Introduction

The welfare state is one of the most significant policy achievements that modern democracies have produced. It consumes a large chunk of most developed economies and directly affects millions of people’s living standards. The most influential theory to explain crossnational and overtime variation in welfare states views them as the outcome of a struggle among political coalitions with varying degrees of power resources. Thus, the size and shape of welfare states are understood largely as a product of partisan and interest group conflict (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Ragin and Stephens1993; Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001; Korpi, Reference Korpi1983; Stephens, Reference Stephens1979).

While extremely useful in explaining broad system-level variation, this approach has necessarily neglected variation in partisan conflict across different domains within a single country or welfare regime. Yet, looking at real-world outcomes, it becomes clear that individual social programs within a country or regime type often take radically divergent trajectories – even under the same political constellation. The Thatcher governments, for instance, slashed unemployment and housing benefits, but reforms to the National Health Service were much more modest in scope (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996). The Swiss People’s Party has successfully pushed other right-wing parties to retrench unemployment insurance but found it impossible to agree to pension cuts (Afonso and Papadopoulos, Reference Afonso and Papadopoulos2015). By contrast, the center-right cabinets governing Austria between 2000 and 2007 passed significant pension cuts but substantially expanded childcare benefits (Rathgeb, Reference Rathgebforthcoming). What is more, much of the growing literature on welfare chauvinism is focussed on the fact that political actors promote generous policies for some groups (natives) and retrenchment for others (nonnatives) (Careja et al., Reference Careja, Elmelund-Præstekær, Baggesen Klitgaard and Larsen2016; Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2018; Otjes, Reference Otjes2019; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016). Even in their replication of Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) regime classification, Scruggs and Allan (Reference Scruggs and Allan2006: 69) conclude that “scores among social-insurance programmes are so weakly intercorrelated, we might just as well talk about the individual welfare programmes, not regimes”.

One possible conclusion from this heterogeneous picture would be to argue that the partisan hypothesis only goes so far in explaining welfare state outcomes – all variation within countries during the same time period is therefore beyond its explanatory reach. However, this paper makes a different case. It conjectures that there are systematic – and hitherto underresearched – differences in the partisan conflict that can explain divergent trajectories in social policy (Bandau and Ahrens, Reference Bandau and Ahrens2020: 40).

Theoretically, this paper thus contributes to a more recent literature in comparative social policy that seeks to explain why we should expect partisan differences to vary across policy areas. Studies in this field have, for instance, theorised that partisan conflict should be more important for employment protection than for active and passive labour market policy (Rueda, 2005; Reference Rueda2007), more prevalent for employment-related than for life course-related policies (Jensen, Reference Jensen2012) and more intense on institutional than on policy reforms (Klitgaard et al., Reference Klitgaard, Schumacher and Soentken2015).

Like these studies, this paper views parties as both policy-oriented and office-oriented (Müller and Strøm, Reference Müller and Strøm1999; Strøm, Reference Strøm1990). In the pursuit of their preferred policy outcomes, they are thus constrained by voter preferences. This constraint will be especially severe for the most popular welfare state programs. Based on these arguments, it is hypothesised that partisan conflict should be more intense (1) for revenue-side issues than for expenditure-side issues (e.g. social insurance contributions versus social insurance benefits), (2) for programs targeting groups viewed as less deserving and (3) for more redistributive programs (e.g. means-tested benefits).

These hypotheses are tested on extremely fine-grained policy data produced by the Austrian National Election Study (Autnes) from 65 election manifestos issued by seven parties across 15 parliamentary elections in Austria between 1970 and 2017. This data source yields 18,219 manifesto statements coded into 111 different social policy issues that can be categorised according to the three hypotheses: as referring to 1) revenue-side or expenditure-side issues, 2) groups viewed as high-deserving or low-deserving and 3) earnings-related, universal or means-tested benefits. Examining the effects of these issue characteristics on partisan conflict would be impossible with more conventional data on party positions. This paper thus provides a uniquely granular account of party appeals on welfare state issues.

The analysis uses binary logistic models with random effects at the manifesto level to predict the occurrence of proretrenchment statements as a function of party ideology (left versus right) and its interaction with the three-issue characteristics outlined above. The results show that the revenue–expenditure distinction and deservingness perceptions strongly structure the intensity of partisan conflict over social policy issues, whereas the degree of redistribution has no discernible impact. These findings deepen our understanding of party competition over the welfare state and thus contribute to understanding the heterogeneous effects of partisanship on social policies.

Theoretical framework

Arguing the unpopular: making the case for retrenchment

A core tenet of the welfare state literature in the “age of austerity” is the observation that, overall, the welfare state is very popular with voters, especially those programs that benefit large parts of the population (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996). Through its massive expansion during the early postwar decades, the welfare state has generated powerful constituencies that command significant electoral weight and have the capacity to organise politically (e.g. pensioners, families, health, and care workers). As a result, advocating for the retrenchment of social programs can be an electorally risky proposition – even though it is not at all certain that government parties will be punished for cutting social programs (Armingeon and Giger, Reference Armingeon and Giger2008; Giger and Nelson, Reference Giger and Nelson2011; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Vis and van Kersbergen2013).

Still, parties and politicians that are ideologically committed to retrenching benefits have strong incentives to “minimise the political costs involved” (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996: 145). One strategy is to build large proreform coalitions in order to share the electoral costs (Hering, Reference Hering2008). Another approach is to package retrenchment in ways that are less visible to voters, for instance, tweaking indexation rules rather than cutting nominal benefit levels (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Arndt, Lee and Wenzelburger2018). Also, cuts in one area may be compensated by more generous policies in another domain (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2000: 154). Yet, while potentially beneficial in terms of policymaking, these strategies are less useful in the competitive environment of election campaigns that discourage crossparty cooperation, reward policy visibility and generally do not lend themselves to explaining complex policy trade-offs.

Therefore, electoral competition may force parties to adopt their (stated) policy preferences by moving closer to the median voter. As the “New Politics” approach argues (Pierson, 1996; Reference Pierson2001), the expansion of the welfare state has shifted the political equilibrium to the left, effectively turning its most popular policies into valence issues on which there is only one electorally viable position (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge, Farlie, Daalder and Mair1983b; Stokes, Reference Stokes1963). After all, the median voter in most modern democracies is almost certainly a (future) beneficiary of multiple welfare state programs. If public opinion on a social policy issue converges to near-unanimous support, the policy space within which parties can plausibly compete on this issue shrinks. Yet, because public opinion converges toward the left, this compression of the competitive policy space happens in an asymmetric fashion. The more popular a policy, the greater the pressure for parties on the right to move leftward. By contrast, there is no similarly strong incentive for leftist parties to shift their position to the right.

The empirical implication of this argument is that the pressure on right-wing parties to take more leftist positions will be greater for policies with broader support. As a result, partisan differences should be a function of how popular a specific welfare state program is. This argument follows the logic of the saliency theory of party competition (Budge, Reference Budge2015; Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge, Farlie, Daalder and Mair1983b; Budge et al., Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001; Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser-Jedenastik, Müller and Winkler2014). Saliency theory views party competition as an exercise in selective emphasis rather than as a matter of parties taking contrasting positions across the most important issues. Voters are assumed to have one preferred course of action on most issues. Parties whose position on an issue is in line with that preference will strongly emphasise that issue, whereas parties with positions that a majority of the electorate rejects will avoid it.

The most straightforward implication of this argument would be that left-wing parties (whose position on welfare state issues is closer to the median voter) should talk more about social policy than right-wing parties. However, given the overall importance of the welfare state as a policy issue, it may be electorally unfeasible to pursue a strategy of complete issue avoidance.Footnote 1 Hence, parties of the right have an incentive to emphasise those welfare state issues on which a more restrictive position is electorally less problematic. Partisan conflict – that is, the difference between left-wing and right-wing parties – should thus become more visible in those policy areas. Based on this reasoning, the following sections argue that partisan conflict should be (1) more intense on “revenue issues” (e.g. social insurance contributions) than on “expenditure issues” (e.g. social insurance benefits), (2) more intense for programs whose recipients are perceived as less deserving (e.g. immigrants) and (3) more intense for benefits that produce higher levels of redistribution (e.g. means-tested programs).

Revenue and expenditure

Generous welfare states require high taxes and contributions. While the obligation that government expenditures are ultimately paid for by government revenues imposes a budget constraint on social policymakers, neither such constraint applies to individual attitudes nor to campaign rhetoric. Indeed, large sections, often majorities, of the electorate endorse generically worded expenditure cuts, while at the same time favouring specific spending increases (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2001: 143). Therefore, the logic of political communication in election campaigns dictates that parties emphasise the popular parts of their social policy agenda while downplaying its less popular ones.

As argued above, this is exactly the prediction that the saliency theory of party competition makes (Budge, Reference Budge2015; Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge, Farlie, Daalder and Mair1983b; Budge et al., Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001; Robertson, Reference Robertson1976). It assumes that there is one course of action favoured by most voters on any given issue. For instance, most voters prefer generous social benefits over less generous ones, yet they also favour paying less rather than more in taxes and contributions (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983a: 24–25). The revenue side of the welfare state (taxes, contributions or various forms of cost-sharing) is thus much less popular than the expenditure side (mostly cash transfers and in-kind benefits). It would hence be rational for parties on the right to couch their retrenchment agenda in terms of lessening the financial burden the welfare state imposes on taxpayers while showing less restraint on the expenditure side.Footnote 2 As a consequence, we should assume that left-right differences will be greater on revenue-related issues than on expenditure-related issues.

H1 Partisan conflict is more intense for issues related to revenue than for issues related to expenditure.

Deservingness perceptions

Another way to sell retrenchment to the broader public is to talk mostly about programs for groups that are not viewed as highly deserving. Deservingness considerations are very easily triggered and even override egalitarian values as predictors of welfare support (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011). People’s preferences about social policy programs are thus not only determined by their material self-interest and their welfare attitudes but also more strongly affected by the perceived deservingness of the benefit claimants (Cavaillé and Trump, Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Slothuus, Stubager and Togeby2011). Crucially for the purpose at hand, deservingness perceptions vary systematically across social programs and their beneficiaries. For instance, Jensen and Petersen (Reference Jensen and Petersen2017) show that health care politics are much less influenced by ideological and cultural differences than the politics of unemployment. High levels of perceived deservingness thus severely dampen political conflict.

Across countries, the literature typically finds a hierarchy of social groups, running from the highly deserving (the elderly, the sick, the disabled and families) to the less deserving (the unemployed and the poor) and to the least deserving recipients (immigrants) (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006).

This social hierarchy of deservingness creates a viable electoral strategy for parties that seek to cut social spending while avoiding popular backlash against their policy proposals. Assuming that retrenchment is more palatable to voters when it is targeted at programs for groups that are perceived as less deserving, parties on the right will focus their proretrenchment rhetoric on these policies, while avoiding talk about cuts to benefits for groups perceived as more deserving. As a result, left-right partisan conflict will be more pronounced when the social group affected by a program ranks lower in deservingness perceptions. One increasingly common example is the use of welfare chauvinism – the notion that natives should be entitled to the full range of benefits offered by the welfare state, while nonnatives should receive only limited support, if any (Careja et al., Reference Careja, Elmelund-Præstekær, Baggesen Klitgaard and Larsen2016; Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2018; Hjorth, Reference Hjorth2016; Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2012).

H2 Partisan conflict is more intense for social policies that benefit groups with lower perceived deservingness.

Degrees of redistribution

All social programs adhere to one of three principles of redistributive justice (Deutsch, Reference Deutsch1975): equity, equality or need. The notion of equity (also termed merit or proportionality) demands that an individual’s benefits are proportional to his or her contributions. This principle is enshrined in social insurance systems with earnings-related benefits. Equality implies that benefits are the same for everybody, a logic that is realised by providing universal benefits. Finally, the need principle holds that benefits should go primarily to those with the least material resources, thus requiring social programs to be means-tested (Clasen and van Oorschot, Reference Clasen and van Oorschot2002: 94).

These three types of benefit design produce different levels of redistribution. Since modern welfare states generate the bulk of their revenue from taxes and contributions on employment income, individuals with higher incomes will typically carry a larger financial burden. Thus, the welfare state is financed disproportionately by people on middle and higher incomes (OECD, 2018). As a result, earnings-related schemes produce lower levels of redistribution than universal benefits which, in turn, generate less redistribution than means-tested programs.

At the individual level, left-right ideology is strongly correlated with preferences for redistributive principles. Right-wing voters have a greater tendency to favour earnings-related over universal benefits and universal benefits over means-tested programs (Reeskens and van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and van Oorschot2013). This finding matches the (historical) preference of right-wing parties for status-preserving social insurance systems with earnings-related benefits. After all, social insurance schemes are a cornerstone of the conservative-corporatist welfare states that are typically found in countries with strong Christian democratic parties (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Kalyvas and van Kersbergen, Reference Kalyvas and van Kersbergen2010; van Kersbergen, Reference van Kersbergen2003).

One could, of course, argue against this logic that means-testing social benefits is a way to reduce program costs, and may therefore be attractive to the political right. Hence, the prominence of means-tested programs in liberal welfare regimes such as the United States (US). Indeed, Korpi and Palme (Reference Korpi and Palme1998) have shown that more targeting of benefits is correlated with less redistribution in the aggregate. However, since means-tested programs tend to activate “other-oriented” considerations and thus deservingness perceptions (Muñoz and Pardos-Prado, Reference Muñoz and Pardos-Prado2019), they are often politically more precarious than universal and earnings-related benefits (Laenen, Reference Laenen2018; Larsen, Reference Larsen2008). This is especially true in the US, where voters’ views of means-tested social programs are strongly driven by racial attitudes (Gilens, 1996; Reference Gilens2009).

H3 Left-right partisan conflict follows the degree of redistribution a social policy generates. It is most intense for means-tested benefits, less intense for universal benefits and least intense for earnings-related benefits.

Case selection: the Austrian welfare state

The test case for these hypotheses is Austria, a typical Bismarckian welfare state (Obinger and Tálos, Reference Obinger, Tálos and Palier2010), with a generous, yet (until recently) strongly segmented, social insurance system, family policies that tend to promote the male-breadwinner model and a fairly robust system of social assistance. Also, hardly any other country conforms as closely to the ideal-type of a coordinated market economy as Austria (Siaroff, Reference Siaroff1999). Strong corporatist institutions (social partnership) were established during the postWWII era, when the Christian democratic Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) and the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) shared power in national government (Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein1987; Kittel, Reference Kittel2000). While mandatory membership for employees and employers has helped the Chambers of Labour and Business retain much of their political influence, the decline of trade union density and the erosion of support for the two erstwhile major parties, SPÖ and ÖVP, have put Austrian social partnership under strain (Helms et al., Reference Helms, Jenny and Willumsen2019). The tradition of tripartite decisionmaking has therefore weakened, especially during the years when the ÖVP chose to govern with the populist radical right Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), from 2000 to 2007, and from 2017 to 2019 (Pernicka and Hefler, Reference Pernicka and Hefler2015).

While these periods of right-wing governance have produced some cost-saving reforms (as they have, in fact, some grand coalition governments before them), they have not lowered overall social spending markedly, in part because they typically expanded family benefits (Obinger and Tálos, Reference Obinger, Tálos and Palier2010: 119–120).

In addition to ÖVP, SPÖ and FPÖ, the Austrian party system during the observation period featured one of the strongest Green parties in Europe, and two smaller liberal parties, the Liberal Forum (LF, in parliament from 1993 to 1999) and Neos (from 2013). The analysis also includes the BZÖ (Alliance Future Austria), a break-away from the FPÖ that emerged in 2005 and was represented in parliament until 2013. The Austrian party system thus features all major party families in Europe.

There are several reasons why Austria is an interesting case for this study. For one, we should expect the overall level of left-right conflict over social policy to be limited. Strong corporatist institutions and the dominance of grand coalitions during the postwar era have certainly dampened partisan conflict over socio-economic issues. Also, the political right in Austria has never promoted a fierce agenda of retrenchment. In fact, the ÖVP fits quite nicely into the pattern of Christian democratic parties working in tandem with the left to expand the welfare state (van Kersbergen, Reference van Kersbergen2003). While the FPÖ has, at times, pursued economically liberal policies, it has, during the past decades, mostly been focused on the issues of reforming the political system and multiculturalism. As a result, findings from the low-conflict Austrian case should have a reasonable chance of holding up in other contexts.

Even though overall conflict over the welfare state may be relatively muted, FPÖ (since 2005) and ÖVP (since 2017) have become strong advocates of welfare chauvinistic positions (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2016; Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2020; Rathgeb, Reference Rathgebforthcoming). Thus, multiculturalism has not only become a powerful new dividing line in Austrian politics (Aichholzer et al., Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Wagner and Zeglovits2014) but it has also spilled over into the socio-economic realm. Therefore, Austria is a prime test case for the deservingness hypothesis (which prominently features welfare chauvinistic positions).

The welfare state in Austrian public opinion

The theoretical argument outlined above rests on several assumptions about public opinion on the welfare state. The most basic premise is that the welfare state and its core programs are popular. This is certainly the case in Austria, where the proportion of respondents who (strongly) agree that the government should take measures to close the gap between high and low incomes has ranged between 62 and 82% in all waves of the European Social Survey since 2002. In addition, when asked about specific programs, large majorities want to see spending levels on health (94%), pensions (94%) and unemployment benefits (72%) preserved or increased (Kritzinger et al., Reference Kritzinger, Thomas, Glantschnigg, Aichholzer, Glinitzer, Johann, Wagner and Zeglovits2016).

The three hypotheses stated above also build on more specific assumptions for which evidence is assembled in Table 1. First, H1 assumes that the revenue side of the welfare state is more popular than the expenditure side. Direct data on this question is difficult to come by, yet it is clear that voters’ enthusiasm for redistribution shrinks when the necessary trade-off (high taxes) is introduced. For instance, in the 2013 preelection survey (conducted by the Autnes), more than two-thirds (69%) agree (strongly) with government taking measures to reduce income differences (5-point scale). However, when asked to place themselves on a scale from 0 (low taxes, few benefits) to 10 (high taxes, many benefits), only 31% picked a value above the midpoint of the scale, and almost as many (27%) picked a value below the midpoint.

Table 1. Public opinion on the welfare state in Austria

H2 builds on the premise that there is a hierarchy of deservingness between groups. Data from the European Values Study (EVS, 2020) support this assumption: Austrians’ concern for the living standards of the elderly (85%) and the sick and disabled (83%) is far higher than for the unemployed (48%) or immigrants (35%).

Finally, H3 assumes that the tendency to prefer earnings-related over universal and universal over means-tested benefits is more pronounced among right-wing voters. Data from the fourth round of the European Social Survey (ESS, 2008) show that Austrians who place themselves on the left (0 to 3 on an 11-point left-right scale) support universal and means-tested benefit designs to a much greater extent than those on the right (7 to 10). Earnings-related benefits, by contrast, are much more popular among right-leaning respondents.

Taken together, the figures reported in Table 1 suggest that the assumptions about public opinion that underlie the three hypotheses apply reasonably well in the Austrian case.

Data and method

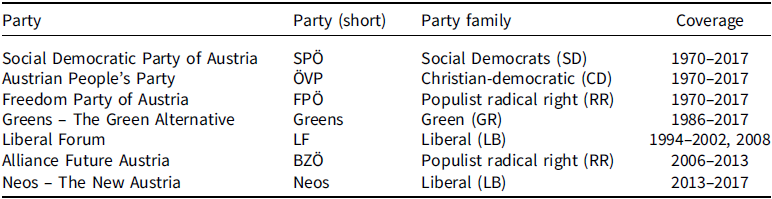

The data to test the hypotheses come from a fine-grained analysis of 65 election manifestos issued by seven parties in Austria between 1970 and 2017 (Table 2).

Table 2. Parties included in the analysis

Note: Elections to the Austrian Nationalrat took place in 1970, 1971, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1986, 1990, 1994, 1995, 1999, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2013 and 2017.

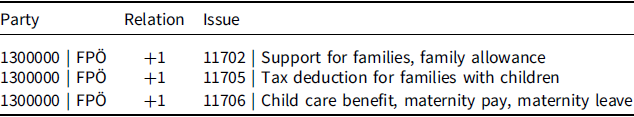

The manifesto coding approach developed for the Autnes is unique in both issue coverage and coding procedure. It transforms each natural sentence in a manifesto into standardised statements that typically take the form “(Party) for (issue)” or “(Party) against (issue)”. Take this bullet point from the FPÖ’s 2017 manifesto as an example: “Annual inflation adjustment for family allowance, child tax credit and child care benefit”. According to the Autnes unitisation rules, this demand will produce the following statements:

-

FPÖ for annual inflation adjustment of family allowance

-

FPÖ for annual inflation adjustment of child tax credit

-

FPÖ for annual inflation adjustment of child care benefit

These standardised statements are then recorded with three variables: the subject actor (in this case the manifesto party), the issue category (taken from a catalogue of over 700 issues) and the predicate – a numerical value that captures whether the relationship between the subject actor and the issue is one of rejection (−1), support (+1) or neutral (0). The three statements in our example will, therefore, be coded as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Coding example

These numerical codes thus capture the fact that the FPÖ has made supportive statements regarding the policies that fall under the three-issue categories (both generic support and demands for a benefit increase are recorded with a value of +1). Applied across thousands of natural sentences in dozens of manifestos, this approach produces an extremely detailed account of a party’s stated policy positions (for an in-depth description of the coding procedure and reliability tests, see Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser-Jedenastik, Müller and Winkler2016).

The dependent variable

The dependent variable is binary and records for each of the 18,219 statements whether it promotes a proretrenchment position (1) or not (0). The analysis has to be conducted at the statement level, since the three central independent predictors (corresponding to H1, H2 and H3) vary within parties, manifestos and policy areas. Aggregating the data to a higher level is therefore not an option.

Two steps had to be taken to arrive at the dependent variable. First, the “direction” of all 111 social policy issue codes in the data was coded as either expansionary (−1), neutral (0) or proretrenchment (+1) (see appendix for a full list). For example, the issue “health care spending” (issue code: 11304) was categorised as expansionary, because support for this issue signals that a party wants to maintain or increase health care expenditures. By contrast, the issue “patient contributions/fees for outpatient care” (11308) was classified as “proretrenchment”, because supporting this position implies shifting health care costs from the public to private individuals. A few issues could not clearly be classified as expansionary or proretrenchment and were therefore coded as neutral, for example, electronic health records (11315) or a uniform pension scheme (11603). In a second step, these directional codes were combined with the relational (predicate) values that signal whether a statement is in support of or in rejection of an issue (as shown in Table 3). All statements that recorded either support for proretrenchment issues or rejection of expansionary issues were classified as proretrenchment and thus coded 1 on the dependent variable. All other statements were coded as 0.

For the purpose of this paper, the data will only include manifesto statements referring to a welfare state category. In the above example, all three of the FPÖ’s statements concern social policy, and all three are expansionist. By contrast, were the FPÖ to advocate cuts in family allowances, the abolition of the child tax credit and a lower child care benefit, all three statements would be classified as proretrenchment. Neutral statements (with a value of 0 in the predicate variable) are never counted as proretrenchment. An alternative specification of the dependent variable with neutral statements reclassified into the proretrenchment category is presented in the appendix. The results are substantively identical to the ones presented below.

The independent variables

The three main independent variables for the analysis are the revenue–expenditure distinction, the perceived deservingness of the policy’s target group and the degree of redistribution. All are operationalised by classifying the 111 issue categories in the data (Table A9 in the appendix).

First, all issue codes referring to the financing of the welfare state are coded as “revenue issues”, whereas all those pertaining to spending money on cash transfers or in-kind benefits are classified as “expenditure issues”. Typical “revenue issues” include social insurance contributions, calls for (or against) tax-financing of certain benefits, but also all forms of cost-sharing (deductibles, co-pays) or financing of benefits and services by private actors (e.g. employer-sponsored pensions or private health insurance). A number of issues that fit neither description well are categorised as “generic” (e.g. working time regulations, collective bargaining or employment protection).

Second, in accordance with the literature (van Oorschot, 2000; Reference van Oorschot2006), the deservingness variable is coded as “low” for all policies targeting the poor, the unemployed and nonnatives. All other programs are coded as “high” (i.e. those serving the elderly, the sick, the disabled and families). A remainder category (generic) is used for all issue codes that do not imply a specific target group, such as “redistribution”, or “reform of chambers”.

Third, the redistribution variable records whether social programs are earnings-related, universal or means-tested. In general, coding was based on the character of the benefits that accrue to the recipient – even if the financing of those benefits follows a different logic. For instance, active labour market policy and health care are both classified as universal, yet they are (at least partly) paid for through earnings-related contributions. Also, social regulation was generally assumed to be universal in character. As above, a residual category (generic) captures those issues that do not fit into the three other groups (e.g. “trade unions”, “social partnership” or “atypical employment”).

Data overview

Taken together, the 65 manifestos analysed yield no less than 18,219 statements on welfare state issues. Figure 1 displays the proportion of statements in the party manifestos that address social policy issues. On an average, parties devote very similar levels of attention to the welfare state. The salience of social policy in the average party manifesto (indicated by the dashed horizontal line) is between 13 (Greens) and 16% (BZÖ), with no clear trend emerging over time. Left-wing parties (SPÖ and Greens) devote an average of 14% to welfare state matters – the exact same proportion as the average right-wing party manifesto. At least in the aggregate, there are thus no clear left-right differences in terms of issue attention.

Figure 1. Salience of social policy in party manifestos.

Note: Calculated as the percentage of statements in each manifesto that addresses social policy issues. Dashed horizontal lines represent means across a party’s manifestos. LF merged into Neos in 2014, therefore the two parties are grouped together in one graph.

By contrast, there are marked left-right differences in the proportion of proretrenchment statements. The left-wing parties have a consistently low share of proretrenchment statements (Greens and SPÖ), whereas the parties of the right (ÖVP, FPÖ, LF/Neos and BZÖ) display considerable overtime variation and notably higher averages on the dependent variable. More specifically, the average Green manifesto contains 6% proretrenchment statements among its social policy content, and the average SPÖ manifesto scores at 13%. For the right-wing parties, the figures are 31% (ÖVP), 37% (FPÖ), 45% (LF/Neos) and 22% (BZÖ), respectively.

Together, Figures 1 and 2 make a relevant point. While there clearly is a positional issue conflict (i.e. right-wing parties take more proretrenchment positions than their competitors on the left), this conflict does not result in a lower overall salience of social policy on the right. This implies that right-wing parties do not generally avoid welfare state issues, but that they find ways of talking about the welfare state that fit with their more proretrenchment agenda, while not jeopardising their electoral ambitions. This is exactly where we would expect partisan left-right conflict to be the most intense.

Figure 2. Share of proretrenchment statements in party manifestos.

Note: Calculated as the percentage of social policy statements in each manifesto that advocates for retrenchment. Dashed horizontal lines represent means across a party’s manifestos. LF merged into Neos in 2014, therefore the two parties are grouped together in one graph.

Figure 2 also suggests that a dichotomous left-right indicator captures a large proportion of the overall partisan differences in the data. Cramér’s V for a tabulation of the dependent variable across the seven parties is only marginally higher (0.30) than for a crosstabulation of the dependent variable with a dichotomous classification of parties as left-wing (Greens, SPÖ) or right-wing (ÖVP, FPÖ, LF, Neos and BZÖ) (0.28). Therefore, the analysis will proceed using this dichotomous left-right indicator.

Analysis

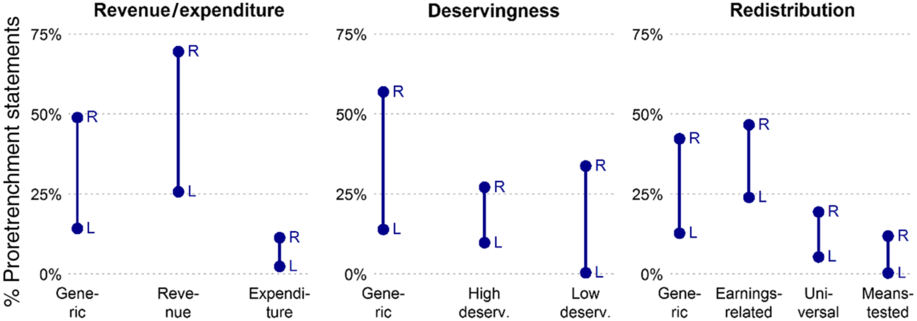

A first look at the bivariate relationships between the dependent variable and the three main independent variables is provided in Figure 3. Proretrenchment positions are always more frequent on the right, yet the gaps between the ideological camps vary quite substantially.

Figure 3. Proportion of retrenchment statements for left-wing and right-wing parties by revenue/expenditure, deservingness and redistribution.

In accordance with H1, revenue-side issues elicit a much larger gap than expenditure-side issues in the proportion of proretrenchment statements between left and right. The left-right difference in revenue is 44 percentage points, whereas it is a mere nine points for expenditure. This pattern is largely due to the fact that hardly any party ever openly advocates directly limiting welfare state services and transfers, whereas demands to cut the welfare state’s funding streams are more common. Similarly, the notion that lower perceived deservingness is associated with higher levels of partisan conflict (H2) is supported in the bivariate analysis. Yet, this is not only due to the right-wing parties promoting more retrenchment for these groups but also due to the complete absence of retrenchment proposals on the left. Partisan conflict also varies by redistributive principles, yet not in the way anticipated in H3. Contrary to expectations, the left-right gap is somewhat smaller for universal and means-tested programs than for earnings-related benefits.

These preliminary results should be taken with a grain of salt, though. After all, the three explanatory variables are strongly correlated (Cramér’s V scores between 0.32 and 0.45). As an example, consider the fact that many means-tested benefits go to groups viewed as less deserving. Therefore, it must remain for the multivariate analysis to detect whether these bivariate relationships hold after including all covariates at the same time. A crosstabulation of the three variables is reported in the appendix (Table A2).

The multivariate regressions are specified as binary logistic models with random effects at the manifesto level. Since manifestos are clustered within parties (i.e. a party’s statements at time t are not independent of its statements at t + 1) but also within election years (i.e. a party’s statements at time t are not independent of what other parties say at t), the models use two-way clustering, with standard errors clustered on both parties and election years (the implementation follows Gu and Yoo Reference Gu and Yoo2019). An alternative specification with one-way-clustered standard errors (on party-decades) yields virtually identical results (see Table A7 and Figure A4 in appendix), as do other specifications (e.g. one-way clustering on manifestos, parties or election years).

To test whether the three-issue characteristics outlined in the hypotheses (revenue/expenditure, deservingness and degree of redistribution) affect partisan conflict, these characteristics interact with a dichotomous party indicator (0 = right-wing party and 1 = left-wing party). This will tell us whether the propensity of left-wing and right-wing parties to promote retrenchment varies with the three explanatory factors outlined in the hypotheses. For instance, if parties across the ideological spectrum are equally (un)likely to argue for retrenchment of earnings-related benefits, the interaction effect of the left-party dummy and the indicator of earnings-related policies should be close to zero and statistically insignificant.

In addition, the model includes a number of control variables for which there are theoretical reasons to assume that they are correlated with the dependent and/or the main independent variables. First, the type of benefit (cash transfers, in-kind benefits or social regulation) is closely related to its redistributive design. For example, earnings-related programs typically pay cash benefits (e.g. pensions or unemployment insurance), whereas in-kind benefits are mostly universal (e.g. child care). Second, as previous research has shown that institutional reforms display greater left-right partisan effects than policy reforms (Klitgaard et al., Reference Klitgaard, Schumacher and Soentken2015), an indicator of institutional reforms is included. Third, the model features a dummy that denotes whether the incumbent government cuts across the left-right divide (i.e. SPÖ-FPÖ and SPÖ-ÖVP coalitions), because such crosscleavage coalitions may attenuate left-right partisan conflict. Finally, decade dummies are included in order to account for the possibility that partisan effects change over time. As with the main theoretical explanatory variables, all of these controls are interacted with the left-party predictor. This is because control variables for interaction effects need to be interacted with the moderating variable in order to properly eliminate confounding effects (Yzerbyt et al., Reference Yzerbyt, Muller and Judd2004). Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in the appendix (Table A1).Footnote 3

Since interaction terms are difficult to interpret from the regression coefficients directly, the figures further below display the average marginal effects (AMEs) of the left-party indicator for the different moderating variables.

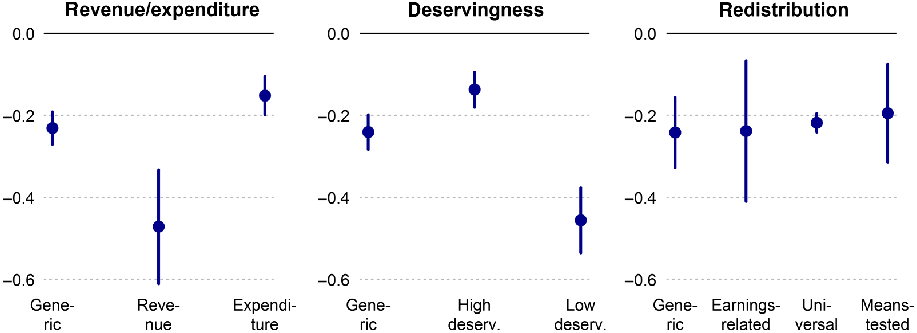

Figure 4 provides us with information to evaluate the three hypotheses outlined in the theoretical section. With regard to H1, the analysis finds a stark difference in the effect of the left-party dummy between revenue-side and expenditure-side issues. Left-wing parties are 47 percentage points less likely than right-wing parties to make proretrenchment statements on revenue-side issues, whereas the gap is only 15 points on expenditure-side issues. With regard to the multiple benefits that welfare states provide, the manifesto rhetoric of right-wing parties is thus much closer to that of the left than on questions of social insurance contributions, tax-financing of social programs or cost-sharing (e.g. through deductibles or fees). In other words, parties diverge much more when discussing how to finance the welfare state than when debating ways to spend the money. The evidence thus corroborates H1.

Figure 4. Average marginal effects (AMEs) of left party by (a) revenue/expenditure, (b) deservingness and (c) redistribution.

Note: AMEs with 95% confidence intervals, calculated based on regression model in Table 4.

Table 4. Binary logistic regression (DV: proretrenchment statement)

Note: Figures are unstandardised coefficients and two-way-clustered standard errors (on parties and election years) from binary logistic regression with random effects at the manifesto level, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Similarly, the deservingness hypothesis (H2) is strongly supported by the results. Left-right differences are very large for policies that target the unemployed, the poor or nonnatives. On these issues, the probability of a proretrenchment statement is 46 percentage points lower for left-wing parties than for their right-wing competitors. Yet the left-right gap shrinks to a mere 14 points for welfare programs catering to the elderly, the sick, the disabled and families. Partisan conflict is therefore considerably less intense on issues that relate to groups generally viewed as more deserving. As for H1, party competition adapts to electoral pressures and produces much greater crossparty consensus on more popular policies.

By contrast, H3 finds no support in the data. The marginal effects of left party for earnings-related, universal and means-tested programs are very similar in size (between −24 and −19 percentage points). No matter whether parties talk about earnings-related, universal or means-tested programs, left-wing parties are similarly less likely to argue for retrenchment. The differences that appeared in the bivariate comparison (Figure 3) disappear once other covariates are introduced in a multivariate model. For instance, means-tested benefits may elicit greater partisan conflict not because of their redistributive nature but because their recipients may be viewed as less deserving (Muñoz and Pardos-Prado, Reference Muñoz and Pardos-Prado2019).Footnote 4

To be sure, the findings in support of H1 and H2 may not be the most counterintuitive results. They are nevertheless important – not least because the effect sizes are substantial. The AMEs for revenue-side policies and low-deservingness issues are about three times the size of the AMEs for expenditure-side policies and high-deservingness issues. These factors are, therefore, not just minor conditionalities on left-right partisan conflict – they strongly structure the public communication of political parties on welfare state issues.

Discussion and conclusion

The dynamics of partisan conflict have shaped modern welfare states like few other forces. Yet, the comparative social policy literature often assumes (implicitly) that partisan conflict is similar across different domains of the welfare state. This paper uses fine-grained data on social policy statements in Austrian party manifestos to demonstrate that there is large and systematic variation in left-right conflict over the welfare state.

First, the analysis finds that partisan conflict is structured by the revenue–expenditure distinction. Revenue-side policies attract much greater levels of partisan conflict than those concerned with expenditures (i.e. social services and transfers). Second, parties of the left and right often are in agreement over policies targeted at groups that are viewed as highly deserving. By contrast, policies that primarily affect groups with lower perceived deservingness (the poor, the unemployed and nonnatives) produce much greater partisan differences. These results are in line with recent studies showing that parties tailor their appeals to specific social groups (Ennser-Jedenastik, Reference Ennser-Jedenastik2016; Thau, Reference Thau2019). Third, no differences were found for policies with different distributive logics. The levels of partisan conflict uncovered in the analysis were similar for earnings-related, universal and means-tested programs.

On balance, these findings support the premise that electoral considerations strongly influence public debates on social policy. As the core institutions of the welfare state retain their popularity even in the face of mounting financial pressure, parties strategically choose their battles. Proretrenchment arguments are thus much more visible in those areas where cuts are palatable to the median voter.

To be sure, the analysis in this paper is limited in that it covers only one country with one specific set of political and social policy institutions. The degree to which we can generalise to other countries is thus likely a function of their similarity to the Austrian case. However, many features of the Austrian case are, in fact, present in other West European democracies, especially those with multiparty systems, strong corporatist traditions and a Bismarckian welfare state.

With those caveats in mind, there are at least two important implications from this study. First, the results suggest that, in the public debate, there is a danger of misalignment between the areas of social policy that are most contentious and those that produce the largest financial burden for most advanced economies. Expenditures for pensions, family benefits, health and social care constitute the bulk of social spending in all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, yet partisan disagreement is focussed mostly on other areas (which is, of course, part of the reason that spending in these domains is high). This tendency may even exacerbate as the increased salience of immigration in Europe pushes welfare chauvinist appeals to the top of the agenda. For example, in its public communication, the Austrian government in office between 2017 and 2019 (a coalition of ÖVP and FPÖ) put great emphasis on cutbacks to family benefits and social assistance for immigrants, even though these reforms would make only the slightest dent in overall social spending.Footnote 5 The public attention devoted to an issue thus often corresponds weakly with its real-world significance.

The second implication is that the political debate over the welfare state tends to neglect the budget constraint that is inherent in social policymaking. While governments have to strike a balance between revenue and expenditure, the analysis shows partisan conflict to be much more intense when it comes to issues of financing the welfare state. This produces a disconnect between commitments to expand or maintain benefit levels and promises to cut taxes and contributions. In the Austrian case, parties regularly promise to finance large tax cuts by finding efficiencies “in the system”, implementing “administrative reforms” and merging social insurance organisations (a reform that is, in fact, likely to add costs in the short term). While electorally beneficial, this strategy makes it difficult for voters to consider the real trade-offs of taxing and spending that constrain policymaking in the welfare state.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/QX9MPS.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000240