lend support for H3 suggesting there is a greater difference in the impact of these law enforcement indicators on declination rates after the implementation of TLOA.

Conclusions

This study underscores the positive impact of the TLOA on the criminal justice system in IC. The findings indicate the relationship between tribal law enforcement capacity, external funding and declination have evolved over time. Specifically, in the pre-TLOA period, neither tribal law enforcement capacity nor access to external resources had a significant relationship with declination rates. However, in the post-TLOA period both tribal law enforcement capacity and external funding are associated with declination rates. This shift suggests the reforms introduced by the TLOA bolstered the effectiveness of tribal law enforcement agencies, reducing declination rates, and addressing disparities in the justice system. Reforms such as enhanced capacity, improved access to funding, expanded jurisdiction and authority, and enhanced transparency have contributed to lower declination rates. The results emphasize the need for sustained investment in and support for tribal law enforcement to ensure more equitable justice in IC.

The findings hold significant implications for policymakers and tribal leaders who are committed to enhancing the criminal justice system in IC and reducing declination rates. By identifying the factors that contribute to these disparities, policymakers and tribal leaders can work towards implementing effective solutions that address these issues and ensure justice is served for all individuals in the community. Based on this study, it seems imperative that tribal nations seek to increase the capacity of their law enforcement agencies. Tribal police serve as the first line of defense and thus play an important role in processing crimes in IC. Growing tribal police forces and supplementing existing funding can serve to reduce the rates of declination, which may lead to lower rates of violent crime in IC over time.

It is essential that any expansion of tribal law enforcement capacity should emphasize a balance between opportunities and risks associated with federal involvement. Expanding tribal law enforcement capacity may lead to increased interaction and collaboration with federal agencies, which could improve responses to crime and bolster community safety. However, it may also increase concerns surrounding tribal autonomy and the risk of federal justice approaches conflicting with tribal values (Deloria and Lytle Reference Deloria and Lytle1983). Partnerships with federal agencies provide access to training, funding, and technology, which are instrumental in equipping tribal police to address serious crimes effectively. However, heightened federal presence often brings concerns of stricter policing and increased federal oversight, which may further erode tribal sovereignty (Deer Reference Deer2015). Moreover, many indigenous communities prioritize restorative justice practices over punitive approaches—a value that often contrasts with prosecution-driven federal justice system (Riley Reference Riley2016). Given these perspectives, increased federal involvement must be approached thoughtfully to avoid deepening distrust and tension on tribal lands.

Future research should explore the factors that influence tribal nations’ ability to secure external funding to bolster law enforcement capacity. Likely determinants include tribal population size, economic resources, geographic location, administrative capacity, pre-existing relationships with federal agencies, and alignment with federal funding priorities. Investigating these dynamics can help identify strategies to ensure equitable distribution of resources and further address the challenges of crime in IC.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.34

Competing interests

The author does not have any competing interests to declare.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any financial support.