What is the purpose of public education?

For centuries, political theorists have argued that public education is essential to establishing democratic norms, the substantive knowledge required for political engagement, and a sense of fellow-feeling. For instance, John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill1859) suggests that citizenship education accustoms individuals to the notion of public interest; John Dewey (Reference Dewey1916) contends that in a democratic society, education teaches “the habits of mind which secure social changes without introducing disorder” (115); and W.E.B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1903b) argues that leaders need an education that teaches “intelligence, broad sympathy, knowledge of the world that was and is, and of the relation of man to it” (33-34). Contemporary theorists echo these sentiments; as Amy Gutmann (Reference Gutmann1999) argues, “by cultivating… deliberative skills and virtues, a democratic society helps secure both the basic opportunity of individuals and its collective capacity to pursue justice” (xiii). Education also helps citizens understand links between themselves, other members of society, and a shared greater good, and to envision democratic possibilities. Additionally, civic education has the potential to decrease racialized and gendered participation gaps and support broader, more equitable democratic engagement (Allen and Reich Reference Allen and Reich2013; Campbell and Niemi Reference Campbell and Niemi2016; Collins Reference Collins2009; Nelsen Reference Nelsen2021b; Zukin et al. Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Della Carpini2006).

But some argue that, in practice, public education does not live up to these ideals. Instead, they contend that it is primarily meant to train workers and cultivate obedient citizens; teach discipline, routinization, and docility; and foreground economic productivity rather than citizenship. (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis1976; Collins Reference Collins2009; Foucault Reference Foucault and Sheridan1977; Heitzeg Reference Heitzeg2015; Katz Reference Katz1995; Kozol Reference Kozol2005; Nasaw Reference Nasaw1979). These ends are, at the very least, in a different rhetorical register than skills like deliberation, mutual persuasion and reason-giving, reflection, moral autonomy, the pursuit of justice and equity, and the cultivation of shared interests.

Empirical evidence about educational outcomes further complicates the picture, with uneven educational outcomes and rates of political participation. The National Center for Education Statistics reports significant racial and ethnic disparities in reading, mathematics, and participation in postsecondary education (National Center for Education Statistics 2024). The U.S. Census reports significant disparities in voting; as of the 2020 presidential election, White non-Hispanic citizens voted at a significantly higher rate (70.9%) than did Black (62.6%), Asian (59.7%), or Hispanic (53.7%) citizens (United States Census Bureau 2021). There are many reasons that people who belong to minoritized racial and ethnic groups may be reticent or unable to engage in a broad range of democratic activities. These include reduced economic, social, and political capital; hostility; different access to a variety of political activities; and systemic disadvantage more broadly. Institutions can also play a key role, both in their structure and in the messages they send to constituents (Fraser and Honneth Reference Fraser and Honneth2004; Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2014; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady Reference Schlozman, Verba, Brady, Skocpol and Fiorina1999; Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Shelby Reference Shelby2016; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; Weaver, Hacker, and Wildeman Reference Weaver, Hacker and Wildeman2014; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010; Young Reference Young1990). Schools are one type of institution that can play an influential role in long-term outcomes, particularly since school curricula, environment, and discipline may also be linked to racialized and gendered experiences in students’ sense of political belonging, efficacy, and participation (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greene, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Campbell Reference Campbell2019; Nelsen Reference Nelsen2023; Niemi and Junn Reference Niemi and Junn2005).

With these differing and seemingly incompatible perspectives in mind, we ask: What role does the school environment play in the creation of citizens? How does the racial composition of a school affect the citizenship training students receive? In exploring these questions, we focus on the school environment, which profoundly shapes students’ experiences and expectations (Anyon Reference Anyon1980; Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Campbell Reference Campbell2019; Hayward Reference Hayward2000; Lareau Reference Lareau2011). Using evidence from charter school handbooks alongside theoretical analysis, we demonstrate notable racial differences in schools’ conceptions of citizenship. In particular, in charter schools where a majority of students are White, school handbooks tend to emphasize the democratic tradition and students’ ability to contribute agentially and authentically to a larger whole. Charter schools where a majority of students are non-WhiteFootnote 1 are more likely to use disciplinary language and emphasize the importance of following the rules.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, building from theoretical foundations, we discuss the potential impact of school environments on democratic outcomes. Second, we describe our dataset, methods of analysis, and results. We present a unique dataset of charter school demographics alongside the text of the school handbooks (Brown and Malloy Reference Brown and Malloy2025). Our results indicate differences along racial lines regarding language related to conceptions of citizenship in the handbooks of charter schools. While our goal is primarily to examine the theoretical implications of different types of school environments, this approach allows us to demonstrate this larger discursive pattern. Third, we engage in normative analysis through a close reading of selected charter school handbooks, focusing specifically on how charter schools present the democratic tradition, responsible citizenship, and productive citizenship. We conclude with a discussion of potential democratic ramifications of these racial disparities.

Educational Environment and Political Socialization

In addition to conveying substantive knowledge, schools have significant impact on students’ development through the “hidden curriculum,” in which “differing curricular, pedagogical, and pupil evaluation practices emphasize different cognitive and behavioral skills in each social setting and thus contribute to the development in the children of certain relationships to physical and symbolic capital, to authority, and to the process of work” (Anyon Reference Anyon1980, 90). Initially focused on classroom environments and class distinctions between students, studies of the hidden curriculum have since expanded to assessments of schools’ environments, assignments, non-classroom programming, and broader sets of distinctions and effects (see e.g., Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Justice and Meares Reference Justice and Meares2014; Nelsen Reference Nelsen2023; Ouer Reference Ouer2018; Willeck and Mendelberg Reference Willeck and Mendelberg2022). Across multiple educational contexts, the hidden curriculum can guide students’ understandings of themselves, their communities, and how they fit into the political system. Consistent with sociological work, this suggests that schools, among other institutions, play a key role in reifying social structures and systems of power, in part by training members of different groups into different modes of being, which contributes to the reproduction of social stratification (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977; Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1977; Foucault Reference Foucault and Sheridan1977). Much foundational research in education and stratification focused on students’ class backgrounds, demonstrating that lower social and economic class correlate with school environments that foster compliance (Anyon Reference Anyon1980; Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis1976; Nasaw Reference Nasaw1979). Building from literature in sociology and political science, including longstanding debates about the relationship between education, race, social mobility, and political equality (see e.g., Du Bois Reference Du Bois1903a; Washington Reference Washington1901) scholars have increased attention to race or combined analyses of race and class. This attention reflects the degree to which U.S. educational institutions are organized along racial lines, where reproduction of stratification maintains racialized, as well as classed, hierarchies, whether explicitly to maintain systems of racialized social control or (at least ostensibly) as a byproduct of other policy decisions (Bell Reference Bell1980; Collins Reference Collins2009; Kozol Reference Kozol2005; Simon Reference Simon2007). These studies point to correlations between racialized disparities in educational experience and students’ learning, outcomes, self-concept, sense of belonging, and understanding of institutions (see e.g., Collins Reference Collins2009; Hayward Reference Hayward2000; Kozol Reference Kozol2005; Spence Reference Spence2015). Across these debates, tension remains around the question of what, precisely, educational institutions are supposed to accomplish, and for whom.

In a world where the normative ideal of schools as democratic training grounds was realized, schools would teach and reflect democratic virtues and skills. They would encourage deliberation, treat students as stakeholders, give explanation and justification of disciplinary practices, encourage equity and fairness, place value on diversity, teach students to navigate difference, and foster empathy and fellow-feeling (Ben-Porath Reference Ben-Porath, Allen and Reich2013; Callan Reference Callan1997; Delpit Reference Delpit2006; Laden Reference Laden, Allen and Reich2013; Reich Reference Reich2002). They would also inculcate democratic norms and values and help students develop the skills involved in reason-giving, discourse, and critical thinking, which are essential for deliberation and collective reasoning (Benhabib Reference Benhabib and Benhabib1996; Chambers Reference Chambers, Andre Bächtiger, Dryzek and Warren2018; Dahl Reference Dahl1998; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996). Even when scholars disagree about how best to achieve this goal, there is general agreement that this vision requires equitable cultivation of democratic skill-building, investment, and efficacy (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1903b; Gutmann Reference Gutmann1999; Shelby Reference Shelby2016; Washington Reference Washington1901). Some schools and pedagogical approaches realize, or strive to realize, this vision, and research suggests that these approaches may encourage more equitable democratic participation (Bensman Reference Bensman2000; de Jesus Reference De Jesus, Rubin and Silva2003; Gay Reference Gay2010; Nelsen Reference Nelsen2021a; Niemi and Junn Reference Niemi and Junn2005; Zukin et al. Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andolina, Jenkins and Della Carpini2006).

Some schools realize a vision more in line with the idea that schools should train students to be productive workers, with an emphasis on compliance and routine, and that this is part of preparing students for a stratified social order (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1977; Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis1976; Foucault Reference Foucault and Sheridan1977; Katz Reference Katz1995; Nasaw Reference Nasaw1979). Indeed, in addition to teaching compliance through curriculum and routinization, some schools have integrated logics and practices of the criminal justice system. Whether in response to perceptions of danger, rhetoric around criminality, or expansive neoliberal logics, these schools tend to deploy hidden curricula that teach obedience, punishment, and uniformity. Some research suggests that these approaches decrease political participation (Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Justice and Meares Reference Justice and Meares2014; Simon Reference Simon2007; Spence Reference Spence2015).

Research suggests that differences in schools’ orientations and practices can impact students’ understanding of and orientation towards democracy. It can influence students’ degree of political knowledge and their sense of whether or not people like them belong in politics (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Greene, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Giersch, Kropf, and Stearns Reference Giersch, Kropf and Stearns2020; Levinson Reference Levinson2012; Nelsen Reference Nelsen2023). It can shape students’ likelihood of coming into contact with the criminal justice system, including in ways that might lead to formal disenfranchisement (Rosenbaum Reference Rosenbaum2018; Shollenberger Reference Shollenberger and Losen2015). It can inform students’ engagement with democratic institutions long after they leave school; policy feedback literature demonstrates that encounters with state agents that are experienced as arbitrary, humiliating, and authoritarian are a long-term deterrent to public engagement (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Mettler Reference Mettler2005; Weaver, Hacker, and Wildeman Reference Weaver, Hacker and Wildeman2014; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010). This effect extends to schools. As Sarah Bruch and Joe Soss have shown, a punitive, unfair, and arbitrary disciplinary environment leads to long-term decreases in voting and trust in government (Bruch and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018).

There are, then, clear connections between school environment and democratic outcomes. Which students are likely to end up in schools that encourage orientations towards or away from democratic participation? We turn to an original dataset to further explore the relationship between race and school environment.

Analyzing School Environments: Background

Charter Schools: Institutional Structure and Context

We construct our dataset from a national random sample of U.S. public charter schools collected at the end of the 2019-2020 academic year. We elect to focus on charter schools for several reasons.

One, charter schools are understood, and often see themselves, as representing state-of-the-art best practices. They are also seen as venues for market-driven innovation and the development of new pedagogical and classroom-management strategies, and many articulate an orientation towards democracy or, more broadly, “empowerment” (Campbell Reference Campbell2019; Seider Reference Seider2012). This makes charter schools ripe for study, both as a site for analysis and because there is institutional policy diffusion from charter to traditional public schools (Chubb and Moe Reference Chubb and Moe1990; Ravitch Reference Ravitch2010).

Two, charter schools are relatively new. The first state laws authorizing charter schools were passed in 1991, meaning that charter schools are, at the date of this publication, no more than 34 years old, and most are much younger, with almost 4,000 new charter schools opening between 2005 and 2020 (Ravitch Reference Ravitch2010; National Alliance for Public Charter Schools 2022). Once created, schools’ policy documents are more likely to be tweaked from year to year than rewritten, and schools develop in a path-dependent fashion, building on previous decisions. Charter schools’ relative youth means that their documents are more likely to reflect contemporary beliefs about how schools should be run for the student populations they serve.

Third, charter schools are more likely to operate as their own school districts and/or, even when they are part of a larger district, to maintain a separate web presence. This makes it more feasible to access and analyze key school documents that accurately reflect individual charter schools’ practices and can be correlated with their demographics.

Because our dataset is comprised of handbooks from a national random sample of charter schools, our results speak to language and conceptions of citizenship conveyed by school handbooks in these specific educational settings. There are some important differences between charter schools and traditional public schools, especially around school governance and curriculum. Traditional public schools are organized into school districts, overseen by a school board and superintendent, and often held to policies, procedures, and curricular choices determined by the district. On the other hand, public charter schools vary significantly in how they are governed and operated. Some small, stand-alone schools are operated by community members. Others, like KIPP or Uncommon Schools, are large organizations that manage dozens of schools across several states and serve tens of thousands of students. Many charter schools are between these extremes, consisting of a small network of 2-5 schools in a single city and/or operating semi-independently with a charter management organization or education management organization (David Reference David2018). Additionally, public charter schools often have more flexibility than traditional public schools in terms of curriculum and the length of the school day and year. There are also similarities between the two school types. Charter school students undergo state testing and must meet other state-level criteria, such as attendance thresholds, and may be closed if they underperform. Charter schools cannot charge tuition; cannot overtly discriminate based on protected class; cannot require set performance metrics, such as test scores or GPA, for admission; and are limited in their ability to remove enrolled students or refuse to re-enroll students for minor infractions or lack of academic progress (National Alliance for Public Charter Schools 2023; National Charter School Resource Center 2023). Additionally, many charter schools present themselves as local schools and even those that draw from larger catchments may seek to engender the kind of community and political support that makes schools important sites of politics (Nuamah and Ogorzalek Reference Nuamah and Ogorzalek2021; Nuamah Reference Nuamah2022). Still, an individual or organization petitioning to open a charter school can successfully argue for an alternative school schedule and educational approach, making them substantively and procedurally varied.

Charter schools’ relative autonomy has led to some controversy. Proponents argue that charter schools contribute to closing race and class gaps in educational and economic opportunity. Opponents argue that they perpetuate these gaps by selectively admitting students whose families are relatively well-resourced (“creaming” or “cropping”), employing less-credentialed teachers, undermining teachers’ unions, implementing harsh policies that contribute to the school-to-prison-pipeline, and diverting resources from underfunded traditional public education systems. However, proponents argue that charter schools are nimbler, more cutting-edge, and better able to serve students (Kozol Reference Kozol2005; Ravitch Reference Ravitch2010; Sanders, Stovall, and White Reference Sanders, Stovall and White2018).

Our focus on charter schools provides a window into contemporary ideologies and practices, as charter school enrollment in the United States has more than doubled in the last decade, accounting for 7.5% of total K-12 enrollments in December 2022 and a much higher percentage of enrollments in some localities, like Washington D.C., where 45% of students are enrolled in charter schools, and New Orleans, where the school system has converted almost entirely to charter schools (New Schools for New Orleans 2023; White Reference White2024). Studying charter schools also gives insight into what relatively independent school administrators have recently decided constitute best practices for demographically varied, school- or network-specific student bodies.

School Handbooks Provide Insight into “The Hidden Curriculum”

We use school handbooks because they give useful insight into the life of the school. Handbooks often contain information on the school’s mission or vision, daily routines, and disciplinary procedures. They can suggest information about the school community and its relationship to the local community and give a general sense for how the school views students and their needs (see e.g., Figure 1). In addition to providing a general sense for the school, we focus on handbooks for three main reasons.

Figure 1. Sample School Handbook Table of Contents.

First, handbooks reflect beliefs about best practices. They are typically authored by school or charter network leaders. They are sometimes also required to comply with city, state, and federal guidelines. Handbooks are bound by, and articulate, administrators’ understanding of how students should be governed and trained. They often tell teachers, students, and families what is expected from students and how the daily life of the school is organized. Students and teachers may follow the schedule laid out in the school handbook; students may be rewarded for good grades or behavior as the handbook notes; if a student breaks a rule, the school handbook may outline procedural and disciplinary schema. We suspect that students, teachers, and administrators sometimes deviate from the policies and practices laid out in handbooks. Even in these cases, however, school handbooks communicate what school leaders take to be the mission and correct routines of the school, which we believe offers important insight into the school.

Second, school handbooks give a sense of a school’s tone. Two handbooks may use very different language to discuss student learning. For instance, Royalton Montessori School’sFootnote 2 handbook celebrates student “joy” and “creativity” in the learning process, while KIPP East Marietta Academy emphasizes meeting instructional objectives through a standardized class structure. These handbooks suggest that Royalton students are more likely to encounter variety and spontaneity while learning, whereas KIPP students are more likely to experience routinization.

Third, the number of pages a school devotes to a particular subject in the handbook can communicate which subjects are considered important in that school. For example, Citizen’s Academy South Bronx’s handbook uses 26 of its 42 pages (62%) to discuss behavioral expectations, a behavior reward system, and the consequences students face if they fail to meet those expectations.Footnote 3 This tells us that behavioral regulation is important to the school.

Strictly speaking, we measure the language used in school handbooks, not in the classrooms and halls of school buildings themselves. We recognize that it is unlikely that school handbooks capture the full, true school environment for each individual school in our sample. However, because handbooks lay plain the school mission, vision, values, routines, and disciplinary procedures, they communicate schools’ goals and suggest what life at a school is intended to look and feel like. Thus, taken on the whole, we believe that the school handbooks provide useful, if partial, insight into school environments.

Data, Methods, and Initial Results

Data and Methods Part 1: Word Frequency Analysis

Analyzing school environments often relies on necessarily low-N qualitative methods such as school visits and interviews. These methods provide tremendous insight but are so time-intensive as to preclude large-scale analysis, and therefore give a limited picture of nationwide trends. Departing from these methods, we build an original dataset of the text of school handbooks from a nationally representative sample of public charter schools in the United States.

To construct the initial dataset, we drew a random sample of schools from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Public School Directory for the 2019-2020 academic year. Our initial random sample consisted of 1,040 public schools. From that sample, we excluded 238 schools for one of the following reasons: they were not primarily educational institutions (hospitals, domestic violence shelters, rehabilitation facilities); they did not have a physical campus (cyber-campus, homeschooling); or they exclusively served populations that are already differently oriented toward the democratic process (criminal justice centers, military schools). We also excluded schools without publicly available handbooks, noting no significant pattern in the availability or non-availability of these documents. After these exclusions, our sample consisted of 802 public charter schools or 10.6% of all charter schools from 2019-2020.Footnote 4

In May and June 2020, we downloaded handbooks from each of the 802 schools. We used the R environment to load the text of the school handbooks as unstructured text data. We broke the data by page (n = 41,977) to make it easier to view in parts. We created a corpus from our dataset whereby we separate the data into individual words and “cleaned” the data by removing common English words (such as “the,” “on” and “to”), URLs, and punctuation, and stemmed the words to their root. We then merged this handbook text data with the school demographic information for the 802 public charter schools.

To obtain normatively useful results, we grouped schools according to the demographic composition of the student body: schools that have a simple majority of White or non-White students (50/50) or that have a larger majority of White or non-White Students (70/30).Footnote 5 We are interested in understanding which topics schools consider to be most salient and how schools communicate those topics. As an initial measure of salience and a starting point for normative theorizing, we drew a random sample of all handbook pages (n = 1,000). We estimated an LDA topic model, algorithmically sorting the pages by like topics (k = 25). We generated a list of unique terms and representative pages for each topic. Then, we computationally generated word frequency counts for each grouping of schools. As a validity check, we repeated the topic models on all the handbook text by our demographics of interest to ensure that we were interpreting the context of the terms appropriately.

Results Part 1: Word Frequency Analysis

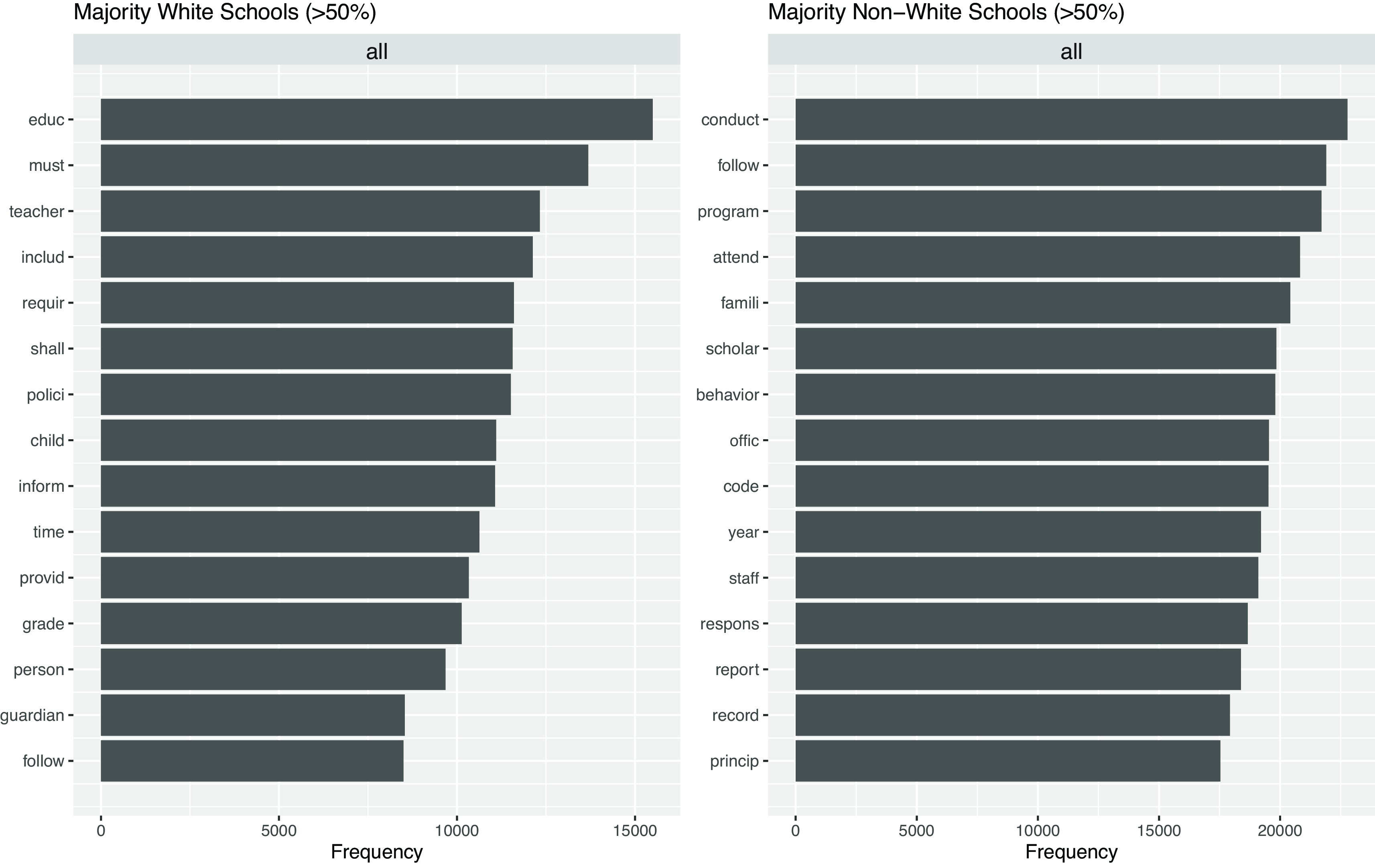

Initial results reveal that charter school handbooks may use different terminology based on the racial makeup of the student body (see Appendix B, Tables B.1 and B.2). In charter schools where a majority of students (50% or more) are White, the most frequently appearing terms include those one might expect from a school, such as “educ*” and “grade.” These are not among the most frequently appearing terms in majority non-White schools; instead, we see terms such as “conduct,” “behavior,” and “princip,*” the stem for the term “principal” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Top Unique Features in School Handbooks by Race.

We find similar patterns in more segregated charter schools. Top unique terms in schools with 70% or more non-White students include the terms “conduct,” “behavior,” and “suspens*,” the stem for “suspension,” (see Appendix B, Table B.2 and Figure B.1). Our topic models confirm that these terms are disciplinary and that disciplinary topics make up a greater proportion of topics in non-White schools (see Appendix B, Figures B.2 and B.3).

Data and Methods Part 2: Communication of Citizenship

We are interested in how schools conceive of and communicate citizenship. To this end, we construct a second dataset. We used the grepl function to separate out school handbook pages that use word derivations of citizenship or civics (n = 1,412).Footnote 6 Because the number of observations was relatively small, we elected to read and manually code these pages to give us a ground truth measure of the concepts. To do this, we first exported only the handbook pages with the unique school ID for coding, ensuring that no demographic information about the school influenced our interpretation of the text. Next, we isolated a random sample of 100 of the handbook pages, using them to iteratively develop our codebook (see Appendix C). Once the codebook was developed, we coded each mention of “citizenship” or “civic” according to the following categories: generic usage, obedience, responsibility, doing good, self-actualization, critical thinking, patriotism, productive, classical, caring, global, and knowledgeable. We excluded observations where the terms were used in a legal sense, when they did not refer to students, or when they referred to students’ use of electronic devices (“digital citizenship”). After verifying the integrity of the coding, we imported the coded data back into R and merged it with school demographic information. The resulting dataset consisted of 895 pages where citizenship or civics is discussed in a normatively meaningful way. We added a race variable in the same manner as we did in the previous dataset. We used simple calculations to determine what percentage of the time citizenship is discussed in each of the normative iterations we identified in our codebook. Like with word frequency counts, this analysis is largely exploratory, undertaken to point us toward discursive patterns and areas of the handbook texts for normative theorizing.

Results Part 2: Normative use of Citizenship and Civic

Out of 41,977 pages of school handbooks, 1,412 use the terms citizen or civic. Of these, 895 pages discuss these terms normatively and with respect to students. Those observations come from the handbooks of 560 different schools, out of 802 in our sample (70%). There is no significant demographic difference between schools that do or do not discuss these terms in their handbooks.

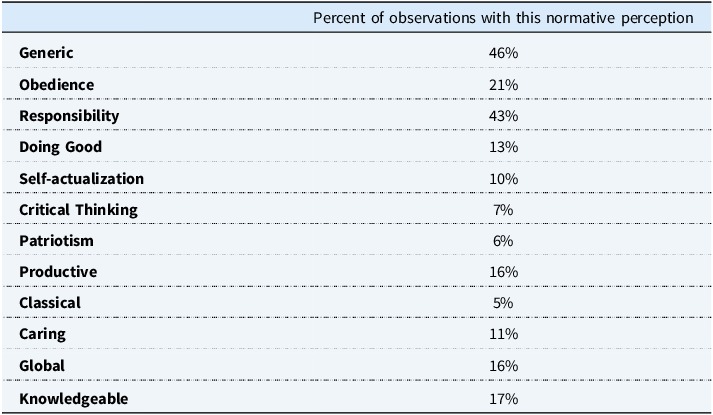

When charter school handbooks discuss citizenship or civics explicitly, we find that some normative conceptions occur more frequently regardless of demographics (see Table 1). Across all schools, these terms are most often used generically or related to the idea of “responsibility.”

Table 1. Normative Conceptions of Citizenship

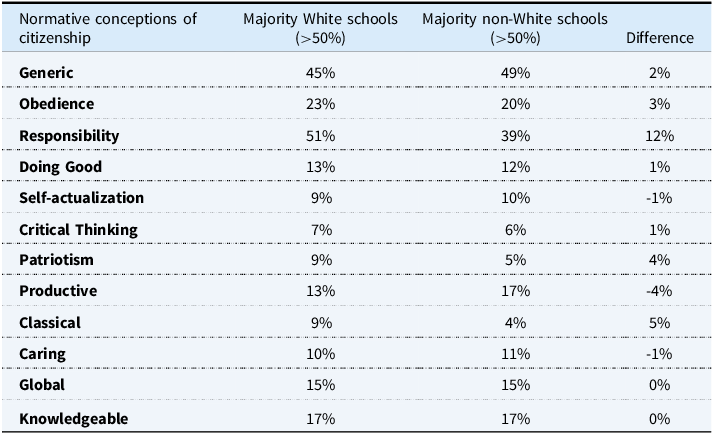

The frequency of some of these normative conceptions differs along racial lines. For example, when we examine racial differences based on a simple majority (more than 50% White or non-White students), we note differences in how often school handbooks conceptualize citizenship in terms of patriotism, classical education, responsibility, and productivity (see Table 2).Footnote 7 When we examine charter schools where 70% or more students are White or non-White, we continue to see differences in how often schools conceptualize citizenship as responsibility and classical education (see Appendix D, Table D.2).

Table 2. Raw Data: Normative Conceptions of Citizen* and Civic* By Race (>50%)

The Dynamics of Race and Class

To better isolate the relationship between race, language in charter school handbooks, and conceptions of citizenship, we attempt to control for class. It is worth noting that this attempt is complicated by the available data, which tells us what percentage of students at a given charter school qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, for which students’ families must be within 130% (for free lunch) or 185% (for reduced-price lunch) of the federal poverty line. (Food and Nutrition Service 2022) While extant theory suggests that class can be more finely stratified within educational institutions (Anyon Reference Anyon1980; Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu, Passeron and Nice1977), available data do not give us insight into income or wealth of other families. Additionally, very few schools in our dataset (n = 9) have both a majority of White students and a majority of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, making it challenging to compare racial differences in schools where most students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Despite these challenges, we conduct comparisons of different groups while holding either race or class constant to better understand if and when class plays a role in our findings.

First, we isolate charter schools where a majority of students are non-White or White (70% or greater). We then subset these schools by the percentage of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. In a word frequency analysis, we find no substantive differences in the type of language used by majority non-White charter school handbooks, regardless of the percentage of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. For example, the terms “conduct” and “behavior” remain top terms in majority non-White school handbooks, regardless of the percentage of students who qualify (see Appendix E, Figure E.1). Similarly, we do not find any major differences in the type of terminology used by majority White charter school handbooks, regardless of the percentage of students who qualify (see Appendix E, Figure E.2). Conversely, when we isolate only schools where 30% or less of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, we do see differences in the terminology based on the racial makeup of the student body. In majority non-White charter school handbooks, “behavior,” “report,” “suspens*, and “conduct” remain top terms. These terms are not frequently found in majority White charter school handbooks with 30% or fewer of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch (see Appendix E, Figure E.3). This leads us to determine that race, rather than class, is most likely the driving factor in the word frequency patterns we see in school handbooks.

We repeat these class analyses for our variables of interest (classical education, responsibility, and productivity) when examining how charter schools normatively conceive of citizenship in their handbooks. When we hold race constant, we find no differences in how often majority non-White or majority White charter schools conceive of citizenship in their handbooks, regardless of the number of students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch (see Appendix E, Figure E.4). When we isolate charter schools where 70% or more of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, we continue to find racial differences in how often schools conceive of citizenship as responsibility and productivity. When we isolate charter schools where 30% or less of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, we find that conflation of citizenship with classical education remains different depending upon the racial demographics of the school (see Appendix E, Figure E.5).

Racial Differentiation in Historicizing Democracy

Across all handbooks, associations of citizenship with classical democracy were infrequent, appearing in 5% of observations (see Table 1). However, in our sample, citizenship is associated with classical values and education on 9% of handbook pages that mention “civics” or “citizenship” at majority White charter schools, but only 4% of pages at majority non-White charter schools (see Table 2).

This is noteworthy in part because these observations included some of the most explicit discussions of democratic participation in the classic Greco-Roman context. For instance, Galatian Classical Academy in Texas, which is 72% White, tells students that:

There was a time when books, art, and contemplation were the tools great men and women used to be good and productive citizens. These tools formed their world view and paved a way toward making them the great individuals we know today. Not so long ago all educated men and women would have been familiar with the greatest works of western civilization. Familiar names like Jefferson, Adams, Washington, Lincoln, Marshall, and Douglass, just to name a few, would have read Homer, Aristotle, Plato, Alcibiades, and other great works once commonplace in American schools. Galatian students, like the great men and women before them, read great books, contemplate great ideas, and do great things, always keeping in mind the adage that to shine bright in this world one must first illuminate oneself by careful study and hard work. Galatian Classical Academy students are immersed in a culture of learning in which virtue, civility and good manners challenge them to be better humans and citizens.

Discussions like this go beyond passing mentions of citizenship. They foreground a specific vision of democratic life as central to the purpose of the school and the health of the polis. They present democracy as part of a distinctly Western tradition, to the exclusion of more expansive understandings of what democratic participation is or could be (Junn Reference Junn2004). Classical figures like Plato and Aristotle are presented as founding democratic champions and part of an elite, great, influential genealogy dating back millennia and worthy of historicization. Students can join this lineage by knowing about, behaving like, and learning reverence for these figures. The tradition is made explicit to them, and they can be part of it.

Conversely, the classical tradition appears less frequently in the handbooks of schools with a majority of non-White students. When historical figures appear, they are not usually part of a “great” tradition and are more frequently presented as either apolitical or engaging in protest because institutions exclude and are non-responsive to their groups. Such depictions may underscore minoritized students’ sense that people like them are external to and do not belong within formal political institutions and/or that they are not politically efficacious (Nelsen Reference Nelsen2021b). See, for instance, the mission statement of Cesar Chavez Language Academy in California, which is 89% non-White:

The mission of Cesar Chavez Language Academy (CCLA) is to create a family and community-centered environment that promotes a rigorous academic environment which creates bilingual, biliterate and multicultural quality education for all students. This environment fosters creative, honest and kind citizens of the community and the world….

∼Preservation of one’s own culture does not require contempt or disrespect for other cultures.∼ Cesar Chavez

It is worth noting that many schools with a majority of non-White students intentionally center historical figures from minoritized groups as part of a culturally responsive pedagogy that seeks to make school environments and curricula more relevant to students’ identities and communities (see e.g., Gay Reference Gay2010). CCLA seems to take this approach to at least some degree, with its motto of “Bilingual | Biliterate | Bicultural | By Choice,” Quetzal mascot, and principal’s statement that “it is important for our children to be bilingual, as well as have a strong cultural and ethnic identity.” A figure like Cesar Chavez fits well with this model, and, given Chavez’s work as an efficacious and influential political organizer, he could suggest the importance of democratic engagement and be presented as part of a lasting, important tradition of democratic political activists. Yet the above quote is the only reference in CCLA’s handbook to Chavez as a historical figure. It may familiarize students with Chavez’s name, but his activism and place within a pantheon of U.S. political organizers is elided; it is not part of a lineage that students might join. Chavez is associated with the creation of “creative, honest and kind citizens” rather than, as is the case with the presentation of democratic lineage at Galatian Classical Academy, figures who “contemplate great ideas, and do great things.”

Given the principles of culturally responsive pedagogy, we are not surprised that charter schools with a majority of non-White students do not align themselves with the classical tradition as frequently as do majority White charter schools. Still, we find the differences in the characterization of historical figures noteworthy. Handbooks in schools with a majority of non-White students rarely communicate to students that they are part of, and can join, a great and influential democratic lineage. The inculcation of democratic norms and traditions can be considered an important part of preparation for and maintenance of democratic participation on its own (Dahl Reference Dahl1998). Yet, notably, it occurs more frequently, and on different terms, in majority White schools.

Racial Differentiation in Discussions of Responsibility

Responsibility appears more frequently in the handbooks of majority White charter schools than it does in the handbooks of majority non-White charter schools (see Table 2 and Appendix D, Tables D.1 and D.2). Qualitative analysis of school handbook pages that include “citizen” or “civic” in reference to responsibility indicates racial differentiation in how responsibility is treated.

In majority White charter schools, responsibility is often depicted as form of moral and intellectual development and worth, and/or as a way of actively contributing to the larger community. For instance, at Tomorrow’s Future Charter Academy in North Carolina, which is 86.7% White:

Our students will understand that a good citizen rules and is ruled; is independent, yet simultaneously in relation to others; and, is grounded in an honest search for knowable, universal truth, goodness, and beauty. To foster this model of citizenship, we will maintain our delivery of a robust, liberal arts curriculum, deepen our implementation of classical education, and continue our principle-based discipline grounded in love for the individual and a respect for the corporate good, as well as a belief in redemption and growth. Through these means, we will increase our attention to developing the following characteristics of citizenship in our students: 1) an awareness of themselves as members of a community, from local to national to global; 2) a devotion to intellectual and moral integrity, including an ability to fashion credible ideas and to argue logically; 3) an appreciation for the rule of law; and 4) an understanding of American constitutional democracy.

At Building Blocks Academy in Utah, which is 70.5% White, students read that:

To thrive in work, citizenship, and personal growth, children must be taught the values of a democratic society. These values include: Respect for others—their property and rights; Responsibility for actions, honesty and social justice; Resourcefulness—being ready to learn, to serve, and to share.

In both instances, responsible citizenship is closely associated with learning, action, integrity, and belonging to and within a larger whole. In these contexts, “responsibility” implies political efficacy and something akin to self-actualization; students are expected to develop an intellectually and morally grounded sense of the good and apply it to the world around them. Here, “responsibility” is active and powerful. Its depictions comport with historical and contemporary theoretical accounts of democratic responsibility as requiring moral autonomy and an ability and willingness to make and advocate for political judgment (Chambers Reference Chambers, Andre Bächtiger, Dryzek and Warren2018; Dahl Reference Dahl1998).

In majority non-White charter schools, responsibility was often associated with rule-following and discipline. For instance, at Champion High School in Texas, which is 99.1% non-White, responsibility is presented in the handbook as equivalent to obedience to laws and rules:

As citizens, students are entitled to our society’s benefits; but as citizens, they are also subject to its national, state, and local laws and rules governing various aspects of their conduct. Not all laws are easy to follow, nor need one necessarily agree with each and every law or rule. Often a law or a rule seems unjust or inappropriate, but the law or rule must be obeyed. In the same manner, students live and function in a second community as well—namely, the school community. Education confers its own benefits, but it, too, requires acceptance of individual responsibilities.

And at Norton Shores Academy West in Michigan, which is 98.3% non-White:

Punctuality to school and to class is very important. With promptness, a student demonstrates self-discipline and responsibility. Self-discipline in this area is not only important for proper academic achievement, but it is essential for the development of good habits, which are characteristic of success and good citizenship

In these instances, responsible citizenship is about anticipating, internalizing, and obeying rules. Students’ own judgments are irrelevant; they must abide by the rules even if they “seem unjust or inappropriate.” The rules they must abide involve a degree of micromanagement that is largely absent from the discussions in majority White charter schools’ handbooks. Here, counter to much democratic theory, “responsibility” is about showing up on time, exhibiting self-discipline as defined by others, and suspending autonomous judgment in favor of obedience.

The same pattern appears even when demographically different charter schools employ the same framework. The widely recognized “Character Counts!” program advocates for instruction in “Six Pillars of Character” which “were identified by a nonpartisan, secular group of youth development experts in 1992 as core ethical values that transcend cultural, religious, and socioeconomic differences” (Josephson Reference Josephson2022; Staff 2022). Yet their application takes different forms in demographically different schools. At Bennett Circle Middle School in North Carolina, which is 80% White, students read that:

The Character Education Program at BCS is dedicated to developing young people of good character who become responsible and caring citizens. Following are the six Character Pillars of our program:

CHARACTER PILLARS

Trustworthiness

Be honest • Don’t deceive, cheat, or steal • Be reliable—Do what you say you’ll do • Have the courage to do the right thing • Build a good reputation • Be loyal—stand by your family, friends, and country

Respect

Treat others with respect; follow the Golden Rule • Be tolerant of differences • Use good manners, not bad language • Be considerate of the feelings of others • Don’t threaten, hit or hurt anyone • Deal peacefully with anger, insults, and disagreements

Responsibility

Do what you are supposed to do • Persevere (keep on trying!) • Always do your best • Use self-control • Be self-disciplined • Think before you act—consider the consequences • Be accountable for your choices

Fairness

Play by the rules • Take turns and share • Be open-minded; listen to others • Don’t take advantage of others • Don’t blame others carelessly

Caring

Be kind • Be compassionate and show you care • Express gratitude • Forgive others • Help people in need

Citizenship

Do your share to make your school and community better • Cooperate • Get involved in community affairs • Stay informed; vote • Be a good neighbor • Obey laws and rules • Respect authority • Protect the environment

In this formulation, responsibility is associated with effort, thoughtfulness, and self-discipline, and surrounded by an articulation of values that underscores self-determination and capacity for deliberation and forethought. The responsible individual makes judgments about the world around her, is guided by an internal compass, and is capable of efficacious political participation.

On the other hand, at Envision Mesa East in Arizona, which is 97.7% non-White:

Students will make good choices by displaying the Six Pillars of Character: trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, fairness, caring, and citizenship.

If students fail to make good choices the teacher (or staff member) may enforce the following consequences:

-

• Warning

-

• Time out

-

• Loss of privileges/recess

-

• Parent phone call

-

• Detention slip

-

• Office referral

The Six Pillars are not defined here or elsewhere in Envision Mesa East’s handbook; there is no clear conceptualization of responsibility, citizenship, or any of the other associated values. Responsibility is something vague and undefined, which students must do to avoid punishment. Ideas of efficacy, action, judgment, deliberation, and self-determination are absent from the handbook’s discussion. Where predominantly White Bennett Circle Middle School articulates values, predominantly non-White Envision Mesa East articulates consequences.

More generally, predominantly White charter schools’ handbooks tend to construct “responsibility” as something noble and community-minded. Students at these schools are encouraged to see responsibility as a matter of integrity, discernment, self-awareness, justice, and political activity. Meanwhile, students at majority non-White charter schools are encouraged to see responsibility as a matter of discipline, obedience, and punishment. These usages are both consistent with analyses of schools’ use of “responsibility” to transmit and underscore a conservative and individualistic ethos which encourages a focus on “personal responsibility” rather than systemic and social critique (Westheimer and Kahne Reference Westheimer and Kahne2002). However, our analyses suggest that students’ racial positions may shape what they learn that they are responsible for, and the degree to which responsibility involves the sort of efficacy, action, and moral autonomy that historians and theorists of democracy see as essential to democratic participation.

Racial Differentiation in Discussions of Productivity

Majority non-White charter schools were more likely to associate citizenship with productivity in their handbooks (see Appendix D, Tables D.1 and D.2). Once again, qualitative analysis underscores racial differentiation in how charter schools treat productivity.

In majority White charter schools’ handbooks, mentions of productivity in association with citizenship emphasize students’ capacities and potential. For instance, at The Redwood School in Colorado, which is 83% White, students read that:

Authentic assessment does not encourage rote learning and passive test-taking. Instead, it focuses on students’ analytical skills; ability to integrate what they learn; creativity; ability to work collaboratively; and written and oral expression skills. It values the learning process as much as the finished product. Through authentic learning experiences and assessment of that learning we aim to develop productive citizens; to develop learners capable of performing meaningful tasks in the real world; and the ability to replicate real world challenges.

And at Lenoir Charter School in North Carolina, which is 72% White:

At their foundation, teachers, parents and students at Lenoir Charter School will have the shared academic philosophy that all children can learn, become self-motivated life-long learners, function as responsible citizens, and realize their potential as productive members of the local and global societies and the 21st century workforce.

Both discussions emphasize students’ multi-faceted skills and capabilities. Productivity involves analysis, creativity, collaboration, expression, and self-motivation. It is an expression of students’ selves—their viewpoints, experiences, and abilities—and something that can be cultivated by every student. While work is mentioned, wage labor is de-emphasized as part of a larger vision of life that also includes community, meaning, the pursuit of “authentic” interests and skills, and intrinsic ability and motivation. Productivity is accessible to all, one part of a life well-lived, and it is not associated with or reliant on punitive systems.

Conversely, in majority non-White charter schools, handbooks portray productivity as closely tied to disciplinary apparatus. For instance, at New Horizons in California, which is 100% non-White, productivity and citizenship appear in a sample contract for student truancy:

Student Contract: Truancy

I_______________________________ fully understand I must follow all school rules and policies. This also includes all classroom rules and procedures. This contract does not exclude me from the school rules that all students must follow.

I ________________________________ am entering into this contract because I:

______ I am a “truant” _____ I have excessive tardies of 30 minutes or more

______ I have irregular “tardies” (I oftentimes come to school after 8:10 a.m.; These are excessive tardies, but less than 30 minutes.)

______ The school record shows I have ______ tardies and ______absences

I cannot go through life being late and absent constantly, because I will never be a successful “life-long learner” and it will keep me from having a very good job, doing well in school and being a productive citizen.

And also, I want to grow up and be a _______________ ___________________and I want to own my own home ___ yes ___ no.

And at Jose Antonio Navarro Preparatory STEM Academy in Texas, which is 100% non-White, the idea of productive citizenship appears in the school’s dress code:

Learning for life includes developing a sense of personal pride and dignity by dressing and grooming in a manner that encourages self-discipline and loyalty to things that are greater than oneself—such as the school, the state, and the country. Learning about and developing personal pride and dignity are important characteristics to help students become valuable and contributing citizens.

Neither handbook passage contains references to authenticity, analysis, universal capabilities, or intrinsic skills or motivation. Productivity, here, is closely tied to following the rules—dressing properly and showing up on time so that one can have dignity, have a job, and own a home. These constructions also imply a threat: if students do not dress and groom themselves properly and do not show up on time, they will not experience dignity, will not have jobs, and will not own homes. These stakes, both material and psychological, are absent from the discussions at majority White Redwood School and Lenoir Charter School.

The difference in these discussions may suggest that students are being prepared for different types of productivity. At New Horizons and Navarro Preparatory STEM Academy, students learn to be punctual and wear a uniform—skills that are typical of low-wage service and industrial work, in contrast with the analytical and creative skills typical of professional, white-collar work. While Navarro Preparatory STEM Academy makes reference to “things that are greater than oneself” and to the value of pride and dignity, these values remain rooted in obedience, since they can be cultivated specifically by adhering to the school’s dress code. Productivity is not an expression of self; it is learning and following the rules in order to obtain economic and psychological rewards.

More generally, predominantly White charter schools’ handbooks tend to construct “productivity” as an extension of every student’s innate gifts and often take for granted that students will become productive citizens. Where they have differences in skills and aptitudes, these are positive and can be understood as part of the sort of collective democratic reason that, theorists argue, can be buoyed by cognitive diversity (Landemore Reference Landemore2012; Young Reference Young, Bohman and Rehg1997). These students read descriptions of productivity that suggest a bright future: by virtue of who they are and what they are capable of, they will become autonomous, motivated, creative, capable adults who contribute meaningfully to the world around them and whose material security seems to be guaranteed. Students at majority non-White charter schools might discern a considerably bleaker picture, involving economic precarity, low-wage labor, and obedience.

Conclusion

Schools are a key site of political socialization. Debates persist about whether and when socialization encourages engagement or obedience, autonomy, or compliance. Our analysis suggests that both models are alive and well in U.S. charter schools—but that they are, in effect, largely segregated by race.

In general, handbooks at majority White charter schools were more likely to communicate that democratic citizenship is part of a longstanding classical Western tradition which involves making and acting upon judgments about responsible behavior and which students can join. They were also more likely to present visions of citizenship that comport with the democratic tradition, wherein democracy benefits from citizens who are able to engage in moral autonomy, judgment, mutual justification, critical thinking, deliberation, and knowledge of democratic traditions.

Conversely, handbooks at majority non-White charter schools were more likely to present an authoritarian vision of citizenship, including an emphasis on obedience, discipline, and threat of punishment. They were less likely to situate students in an efficacious political tradition. This understanding of citizenship does not comport with historical or contemporary democratic traditions. Rather, it seems more akin to subjecthood, emphasizing subordination to authority and eliding deliberation, participation, and moral autonomy.

We contend that these disparities in school handbooks likely point to real and meaningful differences in these school environments, including in how students understand their relationship to democratic citizenship and civic engagement. This is consistent with a key commonality across the literature: the well-supported understanding that schooling has formative effects on students’ future understanding of the world, their place in the world, and their relationship to politics and political participation.

Still, there are several limitations to this study that could be addressed with further research.

First, our results speak most directly to the racial differentiation in language and conceptions of citizenship and civics in charter school handbooks collected in 2020. We speculate that handbooks offer us a useful picture of school environments, but one that is necessarily incomplete. Future ethnographic research comparing daily life at the school with the policies and procedures outlined in the handbook could offer additional support for our decision to examine school handbooks as partially representative of school environments. Future studies should also explore whether school handbook language changes over time, particularly in response to political events.

Second, given the differences between charter schools and traditional public schools, the generalizability of this study is limited to U.S. public charter schools. Given that the school types have several differences, but also several similarities, conducting a similar study of traditional public schools is a productive area for future research.

Third, analyses of school handbooks in either U.S. public charter schools or traditional public schools could further subset on school demographics. Future studies could explore whether differential linguistic patterns emerge between schools with majority Hispanic, Black, Asian, Indigenous, and White student populations. Additionally, researchers may consider whether a school’s designation as rural, suburban, or urban is correlated with language or conceptions of citizenship in its handbook.

Finally, we understand a limitation of our analysis to be the lack of availability of school-specific data for class beyond the very rough measure of percentage of students qualifying for free or reduced-priced lunch. We see an exploration of potential differences in school environments by class as an area ripe for future analysis.

We take these to be important areas for future research in part because of the potential normative implications of these findings. If education, including the “hidden curriculum” suggested by school handbooks, is a key factor in shaping students’ orientation towards the world, including the political world, we see cause for concern in these racial disparities: about citizens who may be taught to cultivate meaningfully different understandings of and orientations towards democracy, about disparities between those who see democratic institutions as venues for action or authorities who should be obeyed, and about how these different understandings—and potentially different rates of or approaches to participation—could continue to perpetuate systems of racial oppression.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.28

Acknowledgements

We thank Kate Destler, Daniel Ferries, Bob Maranto, Diana Owen, Jeff Spinner-Halev, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this project. We are grateful to Alexandra Siegel, Damon Roberts, Kathryn Schauer, and the CU Boulder Center for Research Data & Digital Scholarship for their data-related support and expertise.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific financial support.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.