Introduction

For most of American history, Black Americans have not had the right to vote. In the American South, Black officeholding has been an extremely rare occurrence in the roughly 250 years since the nation’s founding. In the study of Black participation and representation, researchers have found a connection between legal enforcement of voting rights for Black Americans and the election of Black representatives (Bernini, Facchini, and Testa Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023; Chacón, Jenson, and Yntiso Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021; Davidson and Grofman Reference Davidson and Grofman1994; Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013). We argue that without legal enforcement of enfranchisement, multiracial democracy would not exist in the U.S. South. We test our argument by examining Black officeholding during two key periods: Reconstruction and after the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). These two periods of Black officeholding were preceded by long stretches of virtually zero Black officeholding in the South. We find that in both cases, the transition from minimal Black officeholding to more representative governance depended on active legal enforcement of voting rights by the federal government.

We argue that legal enforcement of multiracial democracy enables Black Americans to participate meaningfully in politics and ultimately choose their preferred representatives, who are often Black Americans. This argument implies that without active legal enforcement in the Southern United States, Black Americans cannot meaningfully participate in electoral politics. We test our argument in two settings: first, during the Reconstruction Era, and second, after the passage of the 1965 VRA in the South. We focus on the South because while Black Americans were largely disenfranchised throughout American history, Black officeholders first emerged primarily from Southern states during Reconstruction and after the VRA’s passage. This focus on the South is particularly appropriate given its distinctive history of racial discrimination and disenfranchisement, which scholars have emphasized as central to understanding the region’s development and role in American political development (Bateman Reference Bateman2023; Chin and Wagner Reference Chin and Wagner2008; Gray and Jenkins Reference Gray and Jenkins2025).

During the Reconstruction era, we operationalize federal enforcement using the location of federal troops that ensures the participation of Black men in elections. These data are obtained from 1866 to 1880 using the Mapping Occupation Project (Downs Reference Downs2015; Downs and Nesbit Reference Downs and Nesbit2015). We use data on Black officeholders in the South during and after Reconstruction reforms from 1866 to 1912 originally collected by Eric Foner in Freedom’s Lawmakers (Foner Reference Foner1993). In the post-VRA analysis, we use information about where the VRA mandated federal oversight over elections starting in 1965 collected by the Department of Justice. To capture Black officeholding after the passage of the VRA, we digitize the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies’ Roster of Black Elected Officials in the South from 1969 to 1993. This roster includes federal, state, and local Black elected officials. By digitizing these records, we create a unique and novel dataset about Black elected officials over time, throughout the South, and across electoral contexts.

We run two-way fixed effects analyses to test our argument. In these analyses, we compare the election of Black elected officials in locations where federal troops ensured the participation of Black American men to locations where they did not for every year included in our analysis during Reconstruction. We find that Black representation stems from counties in which two conditions are met: the federal government ensured the enfranchisement of Black Americans by deploying federal troops, and a large Black population. In the VRA analysis, we compare locations that required preclearance over federal elections, ensuring greater Black participation, to locations that did not for every year included in our analysis. We find that Black representation occurred in greater numbers in places where there was both federal oversight and a large Black population. By showing that federal enforcement of the law leads to the election of Black representatives in two time periods, we provide extensive support for our framework. Our findings suggest that federal policy aimed at the legal enforcement of democracy is a necessary condition for Black descriptive representation in the South.

The findings from this paper support existing scholarship that explores the connection between suffrage and political representation (Bernini, Facchini, and Testa Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023; Chacón, Jensen, and Ynitso Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021; Combs, Hibbing, and Welch Reference Combs Michael, Hibbing and Welch1984; Davidson Reference Davidson1992; Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013; Whitby and Gilliam Reference Whitby and Franklin1991). We offer a more comprehensive understanding of how the federal enforcement of suffrage extension influences Black representation by including more elections, analyzing two time periods, and including a greater universe of cases of Black representatives.

The significance of this relationship extends beyond merely documenting a historical correlation. Black political representation fundamentally shapes both democratic processes and policy outcomes. Research consistently demonstrates that Black officials advance different legislative priorities, are more responsive to Black constituents’ concerns, and enhance democratic legitimacy among historically marginalized communities (Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Haynie Reference Haynie2001; Preuhs Reference Preuhs2006). When Black voters can elect their preferred candidates—often, though not exclusively, other Black Americans—this representation yields substantive policy differences in areas from public spending to criminal justice reform. Black disfranchisement, on the other hand, has also been shown to change the behavior of elected officials (Olson Reference Olson2024). Our findings thus illuminate not just who participates in democracy but how the very nature and outputs of that democracy are transformed when previously excluded groups gain meaningful access to political power.

We believe this subject warrants renewed attention as the federal government’s ability to ensure a multiracial democracy has come under threat after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). Scholars have questioned how this ruling affects racial minorities’ ability to participate in politics (Komisarchik and White Reference Komisarchik and White2024), with some finding that it led to the reemergence of a racial turnout gap (Morris and Miller Reference Morris and Miller2024). The John Lewis Voting Rights Act was proposed in 2021 to reinstate the provisions that Shelby erased, though it ultimately failed to pass into law. With these recent events in mind, we believe our results present a cause for alarm about the future of racial minority representation should the United States continue curtailing voting rights protections. Our findings demonstrate that federal enforcement mechanisms have historically been essential for ensuring multiracial democracy and are thus highly relevant for contemporary debates about democratic governance in America.

Black (Dis)Enfranchisement from Reconstruction to the Voting Rights Act

The history of Black Americans’ participation in American politics coincides with the push and pull of democratic (dis)enfranchisement for Black Americans. Black American men were initially enfranchised during the Reconstruction era in the mid-nineteenth century. To be allowed back into the Union, Southern states that seceded during the Civil War had to adopt the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution. These amendments abolished slavery (13th), granted equal rights to formerly enslaved peoples (14th), and granted the right to vote for people of all races (15th). States that seceded from the Union also had to comply with the Military Reconstruction Acts. These reforms protected the ability of formerly disenfranchised Black Americans to exercise their vote by requiring each state to create new state constitutions that extended universal manhood suffrage and provided a mandate for the Army to register eligible Black males to vote. Furthermore, federal troops were deployed to former Confederate states in the South to ensure the participation of Black men. These Reconstruction changes provided the pathway for a multiracial democracy in the United States. Many term this as an “experiment in democracy,” rather than the beginning of democracy in the South, because the changes’ abrupt removal transitioned the United States to an era of democratic decay (Foner Reference Foner1988; Valelly Reference Valelly2009).

By the end of the nineteenth century, many states of the former Confederacy established voting procedures to circumvent the 15th Amendment (Kousser Reference Kousser1974; Reference Kousser1992; Perman Reference Perman2003). This led to the decrease of Black involvement in politics throughout the South, with the most precipitous drops in turnout and competitive elections taking place after Reconstruction in counties with the largest Black populations (Greenberger Reference Greenberger2022). For example, the implementation of the understanding clause in Louisiana led to decreased Black registration and turnout (Keele, Cubbison, and White Reference Keele, Cubbison and White2021). The introduction of poll taxes, literacy tests, felon bars, and the white primary in many states throughout the South effectively made it impossible for Black Americans to participate in elections (Key Reference Key1949). Many states changed formerly elected offices to appointed political positions so that Black Americans could not exercise their political power (Komisarchik Reference Komisarchik2024). This failure of Reconstruction led to near-authoritarian rule in the South and lasted for nearly 75 years until the passage of the VRA (Mickey Reference Mickey2015).

Civil Rights advancements curtailed disenfranchisement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Landmark Supreme Court decisions like Smith v. Allwright (1944) outlawed the white primary. The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in public spaces, provided integration of public facilities, and outlawed employment discrimination. It was not until the 1965 VRA, though, that Black Americans were fully politically enfranchised in the United States. Section 2 prohibited discriminatory voting practices. Additional amendments to Section 2 allowed for the creation of majority-minority congressional districts, which vastly increased Black representation. Section 4 identified places with an extreme history of racist voter exclusion that made it harder for Black Americans to vote. Section 5 laid out the preclearance process by which these jurisdictions had to submit any proposed changes to their voting laws for approval by the federal government. This increased registration rates among Black voters dramatically (Davidson Reference Davidson1992; Davidson and Grofman Reference Davidson and Grofman1994). Many argue that the era after the passage of the VRA, particularly due to the maintenance of the implemented provisions, is the first sustained period that the United States has been a multiracial democracy, allowing for all people to participate in the democratic process.

The Effect of Reconstruction and the VRA on Participation and Representation

Given that Black Americans were historically excluded from participation in politics, it is generally thought that the goals of Reconstruction and the VRA were to allow for greater Black participation in politics and eventually representation in government. Scholars have spent considerable time understanding whether both Reconstruction and the VRA achieved these goals. This literature has been concentrated in three areas—the effect of the expansion of democracy on Black participation in politics, the ability of Black Americans to elect representatives who look like them, and the ability of these Black representatives to pass policies that Black constituents favor once in office.

Rogowski (Reference Rogowski2018) examines the effect of the Freedman’s Bureau on Black social and political life and finds that areas where Freedman’s Bureau offices were located were associated with significantly higher male voter turnout in elections prior to Jim Crow. Freedman’s Bureau offices also contributed to greater substantive outcomes for Black Americans including higher literacy rates, better labor force outcomes, and higher socioeconomic status. Black representatives also contributed to substantive policies for Black Americans during Reconstruction by providing greater public finance opportunities, increased Black literacy, and more liberal support on general and racial policy issues (Cobbs and Jenkins Reference Cobb and Jenkins2001; Logan Reference Logan2020). Hahn (Reference Hahn2005) notes that many Black Americans were elected to office during the Reconstruction era. Chacón, Jensen, and Yntiso (Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021) find that this is directly related to federally implemented changes meant to enforce Black participation in elections. The authors find that areas where federal troops were located to ensure that Black men could participate in elections were more likely to elect Black men to state legislatures and constitutional conventions.

The VRA also drastically changed the way that Black Americans participated in politics. States that the federal government required preclearance oversight noticed increases in overall turnout and registration (Ang Reference Ang2019; Cascio and Washington Reference Cascio and Washington2014). These changes in turnout are seen when comparing counties that require preclearance to those that do not in North Carolina and contribute to changes in electoral outcomes—Democratic vote share increased in locations that required federal oversight over elections (Fresh Reference Fresh2018). The VRA also contributed to Black substantive representation by exhibiting differences in Black Americans’ share of public spending (Cascio and Washington Reference Cascio and Washington2014). Representatives in Congressional districts that required federal oversight over elections were also more likely to support Black interests (Schuit and Rogowski Reference Schuit and Rogowski2017). Finally, the VRA led to increased Black descriptive representation. Davidson and Grofman (Reference Davidson and Grofman1994) find that locales that changed from at-large to single-member districts due to provisions from the VRA were more likely to have Black Americans elected to office. Shah Marschall and Ruhil (Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013) find that Section 5 coverage increased the probability of having a Black representative in city and county councils, while Bernini, Facchini, and Testa (Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023) find that Section 5 coverage led to the increase of Black Americans on county councils in the South.

The Federal Enforcement of the 15th Amendment

We argue that the federal government must provide additional measures that enforce the 15th Amendment to ensure a multiracial democracy. By multiracial democracy, we not only mean the participation of Black Americans in politics but also the ability of Black Americans to choose the candidates they want to represent them, which, in many cases, are Black representatives. While an age-old question, we think this question merits further consideration for a couple of reasons. First, previous work has considered this question by only looking at the effect of democratic expansion during Reconstruction or after the VRA separately. We argue that the same process of the federal enforcement of a constitutional right is happening in these two time periods and should be considered together.

Second, previous work has examined the effect of federal enforcement of the 15th Amendment on Black representation for a subset of elected positions. Chacón, Jensen, and Yntiso (Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021), for example, only examine Black state legislators and elected officials in state constitutional conventions during Reconstruction. Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil (Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013) only examine Black representatives in city and county councils. Bernini, Facchini, and Testa (Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023) only examine local elected officials and only find an effect between federal preclearance and Black members in county councils and not municipal and school board offices. While Black representation has steadily increased at the local level (Sonenshein Reference Sonenshein2016), questions persist about the ability of expansions in democracy to influence Black representation at the state and federal levels. Much of the data on Black representation is hard to capture, or worse, nonexistent. While previous work made important conclusions about Reconstruction, the VRA, and representation, our new dataset provides a greater universe of cases and allows us to examine the effect of federal enforcement at the local, state, and federal levels.

Third, our analysis in both Reconstruction and the VRA covers a greater period of time than any previous work to our knowledge. Chacón, Jensen, and Ynitso (Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021) analyze how military intervention affects Black delegates to constitutional conventions in 1867 and 1869 and the number of African American representatives in each state’s lower chamber from 1868 to 1880. We instead have data on Black representatives from 1866 to 1912. Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil (Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013) analyze the direct effect of Section 5 on Black representatives on city and county councils in 1986, 1991, 1996, 2001, and 2006. Bernini, Facchini, and Testa (Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023) analyze the effect of Section 5 on Black representatives in local offices from 1962 to 1980. The authors uniquely include Black representatives prior to the passage of the VRA. We, however, have data on Black representatives after the passage of the VRA from 1969 to 1993. This is important because prior work only tests the effect of the VRA before (Bernini, Facchini, and Testa Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023) or after (Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013) the 1982 amendments. The 1982 VRA amendments extended majority-minority districts, which greatly increased Black representation. Our analysis can capture the effect of Section 5 on Black representation before and after the creation of majority-minority districts.

Our analysis on the VRA in particular is unique from previous work because we focus on Section 5 of the VRA’s ability to increase Black representation (Schuit and Rogowski Reference Schuit and Rogowski2017). Section 5 is typically seen as a way to increase Black participation (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes2022). Other work has attempted to understand whether Section 5’s unconstitutional status has led to a decrease in Black participation (Komisarchik and White Reference Komisarchik and White2024). We take this work a step further by questioning how Section 5’s ability to increase participation in turn increased Black representation.

Finally, our VRA analysis is unique because of the novel dataset of post-VRA officeholding. We gather a large dataset of Black elected officials from the South from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. We are the first to digitize the entire roster for Southern states. These rosters include the level of office including federal, state, county, city, judicial, and education elected positions. The rosters also include the year the elected official was elected and served in office, the address of their position, and Black elected officials from 1969 to 1993. Ultimately, we reach similar conclusions that previous scholarship has found in the South (Bernini, Facchini, and Testa Reference Bernini, Facchini and Testa2023; Chacón, Jensen, and Ynitso Reference Chacón, Jensen and Yntiso2021; Shah, Marschall, and Ruhil Reference Shah, Marschall and Ruhil2013) and the North (Grant Reference Grant Keneshia2019).

Empirical Strategy

We seek to understand how democratic expansion and state building lead to the election of Black representatives. We test this during Reconstruction and after the passage of the VRA. To do so, we create a dataset that gives us information about democratic expansion, an examination of Black Americans’ ability to access the ballot, and Black officeholders in each time period. Our dependent variable is Black officeholders. For both the Reconstruction and VRA time periods, we have hand-coded information on thousands of Black elected representatives collected originally in Foner’s Freedom’s Lawmakers (1993) (for the Reconstruction period) and several data repositories collected by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Affairs on Black officeholding after the passage of the VRA. Our independent variable is democratic expansion. To measure democratic expansion, we use data on federal troop locations collected by the Mapping Occupation Project during Reconstruction and data on locations where jurisdictions had to preclear their elections by the Department of Justice in the post-VRA era.

We believe that the size of the Black population is also an important factor to account for in examining its effect on Black representation. Previous literature has shown that the size of the Black population is directly connected to the presence of Black elected officials (Fraga Reference Fraga2016; Marschall, Ruhil, and Shah Reference Marschall, Ruhil and Shah2010) and that there exists a connection between Black turnout and Black representation (Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Hayes et al. Reference Hayes2022). We see one of the primary goals of a multiracial democracy is increasing the ability of Black Americans to participate in politics and use the size of the Black population to account for this. In each analysis, we include the size of the Black population to both control for existing factors within each county and provide an estimate of the ability of Black Americans to participate in politics.

Our primary hypothesis is that the enforcement of the 15th Amendment, coupled with the ability of Black Americans to participate in politics, leads to the election of Black elected officials. In the Reconstruction era, we expect that the interaction between counties where federal troops were located and the size of the Black population will be positively associated with Black officeholding. In the post-VRA era, we expect that the interaction between counties and the federal government requires preclearance over elections and the size of the Black population will be positively associated with Black officeholding.

Our primary modeling strategy uses fixed effects for county-year units to understand the effect of the enforcement of the 15th Amendment on Black officeholding in covered and uncovered counties. The central strength of this modeling strategy is that we demonstrate the temporal effect of adopting these policies (or more accurately, being affected by these policies) while simultaneously controlling for unobserved heterogeneity between counties and years. In this regard, we conceptualize the enforcement of the 15th Amendment—the presence of troops in the South during Reconstruction and VRA coverage after 1965—as a “treatment” with substantial heterogeneity in treatment intensity across units and time.

Reconstruction Study: The Effect of Federal Enforcement on Representation during Reconstruction

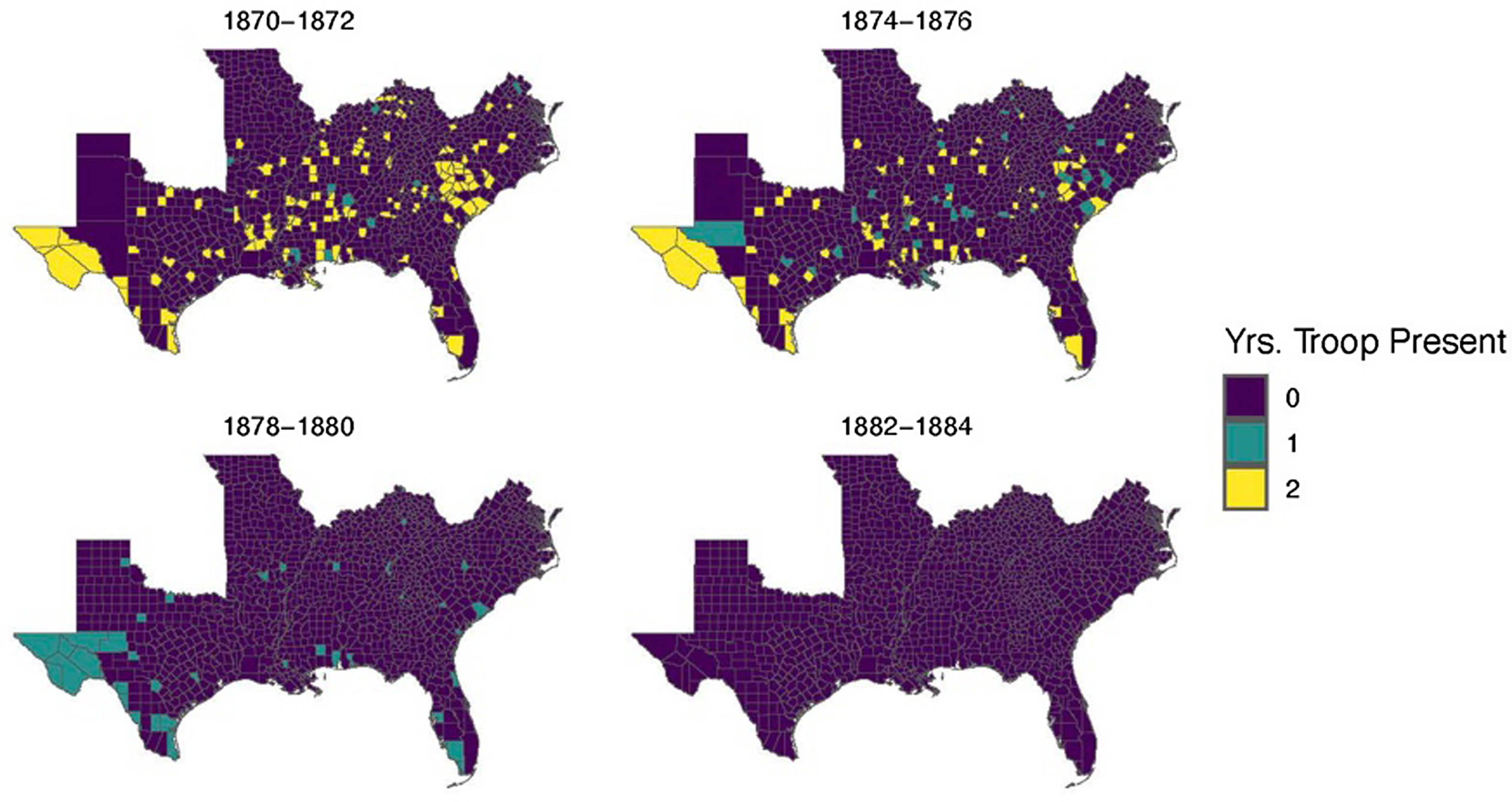

The first study tests whether the presence of federal troops that ensured Black male participation in elections increased Black officeholding. Data on federal troop postings during Reconstruction come from Downs and the Mapping Occupation project (Downs Reference Downs2015; Downs and Nesbit Reference Downs and Nesbit2015). Downs and Nesbit (Reference Downs and Nesbit2015) provide precise troop locations and a measure of troop mobility. Troop mobility provides information not only about troop location but also the distance that federal troops could potentially travel in a single day and the places where freedmen might travel to make a complaint, which is a day’s journey from the troop location. This troop mobility is called a troop posting’s “buffer zone.” Buffer zones include counties with a troop presence and any county center point that is within 30 miles of a troop post. We geolocate these troop postings and buffer zones into counties by intersecting the troop point locations for every year of their existence with yearly county shapefiles drawn from the Newberry Library’s Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. Based on Downs and Nesbit’s report, it is reasonable to assume that the placement of army outposts is unrelated to our political variables of interest, especially considering that Black political participation and officeholding were nonexistent prior to Reconstruction reforms. The appendix lists correlations between our measures of troop access and Black population and shows that no two measures correlate at or above 1. Figure 1 maps federal troops postings from 1870 to 1884 and shows that while many counties had federal troop oversight during the 1870–72 election, federal troop oversight decreased during each subsequent election, with no federal troops present in the South in the 1882–84 election.

Figure 1. Federal troop presence during Reconstruction, 1870–84.

Data on Black officeholding during Reconstruction come from Foner (Reference Foner1993). This directory includes the city or county of service, term of service, and office(s) held of all Black officeholders from 1866 to 1912. It includes officeholders at the federal, state, county, and local levels. The dataset also includes information about the party of the officeholder. We use the Newberry Library’s atlas of shapefiles to locate the officeholders in counties. Figure 2 graphically represents Black officeholders in the South during the same election years demonstrated for troop presence. A similar trend follows where many Black officeholders were elected in the 1870–72 election, with fewer in the subsequent elections. Finally, demographic data for both the Reconstruction Era and years after the VRA come from the U.S. decennial census. Election and turnout data for both periods come from the United States Historical Election Returns Series.Footnote 1

Figure 2. Black officeholders during Reconstruction, 1870–84.

Reconstruction Study Results

We argue that locations where troops were deployed lead to Black access to the ballot and in turn lead to the election of Black representatives. We model this effect using the interaction of troop presence and proportion Black on the number of Black representatives in Table 1. Our model uses county-year fixed effects to estimate the effect of the interaction between the proportion of a county that is Black and the presence of federal troops on Black officeholding. The county fixed effect controls for the fact that in different states, different numbers of elected officeholders exist. The model also includes a control for total population (logged). In Table 1, we find a positive interaction effect between the size of the share of the Black population in a county and the presence of troops. While the presence of troops in a county has a negative relationship with Black officeholders without accounting for Black population, and the proportion of a county that is Black has a positive relationship with Black officeholding without accounting for troop presence, the effect of Black population share and troop presence is magnified by one another. Results show that about seven Black officeholders are elected as the proportion in the county that is Black increases and troops are present.

Table 1. The effect of troop presence and proportion Black on Black officeholders

Note: *p<.10 **p<.05 ***p<.01.

In Table A3 in the appendix, we show that being within a 30-mile radius of federal troops also leads to the election of Black representatives. As the proportion in the county that is Black increases and when a locale is in the troop presence buffer zone, there are about three Black officeholders elected. Tables A3 and A4 in the appendix also show the impact on Black representation at different levels of government. While the interaction between troop presence and proportion of the county that is Black is statistically significant at all levels of government, there are substantively significant differences. Results show that about five state officeholders are elected to office as the proportion in the county that is Black increases and troops are present. Only one Black county officeholder is elected, and fewer than one Black local, police, education, and federal representatives are elected under the same circumstances.

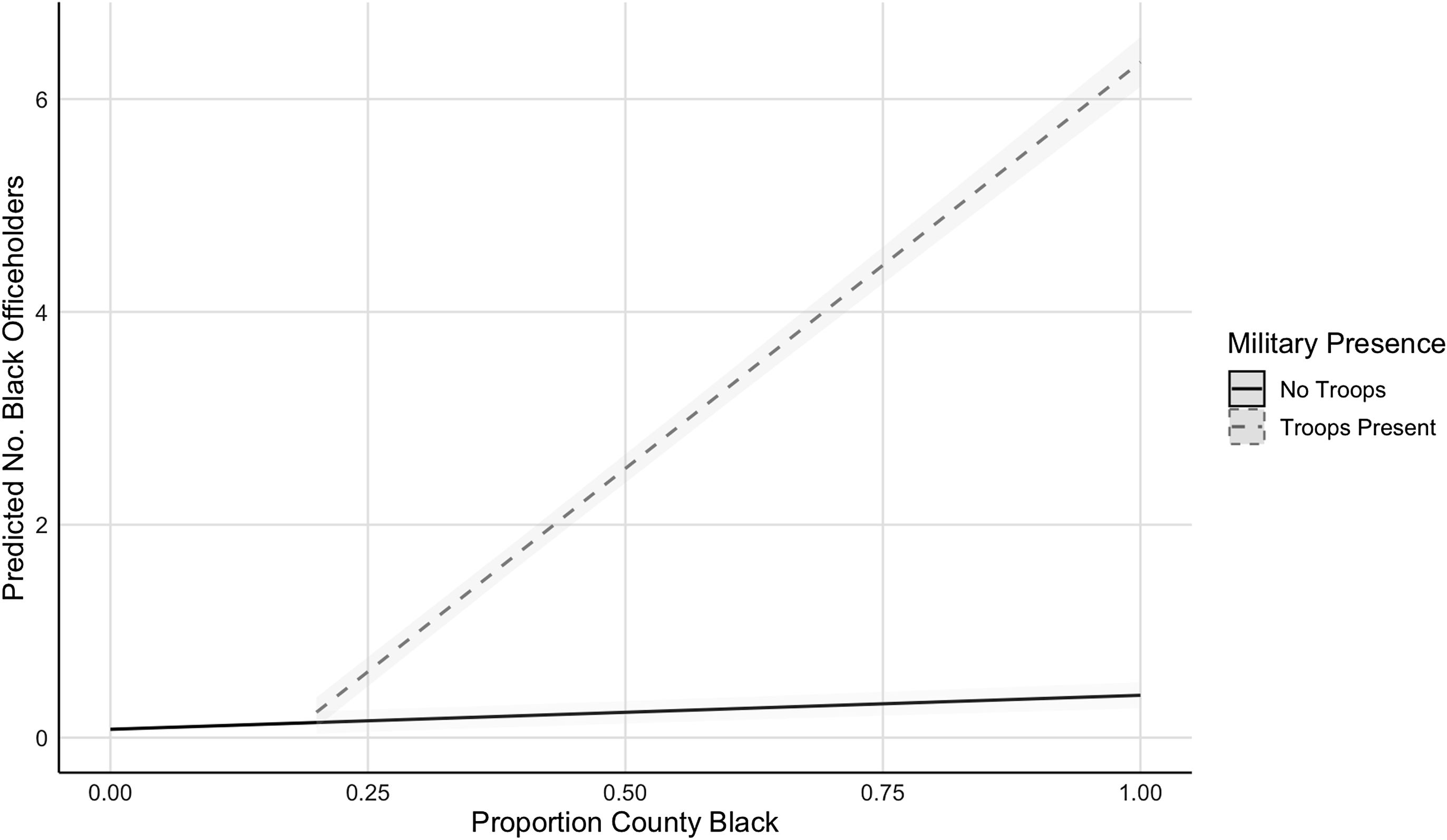

Figure 3 graphically depicts the effect of Black population share and troop presence modeled in Table 1. Figure 3 shows that when troops are not present in a county, Black officeholding increases only minimally as the Black proportion in a county increases. When troops are present in a county, though, Black officeholding increases as the proportion Black in a county increases. For example, counties that were about 20% Black during this period are predicted to have elected no Black officeholders, regardless of the presence of federal troops. When the proportion of county residents who are Black rises to roughly 50%, however, counties with troop presence are predicted to elect between two and three Black officeholders, whereas counties without troops are still predicted to elect no Black officeholders. The discrepancy between counties that did and did not have occupying troops grows as the Black proportion of a county’s residents increases. Counties that are 75% Black are predicted to elect about five Black officeholders, whereas counties with similar racial demographics but no troops are still predicted to elect less than one.

Figure 3. Predicted effect of Black officeholders on the proportion of county black and occupation status.

VRA Study: The Effect of Federal Enforcement on Black Access to Participation and Black Representation post-VRA

Next, we turn to demonstrating the same relationship between the federal enforcement of the 15th Amendment, the ability of Black Americans to participate in elections, and Black representation after the implementation of the VRA. We model the effect of VRA Section 5 coverage interacting with the proportion in a county that is Black to understand the effect of the enforcement of the 15th Amendment on Black officeholding.

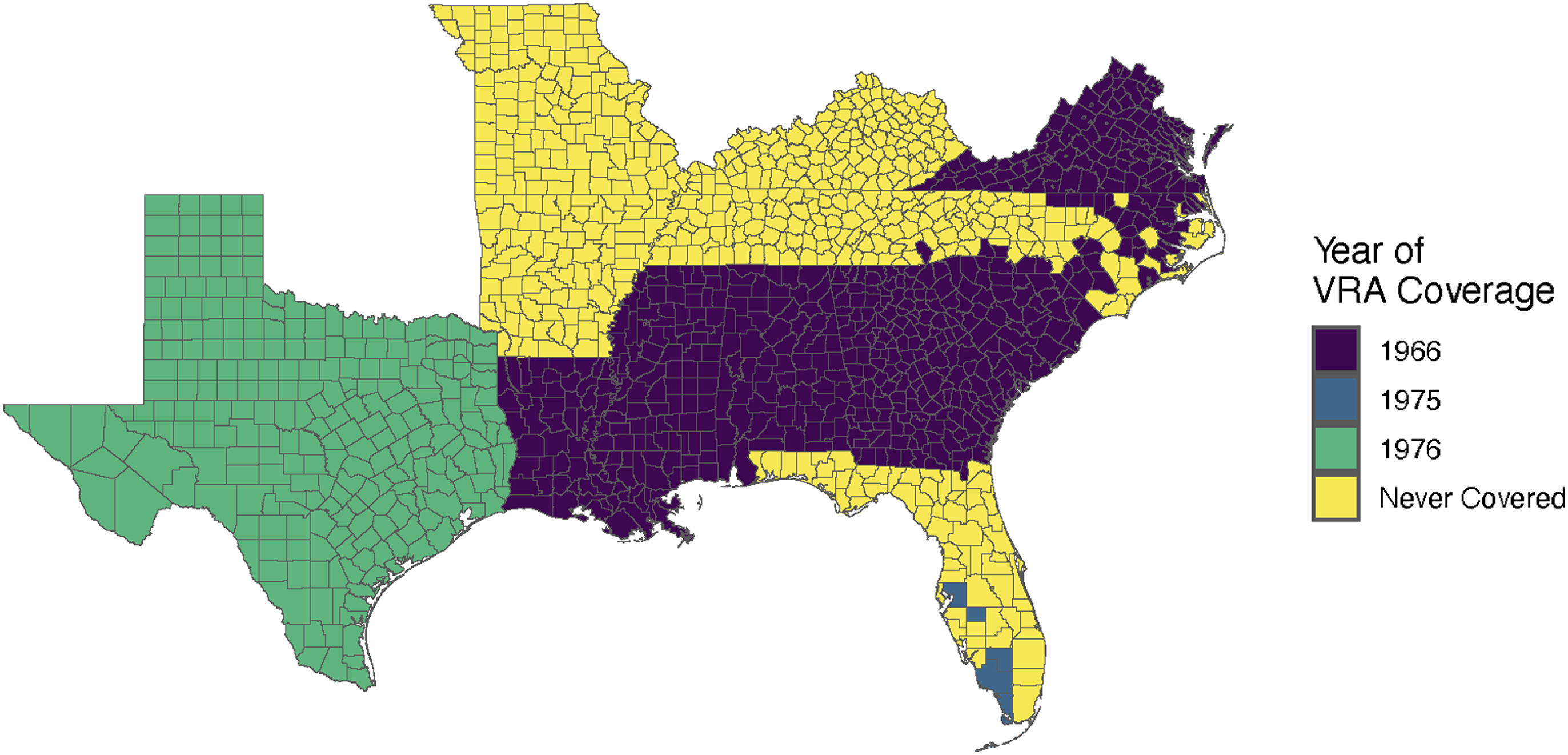

In the post-VRA era, we measure whether a state or county required preclearance from the federal government to hold elections. To create the dataset for the VRA, we draw information about Black officeholders after the VRA and the location of areas that had federal preclearance after the passage of the VRA. Data on Section 5 VRA coverage at the county level come from U.S. Department of Justice.Footnote 2 These data show that the federal government required many Southern states to preclear their elections. We compare covered jurisdictions from formerly Confederate Southern states, which are Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia, to states not covered by Section 5 of the VRA, which are Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee. In Florida and North Carolina, we compare covered counties to counties that are not covered by Section 5 of the VRA. We do an additional test comparing VRA coverage in the Mississippi Delta to similar counties that were not covered by the VRA in Arkansas. Additional information about VRA coverage in these states is included in the appendix. Figure 4 maps Section 5 coverage of the VRA by state and year.

Figure 4. Section 5 VRA coverage.

Data on Black officeholders come from the Joint Center’s Roster of Black Elected Officials in the Southern States. We are the first to digitize the entire roster for Southern states. These rosters include the level of office including federal, state, county, city, judicial, and education elected positions. The rosters also include the address of Black officeholders for every year, which we geolocate into counties using the Newberry Library’s collection of historical county boundaries.

Unlike the placement of troops that occurred across the South in areas with varying sizes of Black populations, states or counties that had federal oversight of elections after the passage of the VRA did so because of restrictions to the franchise that were clearly tied to previously existing racial exclusion. For VRA coverage, this means that most states in the South had to preclear their election procedures from 1965 until the Supreme Court decision via Shelby v. Holder in 2013 that ended federal oversight in elections. The VRA had very little spatial or temporal variation within the South (unlike the case of federal troops in the South during Reconstruction that varied in location across several years). After reporting overall estimates of the relationship between the VRA and Black officeholding, we employ two quasi-experimental designs: first, comparing counties within North Carolina and Florida that did and did not receive Section 5 coverage and then by comparing counties with similar characteristics across the Mississippi River in Mississippi and Arkansas.

VRA Study Results

In our empirical strategy, we use county-year fixed effects and an indicator for VRA coverage, modeling that VRA coverage affected different counties in different years as states and counties came in and were bailed out of VRA coverage. For every state-county-year, we regress the total number of Black officeholders on the interaction between VRA coverage and the share of a county that is Black and control for total population. We compare counties covered after the passage of the VRA to counties not covered for every year in our analysis.

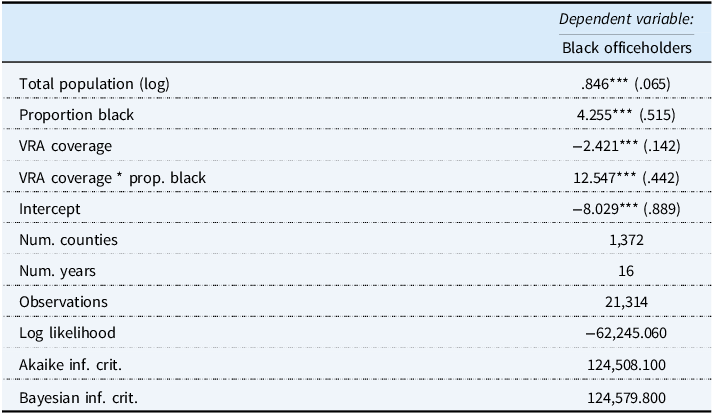

The aggregate model that covers 1,372 counties over 16 election cycles, shown in Table 2, shows a statistically significant and substantively important positive association between VRA coverage, proportion Black, and Black officeholding. Results show that when the proportion of the county that is Black increases, without accounting for VRA coverage, about four Black officeholders are elected in that county in any given year. When a county requires VRA coverage, without accounting for the proportion in the county that is Black, Black officeholding decreases by about two officeholders. When we look at the main interaction effect that accounts for VRA coverage and the ability for Black voters to participate in elections, however, there are about 12 more Black elected officials elected in a county in any given year.

Table 2. The effect of VRA coverage and proportion Black on Black officeholders

Note: *p **p ***p <.01

Table B2 in the appendix shows the differences in representation at different levels of government. Table B2 first shows that the interaction between VRA coverage and the proportion of the county that is Black is not statistically significant for federal offices. This follows similar work that shows that Black representation at the federal level does not affect Black turnout (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes2022). For all other levels of office, though, there is a statistically significant effect of the interaction between VRA coverage and the proportion of the county that is Black on Black representation, although there exist substantive differences. Following results from the reconstruction analysis, there are more Black officeholders at the local level than state and federal levels. There are about five Black city officeholders, two Black county and education officeholders, one Black judicial officeholder, and fewer than one Black state officeholder.

Figure 5 demonstrates the substantive effect of VRA coverage for all Black officeholders throughout the South. Figure 5 illustrates the predicted levels of Black officeholding for counties covered and uncovered based on the proportion of the county that is Black. Without VRA coverage, the share of a county that is Black has no discernible predicted effect on Black officeholding. With VRA coverage, the predicted effect is substantial, rising from roughly two Black officeholders for counties with a quarter of their population Black to eight Black officeholders for counties in which 75% of the population is Black.

Figure 5. Predicted effect of Black officeholders on the proportion of county black and VRA coverage.

The Effect of the VRA on Black Officeholders in North Carolina and Florida

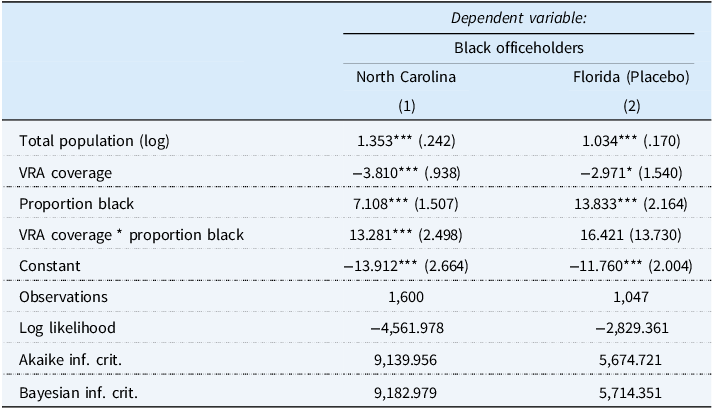

Next, we examine how variation in VRA coverage affected Black officeholding in states with incomplete coverage. Previous work used a similar difference-in-difference research design exploiting variation in county coverage in North Carolina to demonstrate that Section 5 coverage of the VRA increased Black voter registration by 14–19 percentage points (Fresh Reference Fresh2018). Here, we use the same variation in VRA coverage to test whether coverage also contributed to Black officeholding. We use the same modeling strategy above that estimates the effect of VRA coverage by regressing the total number of Black officeholders in a county on an indicator for VRA coverage using ordinary least squares and fixed effects by county and year and controlling for the total population in a county, which varies by year. We compare the effect of variation in VRA coverage and the ability of Black Americans to participate in elections in North Carolina to Florida. We treat Florida as a placebo test because while VRA coverage was applied in certain counties in Florida, it was applied in response to language discrimination as a barrier to voting, not racial discrimination.Footnote 3 As the language provision of the VRA in Florida is aimed at the incorporation of mainly Spanish speakers, we do not expect the interaction of VRA coverage and proportion Black to be associated with the increase of Black officeholders in the South.

Table 3 shows that the interaction between VRA coverage and the proportion that a county is Black has a statistically distinguishable and positive average treatment effect on the number of Black officeholders in North Carolina. We see a similar relationship in North Carolina that we do across the South: (1) a negative relationship between VRA coverage and Black officeholding without accounting for the proportion of the county that is Black, (2) a positive relationship between the proportion of the county that is Black on Black officeholding when not accounting for VRA coverage, and (3) a statistically significant positive relationship between the interaction of VRA coverage and the proportion of the county that is Black on Black officeholding. On the other hand, the interaction effect in Florida, where VRA coverage aimed at the incorporation of mainly Spanish language speakers, and not Black Americans, is not statistically significant. In Florida, counties with a greater proportion of Black residents do elect more representatives, but as predicted, this relationship is not affected by VRA coverage.

Table 3. The effect of VRA coverage and proportion Black on Black officeholders in North Carolina and Florida

Note: *p **p ***p <.01.

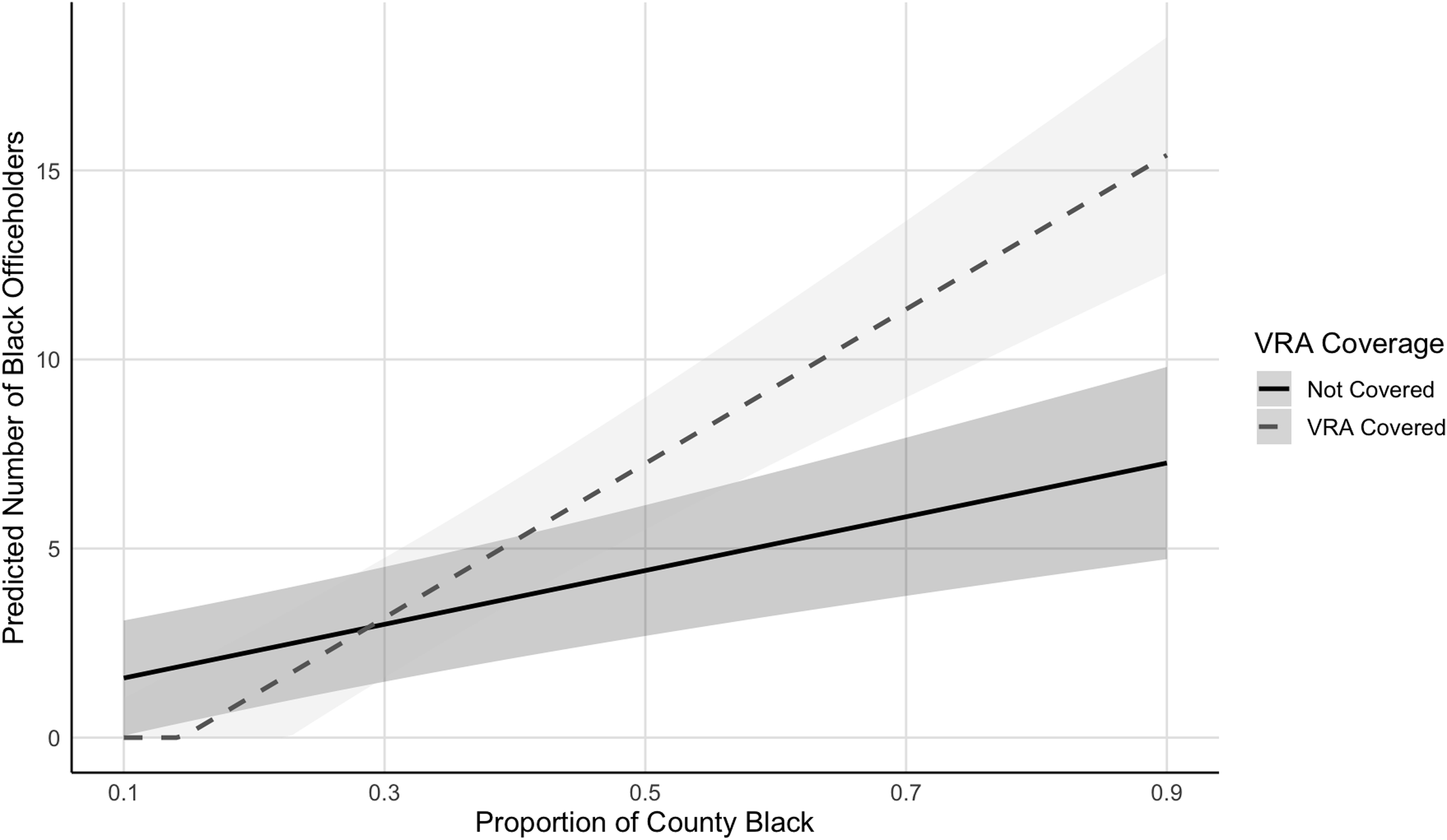

Figure 6 demonstrates the substantive effect of VRA coverage in North Carolina by illustrating the predicted levels of Black officeholding for counties covered and uncovered by the VRA based on the proportion of the county that is Black. Without VRA coverage, as the share of a county that is Black moves from zero Black Americans to 60% of the county that is Black, there is an increase from zero to five Black elected officials. While this increase is notable, when the VRA requires preclearance over counties in North Carolina, we see a much more substantive effect on Black officeholders. With VRA coverage, the predicted effect is substantial in North Carolina, rising from roughly one to two officeholders for counties with a quarter of their population that is Black to nearly seven when 50% of the population is Black. Figure 6 shows that when 60% of the population is Black, we expect nearly 10 Black officeholders.

Figure 6. Predicted effect of Black officeholders on the proportion of county black and VRA coverage in North Carolina.

The Effect of the VRA on Black Officeholders in Mississippi and Arkansas

As an additional test of our theory in the post-VRA time period, we compare counties in Mississippi that required federal preclearance to adjacent and demographically similar counties in Arkansas that did not require federal preclearance for elections. The counties in these neighboring states are similar in many ways, making this comparison feasible. The counties along the Mississippi River are rich in alluvial soil, which made them hospitable to plantation farming and a dependence prior to the Civil War on chattel slavery. In 1860, Chicot County, Arkansas, had about 9,000 residents, of whom 7,500 were enslaved. Directly across the Mississippi River in Washington County, 14,467 of the 15,679 residents were enslaved. Although the counties were in different states, their sparse population density, dependence on slavery, and access to the Mississippi River brought the counties of the Mississippi–Arkansas border into the shared region that James C. Cobb called “the most southern place on earth.”

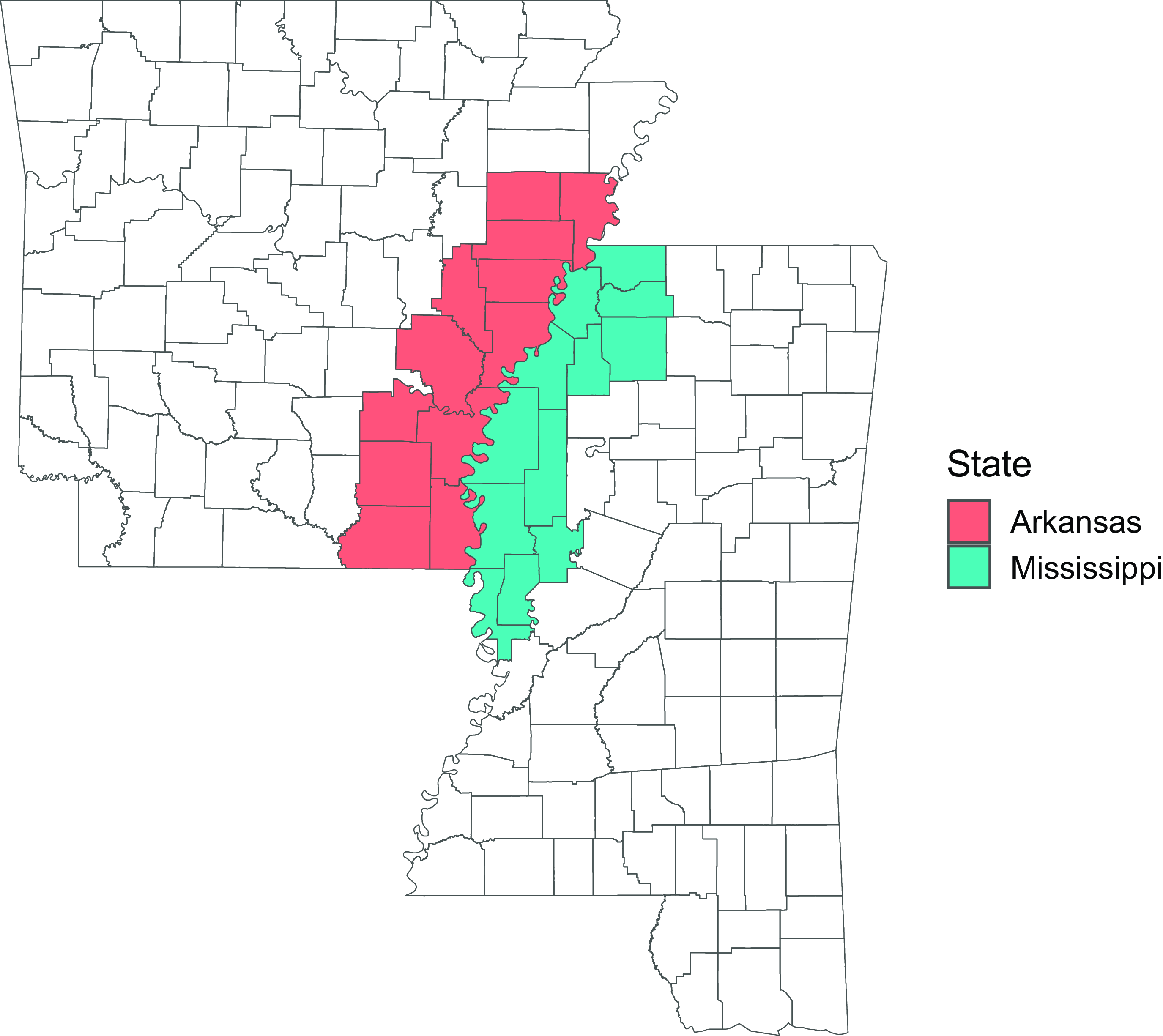

While these counties still had a lot in common in 1965, Mississippi was brought under the preclearance requirement of Section 5 of the VRA, while the much whiter Arkansas, which did not have a “test or device needed to vote,” was not. Because these counties have similar histories of economic, political, and demographic development, we use the treatment of the Mississippi Delta counties with VRA coverage as a quasi-experimental setting to test the effect of increased Black turnout (made possible by the VRA) on Black officeholding. Figure 7 maps the counties included in this study, with Mississippi’s Delta counties highlighted in blue and Arkansas’ Delta counties highlighted in red.

Figure 7. Map of neighboring counties in Mississippi and Arkansas.

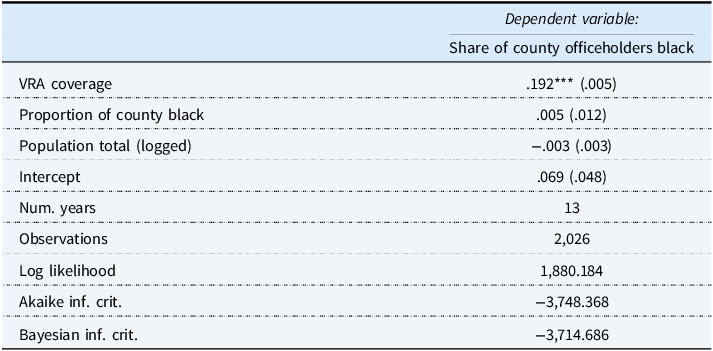

Our data on population and demographics are at the county level; therefore, we are interested in Black officeholding at the county level. However, the structure of local governance varies from state to state; offices that exist at the county level in one state may not exist in another. To make comparisons between a state like Arkansas, in which county boards varied in size from 9 to 15 (depending on population), and Mississippi, in which counties all had five-person boards of county supervisors, we look at the share of county officeholders who were Black.

The historical context and availability of the data make a true discontinuity study impossible. As Figure A3 in the appendix shows, Black officeholding rates between Arkansas and Mississippi Delta counties were equal prior to the VRA, but this is because they were both zero. Additionally, while we control for differences in local political context like the number of possible Black officeholders in a county (this is built-in to our dependent variable of share of officeholders Black), there may be differences in state-level politics that are confounding our estimation of the effect of VRA coverage. Our model resembles a difference-in-difference estimator, though because there is no pretreatment variation, we are essentially estimating a difference in means while controlling for the proportion of a county that is Black and a county’s population. We also include a year fixed effect to control for any unobserved heterogeneity between years like a particularly salient presidential election or particularly low-turnout midterm election.

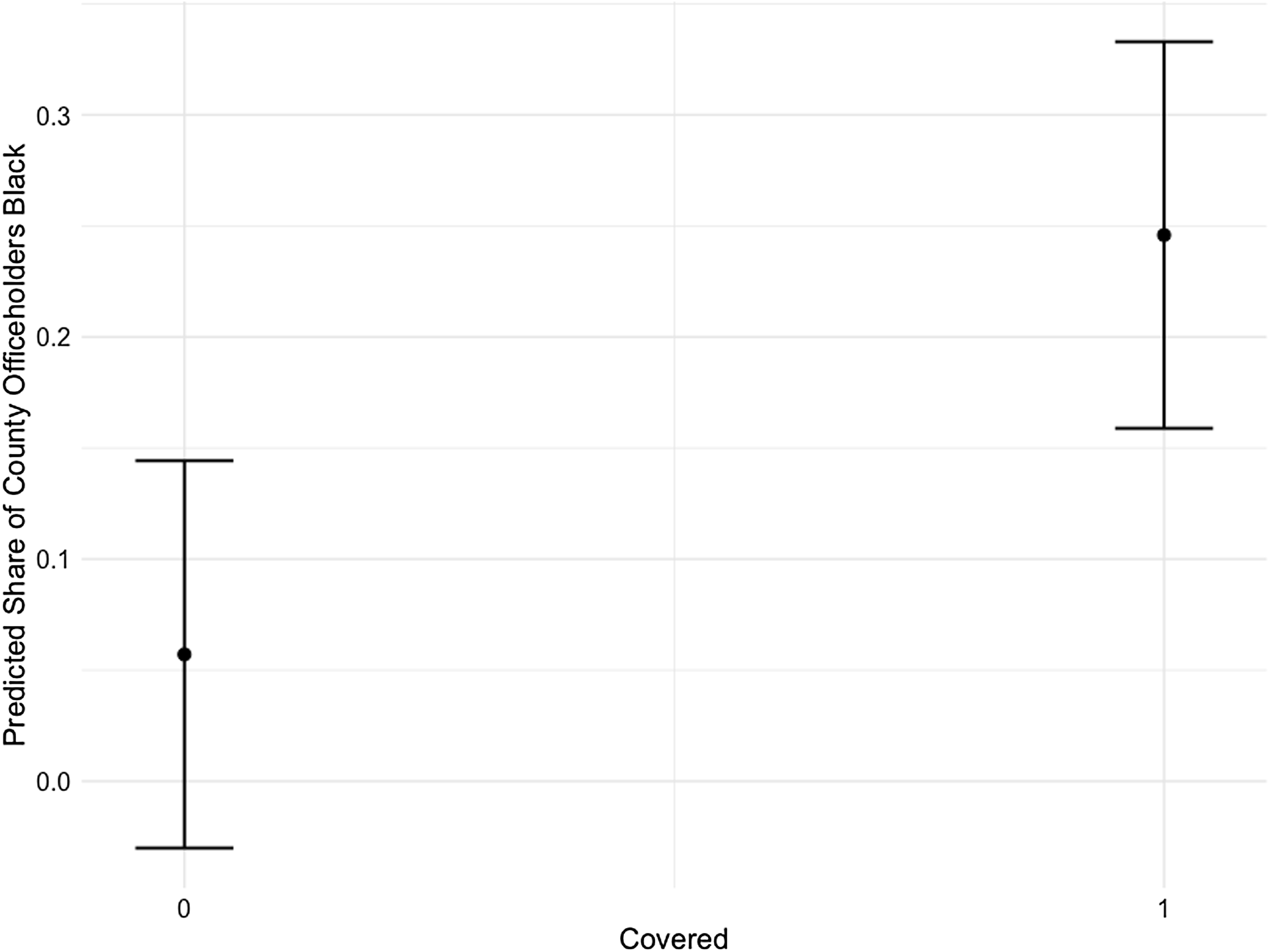

Our model estimates an average treatment effect for the treated VRA counties. We find in Table 4 that counties with VRA coverage in the Mississippi Delta have a 19% increase in the share of the county officeholders that are Black compared to the counties in the Arkansas Delta. This relationship is visualized in Figure 8. Held at the sample mean levels of Black population share and election turnout, a county without VRA coverage in Arkansas is estimated to have roughly 6% of its county governing board be Black. On the other hand, a county with the same share of population Black but with VRA coverage in Mississippi is expected to have about 25% of its county governing board consisting of Black Americans.

Table 4. The effect of VRA coverage on share of county Black officeholders in Mississippi and Arkansas

Note: *p **p ***p <.01.

Figure 8. Predicted share of county officeholders black by VRA coverage status in the Mississippi and Arkansas Delta.

In Appendix B1, we present an event study of how the VRA affects Mississippi and Arkansas border counties. In Figure B3, we show a steady increase in Black officeholding in Mississippi relative to Arkansas border counties. By 25 years after VRA implementation, Mississippi border counties had about 59 percentage points higher share of Black county officeholders compared to similar Arkansas counties, controlling for Black population share and total population. Appendix B2 provides further support that the VRA was necessary for Black officeholding. In Figure B4, we compare Black officeholding along the Mississippi–Tennessee border. The effects are strongest in the Mississippi–Arkansas comparison, but we find similar effects for the Mississippi–Tennessee border. Finally, in Figure B4 we include the border between Mississippi and Alabama as a placebo test. Because Alabama was also covered by the VRA, we should not (and do not) see any differences across this border segment.

Our VRA analysis reveals three key findings about the relationship between the enforcement of the 15th Amendment, ballot access, and Black representation. First, across both our aggregate Southern analysis and North Carolina case study, we found a consistent pattern. The proportion of Black residents in a county positively correlates with Black representation, independent of VRA coverage. VRA coverage alone shows a negative relationship with Black representation when the Black population isn’t considered. The interaction between VRA coverage and the Black population produces the strongest positive effect on Black representation. Second, increased Black officeholding correlates with VRA coverage only in jurisdictions where the VRA specifically targeted racial discrimination. This is demonstrated by our comparison between North Carolina counties (where VRA coverage addressed racial discrimination) and Florida counties (where coverage addressed language discrimination). The interaction between the Black population and VRA coverage significantly increased Black officeholding only in North Carolina. Third, our comparison of adjacent counties in Mississippi (covered by the VRA) and Arkansas (not covered by the VRA) with similar racial demographics confirms that counties under VRA coverage elected substantially more Black representatives.

Conclusion

In this paper, we argued that descriptive representation in the South is dependent on legal enforcement of the right to vote and policies that increase access to the ballot. Without federal troops during Reconstruction or the VRA in the Civil Rights Era, we have little reason to believe Black officeholding would have proliferated throughout the South at all. We tested our argument in two settings: first, with application to troop presence implemented during the Reconstruction Era, and second, after the passage of the VRA. In the Reconstruction analysis, we find that both proactive protection of democratic participation and Black access to the ballot were necessary for Black officeholding. Similarly, in the VRA analysis, we find that Black representation stems from places with federal oversight over elections and counties that had a larger proportion of Black Americans. By showing that the federal enforcement of multiracial democracy led to the election of Black representatives in two time periods, we provide extensive support for our claims.

As questions of participation and representation are some of the central concerns in American politics research, we believe this paper is important for understanding how democracy functions, what influences political groups to participate in politics, and political representation. The future of the VRA has been threatened by recent Supreme Court cases: Shelby County v. Holder (2013) gutted the preclearance provision of the VRA; Brnovich v. DNC (2021) reinterpreted Section 2 of the VRA, making it harder to block discriminatory voting laws; and Merrill v. Milligan (2023) attempted to halt the creation of majority-minority districts. Moreover, other rulings on racial and partisan gerrymandering like Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP (2024) reflect additional pathways to mitigate Black representation. Our paper concludes that democratic initiatives like the VRA are imperative for not only the incorporation of Black voters into the political system and Black candidates into elected office but also the maintenance of Black participation and representation. Should the VRA be completely gutted, our conclusions suggest that it would be detrimental to the future of Black political life. More work should take up the cause to answer the question of what may happen to Black participation and representation in a world where democratic interventions diminish.

We believe that much of the newly digitized data used in this paper creates a unique dataset useful for scholars in state and local government, urban politics, representation, and race, ethnicity, and politics. Our data create a nearly complete historical record of Black officeholding in the South from 1866 to 1993 (1912–69 is absent from this record, but we can assume that there were relatively few Black officeholders during this time due to the Jim Crow system barring most Black Americans from political incorporation). As our data include federal, state, and local officeholders, it can answer questions concerning the effect of Black officeholding in local government (Marschall and Ruhill Reference Marschall and Ruhil2007) and Black officeholding in the courts (Scherer and Curry Reference Scherer and Curry2010; Welch, Combs, and Gruhl Reference Welch, Combs and Gruhl1988) and can answer descriptive questions about Black officeholding through space and time (Warshaw, Benedictis-Kessner, and Velez Reference Warshaw, de Benedictis-Kessner and Velez2022).

This framework also has the potential to explain the increase of representatives that align with the interests of a newly incorporated group among a wide variety of groups that have been granted suffrage extension. One clear implication of this is testing the impact of the VRA language provisions on turnout and representation for Latino and Asian Americans (Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa2005; Marschall and Rutherford 2015). Another way to extend this paper is to examine the incorporation of women into the political sphere after the 19th Amendment expanded the electoral franchise to white women in the United States (Morgan-Collins Reference Morgan-Collins2021). This framework is also applicable outside of the U.S. context.

While our data are historical in nature, primarily due to the limited available data on Black officeholding, we contend that this framework explains contemporary Black representation. We believe that contemporary federal interventions are still essential to Black officeholding. To fully test whether this is the case, future work should consider the effect of Shelby County v. Holder (2013) on Black officeholding—recent work has tested the implications of this case on Black participation (Komisarchik and White Reference Komisarchik and White2024; Morris and Miller Reference Morris and Miller2024). Although this case eliminated the use of Sections 4 and 5 of the VRA, there are other ways to measure how racial and ethnic groups can access the ballot and its effect on Black officeholding. For example, Grumbach (Reference Grumbach2023) measures democratic variation within states in the twenty-first century. Future work should consider how variation in democracy across states impacts Black officeholding.

Lastly, we note limitations in the paper that future work should take up. For example, we do not test the direct effect of people moving in and out of districts due to migration, redistricting, or racial/partisan gerrymandering. We also only analyze the number of Black representatives elected in each county; we do not have information about the share of Black officeholders in each county, outside of the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta analysis. Finally, we note that we present results for Black representatives in each county at the local, state, and national levels. We do not have information about, for example, school district boundaries, police chief boundaries, city and county council boundaries, and so on. As a robustness check, we break the full results shown throughout the paper into representatives at each level of office, shown in Tables A4 and A5, and find that the interaction between the Black population and troop presence or VRA coverage does indeed lead to more representatives for Black county officials.

Our results show that the federal enforcement of the 15th Amendment creates the opportunity for Black Americans to participate in politics, which in turn allows newly enfranchised Black Americans to elect Black representatives. Ultimately, our results are obvious in hindsight: Reconstruction and the VRA increased Black access to the ballot and, in turn, Black officeholding. Yet Reconstruction failed, and the VRA is almost completely gutted. Demonstrating the importance of these major legislative victories remains an important task.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.33.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful comments received during presentations at the Midwest Political Science Association and the George Washington University American Politics Workshop. We are also grateful for the helpful comments from Leann McLaren, Randy Wagner, and the three anonymous reviewers. Finally, we are grateful to the Duke Archivist for assisting us in collecting and digitizing the data on Black representatives from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Affairs.

Funding statement

The authors did not receive any funding for this article.

Competing interests

None.