Introduction

During the past decades, punctuated equilibrium theory (PET) has not only become one of the fastest developing subfield of policy studies (Weible Reference Weible, Weible and Sabatier2014: 10), but also a premier field of empirical studies concerning policy issue priorities. PET claims that it explains what separate theories of policy change on the one hand, and policy stability on the other hand cannot explain: policy dynamics (Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Mortensen, Weible and Sabatier2014: 59). It offers a new framework for understanding stasis and “large-scale departures from the past” in various policy domains by emphasising two elements of the policy process: “issue definition and agenda setting” (Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Mortensen, Weible and Sabatier2014: 60). This perspective “recognized the critical role of information in the policy process in a way that the election-centred model has not (and as) a consequence, agenda changes can occur in the absence of elections or public opinion” (Bryan, Jones, and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 6).

One of the corollary ideas of this research agenda is the “stick-slip dynamics” of the policy process (Bryan, Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 8–9). In the political system, institutions, ideologies and norms all play a part in stabilising behaviour and, therefore, add an element of friction vis-á-vis driving forces for policy change (such as interest group lobbying or social movements). This theory of stick-slip dynamics in public policy-making has been put to the test in a score of research articles with a domestic or comparative focus, and with geographical scope mostly covering the USA and Western European democratic countries (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009; Walgrave and Nuytemans Reference Walgrave and Nuytemans2009; Walgrave and Vliegenthart Reference Walgrave and Vliegenthart2010; Brouard Reference Brouard2013; Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Reference Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014; Bonafont, Palau, and Baumgartner Reference Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015; Vliegenthart et al. Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Bonafont, Mortensen, Sciarini, Tresch, Bevan, Jennings, Grossman and Brouard2015; Baumgartner, Breunig, and Grossman 2019).

While these studies focused on democratic countries in the Western world, some newer papers extended the scope of investigation to non-democratic countries such as the military regimes of Turkey and Brazil, the Russian case, Hong Kong and colonial Malta. (Lam and Chan Reference Lam and Chan2015; Chan and Zhao Reference Chan and Zhao2016; Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, and Yildirim 2017). In some cases, regime change is directly discussed from the perspective of PET (Or Reference Or2019). The most recent contribution to this literature (Bryan, Jones, Epp and Baumgartner Reference Jones, Epp and Baumgartner2019) provides a conceptual framework for analysing friction in different regimes, notably by focusing on the role of centralisation, incentives and information.

Yet, when it comes to another region with a turbulent past and multiple regimes changes, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), similar studies are few and far between (for two exceptions see (Boda and Patkós Reference Boda and Patkós2018; Sebők and Berki Reference Sebők and Berki2018). In light of this gap in the literature, the dual purpose of this article is to conceptualise policy dynamics for settings beyond liberal democracy and to extend the external validity of previous research on policy dynamics both in a geographical and historical sense. We investigate the core hypotheses of PET research in the context of a CEE country (Hungary) for a time period that covers multiple regimes: Socialist autocracy (1945–1990), liberal democracy (1990–2010) and a so-called “hybrid regime” (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010) which in Hungary is associated with the second and third Orbán governments (2010–2018).

The research question of this article concerns the differences of Hungarian regimes in terms of their public policy dynamics. We follow Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009: 608–609) and Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, and Yildirim (2017) in testing four hypotheses. The first is the General Punctuation Hypothesis (H1), which states that output change distributions from human decision-making institutions dealing with complex problems are characterised by stability interspersed by events of punctuation as measured by a positive value of its most widely used statistical indicator (kurtosis). The second hypothesis, regarding “progressive friction” (H2), posits that these kurtosis values increase as we move from input to process, and from process to output series. The third hypothesis regarding “informational advantage” (H3) states that the level of punctuation is higher in less democratic regimes. The fourth one refers to a “hybrid anomaly”, which states that the level of punctuation is the highest during hybrid regimes vis-á-vis all other regimes.

We test these propositions in the context of Hungarian politics and public policy following World War II. This extension provides geographical, political and socio-economic breadth to extant research. Our analysis lends support to the general punctuation and the progressive friction hypotheses. The informational advantage hypothesis is also partly upheld by our evidence. However, we find limited evidence for the hybrid anomaly, which only exerts itself in the latter sections of the policy process. These results complement the findings of Sebők and Boda (Reference Sebők and Boda2021): while their book analyses Hungarian policy-making and agendas between 1867 and 2018 from a qualitative and case-based perspective, we use a quantitative research design for comparing regimes of a shorter period (covering the regimes between 1945 and 2018).

In the following, we first provide a review of the relevant literature and the sources of the hypotheses tested. Second, we provide historical context and institutional detail related to the role of interpellations and laws in policy-making in settings beyond liberal democracy. Next, we explicate our case selection and present the data and methods used. The following section provides an empirical analysis of issue attention based on four of our hypotheses. The Discussion section evaluates the results in light of the extant comparative literature as well as the methodological problems associated with conducting comparative research on PET. The final section concludes by returning to the substantive question of the sources of dynamics in an inter-connected system of policy venues and agendas.

Theory

In the past two decades, the PET of public policy (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1991, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2002, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2010) has turned into a widely tested, and largely supported, theory of the policy dynamics of Western democracies (see e.g. Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009; Breunig, Koski, and Mortensen Reference Breunig, Koski and Mortensen2009; Mortensen et al. Reference Mortensen, Green-Pedersen, Breeman, Chaqués-Bonafont, Jennings, John, Palau and Timmermans2011). Yet, in parallel to the emergence of this literature, a new trend took hold on the periphery – and later: in the midst of – developed democracies with substantial effects on how policy decisions were made. This novel phenomenon was the rise of hybrid regimes and illiberal policy-making in an era of what was supposed to be “end of history”.

The political systems in question adopted key procedural characteristics of democracy, such as regular elections, while simultaneously displaying attributes more closely associated with authoritarian regimes, from the repression of the free press to infringements of civil rights. These regimes defied traditional categorisations and have been identified as, inter alia, competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2002), electoral authoritarianism (Schedler Reference Schedler, Landman and Robinson2015), illiberal democracy (Zakaria Reference Zakaria1997), backsliding democracies (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), and, perhaps most often, as hybrid regimes (Diamond Reference Diamond and Diamond2015). Hungary under the leadership of prime minister Viktor Orbán was often mentioned by politicians and scholars alike as an ideal–typical case of such democratic backsliding.

Throughout most of its history, the development of Hungarian parliamentarism did not diverge substantially from the Western European model (Pesti Reference Pesti2002: 103; for a complete classification of regimes based on various sources see: Bódiné Beliznai and Mezey Reference Bódiné Beliznai, Mezey and Mezey2003: 107–110; Föglein, Mezey, and Révész T. Reference Föglein, Mezey, Révész T and Mezey2003: 315–319; Sebők and Berki Reference Sebők and Berki2018: 611). After the liberation of Hungary from Nazi occupation from 1944 on, an instable democracy was installed in which Soviet influence was overwhelming. This was followed by the de jure takeover of Hungarian democracy by USSR-aligned domestic forces in 1949. In the pseudo-parliamentarism of this Socialist autocracy between 1949 and 1989, the central role of the Hungarian parliament was abolished, marking an exception in Hungarian political development (Pesti Reference Pesti2002: 163; Horváth Reference Horváth and Mezey2003: 468). The fall of this regime, and the establishment of a democracy in 1989/1990, resulted in the restoration of the central role of parliament in the Hungarian polity.

In a further development, the electoral victory of Viktor Orbán’s right-wing populist Fidesz party in 2010, and the subsequent constitutional and policy changes, started a long-standing debate on the characteristics of the new Hungarian political regime. Many authors pointed to Orbán’s new regime when describing the general backsliding of democracy in CEE (Ágh Reference Ágh2013; Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2013; Greskovits Reference Greskovits2015; Hanley and Vachudova Reference Hanley and Vachudova2018). There is some debate when it comes to the finer details of this development. Lührmann and Lindberg (Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019) cite an outright autocratisation of the regime while Batory (Reference Batory2015) describes the role of Fidesz as a populist-in-government phenomenon.

Some authors classify this process as an illiberal backlash (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2018) noting that the decreasing role of liberal ideas had been originated in the period before 2010. The result of this ‘backlash’ is usually seen as a creation of a (diffusely) defective democracy (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2018) or (externally constrained) hybrid regime (Bozóki and Hegedűs Reference Bozóki and Hegedűs2018; Böcskei and Szabó 2019). What is less clear, to what extent can changes be compared to Russia, this model polity of a hybrid regime (Buzogány Reference Buzogány2017). We conclude from this brief overview of the literature that the post-2010, “hybrid” regime of Hungary is at least worth investigating if we are interested in the external validity of well-established theories of policy dynamics.

What are the characteristics of policy-making in non-democratic settings? The selectorate theory Bueno de Mesquita and his co-authors (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson and Smith1999; Bueno de Mesquita and Smith Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Smith2011) posits that the size of the “selectorate”, that is, the group of people which has an institutionally granted right or norm choosing the government, influences the substance of decisions made by the government. In a similar manner, Svolik (Reference Svolik2012) explores the logic of party-based co-optation in autocracies which governs the hierarchical assignment of services and benefits.

In these theories, policy-making is subordinated to regime survival which may distort the traditional role of the policy agenda in liberal democracies which is to gather and filter information that guides public policy decision-making. Consequently, policy agendas in autocracies and hybrid regimes may be more punctuated than in liberal democracies. In light of these theoretical considerations, our article pursues the dual aim of conceptualising policy dynamics for non-democratic polities and to extend the punctuated equilibrium framework to hitherto under-studied regime types, periods and regions. We undertake this challenge by investigating four hypotheses derived from the relevant literature. We first test three hypotheses originally formulated by Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009: 608–609) and Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, and Yildirim (2017), as well as a fourth one based on Sebők and Berki (Reference Sebők and Berki2018).

The first of these is the general punctuation hypothesis (H1), according to which “output change distributions from human decision-making institutions dealing with complex problems will be characterised by positive kurtosis”. PET states that policy change does not occur in incremental steps but is “often disjoint, episodic, and not always predictable” (Bryan D Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 1). This school of thought was built on the empirical finding of Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones1991) that the distribution of policy changes over time does not follow the normal distribution – instead it is characterised by punctuations which can be quantified by the deviation from the Gaussian distribution at the tails of the distribution of changes (this deviation is often measured by the statistical metric of kurtosis).

This general, yet empirical theory was later underpinned by a theory of information. Policy outputs are not a direct function of societal inputs as decision-making that may display the characteristics of a “stick-slip dynamics” (Bryan D Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 8–9). This uses an analogy from the study of earthquakes: both a dynamic force pushing on the earth’s tectonic plates and a retarding force (called friction) contribute to its status. If “the forces acting on the plates are strong enough, the plates release, and, rather than slide incrementally in adjustment, slip violently, resulting in the earthquake” (Bryan D Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 8). By using the earthquake analogy, it relates the dynamic force pushing on the earth’s tectonic plates to public inputs and the retarding force, or friction, to institutional inertia. They stabilise behaviour in a progressive manner: as the number and organisational scale of institutional players grow, friction is also expected to increase in size (Bryan D Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012: 8).

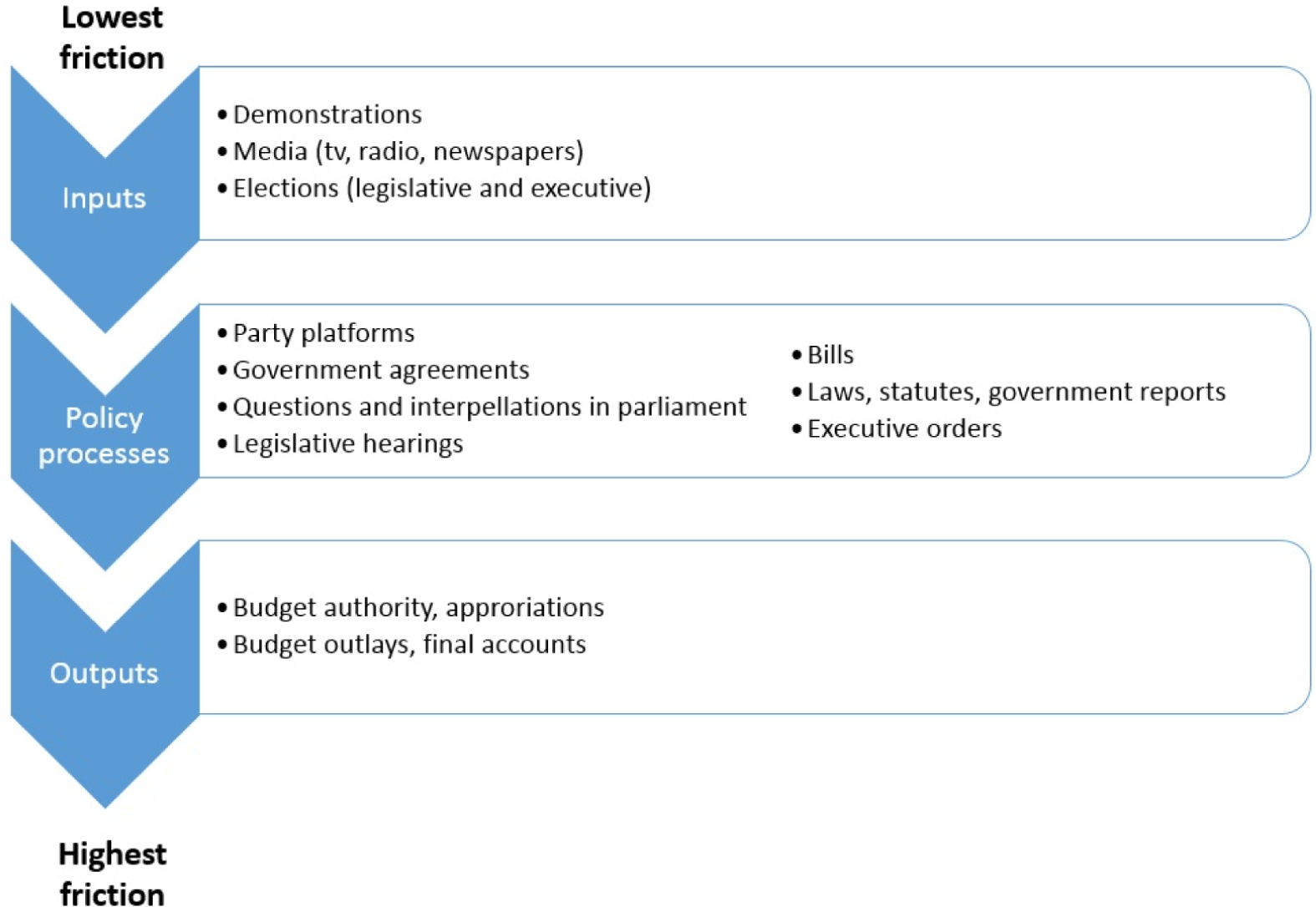

The friction hypothesis focuses on the role of various policy agendas play in shaping policy outputs (such as laws) or outcomes (e.g. budget outlays). Figure 1 presents how various data sources used in the empirical literature align on this progressive friction scale. The underlying idea for the friction process is simple: the number of issues a politician can handle at a time is limited, so it is of great importance which issues the decision-maker addresses.

Figure 1. Progressive friction in the three phases of policy representation. Adapted from Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009: 611).

Extensive media coverage of one issue or political demonstrations related to another can have a marked impact on party preferences. These information sources may be referred to as political inputs for policy decisions (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009: 605). These are social processes that governments monitor and act upon and may include information from social movements, the mass media, lobbyists, systematic data collection (such as the unemployment or the poverty rates). Yet as we move throughout the policy process, the actionable universe of information narrows due to the bounded rationality of decision-makers. Translating this theoretical finding to a falsifiable hypothesis, we can posit that kurtosis values will increase as one moves from input to process to output series. This is our second hypothesis which is called progressive friction.

These notions of punctuated equilibrium and progressive institutional friction have served as the springboard for an ever-evolving empirical research agenda. Besides input–output analysis connecting public preferences and public spending (Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2005), virtually all intervening aspects of the general linkage process have been examined in a piecemeal manner for various variable pairs gauging the effect of public opinion on agendas venues such as political campaigns (Bevan and Krewel Reference Bevan and Krewel2015) or executive speeches (Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009). The comparative testing of the friction hypothesis has yielded results that support this pattern (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009; Green-Pedersen and Walgrave Reference Green-Pedersen and Walgrave2014). Nevertheless, only limited testing has been undertaken for several regions outside the USA and Western Europe, such as the CEE area.

The investigation of this region from a PET perspective does not only provide for an extension of the external validity of the literature, but also offers cases which allow for the comparison of policy dynamics in different political regimes. Most CEE countries have experienced multiple regime changes during the 20th century. In Hungary, the polity was in almost constant flux with regime changes in 1918, 1919 (twice), 1944, 1945, 1949, 1956 and 1990. Despite the relatively understudied nature of regime dynamics in PET, we can rely on a few studies which directly addressed this issue.

A study on Hong Kong showed that the main characteristics in the dynamics of policy changes in not-free regimes are similar to those of free regimes (Lam and Chan Reference Lam and Chan2015: 552). Looking at the People’s Republic of China, Chan and Zhao (Reference Chan and Zhao2016) complemented this insight by pointing to the difficulties in data collection in the case of not-free regimes, which exacerbates punctuation. Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, and Yildirim (2017) analysed rival hypotheses by comparing free, partially free and not-free periods in Russia, Turkey, Brazil and Malta. They only found evidence for the informational advantage theory which claims that free regimes can collect information about the socio-economic environment more effectively. In not-free and partially free regimes, the media is constrained, civil society is controlled or repressed, and the opposition’s activity (if it can exist in a legal form) is limited by the government. All these actors can be considered as part of the polity’s policy capacity (Boda and Patkós Reference Boda and Patkós2018), as they mediate the relationship between state and society. Without their contributions, the flow of valid societal information for policy-makers is impeded. Hence, non-democratic regimes suffer an “informational disadvantage” (Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, Yildirim, et al. 2017).

It means even if non-democratic or hybrid regimes were interested in solving policy problems, they would be less competent to do so. A case in point is local environmental pollution. In an autocracy, the media may not report it, NGOs may be limited or forbidden to protest against it and even citizens may have fewer venues to raise their objection. The probability of noticing the problem by the government is much lower than in a free regime. (We return to this theoretical framework below when presenting our hypotheses.)

Baumgartner, Carammia, Epp, Noble, Rey, and Yildirim (2017) analysed the rival hypotheses of institutional efficiency and informational advantage by comparing free, partially free and not-free periods in the histories of Russia, Turkey, Brazil and Malta. Institutional efficiency means that a more limited separation of powers in not-free regimes makes it possible for the latter to react more quickly to changes in the environment. The notion of informational advantage refers to the theory that free regimes can collect information about the socio-economic environment more effectively. Therefore, kurtosis is higher in free regimes than in not-free or partly-free regimes. The study by Baumgartner and his co-authors found support for this latter hypothesis which also serves as our third hypothesis.

We derive our final hypothesis from one of the few studies focusing on the CEE region, Sebők and Berki (Reference Sebők and Berki2018), which covers over 155 years of Hungarian budgetary history. Their investigation lends support to the theory of punctuated equilibrium and they provide empirical evidence for the validity of the informational advantage hypothesis, which states that democracies will show a lower level of kurtosis than other political regimes. Nevertheless, the highest levels of punctuation were associated with “partly free” (as opposed to “not free” or “free”), which, in their view, creates an anomaly pointing to the further investigation of in-between regimes. This hybrid anomaly which states that kurtosis is the highest in hybrid regimes serves as our fourth hypothesis.

Historical context and political institutions

The general punctuation theory posits an “empirical law” (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009) which – according to its proponents – should hold regardless of context. The theoretical reasoning behind the progressive friction hypothesis is similarly universal: information processing faces bottlenecks as we move closer from agenda setting to decision-making as the bounded rationality of top-level office holders is a reasonable expectation regardless of whether they operate in democracies or autocracies. In the case of the other two hypotheses, it is at least conceivable that they may take on alternative interpretations depending on the specific circumstances of their application. In this section, we illustrate their logic as they concern the three distinct regime types covered in this study. In this, we present the institutional context in which we can elucidate our core quantitative results to be presented below.

One of the most evident instruments of the exercise of this supervisory role is parliamentary questions (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin, Vanberg, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014: 440). Among the various types of parliamentary questions, interpellations have played a preeminent role in the operations of the Hungarian parliament over multiple political regimes. Interpellations are typically a major tool in the hands of the opposition for holding the government accountable, which is why it is interesting to compare their role with the function they fulfil in regimes that do not have a parliamentary opposition.

The frequency of amendments of the Standing orders governing interpellations was surprisingly low in the period investigated (Sebők, Molnár, and Kubik Reference Sebők, Molnár and Kubik2017). The roots of the institution of interpellation can be traced back to the end of the 18th century. It was included informally, without being expressly enshrined, in the Standing orders starting in 1848, and it was formally established in 1868 (Palasik Reference Palasik2017: 171). Although the legislatures in the partly democratic eras between 1944 and 1949, the non-democratic period between 1949 and 1990 and in the democratic one since 1990 differ fundamentally in terms of their respective roles, the formal institution of interpellations was a staple of parliamentary procedures. After a brief hiatus, the institution was immediately restored with the end of World War II in Hungary, in 1944, albeit in a limited form.

The full text of interpellations had to be introduced at least a session day before their presentation. MPs could ask one interpellation by day, and the content of interpellation could contravene the foreign interests of Hungary. 15 minutes were allocated to present the interpellation, and a vote was held immediately after the answer of the minister assigned to answer the question. The usage of parliamentary questions flourished in the short-lived, democratic post-war period (more than 100 were introduced by year on average).

Nominally, the tradition was retained in the emerging Socialist autocracy with a new Standing orders adopted in 1950, but it was visibly hollowed out. It failed to include detailed regulations reflecting interpellations (it did not specify, for example, when interpellations needed to be submitted, when they could be presented in the plenary, how a response was to be given, etc.), and the National Assembly was not given the option of rejecting a minister’s answer (it could merely put it on the agenda). It is important to point out that the minister’s obligation to respond was retained, as well as the representative’s right to offer a rebuttal, along with the plenary’s vote on the minister’s response. Subsequently, the range of institutions that could be subjected to interpellations was expanded. The new rules also specified several other details: how interpellations were to be submitted in writing and presented orally, and how the response was to be provided.

The next amendment concerning interpellations occurred in 1967, and this allowed for the interpellation of state secretaries and mandated that responses which had been voted down would be referred to the parliamentary committees for further debate. A 1972 amendment opened up the possibility of interpellating the president of the Supreme Court – it constituted an overt rejection of the principle of the separation of powers. Following the elections of 1985, as a result of which some ‘spontaneous candidates’ won seats in the National Assembly, the legislature began to assume greater autonomy (thus, for example, on November 26, 1988 it took the unprecedented step of vetoing a decree law of the Presidential Council), and as a result the right of interpellation was restricted. The deadline to submit an interpellation was more restrictive, and the range of issues that could be addressed in an interpellation was limited to unlawful actions, the failure to perform legally mandated procedures, and so-called “ineffective” laws. The latter restriction was repealed in 1989. Footnote 1

In line with the separation of powers that was established as a fundamental structural framework during regime transition, from 1990 on the scope of persons who could be interpellated was restricted to the Council of Ministers (the cabinet), its members and the chief prosecutor. In addition to requiring that interpellations be submitted four days in advance, the 1994 amendment also specified detailed rules on how these could be presented in the plenary; the timeframe for interpellations; the rules concerning the substitution of officials who were being interpellated and the committee reports drafted in response to rejected answers to interpellations. The 1997 amendment also extended the right to present at least some of the interpellations they had drafted to representatives who were not affiliated with a parliamentary faction (yet at the same time it slightly shortened the time allotted to answers and rejoinders, which, we note, should have no effect on the underlying topic distribution).

The most recent (restrictive) amendments of the right to interpellation in our period under investigation occurred in 2010 and 2012. At the end of the former year, the right to interpellate the chief prosecutor was removed, and in the latter year the guarantee of the non-partisan representatives’ right of interpellation was struck from the rules (it was later eased). Footnote 2 The exclusion of the chief prosecutor shrank the opposition’s toolkit to highlight cases of government corruption. At the same time, interpellations were ever frequently used by government MPs to praise policy decisions or echo talking points from communication campaigns against various “enemies” of the state from migrants to “Brussels”.

The theoretical takeaway from this brief comparison of the usage of interpellations over the three regimes in question points toward the key role of limitations on this institution as means of effectively channelling popular pressures to the political agenda. In Socialist autocracy, informal rules allowed for the arbitrary exclusion of certain agenda items. Restrictions on the number of parliamentary questions per week may contribute to a less diverse agenda as secondary topics are neglected altogether. In the illiberal hybrid regime, the strategic misuse of interpellations for the purposes of government campaigns will create an issue centralisation (and, consequently, higher punctuation as these priorities are changed) atypical of liberal democracies.

Turning to legislation, in the era of Socialist autocracy MPs had a minimal influence on law-making. Only six laws accepted between 1949 and 1990 were introduced by MPs who were not members of cabinet (and three of those were introduced in transition year of 1990). The Council of Ministers, the Presidential Council, the MPs, the committees (from 1972) and party groups (from 1989) had the right to initiate laws (Kukorelli Reference Kukorelli1989: 86). Yet the National Assembly adopted a relatively few classical “laws” – the legislative function was overtaken by the Presidential Council which assumed legislative powers in-between formal sessions of parliament.

This practice was rooted in the setup of the political system of the Soviet Union (Skilling Reference Skilling1952: 210). Most members of “elected” bodies held no real power, which was wielded by executive committees (such as the Politbüro) or presidential councils (Little Reference Little1980: 235). The socialist Constitution (Act 20 of 1949) declared that during the breaks of plenary sessions, the Presidential Council elected from the MPs had all rights of the National Assembly (except for modifying the Constitution). The Presidential Council was not allowed to make laws but was very much entrusted with adopting so-called decree laws which had the same effect (but had to be ex-post approved by the plenary session – which almost always happened in a unanimous fashion – (Romsics Reference Romsics2010: 338).

This situation changed in the years before regime change. The 10th Law of 1987 forbade the Presidential Council to adopt decree laws in policy areas which had to be regulated by the National Assembly, thus the number of adopted “regular” laws increased. Furthermore, for the first time since the late 1940s, the 1985–1990 legislature was the first one to feature “spontaneously” elected MPs (Kukorelli Reference Kukorelli1988: 10). This was a sign of a disintegrating state party system and an advent of democratic practices in parliament (Bihari Reference Bihari2005: 392–393).

A more diverse party system ushered in a legislative agenda which was now unfettered from its previous formal and informal limitations. For 20 years of liberal democracy, this became the new normal, only for illiberalism to restrict opposition rights and almost completely eradicate adopted laws which had been originally proposed by opposition MPs. In sum, the roots of the hybrid anomaly are situated in the managed nature and hollowing out of post-2010 democracy in Hungary.

Data and methods

The quantitative analysis of this article is related to data for Hungarian policy agendas covering the period between 1945 and 2018. The Hungarian case offers a unique extension of the core research direction of the Comparative Agendas Project in multiple dimensions. The 73-year long period covered in this study is amongst the longest one in the extant literature. We also compare three distinct regime types – Socialist autocracy, liberal democracy and an illiberal hybrid regime – a unique combination. This setup also allows for leveraging regime variety in a distinctive way. It is also the first such study for the Central Eastern European region which, at the same time, makes use of a diverse collection of data sources.

While in and of themselves the results of this analysis refer to a single case, the external validity of the conclusions is reinforced by the fact that they tie into a growing body of research on policy-making in non-democratic polities. We also note that the descriptive statistics presented (including the punctuation metrics to be presented below) does by no means constitute a causal analysis. Yet an intra-case comparison of political regimes and time periods, as well as the inter-case comparisons with studies employing similar metrics do contribute to a deeper understanding of policy dynamics beyond liberal democracies.

With these qualifications in mind, in this article, we rely on conventional statistical means of capturing punctuations in policy time series. This standard approach is based on the density function of year-on-year or electoral cycle-on-cycle changes in the issue attention allocated to different policy topics (the Comparative Agendas Project codebook lists 21 of those from education to defence – we return to this point below).Footnote 3 “Fat-tails”, at either or both tails, of these density functions are generally associated with punctuated equilibrium. In statistics, these deviations from the normal distribution are captured by a so-called kurtosis indicator, with L-kurtosis (LK) being widely considered to be the best measure availableFootnote 4 (Breunig Reference Breunig2006: 20).

We test these propositions in the context of Hungarian politics and public policy following World War II in order to provide more geographical, political and socio-economic breadth to extant research. Data were collected under the aegis of the Hungarian Comparative Agendas Project (Boda and Sebők Reference Boda, Sebők, Baumgartner, Breunig and Grossman2019). In the event, four data series were selected covering a wide range of political processesFootnote 5 and with each of these datasets representing a specific phase of the friction process as postulated by the hypotheses. Table 1 presents the data sources.

Table 1. Data sources as placed in the institutional friction process

Our datasets have been classified based on the conventions of the Comparative Agendas literature which focuses on the position of these venues in the policy cycle. This means all policy agendas data can be defined as part of the input, process or output phase of the policy cycle. (see Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009). We can investigate data on interpellations, laws and decree laws and budget proposals and final accounts (or outlays – see Table 1). The allocation of these sources is well-established in the literature – here, we only highlight one potentially controversial classification. The output phase of the policy process is associated with budgets. Although state budgets are generally adopted as laws, there are special requirements and special rules to adopt them. The cost of their adoption is significantly higher than the adoption of “regular” laws (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009, 610). Some budget laws also reflect policy outcomes (as opposed to policy outputs which is what laws are in this literature). Besides budget proposals adopted by the legislature prior to the fiscal year in questions final accounts provide an overview of actual budget outlays which explains their separation for laws which do not have such retrospective application.

We used these sources to calculate data on issue attention changes in each policy domain based on government cycles (four or five years, depending on the period in questionFootnote 6 ).

Table 2 provides an overview of the original datasets (without the exclusion of a few extreme values).Footnote 7

Table 2. Description of the datasets

All four datasets were compiled in the Hungarian Comparative Agendas Project (cap.tk.hu). The number of observations for each dataset reflects the different composition and coding level of the underlying data sources. Our unit of analysis is the electoral cycleFootnote 8 and we used the proportion of interpellations and laws of the given policy domains by cycle (calculated for example as the macroeconomics topic share of 1994–1998/that of 1990–1994 minus 1).

We set our unit of analysis in electoral cycles instead of the more widely used years due to the fact in the socialist period only a handful of interpellations were presented in parliament per year. While in 1973 there were 18, in 1975 there was only 1 and in 1976 no vote was held on interpellations. Since one can only meaningfully calculate PET-style punctuation metrics based on bigger and more diverse counts (as for low numbers most policy topics would not yield a valid ratio), we opted to aggregate all data to electoral cycle to make them comparable.

More specifically for budgetary data, we used the average proportion of budget expenditures by major topic in every electoral cycle. This makes the data comparable and resolves the methodological problems caused by inflation and the different lengths of electoral cycles (since we compare issue attention shares, no nominal data is directly used). We classified every budget and law to an electoral cycle based on the exact date of when they were enacted. Interpellations were assigned to the cycle when they were presented. Cycle/cycle changes differ due to the unequal distribution of zero-value observation pairs (when for a policy topic, no observation is recorded for the given electoral cycle).

The interpellations dataset contains interpellations performed in the National Assembly between 1945 and 2018 (from the 1945–1947 to the 2014–2018 electoral cycle). An interpellation is a type of oral question (also submitted in a written form). It is a classical means of parliamentary supervision ensured to the opposition. Interpellations can be asked by any MP to any member of the Government concerning issues belonging to the portfolio of the given ministry (except for the Communist era, when – due to the principle of the unity of the branches of power – leaders of the judicial system could also be interpellated). No interpellations were asked during the Stalinist era of 1949–1953, thus the changes for 1953–1958 are compared to the agenda of the 1947–1949 electoral cycle.

Our database concerning laws and decree laws adopted by Parliament from the electoral cycle 1944–1945 to the electoral cycle 2014–2018 (no laws were adopted in 1944 in the first cycle in question). National representative bodies (parliaments) of Soviet-occupied parts of CEE adopted many aspects of the Soviet Union’s political system (Skilling Reference Skilling1952: 210), including a division of labour in which not all MPs participated in law-making. This task was also assigned to “executive committees” or “presidential councils” which “filled in” for parliament during the long breaks between plenary sessions (Little Reference Little1980: 235). Therefore, we included the decree laws issued by the “Presidential Council of the People’s Republic” (which existed between 1949 and 1989) in our datasets besides “regular” laws. These decree laws had the same effect as laws: they could nullify or amend each other.

The data on budget proposals and outlays comes a dataset which contains information about Hungarian adopted budgets and final accounts for the period 1947–2013. Each entry was coded by an automatic text classification algorithm for policy content, along with other variables of interest. We calculated the average proportion of major policy topics in budgets by electoral cycle, and we investigate the level of change regarding these averages. It is important to mention that for some years’ we had a missing data problem,Footnote 9 which led us to omit them from our calculations.

In our baseline scenario, we divided the total time period covering the 1945 through 2018 into three subperiods. The first one is the era of “Socialist autocracy” era. Although a Soviet-style constitution was only adopted in 1948/49, we also included the short preceding period of limited parliamentarism (1944–1949) in this first era as it was hallmarked by ever-increasing Soviet influence. We also list here the transition electoral cycle between 1985 and 1990. Taken together, the years between 1945 and 1990 are characterised as “not free”. The second era of our baseline scenario is the democratic post-regime change era between 1990 and 2010. Finally, we differentiate from this previous period the first two electoral cycles of the “Orbán regime” (from 2010 to 2018) which is widely regarded to be a hybrid regime as opposed to a completely free democracy.

Given the ambiguities surrounding regime categorisations, we also calculated scores for each of our hypotheses for alternative classifications of some electoral cycles of debated political nature. Therefore, first we calculated separate scores the “restricted” Socialist period covering 1949–1985 (this excludes the limited democracy of the 1940s and the transition period of the late 1980s). Second, we also analysed the post-regime change period from 1990 to 2018 as a whole (thus including the post-2010 “Orbán-regime”).

Third, we investigated alternative candidates for hybrid regimes including the 1944–1949, the 1985–1990 and 2010–2018 periods. While these periods were utterly different (for example in 1985 only candidates of the ruling party could run in the elections, although they had to compete with each other in every electoral district), a common thread in many historical analyses regarding these years that they were neither fully non-democratic, nor fully democratic.

Empirical analysis

In this section, the empirical results regarding policy change density functions are presented for each of the four data series. Most cycle-on-cycle changes were incremental (close to zero) with a few extreme values of over 5 (an increase of 400% over 100% in the previous cycle). The distribution of the degree of changes shows similar characteristics for the four dataset types.

As for interpellations, our dataset had 6547 initial observations elements for the period 1945–2018. Using these data, we calculated the cycle-to-cycle percent change in issue attention resulting in 306 observations across the 21 major topics of our policy codebook. The data, as witnessed by the shape of the histogram in Figure 2, yields support for PET. The data shows a high peak close to 0 and a fat tail to the left, while the right tail is long and flat.

Figure 2. Density function of issue attention changes.

In the case of laws and decree laws, our initial database consisted of 5963 laws and decree laws. Our calculations of the cycle-on-cycle percentage change resulted in 351 observations. The histogram is quite similar to that of interpellations’, although it has a slightly longer right tail and shows a steeper decline for values below zero (see Figure 2).

Finally, we investigated the topic distribution of 116,313 line items covering the period between 1947 and 2013. This resulted in 287 observations for cycle-on-cycle changes. The respective histogram affirms a distribution that is in line with PET. Here, we see a longer right tail of the distribution, as well as a few extreme negative changes (see Figure 2).

Our first hypothesis is related to the frequency distribution of cycle-to-cycle policy output changes in various policy domains. Also called the general punctuation hypothesis, it states that “output change distributions from human decision-making institutions dealing with complex problems will be characterised by positive kurtosis”. Table 3 presents the kurtosis and LK results for the complete period between 1945 and 2018. Our data offers clear support for H1. K and LK values for each dataset are significantly above the respective value of the Gaussian distribution (0, 12), with even the lowest score (for interpellations) surpassing this baseline value by 100%.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of policy process phases

The second hypothesis states that “kurtosis values will increase as one moves from input to process to output series”. In our analysis, we found evidence supporting this “progressive friction” hypothesis. The element of progressive friction is evidently present in the process–-output conversion: LK values for the output series are at least 0.06 higher than any value for the previous phase. Punctuations related to budgeting (both budget authority and outlays) are bigger than in any other datasets and significantly surpass the value associated with the Gaussian distribution. This result adds further evidence to the growing literature on the outstanding relevance of punctuated equilibrium in the field of fiscal policy.

The third hypothesis of “informational advantage” states that the level of punctuation is higher in less democratic regimes. For this hypothesis, our data shows a mixed picture. With the exception of budget outlays, punctuations are more pronounced in the socialist than in the democratic period (see Columns 2 and 3 in Table 4). Finally, the fourth hypothesis regarding the “hybrid anomaly” states that the level of punctuation is the highest during hybrid regimes. This was supported by evidence only for the output side of the policy process while the punctuation of hybrid and democratic regimes was lower than those of the communist regime for the process phase datasets.

Table 4. LK values for the baseline regime classification

We also calculated LK scores for alternative regime classifications (Table 5). H1 and H2 hold for these re-categorisations as well with the exception of the two budgetary data in the “core socialist” period and the combination of various partly free regimes (see Column 4). For the third hypothesis of the “informational advantage”, the inclusion of the post-2010 period in the democratic era does not alter the results. The LK for 1990–2018 is very close to the values for the 1990–2010 period and are lower than those for both the socialist and the core socialist period, once again with the exception of budget outlays.

Table 5. LK values for the alternative periodisation

Discussion

Our primary analysis lent support for the general punctuation and the institutional friction hypotheses. In this, a long time series of Hungarian data corroborate the findings of the USA and Western European literature. Generally speaking, the comparative results of Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009: 612) are in line with our results. The application of the PET framework is validated in that all LK scores for Hungary significantly exceed the related value of the normal distribution.

These values also fall into the clusters described by Baumgartner and his co-authors when it comes to the elements of the input–process–output scheme (see Table 6). These results speak to the universal relevance of H1 and H2 in policy dynamics, regardless of the key contextual factor of political regimes. We have also found evidence for the informational advantage hypothesis, once again in line with the available comparative research.

Table 6. Comparative LK scores for four countries

Source: Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009). +“Interpellations and proposals”.

The score for Hungarian laws and decree laws is similar to the figures in the other three countries. For interpellations and budgetary data, they are somewhat lower. But for the process phase at least, the difference falls within the narrow range of 5–10 basis points. The difference in budgetary results may be the result of the electoral cycle-based method of accounting in the Hungarian case instead of the internationally explored year-on-year changes. All in all, the Hungarian data fit well in with existing calculations for Belgium, Denmark and the USA (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Progressive institutional friction in four countries.

A second result that is worth further discussion was related to the fourth hypothesis. It is important to note that the hybrid anomaly thesis was based on very limited evidence (a single paper on Hungarian budgeting). Another crucial element to note is that we could only rely on three years for budgetary data for the hybrid period and that our analysis of these data was based on a yearly accounting while interpellations and laws were aggregated to electoral cycles due to a lack of sufficient yearly data. Our mixed result for H4 underlines the importance of gathering new evidence for any PET-related hypothesis from various domains (countries, eras, agenda types) until general conclusions can be reached.

Our third point of discussion directly flows from this problem and it is related to data sources and methodology. As we have seen, the results from particular data series may not be a seamless match the progressive friction pattern (especially for budget proposals and outlays). While in some cases, information of the placement of individual datasets in the friction process is subsumed in the averages for the three phases of stick-slip dynamics their separate listing carries much methodological value.

In this respect, it is important to note that the choice of data series in studies of progressive friction, both in our paper and in its precursors, is influenced by data availability. For each phase of the friction process in the study by Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009) the number of data series used ranged between 1 and 7 which, in turn, assigns a different weight to specific data sources in any given phase average. Furthermore, even in comparable phases (e.g. in the policy process phase) the actual content of data may differ from country to country. In the aforementioned paper, besides the common core of bills and laws, the selection included hearings for the USA and government agreements for Belgium. None of these latter modules were featured for other country cases (even as hearings are similar to interpellations in that they may touch on multiple issues and are primarily the means of the opposition parties at the time). The length and exact period of time series also showed remarkable variance.

This is not to say that comparative studies of PET and institutional friction do not offer a contribution to the literature. In fact, our results corroborate the “general” adjective in the general punctuation thesis: our overall results are independent on the specific institutional arrangements of Hungarian political regimes. Having said that, there is a fair chance that the inclusion of new data series in the averages of the three phases of friction would modify the specific cumulated LK scores for each phase. Our conclusion from this discussion, therefore, is that the validity of comparative results regarding the progressive friction hypothesis has to be buttressed by a transparent presentation of the underlying datasets.

Conclusion

The dual aim of this article was to conceptualise policy dynamics for non-democratic polities and to extend the punctuated equilibrium framework to hitherto under-studied regime types, periods and regions. The Hungarian case covering the years between 1945 and 2018 offered a unique opportunity to compare policy stability and change in three distinct regimes: socialist autocracy, liberal democracy and the illiberal hybrid regime.

We set out to investigate two standard hypotheses of the literature on punctuated equilibrium and institutional friction in public policy as well as two less widely used ones on punctuated equilibrium in different political regimes. We found empirical support for the general punctuation hypothesis for Hungary: output change distributions from human decision-making institutions, as measured by interpellations, laws and budgetary data, are characterised by positive kurtosis – a result echoed in the comparative literature.

We arrived at similar results when it comes to the progressive friction hypothesis. The informational advantage was also supported, similarly to other papers in the comparative literature. Finally, we reached ambiguous results when it comes to the specificities of hybrid regimes: only budget-related scores were higher than those for the Socialist period.

We conclude our analysis by returning to the substantive issue at hand: the inter-related nature and potential structure of the various venues of public discourse and decision-making. The general idea of slip-stick dynamics is centred around the notion of friction – or institutional friction in the case of politics. This is clearly present when it comes to the dissimilarities between various forms of policy agendas from media and public opinion to on the one hand, and policy outputs, such as budgets, on the other hand.

At this point, we could not rely on “input” phase data, such as media or public opinion polls. And a definite answer to this question is also elusive at the current state of research. Recent studies – such as the 7-country comparison conducted by Vliegenthart et al. (Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Bonafont, Mortensen, Sciarini, Tresch, Bevan, Jennings, Grossman and Brouard2015) – yielded mixed results, which also pointed towards a key role of domestic political systems. Furthermore, case study evidence from Hungary (Boda and Patkós Reference Boda and Patkós2018) highlights the reverse dynamics of agenda setting by the government. In any case, the gradual build-up of empirical evidence from new settings (regimes, periods and regions) is the only way towards generalisable findings related to policy dynamics beyond liberal democracies.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the research assistance of Dávid Heffler. The project was supported by Hungarian Scientific Research Fund Grant nr. ÁJP-K-109303 and by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office grant nr. FK-123907, the Artificial Intelligence National Laboratory of Hungary, as well as the Bolyai grant of Miklós Sebők.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/MYEBKF (Sebők et al. Reference Sebők, M. Balázs and Molnár2021).