Introduction

Since the dawn of human civilization, migration has been a cornerstone of socioeconomic activity, driven by humanity’s enduring quest for survival, improvement, and opportunity. From the pursuit of necessities like food, water, and shelter to the hope for a better future, migration embodies adaptation, transformation, and resilience. For those embarking on this journey, leaving behind their homeland entails more than just physical relocation, it demands a profound adjustment in all aspects of life, from daily routines to legal challenges.

Against the backdrop of global mobility, Egyptians have increasingly looked to Europe, particularly Italy, as a destination since the early 1970s (Zohry Reference Zohry2009). Italy’s allure—rooted in its cultural proximity, economic opportunities, and promises of freedom and justice—has made cities like Milan focal points for Egyptian migration. Milan now hosts a substantial Egyptian population, encompassing diverse social strata, regions (rural and urban, lower and upper Egypt), and economic classes. Egyptians predominantly identify as Sunni Muslims (approximately 90%) and Coptic Orthodox Christians (around 10%), reflecting Egypt’s religious composition (Central Intelligence Agency 2024). While Egyptian Muslims and Coptic Christians share a strong sense of ethnic identity rooted in language and cultural traditions, their religious practices face distinct challenges. Muslims encounter Islamophobia tied to global narratives, while Copts face invisibility as a minority group perceived as ‘non-European Christians (Pierce Reference Pierce2016).

Egyptian ethnicity is characterized by a profound linking of religious and cultural traditions, where both Islam and Coptic Orthodox Christianity are central pillars. These faiths not only represent spiritual frameworks but also shape social practices, communal rituals, and shared histories that reinforce a sense of belonging. For Egyptians, ethnicity is as much about these shared cultural and religious markers as it is about geographic origins, reflecting an enduring connection between identity and faith.

For Egyptians in Milan, religion plays a dual role as both a spiritual anchor and an essential marker of ethnic identity, weaving together the threads of community cohesion and cultural heritage in the diaspora. However, whether Islam or Coptic Orthodox Christianity, presents significant challenges (Urso and Bonilla Reference Urso and Bonilla2023). This study examines the everyday realities of the Egyptian minority, focusing on obstacles related to religious practices, access to places of worship, cemeteries, taxation, financial support, religious education, and work-related issues such as holidays. The exclusion of their religious practices in public and institutional spaces not only disrupts their spiritual lives but also erodes their ability to express and preserve their ethnic identity, further marginalizing them within Italian society.

By sitting these experiences within the broader context of European identity, this article reveals how systemic exclusionary practices are rooted in historical and policy frameworks. It seeks to refine academic understanding of Egyptian migration and provide a platform for recognizing their struggles. In highlighting these tensions, the study demonstrates how religious exclusion is intrinsically tied to ethnic marginalization, challenging the ideals of multiculturalism and inclusion often claimed by European societies. In an intersected world, addressing these issues is essential for raising inclusion, understanding, and shared experiences that outdo boundaries.

Methodology

This ethnographic study utilized participant observation, two focus group discussions, and around 50 in-depth interviews with Egyptians in Milan, conducted from 2019 to 2023. Participants had been living in Italy for varying durations, ranging from 1 year to over 20 years. Most participants were either permanent residents or held Italian citizenship, which minimized potential risks and allowed them to share their experiences openly. Recruitment primarily occurred during community gatherings, religious events, and through connections with local leaders, such as Anba Gabriele and mosque Imams, who provided verbal consent for the interviews. Informal interactions formed the basis of much of the data collection, supplemented by formal interviews.

The study included two focus group discussions, each comprising approximately 6–10 participants. One focus group was conducted with women attending an Italian language course for newcomers at the Islamic Community Fajr-Comunità, while the other consisted primarily of men. Participants ranged across all age groups, and the study represented members of both Muslim and Coptic Orthodox Christian communities. This diverse sample allowed the research to explore how Egyptians navigate their religious practices and identities in a context where their religion lacks formal recognition by the Italian state and where restrictive policies make public religious expression challenging.

To comprehensively address these complexities, the study draws on Meredith McGuire’s (Reference McGuire2008) concept of lived religion and Nancy Ammerman’s (Reference Ammerman2021) framework of social practices and cultural contexts. McGuire’s framework (Reference McGuire2008) was essential for understanding how Egyptians adapt their religious practices outside formal institutions, given that state policies limit their access to recognized religious spaces. Her focus on “everyday lived religion” permitted the research to capture how individuals practice their faith in private and informal settings, such as homes, family gatherings, and small community groups. This lens was particularly useful in documenting how personal religious expressions are shaped by a lack of institutional support, highlighting the creativity and resilience of individuals in sustaining their religious practices through embodied, everyday actions.

At the same time, Ammerman’s approach (Reference Ammerman2020; Reference Ammerman2021) to “social practices”, rooted in practice theory, provided a perspective on how the Egyptian community collectively organizes its religious life. Drawing on practice theory, Ammerman emphasizes the repeated, embodied, and contextual actions through which individuals and communities construct and express their religious lives. Her framework shifts attention from abstract doctrines or institutionalized religion to the everyday lived experiences, rituals, habits, and interactions that give religion its tangible form. These practices are embedded in cultural and social contexts, shaped by both individual agency and collective actions. These complementary approaches provided a broad view of how personal adaptations and community resilience sustain religious practices despite the legal and cultural barriers they face. Also, these perspectives enabled the analysis of how the Egyptian community in Milan navigates its unrecognized status through informal networks, digital spaces, and community-led religious events.

Data collection involved open, informal discussions with participants during observations and focus groups. No written consent was required, as participants were aware of the research context and willingly engaged in conversations. The researcher maintained a reflexive approach, noting insights from interactions without audio recordings or formal data storage. Thematic analysis was conducted based on notes taken during and after these discussions, allowing for an understanding of recurring themes related to religious practices, identity, and community dynamics over the 4 years. Ethically, the study operated under the principle of “do no harm”. As suggested by Jacobsen and Landau (Reference Jacobsen and Landau2003) and Mackenzie, McDowell, and Pittaway (Reference Mackenzie, McDowell and Pittaway2007), participants were aware of the informal and observational nature of the research, and there were No formal issues or concerns raised during the study. The discussions took place in a respectful and open environment, and participants were free to share as much or as little as they wished. No sensitive data was collected or stored, ensuring that confidentiality was maintained.

European Identity and the Marginalization of Minorities

This section explores the discussion surrounding European identity, drawing insights from scholars like Talal Asad, Edward Said and Nelson Maldonado-Torres. Talal Asad’s (Reference Asad2003) discourse on Muslims in Europe, specifically addressing the notion of minorities, sheds light on the many-sided identities that come to the fore in a modern, secular era. “‘Modern’ is used here to describe the post-Enlightenment era of secular nation-states and industrialization, characterized by the dominance of Western political and cultural ideals (Giddens Reference Giddens1990; Asad Reference Asad2003).” He raises effective questions about the acceptance of these diverse identities and the challenges faced by Muslims, often misrepresented in media and at times subject to discrimination. He elaborated in his book Formations of the secular: Christianity, Islam, modernity, more about the conflict of identities, said:

“Muslims are clearly present in a secular Europe and yet in an important sense absent from it. The problem of understanding Islam in Europe is primarily, so I claim, a matter of understanding how “Europe” is conceptualized by Europeans. Europe (and the nation-states of which it is constituted) is ideologically constructed in such a way that Muslim immigrants cannot be satisfactorily represented in it. I argue that they are included within and excluded from Europe at the same time in a special way and that this has less to do with the “absolutist Faith” of Muslims living in a secular environment and more with European notions of “culture” and “civilization” and “the secular state,” “majority,” and “minority.” —(Talal Asad, Reference Asad2003, 159).

Drawing from Asad’s assertion that identity relies on the recognition of the self by the other, we dig into the discourse of European identity. This discourse, a manifestation of concerns about non-European elements, reflects anxieties and aspirations surrounding the representation and impact of modern civilization. Edward Said’s (1987) exploration of Orientalism further underlines the relationship between knowledge and imperial power, reflecting how knowledge has historically been utilized to dominate and subjugate. Building on the Orientalism, both Muslims and Coptic Orthodox Christians from Egypt are subject to processes of othering in Europe. While Orientalism often focuses on Islam as the primary marker of Eastern difference, Coptic Christians, despite their shared Christian faith, are not incorporated into the Western Christian narrative. As Edward Said argues in Covering Islam (Reference Said1981), Western media often depicts Islam as a monolithic entity inherently at odds with Western values. This narrative reinforces exclusionary policies that frame Muslim migrants as cultural threats. In the context of Fortress Europe, these portrayals contribute to the marginalization of Egyptian Muslims, while also homogenizing the broader Egyptian identity as ‘non-European’. Such dynamics obscure the diversity within Egyptian communities, including Coptic Christians, and perpetuate systemic exclusion. “The term ‘Western’ refers to societies shaped by Enlightenment ideals and colonial legacies, often contrasted with ‘Non-Western’ regions historically constructed as the ‘Other.’” (Hall Reference Hall, Hall and Gieben1992; Said Reference Said1978)

To deepen this discussion on European identity, Nelson Maldonado-Torres’ (Reference Maldonado-Torres2007) concept of “coloniality of being” provides a critical framework for understanding the complex relationship between migrants and Europe. He argues that coloniality extends beyond political or economic systems of domination and infiltrates the very ontology of modernity, the way being and subjectivity are constructed. His analysis shows how the colonial gaze dehumanizes non-European populations by framing them as inherently inferior, even within ostensibly democratic and secular societies. As a result, Muslim immigrants, like those described by Talal Asad, are simultaneously present and absent in Europe. They are included as participants in society yet excluded from full recognition due to lingering colonial structures that define European identity. In this way, the coloniality of being reveals how religious minorities continue to be ontologically marginalized, even as they physically reside in European spaces, reinforcing their position as the “Other”.

This positive correlation between secularization and security rests upon a flawed understanding of religion, European history, and the emergence of the modern nation-state (Asad Reference Asad2003; Mavelli Reference Mavelli2012). The power and security of European states have ushered in a new era of the welfare state. However, defining this power and understanding its extent of exploitation remains a challenge. Describing power as an essence or a range of attributes, such as size, population, and resources, Karen Smith (Reference Smith2003) raises the question of its utilization. Although European size and resources grant it a certain level of power and the potential for enhanced security, the actual exercise of this power remains critical. Maldonado-Torres (Reference Maldonado-Torres2007) highlights the continuity of colonial power even after the dissolution of formal colonial empires. Coloniality refers not only to political control but to a hierarchical system of power that continues to shape global relationships, particularly between Europe and non-European peoples. It manifests in the institutional and cultural frameworks that prioritize European values while relegating non-Western identities to positions of subordination. This power operates through racialization, the dehumanization of non-European peoples, and the preservation of European dominance in global affairs. His conception of coloniality as power reveals how Europe’s post-colonial identity still rests upon structural inequalities, which sustain its economic and political influence. These forms of power, though no longer explicit, are implanted in the logic of modernity, continuing to influence migration policies, citizenship, and the way minorities are perceived within European nations.

However, Talal Asad (Reference Asad2003) emphasizes that modern Europe’s political representation ideology does not include the Muslim minority. The limitation arises from European democratic states being defined by commonalities among their citizens, omitting the specificities of Muslims. This may partly explain why Islamic and Egyptian minorities in Italy are often marginalized politically and socially. Similarly, media coverage plays a pivotal role in shaping perceptions about migration and minorities. Some studies stated that up to 90% of coverage of Muslim populations in Western countries carries a negative bias (Saeed Reference Saeed2007; Byng Reference Byng2010; Taras Reference Taras2012; Nielsen and Otterbeck Reference Nielsen and Otterbeck2016). Asad’s hypothesis of European identity finds great popularity among many academics and specialists, chiefly when they examine the facts that relate the minorities—in some cases communities—to modern Italian cultures as food (Ferrara Reference Ferrara2011; Mescoli Reference Mescoli2015; Chiodelli Reference Chiodelli2015), Languages (Gale Reference Gale2013), traditions (Mescoli Reference Mescoli2015), religious practice (Zanfrini and Bressan Reference Zanfrini and Bressan2020), religious sub-groups (Roman, and Goschin Reference Roman and Goschin2011; Gallo, and Scrinzi Reference Gallo and Scrinzi2019; Sündal Reference Sündal, Giordan and Pace2012), customs (Beasley Von Burg, and Adam 2010; Minganti Reference Minganti, Moors and Tarlo2013; Menin Reference Menin2011), and public spaces appearance (Zhang, Gereke, and Baldassarri Reference Zhang, Gereke and Baldassarri2022).

Aside from taking up rigid anti-immigration stances, Italy has also joined efforts to establish a “fortress Europe” a term describing conservative political agendas regarding immigration. Parati (Reference Parati2005) defined “fortress Europe” as a political entity striving to shield itself from perceived threats posed by migrants, who are often viewed as endangering national cultures. While migration is inherently a global phenomenon, it defies attempts to reinstate or preserve national identities through rhetoric aimed at guarding against external influences. Cardinal Biffi’s statement in 2000, advocating for Italy to restrict immigration to Catholics to preserve its identity, reflects a linear and homogeneous perspective of Italy’s history. This viewpoint is pervasive within the political landscape, even though it is frequently challenged. In recent times, immigrants have been subjected to hostile political rhetoric, particularly following the electoral victories of right-wing parties in the Italian parliamentary elections of 2018 and 2022 (Gerstlé and Nai Reference Gerstlé and Nai2019).

Moreover, the recognition of “other” religions within the European context poses a significant defiance to the fortress mentality perpetuated by conservative political agendas. Maldonado-Torres argues that the “Other” in Europe, particularly religious minorities, remains trapped within a system of coloniality that perpetuates their exclusion. He explains that coloniality not only dehumanizes but fundamentally denies the being of non-European populations, stating, “coloniality of being would make primary reference to the lived experience of colonization and its impact on language and existence” (Maldonado-Torres Reference Maldonado-Torres2007, 242). This resonates with how Muslims and Coptic Orthodox Christians are perceived as threats to a unified European identity, rather than as fully recognized members of society. True recognition of these Others would require dismantling this mentality and embracing a decolonial approach that validates their existence. Granting rights and recognition to religious minorities challenges the narrative of a homogenous European identity under threat from external forces (Lipka Reference Lipka2017). This shift towards inclusivity and recognition acknowledges the diversity inherent in European societies, disrupting the notion of a monolithic cultural entity. Conversely, this acknowledgement also raises concerns among proponents of fortress Europe, who fear that such recognition may dilute or undermine the dominant cultural and ideological frameworks. Thus, the tension between embracing diversity and maintaining a fortress mentality stresses the complexities inherent in Europe’s evolving relationship with religion and migration. Public discourse and media representations further perpetuate this reductionist view by emphasizing religious affiliations over ethnic identity (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou, Modood, Triandafyllidou and Zapata-Barrero2006). Egyptian Muslims are frequently portrayed through the lens of security concerns, while Copts are relegated to the category of ‘Eastern Christians,’ distinct from the dominant Italian Catholic identity. This framing erases their broader cultural contributions and reinforces their marginalization.

Said (Reference Said1981) emphasizes the role of media in shaping perceptions of Islam as an oppositional force, which feeds into broader narratives of European identity. These narratives rely on ‘othering’ minorities, including Egyptians, to define Europeanness as secular, Christian, and modern. Such framing marginalizes both Egyptian Muslims and Coptic Christians, aligning with broader colonial legacies of exclusion. Evolvi’s (Reference Evolvi, Conrad, Hálfdanarson, Michailidou, Galpin and Pyrhönen2023) qualitative textual analysis of Matteo Salvini’s tweets, as a representative of Italy’s right-wing Lega Nord party, went into the hateful narratives and emotions espoused. Her research shed light on the term “post-truth”Footnote 1 politics and the utilization of religious discourse to foster nativist sentiments. Her analysis of Salvini’s tweets revealed a strategic emphasis on Christianity, Islam, and Judaism to advance his political agenda. Salvini, in this context, serves as a reflection of Italy’s political environment and an embodiment of the ongoing ideological struggle between right-wing and left-wing factions (Dennison and Geddes Reference Dennison and Geddes2021). Right-center parties have prioritized safeguarding what they label as “Judeo-Christian”Footnote 2 history and heritage, a sentiment prominently expressed in Salvini’s speeches and tweets. These communications also intensely oppose immigration, particularly by non-Christian migrants, often framed as threats to “Western” civilization. This perspective is associated with Asad’s notion of exclusion, proving how Italian politicians align with the exclusion of culturally “other” entities, particularly those with Muslim or non-western backgrounds.

In this article, we critically examine intriguing questions regarding the self-definition of migrant communities, particularly exploring the culture that shaped their identity. The exclusionary dynamics of Fortress Europe, reinforced by secularism and coloniality, profoundly affect the everyday lives of Egyptians in Italy, especially in contexts where their religions—Islam and Coptic Orthodox Christianity—lack legal recognition. Both groups face challenges in terms of institutional recognition and public acceptance, albeit in distinct ways. For Muslims, restrictions on building mosques and the lack of permission for religious holidays reflect broader struggles with public acknowledgment. Similarly, for Coptic Orthodox Christians, the absence of recognition for community-specific practices and traditions limits their ability to fully express their faith. Both groups also face challenges in religious education and taxation, as their organizations struggle to secure financial support or exemptions afforded to recognized religious institutions. These barriers reinforce their marginalization and restrict their ability to participate fully in public and social life. By addressing these dynamics, the article highlights how the absence of legal recognition for religion serves as a mechanism of marginalization, shaping the struggles and lived experiences of Egyptians in Milan.

Background: Italy’s Journey with Religion and Recognition

The relationship between Europe and religions has been a dynamic and evolving one throughout history. From the dominance of Christianity during the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment period, where secularism gained prominence, Europe has experienced shifts in its approach to religion. Additionally, events such as the Protestant Reformation and the rise of religious diversity have influenced this relationship. In recent times, debates surrounding issues like immigration, multiculturalism, and the role of religion in public life have further shaped the dynamic between Europe and its diverse religious communities. This evolving relationship reflects Europe’s journey towards religious tolerance and diversity (Barker Reference Barker2009).

The concept of multiculturalism is essential in understanding the complex and evolving relationship between Europe and its religious communities. At its core, multiculturalism is about embracing the coexistence of various cultural, ethnic, and religious identities within a society. In modern Europe, this idea has become particularly relevant as migration, especially from Muslim-majority countries, has brought religious diversity to the forefront. This has sparked important debates about how societies can accept and integrate these communities while ensuring equality and inclusion (Burg and Beasley Reference Burg, Beasley and Luedtke2020). As Modood et al. (Reference Modood, Triandafyllidou and Zapata-Barrero2006) argue, multiculturalism challenges traditional views of national identity by encouraging policies that allow minorities to practice their faith freely while still participating fully in public life. However, this isn’t without its tensions. For example, in Italy, the ongoing mosque debate reflects how multiculturalism and laïcité intersect, raising difficult questions about religious freedom in public spaces (Triandafyllidou and Magazzini Reference Triandafyllidou and Magazzini2020). The Italian mosque debate, centered around the 2000 controversy surrounding the construction of mosques in Lodi and Milan, provides a critical lens into the country’s evolving understanding of multiculturalism. Triandafyllidou (Reference Triandafyllidou, Modood, Triandafyllidou and Zapata-Barrero2006; Reference Triandafyllidou2011; Reference Triandafyllidou2012) analyzes the public discourse surrounding these events, revealing a complex interplay of factors. While some advocated for religious freedom and civic values, others emphasized the preservation of “Italian traditions” and expressed anxieties about cultural change. Her analysis highlights the underrepresentation of Muslim voices and the politicization of the issue, with political parties utilizing the mosque debate for electoral gain. The findings suggest a limited acceptance of religious diversity in Italy, characterized by underlying anxieties about national identity and cultural homogeneity. This limited acceptance could have significant implications for the Muslim community, potentially hindering their full integration and contributing to feelings of marginalization. Furthermore, the politicization of multiculturalism can exacerbate social divisions and hinder the development of more inclusive and equitable societies.

These changes have reached a point where religious diversity is now one of the landmarks and indicators of modern Europe. In this context, the concept of laïcité or laicismo adds another layer to the discussion on the relationship between Europe and religions. Defined as the “religious neutrality of public institutions” (Dutta Reference Dutta2019), laïcité ensures that these institutions remain impartial and inclusive. It is essential for safeguarding equal religious freedom and social dignity for all citizens, irrespective of their beliefs or non-beliefs. By emphasizing the need for public institutions to remain religiously neutral, laïcité allows individuals to practice their faith or choose not to, without facing discrimination. This principle extends beyond state-church relations, encompassing the values and duties of a plural and democratic society where religion holds its place alongside other components of civil life.

Italy’s relationship with religion has been shaped by its unique historical and political developments. The unification of Italy in 1861 marked a critical turning point, as the new state was established in opposition to the Catholic Church, leading to an anticlerical stance that became a defining feature of its early political identity. This tension escalated with the occupation of Rome and the expropriation of ecclesiastical properties, which deepened a fracture in the nation’s collective conscience. As Italy moved forward, it embraced laicismo, a concept influenced by the French model of laïcité, which advocated for the religious neutrality of public institutions. The nineteenth-century Italian liberals viewed the strict separation of state and religion as essential for political and economic modernization. They implemented measures such as compulsory civil marriage, restrictions on Catholic religious education in state schools, and state control of welfare institutions. War I and the subsequent social conflicts paved the way for the rise of the Fascist regime. However, these policies faced opposition from the Catholic Church hierarchy, leading to tensions that persisted into the twentieth century (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2011). Italy’s participation in the first World War and the subsequent social conflicts paved the way for the rise of the Fascist regime in 1922 (Ferrari Reference Ferrari2010).

Mussolini’s government addressed the “Rome issue” with the Lateran Treaty in 1929, recognizing Catholicism as the official religion of the state and establishing a concordat with the Catholic Church. This historical setting underscores the complex interplay between religion, politics, and society in Italy’s journey toward modernization and secularization.

However, as Alicino (Reference Alicino2022) highlights, laïcité has sometimes been interpreted restrictively in Italy, particularly affecting Muslim communities. In the context of heightened fear and insecurity, particularly post-9/11, legal measures aimed at protecting neutrality have occasionally marginalized Muslim religious practices under the guise of national security. This has led to uneven applications of laïcité, where instead of ensuring religious neutrality, it has sometimes been used to limit Muslim visibility, thus contradicting its original purpose. Alicino argues for a more inclusive interpretation of laïcité, one that truly upholds neutrality while protecting the rights of all religious communities, especially minorities like Muslims, to foster social cohesion and democratic values.

The legal transactions of religions appear in two different forms de jure (the legal form) and de facto (the practical): the first is in what is stipulated in the Italian Constitution, and the other is in the laws and government transactions. The Italian Constitutional Framework safeguards religious freedom at both individual and community levels. At the individual level, Article 19 ensures that everyone has the right to freely profess their religious beliefs and practice their religion, while also protecting religious associations from discrimination based on their religious character, as outlined in Article 20. Article 3 further establishes the equality of all citizens without distinction of religion. On the community level, Articles 7 and 8 regulate the relationship between the state and religious institutions. Article 7 acknowledges the independence and sovereignty of the state and the Catholic Church within their respective spheres, while Article 8 ensures equal freedom for all religions. These articles uphold the principle of religious autonomy, requiring the state to reach agreements with religious organizations through concordats or bilateral agreements, as specified in the Italian Constitutional Framework. This framework provides a legal basis for managing religious diversity in Italy while respecting the principles of freedom and equality (Pin Reference Pin2017).

De facto, the practice of state-church relations and the implementation of the law, combined with the highly discretionary powers granted to the government, can lead to unreasonable and discriminatory distinctions between, on one hand, religions that benefit from bilateralism and, on the other hand, confessions that not only are excluded from this benefit but also are sometimes not even legally recognized as religions. These distinctions create de facto disparities in treatment, potentially violating the principles of equal treatment under the law. However, de jure, or legally recognized distinctions, may not always reflect the realities of how religions are treated in practice.

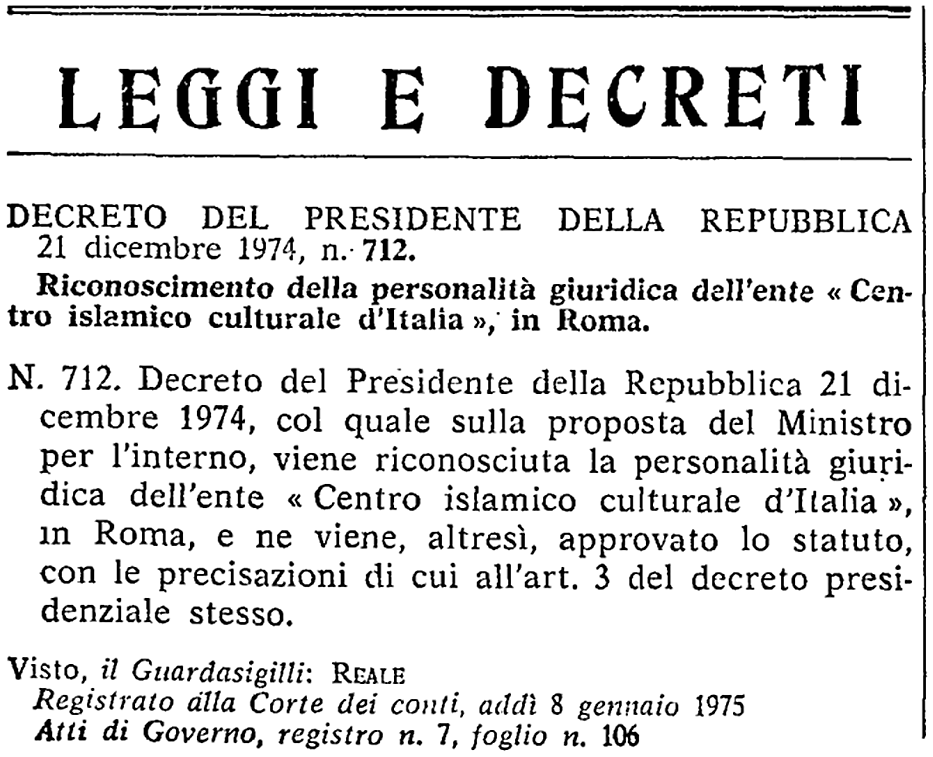

In Italy, the recognition of religions follows a structured process outlined in Article 8 of the Constitution. This article emphasizes the equality of all religious confessions before the law and their right to organize themselves according to their statutes, as long as they comply with the Italian legal system. However, the formal relations between religions and the state are regulated through agreements established with relevant representatives. These agreements, known as Intese, are subject to a meticulous negotiation process, initiated by the government upon request from the interested religious confessions. Before negotiations commence, confessions must have obtained legal recognition pursuant to law no. 1159 of 24 June 1929, with approval from the Council of State. Once negotiations are concluded, agreements are scrutinized by the Council of Ministers and then sent to Parliament for approval by law. Currently, Italy formally recognizes twelve religions through these agreements, covering a diverse spectrum of religious beliefs and practices (Crupi Reference Crupi2003).Footnote 3 However, religions that do not have Intese Footnote 4 with the state lack juridical status and are technically classified as cultural associations. This includes Islam, which, apart from the Centro Islamico Culturale d’Italia (the Great Mosque of Rome), does not have a specific agreement with the Italian state (Gazzetta Ufficiale 1975). Figure 1 shows Decree No. 712, issued by the President of the Republic on December 21, 1974, which officially recognizes the Islamic Cultural Center of Italy in Rome as a legal entity and approves its statute with specific provisions outlined in Article 3.Footnote 5 Consequently, Islam is generally categorized as a “religione di culto” (cult religion) under Italian law.

Figure 1. Decree No. 712 (December 21, 1974) recognizing the Islamic Cultural Center of Italy as a legal entity.

Similarly, the Coptic Orthodox Church, despite its significant presence in Italy, does not have a formal agreement with the state. This is because, like Islam, it lacks a single, centralized authority that can represent the entire religious community. In Italy, any formal agreement “Intese” between the state and a religious group must be negotiated with a recognized representative body. However, the nature of both the Coptic Orthodox Church and Islam makes this difficult. Unlike other churches, which have a hierarchical structure, neither the Coptic Church nor Islam has a unified leadership. In the case of Islam, this means there is no single organization that can represent all Muslims in Italy as a united group. As a result, establishing a formal agreement for either the Coptic Church or Islam presents significant challenges, as Italian law requires negotiations with an official representative that simply does not exist for these religions.

Due to this fact, every tentative regulation between the Italian State and Islamic representatives was complicated by trial and error, involving mostly the main Islamic associationsFootnote 6 (Giorda and Vanolo Reference Giorda and Vanolo2021). The attempts to recognize Islam in Italy have been marked by a series of initiatives and committees aimed at fostering dialogue and securing official recognition. Fabrizio Ciocca (Reference Ciocca2021) summarized these efforts, noting that the first significant step occurred in 2000 with the establishment of the Consiglio Islamico d’Italia (Islamic Council of Italy), aimed at creating a unified representation of Islam to engage in dialogue with the State. Subsequent efforts included the creation of a Consulta Islamica (Islamic Consultation) in 2005, tasked with fostering religious dialogue and seeking official recognition. However, progress stalled until 2010 when Interior Minister Roberto Maroni instituted the Comitato dell’Islam (Islam Committee) to discuss various issues concerning Islam in Italy, such as the wearing of veils and the registration of imams.

The Orientalism theory (Said Reference Said1978; 1995) provides an interpretation of how Egyptian migrants are framed as “others” in Italian society. Muslims are often depicted as cultural threats, while Copts are relegated to the category of “non-European Christians,” erasing the diversity within the Egyptian community and reinforcing their marginalization. These Orientalist stereotypes are evident in Italy’s recent attempts to integrate Islam through initiatives like the Consiglio per le relazioni con l’Islam (Council for Relations with Islam) and the Patto Nazionale per l’Islam Italiano (National Pact for an Italian Islam), signed in February 2017 under the Italian Ministry of the Interior (Dutta Reference Dutta2019). While these measures aimed to foster collaboration and integration by promoting religious transparency and aligning Islamic practices with Italian constitutional values, they simultaneously perpetuate the very stereotypes they seek to address.

For example, the pact’s emphasis on countering radicalization implicitly portrays Islam as a security threat, aligning with Orientalist narratives that depict Muslims as inherently oppositional to Western norms. Moreover, the pact’s requirement for imams to conduct religious services in Italian or provide translations, a condition not imposed on other religious groups, further marginalizes Muslims by framing their religious practices as incompatible with Italian civic values (Momigliano Reference Momigliano2017). These measures, though presented as efforts toward inclusion, reveal a deeper exclusionary logic that reduces Islam to a problem of “integration,” obscuring the cultural and religious diversity within the Muslim community. Said’s insights show how such policies reinforce Orientalist perceptions, treating Muslims as outsiders who must adapt to a predefined European identity rather than being recognized as contributors to a multicultural society.

The Egyptian Coptic Orthodox Church faces similar challenges in obtaining recognition as Islam does in Italy. Despite being a minority religious community, the Copts encounter hurdles in securing fixed places of worship, exacerbated by the reluctance of the local Catholic Church to sell its buildings to minority Christian denominations, including the Copts. This reluctance not only impedes the Copts’ path toward establishing a stable presence but also fosters sentiments of inequality and inferiority. The limited legal recognition and culturally inferior status compared to the Catholic Church present additional obstacles for the Coptic community to integrate fully into Italian society (Miličić Reference Miličić2022a). However, efforts to establish an organized ministry for the Coptic Orthodox community in Italy began in 1984, driven by the growing number of faithful, particularly in urban centers like Milan. The ministry saw significant developments with the arrival of leaders such as hieromonk Barnaba El Soryany and General Bishop Anba Kirolos, who played an important role in uniting believers and stabilizing the community. The consecration of hieromonk Barnaba as Anba Barnaba, Bishop of Turin, Rome, and the surroundings, and Anba Kirolos as Bishop of Milan, further solidified the presence of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Italy. Despite these advancements, the journey toward full recognition and integration remains challenging for the Coptic Orthodox community within the dense religious of Italy (Miličić Reference Miličić2022b).

This lack of recognition has significant consequences, such as mosques being ineligible for public funds, Islamic weddings lacking legal value, issues surrounding burial due to the lack of Islamic cemeteries, difficulties in building mosques, and Muslim workers not having the right to take days off for religious holidays (Wenmoth Reference Wenmoth2021). Both Islamic Imam and Bishop Gabriele of Milan, during interviews, expressed their frustration with the obstacles placed by the Italian state in recognizing Egyptian religions.

Bishop Gabriele of Milan, during an interview in July 2022, explained:

“The issue of the recognition of the Coptic Orthodox Church is that the Italian state requires only one person to make the agreement, and this is impossible because there are two archdioceses in Italy—one in Milan and the other in Rome and Turin.”

To attain official recognition in Italy, a concordat agreement must be signed with the state by only one representative of the religion. For Muslims, the situation is even more complicated. The Italian government treats Islam as a homogenous religion, requiring a single representative for Islam, despite the internal diversity within the Muslim community. The challenge of unifying Shia and Sunni Muslims, along with other subgroups, who do not agree on all matters, and accommodating the linguistic and legal diversity among Muslim migrants, makes this task even more difficult (Ferrari Reference Ferrari2010).

In a separate interview in May 2022, an Imam from a mosque in Milan lamented:

“They accuse us of not cooperating, but what they demand is impossible. Several attempts have been made to explain that what they ask is difficult to achieve since the Islamic religion does not follow one side and does not have a leader.”

To conclude, the frustration of Islamic leaders in Milan is evident, as they feel that the government’s demands for unity and cooperation are unrealistic given the diversity within Islam. The requirement of a ‘concordat’ agreement for recognition poses practical challenges, as mentioned by Bishop Gabriale. The presence of multiple archdioceses in Italy for the Coptic Orthodox Church creates bureaucratic difficulties in meeting the state’s criteria for recognition. The situation for Muslims is even more intricate, as the Italian government’s approach assumes homogeneity within Islam, which is far from accurate. The diversity of religious practices, beliefs, and linguistic backgrounds among Muslim migrants complicates the task of appointing a single representative. The frustration expressed by Islamic leaders in Milan reflects the need from the Italian authorities for a more nuanced understanding of religious diversity within the Muslim community. These challenges not only affect the religious freedom of the Egyptian minority but also have implications for their sense of belonging and inclusion in Italian society. It is essential to recognize and address these issues to promote religious pluralism and the integration of diverse religious communities into the social fabric of Italy.

Brief History of Egyptian migrants in Italy

Egyptian migration to Italy commenced nearly two centuries ago, in the early nineteenth century, when Mohamed Ali, the visionary behind modern Egypt and de facto ruler from 1805 to 1848, dispatched missions to Europe. The initial Egyptian mission to Italy in 1813 focused on studying the printing arts (Zohry Reference Zohry2009). This migration pattern persisted until the 1950s. However, in July 1965, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal. As a result, a joint Israeli British-French attacked Egypt in what is known as the “Suez Crisis” (Ross Reference Ross2004). At this moment, the direction of immigration changed towards Italy. In the early 1960s, groups of migrants began arriving in Italy, including a significant number of “Italo-Egyptians,” Jews, and Coptic Christians. These groups faced expulsion from Egypt’s regime (1956–1970) following the Suez crisis (1956). Over subsequent years, certain Egyptians fell out of favor with the Nasserist regime, leading to discrimination.

The 1960s saw a steady influx of Egyptian students migrating to Italy. In 1972, a bilateral agreement between Italy and Egypt introduced tourism entrance visas lasting 3 to 6 months, enhancing Italy’s allure for Egyptian worker immigrants. The fourth Arab-Israeli conflict prompted a surge in Egyptian immigrants after 1974, with many young men fleeing extended military service. Egypt’s initial wave of migrants to Italy displayed high education levels, a male majority, and urban origins, fostering a positive image of Italy and fostering cultural connections.

A notable spike in Egyptian presence in Italy occurred between 1989 and 1990, coinciding with the implementation of Martelli’s law. According to Ambrosini (Reference Ambrosini2012), this policy not only regularized submerged irregular migrants but also drew fresh immigrants. Over a year, residence permits doubled from 10,209 to 20,211. This set a stabilized trend, with periodic “physiological” increments attributed to family reunifications, measuring 4%. The Interior Minister estimated the irregular Egyptian migration rate to be approximately 22.9%. The persistent inflow of immigrants, particularly after the fall of the Iron Curtain and the imminent Schengen Treaty ratification (1993), remained steady for a decade (Paparusso, Fokkema and Ambrosetti Reference Paparusso, Fokkema and Ambrosetti2016).

The last two decades have witnessed a dramatic surge in immigration. The 1990s saw an increase in irregular African migration to Europe, characterized by youth, recent graduates, and unemployed individuals with limited education Zohry (Reference Parati2007); Sinatti (Reference Sinatti2006). The “second wave” of Egyptian migration emerged in the 2000s under the new recruitment system, often involving families. This group’s composition became more diverse, including lower education levels, varied socioeconomic backgrounds, and rural origins (Premazzi, Castagnone and Cingolani Reference Premazzi, Castagnon and Cingolani2012).

The Egyptian Community in Milan

The Egyptian community in Italy can be divided into two main groups: established migrants and contemporary migrants. Established migrants refer to those who arrived in Italy between 1960 and 2010. Many have settled, established businesses, obtained Italian citizenship or permanent residency, and brought their families with them. On the other hand, contemporary migrants ((Zohry Reference Zohry2006) arrived within the last 15–20 years, particularly following the Egyptian revolution of 2011. While this wave of migration is often attributed to political disruption, the primary cause was economic turmoil stemming from the revolution, which led many Egyptians to seek better opportunities abroad. In contrast to other Arab Spring countries, where political persecution was a major driver of migration, the Egyptian case is more economically driven (Zohry and Debnath Reference Zohry and Debnath2010; ElBahlawan Reference ElBahlawan2023). Additionally, weak border and sea controls, especially in Libya, facilitated the movement of refugees and asylum seekers through this cost-effective route, making it an appealing option for many Egyptians despite the risks. This new wave of migrants brought distinct characteristics and goals, leading to more permanent settlement patterns. Enhanced access to immigration networks, fueled by an increasing Egyptian presence in Italy, contributed to the expansion of these networks, fostering stronger connections and support systems within the Egyptian immigrant community (Zikry Reference Zikry2021).

Numerous studies have examined Egyptian immigrants in Italy since the 1990s, focusing on societal integration (Ambrosini and Caneva Reference Ambrosini and Caneva2012), community concentrations (Colombo and Sciortino Reference Colombo and Sciortino2004), intergenerational dynamics (Giorda and Vanolo Reference Giorda and Vanolo2019), transnationalism and identity (Scaglioni and ElBahlawan Reference Scaglioni and ElBahlawan2024). Other research has highlighted multiculturalism (Triandafyllidou Reference Triandafyllidou, Modood, Triandafyllidou and Zapata-Barrero2006), entrepreneurship and economic activities (Ambrosini Reference Ambrosini2012), home making and care practices (Scaglioni and ElBahlawan Reference Scaglioni and ElBahlawan2024), health challenges (Quaglia et al. Reference Quaglia, Terraneo and Tognetti2021), return migration (Sinatti Reference Sinatti2011), and the role of the second generation and age in shaping experiences of migration (Menin Reference Menin2011; Rhazzali and Schiavinato Reference Rhazzali and Schiavinato2023). However, little research has focused on how they evolved as a society, particularly after their numbers surged. Contrary to the notion that Egyptians in Milan exist as individuals or separate communities, more in-depth investigation in the field reveals that they constitute a minority representing recognized characteristics—ethnic, religious, linguistic, and cultural.

The Egyptians in Milan show a complex reality, one that isn’t readily evident at first glance and is marked by its diversity. The various ways in which this diversity manifests itself have captured the attention of researchers. For instance, Ambrosini and Abbatecola (Reference Ambrosini, Abbatecola and Sciortino2002) explored this complexity by characterizing Egyptians as “silent and a little invisible.” This description not only highlights the subtlety of their presence but also suggests that their engagement in the social fabric might not be immediately apparent to external observers. This ambiguity can stem from factors such as their unique settlement patterns, transnational ties, and cultural dynamics, all of which contribute to a sense of identity within the larger community.

Adding to this narrative, Ambrosini and Scheilenbaum (Reference Ambrosini and Schellenbaum1994) coined the term “submerged community” to describe the Egyptian migrant presence in Milan. This characterization sheds light on the layered nature of their existence. Unlike more visible communities, the Egyptian community operates within a wide-mesh network that isn’t easily distinguishable from the outside. This complication can be attributed to their historical trajectory, the multiplicity of their cultural affiliations, and the adaptable nature of their social connections. This characterization goes beyond the traditional understanding of a community, demonstrating that the Egyptian presence in Milan defies easy categorization while maintaining a cohesive identity.

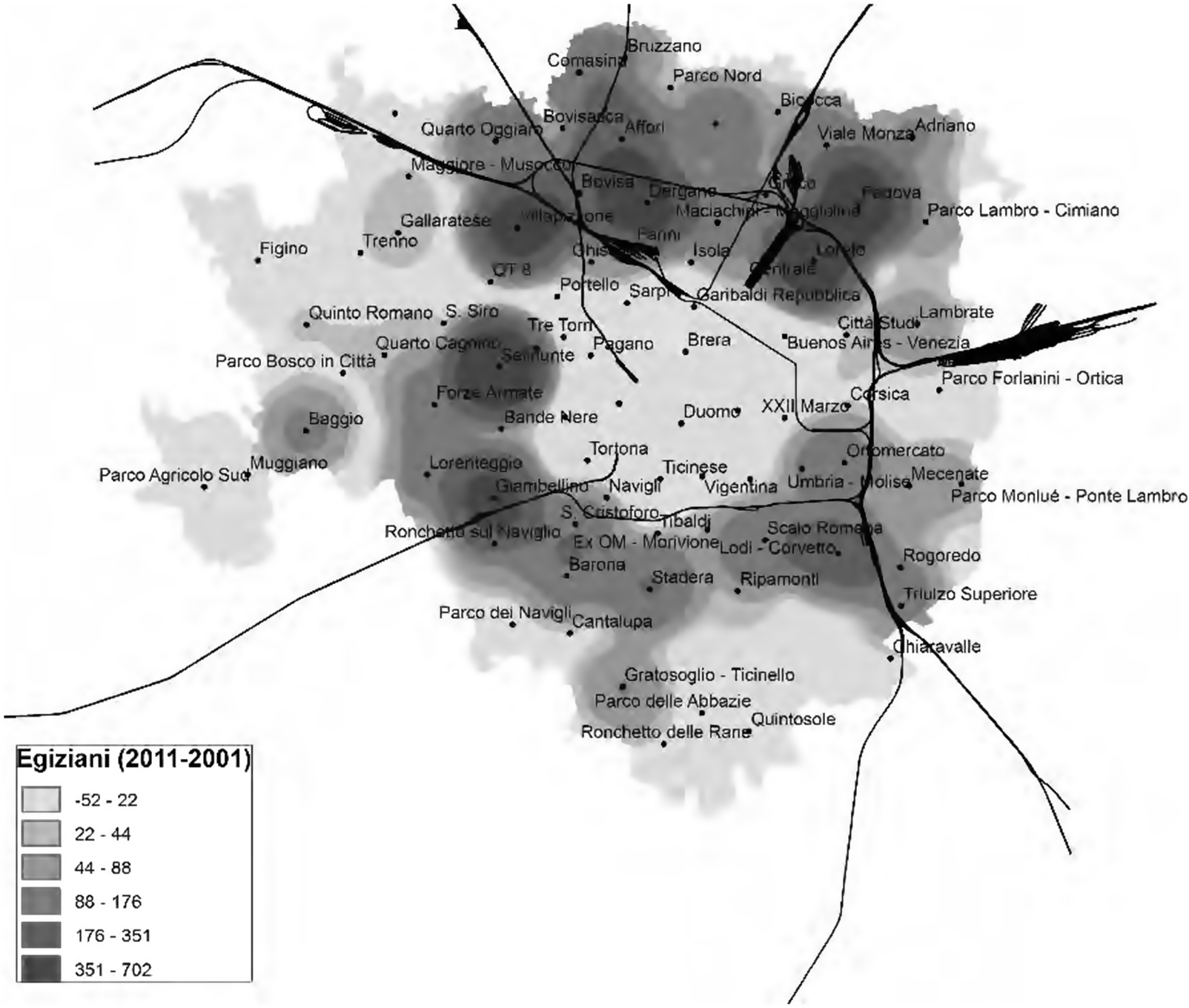

Furthermore, Tosi’s (Reference Tosi and Farina1997) insights into the settlement patterns of Egyptians in Milan contribute to our understanding of their dispersion across the city. Instead of clustering in specific neighborhoods, the Egyptian population has achieved a diffusive settlement, with their presence spanning various areas of Milan. This spatial distribution is highlighted in Fig. 2 map showing their integration into the urban landscape and underscores their contact with the broader society. This widespread dispersion challenges preconceived notions of insularity and emphasizes their presence as a dynamic and integrated part of the urban fabric.

Figure 2. Variation of residential distribution of Egyptians in Milan (2001–2011).

Source: Susanna Molteni (University of Milan-Bicocca) from Census data, (Mugnano and Costarelli, Reference Mugnano and Costarelli2018).

Moreover, the investigation conducted by Colombo and Sciortino (Reference Colombo and Sciortino2004) into territorial concentration among migrants in Milan offers additional layers of insight. It emphasizes the unique presence and concentration of Egyptians in Milan, despite the already-established Egyptian community in Reggio Emilia. This finding points to the magnetic pull that Milan exerts on Egyptians seeking opportunities, fostering a level of concentration that surpasses locations with longer-established communities. The concentration, despite the presence of an established community nearby, stresses the diverse motivations, aspirations, and dynamics of Egyptians’ existence in Milan.

Earlier attempts at characterizing the Egyptian migrants have led to descriptions of “networks of isolated groups,” a label that highlights the intricate and sometimes discreet nature of their presence. This portrayal, while not entirely inaccurate, may fall short of capturing the complexity of their interactions and shared identity. Such descriptions reflect the challenge of categorizing the Egyptian migrants as a unified community, especially given the shifting and evolving nature of their social fabric. The term “community” itself often conveys a sense of homogeneity and enclosure; a notion rooted in traditional philosophical discourse about national identity (Scaglioni and ElBahlawan Reference Scaglioni and ElBahlawan2024). In the context of the Egyptian migrants, however, this concept appears to transform, embodying a more fluid and dynamic construct.

To sum up, the trajectory of Egyptians in Milan began with individuals, coalesced into small groups, and evolved into interconnected societies—a transformation that echoes the historical dichotomy between Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society) (Tönnies Reference Tönnies1887). Over time, these Egyptian societies attracted fellow Egyptians from similar cultural and religious backgrounds, forming a dynamic community with a progressively integrated Egyptian identity. This identity blended into Italian society while retaining essential Egyptian characteristics—language, religion, customs, and traditions. Vital institutions, such as places of worship, cultural organizations, and charitable groups, cemented their interaction. This gradual evolution eventually laid the foundation for the Egyptian minority’s initial structure within Italy. The Egyptian minority in Italy can be recognized as an ethnic group or as a minority containing many ethnic groups.Footnote 7

The Everyday Realities of Egyptian Migrants in Milan

Everyday life provides a valuable lens through which to view the multifaceted experiences of migration, moving beyond broad notions of globalization and transnationalism to focus on the ordinary realities of life across various spaces and places (De Certeau and Mayol Reference De Certeau and Mayol1998; Boccagni Reference Boccagni2017). The ‘everyday’ includes a range of activities, from seemingly mundane daily tasks to localized practices influenced by specific contexts (Ho and Hatfield Reference Ho and Hatfield (née Dobson)2010: 710). Schielke (Reference Schielke2022) argues that religion, particularly Islam, is often experienced through everyday challenges rather than grand, idealized doctrines. This perspective is essential for understanding how Egyptian migrants in Milan adapt their religious practices as a minority to a secular environment where their faith lacks formal recognition and public religious expression is restricted. His insights help us see how migrants engage with their religion pragmatically, balancing faith with the immediate concerns of employment, housing, and legal insecurity.

For Egyptian migrants in Milan, everyday life is a dynamic relationship of challenges and opportunities. Drawing on the accounts of Egyptian migrants, this study reveals the condition of being migrants becomes an indelible aspect of their lives, permeating their political and economic worlds, as well as their social and community networks. Their everyday existence revolves around fulfilling basic needs, such as securing housing, finding employment, sustaining their livelihoods, maintaining familial ties, observing religious practices, and nurturing future aspirations. However, living in the midpoint between legality and illegality, coupled with unpredictable changes in their legal status upon settlement, characterizes their lives (Jauhiainen and Tedeschi Reference Jauhiainen and Tedeschi2021). The unpredictability stems from the ongoing challenges and sudden shifts associated with their uncertain legal status in a secular land (Hörschelmann Reference Hörschelmann2011). John Bowen (Reference Bowen2007) highlights how Muslims in European secular societies must adapt their religious practices to fit within the constraints of local laws while striving to maintain their religious identity. Similarly, Egyptian migrants in Milan must navigate restrictive legal and cultural frameworks, balancing their faith with practical survival needs in a society that does not officially recognize their religion. This adaptation process, often informal and flexible, exemplifies how Egyptians reinterpret and adapt their faith to fit into a secular framework.

Multiculturalism also plays out in the everyday lives of individuals. Menin (Reference Menin2011) highlights how young Muslim women in Milan navigate the challenges of wearing the hijab, a visible marker of their religious identity, within a modern, often secular society. For many, the hijab represents not only a personal religious choice but also a connection to their cultural community, where shared experiences of faith and migration provide a sense of belonging. These women must constantly negotiate between their religious expression and societal expectations, reflecting how multiculturalism and identity are contested in everyday life.

For Egyptians, ethnicity is deeply rooted in shared cultural heritage and religious traditions, connecting Muslims and Copts through a collective identity. However, the Italian state often categorizes them through a reductive lens, framing Muslims as security threats and Copts as ‘non-European Christians. In their daily lives, Egyptian migrants in Milan, especially those without legal status, employ creative tactics and survival strategies to meet their basic needs (De Certeau Reference Certeau and Rendall1984) and overcome daily challenges. The shared observance of religious holidays and communal gatherings plays a critical role in maintaining ethnic cohesion within the Egyptian diaspora. These practices reinforce a sense of belonging among migrants, bridging the divide between Muslims and Copts through a collective Egyptian identity. However, systemic exclusion from institutional spaces, such as the inability to establish official mosques or Coptic cultural centers, disrupts these practices and weakens the community’s cohesion.

Through constant adaptation and resilience, they transform obstacles into opportunities for personal and communal growth. While some actively seek social connections and support networks to cope with mental stress, others find solace in isolation. Cafés and communal spaces offer temporary refuge from psychological pressures, while mosques serve as sanctuaries for prayer and spiritual connection, providing comfort amidst the challenges they face. On the other hand, kinship networks and community support play a crucial role in providing a safety net for newcomers facing precariousness, uncertainty, and societal rejection in their daily lives. These restrictions conflict with the principles outlined in international human rights frameworks, such as Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB), which safeguard individuals’ rights to freely practice their religion. Asad’s framework (Reference Asad2003) emphasizes how Egyptian identity is shaped by external recognition, which can limit their ability to assert their identity publicly, reinforcing their perception of being marginalized outsiders.

In a diverse city as Milan, mosques and Coptic Orthodox churches are part of everyday life for Egyptian migrants; their religious practices intersect with the difficulties of gaining recognition for their faith. By investigating how religious expression and acknowledgment unfold within the city, we seek to uncover the difficulties migrants face as they navigate the recognition of their religion in a secular environment. Ultimately, our goal is to illuminate the intricate nature of religious identity and its impact on the sense of belonging, community cohesion, and resilience among the Egyptian minority. Recognizing the intersectionality of religion and ethnicity is essential for addressing systemic barriers. Policies must go beyond treating religion as a private matter to acknowledge its cultural and social significance in shaping migrant identities. Figure 3 shows Muslim celebrations and Eid prayer in Monza Stadium.

Figure 3. Eid prayer in Monza Stadium organised by the Centro Culturale Islamico di Monza della Brianza.

Source: Centro Culturale Islamico di Monza della Brianza 2023.

Everyday practice and Places of Worship

Constructing new mosques and churches is a complex issue for the Egyptian minority in Italy. As declared in the Italian constitution, citizens can practice their religion publicly or privately (Article 19), and the Italian Constitutional Court has upheld the right to exercise one’s religion in a specifically designated building. However, due to the absence of national laws governing the construction of places of worship, Italian towns and municipalities have the authority to determine which religious structures will be built, often guided by their urban planning regulations. This decentralized decision-making process has led to challenges and barriers to the construction of mosques and churches.

In some cases, local administrations bury planning permission requests for mosques and churches in bureaucracy, causing significant delays and frustrations for religious communities. Additionally, regulations with vague wording have been passed, creating uncertainty for those seeking to build places of worship. For instance, in Lombardy, a region with a substantial migrant population, the local authority passed a regulation in 2015 outlining the conditions for building a place of worship. These conditions included the requirement of a widespread, organized, and stable religious presence in a specific municipality and “respect for the local setting”. Unfortunately, the lack of clear definitions and quantification of these conditions has provided local administrations with discretion to justify blocking the construction of mosques, further complicating the process (Wenmoth Reference Wenmoth2021). These challenges ring in the everyday lives of Egyptian migrants, as they grapple with limited access to places of worship, extended waiting periods, and uncertainty regarding their religious practices. The difficulties in constructing religious institutions underline broader issues related to urban planning regulations, administrative discretion, and the necessity for comprehensive national guidelines.

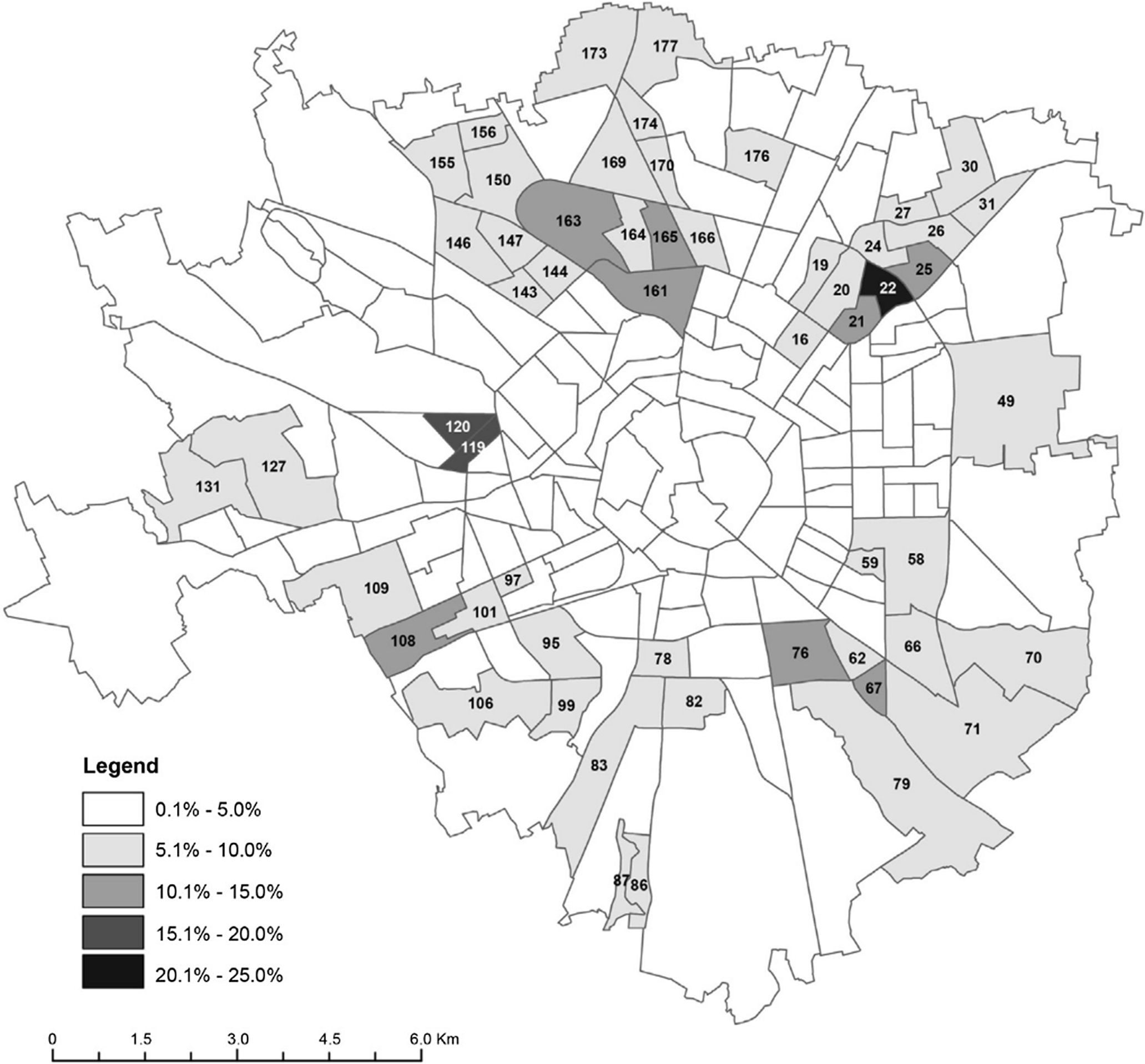

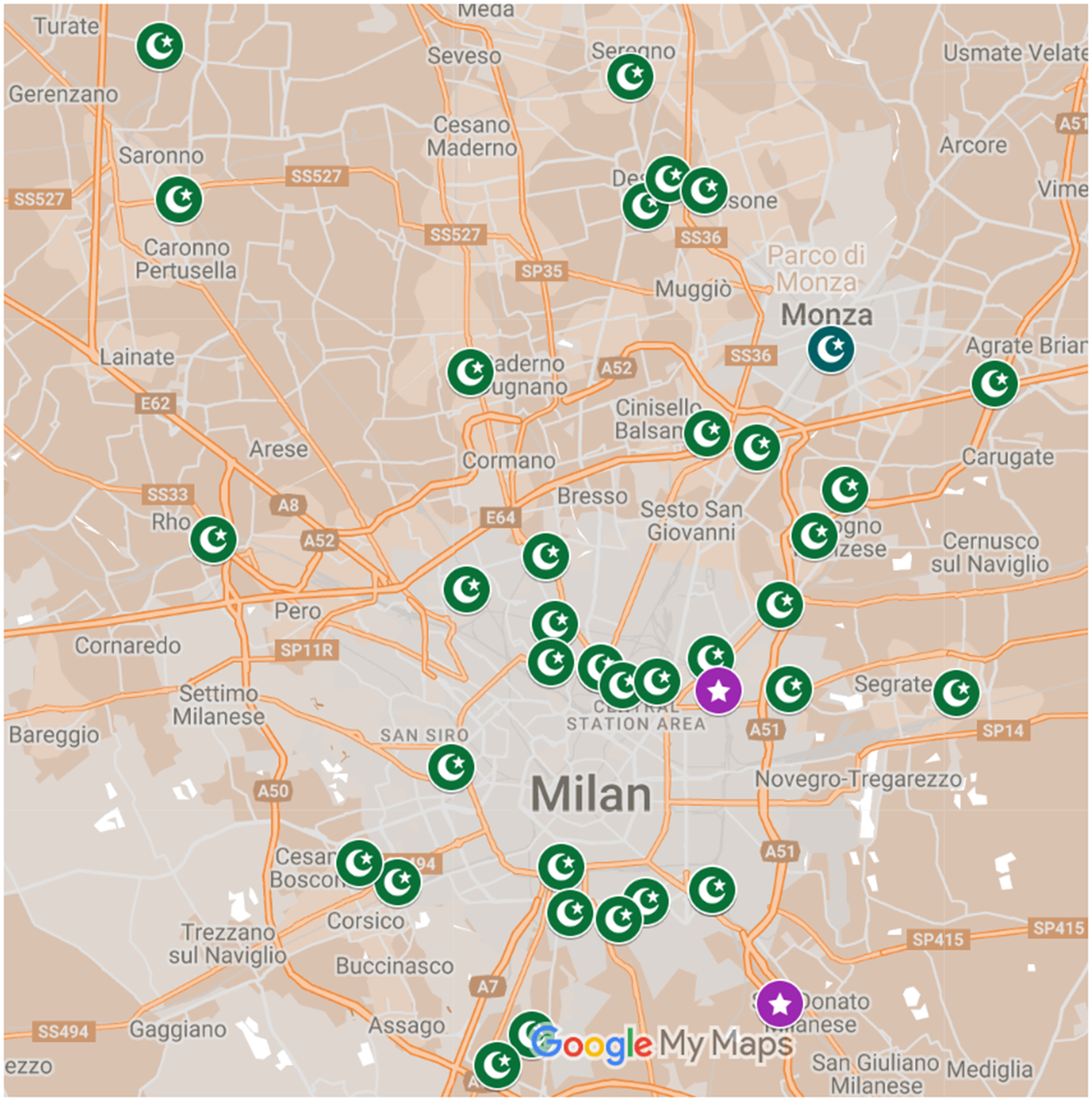

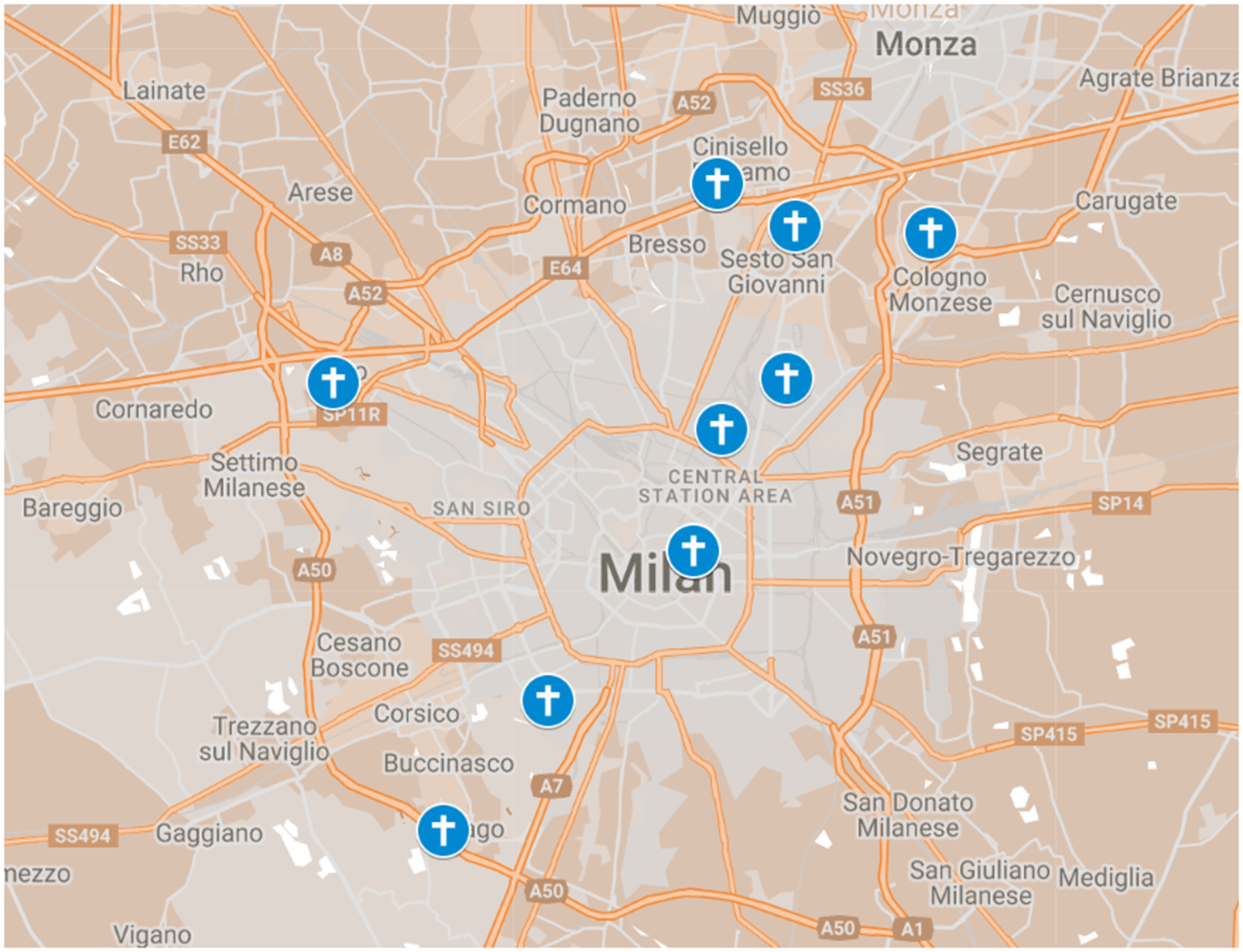

Concerning this phenomenon, Egyptian Muslims in Italy have attempted to navigate the challenges of establishing formal places of worship by repurposing old buildings such as warehouses and garages to create Islamic cultural associations with attached prayer areas. These centers often offer various cultural activities, including Quranic studies and Arabic/Italian languages classes, in addition to serving as places of worship.Footnote 8 Despite the significant presence of Muslims in Italy, Fig. 4 presents the distribution of Muslims in Milan percentages of the total population. The country lacks formal mosques (Giorda and Vanolo Reference Giorda and Vanolo2019), with several Muslim cultural associations operating in various makeshift structures, commonly referred to as musalla (prayer hall). Figure 5 shows the location of Muslim mosques in Milan province and its surroundings.

Figure 4. Distribution of (statistically) Muslims in Milan, 2013, percentages of the total population.

Source: Chiodelli (Reference Chiodelli2015).

Figure 5. Location of Muslim mosques in Milan province.

Source: owned author’s data, 2023.

According to estimates from the Interior Ministry in 2019,Footnote 9 there are approximately 1382 Islamic places of worship across Italy, but only two of them possess the distinctive architectural features of mosques, such as minarets and domes. Figures 6 and 7 show the two mosques of Milan and the great mosque of Rome.

Figure 6. Al-Rahman Mosque of Milan, Segrate City, opened 1988.

Source: Centro Islamico di Milano e Lombardia official website, https://www.centroislamico.it/.

Figure 7. The Grand Mosque of Rom, opened in 1994.

Source: Centro Islamico Culturale d’Italia official Facebook page.

These places not only cater to religious needs but also serve as hubs for social gatherings and community events, offering services ranging from Quranic studies in Italian to assistance with practical and bureaucratic matters, particularly for foreign Muslims. However, these makeshift places of worship often face opposition from neighboring residents, who perceive them as symbols of cultural invasion, further fueling populist narratives about the “Islamic invasion”. Despite the growing demand for official recognition and permission to construct new mosques in various Italian cities, only three mosques are officially recognized in the country: one each in Milan, Rome, and Catania. Requests for recognition or construction of new mosques have encountered resistance from Italian citizens and certain political factions, such as the Northern League in Padua and Milan (Ciocca Reference Ciocca2021). Figures 8 and 9 present places of worship, Islamic mosques and Coptic Orthodox churches located in Milan, which are essential reference points for the maintenance of cultural roots and for communications, and networks.

Figure 8. Places of worship Islamic mosques and coptic orthodox churches are essential reference points for the maintenance of cultural roots and for communications, networks.

Source: Author’s photograph, 2023.

Figure 9. The Coptic Orthodox Church of St. Simeon and Anna the Prophetess serves the Egyptian Christian community in Milan.

Source: Diocesi Cristiana Copta Ortodossa di Milano e dintorni official facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/ChiesaCoptaMilano/?locale=it_IT&_rdr.

Continuing the discussion on the challenges faced by Egyptian communities in Italy, for both Muslims and Coptic Orthodox Christians, a significant issue arises from the almost complete absence of prayer rooms in public places such as universities, airports, railway stations, and hospitals. Unlike some countries where prayer rooms are a common feature in public facilities, Italy lacks regulations mandating their provision. Consequently, individuals belonging to these religious communities may waste significant time traveling across the city to reach a mosque, or a church, often encounter difficulties in finding suitable spaces for prayer and religious observance while in public areas, leading to feelings of marginalization and exclusion.

Furthermore, the absence of regulations for religious assistance in hospitals and prisons exacerbates these challenges. In Italy, the provision of religious support in such institutions is contingent upon the discretion of local authorities, leaving the accessibility of religious services uncertain and inconsistent. Imams and clergy from other religious denominations, including Coptic Orthodox priests, face barriers in accessing hospitals and prisons, in some cases refugee camps, to provide spiritual guidance and support to individuals in need. This lack of standardized protocols for religious assistance not only hinders the religious freedoms of Muslim and Coptic Orthodox communities but also poses significant challenges to individuals seeking spiritual comfort and guidance in times of distress or incarceration.

When it comes to the Coptic Orthodox Church in Italy, the challenges of acquiring suitable places of worship mirror those experienced by the Muslim communities, the Coptic community seeks to maintain its religious practices and spirituality. However, the process of acquiring church buildings presents significant hurdles. Initially, the community relied on rented private rooms and Catholic chapels for worship such as Saints Simeon and Anna Coptic church in Milan which used to be a factory. Financial constraints and bureaucratic complexities often prevent the purchase or construction of dedicated Coptic churches. Instead, the community primarily utilizes abandoned venues, such as factories and garages, which are transformed into places of worship (Miličić Reference Miličić2022b). This practice is particularly prominent in the Diocese of Milan, where abandoned spaces are repurposed to meet the urgent need for church buildings. However, the inability to purchase unused Catholic church buildings due to legal and cultural factors poses a significant challenge. Figure 10 shows the locations of the Coptic Orthodox Churches in Milan province.

Figure 10. Locations of the coptic orthodox churches in Milan province.

Source: owned author’s data, 2023.

The absence of institutional recognition for Egyptian religious practices has far-reaching implications beyond spiritual marginalization. These systemic barriers align with Asad’s (Reference Asad2003) argument that identity is shaped through external recognition. The Italian state’s refusal to grant institutional acknowledgment to Egyptian religious practices reinforces their invisibility, marginalizing their role in the public sphere (Ferrari Reference Ferrari2020). This lack of recognition reflects the broader coloniality of power described by Maldonado-Torres (Reference Maldonado-Torres2007), where non-European identities are systematically excluded from structures of authority and visibility.

Cemeteries: Complexities of Burial Practices

The issue of Islamic cemeteries and the practice of Islamic burial in Milan adds another layer of complexity to the everyday lives of Egyptian migrants. The United States Department of State (2022) reported that Muslim groups in Italy, lacking formal agreements, faced challenges in obtaining permission from local governments to construct mosques and establish dedicated areas for Islamic burials. While some local authorities granted permissions for mosque construction and burial plots, it was insufficient to meet the increasing demand, as highlighted by the Union of Islamic Cultural Communities (UCOI). Additionally, a 2019 Lombardy regional law prohibits the division of burial plots by religious belief, affecting both Muslim and Coptic Orthodox communities. Despite some exceptions made by local authorities, there remained an inadequate number of burial spaces for Muslim communities in Lombardy, Lazio, and other regions, according to reports from Muslim associations. The UCOI noted that while 76 local governments maintained dedicated burial spaces for Muslims, compared to 60 in 2021, the demand still outpaced the availability of burial plots.

Burial in the Islamic tradition is an integral aspect of the religion, guided by specific rules and customs. Dr Ali Abu Shwaima, the president of the Islamic center in Milan and Lombardy, sheds light on the intricate journey of securing proper burial grounds for the Muslim community. The quest for Islamic cemeteries in Italy began with the Al-Rahman Mosque, which successfully obtained land for Muslim burials in Lambrate in 1976. Initially, the municipality of Milan allocated thirty-two burial plots, with the understanding that the graves would remain indefinitely unaffected by changes in shape or relocation. Remarkably, these graves remain untouched even after 35 years. When the Lambrate cemetery reached its capacity, the Islamic Center sought additional burial space in Bruzzano, securing 50 graves in 1995. The terms of this agreement mirrored the previous one, allowing the graves to remain without a specified timeframe. However, the need for more burial space persisted, leading to negotiations with the Milan municipality.

Eventually, a new cemetery within the Bruzzano location was obtained, accommodating up to seven hundred graves. The agreement involved several conditions, such as restricting burial permits to only Milan residents and dedicating a separate section for children. The crisis escalated significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the number of Muslim victims exceeded the cemetery’s capacity to accommodate them promptly. This challenge prompted calls for increased “political will” to address the need for additional burial spaces. Under Italian law, cemeteries have the option to allocate “special and separate sections” for non-Catholics. While 150 municipalities responded positively to requests for Muslim burial sections, the growing need for these spaces reflects a shift in burial preferences among immigrant communities. Many individuals who had planned to be buried in their countries of origin are now choosing Italy due to the presence of their children and grandchildren in the country. This evolving trend underscores the intricate interplay of religious and cultural practices within Milan.

The logistical and financial issues of Muslim burials add other obstacles involving repatriating deceased Egyptians to their home country. The process of repatriating deceased individuals to Egypt for burial involves various logistical and bureaucratic procedures. Invariably, when an individual dies, the body is sent to the home country to be buried (Rhazzali Reference Rhazzali2023). This often entails obtaining death certificates, coordinating with local authorities and funeral homes, and adhering to transportation regulations, adding to the emotional and financial burden on the deceased’s family. Additionally, cultural and religious considerations play a significant role in the repatriation process, as families seek to honor their loved ones’ religious traditions and customs. After the dramatically rising demands of repatriating deceased bodies from the Egyptian authorities (Ahram Online 2021), in response to this concern, the Egyptian government has implemented a mandatory traveler insurance policy for its citizens traveling abroad, which includes coverage for the repatriation of bodies in the event of death. This insurance policy, issued with each new or renewed Egyptian passport, provides financial support for the transportation of deceased nationals back to Egypt from a total of 30 countries, including Italy (United Nations Network on Migration – GCM, 2022). This initiative, part of The Global Compact on Migration, aims to facilitate the repatriation process for Egyptian expatriates and their families. For the Egyptian Muslim community in Italy, ensuring a proper Islamic burial following their faith is paramount, emphasizing the importance of access to inclusive repatriation services and support mechanisms.

Another issue added to the complex situation surrounding Muslim burials in Italy is the clash between burial customs and Italian law. Muslims traditionally bury their deceased without a casket, but Italian law requires burial in wooden coffins. This discrepancy has forced Muslims to adapt their burial practices. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, travel restrictions made it impossible for many Muslims in Italy to bury their deceased loved ones, compelling them to keep the corpses at home until municipalities could accommodate burials in public cemeteries (Čizmić Reference Čizmić2020; De Michele Reference De Certeau and Mayol2020).

Financial Struggles and Taxation Barriers

The financial support and taxation policies in Italy are significantly present in the ordinary processing of both recognized and unrecognized religious communities. Unlike recognized associations and canters, which benefit from tax exemptions and access to financial support, unofficial Islamic centers and Coptic churches cannot avail themselves of these privileges. This absence of recognition also deprives them of essential financial support. For instance, they are unable to benefit from tax exemptions reserved for recognized religious organizations, disturbing their financial sustainability and operational capabilities. Financial constraints highlight the structural inequalities faced by Egyptians, where unrecognized religious groups are excluded from public funding. Said’s critique of Orientalism (Reference Said1978; Reference Said1995) illuminates how such exclusions perpetuate stereotypes of non-European groups as economically dependent or culturally incompatible, reinforcing systemic marginalization. Similarly, Maldonado-Torres’ (Reference Maldonado-Torres2007) notion of coloniality explains how these financial barriers reflect a broader hierarchy that privileges European religious identities over others.

Additionally, the inability of unrecognized religious communities to participate in tax refund policies further exacerbates their financial strain. For example, Muslim associations cannot participate in the “8x1000” tax refund scheme due to the absence of a formal agreement between the Italian State and Islamic communities. This policy, which redistributes tax refunds to religious denominations based on taxpayers’ choices, excludes unrecognized religious groups from accessing crucial financial resources. On the other hand, the Italian state has historically supported the Catholic Church financially, primarily through direct transfers of public funds. However, with the introduction of the “8x1000” system in 1990, the financial system changed, allowing taxpayers to allocate a portion of their taxes to religious institutions of their choice. While this system initially benefited the Catholic Church, other recognized religious groups now have access to these funds.

Moreover, the financial processes within the Muslim community differ, with funding primarily sourced from the zakat,Footnote 10 a form of alms giving mandated by Islamic law. However, without access to government funds or tax refund schemes, Islamic associations rely heavily on community contributions and donations from foreign Muslims and migrants. This limited financial support significantly affects their ability to establish and maintain religious centers, exacerbating the challenges faced by the Muslim minority in Italy (Zannotti Reference Zannotti2014).

Like Egyptian Muslims, many Coptic Christians who have settled in and around Milan have secured stable employment and can financially support their diocese. However, financial limitations have become apparent, preventing their ability to establish permanent places of worship. Early Coptic communities in Italy faced challenges in affording to buy or construct church buildings. The clergy members sent to Italy, along with their followers, had to navigate legal regulations and social dynamics related to securing places of worship. This situation exacerbates the difficulties in securing fixed places of worship for Copts, leading to feelings of inequality and inferiority. Despite being a minority in Italy, the limited legal recognition and inferior status of Copts present significant obstacles in operating their dioceses and maintaining their religious institutions (Miličić Reference Miličić2022b).

Educational Challenges and Cultural Preservation